Abstract

Introduction

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a crucial prognosis predictor following several major operations. However, the association between NLR and the outcome after hip fracture surgery is unclear. In this meta-analysis, we investigated the correlation between NLR and postoperative mortality in geriatric patients following hip surgery.

Method

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane library, and Google Scholar were searched for studies up to June 2021 reporting the correlation between NLR and postoperative mortality in elderly patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture. Data from studies reporting the mean of NLR and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were pooled. Both long-term (≥ 1 year) and short-term (≤ 30 days) mortality rates were included for analysis.

Result

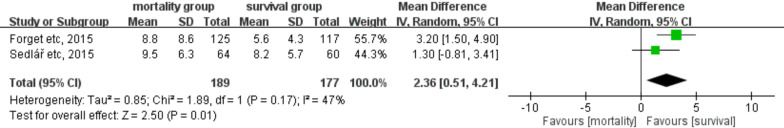

Eight retrospective studies comprising a total of 1563 patients were included. Both preoperative and postoperative NLRs (mean difference [MD]: 2.75, 95% CI: 0.23–5.27; P = 0.03 and MD: 2.36, 95% CI: 0.51–4.21; P = 0.01, respectively) were significantly higher in the long-term mortality group than in the long-term survival group. However, no significant differences in NLR were noted between the short-term mortality and survival groups (MD: − 1.02, 95% CI: − 3.98 to 1.93; P = 0.5).

Conclusion

Higher preoperative and postoperative NLRs were correlated with a higher risk of long-term mortality following surgery for hip fracture in the geriatric population, suggesting the prognostic value of NLR for long-term survival. Further studies with well-controlled confounders are warranted to clarify the predictive value of NLR in clinical practice in geriatric patients with hip fracture.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13018-021-02831-6.

Keywords: Hip fracture, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, Mortality

Introduction

Hip fracture is a serious, devitalizing condition in the geriatric population. The global number of hip fractures is expected to exceed 6 million by 2050 [1]. Older individuals are more susceptible to hip fractures, with poor outcomes [2]. The mortality of patients with hip fracture at 30 days and 1 year after surgery is estimated to be 19% and 20–30%, respectively [3]. Hip fractures are perceived as a major threat in elderly individuals because of the high morbidity and mortality rates (14–36%) [4, 5], with physical function restored in only a few patients after surgery [6]. Hip fractures can result in an immediate public health concern due to the increasing global geriatric population. Therefore, understanding the prognosis in these individuals is highly important.

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a novel inflammatory marker, is the ratio of the absolute neutrophil to absolute lymphocyte count. It provides an indication of the systemic inflammatory burden [7]. NLR is relatively a cost-effective and easily accessible laboratory biomarker in routine clinical practice [8]. Several studies have indicated that NLR can predict outcomes at 30 days, 6 months, and 12 months after emergency abdominal surgery (overall accuracy for 30 days, 6 months, and 12 months was 77%, 68%, and 62%, respectively) [9] and after major vascular surgery in elderly patients [10]. Bhat et al. and Tan et al., in their reviews, concluded that NLR, as a prognostic biomarker, may be superior to white cell count or subtypes individually [11, 12].

The systemic immune-inflammation index is associated with poor all-cause mortality in older adults with hip fracture undergoing surgery [13]. Forget et al. reported that a postoperative day 5 NLR value > 5 following hip fracture surgery was associated with a high mortality risk [14]. Multiple studies have also reported that a higher preoperative NLR value is related to a higher risk of death after hip fracture surgery [15–17]. However, certain studies have found no significant association between NLR and postoperative mortality [18–20]. Clinical evidence on the association between NLR and hip fracture mortality in elderly patients remains varied, awaiting further evidence.

Considering the mixed results from current evidence, we explored the predictive value of NLR for mortality following hip fracture surgery in elderly patients. We hypothesized that a higher perioperative NLR value is associated with higher short- and long-term mortality rates after hip fracture surgery.

Methods

Study design and search strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses guidelines [21, 22]. PubMed, Embase, Cochrane library, and Google Scholar were searched for relevant studies published from November 29, 2014 to June 30, 2021, reporting the association between NLR and postoperative mortality in elderly patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture. The search strategy included a comprehensive set of keywords: (“Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio” or “neutrophil lymphocyte ratio” or “neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio” or “NL ratio” or “NLR”) and (“hip fracture” or “hip fractures”). No language restrictions were imposed and reference lists of included studies were screened.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) studies evaluating the prognostic value of high pre- and postoperative NLR for short- or long-term postoperative mortality following hip fracture surgery; (ii) elderly patients aged ≥ 65 years; and (iii) availability of complete NLR data.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) studies measuring neutrophil or lymphocyte counts separately instead of NLR, since NLR could not be calculated by the average neutrophil or lymphocyte counts in the ex post analysis (ii) studies with patients younger than 65 years; (iii) studies involving patients with multiple fractures; and (iv) studies without admission NLR data.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (H-HS and Y-HC) independently extracted data from individual studies. The extracted data included the study timeframe, publication year, country, design and setting, number of patients, mean age, cutoff value, pre- and postoperative NLR measurement, selection of threshold for NLR elevation, and follow-up duration. The extracted information was checked by a third author (Y-TT).

The methodological quality of each study was also assessed and scored independently by the two review authors (H-HS and Y-HC) according to Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-version 2 (QUADAS-2) [23]. In case of disagreement between the two authors, the third author (Y-TT) intervened to resolve the concern and make a final decision. The QUADAS-2 tool had four sections: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The Review Manager 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) software was used to process and present the assessment results.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome of interest was the correlation between preoperative NLR and long-term mortality (≥ 1 year) in patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture. Secondary outcomes were the association between postoperative NLR and long-term mortality (≥ 1 year) and that between preoperative NLR and short-term (≤ 30 days) post-surgical mortality.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

The extracted data were combined using ReviewManager 5.3 for the meta-analysis. The differences in both pre- and postoperative NLR between survivors and nonsurvivors were estimated using mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from each included study. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of < 0.05. Heterogeneity among the included studies were assessed using the Chi-squared test (Chi2), Cochrane Q, and I-squared statistic test (I2). A Cochrane Q P value of < 0.1 and I2 values > 50% were considered significant heterogeneity [24]. A random-effects model was chosen based on the amount of heterogeneity.

In certain studies, calculations were used for some of the missing direct data. In studies that provided only the median, minimum, and maximum, we calculated the mean using Hozo’s formula [25]. In studies that did not provide the exact number of patient deaths, we multiplied the total number of patients with the mortality rate.

Possible publication biases were visually checked using a funnel plot. Egger’s statistical test was used to determine the small study effect. A statistically significant P value of < 0.05 suggested the presence of a small study effect.

Results

Identification of included studies

A comprehensive search of three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane library) led to identification of 143 relevant studies. An additional 130 studies were found through Google Scholar. These 130 studies included reports, news, and original papers. The study selection process is detailed in Fig. 1. Finally, eight studies deemed relevant were included in this meta-analysis [14–19, 26, 27]. Of these studies, five reported the predictive value of preoperative NLR on long-term mortality, four reported the predictive value of preoperative NLR on short-term mortality, and two reported the predictive value of postoperative NLR on long-term mortality.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection according to PRISMA guidelines

Quality assessment of the included studies

The methodological analysis of the included studies was based on the QUADAS-2 assessment, where the results indicated bias risk and applicability (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). In terms of patient selection and reference standards, nearly all studies demonstrated low risk, except for the study by Altinsoy et al., which showed a high risk as descriptions of the included population were lacking. In the index test, nearly all studies demonstrated an unclear risk, with a low concern of applicability. This is because the index test in these studies was a blood test for NLR and there was no description on how it was obtained. However, the blood test for NLR did not interfere with the judgement for the review question, resulting in low concerns on applicability.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 1. All eight studies were single-center, retrospective trials comprising a total of 1563 patients. The mean age of the population was 82.26 years. Of the eight studies, four had provided their separate cutoff and respective sensitivity and specificity values. The cutoff values varied from 5.25 to 9.635 preoperatively, and only one result of postoperative cutoff value was mentioned.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Year | Country | Design, center | Models | Endpoint | Sample size | NLR cutoff | Age (years) Mean ± SD/median (min–max) |

Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bingol et al. [15] | 2020 | Turkey | Retrospective, single center | Preoperative NLR |

30-day mortality 1-year mortality |

241 | 6.55 | 81.09 ± 8.11 | 12 months |

| Özbek et al. [16] | 2020 | Turkey | Retrospective, single center | Preoperative NLR | 1-year mortality | 55 | 5.25 |

Nonsurvivors: 83.54 ± 7.3 Survivors: 79.90 ± 7.6 |

Maximum follow-up period of 27 months |

| Atlas et al. [19] | 2020 | Turkey | Retrospective, single center |

Preoperative NLR Postoperative day 5 NLR |

7-day mortality | 132 |

Preoperative: 9.635 Postoperative: 21.07 |

80 ± 8.4 | 7 days |

| Temiz et al. [17] | 2019 | Turkey | Retrospective case control study, single center | Preoperative NLR | 1-year mortality | 50 | 4.7 |

Nonsurvivors: 73.81 (65–80) Survivors: 72.71 (67–80) |

> 1 year |

| Niessen et al. [18] | 2018 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort study, single-center | Preoperative NLR | Hospital discharge and intra-hospital mortality | 535 | N/A |

Survivors: 84 ± 7 Nonsurvivors: 85 ± 9 |

N/A |

| Altinsoy et al. [27] | 2018 | Turkey | Retrospective, single center |

Preoperative NLR Postoperative day 1 NLR |

Died in the ICU during the postoperative period | 199 | N/A |

Survivors: 80.54 ± 6.942 Nonsurvivors: 85.47 ± 5.423 |

N/A |

| Sedlář et al. [26] | 2015 | Czech | Retrospective, single center |

Preoperative NLR Postoperative NLR |

5-year mortality | 104 | N/A | Mean age: 80 ± 9 years | 48–84 (median: 60) |

| Forget et al. [14] | 2015 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort study, single center |

Preoperative NLR Postoperative day 5 NLR |

Patient’s survival time | 242 | Postoperative day 5: 5 | Median age: 85 years (66–102) | 21 |

max maximum, min minimum, NLR neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio, N/A not available, SD standard deviation

Predictive value of preoperative NLR on long-term mortality

Of the eight studies, five comprising 697 patients with hip fracture compared preoperative NLR between survivors and nonsurvivors with a follow-up duration of > 1 year (Fig. 2). Our findings revealed that preoperative NLR was significantly higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors (MDs: 2.78, 95% CI: 0.26–5.30; P = 0.03). However, significant heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I2: 77%, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the mean difference in preoperative NLR between the mortality and the survival groups with a follow-up duration of > 1 year

Predictive value of postoperative NLR on long-term mortality

Of the eight studies, two comprising 271 patients with hip fracture compared postoperative NLR between survivors and nonsurvivors with a follow-up duration of > 1 year (Fig. 3). Our analysis revealed that postoperative NLR was significantly higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors (MDs: 2.24, 95% CI: 0.38–4.10; P = 0.02). In addition, no significant heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I2: 34%, P = 0.22).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the mean difference in postoperative NLR between the mortality and survival groups with a follow-up duration of > 1 year

Predictive value of preoperative NLR on short-term mortality

Of the eight studies, four comprising 1139 patients with hip fracture compared preoperative NLR between survivors and nonsurvivors with a follow-up time within 30 days after surgery (Fig. 4). In this meta-analysis, postoperative NLR was found to be lower in nonsurvivors than in survivors, although the difference was not significant (MDs: − 1.02, 95% CI: − 3.98 to 1.93; P = 0.50). Moreover, significant heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I2: 77%, P = 0.005).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the mean difference in preoperative NLR between the mortality and survival groups with a follow-up duration of > 30 days

Publication bias

A funnel plot for the meta-analysis of the primary outcome is presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S2. Asymmetry could be visualized easily, and only five studies were included in the funnel plot. Egger’s statistical test revealed no evidence of publication bias (t = − 1.417, P = 0.25). However, the test is more reliable when the number of studies is > 10.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis revealed that NLR was associated with long-term mortality after hip fracture surgery. Both pre- and postoperative NLR values were significantly higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors when the follow-up duration was > 1 year. However, our results also showed that NLR failed to predict short-term mortality within 30 days after hip fracture surgery in elderly patients.

Systemic inflammation, which can be reflected by NLR, is known to be associated with prognosis following hip fracture surgery [28]. Studies have reported a similar pathophysiology of systemic inflammation and acute inflammatory markers, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-10, which are associated with outcomes after hip fracture [13, 29]. In addition, elevated CRP and ferritin, which are common inflammatory markers determined in routine clinical practice, could successfully predict 30-day mortality after hip fracture [28]. However, the economic and easily accessible NLR has potential in clinical use for predicting the mortality risk following hip fracture surgery in elderly patients. This meta-analysis provides comprehensive evidence on the strong correlation between a higher NLR value and mortality risk following hip fracture surgery, offering a significant reference in clinical decision making.

In addition to indicating systemic inflammation, NLR may also reflect general health condition, such as activity of daily living, comorbidities, and nutritional status [20, 30, 31], which are crucial to the prognosis of hip fracture and its survival [32]. In a study, NLR was associated with the nutritional status. It can be a useful nutritional marker for evaluating the nutritional status of geriatric patients [33]. Inflammation was hypothesized to reduce albumin levels through reduced synthesis, increased catabolism, and translocation of albumin to extravascular pools [34]. Lower NLR level was reported to be correlated with higher albumin level and health outcomes in patients receiving hemodialysis [35]. Moreover, low serum albumin level is a sole indicator of the increased risk of in-hospital death, postoperative complications, and total mortality after hip fracture surgery in elderly patients [36]. Therefore, higher baseline NLR in geriatric patients with hip fracture may indicate poor baseline nutritional status and thereby a higher mortality risk following hip fracture surgery.

In postoperative patients with hip fracture, major cardiovascular disease is a risk factor for high mortality [20], which may be indicated by the NLR value. Systemic inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of cardiogenic shock. In these patients, high neutrophil count was characteristic and associated with increased mortality after myocardial infarction. It was also a marker for larger area of infarction [37]. Neutrophilia may be the result of hypercholesterolemia through complicated mechanisms of enhanced granulopoiesis, mobilization from the bone marrow, and decreased clearance. The high inflammatory activity due to these interactions can lead to atherosclerotic plaques becoming unstable and prone to rupture, resulting in a cardiovascular event [38]. Peng et al. revealed that NLR is a more sensitive independent prognostic biomarker in patients with myocardial infarction than the neutrophil or lymphocyte percentage alone [39]. Patients with hip fracture are at an increased risk of both myocardial infarction and stroke up to 1 year following the hip fracture [40]. This fact can explain the finding that patients with hip fracture having higher baseline NLR may be prone to cardiovascular risk, resulting in higher mortality than patients with relatively lower baseline NLR.

In our meta-analysis, NLR was a significant predictor of long-term, rather than 30-day, mortality after hip fracture surgery in elderly individuals. The discrepancy in the weight of NLR as a predictor of short- and long-term mortality following hip fracture surgery in elderly patients may attribute to the causes of death at different postoperative time points. The most common causes of death in 30-day mortality was respiratory failure, followed by cardiac failure [41]. However, the most common cause of long-term mortality following hip fracture surgery was cardiovascular disease, followed by infectious diseases [41, 42]. Considering that NLR is a sensitive, independent prognostic biomarker in patients with myocardial infraction [39], it is sensible to associate its significance for long-term, rather than 30-day, mortality following surgery for hip fracture in this meta-analysis. On the contrary, the small number of studies included in this meta-analysis could have caused the high heterogenicity, resulting in the nonsignificance of the association between the NLR and 30-day postoperative mortality. Therefore, more evidence is warranted to clarify the discrepancy in the predictor value of NLR for the short- and long-term mortality following hip fracture surgery in elderly individuals.

NLR was associated with systemic inflammation, nutritional status, and cardiovascular risk, likely affecting the survival of elderly patients after hip fracture surgery. However, these factors were not excluded or adjusted in all the eight studies included in this meta-analysis. Thus, we could not determine which of these factors resulted in high NLR or had multifactorial associations. In a well-controlled study including patients with hip fracture, Ozbek et al. [16] found no difference in the NLR level between the deceased and survival groups. This implies the need to clarify NLR as an independent predictor of mortality risk in geriatric patients with hip fracture. To the best of our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the most extensive study investigating the association of NLR with mortality following hip fracture surgery. In addition, our study included some data points that were adjusted for potential confounding factors, making it more reliable than an individual study. With knowledge of NLR as a potential prognostic factor, clinicians can adopt a stratified care approach by prioritizing geriatric patients with hip fracture at a high risk of mortality for intensive care [43].

Limitations

There are several limitations of this meta-analysis. First, although the association between the NLR and mortality risk after hip fracture surgery was clear, we failed to find a uniformed cutoff value with acceptable sensitivity and specificity due to lack of sufficient data. Second, mortality rates varied among studies, which may be attributed to the variations in baseline characteristics of enrolled patients in each study, resulting in heterogeneity in our reported outcomes. Age, sex, comorbidities, surgical delay, cognitive impairment, and poor renal function at presentation are important confounders and should be controlled at baseline to clarify NLR as an independent predictor of postoperative mortality in future studies. Third, all included studies were retrospective trials. Therefore, selection bias, recall bias, and other biases should be considered, which may also cause heterogeneity in pooled outcomes. Fourth, we failed to present the correlation between postoperative NLR and short term mortality (≤ 30 days) owing to the insufficient data. More studies are warranted to clarify this issue. Last, the large ethnic diversity and small sample size may cause sampling error. However, according to a statistical study, small sample size may or may not cause a noticeable bias in MDs as we expected [44]. Further studies with larger populations and a sufficient patient number are required to validate our study results.

Conclusion

The findings of this meta-analysis revealed that higher pre- and postoperative NLR was associated with a higher long-term mortality risk following surgery for hip fracture in the geriatric population. However, whether NLR is an independent predictor of postoperative mortality risk in patients with hip fracture must be clarified by further well-controlled studies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Methodological quality summary: QUADAS-2 and Funnel plot.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Laboratory Animal Center at TMU for the English editing supportand to Taipei Medical University (Grant numbers TMU110-AE1-B07) for financially supporting this research.

Abbreviations

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- QUADAS-2

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-version 2

Authors' contributions

YHC and CHC searched and selected included data from public dataspace separately, and they anaylzed and interpreted the data together. MHS and YJK provided expert opinion of how to corporate result to clinical use and made great contribution to data analysis, interpretation and writing. HHS and YTT made great contribution in writing and provided brilliant interpretation with supporting data. YPC was in charge of study, provided expert opinion and take responsibility as the corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the publication of this article: Taipei Medical University (Grant numbers TMU110-AE1-B07).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in these published article [citation: 15–19, 26, 27].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yu-Hang Chen and Ching-Hsin Chou contributed equally as first authors

References

- 1.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Vuori I, Järvinen M. Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone. 1996;18(1 Suppl):57s–63s. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nazrun AS, Tzar MN, Mokhtar SA, Mohamed IN. A systematic review of the outcomes of osteoporotic fracture patients after hospital discharge: morbidity, subsequent fractures, and mortality. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:937–948. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S72456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran CG, Wenn RT, Sikand M, Taylor AM. Early mortality after hip fracture: is delay before surgery important? J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2005;87(3):483–489. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mnif H, Koubaa M, Zrig M, Trabelsi R, Abid A. Elderly patient's mortality and morbidity following trochanteric fracture. A prospective study of 100 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(7):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mundi S, Pindiprolu B, Simunovic N, Bhandari M. Similar mortality rates in hip fracture patients over the past 31 years. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(1):54–59. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.878831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbert J, Crotty M, Whitehead C, Cameron I, Kurrle S, Graham S, et al. Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation after hip fracture is associated with improved outcome: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(7):507–512. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uslu AU, Küçük A, Şahin A, Ugan Y, Yılmaz R, Güngör T, et al. Two new inflammatory markers associated with Disease Activity Score-28 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet–lymphocyte ratio. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(7):731–735. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Z, Fu Z, Huang W, Huang K. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(3):641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaughan-Shaw PG, Rees JR, King AT. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in outcome prediction after emergency abdominal surgery in the elderly. Int J Surg. 2012;10(3):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhutta H, Agha R, Wong J, Tang TY, Wilson YG, Walsh SR. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio predicts medium-term survival following elective major vascular surgery: a cross-sectional study. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;45(3):227–231. doi: 10.1177/1538574410396590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat T, Teli S, Rijal J, Bhat H, Raza M, Khoueiry G, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cardiovascular diseases: a review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;11(1):55–59. doi: 10.1586/erc.12.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan TP, Arekapudi A, Metha J, Prasad A, Venkatraghavan L. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio as predictor of mortality and morbidity in cardiovascular surgery: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(6):414–419. doi: 10.1111/ans.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z-C, Jiang W, Chen X, Yang L, Wang H, Liu Y-H. Systemic immune-inflammation index independently predicts poor survival of older adults with hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02102-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forget P, Moreau N, Engel H, Cornu O, Boland B, De Kock M, et al. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) after surgery for hip fracture (HF) Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(2):366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bingol O, Ozdemir G, Kulakoglu B, Keskin OH, Korkmaz I, Kilic E. Admission neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio to predict 30-day and 1-year mortality in geriatric hip fractures. Injury. 2020;51(11):2663–2667. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Özbek EA, Ayanoğlu T, Olçar HA, Yalvaç ES. Is the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio a predictive value for postoperative mortality in orthogeriatric patients who underwent proximal femoral nail surgery for pertrochanteric fractures? Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2020;26(4):607–612. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2020.57375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temiz A, Ersözlü S. Admission neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and postoperative mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2019;25(1):71–74. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2018.94572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atlas A, Duran E, Pehlivan B, Pehlivan VF, Erol MK, Altay N. The effect of increased neutrophil lymphocyte ratio on mortality in patients operated on due to hip fracture. Cureus. 2020;12(1):e6543. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niessen R, Bihin B, Gourdin M, Yombi J-C, Cornu O, Forget P. Prediction of postoperative mortality in elderly patient with hip fractures: a single-centre, retrospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0646-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche JJW, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331(7529):1374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38643.663843.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorlund K, Imberger G, Johnston BC, Walsh M, Awad T, Thabane L, et al. Evolution of heterogeneity (I2) estimates and their 95% confidence intervals in large meta-analyses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e39471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sedlář M, Kvasnička J, Krška Z, Tománková T, Linhart A. Early and subacute inflammatory response and long-term survival after hip trauma and surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(3):431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altinsoy S, Çatalca S, Sayin MM, Ergil J. YOĞUN BAKIM KALÇA KIRIĞI HASTALARINDA NÖTROFİL LENFOSİT ORANININ POSTOPERATİF ERKEN DÖNEM MORTALİTE VE MORBİDİTEYE ETKİSİ. Anestezi Dergisi. 2018;26(4):234–237. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norring-Agerskov D, Bathum L, Pedersen OB, Abrahamsen B, Lauritzen JB, Jørgensen NR, et al. Biochemical markers of inflammation are associated with increased mortality in hip fracture patients: the Bispebjerg Hip Fracture Biobank. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(12):1727–1734. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun T, Wang X, Liu Z, Chen X, Zhang J. Plasma concentrations of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and outcome prediction in elderly hip fracture patients. Injury. 2011;42(7):707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An P, Zhou X, Du Y, Zhao J, Song A, Liu H, et al. Association of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio with mild cognitive impairment in elderly Chinese adults: a case-control study. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2019;16(14):1309–1315. doi: 10.2174/1567205017666200103110521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winangun IMA, Aryana IGPS, Astika IN, Kuswardhani RAT. Relationship of albumin serum levels and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratios (NLR) on activities of daily living elderly patients with delirium at Sanglah General Hospital, Bali, Indonesia. Bali Med J. 2020;9(1):7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2012;43(6):676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaya T, Açıkgöz SB, Yıldırım M, Nalbant A, Altaş AE, Cinemre H. Association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and nutritional status in geriatric patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33(1):e22636. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doweiko JP, Nompleggi DJ. The role of albumin in human physiology and pathophysiology, part III: albumin and disease states. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1991;15(4):476–483. doi: 10.1177/0148607191015004476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz-Martinez J, Campa A, Delgado-Enciso I, Hain D, George F, Huffman F, et al. The relationship of blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with nutrition markers and health outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(7):1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s11255-019-02166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li S, Zhang J, Zheng H, Wang X, Liu Z, Sun T. Prognostic role of serum albumin, total lymphocyte count, and mini nutritional assessment on outcomes after geriatric hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(6):1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chia S, Nagurney JT, Brown DFM, Raffel OC, Bamberg F, Senatore F, et al. Association of leukocyte and neutrophil counts with infarct size, left ventricular function and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(3):333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azab B, Chainani V, Shah N, McGinn JT. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of major adverse cardiac events among diabetic population: a 4-year follow-up study. Angiology. 2013;64(6):456–465. doi: 10.1177/0003319712455216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng Y, Wang J, Xiang H, Weng Y, Rong F, Xue Y, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in cardiogenic shock: a Cohort study. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e922167. doi: 10.12659/MSM.922167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedersen AB, Ehrenstein V, Szépligeti SK, Sørensen HT. Hip fracture, comorbidity, and the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke: a Danish nationwide cohort study, 1995–2015. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(12):2339–2346. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groff H, Kheir MM, George J, Azboy I, Higuera CA, Parvizi J. Causes of in-hospital mortality after hip fractures in the elderly. Hip Int. 2020;30(2):204–209. doi: 10.1177/1120700019835160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boereboom FT, Raymakers JA, Duursma SA. Mortality and causes of death after hip fractures in The Netherlands. Neth J Med. 1992;41(1–2):4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penrod JD, Litke A, Hawkes WG, Magaziner J, Koval KJ, Doucette JT, et al. Heterogeneity in hip fracture patients: age, functional status, and comorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(3):407–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin L. Bias caused by sampling error in meta-analysis with small sample sizes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0204056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Methodological quality summary: QUADAS-2 and Funnel plot.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in these published article [citation: 15–19, 26, 27].