Abstract

Motivation

Low back pain is responsible for more global disability than any other condition. Its incidence is closely related to intervertebral disc (IVD) failure, which is likely caused by an accumulation of microtrauma within the IVD. Crucial factors in microtrauma development are not entirely known yet, probably because their exploration in vivo or in vitro remains tremendously challenging. In silico modelling is, therefore, definitively appealing, and shall include approaches to integrate influences of multiple cell stimuli at the microscale. Accordingly, this study introduces a hybrid Agent-based (AB) model in IVD research and exploits network modelling solutions in systems biology to mimic the cellular behaviour of Nucleus Pulposus cells exposed to a 3D multifactorial biochemical environment, based on mathematical integrations of existing experimental knowledge. Cellular activity reflected by mRNA expression of Aggrecan, Collagen type I, Collagen type II, MMP-3 and ADAMTS were calculated for inflamed and non-inflamed cells. mRNA expression over long periods of time is additionally determined including cell viability estimations. Model predictions were eventually validated with independent experimental data.

Results

As it combines experimental data to simulate cell behaviour exposed to a multifactorial environment, the present methodology was able to reproduce cell death within 3 days under glucose deprivation and a 50% decrease in cell viability after 7 days in an acidic environment. Cellular mRNA expression under non-inflamed conditions simulated a quantifiable catabolic shift under an adverse cell environment, and model predictions of mRNA expression of inflamed cells provide new explanation possibilities for unexpected results achieved in experimental research.

Availabilityand implementation

The AB model as well as used mathematical functions were built with open source software. Final functions implemented in the AB model and complete AB model parameters are provided as Supplementary Material. Experimental input and validation data were provided through referenced, published papers. The code corresponding to the model can be shared upon request and shall be reused after proper training.

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Intervertebral discs (IVD) connect the vertebral bodies of the vertebras of the spine. They provide flexibility to the spinal column, act as dampers and transfer the loads from one vertebra to another. Failure of those structures, clinically reflected by degenerative disc disorders or disc herniation, is assumed to be highly related to low back pain, a disorder that causes more global disability than any other (Hoy et al., 2014). The IVD consists of three distinct, specialized tissues, (i) the Nucleus Pulposus (NP), i.e. the gel-like centre of the disc, (ii) the Annulus Fibrosus (AF), i.e. a concentrically layered fibrocartilage that laterally confines NP and (iii) the Cartilage Endplate (CEP) that cranially and caudally separates the NP and the inner AF from the bony endplates of the vertebra. It is widely accepted that IVD failure is the result of tissue fatigue caused by repetitive (physiological) mechanical loads (e.g. Wade et al., 2016) rather than the result of unique traumatic high impact loads (e.g. Lee et al., 2013). A suggested mechanism leading to IVD failure is the accumulation of microtrauma (micro lesions) in the IVD tissue over time, which depends on both, the external loads and the local capacity of the tissue to resist these loads. Yet, such capacity is strongly related to disc cell activity, as cells dynamically build and/or degrade extracellular matrix (ECM). Cell regulation mechanisms are still not fully understood, but local cellular behaviour is known to be guided by micro- environmental mechanical and biochemical stimuli, including nutritional stimulation. The latter is of special interest, since IVD are large avascular organs, and local disc cell nutrition relies on solute diffusion (Urban et al., 1977) from the adjacent vertebra. Therefore, important nutritional gradients exist within the NP between regions adjacent to the CEP and the mid-transversal plane (Huang et al., 2014). Biochemical solute diffusion and cell nutrition in the NP is further strain-dependent: external loads influence disc tissue porosity and therefore local amounts of metabolites (Malandrino et al., 2015), which has been called indirect mechanotransduction (Iatridis et al., 2006).

The influence of biochemical stimuli on NP cell activity has been explored through numerous in vitro studies (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2016; Neidlinger-Wilke et al., 2012; Rinkler et al., 2010). While such studies provide valuable information about the overall cell sensitivity to specific microenvironmental cues, they were not designed to capture the spatio-temporal effects of these cues. A further limitation is the limited capacity, mainly because of cost issues, to explore the combined effects of different cell stimuli. Consequently, the cellular behaviour over long time periods within a dynamic, multifactorial biochemical environment remain poorly understood. To our best knowledge, no methodology was reported so far that combines findings from different experiments in order to approach, in an integrative way, the complex environmental regulation of IVD cell behaviour. Current in silico modelling approaches to explore the IVD are to a great extent limited to Finite Element modelling (FEM). FEM integrate boundary condition (BC) and structural/composition effects in the local description of disc tissue behaviour, which could be extended to the exploration of both, direct (Van Rijsbergen et al., 2018) (i.e. the mechanical loads directly sensed by cells on their membranes) and indirect mechanotransduction (Malandrino et al., 2015), even including tissue regulation (Gu, 2014). However, the utility of FEM to simulate the dynamic biological processes responsible for IVD tissue maintenance and failure is limited. In contrast, Agent-based (AB) modelling allows approximating such processes, since it can integrate manifold biological processes, in representative tissue volume elements. AB model studies can realistically improve current understandings of biological or disease mechanisms (Holcombe et al., 2012; Olivares et al., 2016) and can be coupled with FEM studies for bottom-up explorations of tissue regulation mechanisms (Ceresa et al., 2018). To the best of our knowledge, no such approach has been developed for the IVD so far. As for other cartilaginous systems, modelling efforts have rather focused on single cell gene regulation (Kerkhofs et al., 2016) or signalling pathways (Melas et al., 2014) instead of collective cell behaviour in representative tissue. Consequently, this work focusses on the development and the evaluation of a new methodology to model the behaviour of IVD cells in representative volume elements. The methodology was designed to explicitly and robustly integrate heterogeneous experimental results through AB modelling. Simulations targeted the effect of cell multifactorial biochemical micro-environments to address indirect mechanotransduction phenomena in local tissue volumes, and predicted NP cell behaviour was assessed against individual mRNA expressions and cell viability.

2 Materials and methods

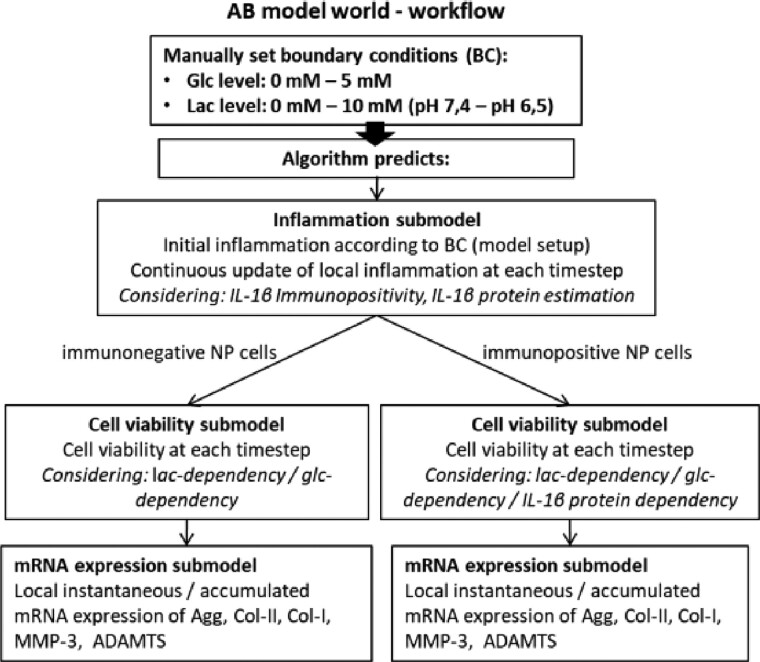

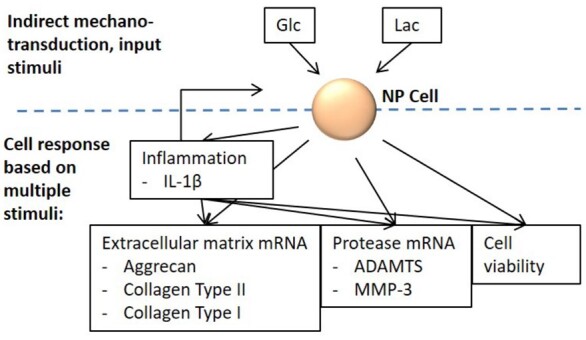

The open source software Netlogo version 6.0.2 was used to create an AB model world, consisting of a cube with a volume of 1 mm³, represented by 1000 patches. The AB model world was initially seeded with 4000 agents and each agent represented an NP cell, with a diameter of 10 µm. (Chen et al., 2009). This modelled concentration of 4000 NP cells/mm³ represented the mean cell density found in a human healthy lumbar NP (Maroudas et al., 1975). The biochemical environment of the NP cells was represented as homogenized quantities to limit the number of agents. Calculation time step-length was set to one hour. The biochemical, nutrition-related factors lactate (lac) and glucose (glc) were simulated, since they were found to be potentially important stimuli in indirect mechanotransduction (Huang et al., 2014). Additionally, cellular inflammation was deemed to affect the cellular behaviour. The AB model represented inflammation by predicting Interleukin 1β (IL-1β) mRNA expression and a corresponding amount of IL-1β protein, since this proinflammatory cytokine appears to be a key factor in IVD degeneration (Vo et al., 2013). To evaluate cellular activity, the respective mRNA expressions of the NP tissue components Aggrecan (Agg), Collagen type II (Col-II) and Collagen type I (Col-I) were simulated, as well as the expression of ECM-degrading enzymes Metalloproteinase 3 (MMP-3) and ADAMTS. Cell activity was differentiated between inflamed and non-inflamed cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of included factors in AB model simulations. Glc, glucose; Lac, lactate; IL-1β, Interleukin 1β

To estimate the effective mRNA expression over time, current cell viability was also calculated, depending on glc, lac and inflammation levels. The overall simulation workflow is described in Figure 2, and the different submodels for inflammation, cell viability and mRNA expression predictions are detailed in the next subsections. Model parameters are summarized in Supplementary Material S1.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the AB simulation workflow

2.1 mRNA expression submodel

2.1.1. Prediction of individual mRNA expressions according to varying glc and Lac concentrations

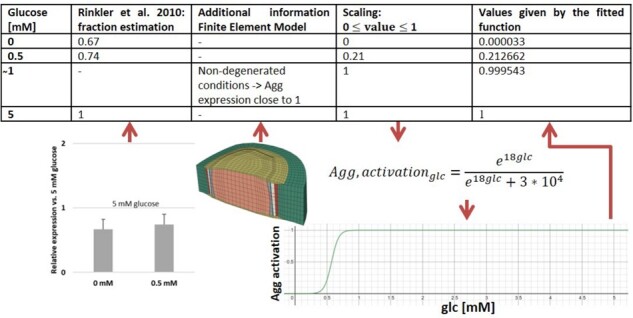

To model the influence of a metabolite, i.e. glc or lac (via pH), on cell mRNA expression, continuous mathematical functions were built based on experimental findings, usually reported as discrete semiquantitative measurements (x-fold mRNA expression compared to control). Experimental data were chosen according to cell type (human preferred, followed by bovine), degenerative status of the tissue (not-degenerated preferred over degenerated) and according to the overall consistency of the experimental findings with current knowledge. Measurements associated with both significant findings and tendencies were considered for the development of the mathematical functions. These functions were based on the studies of Saggese et al. (2018), Moroney et al. (2002), Gilbert et al. (2016) and Neidlinger-Wilke et al. (2012) (Supplementary Material S2 for more detailed information) and covered the whole physiological spectrum of metabolite concentrations. Each metabolite concentration was related to a specific mRNA expression for each protein. mRNA expressions ranged between 0 and 1, to reflect the lowest and the highest relative levels of expression, respectively (Fig. 3). The interpolation of discrete experimental measurements suggested a sigmoidal behaviour of the change of mRNA expression at critical solute concentrations. Hence, logistic functions were chosen for the interpolation of experimental points, to eventually reflect continuous changes of mRNA expressions. In many cases, experimental data suggested more than one sigmoidal shift in mRNA expression over the whole range of physiological concentrations of a stimulating solute (Gilbert et al., 2016). Therefore, a separate function was implemented for each sigmoidal shift (Fig. 4). The fitting of continuous logistic functions generally required mRNA expression measurements at three different solute concentrations at least, to obtain (i) a maximum, (ii) a minimum and (iii) an intermediate mRNA expression within a given range of solute concentrations. Curve fitting was done by using the free online graphing calculator ‘Desmos’ (https://www.desmos.com/calculator).

Fig. 3.

Visualization of the methodology to approximate continuous functions. Example of cellular activity in terms of Agg mRNA expression based on glc concentrations (Rinkler et al., 2010)

Fig. 4.

Coupling of experimental results, by using the equation from Mendoza et al. (2006). Note that pH varies from 6.5 to 7.4, thus it is represented within the function as values from 0 to 0.9

To support the function fitting process, an additional datapoint derived from a mechanotransport Finite Element model was included for the glc-dependent mRNA expression curves. Since the mechanotransport simulations predicted glc values as low as in non-degenerated NP (Ruiz Wills et al., 2018), a datapoint at 1 mM glc was added, assuming that cell activity should not be negatively altered at such glc concentration (Fig. 3). This point provided robustness for the determination of the start and growth rate of the sigmoid. All mRNA expression regulation functions are provided as Supplementary Material S3.

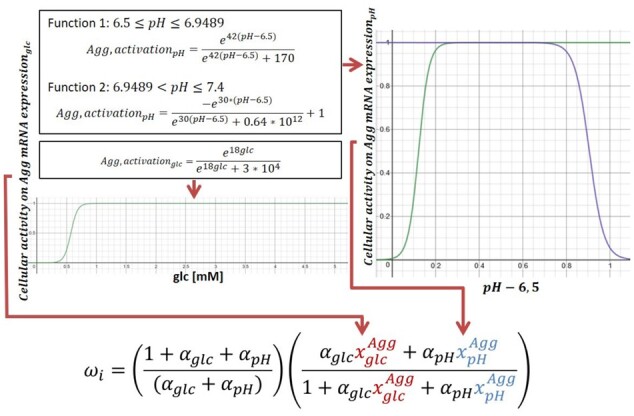

2.1.2. Prediction of overall mRNA expression in a multifactorial environment

To combine the respective influences of each stimulus on each mRNA expression, a network-based regulatory model proposed by Mendoza et al. (2006), was used. Briefly, the model equations regulate continuously the nodes of the network ( by analytically representing a traditional Boolean integration of the respective effects of activating ( and inhibiting nodes on a nodal input () (Equation 1). Originally, node regulation also depended on a decay term, which was not relevant in the present work that strictly focused on comparative analyses of the normalized effects of different cell environments. The influence of each inhibiting and/or activating node can be weighted by means of activation ( or inhibition ( factors. Finally, the way a given nodal input affects the corresponding node is determined by a gain coefficient (h).

| (1) |

In our regulatory workflow, instead of being nodes regulated by the network, and were programmed as dynamical inputs determined by the current metabolic environment of the cells (Fig. 4). Accordingly, Equation 1 integrates monofactorial controls of mRNA expressions depending on local glc, lac or IL-1β levels into fully coupled mRNA expressions ( within a multifactorial environment.

The gain factor (h) was generally chosen to approximate a linear relation between the input and the overall activation, and it was set to 1. mRNA expressions based on glc and pH were also programmed to approximate a linear activating effect on , with activation factors (α) of 0.01, according to Mendoza et al. (2006). IL-1β protein was programmed to activate MMP-3 and Col-I and to inhibit Agg, Col-II and ADAMTS mRNA expressions, in non-degenerated NP cells according to Le Maitre et al. (2005). The relative activation/inhibition strengths of IL-1β on the mRNA expressions were defined based on these findings. All activation and inhibition factors are summed up in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview over estimated weights of stimuli as either activating (α) or inhibiting (β)

| Solute | Activation/ inhibition factor | Target-mRNA |

|---|---|---|

| glc | α = 0.01 | Agg, Col I, Col II, MMP-3, ADAMTS |

| pH | α = 0.01 | Agg, Col I, Col II, MMP-3, ADAMTS |

| IL-1β protein | β = 0.03 | Agg |

| β = 0.01 | Col II | |

| α = 0.01 | Col I | |

| α = 0.05 | MMP-3 | |

| β = 0.02 | ADAMTS |

2.2 Inflammation submodel

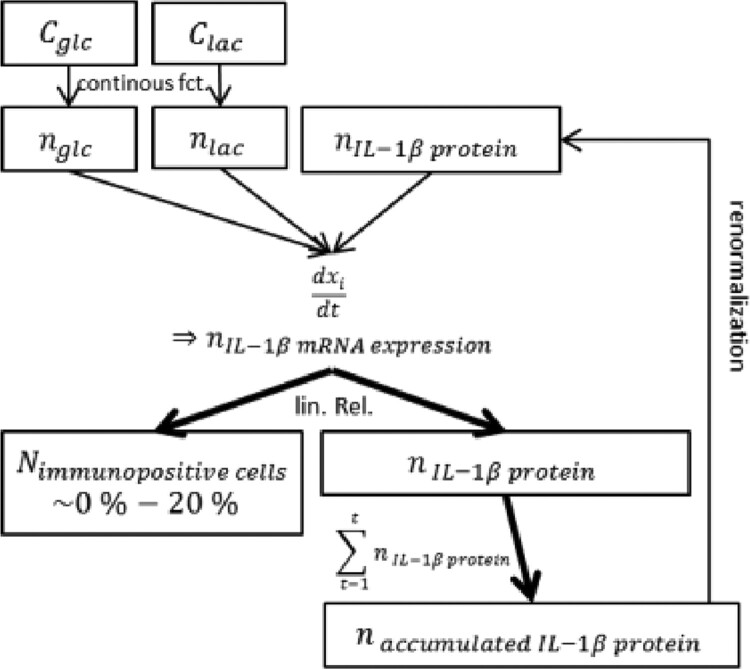

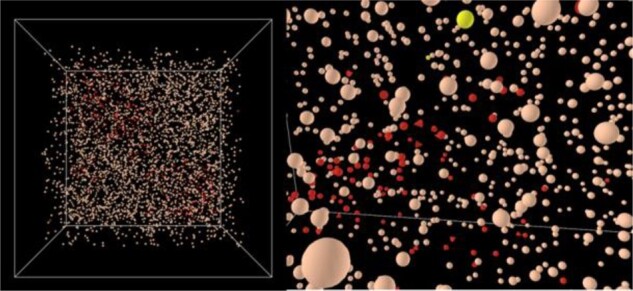

The inflammation submodel estimates the amount of immunopositive cells (cells active in terms of IL-1β mRNA expression; Fig. 5) and a corresponding, amount of IL-1β proteins.

Fig. 5.

Visualization of immunopositivity within the AB model world (left) and zoom (right). Red: NP-cells immunopositive for IL1-β. Triangle shaped: dead immunopositive cells. Yellow: proliferated cells

Initial immunopositive NP cell foci were randomly placed within the AB model world and surrounding cell clusters were formed and adapted according to the actual concentrations of glc, lac and IL-1β protein at each time step. To estimate the quantity of local immunopositive cells, overall IL-1β mRNA expression was determined using the approach from Mendoza et al. (2006). The normalized value of IL-1β mRNA expression was proportionally translated into an amount of inflamed cells, assuming a maximum of 20% of inflamed cells within a non-degenerated human NP (Le Maitre et al., 2005).

Likewise, the amount of IL-1β proteins was estimated qualitatively according to the amount of IL-1β mRNA expression by assuming a linear relationship. Half-life of IL-1β proteins was taken into account by accumulating the relative amount of IL-1β over the current and the previous time step of calculation. To consider autocrine cell simulation by IL-1β protein (mentioned in e.g. Zou et al., 2017), the accumulated amount of IL-1β protein was normalized to influence the amount of immunopositive cells via feedback loop (Fig. 6). The effect of IL-1β protein on IL-1β mRNA expression was assumed to be activating with an activation factor α of 0.03, whereas the influence of glc and lac on IL-1β mRNA was set to 0.01. Given the low travelling distance of IL-1β due to the size and the short half-life of the protein, the effect of the protein on cell viability and mRNA expression was limited to immunopositive cell-foci. The inflammation submodel was initialized prior to mRNA and cell viability calculations in order to reach a steady state of IL-1β protein concentrations based on user-defined glc and lac concentrations (Fig. 2).

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the inflammation submodel. C, concentration; N, number; n, normalized

2.3 Cell viability submodel

To estimate cell viability, continuous mathematical logistic functions and constants were established (Supplementary Material S4) according to reported experimental studies (Bibby et al., 2004; Gilbert et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016, Supplementary Material S5 for more detailed information), reflecting an hourly percentage of decay or proliferation rates based on glc, lac and, in inflamed regions, on IL-1β protein levels. Functions considered both, experimental measurements and important elements of discussions from these studies. For example, Bibby et al. (2004) suggested their obtained cell viability to be affected by plenteous cellular glycogen stores due to the high-glucose preculturing media. Consequently, they assumed an adaptation of cells to adverse conditions within the first 24 h of the 48 h experiment. In our model, the mathematical interpretation of this finding consisted in the calculation of an hourly rate of cell death over a time period of 24 h instead of 48 h. Influence of biochemical stimuli on cell viability was programmed to be additive. Experimentally, cell-death due to IL-1β was determined only for an IL-1β protein concentration of 10 ng/ml (Shen et al., 2016). Because of the incomplete knowledge about physiological concentrations of IL-1β protein within non-degenerated NP and about the critical values of IL-1β protein causing cell death, a threshold of IL-1β protein concentrations leading to cell death was arbitrarily set to half of the maximum IL-1β protein level. Finally, to estimate the influence of cell viability on mRNA expression over time (, a normalized value of living NP cells ( current amount, initial amount) was multiplied by the instantaneous amount of mRNA expression () at each time step (t) (Equation 2):

| (2) |

2.3 AB model evaluation and validation

2.3.1. mRNA expression submodel evaluation and validation

To qualitatively validate the mRNA prediction, the experimental culture conditions used by Saggese et al. (2018) with regard to pH and glc concentrations were simulated. The Authors exposed 3D bovine NP cell cultures to 5.5 and 0.55 mM glc at pH 7.0 for 24 h.

5 mM instead of 5.5 mM was chosen for AB model calculations because the selection for solute concentrations is limited to physiological ranges, where 5 mM reflects the highest glc concentration, according to the literature used to build the model regulatory functions.

To illustrate the effect of parameter variations of the equation presented by Mendoza et al. (2006), a three-level full factorial sensitivity analysis was performed. The tested parameters include the ones mentioned in Table 1, the activation of IL-1β protein on IL-1β mRNA expression and the gain coefficient, h. Up to five factors were considered: three factors, i.e. the gain coefficient and the activation of glc and pH affected both the immunopositive and immunonegative cells, whereas the respective effects of IL-1β protein on IL-1β mRNA expression and on the overall mRNA expression of structural proteins and proteases were additionally considered for the immunopositive cells. Hence, 27 and 243 simulations were used to analyse the sensitivity of the model to parameter variations, for immunonegative and immunopositive cells, respectively. The glc deprivation experiments of Saggese et al. (2018) were used to define the inputs of the model, i.e. cell activity for target-mRNA under 0.55 mM glc, pH 7.0 after 24 h. The most important findings are presented and discussed below, and the full sensitivity analysis with extended results and discussion was added as Supplementary Material S6.

2.3.2. Immunopositivity submodel evaluation

Predictions of the immunopositivity submodel were included in the validation setups for the mRNA expression submodel and the cell viability submodel.

2.3.3. Cell viability submodel validation

To validate cell viability, experimental setups of Horner et al. (2001) was simulated: during twelve days, cells were exposed to the following conditions: (i) 5 mM glc, at pH 6.0 (for the simulations, pH 6.5 was chosen, since this is the lowest value from the physiological range.); (ii) a glc-free serum, at pH 7.4.

Furthermore, the cell microenvironment imposed in the experimental setup of Saggese et al. (2018) (see Section 2.3.1, mRNA expression submodel evaluation and validation) was simulated, to evaluate the influence of cell viability on mRNA expression over time (Supplementary Material S7).

3 Results

3.1 Technical achievements

The model was computationally optimized to simulate the evolution of the system over more than four years in less than 15 min of calculation, with an ‘ordinary’ personal computer [in this study: 16 GB RAM, Intel(R) Core™ i7-7500U CPU @ 2.70 GHz (dual core)]. During the simulations, the AB model could display the normalized IL-1β mRNA expression, the corresponding IL-1β protein concentrations, the current cell viability as well as the instantaneous and accumulated (normalized) mRNA expressions of Agg, Col-I, Col-II, MMP-3 and ADAMTS for inflamed and non-inflamed cells at each timestep (1 h).

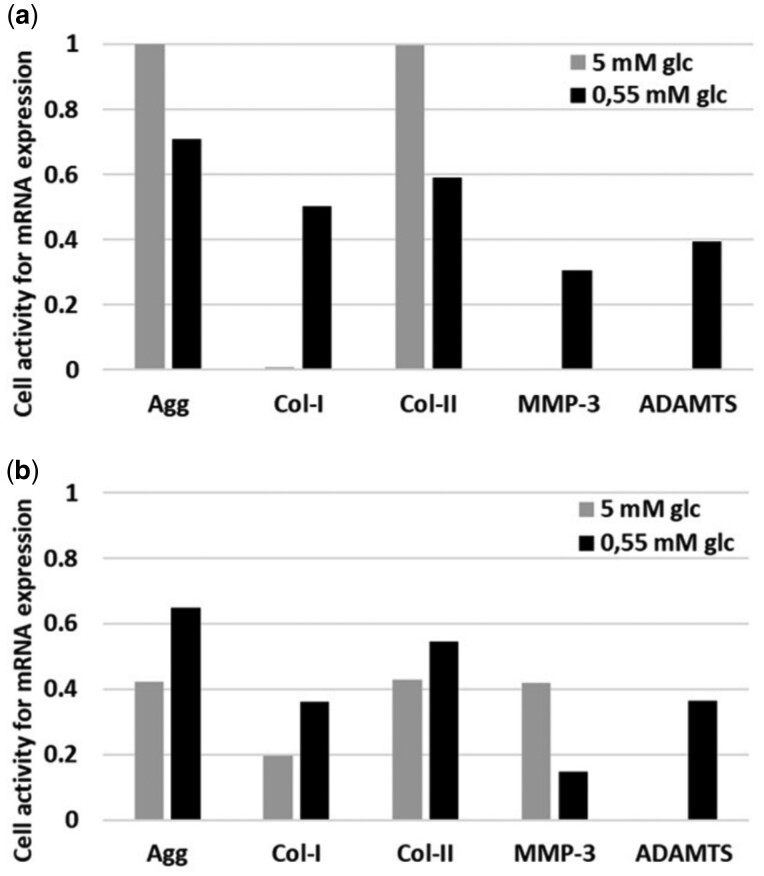

3.2 mRNA expression submodel

Under glc partial deprivation, (0.55 mM) at pH 7.0, as experimentally imposed by Saggese et al. (2018), the AB model predicted a reduction of the instantaneous mRNA expression of the ECM proteins Agg and Col-II, and an increase of the instantaneous mRNA expression of Col-I, MMP-3 and ADAMTS in the immunonegative cells (Fig. 7a). In contrast, simulating the effect of glc partial deprivation at pH 7.0 with immunopositive cells led to increased Agg, Col-I and Col-II mRNA expressions, whereas it reduced MMP-3 mRNA expression (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Instantaneous cellular activity in terms of mRNA expression of immunonegative (a) and immunopositive (b) NP cells under glc and pH BC imposed by Saggese et al. 2018 (pH 7.0)

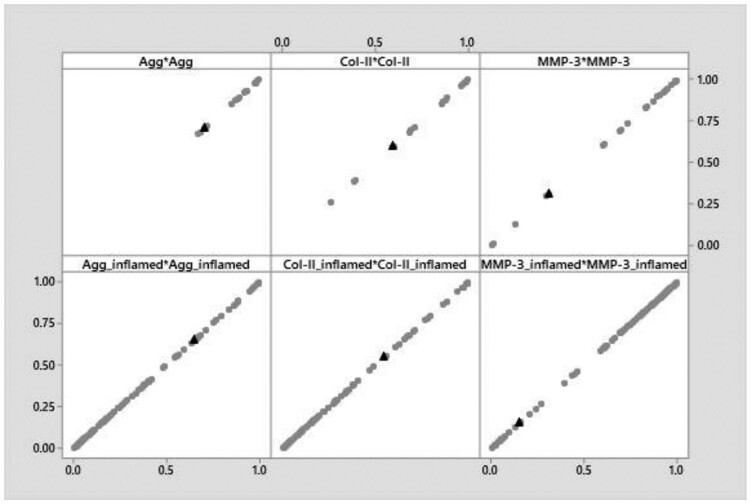

The sensitivity analysis showed that due to parameter variation, values for mRNA expression were distributed over the whole normalized range, tending to accumulate around 0 and/or 1. Only values of the Agg and Col-II mRNA expressions of immunonegative cells were always higher than 0.65 and 0.25, respectively. The parameter combination effectively used within the algorithm generally led to intermediate mRNA expressions. Representative plots for Agg, Col-II and MMP-3 are presented in Figure 8.

Fig. 8.

Parameter variation on Agg, Col-II an MMP-3 mRNA expression of immunonegative (upper row) and immunopositive cells (lower row)

3.3 Cell viability submodel

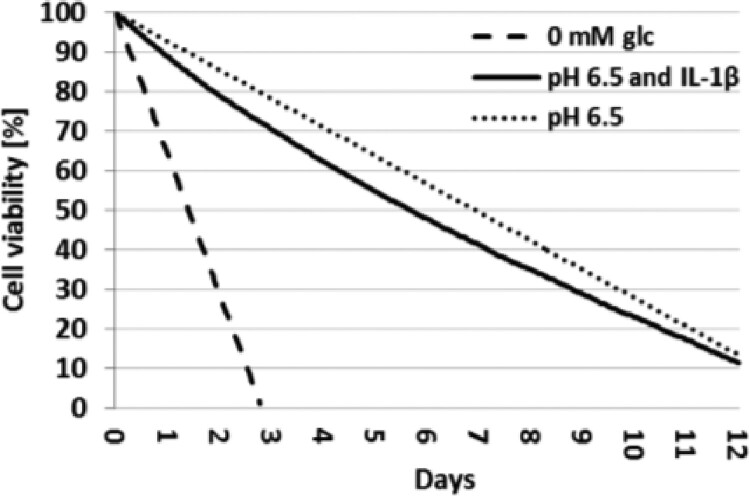

Simulations with glc and pH BC similar to those experimentally imposed by Horner et al. (2001) resulted in:

1.2% of cell viability after 2.79 days under glc deprivation.

cell viability decrease to around 71% (78% if immunopositivity is not considered) after three days, to around 41% (50% if immunopositivity is not considered) after 7 days and to around 11% (14% if immunopositivity is not considered) after 12 days, in acidic environment (pH 6.5) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Simulation of cell viability over days in either glc-free medium or acidic environment, with and without the effect of IL-1βprotein

Cell decay due to relatively high IL-1β protein levels (i.e. more than half of the maximum permitted) was only activated under acidic conditions.

4 Discussion

To our knowledge, the presented AB model is the first in silico model that allows to predict the behaviour of an IVD cell population within a multifactorial environment. By its ability to simulate cell behaviour over long periods of time, it gathers key requirements to reveal cellular dynamics implicated in IVD failure, since disc tissue degeneration is a slow process that we hypothesize to be biologically driven under physiological levels of cell microenvironmental cues. Importantly, our modelling approach uniquely allows the combination of existing knowledge to predict the effects of multiple interplays on cellular activity. On the one hand, experimental research providing detailed information, e.g. typical sigmoidal shifts of cell activity upon single stimulation, is crucial to enhance the model performance of such an evidence-based approach. On the other hand, an appropriate design of the algorithm that allows straightforward modifications of individual regulatory functions according to new experimental findings is essential.

In the following sections, the performance of the model is discussed in the light of independent experimental data and current knowledge.

4.1 mRNA expression submodel

The experimental data reported by Saggese et al. (2018) used combinations of pH and glc concentrations (7.0, 0.55 mM) that allowed evaluating the response of the AB model to combined variations of solute concentrations different from those used to build our individual regulatory functions. The predicted behaviour of non-inflamed NP cells to such glc and pH combinations (Fig. 7a) is not surprising and supported by the widely accepted paradigm of catabolic shift in cell activity under glc deprivation, characterized by an overall decline of ECM protein mRNA expression and an increase in protease mRNA expression (Neidlinger-Wilke et al., 2012; Rinkler et al., 2010). Likewise, the predicted augmentation of Col-I expression was expected and is well supported by the literature, since replacement of Col-II with Col-I fibres (fibrosis) could be observed in degenerated NPs (Urban et al., 2003; Wuertz et al., 2009). Thanks to our novel modelling approach, such shifts are now quantifiable and comparable for different user-defined conditions.

Remarkably, while the results obtained by Saggese et al. (2018) under glc deprivation support the general assumption that adverse disc cell microenvironments tend to increase Col-I and MMP-3 mRNA expression (ADAMTS is excluded from validation as those data were used as input for AB model programing), they reveal a tendency toward increased Agg and Col-II mRNA expressions, against common expectations. This was not further discussed by the Authors because significance was not reached. Interestingly, our AB model also showed higher Agg and Col-II mRNA expressions under glc deprivation, but only for the immunopositive cells (Fig. 7b). Assumingly, this result emerged because IL-1β protein release, and the possible adverse effect thereof on cell activity, is higher at higher glc levels. Hence, less glc, less IL-1β in inflamed cells. This novel insight in cellular behaviour within a complex micro-environment suggests that inflammation might shed light on the unexplained experimental findings of Saggese et al. (2018).

Figure 7b shows that at 5 mM glc, the relative mRNA expression of MMP-3 by immunopositive cells was about 0.4, while by immunonegative cells (Fig. 7a) kept a minimum amount (i.e. 0.0) of relative MMP-3 mRNA expression. These findings agree with the common association between inflammation and catabolic shift in NP cell activity (Le Maitre et al., 2005). Actually, the catabolic shift in cellular activity was considerable in presence of IL-1β (Fig. 7a versus Fig. 7b), such a result is supported by the many evidences that point out sustained inflammation as crucial factor in IVD rupture (e.g. Kepler et al., 2013). However, comparing MMP-3 mRNA expression under glc deprivation for IL-1β immunopositive and immunonegative cells (Fig. 7a versus Fig. 7b), model predictions suggest a lower MMP-3 mRNA expression in inflamed cells, even though MMP-3 is programmed to be highly activated by IL-1β (Table 1). This apparent incoherence seems to be numerically based and related to the use of the equations of Mendoza et al. (2006) (Equation 1) with activation factors below 1. Beta-testing showed that this artefact would vanish with activation factors of . Such limitations must be taken into account for future model developments and interpretations.

To estimate effective inflammation, a linear relationship between IL-1β mRNA expression and the quantity of IL-1β proteins was presumed, which could be roughly observed in experimental studies (Gilbert et al., 2016). However, more detailed knowledge about the relationship between mRNA expression and the corresponding amount of synthesized IL-1β proteins, or about the half-lives of IL-1β protein- or mRNA is required. In the present work, the half-life of IL-1β proteins has been approximated from distantly related studies (Kudo et al., 1990; Larson et al., 2006) and needs to be updated when more accurate data become available.

So far, IL-1β mRNA expression is the only factor that determines the amount of IL-1β protein, but other factors are suggested to affect the levels of IL-1β protein, e.g. MMP-3 might degrade IL-1β (Ito et al., 1996). Thus, further development of the inflammation submodel should include a more sophisticated feed-back looped network for the dynamic regulation of the effective influence of IL-1β. Furthermore, regulations and effects of additional proinflammatory cytokines are deemed to be crucial in microtrauma development. In particular, the emergence and the role of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α, handed as a possible initiating factor in IVD degeneration (Millward-Sadler et al., 2009) should be modelled, but such necessary developments are currently hindered by limited experimental evidences in the literature.

The results of the sensitivity analysis (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Material S6) showed that a rigorous variation of the equation parameters allow to importantly influence the overall mRNA expression, unless the input parameters of a node were considerably high (or low) such as in case for Agg and Col-II under non-inflamed conditions. Given that the equation parameters allow to reflect almost linear and Boolean behaviour and intermediate, sigmoidal steps to connect those extrema, this result was not surprising, and highlighted again the importance of a prudent choice of model parameters. In this approach, our default h value was chosen to approximate a linear coupling between the model outputs, , and the corresponding total inputs, (Equation 1), which allowed to reflect the interactions of the biologically derived inputs (fitted curves) without any additional mathematical distortion. Values of the activation/inhibition factors, i.e. 0.01, were also chosen to approximate linear variations of with the respective concentrations of inhibitors and activators, and to preserve the influence of the individual experimental profiles of mRNA expression for each stimulus. Wherever additional strength should be conferred to a specific activator or inhibitor, activation/inhibition factor values can be increased to progressively induce controlled non-linearity. For future model developments, it might be welcome to develop an approach to systematically determine activation/inhibition factors of different stimuli in order to optimally adjust the model behaviour to biological evidence. In the meantime, our specific default parameter values provided reasonable results, according to prior knowledge about NP cell behaviour.

The presented model aimed to simulate indirect mechanotransduction phenomena. Apart from glc and pH, the role of oxygen on NP cell activity and indirect mechanotransduction is also discussed in literature. However, oxygen was not considered in the present model so far, since the implementation of oxygen effects is hindered by a lack of experimental data on cell behaviour at physiological oxygen levels [1–5% (Mwale et al., 2011)] within the NP. Arguably, this is not considered as a crucial limitation, since oxygen levels were reported to have a low effect on the gene expressions hereby simulated, compared to glc and pH (Neidlinger-Wilke et al., 2012). Importantly, our specific model design permits an easy implementation of additional stimuli, allowing for future incorporation of phenomena, e.g. oxygen or direct mechanotransduction (Baumgartner et al., 2019) effects, for more complete simulations of the microenvironment of NP cells.

The functions that relate glc or pH to mRNA expressions of genes were built by considering both significant changes and variation tendencies of mRNA expression, among the different experimental reports used. The reason to take into account variation tendencies is, on the one hand, that the high variability in cellular behaviour comonly seen in experimental studies often hinders to reach significance. On the other hand, we hypothesize that the persistence over time of small changes measured in vitro can have clear effects over long time periods. Such hypothesis implies that we hereby consider the chronicity of the cell stimulators studied. Obviously, further model extensions should capture the time variations of these stimulators and the effects thereof, including any possible transient effects. At the nutrition level, such variations can be extracted from long-term Finite Element analyses (Ruiz Wills et al., 2016). Coupled to a mechanotransport Finite Element model such as the one presented by (Ruiz Wills et al., 2018), this AB model is able to predict local cellular behaviour according to given solute concentrations at the millimetre scale in whatever user-defined region of the NP. The model can be additionally exploited to simulate possible critical cell microenvironments worth to be experimentally explored, e.g. environments around 1 mM glc concentration (Ruiz Wills et al., 2018). Furthermore, the AB model could be enriched with solute-transport and metabolic submodels that consider diffusion and metabolic cell processes to autonomically level mRNA expression in different regions of the AB model.

4.2 Cell viability submodel

Predicted cell viability was in good agreement with independent, experimental data of Horner et al. (2001), who observed a decrease in cell viability to about 65% and 50% (cells cultured without oxygen) after three and seven days exposed to low pH. In comparison, our AB model predicted 78 and 50% of viability if the influence of IL-1β is not considered, and 71 and 41% of cell viability otherwise, after three and seven days of exposure to low pH, respectively (Fig. 9). Arguably, the minimum pH for our pH-dependent cell regulation curves depended on the lowest pH, i.e. 6.5, found within the experimental studies. In contrast, the experimental study used for independent validation was conducted at pH 6.0. Hence, whether the model might have slightly overestimated the cell viability remains to be explored.

With regard to complete glc deprivation, a cell viability of 1.2% after 2.79 days was predicted by the model (Fig. 9), which nicely agrees with the experiments of Horner et al. (2001) where cells died within three days without glc.

As a limitation, it must be mentioned that the cell viability submodel currently considers cell viability based on additive contributions of biochemical factors (glc, pH and IL-1β protein). Truly, experimental observations (Bibby et al., 2004) suggested that coupled factor influences exist. For further model developments, more independent data about cell death in low glc and high acidic environments would be needed to evaluate whether model predictions significantly differ from observed results. Nevertheless, a future development of the cell viability submodel may include a determination of cell viability by using network-based integrative approaches, able to weight the influence of each environmental stimulus individually. Finally, the average cell size of 10 µm might be slightly underestimated by a few micrometres, which however does not affect the interpretation of the results of the model.

5 Conclusion

This investigation aimed to develop and test new modelling and simulation techniques in IVD research for bottom-up virtual exploration of disc tissue regulation and of the negative perturbation thereof. Especially, the presented hybrid model exploited state-of-the-art AB and network modelling approaches. The AB model was fed with experimental data to mimic the cellular behaviour in a complex biochemical environment, which stands for a huge challenge, not only in IVD research, but in highly multifactorial disorders in general, where the nature and the control of the physicochemical cellular microenvironments greatly matter. Our new developed methodology successfully integrated discrete, experimental results into continuous cell behaviour functions and exploited existing network approaches from systems biology to merge individually weighted stimuli into fully coupled mRNA expressions, which allows for the first time to quantify and compare cell activity under user-defined glc and lac concentrations.

First validation tests showed that the AB model predictions agree with different types of independent experimental findings, and simulations led to novel insights in cellular behaviour within a multifactorial environment. Moreover, the AB model provides rational clues to explain for the first time unexpected experimental results retrospectively. This shows the ability of in silico predictions to contribute to goal-orientated, systematic experimental research and tackle IVD degeneration in an interdisciplinary approach. Thus, feeding a network approach from systems biology with biological data and admitting a direct interference of local environmental conditions seems to be a promising approach for future research.

The strength of this approach is its ability to anticipate and compare new plausible scenarios where experimental quantification is still lacking. Furthermore, it enables an integration of heterogeneous, experimental data including cells of different species, differences in cell culturing protocols and degeneration levels of IVD tissue as well as dealing with a lack of data. Importantly, the present methodology permits an easy integration of additional stimuli, and updates of the current regulatory functions as soon as new experimental results/findings become available.

Most probably, the NP represents a delicately balanced dynamical system, as local alterations in mRNA expression might lead to local alterations of protein expression. A subsequent, local change in matrix density includes local alterations of tissue porosity at the micrometre scale, which in turn affects local solute concentrations. Therefore, one of the long-term objectives of our work is to couple this AB model with a local Finite Element model, providing continuous feedback about local changes in porosities and the effect of interactions at the microscale level on the millimetre scale tissue integrity, which allows a more holistic understanding and description of the dynamics that finally define the crucial mechanisms for microtrauma accumulation and the great diversity of phenotypes in IVD failure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Dr. Carlos Ruiz Wills for providing the figure of the IVD Finite Element Model (Figure 3).

Contributor Information

L Baumgartner, BCN MedTech, Department of Information and Communication Technologies, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 08018 Barcelona, Spain.

J J Reagh, BCN MedTech, Department of Information and Communication Technologies, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 08018 Barcelona, Spain; University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA.

M A González Ballester, BCN MedTech, Department of Information and Communication Technologies, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 08018 Barcelona, Spain; ICREA, Pg. Lluis Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain.

J Noailly, BCN MedTech, Department of Information and Communication Technologies, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 08018 Barcelona, Spain.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Information and Communication Technologies of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, the Whitaker International Fellows and Scholars Program, the Spanish Government [RYC-2015-18888, MDM-2015-0502, HOLOA-DPI2016-80283-C2-1-R] and the European Commission [Disc4All-MSCA-2020-ITN-ETN 955735].

Conflict of Interest: None of the Authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Baumgartner L. et al. (2019) Simulation of the multifactorial cellular environment within the intervertebral disc to better understand microtrauma emergence. In: Short Communication, International Research Council on the Biomechanics of Injury (IRCOBI) Conference, Florence, Italy, IRC-19-67. pp. 484–485.

- Bibby S.R.S. et al. (2004) Effect of nutrient deprivation on the viability of intervertebral disc cells. Eur. Spine J., 13, 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceresa M. et al. (2018) Coupled immunological and biomechanical model of emphysema progression. Front. Physiol., 9, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. (2009) Expression of laminin isoforms, receptors, and binding proteins unique to nucleus pulposus cells of immature intervertebral disc. Connect. Tissue Res., 50, 294–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert H.T.J. et al. (2016) Acidic pH promotes intervertebral disc degeneration: acid-sensing ion channel -3 as a potential therapeutic target. Sci. Rep., 6, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu,W. et al. (2014) Simulation of the Progression of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Due to Decreased Nutritional Supply. Spine, 39, E1411–E1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe M. et al. (2012) Modelling complex biological systems using an agent-based approach. Integr. Biol., 4, 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner H.A. et al. (2001) 2001 Volvo award winner in basic science studies: effect of nutrient supply on the viability of cells from the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila. PA. 1976), 26, 2543–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy D. et al. (2014) The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis., 73, 968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.C. et al. (2014) Intervertebral disc regeneration: do nutrients lead the way? Nat. Rev. Rheumatol., 10, 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis J.C. et al. (2006) Effects of mechanical loading on intervertebral disc metabolism in vivo. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am., 88, 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A. et al. (1996) Communications : degradation of interleukin 1 β by matrix metalloproteinases degradation of interleukin 1  by matrix metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 14657–14661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler C.K. et al. (2013) The molecular basis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J., 13, 318–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhofs J. et al. (2016) A qualitative model of the differentiation network in chondrocyte maturation: a holistic view of chondrocyte hypertrophy. PLoS One, 11, e0162052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S. et al. (1990) Clearance and tissue distribution of recombinant human interleukin 1b in rats. Cancer Res., 50, 5751–5755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J.W. et al. (2006) Biologic modification of animal models of intervertebral disc degeneration. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am., 88, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-W. et al. (2013) Traumatic intradural lumbar disc herniation without bone injury. Korean J. Spine, 10, 181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre C.L. et al. (2005) The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of human intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis Res. Ther., 7, R732–R745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandrino A. et al. (2015) Poroelastic modeling of the intervertebral disc: a path toward integrated studies of tissue biophysics and organ degeneration. MRS Bull., 40, 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Maroudas A. et al. (1975) Factors involved in the nutrition of the human lumbar intervertebral disc: cellularity and diffusion of glucose in vitro. J. Anat., 120, 113–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melas I.N. et al. (2014) Modeling of signaling pathways in chondrocytes based on phosphoproteomic and cytokine release data. Osteoarthr. Cartil., 22, 509–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza L. et al. (2006) A method for the generation of standardized qualitative dynamical systems of regulatory networks. Theor. Biol. Med. Model., 3, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward-Sadler S.J. et al. (2009) Regulation of catabolic gene expression in normal and degenerate human intervertebral disc cells: implications for the pathogenesis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis Res. Ther., 11, R65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney P.J. et al. (2002) PH and anti-inflammatory agents modulate nucleus pulposus cytokine secretion. In Proceedings of the NASS 17th Annual Meeting/The Spine Journal., 2, pp. 49S–50S.

- Mwale F. et al. (2011) Effect of oxygen levels on proteoglycan synthesis by intervertebral disc cells. Spine (Phila. PA. 1976), 36, 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidlinger-Wilke C. et al. (2012) Interactions of environmental conditions and mechanical loads have influence on matrix turnover by nucleus pulposus cells. J. Orthop. Res., 30, 112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares A.L. et al. (2016) Virtual exploration of early stage atherosclerosis. Bioinformatics, 32, 3798–3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijsbergen M. et al. (2018) Comparison of patient-specific computational models vs. clinical follow-up, for adjacent segment disc degeneration and bone remodelling after spinal fusion. PLoS One, 13, e0200899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinkler C. et al. (2010) Influence of low glucose supply on the regulation of gene expression by nucleus pulposus cells and their responsiveness to mechanical loading. J. Neurosurg. Spine, 13, 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Wills C. et al. (2016) Simulating the sensitivity of cell nutritive environment to composition changes within the intervertebral disc. J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 90, 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Wills C. et al. (2018) Theoretical explorations generate new hypotheses about the role of the cartilage endplate in early intervertebral disk degeneration. Front. Physiol., 9, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggese T. et al. (2018) Differential response of bovine mature nucleus pulposus and notochordal cells to hydrostatic pressure and glucose restriction. Cartilage, 0, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J. et al. (2016) SIRT1 inhibits the catabolic effect of IL-1 beta through TLR2/SIRT1/NF-kappa B pathway in human degenerative nucleus pulposus cells. Pain Phys., 19, E215–E226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J.P. et al. (1977) Nutrition of the intervertebral disk. An in vitro study of solute transport. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 129, 101–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J.P.G. et al. (2003) Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res. Ther., 5, 120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo N.V. et al. (2013) Expression and regulation of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in interertebral disc aging and degeneration. Spine J, 13, 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade K.R. et al. (2016) ISSLS prize winner: vibration really disrupt the disc: a microanatomical investigation. Spine (Phila. PA. 1976), 41, 1185–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuertz K. et al. (2009) In vivo remodeling of intervertebral discs in response to short- and long-term dynamic compression. J. Orthop. Res., 27, 1235–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J. et al. (2017) Effect of a low-frequency pulsed electromagnetic field on expression and secretion of IL-1β and TNF-α in nucleus pulposus cells. J. Int. Med. Res., 45, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.