Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether orthodontic treatment in adults requiring oral rehabilitation is effective for increasing patients’ self-esteem and quality of life (QoL).

Materials and Methods:

The sample consisted of 102 adult patients (77 women and 25 men) aged between 18 and 66 years (mean, 35.1 years) requiring oral rehabilitation and orthodontic treatment simultaneously. Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem (RSE) Scale and a questionnaire about QoL based on the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) were used to determine self-esteem and QoL scores retrospectively. Questionnaires were carried out in two stages, T1 (start of treatment) and T2 (6 months after). To compare score changes between T1 and T2, the data obtained from the RSE Scale were evaluated with paired t tests, and data from the quality-of-life questionnaire were assessed by applying descriptive statistics.

Results:

The results showed a statistically significant increase in self-esteem (P < .001) and a great improvement on patients’ QoL.

Conclusions:

Orthodontic treatment causes a significant increase in self-esteem and QoL, providing psychological benefits for adult patients in need of oral rehabilitation.

Keywords: Adult, Self-esteem, Orthodontics, Quality of life, Oral rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasingly tendency nowadays for adult patients to seek orthodontic treatment,1–12 especially those needing oral rehabilitation. Esthetics are important in people’s lives, and facial appearance has a profound influence on personal attractiveness and self-esteem because it affects health and reverberates in social, affective, and professional relationships.2–4,6,10,12–18

Adult treatment demands an interdisciplinary approach,1,2,4,7 since periodontal disease increases with age,5 and tooth and bone loss cause migration of teeth and malocclusion. Periodontology prevents tissue damage, and orthodontics improves tooth position, promotes hygiene conditions and improves bone insertion.1,5 Thus, it is evident that an interdisciplinary interaction plays an important role in patients’ quality of life and self-esteem, especially in oral rehabilitation.1,2,4,7,11,19

Severe malocclusion involving the anterior teeth exerts both emotionally and psychosocially negative effects on patients’ lives.3,9,13,15 In addition, their perception of the malocclusion is often different from that of the orthodontist. It is common that patients present with high levels of concern for visible problems, but tolerate a less noticeable but more severe problem.6,15,17,20 Considering treatment time as one of the main concerns of adult patients, solving patients’ complains with an individualized approach, limiting the treatment to a functional correction and therefore reducing treatment time, should be the focus of orthodontic treatment.1,2,4,6,9,10,20

Some studies3,4,6,8,11–23 performed to collect evidence about the psychosocial profile of people seeking orthodontic treatment suggest that dentofacial problems can affect peoples’ well-being. The gap in the literature concerning this subject, as this treatment may affect patients in need of rehabilitation because it usually has its esthetic and compromised function, stimulated the development of this study.

The objective of this study was to determine whether orthodontic treatment in adults requiring oral rehabilitation is effective in enhancing patients’ self-esteem and quality of life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional and prospective study was based on patients’ answers to questions on assisted self-report forms. The ethics-in-research committee of Sagrado Coração University approved all procedures in this study.

Samples were selected from an orthodontic postgraduate program, a specialization course, and a private practice. Inclusion criteria were patients with a minimum age of 18 presenting with malocclusion requiring oral rehabilitation associated with orthodontic treatment. Patients with craniofacial syndromes, neurological or psychiatric disorders, or a history of previous orthognathic surgery were excluded.

The sample size was calculated by adopting a variation of dichotomous answers from T1 to T2, with a minimum mean difference to be detected of 20 (percentage points), a significance level of 5%, and power of 80%. Sample-size calculation required a minimum of 97 patients.

Initially, 130 patients with fixed appliances presenting with malocclusions caused by dental losses and agenesis in T1 were selected for the study. Three patients refused to participate in the study and 25 patients did not answer the questionnaires in T2, thus were excluded from the sample. The final sample consisted of 102 adult patients: 77 women (75.5%) and 25 men (24.5%) between 18 and 66 years of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Distribution Regarding Age (Years)

Patients agreed to participate in this research by signing a written informed consent, and after a brief explanation of the questionnaires, completed Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem (RSE) Scale and The Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14) questionnaire. Both questionnaires were applied during two stages: T1—early orthodontic treatment (1–3 months of treatment) and T2—after leveling and alignment phase (minimum of 8 months of treatment); the minimum interval from T1 to T2 was 6 months.

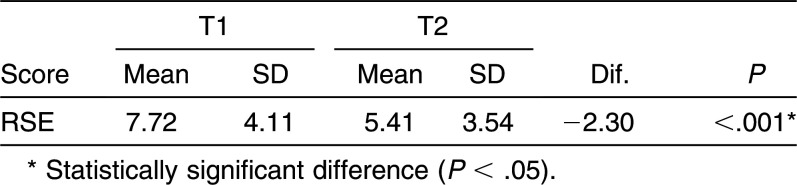

To evaluate self-esteem, the RSE questionnaire (Figure 1) had been previously validated and adapted to patients’ conditions.24 This scale comprises 10 questions; 5 are related to positive opinions and 5 to negative opinions, being interspersed to increase reliability of the questionnaire. For each question, a Likert Scale, consisting of four points (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree), was applied in order to provide adequate weight to the responses. Scores range from 0 to 3, where zero represents the highest level of self-esteem and 3 the lowest (Table 2); the lower the scores, the higher the patients’ self-esteem. This method proved to be a reliable method to measure self-esteem not only in the general population but also in orthodontic patients.15

Figure 1.

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale.

Table 2.

Calculation of Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale Scores

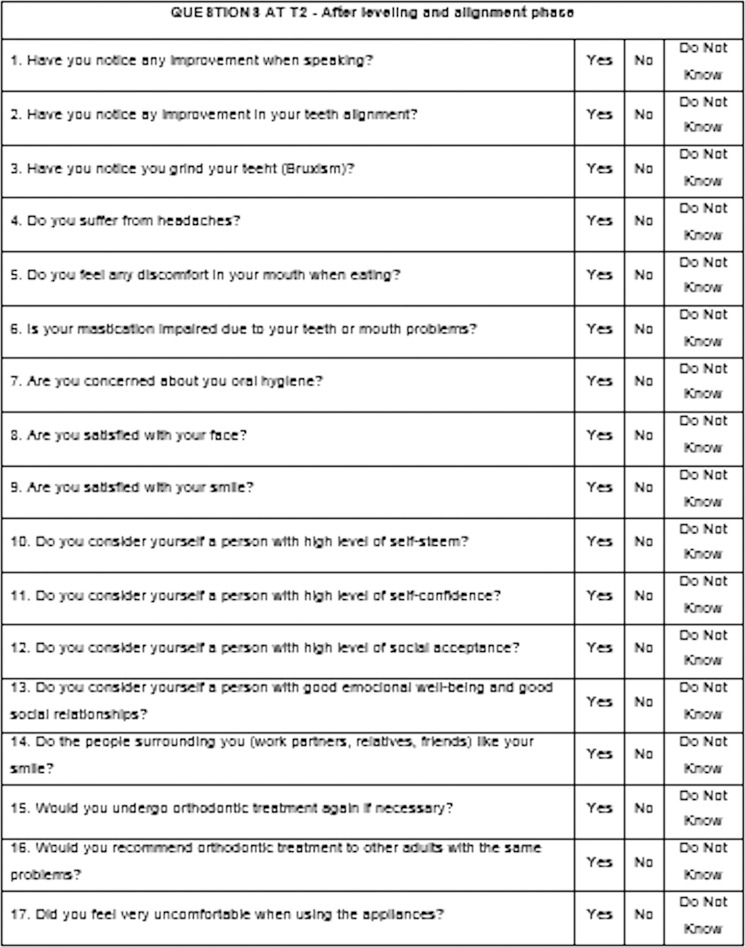

The applied questionnaire for quality of life assessment (Figures 2 and 3) was an adapted version of the OHIP-14.25 Modifications were made so that it would be more effective in measuring the quality of life related to orthodontic treatment. Thus, it was composed of 14 questions that were applied in T1 and T2 and 3 more added to the T2 stage to answer any doubts of the orthodontists regarding discomfort from the appliance and satisfaction with the treatment outcomes, which need no comparison. Another modification was directed to the response scheme, whereas the gradation system would not be sensitive to a two-stage modality. Finally, for better adaptation of this questionnaire, the researcher was advised by a psychologist with experience in this research protocol.

Figure 2.

QoL questionnaire at T1 (orthodontic treatment beginning).

Figure 3.

QoL questionnaire at T2 (after leveling and alignment phase).

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica software version 12 (StatSoft Inc, Tulsa, Okla). Paired t tests were used to compare the score changes from T1 to T2 in the RSE questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were used to assess the QoL-questionnaire scores. The results are described in the tables, using absolute frequency (n) and relative frequency (%), in addition to the mean and standard deviation parameters. The significance level was 5% (P < .05).

RESULTS

Results of the RSE questionnaire demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in self-esteem level from T1 to T2 (Table 3). In total, 70.6% of patients showed self-esteem improvement, 12.7% were unaltered, and self-esteem worsened in only 16.7% (Table 4).

Table 3.

Paired T Tests Comparing the Average Score in T1 and T2 for Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem (RSE) Scale Questionnaire

Table 4.

Frequency of Sample Score Variation in RSE Questionnaire: Improved (Scores Decreased From T1 to T2) or Worsened (Scores Increased From T1 to T2)

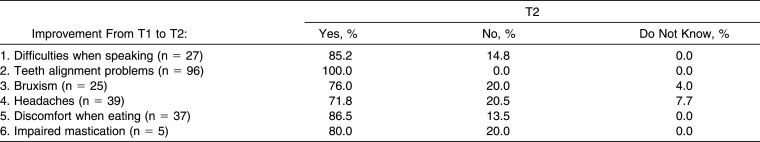

Results of the QoL questionnaire were similar to those of the RSE Scale and demonstrated an increased QoL level. Only for those patients who had answered yes in T1, questions 1 to 6 were separated and applied again in T2 (Table 5). Among the patients who had trouble speaking (question 1), 85% reported an improvement. One hundred percent of the patients who had alignment problems (question 2) and 76% of those who had bruxism (question 3) also reported improvement. Considering the patients who had suffered from headaches (question 4), 71.8% reported improvement as well. In addition, 86.5% of the patients who felt uncomfortable when eating (question 5) and 80% of those presenting with impaired mastication (question 6) reported improvement (Table 5).

Table 5.

Quality of Life Questionnaire Descriptive Statistics on T2 (Patients Who Answered Yes on Questions 1 to 6 in T1)

Concerns related to oral hygiene (question 7) increased from 78.4% to 98%. The percentage of patients satisfied with their faces (question 8) increased from 38.2% to 77.5%. In addition, the number satisfied with their smiles (question 9) increased from 14.7% to 97.1%. Specific issues related to self-esteem increased from 56.9% to 97.1% and regarding self-confidence from 60.8% to 96.1% (questions 10 and 11, respectively).

Only for those patients who had responded no in T1 did we separate questions 12 to 14 and apply them again in T2 (Table 6). Among those who had problems with social acceptance (question 12), 81.8% reported an improvement in this issue and, similarly, 80% of those who reported difficulties in social relationships and emotional well-being (question 13) demonstrated a noticeable improvement. When asked whether people liked their smile (question 14), 96.8% reported improvement; only 3.2% did not know about other people’s opinion, and there were no reports of disliking their smiles (Table 6).

Table 6.

Quality of Life Questionnaire Descriptive Statistics on T2 (Patients Who Answered No on Questions 12 to 14 in T1)

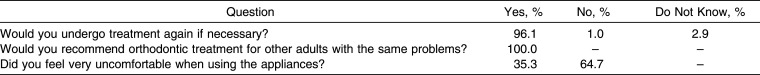

When patients were asked if they would undergo treatment again, 96.1% said yes; no, 1%; and 2.9% could not decide. It was interesting to note that 100% of patients recommended the treatment to adult patients. Finally, 35.3% of the patients reported considerable discomfort while using the appliances (Table 7).

Table 7.

Orthodontic Treatment Perception After Leveling and Alignment Phase

DISCUSSION

The increase in demand for orthodontic treatment in adults is justified, especially by the increasing preventive perspective of modern dentistry, esthetic appeal of society, longevity, increased access to information, technological advances of orthodontics, and psychosocial variations.1,2,4,6–19,22 Moreover, the perception of malocclusion differs between professionals and patients.23 Some people with severe malocclusion do not report a negative impact, while others with mild irregularities cited major impacts on their QoL.20 Esthetic reasons alone justify treatment, not only because it almost always results in a better patient self-image,23 but also because patients value esthetic and psychological benefits more than functional and dental health improvements.13,16

Women are more concerned with beauty and have a better perception of treatment need as well as esthetic results.1,4,9,11,12,14,22 This fact explains why, even in random samples such as in our study, there is a prevalence of females.4,6,9,11,14,18,21,22,26

In this study, it was found, by assessing the RSE questionnaire, that 70.6% of patients showed improvement in self-esteem, 12.7% were unaltered, and self-esteem worsened only in 16.7%. Therefore, there was a statistically significant difference in the self-esteem level of individuals, which improved from 7.72 at T1 to 5.41 at T2 (P < .001). At the end of treatment, this trend should increase even more, since patients posttreatment usually have higher self-esteem than during treatment or pretreatment.22 Another cross-sectional study assessed the effect of improvement after therapy in the long-term (6 months to 10 years) and stated that these benefits seem to be long-lasting.20

In order to assess more clearly the impact of treatment on a patient’s QoL, only for those patients who had answered yes in T1, we separated questions 1 to 6 and applied them again in T2. The patients whose answers were positive are considered the focus of this study. Among the 26.5% of patients who had trouble speaking, 85.2% reported an improvement. All patients who had alignment problems (94.1%) and 76% of those who had bruxism (24.5%) also reported improvements. Considering the patients who had suffered from headaches (38.2%), 71.8% reported improvement as well. In addition, 86.5% of the patients who felt uncomfortable when eating (36.3%) and 80% of the patients who presented with impaired mastication (4.9%) reported improvement. At the end of treatment, the percentage of patients who reported improvement in masticating would probably increase, as reported in another study.14

Health and body care are also considered quality-of-life issues. This could justify the increasing concern in oral hygiene from 78.4% to 98% of sample patients.

The number of patients satisfied with their faces increased considerably, from 38.2% to 77.5%. Even though orthodontic treatment not always privileges the face, this great improvement seems to be related to the better QoL reported by patients. Furthermore, the number of patients satisfied with their own smile increased, from 14.7% to 97.1%.

Regarding the specific issues of self-esteem and self-confidence, there was also a significant improvement with increased percentage of 56.9% to 97.1% for self-esteem and from 60.8% to 96.1% for self-confidence. These results show that self-esteem, social well-being, and QoL are closely related.11,15

Since the perception of facial appearance can affect health, social behavior, and happiness of the individual, it is safe to say that people with well-balanced smiles are considered more intelligent and have a greater chance of being employed.6,17 In order to observe more clearly the impact of these characteristics, we considered only patients who said no in T1 to questions 12 to 14 in the QoL questionnaire to be the focus of this research, because others have reported positive aspects. Of the 10.8% who originally said they did not have good social acceptance, 81.8% reported improvement; of the 4.9% who said they did not have a good relationship with people, 80% reported improvement in their relationships.

When patients were asked about others’ perception of their smile, 96.8% reported improvement, only 3.2% reported not knowing people’s opinions, and no patient reported others’ not liking his or her smile.

Several patients reported that they usually sought information about orthodontic treatment from other patients, which emphasized the latter’s important role in adult patient referrals.22 In another survey, 100% of patients would undergo treatment again if necessary and, based on their personal experience, would encourage other adults to undergo treatment as well.11 In this study, the results were similar, wherein 96.1% of the patients said they would undergo orthodontic treatment again if necessary, 1% would not, and 2.9% could not provide this information. It is noteworthy that all patients would recommend the treatment to other adults with similar problems. Thus, orthodontists should target this group, which is able to refer new patients for treatment.

The patients’ chief complaint during orthodontic treatment was oral pain,11,12,14 especially in the first 3 months, generating a negative impact on the overall QoL, then improving subsequently, although a significant improvement in self-esteem was reported.6 This information is useful in motivating patients during the adjustment period and encouraging them to finish treatment, considering that their expectations will probably be fulfilled.6 Corroborating those authors, 35.3% of patients in this study felt uncomfortable while using the appliances. The responses suggest that esthetic improvement generates a significant increase in QoL of adult patients,4,20 corroborating a systematic review stating that there is a modest association between malocclusion, orthodontic treatment need, and QoL.16

Even considering the significant sample size, these results should be analyzed with caution because the sample was selected in a specific area of the country. Therefore, it is important to conduct future studies involving more patients from different areas in developing countries such as Brazil.

Among the important features of this study were the significant sample size, the collection of data from a postgraduate program and a private practice, the assistance of a single researcher, a sample comprising only patients needing rehabilitation, and a QoL questionnaire specifically adapted for orthodontic patients. Moreover, the large variation in patients’ ages (43 young adults at 18–30 years, 55 adults at 31–59 years, and 4 adults aged over 60), made this study reliable because it covered all age groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Orthodontic treatment causes a significant increase in patients’ self-esteem and QoL.

The psychological benefits for adult patients in need of oral rehabilitation may occur because of the motivation obtained by the improved occlusion and smile esthetics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbosa VS, Bossolan APC, Casati MZ, Nociti JFH, Sallum EA, Silvério KG. Clinical considerations for orthodontic treatment in periodontal patients. PerioNews. 2012;6:635–641. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capelozza Filho L, Braga AS, Cavassan AO, Ozawa TO. Orthodontic treatment in adults: an objective approach. Rev Dent Press Ortodon Ortop Facial. 2001;6:63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimberg L, Arnrup K, Bondemark L. The impact of malocclusion on the quality of life among children and adolescents: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Eur J Orthod. 2015;37:238–247. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazit-Rappaport T, Haisraeli-Shalish M, Gazit E. Psychosocial reward of orthodontic treatment in adult patients. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:441–446. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gkantidis N, Christou P, Topouzelis N. The orthodontic-periodontic interrelationship in integrated treatment challenges: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johal A, Alyaqoobi I, Patel R, Cox S. The impact of orthodontic treatment on quality of life and self-esteem in adult patients. Eur J Orthod. 2015;37:233–237. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokich VG. Ortodoncia en adultos en el siglo XXI: lineamientos para alcanzar resultados exitosos. Rev Ateneo Argentino Odontol. 2007;XLVI:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolawole KA, Ayeni OO, Osiatuma VI. Evaluation of self-perceived dental aesthetics and orthodontic treatment need among young adults. Arch Oral Res. 2012;8:111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maltagliati LA, Montes LAP. Analysis of the factors that induce adult patients to search for orthodontic treatment. Rev Dent Press Ortodon Ortop Facial. 2007;12:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melo AC, Carneiro LO, Pontes LF, Cecim RL, de Mattos JN, Normando D. Factors related to orthodontic treatment time in adult patients. Dent Press J Orthod. 2013;18:59–63. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira PG, Tavares RR, Freitas JC. Assessment of motivation, expectations and satisfaction of adult patients submitted to orthodontic treatment. Dent Press J Orthod. 2013;18:81–87. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza RA, de Oliveira AF, Pinheiro SM, Cardoso JP, Magnani MB. Expectations of orthodontic treatment in adults: the conduct in orthodontist/patient relationship. Dent Press J Orthod. 2013;18:88–94. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernabe E, Flores-Mir C. Influence of anterior occlusal characteristics on self-perceived dental appearance in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:831–836. doi: 10.2319/082506-348.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Omiri MK, Abu Alhaija ES. Factors affecting patient satisfaction after orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:422–431. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0422:FAPSAO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung MH. An evaluation of self-esteem and quality of life in orthodontic patients: effects of crowding and protrusion. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:812–819. doi: 10.2319/091814.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, McGrath C, Hägg U. The impact of malocclusion/orthodontic treatment need on the quality of life: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:585–591. doi: 10.2319/042108-224.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pithon MM, Nascimento CC, Barbosa GC, Coqueiro Rda S. Do dental esthetics have any influence on finding a job. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silvola AS, Varimo M, Tolvanen M, Rusanen J, Lahti S, Pirttiniemi P. Dental esthetics and quality of life in adults with severe malocclusion before and after treatment. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:594–599. doi: 10.2319/060213-417.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alves e Silva AC, Carvalho RA, Santos Tde S, Rocha NS, Gomes AC, de Oliveira e Silva ED. Evaluation of life quality of patients submitted to orthognathic surgery. Dent Press J Orthod. 2013;18:107–114. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palomares NB, Celeste RK, Oliveira BH, Miguel JA. How does orthodontic treatment affect young adults’ oral health-related quality of life. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:751–758. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper-Kazaz R, Ivgi I, Canetti L, et al. The impact of personality on adult patients’ adjustability to orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:76–82. doi: 10.2319/010312-6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pabari S, Moles DR, Cunningham SJ. Assessment of motivation and psychological characteristics of adult orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:e263–e272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sardenberg F, Oliveira AC, Paiva SM, Auad SM, Vale MP. Validity and reliability of the Brazilian version of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics questionnaire. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:270–275. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dini GM, Quaresma MR, Ferreira LM. Translation into Portuguese, cultural adaptation and validation of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 2004;19:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira BH, Nadanovsky P. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile—short form. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw WC, Richmond S, Kenealy PM, Kingdon A, Worthington H. A 20-year cohort study of health gain from orthodontic treatment: psychological outcome. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]