Abstract

Capsicum spp. (hot peppers) demonstrate a range of interesting bioactive properties spanning anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities. While several species within the genus are known to produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), AMP sequence mining of genomic data indicates this space remains largely unexplored. Herein, in silico AMP predictions were paired with peptidomics to identify novel AMPs from the interspecific hybrid ghost pepper (Capsicum chinense × frutescens). AMP prediction algorithms revealed 115 putative AMPs within the Capsicum chinense genome of which 14 were identified in the aerial tissue peptidome. PepSAVI-MS, de novo sequencing, and complementary approaches were used to fully molecularly characterize two novel AMPs, CC-AMP1 and CC-AMP2, including elucidation of post-translational modifications and disulfide bond connectivity. Both CC-AMP1 and CC-AMP2 have little homology with known AMPs and exhibit low μM antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. These findings demonstrate the complementary nature of peptidomics, bioactivity-guided discovery, and bioinformatics-based investigations to more fully characterize plant AMP profiles.

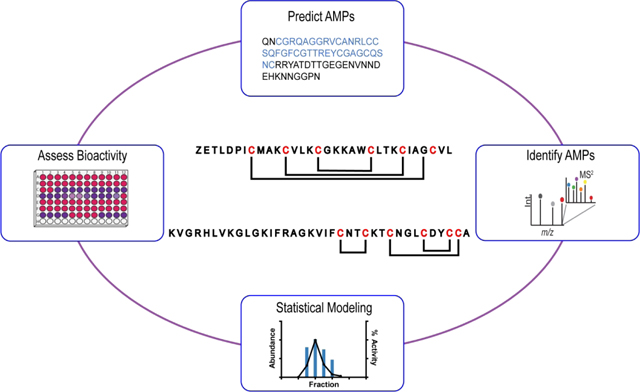

Graphical Abstract

Ghost pepper is an interspecific hybrid of Capsicum chinense and Capsicum frutescens (Capsicum chinense × frutescens)1 that originated in the northeast region of India. Once considered the hottest pepper in the world, the ghost pepper has been used medicinally for a variety of ailments including gastritis, arthritis, and chronic indigestion.2 Capsaicinoids, including capsaicin, are well documented as the major bioactive constituents in hot peppers.3–5 Despite a historical focus on small molecule bioactive components, species within the Capsicum genus are known to produce at least 10 known antimicrobial peptides (AMPs),6 including ɣ-Thionin,7 found in C. chinense.

Increased throughput for revealing AMPs can be realized via genome mining and in silico prediction strategies by leveraging increasingly available genomic data. Plant AMPs are often expressed as a precursor protein containing an N-terminal signal peptide (and in some cases a C-terminal pro-domain) that is cleaved to produce the mature AMP.8 Mature AMPs are generally cysteine-rich and contain highly conserved cysteine motifs which facilitate AMP family classification (e.g. defensins, thionins, etc.).8 Many AMP prediction workflows utilize SignalP 5.0,9 a deep neural network that predicts and cleaves N-terminal signal peptides in silico, suggesting a mature sequence and generating a focused set of peptides for further analysis. Cysmotif Searcher10 is used to reveal cysteine motifs within the SignalP output and sort results into AMP families. Recently, in silico prediction applied to 1267 plant transcriptomes identified 50–150 AMPs per transcriptome,11 highlighting the potential to reveal putative AMPs in silico. While powerful, this approach used alone is limited in the ability to 1) reveal novel classes of AMPs, 2) predict peptide accumulation, and 3) confirm mature AMP structure or relevant bioactivity.

The complementarity of antimicrobial bioassays and MS-based profiling can help address these limitations. In vitro antimicrobial assays provide direct evidence of AMP bioactivity and can reveal novel AMPs which were not predicted in silico. Mass spectrometry can be employed to profile AMPs within extracts, correlate bioactivity to peptide abundance to identify likely contributors to activity12, provide primary sequences of peptides, and reveal processing and post-translational modifications which may be required for bioactivity and stability.

Herein, in silico prediction, proteomics, and PepSAVI-MS12 were leveraged to identify and characterize novel AMPs from ghost pepper. A total of 115 putative AMP species were predicted in the C. chinense genome via the SignalP and Cysmotif Searcher workflow. Bottom-up proteomics identified 15 putative AMPs (14 of which were predicted in silico) within an aerial tissue C. chinense × frutescens peptide library. In addition to the putative AMPs detected via bottom-up proteomics, two novel AMPs, CC-AMP1 and CC-AMP2, were identified and molecularly characterized with little homology to known AMPs. Both demonstrated low μM 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) values against Gram-negative bacteria including the multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

AMP Prediction.

Because ghost pepper is more closely related to C. chinense than C. frutescens, the C. chinense reference genome was used as a proxy for analysis of the interspecies hybrid.1 SignalP 5.0 was used to predict and cleave signal peptides from the translated proteome in silico (Table S1, Supporting Information) and the remaining processed peptides were analyzed with Cysmotif Searcher. A total of 115 sequences were identified as potential AMPs (Table S2, Supporting Information), highlighting C. chinense as a rich source of antimicrobial peptides. The known defensin ɣ-Thionin7 is observed within the predicted AMPs, although the reported sequence of ɣ-Thionin indicates cleavage of a C-terminal pro-domain, a processing event not captured within the prediction workflow.

Predicted AMPs were sorted into seven families including hevein-like, defensin, lipid transfer protein, snakin, α-hairpinin, other (peptides with known cysteine motifs not belonging to a major AMP family), and cysteine-rich (peptides containing additional cysteines outside of an identified cysteine motif), the majority (38%) falling into this last family (Table 1). While AMPs identified with known cysteine motifs are homologous to well-known AMP families, those classified into the cysteine-rich category have the potential to carry novel cysteine motifs, possibly from unknown AMP families, highlighting C. chinense × frutescens as an intriguing species for analysis.

Table 1.

A total of 115 AMPs among 7 families are predicted in Capsicum chinense, highlighting it as a rich source of AMPs. Of these, 15 are detected in the C. chinense × frutescens (Ghost pepper) peptidome.

| AMP class | Predicted in C. chinense genome | Detected in ghost pepper peptidome |

|---|---|---|

| Hevein-like | 5 | 2 |

| Defensin | 25 | 8 |

| Lipid transfer protein | 12 | 2 |

| Snakin | 14 | 0 |

| Cysteine rich | 44 | 3 |

| α-Hairpinin | 14 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 0 |

Detection of Predicted AMPs.

Proteomics analysis of a reduced, alkylated, and trypsin digested C. chinense × frutescens peptide library identified 15 previously uncharacterized AMPs with unique peptide assignments, including defensins, hevein-like peptides, lipid transfer proteins, and cysteine rich (Table S3, Supporting Information). These results illustrate the power of in silico AMP prediction for rapidly identifying putative AMPs within a peptidome extract.

Interestingly, one putative defensin was detected that was not predicted in silico. However, sequence alignment with detected defensins reveals a shared cysteine motif (Figure S1, Supporting Information), and this protein appears to contain an acidic C-terminal region characteristic of class II defensins found primarily in the Solanaceae family (containing Capsicum spp.), which balances the positive charge of the defensin domain and is cleaved from the mature AMP.13 No tryptic peptides were identified from the C-terminal region (Table S3, Supporting Information), indicating likely cleavage to the mature AMP. Analysis of the SignalP output from the prediction workflow revealed this protein was filtered out during the SignalP step because it did not contain an N-terminal signal peptide (Table S1, Supporting Information). This finding highlights a key limitation in relying solely on current SignalP and Cysmotif Searcher predictions, as AMPs which do not carry recognizable signal peptides are excluded from further analysis.

Bioactivity of Peptide Library.

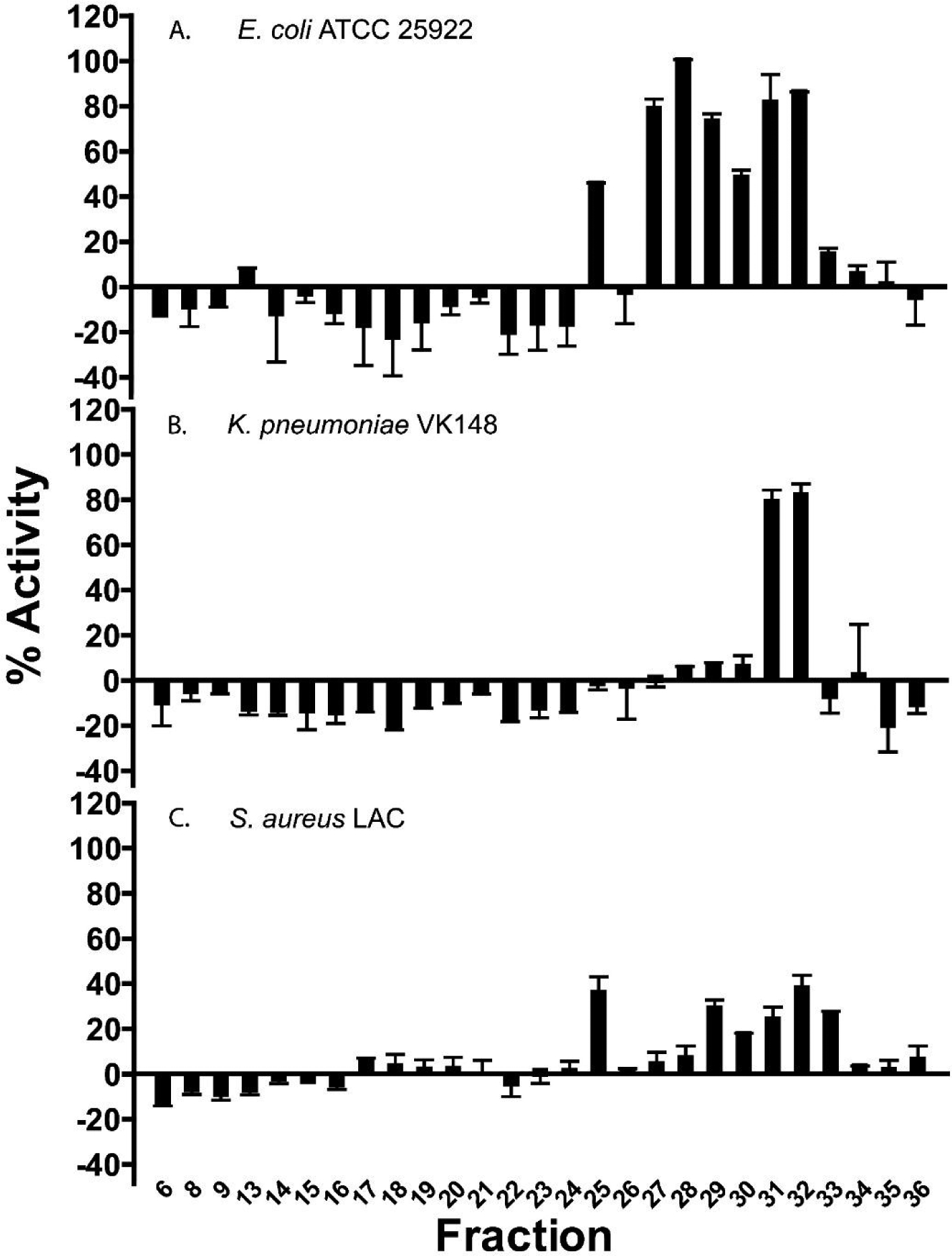

Despite the efficiency of in silico prediction and proteomics profiling of AMPs, additional experiments are needed to examine the activity of C. chinense × frutescens AMPs. The C. chinense × frutescens peptide library was screened for antimicrobial activity against gram-negative E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae VK148, and gram-positive S. aureus LAC. Robust antimicrobial activity greater than ~50% was observed against gram-negative E. coli in fractions 27–32 and K. pneumoniae in fractions 31–32, however negligible activity was observed against S. aureus (Figure 1). These fractions were further examined to determine contributors to bioactivity.

Figure 1.

Bioactivity assays screened against (A) E. coli ATCC 25922, (B) K. pneumoniae VK148, and (C) S. aureus LAC. Reversed-phase fractions 31–32 showed high activity against both E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Fractions 27–30 showed high activity against E. coli, with no activity against K. pneumoniae. There was little to no observed activity against Gram-positive S. aureus. Error bars are shown as ± standard deviation of three replicates.

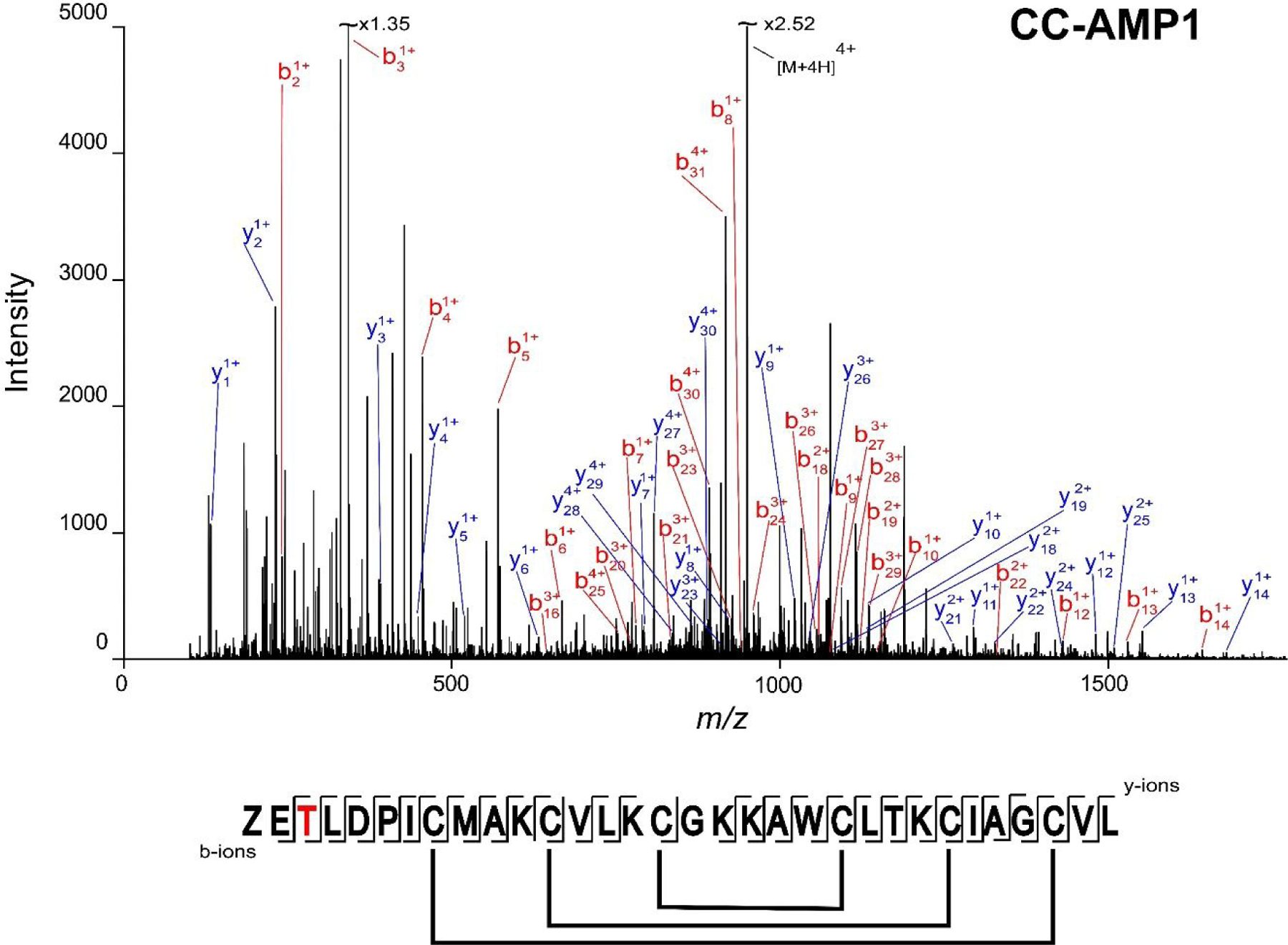

Molecular Characterization of CC-AMP1.

LC-MS analysis revealed a primary peptidyl component (3445.68 Da), deemed CC-AMP1, accompanied by minor species (3461.69 Da, 3477.67 Da, and 3493.66 Da) in fraction 32 (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Mass differences in multiples of +16 Da suggest that the minor components are oxidation states of CC-AMP1. The oxidations likely occurred during sample processing, especially given their relatively low abundance. Reduction with dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylation with iodoacetamide (IAM) produced a 348.17 Da mass shift (to 3793.85 Da) corresponding to the presence of three disulfide bonds. De novo sequencing via collision induced dissociation (CID) of the reduced and alkylated peptide yielded the full sequence (Figure 2): ZETLDPICMAKCVLKCGKKAWCLTKCIAGCVL, where Z represents pyroglutamic acid. Interestingly, this sequence is a variation of the predicted C. chinense AMP A0A2G3BCB3 (Table S2, Supporting Information) which was detected in the bottom-up proteomic analysis (Table S3, Supporting Information). In CC-AMP1, the N-terminal glutamine is modified to a pyroglutamic acid and the third residue is substituted for a threonine. The latter may possibly result from genetic variation arising from the plant’s hybridization. Further, there is a cleavage of a C-terminal pro-domain to yield the mature AMP.

Figure 2.

CC-AMP1 sequence determination. The annotated MS/MS spectrum of reduced and alkylated CC-AMP1, corresponding to the 4+ charge state (m/z 949.47) is shown. The “Z” in the graphical fragment map represents the N-terminal glutamine modified to pyroglutamic acid, the third position represents a K to T substitution (colored in red) in ghost pepper vs. the C. chinense genome, and confirmed disulfide bond linkages (Supplemental Figures S4 and S5) are indicated. The experimental mass of 3793.85 Da corresponds to 5ppm error from the theoretical mass of 3793.83 Da.

To confirm the glutamine to pyroglutamic acid modification, the reduced peptide was digested with pyroglutamate aminopeptidase which removes N-terminal pyroglutamic acids.14 A mass of 3340.67 Da (−105.01 Da) was observed, corresponding to CC-AMP1 with the pyroglutamic acid cleaved and all three disulfide bonds reduced, confirming the presence of the pyroglutamic acid modification at the N-terminus (Figure S3, Supporting Information). This modification is known to help protect peptides from aminopeptidase degradation,15 but is a relatively uncommon modification within AMPs. One study identified only 13 AMPs with this N-terminal cyclic glutamate out of 1147 modified AMPs in the Antimicrobial Peptide Database (APD),16 and only 20 results are obtained of 2021 total AMP modifications when we searched the APD17 in March 2021.

Disulfide bond connectivity contributes to AMP higher order structure and can affect bioactivity.8 Thus, isolated CC-AMP1 with intact disulfide bonds was subjected to trypsin digestion to produce crosslinked peptides which could be analyzed via MS/MS to elucidate the disulfide connectivity. A mass of 2365.15 Da was observed and matches a tri-peptide species containing ZETLDPICMAK, CVLK, and CIAGCVL connected by two disulfide bonds (13 ppm mass error). MS/MS fragmentation was leveraged to discern specific Cys-Cys linkages including CysI of CIAGCVL connected to CVLK and CysII of CIAGCVL connected to ZETLDPICMAK (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Given this result, the third disulfide bond of CC-AMP1 would result from linkage between the cysteines of CGK and AWCLTK. A monoisotopic mass of 1024.48 Da is observed (Figure S5, Supporting Information) with a 0 ppm error from this disulfide-linked di-peptide. The disulfide pattern for the full CC-AMP1 sequence was thus determined to be CysI-CysVI, CysII-CysV, and CysIII-CysIV (Figure 2).

Classification of CC-AMP1 into a known AMP family was explored via homology searching and was found to be 55–60% homologous to 6 proteins within the Capsicum and Nicotiana genera (Figure S6, Supporting Information), with one from Capsicum annuum annotated as “protein TAP1-like” (accession A0A1U8EF54) and another from Nicotiana tabacum annotated as “Thionin-like protein” (accession G1JZD6). The other 4 proteins are annotated as “uncharacterized protein.” Although CC-AMP1 was found to have homology with a thionin-like protein, thionin cysteine motifs typically contain two adjacent cysteines, CysI and CysII, whereas CC-AMP1 has several residues between each cysteine. Thus, possible classification of CC-AMP1 was explored using CAMPSign,18 a tool that identifies an AMP’s family from the 45 AMP families within the CAMPR319 database, and the peptide was indicated to not belong to any of these families. For these reasons, CC-AMP1 was determined as not belonging to the thionin family. Within the 6 homologous proteins identified, the same cysteine motif consisting of 6 cysteine residues is maintained, indicating that these may belong to a novel AMP family expressed within the Solanaceae family. Further, the peptides contain highly conserved N-terminal signal peptides, as well as an additional C-terminal pro-domain. As CC-AMP1 is a variation on predicted C. chinense AMP A0A2G3BCB3, it can be assumed that its precursor also contains an N-terminal signal peptide, and a C-terminal pro-domain was detected in the bottom-up proteomic analysis (Table S3, Supporting Information). Sequence alignment of CC-AMP1 with AMPs contained in the APD17 revealed 41% sequence homology with a peptide from Synoicum turgens (sea squirt) named Turgencin A,20 with all 6 cysteines aligning between the two peptides (Figure S6, Supporting Information). Furthermore, the disulfide bond pattern of CysI-CysVI, CysII-CysV, and CysIII-CysIV in CC-AMP1 is also found in turgencins.20 Unlike CC-AMP1, however, turgencins contain an amidated C-terminus and lack the N-terminal pyroglutamic acid observed in CC-AMP1.20 Turgencins are characterized to have antimicrobial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, with low μM minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values.20

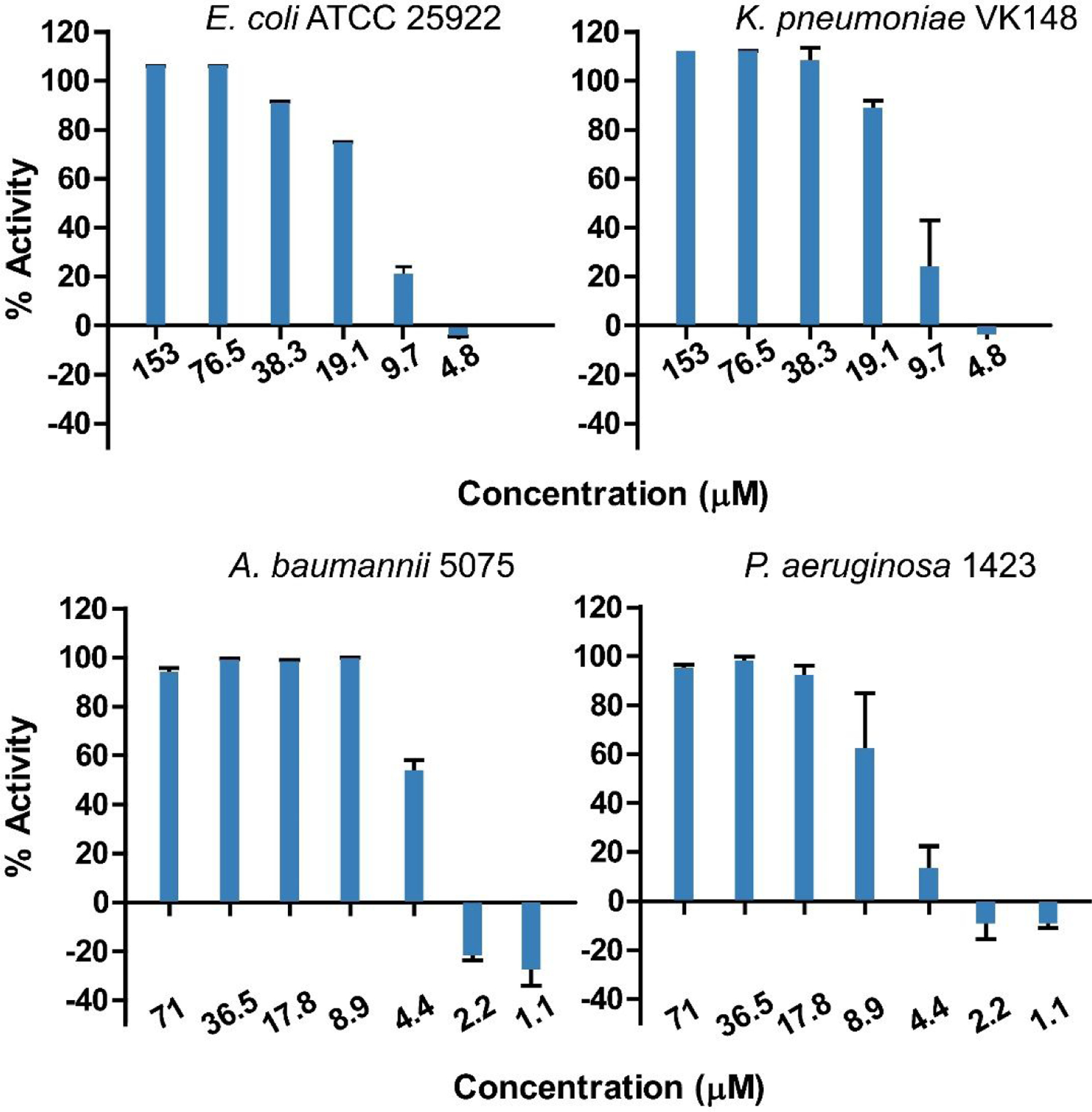

Biological Characterization of CC-AMP1.

Following initial activity observed against E. coli ATCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae VK148, a dilution series of known concentrations of CC-AMP1 was assayed against these as a full ESKAPE pathogen panel. IC50 values were determined for all strains which displayed 100% activity at the highest concentration tested, including gram negative E. coli ATCC 25922 (14.5 μM), K. pneumoniae VK148 (13.2 μM), A. baumannii 5075 (4.0 μM), and P. aeruginosa 1423 (6.9 μM) (Figure 3). Because CC-AMP1 displayed high antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria, a minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assay was performed on A. baumannii 5075, as it displayed the lowest IC50. This assay indicated that CC-AMP1 is bactericidal rather than bacteriostatic and revealed an MBC of 8.6 μM for A. baumannii 5075 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Assays for determination of CC-AMP1 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae VK148, A. baumannii 5075, and P. aeruginosa 1423. These values correspond to the concentration at which 50% activity is observed and correspond to low μM concentrations for each pathogen. Error bars are shown as ± standard deviation of three replicates.

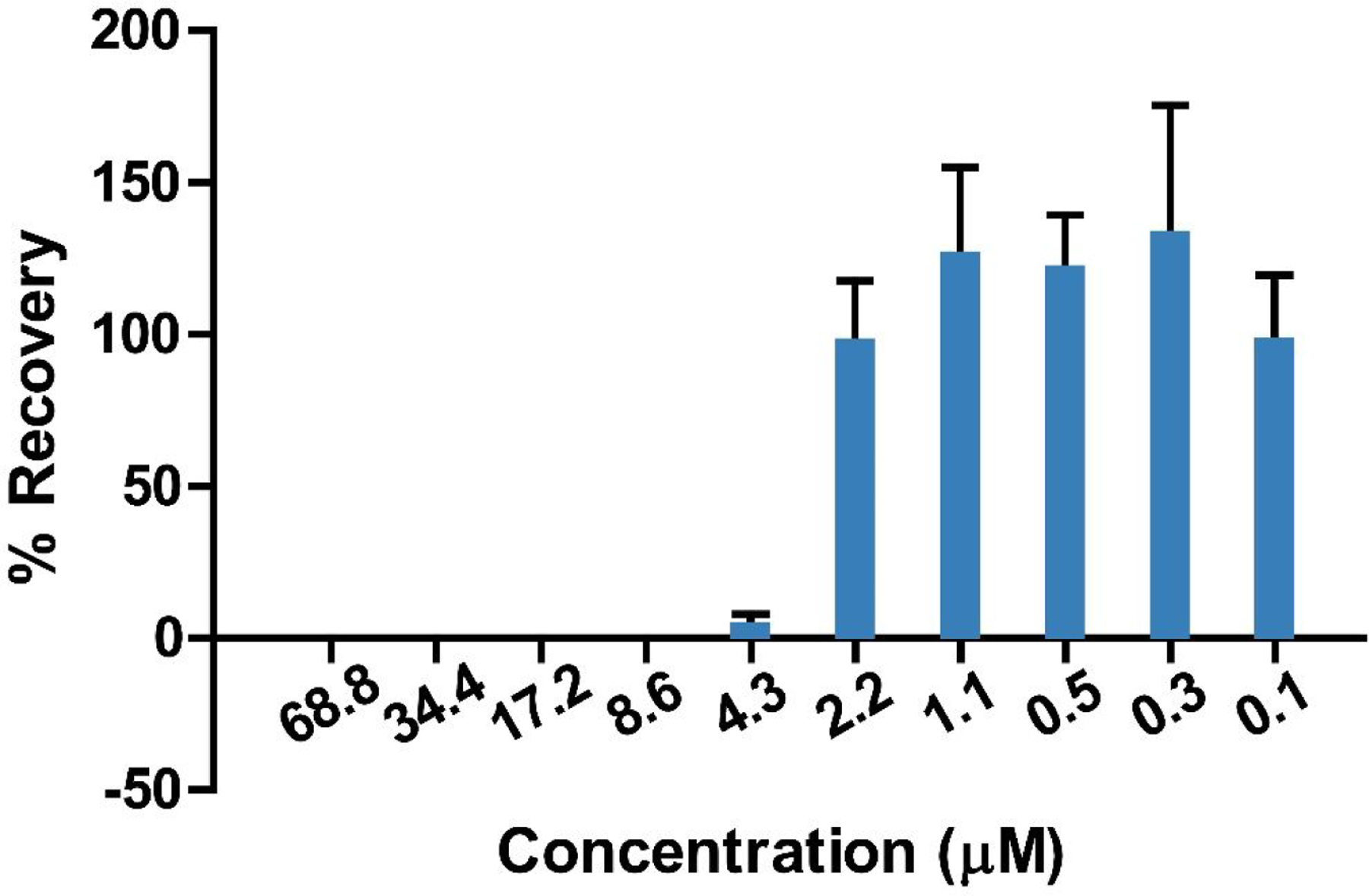

Figure 4.

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) determination of CC-AMP1 against A. baumannii 5075. Zero percent recovery is observed down to a concentration of 8.6 μM, indicating that CC-AMP1 is bactericidal rather than bacteriostatic. Error bars are shown as ± standard deviation of three replicates.

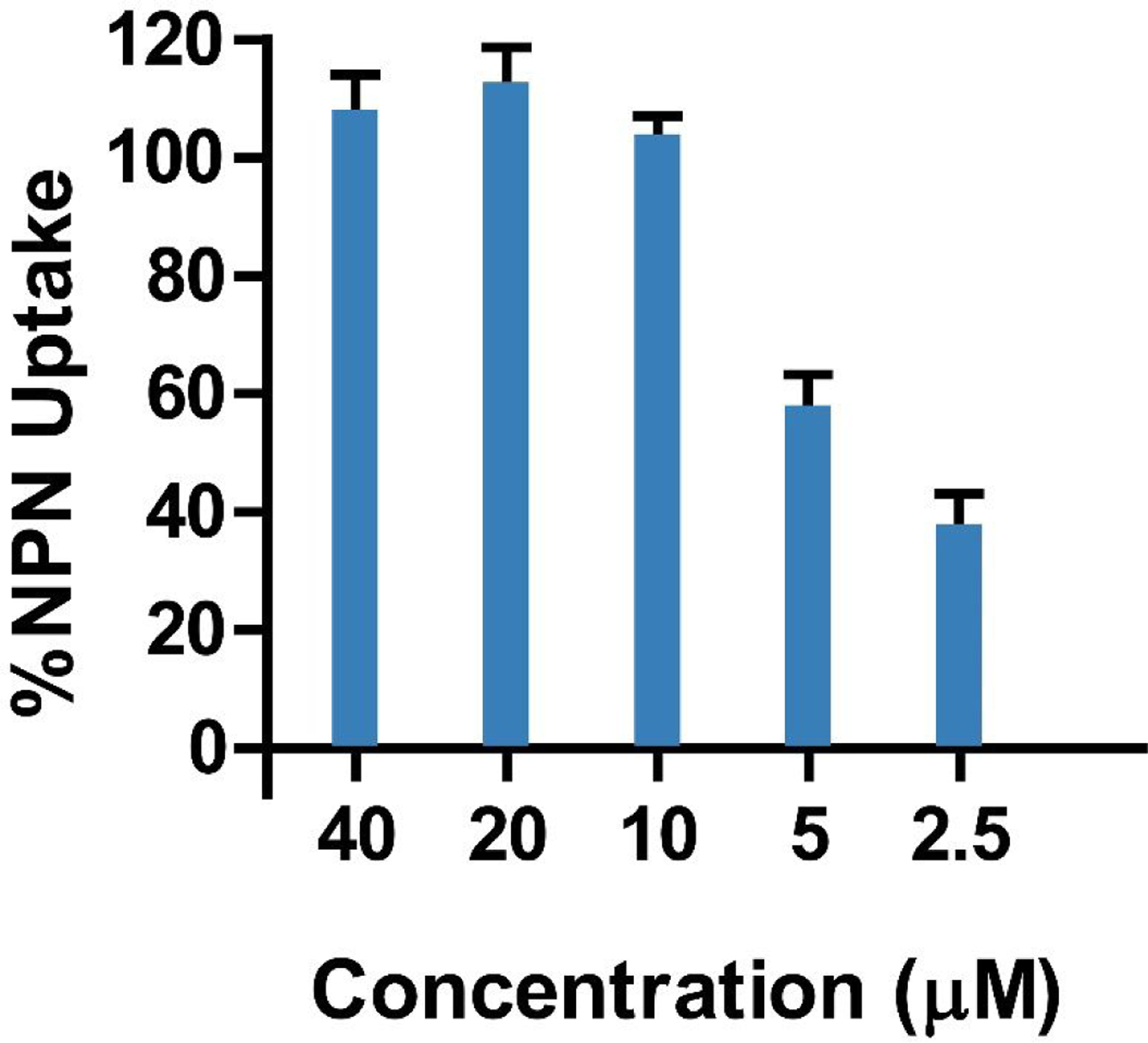

Membrane permeabilization is the most common AMP mechanism of action.21 Given its high antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria, CC-AMP1 was assayed for its ability to permeabilize the outer membrane (OM) using the fluorescent probe N-1-phenyl-naphthylamine (NPN), which displays increased fluorescence upon uptake into the membrane.22 A dilution series of CC-AMP1 starting at 40 μM was assayed against E. coli ATCC 25922 in the presence of NPN. Membrane permeabilization was observed, with an NPN uptake of 100% from 10 to 40 μM of CC-AMP1 (Figure 5), indicating that CC-AMP1 is outer membrane permeabilizing.

Figure 5.

NPN uptake of E. coli ATCC 25922 at different concentrations of CC-AMP1, used to determine outer membrane permeabilization. Greater than 100% NPN uptake is observed from 10 to 40 μM, indicating CC-AMP1 to be strongly outer membrane permeabilizing. Error bars are shown as ± standard deviation of three replicates.

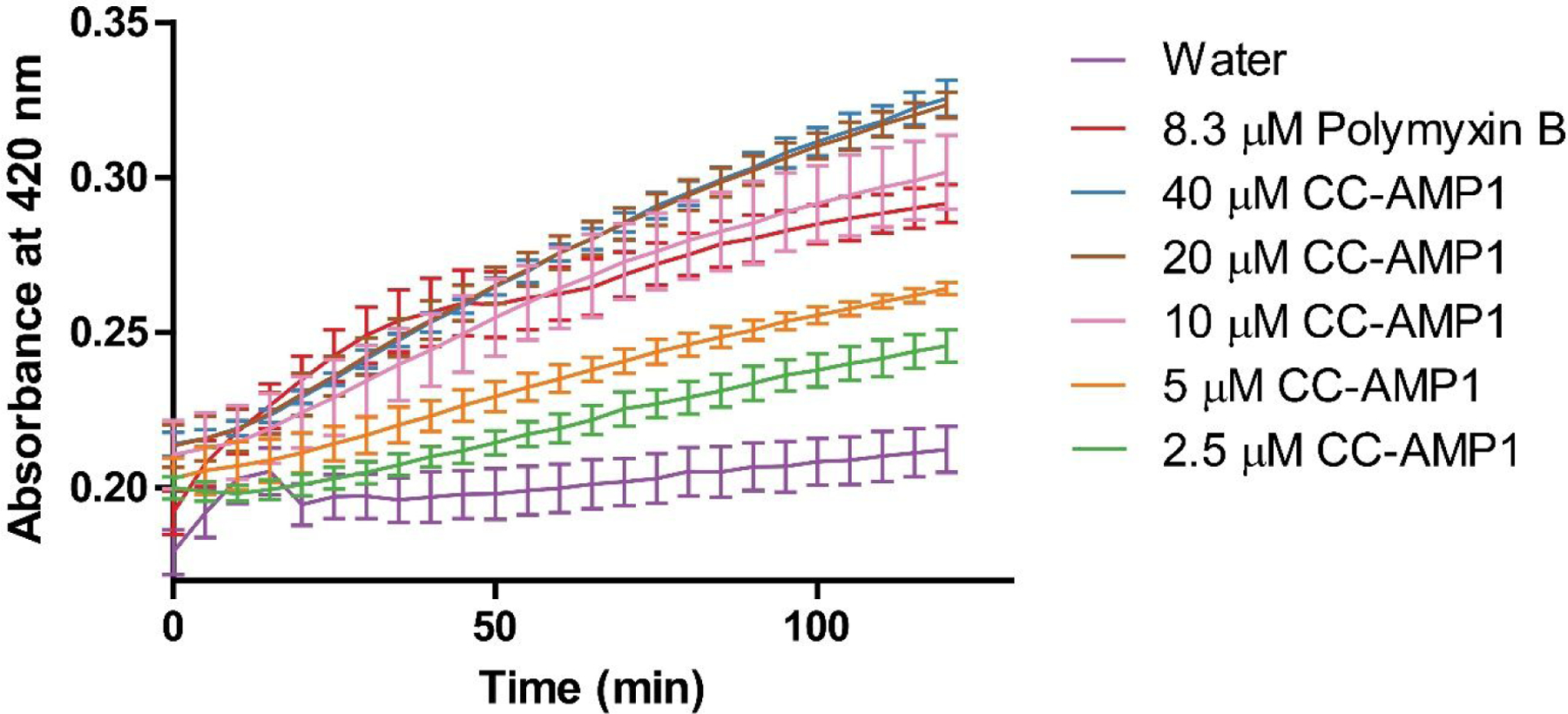

Following confirmation that CC-AMP1 is outer membrane permeabilizing, its ability to permeabilize the inner membrane was assessed using ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG), which is degraded to o-nitrophenol by β-galactosidase upon inner membrane permeabilization of E. coli cells.23 A dilution series of CC-AMP1 was assayed against E. coli ATCC 25922 in the presence of ONPG and absorbance at 420 nm was observed to increase, indicating inner membrane permeabilization by CC-AMP1 (Figure 6). CC-AMP1 therefore appears to bear a bactericidal mechanism of action against gram-negative bacteria, involving permeabilization of both the outer and inner membranes.

Figure 6.

Inner membrane permeabilization assay of E. coli ATCC 25922 at different concentrations of CC-AMP1. Increased 420 nm absorbance is observed over time across the different concentrations of CC-AMP1 and is comparable to the polymyxin B control, indicating that CC-AMP1 is inner membrane permeabilizing. Error bars are shown as ± standard deviation of three replicates.

Molecular Characterization of CC-AMP2.

LC-MS/MS analysis of fractions 27–30 revealed a complex mixture of peptides in which no predicted AMP was detected in bottom-up proteomics data (data not shown). Therefore, peptide abundance across library fractions was profiled and PepSAVI-MS12 was used to generate a ranked list of likely contributors to the antimicrobial activity (Table S4, Supporting Information). The top 20 contributors included four charge states of a 4011.99 Da peptide, deemed CC-AMP2, whose abundances closely mirror the bioactivity of fractions 27–30 (Figure S7, Supporting Information) and was prioritized for further characterization.

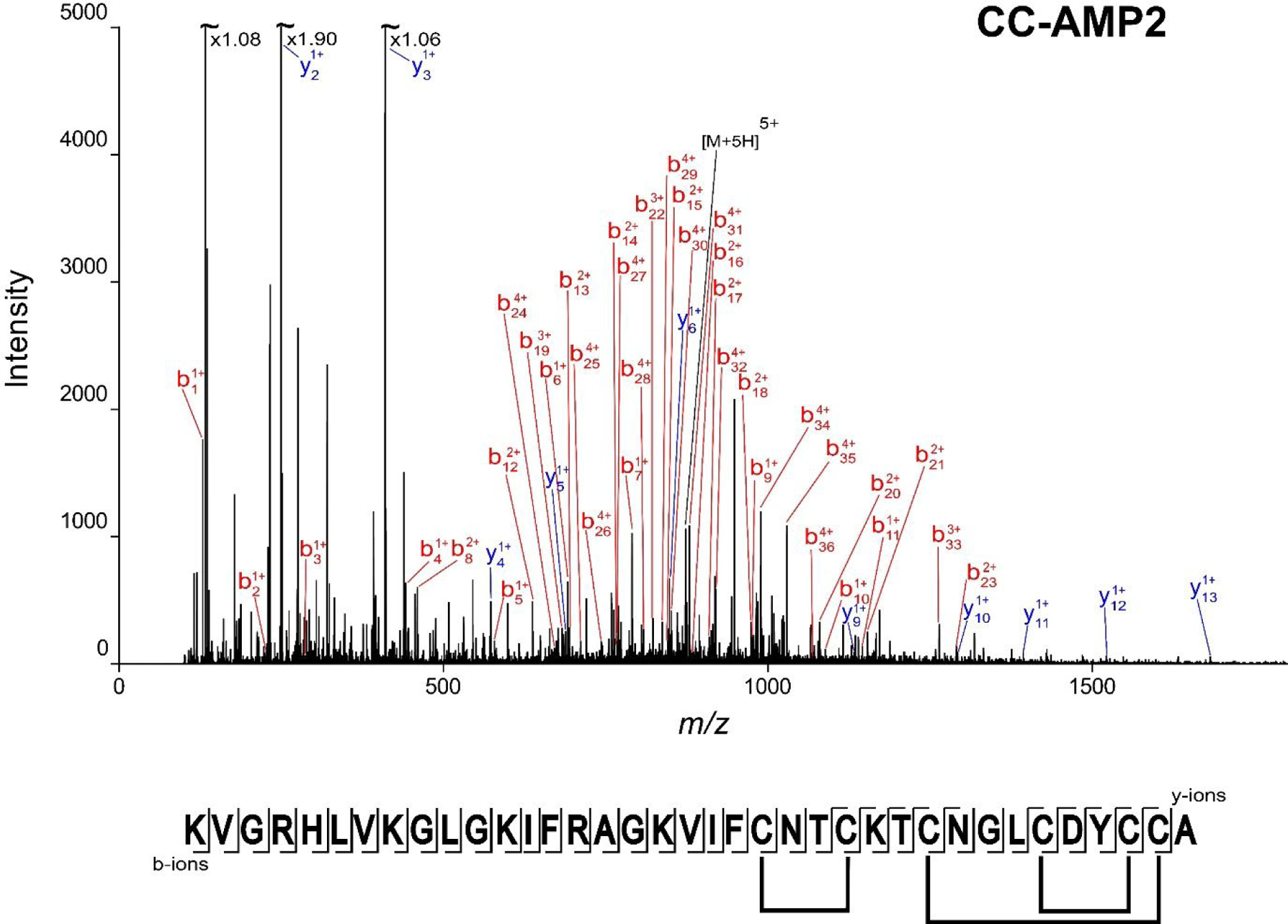

Reduction/alkylation of CC-AMP2 produced a mass shift of 348.17 Da (to 4360.16 Da) corresponding to the reduction and alkylation of three disulfide bonds. De novo sequencing of the reduced and alkylated peptide revealed that the peptide sequence was KVGRHLVKGLGKIFRAGKVIFCNTCKTCNGLCDYCCA (calculated mass 4360.15 Da) (Figure 7), differing from the experimental mass of CC-AMP2 by 2 ppm. Tryptic digestion produced a peptide whose fragmentation provided 51% sequence coverage supporting the sequence assignment (data not shown).

Figure 7.

CC-AMP2 sequence determination. The annotated MS/MS spectrum of reduced and alkylated CC-AMP2, corresponding to the 5+ charge state (m/z 873.04) is shown. The fragment map with the full sequence, as well as the confirmed disulfide bond linkages (Supplemental Figures S8 and S9) are presented below the spectrum. Full coverage of the sequence is obtained in the b-ion series. The experimental mass of 4360.16 Da corresponds to a 2 ppm error from the theoretical mass of 4360.15 Da.

While this sequence was not an in silico predicted AMP, it is derived from a protein in C. chinense annotated as an uncharacterized protein (A0A2G3CEJ1). This protein was detected in the initial bottom-up proteomics analysis of the peptide extract but was not predicted by Cysmotif Searcher because it does not contain a recognizable cysteine motif. Further, analysis of the SignalP output (Table S1, Supporting Information) shows that a signal peptide was predicted, but did not capture the full N-terminal cleavage, indicating there is an additional leader peptide whose cleavage is required to produce the mature AMP. These results highlight the advantage of using complementary AMP identification techniques such as PepSAVI-MS to most fully capture the AMP repertoire of a given plant species.

Homology of 58–92% is seen for CC-AMP2 with 20 proteins within both the Capsicum and Solanum genera including a conserved cysteine motif, suggesting that these putative AMPs are found broadly within the Solanaceae family (Figure S8, Supporting Information). All of these are annotated as “uncharacterized protein” except for five within C. annuum (UniProt accessions: Q947G5, Q8W2C1, Q947G6, Q9SEM2, and A0A023JGF0) which are annotated as SAR8.2 or stress-induced proteins, with “SAR” referring to systemic acquired resistance. These SAR genes are induced in C. annuum by biotic and abiotic stresses, and not constitutively expressed in any organs of the healthy plant.24 This suggests that these putative AMPs across the Solanaceae family may be derived from systemic acquired resistance and could indicate that the C. chinense × frutescens plants experienced environmental stressors during their growth, such as water stress or pests. Sequence alignment of CC-AMP2 with AMPs deposited in the APD17 did not reveal any AMPs that share the same cysteine motif. Like CC-AMP1, possible classification of CC-AMP2 was also explored using CAMPSign18 and was not indicated to belong to any AMP families within the CAMPR319 database. This entirely unique cysteine motif implies that the Solanaceae peptides related to CC-AMP2 (Figure S8, Supporting Information) may be a novel family of AMPs.

Partial acid hydrolysis was used to elucidate cysteine connectivity of CC-AMP2 because its cysteine motif does not contain protease cleavage sites which would yield simplified cross-linked peptides upon digestion. Partial acid hydrolysis of CC-AMP2 produced a complex mixture of smaller disulfide-bound peptides, which could more easily be analyzed via MS/MS, and converted asparagine and glutamine residues to aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues, respectively.25 Connectivity was determined by manually searching for precursor masses that could correspond to the disulfide-bound acid hydrolysis fragments, followed by confirmation of the residues and elucidation of the disulfide linkages via the MS/MS fragmentation spectra. An MS/MS spectrum of a precursor ion with a monoisotopic mass of 925.40 Da was observed corresponding to the peptide VIFCDTCK (theoretical mass 925.40 Da, 0 ppm error) with an intramolecular disulfide bond (Figure S9, Supporting Information). Another MS/MS spectrum is observed, for a precursor of 1179.32 Da, corresponding to peptides TCDG and LCDYCCA linked together with two disulfide bonds (theoretical mass 1179.33 Da, 8 ppm error) (Figure S10, Supporting Information). Overall, disulfide connectivity for CC-AMP2 was found to be CysI-CysII, CysIII-CysVI, and CysIV-CysV (Figure 7).

Biological Characterization of CC-AMP2.

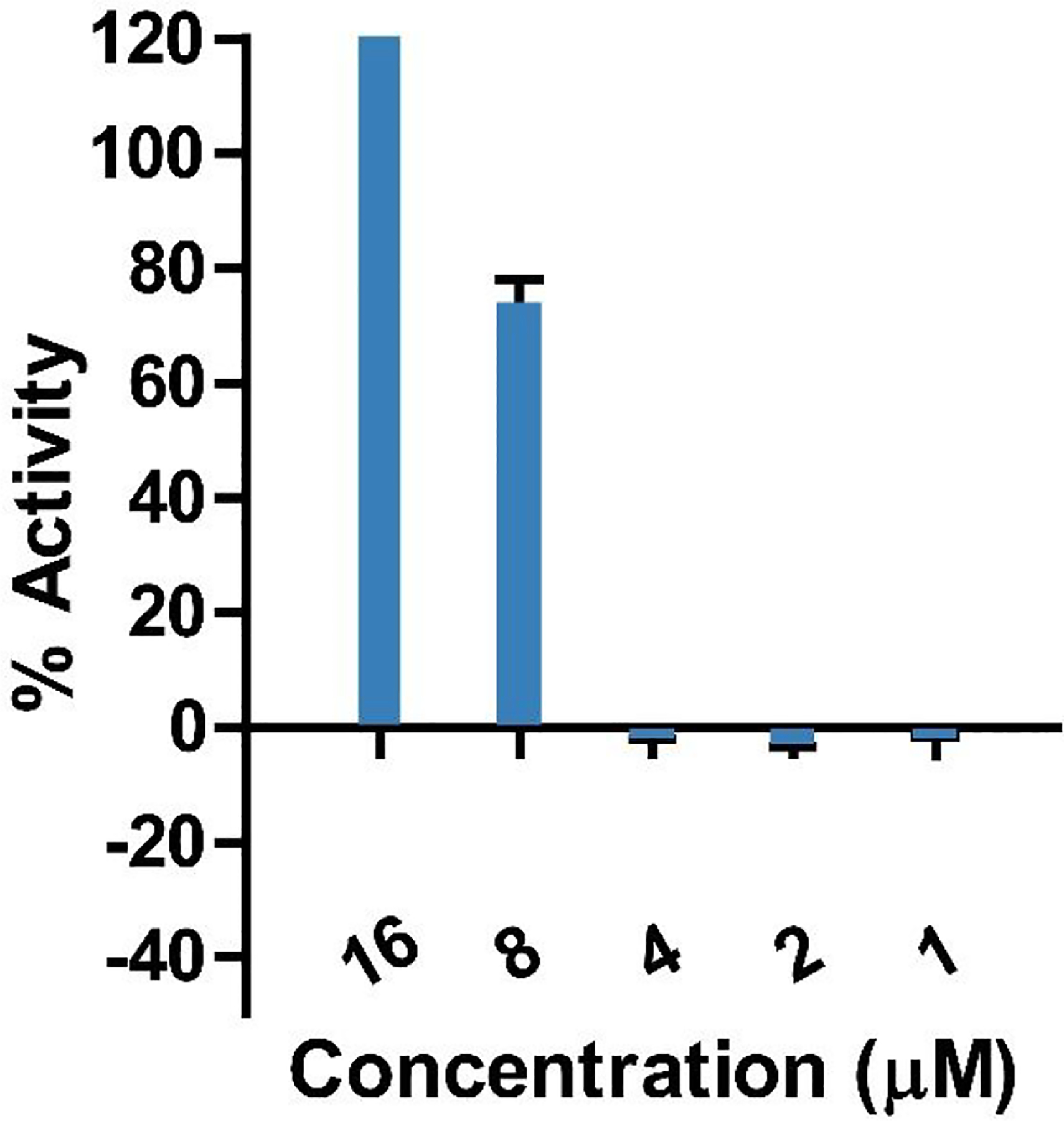

Given the low abundance of CC-AMP2 expressed, biological characterization was limited to the IC50 determination of the peptide against E. coli ATCC 25922. CC-AMP2 was isolated utilizing reversed-phase chromatography and LC-MS analysis confirmed purity (Figure S11, Supporting Information). A dilution series from 16 μM was assayed (Figure 8) and the IC50 value was determined to be 7.6 μM.

Figure 8.

Assay for the determination of CC-AMP2 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against E. coli ATCC 25922. This value corresponds to the concentration at which 50% is observed and corresponds to a low μM concentration. Error bars are shown as ± standard deviation of three replicates.

In conclusion, 115 predicted AMPs were revealed within the C. chinense proteome through the use of SignalP and Cysmotif Searcher. Bottom-up proteomics of C. chinense × frutescens aerial tissue identified 15 putative AMPs. Additionally, two novel AMPs, CC-AMP1 and CC-AMP2, were identified and characterized. Full sequences of both peptides were determined, including elucidation of disulfide bond connectivity. Antimicrobial assays of CC-AMP1 and CC-AMP2 indicated low IC50 values against several gram-negative pathogens. Mechanism of action characterization of CC-AMP1 shows it to permeabilize the outer and inner membranes of gram-negative bacteria. These results highlight the power of utilizing the complementary approaches of AMP prediction, proteomics, and antimicrobial assays in the analyses of plant peptidomes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures.

Off-line separations were performed with a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC equipped with a UV–vis detector (220 nm) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). LC-MS/MS data was collected using a nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS platform composed of a nanoAcquity UPLC (Waters, Milford, MA) coupled to a TripleTOF 5600 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA) and an Acquity UPLC M-Class System (Waters) coupled to a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository26 with the data set identifier PXD024605 ( username: reviewer_pxd024605@ebi.ac.uk password: FdGgudss ).

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (RS003) was obtained through the American Type Culture Collection. Staphylococcus aureus LAC (RS001)27 was obtained from the Richardson laboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Klebsiella pneumoniae VK148 (RS0025)28 from the Miller laboratory at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The ESKAPE pathogen strains are clinical isolates stored within the Shaw Laboratory collection. Enterococcus faecalis (E:1450), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K: 1433), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P: 1423), and Enterobacter cloacae (E: 1454) were obtained by the Shaw Lab from Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, FL, USA).29 Staphylococcus aureus (S: 635) was obtained from Tampa General Hospital.29 Acinetobacter baumannii (A: 5075) was obtained via a colleague at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, MD, USA).30

Plant Material.

Capsicum chinense × frutescens seeds were purchased from Strictly Medicinal Seeds (Williams, OR) and planted in nutrient rich soil. Plants were grown under controlled temperature (17.5–20.3°C) and light cycle (14 hours) conditions. The plants were grown for approximately 12 weeks and aerial tissue was harvested in November 2019 with immediate flash freezing and storage at −80°C until extraction. A specimen was deposited in the Herbarium of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (NCU, accession numbers 673755, 673754, 673753). Specimens are publicly available for viewing on the SERNEC (Southeast Regional Network of Expertise and Collections) Web site (http://sernecportal.org/portal/index.php), with catalog numbers NCU00441757, NCU00441758, NCU00441759.

Capsicum chinense Genome AMP Prediction.

SignalP-5.09 with default options was used to identify proteins in the C. chinense reference proteome31 (UniProt proteome ID UP000224522, downloaded from UniProt on January 21, 2020) that contained signal peptides, predicted cleavage sites, and export a FASTA file with these proteins after signal peptide cleavage. This FASTA file was used with Cysmotif Searcher10 to predict antimicrobial peptides in the Capsicum chinense genome. With Cysmotif Searcher, the option of skipping translation of input sequences was used, and SPADA32 was not included in the computational pipeline.

Peptide Extraction and Creation of Peptide Library.

One hundred and sixty grams of plant aerial tissue was extracted in an acetic acid solution as previously described,12 with size exclusion steps to remove large proteins (>30 kDa) and small molecules concentrating to a final volume of 40 g starting material/mL to avoid precipitation. Neutral and negatively charged molecules were removed through SCX chromatography, desalted, and fractionated using reversed-phase chromatography as previously described.33 Fractions were collected every minute, dried in a vacuum centrifuge, and resuspended in 95 μL of LC-MS grade water.

For CC-AMP2 isolation, fractions 26–30 were re-combined and subjected to an additional reversed-phase chromatographic separation on the same system, with mobile phase A consisting of water with 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B consisting of acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The sample was injected at a volume of 500 μL and a linear gradient of increasing mobile phase B was used, at a flow rate of 1.25 mL/min. Mobile phase B was held at 5% for 1 min before being increased from 5% to 50% in 30 min and ramping to 85% in 2 min, where it was held for 3 min before returning to 5% in 1 min and re-equilibrating for 23 min. Fractions were collected every minute, dried in a vacuum centrifuge, and resuspended in LC-MS grade water before being assessed for purity.

Reduction, Alkylation and Trypsin Digestion.

Peptide sample aliquots of 10 μL were reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (Millipore-Sigma) at 45°C at 850 rpm for 30 minutes, and alkylated with 100 mM iodoacetamide (Millipore-Sigma) at 25°C at 850 rpm for 15 minutes. 10 μL of reduced and alkylated fraction was digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Millipore-Sigma) with an enzyme/protein ratio of 1:50 (w/w) and incubated at 37°C at 850 rpm overnight. All samples were desalted with C18 ZipTips prior to further analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis.

The C. chinense × frutescens peptide samples were analyzed using a nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS platform as previously described12 with the following specifications: 0.1% formic acid in all mobile phases and a trapping mobile phase composition of 1% MeCN/0.1% formic acid. The MS was operated in positive-ion, high-sensitivity mode with the MS survey spectrum using a mass range of m/z 350–1600 in 250 ms and information-dependent acquisition (IDA) of MS/MS data using an eight second dynamic exclusion window. The first 20 features above an intensity threshold of 150 counts and having a charge state of +2 to +5 were fragmented using rolling collision energy (CE) (±5%). Intact peptides, reduced and alkylated peptides, and tryptic peptides were all analyzed using this method. Peptide abundance was quantified using Progenesis QI for Proteomics software (Nonlinear Dynamics, v.2.0) as previously described12 to create a list of mass spectrometric species for statistical modeling. Default peak picking settings were used with the exception that a minimum peak width of 0.05 min was required. Targeted CID MS/MS data was acquired for the peptides of interest, at 4360 Da (charge states 3+,4+,5+,6+) and 3793 Da (charge states 3+,4+,5+), using reduced and alkylated samples and a CE of 45.

For the confirmation of CC-AMP2 purity, the sample was analyzed using an Acquity UPLC M-Class System (Waters) coupled to a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described,34 with the following modifications: the sample was injected at a volume of 4 μL, the Nanospray Flex source had spray voltage floating at 2.3 kV, and the analytical gradient was modified. A linear gradient of increasing mobile phase B at a flow rate of 300 nL/min was used. Mobile phase B was held at 5% for 1 min before being increased from 5% to 50% in 30 min and ramping to 85% in 2 min, where it was held for 3 min before returning to 5% in 1 min and re-equilibrating for 23 min.

Database Searching.

Acquired LC-MS/MS data (.wiff) from trypsin digested samples were converted to Mascot Generic Format (.mgf) with Sciex Data Converter version 1.3. The converted files were searched against the proteome from the C. chinense reference proteome,31 containing 34,747 unique proteins (UniProt ID: UP000224522) appended with sequences for common laboratory contaminants (http://thegpm.org/cRAP/; 116 entries) using Mascot (v2.5.1; Matrix Science). Fixed modifications of carbidomethyl and a methionine oxidation variable modifications were allowed. Maximum missed cleavages was set to 3, peptide charge was set to 1+, 2+, and 3+, and peptide tolerance was set to ±15 ppm. Significant peptide identifications above the identity or homology threshold were adjusted to near 1% peptide FDR using the embedded Percolator algorithm.35 A total of 707 peptides with score >13 (p <0.05) were identified and considered in further analysis.

Initial Bioassays.

E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae VK148, and S. aureus LAC were streaked on LB plates and incubated at 37°C for 16 hours. The assays against each were performed as previously described.12 Briefly, assays were performed in technical triplicate using a 96-well plate in 1xMHB combining 10 μL peptide fraction with 40 μL 0.125 OD600 bacterial culture. Ampicillin (0.1 mg/mL) or erythromycin (0.1 mg/mL) were used in E. coli and K. pneumoniae/S. aureus assays, respectively, as the positive control. Water was used as the negative control. Assays were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C at 250 rpm and OD600 was measured before adding 1 μL of 50 mM resazurin to each well. After 1 additional hour of incubation at 37°C at 250 rpm, a fluorescence measurement with 544 nm (ex) and 590 nm (em) was collected. Calculation of percent activity was done as previously described,12 using OD600 readings from the 4 hour incubation for the initial bioassay (Figure 1) and fluorescence readings from the additional 1 hour of incubation using resazurin for subsequent assays involving E. coli ATCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae VK148.

ESKAPE Pathogen Assays:

CC-AMP1 was tested against the ESKAPE pathogens (clinical isolates) of the Shaw Lab strain collection. Bacterial strains were maintained by streaking onto Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) and were stored at 4°C before each use. Bacterial cultures were tested for inhibitory activity as previously described.36 In brief, samples were synchronized to exponential phase and set to a starting CFU/mL of 1×107 with varying concentrations of peptide. No treatment controls, media only and commercial antibiotic controls were included in each assay. Optical density reads were taken at strain specific time points using a Citation 5 plate reader (BioTek). Strains were tested in biological triplicate and percent activity was calculated using the following equation: % activity = ((1-((OD600 of fraction -OD600 of positive control)/(OD600 of negative control – OD600 of positive control)) × 100.

IC50 Determination:

For assay results of dilution series which displayed ≥ 100% activity, the IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism (v5; GraphPad Software). The “log(inhibitor) vs. response -- Variable slope (four parameters)” nonlinear regression analysis was used with the “interpolate unknowns from standard curve” option selected, following conversion of the concentration values to log(concentration).

Minimum Bactericidal Concentration Determination:

Following the bacterial antimicrobial susceptibility testing for A. baumannii (5075), the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was assessed. The MBC was determined for each concentration of compound tested including no treatment controls in biological triplicate. In brief, each treated well was serial diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and plated on TSA in biological duplicate. Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and cell viability was determined by calculating CFU/mL for each condition. Percent recovery was calculated by comparing the CFU/mL of each test sample to the no treatment control samples. % recovery = ((CFU/mL test sample)/(CFU/mL negative control)) × 100.

Statistical Modeling.

Data reduction and statistical modeling were performed using the PepSAVI-MS statistical analysis package (https://cran.r-project.org/package=PepSAVIms).12 The bioactive region of the Capsicum chinense peptide library was defined as fractions 27–30. Mass spectrometric features with identical charge states, masses within 0.05 Da, and retention times within 5 min of each other were binned. Background ions were eliminated by selecting for retention time (15–45 min), mass (1,000–15,000 Da), and charge-state (+2–9, inclusive). After filtering there were 7644 features. The resulting list was further filtered so that the maximum abundance of each feature was above 100 and detected in fractions 27–30, with <5% maximum abundance outside of the defined bioactive region. After filtering, 72 features met these criteria and were modeled using the elastic net estimator with a quadratic penalty parameter specification of 0.01. After modeling, 39 features were identified as possible contributors to bioactivity and the top 20 highest ranked candidates were selected for further investigation.

Pyroglutamate Aminopeptidase Digestion of CC-AMP1.

An aliquot of 10 μL of peptide sample was dried and resuspended in 40 μL of 50 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0 buffer (Takara Bio). Pyrococcus furiosus pyroglutamate aminopeptidase (Takara Bio) was resuspended in the same buffer and 1 mU of enzyme was added to the sample. The sample was incubated at 37°C for 3 hours with shaking at 850 rpm. The digested sample was dried and resuspended in 200 μL of water, followed by 3 subsequent spin filtration steps using a 3 kDa filter (Millipore Sigma), washing the sample with water each time to remove EDTA. The filtered sample was subjected to a C18 ZipTip cleanup, followed by LC-MS analysis.

Sequence Alignments and Homology Searching.

Homology searching was carried out using the UniProt Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) using the UniProtKB Plants database. Duplicate protein sequences from the same organism were discarded, if observed in the results. Multiple sequence alignments were performed utilizing the UniProt “Align” tool.37 AMP homology was further searched using the Antimicrobial Peptide Database17 “Calculation & Prediction” tool, which includes an alignment feature. Possible AMP classification was explored using CAMPSign,18 searching against all families.

Determination of Disulfide Bond Linkages.

A 10 μL aliquot of CC-AMP1 sample, with no prior reduction or alkylation, was added to 51 μL of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.8, and the peptide was digested with trypsin gold (Promega) with an enzyme/protein ratio of 1:50 (w/w) and incubated at 37°C at 850 rpm overnight. For CC-AMP2, a 20 μL aliquot of sample was added to a glass vial with 40 μL of 3M HCl. The vial was then incubated at 85°C for a total of 80 minutes, with aliquots of sample removed every 15 minutes for analysis. The HCl was evaporated under nitrogen gas. Both CC-AMP1 and CC-AMP2 samples were desalted using C18 ZipTips and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis.

Outer Membrane Permeabilization Assay.

Outer membrane permeabilization was assessed by modifying a method as previously described by Dong et al.23 E. coli ATCC 25922 was streaked on an LB plate and incubated for 16 hours at 37°C. A bacterial colony was incubated overnight in MHB and then diluted to OD600 0.25 to be incubated for an additional hour. Cells were washed with 5 mM HEPES buffer containing 5 mM glucose at pH 7.4, and resuspended in a 5 mL aliquot of the same buffer. NPN was added to a final concentration of 10 μM and the culture was incubated for 30 minutes in the dark, at room temperature. The assay was performed in technical triplicate in a 96 well plate, using 40 μL of culture and 10 μL peptide. Polymyxin B was used as the positive control, with a final concentration of 10 μg/mL, and water was used as the negative control. After additions of each solution to the wells, fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm. NPN uptake was determined by the formula

Where Fobs is the fluorescence of peptide sample, F0 is the fluorescence of negative control, and F100 is the fluorescence of positive control.

Inner Membrane Permeabilization Assay.

Inner membrane permeabilization was assessed by modifying a method as previously described by Dong et al.23 E. coli ATCC 25922 was streaked on an LB plate and incubated for 16 hours at 37°C. A bacterial colony was incubated overnight in MHB containing 2% lactose and then diluted to OD600 0.25 to be incubated for an additional hour. Cells were washed three times with 5 mM HEPES buffer containing 20 mM glucose at pH 7.4, and resuspended in a 5 mL aliquot of the same buffer and ONPG was added to a final concentration of 1.5 mM. The assay was performed in technical triplicate in a 96 well plate, using 40 μL of culture and 10 μL peptide. Polymyxin B was used as the positive control, with a final concentration of 10 μg/mL, and water was used as the negative control. Absorbance at 420 nm was measured every 5 minutes for a total of 2 hours.

Peptide Concentration Determination.

Isolated peptides were resuspended in water and measured using a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at an absorbance of 280 nm. Concentrations were calculated by the ND-1000 software. Expasy ProtParam was used to estimate extinction coefficients.38

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH-NIGMS under award number GM125814 to L.M.H.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

REFERENCES

- (1).Bosland PW; Baral JB HortScience 2007, 42, 222–224. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Purkayastha JJ Biosci. 2012, 37, 757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Liu Y; Nair MG Nat. Prod. Commun 2010, 5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Friedman JR; Richbart SD; Merritt JC; Brown KC; Denning KL; Tirona MT; Valentovic MA; Miles SL; Dasgupta P Biomed. Pharmacother 2019, 118, 109317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Oyedemi BOM; Kotsia EM; Stapleton PD; Gibbons SJ Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 245, 111871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Afroz M; Akter S; Ahmed A; Rouf R; Shilpi JA; Tiralongo E; Sarker SD; Göransson U; Uddin SJ Front. Pharmacol 2020, 11, 565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Díaz-Murillo V; Medina-Estrada I; López-Meza JE; Ochoa-Zarzosa A Peptides 2016, 78, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tam J; Wang S; Wong K; Tan W Pharmaceuticals 2015, 8, 711–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Almagro Armenteros JJ; Tsirigos KD; Sønderby CK; Petersen TN; Winther O; Brunak S; von Heijne G; Nielsen H Nat. Biotechnol 2019, 37, 420–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Shelenkov AA; Slavokhotova AA; Odintsova TI Biochem. 2018, 83, 1424–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Shelenkov A; Slavokhotova A; Odintsova T Antibiotics. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kirkpatrick CL; Broberg CA; McCool EN; Lee WJ; Chao A; McConnell EW; Pritchard DA; Hebert M; Fleeman R; Adams J; Jamil A; Madera L; Strömstedt AA; Göransson U; Liu Y; Hoskin DW; Shaw LN; Hicks LM Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 1194–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lay FT; Poon S; McKenna JA; Connelly AA; Barbeta BL; McGinness BS; Fox JL; Daly NL; Craik DJ; Heath RL; Anderson MA BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Podell DN; Abraham GN Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1978, 81, 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Rink R; Arkema-Meter A; Baudoin I; Post E; Kuipers A; Nelemans SA; Akanbi MHJ; Moll GN J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2010, 61, 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang G Curr. Biotechnol 2012, 1, 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wang G; Li X; Wang Z Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D1087–D1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Waghu FH; Barai RS; Idicula-Thomas S Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 24684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Waghu FH; Barai RS; Gurung P; Idicula-Thomas S Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1094–D1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hansen IKØ; Isaksson J; Poth AG; Hansen KØ; Andersen AJC; Richard CSM; Blencke H-M; Stensvåg K; Craik DJ; Haug T Marine Drugs. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sierra JM; Fusté E; Rabanal F; Vinuesa T; Viñas M Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 2017, 17, 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Helander IM; Mattila-Sandholm TJ Appl. Microbiol 2000, 88, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Dong N; Wang C; Zhang T; Zhang L; Xue C; Feng X; Bi C; Shan A Int. J. Mol. Sci 2019, 20, 3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lee SC; Hwang BK Planta 2003, 216, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zubarev RA; Chivanov VD; Håkansson P; Sundqvist BUR; Ens W Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 1994, 8, 906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Vizcaíno JA; Csordas A; del-Toro N; Dianes JA; Griss J; Lavidas I; Mayer G; Perez-Riverol Y; Reisinger F; Ternent T; Xu Q-W; Wang R; Hermjakob H Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D447–D456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kennedy AD; Otto M; Braughton KR; Whitney AR; Chen L; Mathema B; Mediavilla JR; Byrne KA; Parkins LD; Tenover FC; Kreiswirth BN; Musser JM; DeLeo FR Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lawlor MS; Hsu J; Rick PD; Miller VL Mol. Microbiol 2005, 58, 1054–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Fleeman R; LaVoi TM; Santos RG; Morales A; Nefzi A; Welmaker GS; Medina-Franco JL; Giulianotti MA; Houghten RA; Shaw LN J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 3340–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Jacobs AC; Thompson MG; Black CC; Kessler JL; Clark LP; McQueary CN; Gancz HY; Corey BW; Moon JK; Si Y; Owen MT; Hallock JD; Kwak YI; Summers A; Li CZ; Rasko DA; Penwell WF; Honnold CL; Wise MC; Waterman PE; Lesho EP; Stewart RL; Actis LA; Palys TJ; Craft DW; Zurawski DV MBio 2014, 5, e01076–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kim S; Park J; Yeom S-I; Yong-Min K; Seo E; Ki-Tae K; Myung-Shin K; Lee JM; Cheong K; Shin H-S; Kim S-B; Han K; Lee J; Park M; Lee H-A; Hye-Young L Genome Biol. 2017, 18.28126036 [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zhou P; Silverstein KA; Gao L; Walton JD; Nallu S; Guhlin J; Young ND BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Moyer TB; Heil LR; Kirkpatrick CL; Goldfarb D; Lefever WA; Parsley NC; Wommack AJ; Hicks LM J. Nat. Prod 2019, 82, 2744–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Iannetta AA; Rogers HT; Al-Mohanna T; O’Brien JN; Wommack AJ; Popescu SC; Hicks LM Plant J. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Käll L; Canterbury JD; Weston J; Noble WS; MacCoss MJ Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 923–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Moyer TB; Allen JL; Shaw LN; Hicks LM J. Nat. Prod 2021, 84, 444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Pundir S; Martin MJ; O’Donovan C Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma 2016, 53, 1.29.1–1.29.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Gasteiger E; Hoogland C; Gattiker A; Duvaud S; Wilkins MR; Appel RD; Bairoch A The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker JM, Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2005; pp 571–607. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.