Abstract

Background:

Young adult cancer survivors have significant work-related challenges, including interruptions to education and employment milestones, which may affect work-related goals (WRGs). The study purpose was to explore posttreatment perspectives of WRGs in a sample of young adult hematologic cancer survivors.

Methods:

This qualitative descriptive study used social media to recruit eligible cancer survivors (young adults working or in school at the time of cancer diagnosis). Data were collected through telephone semi-structured interviews and analyzed using directed content analysis, followed by thematic content analysis to identify themes.

Findings:

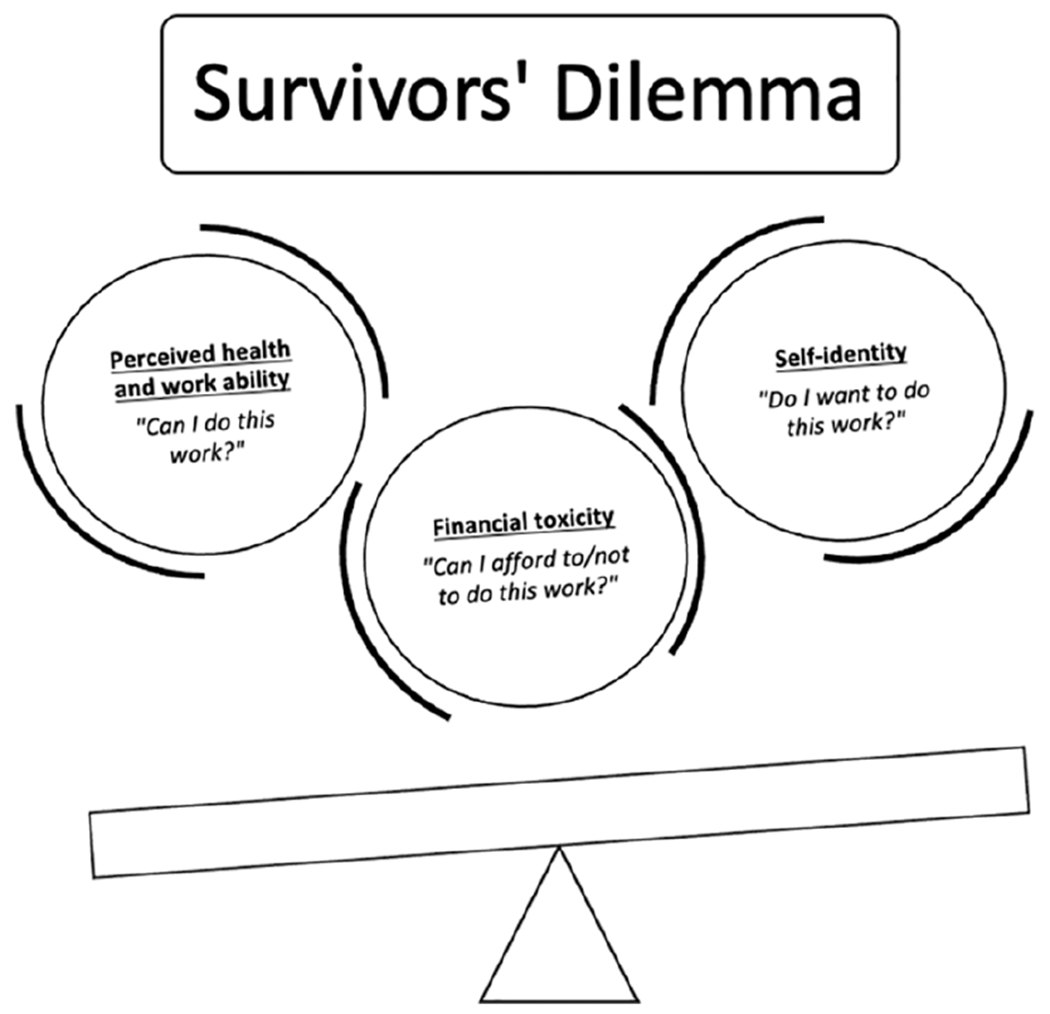

The sample (N = 40) were mostly female (63.5%), White (75%), and diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma (57.5%); most worked in professional (40%) or health care (23%) roles. The overarching theme, “Survivors’ Dilemma,” highlights a changed perspective on work-related fulfillment and financial obligations, capturing survivors’ decision-making process regarding work. Three subthemes illustrated questions that participants contemplated as they examined how their WRGs had changed: (a) Self-identity: Do I want to do this work? (b) Perceived health and work ability: Can I do this work? and (c) Financial toxicity: Can I afford to/not to do this work?

Conclusions/Application to Practice:

Participants experienced a state of dilemma around their WRGs, weighing areas around self-identity, perceived health and work ability, and financial toxicity. Findings suggest occupational health nurses should be aware of challenges surrounding WRGs, including how goals may change following a cancer diagnosis and treatment, and the potential stressors involved in the Survivors’ Dilemma. Occupational health nurses should assess for these issues and refer young survivors to employee and financial assistance programs, as necessary.

Keywords: young workers, cancer, qualitative, work goals, work ability

Background

Young adult (YA) cancer survivors (aged 20–39 years at diagnosis; American Cancer Society [ACS], 2019) constitute a critical component of the working population (Stone et al., 2017). Young adulthood is typically focused on achieving key developmental tasks, psychological fulfillment, and financial security through work (Graetz et al., 2019; Nass et al., 2015; Parsons et al., 2012). Cancer during young adulthood poses a vulnerability to working YAs with detrimental psychosocial impacts on work success, self-esteem, self-confidence, and financial independence from parents (Levin et al., 2019). Work and its related components (e.g., compensation and the physical and social environments in the workplace), the role of the worker (e.g., job-specific duties), and the individual worker’s characteristics ultimately affect worker health and well-being (Moore & Moore, 2014).

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) identifies a subset of YA workers (i.e., those up to age 24) as the “emerging workforce” and thus a vulnerable group within occupational health (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020; Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 2020; Okun et al., 2016). Emerging workers face unique challenges in the workplace for developmental and environmental reasons (Okun et al., 2016). Developmentally, similar risk factors are seen in workers in their mid-to-late 20s (M. Miller et al., 2007). YAs (20–39 years) are also described as a vulnerable cancer population (Bleyer et al., 2017; Graetz et al., 2019; Munoz et al., 2016); they confront health disparities, including access to care and diagnosis at more advanced disease stage, thus poorer prognosis (Liu et al., 2018; National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2018). The impact of cancer on work, including employment and education needed to achieve work-related goals (WRGs), is a critical determinant of health, quality of life, and financial well-being (Barr et al., 2016; Dahl et al., 2019), particularly for YAs given their many work years ahead (Chiyon Yi et al., 2019; Parsons et al., 2012). A clearer understanding of WRGs following completion of active treatment for cancer is needed to address occupational health issues in the YA workforce.

Nearly 84,000 YAs are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States (Miller et al., 2020). The rising number of YA survivors has been attributed to higher overall incidence of cancer in this age group (i.e., a 3% increase in the last decade; Miller, et al., 2020), rising incidence of colorectal cancer and other malignancies that had been more typical in older adults, and therapeutic advances that have improved 5-year survival rates (NCI, 2018).

Hematologic malignancies, including leukemia and lymphoma (ACS, 2019), are among the most commonly occurring types of cancer in YAs; more than 18,000 YAs are diagnosed each year (ACS, 2019; NCI, 2018). Chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment and causes side effects (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, low blood counts) that can compromise ability to work during treatment. Moreover, when compared with YA survivors of other cancers, YA hematologic cancer survivors were less likely to return to work (Leuteritz et al., 2020; Parsons et al., 2012). Therefore, these YA survivors may experience higher rates of psychological distress, poorer quality of life, and poorer financial well-being due to work disruptions compared with older cancer populations (Hall et al., 2015).

Following completion of cancer therapy, YAs describe physical, practical, and psychosocial concerns related to work (Jones et al., 2020; Lea et al., 2020). Cancer-related physical and psychosocial changes can adversely affect work productivity and work ability, with decreased engagement with school and work activities (Sisk et al., 2020). Work status has been shown to be a driver of cancer-related financial burden (demands on income) and financial distress (worry about finances; Leuteritz et al., 2020; Sisk et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2019). Although work has been shown to enhance overall quality of life in YAs (Stone et al., 2017), work-related stressors and uncertainty about finances can also lead to poorer mental and physical health, and lower quality of life (Hall et al., 2012; Hammond, 2016).

Although YA survivors are motivated to return to work (Tan et al., 2020), their diagnosis may necessitate changes in work and education, including influencing choice of occupation (Drake & Urquhart, 2019; Parsons et al., 2012). WRGs as described by Wells et al. (2013) signifies how individuals understand why they are working and what they hope to achieve in their work, including both tangible (e.g., income, health insurance) and intangible (e.g., meaning and purpose) benefits. WRGs can change over time and may relate to financial issues, self-identity, and relationships with work colleagues (Wells et al., 2013). Understanding perceptions of WRGs within the context of YA cancer survivorship will facilitate exploring the influence of work-related factors on quality of life. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the WRGs in a sample of YAs who completed therapy for a hematologic cancer.

Both the Social Ecological Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and the Life Course Perspective (Elder & Rockwell, 1979) informed the study. Taken together, these perspectives explain how significant life events and factors within and across multiple ecological levels operate to influence quality of life over the life course, for example, prior and subsequent to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer during young adulthood. Ecological levels include individual (e.g., personal characteristics), microsystem (e.g., factors related to work and colleagues), and mesosystem (e.g., interactions between microsystems).

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional qualitative descriptive design (Sandelowski, 2000). The data were collected as part of a NIOSH Educational Research Center–funded mixed-methods project examining the influence of individual and work-related factors on quality of life among 40 YAs who had successfully completed treatment for hematologic cancer. We obtained study approval through the New York University Institutional Review Board (IRB; No. 2020-4281).

Participants were eligible for the study if they were (a) aged 20 to 39 years at diagnosis with leukemia or lymphoma; (b) within 1 to 5 years since diagnosis; (c) working or in school to any extent at the time of diagnosis; (d) received their treatment in the United States; (e) successfully completed active treatment; and (f) were able to read, understand, and speak English. The eligible age YA range followed the oncology literature (ACS, 2019; NCI, 2018) and not that of the “emerging workforce” classified by NIOSH. Exclusion criteria included currently receiving cancer-directed treatment and self-reported life expectancy of less than 6 months.

Recruitment and Enrollment

We recruited participants through social media platforms (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) and YA cancer organizations using purposive and snowball sampling methods (Creswell, 2014; T. P. Johnson, 2014). IRB-approved study information was posted via these platforms and shared through organization listservs. An incentive (i.e., US$50 gift card) was offered to participants upon completion of the study requirements that included a semi-structured interview.

We employed a maximum variation sampling strategy to select eligible participants that reflected a heterogenous sample on characteristics important to the study (i.e., sex, gender, race/ethnicity, age at diagnosis, type of work). Based on prior work of the research team (Dickson et al., 2011; Riegel et al., 2018) and the literature on YAs with cancer (Hauken et al., 2014; Munoz et al., 2016), we determined that interviews with 40 participants would provide sufficient data to achieve saturation, the point no new themes in the data are being identified.

The data were collected by the primary author (L.V.G) between April 6, 2020, and July 31, 2020. Participants provided electronic informed consent through DocuSign, Inc., a secure online software for administering and capturing consent.

Data Collection

We used Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) to collect sociodemographic (e.g., age at diagnosis, sex and gender, race/ethnicity, health insurance type, type of work, income) and clinical characteristics (e.g., hematologic cancer type, year of diagnosis, treatment history). This survey was investigator-developed and included questions based on the literature (including NCI and Biomedical Research Informatics Computing System National Institute of Nursing Research Templates) and with the consultation of content experts. Response options included single and multiple-choice survey items and short-answer free response.

Qualitative data were collected through individual 1:1 semi-structured interviews. The first author (L.V.G,) conducted all interviews via the university Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) subdomain of Zoom audio only, which is IRB approved for research purposes.

Interview data

We developed the interview guide based on the two perspectives informing the study (i.e., Social Ecological Model and Life Course Perspective). The guide is available in Supplementary Material and included open-ended questions, each of which was followed by more directed questions or probes (Assarroudi et al., 2018; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Informed by the Life Course perspective (Elder & Rockwell, 1979), we structured the interview such that participants were asked to describe their employment and/or education at the time of their diagnosis and then in the present day. For example, “What were your WRGs before you were diagnosed with cancer?” The Social Ecological Model informed our questions around microsystem-level factors pertaining to work and individual-level factors informing quality of life. For example, “What concerns did you have related to work and school during the time of your cancer diagnosis?”

The primary author interviewed each participant once. Throughout the study, we modified the interview guide to account for recent events in the social environment (i.e., we recognized allowing participants to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic was important).

Data Management and Analysis

Following each interview, the primary author electronically submitted the interview audio recording to Landmark, Inc. for transcription. Interviews were transcribed verbatim, imported into MAXQDA v.9, where they were checked for accuracy (Assarroudi et al., 2018; Thomas & Magilvy, 2011). Any identifying information was redacted from the transcription. We used MAXQDA to facilitate data management and analysis. Qualitative analysis was completed by the first author (L.V.G.), trained in qualitative data analysis and supervised by the senior author (V.V.D.), an expert in qualitative analysis and occupational health nursing. Methodological rigor (J. L. Johnson et al., 2020; Thomas & Magilvy, 2011) was ensured by peer debriefing, and review by research team members with expertise in oncology nursing (J.M.), including research and care of YAs (S.J.S.). To ensure consistency, team members met regularly to clarify and refine codes and discuss emerging themes.

We analyzed qualitative data using directed content analysis, a deductive analytic method (Creswell, 2012; Mayring, 2000; Patton, 2001), followed by thematic content analysis to further organize categories and identify themes (Hickey & Kipping, 1996; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Each interview transcript was coded, deductively generating codes from the Social Ecological Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), including codes for individual-level factors (e.g., work ability and self-identity), microsystem-level factors (e.g., work, school), and mesosystem-level factors (e.g., WRGs). Coding was an iterative process in that the codebook was continuously revised with additions of new codes that emerged during the analysis, and examination of the previously coded data for evidence of the new codes. Data saturation was achieved by analysis of the 40th interview, as evidenced by no new codes applied during analysis (Creswell, 2012; Saunders et al., 2018).

In the process of inductive abstraction, we grouped and categorized main preliminary codes to generic categories (Mayring, 2000). We used the constant comparison technique to establish links between the documented main categories and the generic categories that developed (Assarroudi et al., 2018; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2005). Codes and categories were then collated into potential themes and generated a thematic map.

Findings

Participant Demographics

Forty participants from 23 states took part in this study (median age = 28 [SD = 5.26]; range = 20–38 years). Although the age range of YA cancer survivors is up to 39 years, we did not have any participants who were aged 39 at the time of diagnosis. The social media platform Facebook generated the most participants (80%). The majority of participants were female (63.5%) and White, non-Hispanic (75%). Participants were all postactive treatment; the majority diagnosed with Hodgkin (57.5%) or non-Hodgkin (25%) lymphoma, which is consistent with the prevalence of these hematologic cancers in the YA population (ACS, 2020; K. D. Miller et al., 2020). Most prevalent type of work at the time of study enrollment was professional, technical (40%), health care–related (22.5%), and education or research-related (17.5%) work. The majority of participants (57.5%) had at least a bachelor’s degree, and 80% had private health insurance. Table 1 displays a full description of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Young Adult Cancer Survivors (N = 40)

| Sample characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |

| 20–29 years | 26 (65) |

| 30–39 years | 14 (35) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 26 (65) |

| Male | 14 (35) |

| Race | |

| White | 29 (72.5) |

| Black | 4 (10) |

| Asian | 2 (5) |

| Mixed race | 5 (12.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 35 (87.5) |

| Hispanic | 5 (12.5) |

| Type of work | |

| Professional, technical | 16 (40) |

| Health care | 9 (22.5) |

| Education or research | 7 (17.5) |

| Service worker | 5 (12.5) |

| Student | 2 (5) |

| Currently not in workforce | 1 (2.5) |

| Level of education | |

| High school diploma | 3 (7.5) |

| Some college | 9 (22.5) |

| Associate’s degree | 4 (10) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 10 (25) |

| Master’s degree | 9 (22.5) |

| Professional or doctoral degree | 4 (10) |

| Don’t know | 1 (2.5) |

| Insurance type | |

| Medicaid/SSI | 5 (12.5) |

| Medicare | 2 (5) |

| Military (VA) | 1 (2.5) |

| Private insurance | 32 (80) |

| Hematologic cancer | |

| Lymphoma | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 23 (57.5) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 10 (25) |

| Leukemia | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 2 (5) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 5 (12.5) |

Note. Examples of professional type of work included accounting, legal, marketing, and journalism. Examples of health care type of work included all levels of nursing practice, mental health counseling, and emergency room technician. SSI = Supplemental Security Income; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Overarching Theme: Survivors’ Dilemma

The overarching theme that emerged from the data was Survivors’ Dilemma (Figure 1). The research team created the term Survivors’ Dilemma to encompass the themes that we found in this study regarding participant’s perceptions of WRGs. Survivors’ Dilemma highlights a changed perspective on work-related fulfillment and financial obligations and captures the participants’ descriptions of decision-making regarding their work/school following diagnosis and treatment. Participants described both somatic and affective symptoms that drove perceptions of not only their ability to meet current work and/or school demands (i.e., work ability) but also their overall, more future-oriented WRGs. Symptoms were further connected to their descriptions of self-identity within the context of work and/or education and perceived psychosocial needs.

Figure 1.

The survivors’ dilemma.

Note. The scale represents the “weighing” of options for YA cancer survivors in this study. For each participant, one of the concepts (identified as subthemes in this analysis) would outweigh the others—but we do not know which concept is the heaviest on the scale (i.e., is of the most importance/the biggest factor in their decision-making). YA = young adult.

Participants described a heightened desire to seek fulfillment and meaning in work, alongside significant cancer-related financial burden. The survivor’s dilemma was a conflict that arose between finding meaning in work and pragmatics such as compensation and benefits. Many participants expressed a changed perspective on life, an awareness of self-identity, and described “higher expectations” following completion of their cancer therapy, having “survived cancer,” and “getting another chance” in life. As one participant, who worked in education at the time of diagnosis, explained their dilemma,

… in order to take care of myself, I had to quit this job that had been my end goal … I had to go back to the job that I had worked all through school … [with diagnosis and treatment] it’s taxing for me to do the job that I chose as my career, and then now I can’t even afford to do that job … despite everything I’ve done in my education to get to this point … I’m literally thinking to myself, “What have I been working my whole life for?”

Another participant who worked in health care further described,

It’s a mental thing … your mind thinks that you need to go and do all these things— I survived cancer, I need to go and live … but then you get done with [treatment] and you’re like … but I have to save money, because what if something happens … Yes, you can go do things; however, it almost comes with a catch.

Inherent in survivors’ dilemma was three main subthemes (Figure 1). These subthemes illustrated the questions that participants contemplated as they examined how their WRGs had changed or remained the same: (a) Self-identity: Do I want to do this work? (b) Perceived health and work ability: Can I do this work? and (c) Financial toxicity: Can I afford to/not to do this work?

Self-identity: Do I want to do this work?

For many participants, work and/or education provided a sense of normalcy to their lives following their cancer diagnosis and while undergoing active treatment. The benefits of work were seen in its fulfillment and purpose for this participant who stated,

I felt so crazed by the end of treatment to be back at work and to be useful … I didn’t realize how important being needed at work was and having a job that’s your position where people count on you.

Accepting that their perspective on life had changed (e.g., “Is it emotionally, spiritually fulfilling? No, but this is this thing that I have to navigate now”), many participants emphasized wanting to find meaning in their work, which they clarified as their own self-awareness of their identity. As one participant described,

I’ve become more aware of my time and how I spend it … whatever type of work I do, it needs to be meaningful, needs to be purposeful. It needs to be something that I truly want to do. If not, I’m not going to do it.

Another participant who worked in a professional role described their “enhanced” self-identity in work:

I think about wanting to live life to the fullest and take advantage of the opportunities … being intentional about the kind of things that I do and not getting caught in the rat race of going to work, going home … just because I feel like I have to. I wanna do work because I want to. I do think that is different, well maybe enhanced, having gone through cancer—really, really, really meaning it and wanting to do that.

For many participants, the relationship between work and their cancer experience was bidirectional. Participants explained how they would use skills that they developed through their cancer experience (e.g., empathy, understanding of having a life-threatening illness) in their work. For example, a participant in health care said,

… I knew that with all this cancer experience, I would be able to relate to [my patients] on a deeper level than I had been. I was excited to go back and meet new people and use this … now I feel like I’m really able to empathize with them … I really understand a little bit deeper.

Conversely, participants also described how their work affected their cancer experience, such as their ability to understand medical terminology, the implications of the diagnosis presented to them, and self-advocate (e.g., “It’s helped me advocate for myself. I don’t think I would be as comfortable with the material if I had not been a med. student”).

Perceived health and work ability: Can I do this work?

Another subtheme of the Survivors’ Dilemma is perceived health and work ability. Participants experienced both physical (e.g., cognitive problems, fatigue, and neuropathy) and affective (e.g., anxiety and depressive symptoms, fear of cancer recurrence) symptoms subsequent to their diagnosis and treatment that linked to their work ability. How they experienced certain symptoms led many participants to question whether they could continue in their current employment and job type. As a participant in health care described, “I have trouble following through, I have trouble concentrating, I’m more anxious and depressed. Those things make it harder for my type of job.” A participant, who described their job as mentally demanding, stated, “I did realize significant impairment in my mental acuity. It felt like I was thinking through or processing my thoughts very, very slowly … It was just foreign to me because I’d always been whip smart.” The uncertainty of how long symptoms would persist led to reflection about work ability across work types. One participant in education pondered, “… am I gonna be physically comfortable teaching for a full year? What [can] I actually do where I’m not putting stress on my body anymore? I don’t have these answers yet.” A participant, who described an active job in a hospital setting, stated,

… [I’m] trying to get to the point, so I know when I go back to work I’ll physically be able to handle it. Because there is a lot of standing, a lot of walking. You never know how busy your day is gonna be.

Furthermore, for some participants, not being able to work throughout treatment had heightened affective symptoms. One participant in the service role described, “Did I fall into depression? Absolutely, because I ended up having to lose work … I’m not used to being without work that long.”

Financial toxicity: Can I afford to/not to do this work?

The third subtheme was financial toxicity (adverse effects of the cancer experience on personal finances; Zafar & Abernethy, 2013), which contributed to the dilemma participants faced regarding having to choose between pursuing somewhat conflicting WRGs. Participants described the financial burden of cancer and its treatment, the subsequent financial distress, and the consequences of financial toxicity. These consequences of financial toxicity included financial coping behaviors (e.g., accumulating credit card debt, selling assets with monetary value), poorer financial well-being, poorer mental and physical health, and poorer quality of life. A participant who worked in education said, “… to be burdened with so much debt is a very challenging place for me to be mentally.” Throughout the interview, this participant described the financial distress they experienced while trying to cope with cancer-related financial burden given their salary.

Across genders, participants described their financial coping behaviors when experiencing severe financial burden and the associated financial distress. A participant, who described being in graduate school and also working at the time of diagnosis, stated,

Since I didn’t have anything saved and I wasn’t really planning for this—I took out like four or five credit cards and just maxed them all because I was just overwhelmed. I didn’t really know financial stuff yet. I didn’t have anyone to lean on.

And another service worker described coping similarly: “I ended up getting into some credit card debt. I sold a lot of things that I had bought for myself over the years to try to play catch up on bills that I had monthly.” These examples capture financial toxicity within the life course and period of young adulthood.

Given the adverse effects of cancer on their finances, some participants reported feeling stuck in a type of work that no longer linked to their WRGs; however, due to the financial benefits of the job, they had to stay with that work. For example, “I feel like I need to go do these [new WRGs], but there’s that whole financial portion.” In these cases, the employment in question was tied to health insurance coverage. Participants described significant worry about losing their health insurance coverage and other employment benefits such as paid time off. One participant said, “I’m in constant distress … what happens if I lose my job? … I need my benefits, and that’s one reason I stick with my current position.” Participants also discussed not qualifying for certain employment benefits, such as short- and long-term disability, given employer requirements mandating a set amount of days of employment before activation of health benefits.

Even those participants who reported a “safety net” (e.g., health insurance through their partner’s employer, or friends or family who provided financial assistance) described financial toxicity. One participant in a professional role stated, “If I had a different job or didn’t have good health insurance, it would have been so dramatically, life-alteringly different.” This participant described being held back by the risk of financial toxicity’s consequences if they switched jobs to something that was more aligned to their changed WRGs. In this case, actually pursuing their WRGs could result in “selling [their] house and filing for bankruptcy and living in [their] mom’s basement.”

Discussion

The primary finding in this study suggests that participants experienced a state of dilemma around their WRGs, factoring in areas around self-identity, perceived health and work ability, and financial toxicity (Figure 1). Consistent with existing research on YAs with cancer, participants in our study described a changed perspective on life (Hauken et al., 2019), both positive and negative changed relationships with work (Bashore & Breyer, 2017; Vetsch et al., 2017), and the impact of treatment side effects on the ability to work (Drake & Urquhart, 2019). Work was regarded as something that provided a sense of normalcy and identity, which is similar to findings from a systematic review on YA cancer survivors and work (Stone et al., 2017). For the YAs in our study, a cancer diagnosis and treatment prompted them to reexamine their decision-making related to work, which resulted in the Survivors’ Dilemma.

Consistent with prior studies on YA survivors of childhood cancers (Kirchhoff et al., 2013, 2018), participants experienced feelings of “being stuck” and/or “torn” when describing posttreatment WRGs, within the context of changes to the goals themselves or because of physical, mental, and/or financial reasons. Furthermore, the concept of job lock, discussed in prior work (Kent et al., 2020; Kirchhoff et al., 2018), was also captured by participants in this study when discussing financial toxicity influencing WRGs.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to explore posttreatment perspectives of WRGs of YAs who had successfully completed treatment for a hematologic cancer. In-depth interviews revealed a multifactorial process of decision-making regarding survivors’ current and future work. Our findings also fill an important gap in the literature on the impact of cancer on the career development during young adulthood (Stone et al., 2017).

Our major theme, Survivors’ Dilemma, aligns with the “goal conflict” that emerged in Vetsch et al.’s (2017) multimethod study of WRG changes in a sample of 42 adolescent and YA cancer survivors. The majority of those participants described their WRGs as being of equal or greater importance than prior to their cancer diagnosis. The authors also described physical, practice, and psychological barriers to work and education reintegration, for example, lingering treatment-related symptoms (e.g., fatigue and problems with cognition). Within the Survivors’ Dilemma theme that emerged in our study, Vetsch et al.’s (2017) physical barriers may relate to both perceived health and work ability, and financial toxicity subthemes, and psychological barriers to perceived health and financial distress.

Furthermore, Strauser et al.’s (2015) review of the literature and framework on career development in YA cancer survivors supports the results of this study that cancer-related factors, including physical and affective symptoms, relate to, and impact, WRGs. Strauser et al. (2015) described multiple interacting domains, including career development, where individual self-awareness results in an understanding of self-identity and what work would be physically, cognitively, and emotionally beneficial to pursue. Our study’s subthemes of self-identity and perceived health and work ability are consistent with this domain found in Strauser et al.’s work. Work ability changes as a new balance between job demands and one’s physical and mental health are established and may influence career development (Ilmarinen, 2006; Stone et al., 2017).

Finally, in line with prior studies, participants in our study expected to reach milestones in their work goals, and a cancer diagnosis disrupted achieving these goals (Bellizzi et al., 2012; Docherty et al., 2015; Parsons et al., 2012; Warner, 2016). In our study, the YA participants expressed concerns regarding the difficulty of continuing to pursue their work while also describing how they would pursue current and future WRGs. This finding is consistent with Bellizzi et al.’s (2012) multicenter, cross-sectional study of 523 newly diagnosed (<14 months since date of diagnosis) adolescents and YAs that found that a cancer diagnosis as a YA had adversely affected current work, but benefited future work-related plans and goal setting.

Several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, participants self-reported their hematologic cancer diagnosis, and we were not able to verify diagnosis via medical record. While we included participants who were less than 5 years from diagnosis, self-report of diagnosis may have introduced recall bias. Second, this study collected only one type of work status at baseline. Our study recruited YAs who were actively working and/or in school at the time of their diagnosis. Findings related to WRGs may be different for participants who were unemployed, or working part-time, at diagnosis and/or data collection. Others have reported that YAs who were unemployed before their diagnosis were more likely continue to remain unemployed (Parsons et al., 2014).

Third, although our sampling plan included the use of maximum variation sampling, we obtained a sample that was mostly White and female. This limitation is frequently seen in YA cancer research, where most volunteers are White females (Kent et al., 2012; Kirchhoff et al., 2014). However, we did have variation on other attributes important to this phenomenon, including age at diagnosis and type of work.

Finally, these interviews were conducted amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Although participants were able to discuss current impact of COVID-19, it was not the primary aim of the study. We were not able to discern whether narratives related to WRGs were affected solely by cancer experiences or also combined with the uncertainty of COVID to one’s health and work status.

Implications for Occupational Health Nursing Practice

According to the NIOSH National Occupational Research Agenda cross-sector recommendation for research that promotes healthy work design and well-being (CDC, 2018), advancing the health, safety, and well-being of YA workers with a history of cancer is a priority. In young workers overall (i.e., up to 24 years), there are multiple risk factors, including limited prior work experience and lack of safety training, that increase the likelihood of poor workplace health and safety (OSHA, 2020). This may extend to older young workers with chronic illness, that is YAs with cancer; poorer workplace health may be heightened with disease symptoms and treatment side effects, and more reluctance to acknowledge work difficulties, further affecting their perceived health and work ability (International Labour Organization, 2018; Rabin, 2020).

YAs with cancer face unique challenges with characterizing their WRGs, and occupational health nurses should be aware of these challenges. The concept of WRGs is multilevel (Fenn et al., 2014; Stone et al., 2017), and this characteristic is evident in our findings. Several categories of WRGs captured in the Survivors’ Dilemma are at the individual level: the components of financial toxicity (financial burden, financial distress, financial coping behaviors, financial well-being, quality of life), work ability, and self-identity. Thus, the challenges surrounding WRGs faced by YAs with decreased financial security may influence quality of life. Additional research is needed to identify what factors mediate this relationship between work and quality of life. This requires using advanced methods to examine multilevel individual and microsystem effects and additional work on the significance of financial health of participants in these instances driving WRGs. Future work should also aim to explore the role of occupational and financial counselors in the care of YAs with cancer (Dax et al., 2020; Leuteritz et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020).

Furthermore, YAs with cancer who want to continue to, or return to, work after a prolonged medical disability leave may face additional obstacles, including the need for accommodations (Drake & Urquhart, 2019; Stone et al., 2019). Facilitating return to work by identifying facilitators and barriers to both disability and workplace accommodations and benefits was beyond the scope of this study, but is an area that requires additional research at the microsystem level, as it may promote job maintenance and transition back to the workforce after treatment (Meernik et al., 2020).

In Survivors’ Dilemma, multiple tensions arise in decision-making about work and WRGs. YA cancer survivors continuously weigh their changed self-identity with the physical and mental demands of their work, and the financial impact of both forgoing current and pursuing future work. Findings of this study reveal that occupational health nurses should be made aware that patients who are YA cancer survivors may have changes in their WRGs and face additional stress as they ponder these changes. The role of occupational health nurses in facilitating work engagement for YA cancer survivors may improve stress related to the WRGs process and ultimately improve quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Applying Research to Occupational Health Practice.

Advancing the health, safety, and well-being of working young adult cancer survivors is a priority under NIOSH’s National Occupational Research Agenda cross-sector recommendations. Perspectives of work-related goals (WRG’s) in a sample of 40 working young adult hematologic cancer survivors was explored in this qualitative, descriptive study. Participants describe a theme of Survivors Dilemma, which captures decision-making related to work goals. Occupational health nurses need to be aware of the three subthemes presenting in this dilemma: self-identity, perceived health and work ability, and financial toxicity. Occupational health nurses should also be cognizant that YAs diagnosed with cancer may experience changes in their WRGs and face additional stress as they ponder these changes. Occupational health nurses should understand their role in supporting this unique group of cancer survivors through assessment, increasing referrals to employee and financial assistance programs, and assisting with identifying workplace accommodations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the young adult cancer survivors who participated in this study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: L.V.G is a trainee at the NYU Meyers T42 Pre-Doctoral Occupational and Environmental Health Nursing (OEHN) Training Grant (T42-OH-008422; Dickson PI) and recipient of an ERC Pilot Project Grant.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Lauren Victoria Ghazal, PhD, FNP-BC, at the time of this study, was a PhD student and NIOSH T42 pre-doctoral fellow at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing. Building on her economics background and clinical and personal experiences, her research focuses on factors influencing quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.

John Merriman, PhD, RN, AOCNS is an assistant professor at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing. His program of research includes assessment of stress management interventions to improve cognitive function among women with breast cancer.

Sheila Judge Santacroce, PhD, RN, CPNP, FAANP is the Beerstecher-Blackwell Distinguished Associate Professor and PI/Director of the NINR-funded T32 in Interventions for Preventing and Managing Chronic Illness at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Nursing. Her research focuses on improving medical and quality of life outcomes for children, adolescents and young adults with serious chronic illness and their family members.

Victoria Vaughan Dickson, PhD, RN, FAHA, FHFSA, FAAN is the site program director of the NIOSH-funded doctoral training program in occupational and environmental health nursing and an associate professor in the NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing. She is recognized as an international expert in qualitative research techniques and mixed methods research.

Footnotes

This manuscript is based on material presented virtually at the Eastern Nursing Research Society Conference in April 2021.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- American Cancer Society. (2019). Cancer in young adults. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-in-young-adults.html

- American Cancer Society. (2020). Cancer facts & figures 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf

- Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, & Vaismoradi M (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. Journal of Research in Nursing, 23(1), 42–55. 10.1177/1744987117741667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, & Bleyer WA (2016). Cancer in adolescents and young adults: A narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(5), 495–501. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashore L, & Breyer E (2017). Educational and career goal attainments in young adult childhood cancer survivors. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 22(2), Article e12180. 10.1111/jspn.12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, Keegan THM, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, Deapen D, Shnorhavorian M, Tompkins BJ, & Simon M, & Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) Study Collaborative Group. (2012). Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer, 118(20), 5155–5162. 10.1002/cncr.27512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyer A, Ferrari A, Whelan J, & Barr RD (2017). Global assessment of cancer incidence and survival in adolescents and young adults. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 64(9), Article e26497. 10.1002/pbc.26497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design (unknown edition). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA). https://www.cdc.gov/nora/default.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH): Young worker safety and health. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/youth/default.html

- Chiyon Yi J, Syrjala K, Ganz PA, Nekhlyudov L, & Shah S (2019). Overview of cancer survivorship in adolescent and young adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cancer-survivorship-in-adolescent-and-young-adults [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl AA, Fosså SD, Lie HC, Loge JH, Reinertsen KV, Ruud E, & Kiserud CE (2019). Employment status and work ability in long-term young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 8(3), 304–311. 10.1089/jayao.2018.0109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dax V, Edwards N, Doidge O, Morkunas B, Thompson K, & Lewin J (2020). Evaluation of an educational and vocational service for adolescent and young adults with cancer: A retrospective review. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 10.1089/jayao.2020.0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson VV, Lee CS, & Riegel B (2011). How do cognitive function and knowledge affect heart failure self-care? Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 5(2), 167–189. 10.1177/1558689811402355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty SL, Kayle M, Maslow GR, & Santacroce SJ (2015). The adolescent and young adult with cancer: A developmental life course perspective. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 31(3), 186–196. 10.1016/j.soncn.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake EK, & Urquhart R (2019). “Figure out what it is you love to do and live the life you love”: The experiences of young adults returning to work after primary cancer treatment. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 8(3), 368–372. 10.1089/jayao.2018.0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, & Rockwell RC (1979). The life-course and human development: An ecological perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 2, 1–21. 10.1177/016502547900200101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, DiGiovanna MP, Pusztai L, Sanft T, Hofstatter EW, Killelea BK, Knobf MT, Lannin DR, Abu-Khalaf M, Horowitz NR, & Chagpar AB (2014). Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10(5), 332–339. 10.1200/JOP.2013.001322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graetz D, Fasciano K, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Block SD, & Mack JW (2019). Things that matter: Adolescent and young adult patients’ priorities during cancer care. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 66(9), Article e27883. 10.1002/pbc.27883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AE, Boyes AW, Bowman J, Walsh RA, James EL, & Girgis A (2012). Young adult cancer survivors’ psychosocial well-being: A cross-sectional study assessing quality of life, unmet needs, and health behaviors. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(6), 1333–1341. 10.1007/s00520-011-1221-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW, Lynagh MC, Tzelepis F, & D’Este C (2015). What do haematological cancer survivors want help with? A cross-sectional investigation of unmet supportive care needs. BMC Research Notes, 8, Article 221. 10.1186/s13104-015-1188-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond C (2016). Against a singular message of distinctness: Challenging dominant representations of adolescents and young adults in oncology. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 6(1), 45–49. 10.1089/jayao.2016.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauken MA, Grue M, & Dyregrov A (2019). “I’s been a life-changing experience!” A qualitative study of young adult cancer survivors’ experiences of the coexistence of negative and positive outcomes after cancer treatment. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 60(6), 577–584. 10.1111/sjop.12572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauken MA, Holsen I, Fismen E, & Larsen TMB (2014). Participating in life again: A mixed-method study on a goal-orientated rehabilitation program for young adult cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 37(4), E48–E59. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31829a9add [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey G, & Kipping C (1996). A multi-stage approach to the coding of data from open-ended questions. Nurse Researcher, 4(1), 81–91. 10.7748/nr.4.1.81.s9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilmarinen J (2006). The Work Ability Index (WAI). Occupational Medicine, 57(2), 160–160. 10.1093/occmed/kqm008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. (2018). Improving the safety and health of young workers. https://www.ilo.org/safework/events/safeday/WCMS_625223/lang-en/index.htm

- Johnson JL, Adkins D, & Chauvin S (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 7120. 10.5688/ajpe7120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP (2014). Snowball sampling: Introduction. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics reference online. American Cancer Society. 10.1002/9781118445112.stat05720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Fitch M, Bongard J, Maganti M, ’Gupta AD, Agostino N, & Korenblum C (2020). The needs and experiences of post-treatment adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(5), Article 1444. 10.3390/jcm9051444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, de Moor JS, Zhao J, Ekwueme DU, Han X, & Yabroff KR (2020). Staying at one’s job to maintain employer-based health insurance among cancer survivors and their spouses/partners. JAMA Oncology, 6(6), 929–932. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Parry C, Montoya M, Sender L, Morris R, & Anton-Culver H (2012). “You’re too young for this”: Adolescent and young adults’ perspectives on cancer survivorship. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 30(2), 260–279. 10.1080/07347332.2011.644396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff AC, Kuhlthau K, Pajolek H, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, & Park ER (2013). Employer-sponsored health insurance coverage limitations: Results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(2), 377–383. 10.1007/s00520-012-1523-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff AC, Nipp R, Warner EL, Kuhlthau K, Leisenring WM, Donelan K, Rabin J, Perez GK, Oeffinger KC, Nathan PC, Robison LL, Armstrong GT, & Park ER (2018). “Job lock” among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA Oncology, 4(5), 707–711. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff AC, Spraker-Perlman HL, McFadden M, Warner EL, Oeffinger KC, Wright J, & Kinney AY (2014). Sociodemographic disparities in quality of life for survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 3(2), 66–74. 10.1089/jayao.2013.0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea S, Martins A, Fern LA, Bassett M, Cable M, Doig G, Morgan S, Soanes L, Whelan M, & Taylor RM (2020). The support and information needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer when active treatment ends. BMC Cancer, 20(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s12885-020-07197-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuteritz K, Friedrich M, Sender A, Richter D, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A, Sauter S, & Geue K (2020). Return to work and employment situation of young adult cancer survivors: Results from the adolescent and young adult-Leipzig study. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 10.1089/jayao.2020.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin NJ, Zebrack B, & Cole SW (2019). Psychosocial issues for adolescent and young adult cancer patients in a global context: A forward-looking approach. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 66(8), Article e27789. 10.1002/pbc.27789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Moke DJ, Tsai K-Y, Hwang A, Freyer DR, Hamilton AS, Zhang J, Cockburn M, & Deapen D (2018). A reappraisal of sex-specific cancer survival trends among adolescents and young adults in the United States. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 10.1093/jnci/djy140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meernik C, Kirchhoff AC, Anderson C, Edwards TP, Deal AM, Baggett CD, Kushi LH, Chao CR, & Nichols HB (2020). Material and psychological financial hardship related to employment disruption among female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 10.1002/cncr.33190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KD, Fidler-Benaoudia M, Keegan TH, Hipp HS, Jemal A, & Siegel RL (2020). Cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70, 443–459. 10.3322/caac.21637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Handelman E, & Lewis C (2007). Protecting young workers coordinated strategies help to raise safety awareness. Professional Safety, 52. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254508919_Protecting_Young_Workers_Coordinated_Strategies_Help_to_Raise_Safety_Awareness [Google Scholar]

- Moore P, & Moore R (2014). Fundamentals of occupational and environmental health nursing AAOHN core curriculum (4th ed.). https://www.amazon.com/Fundamentals-Occupational-Environmental-Nursing-Curriculum/dp/0984886125

- Munoz AR, Kaiser K, Yanez B, Victorson D, Garcia SF, Snyder MA, & Salsman JM (2016). Cancer experiences and health-related quality of life among racial and ethnic minority survivors of young adult cancer: A mixed methods study. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(12), 4861–4870. 10.1007/s00520-016-3340-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Fasciano K, Ganz PA, Hayes-Lattin B, Hudson MM, Nevidjon B, Oeffinger KC, Rechis R, Richardson LC, Seibel NL, & Smith AW (2015). Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. The Oncologist, 20(2), 186–195. 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2018). Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with cancer. https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (2020). Young workers. https://www.osha.gov/youngworkers/index.html

- Okun AH, Guerin RJ, & Schulte PA (2016). Foundational workplace safety and health competencies for the emerging workforce. Journal of Safety Research, 59, 43–51. 10.1016/j.jsr.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Hamilton AS, Wu X-C, Kato I, Schwartz SM, Smith AW, Keel G, & Keegan THM (2012). Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(19), 2393–2400. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons HM, Schmidt S, Harlan L, Kent E, Lynch C, Smith A, & Keegan T (2014). Young and uninsured: Insurance patterns of recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in the AYA HOPE Study. Cancer, 120(15), 2352–2360. 10.1002/cncr.28685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2001). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin C (2020). Cancer-related self-disclosure in the workplace/school by adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 10.1089/jayao.2019.0159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Dickson VV, Lee CS, Daus M, Hill J, Irani E, Lee S, Wald JW, Moelter ST, Rathman L, Streur M, Baah FO, Ruppert L, Schwartz DR, & Bove A (2018). A mixed methods study of symptom perception in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 47(2), 107–114. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H, & Jinks C (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk BA, Fasciano K, Block SD, & Mack JW (2020). Impact of cancer on school, work, and financial independence among adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 10.1002/cncr.33081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DS, Ganz PA, Pavlish C, & Robbins WA (2017). Young adult cancer survivors and work: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 11(6), 765–781. 10.1007/s11764-017-0614-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DS, Pavlish CL, Ganz PA, Thomas EA, Casillas JN, & Robbins WA (2019). Understanding the workplace interactions of young adult cancer survivors with occupational and environmental health professionals. Workplace Health & Safety, 67, 179–188. 10.1177/2165079918812482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauser DR, Jones A, Chiu C-Y, Tansey T, & Chan F (2015). Career development of young adult cancer survivors: A conceptual framework. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 42(2), 167–176. 10.3233/JVR-150733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CJ, Ke Y, Ng T, Tan IMJ, Goh WL, Poon E, Farid M, Neo PSH, Srilatha B, & Chan A (2020). Work- and insurance-related issues among Asian adolescent and young-adult cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 28, 5901–5909. 10.1007/s00520-020-05430-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E, & Magilvy JK (2011). Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 16(2), 151–155. 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetsch J, Wakefield C, McGill B, Cohn R, Ellis S, Stefanic N, Sawyer S, Zebrack B, & Sansom-Daly U (2017). Educational and vocational goal disruption in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 27(2), 532–538. 10.1002/pon.4525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner EL (2016). Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer, 122(7), 1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, Williams B, Firnigl D, Lang H, Coyle J, Kroll T, & MacGillivray S (2013). Supporting “work-related goals” rather than “return to work” after cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of 25 qualitative studies. Psycho-Oncology, 22(6), 1208–1219. 10.1002/pon.3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar SY, & Abernethy AP (2013). Financial toxicity, Part I: A new name for a growing problem. Oncology, 27(2), 80–81149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, & Wildemuth BM (2005). Qualitative analysis of content. Human Brain Mapping, 30(7), 2197–2206. 10.1002/hbm.20661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Han X, Zhao J, & Yabroff KR (2019). What can we do to help young cancer survivors minimize financial hardship in the United States? Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 19(8), 655–657. 10.1080/14737140.2019.1656398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.