Abstract

PURPOSE:

For patients with cancer who have exhausted approved treatment options and for whom appropriate clinical trials are not available, access to investigational drugs through the US Food and Drug Administration's Expanded Access (EA) program has been an alternative since the program's inception more than 30 years ago. In 2018, federal Right To Try legislation was passed in the United States, creating a second pathway—one that bypasses the US Food and Drug Administration—to obtain unapproved drugs outside of clinical trials. The use of the two programs by community medical oncologists and hematologist-oncologists has not been studied.

METHODS:

Between October 2019 and February 2020, community oncologists-hematologists from across the United States completed web-based surveys about EA and Right To Try pathways for accessing unapproved drugs for their patients. Physicians were asked about their utilization of, and perceptions of, the two programs.

RESULTS:

Of the 238 physicians who completed the survey, 46% indicated that they had attempted to gain access to an investigational drug for a patient using the EA program, whereas 14% reported attempting to use Right To Try pathway to obtain an unapproved drug for a patient. Eighty-nine percent of those who tried to use the EA program reported success in obtaining the investigational drug versus 73% of those who attempted to use the Right To Try pathway.

CONCLUSION:

Our survey found that most community oncologists-hematologists were aware of both the EA and Right To Try pathways, but there is room for improvement in understanding and utilization of the programs.

INTRODUCTION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)'s Expanded Access (EA) program, first codified into regulations in 1987, provides a means for patients with serious or life-threatening conditions to access unapproved drugs outside of clinical trials.1 For decades, this program (sometimes called compassionate use) has been a conduit for thousands of patients without alternative therapy available or the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial, to be treated with an investigational drug. For an individual patient to receive an unapproved drug via the EA pathway, the manufacturer must be willing to provide the drug, the patient's physician must obtain institutional review board (IRB) approval and apply to the FDA on the patient's behalf, and the FDA must authorize the request. Historically, FDA has authorized more than 99% of EA requests.2 Median response times for FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research division are less than 1 day for emergency EA requests, and 4 days for nonemergency requests.3

In May 2018, a second mechanism for gaining access to investigational drugs was created when the federal Right To Try Act was written into law.4 Right To Try legislation has been passed in 41 states. This law was intended to provide terminally ill patients with a different avenue to access unapproved drugs, through a pathway that bypasses the FDA. Eligible patients may appeal directly to the manufacturer for access to a drug that is in active development and has completed phase I clinical trials. Neither FDA authorization nor IRB approval is required. The number of patients receiving unapproved drug using the Right To Try pathway, the number of doses provided, the indication, and any serious adverse events observed are tracked only through an annual report that manufacturers provide to the FDA. As of June 2019 (1 year after the program was established), only two patients had received unapproved drug using the Right To Try pathway.5,6

In recent months, access to investigational medications outside of clinical trials has been featured in the mainstream media, as remdesivir and other experimental treatments for COVID-19 have been made available through the EA program.7,8 However, there is ongoing lack of understanding among patients, advocacy groups, and physicians regarding the two programs: a vocal proponent of the Right To Try program has credited the legislation with saving her life; however, the treatment she received for her bone cancer involved off-label use of an FDA-approved therapy, a scenario that would not be covered by Right To Try.9 Similarly, a report of interviews with 21 oncologists within a large academic healthcare system indicated that some of the physicians and their patients had misperceptions about the Right To Try pathway, including the belief that the law requires pharmaceutical companies to provide drug to patients.10 Although requests for antiviral products comprise the greatest proportion of EA requests, requests for oncology products are second, comprising approximately 20% of all requests between 2010 and 2014.11 Cancer is a serious or life-threatening condition, only a small fraction (< 5%) of patients with cancer participate in clinical trials,12 and often, there are few approved therapeutic options available (or the patient might have exhausted standard treatment options). With the large number of drugs in development for oncology indications (35.2% of all products in development, more than any other therapeutic area),13 it is likely that oncologists will encounter an increasing number of requests for assistance in accessing these unapproved drugs. However, the use of the EA program and the Right To Try pathway to obtain investigational drugs in the community oncology setting has not been studied. We sought to assess community oncologists' experience with, and perceptions of, both EA and Right To Try.

METHODS

Physicians in the Cardinal Health Oncology Provider Extended Network (a community of more than 7,000 medical oncologists or hematologists, practicing in a community-based or hospital-based setting in the United States) were invited to participate in a series of four live market research meetings held between October 2019 and February 2020, which addressed a wide array of topics including clinical and practice trends in oncology. To be eligible, physicians must be actively practicing, must represent practices with a broad geographic distribution across the United States, and could not have participated in another live meeting in the preceding 9 months. In a premeeting, web-based survey, the physicians were asked nine multiple-choice questions regarding their experience with the FDA's EA program and the Right To Try pathway, as well as their perceptions of the two programs. All physicians who agreed to take part in the live meeting completed the survey. All participating physicians received an honorarium for their time. Responses were summarized using descriptive statistics. This study was exempt from IRB review.

RESULTS

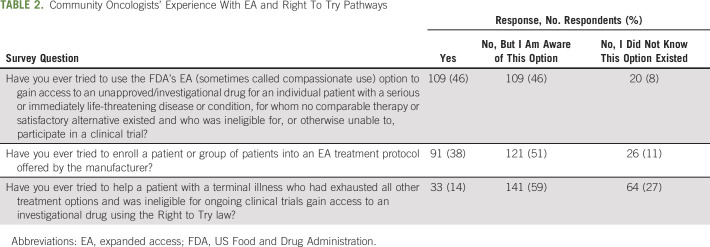

A total of 238 physicians responded to the survey (Table 1). The primary medical specialty reported was medical oncology for 32% of respondents, hematology oncology for 66%, and others for 2%. The physicians saw a median of 20 patients per day, and more than half of respondents (138, 58%) had been in practice > 20 years. The regional location of their primary practice was reported as the South for 40% of respondents, the Midwest for 22%, the West for 20%, and the Northeast for 18%.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

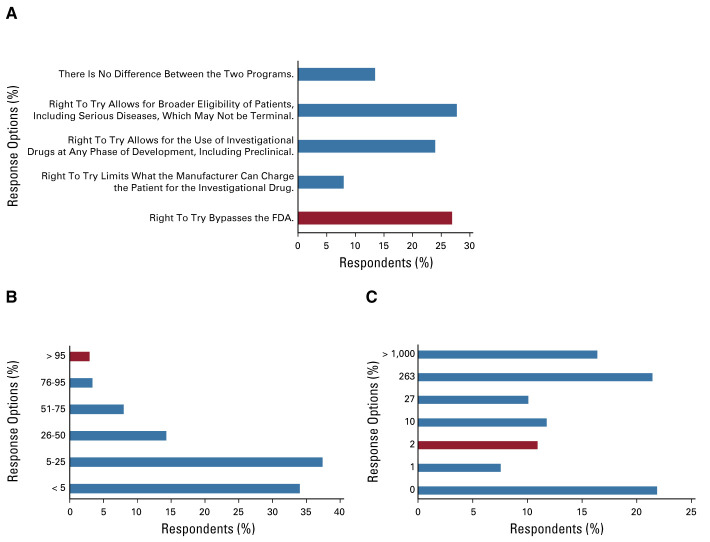

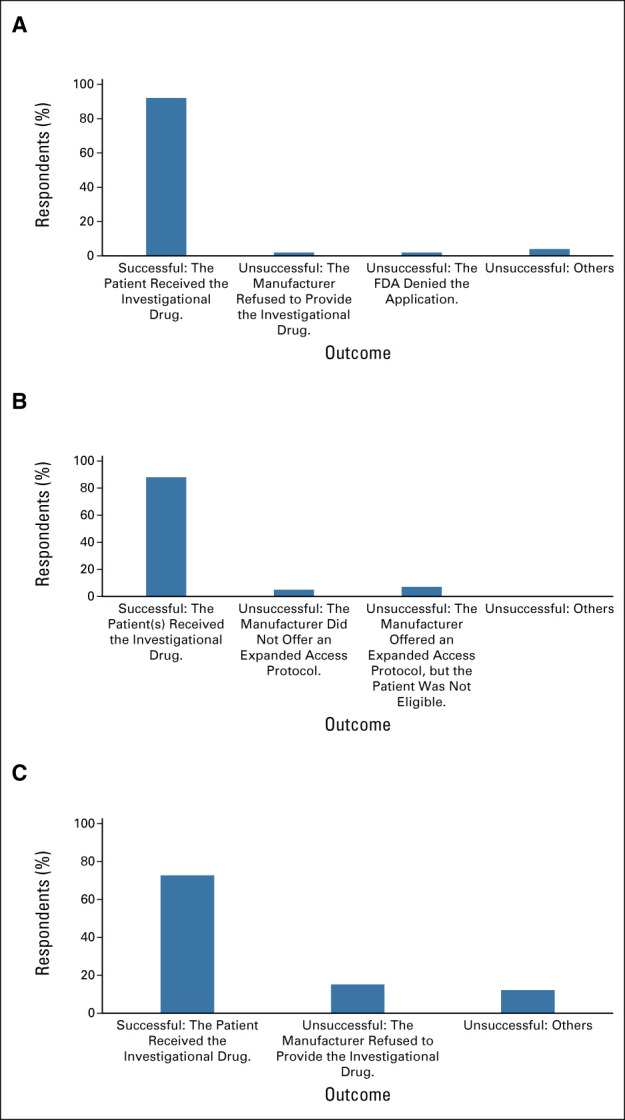

The community oncologists were first asked about their experience with, and awareness of, the EA and Right To Try programs (Table 2). Of the 238 respondents, 109 (46%) reported that they had attempted to access unapproved drugs for their patients via the EA program, 91 (38%) reported that they had tried to enroll a patient or a group of patients into an EA treatment protocol for an investigational drug offered by the manufacturer, and 33 (14%) reported that they had attempted to access unapproved drugs for their patients via the Right To Try pathway. The community oncologists who indicated they had tried to use the programs were then asked about their success in obtaining investigational drugs for their patients (or reasons for failure if unsuccessful) (Fig 1). For those who indicated that they had tried to use the EA pathway for an individual patient, 97 (89%) reported success in obtaining the investigational drug. Of those who tried to enroll a patient or a group of patients into an EA treatment protocol for an investigational drug offered by the manufacturer, 84 (92%) were successful. For those who indicated that they had tried to use the Right To Try pathway, 24 (73%) reported success in obtaining the investigational drug for their patient.

TABLE 2.

Community Oncologists' Experience With EA and Right To Try Pathways

FIG 1.

Outcomes of community oncologists' use of EA and Right To Try pathways. (A) Individual patient EA IND, (B) treatment protocol IND, and (C) Right To Try. EA, expanded access; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IND, Investigation New Drug application.

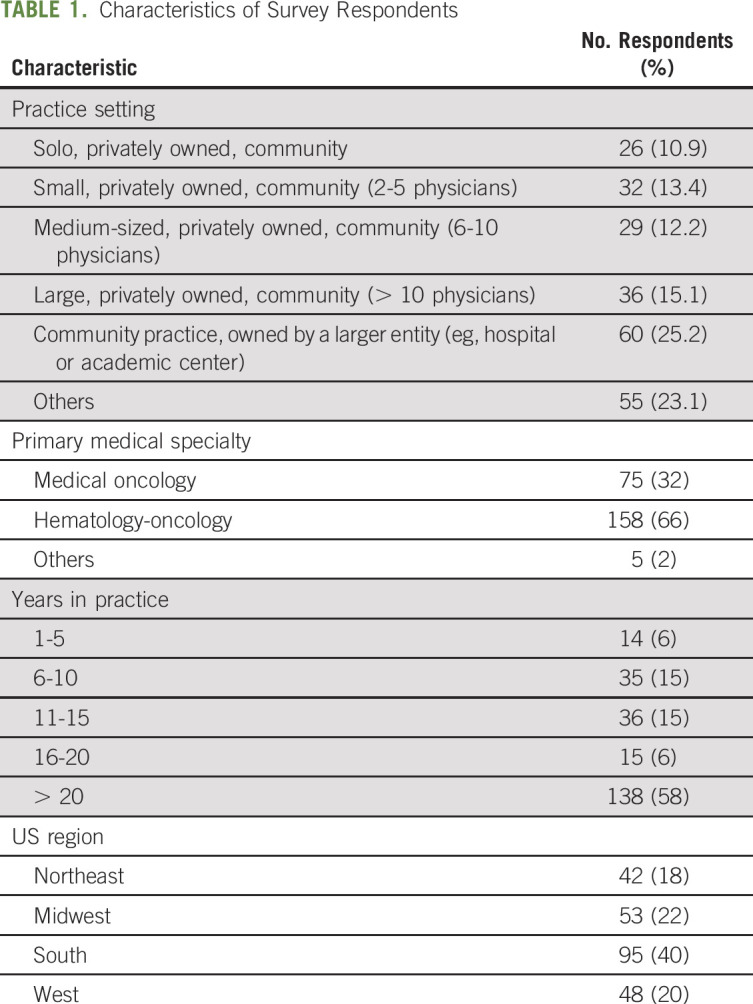

Three survey questions were intended to gauge the respondents' perceptions of the two programs (Fig 2). When asked to identify the main difference between the EA and Right To Try programs, 64 respondents (27%) chose the correct option (Right To Try bypasses the FDA). When asked to identify the percentage of individual patient EA applications that the FDA has approved historically, seven respondents (3%) chose the correct option (> 95%). Finally, when asked how many patients had accessed investigational drugs using Right to Try as of June 2019, 26 respondents (11%) chose the correct option (two).

FIG 2.

Community oncologists' experience with EA and Right To Try pathways. (A) To your knowledge, what is the main difference between accessing investigational drugs for an individual patient through the FDA's EA program and the Right To Try law? (Correct answer is red bar.) (B) To your knowledge, historically, what percentage of individual patient EA applications has the FDA approved? (Correct answer is red bar.) (C) The Right To Try legislation was signed into law in May 2018. How many patients do you estimate to have accessed investigational drugs using Right To Try as of June 2019 (correct answer is red bar)? EA, expanded access; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

DISCUSSION

Less than half of community oncologists surveyed have tried to use the FDA's EA pathway to gain access to an investigational drug for a patient or a group of patients, but those who tried had a high rate of success (≈90%). Compared with hematology oncologists, a greater proportion of medical oncologists had experience with EA for an individual patient (53% of medical oncologists v 42% of hematology oncologists, P = .01). Only 3% of all respondents reported having their request denied by the FDA, which is consistent with published rates of FDA approval of individual EA requests.2 In 5% of cases, individual EA requests were unsuccessful because the manufacturer did not provide the drug.

A smaller proportion (14%) of community oncologists surveyed have attempted to use the Right To Try pathway to obtain an investigational drug to treat their patient. Of these, 73% were successful in obtaining the drug for their patient, whereas in 15% of cases, the manufacturer did not provide the drug. This demonstrates that, in our sample, taking FDA out of the equation did not improve success rates in gaining access to unapproved drugs. Nearly all community oncologists surveyed underestimated the rate of FDA approval of individual EA requests, and many overestimated the number of patients who had received drug through the Right To Try pathway. Only about one quarter of respondents could identify the main difference between the two programs. These findings suggest that although respondents were generally familiar with the pathways to obtaining investigational drugs, understanding of the details was poor.

In light of this knowledge gap, some fundamentals of the programs are reviewed herein. For both pathways, the drug manufacturer must be a willing partner in the process to allow access to investigational drugs. Neither program compels the manufacturer to provide the drug. No data are available on the number of requests that manufacturers receive or the time it takes for them to respond: there is no public reporting for either of these metrics, for either program. However, Caplan et al14 provide some insight into the experience of an advisory committee convened to provide recommendations on EA for the manufacturer Janssen's (then unapproved) oncology drug daratumumab. During a 19-month period, 324 individual patient requests for unapproved daratumumab were received globally; 144 of these were screened out based on eligibility criteria (eg, the patient had a primary diagnosis or comorbidities that had not been studied with the drug, and therefore, the benefit and/or risk to the patient was unfavorable or unknown; the patient had not exhausted all available approved therapies; the patient was eligible to participate in a clinical trial; etc). Of the remaining 180 requests that were reviewed by the committee, 165 were approved.14 Thus, in this example, approximately half of the EA requests received by the manufacturer were approved. Why would a manufacturer choose not to provide investigational drug to fulfill an EA or Right To Try request? One concern may be the possibility of legal liability. Right To Try legislation provides broad liability protection for manufacturers (and prescribers, barring gross negligence or misconduct) who provide investigational drug to patients.4 EA provides no such protection, although there have been no reported cases of legal action taken against manufacturers related to provision of unapproved drugs via EA.11 A second concern may be the possibility that the clinical development program will be jeopardized. Right To Try legislation mandates that clinical outcomes may not adversely affect FDA review or approval of the investigational drug (unless critical to safety or requested by the manufacturer).4 Although this is not explicitly stated in EA guidance, a review conducted by FDA of 10,939 EA requests over a 10-year period found just two instances where a drug development program was placed on clinical hold because of adverse events that occurred under EA (in both cases, holds were eventually lifted).15 A manufacturer may also be reluctant to fulfill EA or Right To Try requests because there may be a limited supply of the drug, which they wish to conserve for clinical trial purposes. Finally, there is an administrative burden associated with supporting the requests.

Access to unapproved drugs does not guarantee that the patient receiving the drug will benefit. It is well-established that only a fraction of the drugs in development will ultimately meet the FDA's statutory evidence requirements. A recent study found that only 13.8% of drugs in clinical trials were eventually approved by the FDA; for oncology drugs, this figure was 3.4%.16 A review of EA requests received by the FDA between 2010 and 2014 found that 33% of all the investigational drugs requested were approved by the FDA by 5 years after initial submission.11 The risk to the patient in this scenario is considerable, not only in terms of the very real possibility of lack of efficacy of the drug but also in terms of unknown adverse effects, which may result in patient harm. With limited clinical data available with respect to the drug's safety, physicians may not be able to anticipate and prevent or mitigate these adverse events. Although informed consent is required for both pathways, what comprises informed consent in the case of Right To Try is undefined. For EA, informed consent must meet the requirements outlined in the Code of Federal Regulations (ie, it must include, in language the patient understands, a description of potential benefits and risks of the therapy, alternative treatments available, etc),17 and the form must be reviewed by an IRB. Thus, the additional safeguards of IRB and FDA review afforded by the EA option are in the patient's best interest. These concerns and others have been voiced by ethicists, patient groups, pharmaceutical companies, and professional societies (including ASCO).18-24

It is encouraging to note that awareness of the EA program was high among the community oncologists we surveyed: only about 10% reported that they did not know that this option existed (v 27% who reported that they were unaware of the Right To Try option). In recent years, several efforts have been undertaken to promote awareness of the EA program and simplify the process. The 21st Century Cures Act, passed in December 2016, included a requirement for pharmaceutical companies to publicly provide their policies, procedures, and contact information for EA requests, if they offer EA.25 The Final Rule for Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission, which went into effect in January 2017, requires pharmaceutical companies to provide information about the availability of EA when registering a trial for an investigational drug on clinicaltrials.gov.26 A revised, simplified FDA Form 3926 (Individual Patient Expanded Access Application) was created; the new form is two pages long and can be completed in 45 minutes.27 Additionally, a physician submitting the new form can request that a single IRB member (the chairperson or delegate) review the application, for the purpose of expediting the process. Finally, FDA launched a pilot program in June 2019 (Project Facilitate) to assist oncology healthcare providers with requesting access to investigational drugs for their patients through EA.28

Clinical trial enrollment is typically recommended for patients with cancer who have exhausted approved therapies. However, eligibility criteria for both EA and Right To Try require that patients are unable to participate in a clinical trial involving the investigational drug for which they are requesting access. Since clinical trials offer the benefit of rigorous data collection and safety reporting in addition to the patient protections through IRB oversight and informed consent, finding a clinical trial for another investigational agent in the appropriate indication may be a preferable first step before EA or Right To Try. If no clinical trials are available or the patient is ineligible, attempting to gain access to an investigational drug outside of clinical trials may be an appropriate next step. This decision resides with the patient and their physician and is contingent on the physician's assessment that the potential benefits of treatment with the investigational drug outweigh the potential risks for the patient. Patients pursuing this course, especially those who are nearing the end of their life, may have unrealistic expectations about the likelihood that the treatment to extend or improve the quality of their life. This decision may lead to delays in appropriate palliative care and unanticipated out-of-pocket costs to patients (both for the drug and for care not covered by insurance). Oncologists should be prepared to explain these potential risks and discuss the merits and limitations of both the EA and Right To Try programs with patients requesting access to unapproved drug outside clinical trials.

This survey serves as a temperature check for awareness and utilization of EA and Right To Try among community oncologists. This is especially important as more than 50% of cancer care is rendered in the community,29 and these physicians are less likely to have access to clinical trials and/or patients may be less likely to travel long distances to large centers to participate. We found that, similar to academic oncologists,10 community oncologists' embrace of Right To Try was tepid. Right To Try may provide additional options for certain patients if trial participation is not an option because of availability, access, or eligibility barriers. However, we would add a cautionary note regarding this pathway: in addition to lacking the protections of EA, it may be commercialized, potentially resulting in the exploitation of vulnerable patients.30

To our knowledge, this is the first survey of community oncologists regarding their experience in obtaining unapproved drugs to treat their patients and their knowledge of the FDA's EA program and the Right To Try pathway. This investigation also provides the first report of community oncologists' attempts to use Right To Try. Our results highlight that although awareness of the programs is high, there is room for improvement in understanding of the differences between EA and Right To Try. Future investigations will evaluate changes in oncologists' perceptions and experience with the two programs over time.

Marjorie E. Zettler

Employment: Cardinal Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health, Lilly

Yolaine Jeune-Smith

Employment: Cardinal Health

Bruce A. Feinberg

Employment: Cardinal Health

Leadership: Cardinal Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health

Eli G. Phillips Jr

Employment: Cardinal Health, Express Scripts

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health

Ajeet Gajra

Employment: Cardinal Health

Leadership: Cardinal Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Administrative support: Ajeet Gajra

Provision of study materials or patients: Ajeet Gajra

Collection and assembly of data: Marjorie E. Zettler

Data analysis and interpretation: Marjorie E. Zettler, Bruce A. Feinberg

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Expanded Access and Right To Try Requests: The Community Oncologist’s Experience

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Marjorie E. Zettler

Employment: Cardinal Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health, Lilly

Yolaine Jeune-Smith

Employment: Cardinal Health

Bruce A. Feinberg

Employment: Cardinal Health

Leadership: Cardinal Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health

Eli G. Phillips Jr

Employment: Cardinal Health, Express Scripts

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health

Ajeet Gajra

Employment: Cardinal Health

Leadership: Cardinal Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Cardinal Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Expanded access to investigational drugs for treatment use. Fed Reg 74:40900, 2009. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2009/08/13/E9-19005/expanded-access-to-investigational-drugs-for-treatment-use [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and Drug Administration : Expanded access (compassionate use) submission data, 2015-2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/expanded-access/expanded-access-compassionate-use-submission-data

- 3.Jarow JP, Lurie P, Ikenberry SC, et al. : Overview of FDA's expanded access program for investigational drugs. Ther Innov Regul Sci 51:177-179, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Law 115-176, 115th Congress. S.204—Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right To Try Act of 2017. 2018. https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ176/PLAW-115publ176.htm

- 5.Brennan Z: The first patient has been treated under the controversial “right to try” law. 2019. https://endpts.com/the-first-patient-has-been-treated-under-the-controversial-right-to-try-law/

- 6.Florko N: Prominent “right-to-try” advocate is getting treatment under the new law. 2019. https://www.statnews.com/2019/02/05/one-right-to-try-advocate-is-getting-treatment-under-the-new-law/

- 7.Dearment A: FDA chief highlights Gilead drug's availability under compassionate use for Covid-19. 2020. https://medcitynews.com/2020/03/fda-chief-highlights-gilead-drugs-availability-under-compassionate-use-for-covid-19/?rf=1

- 8.Thomas K, Kolata G: President Trump received experimental antibody treatment. The New York Times, October 2, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/02/health/trump-antibody-treatment.html [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan W: Natalie Harp said Trump saved her life. Experts doubt that's true. The Washington Post, August 20, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/08/25/natalie-harp-bone-cancer-trump/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith C, Stout J, Adjei AA, et al. : “I think it's been met with a shrug”: Oncologists' views toward and experiences with Right-to-Try. J Natl Cancer Inst:djaa137, 2020. 10.1093/jnci/djaa137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee AE, Markon AO, Chan-Tack KM, et al. : How often are drugs made available under the Food and Drug Administration's expanded access process approved? J Clin Pharmacol 57:S136-S142, 2017. (suppl 10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilsky RL: Finding the evidence in real-world evidence: Moving from data to information to knowledge. J Am Coll Surg 224:1-7, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pharmaprojects (Informa UK Ltd) : Pharma R&D annual review 2019. https://pharmaintelligence.informa.com/∼/media/informa-shop-window/pharma/2019/files/whitepapers/pharma-rd-review-2019-whitepaper.pdf

- 14.Caplan A, Bateman-House A, Waldstreicher J, et al. : A pilot experiment in responding to individual patient requests for compassionate use of an unapproved drug: The Compassionate Use Advisory Committee (CompAC). Ther Innov Regul Sci 53:243-248, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarow JP, Lemery S, Bugin K, et al. : Expanded access of investigational drugs: The experience of the Center of Drug Evaluation and Research over a 10-year period. Ther Innov Regul Sci 50:705-709, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong CH, Siah KW, Lo AW: Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics 20:273-286, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Drug Administration : 21 CFR 50, subpart B—Informed consent of human subjects. 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=50&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:1.0.1.1.20.2

- 18.Lynch HF, Zettler PJ, Sarpatwari A: Promoting patient interests in implementing the Federal Right to Try Act. JAMA 320:869-870, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman-House A, Robertson CT: The Federal Right to Try Act of 2017—A wrong turn for access to investigational drugs and the path forward. JAMA Intern Med 178:321-322, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joffe S, Lynch HF: Federal Right-to-Try legislation—Threatening the FDA's public health mission. N Engl J Med 378:695-697, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Organization for Rare Disorders : 83 patient and provider organizations remain opposed to Right to Try legislation. 2018. https://rarediseases.org/83-patient-provider-organizations-remain-opposed-right-try-legislation/

- 22.Pfizer Inc : Pfizer's position on federal Right to Try legislation. 2019. https://pfe-pfizercom-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Policy_Position%20_Right_to_Try_Federal_Legislation_2019.pdf

- 23.Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson : Janssen policy: Evaluating and responding to pre-approval access requests for investigational medicines. 2018. http://www.janssen.com/sites/www_janssen_com/files/janssen_policy_evaluating_responding_preapproval_requests_022018.pdf

- 24.American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on access to investigational drugs. April 4, 2017. https://www.asco.org/about-asco/press-center/news-releases/asco-releases-position-statement-access-investigational-drugs

- 25.Public Law 114–255, 114th Congress. The 21st Century Cures Act. 2016. https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ255/PLAW-114publ255.pdf

- 26.Clinical trials registration and results information submission. Fed Reg 81:64981, 2016. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22129/clinical-trials-registration-and-results-information-submission [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Food and Drug Administration : Individual patient expanded access applications: Form FDA 3926. Guidance for industry. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/media/91160/download

- 28.Food and Drug Administration : Project facilitate. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-facilitate

- 29.Community Oncology Alliance : Fact sheet: What is community oncology?. https://communityoncology.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/What-is-Comm-Onc.pdf

- 30.Lee SW, Hurst DJ: Ethical concerns regarding private equity in Right to Try in the USA. Lancet Oncol 21:1260-1262, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]