Abstract

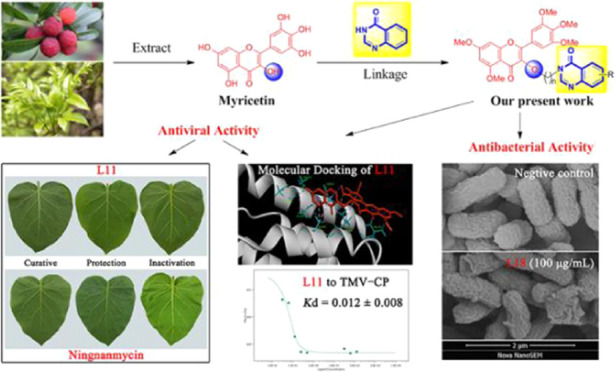

Plant bacteria such as Xanthomonas axonopodispv. citri (Xac), Pseudomonas syringaepv. actinidiae (Psa), Xanthomonas oryzaepv. oryzae (Xoo), and tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) have created huge obstacles to the global trade of food and economic crops. However, traditional chemical agents used to control these plant diseases have gradually become disadvantageous due to long-term irregular use. Therefore, finding new and efficient antibacterial and antiviral agents is becoming imperative. In this study, a series of myricetin derivatives containing a quinazolinone moiety were designed and synthesized, and the antibacterial and antiviral activities of these compounds were evaluated. The bioassay results showed that some target compounds exhibited good antibacterial activities in vitro and antiviral activities in vivo. Among them, the median effective concentration (EC50) value of compound L18 against Xac was 16.9 μg/mL, which was better than those of the control drugs bismerthiazol (BT) (62.2 μg/mL) and thiodiazole copper (TC) (97.5 μg/mL). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results confirmed that compound L18 inhibited the growth of Xac by affecting the morphology of cells. Microscale thermophoresis (MST) test results indicated that the dissociation constant (Kd) value of compound L11 against TMV-CP was 0.012 μM, which was better than that of the control agent ningnanmycin (2.726 μM). This study reveals that myricetin derivatives containing a quinazolinone moiety are potential antibacterial and antiviral agents.

1. Introduction

Plant pathogens are invisible foe of crop production and economic trade all over the world. It can result in a loss of crop yield of 20–30% annually.1−4 Plant bacteria (Xac, Psa, Xoo) and plant viruses (TMV) are highly infectious in food and cash crops, which are the two main pathogens of plant infectious diseases.5 Traditional chemical agents used to prevent and control these plant diseases, such as BT, TC, and ningnanmycin, have increased the drug resistance of crops due to their long-term large-scale use.6,7 In addition, the low degradation rate and high toxicity of traditional agents have also brought a certain degree of burden to the environment.8,9 Therefore, it has become an urgent need to find antibacterial and antiviral agents with low toxicity, high efficiency, and environmentally friendly.

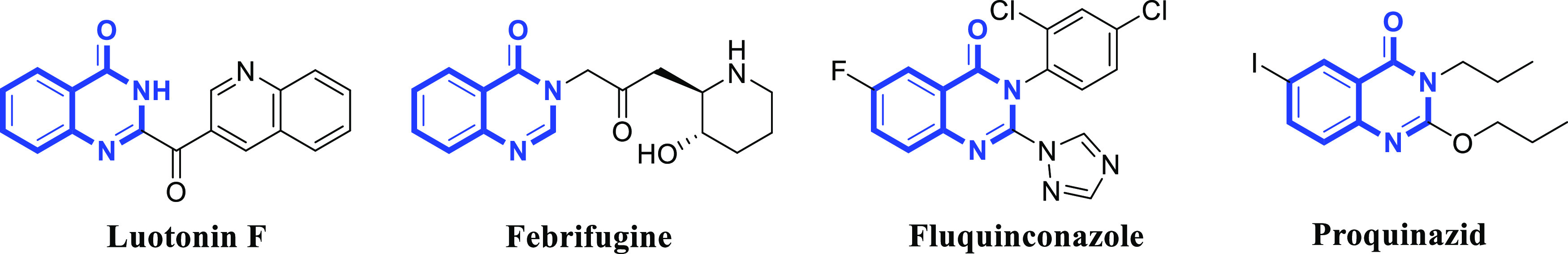

Quinazolinone is an important class of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds, whose skeleton is composed of benzene and pyrimidine, and widely exists in a variety of natural alkaloids, such as luotonin F and febrifugine (Figure 1).10,11 A number of studies have shown that quinazolinone derivatives have anticancer,12 antioxidant,13 antibacterial,14 antitumor,15 and other pharmacological activities. In recent years, quinazolinones have gradually attracted the attention of scholars in the creation of new pesticides. The existing research results showed that quinazolinone derivatives have antiviral,16,17 antibacterial,18 antifungal,19 and other activities in the prevention and treatment of plant diseases. As an important pharmacophore of the antibacterial agents, such as fluquinconazole and proquinazid (Figure 1), quinazolinone has received high attention due to its simple and variable structure.20

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of several natural products and commercial drugs containing the quinazolinone backbone.

Myricetin (3,5,7-trihydroxy-2-(3′,4′,5′-trihydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one) is a natural flavonol compound that can be found in many kinds of plants, such as bayberry, vine tea, grape, and pomegranate.21 Many reports indicated that myricetin and its derivatives showed anti-inflammatory,22,23 antitumor,24 antioxidant,25 antibacterial,26 and other activities. Despite its high research interest, myricetin has been rarely studied and applied in pesticides. Based on this, our group obtained some myricetin derivatives with excellent antibacterial and antiviral activities in the previous work, which provided new ideas for the creation of new pesticides.27−30

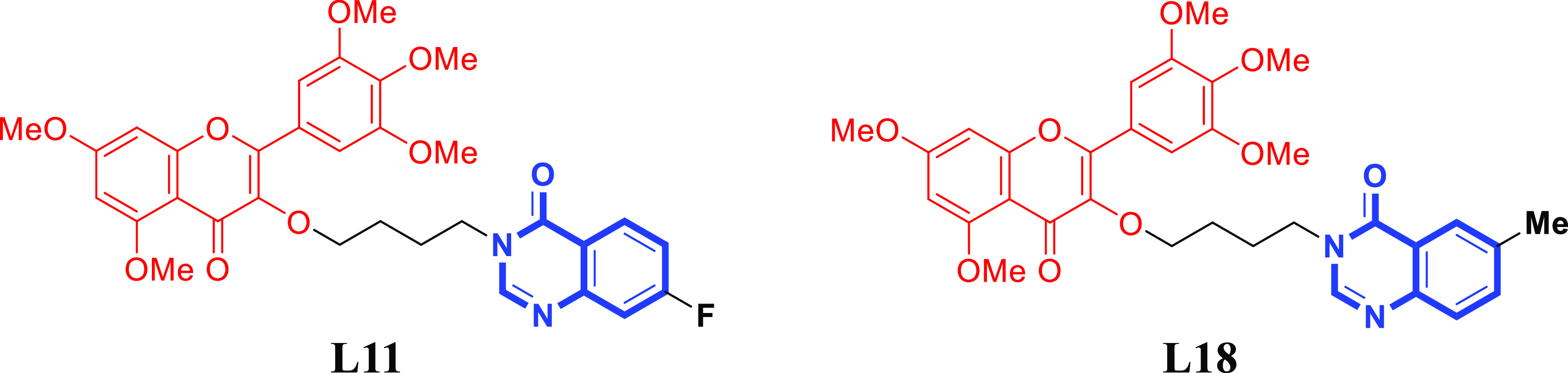

In this paper, the principle of active splicing was used to introduce the quinazolinone skeleton with multiple biological activities into the structure of the natural product myricetin. A series of myricetin derivatives containing a quinazolinone moiety were designed and synthesized. The turbidimetric method and the half-leaf blight spot method were used to evaluate the antibacterial and antiviral activities of the synthesized compounds, and the preliminary mechanism of the highly active compounds (Figure 2) was studied.

Figure 2.

Structures of compounds L11 and L18.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

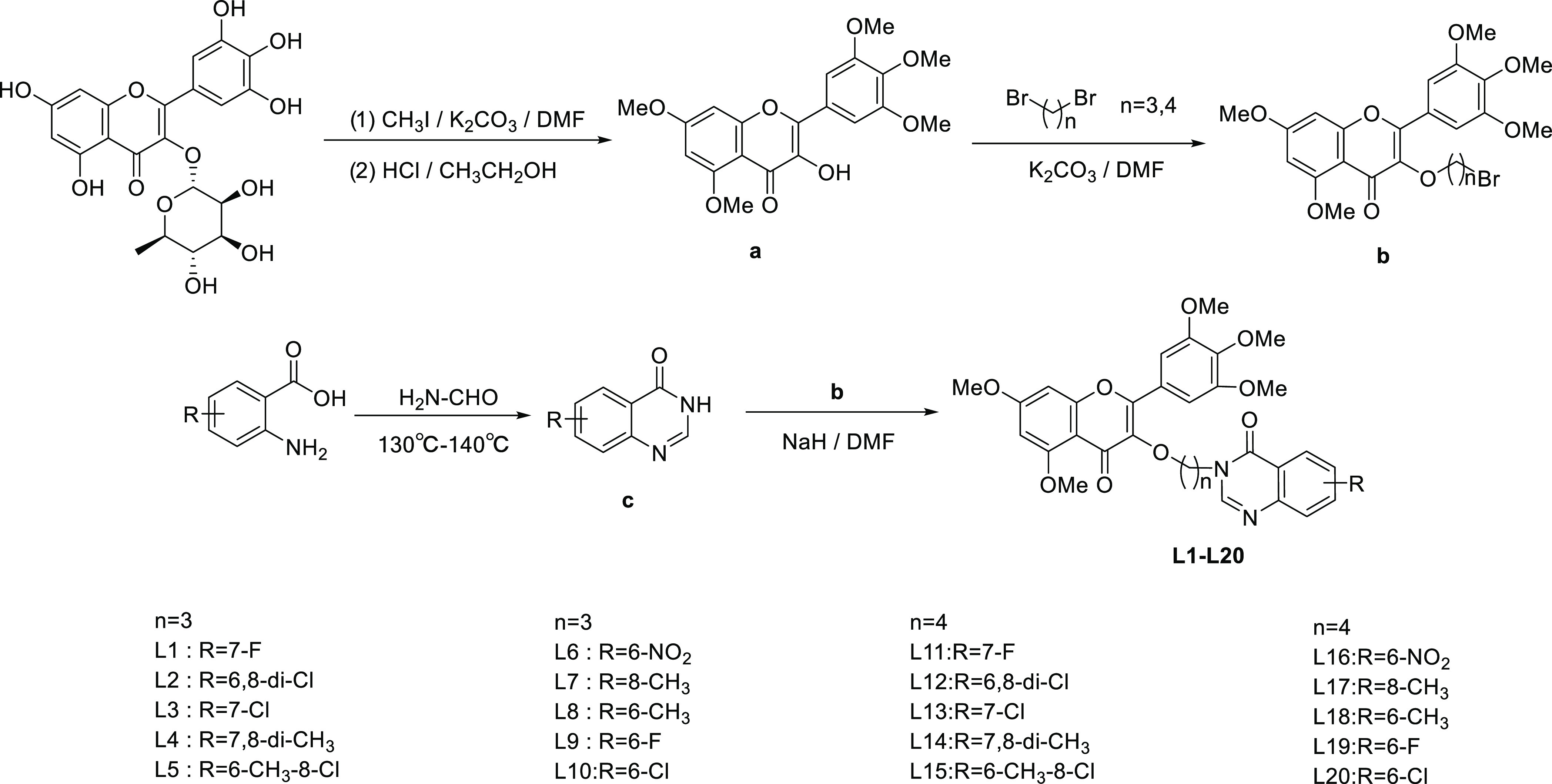

The synthetic routes are shown in Scheme 1; myricetin underwent methylation and deglycosylation steps to obtain intermediate a. Intermediate b was obtained by reacting 1,3-dibromopropane or 1,4-dibromobutane with intermediate a. Intermediate c was obtained by reacting substituted anthranilic acid with formamide at 135 °C for 3–6 h. Intermediates b and c were reacted in N,N-dimethylformamide with NaH at 90 °C for 4–6 h to obtain the target compounds. The structures of L1–L20 were characterized by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), 13C NMR, 19F NMR, and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and the detailed data was included in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route of the Target Compounds L1–L20.

2.2. Antibacterial Activity In Vitro

The antibacterial activity data is shown in Table 1. Some of the target compounds exhibited good antibacterial activities against Xac, Psa, and Xoo. Compounds L11, L13–L15, and L17–L20 exhibited good in vitro antibacterial activities against Xac when concentrations were 100 and 50 μg/mL; the inhibition rates were better than those of BT (60.2 and 44.6%, respectively) and TC (53.6 and 36.8%, respectively). Compounds L11, L14, and L18 displayed good in vitro antibacterial activities against Psa, with inhibition rates being better than those of BT (54.7 and 39.4%, respectively) and TC (49.0 and 33.3%, respectively). Compounds L11, L13, and L18 showed good in vitro antibacterial activities against Xoo, with inhibition rates being better than those of BT (54.0 and 42.9%, respectively) and TC (54.2 and 28.7%, respectively).

Table 1. Antibacterial Activities of the Target Compounds Against Xac, Psa, and Xoo In Vitroa.

|

Xac |

Psa |

Xoo |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd. | 100 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL |

| L1 | 34.9 ± 3.6 | 29.9 ± 3.4 | 28.8 ± 2.3 | 22.8 ± 1.3 | 18.4 ± 1.0 | 12.9 ± 1.7 |

| L2 | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 2.8 | 15.6 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 1.6 | 10.6 ± 2.7 | 8.5 ± 0.9 |

| L3 | 17.5 ± 0.5 | 15.0 ± 1.7 | 24.1 ± 3.0 | 16.5 ± 0.2 | 13.8 ± 2.3 | 8.2 ± 2.1 |

| L4 | 38.1 ± 5.9 | 24.8 ± 2.4 | 22.8 ± 1.8 | 18.2 ± 0.7 | 26.4 ± 0.4 | 13.5 ± 0.7 |

| L5 | 28.8 ± 0.7 | 23.3 ± 2.0 | 30.5 ± 2.2 | 26.0 ± 4.0 | 19.7 ± 3.8 | 7.7 ± 2.3 |

| L6 | 26.9 ± 4.5 | 20.2 ± 0.2 | 13.3 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 2.0 | 16.3 ± 8.3 | 10.4 ± 0.9 |

| L7 | 43.6 ± 0.5 | 28.7 ± 1.1 | 25.9 ± 2.5 | 12.7 ± 2.0 | 26.1 ± 0.5 | 15.9 ± 0.6 |

| L8 | 67.1 ± 4.7 | 35.1 ± 3.1 | 27.8 ± 1.6 | 19.7 ± 4.4 | 29.2 ± 3.6 | 20.3 ± 5.3 |

| L9 | 40.8 ± 5.2 | 24.4 ± 2.3 | 19.5 ± 1.4 | 15.7 ± 1.8 | 25.0 ± 4.8 | 21.7 ± 2.0 |

| L10 | 34.3 ± 2.6 | 22.3 ± 4.3 | 20.9 ± 1.1 | 18.0 ± 1.2 | 19.5 ± 0.6 | 17.9 ± 1.6 |

| L11 | 72.4 ± 1.9 | 56.4 ± 3.2 | 68.8 ± 4.3 | 45.7 ± 2.1 | 69.7 ± 2.6 | 48.2 ± 1.1 |

| L12 | 45.0 ± 3.2 | 25.3 ± 1.7 | 49.1 ± 0.5 | 35.3 ± 1.3 | 41.3 ± 0.3 | 29.6 ± 1.3 |

| L13 | 76.9 ± 1.5 | 58.7 ± 1.4 | 39.3 ± 2.5 | 31.5 ± 2.8 | 68.2 ± 1.3 | 46.2 ± 1.5 |

| L14 | 80.7 ± 2.0 | 62.4 ± 0.5 | 70.1 ± 3.2 | 53.7 ± 1.6 | 47.2 ± 2.7 | 18.1 ± 2.7 |

| L15 | 66.5 ± 4.5 | 45.8 ± 1.6 | 45.2 ± 5.2 | 28.7 ± 3.7 | 22.2 ± 5.6 | 10.3 ± 3.9 |

| L16 | 40.8 ± 1.9 | 17.0 ± 1.3 | 31.6 ± 4.3 | 12.9 ± 3.2 | 27.8 ± 1.0 | 24.0 ± 2.5 |

| L17 | 83.5 ± 3.0 | 71.9 ± 1.4 | 61.0 ± 3.2 | 37.7 ± 2.4 | 55.6 ± 1.0 | 38.8 ± 1.2 |

| L18 | 86.1 ± 2.0 | 72.0 ± 0.7 | 72.4 ± 1.5 | 55.6 ± 4.3 | 83.9 ± 1.7 | 67.5 ± 1.8 |

| L19 | 62.4 ± 3.7 | 44.9 ± 1.2 | 54.4 ± 0.8 | 45.4 ± 1.4 | 30.6 ± 3.0 | 17.6 ± 6.1 |

| L20 | 68.0 ± 2.3 | 48.1 ± 2.1 | 44.7 ± 1.7 | 31.3 ± 4.3 | 38.4 ± 0.9 | 36.2 ± 6.4 |

| myricetinb | 43.5 ± 2.0 | 30.3 ± 0.8 | 35.8 ± 1.8 | 29.1 ± 3.1 | 55.2 ± 1.3 | 37.4 ± 2.2 |

| BTc | 60.2 ± 1.3 | 44.6 ± 1.8 | 54.7 ± 1.7 | 39.4 ± 1.1 | 54.0 ± 1.2 | 42.9 ± 1.1 |

| TCc | 53.6 ± 0.4 | 36.8 ± 1.2 | 49.0 ± 2.1 | 33.3 ± 1.5 | 54.2 ± 0.7 | 38.0 ± 0.8 |

Average of three replicates.

Myricetin was used for comparison of antibacterial activity.

BT (bismerthiazol) and TC (thiodiazole copper).

Based on preliminary bioassay results, the EC50 values of some target compounds were also determined (Table 2). The EC50 values for compounds L11, L13, L14, L17, and L18 against Xac ranged from 16.9 to 27.0 μg/mL. These results were better than those for BT (62.2 μg/mL) and TC (97.5 μg/mL). The EC50 values for compounds L11, L14, and L18 against Psa ranged from 28.1–46.4 μg/mL. These results were better than those for BT (81.0 μg/mL) and TC (128.0 μg/mL). Compounds L11, L13, and L18 have good inhibitory activity against Xoo. The EC50 values of these compounds ranged from 20.4 to 50.4 μg/mL, which were better than those of the control agents BT (63.7 μg/mL) and TC (86.1 μg/mL). The results showed that compound L18 has broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, with EC50 values 17.8, 29.7, and 22.1 μg/mL.

Table 2. EC50 Values of Several Target Compounds Against Xac, Psa, and Xooa.

| bacteria | compd. | n | R | toxic regression equation | r | EC50 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xac | L11 | 4 | 7-F | y = 0.7905x + 3.9084 | 0.9758 | 24.0 ± 3.2 |

| L13 | 4 | 7-Cl | y = 1.1113x + 3.4101 | 0.9860 | 27.0 ± 2.1 | |

| L14 | 4 | 7,8-di-CH3 | y = 1.1729x + 3.4153 | 0.9890 | 22.4 ± 2.0 | |

| L17 | 4 | 8-CH3 | y = 1.2463x + 3.4326 | 0.9901 | 18.1 ± 3.0 | |

| L18 | 4 | 6-CH3 | y = 1.2869x + 3.4183 | 0.9870 | 16.9 ± 2.0 | |

| myricetinb | y = 0.9290x + 2.9584 | 0.9961 | 135.6 ± 2.4 | |||

| BTc | y = 1.0215x + 3.1677 | 0.9945 | 62.2 ± 2.5 | |||

| TCc | y = 1.0219x + 2.9673 | 0.9890 | 97.5 ± 1.4 | |||

| Psa | L11 | 4 | 7-F | y = 1.1149x + 3.1425 | 0.9838 | 46.4 ± 4.3 |

| L14 | 4 | 7,8-di-CH3 | y = 0.9243x + 3.5902 | 0.9870 | 33.5 ± 3.8 | |

| L18 | 4 | 6-CH3 | y = 0.9386x + 3.6400 | 0.9898 | 28.1 ± 4.4 | |

| myricetinb | y = 0.6035x + 3.3908 | 0.9884 | 356.7 ± 3.1 | |||

| BTc | y = 0.9320x + 3.2212 | 0.9934 | 81.0 ± 1.8 | |||

| TCc | y = 0.8254x + 3.2606 | 0.9885 | 128.0 ± 3.8 | |||

| Xoo | L11 | 4 | 7-F | y = 1.0892x + 3.2260 | 0.9844 | 42.5 ± 2.6 |

| L13 | 4 | 7-Cl | y = 1.2187x + 2.9252 | 0.9875 | 50.4 ± 1.7 | |

| L18 | 4 | 6-CH3 | y = 1.3163x + 3.2762 | 0.9943 | 20.4 ± 2.2 | |

| myricetinb | y = 0.7711x + 3.4838 | 0.9741 | 92.5 ± 2.2 | |||

| BTc | y = 0.7396x + 3.6657 | 0.9793 | 63.7 ± 1.4 | |||

| TCc | y = 1.0206x + 3.0250 | 0.9955 | 86.1 ± 3.7 |

Average of three replicates.

Myricetin was used for comparison of antibacterial activity.

BT (bismerthiazol) and TC (thiodiazole copper).

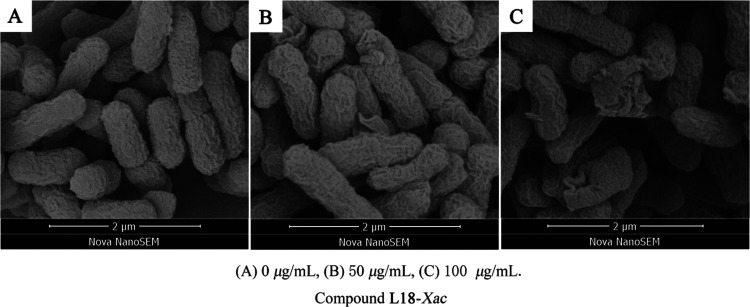

2.3. Morphological Change

The SEM results are shown in Figure 3. When Xac cells were not treated with the compound, the cell morphology was full and uniform; when the compound concentration was 50 μg/mL, the cell surface was pitted; and when the compound concentration was 100 μg/mL, the cell morphology was broken. This result indicated that compound L18 can achieve the purpose of inhibiting the growth of Xac by affecting the morphology of Xac cells.

Figure 3.

Morphological study of Xac treated with compound L18 by SEM.

2.4. Antiviral Activity In Vivo

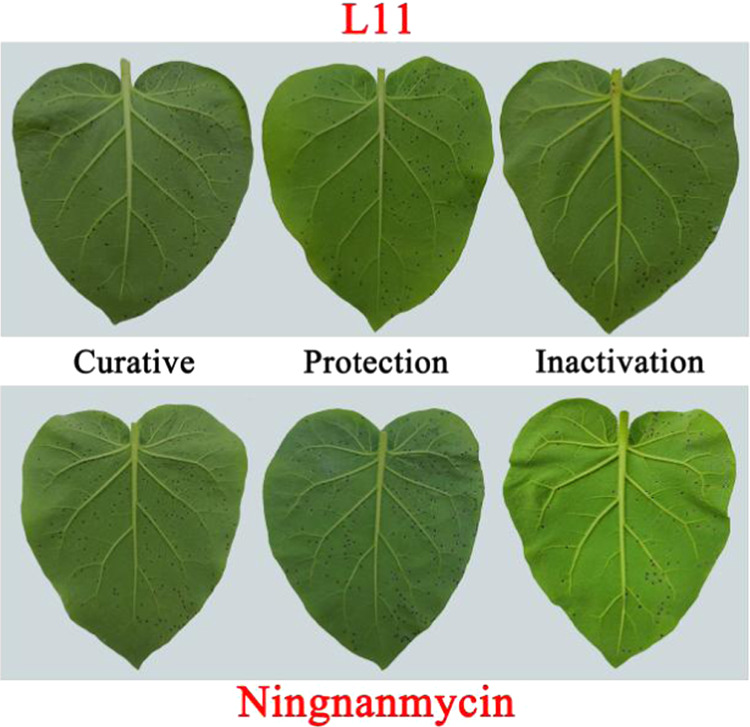

As shown in Table 3, antiviral activity test results showed that the curative, protective, and inactivating activities of L1–L20 for TMV ranged from 20.1 to 63.1%, 12.3 to 68.7%, and 35.1 to 69.8%, respectively. In particular, compound L11 showed 63.1% curative effects at 500 μg/mL, which was better than ningnanmycin (54.1%). In addition, compound L11 exhibited significant protective activity against TMV at 500 μg/mL, and its inhibition rate was 68.7%, which was even better than that of ningnanmycin (57.1%).

Table 3. Antiviral Activities of the Target Compounds Against TMVaIn Vivo at 500 μg/mL.

| compd. | n | R | curative (%) | protection (%) | inactivation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 3 | 7-F | 32.3 ± 4.0 | 38.9 ± 3.6 | 45.7 ± 4.3 |

| L2 | 3 | 6,8-di-Cl | 34.4 ± 4.3 | 36.4 ± 4.7 | 64.7 ± 1.2 |

| L3 | 3 | 7-Cl | 25.5 ± 3.3 | 57.4 ± 4.7 | 69.8 ± 1.6 |

| L4 | 3 | 7,8-di-CH3 | 25.7 ± 4.1 | 45.1 ± 4.7 | 59.1 ± 4.6 |

| L5 | 3 | 6-CH3-8-Cl | 32.0 ± 2.5 | 58.7 ± 3.1 | 58.7 ± 2.1 |

| L6 | 3 | 6-NO2 | 38.6 ± 3.0 | 48.2 ± 3.1 | 37.8 ± 4.1 |

| L7 | 3 | 8-CH3 | 34.5 ± 2.8 | 46.2 ± 2.4 | 58.2 ± 2.2 |

| L8 | 3 | 6-CH3 | 20.1 ± 4.4 | 54.6 ± 4.5 | 55.1 ± 2.5 |

| L9 | 3 | 6-F | 36.7 ± 3.8 | 64.3 ± 2.4 | 35.1 ± 3.2 |

| L10 | 3 | 6-Cl | 42.4 ± 1.4 | 38.4 ± 2.5 | 49.7 ± 4.2 |

| L11 | 4 | 7-F | 63.1 ± 1.0 | 68.7 ± 0.4 | 64.4 ± 2.9 |

| L12 | 4 | 6,8-di-Cl | 34.6 ± 4.7 | 59.7 ± 1.9 | 66.3 ± 2.4 |

| L13 | 4 | 7-Cl | 57.9 ± 3.6 | 37.6 ± 1.8 | 37.3 ± 3.9 |

| L14 | 4 | 7,8-di-CH3 | 25.8 ± 3.7 | 46.9 ± 1.2 | 54.2 ± 3.4 |

| L15 | 4 | 6-CH3-8-Cl | 21.1 ± 4.2 | 39.5 ± 4.3 | 53.6 ± 4.0 |

| L16 | 4 | 6-NO2 | 39.0 ± 3.8 | 31.3 ± 4.9 | 57.5 ± 4.2 |

| L17 | 4 | 8-CH3 | 24.8 ± 3.0 | 12.3 ± 2.1 | 38.9 ± 2.8 |

| L18 | 4 | 6-CH3 | 39.8 ± 3.6 | 49.3 ± 1.2 | 58.3 ± 3.3 |

| L19 | 4 | 6-F | 36.5 ± 2.7 | 38.6 ± 2.3 | 66.8 ± 2.4 |

| L20 | 4 | 6-Cl | 38.4 ± 4.9 | 48.8 ± 2.9 | 38.4 ± 3.0 |

| myricetinb | 36.7 ± 2.6 | 45.6 ± 3.9 | 43.4 ± 2.3 | ||

| ningnanmycinc | 54.1 ± 2.1 | 57.1 ± 1.9 | 85.3 ± 3.8 |

Average of three replicates.

Myricetin was used for comparison of antiviral activity.

Commercial antiviral agent ningnanmycin.

The EC50 value of compound L11 was determined to understand its potential inhibitory ability to TMV. It can be seen from Table 4 that the EC50 values of the curative and protective activities of compound L11 against TMV were 261.0 and 205.8 μg/mL, respectively, which were better than those of ningnanmycin of 319.7 and 341.3 μg/mL, respectively. The tobacco leaf morphology effects of compound L11 and ningnanmycin against tobacco mosaic virus in vivo are shown in Figure 4.

Table 4. EC50 Values of Compound L11 and Ningnanmycin Against TMVa.

| compd. | R | n | regression equation | r | EC50 (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| curative activity | L11 | 7-F | 4 | y = 0.8272x + 3.0010 | 0.9798 | 261.0 ± 2.1 |

| ningnanmycinb | y = 0.6087x + 3.4754 | 0.9990 | 319.7 ± 4.7 | |||

| protection activity | L11 | 7-F | 4 | y = 0.9648x + 2.7679 | 0.9743 | 205.8 ± 4.1 |

| ningnanmycinb | y = 0.9198x + 2.6743 | 0.9810 | 341.3 ± 3.9 |

Average of three replicates.

Commercial antiviral agents ningnanmycin.

Figure 4.

Tobacco leaf morphology effects of compound L11 and ningnanmycin against tobacco mosaic virus in vivo. Left side of each leaf: smeared with the compound; right side of each leaf: not treated with the compound.

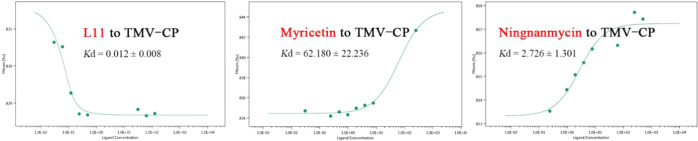

2.5. Binding Affinity Analysis

To further analyze the interactions between compound L11, myricetin, ningnanmycin, and TMV-CP, MST analysis was carried out. The results are shown in Table 5 and Figure 5. The Kd value of compound L11 to TMV-CP was 0.012 ± 0.0.08 μM, which was better than that of the lead compound myricetin (62.180 ± 22.236 μM) and the control agent ningnanmycin (2.726 ± 1.301 μM). It shows that myricetin, the lead compound, can greatly enhance its binding ability with TMV-CP after structural modification.

Table 5. Dissociation Constant of Compound L11, Myricetin, and Ningnanmycin with TMV-CP.

| compd. | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|

| L11 | 0.012 ± 0.008 |

| myricetin | 62.180 ± 22.236 |

| ningnanmycin | 2.726 ± 1.301 |

Figure 5.

MST of compound L11, myricetin, and ningnanmycin.

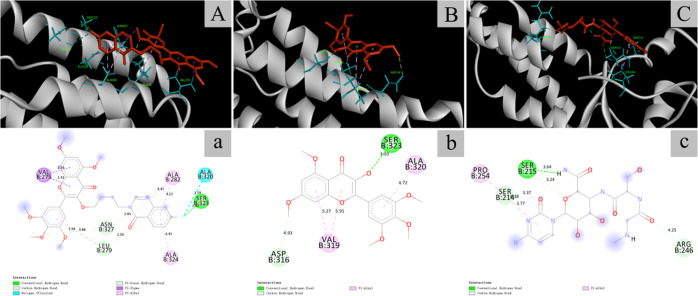

2.6. Molecular Docking

As shown in Figure 6, compound L11 (A, a), myricetin (B, b), and ningnanmycin (C, c) all achieved good docking with the tobacco mosaic virus coat protein. The hydrogen bond length between SER323 and compound L11 was 2.42 Å, which was less than between SER215 and ningnanmycin (3.64 Å). However, the length of the hydrogen bond between SER323 and unmodified myricetin was 3.93 Å. It can be seen that the modified myricetin can significantly enhance the binding force with TMV-CP.

Figure 6.

Binding mode of compound L11 (A, a), myricetin (B, b), and ningnanmycin (C, c) docked with TMV-CP.

2.7. Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR)

According to the antibacterial activity data in Table 1, the results of SAR analysis are as follows. The antibacterial activities of the compounds with 4 methylene groups (n = 4) against three plant pathogens (Xac, Psa, Xoo) were significantly higher than those of the compounds with 3 methylene groups (n = 3).

SAR analysis was performed according to the antiviral activity data in Table 3. When R was 7-F, 7-Cl, 6,8-di-Cl, and 6-F, the antiviral activities of the target compounds were significantly increased. Among them, compound L11 (R = 7-F) had the best curative and protection activities, with the inhibition rates of 63.1 and 68.7%, respectively. It can be known from these data that the target compound showed better antiviral activity when R was an electron-withdrawing group.

3. Conclusions

In summary, a series of myricetin derivatives containing a quinazolinone moiety were designed and synthesized. The antibacterial and antiviral activities of all target compounds were evaluated. The results showed that compound L18 has the best inhibitory activity on Xac, with an EC50 value of 16.9 μg/mL, which was better than those of the control agents BT (62.2 μg/mL) and TC (97.5 μg/mL). Compound L11 has the best protective activity against TMV, with an EC50 value of 205.6 μg/mL, which was better than ningnanmycin (341.3 μg/mL). Preliminary mechanism studies demonstrated that compound L18 inhibited the growth of Xac cells by affecting their morphology. The MST test showed that the Kd value of compound L11 to TMV-CP was 0.012 μM, which was better than ningnanmycin 2.726 μM. The molecular docking results revealed that compound L11 formed a variety of hydrogen bonds with TMV-CP, and its binding force was stronger than ningnanmycin. The above results are consistent with the bioassay results. These research results displayed that myricetin derivatives containing a quinazolinone moiety have the potential to become new and highly effective antibacterial and antiviral agents.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Instruments

All solvents and reagents were purchased from Tianjin Zhi Yuan Regent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China), Shanghai Titan Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and Adamas Reagent, Ltd. (Shanghai, China), which were all of analytical grade and used directly without further purification or drying. The melting point was determined under an X-4B microscope melting point apparatus (Shanghai Yi Dian Physical Optics Instrument Co., Ltd., China). The 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra of the target compounds were obtained on a JEOL-ECX500 MHz (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were procured with a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive (Thermo, Missouri). The interaction between the target compounds and TMV-CP was studied using a micro thermophoresis instrument (NanoTemper Technologies GmbH, Germany). SEM experiments used the Nova NanoSEM 450 (Field Electron and Ion Co.).

4.2. General Synthesis Procedure for Intermediates a and b

Myricetin with a purity of 98% was used as a raw material. Intermediates a and b were synthesized by methods reported in the literature.31

4.3. General Synthesis Procedure for Intermediate c

The substituted anthranilic acid (15 mmol) and formamide (200 mmol) were reacted at 135 °C for 3–6 h (monitored by TLC). Then, intermediate c was obtained by filtration under reduced pressure and drying.

4.4. General Synthesis of Target Compounds L1–L20

Intermediates b (2.75 mmol) and c (3.30 mmol) were reacted in N,N-dimethylformamide (20 mL) with NaH (8.02 mmol) at 90 °C for 4–6 h (monitored by TLC). The reaction mixture was poured into 500 mL of ice water and stirred, and a solid was precipitated out. Then, the crude product was obtained by filtration under reduced pressure. The target compounds were purified by column chromatography with ethyl acetate/methanol (25:1, V/V).

4.5. Antibacterial Activity Assay In Vitro

The method previously reported in the literature was used to determine the antibacterial activity of the target compounds L1–L20.32

4.6. Antiviral Activity Assay In Vivo

The antiviral activity of the target compounds was determined by the method previously reported in the literature.33

4.7. SEM Analysis

The influence of the compound L18 on the morphology of Xac was studied using the previous scanning electron microscopy test method.34

4.8. MST Analysis

The MST test was used to further analyze the interaction between the compounds and TMV-CP. We used Monolith NT.115 software (NanoTemper Technologies, München, Germany) to obtain the Kd value of the compounds for TMV-CP.35

4.9. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking study was obtained using DS-CDoking implemented in Discovery Studio (version 4.5). Compound L11 was selected for docking with TMV-CP (PDB code: 1EI7).36

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 21867003), the Science Foundation of Guizhou Province (No. 20192452), the Natural Science research project of Guizhou Education Department (No. 2018009), the Frontiers Science Center for Asymmetric Synthesis and Medicinal Molecules, Department of Education, Guizhou Province [Qianjiaohe KY number (2020)004], and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities of China (111 Program, D20023).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c05256.

Extraction and purification of TMV; synthetic procedures of target compounds; and characterization data and spectra, including 1H, 13C, 19F NMR, and HRMS (PDF)

Author Contributions

† T.L. and F.P. contributed equally to this work.

Author Contributions

T.L., F.P., and W.X. conceived and designed the study. T.L. completed the experiment and took the required photos. T.L., F.P., and X.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. T.L., F.L., and Q.W. wrote the manuscript. L.L. provided material support. W.X. supervised and funded the acquisition for this work. All authors have read and reviewed the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kashyap P. L.; Kumar S.; Srivastava A. K. Nanodiagnostics for plant pathogens. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 15, 7–13. 10.1007/s10311-016-0580-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva R. N.; Monteiro V. N.; Steindorff A. S.; Gomes E. V.; Noronha E. F.; Ulhoa C. J. Trichoderma/pathogen/plant interaction in pre-harvest food security. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 565–583. 10.1016/j.funbio.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shasmita; Mohapatra D.; Mohapatra P. K.; Naik S. K.; Mukherjee A. K. Priming with salicylic acid induces defense against bacterial blight disease by modulating rice plant photosystem II and antioxidant enzymes activity. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 108, 101427 10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.101427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.; Li X.; Yin L.; Jiang D.; Hu D. Design, synthesis, antiviral bioactivity, and mechanism of the ferulic acid ester-containing sulfonamide moiety. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19721–19726. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Ye Y.; Liu S.; Shao W.; Liu L.; Yang S.; Wu Z. Design, synthesis and anti-TMV activity of novel α-aminophosphonate derivatives containing a chalcone moiety that induce resistance against plant disease and target the TMV coat protein. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 172, 104749 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttimer C.; McAuliffe O.; Ross R. P.; Hill C.; O’Mahony J.; Coffey A. A. Bacteriophages and bacterial plant diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 34 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Shi J.; Chen J.; Hu D.; Zang L.; Song B. Synthesis, antibacterial activity, and mechanisms of novel 6-sulfonyl-1,2,4-triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4] thiadiazole derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4645–4654. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X.; Zhang C.; Chen M.; Xue Y.; Liu T.; Xue W. Synthesis and antiviral activity of novel myricetin derivatives containing ferulic acid amide scaffolds. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 2374–2379. 10.1039/C9NJ05867B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C.; Zhao L.; Sun Z.; Hu D.; Song B. Discovery of novel indole derivatives containing dithioacetal as potential antiviral agents for plants. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2020, 166, 104568 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi M.; Lotfi V.; Saeedi M.; Kianmehr E.; Shafiee A. Synthesis of novel fused quinazolinone derivatives. Mol. Divers. 2016, 20, 677–685. 10.1007/s11030-016-9675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J.; Yin X.; Li H.; Ma K.; Zhang Z.; Zhou R.; Wang Y.; Hu G.; Liu Y. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of quinazolinone derivatives as potential fungicides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4604–4614. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Liu H.; Li W.; Zhang S.; Wu Z.; Li X.; Li C.; Liu Y.; Chen B. Design, synthesis, antiproliferative and antibacterial evaluation of quinazolinone derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 203–214. 10.1007/s00044-018-2276-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed A. A.; Ismail M. F.; Amr A. E. E.; Naglah A. M. Synthesis, Antiproliferative, and Antioxidant Evaluation of 2-pentylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (thione) derivatives with DFT study. Molecules 2019, 24, 3787. 10.3390/molecules24203787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan X.; Xu Y.; Qi Q.; Wang Y.; Shi H.; Mao Z. Synthesis, cytotoxic, and antibacterial evaluation of quinazolinone derivatives with substituted amino moiety. Chem. Biodiversity 2018, 15, e1700513 10.1002/cbdv.201700513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bordany E. A.; Ali R. S. Synthesis of new benzoxazinone, quinazolinone, and pyrazoloquinazolinone derivatives and evaluation of their cytotoxic activity against human breast cancer cells. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2018, 55, 1223–1231. 10.1002/jhet.3158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ran L.; Yang H.; Luo L.; Huang M.; Hu D. Discovery of potent and novel quinazolinone sulfide inhibitors with anti-ToCV activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 5302–5308. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y.; Wang K.; Wang Z.; Liu Y.; Ma D.; Wang Q. Luotonin A and its derivatives as novel antiviral and antiphytopathogenic fungus agents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 8764–8773. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Chen Q.; Li X.; Wu S.; Wan J.; Ouyang G. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of 2-substitued-(3-pyridyl)-quinazolinone derivatives. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2018, 55, 743–749. 10.1002/jhet.3099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Li P.; Li Z.; Yin J.; He M.; Xue W.; Chen Z.; Song B. Synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of novel arylimines containing a 3-aminoethyl-2- [(p-trifluoromethoxy)anilino]-4(3H)-quinazolinone moiety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9575–9582. 10.1021/jf403193q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L.; Gan Y.; Hou M.; Tao S.; Zhang L.; Wang Z.; Ouyang G. Design, synthesis and biological activity of quinazolinone derivatives containing hydrazone structural units. Chinese J. Org. Chem. 2020, 40, 1975. 10.6023/cjoc202003013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.; Tang X.; Chen M.; He J.; Su S.; Liu L.; He M.; Xue W. Design, synthesis and antibacterial activities against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, Xanthomonas axonopodispv. citri and Ralstonia solanacearum of novel myricetin derivatives containing sulfonamide moiety. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 853–860. 10.1002/ps.5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Han X.; Yu P. J.; Chen L. Z.; Xue W.; Liu X. H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of myricetin-pentadienone hybrids as potential anti-inflammatory agents in vitro and in vivo. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 96, 103597 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J.; Lee S. H.; Jung K.; Yoo H.; Park G. Inhibitory effects of myricetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 32. 10.3390/brainsci10010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan T.; Tao Y.; Wang X.; Lv C.; Miao G.; Wang S.; Wang D.; Wang Z. Preparation, characterization and evaluation of the antioxidant capacity and antitumor activity of myricetin microparticles formated by supercritical antisolvent technology. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2021, 175, 105290 10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin R.; Chen Z.; Marin R.; Donati M.; Feltrinelli A.; Montopoli M.; Zambon S.; Manzato E.; Froldi G. Activity of myricetin and other plant-derived polyhydroxyl compounds in human LDL and human vascular endothelial cells against oxidative stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 82, 472–478. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita-Morioka K.; Yamanaka K.; Mizunoe Y.; Tanaka Y.; Ogura T.; Sugimoto S. Inhibitory effects of myricetin derivatives on curli-dependent biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8452 10.1038/s41598-018-26748-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Li P.; Su S.; Chen M.; He J.; Liu L.; He M.; Wang H.; Xue W. Synthesis and antibacterial and antiviral activities of myricetin derivatives containing a 1,2,4-triazole Schiff base. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 23045–23052. 10.1039/C9RA05139B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.; Su S.; Chen M.; Peng F.; Zhou Q.; Liu T.; Liu L.; Xue W. Antibacterial activities of novel dithiocarbamate-containing 4H-chromen-4-one derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 5641–5647. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.; Tang X.; Liu T.; Peng F.; Zhou Q.; Liu L.; He M.; Xue W. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of novel myricetin derivatives containing sulfonylpiperazine. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 1021–1027. 10.1007/s11696-020-01363-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Su S.; Zhou Q.; Tang X.; Liu T.; Peng F.; He M.; Luo H.; Xue W. Antibacterial and antiviral activities and action mechanism of flavonoid derivatives with a benzimidazole moiety. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101194 10.1016/j.jscs.2020.101194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W.; Song B.; Zhao H. J.; Qi X. B.; Huang Y. J.; Liu X. H. Novel myricetin derivatives: Design, synthesis and anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 155–163. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X.; Li P.; Li M.; Yang A.; Yu L.; Luo L.; Hu D.; Song B. Synthesis and investigation of the antibacterial activity and action mechanism of 1,3,4-oxadiazole thioether derivatives. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 147, 11–19. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; He F.; Chen J.; Wang Y.; Yang Y.; Hu D.; Song B. Purine nucleoside derivatives containing a sulfa ethylamine moiety: design, synthesis, antiviral activity, and mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 5575–5582. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T.; Xia R.; Liu T.; Peng F.; Tang X.; Zhou Q.; Luo H.; Xue W. Synthesis, biological activity and action mechanism study of novel chalcone derivatives containing malonate. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000025 10.1002/cbdv.202000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; He F.; Wu S.; Luo Y.; Wu R.; Hu D.; Song B. Design, synthesis, anti-TMV activity, and preliminary mechanism of cinnamic acid derivatives containing dithioacetal moiety. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 164, 115–121. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng F.; Liu T.; Wang Q.; Liu F.; Cao X.; Yang J.; Liu L.; Xie C.; Xue W. Antibacterial and antiviral activities of 1,3,4-oxadiazole thioether 4H -chromen-4-one derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11085–11094. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.