Abstract

Background

As treatments for cancer have improved, more people are surviving cancer. However, compared to people without a history of cancer, cancer survivors are more likely to die of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Increased risk for CVD-related mortality among cancer survivors is partially due to lack of medication adherence and problems that exist in care coordination between cancer specialists, primary care physicians, and cardiologists.

Methods/Design

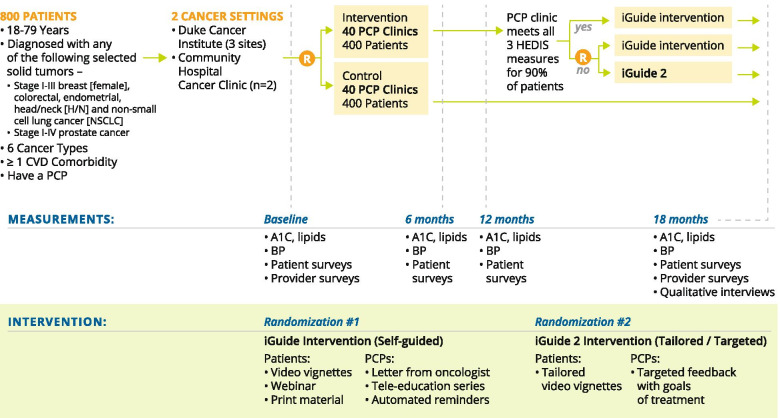

The Onco-primary care networking to support TEAM-based care (ONE TEAM) study is an 18-month cluster-randomized controlled trial with clustering at the primary care clinic level. ONE TEAM compares the provision of the iGuide intervention to patients and primary care providers versus an education-only control. For phase 1, at the patient level, the intervention includes video vignettes and a live webinar; provider-level interventions include electronic health records-based communication and case-based webinars. Participants will be enrolled from across North Carolina one of their first visits with a cancer specialist (e.g., surgeon, radiation or medical oncologist). We use a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) design.

Outcomes (measured at the patient level) will include Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures of management of three CVD comorbidities using laboratory testing (glycated hemoglobin [A1c], lipid profile) and blood pressure measurements; (2) medication adherence assessed pharmacy refill data using Proportion of Days Covered (PDC); and (3) patient-provider communication (Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care, PCC-Ca-36).

Primary care clinics in the intervention arm will be considered non-responders if 90% or more of their participating patients do not meet the modified HEDIS quality metrics at the 6-month measurement, assessed once the first enrollee from each practice reaches the 12-month mark. Non-responders will be re-randomized to either continue to receive the iGuide 1 intervention, or to receive the iGuide 2 intervention, which includes tailored videos for participants and specialist consults with primary care providers.

Discussion

As the population of cancer survivors grows, ONE TEAM will contribute to closing the CVD outcomes gap among cancer survivors by optimizing and integrating cancer care and primary care teams. ONE TEAM is designed so that it will be possible for others to emulate and implement at scale.

Trial registration

This study (NCT04258813) was registered in clinicaltrals.gov on February 6, 2020.

Keywords: Cancer survivorship, onco-primary care, primary care, oncology, health services research

Background

By 2030, there will be over 22 million cancer survivors [1]. Approximately 70% of cancer survivors have cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors (e.g., comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes) that require comprehensive care [2, 3]. Many have a higher risk of mortality from CVD than from cancer and these are often under recognized and under treated [2, 3]. Therefore, effective management of CVD risk is essential for reducing mortality among a growing population of cancer survivors. Due to the intensity of tests and treatments during diagnosis and survivorship, existing models of care generally do not integrate primary care or cardiology in patients with established CVD throughout patients’ cancer treatment continuum. Between 50% to 90% of PCPs care for long-term cancer survivors [4–7], yet there are numerous problems with the existing relationship with cancer specialists, including: suboptimal communication; uncertainty regarding each other’s roles, knowledge, and experiences; and appropriate referrals to other specialists [4, 6–13]. There is often disengagement by primary care providers during the active phase of cancer therapy, and they may or may not be reengaged after therapy is complete.

This lack of coordination of care can be harmful for chronic disease management among cancer survivors. For example, due to advances in screening, early detection, and cancer therapy, the 5-year survival rate in women with breast cancer now exceeds 90% [14, 15], with the survival rate for localized disease nearly 99% [16]. Unfortunately, the increased risk of CVD mortality manifests approximately 7 years after cancer diagnosis [17]. Research has focused on the risk of heart failure due to cancer therapy (e.g., anthracyclines, trastuzumab) [18–22], or coronary artery disease due to left-sided breast irradiation [23, 24]; however most CVD is largely due to aging, obesity, poor lifestyle habits, and other comorbidities like diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension [25–27]. With a median age of 63 years at time of breast cancer diagnosis, the majority of women will have at least one CVD risk factor [2, 21, 27, 28].

Adding another layer of complexity to the challenge of managing CVD risk is patients’ adherence to CVD-related medications. Among women with early stage breast cancer who were prescribed a statin prior to their breast cancer diagnosis, adherence significantly decreased from 1-year pre-diagnosis (67%) to 2-years post-diagnosis (35% ) [29]. Even by 3-years post diagnosis, the adherence rate (50%) was still substantially lower than the pre-cancer rate. This decrease is also seen with antihypertensive and oral diabetes medications [30]. Not surprisingly, women who are non-adherent with their CVD medications are also more likely to be non-adherent with their post-breast cancer hormonal therapy (e.g. aromatase inhibitor ) [31]. The ill effects of non-adherence are compounded by lifestyle issues such as weight gain and diminishing cardiorespiratory reserves, which generally occur during and after completion of cancer therapy [26, 32–37]. This pattern is not just found in women with breast cancer: there is a growing recognition that this pattern is also common in both genders and other cancer populations [38–48]. Consequently, compared to individuals without a cancer history, individuals with cancer have disproportionately higher burdens of CVD [46, 49–52].

These shortfalls in coordination of care, medication adherence, lifestyle changes, and focus on optimally controlling CVD risk factors highlight an urgent need for health care redesign. The cancer survivors’ PCP must become an integrated member of the cancer care team. The status quo of simply telling patients to follow-up with their PCP is insufficient. PCP follow-up is also inadequately addressed in most survivorship care plans. Therefore, we propose to implement an onco-primary care model and engage the PCP as an active member of the cancer team. The overarching goal of the Onco-primary care networking to support TEAM-based care (the ONE TEAM study), is to optimize the management and outcomes of individuals with cancer, both during and after treatment, and to develop a ‘low-touch’ multi-level intervention that can be generalized, adapted, and scaled in other health care systems with or without a survivorship clinic.

Methods/Design

The ONE TEAM study is an 18-month clustered randomized controlled trial with a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) design (Fig. 1) (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT04258813). We will prospectively enroll 800 patients with one of six newly diagnosed solid tumors (stage I-III breast, colorectal, endometrial, head/neck, and non-small cell lung cancer; stage I-IV prostate cancer) over a 3-year period, comparing a remotely delivered, low touch, patient- (n=400) and PCP- (n = 80) directed intervention with an education-only control.

Fig. 1.

Design of the ONE TEAM STUDY

To engage the PCP early in the process, we will enroll patients from across North Carolina at the time of one of their first visits with a cancer specialist (e.g., surgeon, radiation or medical oncologist) from two cancer settings (Fig. 1). Most participants will transition from active therapy to follow-up care during the 18-month study period, with the vast majority transitioning within 6-9 months.

The overall objective of ONE TEAM is to determine an optimal intervention that will improve patient outcomes according to the following measures: (1) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures of management of three CVD comorbidities using laboratory testing (glycated hemoglobin [A1c], lipid profile) and blood pressure measurements; (2) medication adherence assessed via pharmacy refill data using Proportion of Days Covered (PDC); and (3) patient-provider communication (Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care, PCC-Ca-36 ) [53].

Participants and randomization

Participants will be recruited from one of five cancer treatment sites at one of their first cancer specialist visits. These sites include three Duke Cancer Institute sites (Duke Medical Center, Duke Raleigh, Duke Regional) and two community oncology practices (Scotland Cancer Center in Lumberton, NC and Gibson Cancer Center in Laurinburg, NC). For the purposes of enrollment, a cancer specialist visit is defined as a visit with the surgeon, radiation oncologist, or medical oncologist. This will allow the research team to engage the participant’s PCP early in the process. We will identify potentially eligible participants in the electronic health record (EHR). If pathologic staging is not available at the time a patient is identified, the study team will hold off on recruitment until staging has been completed. At the time of the first cancer specialist visit, our research staff will introduce the study to the patient with a brief brochure. For interested individuals, our research staff will confirm eligibility and obtain informed consent. We will also collect reasons for non-participation. Following completion of study consent, the research team will collect the study measurements. We anticipate the survey will take most patients approximately 25 minutes to complete. Participants will be given a debit card, which will be loaded with $25 after completing each assessment at baseline, 6-, 12-, and 18-months. Participants will be given up to 2 weeks to complete the survey in person, online via REDCap, or over the phone with a research staff member depending on their preference. Those who are not able to complete the baseline survey within 2 weeks will be withdrawn from the study.

We will enroll a total of 800 individuals who meet the following inclusion criteria:

○ Diagnosed with incident Stage I-III breast [female], colorectal, endometrial, and head/neck, Stage I-III non-small cell lung cancer [NSCLC], or stage I-IV prostate cancer

○ Treated with curative intent

○ 18-79 years old at the time of cancer diagnosis

○ Has at least one of three CVD risk factors / comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia) – based upon whether the patient is currently on a medication for the comorbidity at time of recruitment

○ Had a visit with their PCP in the previous 12 months and has CVD comorbidities managed by the PCP

Individuals will be ineligible if they have had a myocardial infarction in the previous 24 months, have a diagnosis of heart failure with an ejection fraction <30% or of stage IV-V chronic kidney disease (eGFR <30). Participants who progress to metastatic disease during the course of the 18-month study period will be allowed to continue to participate unless they voluntarily withdraw from the study.

We will use a SMART design with two randomizations [54–57]. The unit of analysis will be the patient. The unit of randomization will be the PCP clinic. We selected this approach to avoid contamination between PCPs within a clinic. We will stratify each randomization by category of PCP (Duke PCP, non-Duke PCP). We selected this stratification factor to maintain a balance between the two arms with respect to PCP setting. The first randomization, will occur at enrollment, and participants will be cluster randomized to the self-guided multi-level iGuide intervention or control arm.

The second randomization will occur at 12-months [55, 57], and we will use an embedded dynamic treatment regimen [54, 55] (also referred to as an adaptive intervention ) [58, 59]. PCP clinics in the intervention arm will be considered non-responders if 90% or more of their participating patients do not meet the modified HEDIS quality metrics at the 6-month measurement. These clinics will be randomized to a more intensified and tailored intervention (iGuide 2) or continue on (iGuide 1). We are using the 6-month data to determine the threshold for second randomization eligibility because of the potential timing of patient enrollment. This approach allows additional time for patients to enter the trial and contribute additional data to a given cluster. Assessments will be conducted at study enrollment, 6-months, 12-months, and 18-months. Because of variability in appointment scheduling, we will allow a window of one month for assessment. iGuide 1 consists of two patient-level and four PCP-level components (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intervention components

| iGuide intervention (Self-guided) | iGuide2 (Tailored/Targeted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-level components |

(1) the patient-level brief video vignettes with a written summary describing: (a) importance of heart health, (b) how your primary care provider can help you during and after cancer treatment; (c) heart health: taking your medicines properly; (d) taking control of blood pressure; (e) eating well to maintain your health; (f) keeping your heart healthy by staying active; and (g) life after cancer therapy and managing more than one health problem. (2) patient-facing webinars hosted by a cancer survivor, medical oncologist, primary care provider, and other relevant providers. |

Tailored video vignettes with pre-video tip sheets designed to inform patient about: (a) value-based goal setting, (b) readiness and self-efficacy for chronic disease management, (c) taking medication as prescribed, (d) and preparing for an office visit. |

| PCP-level components |

(1) a brief letter from our research team notifying the PCP that their patient has enrolled and a brief description of the study; (2) a brief EHR-templated letter from the cancer care team notifying the PCP of the patient’s cancer diagnosis; and indicating the cancer team and PCP’s roles in in managing the patient’s conditions; (3) a monthly tele-education, case-based series that covers case management recommendations from oncology experts to help expand the PCP’s capacity to manage complex diseases; (4) quarterly automated treatment update messages from the cancer team sent through the EHR reinforcing the importance of CVD risk factor management |

(1) cancer specialist-facing dashboard that will be oncologist-specific versions of the study Enrollment report listing each of the HEDIS measures (2) specialist-to-PCP quarterly automated letter offering a case review |

Intervention components

iGuide 1: patient-level intervention

Participants randomized to the control group (n=400) will receive current guideline-concordant cancer care. We will also provide information for healthy living during and after cancer and for preparing for transition from cancer therapy to follow-up care. Monthly, patient education material on healthy living will be sent to the participants via the patient portal or by mail, based on participant’s preference. Near the completion of therapy, they will be provided the NCI Facing Forward: Life After Cancer booklet [60]. PCPs will receive a brief letter from our research team notifying them that their patient has cancer and has joined the study. They will also be asked to complete baseline and end of study surveys. This approach is not fully equivalent to an attention control as there will be touch points in the iGuide 1 and iGuide 2 interventions that we cannot match for the control group. Also, we will not engage the PCPs in clinics randomized to the control group.

Participants in the multi-level intervention will receive the iGuide 1 interventions. These patient-level components include seven brief video vignettes with a written summary and a live webinar. The scripted 3-minute video vignettes (one per month) will cover the following topics: (1) overview and importance of managing CVD risk factors; (2) role of the PCP during and after cancer care; (3) importance of medication adherence to prevent CVD events; (4) blood pressure control; (5) healthy diet for cancer and prevention of heart disease; (6) physical activity for cancer survivors and prevention of heart disease; and (7) transitioning off of therapy and managing other comorbidities. Each of the vignettes will be accompanied by a printed, one-page, bulleted summary, written at the 7th grade reading level. In accordance with a patient’s preference, all materials will be available via the patient portal (MyChart), online streaming, and on a USB drive.

We will also conduct one patient-facing webinar for each recruitment group (50 minutes). Each live webinar will discuss the importance of managing CVD risk factors during and after cancer therapy and will include a moderator, a cancer specialist, a PCP, and a cancer survivor. The panelists will provide their perspective on the importance of managing non-cancer comorbidities during therapy and the role of the PCP during and after cancer therapy. Following these short perspectives, there will be a question and answer session. Survivors in the iGuide 1 Intervention arm will be invited to one webinar. If a participant cannot attend the webinar, a recorded copy of the webinar will be sent on a USB drive, and the participant will be invited to the next webinar (with the next group). All webinars will be recorded and can be watched again with video plus audio or audio only.

iGuide 1: PCP-Level Intervention

There are four components in iGuide 1 at the PCP-level: (1) a brief letter from our research team notifying the PCP that their patient has cancer and has enrolled in our study; (2) a brief letter from the cancer care team asking the PCP to actively manage CVD comorbidities during and after cancer treatment; (3) invitations to a monthly tele-education, case-based series with free Continuing Medical Education (CME) credits; (4) and quarterly automated treatment update letters from the cancer care team reinforcing the importance of CVD risk factor management. These letters will be delivered through Epic as an InBasket message for Duke PCPs and by autofax for outside PCPs. We have partnered with Duke Office of Clinical Research (DOCR) to develop an efficient workflow approach requiring a minimum of steps and avoiding EHR fatigue. The letters to the PCP from the research team and cancer care team will be automatically sent by our EHR at the closing of the participant encounters (at baseline, months 6, 12, 18) or letter encounters (at months 3, 9, 15).

The PCPs with patients in the intervention group will be invited to a monthly, 45-minute case-based, tele-education series. The format for the series has been adapted from Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) a validated method that expands PCP capacity to manage complex diseases by sharing knowledge, disseminating best practices, and building a community of practice [61–65]. In designing the format, we adopted the implementation tools and best practices developed by Serhal et al. [66] A ‘Hub’ and ‘Spoke’ model will be used wherein the research team and cancer specialists at Duke Cancer Institute and our two community oncology practices will serve as content experts (the hub), and PCPs in the intervention arm will be the spokes. In this approach, a short didactic lecture is delivered by a member of the hub team and recommendations for case management are offered by the community in response to anonymized clinical cases presented by the spoke sites. PCPs will receive Continuing Medical Education credit for each session attended.

iGuide 2

At the 12-month time point, we will assess the three HEDIS measures for CVD risk factors for the survivors in the intervention arm, using fasting laboratory values (A1c, lipid profile) and blood pressure measurements performed by our research staff, as well as other key measures shown in Table 2. We will determine which PCP clinics do not have at least 90% of their participants meeting all three HEDIS quality measures based on all available 6-month assessments. We set the 90% bar recognizing that some clinics may have only a few participants. PCP clinics (and their patients) not meeting this threshold will be considered ‘non-responders’ and randomized to either the iGuide 2 intervention or to continue on the iGuide 1 intervention.

Table 2.

Key measures

| Measures | Definition / Criteria | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||

| HEDIS measures [67–69] |

BP <140/90 mm Hg A1c <8.0% On statin if diabetic or ASCVD risk > 10% |

BP by research staff, fasting labs, EHR |

| Proportion of days covered [70, 71] | Ratio of the number of days the patient is covered by a mediation during a refill period | EHR |

| PCC-Ca-36 [53] | Patient-centered communication: exchanging information, making decisions, fostering healing relationships, enabling patient self-management, managing uncertainty, and responding to emotions | Patient self-report survey |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Voils’ medication adherence self-report measure [72, 73] (modified) | Measure of adherence & reasons for non-adherence of medication for key CVDs | Patient self-report survey |

| Haggerty et al [74] (modified) Vimalananda et al. [75] (modified) | Multiple perspectives of care coordination | Patient- and provider- survey |

| FACIT-COST [76] | Cancer care-related financial toxicity | Patient self-report survey |

| Objective self-report measure [77] | Amount of out-of-pocket expense on care by spending type (e.g., medication, copayments, etc.) | Patient survey |

| Patient activation measure (PAM) [78] | Patient engagement | Patient self-report survey |

iGuide 2 Patient-level Intervention

For the iGuide 2 patient-level intervention (Table 1), we will use a tailored approach. Patients will receive four monthly, 5-minute video vignettes that incorporate a pre-video tip sheet. We will send the tip sheets and video vignettes in the method preferred by the patient (as noted above), using the patient portal, online streaming, or a USB drive with printed versions of the tip sheets. In developing the video vignettes, we will use motivational interviewing and goal setting techniques [79, 80]. Based upon responses, the patient will select which video vignette to watch (i.e., who is most like me). Patients will be able to watch any of the other videos they choose. The topics for the four video vignettes will be: (1) value-based goal setting; (2) tips based on readiness; (3) tips to take your medicine as prescribed; and (4) preparing for an office visit. At the end of each video, patients will be asked to create a list of one or two items to discuss with their PCP.

iGuide 2 PCP-level intervention

We will implement a cancer specialist-facing EHR dashboard that includes the specialists’ patients who are enrolled in the study and are in the intervention arm. The HEDIS quality measures for our three CVD risk factors will be used. The dashboard will be populated with data available in the EHR for the specific patient. Quarterly, starting with the second randomization, an automated asynchronous specialist-to-PCP letter will be sent to iGuide 2 PCPs offering a case review.

Dissemination to participants

At the end of the study both patients and PCPs will be mailed a newsletter with a summary of the study findings. In addition, patients in the control group will be sent a copy of the printed materials along with a USB drive with the video vignettes and a recorded webinar.

Statistical considerations

The aims of this study will be analyzed as intent to treat. To account for the study design, we will use longitudinal mixed models. Each model will specify fixed effects for both intervention (i.e. control, iGuide 1, or iGuide 2) and time point (i.e. enrollment, 6-months, 12 months, and 18 months). An interaction between the fixed effects of time point and treatment will be included. Time point and cluster (PCP location) will be included as random effects.

For each of the three primary aims, a separate model will be built. The HEDIS measurement will be included as a binary variable (criteria met vs. not met). For this model, a binomial distribution with a logit link will be specified. Medication adherence, defined as percent days covered (PDC), will be modeled as a continuous outcome with a Gaussian distribution and identity link. Similarly, the patient-centered communication survey (PCC-CA-36) will be modeled as a continuous outcome. From the PCC-CA-36 data, an overall score will be computed as the average of all questions consistent with recommendations from the developers [53]. Secondary aims include self-reports of medication adherence, cancer care-related financial toxicity, out-of-pocket expenses by category of spending (e.g. medication), engagement, and care coordination. Because of the subjective nature of these endpoints, we will categorize each of these variables into quartiles and then analyze them in multivariable analysis using logit regression models with the top quartile category as the comparator and the remaining three quartiles as the reference group.

After each model is built, the primary hypotheses will be tested by constructing a contrast of effects over the period from enrollment to 18 months comparing iGuide 1 and iGuide 2 versus control.

Sample size calculations

This is a cluster-randomized trial design with a binary outcome, assuming 32 PCP clinics per arm with 10 subjects per clinic, alpha=0.05, and intra-cluster correlation (ICC) ranging from 0.05 to 0.10, assuming at 18 months that the control arm patients will have 50% compliance on the 3 HEDIS measures and the intervention arm will have 65% compliance. With this combination of factors, the power ranges from 0.80 to 0.89, depending upon ICC level. If we assume approximately 20% drop-out due to death or loss to follow-up, we require 40 PCP clinics per arm with an average of 10 subjects per clinic.

Discussion

Informed by implementation science, the ONE TEAM study is intended to meaningfully change the longitudinal care of cancer survivors by coordinating care with primary care physicians and empowering patients. Currently, cancer survivors are often lost-to-primary care, and as such, they are not being monitored for non-cancer related comorbidities and potential risk factors and behaviors. Compounding the problem, cancer treatments often exacerbate underlying cardiovascular disease and have other transient effects, as do underlying issues associated with developing cancer, such as obesity and smoking. Further, cancer treatments can result in new negative behaviors, such as poor diet and lack of exercise, which can also affect cardiovascular comorbidities, diabetes, and other diseases. The result of all these factors is that cancer survivors die from co-morbidities earlier and at a greater frequency than their counterparts who have not had cancer [2, 3].

To counter this, ONE TEAM was designed to be a low touch delivered intervention, designed to help both the patient and the PCP feel more comfortable with post-cancer care and to help increase adherence to non-cancer medications. One limitation of this study is that our cohort is limited to those who have a PCP, and more work will need to be done to engage those without a PCP. However, because of its relatively low human resource use, if effective, ONE TEAM could be scaled-out in other settings, be used in low resource settings in a variety of age groups across diverse populations.

Conclusions

As the population of cancer survivors grows, ONE TEAM will contribute to closing the CVD outcomes gap among cancer survivors by optimizing and integrating cancer care and primary care teams. ONE TEAM is designed so that it will be possible for others to emulate and implement at scale.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DCI

Duke Cancer Institute

- EHR

Electronic health record

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ONE TEAM

Onco-primary care networking to support TEAM-based care

- PCP

Primary care provider

Authors’ contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Conceptualization: LZ, KO, RA. Development of Methodology: LZ, MS, KO, BN, TH, BR, TC. Statistical methodology: BN, TH. Data Curation: MS, BN, TH. Writing Original Draft: LZ, KO. Provision of medical expertise: KO, LO, KS, RS, LS, MS, SYZ, NS, SD. Supervision: LZ, KO. Project administration: RA. Funding acquisition: LZ, KO. Writing Review and Editing: LZ, MS, BN, TH, RA, TC, LO, BR, KS, RS, LS, MD, SYZ, NS, SD, KO. Provision of critical input: LZ, MS, BN, TH, RA, TC, LO, BR, KS, RS, LS, MD, SYZ, NS, SD, KO.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA249568-01). Statistical support was funded by the Duke Cancer Institute through NCI CCSG award number P30CA014236 (PI: Kastan). The funders have no role in study design, data analysis, or any aspect of the project, including the peer review of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

N/A: Data and materials have not been developed yet.

To ensure participant privacy, data will not be openly shared. All Principal Investigators will be given access to the cleaned data sets.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board. Study participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

N/A: This is paper describes a protocol.

Competing interests

The authors report no financial or non-financial interests related to the current work.

Unrelated to the current work, Dr. Zullig reports research funding from Proteus Digital Health and the PhRMA Foundation, as well as consulting from Novartis and Pfizer. Dr. Zafar reports employment and stock from Shattuck Labs (to his spouse), serving on advisory boards for Vivor, LLC (uncompensated) and Cancer Support Community (uncompensated), serving on the Board of Directors ffor Family Reach (uncompensated), and being a board member for WCG IRB. Dr. Zafar also reports research funding from AstraZeneca and consulting for RTI, McKesson, Quintiles, and Change Healthcare. Dr. Dent reports research funding from Novartis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019;69(5):363–385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogle KS, Swanson GM, Woods N, Azzouz F. Cancer and comorbidity. Cancer. 2000;88(3):653–663. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<653::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunda A, Eberl M, Oeffinger K, Hudson M, Mahoney M. Care of cancer survivors. American Family Physician. 2005;15(4):699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonough AL, Rabin J, Horick N, Lei Y, Chinn G, Campbell EG, Park ER, Peppercorn J. Practice, preferences, and practical tips from primary care physicians to improve the care of cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(7):e600–e606. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, Klabunde CN, Smith T, Aziz N, Earle C, Ayanian JZ, Ganz PA, Stefanek M. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klabunde CN, Ambs A, Keating NL, He Y, Doucette WR, Tisnado D, Clauser S, Kahn KL. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1058-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klabunde CNHP, Earle CC, Smith T, Ayanian JZ, Lee R, Ambs A, Rowland JH, Potosky AL. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam Med. 2013;45:463–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, Hudson MM. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(6):804–812. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, Reaman GH, Tyne C, Wollins DS, Hudson MM. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):631–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung WY, Aziz N, Noone AM, Rowland JH, Potosky AL, Ayanian JZ, Virgo KS, Ganz PA, Stefanek M, Earle CC. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: a comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):343–354. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dossett LA, Hudson JN, Morris AM, Lee MC, Roetzheim RG, Fetters MD, Quinn GP. The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: a systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67(2):156–169. doi: 10.3322/caac.21385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein EB, Miller WL, Hudson SV, Howard J, O'Malley D, Tsui J, Lee HS, Bator A, Crabtree BF. Cancer survivorship care in advanced primary care practices: a qualitative study of challenges and opportunities. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1726–1732. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, Rowland JH. Going beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1978–1981. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gernaat SAM, Ho PJ, Rijnberg N, Emaus MJ, Baak LM, Hartman M, Grobbee DE, Verkooijen HM. Risk of death from cardiovascular disease following breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(3):537–555. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4282-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gernaat SAM, Boer JMA, van den Bongard DHJ, Maas A, van der Pol CC, Bijlsma RM, Grobbee DE, Verkooijen HM, Peeters PH. The risk of cardiovascular disease following breast cancer by Framingham risk score. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;170(1):119–127. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4723-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradshaw PT, Stevens J, Khankari N, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI, Gammon MD. Cardiovascular disease mortality among breast cancer survivors. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, Carver J, Constine LS, Denduluri N, Dent S, Douglas PS, Durand JB, Ewer M, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):893–911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YA, Cho H, Lee N, Jung SY, Sim SH, Park IH, Lee S, Lee ES, Kim HJ. Doxorubicin-induced heart failure in cancer patients: a cohort study based on the Korean National Health Insurance Database. Cancer Med. 2018;7(12):6084–6092. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinder MC, Duan Z, Goodwin JS, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3808–3815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Long JB, Hurria A, Owusu C, Steingart RM, Gross CP. Incidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy after adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):2504–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chavez-MacGregor M, Zhang N, Buchholz TA, Zhang Y, Niu J, Elting L, Smith BD, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity among older patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4222–4228. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.7884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boekel NB, Jacobse JN, Schaapveld M, Hooning MJ, Gietema JA, Duane FK, Taylor CW, Darby SC, Hauptmann M, Seynaeve CM, et al. Cardiovascular disease incidence after internal mammary chain irradiation and anthracycline-based chemotherapy for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(4):408–418. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0159-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet AM, Blom-Goldman U, Bronnum D, Correa C, Cutter D, Gagliardi G, Gigante B, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):987–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cespedes Feliciano EM, Kwan ML, Kushi LH, Weltzien EK, Castillo AL, Caan BJ. Adiposity, post-diagnosis weight change, and risk of cardiovascular events among early-stage breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;162(3):549–557. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Muss HB, Pituskin EN, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, Coan AD, Herndon JE, 2nd, Douglas PS, et al. Cardiopulmonary function and age-related decline across the breast cancer survivorship continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2530–2537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weaver KE, Foraker RE, Alfano CM, Rowland JH, Arora NK, Bellizzi KM, Hamilton AS, Oakley-Girvan I, Keel G, Aziz NM. Cardiovascular risk factors among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancers: a gap in survivorship care? J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(2):253–261. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence Trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calip GS, Boudreau DM, Loggers ET. Changes in adherence to statins and subsequent lipid profiles during and following breast cancer treatment. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2013;138(1):225–233. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calip GS, Elmore JG, Boudreau DM. Characteristics associated with nonadherence to medications for hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(1):161–172. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4043-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neugut AI, Zhong X, Wright JD, Accordino M, Yang J, Hershman DL. Nonadherence to medications for chronic conditions and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1326–1332. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feliciano EMC, Kwan ML, Kushi LH, Weltzien EK, Castillo AL, Caan BJ. Adiposity, post-diagnosis weight change, and risk of cardiovascular events among early-stage breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2017;162(3):549–557. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koelwyn GJ, Khouri M, Mackey JR, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Running on empty: cardiovascular reserve capacity and late effects of therapy in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(36):4458–4461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mutschler NS, Scholz C, Friedl TWP, Zwingers T, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW, Fehm T, Mohrmann S, Salmen J, Ziegler C, et al. Prognostic impact of weight change during adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-risk early breast cancer: results from the ADEBAR Study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(2):175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang FF, Liu S, John EM, Must A, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet quality of cancer survivors and noncancer individuals: results from a national survey. Cancer. 2015;121(23):4212–4221. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vagenas D, DiSipio T, Battistutta D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Rye S, Bashford J, Pyke C, Saunders C, Hayes SC. Weight and weight change following breast cancer: evidence from a prospective, population-based, breast cancer cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:28. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huneidi SA, Wright NC, Atkinson A, Bhatia S, Singh P. Factors associated with physical inactivity in adult breast cancer survivors-A population-based study. Cancer Med. 2018;7(12):6331–6339. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alibhai SM, Duong-Hua M, Sutradhar R, Fleshner NE, Warde P, Cheung AM, Paszat LF. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3452–3458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Francisco L, Steinberger J, Kurian S, Wong FL, Sharp J, Sposto R, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Late congestive heart failure after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(34):5537–5543. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armenian SH, Yang D, Teh JB, Atencio LC, Gonzales A, Wong FL, Leisenring WM, Forman SJ, Nakamura R, Chow EJ. Prediction of cardiovascular disease among hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. Blood Adv. 2018;2(14):1756–1764. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018019117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker KS, Ness KK, Steinberger J, Carter A, Francisco L, Burns LJ, Sklar C, Forman S, Weisdorf D, Gurney JG, et al. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular events in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Blood. 2007;109(4):1765–1772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowles EJA, Yu O, Ziebell R, Chen L, Boudreau DM, Ritzwoller DP, Hubbard RA, Boggs JM, Burnett-Hartman AN, Sterrett A, et al. Cardiovascular medication use and risks of colon cancer recurrences and additional cancer events: a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):270. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cespedes Feliciano EM, Kroenke CH, Meyerhardt JA, Prado CM, Bradshaw PT, Dannenberg AJ, Kwan ML, Xiao J, Quesenberry C, Weltzien EK, et al. Metabolic dysfunction, obesity, and survival among patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(30):3664–3671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felix AS, Lehman A, Foraker RE, Naughton MJ, Bower JK, Kuller L, Sarto GE, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Jackson RD, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease among women with endometrial cancer compared to cancer-free women in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;51:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen PL, Je Y, Schutz FA, Hoffman KE, Hu JC, Parekh A, Beckman JA, Choueiri TK. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with cardiovascular death in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2011;306(21):2359–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banegas MP, Emerson MA, Adams AS, Achacoso NS, Chawla N, Alexeeff S, Habel LA. Patterns of medication adherence in a multi-ethnic cohort of prevalent statin users diagnosed with breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2018;12(6):794–802. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0716-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuart BC, Davidoff AJ, Erten MZ. Changes in medication management after a diagnosis of cancer among medicare beneficiaries with diabetes. Journal of oncology practice. 2015;11(6):429–434. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang J, Neugut AI, Wright JD, Accordino M, Hershman DL. Nonadherence to oral medications for chronic conditions in breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(8):e800–e809. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.011742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB, Simard EP, Boscoe FP, Henley SJ, Jemal A, Cho H, Anderson RN, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(9):1290–1314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith A, Reeve B, Bellizzi K, Harlan L, Klabunde CN, Amsellem M, Bierman A, Hays R. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Car Financ. 2008;29:41–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deckx L, van den Akker M, Metsemakers J, Knottnerus A, Schellevis F, Buntinx F. Chronic diseases among older cancer survivors. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:206414. doi: 10.1155/2012/206414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zullig LL, Smith VA, Lindquist JH, Williams CD, Weinberger M, Provenzale D, Jackson GL, Kelley MJ, Danus S, Bosworth HB. Cardiovascular disease-related chronic conditions among Veterans Affairs nonmetastatic colorectal cancer survivors: a matched case-control analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:6793–6802. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S191040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reeve BB, Thissen DM, Bann CM, Mack N, Treiman K, Sanoff HK, Roach N, Magnus BE, He J, Wagner LK, et al. Psychometric evaluation and design of patient-centered communication measures for cancer care settings. Patient education and counseling. 2017;100(7):1322–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung YK, Chakraborty B, Davidson KW. Sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) with adaptive randomization for quality improvement in depression treatment program. Biometrics. 2015;71(2):450–459. doi: 10.1111/biom.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kidwell KM, Seewald NJ, Tran Q, Kasari C, Almirall D. Design and analysis considerations for comparing dynamic treatment regimens with binary outcomes from sequential multiple assignment randomized trials. J Appl Stat. 2018;45:1628–1651. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2017.1386773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murphy SA. An experimental design for the development of adaptive treatment strategies. Stat Med. 2005;24(10):1455–1481. doi: 10.1002/sim.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lei H, Nahum-Shani I, Lynch K, Oslin D, Murphy SA. A “SMART” design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:21–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004;5(3):185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nahum-Shani I, Qian M, Almirall D, Pelham WE, Gnagy B, Fabiano GA, Waxmonsky JG, Yu J, Murphy SA. Experimental design and primary data analysis methods for comparing adaptive interventions. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(4):457–477. doi: 10.1037/a0029372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buzaglo JS, Miller SM, Kendall J, Stanton AL, Wen KY, Scarpato J, Zhu F, Lyle J, Rowland J. Evaluation of the efficacy and usability of NCI's Facing Forward booklet in the cancer community setting. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):63–73. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, Dion D, Pullara F, Bjeletich B, Simpson G, Alverson DC, Moore LB, Kuhl D, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154–160. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arora S, Kalishman S, Thornton K, Dion D, Murata G, Deming P, Parish B, Brown J, Komaromy M, Colleran K, et al. Expanding access to hepatitis C virus treatment--Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project: disruptive innovation in specialty care. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):1124–1133. doi: 10.1002/hep.23802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Furlan AD, Zhao J, Voth J, Hassan S, Dubin R, Stinson JN, Jaglal S, Fabico R, Smith AJ, Taenzer P et al. Evaluation of an innovative tele-education intervention in chronic pain management for primary care clinicians practicing in underserved areas. J Telemed Telecare 2018:1357633X18782090. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Scott JD, Unruh KT, Catlin MC, Merrill JO, Tauben DJ, Rosenblatt R, Buchwald D, Doorenbos A, Towle C, Ramers CB, et al. Project ECHO: a model for complex, chronic care in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(8):481–484. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.GTH113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, Aron DC, Todd-Stenberg J, Moore BA, Kerns RD, Au DH, Ho PM, Kirsh SR. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090–1100. doi: 10.1111/pme.12715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Serhal E, Arena A, Sockalingam S, Mohri L, Crawford A. Adapting the consolidated framework for implementation research to create organizational readiness and implementation tools for project ECHO. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2018;38(2):145–151. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Controlling high blood pressure. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/controlling-high-blood-pressure/. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

- 68.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Comprehesive diabetes care. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/comprehensive-diabetes-care/. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

- 69.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Statin therapy for patients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/statin-therapy-for-patients-with-cardiovascular-disease-and-diabetes/

- 70.Pharmacy Quality Aalliance. https://www.pqaalliance.org. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

- 71.Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, Konieczny JL, Steiner JF. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care. 2013;51(8 Suppl 3):S11–S21. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b1d2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Voils CI, King HA, Thorpe CT, Blalock DV, Kronish IM, Reeve BB, et al. Content validity and reliability of a self-report measure of medication nonadherence in hepatitis C treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Voils CI, Maciejewski ML, Hoyle RH, Reeve BB, Gallagher P, Bryson CL, Yancy WS., Jr Initial validation of a self-report measure of the extent of and reasons for medication nonadherence. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1013–1019. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318269e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haggerty JL, Roberge D, Freeman GK, Beaulieu C, Breton M. Validation of a generic measure of continuity of care: when patients encounter several clinicians. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):443–451. doi: 10.1370/afm.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vimalananda VG, Fincke BG, Qian S, Waring ME, Seibert RG, Meterko M. Development and psychometric assessment of a novel survey to measure care coordination from the specialist's perspective. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(3):689–699. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, Blinder V, Araujo FS, Hlubocky FJ, Nicholas LH, O'Connor JM, Brockstein B, Ratain MJ, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Cancer. 2017;123(3):476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, Taylor DH, Goetzinger AM, Zhong X, Abernethy AP. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuccero D, Railey K, Briggs M, Hull SK. Behavioral health in prevention and chronic illness management: motivational interviewing. Prim Care. 2016;43(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768–780. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

N/A: Data and materials have not been developed yet.

To ensure participant privacy, data will not be openly shared. All Principal Investigators will be given access to the cleaned data sets.