Abstract

Adipose tissue, once thought to be an inert receptacle for energy storage, is now recognized as a complex tissue with multiple resident cell populations that actively collaborate in response to diverse local and systemic metabolic, thermal, and inflammatory signals. A key participant in adipose tissue homeostasis that has only recently captured broad scientific attention is the lymphatic vasculature. The lymphatic system’s role in lipid trafficking and mediating inflammation makes it a natural partner in regulating adipose tissue, and evidence supporting a bidirectional relationship between lymphatics and adipose tissue has accumulated in recent years. Obesity is now understood to impair lymphatic function, whereas altered lymphatic function results in aberrant adipose tissue deposition, though the molecular mechanisms governing these phenomena have yet to be fully elucidated. We will review our current understanding of the relationship between adipose tissue and the lymphatic system here, focusing on known mechanisms of lymphatic-adipose crosstalk.

Keywords: obesity, adipose tissue, lymphatic endothelium, lymphedema, lipedema

Lymphatic Anatomy and Function

Both adipose tissue and lymphatics were, for centuries, primarily distinguished by their respective roles in lipid metabolism. Before the discovery of adipose-derived factors such as leptin in 1994 (1), fat was seen principally as a passive storage site for nutritional lipids. Likewise, ancient Greek anatomists described the lipid-containing milky lymphatic vessels (2), whereas connection to the gut was observed and a role in uptake of dietary nutrients suspected as early as the 17th century (3). The late 17th and 18th centuries saw the discovery and description of nonmesenteric lymphatic vessels (LVs) and their role in fluid absorption (4), whereas in the 19th and 20th centuries, LV participation in immune cell trafficking and cancer metastasis was recognized (5). Only recently, however, have LVs been viewed as more than hollow conduits for dietary lipid uptake and systemic lymph transport; LVs are now known to be active participants in lipid metabolism, immunity, cancer biology, and hypertension, among other physiological and pathological processes (6).

LVs were initially difficult to study given their narrow diameter, nearly translucent walls, and often colorless contents, and some early anatomists attempted to inject them with wax or other substances to better visualize their course (7). We now know that the lymphatic system is a closed, unidirectional network of vessels that drains the tissue interstitium and carries excess fluid, solutes, and cells to the venous vascular system. LVs are present in all vascularized tissues except for bone marrow and the central nervous system (8). In the latter case, interstitial solutes are cleared from the brain parenchyma through the recently described glymphatic system, which runs along the perivenous space to connect the subarachnoid space to the brain parenchyma and drains into to the cervical lymphatic system (9). There is also a proposed relationship between the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics that has yet to be fully characterized (10). Because of its pervasive presence in most organs and tissues, lymphatic system homeostasis and its role in disease has gathered increasing interest across multiple disciplines (6, 11).

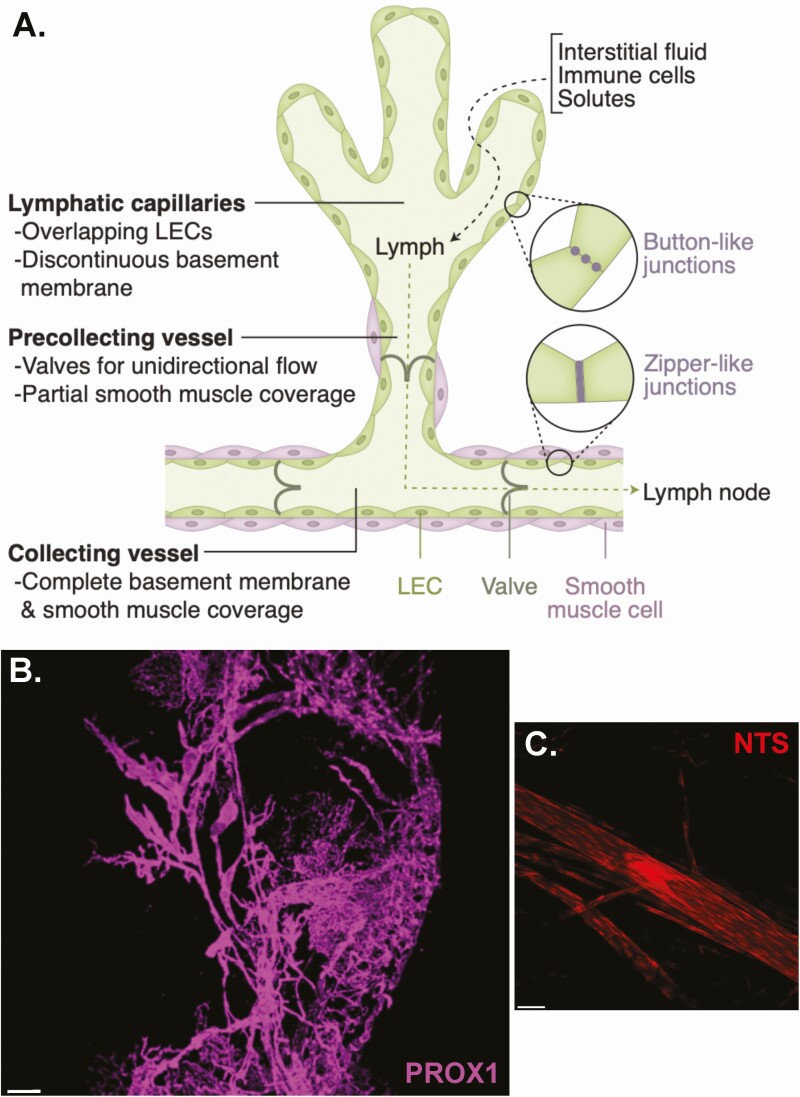

Anatomically, LVs initiate within the tissue as capillaries tethered by connective filaments to the surrounding tissue (12) which then progressively merge into precollecting vessels followed by secondary collecting vessels (Fig. 1A) and ultimately into the thoracic duct, which empties into the venous system at the junction of the left subclavian and internal jugular veins, or into the right lymphatic trunk in the case of lymph from the right upper arm, thorax, and head (13). As vessels merge, their diameter increases and they are enveloped by a continuous basement membrane and a layer of smooth muscle, which, in concert with contraction of surrounding smooth muscle and local arterial pulsations, propel lymph forward, whereas bileaflet valves prevent backflow (14). The lumen of LVs is lined with a layer of lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), which in capillaries form discontinuous, discrete “button-like” junctions to allow for entry of fluid, macromolecules, and leukocytes between them (15). When the vessel is filled, it is transiently sealed by overlapping LECs because the intravascular pressure exceeds that of the surrounding interstitium (8). Endothelial junctions become more continuous and “zipper-like” in the collecting vessels to prevent paracellular leakage of solutes and fluid back into the surrounding tissue (15). Collecting vessels may become more permeable in the setting of perinodal adipose tissue inflammation (16).

Figure 1.

Lymphatic system organization and anatomy. (A) Schematic of major lymphatic anatomic and functional characteristics. (B) Confocal image of a perigonadal fat pad whole mount dissected from a mouse in which lymphatic vasculature was labeled by Prox1-CreER-driven tdTomato expression (purple). Scale bar: 300 μm. (C) A lymphatic vessel and valve labeled by NTS-Cre-driven tdTomato (red) in a murine mesenteric fat whole mount. Scale bar: 50 μm. LEC, lymphatic endothelial cell.

There is significant heterogeneity within LEC subtypes that reflects their function within the lymphatic system as well as likely tissue-specific specializations, reviewed in detail previously (17). Both lymphatic capillaries and collecting vessels express certain master lymphatic transcriptional regulators such as Prospero homeobox 1 (PROX1) and signaling receptors like vascular endothelial growth factor 3 (VEGFR3) and neuropilin 2, which bind VEGF-C to maintain LEC identity and growth (18). Lymphatic capillaries express high levels of the hyaluronan receptor LYVE1 (19) and chemokine CCL21 relative to collecting vessels, which allows for the recruitment of CCR7-positive dendritic cells into the lymphatic system (20). Lymphatic valves also have unique transcriptional profiles, including expression of forkhead box protein C2 (FOXC2), a transcription factor required for the formation of collecting lymphatic vessels and valves (21). The recent discovery that Foxo1 deletion in mice results in stimulation of de novo lymphatic valve formation (22) has provided additional insight into the mechanism of LEC specialization. Single-cell RNA-sequencing studies of murine auricular (23) and inguinal, axillary, and brachial (24) lymph nodes have identified multiple LEC subtypes with distinct markers and anatomic niches, and have described LEC type-specific responses to inflammation. Single-cell RNA sequencing has also been performed on human axillary and parotic lymph nodes (25), demonstrating multiple subtypes of LECs.

In addition to interstitial fluid homeostasis, several lymphatic structures are involved in immune surveillance and response, including lymph nodes, the spleen, and Peyer patches in the small intestine. LVs are critical for the trafficking of immune cells out of the tissue to lymph nodes (26). LVs directly participate in adaptive immunity via the ability of LECs to present antigens to T cells (27), for example, and are critical to the coordination of the immune response, as reviewed in detail elsewhere (28). The role of lymphatics in adipose tissue immune cell trafficking is complex and modulated by obesity. For example, adipocyte-specific VEGF-D overexpression promotes adipose tissue lymphangiogenesis, but with different consequences in lean and obese mice. In lean mice, VEGF-D overexpression causes increased local macrophage accumulation and fibrosis (29), likely in part because of the chemoattractant properties of VEGF-D (30), with no impact on systemic glucose homeostasis. This contrasts with VEGF-D overexpression in obesity models, in which amplified lymphangiogenesis results in reduced adipose tissue inflammation and an improvement in systemic glucose metabolism (31). Notably, inflamed macrophages can also produce VEGF-C/D to promote lymphangiogenesis and antigen clearance (32), underscoring the relationship between immune cells and lymphatic function.

Intestinal lymphatics and mesenteric lymph nodes process environmental antigens while adding another critical function: absorption of dietary fat. In the intestine, lymphatic capillaries are called lacteals and are present exclusively in intestinal villi, where they are responsible for absorption of chylomicrons and fat-soluble vitamins (33). The role of the lymphatic system in lipid uptake and transport is reviewed in detail elsewhere (34, 35) and is not the focus of this review, but clearly has relevance to adipocyte biology via regulation of systemic lipid metabolism.

Lymphatic Differentiation and Development

Most LECs have a venous origin (36), except for cardiac LECs, which may derive from a hematopoietic source (37). Notwithstanding their site of origin, LECs are distinct from blood vascular endothelial cells and are regulated by different signals (38). Discovery that expression of Prox1 is required for the development of the lymphatic system in mice revealed a key regulator of lymphatic differentiation as well as provided a transcriptional marker that distinguishes LECs from vascular endothelial cells (39). Overexpression of PROX1 in human adipose derived stem cells promotes a LEC phenotype, capable of forming tubes and junctions typical of LVs (40). Interestingly, PROX1 expression has been reported in human adipocytes, particularly in the omentum (41). In human adipose tissue, LVs are significantly more abundant in visceral depots compared with subcutaneous (42), and accordingly, PROX1 is more highly expressed in human omental adipose compared with subcutaneous (41). Similarly, confocal imaging demonstrates a robust network of lymphatics in mouse perigonadal visceral fat (Fig. 1B).

PROX-1-VEGFR3 signaling is required to maintain a lymphatic progenitor identity during embryonic development (43), and VEGFR3 ligand VEGF-C is an important lymphatic growth factor that can promote LEC hyperplasia (44), lymph node lymphangiogenesis (45), and even ectopic LV formation in bone (46). Factors such as ephrin-B2 (47) and GATA2 (48) potentiate VEGF-C signaling and expression, respectively.

Lipid metabolism plays a unique role in LEC differentiation and LV growth. Fatty acid β-oxidation is required for lymphatic marker expression, and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A, a rate-limiting enzyme for fatty acid oxidation, is a target gene of PROX1 and essential for lymphatic development (49). The fatty acid transporter CD36 also plays a key role in LEC function; CD36 knockout mice have shorter lacteals and disrupted tight junctions, and LEC-specific CD36 deletion results in leaky gut lymphatics, obesity, and adipose inflammation (50). Furthermore, lymph nodes are surrounded by adipose tissue, and peri-lymph node adipose tissue has a distinct lipid composition compared to adipose more distant from the node (51), suggesting a possible axis of interaction between lymphatics and adipocyte lipid metabolism.

Following a proliferative phase during development, LECs become quiescent, a state that extends into adulthood under homeostatic conditions (11). Reactivation of LV growth is mostly associated with pathological states such as inflammatory diseases (32). It is unclear whether LECs in different organs have the same proliferative potential or rely on the same signals, though VEGF-C overexpression is sufficient to stimulate lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in multiple tissues, including the skin (52) and skeletal muscle (53), and VEGF-D overexpression in adipocytes stimulates local lymphangiogenesis in brown and white adipose tissue (29).

Lymphatic Function Is Impaired in Obesity

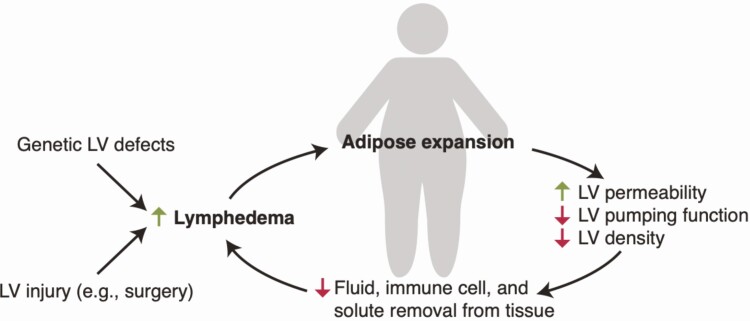

Because of the complexity and plasticity of adipose tissue, metabolic overload and obesity ensnares multiple cell types, including adipocytes (54), macrophages (55), vascular endothelium (56), and mesothelium (57), in a pathological cycle of dysfunction and inflammation. LVs have been implicated as collateral damage in obesity because their function is impaired in both rodent and human obesity. Obesity reduces lymphatic fluid transport and the number and size of lymph nodes and LVs present in the tissue (58), and therefore impairs the drainage of macromolecules from adipose tissue (59) (Fig. 2). This in turn spurs the accumulation of interstitial fluid (lymphedema) (60). Obesity also impacts LV morphology and size (61) and results in decreased contractility (61) and increased permeability, which has been linked to increased inflammation (60) and a subsequent decrease in factors that regulate lymphatic proliferation and function, such as VEGFR3 and PROX-1 (62). Mesenteric lymphatics also exhibit aberrant remodeling in obesity due to pathological VEGF-C signaling, resulting in more branched, disorganized, and tortuous LVs that are associated with lymph leakage into the surrounding visceral fat (63). Mechanical effects of adipocyte hypertrophy on lymphatic flow have been suggested to be a cause of obesity-associated lymphatic dysfunction, though the functional effects of obesity are not limited to LVs within the adipose tissue itself but manifest throughout the body (61).

Figure 2.

The bidirectional and cyclical relationship between lymphatics and adipose tissue. Obesity leads to defects in lymphatic structure and function and an increased risk of lymphedema, while lymphedema leads to abnormal adipose expansion. LV, lymphatic vessel.

Obesity-related lymphatic dysfunction is at least partially reversible. Weight loss (64) and inhibition of T cell-mediated inflammation (65) both improve lymphatic function, and treatment with the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib prevented mesenteric lymphatic remodeling and reduced local VEGF-C release in a mouse model of obesity (63). Because of these functional effects, obesity increases the risk of developing spontaneous lymphedema (66), which is localized edema that results from impaired interstitial fluid clearance from tissues because of lymphatic incompetence. Obese patients undergoing surgical lymph node dissection are also at increased risk for postoperative lymphedema compared with lean patients (67, 68).

Precise mechanisms of lymphatic dysfunction in obesity remain elusive, though direct adipocyte-LEC interactions, as discussed later, may play a role. There is also evidence that local adipose inflammation may mediate lymphatic pathology in obesity. For example, cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 (69), interferon-γ (70, 71), interferon-α (70), and TGF-β (72) inhibit lymphangiogenesis, and depletion of T cells in vivo improves lymph node vessel formation and dendritic cell recruitment (73). Peri-lymphatic accumulation of inflammatory cells is known to occur in obesity, and treatment with the T-cell inhibitor tacrolimus improves lymphatic pumping function and clearance (65). Interestingly, perilymphatic inflammation is not restricted to intra-adipose lymphatics, but occurs systemically, for example in the ear, trachea, and hindlimb lymphatics in a diet-induced obesity mouse model (65). Obese mice have heightened dermatitis responses to inflammatory skin stimuli as well, which was improved with VEGF-C injection (74). Perilymphatic inflammation also exposes LECs to long-chain free fatty acids in obesity, which increases LEC apoptosis and decreases VEGFR-3 signaling (62).

Lymphatic Dysfunction Promotes Adipose Deposition and Inflammation

The most widely recognized clinical consequence of lymphatic dysfunction is lymphedema. Lymphedema can be due to a primary lymphatic defect, such as in Milroy disease that results from inactivation of the VEGFR-3 gene (75), or secondary to lymphatic vessel disruption, such as following lymph node resection. Lymphedema has a significant clinical footprint, affecting millions worldwide, including at least 20% of women with breast cancer undergoing axillary-lymph node dissections (76), and more than one-third of women undergoing pelvic lymphadenectomy for gynecologic cancer (77). In addition to damaging body image and decreasing quality of life (78), lymphedema and the associated adipose expansion are associated with discomfort and functional impairment, recurrent bacterial and fungal infections, ulcerations, and, in rare cases, cutaneous angiosarcoma (79).

Lymphedema causes significant adipose tissue deposition, predominantly in the subcutaneous compartment (80), though there is subfascial muscle lipid accumulation as well (81). Lymphatic participation in adipogenesis has been suspected for decades (82), supported by early findings that mesenteric lymph supplementation enhances rabbit preadipocyte differentiation in culture (83), later replicated with mouse (84) and human (85) lymphatic fluid and preadipocytes. Adipose-derived stem cells from lymphedematous extremities also demonstrated an enhanced adipogenic potential (86), though this was not replicated in a recent study (85). Malformation of cutaneous lymphatics results in adipose accumulation (87) and idiopathic lymphedema results in dermal lipid accumulation (88). Lymph stasis in a mouse tail lymphedema model results in increased size and number of lipid droplets (89), though the effect of lymphedema on adipocyte size remains unclear. In humans, adipocytes were found to be larger in lymphedematous limbs than in control limbs from the same patient (90), though other studies using unmatched samples have shown conflicting findings regarding adipocyte size (85, 91).

Mouse secondary lymphedema models have indicated that lymphatic fluid accumulation results in induction of the adipogenic program as measured by C/EBPα and PPAR-γ expression (92). In a detailed study of lymphedema-associated adipose tissue in breast cancer survivors, lymphedematous adipose tissue demonstrated upregulation of leptin gene expression as well as altered adipogenic and lipolytic enzymes, though the directionality of those changes was mixed (85). Lymphedema-associated adipose explants and isolated adipocytes had higher isoproterenol-stimulated lipolysis than healthy controls (85). There was also evidence of increased inflammation and fibrosis in lymphedema samples, in concordance with mouse studies (89).

Although several studies have shown that lymph can stimulate adipocyte differentiation, it is important to emphasize that increased adipogenesis is a result—not a cause—of obesity. The first law of thermodynamics stipulates that the change in internal energy of a system, such as an organism, must equal the sum of the energy inputs minus the outputs, and obesity results from a net positive energy balance (ie, the input energy is higher than the output energy) (93) and not from the differentiation of new fat cells. Put more simply, the calories in stored triglycerides must come from somewhere—the body cannot create mass or energy simply by converting 1 cell type (eg, a preadipocyte) to another (eg, an adipocyte). In the setting of overnutrition, adipogenesis is a metabolically advantageous response to a positive energy balance because it allows for fatty acids to be stored safely without causing lipotoxicity (94). Therefore, the effect of lymph on adipose deposition must rely on increased food intake or absorption, reduced energy expenditure, or both. Claims that adipogenesis alone is the cause of obesity in lymphatic dysfunction therefore violate the laws of thermodynamics and must be rejected.

A less well-characterized lymphatic pathology known as lipedema presents with symmetrical and painful fat deposition in a gynoid distribution (95). Because of female predominance and onset with puberty, an estrogen-mediated mechanism has been hypothesized (96), but little definitive evidence has emerged as to the pathophysiology of this condition. Lipedema is characterized by reduced lymph flow (97) and enlarged lymphatic vessels (98) on lymphangiography. Increased serum VEGF-C levels have been noted in lipedema patients compared with body mass index-matched controls, along with higher VEGFR-3 expression in adipose tissue biopsies (99). Descriptions of lymphatic anatomy in lipedema have been inconsistent, ranging from normal (99), to an increase in lymphatic vessel area (100), to the presence of lymphatic microaneurysms (101). Consistently, lipedema-associated fat is associated with exaggerated macrophage infiltration (99, 100, 102). Lipedema-derived adipose stem cells have been demonstrated to exhibit reduced lipid accumulation and adipocyte differentiation in response to in vitro adipogenic stimulation (103, 104), though this finding has recently been called into question because a 3-dimensional spheroid system enabled normal differentiation of these precursors (105). It remains unclear how adipocytes associated with lymphedema and lipedema may be different from the fat expansion and dysfunction seen in standard obesity. Human studies may also be confounded by the underlying body mass index of the patient, as exemplified in 1 analysis, in which differences in lymphatic vessel area were apparent only in obese patients, whereas differences in adipocyte size were only apparent in lean patients (100).

A genetic etiology of lipedema has been suspected based on a self-reported family history of the disease in up to 60% of female patients (106). Molecular mechanisms that underlie lipedema have also been hypothesized based on genetic syndromes in which lipedema is a clinical feature. Interestingly, many of these syndromes have connective tissue components, including Williams syndrome, which results from deletion of the elastin gene (among others) (107), and cutis laxa type III, which results from mutations in the ALDH18A1 gene that encodes the enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of glutamate to Δ 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate (108). Additional genetic syndromes associated with lipedema-like adipose deposition have been reviewed in detail elsewhere (109). Genetic testing schema for patients with lipedema have been proposed to assess for related genetic syndromes or overlapping adipose pathologies (109), though this is not commonly pursued in practice. Additionally, an association of lipedema with aortic stiffness has been reported (110), but no mechanistic link has been established.

Transgenic mouse models have also been used to study primary lymphatic diseases, and these models often are notable for adipose tissue dysfunction. Prox1 haploinsufficiency causes adult-onset obesity in mice (84, 111), and LEC-specific CD36 deletion in mice results in disruption of lacteal junctions and visceral obesity, adipose inflammation, and glucose intolerance (50). Although both of these models cause visceral obesity, mice that are haploinsufficient for Vegfr3 have hypoplastic cutaneous lymphatic vessels and demonstrate subcutaneous adipose deposition (112). K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice, which express a soluble VEGFR-3-Ig protein to trap VEGF-C/D under the control of the keratin 14 promoter, lack dermal lymphatic capillaries and exhibit some elements of lymphedema, including subcutaneous adipocyte deposition (113); these mice are protected from obesity and exhibit slightly smaller adipocytes than seen in wild-type mice (114).

An additional clue linking LEC development to adipose tissue function was noted in the study of FOXC2 because inactivating mutations in this gene lead to hereditary lymphedema, whereas a single nucleotide polymorphism in its putative promoter region has been associated with obesity but not type 2 diabetes in both Pima (115) and Scandinavian (116) subjects. Mice overexpressing FOXC2 in adipocytes are protected from visceral obesity (117) and intramuscular fatty acyl coenzyme A accumulation and insulin resistance (118), though these studies did not examine changes in lymphatic function and a direct connection between FOXC2 regulation of lymphatics and adipose tissue has yet to be defined.

There Is an Axis of Communication Between Adipocytes and LECs

Although evidence exists for a relationship between LV and adipose tissue, specific mechanisms of interaction have remained elusive until recently. LECs express receptors for many adipokines, suggesting that direct communication between mature adipocytes and LVs may be mediated via paracrine or endocrine means (Fig. 3). LECs express the leptin receptor, and treatment with high-dose leptin has been reported to negatively impact lymphatic tube formation in culture (119). This contrasts with the literature that describes leptin action on the vascular endothelium, where leptin promotes angiogenesis (120), potentially via increased expression of MMP-2/9 and TIMP-1/2 (121), as well as FGF-2 and VEGF (122). Leptin also increases vascular permeability (122), and its deletion induces neointima formation (123). Much less is known about leptin’s role in regulating the lymphatic vasculature.

Figure 3.

The lymphatic endothelial cell-adipocyte axis. Specific mechanisms of adipocyte-lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) crosstalk have recently been described. Neurotensin (NTS) is secreted by LECs and can act via NTS receptor 2 (NTSR2) on brown adipocytes to suppress extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling and reduce thermogenesis. In addition to its direct action on adipocytes via β-adrenergic receptors (ADRBs), norepinephrine also stimulates thermogenesis by agonism of the α2-adrenergic receptor (ADRA2) on LECs, which in turn suppresses NTS production, thereby releasing thermogenic components from NTS inhibition. Specific adipocyte-derived factors that affect LEC function include leptin and adiponectin, which have been demonstrated to inhibit and promote lymphangiogenesis, respectively. Additional mediators of the LEC-adipocyte axis are likely to be important in further defining the relationship between adipose tissue and lymphatic dysfunction.

Adiponectin, another secreted product of differentiated adipocytes, stimulates the differentiation of human LECs and promotes tube formation, in addition to mediating LEC nitric oxide production (124). Adiponectin’s role in vascular endothelial function is disputed, and may differ from its role in LECs because adiponectin has been shown both to decrease VEGF-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation and endothelial cell proliferation and migration in a human retinal vascular endothelial model (125) as well as promote AMPK phosphorylation and simulate human umbilical vein endothelial cell differentiation and migration (126).

Recently, another axis of LEC-adipocyte interaction was described, linking brown adipose thermogenesis to neurotensin (NTS) produced by LECs (127). In this study, single-cell RNA-sequencing of mouse and human fat revealed a discrete LEC population present in all adipose depots and transcriptionally distinct from vascular endothelial cells. Nts is a specific LEC marker, and NTS-Cre-driven fluorescent labeling is seen in adipose tissue LVs and valves (Fig. 1C). Nts is most highly expressed in LECs of thermogenic brown fat, followed by subcutaneous and perigonadal visceral white adipose tissue, respectively. Nts expression is suppressed by cold and norepinephrine via α2-adrenergic signaling, indicating coordination between the sympathetic nervous system, LECs, and brown adipocytes in regulating thermogenesis. LEC-released NTS was responsible for the antithermogenic actions of NTS, and neurotensin receptor 2 was shown to mediate the dominant effects of NTS on adipocyte metabolism.

In brown adipocytes, NTS activates ERK1/ERK2, which suppresses Ucp1 expression, thereby inhibiting thermogenesis. Treatment of mice with NTRC-824, a small molecule inhibitor specific for neurotensin receptor 2, induced thermogenesis and prevented further weight gain in a diet-induced obesity model, demonstrating impressive systemic consequences for the sympathetic-LEC-adipocyte axis. Although LVs had been previously shown to respond to both α- and β-adrenergic signals (128), and tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing sympathetic nerve fibers are present in lymph nodes (129), this study was the first to indicate direct coordination between these systems and adipocyte function, and strongly suggests that LECs are active participants in adipose metabolism, likely via multiple mechanisms.

Conclusions, Challenges, and Future Directions

The relationship between the lymphatic system and adipose tissue has been increasingly recognized as bidirectional, dynamic, and consequential, though underlying mechanisms have only recently been investigated in detail. Recent findings that LECs express adipokine receptors and that adipocytes respond to LEC-secreted factors are exciting indications that lymphatics are active participants in adipose tissue biology and that modulating this relationship may have implications for human health.

A challenge in studying LECs has been the lack of a specific genetic marker to drive Cre-mediated lineage tracing and gene targeting. There are limitations in cell-type specificity with many LEC models because LECs have diverse developmental origins, and identifying a single genetic driver is difficult (17). For example, as previously discussed, Lyve1 is highly expressed in lymphatic capillaries, but less so in collecting ducts (19), while also being expressed in some macrophage populations (130). Prox1 reliably marks LECs and has a functional role in lymphangiogenesis (131), but is also expressed in developing cardiomyocytes (132), neural stem cells (133), lens cells (134), and hepatocytes (135). Though using a tamoxifen-inducible Prox1-CreER prevents recombination in cell types that only express Prox1 during development, nonspecificity in the adult mouse remains a concern. A promising new Cre model driven by Pdpn (136) is another LEC-specific model that has been developed but is less widely used. Intersectional genetic models using combinations of Cre and Dre drivers may enable more specific targeting strategies, including one designed to target LECs by crossing the Cdh5-Dre with a Prox1-rox-stop-rox-CreER allele (137). This method is comprehensively labeled Prox1 + LECs while avoiding recombination in other tissues, and an LEC-specific gene knockout was highly efficient (137).

Applying single-nucleus RNA sequencing to study lymphedema- and lipedema-related adipose tissue, as has been performed in mouse adipose tissue (138), would enable the network of adipocyte, LEC, immune cell, and other cell type interactions to be further defined, and potentially elucidate the events that trigger and potentiate adipose hypertrophy with lymphatic impairment.

Clinical translation has been limited and few therapies are available to improve lymphatic function or lymphedema. Surgical approaches including vascularized lymph node transplantation (139) and liposuction (140) have proven effective in improving symptoms and quality of life in lymphedema patients, but there is currently no effective medical therapy. Lipedema or other generalized or subtle primary lymphatic defects may contribute to abnormal adipose deposition, but there are currently very few ways to evaluate or treat these conditions in humans, and further translational work still must be pursued. Lymphatic participation in adipogenesis, tissue inflammation, and lipid metabolism makes it a fascinating subject for further investigation into metabolic physiology and disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christina Usher for her assistance with creating the figures for this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01DK126789 and RC2DK116691).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FOXC2

forkhead box protein C2

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cell

- LV

lymphatic vessel

- NTS

neurotensin

- PROX1

Prospero homeobox 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed.

References

- 1. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372(6505):425-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Natale G, Bocci G, Ribatti D. Scholars and scientists in the history of the lymphatic system. J Anat. 2017;231(3):417-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eriksson G. Olaus Rudbeck as scientist and professor of medicine. Sven Med Tidskr. 2004;8(1):39-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ambrose CT. The priority dispute over the function of the lymphatic system and Glisson’s ghost (the 18th-century Hunter–Monro Feud). Cell Immunol. 2007;245(1):7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Bree E, Tsiaoussis J, Schoretsanitis G. The history of lymphatic anatomy and the contribution of Frederik Ruysch. Hell J Surg. 2018;90(6):308–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oliver G, Kipnis J, Randolph GJ, Harvey NL. The lymphatic vasculature in the 21st century: novel functional roles in homeostasis and disease. Cell. 2020;182(2):270-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Loukas M, Bellary SS, Kuklinski M, et al. The lymphatic system: a historical perspective. Clin Anat. 2011;24(7):807-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tammela T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis: molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell. 2010;140(4):460-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jessen NA, Munk ASF, Lundgaard I, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system – a beginner’s guide. Neurochem Res. 2015;40(12):2583-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yankova G, Bogomyakova O, Tulupov A. The glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics of the brain: new understanding of brain clearance. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32(7):693-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stritt S, Koltowska K, Mäkinen T. Homeostatic maintenance of the lymphatic vasculature. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(10):955-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Proulx ST, Luciani P, Dieterich LC, Karaman S, Leroux JC, Detmar M. Expansion of the lymphatic vasculature in cancer and inflammation: new opportunities for in vivo imaging and drug delivery. J Control Release. 2013;172(2):550-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jeltsch M, Tammela T, Alitalo K, Wilting J. Genesis and pathogenesis of lymphatic vessels. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(1):69-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alitalo K. The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1371-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baluk P, Fuxe J, Hashizume H, et al. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2349-2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuan EL, Ivanov S, Bridenbaugh EA, et al. Collecting lymphatic vessel permeability facilitates adipose tissue inflammation and distribution of antigen to lymph node-homing adipose tissue DCs. J Immunol. 2015;194(11):5200–5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ulvmar MH, Mäkinen T. Heterogeneity in the lymphatic vascular system and its origin. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;111(4):310-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang Y, Oliver G. Development of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):888-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mäkinen T, Adams RH, Bailey J, et al. PDZ interaction site in ephrinB2 is required for the remodeling of lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2005;19(3):397-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weber M, Hauschild R, Schwarz J, et al. Interstitial dendritic cell guidance by haptotactic chemokine gradients. Science. 2013;339(6117):328-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norrmén C, Ivanov KI, Cheng J, et al. FOXC2 controls formation and maturation of lymphatic collecting vessels through cooperation with NFATc1. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(3):439-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scallan JP, Knauer LA, Hou H, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Davis MJ, Yang Y. Foxo1 deletion promotes the growth of new lymphatic valves. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(14). doi: 10.1172/JCI142341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sibler E, He Y, Ducoli L, Keller N, Fujimoto N, Dieterich LC, Detmar M. Single-cell transcriptional heterogeneity of lymphatic endothelial cells in normal and inflamed murine lymph nodes. Cells. 2021;10(6):1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xiang M, Grosso RA, Takeda A, et al. A Single-cell transcriptional roadmap of the mouse and human lymph node lymphatic vasculature. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takeda A, Hollmén M, Dermadi D, et al. Single-cell survey of human lymphatics unveils marked endothelial cell heterogeneity and mechanisms of homing for neutrophils. Immunity. 2019;51(3):561-572.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hampton HR, Chtanova T. Lymphatic migration of immune cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Santambrogio L, Berendam SJ, Engelhard VH. The antigen processing and presentation machinery in lymphatic endothelial cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Randolph GJ, Ivanov S, Zinselmeyer BH, Scallan JP. The lymphatic system: integral roles in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:31-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lammoglia GM, Van Zandt CE, Galvan DX, Orozco JL, Dellinger MT, Rutkowski JM. Hyperplasia, de novo lymphangiogenesis, and lymphatic regression in mice with tissue-specific, inducible overexpression of murine VEGF-D. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311(2):H384-H394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karaman S, Hollmén M, Robciuc MR, et al. Blockade of VEGF-C and VEGF-D modulates adipose tissue inflammation and improves metabolic parameters under high-fat diet. Mol Metab. 2015;4(2):93-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chakraborty A, Barajas S, Lammoglia GM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor–D (VEGF-D) overexpression and lymphatic expansion in murine adipose tissue improves metabolism in obesity. Am J Pathol. 2019;189(4):924–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kataru RP, Jung K, Jang C, et al. Critical role of CD11b+ macrophages and VEGF in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis, antigen clearance, and inflammation resolution. Blood. 2009;113(22):5650-5659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cifarelli V, Eichmann A. The intestinal lymphatic system: functions and metabolic implications. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7(3):503-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dixon JB. Lymphatic lipid transport: sewer or subway? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(8):480-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Randolph GJ, Miller NE. Lymphatic transport of high-density lipoproteins and chylomicrons. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):929-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saharinen P, Tammela T, Karkkainen MJ, Alitalo K. Lymphatic vasculature: development, molecular regulation and role in tumor metastasis and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(7):387-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klotz L, Norman S, Vieira JM, et al. Cardiac lymphatics are heterogeneous in origin and respond to injury. Nature. 2015;522(7554):62-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oliver G, Detmar M. The rediscovery of the lymphatic system: old and new insights into the development and biological function of the lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2002;16(7):773-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wigle JT, Oliver G. Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell. 1999;98(6):769-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Deng J, Dai T, Sun Y, et al. Overexpression of Prox1 induces the differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into lymphatic endothelial-like cells in vitro. Cell Reprogram. 2017;19(1):54-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Procino A. Overexpression of Prox-1 gene in omental adipose tissue and adipocytes compared with subcutaneous adipose tissue and adipocytes in healthy patients. Cell Biol Int. 2014;38(7):888-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Redondo P de AG, Gubert F, Zaverucha-do-Valle C, et al. Lymphatic vessels in human adipose tissue. Cell Tissue Res. 2020;379(3):511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Srinivasan RS, Escobedo N, Yang Y, et al. The Prox1-Vegfr3 feedback loop maintains the identity and the number of lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors. Genes Dev. 2014;28(19):2175-2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goldman J, Le TX, Skobe M, Swartz MA. Overexpression of VEGF-C causes transient lymphatic hyperplasia but not increased lymphangiogenesis in regenerating skin. Circ Res. 2005;96(11):1193-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hirakawa S, Brown LF, Kodama S, Paavonen K, Alitalo K, Detmar M. VEGF-C-induced lymphangiogenesis in sentinel lymph nodes promotes tumor metastasis to distant sites. Blood. 2007;109(3):1010-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hominick D, Silva A, Khurana N, et al. VEGF-C promotes the development of lymphatics in bone and bone loss. Gerhardt H, ed. eLife. 2018;7:e34323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465(7297):483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Frye M, Taddei A, Dierkes C, et al. Matrix stiffness controls lymphatic vessel formation through regulation of a GATA2-dependent transcriptional program. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wong BW, Wang X, Zecchin A, et al. The role of fatty acid β-oxidation in lymphangiogenesis. Nature 2017;542(7639):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cifarelli V, Appak-Baskoy S, Peche VS, et al. Visceral obesity and insulin resistance associate with CD36 deletion in lymphatic endothelial cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mattacks CA, Pond CM. The effects of feeding suet-enriched chow on site-specific differences in the composition of triacylglycerol fatty acids in adipose tissue and its interactions in vitro with lymphoid cells. Br J Nutr. 1997;77(4):621-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jeltsch M, Kaipainen A, Joukov V, et al. Hyperplasia of lymphatic vessels in VEGF-C transgenic mice. Science. 1997;276(5317):1423-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rissanen TT, Markkanen JE, Gruchala M, et al. VEGF-D is the strongest angiogenic and lymphangiogenic effector among VEGFs delivered into skeletal muscle via adenoviruses. Circ Res. 2003;92(10):1098-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(5):367-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mathis D. Immunological goings-on in visceral adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2013;17(6):851-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Avogaro A, de Kreutzenberg SV. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;360(1-2):9-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Darimont C, Avanti O, Blancher F, et al. Contribution of mesothelial cells in the expression of inflammatory-related factors in omental adipose tissue of obese subjects. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(1):112-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weitman ES, Aschen SZ, Farias-Eisner G, et al. Obesity impairs lymphatic fluid transport and dendritic cell migration to lymph nodes. Plos One. 2013;8(8):e70703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Arngrim N, Simonsen L, Holst JJ, Bülow J. Reduced adipose tissue lymphatic drainage of macromolecules in obese subjects: a possible link between obesity and local tissue inflammation? Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(5):748-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Savetsky IL, Torrisi JS, Cuzzone DA, et al. Obesity increases inflammation and impairs lymphatic function in a mouse model of lymphedema. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307(2):H165-H172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Blum KS, Karaman S, Proulx ST, et al. Chronic high-fat diet impairs collecting lymphatic vessel function in mice. Plos One. 2014;9(4):e94713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. García Nores GD, Cuzzone DA, Albano NJ, et al. Obesity but not high-fat diet impairs lymphatic function. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(10):1582-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cao E, Watt MJ, Nowell CJ, et al. Mesenteric lymphatic dysfunction promotes insulin resistance and represents a potential treatment target in obesity. Nat Metab. 2021. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00457-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hespe GE, Kataru RP, Savetsky IL, et al. Exercise training improves obesity‐related lymphatic dysfunction. J Physiol. 2016;594(15):4267–4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Torrisi JS, Hespe GE, Cuzzone DA, et al. Inhibition of inflammation and iNOS improves lymphatic function in obesity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Farshid G, Weiss SW. Massive localized lymphedema in the morbidly obese: a histologically distinct reactive lesion simulating liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(10):1277-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. McLaughlin SA, Wright MJ, Morris KT, et al. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: objective measurements. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5213-5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Helyer LK, Varnic M, Le LW, Leong W, McCready D. Obesity is a risk factor for developing postoperative lymphedema in breast cancer patients. Breast J. 2010;16(1):48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Savetsky IL, Ghanta S, Gardenier JC, et al. Th2 cytokines inhibit lymphangiogenesis. Plos One. 2015;10(6):e0126908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shao X, Liu C. Influence of IFN- alpha and IFN- gamma on lymphangiogenesis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26(8):568-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zampell JC, Avraham T, Yoder N, et al. Lymphatic function is regulated by a coordinated expression of lymphangiogenic and anti-lymphangiogenic cytokines. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302(2):C392-C404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oka M, Iwata C, Suzuki HI, et al. Inhibition of endogenous TGF-beta signaling enhances lymphangiogenesis. Blood. 2008;111(9):4571-4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kataru RP, Kim H, Jang C, et al. T lymphocytes negatively regulate lymph node lymphatic vessel formation. Immunity. 2011;34(1):96-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Savetsky IL, Albano NJ, Cuzzone DA, et al. Lymphatic function regulates contact hypersensitivity dermatitis in obesity. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(11):2742-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Brice G, Child AH, Evans A, et al. Milroy disease and the VEGFR-3 mutation phenotype. J Med Genet. 2005;42(2):98-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):500-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Todo Y, Yamamoto R, Minobe S, et al. Risk factors for postoperative lower-extremity lymphedema in endometrial cancer survivors who had treatment including lymphadenectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(1):60-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jäger G, Döller W, Roth R. Quality-of-life and body image impairments in patients with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2006;39(4):193-200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Grada AA, Phillips TJ. Lymphedema: pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(6):1009-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Karlsson MK. Breast cancer-related chronic arm lymphedema is associated with excess adipose and muscle tissue. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7(1):3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hoffner M, Peterson P, Månsson S, Brorson H. Lymphedema leads to fat deposition in muscle and decreased muscle/water volume after liposuction: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Lymphat Res Biol. 2018;16(2):174-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rosen ED. The molecular control of adipogenesis, with special reference to lymphatic pathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;979:143-158; discussion 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nougues J, Reyne Y, Dulor JP. Differentiation of rabbit adipocyte precursors in primary culture. Int J Obes. 1988;12(4):321-333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Harvey NL, Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, et al. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat Genet. 2005;37(10):1072-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Koc M, Wald M, Varaliová Z, et al. Lymphedema alters lipolytic, lipogenic, immune and angiogenic properties of adipose tissue: a hypothesis-generating study in breast cancer survivors. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Levi B, Glotzbach JP, Sorkin M, et al. Molecular analysis and differentiation capacity of adipose-derived stem cells from lymphedema tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(3):580-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tavakkolizadeh A, Wolfe KQ, Kangesu L. Cutaneous lymphatic malformation with secondary fat hypertrophy. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54(4):367-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pond CM. Adipose tissue and the immune system. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73(1):17-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zampell JC, Aschen S, Weitman ES, et al. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis part I: adipogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):825-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhang J, Hoffner M, Brorson H. Adipocytes are larger in lymphedematous extremities than in controls. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2021:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Tashiro K, Feng J, Wu SH, et al. Pathological changes of adipose tissue in secondary lymphoedema. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):158-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Aschen S, Zampell JC, Elhadad S, Weitman E, De Brot Andrade M, Mehrara BJ. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis part II: expression of adipose differentiation genes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):838-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, et al. Obesity pathogenesis: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38(4):267-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ghaben AL, Scherer PE. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(4):242-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Buso G, Depairon M, Tomson D, Raffoul W, Vettor R, Mazzolai L. Lipedema: a call to action! Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(10):1567-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Szél E, Kemény L, Groma G, Szolnoky G. Pathophysiological dilemmas of lipedema. Med Hypotheses. 2014;83(5):599-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bilancini S, Lucchi M, Tucci S, Eleuteri P. Functional lymphatic alterations in patients suffering from lipedema. Angiology. 1995;46(4):333-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lohrmann C, Foeldi E, Langer M. MR imaging of the lymphatic system in patients with lipedema and lipo-lymphedema. Microvasc Res. 2009;77(3):335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Felmerer G, Stylianaki A, Hollmén M, et al. Increased levels of VEGF-C and macrophage infiltration in lipedema patients without changes in lymphatic vascular morphology. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. AL-Ghadban S, Cromer W, Allen M, et al. Dilated blood and lymphatic microvessels, angiogenesis, increased macrophages, and adipocyte hypertrophy in lipedema thigh skin and fat tissue. J Obes. 2019;2019:e8747461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Amann-Vesti BR, Franzeck UK, Bollinger A. Microlymphatic aneurysms in patients with lipedema. Lymphology. 2001;34(4):170-175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Suga H, Araki J, Aoi N, Kato H, Higashino T, Yoshimura K. Adipose tissue remodeling in lipedema: adipocyte death and concurrent regeneration. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(12):1293-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Priglinger E, Wurzer C, Steffenhagen C, et al. The adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction cells from lipedema patients: are they different? Cytotherapy. 2017;19(7):849-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bauer AT, von Lukowicz D, Lossagk K, et al. Adipose stem cells from lipedema and control adipose tissue respond differently to adipogenic stimulation in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(3):623-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Al-Ghadban S, Pursell IA, Diaz ZT, Herbst KL, Bunnell BA. 3D spheroids derived from human lipedema ASCs demonstrated similar adipogenic differentiation potential and ECM remodeling to non-lipedema ASCs in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):E8350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Herbst KL. Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33(2):155-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Waxler JL, Guardino C, Feinn RS, Lee H, Pober BR, Stanley TL. Altered body composition, lipedema, and decreased bone density in individuals with Williams syndrome: a preliminary report. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60(5):250-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Wolthuis DF, van Asbeck E, Mohamed M, et al. Cutis laxa, fat pads and retinopathy due to ALDH18A1 mutation and review of the literature. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(4):511-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Paolacci S, Precone V, Acquaviva F, et al. ; GeneOb Project . Genetics of lipedema: new perspectives on genetic research and molecular diagnoses. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(13):5581-5594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Szolnoky G, Nemes A, Gavallér H, Forster T, Kemény L. Lipedema is associated with increased aortic stiffness. Lymphology. 2012;45(2):71-79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Escobedo N, Proulx ST, Karaman S, et al. Restoration of lymphatic function rescues obesity in Prox1-haploinsufficient mice. JCI Insight. 2016;1(2). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Karkkainen MJ, Saaristo A, Jussila L, et al. A model for gene therapy of human hereditary lymphedema. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(22):12677-12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Mäkinen T, Jussila L, Veikkola T, et al. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis with resulting lymphedema in transgenic mice expressing soluble VEGF receptor-3. Nat Med. 2001;7(2):199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wagner M, Steinskog ES, Wiig H. Blockade of lymphangiogenesis shapes tumor-promoting adipose tissue inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2019;189(10):2102-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Kovacs P, Lehn-Stefan A, Stumvoll M, Bogardus C, Baier LJ. Genetic variation in the human winged helix/forkhead transcription factor gene FOXC2 in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 2003;52(5):1292-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Carlsson E, Groop L, Ridderstråle M. Role of the FOXC2 -512C>T polymorphism in type 2 diabetes: possible association with the dysmetabolic syndrome. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29(3):268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Cederberg A, Grønning LM, Ahrén B, Taskén K, Carlsson P, Enerbäck S. FOXC2 is a winged helix gene that counteracts obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and diet-induced insulin resistance. Cell. 2001;106(5):563-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Kim JK, Kim HJ, Park SY, et al. Adipocyte-specific overexpression of FOXC2 prevents diet-induced increases in intramuscular fatty acyl CoA and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1657-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Sato A, Kamekura R, Kawata K, et al. Novel mechanisms of compromised lymphatic endothelial cell homeostasis in obesity: the role of leptin in lymphatic endothelial cell tube formation and proliferation. Plos One. 2016;11(7):e0158408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Bouloumié A, Drexler HC, Lafontan M, Busse R. Leptin, the product of Ob gene, promotes angiogenesis. Circ Res. 1998;83(10):1059-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Park HY, Kwon HM, Lim HJ, et al. Potential role of leptin in angiogenesis: leptin induces endothelial cell proliferation and expression of matrix metalloproteinases in vivo and in vitro. Exp Mol Med. 2001;33(2):95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Wahlestedt C, Thyberg J, Cao Y. Leptin induces vascular permeability and synergistically stimulates angiogenesis with FGF-2 and VEGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(11):6390-6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Hubert A, Bochenek ML, Schütz E, Gogiraju R, Münzel T, Schäfer K. Selective deletion of leptin signaling in endothelial cells enhances neointima formation and phenocopies the vascular effects of diet-induced obesity in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(9):1683-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Shimizu Y, Shibata R, Ishii M, et al. Adiponectin-mediated modulation of lymphatic vessel formation and lymphedema. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(5):e000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Palanisamy K, Nareshkumar RN, Sivagurunathan S, Raman R, Sulochana KN, Chidambaram S. Anti-angiogenic effect of adiponectin in human primary microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2019;122:136-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Ouchi N, Kobayashi H, Kihara S, et al. Adiponectin stimulates angiogenesis by promoting cross-talk between AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt signaling in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(2):1304-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Li J, Li E, Czepielewski RS, et al. Neurotensin is an anti-thermogenic peptide produced by lymphatic endothelial cells. Cell Metab. 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Bachmann SB, Gsponer D, Montoya-Zegarra JA, et al. A distinct role of the autonomic nervous system in modulating the function of lymphatic vessels under physiological and tumor-draining conditions. Cell Rep. 2019;27(11):3305-3314.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Panuncio AL, De La Peña S, Gualco G, Reissenweber N. Adrenergic innervation in reactive human lymph nodes. J Anat. 1999;194 (Pt 1):143-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Choi Y-K, Fallert Junecko BA, Klamar CR, Reinhart TA. Characterization of cells expressing lymphatic marker LYVE-1 in macaque large intestine during simian immunodeficiency virus infection identifies a large population of nonvascular LYVE-1+/DC-SIGN+ cells. Lymphat Res Biol. 2013;11(1):26-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, Lagutin OV, et al. Lineage tracing demonstrates the venous origin of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2007;21(19):2422-2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Risebro CA, Searles RG, Melville AAD, et al. Prox1 maintains muscle structure and growth in the developing heart. Development. 2009;136(3):495-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Torii Ma, Matsuzaki F, Osumi N, et al. Transcription factors Mash-1 and Prox-1 delineate early steps in differentiation of neural stem cells in the developing central nervous system. Development. 1999;126(3):443-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Wigle JT, Chowdhury K, Gruss P, Oliver G. Prox1 function is crucial for mouse lens-fibre elongation. Nat Genet. 1999;21(3):318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Sosa-Pineda B, Wigle JT, Oliver G. Hepatocyte migration during liver development requires Prox1. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):254-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Gil HJ, Ma W, Oliver G. A novel podoplanin-GFPCre mouse strain for gene deletion in lymphatic endothelial cells. Genesis. 2018;56(4):e23102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Han X, Zhang Z, He L, et al. A suite of new Dre recombinase drivers markedly expands the ability to perform intersectional genetic targeting. Cell Stem Cell 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Sárvári AK, Van Hauwaert EL, Markussen LK, et al. Plasticity of epididymal adipose tissue in response to diet-induced obesity at single-nucleus resolution. Cell Metab. 2021;33(2):437-453.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Gould DJ, Mehrara BJ, Neligan P, Cheng MH, Patel KM. Lymph node transplantation for the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol. 2018;118(5):736-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Granoff MD, Pardo J, Singhal D. Power-assisted liposuction: an important tool in the surgical management of lymphedema patients. Lymphat Res Biol. 2021;19(1):20-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed.