This survey study aims to estimate the point prevalence of vitiligo among US adults aged 18 to 85 years.

Key Points

Question

What is the current point prevalence of vitiligo among adults in the US?

Findings

This cross-sectional, population-based online survey study of more than 40 000 adults in the US was conducted between December 2019 and March 2020. Participant self-report, and adjudication of vitiligo by 3 dermatologists through participant submission of photographs of their skin lesions, resulted in an estimated point prevalence for diagnosed and undiagnosed vitiligo combined of 1.38% (self-reported) and 0.76% (clinician adjudicated).

Meaning

This study provides current US population-based point prevalence estimates of all vitiligo, beyond just the diagnosed population, including estimates for undiagnosed, segmental, and nonsegmental vitiligo.

Abstract

Importance

Vitiligo can have profound effects on patients and is often associated with other autoimmune comorbid conditions. It is important to understand the current prevalence of vitiligo, including diagnosed, undiagnosed, and subtypes (nonsegmental and segmental).

Objective

To estimate the point prevalence of vitiligo in the US.

Design, Setting, and Participants

For this population-based study of adults in the US, a cross-sectional online survey was administered between December 2019 and March 2020 to obtain participant self-reported vitiligo status. A representative sample of the US adult general population, aged 18 to 85 years, was recruited using a stratified proportional, sampling design from general population research panels. Additionally, 3 expert dermatologists adjudicated participants’ self-reported vitiligo diagnosis by reviewing photographs uploaded by the participants using a teledermatology app designed and tested specifically for this study.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were the point prevalence estimates of overall vitiligo, as well as diagnosed, undiagnosed, nonsegmental, and segmental vitiligo.

Results

Among the 40 888 eligible adult participants, the mean (SD) age was 44.9 (17.4) years, 23 170 (56.7%) were female, 30 428 (74.4%) were White, and 4225 (10.3%) were of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. Self-reported vitiligo prevalence was 1.38% (95% CI, 1.26%-1.49%), with 0.77% (95% CI, 0.68%-0.85%) for diagnosed and 0.61% (95% CI, 0.54%-0.69%) for undiagnosed. Based on expert dermatologist review of 113 photographs of participants with self-reported vitiligo, clinician-adjudicated vitiligo prevalence (sensitivity bounds) was 0.76% (0.76%-1.11%), with 0.46% (0.46%-0.61%) for diagnosed and 0.29% (0.29%-0.50%) for undiagnosed. Self-reported nonsegmental vitiligo prevalence was 0.77% (95% CI, 0.68%-0.85%), with 0.48% (95% CI, 0.41%-0.55%) for diagnosed and 0.29% (95% CI, 0.23%-0.34%) for undiagnosed. Clinician-adjudicated nonsegmental vitiligo prevalence (sensitivity bounds) was 0.58% (0.57%-0.84%), with 0.37% (0.37%-0.49%) for diagnosed and 0.21% (0.20%-0.36%) for undiagnosed. Self-reported segmental vitiligo prevalence was 0.61% (95% CI, 0.53%-0.69%), with 0.28% (95% CI, 0.23%-0.33%) for diagnosed and 0.33% (95% CI, 0.27%-0.38%) for undiagnosed. Clinician-adjudicated segmental vitiligo prevalence (sensitivity bounds) was 0.18% (0.18%-0.27%), with 0.09% (0.09%-0.12%) for diagnosed and 0.08% (0.08%-0.15%) for undiagnosed.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this survey study demonstrated that the current US population-based prevalence estimate of overall (diagnosed and undiagnosed combined) vitiligo in adults is between 0.76% (1.9 million cases in 2020) and 1.11% (2.8 million cases in 2020). Additionally, this study suggests that approximately 40% of adult vitiligo in the US may be undiagnosed. Future studies should be performed to confirm these findings.

Introduction

Vitiligo is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system causes patchy loss of skin pigmentation.1 Two forms of the disease, segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo, are well recognized. Segmental vitiligo, characterized by unilateral, localized distribution of vitiligo lesions, more often has rapid onset and stabilization with early hair follicle involvement. Nonsegmental vitiligo, characterized by bilateral distribution of vitiligo lesions on the body, more frequently has progressive onset with multiple flare-ups, later hair follicle involvement, and an unpredictable course.2,3 Segmental vitiligo is a less common form of the disease occurring in 5% to 16% of patients with vitiligo while nonsegmental vitiligo is the more common form.2 The average age of onset follows a bimodal pattern of early onset at 7.3 years and late onset at 40.5 years.4 However, segmental vitiligo tends to occur more commonly than nonsegmental vitiligo in younger children.2

Worldwide prevalence estimates of vitiligo vary widely with prevalence estimates ranging from 0.004% to 2.28%.5,6 In the United States, there is a paucity of population-based studies; however, based on the few studies that have been conducted in specific subpopulations, the prevalence estimates vary from 0.05% to 1.55%. Furthermore, these estimates are either outdated, do not include patients with undiagnosed vitiligo, or are sampled from specific subgroups of the general population.7,8,9,10,11,12

Vitiligo can have profound effects on a patient’s well-being and is often associated with other autoimmune comorbid conditions. Furthermore, because the disease course, prognosis, and treatment modalities are different between segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo, it is important to distinguish between these vitiligo forms at diagnosis.13 Therefore, it is important to gain a better understanding of the current prevalence of vitiligo among adults, particularly the prevalence of nonsegmental vitiligo compared with segmental vitiligo, along with the prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed vitiligo. This information can help inform timely diagnosis and clinical management with new and emerging therapies, inform patient access to health care, improve patient education efforts, and inform efforts to increase disease awareness. The objectives of this large, general population survey study were to estimate the point prevalence of vitiligo in the US, including diagnosed and undiagnosed vitiligo, as well as segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo, and to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of this patient population.

Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional population-based survey was conducted between December 30, 2019, and March 11, 2020. Participants who reported being diagnosed with vitiligo by a clinician (self-reported diagnosed) or reported having vitiligo by screening positive for undiagnosed vitiligo in the survey (self-reported undiagnosed) were invited to submit photographs for clinician evaluation using a teledermatology mobile health application (teledermatology app) designed and tested specifically for this study. Clinician evaluation of the photographs was conducted by vitiligo experts between February 21 and March 30, 2020. This study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board, and participants provided online consent.

Study Population

A representative sample of the US adult general population, 18 to 85 years of age, was recruited by email invitation using a stratified proportional, sampling design from a proprietary US general population research panel provided by Schlesinger Group. Stratified quotas were set to be representative of the 2017 US Census estimates with respect to age (4-85 years), gender, race, household income level, and geographic region.14,15 To be eligible for the general population research panel, participants must have had an email address and valid photograph identification, provided key demographic information, and validated email through a confirmation email link.

Based on response rates within the various census quotas, subsequent invitations were sent by email to randomly selected participants to achieve a census-balanced sample of the targeted 50 000 participants. The survey link was provided in the email. Participant compensation ranged from $2.50 for participants who did not report having vitiligo to $60 for participants who reported having vitiligo and uploaded photographs. Information for the pediatric population (4-17 years of age) was obtained through parent and/or legal guardian proxy in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. The results among adults in the US are reported herein. The results of the pediatric population will be published elsewhere.

Participant Survey

The participant survey included demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and vitiligo screening questions for all participants. Vitiligo screening questions were adapted from published screening tools, the patient-administered Vitiligo Screening Tool,16 and a self-reported questionnaire. The screening questions included an atlas of photographs developed by Phan et al17 and by expert clinicians in the field to enable identification of participants with diagnosed or undiagnosed vitiligo. A representation of the consecutive screening questions and vitiligo images that participants saw in the online survey are shown in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

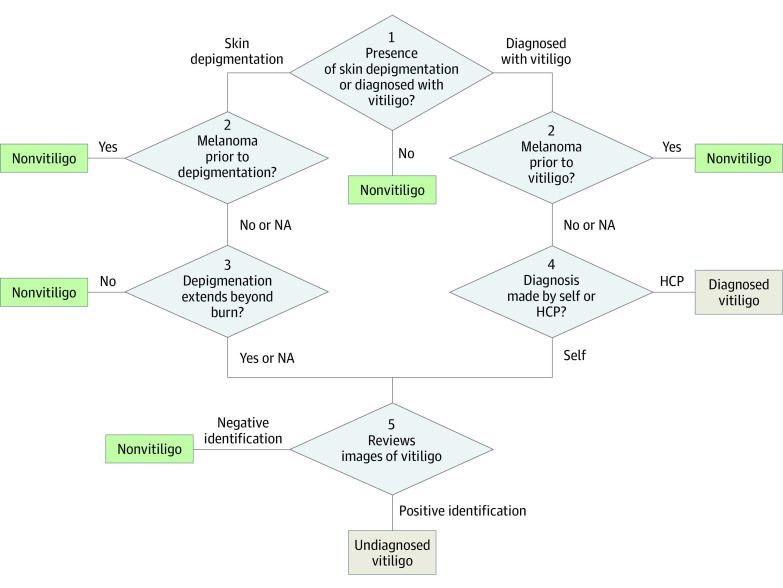

Both self-reported diagnosed participants and self-reported undiagnosed participants (Figure) were asked to complete additional questions on the laterality (bilateral or unilateral) of their lesions and vitiligo characteristics (eg, age of onset and extent of body surface area [BSA] involvement). The Self Assessment Vitiligo Extent Score was used to determine BSA involvement for participants reporting bilateral vitiligo (proxy for nonsegmental vitiligo),18 and hand or index finger units were used to measure the extent of BSA involvement for participants reporting unilateral vitiligo (proxy for segmental vitiligo).19,20

Figure. Flow of Participant Completed Vitiligo Screening Survey Questions.

HCP indicates health care professional; NA, not applicable.

Participants with self-reported diagnosed or undiagnosed vitiligo were invited to upload photographs of their lesions for clinician evaluation. Participants who consented to upload photographs were asked to download the study’s teledermatology app to their personal device (eg, smartphone). Participants were provided instructions in the app, including logging in with a unique, deidentified code; granting access to the mobile device camera; selecting a body part location for each photograph; and submitting up to 3 photographs. The teledermatology app was designed with facial recognition and blur detection to ensure clear and anonymized images by prompting participants to retake photographs when needed.

Clinician Adjudication

Three board-certified dermatologists with expertise in vitiligo (including K.E. and A.G.P.) served as adjudicators and evaluated the uploaded photographs from participants who self-reported having diagnosed or undiagnosed vitiligo. The clinicians were provided with participants’ self-reported information on age, gender, race, age of vitiligo onset, laterality, Fitzpatrick skin type (FST), and other skin conditions to assist with their evaluation. They were blinded to the participant’s report of being diagnosed or undiagnosed and independently classified each participant into 1 of 6 classifications: (1) definitely has vitiligo, (2) probably has vitiligo, (3) definitely does not have vitiligo, (4) probably does not have vitiligo, (5) unable to determine due to poor quality photographs, or (6) unable to determine due to any other reason (eg, need more photographs, need more clinical history). The 6 classifications were subsequently collapsed into 3 categories for analysis: (1) vitiligo (included classifications 1 and 2), (2) nonvitiligo (included classifications 3 and 4), and (3) indeterminate (included classifications 5 and 6).

Final vitiligo adjudication was made by clinician majority, defined by at least 2 of the 3 clinicians agreeing on the categorization of vitiligo, nonvitiligo, or indeterminate. If there was no majority, the case was categorized as indeterminate. Clinicians further evaluated the self-reported laterality (ie, lesions on 1 or both sides of the body) of the vitiligo lesions and provided their own assessment of nonsegmental vitiligo or segmental vitiligo based on photographs and following the consensus classification from the 2011 Vitiligo European Taskforce consensus conference for segmental vitiligo.21 Agreement between the clinicians was assessed using the Fleiss (unweighted) κ coefficient.22,23,24

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Descriptive statistics were calculated for participant demographic and clinical characteristics and reported overall and for the participants with self-reported diagnosed and self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo. Comparisons between the participants with self-reported diagnosed and self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo were assessed using t test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. The level of significance was 2-sided P = .05 and is presented for descriptive purposes. The sample size for this study was chosen to provide reasonable precision around the estimate of prevalence and not to examine differences in these characteristics between the diagnosed and undiagnosed vitiligo participants.

Self-reported point prevalence estimates of vitiligo were calculated as the percentage of participants who self-reported vitiligo. Clinician-adjudicated point prevalence estimates of vitiligo were calculated as the prevalence of self-reported vitiligo weighted by the proportion of participants with self-reported vitiligo that was in agreement with the clinician adjudication. Indeterminate cases were not included in either the numerator nor denominator for the clinician-adjudicated prevalence (base case scenario). Two sensitivity analyses were conducted in which indeterminate diagnoses were recategorized as: (1) vitiligo diagnoses (upper-bound scenario) and (2) nonvitiligo diagnoses (lower-bound scenario).

Additionally, self-reported and clinician-adjudicated point prevalence estimates were calculated separately for participants reporting bilateral (nonsegmental proxy) and unilateral (segmental proxy) vitiligo lesions. To improve the representativeness of the estimates, all point prevalence estimates were weighted using raked weights to adjust the census-based sample to 2020 US Census estimates and mitigate differential representation across key subgroups (eg, age groups, gender, race) by using an iterative proportional fitting process.25,26

Results

Participants

A total of 322 240 individuals were invited to take part in the survey, of which 60 524 (18.8%) responded (Table 1). Approximately one-third (n = 19 636 [32.4%]) of those who responded were not eligible, with the most common reason (n = 10 630 [54.1%]) being that the US Census quota (ie, age, gender, race, geographic region, income level) was already met.

Table 1. Participant Attrition.

| Invited participants | No. (%) (n = 322 240) |

|---|---|

| Responded to invitation | 60 524 (18.8) |

| Eligible adult participants | 40 888 (67.6) |

| Not eligible | 19 636 (32.4) |

| Respondent US Census population quota already filled | 10 630 (54.1) |

| Duplicate respondent or ineligible responsea | 4524 (23.0) |

| Survey not completed | 4024 (20.5) |

| Age <18 or >85 y | 458 (2.3) |

An ineligible response was defined as a respondent who selected having all listed comorbidities in a potential attempt to participate in the survey.

The 40 888 eligible adult participants aged 18 to 85 years were generally representative of the estimated 2017 US Census population (Table 2). The mean (SD) age was 44.9 (17.4) years, and 23 170 (56.7%) were female. The majority (n = 30 428 [74.4%]) identified themselves as White, and 4225 (10.3%) participants identified themselves of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. The greatest number of participants (n = 16 265 [39.8%]) resided in the US South geographic region.

Table 2. Characteristics of Adult Study Participants.

| Characteristic | 2017 US Census population, %a | All adult participants (N = 40 888) | Self-reported vitiligo, mean (95% CI) | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed (n = 314) | Undiagnosed (n = 249) | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | Not available | 44.9 (17.4) | 42.8 (40.9-44.6) | 39.3 (37.4-41.2) | .01 |

| Age, No. (%), y | |||||

| 4-17 | 19.4 | NA | NA | NA | .03 |

| 18-24 | 10.4 | 6282 (12.6) | 57 (14.8) | 47 (14.4) | |

| 25-34 | 14.7 | 7346 (14.7) | 59 (15.4) | 60 (18.4) | |

| 35-44 | 13.6 | 6813 (13.6) | 51 (13.3) | 56 (17.2) | |

| 45-54 | 14.4 | 7043 (14.1) | 61 (15.9) | 44 (13.5) | |

| 55-64 | 13.6 | 6813 (13.6) | 50 (13.0) | 21 (6.4) | |

| 65-85 | 13.9 | 6591 (13.2) | 36 (9.4) | 21 (6.4) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Female | 50.8 | 23 170 (56.7) | 191 (60.8) | 135 (54.2) | .12 |

| Male | 49.2 | 17 718 (43.3) | 123 (39.2) | 114 (45.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.8 | 367 (0.9) | 4 (1.3) | 12 (4.8) | .09 |

| Asian | 5.4 | 1481 (3.6) | 13 (4.1) | 10 (4.0) | |

| Black or African American | 12.7 | 5253 (12.8) | 49 (15.6) | 47 (18.9) | |

| Multiracialc | 3.1 | 1188 (2.9) | 18 (5.7) | 19 (7.6) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.2 | 85 (0.2) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | |

| White | 73.0 | 30 428 (74.4) | 215 (68.5) | 149 (59.8) | |

| Other | 4.8 | 2086 (5.1) | 13 (4.1) | 12 (4.8) | |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 17.6 | 4225 (10.3) | 48 (15.3) | 53 (21.3) | .07 |

| Income level, $, No. (%) | |||||

| 0-14 999 | 11.5 | 5257 (12.9) | 15 (4.8) | 32 (12.9) | .01 |

| 15 000-24 999 | 9.8 | 4440 (10.9) | 32 (10.2) | 24 (9.6) | |

| 25 000-34 999 | 9.5 | 4172 (10.2) | 24 (7.6) | 30 (12.0) | |

| 35 000-49 999 | 13.0 | 5621 (13.7) | 42 (13.4) | 35 (14.1) | |

| 50 000-74 999 | 17.7 | 7566 (18.5) | 67 (21.3) | 55 (22.1) | |

| 75 000-99 999 | 12.3 | 5125 (12.5) | 55 (17.5) | 28 (11.2) | |

| 100 000-149 999 | 14.1 | 5099 (12.5) | 54 (17.2) | 26 (10.4) | |

| 150 000-199 999 | 5.8 | 1917 (4.7) | 13 (4.1) | 10 (4.0) | |

| ≥200 000 | 6.3 | 1691 (4.1) | 12 (3.8) | 9 (3.6) | |

| US Region, No. (%) | |||||

| South | 38.1 | 16 265 (39.8) | 132 (42.0) | 106 (42.6) | .79 |

| West | 23.8 | 8085 (19.8) | 67 (21.3) | 51 (20.5) | |

| Midwest | 20.9 | 9084 (22.2) | 74 (23.6) | 53 (21.3) | |

| Northeast | 17.2 | 7454 (18.2) | 41 (13.1) | 39 (15.7) | |

| Characteristics of participants with vitiligo | |||||

| Fitzpatrick skin type, No. (%) | |||||

| I | NA | NA | 10 (3.2) | 13 (5.2) | .43 |

| II | NA | NA | 73 (23.2) | 60 (24.1) | |

| III | NA | NA | 123 (39.2) | 96 (38.6) | |

| IV | NA | NA | 91 (29.0) | 74 (29.7) | |

| V | NA | NA | 16 (5.1) | 6 (2.4) | |

| VI | NA | NA | 1 (0.3) | 0 | |

| Age at onset | NA | NA | 27.6 (25.7-29.5) | 25.0 (23.0-27.0) | .06 |

| Self-reported presentation, No. (%) | |||||

| Unilateral | NA | NA | 117 (37.3) | 135 (54.2) | <.001 |

| Bilateral | NA | NA | 197 (62.7) | 114 (45.8) | |

| Facial involvement, No. (%)d | NA | NA | 140 (71.1) | 75 (65.8) | .33 |

| BSA, % | NA | NA | |||

| Unilaterale | NA | NA | 0.62 (0.45-0.78) | 0.55 (0.38-0.71) | .55 |

| Bilaterald | NA | NA | 11.46 (9.05-13.87) | 7.68 (5.59-9.77) | .04 |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; NA, not applicable.

US Census estimates are based on the general population that includes adults and children. Percentages for age categories have been recalibrated to total 100% among those 4 to 85 years of age.

P values are from t test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables (self-reported diagnosed vitiligo vs self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo).

Multiracial was captured indirectly on the participant survey; if more than 1 race category was selected then the participant was considered multiracial and is included only in the multiracial category.

Measured using the Self Assessment Vitiligo Extent Score among participants who reported bilateral presentation (n = 311). One participant did not have any active lesions and, therefore, was treated as missing and not included in the facial involvement denominator or the mean BSA percentage.

Measured using hands and fingers representing 0.81% and 0.081% BSA in male participants, respectively, and 0.67% and 0.067% BSA in female participants, respectively, among participants who reported unilateral presentation (n = 251). One participant reported BSA involvement of 200 hands (ie, BSA >100%) and, therefore, was treated as missing and not included in the mean BSA percentage.

Prior diagnosis with vitiligo by a clinician (self-reported diagnosed vitiligo) was reported by 314 adults. An additional 249 adults screened positive for vitiligo in the survey (self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo) (Table 2). Compared with participants with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo, participants with self-reported diagnosed vitiligo were older on average (42.8 vs 39.3 years; P = 0.01 [all adult participants, 44.9 years]), had a greater percentage of female (191 [60.8%] vs 135 [54.2%]; P = .12 [all adult participants, 23 170 (56.7%)]) and White participants (215 [68.5%] vs 149 [59.8%]; P = .03 [all adult participants, 30 428 (74.4%)]), and a lower percentage of participants of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (48 [15.3%] vs 53 [21.3%]; P = .07 [all adult participants, 4225 (10.3%)]) (Table 2).

The mean age at vitiligo onset was 27.6 years for participants with self-reported diagnosed vitiligo compared with 25.0 years for participants with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo (P = 0.06; Table 2). More participants with self-reported diagnosed vitiligo reported bilateral presentation compared with participants with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo (197 [62.7%] vs 114 [45.8%]; P < .001). Among participants with self-reported diagnosed vitiligo, more reported facial involvement compared with participants with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo (140 [71.1%] vs 75 [65.8%]; P = .33) (Table 2). Participants with self-reported diagnosed vitiligo also reported greater mean BSA percentage compared with participants with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo for both unilateral presentation (0.62% [95% CI, 0.45%-0.78%] vs 0.55% [0.38%-0.71%]; P = .55) and bilateral presentation (11.46% [95% CI, 9.05%-13.87%] vs 7.68% [95% CI, 5.59%-9.77%]; P = 0.04). Lastly, FST distribution was similar among participants with self-reported diagnosed and self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo, with the most common being FST III (self-reported diagnosed, 123 [39.2%] vs self-reported undiagnosed, 96 [38.6%]), followed by FST IV (self-reported diagnosed, 91 [29.0%] vs self-reported undiagnosed, 74 [29.7%]) and FST II (self-reported diagnosed, 73 [23.2%] vs self-reported undiagnosed, 60 [24.1%]) (P = .44; Table 2).

Prevalence

The self-reported point prevalence of vitiligo was 1.38% (95% CI, 1.26%-1.49%), of which 0.77% (95% CI, 0.68%-0.85%) was for nonsegmental vitiligo (self-reported as bilateral) and 0.61% (95% CI, 0.53%-0.69%) was for segmental vitiligo (self-reported as unilateral) (Table 3). Following clinician adjudication of the 113 participants who agreed to participate in the expert dermatologist review of their lesions and uploaded photographs (71 self-reported diagnosed vitiligo and 42 self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo), the base case scenario point prevalence of vitiligo was 0.76% (95% CI, 0.68%-0.84%), of which 0.58% (95% CI, 0.49%-0.66%) was for nonsegmental vitiligo and 0.18% (95% CI, 0.15%-0.21%) was for segmental vitiligo. There was moderate agreement among the 3 expert dermatologists (κ = 0.52; P < .001).

Table 3. Estimates of Point Prevalence of Vitiligo.

| Participants | Vitiligo prevalence estimate, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Nonsegmental | Segmental | |

| Diagnosed and undiagnosed combineda | |||

| Self-reported | 1.38 (1.26-1.49) | 0.77 (0.68-0.85) | 0.61 (0.53-0.69) |

| Clinician adjudicatedb | 0.76 (0.68-0.84) | 0.58 (0.49-0.66) | 0.18 (0.15-0.21) |

| Boundc | |||

| Lower | 0.76 (0.67-0.84) | 0.57 (0.49-0.66) | 0.18 (0.15-0.21) |

| Upper | 1.11 (1.01-1.21) | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) | 0.27 (0.23-0.31) |

| Diagnosed | |||

| Self-reported | 0.77 (0.68-0.85) | 0.48 (0.41-0.55) | 0.28 (0.23-0.33) |

| Clinician adjudicatedb,c | 0.46 (0.39-0.52) | 0.37 (0.30-0.43) | 0.09 (0.07-0.11) |

| Boundd | |||

| Lower | 0.46 (0.39-0.52) | 0.37 (0.30-0.43) | 0.09 (0.07-0.11) |

| Upper | 0.61 (0.54-0.69) | 0.49 (0.41-0.56) | 0.12 (0.10-0.15) |

| Undiagnosed | |||

| Self-reported | 0.61 (0.54-0.69) | 0.29 (0.23-0.34) | 0.33 (0.27-0.38) |

| Clinician adjudicatedb,c | 0.29 (0.24-0.34) | 0.21 (0.15-0.26) | 0.08 (0.06-0.11) |

| Boundd | |||

| Lower | 0.29 (0.24-0.34) | 0.20 (0.15-0.26) | 0.08 (0.06-0.11) |

| Upper | 0.50 (0.43-0.57) | 0.36 (0.29-0.43) | 0.15 (0.12-0.17) |

Owing to within-group weighting, the sum of the individual diagnosed and undiagnosed estimates may differ slightly from the total estimates.

Photographs were uploaded for clinician adjudication by 71 participants with self-reported diagnosed vitiligo and 42 participants with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo. There was moderate agreement among the 3 expert dermatologists (Fleiss κ = 0.52; P < .001). Clinician-adjudicated vitiligo diagnoses were further adjudicated for nonsegmental and segmental vitiligo classification.

Nonsegmental and segmental clinician-adjudicated estimates are adjusted to account for 54.5% of self-reported segmental vitiligo diagnoses being adjudicated as segmental and 100% of self-reported nonsegmental vitiligo diagnoses being adjudicated as nonsegmental.

Sensitivity analysis results: lower bound, indeterminate diagnoses were classified as nonvitiligo diagnoses, and upper bound, indeterminate diagnoses were classified as vitiligo diagnoses.

Among diagnosed vitiligo, the self-reported point prevalence was 0.77% (95% CI, 0.68%-0.85%), of which 0.48% (95% CI, 0.41%-0.55%) was for nonsegmental vitiligo (self-reported as bilateral) and 0.28% (95% CI, 0.23%-0.33%) was for segmental vitiligo (self-reported as unilateral). Following clinician adjudication, the point prevalence was 0.46% (95% CI, 0.39%-0.52%), of which 0.37% (95% CI, 0.30%-0.43%) was for nonsegmental vitiligo and 0.09% (95% CI, 0.07%-0.11%) was for segmental vitiligo (Table 3).

Lastly, among undiagnosed vitiligo, the self-reported point prevalence was 0.61% (95% CI, 0.54%-0.69%), of which 0.29% (95% CI, 0.23%-0.34%) was for nonsegmental vitiligo (self-reported as bilateral) and 0.33% (95% CI, 0.27%-0.38%) was for segmental vitiligo (self-reported as unilateral). Following clinician adjudication, the point prevalence was 0.29% (95% CI, 0.24%-0.34%), of which 0.21% (95% CI, 0.15%-0.26%) was for nonsegmental vitiligo and 0.08% (95% CI, 0.06%-0.11%) was for segmental vitiligo (Table 3).

After the sensitivity analyses, the clinician-adjudicated prevalence remained unchanged when indeterminate diagnoses were reclassified as nonvitiligo diagnoses (lower-bound scenario) and increased when indeterminate diagnoses were reclassified as vitiligo diagnoses (upper-bound scenario) to 1.11% (from 0.76%) overall, 0.61% (from 0.46%) for diagnosed vitiligo, and 0.50% (from 0.29%) for undiagnosed vitiligo (Table 3).

Discussion

In this large population-based study of more than 40 000 adults, representative of the 2017 US general population national estimates, we found that the estimated point prevalence of vitiligo was 0.76% based on clinician adjudication and 1.38% based on self-report. These results support generalizability because we performed targeted sampling of participants that represents the 2017 US population estimates by age, gender, race, region, and household income level. Additionally, the use of raking analytic methods to further weight the sample to 2020 US population estimates when determining the point prevalence supports the generalizability of the prevalence estimates.

The estimates of point prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo were 0.46% (clinician-adjudicated base case) and 0.77% (self-reported) and fell within the range of previously published estimates of diagnosed vitiligo in the US. Specifically, 1 large, general population study in the US, conducted 4 decades ago, estimated the prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo at 0.49%.6,8 Additionally, a large database study estimated the prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo at 0.50%.7 Other studies on the prevalence in the US only focused on regional US communities (eg, control patients from a case-control study of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [prevalence estimate of 0.40%] and Arab Americans [prevalence estimate of 1.55%]).10,11 Lastly, a large administrative claims database study reported a prevalence estimate of 0.05%, which is inherently reliant on the clinician recording the diagnosis in a claim for reimbursement and, thus, is likely to underestimate the true prevalence.12

The estimates of point prevalence of undiagnosed vitiligo were 0.29% (clinician-adjudicated) and 0.61% (self-reported). These findings suggest that up to 40% of adults with vitiligo in the US may be undiagnosed. We found that among participants with undiagnosed vitiligo compared with participants with diagnosed vitiligo, there was a higher proportion who were non-White (40.2% vs 31.5%) or of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (21.3% vs 15.3%). Additionally, unilateral presentation of lesions was more common among those with self-reported undiagnosed vitiligo than among participants with diagnosed vitiligo (54.2% vs 37.3%). The estimates of unilateral presentation (ie, segmental vitiligo) among those with diagnosed vitiligo is higher than the 5% to 16% previously reported in those with vitiligo.2 To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify these trends in the undiagnosed population.

The present study also estimated the prevalence of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo for both diagnosed and undiagnosed vitiligo. The distinction between segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo is of prime importance for both patients and physicians when reporting on the prevalence of vitiligo. Indeed, patients are usually concerned by the spreading of the disease and its unpredictable course, which is the hallmark of nonsegmental vitiligo. In fact, these vitiligo forms do not behave in the same manner, and the unpredictable nature of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions in patients.27,28 Besides, this unpredictable characteristic of nonsegmental vitiligo is of most importance in the therapeutic algorithm of vitiligo.

Limitations

While this study closely represents the distribution of the US general population with respect to demographic characteristics, there is a potential for selection bias owing to internet accessibility. However, it was estimated by the American Community Survey that the percentage of households in the US with internet access was nearly 90% in 2016.29 Additionally, because the survey data were self-reported by participants and a low percentage of participants with vitiligo uploaded photographs (20.1%), the data may be subject to reporting bias. To mitigate some reporting bias, the survey questions included nonclinical terminology next to any clinical terminology, where appropriate.

Furthermore, vitiligo status was self-reported by participants and not confirmed with in-person evaluation or diagnostic testing. However, vitiligo screening questions were developed based on adaptations of published screening tools and feedback from expert dermatologists in the field. Clinician adjudication of self-reported vitiligo was also undertaken using a teledermatology app. The use of telehealth solutions is evolving in epidemiology research, and while user error and photograph quality cannot be closely controlled, advantages include the ability to scale to a large population study, retain a large sample size owing to ease of use, and standardize data collection and submission.

Clinician adjudication was performed for only 20.1% of participants who uploaded photographs, and assumptions of missing at random cannot be confirmed. Nevertheless, the clinician-adjudicated prevalence estimates of vitiligo in this study, with the inclusion of sensitivity analyses, provide a conservative and reliable estimate of the prevalence of vitiligo in the US population with lower prevalence of clinician-adjudicated vitiligo potentially accounting for bias owing to higher self-reporting. In light of the remarkably high number of participants with undiagnosed vitiligo observed in this study, future studies could potentially explore the development and validation of teledermatology apps that allow for potential diagnosis of vitiligo and encourage undiagnosed patients to seek diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusions

This survey study provides current US population-based prevalence estimates of overall (diagnosed and undiagnosed combined) vitiligo in adults between 0.76% (1.9 million cases in 2020) and 1.11% (2.8 million cases in 2020) and estimates that approximately 40% of adults with vitiligo may be undiagnosed in the US. Importantly, it also provides prevalence estimates for segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo. The high percentage of participants with undiagnosed vitiligo coupled with different rates across racial and ethnic demographic subpopulations should be studied further.

eAppendix. Vitiligo Screening Questions

References

- 1.MedlinePlus . Vitiligo. US National Library of Medicine . Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/vitiligo/

- 2.Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: a review. Dermatology. 2020;236(6):571-592. doi: 10.1159/000506103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taïeb A, Picardo M. Clinical practice: vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):160-169. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin Y, Santorico SA, Spritz RA. Pediatric to adult shift in vitiligo onset suggests altered environmental triggering. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(1):241-243. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.06.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(10):1206-1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Cai Y, Shi M, et al. The prevalence of vitiligo: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. ; American Academy of Dermatology Association; Society for Investigative Dermatology . The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490-500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MT, Roberts J. Skin conditions and related need for medical care among persons 1-74 years: United States, 1971-1974. Vital Health Stat 11. 1978;212(212):1-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Yeh C, Rabeneck L. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C among United States male veterans. Hepatology. 2002;36(6):1439-1445. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840360621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prahalad S, Shear ES, Thompson SD, Giannini EH, Glass DN. Increased prevalence of familial autoimmunity in simplex and multiplex families with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(7):1851-1856. doi: 10.1002/art.10370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Essawi D, Musial JL, Hammad A, Lim HW. A survey of skin disease and skin-related issues in Arab Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(6):933-938. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(5):958-972. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, van Geel N. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):74-84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60763-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Community Survey 1-year estimates: demographic and housing estimates. US Census Bureau . Accessed October 19, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?d=ACS%201-Year%20Estimates%20Data%20Profiles&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP05&hidePreview=false

- 15.American Community Survey 1-year estimates: selected economic characteristics. US Census Bureau . Accessed October 20, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?d=ACS%201-Year%20Estimates%20Data%20Profiles&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03&hidePreview=false

- 16.Sheth VM, Gunasekera NS, Silwal S, Qureshi AA. Development and pilot testing of a vitiligo screening tool. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307(1):31-38. doi: 10.1007/s00403-014-1515-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan C, Ezzedine K, Lai C, et al. Agreement between self-reported inflammatory skin disorders and dermatologists’ diagnosis: a cross-sectional diagnostic study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(10):1243-1244. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Geel N, Lommerts JE, Bekkenk MW, et al. ; international Vitiligo Score Working Group . Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome measure in vitiligo: the Self Assessment Vitiligo Extent Score (SA-VES). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):464-471. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes J, Clay C, Phillips M. The surface area of the hand and the palm for estimating percentage of total body surface area: results of a meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(1):76-84. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossiter ND, Chapman P, Haywood IA. How big is a hand? Burns. 1996;22(3):230-231. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00118-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezzedine K, Lim HW, Suzuki T, et al. ; Vitiligo Global Issue Consensus Conference Panelists . Revised classification/nomenclature of vitiligo and related issues: the Vitiligo Global Issues Consensus Conference. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25(3):E1-E13. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.00997.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen B, Zaebst D, Seel L. A macro to calculate kappa statistics for categorizations by multiple raters. SAS Institute Inc . 2005. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi30/155-30.pdf

- 23.Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 1971;76(5):378-382. doi: 10.1037/h0031619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. doi: 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavrakas, PJ. Raking. In: Lavrakas PJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods, 2008. Sage Publishing; 2008. doi: 10.4135/9781412963947.n433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis T. Weighting adjustment methods for nonresponse in surveys. SAS Institute Inc . Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.lexjansen.com/wuss/2012/162.pdf

- 27.Ezzedine K, Grimes PE, Meurant JM, et al. Living with vitiligo: results from a national survey indicate differences between skin phototypes. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(2):607-609. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nogueira LS, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84(1):41-45. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962009000100006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan C. Computer and internet use in the United States: 2016: American Community Survey reports. US Census Bureau . August 2018. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/ACS-39.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Vitiligo Screening Questions