Abstract

Purpose

Radiation-induced toxicity (RIT) is usually assessed by inspection and palpation. Due to their subjective and unquantitative nature, objective methods are required. This study aimed to determine whether a quantitative tool is able to assess RIT and establish an underlying BED-response relationship in breast cancer.

Methods

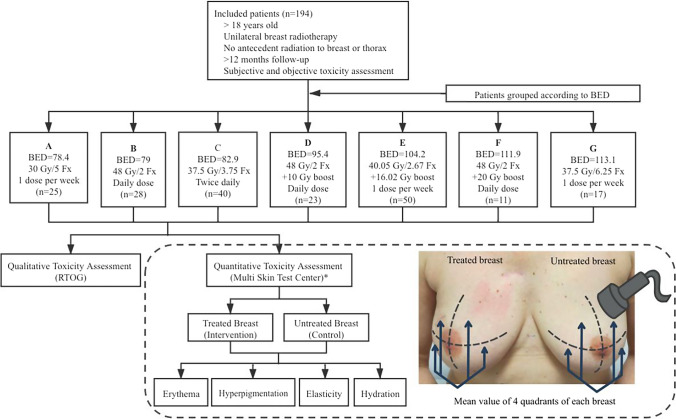

Patients following seven different breast radiation protocols were recruited to this study for RIT assessment with qualitative and quantitative examination. The biologically equivalent dose (BED) was used to directly compare different radiation regimens. RIT was subjectively evaluated by physicians using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) late toxicity scores. Simultaneously an objective multiprobe device was also used to quantitatively assess late RIT in terms of erythema, hyperpigmentation, elasticity and skin hydration.

Results

In 194 patients, in terms of the objective measurements, treated breasts showed higher erythema and hyperpigmentation and lower elasticity and hydration than untreated breasts (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.019, respectively). As the BED increased, Δerythema and Δpigmentation gradually increased as well (p = 0.006 and p = 0.002, respectively). Regarding the clinical assessment, the increase in BED resulted in a higher RTOG toxicity grade (p < 0.001). Quantitative assessments were consistent with RTOG scores. As the RTOG toxicity grade increased, the erythema and pigmentation values increased, and the elasticity index decreased (p < 0.001, p = 0.016, p = 0.005, respectively).

Conclusions

The multiprobe device can be a sensitive and simple tool for research purpose and quantitatively assessing RIT in patients undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. Physician-assessed toxicity scores and objective measurements revealed that the BED was positively associated with the severity of RIT.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12094-021-02729-z.

Keywords: Radiation-induced toxicity, Biological equivalent dose, Quantitative assessment, Objective evaluation, Breast cancer, Radiotherapy

Introduction

The incidence of breast cancer has increased in recent years and is expected to continue to rise in the next decade [1]. Radiation therapy (RT) is an important complementary treatment that improves local–regional control and reduces the risk of cancer recurrence [2]. However, despite the advances in radiotherapy planning and treatment technology, approximately 30–40% of irradiated patients will suffer late RIT, with complications including dermatitis, fibrosis, desquamation (moist or dry) and even necrosis. As a result, RIT may affect the function of the skin and appearance of the breast, key factors impacting patient satisfaction and quality of life. Nevertheless, as exemplified by the high 5- and 10-year survival rates observed over the past decade (approximately 90% and 80%, respectively), patients could live for many years with RIT [3].

With improvements in radiotherapy planning, many different fractionation schedules and techniques have been applied in clinical practice over the past decade, ranging from classical doses of 2 Gy to new standard daily moderate hypofractionations of 2.7–2.85 Gy [4], or more foreshortened treatment of 26 Gy in 5 consecutive fractions [5]. Accelerated partial-breast irradiation (APBI) is also accepted as an attractive treatment strategy and has been introduced into clinical practice, shortening the duration of treatment and the extent of the irradiated volume, however, the toxicity outcomes are not yet clear and variable between different studies [6–8].

In most previous studies and in current clinical practice, RITs are classified with common rating criteria, such as the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) scales. These assessments are subjectively carried out by physicians with visual inspections and palpation examinations. Although fast and simple, such qualitative assessments are limited to 4 or 5 discrete grades [9]. In addition, due to its inherently subjective nature, the estimation of skin changes by different physicians is inevitably subjected to interobserver and intraobserver variability and may lead to a nonnegligible bias, particularly in multicenter studies [10].

To avoid this bias, many objective assessment tools have been introduced for monitoring skin changes more accurately, including ultrasound [11–13], reflectance spectrophotometry [14–16], thermal images [17], laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) [18] and other multiprobe devices which consists of various probes that can assess different skin parameters, including erythema, pigmentation, hydration; skin pH, skin temperature etc. [19–21]. Although these objective techniques demonstrate advantages in providing a more reliable quantification of RIT over subjective assessments, very rare tools have been routinely used in clinical practice or in comparison to RTOG or CTCAE scales successfully.

Furthermore, the dose, fractionation and dose per fraction are considered to impact the RT results. To directly compare the RITs resulting from different radiotherapy regimens, the biological equivalent dose (BED) can be used to more properly directly compare the RIT than a simple dose–response [22].

This study aimed to (1) determine whether our quantitative and multiprobe technique is capable of assessing late RIT in terms of skin color alterations (erythema, hyperpigmentation), induration and dehydration following different radiotherapy protocols; (2) establish an underlying BED-response relationship based on both objective measurements and subjective RIT evaluations; (3) determine whether the measures of our objective assessment tool is related to a subjective clinical assessment of late RIT obtained using the RTOG scale.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients were recruited to this study for RIT assessment with qualitative and quantitative examinations. Patients were recruited if accomplished the following inclusion criteria: age > 18 years old, treatment with unilateral breast radiotherapy, follow-up > 12 months, no antecedent irradiation to the breast or thorax, and acceptance of subjective and objective toxicity assessment. The exclusion criteria were: short follow-up (< 12 months), treatment with bilateral radiotherapy, prior breast or thoracic radiotherapy, pre-existing skin diseases, skin alterations caused by another treatment, refusal of allocated treatment, absence of toxicity assessments, and withdrawal of consent. Study was approved by Ethic Committee. All patients provided a written informed consent for inclusion in the study.

Radiotherapy and BED

Patient descriptions and fractionation schedules are presented in Table 1. Patients were treated by different sequential radiation protocols with comprehensive nodal plan according to the guideline or research trials performed in our department. To compare the RITs resulting from different fractionation regimens, the linear-quadratic (LQ) model was adopted to calculate the BED for each radiation schedule. An α/β ratio of 3 Gy for late toxicity of breast tissue was used to calculate the BED from different radiation schemes. Patients were grouped according to the radiation BED used, and a total of 7 groups (A–G) of patients were recruited into our study. Given the BEDs calculated above, different radiotherapy treatment schedules could be directly compared.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Group | Patients. no. (n, %) | Radiation regimens | WBI o PBI | BED# | Age Mean years (± SD) |

Interval time* Mean years (± SD) |

Chemotherapy (n, %) | Hormonotherapy (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 25 (12.6) | 30 Gy/5 Fx | WBI | 78.4 | 81.8 (± 6.6) | 3.4 (± 1.4) | 6 (24.0) | 21 (84.0) |

| B | 28 (14.1) | 48 Gy/2 Fx | WBI | 79 | 58.2 (± 10.9) | 3.3 (± 1.9) | 17 (60.7) | 19 (67.9) |

| C | 40 (20.1) | 37.5 Gy/3.75 Fx (BID) | PBI | 82.9 | 66.6 (± 6.0) | 3.2 (± 1.9) | 2 (5.0) | 40 (100) |

| D | 23 (11.6 | 48 Gy/2 Fx + 10 Gy boost | WBI | 95.4 | 66.1 (± 8.8) | 3.0 (± 1.9) | 3 (13.0) | 21 (91.3) |

| E | 50 (25.1) | 40.05 Gy/2.67 Fx + 16.02 Gy boost | WBI | 104.2 | 63.7 (± 7.9) | 3.3 (± 0.6) | 24 (48.0) | 43 (86.0) |

| F | 11 (5.5) | 48 Gy/2 Fx + 20 Gy boost | WBI | 111.9 | 54.9 (± 12.6) | 3.3 (± 2.1) | 5 (45.5) | 8 (72.7) |

| G | 17 (8.5) | 37.5 Gy/6.25 Fx | WBI | 113.1 | 83.7 (± 6.6) | 9.1 (± 2.9) | 5 (29.4) | 16 (94.1) |

BED biologically equivalent doses, WBI whole-breast irradiation, PBI partial-breast irradiation

#BED of late toxicity (α/β = 3.1 Gy), *Interval time (years) between radiotherapy and toxicity assessment

Clinical toxicity assessment

Physicians subjectively evaluated the patients for late RIT using the RTOG scoring system. Late toxicity was assessed at least 12 months after finishing RT. The examinations were carried out by visual inspection and palpation of both breasts, and the results ranged from grade 0 (no reaction) to grade 4 (severe toxicity).

Objective quantitative toxicity assessment

A Multi Skin Test Center MC 750 B2 device (CK Electronic, GmbH; Cologne, Germany) was used to simultaneously detect RIT. This multifunctional device consists of various probes that assess four skin parameters for each patient: a mexameter probe for assessing erythema (redness) and hyperpigmentation, a suction cup probe for assessing elasticity (as the surrogate of fibrosis) and a corneometry probe for assessing skin hydration (the relative quantity amount of water on the breast skin). For whole-breast irradiation, measurements were obtained from 4 quadrants of each breast; for partial-breast irradiation, measurements were obtained from 4 separate points of irradiated breast areas (high-dose areas). The measurements separately in the irradiated breast and the corresponding symmetric regions in the nonirradiated breast (Fig. 1). The average toxicity values of all these 4 points of each breast with computerized processing reflect the overall characteristics of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. The entire process of assessing toxicity took approximately 5 min per patient. To exclude the bias of the individual skin quality on the toxicity result, we used the absolute difference in toxicity between the treated and untreated breasts to assess the outcomes (Δerythema, Δpigmentation, Δelasticity and Δhydration).

Fig. 1.

Study design and flow chart of participating patients. BED biological equivalent dose; RTOG Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. *Quantitative assessment of toxicity by Multi Skin Test Center: measurements were obtained from 4 quadrants of each breast, separately in the irradiated breast and the corresponding nonirradiated breast

The results of the objective assessments were also used to determine whether they are correlated with those of the subjective RTOG evaluations. Among them, skin RTOG toxicity scale was used to determine whether erythema and hyperpigmentation were related to subjective clinical assessment; subcutaneous tissue RTOG criteria was used to determine whether elasticity was correlated to physician-assessed toxicity grade.

Other RIT-related factors

To detect the other potential RIT-related factors, age, interval time between radiotherapy and toxicity measurement, chemotherapy and hormonal therapy were included in regression models. The variables were selected due to clinical relevance. Due to collinearity, those RT-related factors, such as boost, did not include in multivariate analysis.

Statistics

The BED and toxicity values are presented as the mean with standard deviation and medians with interquartile ranges. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference between radiated and nonirradiated breasts. A Spearman correlation coefficient and its significance test were used to identify the relationship between the subjective and objective assessment and determine whether RIT is associated with BED. The adjusted associations of radiation schemes and RTOG toxicity scores were studied by ordered logistic regression analysis. Multivariate median regression analysis was used to identify potential predictors of objectively evaluated toxicity: erythema, hyperpigmentation, elasticity and hydration. The statistical analysis was performed with Stata (version 15.1; College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 194 patients were recruited in this study. Radiation-related information and patient recruitment flow chart are shown in Fig. 1.

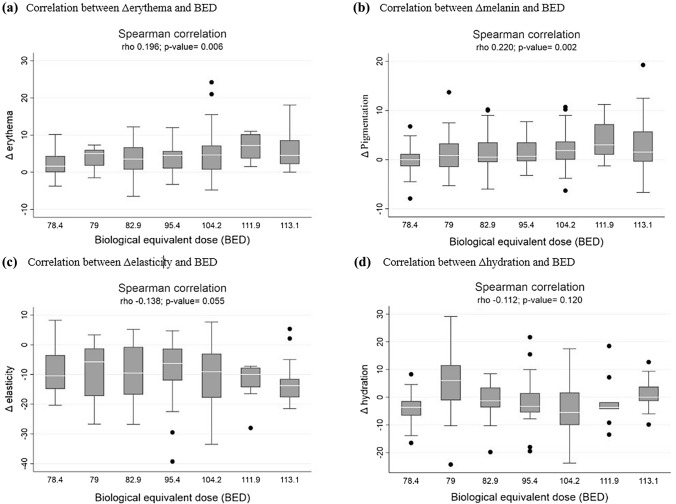

In the comparison of RITs between irradiated and nonirradiated breasts by multiprobe quantitative evaluation, as shown in Fig. 2, the treated breast showed significantly higher redness and hyperpigmentation values than the untreated breast: [median 21.0 (range 15.9–25.6) vs. 16.8 (range 12.9–20.5), p < 0.001; 4.5 (range 1.7–11.5) vs. 3.3 (range 1.3–8.4), p < 0.001, respectively]. The irradiated breast had a greater loss of elasticity than the nonirradiated breast: median 74.5 (range 64.5–80.9) vs. 83.3 (range 78.4–87.3), p < 0. 001. There was a similar but significantly different hydration index between the treated breast and untreated breast [median 35.0 (range 27.5–41.1 vs. 35.2 (range 28.8–42.8), p = 0.019]. The BED-RIT relationship based on objective measurements resulted in a significant correlation between the alteration in the erythema and hyperpigmentation values and the administered BED, as shown in Fig. 3. The Δerythema and Δpigmentation values increased gradually with increasing BED (r = 0.196, p = 0.006; r = 0.220, p = 0.002, respectively). A decreasing trend was also observed in the Δelasticity index with increasing BED; however, the correlation was not significant (p = 0.055).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of erythema (a), hyperpigmentation (b), elasticity (c) and hydration values (d) between irradiated and nonirradiated breasts

Fig. 3.

Biological equivalent dose (BED) dependence of Δerythema (a), Δpigmentation (b), Δelasticity (c) and Δhydration (d) in patients treated with different radiotherapy protocols. Δ = change of toxicity value between treated and untreated breast

Based on qualitative physician assessment, the RTOG late toxicity grade increased with increasing BED (mean BED: grade 0, 90.8; grade 1, 94.4; grade 2, 105.9, p < 0.001).

In comparison of the objective multiprobe evaluation and clinical assessment (RTOG scale), there was an increase in erythema and hyperpigmentation with increasing RTOG skin toxicity grade (p < 0.001, p = 0.016, respectively) and a decrease in the elasticity index with increasing RTOG subcutaneous toxicity grade (p = 0.005) (Fig. 4). Other potential toxicity-related factors, including age, interval time between radiotherapy and toxicity assessment, chemotherapy and hormonal therapy were not correlated with RIT.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of erythema (a), hyperpigmentation (b), elasticity (c) and hydration (d) with the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) late toxicity score

Discussion

Currently, different toxicity scales are used to assess RIT. Despite its speed and simplicity, the measurement of skin reactions usually depends on subjective visual and palpation-based tools. The RTOG and CTCAE scores, although valuable and widely used, have many drawbacks, particularly their lack of objective measures, which carries a considerable risk of intra- and interobserver variability [10]. Especially in multicenter clinical trials, this variability can lead to discrepancies in toxicity outcomes between different institutions and may limit their value as result measures. In addition, it is widely agreed that with the development of various radiotherapy technologies, quantitative assessments are needed to accurately detect the slight changes in RIT caused by these new technologies. Thus, several studies have attempted to measure RIT using quantitative methods (Table 2). Numerous techniques have been developed to objectively assess RIT via the measurement of associated skin characteristics, including ultrasound [11–13], spectrophotometry [14, 20], thermal images [17], LDF [18], mexameter probes [19, 21], viscoelasticity skin analyzers [23], corneometry [19–21] and multiprobe devices, etc. [19, 21, 24–26]. Yoshida et al. [11] tested the reliability of the ultrasonic assessment of radiation toxicity and found that the resulting ultrasound measurements of skin thickness changes were correlated with the RTOG scale score, suggesting that this technique can be used as a reliable method to assess RIT. Unlike our assessment, the use of ultrasound requires long-term training, which is not conducive to its application in clinical practice. Yoshida et al. evaluated radiation dermatitis by a spectrophotometer. CTCAE scales were found to be associated with a* and L* values, which are indicators of skin color alteration [13]. Saednia et al. [17] reported that thermal imaging markers could be used to monitor RIT. Patients with a CTCAE toxicity score > 2 demonstrated a significant increase in skin temperature. In the study by Huang et al. [19] a LDF was used to successfully measure acute radiation dermatitis, and the resulting quantitative values were shown to be correlated with the RTOG, CTCAE and WHO scores. This study also evaluated the pigmentation and skin hydration of the breast through a multiprobe device. Those clinical scoring criteria were moderate correlated to pigmentation; however, they were not found to be related to moisture analysis. Another study by González et al. [18] also used LDF to monitor acute radiation-induced dermatitis. The results showed that the LDF microcirculation index was correlated with the CTCAE scale score. These technologies have been used mainly in the evaluation of acute toxicity; only a small proportion of objective assessment techniques have been used to monitor late toxicity. Since some acute effects may resolve without chronic sequelae, our research as a measure of late toxicity, may be much better corelated with long-term patient quality of life. In our study, late RIT was assessed by a multiprobe device. We used the color (redness and darkness) of skin as an indicator of erythema and hyperpigmentation, skin elasticity as a surrogate for fibrosis and skin moisture content as an indicator of skin hydration. The treated breasts showed higher erythema and hyperpigmentation and lower elasticity and hydration than untreated breasts. Hydration did not change much after radiation, which maybe due to variability in skin care [3]. Subsequently, we compared clinical assessment measurements with our objective evaluations of RIT, and our results agree with those of the aforementioned studies. Higher erythema, hyperpigmentation and less elasticity are indicators of dermatitis and fibrosis, respectively, the most common signs of late toxicity [3], and were significantly correlated with the RTOG criteria. We suggest that our objective multiprobe measurement system may be used as a reliable clinical tool for assessing RIT. Furthermore, treated breasts with grade 0 RTOG toxicity demonstrated significantly higher values of erythema and hyperpigmentation and lower values of elasticity than the corresponding nonirradiated breasts. These findings indicate the presence of an underlying but invisible or nonpalpable skin change, suggesting that compared with clinical assessment alone, the multiprobe device can demonstrate more reliable changes of erythema, hyperpigmentation and elasticity and hydration. Therefore, our objective measurement tool can be used in the assessment of RIT as a research tool for use in clinical trials and may be more sensitive than the RTOG scale, as it can detect slight changes in RIT that are difficult to determine by visual or tactile examination.

Table 2.

Studies using quantitative toxicity assessments

| Study | n | Median follow-up | Radiation schemes | Biophysical parameters | Quantitative techniques | Qualitative assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warszawski et al. [12] | 29 |

n = 18: ≤ 3 months; n = 11: 30 months |

CF: 46–50 Gy/2 Gy | Skin thickness | Ultrasound | RTOG |

| Yoshida et al. [11] | 26 |

n = 8: < 6 months; n = 18: ≥ 6 months |

CF: 50.0–50.4 Gy/1.8–2.0 Gy | Skin thickness; hypodermal surface; glandular tissue | Ultrasound | RTOG |

| Landoni et al. [13] | 89 | 20.5 months | HF: 34 Gy/10 Fx/3.4 Gy | Skin thickness | Ultrasound | CTCAE |

| Wengstrom et al. [16] | 53 |

Acute toxicity (follow-up: N/R) |

CF: 50 Gy/2 Gy | Erythema; pigmentation |

Spectrophotometer; Measure digital images (Camera) |

RTOG |

| Schmeel et al. [14] |

70 in CF; 70 in HF |

6 weeks |

CF: 50 Gy/25 Fx; HF: 40.05 Gy/15 Fx |

Erythema; pigmentation | Spectrophotometer | CTCAE |

| Yamazaki et al. [15] |

46 in CF; 26 in HF |

12 months |

CF: 50 Gy/25 Fx; HF: 42.56 Gy/16 Fx |

Color alteration | Spectrophotometer | CTCAE |

| Yoshida et al. [20] | 118 |

12 months; subgroup (n = 28): 5 years |

CF: 48.4–50 Gy/22–25 Fx | Color alteration; skin moisture | Spectrophotometer; Corneometer | CTCAE |

| Saednia et al. [17] | 90 | During RT | HF: 42.50 Gy/16 fx | Skin temperature (Dermatitis) | Thermal imaging device | CTCAE |

| Sanchis et al. [18] | 63 | 3 months | HF: 40 Gy/15 Fx/2.67 Gy | Blood flow (Dermatitis) | LDF | CTCAE |

| Huang et al. [19] | 101 | Last day of RT | CF: 50.0–50.4 Gy/1.8–2.0 Gy | Blood flow; pigmentation; hydration; skin pH | LDF; Multi Skin Test Center MC900; Corneometer; Skin pH meter | RTOG; CTCAE; WHO |

| Sekine et al. [21] | 43 | 1 year | CF: 50 Gy/25 Fx; | Erythema, pigmentation; hydration; skin temperature | Multi-Display Device MDD4; (Corneometer; Tewameter; Mexameter); thermometer | CTCAE |

| Nuutinen et al. [24] | 21 |

5 weeks; subgroup (n = 14): 2 years |

CF: 50 Gy/25 Fx; | Dielectric constant (Erythema; fibrosis) | Dielectric constant | |

| Shumway et al. [25] | 80 | 10 weeks | Total radiation dose: < 40 Gy-66 Gy | Erythema; pigmentation; desquamation | Photographs | Photonumeric scale; CTCAE |

CF conventional fractionation, HF hypofractionation, RTOG Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, CTCAE common terminology criteria for adverse events, RT radiotherapy, LDF laser Doppler flowmetry

To compare the RIT following different radiotherapy regimen protocols and design novel radiotherapy schedules in clinical trials, the BED was calculated for different fractionation schemes [6, 7, 22, 27]. In our study, patients were grouped according to the radiation-BED used; since the differences in RIT may be relatively small, this task is not straightforward, and a highly accurate and sensitive assessment tool was required. Therefore, we used the multiprobe device to objectively and quantitatively investigate the underlying relationship between BED and RIT, and the subjective RTOG score was also used to assess toxicity. The results of these objective and subjective methods allowed us to determine the impact of BED on RIT. Regarding the objective assessment, the increase Δerythema and Δpigmentation were correlated with an increase in the delivered BED. Additionally, a decreasing trend was also observed in the Δelasticity index with increasing BED. In terms of the subjective assessment, an increase in the BED resulted in a higher RTOG toxicity grade. Therefore, based on the results of the objective and subjective assessments, we conclude that a lower BED can result in fewer RIT outcomes. This finding has also been confirmed in other clinical trials. Late toxicities were less common in radiation arms with lower BEDs than in those with higher BEDs [4, 28]. This BED-RIT relationship may allow us to make risk–benefit decisions on radiation schedules based on tumor control and possible toxicities. In addition, these results confirm the sensitivity and accuracy of the multiprobe device, which allowed us to detect slight changes in RIT in relation to minor alterations in the radiotherapy schemes used. In future work, this objective assessment may also be used as a monitoring tool to evaluate toxicity resulting from new radiation technologies.

There are several novel radiation schedules that can reduce hospital visits. The use of the FAST-Forward radiation regimen has rapidly increased for selected low-risk patients [5]. This low-BED radiation regimen (BED = 69.1 α/β = 3.1 Gy) may result in a lower possibility of developing RIT according to our RIT-BED relationship. The COVID-19 pandemic has promoted the adoption of new evidence-based schedules [29], which, in turn, has prompted us to compare different radiation regimens based on the establishment of a more accurate and sensitive evaluation system. Given the accuracy of our objective assessment, the risk and benefits of different treatment schedules can be discussed, facilitating the sharing of decision-making with patients.

Our objective assessment technique offers several advantages. First, the assessment is fast, straightforward, and noninvasive, and the healthcare workers responsible for operating the device only need minimal training. In contrast, some objective assessment techniques, such as ultrasonography, require longer training periods. Second, it can facilitate the detection of slight changes in RIT that are difficult to determine by visual inspections and palpation measurements. Third, this technique can be used in multicenter clinical trials to avoid potential intra- and inter-evaluator biases while facilitating researchers in comparing their results from those of other members of the scientific community. Fourth, given the continuous innovations in several modern radiotherapy techniques (IMRT, etc.) and the increasing number of different radiotherapy regimens (intraoperative radiotherapy, etc.), a continuous and objective scale allows the accurate detection of the development of RIT to improve the effect of new radiotherapy approaches.

A possible limitation of our study may lie in the potential differences in RIT at each time interval. However, in our study, multivariable regression analyses were performed to identify the influence of the interval time factor in both the subjective and objective assessments, and no association was found between RIT and interval time for either radiotherapy or toxicity assessment. In addition, the absence of skin care, as well as individual phenotype, genotype and molecular profiles, may also be considered RIT-related factors [30], but we did not include them in this study. Indeed, among all searched studies, no single factor was shown to be significant, and in certain circumstances, the opposite conclusions were drawn. We expect our sensitive objective assessment tool to provide further clinical evidence and to be used to determine the individual predisposing factors of RIT.

To the best of our knowledge, our series is the largest study to assess late RIT (erythema, hyperpigmentation, elasticity and hydration) using objective and quantitative tool. Moreover, this study also analyzed the BED-RIT relationship using both subjective and objective assessments.

Conclusions

We found that the Multi Skin Test Center is a noninvasive, useful and sensitive tool for quantitatively monitoring RIT in patients undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. The toxicity results measured by this objective assessment are significantly related to the subjective RTOG toxicity score. A higher BED is associated with the development of more severe toxicity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Supplementary material figure a: Example of a measure in a patient with a probe (JPG 866 KB)

Supplementary file2 Supplementary material figure b: Multi-probe device Multi Skin Test Center MC750 (JPG 713 KB)

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation. Conceptualization: YH, XS and MA; Methodology: YH, XS, MA, NR, JD, and PP; Formal analysis and investigation: XD and YH; Writing—original draft preparation: YH; Writing—review and editing: XS, MA, NR, XD, MC, PF, IM, AR, AM and FL. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by our institutional review ethics board and is in accordance to ethical standards of 1964 Helsinki Declaration for medical research.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yee C, Wang K, Asthana R, Drost L, Lam H, Lee J, et al. Radiation-induced skin toxicity in breast cancer patients: a systematic review of randomized trials. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(5):e825–e840. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haviland JS, Owen JR, Dewar JA, Agrawal R, Barrett J, Barett-Lee PJ, et al. The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) trials of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: 10-year follow-up results of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(11):1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray Brunt A, Haviland JS, Wheatley DA, Sydenham MA, Alhasso A, Bloomfield DJ, et al. Hypofractionated breast radiotherapy for 1 week versus 3 weeks (FAST-Forward): 5-year efficacy and late normal tissue effects results from a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1613–1626. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30932-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coles CE, Griffin CL, Kirby AM, Titley J, Agrawal RK, Alhasso A, et al. Partial-breast radiotherapy after breast conservation surgery for patients with early breast cancer (UK IMPORT LOW trial): 5-year results from a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10099):1048–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polgár C, Ott OJ, Hildebrandt G, Kauer-Dorner D, Knauerhase H, Major T, et al. Late side-effects and cosmetic results of accelerated partial breast irradiation with interstitial brachytherapy versus whole-breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery for low-risk invasive and in-situ carcinoma of the female breast: 5-year results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(2):259–268. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez N, Sanz X, Dengra J, Foro P, Membrive I, Reig A, et al. Five-year outcomes, cosmesis, and toxicity with 3-dimensional conformal external beam radiation therapy to deliver accelerated partial breast irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87(5):1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox JD, Stetz JA, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Andrade Fuzissaki M, Paiva CE, de Oliveira Gozzo T, de Almeida Maia M, Canto PPL, de Paiva Maia YC. Is there agreement between evaluators that used two scoring systems to measure acute radiation dermatitis? Medicine. 2019;98(15):e14917. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida EJ, Chen H, Torres M, Andic F, Liu HY, Chen Z, et al. Reliability of quantitative ultrasonic assessment of normal-tissue toxicity in breast cancer radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(2):724–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warszawski A, Röttinger EM, Vogel R, Warszawski N. 20 MHz ultrasonic imaging for quantitative assessment and documentation of early and late postradiation skin reactions in breast cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 1998;47(3):241–247. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landoni V, Giordano C, Marsella A, Saracino B, Petrongari M, Ferraro A, et al. Evidence from a breast cancer hypofractionated schedule: late skin toxicity assessed by ultrasound. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmeel LC, Koch D, Schmeel FC, Röhner F, Schoroth F, Bücheler BM, et al. Acute radiation-induced skin toxicity in hypofractionated vs conventional whole-breast irradiation: an objective, randomized multicenter assessment using spectrophotometry. Radiother Oncol. 2020;146:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamazaki H, Takenaka T, Aibe N, Suzuki G, Yoshida K, Nakamura S, et al. Comparison of radiation dermatitis between hypofractionated and conventionally fractionated postoperative radiotherapy: objective, longitudinal assessment of skin color. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18521-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wengström Y, Forsberg C, Näslund I, Bergh J. Quantitative assessment of skin erythema due to radiotherapy—evaluation of different measurements. Radiother Oncol. 2004;72(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saednia K, Tabbarah S, Lagree A, Wu T, Klein J, García E, et al. Quantitative thermal imaging biomarkers to detect acute skin toxicity from breast radiation therapy using supervised machine learning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(5):1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González-Sanchís A, Vicedo-González A, Brualla-González L, Gordo-Partearoyo JC, Iñigo-Valdenebro R, Sánchez-Carazo J, et al. Looking for complementary alternatives to CTCAE for skin toxicity in radiotherapy: quantitative determinations. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(10):892–897. doi: 10.1007/s12094-014-1163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CJ, Hou MF, Luo KH, Wei SY, Huang MY, Su SJ, et al. RTOG, CTCAE and WHO criteria for acute radiation dermatitis correlate with cutaneous blood flow measurements. Breast. 2015;24(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida K, Yamazaki H, Takenaka T, Tanaka E, Kotsuma T, Fujita Y, et al. Objective assessment of dermatitis following post-operative radiotherapy in patients with breast cancer treated with breast-conserving treatment. Strahlentherapie und Onkol. 2010;186(11):621–629. doi: 10.1007/s00066-010-2134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekine H, Kijima Y, Kobayashi M, Itami J, Takahashi K, Igaki H, et al. Non-invasive quantitative measures of qualitative grading effectiveness as the indices of acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer. 2020;27(5):861–870. doi: 10.1007/s12282-020-01082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plataniotis GA, Dale RG. Biologically effective dose-response relationship for breast cancer treated by conservative surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(2):512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorodetsky R, Lotan C, Piggot K, Pierce LJ, Polyansky I, Dische S, et al. Late effects of dose fractionation on the mechanical properties of breast skin following post-lumpectomy radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45(4):893–900. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuutinen J, Lahtinen T, Turunen M, Alanen E, Tenhunen M, Ursenius T, et al. A dielectric method for measuring early and late reactions in irradiated human skin. Radiother Oncol. 1998;47(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00234-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shumway D, Kapdia N, Walker E, Griffith KA, Do TT, Feng M, et al. Development of an illustrated scale for acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021;11(3):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Sanz J, Rodríguez N, Foro P, Reig A, Membrive I, et al. Effects of radiation on toxicity, complications, revision surgery and aesthetic outcomes in breast reconstruction: An argument about timing and techniques. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2021.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barendsen GW. Dose fractionation, dose rate and iso-effect relationships for normal tissue responses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982;8(11):1981–1997. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(82)90459-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunt AM, Haviland JS, Sydenham M, Agrawal RK, Algurafi H, Alhasso A, et al. Ten-year results of FAST: A randomized controlled trial of 5-fraction whole-breast radiotherapy for early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(28):3261–3272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coles CE, Aristei C, Bliss J, Boersma L, Brunt AM, Chatterjee S, et al. International guidelines on radiation therapy for breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Oncol. 2020;32(5):279–281. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tucker SL, Turesson I, Thames HD. Evidence for individual differences in the radiosensitivity of human skin. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1783–1791. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90004-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Supplementary material figure a: Example of a measure in a patient with a probe (JPG 866 KB)

Supplementary file2 Supplementary material figure b: Multi-probe device Multi Skin Test Center MC750 (JPG 713 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.