Abstract

BACKGROUND

Letters of recommendation (LORs) are historically an important, though subjective, component of the neurosurgery residency application process. Standardized LORs (SLORs) were introduced during the 2020 to 2021 application cycle. The intent of SLORs is to allow objective comparison of applicants and to reduce bias.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the utility of SLORs during this application cycle. We hypothesized that “grade inflation” and poor inter-rater reliability, as described by other specialties using SLORs, would limit the utility of SLORs in their current form.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study analyzed all SLORs submitted to a single neurosurgery residency program over the 2020 to 2021 cycle. Data from 7 competency domains and the overall rating were recorded and stratified by academic category of letter writer. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated using Krippendorff's alpha.

RESULTS

One or more SLORs was submitted as part of 298 of 393 applications (76%). Approximately 58.3% of letters written by neurosurgery chairpersons rated a given applicant as being within the top 5% across all competencies. Approximately 44.4% of program director letters similarly rated applicants as amongst the top 5%, while 73.2% and 81.4% of letters by other neurosurgeons and general surgery evaluators, respectively, rated applicants in the top 5%. Inter-rater reliability was poor (<0.33) in all rating categories, including overall (α = 0.18).

CONCLUSION

The utility of the first iteration of SLORs in neurosurgery applications is undermined by significant “grade inflation” and poor inter-rater reliability. Improvements are necessary for SLORs if they are to provide meaningful information in future application cycles.

Keywords: Letter of recommendation, Neurosurgery residency match, Standardized letter of recommendation, Medical students

ABBREVIATIONS

- EM

Emergency medicine

- ERAS

Electronic Residency Application Service

- GS

general surgery

- LOR

letter of recommendation

- MSPE

Medical Student Performance Evaluation

- NC

neurosurgery chairperson

- NLOR

narrative letter of recommendation

- NPD

neurosurgery program director

- SLOR

standardized LOR

- SNS

Society of Neurological Surgeon

- ON

other neurosurgeon

- USMLE

United States Medical Licensing Examination

The 2020 to 2021 neurosurgery residency application cycle was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. To prioritize the safety of medical students and adhere to public health standards, the Society of Neurological Surgeons (SNS) restricted external student rotations and transitioned to virtual interviews and recruitment.1 The SNS also developed standardized letters of recommendation (SLOR) for neurosurgical and general surgery (GS) faculty completion. These changes were designed to standardize applicant evaluation on key metrics.1

Narrative letters of recommendation (NLORs) and the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) are considered by neurosurgery program directors (NPDs) to be the most important, reliable components of the residency application.2,3 NLORs can, however, be difficult to interpret. Writers strive to support applicants whilst simultaneously preserving their objectivity.2 NLORs fail to offer consistent comparisons between applicants, are prone to gender bias and poor inter-rater reliability, and are poorly predictive of clinical performance.4-6 NLORs may also contain “coded” phrases, which can be misinterpreted. SLORs have been utilized in residency applications by emergency medicine, dermatology, pediatrics, orthopedics, and otolaryngology to provide objectivity to evaluations and improve inter-reviewer consistency.7-13 SLORs reportedly offer eased interpretation, reduced writing/reviewing time, reduced bias, and purportedly improved inter-rater reliability.7,14

The purpose of this study is to evaluate patterns of usage of the SNS SLOR for neurosurgical residency candidates, and to assess the precision and score distributions of submitted evaluations. Based on our experience reviewing applications during this match cycle, we hypothesize that these new letters suffer from the “grade inflation” and poor inter-rater reliability encountered by other specialties using SLORs.13,15,16

METHODS

Study Design and Approvals

A cross-sectional study to evaluate SNS SLOR templates was designed and exempted by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center IRB (#202454). The requirement for written consent was waived.

Participants

All applicant LORs to a single Neurosurgery residency program submitted for the 2021 National Resident Matching Program via the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) were screened. Each application had between 0 and 4 SLORs sometimes with accompanying NLORs. Applications without SLORs were excluded.

Data Collection

All available applicant demographics and characteristics were extracted from ERAS applications including gender (male or female, determined by LOR pronoun usage), foreign medical graduate status (yes/no), Alpha Omega Alpha society member (yes/no), Gold Humanism Honor Society member (yes/no), current/previous resident (yes/no), PhD status (yes/no), number of publications, number of research, work, and volunteer activities, and Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE) quartile if available. MSPE breakdown was approximated to the highest-spanned quartile.

The SLOR template (Supplemental Figure 1) contains 7 competency domains: patient care, medical knowledge, procedural/technical skill, research, initiative/drive, professionalism and communication, coachability, and an overall percentile rating comparing applicants to others over the last 5 yr. Evaluators assigned 1 of 6 scores in each domain: top 1%, 2% to 5%, 6% to 10%, 11% to 25%, 26% to 50%, and bottom 50%. Neurosurgeon letter writers also evaluated applicants’ anticipated “level of guidance required” domain, assigning scores of “less-than,” “similar-to,” and “more-than” peers. Letter writers were divided into neurosurgery chairpersons (NCs), NPDs, and other neurosurgeons (ONs). During this unique application cycle, applicants were encouraged to include one letter from a GS mentor. The GS SLOR (Supplemental Figure 2) was similar but removed the research rating and replaced “coachability” with “work ethic.” The overall rating also compared the applicant to their immediate peers. All data were manually extracted and stored in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt).17

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of the applicant pool and SLOR inter-rater reliability were assessed at the level of the applicant, while descriptive analyses of ratings by letter writer type were performed at the level of individual letters.

Inter-rater reliability for each competency domain was computed by Krippendorf's alpha using the R Kripp.boot package.18 We employed the bootstrap approach given the unknown α-distribution to generate 99% CIs.18,19 Sensitivity analysis was repeated excluding any non-neurosurgeon letters. Levels of agreement were defined a priori as unreliable (α < 0.667), tentatively reliable (0.667 <= α< 0.800), and reliable (α > = 0.800).19

We coded “overall” competency ratings on a 6-point Likert scale (6 = “top 1%”, 1 = “bottom 50%”) and the “guidance” ratings as a 3-point Likert scale (3 = “less-than”, 2 = “similar-to”, 1 = “more-than” peers). We performed Kruskal-Wallis H tests on the Likert coded ratings to determine if ratings differed between the 3 neurosurgeon rater types using the Kruskal-Wallis MATLAB function and conducted a post hoc analysis using Dunn's test through the MATLAB multcompare function. Analysis was performed using R Studio (R 4.0.3, RStudio, Boston, Massachusetts) and MATLAB (MATLAB [9.5 R2018B], MathWorks Inc, Natick, Massachusetts).

RESULTS

Of 393 applications, 47 (12%) had 1 SLOR, 68 (17%) had 2, 115 (29%) had 3, and 68 (17%) had 4. Complete applicant characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 797 SLORs were submitted for these 298 applicants. Of these, 600 (75.2%) were written by neurosurgeons, including 258 (32.4%) written by NCs and 129 (16.2%) written by NPDs.

TABLE 1.

Applicant Demographics and Letter Characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Applicants | |

| USMLE Step 1 score | Mean: 241.8 SD: 14.5 |

| Male | 220 (74%) |

| Foreign Medical Graduate | 34 (11%) |

| PhD (or MD/PhD candidate) | 30 (10%) |

| Experiences | |

| Research | Median: 5 IQR: 4 |

| Work | Median: 3 IQR: 3 |

| Volunteer | Median: 6 IQR: 5 |

| Publications | Median: 6 IQR: 9 |

| MSPE quartile total: | 156 (100%) |

| Top 25% | 76 (49%) |

| 25%-50% | 49 (31%) |

| 50%-75% | 19 (12%) |

| Bottom 25% | 12 (8%) |

| Letters | |

| Total SLORs: | 797 (100%) |

| General surgeon SLORs: | 195 (25%) |

| Neurosurgery chairman SLORs: | 258 (32%) |

| Neurosurgery PD SLORs: | 129 (16%) |

| Other neurosurgeon SLORs: | 213 (27%) |

| Untyped SLORs: | 2 (0.3%) |

USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Exam; MSPE, Medical Student Performance Evaluation; SLOR, standardized letter of recommendation; PD, program director.

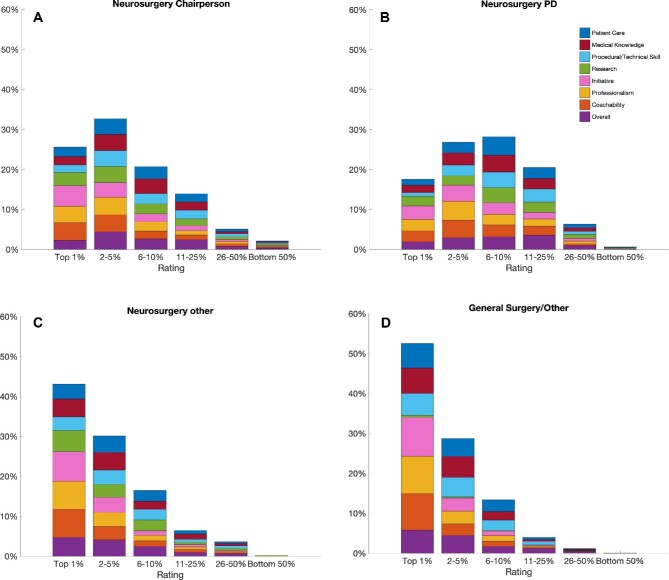

Across all competency domains, NCs assigned a rating of “top 1%” 25.6% of the time, “2% to 5%” 32.7% of the time, “6% to 10%” 20.7% of the time, and “11% to 25%” 13.9% of the time (Figure 1A). NPDs assigned a “top 1%” rating 17.6% of the time, “2% to 5%” 26.8% of the time, “6% to 10%” 28.2% of the time, and “11% to 25%” 20.5% of the time (Figure 1B). Across all competency domains, ONs assigned “top 1%” 43.1% of the time, “2% to 5%” 30.1% of the time, “6% to 10%” 16.5% of the time, and “11% to 25%” 6.5% of the time (Figure 1C). GS letters assigned a rating of “top 1%” 52.6% of the time, “2% to 5%” 28.8% of the time, and “6% to 10%” 13.4% of the time across all competencies (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

A-D, Rating distributions across all SLORs by letter writer type. A, Percentage of ratings (top 1%, 2%-5%, 6%-10%, 11%-25%, 26%-50%, and bottom 50%) assigned by neurosurgery chairpersons in each of the 8 competency domains across all SLORs. Patient care (blue), medical knowledge (red), procedural/technical skill (cyan), research (green), initiative (pink), professionalism (yellow), coachability (orange), overall (purple). B, Same as A for neurosurgery program directors. C, Same as A for other neurosurgeons. D, Same as A for general surgeons.

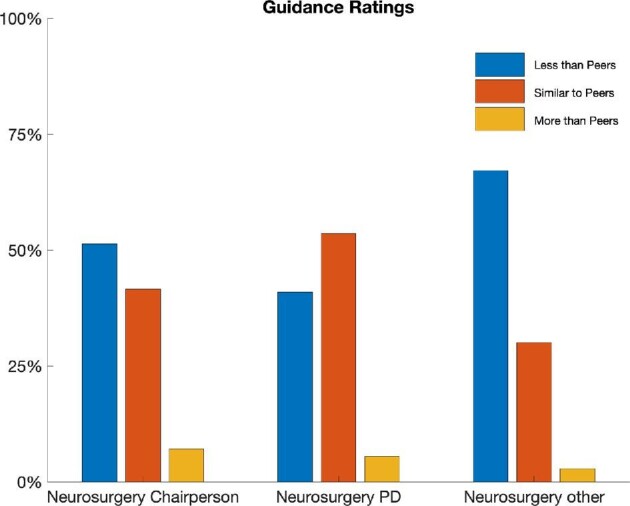

On level of guidance evaluation, 51.4% of NC letters stated the applicant required less guidance than peers, 41.6% stated similar guidance, and 7.1% more guidance than their peers (Figure 2). NPD letters noted 40.9% of applicants required less guidance, 53.5% similar guidance, and 5.5% more guidance than their peers. ONs evaluated 67.1% of applicants as requiring less guidance than their peers, 30.1% similar guidance, and 2.8% more guidance than their peers.

FIGURE 2.

Rating distribution in the “guidance” competency across all SLORs by letter writer type. Percentage of ratings assigned by neurosurgery chairpersons, neurosurgery program directors, and other neurosurgeons in the “guidance” competency across all SLORs. Ratings: “less than peers” (blue), “similar to peers” (orange), “more than peers” (yellow).

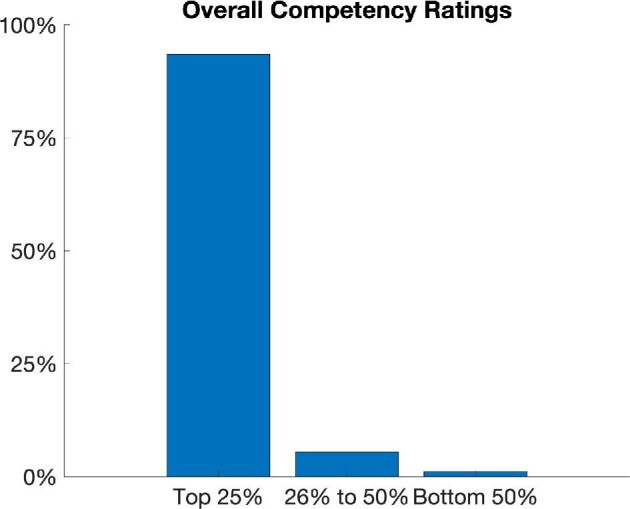

“Overall” ratings by all letter writers were pooled. 93.5% of letters rated applicants within the top 25%, 5.4% between 25% and 50%, and 1.1% within the bottom 50% (Figure 3). “Overall” ratings assigned by letter writers were coded on a 6-point Likert scale (6 = “top 1%”, 1 = “bottom 50%”). NC ratings (mean = 4.32) and NPD ratings (mean = 4.05) were lower than ratings by ONs (mean = 4.88). There was a significant relationship between scores and neurosurgeon rater type (Kruskal-Wallis H test, P = 5.82e–10). Post hoc analysis demonstrated NC and NPDs’ overall ratings were similar (P = .0873) but both were significantly lower than ONs’ ratings (P = 4.24e–6 and P = 3.00e–9, respectively).

FIGURE 3.

Rating distribution for “overall” competency across all letter writers.

Anticipated “guidance” required was coded on a 3-point Likert scale (3 = “less than peers”). NC ratings (mean = 2.44) and NPD ratings (mean = 2.35) were lower than ratings by ONs (mean = 2.64). Kruskal-Wallis H test significant difference between 3 neurosurgeon rater categories (P = 6.6836e–6). Post hoc analysis redemonstrated NC and NPDs’ ratings were statistically similar (P = .260) but were lower than ONs’ ratings (P = .001 and P = 1.41e–5, respectively).

Inter-rater reliability for each of the competency domains was estimated using Krippendorf's alpha (Table 2). No competency achieved strong (α >= 0.800) or tentative reliability (α >= 0.667). Inter-rater reliability was greatest for research (α = 0.31, 99% CI 0.23, 0.39) and lowest for procedural/technical skill (α = 0.12, 99% CI 0.03, 0.21). Inter-rater reliability was similarly poor when considering only neurosurgeon letters (research: α = 0.31, 99% CI 0.23, 0.39; anticipated guidance: α = 0.29, 99% CI 0.11, 0.44).

TABLE 2.

Analysis of Inter-rater Reliability

| Competency | Krippendorff's alpha (All) | 99% CI (All) | Krippendorff's alpha (neurosurgeons) | 99% CI (neurosurgeons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.1854 | [0.1039, 0.2629] | 0.2618 | [0.1773, 0.3434] |

| Patient care | 0.1484 | [0.0640, 0.2406] | 0.1823 | [0.0926, 0.2725] |

| Medical knowledge | 0.1766 | [0.0891, 0.2606] | 0.2245 | [0.1339, 0.3130] |

| Procedural/technical | 0.1206 | [0.0299, 0.2149] | 0.1639 | [0.0649, 0.2654] |

| Research | 0.3117 | [0.2300, 0.3882] | 0.3115 | [0.2327, 0.3846] |

| Initiative | 0.1722 | [0.0731, 0.2630] | 0.2509 | [0.1642, 0.3357] |

| Professionalism | 0.1328 | [0.0395, 0.2210] | 0.2069 | [0.1054, 0.2970] |

| Coachability | 0.1279 | [0.0345, 0.2194] | 0.1929 | [0.1066, 0.2721] |

| Anticipated guidance required | – | – | 0.2877 | [0.1104, 0.4402] |

Top: Krippendorf's alpha values and confidence intervals for each of the 8 competency domains demonstrating inter-rater reliability across all letter writers (columns 2 and 3) and neurosurgeon letter writers exclusively (columns 4 and 5). Bottom: Krippendorf's alpha value and confidence interval for the “peer guidance” competency demonstrating inter-rater reliability across neurosurgeon letter writers.

DISCUSSION

Objective measures of residency applicants are desired in the current medical education context.2 LORs were elevated in importance during the COVID-19 pandemic, with applicants barred from in-person interviews and rotations. The SNS’ transition to SLORs is therefore well aligned with neurosurgery programs’ needs. Unfortunately this cross-sectional study of SLOR forms for the 2020 to 2021 neurosurgery match highlights several shortcomings: (1) one-third of applicants had no SLORs and less than half had at least 3, (2) letter writers almost exclusively rated applicants in the top 1% to 10% across all metrics, and (3) all metrics demonstrated poor inter-rater reliability. While these standardized templates and rating scales were well-intentioned, they contributed little meaningful information during this application cycle and require re-evaluation prior to the next cycle.

Key Results

We observed substantial “grade inflation” in all rating categories amongst all classes of evaluators. Neurosurgery faculty (excluding NPDs and NCs) rated 73.2% of applicants as amongst the top 5% of neurosurgery applicants over the past 5 yr. While NCs and PDs were marginally less skewed in their evaluations, 40% to 60% of all their ratings were in the top fifth percentile of applicants evaluated over the last 5 yr. This claim is mathematically impossible. Importantly, this finding is not an artifact of multiple complimentary letters for the same applicants, with only 9% of applicants receiving more than one letter from a NC. GS letter writers were further laudatory, with 81.4% of letters placing applicants in the top 5%, albeit in comparison to the broader pool of applicants’ “peers.” This is an example of the “Lake Wobegon effect”, a psychological tendency to assume that most people are above average.20

“Grade inflation” in SLORs is not unique to neurosurgery applications. Emergency Medicine adopted SLORs in 1997, and subsequent evaluation demonstrates profound inflation of evaluations on SLORs over the subsequent 15 yr.16 Specifically, in one application cycle, 83% of applicants were ranked as “above their peers'' and 40% of applicants among the top decile.15 Inflation was correlated with less experienced letter writers, and a lack of experience in this type of letter writing may have influenced the inflation noted in neurosurgery SLOR roll-out.21 Similar inflation is seen in the more recent otolaryngology and orthopedics literature.13,22 Inflation was also seen in evaluating the level of guidance needed by an applicant, with NPDs being the only category of raters to not assess the majority of applicants as requiring less guidance than their peers. These trends mimic the results seen in retrospective analysis of other fields using SLORs, while also emphasizing evaluators most frequently in contact with large numbers of medical students and residents provide the most balanced feedback of applicants.7,13

In addition to rating inflation in SLORs, we found that inter-rater reliability was poor across all competencies (including overall), even when considering only neurosurgeon-written letters. NPDs and department chairs provide statistically similar ratings in comparison to other neurosurgical faculty, suggesting that applicant evaluation experience improves reliability and decreases inflation. While some variance is likely desired in these letters to give a holistic impression of the applicant, lack of reliability as we observed is likely more indicative of a lack of precision rather than meaningful differences in rater perspectives. Two disparate scores may provide some insight, but most likely causes the reader to disregard the rating scales in favor of the NLOR. Experience in other fields transitioning to SLORs has been mixed, with initial evaluations of orthopedics SLORs showing poor inter-rater reliability, Otolaryngology literature suggesting good reliability, and Emergency medicine (EM) literature suggesting significant improvements in inter-rater reliability of SLORs in comparison to NLORs.7,13,23 The similar average overall ratings of NPD and NCs could be a function of experience in evaluating and working with medical students of varying skill levels, as EM SLOR literature suggests that letter writer experience is negatively correlated with inflation.21 Further, as applicants were free to choose neurosurgery faculty and GS faculty, NPDs and chairs were likely the only letter writers with exposure to every applicant and thus were best positioned to contextualize a given applicant amongst the overall applicant pool.

Interpretation

“Grade inflation” and poor inter-rater reliability limited the utility of neurosurgical SLORs. Neurosurgery SLORs do, however, have significant potential. Consideration should be made to restricting SLORs to NCs and NPDs, who most reasonably are able to rank medical students relative to their peers. Relying on an explicitly defined metric such as a 1 to 5 scale with 1 “performs admirably in this domain, unlikely to see someone of this caliber again in the next 10 years”, and 5 “Does not distinguish themselves” could help raters more effectively use the full range of scores. Strict definitions of ratings force evaluators towards central scores rather than consistent inflation. Moves towards the center may improve reliability but must balance utility as perfect agreement is not ideal for differentiating candidates. Broader tiers of more evenly distributed categories as has been trialed in other fields may be useful, as evaluators are reticent to rank a student in the bottom half of any category.15 To that point, we observed somewhat improved inter-rater reliability when the number of possible ratings was limited to 3, in the amount of guidance required relative to peers. Therefore, fewer, well-defined ratings may improve reliability while maintaining the ability to meaningfully differentiate applicants. In polls of surgical faculty, NLORs have traditionally been able to assist evaluators in stratifying residents into an upper and lower half; it is reasonable to expect an SLOR to at the very least improve on this interpretability.24 Improved inter-rater reliability while substantively differentiating applicants is an attainable goal, achievable by adjusting and better defining the rating scale; but, improvements may also be made through consistent utilization over time.

Limitations

It is important to note that this is the first year of implementation of SLORs in neurosurgery, and thus our findings are limited by temporality. One important consideration during this unique application cycle is the limitations on away rotations imposed during COVID-19, and the possible biases these reviewers might have towards their home-institution students as a driver of inflation. Additionally, these reflect a single institution's applicant pool, although historically this institution receives >90% of neurosurgery applications. Notably, it is unknown whether institutions actually used the templates in rank decisions or whether they were ignored in favor of an accompanying NLOR, and we lack an objective metric to correlate with the SLOR ratings to establish outside validity. Finally, because of the blinded nature of our evaluation, we were unable to correlate SLOR ratings with internal objective metrics such as rank list status either at our institution or that of the letter writers.

CONCLUSION

In this cross-sectional retrospective analysis of SLORs submitted to a neurosurgical residency program, we observed significant rating inflation across all metrics. Additionally, SLORs were undermined by poor inter-rater reliability. Targeted changes to SLORs for future application cycles should be considered to improve their utility in reliably differentiating neurosurgical residency applicants. The goal of creating a means of objective and unbiased comparison between candidates is laudable, and critical review of this initial effort should guide future iterations of the SLOR in neurosurgery.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding or financial support.

Disclosures

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article. Dr Yengo-Kahn holds a compensated position on the scientific advisory board of BlinkTBI. Dr Chitale receives research grants from Medtronic Cerenovus, and Microvention. He also serves as a consultant for Medtronic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

REDCap, the online data management tool used for this study is supported by NCATS/NIH (UL1 TR000445). Pamela Lane provided invaluable administrative support for this work.

Contributor Information

Michael J Feldman, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Alexander V Ortiz, School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Steven G Roth, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Robert J Dambrino, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Aaron M Yengo-Kahn, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Rohan V Chitale, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Lola B Chambless, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Supplemental Figure 1. Neurosurgery standardized letter of recommendation form. From https://www.societyns.org/medical-students/external-medical-student-rotations; Courtesy of The Society of Neurological Surgeons.

Supplemental Figure 2. General surgery standardized letter of recommendation form. From https://www.societyns.org/medical-students/external-medical-student-rotations; Courtesy of The Society of Neurological Surgeons.

REFERENCES

- 1. COVID-19 Medical Student Guidance - societyns.org. https://www.societyns.org/medical-students/external-medical-student-rotations. Accessed February 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Field NC, Gullick MM, German JW. Selection of neurological surgery applicants and the value of standardized letters of evaluation: a survey of United States program directors. World Neurosurg. 2020;136:e342-e346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al Khalili K, Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris Set al. Programs selection criteria for neurological surgery applicants in the United States: a national survey for neurological surgery program directors. World Neurosurg. 2014;81(3-4):473-477.e2.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Messner AH, Shimahara E.. Letters of recommendation to an otolaryngology/head and neck surgery residency program: their function and the role of gender. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(8):1335-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeZee KJ, Thomas MR, Mintz M, Durning SJ.. Letters of recommendation: rating, writing, and reading by clerkship directors of internal medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyse TD, Patterson SK, Cohan RHet al. Does medical school performance predict radiology resident performance? Acad Radiol. 2002;9(4):437-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perkins JN, Liang C, McFann K, Abaza MM, Streubel S-O, Prager JD.. Standardized letter of recommendation for otolaryngology residency selection. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(1):123-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu AC, Gu JT, Wong BJF.. Objective measures and the standardized letter of recommendation in the otolaryngology residency match. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(3):603-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garmel GM, Grover CA, Quinn Aet al. Letters of recommendation. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(3):405-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang RF, Zhang M, Alloo A, Stasko T, Miller JE, Kaffenberger JA.. Characterization of the 2016–2017 dermatology standardized letter of recommendation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(3):26-29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bajwa NM, Yudkowsky R, Belli D, Vu NV, Park YS.. Validity evidence for a residency admissions standardized assessment letter for pediatrics. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(2):173-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Samade R, Scharschmidt TJ, Goyal KS. Use of standardized letters of recommendation for orthopaedic surgery residency applications: a single-institution retrospective review. J Bone Jt Surg. 2020;102(4):e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang HP, Robertson DM, Levine WN, Lieberman JR.. Evaluating the standardized letter of recommendation form in applicants to orthopaedic surgery residency. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(19):814-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prager JD, Perkins JN, McFann K 3rd, Myer CM, Pensak ML, Chan KH. Standardized letter of recommendation for pediatric fellowship selection. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):415-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Love JN, DeIorio NM, Ronan-Bentle Set al. Characterization of the council of emergency medicine residency directors’ standardized letter of recommendation in 2011-2012. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(9):926-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hegarty CB, Lane DR, Love JNet al. Council of emergency medicine residency directors standardized letter of recommendation writers’ questionnaire. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):301-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gruszczynski MPP. An R Package for Performing Bootstrap Replicates of Krippendorff's alpha on Intercoder Reliability Data. GitHub. https://github.com/MikeGruz/kripp.boot Accessed February 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. SAGE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berwick DM. Measuring physicians’ quality and performance: adrift on Lake Wobegon. JAMA. 2009;302(22):2485-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beskind DL, Hiller KM, Stolz Uet al. Does the experience of the writer affect the evaluative components on the standardized letter of recommendation in emergency medicine? J Emerg Med. 2014;46(4):544-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kominsky AH, Bryson PC, Benninger MS, Tierney WS. Variability of ratings in the otolaryngology standardized letter of recommendation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(2):287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Girzadas DV Jr, Harwood RC, Dearie J, Garrett S. A comparison of standardized and narrative letters of recommendation. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(11):1101-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rajesh A, Rivera M, Asaad Met al. What are we really looking for in a letter of recommendation? J Surg Educ. 2019;76(6):e118-e124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.