Abstract

Background

Interruption of benznidazole therapy due to the appearance of adverse effects, which is presumed to lead to treatment failure, is a major drawback in the treatment of chronic Chagas disease.

Methods

Trypanosoma cruzi-specific humoral and T cell responses, T cell phenotype and parasite load were measured to compare the outcome in 33 subjects with chronic Chagas disease treated with an incomplete benznidazole regimen and 58 subjects treated with the complete regimen, during a median follow-up period of 48 months.

Results

Both treatment regimens induced a reduction in the T. cruzi-specific antibody levels and similar rates of treatment failure when evaluated using quantitative PCR. Regardless of the regimen, polyfunctional CD4+ T cells increased in the subjects, with successful treatment outcome defined as a decrease of T. cruzi-specific antibodies. Regardless of the serological outcome, naive and central memory T cells increased after both regimens. A decrease in CD4+ HLA-DR+ T cells was associated with successful treatment in both regimens. The cytokine profiles of subjects with successful treatment showed fewer inflammatory mediators than those of the untreated T. cruzi-infected subjects. High levels of T cells expressing IL-7 receptor and low levels of CD8+ T cells expressing the programmed cell death protein 1 at baseline were associated with successful treatment following benznidazole interruption.

Conclusions

These findings challenge the notion that treatment failure is the sole potential outcome of an incomplete benznidazole regimen and support the need for further assessment of the treatment protocols for chronic Chagas disease.

Introduction

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, affecting 6–8 million people worldwide.1 Due to migration flow, it is also a public health problem in non-endemic areas.2 Benznidazole and nifurtimox are the two drugs available for the treatment of T. cruzi infection and are recommended during the acute phase and early stages of chronic Chagas disease in children and in women of childbearing age.1,3 The application of these drugs in the treatment of adult subjects in the chronic phase is limited owing to the occurrence of adverse events that could lead to a treatment suspension rate of 12%–30% and the need for long-term follow-up to determine treatment efficacy.4,5

The optimum duration of the treatment regimen for chronic Chagas disease is still in question because a 60 day treatment regimen with benznidazole led to an outcome similar to that of a 30 day regimen.6–8 A fixed dose versus a weight-adjusted dose of benznidazole is also indicated.9 Furthermore, short-term benznidazole treatment or lower benznidazole doses cured a subset of mice with murine T. cruzi infection.10–13 A retrospective study of subjects with chronic Chagas disease for whom benznidazole treatment was terminated owing to adverse reactions 5 years prior to the study showed seroconversion to negative results in 20% of the subjects.14 Despite drug discovery efforts during the last decade for Chagas disease, benznidazole and nifurtimox are the only treatment options currently available. Thus, what clinicians can expect after discontinuation of benznidazole is an important issue in the treatment of adult subjects with chronic Chagas disease.

There is an emerging consensus that the persistence of parasites is the primary cause of cumulative tissue damage in chronic Chagas disease.15,16 One of the reasons for an exacerbated inflammatory process in the more severe forms of the disease might be that T. cruzi-specific T cell responses become less effective due to a process of immune exhaustion, which can lead to a depletion of parasite-specific T cells.17–21 Not only do T. cruzi-specific T cells decline over time, the immunoregulatory pathways that avoid tissue damage are also altered in chronic Chagas disease.22–24 This outcome does not mean that T cells are totally ineffective in controlling the infection, but as the efficacy of the immune response declines, the ability to maintain control of the parasite burden without increasing the level of tissue damage becomes more difficult. Treatment with benznidazole during the chronic phase of T. cruzi infection induces prominent changes in T cell function and T cell phenotypes.20,25–27

Here, we monitored T. cruzi-specific humoral and T cell responses, pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels, the degree of differentiation and activation of total peripheral T cells, and parasite load in subjects with chronic Chagas disease to compare outcomes between subjects who received complete or incomplete treatment regimens with benznidazole because of adverse events.

Patients and methods

Selection of the study population and treatment administration

T. cruzi-infected and uninfected volunteers aged 21–55 years were recruited at Hospital Interzonal General de Agudos Eva Perón (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Individuals who were seropositive for at least two of the three tests performed, i.e. indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) assay, indirect haemagglutination assay (IHA) and ELISA,1 were considered to be infected. According to a modified Kuschnir clinical classification,28 subjects in Group 0 (G0) showed normal results for ECG, chest radiography and echocardiography, while the subjects in Group 1 (G1) showed normal chest radiography and echocardiography findings but abnormal ECG results (Table 1). Thirteen age-matched uninfected subjects, born and raised in Buenos Aires, where T. cruzi infection is not endemic, were also included. The treatment consisted of benznidazole administered at 5 mg/kg body weight per day for 30 days.7 All subjects with severe dermatitis discontinued benznidazole therapy and received antihistamines and nine subjects also received a short course of corticosteroids. Clinical, serological and immunological analyses were performed before treatment, 2, 6 and 12 months after treatment, and at yearly intervals thereafter. Signed informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to inclusion in the study. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hospital Eva Perón (Protocol DMID No. 14-0004). Individuals with ischaemic heart disease, cancer, HIV infection, syphilis, diabetes, arthritis or serious allergies were excluded from this study.

Table 1.

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of subjects with chronic Chagas disease included in the study

| Benznidazole regimen (5 mg/kg/day) |

Median treatment duration, days (IQR) | Clinical stage at baselinea (n) |

Sex (n) |

Median age at baseline, years (range) | Time range of follow-up, months | Adverse events (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 | G1 | Female | Male | |||||

| Incompleteb | 11 (7–15) | 28 | 5 | 28 | 5 | 42 (21–55) | 12–120 | Severe gastrointestinal symptoms (5) |

| Severe dermatitis (26) | ||||||||

| Other (2) | ||||||||

| Complete | 30 | 50 | 8 | 32 | 26 | 42 (23–55) | 12–120 | Gastrointestinal symptoms (1)c |

| Mild dermatitis (13)c | ||||||||

| Moderate dermatitis (3) | ||||||||

| Other (1) | ||||||||

G0, seropositive individuals with normal chest radiography, echocardiography and ECG; G1, seropositive individuals with normal chest radiography and echocardiography but ECG abnormalities.

Treatment was suspended owing to the appearance of severe adverse events.

One subject presented with dermatitis and gastrointestinal symptoms concomitantly.

Collection of PBMCs and serum specimens

Fifty millilitres of blood was drawn from each subject via venepuncture and collected in heparinized Vacutainer® tubes (BD Biosciences). PBMCs were isolated using the Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) system and were cryopreserved for later analysis. Ten millilitres of blood from each subject was coagulated at room temperature and centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min for serum separation. Assays were not run for all samples owing to the limited quantity of blood samples.

T. cruzi antigens

Protein lysate was obtained after four freeze/thaw cycles followed by sonication of T. cruzi amastigotes derived from the Brazil strain of the parasite, as previously described.29

Multiplex serological assay

Serum specimens were screened for antibodies reactive to a panel of eight recombinant T. cruzi proteins in a Luminex-based format, as described elsewhere.30

Quantitative T. cruzi DNA amplification

Five millilitres of each blood sample was mixed with an equal volume of 6.0 M guanidine hydrochloride and 0.2 M EDTA, pH 8 (guanidine/EDTA/blood, GEB). Sample DNA isolation and parasite quantification were performed by amplifying a T. cruzi satellite sequence with SYBR® green-based real-time PCR31 and confirmed using a TaqMan® probe assay.32

Cytometric bead array (CBA) for cytokines

CBA assays were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences) using the cell supernatant derived from PBMCs stimulated with the T. cruzi lysate or with RPMI alone, as described in previous studies.26 The samples were acquired on an FACSAria™ II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysed using FCAP Array Software v1.4.

Intracellular cytokine and cell-surface phenotypic staining for T cells

For each sample, 4 × 106 PBMCs/well were stimulated with 15 μg/mL T. cruzi amastigote lysate or RPMI alone. CD28/CD49d antibody at 1 μg/mL (BD Biosciences) was added for 16–20 h, brefeldin A was added for the last 5 h of incubation, and the mixture was processed for intracellular staining as described elsewhere.33 Antihuman antibodies against the following were used: CD3, the Fixable Viability Stain 510 (FVS510), CD154, IFN-γ, TNF-α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP)-1β and IL-2 (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). The gating of populations was determined by the use of ‘fluorescence minus one’ samples and the unstimulated control. The background responses detected in the unstimulated control samples were subtracted from those detected in the T. cruzi-stimulated samples for the 31 combinations defined by the Boolean gating strategy of FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA), as described33,34 (Figure S1). To set up cut-off values, the average of T. cruzi-specific T cell responses + 3 SD in three uninfected donors was calculated. For phenotypic analysis, 1 × 106 PBMCs were stained with the appropriate combination of the antihuman antibodies against CD4, CD8, CD3, CD45RA, CD127, CD132, CCR7, CD62L, HLA-DR, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (TIM3) for 30 min at 4°C (Table S1). Approximately 600 000 events were acquired per sample in the FACSAria™ II flow cytometer.

Statistics

Normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. A serological treatment response was defined as a significant decrease in at least two conventional serological assays (i.e. 30% reduction in ELISA titres and a 2-fold dilution in IHA or IIF) or a 50% reduction in the reactivity of at least one protein in the multiplex assay.26 Comparisons between groups were performed at similar timepoints. Fisher’s exact test was applied to evaluate differences between proportions and Mann–Whitney U-test or Student’s t-test was used to compare independent groups. Post-treatment changes over time were evaluated using a linear mixed model with compound symmetry, with time as a fixed effect and treatment regimen as an interaction term. Cytokine concentration was analysed using principal component analysis (PCA). A univariate analysis was conducted to evaluate the baseline characteristics associated with successful therapy. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism v8.0, IBM SPSS® Statistics v23.0 (IBM Corp.) and analytical software Statistix 10.0.

Results

Clinical characteristics of and parasite load in subjects with chronic Chagas disease treated with incomplete or complete benznidazole regimens

The main adverse drug reaction and the major cause for treatment suspension was severe dermatitis, with a median treatment time of 11 days (Table 1). Mild dermatitis was also observed but did not lead to treatment suspension. Among those who received an incomplete benznidazole regimen, a change from the G0 to the G1 clinical group was observed in two subjects, with a median follow-up period of 48 months (range: 12–120 months). One of these subjects had hypertension and a −30° left-axis deviation on ECG prior to therapy and presented a left anterior fascicular block at 36 months post-treatment. The other subject had hypertension and inferobasal hypokinesia without dilation of the left ventricle prior to treatment and presented with atrial fibrillation 7 years post-treatment.

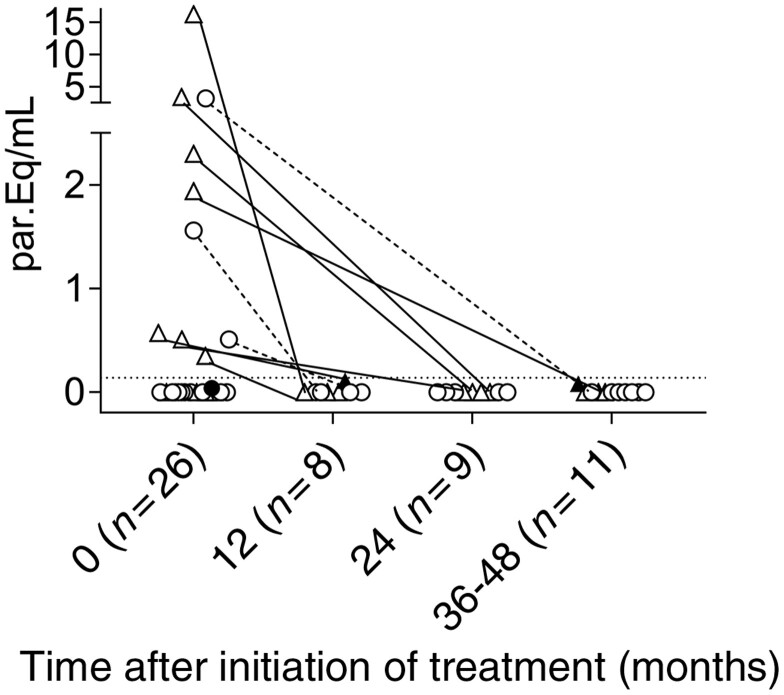

In a subgroup of 26 subjects from whom pre-treatment and post-treatment samples were obtained, a parasite load was detected in 42% of the samples (7 in the incomplete treatment group and 4 in the complete treatment group) prior to treatment (Figure 1). The parasitic DNA was quantifiable in 10 of the 11 patients with detectable parasite DNA. Following treatment, the PCR values were undetectable in five of the seven subjects (71%) in the incomplete treatment group and in all four subjects (100%) in the complete treatment group (Figure 1) and remained detectable but not quantifiable in two additional subjects in the incomplete treatment group. In an additional group of subjects from whom only post-treatment samples were obtained, parasite DNA was detectable but not quantifiable in 1 of 10 subjects and in 4 of 23 subjects in the incomplete and complete regimen groups, respectively. At the end of the follow-up, the rate of treatment failure was not different between the two treatment groups; a total of 3 of 24 (13%) and 4 of 35 (11%) subjects in the incomplete and complete treatment groups, respectively, had positive but non-quantifiable PCR values. This supports a trypanocidal effect of the treatment even after an incomplete benznidazole regimen.

Figure 1.

Quantification of parasite DNA using quantitative PCR prior to and after incomplete or complete treatment regimens with benznidazole in subjects with chronic Chagas disease. Satellite DNA was quantified in adult subjects after incomplete (triangles, n = 14) and complete (circles, n = 12) treatment regimens. Each symbol represents the quantitative PCR value for each subject. Dotted lines represent the limit of quantification established at 0.14 parasites/mL of blood that contain equivalent amounts of DNA to the sample (i.e. par.Eq/mL).16 Closed symbols show samples with detectable but non-quantifiable DNA.

Similar rates of reduction of T. cruzi-specific antibodies following incomplete and complete treatment with benznidazole

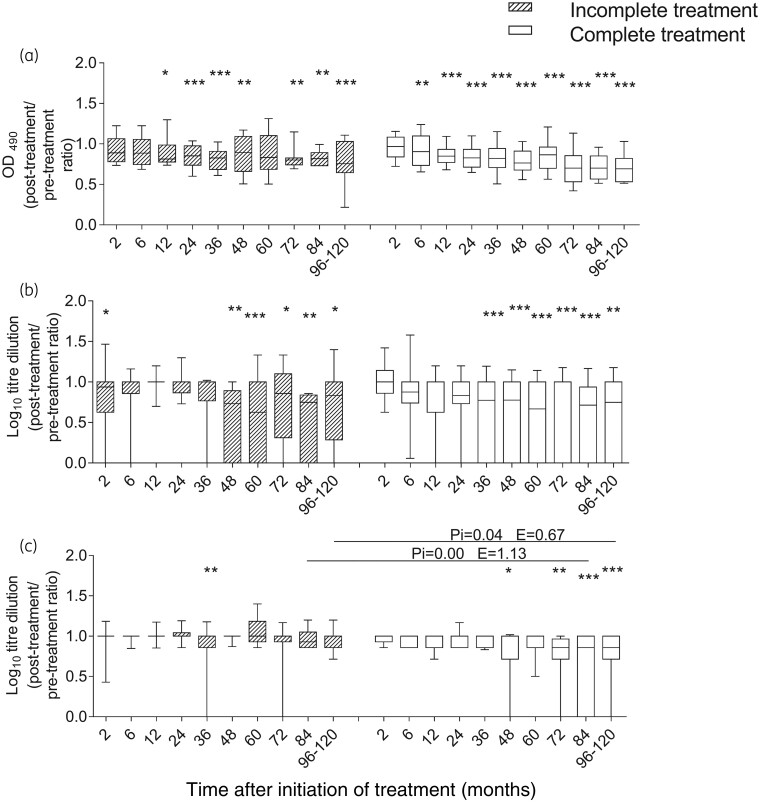

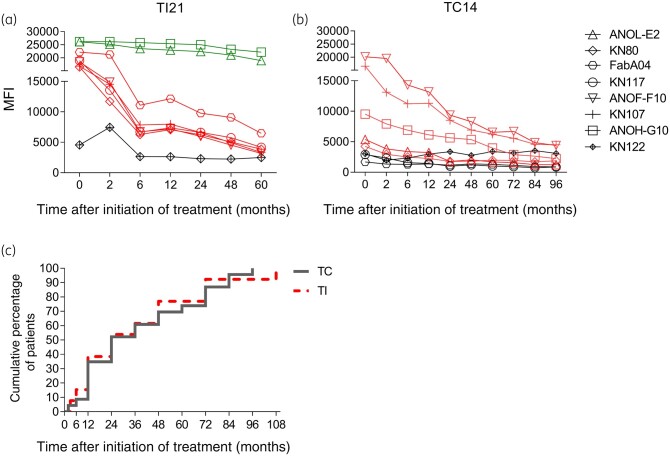

Reversion to negative serology and a significant decrease in antibody titres seen in at least two conventional serological tests or in the multiplex assay were considered to evaluate serological outcomes following treatment.26,28 The proportion of subjects with reduced antibody levels, a mark of successful treatment, was similar for both regimens at 48 months post-treatment (i.e. the median follow-up period in subjects with incomplete benznidazole treatment) and at the end of follow-up (Table 2). Using ELISA and IHA, a prominent decline in the levels of T. cruzi-specific antibodies was observed earlier in subjects who received complete benznidazole treatment than in subjects of the incomplete treatment group (i.e. 6–36 months after complete treatment versus 12–48 months after incomplete treatment; Figure 2a and b). At 36–48 months of follow-up, reduction in the T. cruzi antibody levels by IIF was not evident in either group. At later timepoints, only subjects receiving a complete benznidazole regimen showed a significant antibody decline by IIF (Figure 2c). In contrast, the time of decline of the antibody levels seen in the Luminex assay was similar for both treatment regimens (Figure 3a–c).

Table 2.

Levels of T. cruzi-specific antibodies measured using conventional serological tests and multiplex assays following incomplete and complete benznidazole treatments

| Regimen | Time of evaluation (months), median; range |

No. of subjects with serological treatment response/total subjects evaluated (%) |

Total (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seroconversion to negative findingsa | Decline in antibody titre by conventional testsa | Decline in antibody titre by multiplex assay | |||

| Incomplete | 48; 24–120 (end of follow-up) | 2/27 (7) | 2/27 (7) | 14/27 (52) | 15/27 (56)b |

| Complete | 48; 24–48 | 5/43 (12) | 2/43 (5) | 16/40 (40) | 19/43 (44)c |

| 96; 24–120 (end of follow-up) | 3/43 (7) | 8/43 (19) | 24/40 (60) | 27/43 (63)c | |

Following treatment, the subjects were grouped according to the degree of decline in the levels of T. cruzi-specific antibodies.

T. cruzi-specific antibodies were measured using IIF assay, IHA and ELISA. Differences between groups were analysed using Fisher’s exact test.

One subject from the incomplete benznidazole regimen group showed a decline in the antibody levels measured using conventional serology tests only.

Three subjects from the complete benznidazole regimen group showed a decline in the antibody levels measured using conventional serology tests only.

Figure 2.

T. cruzi-specific humoral response measured using conventional serological tests in subjects with chronic Chagas disease undergoing incomplete and complete benznidazole treatment regimens. The post-treatment/pre-treatment antibody ratios measured using ELISA (a), IHA (b) and IIF assay (c) at different timepoints after benznidazole therapy are depicted. Medians and 10–90 percentile values are shown for the incomplete (striped boxes, n = 33) and complete (white boxes, n = 58) treatment groups. Changes from baseline (Time 0) and between groups were evaluated using a linear mixed model for repeated measures. *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01 and * P < 0.05 compared with pre-treatment values. Pi indicates the P value of the linear mixed model with interaction between the incomplete and complete treatment regimens. E is the estimate value of the linear mixed model comparing the incomplete and complete treatment groups.

Figure 3.

T. cruzi-specific humoral response measured using the multiplex technique in subjects with chronic Chagas disease following incomplete and complete benznidazole regimens. Serum specimens were screened using a bead array-based multiplex serological assay. Plots a and b show representative data for a subject who underwent an incomplete regimen (TI21) (a) and a subject who underwent a complete regimen (TC14) (b), for the different proteins assessed. Each point represents the MFI of reactive (red and green lines) and non-reactive (black lines) proteins prior to treatment (Time 0) and at several post-treatment timepoints. Red lines and symbols indicate more than 50% decreased reactivity compared with baseline reactivity, while green lines and symbols indicate unaltered reactivity post-treatment. (c) Cumulative percentage of subjects reaching a significant decline in T. cruzi antibody levels following incomplete (TI, n = 14, red dotted line) or complete (TC, n = 21, grey line) benznidazole regimens.

Improved polyfunctional CD4+ T cell response and declined pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels in subjects with a successful outcome following incomplete or complete benznidazole regimens

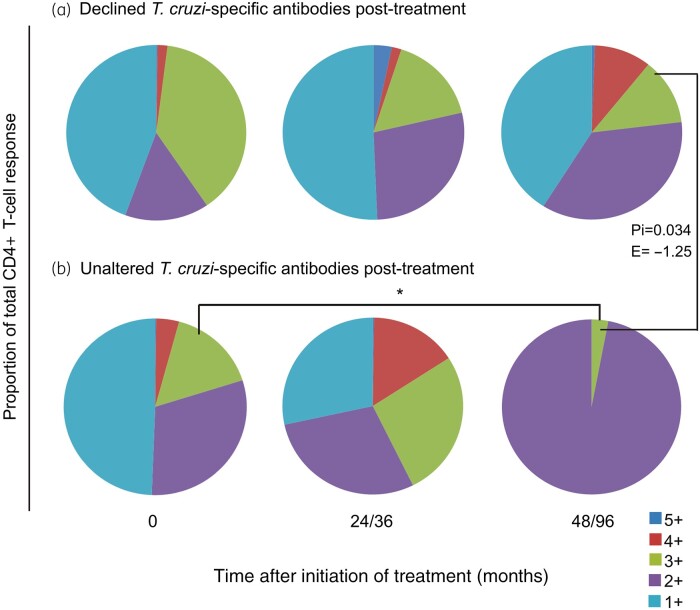

Using a linear mixed model, we compared the post-treatment changes in T. cruzi-specific polyfunctional T cells for both treatment regimens according to the serological outcome at the end of follow-up. Among subjects with declined or unaltered T. cruzi-specific antibodies, changes in polyfunctional T cell responses were not significantly different between the treatment regimens. Regardless of the regimen, polyfunctional CD4+ T cells had increased at 24–36 months post-treatment but were sustained later only in subjects with declined T. cruzi-specific antibodies (Figure 4a and b; Figure S2a), whereas enrichment of CD4+ T cells with one or two functions was observed in subjects who failed to achieve a serological response to treatment (Figure 4b; Figure S2b). Likewise, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) evaluation showed that cytokine production among polyfunctional and monofunctional T cells only increased in subjects with declining T. cruzi-specific antibodies post-treatment (Figure S3).

Figure 4.

Functionality of T. cruzi-specific CD4+ T cells in subjects with chronic Chagas disease before and after successful treatment with complete or incomplete benznidazole regimens. PBMCs were stimulated with a T. cruzi lysate preparation and analysed using flow cytometry for intracellular expression of IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, MIP-1β and CD154 in CD4+ T cells. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters, and CD3+ cells were then analysed for CD4 versus each marker. Cytokine co-expression profiles with one (1+), two (2+), three (3+), four (4+) and five (5+) functions were determined in subjects who underwent incomplete (n = 12) or complete (n = 7) treatment regimens, using the Boolean gating function of FlowJo software. A detected antigen-specific response was defined as a positive response when it was higher than the cut-off, at least twice the response with media alone and if there were at least three events.34 The contribution of each cytokine-producing subset to the total T. cruzi-specific CD4+ T cell response was assessed in donors showing a positive response in the intracellular staining assay. The average for each combination was calculated. Each slice of the pie chart represents the fraction of the total response that consists of CD4+ T cells positive for one to five functions (light blue, violet, green, red and blue, respectively) in subjects with declined (a) and unaltered (b) T. cruzi antibodies post-treatment, regardless of the type of regimen. Changes from baseline (Time 0) and between groups were evaluated using a linear mixed model for repeated measures. *P < 0.05 compared with pre-treatment values. Pi indicates the P value of the linear mixed model with an interaction between the incomplete and complete treatment regimens. E indicates the estimate value of the linear mixed model comparing the incomplete and complete treatment groups.

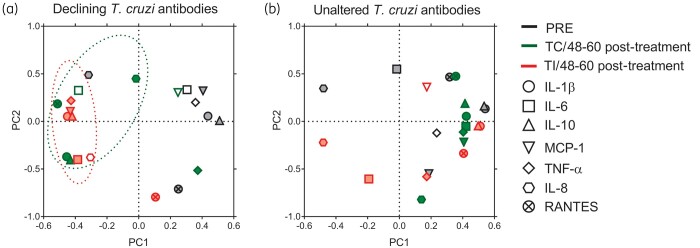

PCA showed that among the subjects with declining T. cruzi-specific antibodies, after incomplete or complete treatment, the cytokine profile clustered together and separately from the pre-treatment profile, with decreased IL-1β, IL-10 and TNF-α levels compared with the pre-treatment status (Figure 5a). In contrast, among subjects with unaltered T. cruzi antibodies, the cytokine profile prior to and after incomplete or complete treatment did not vary significantly (Figure 5b). In summary, in subjects with complete or incomplete benznidazole treatment, T. cruzi-specific T cell function was restored to some extent, while pro-inflammatory responses declined.

Figure 5.

PCA of cytokine production in T. cruzi-infected subjects following incomplete or complete benznidazole treatment. CBA assays were conducted with the supernatants of T. cruzi-stimulated PBMCs of subjects with an incomplete (TI, n = 17) or complete (TC, n = 11) treatment regimen. Following log transformation, the principal components were extracted with eigenvalues of 1.0. Factor loadings >0, 4 or < −0.4 were considered as influential mediators (filled symbols). Loading plots depict the relationship between the first two principal components (PC1, PC2) and the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and TNF-α in the pre-treatment (PRE) stage and at 48–60 months after complete or incomplete treatment in subjects with declining T. cruzi antibodies (a; TC n = 4, TI n = 10) or unaltered T. cruzi antibodies (b; TC n = 7, TI n = 7).

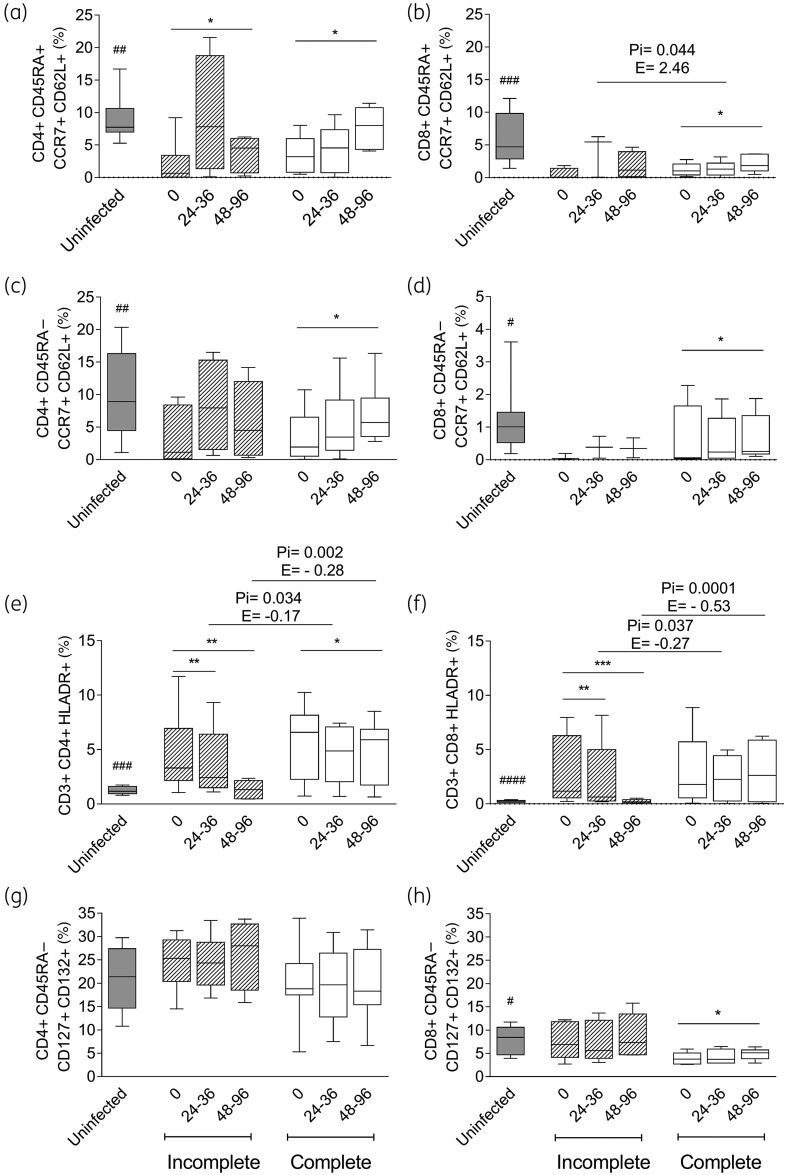

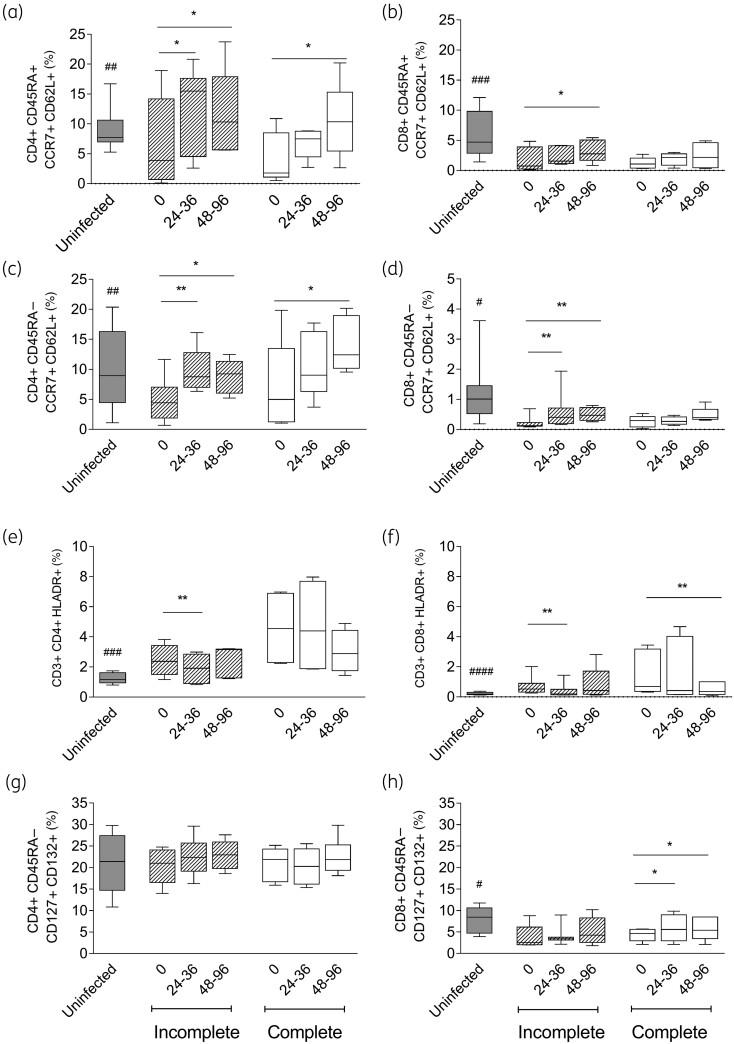

Similar phenotypes of total T cells after incomplete and complete benznidazole regimens

Chronic T. cruzi infection induced higher activated T cell levels and reduced naive and central memory T cell levels compared with those in uninfected subjects35–37 (Figures 6 and 7). Regardless of the serological outcome, the naive CD45RA+ CCR7+ CD62L+ (Figure 6a and b; Figure 7a and b) and central memory CD45RA− CCR7+ CD62L+ (Figure 6c and d; Figure 7c and d) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells increased following both regimens, whereas memory CD8+ T cells expressing IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) (i.e. CD45RA− CD127+ CD132+) increased significantly only after the complete regimen (Figures 6h and 7h). In contrast, memory CD4+ T cells expressing IL-7R did not change after either regimen (Figures 6g and 7g). The activated CD4+ HLA-DR+ T cells decreased along with the T. cruzi antibodies after both regimens. The decrease was more pronounced in the incomplete treatment group (Figure 6e), while it did not change in subjects with unaltered T. cruzi antibodies post-treatment (Figure 7e). A decrease in CD8+ HLA-DR+ T cells was also associated with successful treatment in subjects with incomplete but not with complete benznidazole regimens (Figures 6f and 7f). The frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing the inhibitory receptors PD-1 and/or TIM3 did not change following either regimen (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Phenotypic profiles of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in T. cruzi-infected subjects with declined T. cruzi-specific antibodies following incomplete or complete benznidazole treatment regimens. PBMCs were stained with the indicated monoclonal antibodies and analysed using flow cytometry. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were then selected and analysed for the different T cell phenotypes. Bars indicate the median and IQR of the percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing a particular phenotype prior to (0) and after the incomplete (n = 8) or complete (n = 6) treatment regimen for the infected subjects and in the uninfected subjects (n = 10). Frequencies of naive (a and b), central memory (c and d), activated (e and f) and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing IL-7R (g and h) are provided. *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01 and * P < 0.05 compared with pre-treatment values using a linear mixed model for repeated measures. Pi indicates the significant P value of the linear mixed model with interaction between the incomplete and complete treatment regimens. E indicates the estimate value of the linear mixed model. ####P < 0.0001, ###P < 0.001, ##P < 0.01 and #P < 0.05 compared with untreated T. cruzi-infected subjects (Time 0).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic profiles of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in T. cruzi-infected subjects with unaltered T. cruzi-specific antibodies following incomplete or complete benznidazole treatment regimens. PBMCs were stained with the indicated monoclonal antibodies and analysed using flow cytometry. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were then selected and analysed for the different T cell phenotypes. Bars indicate the median and IQR of the percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing a particular phenotype prior to (0) after incomplete (n = 8) or complete (n = 6) treatment regimens for the infected subjects and in the uninfected subjects (n = 10). Frequencies of naive (a and b), central memory (c and d), activated (e and f) and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing IL-7R (g and h) are provided. ** P < 0.01 and * P < 0.05 compared with pre-treatment values using a linear mixed model for repeated measures. No significant differences were found between the incomplete and complete treatment regimens applying a linear mixed model with treatment interaction. ####P < 0.0001; ###P < 0.001, ##P < 0.01 and #P < 0.05 compared with untreated T. cruzi-infected subjects (Time 0).

Lower baseline PD-1 expression and differentiation of T cells in subjects with reduced antibody titres after incomplete treatment with benznidazole

We tested whether any of the immunological parameters measured prior to therapy were associated with treatment outcome, following an incomplete or complete benznidazole regimen. Elevated frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells expressing IL-7R were associated with a higher probability of decline in the T. cruzi antibody levels after an incomplete benznidazole regimen, while a higher frequency of CD8+ PD-1+ T cells was associated with a lower probability of decline in the T. cruzi antibody levels after an incomplete regimen (Table 3). The total frequency of polyfunctional CD4+ T cells was the only predictive variable for successful treatment among subjects receiving the complete benznidazole regimen (P = 0.09, data not shown).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics associated with serological treatment responses after incomplete treatment with benznidazole in chronic Chagas disease

| Variablea | Effective treatmentb |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 15) | No (n = 12) | ||

| Age (years) | 43 | 44 | 0.75 |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 647 | 1041 | 0.29 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 16 513 | 16 010 | 0.59 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 19.63 | 39.13 | 0.38 |

| IP-10 (pg/mL) | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.68 |

| MCP-1 (pg/mL) | 156 | 180 | 0.70 |

| MIG (pg/mL) | 2.50 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| TNF (pg/mL) | 202 | 451 | 0.20 |

| Total polyfunctional CD4+ T cells (%) | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells (%) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.87 |

| CD4+ IL-2+ T cells (%) | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.87 |

| CD4+ CD154+ T cells (%) | 0.04 | 0.10 | 1 |

| CD4+ TNF+ T cells (%) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| CD4+ MIP-1β+ T cells (%) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.75 |

| CD4+ HLA-DR+ (%) | 3.30 | 2.55 | 0.40 |

| CD4+ CD45RA+ CCR7+ CD62L+ (%) | 0.65 | 2.92 | 0.24 |

| CD4+ CD45RA− CCR7+ CD62+ (%) | 1.13 | 2.88 | 0.52 |

| CD4+ CD45RA+ CD127− CD132+ (%) | 1.71 | 2.62 | 0.90 |

| CD4+ CD45RA+ CD127+ CD132+ (%) | 5.75 | 6.60 | 0.71 |

| CD4+ CD45RA− CD127− CD132+ (%) | 7.73 | 4.95 | 0.21 |

| CD4+ CD45RA− CD127+ CD132+ (%) | 25.34 | 18.70 | 0.05 |

| CD4+ PD-1+ (%) | 0.22 | 0.55 | 0,18 |

| CD4+ T1M3+ (%) | 0.59 | 0.91 | 0.10 |

| CD8+ HLA-DR+ (%) | 1.17 | 0.76 | 0.29 |

| CD8+ CD45RA+ CCR7+ CD62L+ (%) | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.24 |

| CD8+ CD45RA− CCR7+ CD62+ (%) | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| CD8+ CD45RA+ CD127− CD132+ (%) | 3.57 | 3.91 | 0.49 |

| CD8+ CD45RA+ CD127+ CD132+ (%) | 5.03 | 5.39 | 0.65 |

| CD8+ CD45RA− CD127− CD132+ (%) | 9.10 | 3.34 | 0.11 |

| CD8+ CD45RA− CD127+ CD132+ (%) | 8.59 | 2.33 | 0.02 |

| CD8+ PD-1+ (%) | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.084 |

| CD8+ TIM3+ (%) | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.45 |

MIG, monokine induced by IFN-γ.

Data for continuous variables are shown as medians.

Response to treatment at the end of follow-up comprised seroconversion to negative findings and significant declines in T. cruzi-specific antibody titres by conventional serology and multiplex assays. For univariate analysis the Mann–Whitney U-test or Student’s t-test were used, as appropriate. Italic values indicate P values of <0.1.

Discussion

The development of adverse effects is considered the main drawback of treating chronic T. cruzi infection with benznidazole because it is generally assumed to lead to treatment failure.4,38 Thus, few studies have focused on monitoring subjects with benznidazole discontinuation.14,39,40 This prospective analysis showed that treatment of T. cruzi-infected subjects with an incomplete benznidazole regimen had a rate of effectiveness similar to that of treatment with a complete regimen, as demonstrated by reductions in T. cruzi-specific antibodies and parasite load and by changes in T cell function and phenotype associated with parasite clearance in the subjects.

The measurement of T. cruzi antibodies for individual proteins using the multiplex technique not only confirmed that a similar proportion of subjects of both regimens presented decreased levels of T. cruzi antibodies but also showed that the length of follow-up to observe this post-treatment decline did not differ between the regimens. However, the level of T. cruzi antibodies decreased faster by conventional serological tests in subjects undergoing a complete benznidazole regimen. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that defined antigens may be more sensitive in detecting these changes than mixed antigens.28,41 Conversion to negative test results and a decrease in the titre of T. cruzi antibodies are currently accepted as successful outcomes of treatment since the T. cruzi-specific antibody levels are not likely to change in the untreated subjects.28,42 The more likely explanation for the decline in parasite-specific antibody titres is that a significant drop in parasite load occurred in both treated groups. Other authors have shown a significant drop in serum titres in patients with sustained negative PCR results.39 In our study, this explanation is supported because most of the 42% of samples that were positive and the 38% of samples that were quantifiable prior to treatment were negative for parasitic DNA post-treatment. Notably, none of the samples had quantifiable parasitaemia after complete or incomplete regimens. However, a negative PCR does not indicate complete parasite clearance and the presence of parasites in tissues or circulating parasites at levels below the limits of detection cannot be excluded.38,43,44 Therefore, long-term follow-up with data correlating parasite load, T. cruzi-specific humoral responses by conventional and non-conventional techniques, disease progression and immunological markers might help to better ascertain treatment efficacy.

Contrary to our findings, other studies have shown higher rates of treatment failure and minor declines in T. cruzi-specific antibodies following an interrupted benznidazole regimen.39 A regimen of intermittent benznidazole administration (i.e. an approximately 2.5-fold reduction in the total number of doses compared with a 30 day complete regimen) resulted in a significant decrease in the rate of treatment suspension, without an increase in treatment failure,45 thus supporting the hypothesis that fewer benznidazole doses may still be effective.

A beneficial outcome following an incomplete benznidazole regimen was further demonstrated by an improvement in parasite-specific polyfunctional T cells, which are reduced in T cell exhaustion46–48 and recovered after complete benznidazole treatment.20,27,47

The decrease in pro-inflammatory mediators and T cell activation following successful treatment further supports a beneficial effect of therapy even after interruption in treatment. An improvement in naive and central memory T cell levels within total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartments was observed post-treatment, regardless of the treatment regimen and serological outcome. This suggests that some degree of reduction in parasite load may inhibit parasite-induced alterations of T cell compartments in these subjects,35–37,49 while CD4+ T cell activation appeared as a sensitive tool to identify subjects in whom the infection will potentially be cleared. We found a strong association between decreased T. cruzi antibodies, decreased T cell activation and increased polyfunctional T cells. The restoration of functional T. cruzi-specific T cells along with a more resting status of the immune system in treated subjects might be also beneficial for efficient control of the parasite burden whilst avoiding tissue damage.15–17,20,22–25,27 In our study, disease progression was observed in two subjects who received incomplete treatment and they did not show any evidence of successful treatment outcome. Moreover, both of them presented with hypertension prior to therapy, which is a risk factor in disease progression.50

The high inflammatory response observed in subjects presenting with a cutaneous reaction during benznidazole therapy51 may be an additional factor contributing to parasite clearance. Effective treatment associated with immune-mediated adverse events, including hypersensitivity reactions involving the skin, has been described for patients with advanced melanoma who discontinued treatment with nivolumab plus ipilimumab.52 Furthermore, the status of the host immune system prior to treatment may be an important factor in the treatment outcome, indicating the immunological capacity of the host to augment antiparasitic drug effects.20,26,27 Among those who underwent an incomplete benznidazole regimen, subjects with successful treatment outcome exhibited higher proportions of memory T cells expressing IL-7R and lower levels of CD8+ T cells expressing PD-1, prior to treatment. IL-7R expression is critical for maintaining T cell memory and is severely diminished in exhausted T cells that express high levels of PD-1.46 In HIV-infected subjects who also showed signs of immune exhaustion, pre-therapy levels of T cell exhaustion were strongly associated with the time taken for viral load rebound after interruption of treatment.53,54 However, these measurements were less critical in subjects who received the full dose (in whom successful treatment was more dependable on polyfunctional T cells), as described in other studies.20

One limitation of our study is the observational design. Further evaluation of benznidazole in double-blind, randomized Phase III clinical trials will determine the optimum treatment regimen for chronic Chagas disease. The recent description of dormant parasites may establish the basis for new therapeutic schemes with individual doses given less frequently but over an extended length of treatment to target quiescent forms of the parasite, as recently described.55,56

In conclusion, these findings challenge the notion that the only possible outcome of an incomplete benznidazole regimen is treatment failure. The findings support the need for monitoring outcomes despite interruption in treatment. Whether adverse events are involved in treatment efficacy in an incomplete benznidazole regimen is yet to be explored.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the subjects at Hospital Eva Perón, Argentina, who provided blood samples; Placida Baz and Ariel Billordo from the INIGEM UBA-CONICET for their technical assistance; the Diagnostic Department of the Instituto Nacional de Parasitología ‘Dr. Mario Fatala Chaben’, Argentina, for serological tests; and Pablo Viotti and Laura Fichera for data management.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, USA (Award No. 110346 to S.A.L.); the National Fund for Science and Technology of Argentina (FONCYT PICT 2013-1631 to S.A.L.); the National Health Ministry of Argentina; and the Buenos Aires Province Health Ministry, Argentina. S.A.L., M.C.A. and J.B. are staff members of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), Argentina and M.D.C.E., M.A.N. and G.C. are CONICET fellows.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Table S1 and Figures S1 to S3 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1.WHO. Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis). 2018. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis).

- 2. Antinori S, Galimberti L, Bianco R. et al. Chagas disease in Europe: a review for the internist in the globalized world. Eur J Intern Med 2017; 43: 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministerio de Salud Argentina. Guías para la atención al paciente infectado con Trypanosoma cruzi (Enfermedad de Chagas). https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/guias-para-la-atencion-al-paciente-infectado-con-trypanosoma-cruzi-enfermedad-de-chagas.

- 4. Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B. et al. Side effects of benznidazole as treatment in chronic Chagas disease: fears and realities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2009; 7: 157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crespillo-Andújar C, Venanzi-Rullo E, López-Vélez R. et al. Safety profile of benznidazole in the treatment of chronic Chagas disease: experience of a referral centre and systematic literature review with meta-analysis. Drug Saf 2018; 41: 1035–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barclay CA, Cerisola JA, Lugones H. et al. Aspectos farmacológicos y resultados terapéuticos del benznidazol en el tratamiento de la infección chagásica. Prensa Med Argent 1979; 65: 239–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B. et al. Long-term cardiac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment: a nonrandomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 724–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fabbro DL, Streiger ML, Arias ED. et al. Trypanocide treatment among adults with chronic Chagas disease living in Santa Fe city (Argentina), over a mean follow-up of 21 years: parasitological, serological and clinical evolution. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2007; 40: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ciapponi A, Barreira F, Perelli L. et al. Fixed vs adjusted-dose benznidazole for adults with chronic Chagas disease without cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14: e0008529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bustamante JM, Craft JM, Crowe BD. et al. New, combined, and reduced dosing treatment protocols cure Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Infect Dis 2014; 209: 150–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rial MS, Arrúa EC, Natale MA. et al. Efficacy of continuous versus intermittent administration of nanoformulated benznidazole during the chronic phase of Trypanosoma cruzi Nicaragua infection in mice. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 1906–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perin L, Fonseca KdS, de Carvalho TV. et al. Low-dose of benznidazole promotes therapeutic cure in experimental chronic Chagas’ disease with absence of parasitism in blood, heart and colon. Exp Parasitol 2020; 210: 107834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cevey ÁC, Mirkin GA, Penas FN. et al. Low-dose benznidazole treatment results in parasite clearance and attenuates heart inflammatory reaction in an experimental model of infection with a highly virulent Trypanosoma cruzi strain. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2016; 6: 12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alvarez MG, Vigliano C, Lococo B. et al. Seronegative conversion after incomplete benznidazole treatment in chronic Chagas disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012; 106: 636–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tarleton RL. Chagas disease: a role for autoimmunity? Trends Parasitol 2003; 19: 447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dutra WO, Menezes CAS, Magalhães LMD. et al. Immunoregulatory networks in human Chagas disease. Parasite Immunol 2014; 36: 377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alvarez MG, Postan M, Weatherly DB. et al. HLA Class I-T cell epitopes from trans-sialidase proteins reveal functionally distinct subsets of CD8+ T cells in chronic Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008; 2: e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Natale MA, César GA, Alvarez MG. et al. Trypanosoma cruzi-specific IFN-γ-producing cells in chronic Chagas disease associate with a functional IL-7/IL-7R axis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12: e0006998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mateus J, Pérez-Antón E, Lasso P. et al. Antiparasitic treatment induces an improved CD8+ T cell response in chronic chagasic patients. J Immunol 2017; 198: 3170–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egui A, López MC, Gómez I. et al. Differential phenotypic and functional profile of epitope-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in benznidazole-treated chronic asymptomatic Chagas disease patients. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020; 1866: 165629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferreira LRP, Ferreira FM, Nakaya HI. et al. Blood gene signatures of Chagas cardiomyopathy with or without ventricular dysfunction. J Infect Dis 2017; 215: 387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Souza PEA, Rocha MOC, Menezes CAS. et al. Trypanosoma cruzi infection induces differential modulation of costimulatory molecules and cytokines by monocytes and T cells from patients with indeterminate and cardiac Chagas’ disease. Infect Immun 2007; 75: 1886–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pinto BF, Medeiros NI, Teixeira-Carvalho A. et al. CD86 expression by monocytes influences an immunomodulatory profile in asymptomatic patients with chronic Chagas disease. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vitelli-Avelar DM, Sathler-Avelar R, Dias JCP. et al. Chagasic patients with indeterminate clinical form of the disease have high frequencies of circulating CD3+CD16-CD56+ natural killer T cells and CD4+CD25high regulatory T lymphocytes. Scand J Immunol 2005; 62: 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laucella SA, Mazliah DP, Bertocchi G. et al. Changes in Trypanosoma cruzi-specific immune responses after treatment: surrogate markers of treatment efficacy. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: 1675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albareda MC, Natale MA, De RA. et al. Distinct treatment outcomes of antiparasitic therapy in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected children is associated with early changes in cytokines, chemokines, and T-cell phenotypes. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pérez-Antón E, Egui A, Thomas MC. et al. Immunological exhaustion and functional profile of CD8+ T lymphocytes as cellular biomarkers of therapeutic efficacy in chronic Chagas disease patients. Acta Trop 2020; 202: 105242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Viotti R, Vigliano C, Alvarez MG. et al. Impact of aetiological treatment on conventional and multiplex serology in chronic Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011; 5: e1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laucella SA, Postan M, Martin D. et al. Frequency of interferon-γ-producing T cells specific for Trypanosoma cruzi inversely correlates with disease severity in chronic human Chagas disease. J Infect Dis 2004; 189: 909–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooley G, Etheridge RD, Boehlke C. et al. High throughput selection of effective serodiagnostics for Trypanosoma cruzi infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008; 2: e316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bua J, Volta BJ, Velazquez EB. et al. Vertical transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi infection: quantification of parasite burden in mothers and their children by parasite DNA amplification. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012; 106: 623–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duffy T, Cura CI, Ramirez JC. et al. Analytical performance of a multiplex real-time PCR assay using TaqMan probes for quantification of Trypanosoma cruzi satellite DNA in blood samples. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7: e2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Castro Eiro MD, Alvarez MG, Cooley G. et al. The significance of discordant serology in Chagas disease: enhanced T-cell immunity to Trypanosoma cruzi in serodiscordant subjects. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qureshi H, Genescà M, Fritts L. et al. Infection with host-range mutant adenovirus 5 suppresses innate immunity and induces systemic CD4+ T cell activation in rhesus macaques. PLoS One 2014; 9: e106004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Albareda MC, Laucella SA, Alvarez MG. et al. Trypanosoma cruzi modulates the profile of memory CD8+ T cells in chronic Chagas’ disease patients. Int Immunol 2006; 18: 465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Albareda MC, Olivera GC, Laucella SA. et al. Chronic human infection with Trypanosoma cruzi drives CD4+ T cells to immune senescence. J Immunol 2009; 183: 4103–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dutra WO, Martins-Filho OA, Cançado JR. et al. Chagasic patients lack CD28 expression on many of their circulating T lymphocytes. Scand J Immunol 1996; 43: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sulleiro E, Silgado A, Serre-Delcor N. et al. Usefulness of real-time PCR during follow-up of patients treated with benznidazole for chronic Chagas disease: experience in two referral centers in Barcelona. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14: e0008067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murcia L, Carrilero B, Ferrer F. et al. Success of benznidazole chemotherapy in chronic Trypanosoma cruzi-infected patients with a sustained negative PCR result. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 35: 1819–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fernández ML, Marson ME, Ramirez JC. et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses in adult patients with Chagas disease treated with a new formulation of benznidazole. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2016; 111: 218–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fernández-Villegas A, Pinazo MJ, Marañón C. et al. Short-term follow-up of chagasic patients after benznidazole treatment using multiple serological markers. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pinazo M-J, Thomas M-C, Bustamante J. et al. Biomarkers of therapeutic responses in chronic Chagas disease: state of the art and future perspectives. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015; 110: 422–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Parrado R, Ramirez JC, de la Barra A. et al. Real-time PCR for the evaluation of treatment response in clinical trials of adult chronic Chagas disease: usefulness of serial blood sampling and qPCR replicates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 63: e01191-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Müller Kratz J, Garcia Bournissen F, Forsyth CJ. et al. Clinical and pharmacological profile of benznidazole for treatment of Chagas disease. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2018; 11: 943–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Álvarez MG, Ramírez JC, Bertocchi G. et al. New scheme of intermittent benznidazole administration in patients chronically infected with Trypanosoma cruzi: clinical, parasitological and serological assessment after three years of follow-up. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e00439-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 2011; 12: 492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alvarez MG, Bertocchi GL, Cooley G. et al. Treatment success in Trypanosoma cruzi infection is predicted by early changes in serially monitored parasite-specific T and B cell responses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10: e0004657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rodrigues V, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Laforge M. et al. Impairment of T cell function in parasitic infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8: e2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Menezes CAS, Rocha MOC, Souza PEA. et al. Phenotypic and functional characteristics of CD28+ and CD28− cells from chagasic patients: distinct repertoire and cytokine expression. Clin Exp Immunol 2004; 137: 129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guariento ME, Ramos MdC, Gontijo JA. et al. Chagas disease and primary arterial hypertension. Arq Bras Cardiol 1993; 60: 71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Salvador F, Sánchez-Montalvá A, Martínez-Gallo M. et al. Evaluation of cytokine profile and HLA association in benznidazole related cutaneous reactions in patients with Chagas disease. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 1688–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schadendorf D, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS. et al. Efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma who discontinued treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab because of adverse events: a pooled analysis of randomized Phase II and III trials. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 3807–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Muscatello A, Nozza S, Fabbiani M. et al. Enhanced immunological recovery with early start of antiretroviral therapy during acute or early HIV infection–results of Italian Network of ACuTe HIV InfectiON (INACTION) retrospective study. Pathog Immun 2020; 5: 8–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ghiglione Y, Trifone C, Salido J. et al. PD-1 expression in HIV-specific CD8+ T cells before antiretroviral therapy is associated with HIV persistence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 80: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sánchez-Valdéz FJ, Padilla A, Wang W. et al. Spontaneous dormancy protects Trypanosoma cruzi during extended drug exposure. Elife 2018; 7: e34039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bustamante JM, Sanchez-Valdez F, Padilla AM. et al. A modified drug regimen clears active and dormant trypanosomes in mouse models of Chagas disease. Sci Transl Med 2020; 12: eabb7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.