Abstract

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) invited the manufacturer (Gilead) of filgotinib (JyselecaTM), as part of the single technology appraisal process, to submit evidence for its clinical and cost effectiveness for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd, in collaboration with Maastricht University Medical Centre, was commissioned to act as the independent Evidence Review Group (ERG). This paper summarises the company submission (CS), presents the ERG’s critical review of the clinical- and cost-effectiveness evidence in the CS, highlights the key methodological considerations, and describes the development of the NICE guidance by the NICE Appraisal Committee. The evidence for filgotinib was based on two good-quality international randomised controlled trials. In FINCH 1, filgotinib was compared with placebo, and in FINCH 2, filgotinib was compared with adalimumab and placebo. As there was no head-to-head evidence with most active comparators, the company performed two separate network meta-analyses (NMAs), one for the conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs–inadequate response population and one for the biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs–inadequate response population. The outcomes analysed were American College of Rheumatology response criteria at weeks 12 and 24, and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria at 24 weeks. The statistical methods used to perform the NMAs were valid and were in line with previous NICE appraisals. Results of the NMAs are confidential and cannot be reported here, but they were uncertain due to heterogeneity of the included studies. The economic analysis of the patient population with moderate RA suffered from limited evidence on the progression from moderate to severe health states. For the moderate RA population, the final analyses comparing filgotinib, with or without methotrexate, against standard of care resulted in incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of around £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained in the company’s and ERG’s base-case and scenario analyses. NICE recommended filgotinib in combination with methotrexate or as monotherapy when methotrexate is contraindicated, or if people cannot tolerate it, for patients with moderate RA whose disease had responded inadequately to two or more conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). For the severe RA population, in view of the higher or similar net health benefits that filgotinib provided versus its comparators, NICE recommended filgotinib with or without methotrexate for patients whose disease had responded inadequately to two or more conventional DMARDs, who had been treated with one or more biological DMARDs, if rituximab was not an option, or after treatment with rituximab.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Filgotinib is the first biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) that has been recommended for use in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in the England and Wales National Health Service. |

| The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of filgotinib versus its comparators were around £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained in the moderate population; in the severe population, filgotinib provided similar or higher net health benefits compared with its comparators. |

| Evidence for rates of progression from moderate to severe RA and subsequent treatment sequences was not readily available but remains crucial for the modelling of cost-effectiveness of biological DMARDs for the treatment of moderate RA. |

| RA appraisals and other appraisals with a large number of comparators and potential treatment sequences would benefit from methodological guidance on how to incorporate these in economic models. |

Introduction

Filgotinib, tradename JyselecaTM, was appraised within the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) single technology appraisal (STA) process. Health technologies must be shown to be clinically effective and to represent a cost-effective use of National Health Service (NHS) resources in order to be recommended by NICE. Within the STA process, the company (Gilead) provided NICE with a written submission and a mathematical health economic model, summarising the company’s estimates of the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of filgotinib for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This company submission (CS) was reviewed by an Evidence Review Group (ERG) independent of NICE. The ERG, Kleijnen Systematic Reviews in collaboration with Maastricht University Medical Centre, produced an ERG report [1]. After consideration of the evidence submitted by the company and the ERG report, the NICE Appraisal Committee (AC) issued guidance on whether or not to recommend the technology by means of the Final Appraisal Determination (FAD), to which an appeal can be made. This paper presents a summary of the ERG report and the development of the NICE guidance. Furthermore, it highlights important methodological issues that were identified that may help in future decision making.

Full details of all relevant appraisal documents (including the appraisal scope, CS, ERG report, consultee submissions, technical engagement, FAD and comments from consultees) can be found on the NICE website [1].

The Decision Problem

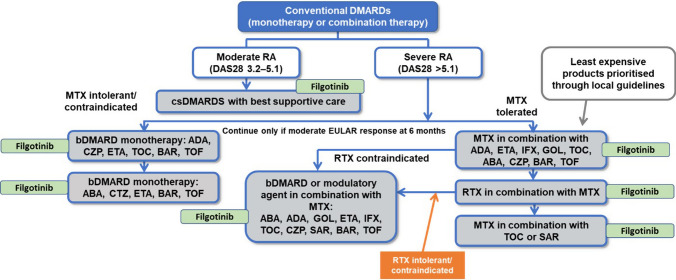

The CS defined the population as “adults with moderately to severely active RA whose disease has responded inadequately to two or more conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), or who are intolerant to DMARDs, including conventional or biologic DMARDs”. The current treatment pathway and the company’s proposed positioning of filgotinib is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

RA treatment pathway with the company’s proposed positioning of filgotinib. Courtesy of the company submission. ABA abatacept, ADA adalimumab, BAR baricitinib, CZP certolizumab pegol, DAS Disease Activity Score, DMARDs synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; ETA etanercept, EULAR European League Against Rheumatism, GOL golimumab, IFX infliximab, MTX methotrexate, RA rheumatoid arthritis, RTX rituximab, SAR sarilumab, TOC tocilizumab, TOF tofacitinib

The population in the CS differed from the population defined in the NICE scope, which was broader, including also adults with moderately to severely active RA whose disease has responded inadequately to one or more conventional DMARDS (cDMARDs) or who are intolerant to DMARDs, including conventional or biologic DMARDs. In addition, it is important to note that most patients in the two main trials had severely active RA (28-joint Disease Activity Score [DAS28] > 5.1); approximately 24% and 21% of patients in the FINCH 1 [2, 3] and 2 [4, 5] trials, respectively, had moderate disease. Therefore, results from both trials are more reliable for the severely active RA population but less reliable for patients with moderately active RA.

The comparators in the CS were not in line with the NICE scope. Several relevant comparators mentioned in the scope were not included in the network meta-analysis (NMAs) that was part of the CS, partly because of a lack of data. As a result, the comparators not included in the NMA have also not been included in the economic model.

The selection of comparators in the model provided by the company may not have been appropriate; potentially relevant comparators certolizumab pegol, tofacitinib (in most populations), golimumab and infliximab were not included. The ERG considered that market share data and the opinion of one expert (for golimumab and infliximab) were likely insufficient justifications; however, infliximab is now rarely used and its exclusion could be appropriate. Golimumab was also excluded by the company because no 24-week assessment data were available. Data for certolizumab pegol and tofacitinib were not included in the NMA in the relevant populations or at the 24-week assessment time point. The ERG considered that these comparators may have been inappropriately excluded, possibly resulting in cost-effectiveness results being biased.

Independent Evidence Review Group (ERG) Review

The ERG reviewed the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence of filgotinib for this indication. As part of the STA process, the ERG and NICE had the opportunity to ask for clarification on specific issues in the CS, in response to which the company provided additional information [1]. The ERG also produced an ERG base-case to assess the impact of alternative assumptions and parameter values on the model results, by modifying the health economic model submitted by the company. Sections 3.1–3.6 summarise the evidence presented in the CS, as well as the review of the ERG.

Clinical Effectiveness Evidence Submitted by the Company

The company’s clinical evidence came from two randomised controlled trials in people with moderate to severe RA:

FINCH 1 enrolled patients with inadequate disease response to methotrexate. A total of 24% of patients had moderate disease and 76% had severe disease. Filgotinib was used with methotrexate and the comparators were adalimumab with methotrexate or placebo with methotrexate [2, 3].

FINCH 2 enrolled people with inadequate disease response or intolerance to at least one biological DMARD. A total of 21% of patients had moderate disease and 79% had severe disease. Filgotinib was used with conventional DMARDs and the comparator was placebo with conventional DMARDs [4, 5].

In FINCH 1 [2, 3], filgotinib with methotrexate showed a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint, American College of Rheumatology responses (ACR20) at 12 weeks, compared with adalimumab with methotrexate or placebo with methotrexate (76.6% compared with 70.5% and 49.9%, respectively; p < 0.05 for both comparisons). Filgotinib also showed improvement in key secondary endpoints at both 12 and 24 weeks, including ACR50, ACR70 or European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) responses. The NICE AC concluded that filgotinib with methotrexate was more clinically effective than adalimumab with methotrexate, or placebo with methotrexate, in people with moderate to severe disease that has responded inadequately to conventional DMARDs.

In FINCH 2 [4, 5], filgotinib with conventional DMARDs showed a statistically significant improvement in the primary outcome—ACR20 at 12 weeks—compared with placebo with conventional DMARDs (66.0% compared with 31.1%; p < 0.05). Filgotinib also showed improvement in key secondary endpoints at both 12 and 24 weeks, including ACR50, ACR70 or EULAR responses. The NICE AC concluded that filgotinib with conventional DMARDs was more clinically effective than placebo with conventional DMARDs in people with moderate to severe disease that has responded inadequately to biological DMARDs.

Adverse events most frequently observed across the two trials were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, headache, nausea, and bronchitis. In FINCH 1 [2, 3], at week 24 (placebo-controlled period) a similar proportion of patients experienced serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in each treatment group (4.4% in the filgotinib 200 mg arm, 5.0% in the filgotinib 100 mg arm, 4.3% in the adalimumab arm and 4.2% in the placebo arm).

No clinical efficacy data are available for filgotinib monotherapy in people with moderate to severe disease that has responded inadequately to conventional or biological DMARDs. Therefore, the clinical efficacy of filgotinib monotherapy is uncertain.

A direct comparison was only possible with adalimumab, informed by the FINCH 1 trial, and with placebo, informed by both the FINCH 1 and FINCH 2 trials [2–5]. To compare with other biological and targeted synthetic DMARDs, the company conducted two NMAs for (1) people whose disease responded inadequately to one or more conventional DMARDs, and (2) people whose disease responded inadequately to one or more biological DMARDs.

The results showed that for both populations, filgotinib gave similar EULAR response rates to other biological and targeted synthetic DMARDs. Furthermore, filgotinib gave better EULAR response rates when compared with conventional DMARDs alone (the exact rates are confidential and cannot be reported here).

Critique of Clinical Effectiveness Evidence and Interpretation

A broad range of databases, conference proceedings and grey literature sources were searched by the company. Limiting searches to the English language may have introduced language bias.

The company used different inclusion criteria from the NICE scope. First, all monotherapy studies were excluded because the FINCH 1 and FINCH 2 trials did not have monotherapy arms [2–5]; however, the NICE scope mentions several monotherapy comparators that could still have been included. Second, the search was limited to studies after 1999, however many cDMARD studies were performed before this timeframe and therefore potentially relevant studies were excluded from the NMAs.

Baseline characteristics from the included studies showed that the number of patients per treatment arm ranged from 24 to 803. Mean age ranged from 46 to 58 years (not reported in 11 studies), and the percentage of male participants ranged from 4 to 56% (not reported in 10 studies). Mean disease duration ranged from 21 to 156 months (not reported in 13 studies). Mean DAS28 score at baseline ranged from 5.8 to 7.5 for DAS28-ESR and from 4.1 to 11.6 for DAS28-CRP (not reported in 16 studies). This shows that there were large differences between the included studies. The company did not provide a detailed summary of clinical heterogeneity, but stated that as there are published NMAs in RA, including those informing previous HTA, “a formal feasibility assessment was not conducted, and the homogeneity of the trials was deemed sufficient to conduct the analysis” [6]. The ERG requested additional evidence for this statement but a response was not received [7].

The statistical methods used to perform the NMAs are valid and are in line with previous NICE appraisals [8]. However, the primary endpoint for both FINCH 1 and FINCH 2 was the proportion of patients achieving a 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response (ACR20) at week 12. This is a very weak endpoint for a lifelong condition. In addition, comparative evidence from the FINCH 1 and FINCH 2 trials is only available for 24-week follow-up, which is very short for a condition that may last 30 years [2–5].

Cost-Effectiveness Evidence Submitted by the Company

A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to identify published economic evaluations in moderate to severe RA to address the decision problem and inform the economic model structure. None of the economic evaluations in RA provided relevant effect estimates, i.e. effectiveness of filgotinib versus relevant comparators, for estimating the cost effectiveness of filgotinib in RA. The company identified previous cost effectiveness models used for NICE TAs and used these to inform modelling choices [8].

The company built a discrete event simulation (DES) model, consistent with previous multiple technology appraisal on RA drugs (MTA375) [9], as well as subsequent submissions in RA. Patients were sampled at random from the provided patient population (based on the patient baseline characteristics in the FINCH clinical trial programme).

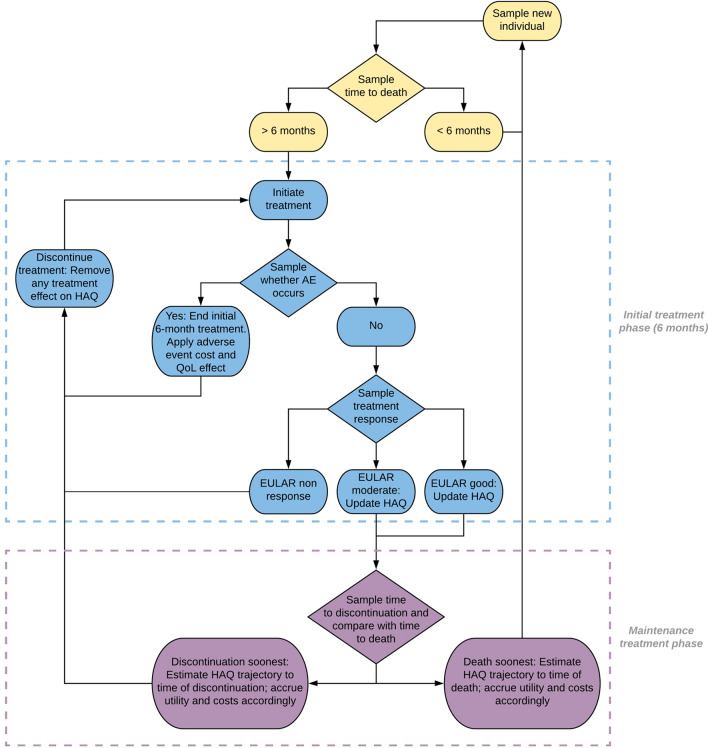

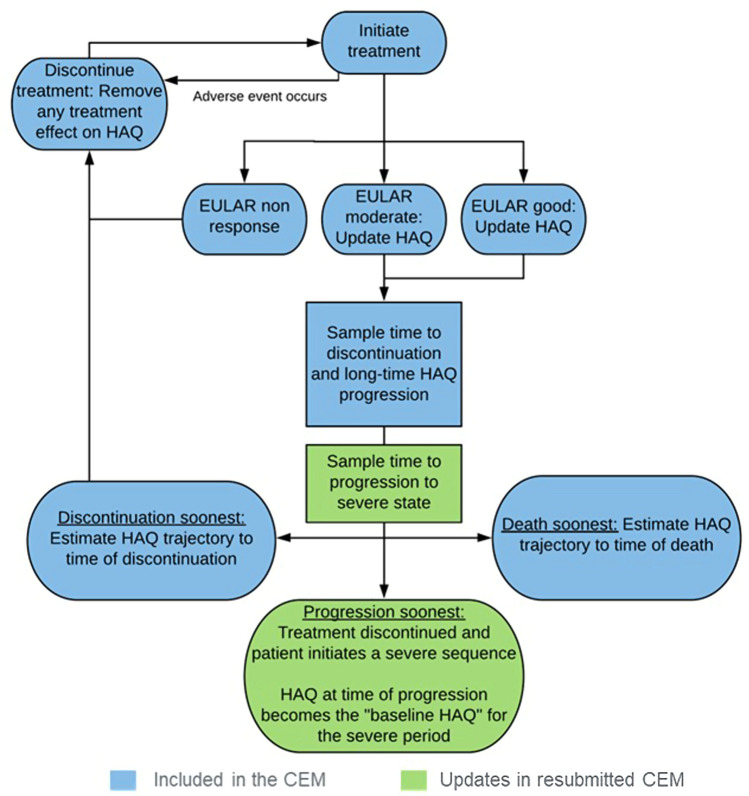

Each patient was simulated through the following process: (1) patient time to death was calculated; (2) only patients alive at 6 months experienced the initial treatment phase of 6 months, after which they either continued treatment or discontinued treatment if they did not achieve a good or moderate EULAR response; (3) patients entered the maintenance treatment phase upon achieving a good or moderate EULAR response; (4) patients discontinued treatment based on sampled time to discontinuation; and (5) patients started subsequent treatment (Fig. 2). Upon request by the ERG, the company implemented a functionality in the model that allowed patients with moderate RA to progress to severe RA and therefore become eligible for treatment with bDMARDs. To this extent, two steps were undertaken: (1) using patient-level trial data to estimate the relationship between change in DAS28 and change in the Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI); and (2) updating simulated patients’ DAS28 scores at every time point in the model based on their modelled HAQ-DI trajectory to determine when progression to the severe state occurred. The updated model structure for the moderate RA population is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Model structure for the severe RA population. Courtesy of the company submission. AE adverse events, EULAR European League Against Rheumatism, QoL quality of life, RA rheumatoid arthritis

Fig. 3.

Model structure for the moderate RA population. Courtesy of the company submission. EULAR European League Against Rheumatism, RA rheumatoid arthritis

The model adopted the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services. The model time horizon was lifetime. All costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per year.

The population in the CS was limited to “Adults with moderately to severely active RA whose disease has responded inadequately to two or more cDMARDs, or who are intolerant to DMARDs, including conventional or biologic DMARDs”. The cost-effectiveness analysis modelled patients with moderately to severely active RA, categorised into three subpopulations depending on their disease severity, line of treatment and tolerance to guideline-recommended treatments: moderate RA (DAS28 score of 3.2–5.1), patients who have had inadequate response to or are intolerant to csDMARDs (moderate cDMARD-IR); severe RA (DAS28 score of > 5.1), patients who have an inadequate response to csDMARDs only (severe cDMARD-IR); or severe RA (DAS28 score of > 5.1), patients who have an inadequate response to bDMARDs (severe bDMARD-IR). Based on NICE treatment guidelines (shown in Fig. 34 of the CS) [6], patients were further subcategorised by their eligibility for methotrexate and rituximab. Two patient populations were modelled for the use of filgotinib in moderate RA depending on eligibility for methotrexate. This resulted in 10 patient populations, which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparators and treatment sequences per population

| Population | Comparators | Sequences |

|---|---|---|

| 1a. Moderate RA, as monotherapy after two or more cDMARD failures in patients who are methotrexate ineligible | Placebo/BSC | 1 BSC |

| Upon progression to severe sequence 2a: | ||

| 1 Adalimumab | ||

| 2 Abatacept SC | ||

| 1b. Moderate RA, as combination therapy after two or more cDMARD failures in patients who are methotrexate eligible | Placebo/BSC | 1 BSC |

| Upon progression to severe sequence 2b: | ||

| 1 Adalimumab | ||

| 2 Rituximab | ||

| 3 Tocilizumab SC | ||

| 2a. Severe RA, as first-line advanced monotherapy therapy after failure of two or more cDMARDs in severe RA, for patients who are methotrexate ineligible | Adalimumab, etanercept, tocilizumab SC and baricitinib (each as monotherapy) | 1 Abatacept SC |

| 2 BSC | ||

| 2.b Severe RA, as first-line advanced therapy after failure of two or more cDMARDs | Adalimumab, etanercept, baricitinib (all + methotrexate) | 1 Rituximab + methotrexate |

| 2 Tocilizumab SC + methotrexate | ||

| 3 BSC | ||

| If rituximab contraindicated (IL-6): | ||

| 1 Tocilizumab SC + methotrexate | ||

| 2 BSC | ||

| If rituximab contraindicated (CD80): | ||

| 1 Abatacept SC + methotrexate | ||

| 2 BSC | ||

| 3a. After first-line advanced therapy failure | Abatacept SC, baricitinib and tofacitinib (each as monotherapy) | 1 BSC |

| 3b. After first-line advanced therapy failure in patients who are rituximab ineligible | Abatacept SC, baricitinib, sarilumab and tocilizumab SC (all + methotrexate) | 1 BSC |

| 4. After first-line advanced therapy failure in patients who are rituximab eligible | Rituximab + methotrexate | 1 Tocilizumab SC + methotrexate |

| 2 BSC | ||

| 5. After failure of rituximab in combination with methotrexate | Tocilizumab SC and sarilumab (all + methotrexate) | 1 BSC |

BSC best supportive care, cDMARD conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, CD80 cluster of differentiation 80, IL interleukin, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SC subcutaneously

Filgotinib is administered as monotherapy or in combination with other conventional DMARDs, including methotrexate, at the recommended dose of one 200 mg tablet once daily. A dose of 100 mg of filgotinib once daily was recommended for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance 15–30 mL/min). Comparators differed by the different populations, as identified above; for populations 1.a and 1.b, best supportive care (BSC) was the only comparator. BSC was assumed to comprise of cDMARD therapies (e.g. leflunomide or sulfasalazine), in line with MTA375. After discontinuation of filgotinib, other treatments can be used depending on the population of interest. Comparators for all populations and treatment sequences as modelled by the company are shown per population in Table 1.

Different sources informed treatment effectiveness in the cost effectiveness model. The NMA informed proportions of responders associated with the different treatments. Response rates were based on the EULAR response criteria as they were considered the preferred measurement of treatment response in UK clinical practice, and were recommended for use in NICE guidance [10]. Probabilities of reaching a EULAR response (non, moderate, or good) at 6 months (24 weeks) for filgotinib and comparators were estimated from the NMAs evaluating treatment response for RA treatment in both the cDMARD and bDMARD populations. Because in RA clinical trials the ACR response metric was commonly used, where necessary, ACR response rates were converted to EULAR response rates based on an approach developed by Stevenson et al., using US Veterans’ Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis (VARA) registry data where both measures were reported, as described and used earlier in MTA375 [9].

For some treatments, the efficacy could not be informed by the NMA and a number of assumptions were made:

It was assumed that BSC had no treatment effect (i.e. EULAR non-response).

It was assumed that monotherapy had the same relative effect across all treatments as combination therapy.

NMAs were not conducted separately by disease severity, because “results stratified by disease severity (for the moderate and severe population separately) are rarely reported” [6]. Therefore, it was assumed that the efficacy results from the NMA in the cDMARD-IR population were applicable for both patients in the moderate and severe populations.

For tocilizumab subcutaneous (SC) combination therapy in the severe cDMARD-IR population, efficacy was assumed equivalent to tocilizumab + methotrexate in the bDMARD-IR NMA.

For abatacept SC combination therapy in the severe bDMARD-IR population, efficacy was assumed equivalent to abatacept + methotrexate in the cDMARD-IR NMA.

For tofacitinib monotherapy in the severe bDMARD-IR population, efficacy was assumed equivalent to baricitinib + methotrexate in the bDMARD-IR NMA.

The FINCH clinical trial programme was used to derive patient baseline characteristics [2, 4, 5]. Where characteristics required for the model were not available from the clinical trials, values were taken from the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS) dataset as described by Norton et al. [11].

Long-term HAQ-DI progression was based on the data reported in the British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR) dataset used in MTA375, and on the data reported by Norton et al., for patients treated with bDMARDs and csDMARDs, respectively. Patient’s HAQ-DI score was assumed to reduce dependent on the initial treatment effect (i.e. moderate or good EULAR response) at the end of the 6-month initial treatment phase. In patients who showed no response, the HAQ-DI trajectory was assumed to be constant. The initial HAQ-DI value reduction was independent of treatments received. After the initial 6-month treatment phase, the change in HAQ-DI score was based on the treatment received (bDMARD or cDMARD). Treatment with a bDMARD resulted in an HAQ-DI trajectory based on that reported in the 36-month BSRBR dataset analysed by the Assessment Group (AG) in MTA375. The first 36 months of the trajectory were estimated using the autoregressive latent class trajectory model in MTA375, after which HAQ-DI was assumed to remain stable. Those patients receiving cDMARDs experienced a trajectory in HAQ-DI score based on the 15-year ERAS cohort data described by Norton et al. The estimates reported by Norton et al. were combined with patient baseline characteristics from the FINCH trials to define the long-term HAQ-DI trajectory for individual patients for 15 years following treatment with a cDMARD, after which HAQ-DI was assumed to remain stable.

Time to treatment discontinuation (TTD) was applied in line with MTA375. A generalised gamma distribution was used to extrapolate TTD, with parameters contingent on response (good or moderate). These parameters could not be directly derived from MTA375, but were obtained through digitisation of printed diagrams to obtain hypothetical individual patient data.

Age- and sex-specific mortality was based on all-cause survival data derived from UK life tables 2015–2017 [12]. Patients’ disease-related mortality was then based on baseline HAQ-DI score, applying HAQ-DI stratified hazard ratios (HRs), which were sourced from MTA375. For the reference case, patients with an HAQ-DI score of 0, only all-cause mortality was considered. For other patients, disease-related mortality was calculated using the HRs for survival stratified by HAQ-DI score.

The only adverse event considered was serious infection during the first 6 months of any active treatment. Rates of serious infections were based on those identified by Singh et al. [13], and were dependent on class of therapy. The company considered filgotinib to have a favourable safety and tolerability profile in patients with moderately to severely active RA.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assumed to be dependent on patient HAQ-DI score progression. Patients’ long-term HAQ-DI score trajectory was mapped to EQ-5D utilities based on a published mapping algorithm detailed by Hernandez-Alava et al. [14] using the four latent class model based on Norton et al. [11]. This algorithm used patients’ current age, sex, HAQ-DI and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain scores to determine a utility value at any point in the model. As VAS pain scores were not modelled over time, patients’ VAS pain score was estimated using their current HAQ-DI as the input for the mapping algorithm based on a polynomial curve. This curve, which was presented in MTA375, was digitised by the company and a ninth order polynomial curve was fitted to obtain the polynomial coefficients. For each AE occurrence, a decrement of 0.156 was applied to the patient’s overall utility, assuming that each patient experienced an AE for a total of 28 days of the 6-month period.

The model included costs for drug acquisition and administration, hospitalisation costs, and adverse event costs. Treatment costs provided in the model were based on UK costs and dosing regimens from MIMS 2020 [15]. Patient access scheme (PAS) or biosimilar prices applied for most treatments. For strategies where treatments are used in combination with methotrexate, the 6-monthly cost of methotrexate was added to the 6-monthly cost of the treatments. The cost of BSC was estimated from MTA375 and was argued to be reflective of healthcare costs for patients who are managed without targeted therapy. The cost of BSC was assumed to be similar to post-biologic cDMARD therapy (£360 per 6 months), while the cost of cDMARDs was assumed to equal the cost of methotrexate (£13.52 per 6 months). For drugs with weight-based dosing (e.g. tocilizumab), doses for patients were computed based on the simulated baseline weight of each patient. Treatment administration costs applied in the model were reflective of route of administration, dosing guidance in MIMS 2020 and the administration costs outlined in MTA375. Drug monitoring costs were modelled separately for the initial treatment (£1870.54) and maintenance (£884.66) phases and were sourced from MTA375. Hospital costs were broken down into six categories, according to HAQ-DI level, to reflect the increasing cost burden associated with worsening RA. Adverse event costs were informed by MTA375 (£1661.55). Costs were applied 6-monthly and were separated for initial treatment, consisting of the first 6 months of every treatment (including any loading doses), and maintenance treatment (after response at 6 months until time to discontinuation). All costs were inflated to 2018/2019 prices using the Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) Index and the NHS Cost Inflation Index (NHSCII) [16].

The company’s revised deterministic base-case analysis, which used the PAS for filgotinib but not the PAS or biosimilar prices for comparators, resulted in filgotinib being cost effective or dominating against some comparators, and cheaper and less effective than other comparators in all comparisons. In the comparison with rituximab in population 4, filgotinib was cheaper and less effective.

The company undertook several sensitivity and scenario analyses. Disregarding the time horizon and discount rate, the company’s results were most sensitive to the choice of method for estimating HAQ-DI progression, the choice of method for mapping utilities, hospital cost variations, variations in the efficacy of abatacept (populations 3.a and 3.b), variations in administration costs and source of AE rates (population 4), and variations in the efficacy of sarilumab (population 5).

Furthermore, the company performed probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) in all populations, using only 500 simulated patients (reduced from 10,000 in the deterministic analysis to save on computational time) and 1000 PSA runs.

Critique of Cost-Effectiveness Evidence and Interpretation

All Populations: Critiques of Cost-Effectiveness Searches

The company provided sufficient detail for the ERG to appraise the majority of the literature searches. A good range of databases and conference proceedings were searched, including additional grey literature resources and reference checking. Limiting searches to the English language may have introduced language bias.

All Populations: Generalisability of the Analyses to England and Wales Clinical Practice

The ERG was concerned about the generalisability of the analyses to the England and Wales clinical practice as well as to the targeted population. One concern was that the model analyses and efficacy estimates used in them did not reflect the population that the company targeted with their submission (patients who did not respond to at least two or more cDMARDs). The modelled population was a subset of the main clinical trials for this appraisal, the FINCH 1 and FINCH 2 trials. FINCH 1 included patients with inadequate response to one or more cDMARDs. In the model, inputs (e.g. response rates, patient baseline characteristics) based on FINCH 1 were not based on patients who did not respond to at least two or more cDMARDs. Second, moderate and severe populations were aggregated in the NMA and the ERG considered that results from the moderate to severe population may not be representative of the severe population. A subgroup analysis using only the severe population in FINCH 2 was requested. Response rates differed significantly in this population. Third, the company assumed equal effectiveness between monotherapy bDMARDs and combination therapy with methotrexate. Clinical experts noted that, generally, combination therapy is more effective, but the company’s assumption was in line with other RA appraisals.

All Populations: Issues with Relevant Comparators

For the severe RA population, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, upadacitinib, golimumab and tofacitinib were not included in the health economic model despite being included in the NICE scope as potentially relevant comparators. The company stated that the comparators included in the economic model were those deemed most relevant to UK clinical practice based on NICE treatment guidelines, market share data and through validation by a UK rheumatologist. Upadacitinib was not included because its appraisal was still ongoing. The ERG considered the company’s choices not fully justified. Market access data are not necessarily a reflection of clinical usefulness and only one UK rheumatologist’s opinion was asked. The ERG considered that there was a risk that potentially effective and cost-effective treatment sequences have been ignored. The ERG explored including alternative comparators in scenario analysis (including upadacitinib) but did not have NMA results available for certolizumab pegol. The company also provided additional scenarios using interleukin (IL)-6 inhibitors instead of abatacept in population 2a. These scenarios did not significantly change model outcomes.

For the moderate RA population, the ERG considered that BSC as defined by the company, which included the costs of palliative care, was not the appropriate comparator. The ERG preferred to use cDMARDs as the comparator, using cDMARD response rates from the placebo arm of the trial (instead of 0% response) to inform effectiveness, and cDMARD costs instead of subsequent BSC costs (which included palliative care).

All Populations: Treatment Effectiveness Considerations

The estimation of treatment effectiveness was largely in line with other technology appraisals in RA. One problematic assumption made by the company was that response rates obtained from the NMA were the same regardless of the line of treatment by which the therapy was administered. Furthermore, NMA response rates were also applied to the moderate population, where filgotinib was compared with cDMARDs, which in turn were assumed to have 0% effectiveness. The ERG considered that head-to-head trial data from FINCH 1 (subgroup analysis for moderate patients) comparing filgotinib with cMDARDs should be used instead. The company implemented this analysis at technical engagement. The ERG noted that the company continued to use ACR response rates mapped to EULAR response rates instead of using the EULAR response rates directly in this analysis. The ERG preferred using EULAR response rates directly and implemented this in its base-case.

To generate patient profiles, parameter values were sampled from their distribution independently. Independent sampling from distributions about parameters that are likely correlated could generate implausible patient profiles. According to clinical expert opinion and their review of real-world data, the potentially correlated parameters included DAS28, pain and HAQ scores (correlation coefficient of approximately r = 0.5), and sampling from these separately may produce some implausible patient profiles, albeit only a few.

All Populations: Issues with Health-Related Quality of Life Estimation

Initially, the ERG considered that estimation of HRQoL based on HAQ-DI and pain could potentially be biased because both pain and HRQoL were mapped based on HAQ-DI, and the pain VAS score mapping algorithm systematically and significantly underestimated the pain VAS score filled in by patients. At the technical engagement stage, the company corrected this and showed that mapped pain scores were approximately aligned with observed scores, and the ERG considered HRQoL estimates as appropriate. A further issue was that HRQoL may have been slightly overestimated for conventional and bDMARD therapies in the model compared with BSC. This was because patients not responding to treatment had stable utility values during the first 6 months, whereas patients’ health states in the BSC arm worsened from the start, given that BSC had a 100% non-response rate. When two identical patients were modelled in each arm of the model with identical treatment pathways (apart from having not responded to treatment with filgotinib), the patient in the filgotinib arm acquired slightly more QALYs due to the 6-month delay in health state worsening caused by treatment failure. This was considered only a minor issue and was resolved by using the head-to-head trial comparison in the moderate population. There was a minor issue in the model where the estimated utility values were set to 1 when the utility value exceeded 0.883. This was corrected in the ERG and subsequent company analyses.

All Populations: Model Implementation Considerations

The sampling of patient characteristics was considered problematic by the ERG: only 1000 profiles were generated, and the company sampled from this set of profiles 10,000 times. The ERG considered that this may underestimate heterogeneity in patients and that the model may not be as stable as suggested by the company’s convergence plots. The ERG preferred the use of a set of as many patient profiles as simulated patients to be able to assess model convergence. Furthermore, model run times were prohibitive for performing PSAs with a sufficient number of simulations in each patient population. Correlations between response rates were initially not taken into account (NMA results were not used directly, but instead means and standard errors were used), which was a limitation of the PSA. This issue was resolved in response to the clarification letter.

Moderate Population: Uncertainty About Progression from Moderate to Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis

The ERG considered that basing the model on that developed for MTA375 was reasonable, with one exception: the DAS28 score of patients modelled with moderate RA could not progress and modelled patients could therefore not become eligible for treatments reserved for the severe RA population (bDMARDs). The company addressed this in response to the clarification letter and added this functionality, as described above. As a starting point DAS28 score, the midpoint between the low disease and severe disease activity score thresholds (3.2 and 5.1, i.e. 4.15) was used. The ERG adjusted the company’s modelling by using the DAS28 score from the FINCH trial programme. The key issue was the uncertainty about the rate of progression from moderate to severe RA. The external evidence was limited and hampered validation efforts. One reference point was 19% of patients who had a DAS28 score of 3.2–5.1 in year 1 progressed to >5.1 at year 2, which was based on an analysis of the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Network (ERAN) database [17]. The company’s model resulted in only 5% of patients progressing to severe disease at year 2. The ERG’s preference for modelling the starting point DAS28 score based on FINCH resulted in a likely overestimation of the proportion of patients progressing to severe RA in year 2 (26%). In the final analysis in response to technical engagement, the company made further changes to the model (by using the head-to-head trial comparison to inform the moderate RA population rather than the NMA data, as described above) and the final rate of patients progressing at year 2 was 11%. The ERG noted that slower progression resulted in increased incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for filgotinib versus BSC. Quicker progression appeared to result in higher QALY gain (regardless of treatment arm), which was likely the result of patients being treated with bDMARDs upon progression, which improved their HRQoL.

Moderate Population: Issues with Relevant Treatment Sequences

The ERG was concerned that insufficient justification was provided for the company’s choice of treatment sequences and some important treatment sequences were left unexplored. The company assumed that once patients progressed to the severe RA health state, they received adalimumab, which the company stated was the most commonly used advanced therapy. This was associated with the smallest QALY gain as per the company’s cost-effectiveness analyses in population 2. The ERG preferred the use of etanercept, which provided the largest QALY gain. However, it was unclear whether treatment choice in clinical practice was based on minimising costs, maximising QALYs, or cost-effectiveness considerations. At technical engagement, several alternatives were explored for the third treatment line, following treatment with filgotinib or cDMARDs in the moderate population and adalimumab upon progression. Instead of abatacept, in population 1a the use of tocilizumab or sarilumab was explored, while in population 1b, following adalimumab and rituximab, the use of sarilumab and abatacept were explored. Furthermore, the use of filgotinib third line in population 1b was explored for patients in the comparator arm who had been treated with cDMARDs first line. All scenarios increased the ICERs. This illustrates that where there are many different treatment options in a subsequent line, these need to be considered in the modelling. On the other hand, the company highlighted that these scenarios did not evaluate the cost effectiveness of filgotinib compared with BSC, but rather evaluated the cost effectiveness of two different sequences, given the different treatment sequence ‘tails’. However, a comparison between filgotinib and BSC in the index population, regardless of which treatments follow, does provide for the evaluation of the cost effectiveness of filgotinib, as long as any such sequence is applied to both intervention and comparator according to rules that could be plausible in clinical practice. Such a sequence could include filgotinib on the understanding that it might be recommended for the severe population. There could also be variation in the sequences between intervention and comparator if treatments were chosen based on history, i.e. the use of one treatment precluded the use of another treatment in a later line. The ERG therefore considered these scenarios as relevant.

Moderate Population: Comparator Costing

The main concern about costs was that the comparator and subsequent treatment in the moderate population (which was referred to as BSC) was assumed to cost the same as BSC following bDMARD treatment (£360 per 6 months, including palliative care costs). The ERG preferred to apply the lower cDMARD costs (£13.52 per 6 months, based on the cost for methotrexate) for the comparator and subsequent treatment in the moderate population.

Additional Work Undertaken by the Evidence Review Group (ERG)

Based on all considerations highlighted in the ERG critique, the ERG defined a new base-case in which various adjustments were made to the company’s base-case.

For the moderate RA population, this included:

changing the costs of the comparator and subsequent treatment in the moderate population;

using the DAS28 score from the FINCH trials instead of the midpoint favoured by the company;

implementing alternative treatment sequences;

in both moderate and severe populations, assuming a constant VAS score (based on the trials) for utility estimation; this change was later abandoned given additional evidence presented by the company;

in scenarios, the ERG explored upadacitinib as comparator for severe populations 2a and 2b.

At technical engagement:

EULAR response rates were used instead of ACR response rates mapped from EULAR response rates in the head-to-head trial comparison;

further alternative treatment sequence scenarios were performed.

All cost-effectiveness analyses were presented in terms of the net health benefit rather than in terms of ICERs, in order to facilitate comparison between a large number of comparisons with small differences in QALYs and, in some cases, negative incremental QALYs. The ERG base-case resulted in no significant changes to the cost-effectiveness results calculated by the company; however, some alternative treatment sequence scenarios in the moderate population had a substantial impact on the ICERs at technical engagement. Particularly when filgotinib was added as a subsequent treatment in the comparator arm, the ICERs increased significantly.

Conclusions of the ERG Report and Technical Engagement

The company’s economic evaluation met most of the NICE reference case criteria, with the exception of probabilistic modelling: a sufficient number of simulations (and patients) was hampered by the model’s long run-times (a common problem with individual patient-level models). Further issues included the many possible comparator and treatment sequence combinations that needed to be assessed. There remained uncertainty about the generalisability of the cost-effectiveness analyses to the targeted patient populations (e.g. two prior lines of treatment and effectiveness assumed to be equal for different lines of treatments). Differences in QALYs between comparators were relatively small in all analyses, except in the moderate population where the ERG considered uncertainty to be larger.

Key Methodological Issues

Comparative evidence from the FINCH 1 and 2 trials was only available for 24-week follow-up, which is very short for a condition that may last 30 years. The real long-term benefit of treatment is likely to be related to its ability to stop X-ray progression. This outcome has not been reported for the FINCH trials.

The best methods for modelling progression from the moderate to severe RA health states are unknown and this warrants further research. The method used by the company and the ERG, i.e. using the HAQ-DI progression to predict the DAS28 progression, resulted in progression estimates that potentially lacked external validity. Further evidence on DAS28 progression in patients starting out with moderate RA would be useful.

RA appraisals and other appraisals with a large number of comparators and potential treatment sequences would benefit from guidance on incorporating these in economic models. Modelling all potential treatment sequences in scenarios is likely not feasible, especially when the number of populations is also large. A distribution of subsequent treatments could be explored instead.

Presentation of fully incremental results in terms of net health benefit was deemed beneficial because of the large number of comparators, small differences in QALYs between intervention and comparators, and because some comparisons had negative incremental QALYs, which would make ICERs difficult to interpret.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidance

On 24 February 2021, NICE recommended filgotinib with methotrexate as an option for treating active RA in adults whose disease has responded inadequately to intensive therapy with two or more cDMARDs, only if disease is moderate or severe (a DAS28 score of 3.2 or more) and the company provides filgotinib according to the commercial arrangement. Filgotinib, with methotrexate, is recommended as an option for treating active RA in adults whose disease has responded inadequately to, or who cannot have other, DMARDs, including at least one biological DMARD, only if disease is severe (a DAS28 score of > 5.1) and they cannot have rituximab and the company provides filgotinib according to the commercial arrangement [1]. Filgotinib, with methotrexate, is recommended as an option for treating active RA in adults whose disease has responded inadequately to rituximab and at least one biological DMARD, only if disease is severe (a DAS28 of > 5.1) and the company provides filgotinib according to the commercial arrangement. Filgotinib can be used as monotherapy when methotrexate is contraindicated or if people cannot tolerate it, when the above conditions are met. Further considerations include the following.

Choose the most appropriate treatment after discussing the advantages and disadvantages of the treatments available with the person having treatment. If more than one treatment is suitable, start treatment with the least expensive drug (taking into account administration costs, dose needed and product price per dose). This may vary from person to person because of differences in how the drugs are taken and treatment schedules.

Continue treatment only if there is a moderate response measured using EULAR criteria at 6 months after starting therapy. If this initial response is not maintained at 6 months, stop treatment.

When using the DAS28, healthcare professionals should take into account any physical, psychological, sensory or learning disabilities, or communication difficulties that could affect the responses to the DAS28, and make any adjustments they consider appropriate.

These recommendations are not intended to affect treatment with filgotinib that was started in the NHS before this guidance was published. People having treatment outside these recommendations may continue without change to the funding arrangements in place for them before this guidance was published, until they and their NHS clinician consider it appropriate to stop.

Consideration of Clinical Effectiveness

The AC concluded that the clinical trials were acceptable for decision making but did not include all relevant comparators for severe disease. Based on the FINCH 1 trial, the NICE AC concluded that filgotinib with methotrexate was more clinically effective than adalimumab with methotrexate, or placebo with methotrexate, in people with moderate to severe disease that has responded inadequately to conventional DMARDs. Based on the FINCH 2 trial, the NICE AC concluded that filgotinib with conventional DMARDs was more clinically effective than placebo with conventional DMARDs in people with moderate to severe disease that has responded inadequately to biological DMARDs.

In addition, the NICE AC concluded that the clinical efficacy of filgotinib monotherapy is uncertain because there are no clinical trial data in the target population.

The NICE AC agreed that for severe disease, there was limited direct trial evidence. Therefore, it accepted the NMA for decision making, bearing in mind their limitations. It agreed that using data from the moderate to severe population was appropriate to inform efficacy estimates for the severe population, because this was aligned with populations in other studies included in the NMA. The NICE AC accepted that, in the absence of data, the efficacy of filgotinib combination therapy may be used as a proxy for the efficacy of filgotinib monotherapy, but noted this approach has limitations and could overestimate the efficacy of filgotinib monotherapy.

Consideration of Cost Effectiveness

With regard to the moderate population, the AC agreed that it was appropriate to use the FINCH methotrexate plus placebo arm to inform the comparator arm. It noted as a limitation that this analysis did not fully reflect what was expected to happen in clinical practice, as response rates in FINCH were considered high for cDMARDs. The AC considered that EULAR response rates should be used where available, instead of mapping ACR responses to EULAR responses.

For both moderate and severe populations, the AC agreed that it was not practical to model all possible treatment sequences. The clinical expert confirmed that the company model included the most relevant comparators and treatment sequences that are used in NHS clinical practice. One exception to that, noted by both clinical and patient experts, was that further advanced therapies would be used instead of BSC in clinical practice. The NICE AC acknowledged this as a limitation but noted that this approach was aligned with previous NICE technology appraisals. It also noted that this is likely to have a limited effect on the cost-effectiveness estimates in severe disease, but could be important to consider for the moderate population in the treatment sequence upon progression to severe disease. The NICE AC concluded that a range of treatment sequences for severe disease following moderate disease are plausible. It also agreed that there was even higher uncertainly about treatment sequences after progression when methotrexate is not suitable and considered this in its decision making.

The AC concluded that although the rates of progression from moderate to severe disease in NHS clinical practice is uncertain, the company approach to model this was reasonable. The AC did note the lack of published data to inform long-term progression rates.

Conclusions

The NICE AC recommended filgotinib in the targeted populations, except for when patients are eligible for rituximab. This recommendation was made as filgotinib provided similar or larger health gains at similar or lower costs compared with its comparators, when all confidential price schemes for filgotinib and comparators had been taken into account. Only in the comparison with rituximab for patients with severe disease whose disease had responded inadequately to one or more biological DMARDs, was filgotinib dominated by rituximab. There was remaining uncertainty about the cost effectiveness of filgotinib in the moderate RA population because of the response rates for the comparator in the trial not reflecting clinical practice. Furthermore, the long-term rate of progression from moderate to severe RA was uncertain and there was uncertainty about the most appropriate treatment sequences for patients who progressed from the moderate to severe population.

Declarations

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme (Grant STA 13/14/25). Please visit the HTA programme website for further project information (https://www.nihr.ac.uk/explore-nihr/funding-programmes/health-technology-assessment.htm). This summary of the ERG report was compiled after NICE issued the FAD. This summary of the ERG report was compiled after NICE issued the FAD. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of NICE or the Department of Health. Any errors are the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of interest

Sabine E. Grimm, Ben Wijnen, Rob Riemsma, Debra Fayter, Nigel Armstrong, Charlotte Ahmadu, Lloyd Brandts, Kate Misso, John R. Kirwan, Jos Kleijnen and Manuela A. Joore have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Availability of data and material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors have commented on the submitted manuscript and have given their approval for the final version to be published. RR, DF, CA and JK critiqued the clinical effectiveness data reported by the company, and KM critiqued the literature searches undertaken by the company. JK provided clinical expert opinion on all aspects of this appraisal. SG, BW, NA, LB and MJ critiqued the mathematical model provided and the cost-effectiveness analyses submitted by the company. SG acts as overall guarantor for the manuscript. This summary has not been externally peer reviewed by Pharmacoeconomics.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Filgotinib for treating moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Technology appraisal guidance [TA676]. London: NICE; 24 Feb 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta676. Accessed 10 Jun 2021

- 2.Gilead. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, multicenter, phase 3 study to assess the efficacy and safety of filgotinib administered for 52 weeks in combination with methotrexate to subjects with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis who have an inadequate response to methotrexate (FINCH 1) clinical study report. Gilead; 2020

- 3.Combe B, Kivitz A, Tanaka Y, Van der Heijde D, Simon JA, Baraf HSB, et al. Filgotinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: a phase III randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(7):848–858. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilead. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase 3 study to assess the efficacy and safety of filgotinib administered for 24 weeks in combination with conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug(s) (csDMARDs) to subjects with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis who have an inadequate response to biologic DMARD(s) Treatment (FINCH 2). Clinical study report. Gilead; 2020

- 5.Genovese MC, Kalunian K, Gottenberg JE, Mozaffarian N, Bartok B, Matzkies F, et al. Effect of filgotinib vs placebo on clinical response in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis refractory to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy: the FINCH 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(4):315–325. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilead Sciences. Filgotinib for treating moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis [ID1632]. Document B: company evidence submission to National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Single technology appraisal (STA) [Word document provided by the company]. Gilead Sciences. 16 Apr 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta676. Accessed 21 Apr 2020: 228.

- 7.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Filgotinib for treating moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis [ID1632]: Clarification response (part 2, V3.0). London: NICE, 29 Jun 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta676. Accessed 30 Jun 2020: 314.

- 8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with DMARDs or after conventional DMARDs only have failed. Technology appraisal guidance [TA375]. London: NICE, 26 JAN 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta375. Accessed 7 Jul 2020.

- 9.Stevenson M, Archer R, Tosh J, Simpson E, Everson-Hock E, Stevens J, et al. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and after the failure of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs only: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(35):1–610. doi: 10.3310/hta20350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Pathway: Rheumatoid arthritis overview. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2020.

- 11.Norton S, Fu B, Scott DL, Deighton C, Symmons DP, Wailoo AJ, et al. Health Assessment Questionnaire disability progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and analysis of two inception cohorts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genovese MC, McKay JD, Nasonov EL, Mysler EF, da Silva NA, Alecock E, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab reduces disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):2968–2980. doi: 10.1002/art.23940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Maxwell L, Macdonald JK, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:8794. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez Alava M, Wailoo A, Wolfe F, Michaud K. The relationship between EQ-5D, HAQ and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(5):944–950. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS). 2020. http://www.mims.co.uk/

- 16.Personal Social Services Research Unit. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2018. https://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/unit-costs-2018/

- 17.Kiely P, Jayakumar K, Norton S, Williams R, Walsh D, Young A, et al. Relation between year 1 DAS28 status and 2 year disease activity, function and employment in Dmard treated RA patients in the early rheumatoid arthritis network (ERAN) Rheumatology. 2009;48(Suppl 1):87. [Google Scholar]