Abstract

Objective:

To describe an orthodontic treatment that combines an esthetic approach (clear aligners) with surgery (alveolar corticotomy).

Materials and Methods:

A patient with moderate dental crowding and Class I skeletal and molar relationships was selected. Orthodontic records of the patient were taken. Periodontal indexes, oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL), and treatment time were evaluated. After we reflected a full-thickness flap beyond the teeth apices, the cortical bone was exposed on the buccal aspect and a modified corticotomy procedure was performed. Interproximal corticotomy cuts were extended through the entire thickness of the cortical layer, just barely penetrating into medullary bone. Orthodontic force was applied on the teeth immediately after surgery.

Results:

Total treatment time was 2 months. Periodontal indexes were improved after correction of crowding. A deterioration of OHRQoL was limited to 3 days following surgery.

Conclusion:

This case report may encourage the use, limited to selected cases, of corticotomy associated with clear aligners to treat moderate crowding.

Keywords: Orthodontic appliances; Tooth movement; Corticotomy; CAD/CAM; Clear aligner therapy, OHRQoL

INTRODUCTION

Esthetic orthodontic treatment with removable, clear, semi-elastic polyurethane aligners has become an increasingly common treatment choice since its first appearance in 1997.1 This computer-aided modeling technique facilitates the fabrication of numerous aligners to move teeth with relative precision to obtain a good occlusion. These aligners are made from a thin, transparent plastic that fits over the buccal, lingual/palatal, and occlusal surfaces of the teeth. Aligners are worn for a minimum of 22 hours per day and changed sequentially every 20 days, and they can be used in adults and adolescents who have fully erupted permanent dentitions.1,2 Removable clear aligners have become a popular treatment choice for clinicians because of their esthetics, comfort, and better oral hygiene compared with traditional appliances, although their use is limited to selected cases. Nowadays, in addition to the esthetic demands, patients require a reduced orthodontic treatment time. A recent systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of interventions on accelerating orthodontic tooth movement suggested that corticotomy is a relatively safe and effective means of doing so.3 It has been suggested that the biologic basis of corticotomy-assisted orthodontic treatment is mediated by a regional acceleratory phenomenon (RAP).4–9 Further, it has been hypothesized that corticotomy can lead to intensified osteoclastic activity, resulting in osteopenia and increased bone remodeling.9 The consequent accelerated tooth movement should shorten treatment duration.

We describe the combined use of alveolar corticotomy to reduce the treatment time and esthetic clear aligners to solve a moderate crowding of both arches. This technique was previously described by Owen in 2001.10

CASE REPORT

Pretreatment Evaluation

A healthy, 12-year-old girl was referred to the Department of Orthodontics of “Sapienza” University of Rome to evaluate the possibility of a short and esthetic orthodontic treatment for dental crowding. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. Extraoral examination revealed good facial proportions with a straight profile, competent lips, and smile line deflected slightly to the right (Figure 1). Temporomandibular joints were healthy. Dental analysis revealed a Class I molar and canine relationship with an overjet of 4 mm and an overbite of 4 mm (Figures 2 and 3); a total Bolton ratio of 93% and an anterior Bolton ratio of 80% were measured. The maxillary midline was centered with the facial midline, and the mandibular midline was deviated 1.5 mm to the right of the maxillary midline (Figure 1). The patient showed a moderate crowding of both arches (maxilla, 5 mm; mandible, 6 mm) with a constricted maxilla (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Pretreatment extraoral photographs.

Figure 2.

Pretreatment intraoral photographs.

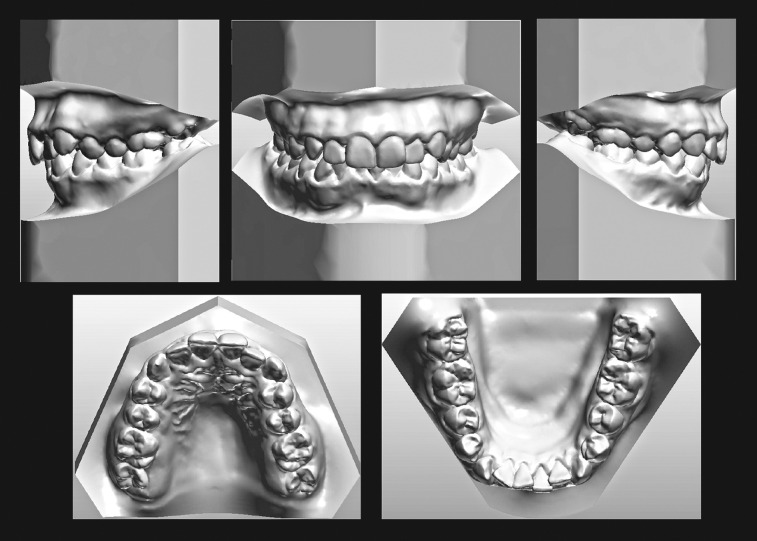

Figure 3.

Pretreatment virtual 3-D models.

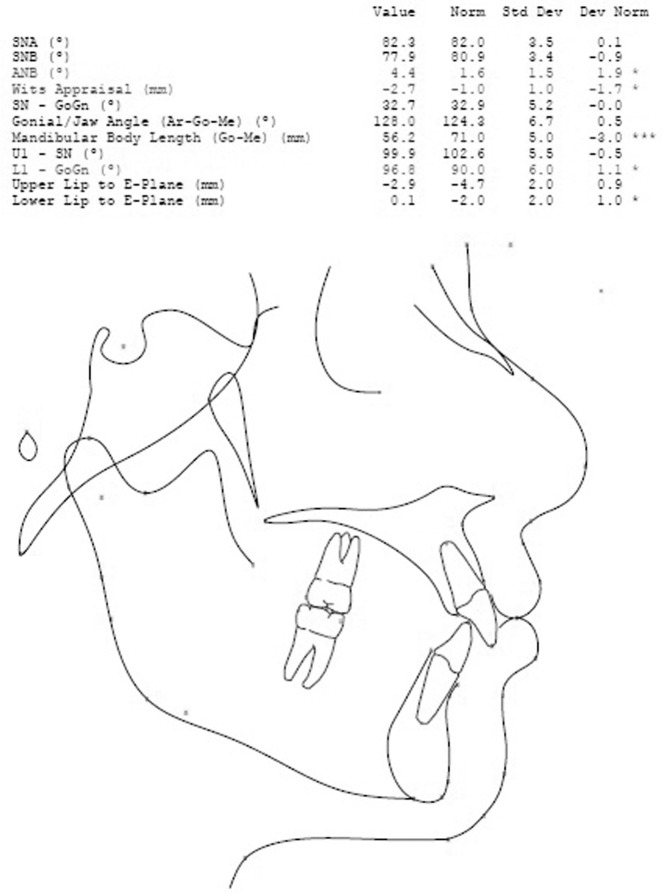

Cephalometric measurements were performed using lateral cephalometric radiography and a digital conventional cephalometric analysis (Oris Ceph, Elite Computer, Vimodrone, Milano, Italy) that showed a Class I skeletal relationship as shown in Figure 4. The panoramic radiograph showed the absence of dental caries, root resorption, dental abnormalities, and any traumatic or pathologic lesions of the alveolar crests (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Lateral cephalometric analysis.

Figure 5.

Pretreatment panoramic radiograph.

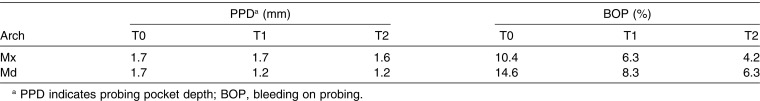

The patient was periodontally healthy. Bleeding on probing (BOP) and probing pocket depth (PPD) were evaluated using a UNC 15 probe. The BOP and PPD were measured with a standardized force probe (about 0.25 N) at the mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal, distolingual, midlingual, and mesiolingual aspects in both arches from left first molar to right first molar. The measurements were taken in each jaw before oral surgery (T0), at 1 month (T1), and at the end of treatment (T2). Each measurement was repeated twice by the same operator and the values averaged.

Oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL) was assessed using the Italian version of the short-form oral health impact profile with 14 questions (OHIP-14), which represents seven dimensions of OHRQoL: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap.11 The OHIP-14 contains questions that retain the original conceptual dimensions contained in the OHIP, and it is useful for quantifying levels of impact on well-being in settings wherein only a limited number of questions can be administered. The patients received the questionnaire after being instructed in its use. In the ward, the self-administered questionnaire was filled out by the patients preoperatively (baseline; T0), 3 days postsurgery (T1), and 7 days postsurgery (T2). Responses were made on an ordinal, 5-point, adjectival scale (0 = never, 1 = hardly ever, 2 = occasionally, 3 = fairly often, 4 = very often). OHRQoL is characterized by summary scores of the OHIP-14 items. Higher scores indicate a stronger negative influence on OHRQoL.

Treatment Plan

The treatment objectives were to

reduce treatment time,

eliminate crowding,

establish a proper overjet and overbite,

establish harmonious functional occlusion.

Treatment Alternatives

Three treatment options to solve the crowding were presented:

Orthodontic treatment with conventional brackets. This option was declined because the patient wanted a more esthetic appliance. Furthermore, she required a short treatment time.

Lingual brackets. Since lingual appliances tend to cause difficulties with oral hygiene, proper speech, and poor accessibility from the lingual side, this alternative was also excluded.

An esthetic treatment plan using clear aligners combined with selective alveolar corticotomies to reduce treatment time.

The patient showed a genuine interest in having treatment completed as soon as possible. The estimated time of treatment using fixed appliances or clear aligners was 6–8 months. Using corticotomy, we assumed a reduction to one-third the time of conventional treatment. The patient, informed of the risks, advantages, and disadvantages of all therapeutic approaches, decided for the combined use of corticotomy and clear aligners. The legal guardians gave their written informed consent for the procedures.

The treatment plan involved comprehensive orthodontic treatment with clear appliances to decrowd and align the teeth and corticotomy in both arches to accelerate tooth movement.

Treatment Progress

Surgical procedure

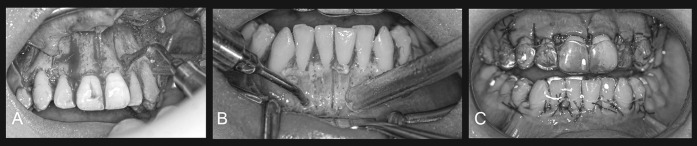

A modified corticotomy was performed in both jaws at the same time. The patient used a mouthwash containing 0.2% chlorhexidine for 1 minute preoperatively. Next, local anesthesia was obtained using carbocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:100,000. A sulcular incision was made and a full-thickness flap was reflected only on the buccal aspect of the maxillary and mandibular teeth, from the medial margin of the right first premolar to the medial margin of the left first premolar with releasing incisions. Flaps were carefully reflected beyond the tooth apices, the cortical bone was exposed, and the osteotomies were performed. Interproximal corticotomy cuts were extended through the entire thickness of the cortical layer, just barely penetrating into medullary bone. The design of the selective decortication (vertical cuts or perforations) was finalized to maximize the marrow penetration and bleeding instead of creating blocks of bone. Vertical cuts were made on both mesial and distal interproximal areas starting 2 to 3 mm apical to the alveolar crest and extending 2 to 3 mm past the estimated root apices, intersecting only the buccal aspect of jaws. Several small, round perforations equivalent to the insert diameter were also made inside the areas circumscribed by those cuts to increase healing stimulus (Figure 6). The vertical cuts were performed from the mesial of the right premolar to the mesial of left premolar with a piezosurgical device (Easy Surgery, BioSAF, Assago, Milan, Italy), using insert 511 to accomplish the vertical cuts and 514 to realize the corticotomy perforations. The procedure was then completed by repositioning the flap and suturing with Vicryl 3.0 thread (Vicryl Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ).

Figure 6.

Modified alveolar corticotomy. Vertical cuts (A) and small round perforations (B) are made using piezosurgical device following only mucoperiosteal buccal flap. The clear aligner applied on the teeth immediately after surgery (C).

The patient completed a specific postoperative protocol, which included antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 1 g in two daily doses for 5 days (Augmentin; Glaxo-SmithKline, Verona, Italy). Oral Coefferalgan (paracetamol 500 mg with codeine 30 mg; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sermoneta, Italy) was given immediately after the corticotomy and prescribed to be taken as required for pain relief (maximum, 6 tabs/d). The patient was instructed not to take any drugs other than those prescribed and to take the analgesic tablet as soon as the pain reached a moderate level. The usual postoperative instructions were given to the patient. The day after surgery, the patient began using the chlorhexidine (15 ml of 0.2% chlorhexidine solution) twice a day for 1 week (Dentosan; Pfizer Consumer Healthcare, Rome, Italy). The sutures were removed at the first follow-up visit 7 days postsurgery.

Orthodontic procedure

Orthodontic force was applied immediately after surgery (Figure 6), using aligners previously fabricated as follows: Polyvinyl siloxane (PVS) impressions of both arches were taken and sent to the manufacturer, who created 18 clear aligners—8 maxillary and 10 mandibular (Smiletech–Ortodontica Italia, Rome, Italy). The mandibular teeth were reduced interproximally by means of diamond-coated finishing strips (1.35 mm of total reduction). This reduction was carried out twice during treatment, depending on the degree of access to the interproximal areas. Each aligner was used for 5 days. After completion of treatment, the patient used 0.6 mm- thick, thermoformed templates as retainers. The patient was instructed to wear them full time for 1 year, followed by night-time wear for an indefinite period.

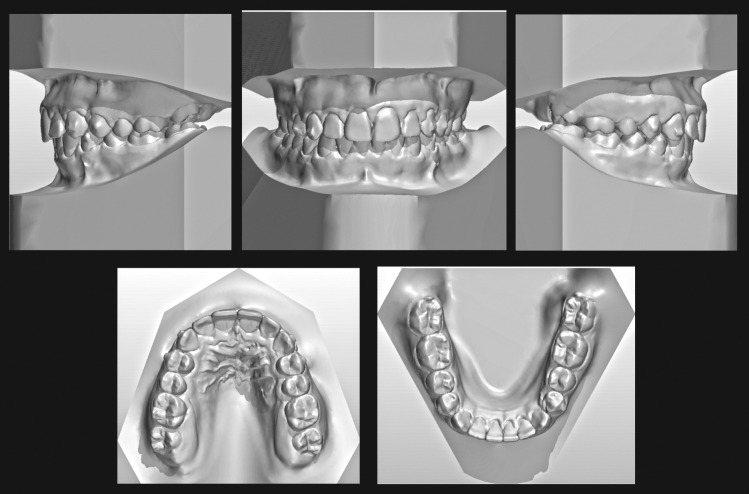

Treatment Result

Total treatment duration was approximately 2 months for both arches. At the end of treatment, a Class I molar relationship and normal overjet and overbite were achieved. Both dental arches were well aligned, although the maxillary lateral incisors appeared underrotated as was the mandibular left lateral incisor (Figures 7 through 9). After therapy, an improvement of periodontal indexes was recorded. The mean PPD values and the BOP rates in the maxillary and mandibular arches at all time points are shown in Table 1. The OHIP-14 filled out by the patient at T0, T1, and T2 showed a deterioration of OHRQoL limited to the third day postsurgery (T0 = 0; T1 = 11; T2 = 0). The posttreatment panoramic radiograph showed good root parallelism, no sign of crestal bone height reduction, and no evidence of apical root resorption (Figure 10).

Figure 7.

Posttreatment virtual 3-D models.

Figure 9.

Posttreatment extraoral photographs.

Table 1.

Mean PPD Values and BOP Rates in the Maxillary (Mx) and Mandibular (Md) Arches Before Oral Surgery (T0), at 1 Mo, (T1) and at the End of Treatment (T2)

Figure 10.

Posttreatment panoramic radiograph.

Figure 8.

Posttreatment intraoral photographs.

DISCUSSION

Reduction of orthodontic treatment time is considered a goal in the management of malocclusions.12 In the described case report, it was possible to complete treatment in approximately one-third the usual time using esthetic clear aligners. In this case, each aligner was in place for 5 days, rather than the usual 15 days, correcting the Class I malocclusion with moderate crowding. The addition of the corticotomy procedure has been reported to shorten the conventional orthodontic treatment time, and it has been claimed that teeth can be moved two to three times faster.5–7,13 The current case confirms previously published findings and supports this treatment option.

When responding to a traumatic stimulus, bony tissues initially undergo a biologic stage (RAP) characterized by a transient increase in bone turnover and a decrease in trabecular bone density.4,5 Based on recent studies, it seems that the length of the RAP is probably about 4 months.8,14 Considering this limit, in order to maximize the benefits of corticotomy in this case, we started treatment immediately after surgery.

Originally, conventional corticotomy-facilitated orthodontic treatment involved buccal and lingual osteotomy cuts with orthopedic forces.5,6 Alveolar augmentation with demineralized bone graft was also used to cover any fenestration and dehiscence and to increase the bony support for both the teeth and overlying soft tissues.5,6 Recent reports showed the results of selective corticotomy that was limited to the buccal and labial surfaces to reduce operation time and postoperative patient discomfort and to avoid the risk of violating vital lingual anatomy.15 In addition, there is no evidence in the literature that bone grafting of the alveolus enhances the stability of the orthodontic result.16 Therefore, in this report, a selective corticotomy technique, limited to the buccal surfaces and without bone grafts, was used.

Currently, the long duration of fixed orthodontic treatment increases the risk of caries and external root resorption, decreasing patient compliance.17 Clear aligners are relatively invisible (apart from a slight sheen to the teeth in close-up), easy to insert and remove, and comfortable to wear.18 In the described patient, there was an improvement in periodontal indexes, with a relevant reduction of PPD in the mandible. This result may be due to the removability of the appliance for oral hygiene and to the effect of reduced treatment time.

Finally, the limited deterioration of OHRQoL may encourage the use of corticotomy as a time reducer in selected orthodontic cases, but the efficacy of the combined use of these techniques must be proven by controlled clinical trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lagravere MO, Flores-Mir C. The treatment effects of Invisalign orthodontic appliances: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1724–1729. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavoni C, Lione R, Laganà G, Cozza P. Self-ligating versus Invisalign: analysis of dento-alveolar effects. Ann Stomatol. 2011;2:23–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long H, Pyakurel U, Wang Y, Liao L, Zhou Y, Lai W. Interventions for accelerating orthodontic toot movement: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:164–171. doi: 10.2319/031512-224.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baloul SS, Gerstenfeld LC, Morgan EF, Carvalho RS, Van Dyke TE, Kantarci A. Mechanism of action and morphologic changes in the alveolar bone in response to selective alveolar decortication-facilitated tooth movement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:S83–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcko WM, Wilcko T, Bouquot JE, Ferguson DJ. Rapid orthodontics with alveolar reshaping: two case reports of decrowding. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;21:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcko W, Wilcko MT. Accelerating tooth movement: the case for corticotomy-induced orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SJ, Park YG, Kang SG. Effects of corticision on paradental remodeling in orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:284–291. doi: 10.2319/020308-60.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanjideh PA, Rossouw PE, Campbell PM, Opperman LA, Buschang PH. Tooth movements in foxhounds after one or two alveolar corticotomies. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:106–113. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebaoun JD, Surmenian J, Dibart S. Accelerated orthodontic treatment with piezocision: a mini-invasive alternative to conventional corticotomies. Orthod Fr. 2011;82:311–319. doi: 10.1051/orthodfr/2011142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen AH., III Accelerated Invisalign treatment. J Clin Orthod. 2001;35:381–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassetta M, Di Carlo S, Giansanti M, Pompa V, Barbato E. The impact of osteotomy technique for corticotomy-assisted orthodontic treatment (CAOT) on oral health-related quality of life. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:1735–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassetta M, Pandolfi S, Giansanti M. Minimally invasive corticotomy in orthodontics: a new technique using a CAD/CAM surgical template. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:830–833. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer TJ. Orthodontic treatment acceleration with corticotomy-assisted exposure of palatally impacted canines: a preliminary study. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:417–420. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0417:OTAWCE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aboul-Ela SM, El-Beialy AR, El-Sayed KM, Selim EM, El-Mangoury NH, Mostafa YA. Miniscrew implant-supported maxillary canine retraction with and without corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Germeç D, Giray B, Kocaderelli I, Enacar A. Lower incisor retraction with a modified corticotomy. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:882–890. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0882:LIRWAM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews DP, Kokich VG. Accelerating tooth movement: the case against corticotomy-induced orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher MA, Wenger RM, Hans MG. Pretreatment characteristics associated with orthodontic treatment duration. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JW, Lee SJ, Lee CK, Kim BO. Orthodontic treatment for maxillary anterior pathologic tooth migration by periodontitis using clear aligner. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2011;41:44–50. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2011.41.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]