Abstract

Objective:

To determine the contribution of normal physiological changes to the overall manifestation of a relapse after orthodontic treatment. We analyzed long-term changes in the dentition of patients with Class I malocclusions after orthodontic treatment compared with a representative group with untreated Class I malocclusions.

Materials and Methods:

Study participants (n = 66; mean age, 12 years at treatment initiation) were treated for Class I malocclusions. Dental changes were evaluated at 2, 5, 10, and 15 years after treatment. Control participants (n = 79) had untreated Class I malocclusions (n = 53 evaluated at ages 12 and 22 years; n = 26 evaluated at ages 19 and 39 years). Dental changes were evaluated with the Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) index.

Results:

In untreated and treated groups, PAR scores increased over time with gender-specific changes. In the untreated groups, the PAR score significantly increased in male participants between the ages of 12 and 22 years (P = .04) and in female participants between the ages of 19 and 39 years (P = .001). In the treated group, early posttreatment changes were primarily related to the initial treatment response. Later changes in the PAR score could be attributed to physiological changes, with the same gender-specific changes as those observed in the untreated group.

Conclusions:

The pattern of physiological changes in dentition for participants between the ages of 12 and 39 was different between sexes. Females showed more relapse than males between 10 and 15 years posttreatment. This distinction should be considered when evaluating long-term orthodontic treatment responses.

Keywords: Treatment stability, Relapse, Dentoalveolar change, PAR index

INTRODUCTION

The public is becoming increasingly aware of facial aesthetics. As a result, more adults seek orthodontic treatment. The benefits of treatment need to be weighed against the risks, and potential changes after an orthodontic treatment, including relapse, should be taken into consideration. At present, it is not possible to make an evidence-based recommendation because we have limited knowledge about many of the variables concerned. In addition, our knowledge of treatment stability is limited to the first 20 years posttreatment.1–3

Only a few scientifically sound studies have been published on the dental and skeletal changes observed in treated and untreated individuals.4–7 Many studies pool different types of malocclusions, lack an untreated control group, or compare treated and untreated individuals that are not age matched.8–10 However, it is of great value to study untreated individuals to determine the natural changes that occur in the dentition and face. This information can be used in individuals who receive orthodontic treatment to differentiate between physiological changes that are inherent to aging and changes related to a previous orthodontic treatment.

The aims of this prospective cohort study were twofold. First, we aimed to analyze dentoalveolar changes that occurred after orthodontic treatment in patients with a Class I malocclusion up to 15 years after removal of a retention appliance. Second, we aimed to relate these changes to the physiological dentoalveolar changes observed in untreated individuals with Class I malocclusions between the ages of 12 and 39 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The data for the untreated control group were derived from participants in the Nijmegen Growth Study conducted in 1970–197511 and from former students of a university in Nijmegen who were freshmen in different faculties between 1966 and 1967. These records had been collected for other research purposes.

From the Nijmegen Growth Study, two cohorts were recalled in 1983 and in 1985, when participants were 22 years old. Among the former freshmen students, two cohorts were reinvited to participate in 1987, when they were 39 years old.12 Only data for individuals with untreated Class I malocclusions were examined further. Other exclusion criteria were medical conditions that influenced skeletal growth and previous orthodontic treatment with fixed or removable appliances. Two datasets of untreated Class I malocclusions (n = 79) were compiled. The first dataset comprised 26 males and 27 females who were evaluated at 12 years of age and again at 22 years of age (group 1). The second dataset comprised 13 males and 13 females who were evaluated at 19 years of age and again at 39 years of age (group 2).

The treated group was derived from a third dataset, the Nijmegen Treatment Outcome Archive. These patients had Class I malocclusions (n = 66) that were treated by either extracting four premolars (group 3) or by inserting appliances without any tooth extractions (group 4). At the start of treatment, group 3 (n = 31) comprised 14 males aged 11.7 years (standard deviation [SD] 1.5 years) and 17 females aged 11.9 years (SD 1.4 years). Group 4 (n = 35) comprised 14 males aged 11.7 years (SD 1.1 years) and 21 females aged 11.6 years (SD 1.5 years). The treatment protocol for all patients was standard full edgewise fixed appliances, .018 slot. No additional growth modification methods were used before or during treatment. Retention consisted of a fixed canine-to-canine bar in the lower arch and a removable plate-appliance in the upper arch. All patients received either one or both of these two retention appliances. All forms of retention ceased at 1 year after the end of active treatment. Dental casts of all patients were available at the end of the retention phase (postretention) and at intervals of 2, 5, 10, and 15 years postretention. At postretention, the mean ages of male and female patients who received extraction therapy were 15.1 years (SD 1.3 years) and 15.5 years (SD 0.9 years), respectively, and the mean ages of those with nonextraction therapy were 15.4 years (SD 0.9 years) and 14.9 years (SD 1.0 years), respectively.

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals; all agreed that their data could be used for research purposes. For the current study, 554 sets of dental casts were analyzed for both the treated and untreated groups.

Dental Analysis

The Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) index was used to evaluate dental and occlusal changes. This index considers the scores of seven individual traits measured on study dental casts, including alignments of the (1) upper and (2) lower anterior segments, (3) right and (4) left buccal occlusions, (5) overjet, (6) overbite, and (7) centerline. These individual traits were weighted according to Richmond et al.,13 and the sum of the scores comprised the weighted PAR score (referred to as the PAR score in this paper). A PAR score of zero indicated perfect alignment and occlusion; higher scores indicated increasing levels of irregularity or malocclusion.14 The posttreatment change in the PAR reflects the degree of improvement and the level of success of the orthodontic treatment. In the untreated groups, PAR indexes were measured for individuals at ages 12 and 22 years (group 1) and for individuals at ages 19 and 39 (group 2). In the treated group, the PAR index was measured at the start of treatment, immediately after the retention phase, and at 2, 5, 10, and 15 years postretention.

Statistical Analysis

Means and standard deviations of the PAR scores were calculated for each age group. Comparisons of the PAR changes between group 1 (12 and 22 years) and group 2 (19 and 39 years) were analyzed with a twosample Student’s t-test. Differences between males at 12 and 22 years and females at 19 and 39 years were analyzed with a one-sample Student’s t-test.

For comparisons between changes that occurred during different time intervals, the statistical analysis included a paired Student t-test and a multiple regression analysis. In the multiple regression analysis, the dependent variable was the PAR change and the independent variables were gender, extraction vs nonextraction, and treatment effect (ie, postretention PAR vs pretreatment PAR).

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software version 10 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y.). The level of significance was set to P < .05.

RESULTS

Dental Analysis

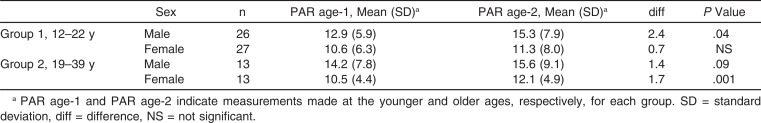

Table 1 shows the PAR scores for the untreated groups at different ages. Both groups showed a significant increase in the PAR score with age. We also found a significant difference between males and females in both groups. In group 1, males (not females) between 12 and 22 years of age showed a significant increase in PAR scores (P = .04). On the other hand, in group 2, females (but not males) between 19 and 39 years of age showed a significant increase in PAR scores (P = .001).

Table 1.

Changes in the Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) Scores for Two Untreated Age Groups

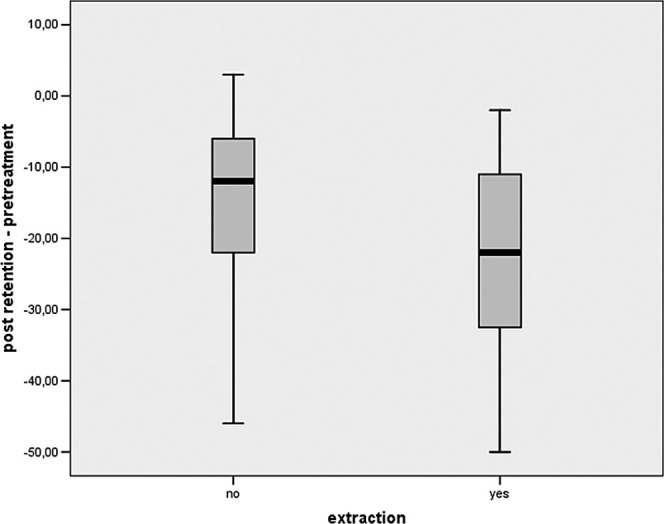

In the treated groups, the pretreatment PAR scores were reduced after retention was removed (Table 2). In group 3 (the extraction group), the mean PAR was reduced by 22.3 points. Among males, the reduction was 17.8 points (SD 8.6 points) and among females the reduction was 26.0 points (SD 9.2 points). In group 4 (the nonextraction group), the mean PAR was reduced by 15.1 points. Among males, the mean PAR score was reduced by 18.9 points (SD 8.8 points), and among females the reduction was 12.5 points (SD 8.0 points). The PAR reductions were significantly different between the extraction and non-extraction groups (P = .02). The distribution of PAR reductions within groups and the differences between the treated groups are shown in box plots (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) Scores Measured at Different Times for Groups 3 (Treated With Tooth Extractions) and 4 (Treated Without Tooth Extractions)

Figure 1.

Box plots of Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) score reductions from pretreatment to postretention. Patients were treated with tooth extractions (yes) or without tooth extraction (no).

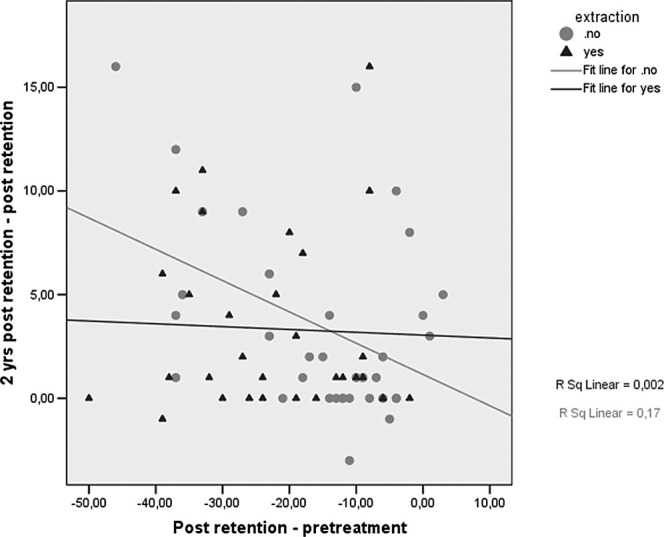

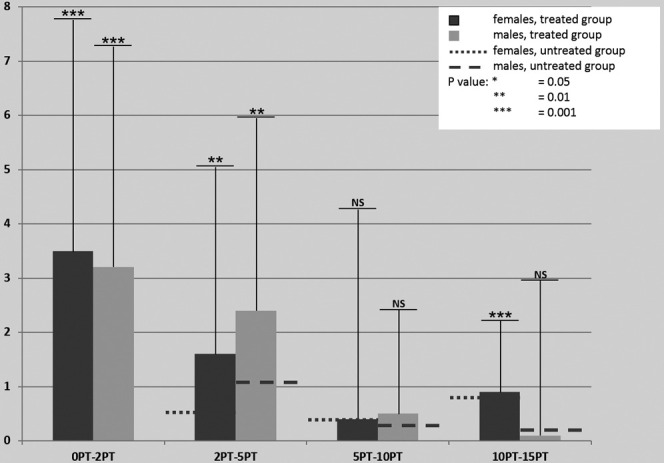

Next, we examined the development of the PAR index at different times after treatment. We found that, at 2 years postretention, the PAR scores significantly increased by 3.2 points (SD 4.35 points; P = .001) for males and by 3.5 points (SD 4.5 points; P = .001) for females. We then performed a regression analysis corrected for gender, extraction vs nonextraction treatments, and PAR scores measured at postretention. This analysis showed that the increase in the PAR score was significantly dependent (P = .034) on the initial treatment effect (ie, PAR postretention–PAR pretreatment; Figure 2). We found that, between 2 and 5 years postretention, the PAR scores significantly increased again, by 2.4 points (SD 3.6 points; P = .002) for males and by 1.6 points (SD 3.5 points; P = .009) for females. Regression analyses revealed that, in the nonextraction group, this increase was again significantly dependent on the initial treatment effect (P = .04), but it also depended on the increase in PAR during the previous 2 years (P = .02).

Figure 2.

Relationships between change in Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) at 2 years postretention and the initial treatment response. Each symbol represents a single patient; red circles indicate treatment without tooth extraction (no); blue triangles indicate treatment with tooth extraction (yes).

Between 5 and 10 years postretention, we found that the PAR scores increased further (but not significantly), by 0.5 points (SD 2.6 points; NS) for males and by 0.4 points (SD 4.3 points; NS) for females. Finally, between 10 and 15 years postretention, the PAR change was gender dependent. A small, insignificant increase in PAR scores was observed for males (0.1 [2.0] points; NS), but a significant increase of 0.9 (SD 1.4 points; P = .007) was observed for females. The proportion of posttreatment changes in PAR scores that could be attributed to age-related physiological adaptations is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Proportion of posttreatment (PT) changes (y axis) in PAR scores that could be attributed to age-related physiological changes. Treated patients are shown in blue (females) and yellow (males); untreated patients are shown in red dotted lines (females) and red dashed lines (males). Each group represents the interval (years PT) between two time points indicated; for example, 2PT–5PT signifies the interval between 2 and 5 years PT.

DISCUSSION

Dentoalveolar changes were evaluated at different ages in each group to cover the second through fourth decades of life. In the untreated group, the PAR scores increased in both age cohorts, with remarkable genderspecific changes. In males, the PAR score rapidly increased during adolescence and then stabilized after the age of 22 years. In females, the PAR score gradually increased during adolescence and then accelerated in the second and third decades of life.

Our results were partly consistent with a study by Akgül et al.,8 who investigated craniofacial and dental changes in the third decade of life in 30 untreated individuals. In that study, an increase in the overbite was significant only in women, and a decrease in mandibular arch length discrepancy was significant only in men. The significant overbite increase in women could be correlated to the slight continuous eruption of teeth that takes place even after the occlusion has been established. Our dental gender-specific differences were confirmed by Bishara et al.15 and Sinclair et al.16 They estimated that, among untreated individuals, the total increase in tooth size–arch length discrepancy between early adolescence and middle adulthood was greater in females than in males. When extrapolated to the individual treated orthodontically, Bishara et al. concluded that an increase in crowding was part of the normal maturation process, regardless of the initial malocclusion or how well these cases were treated.15 Sinclair et al. concluded that maturational changes in the permanent dentition, in general, seemed to be similar in treated and untreated individuals, but the extent of change was significantly less in untreated than in treated individuals, postretention.16 Tsiopas et al.17 also concluded that dentoalveolar processes continue to undergo physiological changes throughout adult life. Of particular clinical relevance, they found that decreases in arch length and depth resulted in a decrease in the intercanine width and increased crowding of the anterior teeth. However, in contrast to the results from our study, they found no differences between male and female participants. Whether normal maturational changes are clinically significant and justify permanent retention depends largely on current opinion and patient-related factors. In an era when patients are becoming more demanding and aesthetics is sometimes correlated with success in life, current practitioners feel compelled to apply permanent retention.

We recorded a significant difference in PAR score reductions between groups treated with extraction and nonextraction therapies. The mean treatment response of the extraction group was larger than that of the nonextraction group. However, in our study the mean pretreatment PAR of the extraction group was larger than that of the nonextraction group. Therefore, we performed a multiple regression analysis to account for the pretreatment differences. We concluded that the extraction group received a superior level of treatment than the nonextraction group. In the nonextraction group, at 2 years postretention, 17% of the posttreatment change in PAR score could be explained by the initial treatment response; in contrast, the initial treatment response explained only 0.2% of the posttreatment PAR change observed in the extraction group (Figure 2). A previous study by Holman et al.18 showed a comparison of PAR changes from pre- to posttreatment between participants who received extraction or nonextraction treatments. They concluded that both groups were statistically identical. Those results cannot be directly compared to our findings because in the Holman study, the dataset included a variety of angle classifications and malocclusions and our datasets included only Class I malocclusions.

In considering the postretention PAR evolution observed in the present study, the largest increase in PAR occurred during the first 2 years postretention. In this time period there was a significant influence of treatment effect on the PAR change (P = .034). This influence was also significant for the 2- to 5-year postretention period (P = .04). This finding was consistent with those from a study by Birkeland19; they found that the change in the mean PAR score during the 5-year follow-up period was correlated to the change in PAR during the treatment period. In the present study, we investigated the postretention evolution of PAR by measuring it at several time periods; therefore we demonstrated that the PAR increase in the 2- to 5-year postretention period was also dependent on the amount of increase observed during the first 2 years postretention (P = .02). In addition, we found that, beyond 5 years postretention, the increase in PAR could be attributed to physiological changes because during this time span, the increase in PAR was equal to that observed in untreated individuals. Moreover, between 10 and 15 years postretention, there was a statistically significant increase in PAR among female patients (P = .007). When we extrapolated the normal physiological changes observed in the untreated group to the changes observed in treated group, the postretention changes could be fully attributed to the significant physiological changes expected in females during this age range. In contrast, Ormiston et al.20 found that the male sex and a sustained period of growth were both associated with increased instability. The discrepancy between those results and our results could be explained by differences in the follow-up periods used in the two studies. In our study, the mean PAR showed a statistically significant increase in female participants between 10 and 15 years postretention; however, in the Ormiston study, the posttreatment follow-up period ranged from 7.4 to 23.3 years. Thus, the discrepancy in results supported the notion that every age category and gender have specific stability properties.

Based on our conclusions, the long-term follow-up, and comparisons of the two distinct groups, one could state that a limited retention period is sufficient. Changes in dentition can no longer be traced back to the previous orthodontic tooth movement 5 years postretention. Unwanted tooth movement, either related to previous orthodontic treatment or physiological changes, is a major concern for our patients, therefore it is expected that the orthodontist will prevent this. Hence, currently in many orthodontic practices a protocol with permanent retention is used. However, it is known that even permanent retention cannot completely prevent unwanted tooth movement as a result of continuing physiological changes.

CONCLUSIONS

Gender-specific changes were observed in the evolution of PAR scores of untreated individuals. PAR scores significantly increased between the ages of 12 and 22 years in males and between the ages of 19 and 39 years in females.

After orthodontic treatment, postretention PAR scores increased, first as a consequence of the initial treatment response. Later, beyond 5 years postretention, the evolution of the PAR score could be attributed to physiological changes, with the same gender-specific changes as those observed in the untreated group.

The different patterns of physiological changes in dentition observed between the sexes from ages 12 to 39 years should be considered when evaluating long-term orthodontic treatment responses. This difference may explain the greater tendency for relapse in females when compared with males at 10 to 15 years postretention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behrents RG. Growth in the Aging Craniofacial Skeleton. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Center for Human Growth and Development; 1985. Monograph 17.Craniofacial Growth Series. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Driscoll-Gilliland J, Bushang PH, Behrents RG. An evaluation of growth and stability in treated and untreated subjects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:588–597. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.118778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaden JL, Harris EF, Zeigler Gardner RL. Relapse revisited. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:543–553. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haruki T, Little RM. Early versus late treatment of crowded first premolar extraction cases: post retention evaluation of stability and relapse. Angle Orthod. 1998;68:61–68. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0061:EVLTOC>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Årtun J, Garol JD, Little RM. Long-term stability of mandibular incisors following successful treatment of Class II, Division 1, malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 1996;66:229–238. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1996)066<0229:LTSOMI>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Yami EA. Orthodontics Treatment Need and Treatment Outcome. Nijmegen, The Netherlands: University of Nijmegen; 2002. [PhD thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boley JC, Mark JA, Sachdeva RCL, Buschang PH. Long-term stability of Class I premolar extraction treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2003;124:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akgül AA, Toygar TU. Natural craniofacial changes in the third decade of life: a longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2002;122:512–522. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.128861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pecora NG, Baccetti T, McNamara JA., Jr The aging craniofacial complex: a longitudinal cephalomteric study from late adolescence to late adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2008;134:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah AA. Postretention changes in mandibular crowding: a review of the literature. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2003;124:298–308. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prahl-Andersen B, Kowalski CJ, Heyendael P. A Mixed Longitudinal Interdisciplinary Study of Growth and Development. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schols JGJH, van der Linden FPGM. Alterations in the dentition relating to facial growth during adolescence. Inf Aus Orthodontie und Kieferorthopädie. 1988;20:95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richmond S, Shaw WC, O’Brien KD, et al. The development of the PAR index (Peer Assessment Rating): reliability and validity. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:125–139. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richmond S, Shaw WC, Roberts CT, Andrews M. The PAR index (Peer Assessment Rating): methods to determine outcome of orthodontic treatment in terms of improvement and standards. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:180–187. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.3.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishara SE, Treder JE, Damon P, Olsem M. Changes in the dental arches and dentition between 25 and 45 years of age. Angle Orthod. 1996;66:417–422. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1996)066<0417:CITDAA>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinclair PM, Little RM. Maturation of untreated normal occlusions. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1983;83:114–123. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(83)90296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsiopas N, Nilner M, Bondemark L, Bjerklin A 40 year follow-up of dental arch dimensions and incisor irregularity in adults. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35:230–235. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holman KJ, Hans MG, Nelson S, Powers MP. An assessment of extraction versus nonextraction orthodontic treatment using the peer assessment rating (PAR) index. Angle Orthod. 1998;68:527–534. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0527:AAOEVN>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkeland K, Furevik J, Bøe OE, Wisth PJ. Evaluation of treatment and post-treatment changes by the PAR Index. Eur J Orthod. 1997;19:279–288. doi: 10.1093/ejo/19.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ormiston JP, Huang GJ, Little RM, Decker JD, Seuk GD. Retrospective analysis of long term stable and unstable orthodontic treatment outcomes. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2005;128:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]