Abstract

Previous herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) vaccines have not prevented genital herpes. Concerns have been raised about the choice of antigen, the type of antibody induced by the vaccine, and whether antibody is present in the genital tract where infection occurs. We reported results of a trial of an HSV-2 replication-defective vaccine, HSV529, that induced serum neutralizing antibody responses in 78% of HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients. Here we show that HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients developed antibodies to epitopes of several viral proteins; however, fewer antibody epitopes were detected in vaccine recipients compared with naturally infected persons. HSV529 induced antibodies that mediated HSV-2–specific natural killer (NK) cell activation. Depletion of glycoprotein D (gD)–binding antibody from sera reduced neutralizing titers by 62% and NK cell activation by 81%. HSV-2 gD antibody was detected in cervicovaginal fluid at about one-third the level of that in serum. A vaccine that induces potent serum antibodies transported to the genital tract might reduce HSV genital infection.

Keywords: herpes simplex, genital herpes, herpesvirus, vaccine, replication-defective vaccine, HSV-2, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, glycoprotein D

Recipients of a herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) vaccine trial had antibodies to fewer viral epitopes compared with natural infection, HSV gD antibodies in cervicovaginal fluid at one-third the level of those in serum, and antibodies that mediated HSV-2–specific natural killer cell activation.

The immune responses necessary for an effective genital herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) prophylactic vaccine are unknown. Studies of serum or cord blood from neonates showed that neutralizing antibody and antibody that mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) correlates with protection from infection [1–4]. The pathogenesis of neonatal HSV-2 infection is different from that of genital herpes infection, but HSV-specific antibody in the genital tract likely has a role in protection from genital infection. Vaccination of HSV-1–/HSV-2– adults with an HSV-2 glycoprotein D (gD) subunit vaccine showed that serum antibody to HSV-2 gD correlated with protection from HSV-1, but not HSV-2, genital infection [5]. While most clinical trials of prophylactic HSV-2 vaccines have used individual viral proteins [5–7], their lack of success suggests that vaccines with more HSV-2 proteins might induce a broader, more potent immune response. Previous studies showed that some HSV-2 subunit vaccines induced serum antibodies that can mediate ADCC [8, 9]. While serum antibodies were measured in recent subunit vaccine trials, antibody levels in the genital tract, the site of infection of HSV-2 in adults, were not assessed.

We recently completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the replication-defective HSV529 vaccine. We found that the vaccine induced serum HSV-2 neutralizing antibody and HSV-2–specific T cells [10]. Unlike subunit vaccines, HSV529 is expected to produce most HSV-2–encoded proteins in vaccine recipients. Here we report the use of a random peptide display library to obtain an unbiased analysis of HSV-2 epitopes targeted by antibodies induced by HSV529 in HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients and compare these results with epitopes targeted during natural infection. In addition, we measured levels of serum antibody that mediate HSV-2–specific natural killer (NK) cell activation, a surrogate for ADCC, in HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients and levels of HSV-2 gD-specific antibody in cervicovaginal fluid after vaccination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial Design, Participants, Vaccine, and Study Procedures

The HSV529 phase 1 human trial (NCT01915212) has been previously described [10]. Participants were divided into 3 groups: those seropositive or seronegative for HSV-1 and seropositive for HSV-2 (HSV-1±/HSV-2+), those positive for HSV-1 and negative for HSV-2 (HSV-1+/HSV-2–), and those negative for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 (HSV-1–/ HSV-2–). Each group of 20 participants was randomized into 2 subgroups: (1) 15 participants received HSV529 vaccine (HSV-2 strain 186 deleted for UL5 and UL29 [Sanofi Pasteur]) on days 0, 30, and 180; and (2) 5 participants received normal saline (placebo). Blood samples were collected at various time points and serum was stored at –80°C.

Cervicovaginal fluid samples were self-collected by some of the participants using a vaginal cup (Instead Softcup) inserted for about 1 hour on day 0 and day 210 (30 days after the third vaccination). Samples were extracted with 1 volume of phosphate-buffered saline containing proteinase inhibitors at room temperature for 30 minutes. After centrifugation, supernatants were stored at –80°C.

Serum HSV-2 Neutralization, gD Binding, and ADCC Assays

HSV-2 neutralization [11], gD binding [12], and ADCC [13] assays were performed as described previously. Additional details are shown in the Supplementary Data.

Serum HSV Antibody Epitope Repertoire Analysis

Sera from HSV-1–/ HSV-2– vaccine recipients and from naturally infected volunteers were subjected to serum epitope repertoire analysis (SERA) [14]. Additional details are shown in the Supplementary Data.

Statistical Analysis

Correlations for serum ADCC activity with serum neutralizing titers and for cervicovaginal fluid gD antibody titers with serum gD antibody titers were performed using nonparametric Spearman rho (ρ). Two-sided paired t tests were used to compare baseline to follow-up measurements. A log10 transformation was used in the analysis of the antibody titers to help stabilize the variance.

RESULTS

Vaccination of HSV-1–/HSV-2– Subjects With HSV529 Induced Antibodies to a More Limited Set of Viral Proteins Than Those Detected in Naturally Infected Persons

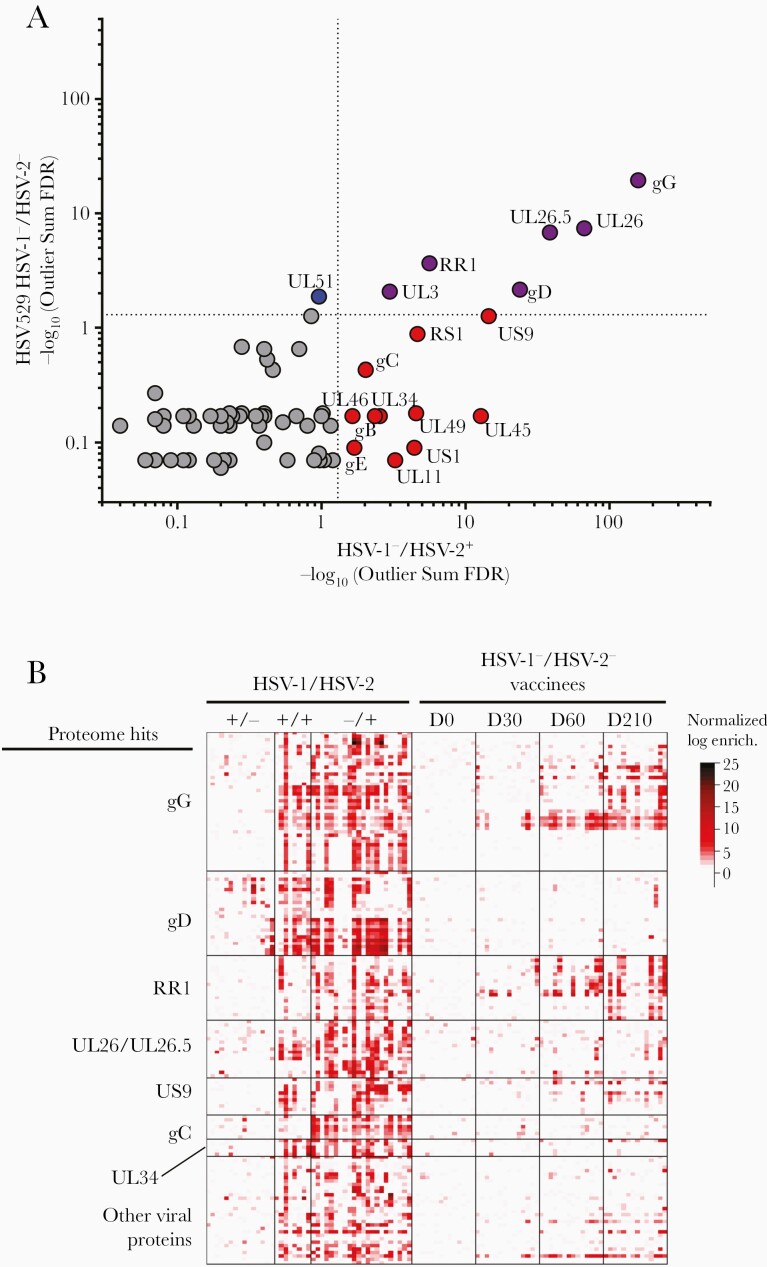

We utilized the SERA platform to identify antibody epitopes in HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects after vaccination with HSV529. Serum samples from day 0 (before vaccination) of 15 HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects and from 33 other, nonvaccinated HSV-1–/HSV-2– persons served as negative controls. Additionally, serum from 15 HSV-1±/HSV-2+ subjects (obtained before HSV529 vaccination) and from an additional 57 HSV-1–/HSV-2+ persons were analyzed to discover antibody epitopes associated with natural infection. First, a protein-based immunome-wide association study (PIWAS) was used to identify significantly enriched HSV-2 antigens associated with HSV529 vaccination and HSV-2 natural infection. HSV-2 strain SD90e protein sequences were used as reference sequences for epitope mapping, and HSV-2 proteins were ranked by significance of epitope enrichment. Six HSV-2 proteins were significantly enriched in both vaccinated and naturally infected cohorts including glycoprotein G (gG), UL26/UL26.5, the large subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (RR1), gD, and UL3, 11 significant only in naturally infected subjects, and 1 significant in only HSV529 vaccine subjects (UL51) (Figure 1A). The most frequent epitope motifs were identified and grouped based on the virus proteins in which they were located. Sequences of epitope motifs were listed in order based on the amino acid position in the corresponding HSV protein (Supplementary Table 1). A high frequency of antibodies mapped to epitopes in gG, gD, RR1, the UL26/UL26.5 protease and capsid scaffolding protein, the US9 membrane protein, glycoprotein C, and the UL34 nuclear membrane protein (Supplementary Table 1; Figure 1B). In contrast, sera from HSV-1+/HSV-2– persons had low frequencies of antibodies that mapped to HSV-2 epitopes, indicating a low level of cross-reactivity between HSV-1 and HSV-2 epitopes, except for epitopes in gD conserved between HSV-1 and HSV-2. Sera from 14 HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients, collected 1 month after the first (day 30), second (day 60), and third dose (day 210) of vaccine, had significantly enriched antibody-binding epitopes to 7 HSV-2 proteins (gG, RR1, UL26/UL26.5, gD, UL3, and UL51), which increased over time after vaccination.

Figure 1.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)–enriched epitope motifs identified using serum epitope repertoire analysis (SERA) recognized by antibodies in sera from HSV529 trial participants or herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and/or HSV-2 naturally infected subjects. A, Statistically significant HSV-2 antigens identified by protein-based immunome-wide association study (PIWAS) in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients and HSV-1–/HSV-2+ naturally infected subjects, ranked using the outlier sum false discovery rate (FDR). Six proteins were significant (FDR <.05) in both cohorts including gG, UL26.5/UL26 (the epitopes were all in the region that overlaps both UL26.5 and UL26), RR1, gD, and UL3 (purple), 11 significant only in naturally infected subjects (red), and 1 significant in only HSV529 subjects (blue). B, Heatmap of enrichments for epitope motifs from HSV-2 proteins. HSV-1/HSV-2 serostatus is indicated at the top of the figure. Each column of the heatmap represents data from 1 subject and each row represents an epitope motif. Colors indicate z scores for each epitope. Heatmap shows the 7 HSV-2 proteins identified as significant by PIWAS with >2 epitope motifs recognized in natural infection or vaccine recipients. The strongest responses in vaccine recipients is to epitope motifs in gG and RR1 with weaker responses to gD, UL26/UL26.5, US9, gC, and other viral proteins.

Analysis of Enriched Epitopes

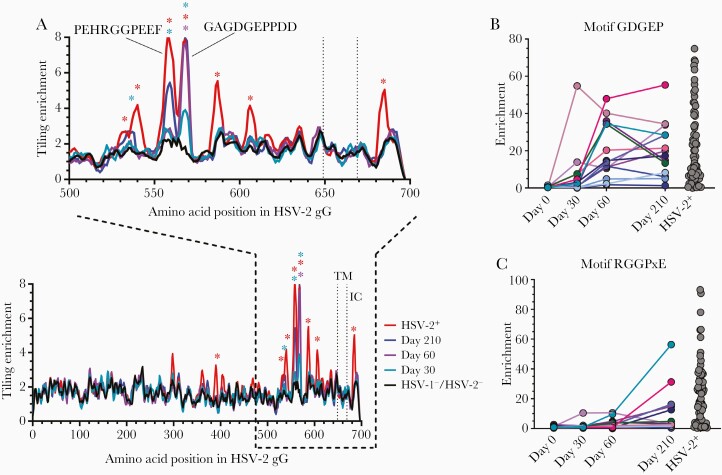

The 2 most enriched epitopes in the HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients’ sera mapped to gG (Figure 1A). One gG epitope, GAGDGEPPDD, was significantly enriched at days 60 and 210, and nonsignificantly enriched at 1 month after the first dose of vaccine (Figure 2A) This epitope overlaps with the sequence of a gG peptide (EPPDDDDS) that induces HSV-2 neutralizing antibody in mice [15]. The enrichment of this epitope in the HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients was equivalent to that in sera of HSV-2 naturally infected subjects. In contrast, another gG epitope, PEHRGGPEEF, was only significantly enriched 1 month after the third dose of vaccine and did not reach the level observed in naturally infected persons. The HSV-2 naturally infected subjects had several additional enriched epitopes that were not enriched in the HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients. Antibody to the GDGEP motif (located within the GAGDGEPPDD epitope) peaked at different times in vaccinated subjects (including 1 person whose level peaked at day 30) (Figure 2B), whereas antibody to the RGGPxE motif (a subset of the PEHRGGPEEF epitope) generally peaked after the third dose of vaccine (Figure 2C). Thus, whereas antibody to some gG epitopes in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients was enriched to the level observed in naturally infected persons, antibody to other epitopes was not.

Figure 2.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) gG epitope motifs recognized by antibodies in herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)/HSV-2–negative HSV529 vaccine recipients and HSV-2 naturally infected subjects. A, Tiling analysis for HSV-2 gG shows epitope motifs from HSV-2+ (n = 72), HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients (n = 14) at various days after vaccination, and HSV-1–/HSV-2– controls (n = 48). Epitopes determined to be significantly enriched are denoted by asterisks (false discovery rate <.05), and transmembrane (TM) and intracellular (IC) domains are labeled. The kinetics of antibodies binding to motifs GDGEP (B) and RGGPxE (C) in serum for individual HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients or HSV-2 naturally infected persons is shown.

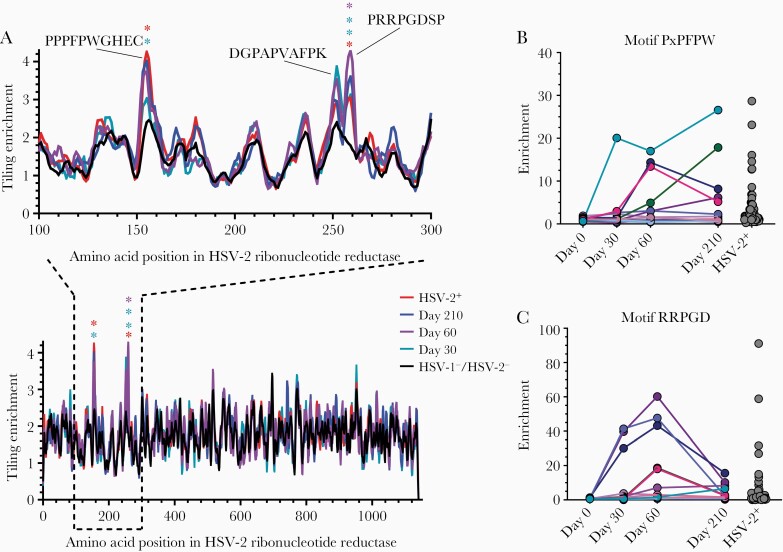

Vaccination of HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects with HSV529 elicited a strong response to RR1. The RR1 epitope PPPFPWGHEC was significantly enriched in the sera of HSV529-vaccinated subjects at day 210 as well as HSV-2 naturally infected persons; in contrast, the RR1 epitope PRRPGDSP was significantly enriched in sera at all 3 postvaccination time points and in HSV-2 naturally infected persons (Figure 3A). The RR1 epitope DGPAPVAFPK had elevated enrichment in sera of vaccine recipients at days 30 and 60. Several epitopes in RR1, including the epitopes DGPAPVAFPK and PRRPGDSP, were more enriched in the HSV529 vaccine recipients than in HSV-2+ naturally infected subjects. Like the differences in antibody kinetics seen with different motifs of gG, antibody to PxPFPW motif (a subset of RR1 epitope PPPFPWGHEC) peaked at various times after vaccination (Figure 3B), whereas antibody to the RRPGD motif (part of RR1 epitope PRRPGDSP) peaked at day 60 (Figure 3C). Thus, within a single protein, the kinetics of the antibody response to specific epitopes may markedly differ after vaccination.

Figure 3.

Epitopes to the large subunit of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) ribonucleotide reductase recognized by antibodies in sera. A, Tiling analysis for sera from HSV-2+ subjects (n = 72), HSV529 vaccine recipients (n = 14) at various days after vaccination, and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)/HSV-2–negative controls (n = 48) to epitopes of the large subunit of the HSV-2 ribonucleotide reductase. Epitopes determined to be significantly enriched are denoted by asterisks (false discovery rate <.05). Sera for individual HSV529 vaccine recipients at various times after vaccination or HSV-2+ persons were analyzed for antibody to 2 motifs, PxPFPW (B) and RRPGD (C), in the large subunit of HSV-2 ribonucleotide reductase.

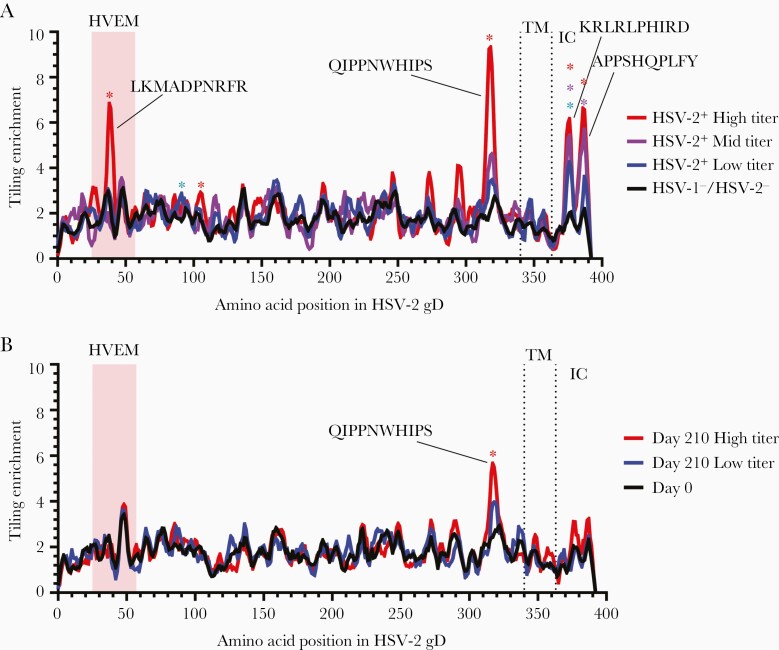

Since gD is a primary target of neutralizing antibodies [16], we applied tiling to identify gD epitopes associated with high and low HSV-2 neutralizing titers (Supplementary Figure 1). Four epitopes were targeted by antibodies and significantly enriched in HSV-2 naturally infected persons who had high titers of neutralizing antibody (Figure 4A). Two epitopes, KRLRLPHIRD and APPSHQPLFY at positions 372 and 384, respectively, were located in the intracellular domain of gD. Two other significantly enriched epitopes of gD were present in the herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) binding domain (LKMADPNRFR) and in the profusion domain (QIPPNWHIPS), both of which are targets of neutralizing antibodies [17–20]. In HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients, epitope QIPPNWHIPS in the pro-fusion domain was targeted by antibody and significantly enriched, but neither the HVEM binding domain epitope nor the intracellular domain epitopes were significantly enriched (Figure 4B). A monoclonal antibody, DL11, that neutralizes HSV-1 and HSV-2 entry via nectin-1, binds to a discontinuous epitope that maps to amino acids 38, 132, 140, and 222-224 on gD [21]; however, since the analytic methods used here (Identifying Motifs Using Next Generation Sequencing Experiments, PIWAS) are biased toward the identification and mapping of linear epitopes, such discontinuous and conformationally dependent epitopes in gD are unlikely to be detected.

Figure 4.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) gD epitope motifs recognized by antibodies in sera of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)/HSV-2–negative HSV529 vaccine recipients and HSV-2 naturally infected subjects. Tiling analysis of gD epitopes in sera from HSV-2+ naturally infected persons were separated into groups with high (n = 4), mid (n = 4), and low (n = 7) HSV-2 neutralizing titers compared to HSV-1–/HSV-2– controls (n = 48) (A), and HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients were separated into groups with high (n = 7) and low (n = 7) HSV-2 neutralizing titers at day 210 compared to day 0 samples (B). Epitopes determined to be significantly enriched are denoted by asterisks (false discovery rate <.01). Transmembrane (TM) and intracellular (IC) domains are labeled, and the herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) binding domain on gD is shaded.

HSV529 Induced Serum Antibody That Mediates ADCC

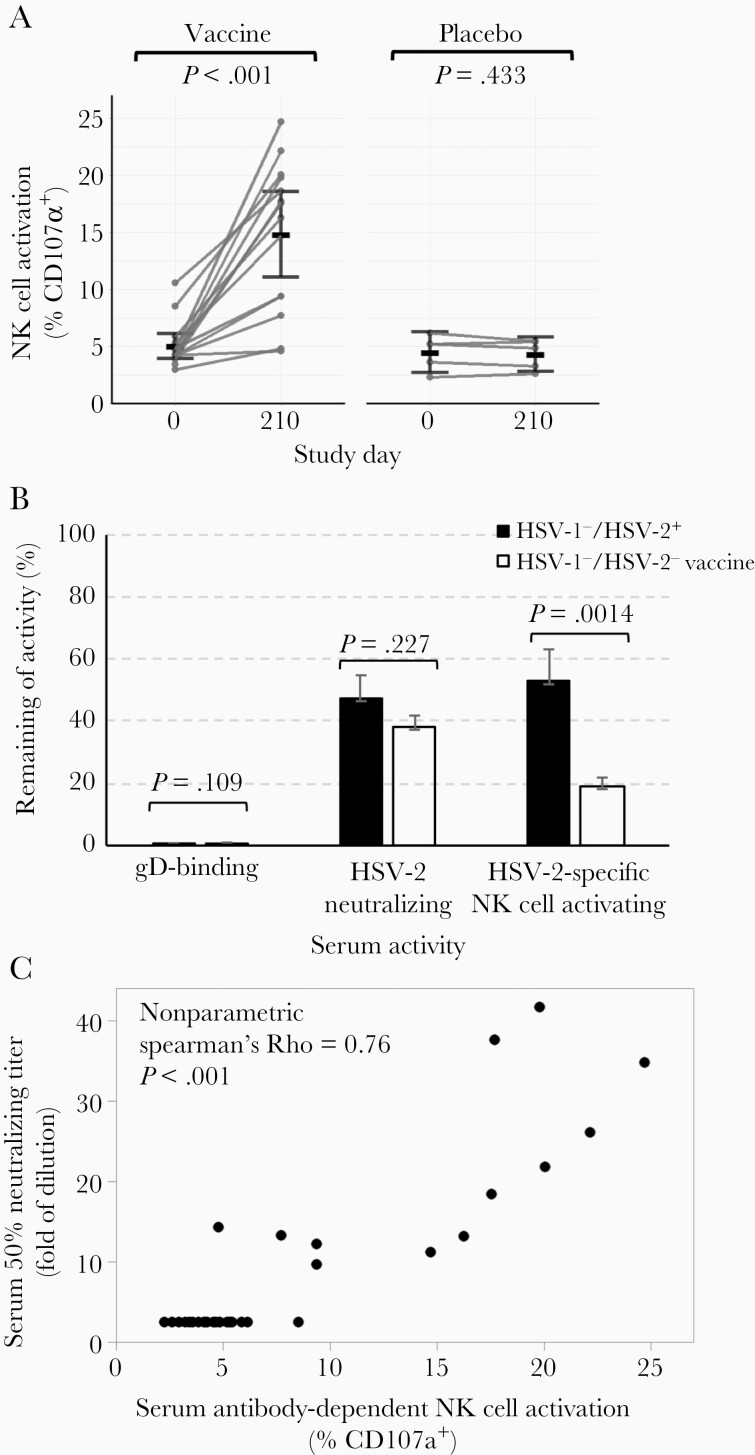

Sera from 19 HSV-1–/HSV-2– volunteers, 14 of whom received 3 doses of HSV529 and 5 who received placebo (saline), were assayed for antibody that mediated HSV-2–specific NK cell activation as a surrogate for ADCC. The group mean of the percentage of activated NK cells positive for surface CD107a in HSV529 vaccine recipients and placebo controls on day 0 was 5.0% and 4.5%, respectively. One month after the third dose of vaccine (day 210), 12 of 14 sera from HSV529 vaccine recipients had increased HSV-specific NK cell activating activity; the group mean of the percentage of activated NK cells in HSV529 vaccine recipients and placebo controls was 14.8 and 4.3%, respectively (P < .001 by t test; Figure 5A). Thus, vaccination with HSV529 induced antibodies capable of activating NK cells and thereby mediating ADCC. The mean level of ADCC activity in vaccinated HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects 1 month after the third dose of vaccine was about 7.8% that of the HSV-1–/HSV-2+ individuals (Supplementary Figure 2). Serum samples from 2 subjects had higher ADCC activity than the other subjects on day 0; this result was consistent with their higher level of HSV-2 neutralizing titer and/or gD antibody level than the other subjects despite their negative serology test for antibodies to HSV-1 gG and HSV-2 gG before vaccination. To determine the role of antibody to gD in ADCC in vaccine recipients, we depleted gD-binding antibody from the sera of these volunteers (Supplementary Figure 3). Depletion of gD-binding antibody reduced NK cell activation, a marker of ADCC, by 81% in vaccine recipients (Figure 5B). Depletion of gD antibody resulted in a significantly greater reduction of NK cell activation in vaccine recipients than in HSV-2 naturally infected persons (P = .0014).

Figure 5.

HSV529 vaccination induces serum antibody that mediates herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)–specific antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). A, Serum samples from herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)/HSV-2–negative subjects on days 0 and 210 were assayed for HSV-2–specific ADCC using a natural killer (NK) cell activation assay. NK cell activation was measured by detecting CD107a on the surface of NK92-CD16-GFP cells by fluorescence-activating cell sorting. The group mean of the percentage of NK cells positive for surface CD107a is shown. P values are based on paired t tests. B, The percentage of gD binding antibody, HSV-2 neutralizing antibody, and HSV-2–specific NK cell activating antibody after depletion of gD-binding antibody from sera of HSV-1–/HSV-2+ naturally infected persons and HSV-1–/HSV-2– persons vaccinated with HSV529. Error bars shows standard errors. C, Serum HSV-2–specific ADCC correlates positively with serum HSV-2 neutralizing titer. Sera from HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects on days 0 and 210 were assayed for HSV-2 neutralizing activity in Vero cells. The 50% inhibitory concentration was calculated by nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism. ADCC activity significantly correlates with neutralizing titers (nonparametric Spearman ρ = 0.76, P < .001).

Serum Anti–HSV-2 ADCC Activity Correlates Positively With Serum HSV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Titers

The ability of serum antibody to induce ADCC is dependent on antibody binding to viral antigens on the surface of infected cells and the affinity of the antibody to the Fc receptor on the surface of NK cells. We examined if there was a correlation between antibodies that mediate NK cell activation, a surrogate for ADCC, and those that mediate HSV-2 neutralizing activity in the sera of HSV529 vaccine recipients. All but 1 serum sample from vaccine recipients that tested positive for ADCC were also positive for HSV-2 neutralizing activity, and all but 1 serum sample that had virus neutralizing activity were positive for antibody that mediated ADCC. Analysis of all 29 sera from day 0 (prevaccination) and day 210 (1 month after the third dose of vaccine) of the HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients showed a positive correlation for ADCC activity and neutralizing antibody activity (ρ = 0.76, P < .001, nonparametric Spearman analysis; Figure 5C). These results suggest that neutralizing antibodies induced by HSV529 vaccination may be able to mediate ADCC.

To determine the contribution of gD antibody to neutralizing antibody in vaccine recipients, we depleted gD-binding antibody from the sera and found that neutralizing activity was reduced by 62% in vaccine recipients (Supplementary Figure 3; Figure 5B). Thus, using depletion experiments, we found that antibody to gD was more important for ADCC activity than for neutralizing activity. In contrast, antibody to gD was more important for HSV neutralizing activity than ADCC activity in mice vaccinated with HSVdl5-29 [22]. These differences may be due to differences in species or in assays used.

Intramuscular Vaccination With HSV529 Results in HSV-2 gD Antibodies in Cervicovaginal Fluid of Vaccine Recipients

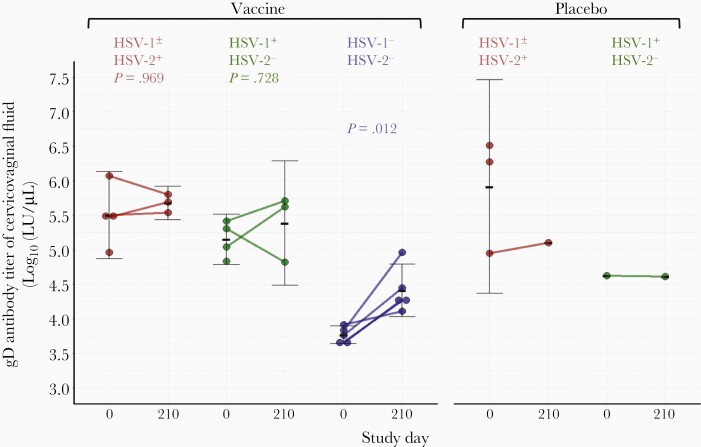

We investigated whether intramuscular vaccination with HSV529 results in detectable levels of antibodies to HSV-2 in cervicovaginal fluid. Cervicovaginal fluid and sera were collected on days 0 and 210 from 7 HSV-1±/HSV-2+ subjects (4 had received HSV529 and 3 received placebo), 5 HSV-1+/HSV-2– subjects (4 had received HSV529 and 1 received placebo), and 5 HSV-1–/HSV-2– volunteers (all had received HSV529). The samples were assayed for HSV-2 gD binding antibody using an HSV-2 gD luciferase-immunoprecipitation (LIPS) assay. HSV-1±/HSV-2+ vaccine recipients had similar levels of HSV-2 gD antibodies in cervicovaginal fluid on day 0 (prevaccination) and day 210 (1 month after the third dose of vaccine) with log10 geometric means of 5.5 and 5.7, respectively (P = .969, t test) (Figure 6). HSV-1+/HSV-2– subjects also had similar titers of cervicovaginal fluid gD antibodies on day 0 and day 210 (log10 geometric means of 5.2 and 5.4, respectively; P = 0.728, t test). In contrast, the log10 geometric mean gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid from HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients on day 0 and day 210 were 3.8 and 4.4, respectively (P = 0.012).

Figure 6.

Comparison of gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid before and after vaccination. Cervicovaginal fluid from each subject was collected using a vaginal cup before vaccination (study day 0) and 30 days after the third dose of vaccine (day 210) with HSV529. Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) gD-specific antibody was measured by luciferase immunoprecipitation assay. All 5 herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)/HSV-2–negative subjects had significantly increased gD antibody titers in their cervicovaginal fluid after vaccination, but no significant change was seen in subjects in the HSV-1+ or HSV-2+ group. P values are based on paired t tests.

The Level of HSV-2 gD-Binding Antibody in Cervicovaginal Fluid Is About One-Third That of the Level of Serum gD-Binding Antibody in HSV-1–/HSV-2– Subjects Receiving the HSV529 Vaccine

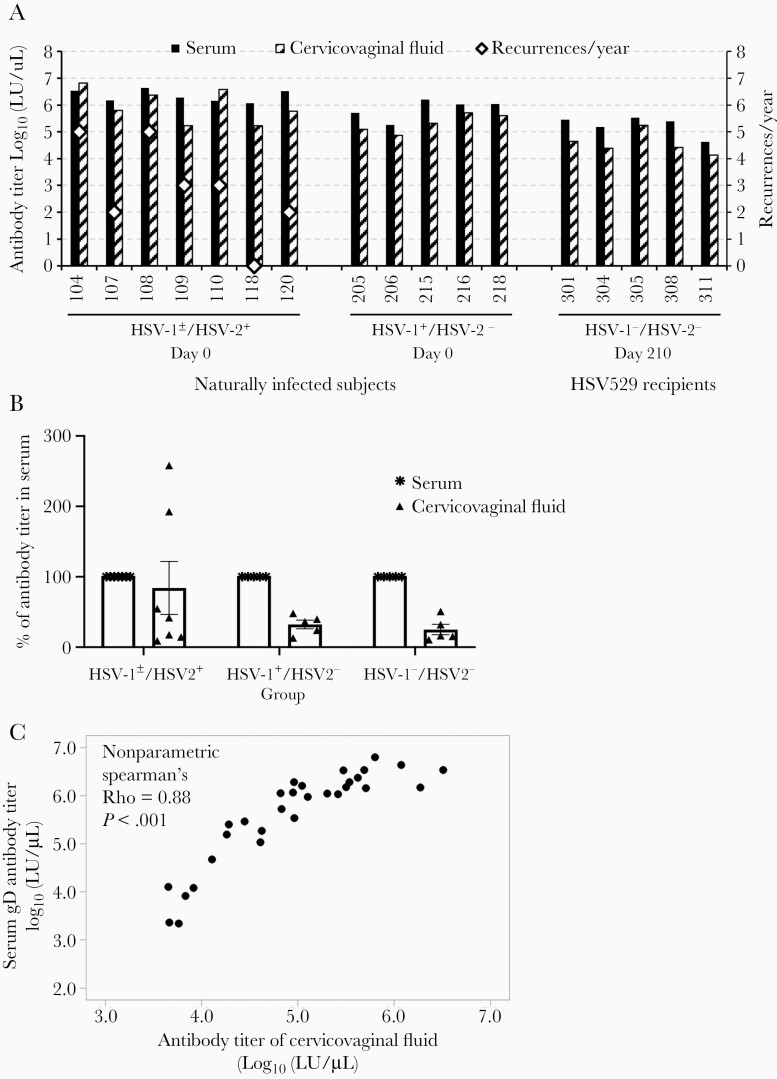

Cervicovaginal fluid collected from female subjects was found to be toxic to HSV-2 and to cells; therefore, we used the fluid to measure gD antibody with a LIPS assay. We evaluated whether there was a correlation of gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid with that in serum at day 210 (1 month after the third dose of vaccine) in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients. Levels of gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid and serum at day 0 (prevaccination) in HSV-1±/HSV-2+ and HSV-1+/HSV-2– subjects were used as a control for antibody levels in subjects naturally infected with HSV. In all but 2 of 17 subjects who were positive for gD antibody in cervicovaginal fluid, antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid were lower than those in sera; both subjects with higher titers of antibody in cervicovaginal fluid than in serum were in the HSV-1±/HSV-2+ group (Figure 7A). The percentage of group mean gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid relative to that in serum was 83%, 30%, and 26% for HSV-1±/HSV-2+, HSV-1+/HSV-2–, and HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects, respectively (Figure 7B). Thus, only the HSV-2+ group (who had had a vaginal infection with HSV-2) had HSV-2 gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid that approached those in their serum. Comparison of the gD antibody titer in cervicovaginal fluid to the titer in serum of the same subjects using data from samples in all 3 HSV-2 serogroups showed a strong positive correlation (ρ = .88, P < .001, nonparametric Spearman test; Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Correlation of the levels of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) gD antibody in cervicovaginal fluid and in serum. A, Comparison of gD antibody titer in cervicovaginal fluid vs in serum on day 210 for each herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)/HSV-2–negative subject. gD antibody titers on day 0 of HSV-1±/HSV-2+ or HSV-1+/HSV-2– subjects were included as naturally infected controls. Recurrences of HSV per year are shown in open diamonds; the 3 subjects with the highest gD antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid (104, 108, 110) also had the highest number of recurrences per year. B, Group mean gD antibody titer in cervicovaginal fluid expressed as the percentage of group mean gD antibody titer in serum (with the latter set at 100%). Error bars show standard errors. C, gD antibody titers of all available cervicovaginal fluid significantly correlate with their serum gD antibody titers (Spearman ρ = 0.88, P < .001).

Discussion

We recently reported the results of a phase 1 trial of a replication-defective HSV-2 vaccine, HSV529 [10]. Here we found that vaccination of HSV-1–/HSV-2– subjects with HSV529 induced serum antibodies significantly enriched for epitopes in HSV gG, RR1, UL26/UL26.5, gD, UL3, and UL51. Previous studies [12, 23] showed that HSV gG is a major target for antibodies in HSV-2 naturally infected persons. We detected antibodies to 2 epitopes of gG, PEHRGGPEEF and GAGDGEPPDD, which have been identified as portions of immunodominant motifs in HSV-2 recognized by most persons infected with HSV-2, but not HSV-1 [24, 25]. RR1 is the second most abundant protein in HSV529 preparations [26], which may explain why antibodies to RR1 were highly enriched in vaccine recipients. Vaccination with gG [27] or RR1 [28] induce protective immune responses to HSV-2 in animal models. In contrast to the limited number of proteins significantly targeted by antibodies in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients, persons naturally infected with HSV-2 produced antibodies targeting epitopes in more HSV proteins (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, several HSV proteins that were frequently targeted by antibodies in naturally infected persons and/or vaccine recipients (gD, gB, RR1, RS1, UL46, UL49) were among the top 10 HSV-2 proteins targeted by T cells (Supplementary Figure 4).

Antibody epitopes mapping to gD in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients were less enriched than those in HSV-2 naturally infected subjects using the SERA platform. In contrast, using an immunoprecipitation assay for gD, we previously found that the level of antibody to gD in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients was nearly as high as in HSV-2+ naturally infected subjects [10]. The difference in results using the SERA platform and the immunoprecipitation assay could be due to differences in analytic sensitivity or the dynamic range between the LIPS assay and SERA for gD, reduced detection of antibodies recognizing conformational epitopes with SERA, or that persons naturally infected with HSV-2 with frequent reactivation produce higher levels of antibodies that recognize linear epitopes compared with vaccine recipients. Antibodies to multiple other HSV proteins have been detected using protein arrays [29] or immunoprecipitation [30] compared with the SERA platform. Antibodies mapping to gB were also less enriched in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients than in HSV-2 naturally infected subjects using the SERA platform. An antibody response to gB was weakly detected in naturally infected subjects, but undetectable in vaccinated subjects, which may reflect the conformational dependence of many gB antibodies [31]. In addition, HSVdl5-29, which is genetically the same virus as the HSV529 vaccine, produces lower levels of gB than wild-type HSV-2 in cell culture [32].

We previously found that gD binding antibody and HSV-2 neutralizing antibody levels in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients peaked at day 210 [10]. Using the SERA platform, we found that antibodies to some motifs (eg, gG RGGPxE) peaked at day 210, while antibodies to other motifs had a variable time course; antibodies to 1 motif (RR1 RRPGD) peaked at day 60 and declined despite an additional dose of vaccine. The SERA platform identified an antibody epitope (gD LKMADPNRFR) in the HVEM binding site that contributes to virus neutralization [23, 24] in HSV-2 naturally infected persons, but not in HSV-1–/HSV-2– HSV529 vaccine recipients. Thus, the SERA platform may identify epitopes that are not well presented to the immune system in vaccine recipients and direct future modifications to vaccines.

HSV529 was previously shown to induce neutralizing antibody that can block HSV-2 entry [10]. Antibodies can also mediate ADCC, which can destroy virus-infected cells. We found that HSV-1–/HSV-2– recipients of the HSV529 vaccine developed serum antibody that mediated HSV-2-specific NK cell activation, a surrogate for ADCC. Sera from mice vaccinated with an HSV-2 gD-deletion mutant protected naive mice from HSV challenge; the sera had ADCC activity, but low HSV-2 neutralizing activity [33]. Low levels of ADCC were observed in HSV-1–/HSV-2– recipients of an HSV-2 gB and gD subunit vaccine in humans, and these low levels were postulated to be related to the poor efficacy of the vaccine in clinical trials [9]. Our observation that HSV-1–/HSV-2– recipients of the HSV529 vaccine developed antibody that mediated ADCC and that this activity correlated with serum neutralizing titers suggests that HSV529 may have advantages over subunit vaccines.

Local immunity, including production of HSV-specific antibody-producing B cells [34] and tissue resident T cells [35, 36], is thought to be important for protection against genital herpes infection and disease. We found that gD-binding antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid after the third dose of HSV529 vaccine increased in each of the 5 women in the HSV-1–/HSV-2– group tested, indicating that intramuscular injection of HSV529 resulted in HSV-2–specific antibody in genital secretions. The gD-binding antibody titer in cervicovaginal fluid from either HSV-1 naturally infected persons or from HSV-1–/HSV-2– vaccine recipients was about one-third the level of the antibody titer in serum. This suggests that the antibody in cervicovaginal fluid is transported from blood, as has been suggested previously [37]. Interestingly, 2 of the 5 cervicovaginal fluid samples from HSV-2 naturally infected subjects had higher gD-binding antibody titers in cervicovaginal fluid than in the serum. This was similar to the results of a previous study [38], which suggests that genital herpes may result in tissue resident B cells [39, 40] that produce antibody locally. The presence of HSV-1– and HSV-2–specific immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin A antibody in cervicovaginal fluid of HSV-1– and HSV-2–seropositive asymptomatic women was inversely associated with HSV-2 DNA asymptomatic shedding [41]. This suggests that HSV-specific antibodies in cervicovaginal fluid may protect against virus shedding. Thus, an HSV-2 vaccine that results in high, persistent titers of neutralizing antibody in cervicovaginal fluid might reduce or prevent HSV-2 genital infection. Even if such a vaccine did not prevent infection, if it reduced virus shedding it could change the epidemiology of HSV infection [42, 43].

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Presented in part: International Herpesvirus Workshops, Ghent, Belgium, 29 July 2017, and Knoxville, Tennessee, 23 July 2019.

Acknowledgments. We thank Lee-Jah Chang and Sanjay Phogat from Sanofi for supplying HSV529 vaccine and helping with design of the clinical trial.

Disclaimer. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Financial support. This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and a clinical trial agreement between NIAID and Sanofi Pasteur. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (contract number 75N91019D00024, task order number 75N91019F00130).

Potential conflicts of interest. J. B., J. R., W. A. H., J. R. S., J. C. S., and P. S. D. are employees and stockholders of Serimmune Inc. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Kohl S. Role of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in neonatal infection with herpes simplex virus. Rev Infect Dis 1991; 13:S950–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sullender WM, Miller JL, Yasukawa LL, et al. Humoral and cell-mediated immunity in neonates with herpes simplex virus infection. J Infect Dis 1987; 155:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yeager AS, Arvin AM, Urbani LJ, Kemp JA 3rd. Relationship of antibody to outcome in neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. Infect Immun 1980; 29:532–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prober CG, Sullender WM, Yasukawa LL, Au DS, Yeager AS, Arvin AM. Low risk of herpes simplex virus infections in neonates exposed to the virus at the time of vaginal delivery to mothers with recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med 1987; 316:240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belshe RB, Heineman TC, Bernstein DI, et al. Correlate of immune protection against HSV-1 genital disease in vaccinated women. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:828–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corey L, Langenberg AG, Ashley R, et al. Recombinant glycoprotein vaccine for the prevention of genital HSV-2 infection: 2 randomized controlled trials. Chiron HSV vaccine study Group. JAMA 1999; 282:331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stanberry LR, Spruance SL, Cunningham AL, et al. GlaxoSmithKline Herpes Vaccine Efficacy Study Group. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1652–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ashley R, Mertz GJ, Corey L. Detection of asymptomatic herpes simplex virus infections after vaccination. J Virol 1987; 61:264–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kohl S, Charlebois ED, Sigouroudinia M, et al. Limited antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibody response induced by a herpes simplex virus type 2 subunit vaccine. J Infect Dis 2000; 181:335–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dropulic LK, Oestreich MC, Pietz HL, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 1 study of a replication-defective herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 vaccine, HSV529, in adults with or without HSV infection. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:990–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang K, Goodman KN, Li DY, Raffeld M, Chavez M, Cohen JI. A herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) gD mutant impaired for neural tropism is superior to an HSV-2 gD subunit vaccine to protect animals from challenge with HSV-2. J Virol 2016; 90:562–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burbelo PD, Hoshino Y, Leahy H, et al. Serological diagnosis of human herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infections by luciferase immunoprecipitation system assay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2009; 16:366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang K, Tomaras GD, Jegaskanda S, et al. Monoclonal antibodies, derived from humans vaccinated with the RV144 HIV vaccine containing the HVEM binding domain of herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D, neutralize HSV infection, mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and protect mice from ocular challenge with HSV-1. J Virol 2017; 91:e00411-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamath K, Reifert J, Johnston T, et al. Antibody epitope repertoire analysis enables rapid antigen discovery and multiplex serology. Sci Rep 2020; 10:5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pan M, Wang X, Liao J, et al. Prediction and identification of potential immunodominant epitopes in glycoproteins B, C, E, G, and I of herpes simplex virus type 2. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:205313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cairns TM, Huang ZY, Whitbeck JC, et al. Dissection of the antibody response against herpes simplex virus glycoproteins in naturally infected humans. J Virol 2014; 88:12612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bosch DL, Geerligs HJ, Weijer WJ, Feijlbrief M, Welling GW, Welling-Wester S. Structural properties and reactivity of N-terminal synthetic peptides of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D by using antipeptide antibodies and group VII monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 1987; 61:3607–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Isola VJ, Eisenberg RJ, Siebert GR, Heilman CJ, Wilcox WC, Cohen GH. Fine mapping of antigenic site II of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D. J Virol 1989; 63:2325–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nicola AV, Ponce de Leon M, Xu R, et al. Monoclonal antibodies to distinct sites on herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D block HSV binding to HVEM. J Virol 1998; 72:3595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strynadka NC, Redmond MJ, Parker JM, Scraba DG, Hodges RS. Use of synthetic peptides to map the antigenic determinants of glycoprotein D of herpes simplex virus. J Virol 1988; 62:3474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cairns TM, Ditto NT, Lou H, et al. Global sensing of the antigenic structure of herpes simplex virus gD using high-throughput array-based SPR imaging. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burn Aschner C, Knipe DM, Herold BC. Model of vaccine efficacy against HSV-2 superinfection of HSV-1 seropositive mice demonstrates protection by antibodies mediating cellular cytotoxicity. NPJ Vaccines 2020; 5:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee FK, Coleman RM, Pereira L, Bailey PD, Tatsuno M, Nahmias AJ. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 2-specific antibody with glycoprotein G. J Clin Microbiol 1985; 22:641–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grabowska A, Jameson C, Laing P, et al. Identification of type-specific domains within glycoprotein G of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) recognized by the majority of patients infected with HSV-2, but not by those infected with HSV-1. J Gen Virol 1999; 80:1789–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marsden HS, MacAulay K, Murray J, Smith IW. Identification of an immunodominant sequential epitope in glycoprotein G of herpes simplex virus type 2 that is useful for serotype-specific diagnosis. J Med Virol 1998; 56:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. James DA, Fradin MJ, Pedyczak A, Carpick BW. Detection of residual proteins UL5 and UL29 using a targeted proteomics approach in HSV529, a replication-deficient HSV-2 vaccine candidate. J Pharm Sci 2018; 107:3022–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Görander S, Ekblad M, Bergström T, Liljeqvist JÅ. Anti-glycoprotein g antibodies of herpes simplex virus 2 contribute to complete protection after vaccination in mice and induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-mediated cytolysis. Viruses 2014; 6:4358–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Srivastava R, Roy S, Coulon PG, et al. Therapeutic mucosal vaccination of herpes simplex virus 2-infected guinea pigs with ribonucleotide reductase 2 (RR2) protein boosts antiviral neutralizing antibodies and local tissue-resident CD4(+) and CD8(+) T(RM) cells associated with protection against recurrent genital herpes. J Virol 2019; 93:e02309-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Chun S, Chentoufi AA, et al. Discovery of potential diagnostic and vaccine antigens in herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 by proteome-wide antibody profiling. J Virol 2012; 86:4328–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murányiová M, Rajcáni J, Krivjanská M, Matis J, Pogády J. Immunoprecipitation of herpes simplex virus polypeptides with human sera is related to their ELISA titre. Acta Virol 1991; 35:252–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chapsal JM, Pereira L. Characterization of epitopes on native and denatured forms of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B. Virology 1988; 164:427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reszka NJ, Dudek T, Knipe DM. Construction and properties of a herpes simplex virus 2 dl5-29 vaccine candidate strain encoding an HSV-1 virion host shutoff protein. Vaccine 2010; 28:2754–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Petro C, Gonzalez PA, Cheshenko N, et al. Herpes simplex type 2 virus deleted in glycoprotein D protects against vaginal, skin and neural disease. eLife 2015; 4:e06054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oh JE, Iijima N, Song E, et al. Migrant memory B cells secrete luminal antibody in the vagina. Nature 2019; 571:122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Çuburu N, Wang K, Goodman KN, et al. Topical herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) vaccination with human papillomavirus vectors expressing gB/gD ectodomains induces genital-tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells and reduces genital disease and viral shedding after HSV-2 challenge. J Virol 2015; 89:83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shin H, Iwasaki A. A vaccine strategy that protects against genital herpes by establishing local memory T cells. Nature 2012; 491:463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Z, Palaniyandi S, Zeng R, Tuo W, Roopenian DC, Zhu X. Transfer of IgG in the female genital tract by MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) confers protective immunity to vaginal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:4388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ashley RL, Crisostomo FM, Doss M, et al. Cervical antibody responses to a herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein subunit vaccine. J Infect Dis 1998; 178:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson RM, Yu H, Strank NO, Karunakaran K, Zhu Y, Brunham RC. B Cell presentation of chlamydia antigen selects out protective CD4γ13 T cells: implications for genital tract tissue-resident memory lymphocyte clusters. Infect Immun 2018; 86:e00614– 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Machado-Santos J, Saji E, Tröscher AR, et al. The compartmentalized inflammatory response in the multiple sclerosis brain is composed of tissue-resident CD8+ T lymphocytes and B cells. Brain 2018; 141:2066–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mbopi-Kéou FX, Bélec L, Dalessio J, et al. Cervicovaginal neutralizing antibodies to herpes simplex virus (HSV) in women seropositive for HSV Types 1 and 2. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2003; 10:388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alsallaq RA, Schiffer JT, Longini IM Jr, Wald A, Corey L, Abu-Raddad LJ. Population level impact of an imperfect prophylactic vaccine for herpes simplex virus-2. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schwartz EJ, Bodine EN, Blower S. Effectiveness and efficiency of imperfect therapeutic HSV-2 vaccines. Hum Vaccin 2007; 3:231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.