Abstract

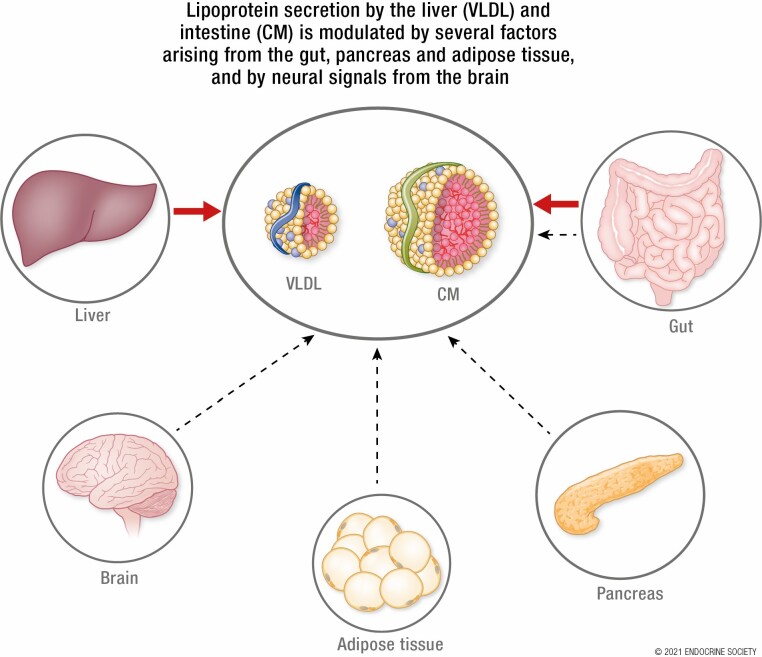

Plasma triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL), particularly atherogenic remnant lipoproteins, contribute to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Hypertriglyceridemia may arise in part from hypersecretion of TRLs by the liver and intestine. Here we focus on the complex network of hormonal, nutritional, and neuronal interorgan communication that regulates secretion of TRLs and provide our perspective on the relative importance of these factors. Hormones and peptides originating from the pancreas (insulin, glucagon), gut [glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and 2 (GLP-2), ghrelin, cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY], adipose tissue (leptin, adiponectin) and brain (GLP-1) modulate TRL secretion by receptor-mediated responses and indirectly via neural networks. In addition, the gut microbiome and bile acids influence lipoprotein secretion in humans and animal models. Several nutritional factors modulate hepatic lipoprotein secretion through effects on the central nervous system. Vagal afferent signaling from the gut to the brain and efferent signals from the brain to the liver and gut are modulated by hormonal and nutritional factors to influence TRL secretion. Some of these factors have been extensively studied and shown to have robust regulatory effects whereas others are “emerging” regulators, whose significance remains to be determined. The quantitative importance of these factors relative to one another and relative to the key regulatory role of lipid availability remains largely unknown. Our understanding of the complex interorgan regulation of TRL secretion is rapidly evolving to appreciate the extensive hormonal, nutritional, and neural signals emanating not only from gut and liver but also from the brain, pancreas, and adipose tissue.

Keywords: chylomicrons, very-low density lipoproteins, gut peptides, pancreas, brain, adipose

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

ESSENTIAL POINTS.

Hypertriglyceridemia due to hypersecretion of lipoprotein particles from the liver and intestine and the resultant elevation in lipoprotein particles and their remnants increases the risk of atherogenic cardiovascular disease in humans.

Interorgan communication, through neural networks and direct receptor-mediated mechanisms, coordinates the production and secretion of lipoprotein particles in fed and fasted states.

Hormonal signals originating from the pancreas, gut, and adipose tissue have been shown to modulate hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion, in some cases through involvement of the brain, creating neural links between the gut, brain, and liver with modulation by factors from the pancreas and adipose tissue.

The gut microbiome can influence intestinal and hepatic lipoprotein secretion through altered lipid availability, bile acid signaling, inflammatory processes, and short chain fatty acids.

Intranasal administration of insulin, glucagon, and glucagon-like peptide 1 to target the brain have been shown to modulate hepatic lipid metabolism in humans.

Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are often associated with lipid and lipoprotein abnormalities that contribute to increased atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD). The so-called atherogenic dyslipidemia complex consists of hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, increased small dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL), elevated remnant lipoproteins, and postprandial hyperlipidemia (1). Hypertriglyceridemia arises, in most cases, from a combination of hypersecretion of lipoprotein particles by the liver and intestine and from impairment in their clearance from the circulation. Circulating lipoprotein particles are sequentially delipidated by lipases [predominantly lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and hepatic lipase], yielding atherogenic remnant lipoprotein particles (2). Pharmacological or dietary interventions that improve dyslipidemia and lower circulating lipoproteins have been shown to decrease atherosclerotic CVD in at-risk populations (3).

The secretion of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles from the liver and chylomicrons (CMs) from the intestine are driven largely by substrate (ie, lipid) availability. CMs are constitutively secreted throughout the day but expand enormously in size and increase in number during the postprandial period to accommodate the large influx of dietary fat (4). Hepatic VLDL secretion also increases in the postprandial period but is maintained during the fasted state in which flux to the liver of free fatty acids (FFA) arising from adipocyte lipolysis provides substrates for triglyceride (TG) synthesis and packaging into VLDL for delivery to extrahepatic tissues.

Besides substrate availability, lipoprotein secretion in the liver and intestine is also subjected to regulation by numerous factors (5,6). The interconnected regulation of hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion, responsive to the nutritional state of the organism and acting through circulating regulatory factors and neural networks, is increasingly being appreciated. In this review, we will examine hormonal, neural, and nutritional signals that directly or indirectly regulate lipoprotein secretion through interorgan communication. The neural and hormonal signals that arise from the intestine, including the role of gut microbiome and bile acids, and other major organs will be discussed in relation to their direct effect on CM and VLDL secretion and indirect effects via neural networks. This is a rapidly emerging field, with some regulatory factors having been extensively studied and shown to be relevant in humans, whereas others are supported by less convincing evidence, with little known about how they ultimately regulate lipid mobilization and lipoprotein secretion. Throughout this review we will provide our own views and opinions, based on our interpretation of the literature, regarding the physiological relevance and relevance to humans of the various regulatory factors under discussion. Following a brief overview of the cellular pathways of hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion, we will discuss regulators of lipoprotein secretion that arise external to the hepatocyte and enterocyte, derived from the pancreas, intestine, and adipose tissue, respectively, with reference to neural network connections throughout.

Cellular Pathways of Hepatic and Intestinal Lipoprotein Secretion

A brief review of the similarities and differences of cellular mechanisms of hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion is pertinent to understanding their regulation by circulating hormones and nutrients. For more detailed information, we direct the reader to more extensive reviews on lipoprotein secretion (6-8). Both tissues produce lipoprotein particles that consist of a TG and cholesteryl ester rich core encased in a phospholipid monolayer containing several interchangeable apolipoproteins (apo). In addition, a single nonexchangeable apoB is present on each lipoprotein particle. In humans and some species (eg, the Syrian golden hamster), hepatocytes exclusively secrete apoB100 while enterocytes secrete a truncated apoB48, produced through apoB messenger RNA (mRNA) editing (9). In contrast, other species including rats and mice secrete apoB100 and apoB48 by both hepatocytes and enterocytes; therefore, the tissue source of apoB cannot be distinguished in these latter species.

In both tissues, apoB undergoes cotranslational translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum lumen where lipidation is facilitated by microsomal TG transfer protein (MTP). Further lipidation yields immature particles that are transported in vesicles to the Golgi for further processing prior to secretion (10). Both tissues can also store TG in cytosolic lipid droplets (CLDs) that can be mobilized for lipoprotein production, oxidation, or use in other cellular processes.

Following CM and VLDL secretion into the lymphatic system and hepatic vein, respectively, the circulating lipoproteins are delipidated in the circulation, competing for LPL-mediated TG lipolysis. The resulting remnant particles are further enriched in cholesterol and depleted in TGs by cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated lipid exchange and are cleared from the circulation primarily at the liver by hepatic lipase and receptor-mediated mechanisms (11).

In the fed state, intestinal CM production is stimulated massively by dietary lipid intake. Dietary TG are hydrolyzed in the intestinal lumen into monoacylglycerol and FFAs. Fatty acid uptake occurs predominantly via CD36/fatty acid (FA) translocase followed by re-esterification through sequential action of monoacylglycerol acyltransferase (MGAT) and diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT). In contrast, TG for hepatic VLDL production is supplied by several sources, including remnant uptake, re-esterification of FAs derived from adipose lipolysis and dietary FA spillover, mobilization of CLDs, and de novo lipogenesis.

Both tissues secrete TG-rich particles, with similarities and differences in the cellular processes governing their production (6). In this review, we will discuss how hormonal and dietary factors regulate these processes to coordinate lipoprotein production between the 2 organs.

Signals Originating from the Pancreas

Insulin

Based on extensive evidence to date, we discuss the role of insulin first since it is undoubtedly one of the most important modulators of hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion, playing a key regulatory role in coordinating lipid delivery to tissues and influencing plasma triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) concentrations both by its effects on secretion as well as LPL-mediated TRL clearance (discussion of TRL clearance is beyond the scope of this review). In healthy, insulin-sensitive states, postprandial hyperinsulinemia suppresses VLDL and CM secretion, both directly as well as indirectly by acutely suppressing FA flux to liver and intestine. Insulin acutely inhibits hepatic apoB100 secretion by acting at several steps between the apoB translation process and ultimate VLDL secretion by the liver (Fig. 1). The acute suppressive effect of insulin on lipoprotein secretion is blunted in insulin resistant states. Insulin resistance is associated with hyperinsulinemia and complex metabolic changes that result in chronic hypersecretion of both hepatic and intestinal TRL.

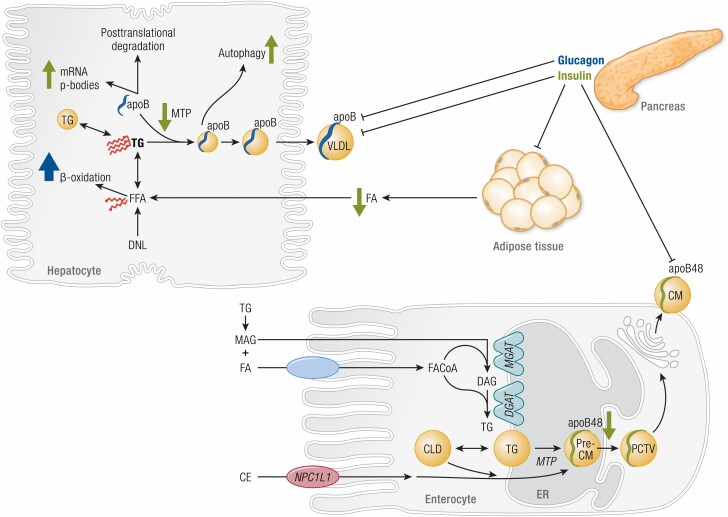

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of lipoprotein secretion and acute regulation by insulin and glucagon. Pancreatic insulin acutely suppresses chylomicron (CM) and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion via several mechanisms in enterocytes and hepatocytes (green arrows), respectively. In hepatocytes, triglyceride (TG) arises in part from de novo lipogenesis (DNL) to yield free fatty acids (FFA) and intracellular TG storage pools. VLDL particles are formed by progressive lipidation of apolipoprotein B (apoB) by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP). In enterocytes, TG synthesis in the leaflets of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) arises from re-esterification of monoacylglycerol (MAG) and diacylglycerol (DAG) by respective transferases (MGAT, DGAT). Cholesterol esters (CE) are incorporated in pre-CMs after absorption via Niemann-Pick C1-Like-1 (NPC1L1). Pre-CMs exit the ER in pre-CM transport vesicles (PCTV) for maturation at the Golgi apparatus prior to secretion as CM. Insulin acutely increases hepatic apoB mRNA p-body formation, decreases MTP-mediated apoB lipidation and MTP expression, and increases postendoplasmic reticulum autophagy. Insulin indirectly alters VLDL-TG production by inhibiting fatty acid (FA) release by adipose tissue. Insulin acutely suppresses CM secretion with decreased apoB48 stability. Some evidence suggests a possible role for the brain in insulin-mediated suppression of VLDL secretion; however, this requires further substantiation. Pancreatic glucagon acutely suppresses VLDL secretion through increased catabolism of FA by beta-oxidation pathways (blue arrow), including increased expression and activity of key beta-oxidation enzymes carnitine acyl transferase -1 and -2 (CPT-1, CPT-2) (12,13).

Insulin does not regulate apoB100 transcription but inhibits translation by diverting mRNA into granules called P bodies, lowering the pool of translationally competent mRNA, an effect dependent on signaling through PI3k and mTORC1 (14,15). Hepatic apoB100 is rapidly degraded unless lipidated by MTP. Insulin decreases MTP expression through inhibition of the transcription factor FoxO1 and thereby decreases apoB100 lipidation, representing another mechanism by which insulin promotes degradation of the lipid-poor apoB100 particle (16). Accordingly, insulin-resistant rodents have increased apoB100 secretion, along with increased active FoxO1, MTP expression and abundance (17). In addition, MTP-independent lipidation of the VLDL particle is suppressed by insulin. This could be explained in part by decreased FoxO1 mediated transcription of apoC3. ApoC3 overexpression in hepatocytes, which lack endogenous apoC3, stimulated MTP-independent lipidation. Prior to VLDL secretion, insulin stimulates post-ER degradation of lipidated apoB100 particles via PI3k-dependent autophagy (18). Interestingly, insulin also inhibits apoB100 degradation via mTORC1 mediated suppression of sortilin, a Golgi bound trafficking protein that promotes lysosomal degradation (19). However, this effect is outweighed by insulin’s numerous inhibitory effects on apoB100.

Similar to hepatocytes, direct insulin effects on intestinal CM secretion have also been implicated in modulating intestinal CM secretion. Acute insulin treatment suppresses CM secretion in healthy humans and insulin sensitive animal models (20-22). In chow-fed hamsters, insulin suppresses plasma appearance of apoB48-containing lipoproteins and inhibits de novo apoB48 synthesis in vitro. This occurs alongside activation of insulin signaling components including increased tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor (20).

Insulin resistance induced by fructose feeding impairs enterocyte insulin signaling with decreased phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 and Akt abundance as well as increased activation of the transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), which induces expression of lipogenic genes (20). Accordingly, fructose-fed hamsters had increased intestinal de novo lipogenesis and synthesis of cholesterol esters providing more substrate for CM synthesis as well as increased MTP abundance and activity to support enhanced CM lipidation (22). This resulted in a more pronounced increase in large CMs and a lesser increase in small CMs. Insulin resistance was also associated with increased apoB48 stability as demonstrated by increased intracellular apoB48 mass in fructose-fed hamsters (22). The mechanisms by which insulin resistance increases lipoprotein secretion shares similarities between hepatocytes and enterocytes. Both involve enhanced apoB stability and increased MTP abundance and/or activity (22,23).

Activation of intestinal inflammatory pathways has also been shown to contribute to intestinal insulin resistance. In fructose-fed hamsters increased apoB48 secretion was attributed, in part, to increased basal phosphorylated extracellular signal-related kinase (Erk) 1/2, indicative of activation of inflammatory pathways that could interfere with insulin signaling (20). In accordance with this, intravenous infusion of proinflammatory tumor necrosis factor alpha in hamsters impaired activation of key components of the insulin signaling cascade in the intestine, coinciding with increased MTP abundance and enhanced apoB48 secretion (24). These effects were blocked by inhibition of p38 in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (24). Similarly, duodenal p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation is increased in insulin-resistant compared to insulin-sensitive obese adults, along with other inflammatory signaling components such as interferon gamma and toll-like receptor 4 (25,26). Based on human and animal studies, we postulate that activation of inflammatory pathways in obesity and insulin resistance plays a causal role in establishing intestinal insulin resistance resulting in increased CM secretion.

Along with modulating the machinery of lipoprotein synthesis, insulin also indirectly influences availability of TG for incorporation into lipoprotein particles. Inhibition of adipose tissue lipolysis by insulin decreases FFA flux to the liver and intestine. For CM synthesis, the majority of TG arises from dietary fat. However, circulating FFAs have been shown to stimulate CM secretion in animal models and humans (27,28). In fact, insulin-mediated inhibition of CM production in humans was due in part to suppression of circulating FFAs via insulin mediated inhibition of adipose tissue lipolysis (29). However, FFAs from the circulation may serve more of a signaling function since they are generally not re-esterified and secreted in CMs, in contrast to TGs derived from apical absorption of luminal FAs and monoglycerides.

Scherer et al demonstrated that ICV insulin infusion in rats paradoxically increased hepatic VLDL secretion in contrast to intravenous insulin, which suppressed VLDL secretion. This occurred with both acute and chronic ICV insulin infusion, with the latter resulting in decreased hepatic lipid content without altering de novo lipogenesis (30). The mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) has previously been shown to be critical for central nervous system (CNS)-mediated insulin effects on hepatic glucose production and adipose tissue lipolysis. However, direct insulin infusion into the MBH had no effect on hepatic VLDL secretion, suggesting this area is not critical for insulin regulation of VLDL secretion (30). Instead, neural networks connecting the MBH to the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) of the brainstem have been shown to regulate VLDL secretion, as infusion of FAs (31) and glycine (32) inhibit VLDL secretion via the hepatic vagus nerve. Whether this hypothalamic-DVC-vagal circuit is activated by insulin is unclear. Recently, Li et al proposed a model in which the adipocytokine secreted frizzled-related protein 5 activates hypothalamic insulin signaling through Akt and PI3k (33). This activated potassium adenosine 5′-triphosphate (KATP) channels to initiate communication with the DVC N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and KATP channels to suppress hepatic glucose production. However, this secreted frizzled-related protein 5-mediated activation of MBH insulin signaling decreased VLDL secretion (33), in contrast to ICV insulin which increased VLDL secretion (30). Insulin infusion directly into the DVC activated Erk1/2 signaling and KATP channels without affecting PI3k and decreased hepatic glucose production (34); however, it remains to be seen whether direct activation of DVC insulin signaling modulates VLDL secretion.

Circulating insulin, known to acutely suppress VLDL secretion, might act partly via the CNS to influence hepatic energy metabolism. In mice, hyperinsulinemia-mediated suppression of VLDL secretion was diminished when it was accompanied by ICV infusion of neuropeptide Y (NPY), suggesting insulin downregulates hypothalamic NPY to elicit its effects on VLDL secretion (35). NPY is abundant in the central and peripheral nervous system and found mainly in the postganglionic sympathetic neurons where it is released simultaneously with norepinephrine. Previous reports of ICV infusion of NPY alone demonstrated no effect on VLDL secretion in mice (36) and enhanced VLDL secretion in rats (37,38). In rats, enhanced VLDL-TG secretion by a single ICV injection of NPY occurred through remodeling of hepatic phospholipids into TG to contribute to VLDL maturation and secretion (39). NPY increased sympathetic outflow to the liver, which increased hepatic stearoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) desaturase-1, ADP-ribosylation factor-1, and lipin-1 abundance, all of which are key proteins involved in converting phospholipids to TG and in VLDL maturation and secretion (39). Whether these effects play a role in central insulin’s activation of VLDL secretion remains to be explored.

To assess the role of the CNS in humans, intranasal delivery of small peptides is used to increase their concentration in cerebrospinal fluid (40). Although intranasal insulin (40 IU) administered under conditions of a pancreatic clamp suppressed endogenous glucose production in lean, insulin-sensitive men (41), the same dose had no effect on TRL-apoB100 or B48 kinetics in healthy men (42). A study without a pancreatic clamp and with a larger dose (160 IU) found no change in endogenous glucose production in lean control or overweight individuals with T2D (43). However, they observed decreased hepatic TG content in lean subjects but not in those with T2D (43). It should be noted that this response in lean subjects occurred during transient systemic hyperinsulinemia due to spillover of intranasal insulin into the systemic circulation and reduction in FFA levels. Intravenous insulin in lean subjects had the opposite effect, increasing hepatic lipid content in response to short-term infusion (43). Indeed, 160 IU intranasal insulin, a dose shown to activate parasympathetic outflow in humans (44), decreased whole-body lipolysis without any changes in circulating insulin levels or altered expression of lipolytic enzymes in subcutaneous white adipose tissue (45). Similarly, ICV insulin targeting the hypothalamus in rats dampens sympathetic nervous system outflow to visceral white adipose tissue resulting in decreased hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) activation but had no effect on subcutaneous HSL activation (46). Therefore, although central insulin was not sufficient to modulate lipoprotein kinetics in humans at the doses investigated, it does play a role in suppression of adipose lipolysis and thus may indirectly contribute to decreased lipoprotein production through decreased substrate availability. Whether this is relevant at a physiological level is unclear. Brain insulin sensitivity is diminished in obesity (47), suggesting a further mechanism by which adipose lipolysis and lipoprotein production is augmented in obesity.

In summary, insulin can be regarded as a master regulator of lipoprotein metabolism that responds to nutrient influx by promoting lipid storage in adipose tissue, while acutely suppressing CM and VLDL secretion and enhancing their clearance. Its acute suppressive effect on lipoprotein secretion is mediated directly in the liver and intestine and indirectly by regulating FA flux to these tissues and possibly via neural pathways (Table 1, Fig. 1). Insulin’s suppressive effect on lipoprotein secretion is blunted in insulin resistance (23), which is associated with a number of other metabolic changes that contribute to the hypersecretion of TRL and their reduced clearance. Strategies to improve insulin sensitivity are known to improve dyslipidemia of insulin resistance. This includes, for example, bariatric surgery (102), dietary regimens (103), and pharmacotherapies such as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibitor pioglitazone (104).

Table 1.

Summary of observations in animal models and humans regarding effects on hepatic very low density lipoprotein and intestinal chylomicron production by hormones and nutritional factors

| Animal Models | Humans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLDL | CM | VLDL | CM | References | |

| Insulin | Inhibits secretion in acute setting | Inhibits secretion in acute setting | Inhibits secretion in acute setting | Inhibits secretion in acute setting | (20-23, 29,30, 35-38,42) |

| Glucagon | Decreases plasma TG, inhibits TG synthesis in primary hepatocytes | Further research required | Inhibits secretion in acute setting | No effect in acute setting | (48-54) |

| GLP-1 | Inhibits secretion with chronic treatment in hamsters | Inhibits secretion in acute and chronic settings | No effect in acute setting | Inhibits secretion in acute and chronic settings | (55-61) |

| GLP-2 | Discordant observations | Stimulates secretion in acute setting | No effect in acute setting | Stimulates secretion in acute setting | (62-70) |

| Ghrelin | ICV reduced hepatic TG content | No effect on secretion, reduced CLDs | Further research required | Further research required | (71,72) |

| CCK | CCK −/− and antagonism reduced hepatic TG content | CCK −/− delayed TG and apoB48 in lymph | Further research required | Further research required | (73-77) |

| Peptide YY | Agonist infusion had no effect in mice | In vitro inhibition of cholesterol incorporation into lipoproteins | Further research required | Further research required | (78,79) |

| Nutritional factors | |||||

| Glucose | ICV glucose decreased VLDL secretion in rats | Oral glucose increased CM secretion | IV glucose had no effect on TRL- apoB100 production | Enteral and IV glucose increase CM secretion | (66,80-82) |

| Glycine | DVC infusion normalizes VLDL secretion in high- fat fed rats | Further research required | Further research required | Further research required | (32) |

| Fatty acids | Hypothalamic infusion decreased VLDL-TG secretion in rats | Acute stimulation of CM secretion in hamsters | Acute stimulation of VLDL secretion | Acute stimulation of TRL- apoB48 secretion | (27,28,31) |

| Microbiota | Antibiotics increased hepatic lipid accumulation | Antibiotics decreased lymphatic TG and decreased apoB production, specific microbes attenuate CM secretion | Further research required | Further research required | 83-90 |

| Bile acids | Decreased VLDL secretion | Decreased postprandial TG with enhanced beta oxidation capacity | Further research required | Further research required | (91,92) |

| Adiponectin | Enhanced clearance, no effect on secretion | Further research required | Inversely associated with VLDL-TG and apoB100 secretion | Inversely associated with apoB48 | (93-95) |

| Leptin | Exogenous leptin in Lep−/− decreased hepatic lipid content | Lepr −/− decreased expression of synthesis genes | Replacement therapy in lipodystrophy decreases hepatic steatosis | Further research required | (96-101) |

Abbreviations: −/−, homozygous genetic deletion; apoB, apolipoprotein B; CCK, cholecystokinin; CLD, cytosolic lipid droplet; CM, chylomicron; DVC, dorsal vagal complex; GLP-1, Glucagon-like peptide-1; GLP-2, Glucagon-like peptide-2; ICV, intracerebroventricular; IV, intravenous; Lep, leptin; Lepr, leptin receptor; TG, triglycerides; TRL, TG-rich lipoproteins; VLDL, very low density lipoprotein.

Glucagon

Like insulin, glucagon plays an important regulatory role in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Glucagon secretion by pancreatic alpha cells in response to hypoglycemia has been extensively studied. Glucagon acts primarily on the liver where it stimulates gluconeogenic and glycogenolytic pathways to raise blood glucose. Although glucagon receptor antagonists have been shown to improve glycemia in T2D, they induced adverse effects related to lipid metabolism including increased LDL-cholesterol and hepatic lipid content (48,49,105). Similarly, high-fat-fed glucagon receptor knockout mice developed hepatic steatosis due to impaired control of fasting hepatic lipid metabolism (50). Inhibition of the glucagon receptor using small interfering RNA in leptin-receptor deficient db/db mice increased hepatic lipid content, lipogenic gene expression, and TG secretion (51).

In the fasted state the circulating insulin to glucagon ratio is low, reflective of the life sustaining requirement for the body to maintain basal glucose levels during fasting. This diminishes insulin-mediated suppression of adipose lipolysis and favors release of FFA into the circulation. In rodents, glucagon stimulates adipose tissue lipolysis through protein kinase A-mediated activation of HSL and perilipins. To date, the glucagon receptor has not been found on human adipocytes, in contrast to rodent adipocytes, which are believed to express the receptor based on studies employing monoclonal antibodies to detect the receptor (106). In humans, studies on the effects of glucagon on adipose tissue lipolysis have shown conflicting results (52,107,108). Glucagon can have indirect effects through activation of GLP-1 receptors or by stimulation of catecholamines and growth hormone, which are known to have lipolytic effects (109-111).

At the liver, glucagon signaling diverts FFA away from TG re-esterification and towards beta-oxidation and ketogenesis, thereby depleting substrate availability for VLDL synthesis (50) (Fig. 1). This occurs through several direct glucagon receptor-mediated effects. Glucagon can increase the intracellular ratio of adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP) to adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) leading to activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) activity (50). PPARα, as well as the transcription factor 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding (CREB), promotes transcription of genes involved in beta-oxidation including carnitine acyl transferase-1 (CPT-1) and -2. AMPK also inhibits acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which inhibits formation of malonyl-CoA, a lipogenic enzyme that inhibits CPT-1, further augmenting CPT-1 activity and capacity for beta-oxidation (12,13). Recently, increased hepatic beta-oxidation in response to glucagon was shown to be partly dependent on the bile acid nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR), representing a possible link between the gut and liver in regards to glucagon control of lipid metabolism (112).

Along with stimulating FA oxidation, glucagon also suppresses hepatic TG synthesis through modulation of lipogenic gene expression by the transcription factor 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive element-binding protein H (CREBH), which is expressed exclusively in the liver and intestine. The extensive literature on CREBH mediated regulation of metabolism has been reviewed elsewhere (113,114). In the context of glucagon action, activation of the hepatic glucagon receptor induced translocation of CREBH from the ER to the nucleus. It antagonized the lipogenic transcription factor SREBP1-c to induce glucagon-mediated suppression of de novo lipogenesis (53).

In healthy humans, acute hyperglucagonemia in the setting of a pancreatic clamp, decreased hepatic apoB100 secretion in line with diversion of FFA away from VLDL synthesis. Intriguingly, apoB100 clearance was also diminished resulting in no net effect on plasma VLDL apoB100 concentrations (54) (Table 1). Hyperglucagonemia had no effects on CM production or clearance, de novo lipogenesis, or TG turnover (54).

Although both insulin and glucagon have been shown to acutely suppress apoB100 secretion, the relative effect size is greater with insulin. In healthy humans, insulin and glucagon suppressed hepatic apoB100 production rate by approximately 53% (29) and 30% (54), respectively. Similarly, studies in mice elicited a greater response with insulin. In mice, glucagon suppressed hepatic TG secretion by approximately 30% (50) whereas insulin suppressed apoB100 secretion from primary hepatocytes by approximately 50% (115).

Whether CNS glucagon modulates lipoprotein metabolism has not been established. Intriguingly, hypothalamic glucagon inhibits glucose production, in contrast to the classical role of circulating glucagon to raise plasma glucose (116,117). Similarly, intranasal glucagon in healthy humans reduced endogenous glucose production (118). However, intranasal glucagon had no significant effects on plasma FFA or TG concentrations in lean or obese subjects (118,119), suggesting this brain-liver axis may have differential effects on glucose and lipid metabolism.

In summary, glucagon has diverse effects on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, countering insulin’s adipose tissue antilipolytic effect and yet suppressing rather than enhancing hepatic TG export in VLDL, possibly by diverting FAs to oxidative and ketogenic pathways. Acute hyperglucagonemia does not appear to regulate intestinal lipoprotein secretion and does not appear to regulate lipid and lipoprotein secretory pathways via neural networks, although more research is needed to further understand glucagon’s full effects on lipoprotein secretion.

Signals Originating From the Gut

Nutritional and hormonal signals originating from the gut influence CM and VLDL secretion directly and indirectly via neural networks. In transition from the fasted to fed state, mixed meal intake induces secretion of numerous gut peptides and hormones to coordinate the metabolic response to nutrient influx. This coordination occurs through direct effects of circulating hormones on target tissues and via neural networks enlisted by nutrients and hormones. Whereas the effects of gut peptides GLP-1 and GLP-2 on lipoprotein secretion have recently been the focus of investigation by a number of groups, much less is known about the regulatory effects of the many other gut signals on lipoprotein metabolism. As we will discuss later, GLP-1 and GLP-2 exert major regulatory effects on intestinal lipoprotein secretion while minimally affecting hepatic VLDL secretion. Of note, there is minimal evidence that the incretin hormone gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) secreted by intestinal K cells affects CM or VLDL secretion. In dogs, GIP decreased CM levels by enhancing peripheral TG clearance via LPL (120). In humans, GIP administration decreased FFA release from adipose tissue, but it remains to be seen whether this indirectly influences CM or VLDL secretion (121). Dual GLP-1/GIP co-agonists are under evaluation as T2D therapeutics. Levels of LDL-cholesterol, TG, FFAs, and apoB were reduced in individuals with T2D treated with coagonists, although it has not yet been established whether these effects are due to reductions in VLDL and/or CM secretion (122).

Vagal afferent neurons in the gut have receptors for gut hormones and nutrients including long-chain FAs, CCK, ghrelin, leptin, peptide YY, GLP-1, and serotonin (5-HT) (123), all of which modulate signaling to the hypothalamus to provide information about the nutrient composition and caloric content of the meal. Vagal afferent fibers are found along the gastrointestinal tract with their cell bodies located in the nodose ganglion (124). The axons project to the DVC within the brainstem, specifically in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) (125). From there, other neurons project from the NTS to the hypothalamus in the forebrain (126). The hypothalamus is also accessible via a permeable fenestration of the blood-brain barrier allowing receptor-mediated transport across the blood-brain barrier for several circulating factors, including glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and leptin (127,128). Efferent signals, from areas of the brain targeted by gut hormones, project to the liver to create a so-called gut-brain-liver axis, allowing gut hormones to modulate hepatic metabolism via neural networks. This gut-brain-liver axis has been described primarily for regulation of hepatic glucose production, indicating neural connections that contribute to how glucagon (117), insulin (47), ghrelin (129), and dietary FAs (130) regulate glycemia. This provides evidence that neural networks play an important role in energy regulation; however, discussion of neural regulation of hepatic glucose production is beyond the scope of this review. Here, we will limit our discussion of neural signals to lipoprotein production.

Glucagon-like peptide 1

GLP-1 receptor agonists have been developed into a therapeutic treatment for diabetes that improve glycemic control and insulin sensitivity and induces weight loss (131) (Fig. 2). In large-scale cardiovascular outcome trials, GLP-1 receptor agonists have also demonstrated cardioprotective effects (132), although the mechanisms of their cardiovascular beneficial effects are still a matter of speculation. One cannot exclude that their favorable modulation of lipoprotein metabolism may contribute to their cardiovascular beneficial effects. Therefore, the effects of GLP-1 on lipoprotein production are of great clinical relevance and have received considerable research attention compared to the other gut-derived modulators.

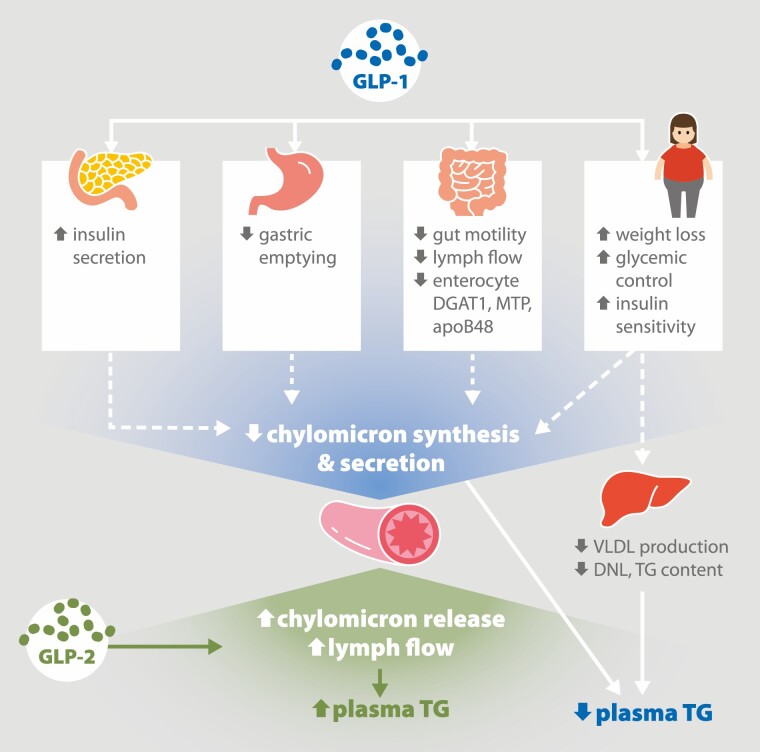

Figure 2.

Effects of glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 and -2 on very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) and chylomicron (CM) secretion. GLP-1 elicits numerous effects on various tissues to decrease VLDL and CM secretion. GLP-1 enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from the pancreas and delays gastric emptying. In the intestine, GLP-1 decreases gut motility and flow of fluid through the mesenteric lymph ducts. In CM-secreting enterocytes, GLP-1 decreases expression of key CM synthesis proteins including diacylglycerol transferase-1 (DGAT1), microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) and apolipoprotein B48 (apoB48). Long-term GLP-1 administration increases weight loss and improves glycemic control and insulin sensitivity. Together these effects inhibit CM synthesis and secretion. GLP-1 also decreases hepatic VLDL production, in part by suppressing de novo lipogenesis (DNL) and decreasing triglyceride (TG) content. The gut peptide GLP-2 increases CM secretion in humans and animal models, with robust stimulation of lymph flow in the mesenteric lymphatics.

Adapted from “American Diabetes Association, Gut Peptides Are Novel Regulators of Intestinal Lipoprotein Secretion: Experimental and Pharmacological Manipulation of Lipoprotein Metabolism doi: 10.2337/db14-1706, American Diabetes Association, 2015. Copyright and all rights reserved. Material from this publication has been used with the permission of American Diabetes Association.

Intestinal L cells secrete equimolar amounts of the gut peptides GLP-1 and GLP-2 in the early response to feeding. GLP-1 and GLP-2 acutely inhibit and stimulate CM secretion, respectively, in both humans and animal models (Fig. 2). This likely occurs through local mechanisms in the gut or via neural networks because GLP-1 and GLP-2 are rapidly degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase IV with half-lives in the circulation of only 1 to 2 and 7 min, respectively (133). The GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) is abundantly expressed along the gastrointestinal tract including on vagal afferent termini in the portal bed but not on enterocytes (134). GLP-1R is also found in pancreatic islets, brain, lung, heart, and kidney (135). The pleiotropic metabolic effects of GLP-1 have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (133). In regard to lipoprotein secretion, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying and gut motility, enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and suppresses glucagon secretion, all of which can independently modulate lipoprotein metabolism (55) (Fig. 2). Here we focus our discussion on the direct effects and provide evidence for a role for the CNS in mediating indirect effects of GLP-1 on lipoprotein secretion.

We now know that GLP-1 at both physiological and pharmacological concentrations modulates circulating lipoproteins predominantly by inhibiting CM secretion. In hamsters, a single dose of exogenous GLP-1R agonist decreased postprandial TRL apoB48 concentration and decreased apoB48 secretion in isolated enterocytes. These effects were reversed by endogenous blockade of the receptor with exendin [9-39] (8-11,14-40), demonstrating a physiological role for GLP-1 in regulating intestinal CM synthesis and secretion (56). Conversely, genetic ablation of the GLP-1 receptor in mice increased TRL apoB48 postlipid load (56). In rats, continuous intravenous infusion of recombinant GLP-1 [7-36] (7-11,14-37) at physiological concentrations in the presence of intraduodenal lipid infusion reduced mesenteric lymph flow rate, triolein absorption, and lymph apoB (57). In addition, recombinant GLP-1 [7-36] (7-11,14-37) decreased lymph apoA-IV, an apolipoprotein that may be involved in intracellular lipidation of the CM particle (136), suggesting a role for GLP-1 in modulating CM particle size. We have recently demonstrated that administration of a GLP-1 receptor antagonist in rats results in an increase in mesenteric lymph flow and TG output following administration of an intraduodenal lipid bolus, demonstrating that endogenous GLP-1 acts as a break on CM secretion (unpublished observations).

At pharmacological doses, GLP-1 analogues have been shown to suppress CM secretion in humans and animal models. In humans, a single subcutaneous injection of the GLP-1 analogue exenatide in the setting of a pancreatic clamp and intraduodenal lipid infusion inhibited CM apoB48 secretion, suggesting that pharmacological GLP-1 administration acutely suppresses CM secretion independent of its effects on pancreatic hormone secretion and gastric emptying (58). This acute effect persisted in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance or early onset T2D (59). Chronic GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment also decreased apoB48 secretion and increased apoB48 catabolism in individuals with T2D (60). In a parallel study in mice, 1 week of daily liraglutide reduced postprandial plasma TG along with reduced jejunal expression of proteins involved in CM synthesis, namely apoB48, diacylglycerol o-acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) and MTP (60). It is clear that acute pharmacological administration suppresses CM secretion; however, the precise mechanisms remain elusive as receptor expression is lacking on CM-secreting enterocytes. Existence of a gut-brain axis triggered by GLP-1R binding on vagal afferents has been demonstrated in humans and animal models in which GLP-1-mediated inhibition of food intake and stimulation of insulin secretion are abrogated by vagotomy (137-139). GLP-1R expression has been shown in the human and rodent hypothalamus and brainstem, the 2 main brain areas involved in energy homeostasis and autonomic function (140,141). GLP-1 is also produced within the brain in the NTS and olfactory bulb. The preproglucagon expressing neurons within the NTS project to the hypothalamus and modulate fasting induced refeeding without altering circulating GLP-1 levels (142). In the following discussion, we review the role of CNS GLP-1 on lipoprotein secretion.

The relative capacity of peripheral vs central GLP-1 to influence CM secretion was evaluated in chow-fed hamsters. Farr et al demonstrated that when peripheral GLP-1 agonist administration is coupled with ICV GLP-1 antagonist, the ability for GLP-1 agonist to suppress TRL-apoB48 appearance is maintained at approximately 55%, suggesting GLP-1 suppresses CM secretion independent of central action (143). Similarly, central GLP-1 itself assessed by GLP-1R agonist administration into the third ventricle suppressed TRL-TG and TRL-apoB48 secretion by approximately 55%. This effect was dependent on sympathetic neural outflow suggesting the presence of a brain-gut axis activated by GLP-1 (143). Importantly, β-adrenergic receptors have been identified on enterocytes, demonstrating their potential to directly respond to sympathetic activation (144). GLP-1 suppression of postprandial hyperlipidemia was prevented by ICV infusion of the GLP-1R antagonist exendin [9-39] (8-11,14-40) and by central melanocortin-4 receptor antagonism (143). This led the authors to propose a model in which peripheral GLP-1 has direct effects on enterocytes whereas central activation of GLP-1 receptors at the arcuate nucleus proopiomelanocortin neurons stimulate melanocortin-4 receptor activation to increase sympathetic outflow to enterocytes (143).

GLP-1R agonists have been shown to suppress VLDL secretion in animal models but not in humans. In normolipidemic humans, acute exenatide treatment had no effect on hepatic apoB100 secretion when administered during a pancreatic clamp in which pancreatic hormone secretion is replaced at basal concentrations (58). In hamsters, 7 days of daily intraperitoneal GLP-1R agonism with exendin-4 decreased hepatic lipid content along with reductions in plasma VLDL-TG and apoB100 and decreased markers of hepatic de novo lipogenesis (61). However, this effect was not reproducible in isolated hamster hepatocytes in which no GLP-1R activity was detected, suggesting indirect mechanisms. Indeed, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy eliminated exendin-4’s ability to improve dyslipidemia in the high-fructose fed hamster model, demonstrating dependence on intact parasympathetic signaling for GLP-1’s effects on hepatic lipid metabolism (61).

CNS GLP-1R binding elicits numerous extra-CNS effects including regulation of hepatic VLDL secretion. For example, intraperitoneal exendin-4 treatment in fructose-fed hamsters reduced hepatic VLDL secretion and expression of de novo lipogenesis genes, dependent on intact parasympathetic signaling (61). Recently, Varin et al aimed to identify the specific neuronal populations responsible for the TRL lowering effects of GLP-1 (145). GLP-1R was abolished in Wnt1 expressing neurons representing the hypothalamus, brainstem, and enteric nervous system. An additional mouse model was generated with GLP-1R ablation in Phox2b expressing neurons within regions of the autonomic nervous system. TG excursion following oral olive oil was not affected by genetic ablation of GLP-1R in Wnt or Phox2b expressing neural populations (145). Therefore, the precise neural populations involved in GLP-1 mediated alteration of TRL secretion remain unknown.

In summary, GLP-1 suppression of CM secretion is clear from pharmacological administration in humans and animals and from inhibition of endogenous GLP-1 signaling in hamsters (Table 1). Such effects may occur independent of GLP-1’s inhibition of gastric emptying or effects on pancreatic hormone secretion. Despite robust data in a variety of experimental model systems including the human to demonstrate that GLP-1 suppresses CM secretion, whether the effects of GLP-1 on CM secretion are mediated, at least in part, by the CNS remains to be established in humans. Discordant effects on VLDL secretion have been observed in humans and animals, with no effect in humans and suppression of VLDL secretion in animal models. The mechanisms by which prolonged GLP-1 treatment in humans suppresses hepatic VLDL secretion is less clearly defined and may be entirely secondary to weight reduction and improvements in glycemia that occur with more prolonged GLP-1 therapy.

Glucagon-like peptide-2

GLP-2 is secreted from the same intestinal L cells that secrete GLP-1 in response to nutrient intake. GLP-2 is an intestinotrophic hormone that stimulates intestinal epithelial differentiation, growth, and nutrient absorption (146). Stimulation of CM secretion by GLP-2 has been well described in humans and animal models, particularly when administered at pharmacological doses. In fact, other than enteral lipid itself, GLP-2 is the most robust enhancer of intestinal lipid and lipoprotein secretion that we have observed in our studies in humans and animals.

Continuous intravenous infusion of native GLP-2 in lean adults stimulated a greater rise in postprandial TG and FFA levels compared to placebo (62). This occurred without any change in glycerol levels, suggesting that lipolysis was not affected and pointing towards enhanced lipid absorption (62). This was supported by studies in mice and hamsters in which GLP-2 administered 20 min after an oral lipid bolus enhanced intestinal lipoprotein production, dependent on CD36 (63). The mechanisms by which GLP-2 modulates CD36 glycosylation or translocation to the cell membrane have not been elucidated. These studies suggest that GLP-2 enhances CM lipidation and secretion through accelerated fat absorption, particularly when administered in the presence of an oral lipid load. Interestingly, these stimulatory effects of GLP-2 on postprandial CM secretion antagonize the suppressive effects of GLP-1. When administered together, the effects of GLP-2 predominated in hamsters, with increased lipid absorption and increased TRL-TG and apoB48 (64). Administration of a dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor that inhibits the cleavage of both GLP-1 and GLP-2 allowed the effects of GLP-1 to dominate and suppress intestinal CM production (64).

Acute GLP-2 administration enhances secretion of preformed CM rather than stimulating de novo CM assembly and secretion. Our data suggest that GLP-2 mobilizes CM already secreted by the enterocyte, which possibly are localized in the lamina propria or in the lymphatics. First, we demonstrated in humans that a single subcutaneous injection of GLP-2 7 h after ingestion of a high-fat liquid formula rapidly increased plasma CM appearance, reaching a peak within 30 min. Mathematical modelling suggested that GLP-2 mobilized preformed CMs, rather than promoting new synthesis of lipoproteins (65). Second, in the postabsorptive state when minimal lipids remain within the intestinal lumen, GLP-2 still induced rapid appearance of CMs in the circulation labeled with retinyl palmitate administered in a lipid meal 7 h earlier (65). We have recently shown by electron microscopy of human intestinal biopsy samples that, despite robust mobilization of intestinal lipid by GLP-2 administered 5 h following ingestion of a high-fat liquid formula, there is no detectable mobilization of cytoplasmic lipid droplets (unpublished observations). In the rat mesenteric lymph cannulated model this lipid mobilizing effect of GLP-2 is blocked by Golgi disruption with Brefeldin A, suggesting that GLP-2 mobilized lipids and CM distal to the Golgi (unpublished observations). Finally, we have shown that a single dose of intraperitoneal GLP-2 administered 5 h after an intraduodenal lipid bolus rapidly and robustly increased mesenteric lymph flow and apoB48 appearance in rats, likely without changing the size of CM particles (66) (Fig. 2). The lack of effect on CM lipidation in the postabsorptive state suggests that CM particles did not acquire lipid from intracellular lipid stores, pointing to mobilization of extracellular lipid stores that are either intercellular, within the lamina propria, or within the mesenteric lymphatics (66).

Further support for the hypothesis that GLP-2 does not act directly on the enterocyte to enhance intracellular CM assembly and secretion relates to the fact that GLP-2 receptors (GLP-2R) are not expressed on enterocytes. Instead, GLP-2R is abundant on subepithelial myofibroblasts, enteroendocrine cells and enteric neurons (147). GLP-2R has also been identified on vagal afferent neurons projecting to the NTS in rats and on central neurons (148,149). Whether neural networks are required for GLP-2-mediated effects on intestinal lipoprotein secretion remains to be established. Other effects of GLP-2 on the gut are locally mediated likely via paracrine signaling. For example, GLP-2 prevented mucosal atrophy during total parenteral nutrition feeding through vagal-independent mechanisms (148). A similar local, vagal-independent mechanism may be important for GLP-2 mediated CM secretion, which remains to be tested.

Stimulation of mesenteric blood flow has been proposed as a potential mechanism by which GLP-2 enhances CM appearance. Although inhibition of nitric oxide synthase decreased CM appearance in hamsters and mice (67), this was not observed in humans (68). This interspecies difference may suggest a difference in the role of nitric oxide in CM secretion. Our data lead us to speculate that GLP-2 stimulates pulsatile activity of the mesenteric lymph ducts to propel CMs into the circulation given the rapid stimulation of mesenteric lymph flow. This concept remains only a hypothesis for now.

Beyond the gut, GLP-2 has effects on the liver and brain. GLP-2R expression has been identified in hepatic stellate cells, gallbladder, hypothalamus and brainstem (150,151). Intraperitoneal GLP-2 increased fasting plasma TG and VLDL without changing hepatic lipid content in chow-fed hamsters, although increased hepatic lipid content was noted in mice (69). When hamsters and mice were challenged with a high-fat diet to induce hepatic steatosis, GLP-2 treatment further exacerbated hepatic lipid accumulation (69). In contrast, other studies showed hepatoprotective effects of GLP-2 with reductions in markers of hepatic inflammation in mice (70). More recently, Fuchs et al found that whole body GLP-2R knockout did not modulate the development of hepatic steatosis on a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet (151). However, when animals were maintained on a chow diet, GLP-2R absence resulted in greater hepatic lipid and cholesterol content and increased hepatic inflammation. In this study, GLP-2R was not identified on isolated hepatocytes but was found on hepatic stellate cells—pericytes found around the space of Disse. They noted increased activation of stellate cells, which may be responsible for increased hepatic lipid accumulation in GLP-2R knockout animals. Interestingly, stellate expression of GLP-2R was upregulated by obesogenic diets, suggesting GLP-2R abundance may itself be a mechanism by which nutritional factors influence hepatic function (151).

In summary, pharmacological GLP-2 administration rapidly and robustly increases intestinal CM secretion in humans and animal models (Table 1). This occurs through indirect mechanisms due to a lack of GLP-2R on enterocytes. Our data in aggregate lead us to speculate that GLP-2 acts extracellularly to rapidly and robustly mobilize preformed CM, including many hours after fat ingestion. We are interested in further exploring whether GLP-2 enhances intestinal lipid and lipoprotein mobilization by stimulating lymphatic pumping. Thus far, all effects of GLP-2 on intestinal lipid mobilization have been described in response to pharmacological GLP-2 administration. It is still not known whether endogenously secreted GLP-2 plays a physiological role in stimulating intestinal lipid mobilization. We are currently conducting experiments to examine this issue. Effects of GLP-2 on VLDL secretion have not been demonstrated in humans and have been contradictory in animal models. Recent evidence suggests that modulation of hepatic lipid metabolism may be mediated by GLP-2R on hepatic stellate cells rather than direct effects on hepatocytes. It is very interesting to speculate on the evolution of 2 gut peptides GLP-1 and GLP-2, derived from the same proglucagon gene and secreted in equimolar quantities, having opposite regulatory effects on CM secretion.

Ghrelin, cholecystokinin, and peptide YY

These hormones secreted by the stomach and intestine have thus far been investigated in relation to lipoprotein metabolism primarily in vitro and in animal models and existing evidence that they are important regulators of lipoprotein secretion is less convincing than the evidence in support of GLP-1 and GLP-2. Further studies, however, may reveal these peptides to have important physiological roles in lipoprotein secretion. Here we summarize what is known to date with the caveat that further research may reveal greater relative importance of these hormones.

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is produced predominantly by enteroendocrine cells in the gastric fundus, as well as enteroendocrine cells in the small intestine and neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Emerging evidence from animal models suggests acyl ghrelin influences intestinal lipid handling.

To assess the effects of ghrelin on intestinal lipid metabolism, Auclair et al investigated chronic subcutaneous acyl ghrelin administration in chow- and Western diet-fed hamsters (71). Under both dietary conditions, acyl ghrelin did not significantly alter TRL-TG or apoB48 levels after oil gavage. However, acyl ghrelin reduced jejunal total CLD area and numbers in both chow- and Western-diet fed groups and decreased average CLD size only in the Western-diet fed animals. The authors suggest that acyl ghrelin could potentiate mobilization of CLD and target FAs toward beta-oxidation rather than CM secretion. Acyl ghrelin reduced lipid absorption in cultured enterocytes, suggesting that it may potentiate lipid transport through the portal circulation, bypassing enterocyte lipid handling; however, this theory requires further investigation (71).

Ghrelin might also influence hepatic VLDL secretion through effects on the brain. In mice, ICV ghrelin reduced hepatic TG content through regulation of genes involved in lipid metabolism (72). Decreased hepatic TG content coincided with increased expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a, a key protein involved in FA beta-oxidation, and decreased expression of FA synthase, a protein involved in de novo lipogenesis (72). Considering that ghrelin is elevated in times of negative energy balance, increased hepatic VLDL secretion would be an unsurprising response; however, this has not been directly investigated.

Ghrelin is well-described as an orexogenic peptide secreted by enteroendocrine cells of the stomach. Our understanding of ghrelin-mediated regulation of lipoprotein metabolism is limited but may involve direct modulation of enterocyte lipid handling and neural networks that influence hepatic lipid metabolism (Table 1). Further research in humans is required to understand its clinical relevance to intestinal and hepatic lipoprotein production.

Cholecystokinin

Cholecystokinin, secreted by enteroendocrine I cells in response to luminal lipid or protein, stimulates secretion of bile and pancreatic lipases to aid digestion and absorption of FAs and cholesterol. In vitro studies demonstrate that exogenous CCK stimulates CD36-mediated FA uptake in primary mouse enterocytes (73). Whole-body CCK knockout mice had delayed apoB48 secretion and lipid transport in the mesenteric lymphatics (74).

In mice, administering intravenous CCK along with oil gavage increased cholesterol levels compared to oil gavage alone but did not affect plasma TG. This led the authors to speculate that CCK increased cholesterol content of CMs with no effect on lipid content or apoB48 levels (75). CCK may influence cholesterol absorption through stimulation of Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) translocation to the cell surface in vitro without affecting NPC1L1 expression (76). Along with increased cholesterol transport capacity, CCK also stimulates bile release into the intestinal lumen thereby increasing the availability of biliary cholesterol to be absorbed by enterocytes (75).

CCK knockout mice also have altered hepatic lipid metabolism with reduced liver weight and TG content when maintained on a high-fat diet (74) (Table 1). In addition, antagonism of both CCK receptors prevented or reversed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice (77). Whether effects of CCK on hepatic lipid metabolism regulates VLDL secretion and whether these effects are mediated through central mechanisms warrant further research.

Peptide YY

Peptide YY is secreted in proportion to energy intake from fat and protein by enteroendocrine L cells that exist predominantly in the distal small intestine and colon (152). Peptide YY (PYY)1-36 is cleaved by dipeptidyl peptidase IV, generating the active form PYY3-36 which has been shown to reduce food intake and body weight in rodents (78). Evidence of effects on CM production is limited to in vitro experiments and remains to be explored in vivo. Apical delivery of PYY1-36 to Caco-2 cells decreased cholesterol incorporation into secreted lipoproteins through reduced NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol absorption. In contrast, basolateral administration reduced apoB48 and apoB100 synthesis and reduced CM secretion (79) (Table 1). In regard to hepatic lipoprotein secretion, intravenous PYY3-36 infusion, which antagonizes hypothalamic NPY, had no effect on VLDL-TG or VLDL-apoB secretion in mice (36).

Whether PYY modulates VLDL or CM secretion in humans is unknown, and further in vivo and in vitro research in humans and animal models is required to assess the therapeutic potential of PYY for disorders of lipoprotein metabolism.

Nutritional signals

Dietary or endogenously mobilized nutrients elicit a broad range of metabolic responses. Luminal fat is the major stimulus for CM secretion and FFA flux is a major driver of hepatic VLDL secretion (153,154). Interestingly, CM secretion is also stimulated by circulating FAs with experimentally induced elevation of plasma FFAs shown to stimulate CM secretion in rodents and humans (27,28). In vitro, FAs applied to the basolateral side of enterocytes and 3-dimensional enteroids contribute to formation of CLDs and may influence CM secretion (155,156). It is less well appreciated, however, that dietary carbohydrate also has an important effect in enhancing intestinal fat mobilization and CM secretion (157), along with well-known stimulation of VLDL secretion (158). We have shown that enterally infused glucose and fructose both enhance lipid-stimulated CM particle secretion and that raising plasma glucose concentration in humans by infusing glucose intravenously also stimulates CM secretion (80,159). These effects occurred in the presence of a pancreatic clamp, demonstrating that the monosaccharides themselves have a major effect on modulating intestinal CM secretion in the healthy state, independent of their effects on insulin and glucagon. In the late postprandial period, glucose can trigger mobilization of intestinal lipid stores, as evidenced by oral glucose mediated mobilization of enterocyte CLDs 5 h after an oral fat load in humans and increased lymph TG output in rats (66,81). We have recently shown that glucose must be metabolized to exert its intestinal lipid mobilizing effect (unpublished observations).

Nutrients may also modulate lipoprotein secretion indirectly via CNS activation. In animal models, ICV glucose has been shown to modulate hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. Lam et al demonstrated that increasing hypothalamic glucose concentration by 70% through ICV glucose infusion decreased plasma TG concentrations and VLDL secretion in rats, independent of plasma insulin levels (82). Coinfusion of glucose or lactate with a lactic dehydrogenase inhibitor or an inhibitor of KATP channels abolished this effect. In addition, glucose-mediated inhibition of VLDL secretion was dependent on an intact hepatic branch of the vagus nerve. The authors speculated that lactate generated by glycolysis within hypothalamic astrocytes is used to generate pyruvate within neurons, which ultimately activates KATP channels on the vagal nerve to suppress hepatic VLDL secretion. Interestingly, CNS glucose selectively decreased secretion of large VLDL1 particles with no effect on apoB100/B48 secretion or MTP expression. In addition, hepatic lipid content and abundance of lipogenic enzymes was not affected. However, ICV glucose markedly decreased hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1) activity and oleyl-CoA levels, which would decrease lipidation of nascent VLDL particles, thereby decreasing secretion of large VLDL particles without altering intracellular lipid content (82). To investigate this mechanism in humans, Sondermeijer et al performed a lactate clamp in normolipidemic subjects to sustain lactate levels at twice the physiological level for 7 h (160). Intravenous lactate is known to cross the blood-brain barrier and can influence neural function through the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (82). In contrast to the aforementioned findings in rats, the 7-h lactate clamp in humans increased VLDL-TG secretion, especially in the large VLDL1 particle fraction (160). This occurred with increased SCD1 activity in contrast to lower SCD1 activity observed in rats. This highlights the difficulty in extrapolating research on CNS regulation of peripheral metabolism from animal models to humans and confirms the need for rigorous investigation in humans to establish clinical relevance.

Other nutritional factors have shown modulation of hepatic lipoprotein metabolism through effects on the CNS. The amino acid glycine normalizes VLDL secretion in high-fat fed rats when infused directly into the DVC. This effect required intact hepatic vagal nerves and signaling through NMDA receptors within the DVC (32) (Table 1). To our knowledge, this effect has not been explored in humans.

Upper intestinal long-chain FAs (LCFAs), specifically LCFA-CoAs, have been shown to suppress hepatic glucose production via a gut-brain-liver axis involving afferent vagal signaling from the gut to NTS and NMDA-mediated efferent signaling to the liver in rats (130). To explore the effect of LCFAs on hepatic VLDL secretion, Yue et al infused oleic acid into the MBH of rats (31). Compared to saline infusion, oleic acid decreased VLDL-TG secretion assessed in the presence of LPL inhibition (31). This effect was abolished by concurrent infusion of rottlerin, a protein kinase C-delta inhibitor, demonstrating requirement of hypothalamic protein kinase C-delta signaling to activate KATP channels on efferent vagal neurons. Similar to the mechanisms by which ICV glucose decreased VLDL-TG secretion (82), MBH oleic acid did not affect hepatic TG content but inhibited SCD1 activity. The authors proposed that an MBH-DVC-hepatic vagal nerve circuitry underlies this oleic acid mediated regulation of VLDL-TG secretion (82) (Table 1). In light of previous findings of DVC glycine-mediated suppression of VLDL-TG secretion, the authors explored whether DVC glycine and MBH oleic acid would have additive effects on hepatic VLDL-TG secretion but did not find evidence for an additive effect (31). This study demonstrates that hyperlipidemia can be sensed by central tissues leading to reduced VLDL-TG secretion. A possible brain-gut axis to modulate CM secretion by a similar mechanism was not explored in this study.

In summary, not only fat but other macronutrients as well are major drivers and modulators of hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion, acting both directly on liver and intestine and indirectly via neural networks. There is still much to learn about the mechanism by which for example carbohydrates modulate intestinal lipid mobilization and CM secretion with implications for public health nutritional guidelines. Further research is required to elucidate the role of the brain in modulating hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion in response to endogenous and exogenous nutrients and how this is affected by metabolic health. We have good evidence for the existence of a neural signaling pathway from CNS to liver via the vagus nerve but currently understand very little about the signaling pathways that link nerves to metabolic pathways in the liver.

Microbiota

Numerous associations have been made between the gut microbiome and host health, implicating dysbiosis as a causal factor in components of the metabolic syndrome, including elevated plasma TG concentrations (83). Complete depletion of the gut microbiome in germ-free mice results in decreased dietary lipid digestion and absorption as well as decreased CM secretion (84). Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbes influence hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein production through modulation of lipid digestion, composition, and absorption (83). Indirectly, microbial populations can influence lipid metabolism through shifts in the profile of SCFAs, absorption of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and production of secondary bile acids.

Gut microbial depletion via antibiotic treatment or complete absence of microorganisms in germ-free mice are models commonly used to investigate underlying mechanisms of microbiome-mediated alteration of lipoprotein secretion. Intestinal lipid absorption is impaired in germ-free mice as shown by elevated fecal TG (85) and impaired appearance of orally ingested or gavaged lipids (84), in line with observations that antibiotic treatment reduced lymphatic transport of TG and phospholipids in rats (86). Martinez-Guryn et al attributed decreased lipid absorption in germ-free mice in part to decreased pancreatic CCK receptor expression leading to decreased duodenal lipase activity (84). They also observed upregulation of jejunal PPARα suggesting activation of genes involved in FA oxidation might also contribute to reduced CM secretion. In addition, the authors pointed to duodenal diacylglycerol o-acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2), an acyltransferase critical for TG synthesis and storage, as one example of an enzyme that is modulated by the gut microbiome because high-fat feeding induced DGAT2 expression in specific-pathogen-free mice but not in germ-free mice. A specific microbial strain (Clostridium bifermentans) given to antibiotic-treated specific-pathogen-free mice selectively increased the expression of DGAT2 but not DGAT1, suggesting soluble mediators or components from this microbe can specifically modulate host gene expression.

Gut microbial depletion studies indicate that dramatic shifts in the gut microbiome modulate intestinal and hepatic lipid metabolism. However, how specific commensal bacterial species influence digestion, absorption, storage, and secretion of dietary lipids remains an active area of research. Through complementary in vitro and in vivo studies, Tazi et al demonstrated that 2 specific microbial strains decreased CM secretion by differing mechanisms. The Gram-positive species Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) decreased FA absorption and shifted newly synthesized TG toward storage in CLDs. In contrast, Gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) enhanced FA absorption, but also enhanced FA oxidation, leading to reduced TG synthesis, CLD size, and CM secretion (87). In a follow-up study, they identified fermentation products as key modulators of these effects. L. paracasei produced L-lactate, which was converted into malonyl-CoA within enterocytes, leading to suppressed FA oxidation and increased storage of lipids as CLDs. In contrast, acetate produced by E.coli enhanced FA oxidation through upregulation of AMPK/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha/PPARα signaling (88). The authors suggest that these metabolites might differentially regulate lipases and structural proteins of the CLDs to shift TG toward storage or oxidation, although this remains to be proven (88). Therefore, the relative abundance of various microbial species within the microbiota can alter CM secretion through changes in FA absorption, storage, oxidation, and secretion.

Oral antibiotic exposure that shifts gut microbial populations can also alter hepatic lipid metabolism. In mice, 6 weeks of antibiotic treatment increased hepatic lipid accumulation with increased expression of genes involved in FA synthesis and transport and TG synthesis, including increased SREBP1c, DGAT1, DGAT2, and MTP (89) (Table 1). Dysbiosis, characterized by an imbalance and decrease of diversity in the gut microbiome, can increase intestinal permeability allowing pathogenic bacterial components like LPS to reach the liver and induce inflammatory and lipogenic pathways. Kim et al demonstrated that high-fat diet-induced dysbiosis in mice was mitigated by dietary supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila, decreased inflammatory markers, lowered serum TG, and decreased hepatic expression of lipogenic SREBP (161).

In humans, gut bacterial populations can be divided into 5 main phyla—Firmicutes, Bacteriodetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. Several studies have observed that microbial diversity and richness are negatively correlated with body mass index and TG in humans (162). Unlike in animal models, the Firmicutes:Bacteriodetes ratio has not consistently been linked to obesity and T2D (163). Altered production of SCFAs might be a more accurate marker of metabolic health in humans. Higher fecal SCFA levels of acetate, propionate, and butyrate have been associated with obesity (164). In particular, higher fecal butyrate has been associated with higher plasma TG and VLDL cholesterol (165). Increased fecal SCFAs may be secondary to gut dysbiosis and inflammation that lower SCFA absorption efficiency. SCFAs stimulate PYY and GLP-1 secretion from Lcells through activation of GPR41 and GPR43 receptors and thus may indirectly influence lipoprotein secretion and appetite. Unfortunately, few randomized controlled trials in humans have evaluated the effect of specific probiotic strains on lipoprotein production. A meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials involving Lactobacillus supplementation in humans failed to demonstrate improvement in plasma TG despite a significant reduction in total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol (166). In one study, supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila showed some promise to improve dyslipidemia in patients with T2D. Three months of daily supplementation with this single strain improved insulin sensitivity and reduced insulinemia and total cholesterol in overweight/obese patients with untreated T2D (90).

Lipopolysaccharide, a cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria, induces gut inflammatory responses that contribute to metabolic endotoxemia. In rats, LPS acutely inhibited intestinal FA absorption through lower expression of key FA transporters CD36 and FATP4 resulting in decreased plasma TG (167). Conversely, circulating LPS is found predominantly bound to CMs which can serve to neutralize the inflammatory effect of LPS (168). Obese states and high fat feeding induced hyperchylomicronemia can increase the total LPS burden, contributing to postprandial endotoxemia and inflammatory responses in humans and animal models (168,169). Thus, gut dysbiosis, which increases availability of LPS, and obesity, which increases CM production, together contribute to inflammation, hyperlipidemia, and increased risk of atherosclerotic CVD.

In summary, there is convincing evidence that the composition in intestinal microbiota influence intestinal lipid availability and lipoprotein secretion, as well as whole body metabolism with effects on hepatic lipoprotein secretion. Reductionist experiments in which individual components of the microbiome are altered or major disruption of the microbiome is induced are challenging to interpret given their nonphysiological nature. We currently lack an integrative understanding of the role that the microbiome plays in regulating hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein secretion.

Bile acids

Another important factor to consider in the relationship between microbiota and lipid metabolism and lipoprotein production is bile acids. Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver, stored in the gall bladder, and subsequently released into the intestinal lumen where their primary role is to emulsify dietary fat. They also serve as signaling molecules, binding to numerous bile acid receptors including the Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) found on the cell membrane and the nuclear receptor FXR (170). The primary bile acids, cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid, are converted to secondary bile acids, namely lithocholic acid and deoxycholic acid (DCA), by specific enzymes including bile salt hydrolase (BSH). BSH is abundant in the gut and is expressed by various gut microbes including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, and Bacteriodes (171). Alterations in the gut microbial populations can therefore alter the abundance of BSH and change the proportions of primary and secondary bile acids.

Recently, Farr et al demonstrated reduction of postprandial lipemia in mice by intraduodenal taurocholic acid, DCA, and synthetic agonism of FXR (91). Intraduodenal taurocholic acid, a bile acid that is abundant in the intestinal lumen, decreased plasma TG and TRL-TG with decreased TG in the jejunum and jejunal lumen, suggesting less availability of TG for absorption. The secondary bile acid DCA, a potent TGR5 agonist, also reduced postprandial TG, with increased luminal TG and increased jejunal MTP activity (91).

FXR agonism by GW4064 decreased postprandial TG with reduced intestinal TG content and MTP activity and increased expression of beta-oxidation genes suggesting retargeting of FA toward catabolism rather than inclusion in CM particles (91). The discovery of FXR and TGR5 expression on enteroendocrine L cells has led to the exploration of bile acids as a GLP-1 secretagogue. In individuals with T2D, the bile acid sequestering agent sevelamer negated the ability for endogenous bile acids to trigger GLP-1 secretion (172). Conversely, intestine-specific FXR agonism with fexaramine increased GLP-1 secretion in mice, which improved insulin and glucose tolerance (173). Farr et al investigated the response to GLP-1 receptor agonist exendin-4 in FXR knockout animals. GLP-1 retained its ability to acutely suppress postprandial lipemia in FXR deficiency, demonstrating that GLP-1 does not signal through FXR to suppress CM secretion (91).

Bile acid supplementation can alter microbial populations and induce metabolic changes in the host (174). Eight weeks of CA supplementation in high-fat fed mice decreased plasma TG primarily by decreasing VLDL-TG (Table 1). This coincided with decreased hepatic TG accumulation and decreased expression and activity of the lipogenic transcription factor SREBP1-c. FXR activation by CA and other agonists increased levels of the nuclear receptor short heterodimer partner, which reduced SREBP1-c expression (92). In addition, hepatocytes cultured with chenodeoxycholic acid had decreased FXR mediated MTP expression leading to decreased apoB secretion (175). Interestingly, fexaramine-mediated stimulation of FXR induced shifts in microbial populations and the benefits of FXR agonism were reversed by antibiotic treatment demonstrating the integral role of the gut microbiome to the response to FXR agonism in the intestine (173).

Signals Originating From Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue plays an important role in lipid metabolism by acting as a transient lipid storage site that is in constant flux depending on whole-body energy status. In lean states, subcutaneous depots in the trunk and gluteo-femoral regions make up approximately 80% of all adipose tissue (176). In obesity, lipid storage capacity of these depots can be exceeded leading to expansion of visceral adipose tissue and ectopic lipid deposition in muscle and liver. Metabolically unhealthy obesity with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance is typically attributed to expansion of visceral adipose tissue (177-179) and accompanied by adipose tissue dysfunction. This includes a host of changes including infiltration by inflammatory cells such as macrophages (180), altered adipokine and hormone secretion (181) and enhanced FFA efflux. Aging also induces adipose expansion due to reduced physical activity, chronic positive energy balance, and a lower basal metabolic rate (182). These changes contribute to a higher risk for atherosclerotic CVD with aging. For further information, we direct the reader to extensive reviews on adipose dysregulation due to aging and obesity (153,183-185).