Abstract

Objectives:

Due to overcrowding and limited critical care resources, critically ill patients in the emergency department (ED) may spend hours to days awaiting transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). In these patients, often termed “ICU boarders”, delayed ICU transfer is associated with poor outcomes. We implemented an ED-based, electronic ICU (eICU) monitoring system for ICU boarders. Our aim was to investigate the effect of this initiative on morbidity, mortality, and ICU utilization.

Design:

Single-center, retrospective cohort study

Setting:

Nonprofit, tertiary care, teaching hospital with greater than 100,000 ED visits per year.

Patients:

Emergency department patients with admission orders for the medical ICU (MICU) who spent more than 2 hours boarding in the ED after being accepted for admission to the MICU were included in the study.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

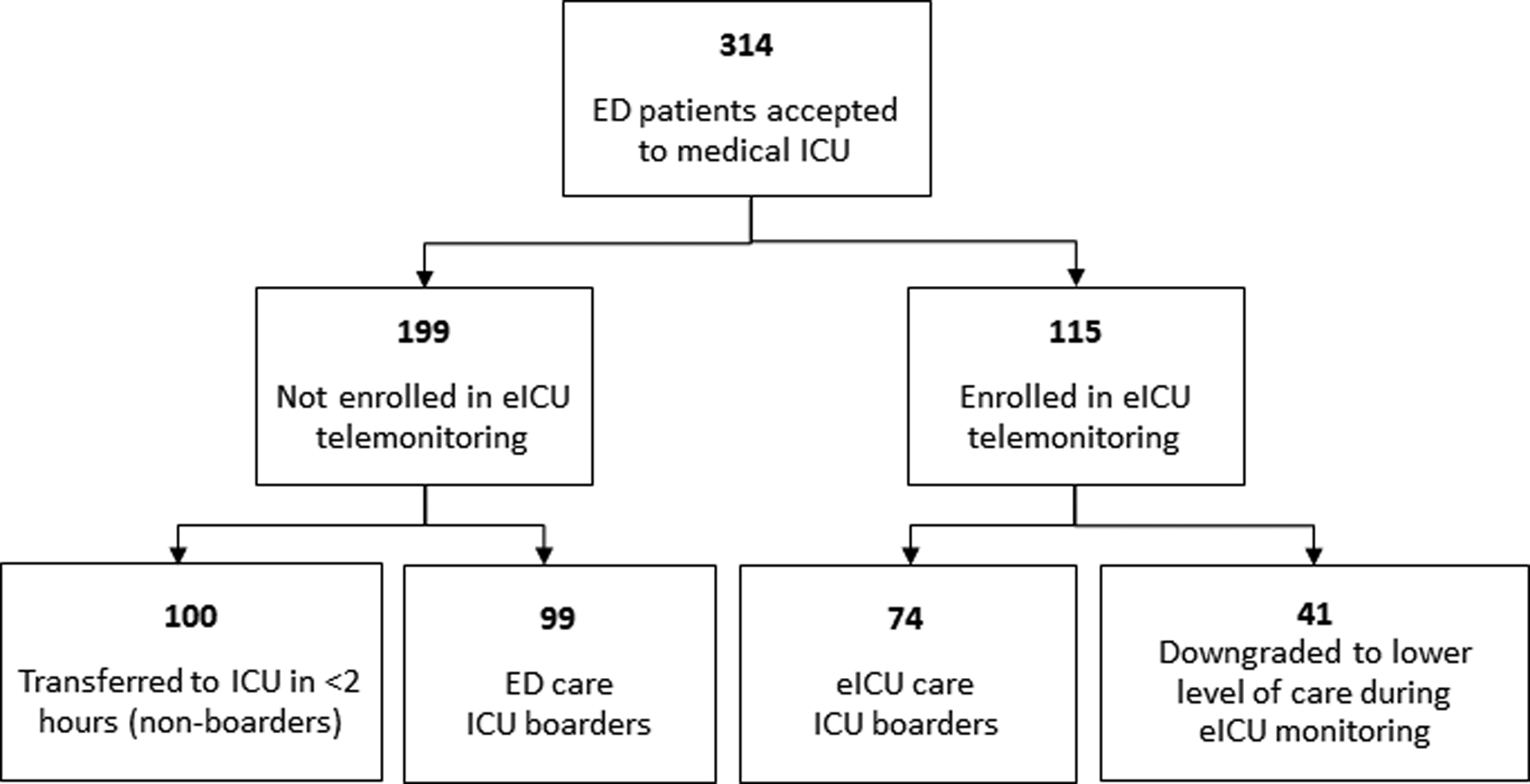

During the study period, a total of 314 patients were admitted to the MICU from the ED, 214 of whom were considered ICU boarders with a delay in MICU transfer over 2 hours. Of ICU boarders, 115 (53.7%) were enrolled in eICU telemonitoring (eICU care), and the rest received usual ED care (ED care). Age, mean illness severity (APACHE IVa scores), and admitting diagnoses did not differ significantly between ICU boarders receiving eICU care or ED care. Forty-one eICU care patients (36%) were ultimately transitioned to a less intensive level of care in lieu of ICU admission while still in the ED, compared with zero patients in the ED care group. Among all ICU boarders transferred to the ICU, in-hospital mortality was lower in the eICU care cohort as compared to the ED care cohort (5.4% vs. 20.0%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.20).

Conclusions:

In critically ill patients awaiting transfer from the ED to the MICU, eICU care was associated with decreased mortality and lower ICU resource utilization.

Keywords: intensive care units, telemedicine, bed occupancy, eICU, telehealth, patient safety

Introduction

Across the United States, demands for intensive care exceed available resources. Since 2000, intensive care unit (ICU) occupancy, volume of ICU admission requests, and rates of refused ICU admissions have increased dramatically (1–3). As a result, critically ill patients often spend hours or even days waiting in the Emergency Department (ED) for an ICU bed to become available (4). These patients, frequently referred to as “ICU boarders”, have markedly poorer outcomes, including increased mortality and hospital length of stay, compared to those immediately admitted to an ICU (5–8). This may be attributed to several factors, including lack of ED-based critical care expertise as well as limitations in resources. Compared with an ED, the ICU has a fixed number of patients, a predetermined physician and nurse to patient ratio, and specialized order sets for long-term critical care management(5–8). ED physicians and nurses managing critically ill patients must also continue to assess and treat new, sometimes also seriously ill, patientswhile their ICU counterparts may focus on just one or two patients (9–11). Additionally, ED physician orders, because of the outpatient status of the ED, are often entered as one-time medication doses. For example, if an antibiotic is given every 8 hours, ED physicians must reorder this medication for each dose, whereas the ICU order sets commonly accommodate this. Moreover, ICU specific order sets, including gastrointestinal prophylaxis and deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis are not always employed in the ED. The ED system is not designed for prolonged ICU-level critical care, and is a growing issue as ED length of stay, specifically for ICU boarders, continues to increase (12).

In recent years, there has been increased adoption of the electronic ICU (eICU), a form of telemedicine designed to provide closer patient monitoring in the ICU during off-hours such as overnight, when onsite physician and nursing care is less available (13–16). The eICU typically consists of a 24-hour support center, staffed with critical care nurses and physicians who have access to the electronic medical record, laboratory results, and radiology images. The staff then uses two-way video monitoring and smart alarms to monitor and treat patients in real time. Implementation of eICU technology in the ICU has improved outcomes such as mortality and hospital length of stay (LOS) in various settings (14, 17–21). However, it has not yet been studied if expanding the eICU concept outside of the ICU setting to the ED would result in similar outcomes. We therefore implemented an eICU program in the ED of a suburban teaching hospital, and then conducted a retrospective review of ICU utilization, as well as morbidity and mortality of ICU boarders eligible for eICU monitoring.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This was a retrospective cohort study performed at a tertiary care suburban teaching hospital and Level I trauma center with more than 100,000 ED visits per year and a 40% admission rate. The MICU included 24 beds with in house intensivist coverage from 7a-7p. Medical residents covered the unit overnight, with intensivists available by phone.

Institutional Protocol

In 2015, we established an eICU system for patients admitted to the MICU but waiting for a MICU bed in the ED (ICU boarders). The other ICUs in the hospital (trauma, cardiovascular thoracic, and acute surgical heart units) were not included. This was because these clinicians were in house and highly active in managing their specialized subset of patients boarding in the ED. Telemonitoring carts were purchased to provide audiovisual monitoring of vital signs, lab and imaging results, and patient appearance by an off-site intensivist. Four ED rooms were equipped with these mobile eICU towers, which provided two-way communication. Once the patient was accepted for admission by a hospital intensivist, the patient status was changed to inpatient and the patient was assigned a virtual MICU bed number. The eICU intensivist team received sign out from the ED attending physician or hospital intensivist and eICU monitoring was initiated. The hospital intensivist was responsible for coordinating inpatient ICU orders with the bedside nurse and eICU intensivist, and ED physicians remained available for codes and emergent procedures. In addition, the eICU intensivist would provide the hospital intensivist with an update upon physical transfer of the patient from the ED to the ICU. Common ICU order sets were available to bedside ED nurses to assist them in initiating verbal orders from the hospital or eICU intensivist. During the time period of our study, there was no change in ED nurse to patient ratio with eICU care. However, the ED nurse could contact the eICU nurse or eICU intensivist at any time with questions, thereby increasing communication and care for that patient. In addition, the eICU nurse was involved in the ED to MICU nurse handoff, thereby bringing consistency and continuity of care. In our ED a PharmD commonly adds orders, and with the change in patient status to inpatient, these recurring orders could now be entered and co-signed by the hospital or eICU intensivist. ED physicians were instructed on how to use the eICU system and were encouraged, but not required, to use it. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to retrospectively collect all data included in this study. Due to the nature of the study, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the Institutional Review Board.

Patients and Case Definitions

Medical records from February 10, 2015 to June 10, 2015 were reviewed for patients admitted to the MICU from the ED. Patients with traumatic injuries or those admitted to the surgical ICU were excluded. Outcomes in ICU boarders receiving eICU telemonitoring (eICU care) were compared with those who received standard care (ED care). Patients were considered “boarded” in the ED if they waited more than 2 hours after admission decision to be transferred to the MICU. Patients were considered transitioned to a less intensive level of care if their MICU admission was cancelled and they were admitted from the ED to a step down, telemetry, or medicine floor.

Data Collected

Demographic data collected included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and income. Income was inferred from home ZIP code using 2016 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data in an approach which has been used to approximate socioeconomic status (Avis J Thomas, Am J Epidemiology 2006). Use of prehospital EMS services was noted. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IVa scores, indicative of patient illness severity, were recorded at time of admission and assignment of MICU bed (22). Major pre-existing medical conditions and active MICU diagnoses for that admission were recorded and grouped into organ systems according to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classification Software classifications (5). Our primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Other outcome data collected included hospital and ICU LOS, invasive mechanical ventilator use, cumulative days on invasive ventilator support (ventilator days), and boarding time (i.e. time from MICU admission acceptance to physical transfer from the ED).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata IC version 15.1. Demographic information was compared using the Mann Whitney U test for continuous measures and χ2 test for categorical measures. To address the non-randomized nature of this study, we used two models to adjust outcome comparisons between eICU and non-eICU patients. Primarily, a generalized linear regression model encompassing APACHE scores, age, BMI, mode of arrival, and sex was used to determine adjusted odds ratios (OR) for ventilator use and mortality and determine linear regression coefficients for boarding time, ventilation days, hospital length of stay, and ICU length of stay. Additionally, we used propensity score matching, an approach used to compare patients in opposite groups who have the most similar covariate-predicted outcome (i.e. propensity score). The propensity score model encompassed age, APACHE scores, sex, and mode of arrival and matched each patient to two “nearest neighbors” in the opposite group. To ensure tight matching of patients, a caliper limit was set equal to 20% of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score (Austin, PC Pharm Stat 2011).

Results

A total of 314 patients met the criteria of MICU admission from the ED, 214 of whom were considered ICU boarders. Of ICU boarders, 115 (53.5%) were enrolled in eICU telemonitoring. Forty-one of these eICU care patients (36%) were transitioned to a less intensive level of care while in the ED, compared with zero patients in the ED care cohort. Figure 1 describes the flow of patients through this study. Patient characteristics and outcomes for the 173 ICU boarders eventually transferred to the ICU (eICU care, n=74; ED care, n=99) were analyzed. Demographic information and illness information for these patients is described in Table 1. Age, income, mean illness severity (APACHE scores), and admitting diagnoses did not significantly differ between patients receiving eICU care versus ED care. However, eICU patients were more likely to be male (54% vs 38%, Pearson’s chi-squared, P=0.04). There was a trend of eICU patients being more likely to arrive via emergency medical services (EMS) as well as having a higher BMI. These potential confounders were included in models for adjusted analyses.

Figure 1.

Flowchart indicating patient selection for this study. ED = emergency department, eICU = electronic ICU.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics, pre-existing conditions, and admitting conditions

| Demographics | eICU care (n=74) | ED care (n=99) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 61.6 (17.3) | 64.9 (17.3) | 0.21 |

| Male, n (%) | 40 (54) | 38 (38) | 0.040 |

| APACHE, mean (SD) | 72.1 (28.7) | 77.8 (33.3) | 0.24 |

| EMS arrival, n (%) | 44 (59) | 44 (44) | 0.051 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 32.1 (11.5) | 29.1 (8.7) | 0.056 |

| Income, mean (SD) | 34820 (9706) | 34275 (9866) | 0.72 |

| Pre-Existing Conditionsa | |||

| Infectious, n (%) | 7 (9.5) | 5 (5.1) | 0.26 |

| Digestive, n (%) | 7 (9.5) | 6 (6.1) | 0.40 |

| Injury or Poisoning, n (%) | 3 (4.1) | 4 (4) | 1.00 |

| Circulatory, n (%) | 55 (74.3) | 61 (61.6) | 0.079 |

| Endocrine, n (%) | 37 (50) | 37 (37.4) | 0.098 |

| Mental Illness, n (%) | 10 (13.5) | 14 (14.1) | 0.91 |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 9 (12.2) | 8 (8.1) | 0.38 |

| Neoplasms, n (%) | 15 (20.3) | 22 (22.2) | 0.76 |

| Nervous system, n (%) | 10 (13.5) | 16 (16.2) | 0.63 |

| Respiratory, n (%) | 40 (54.1) | 51 (51.5) | 0.74 |

| Blood, n (%) | 9 (12.2) | 9 (9.1) | 0.52 |

| Admitting Conditiona | |||

| Infectious, n (%) | 18 (24.3) | 37 (37.4) | 0.069 |

| Digestive, n (%) | 6 (8.1) | 8 (8.1) | 0.99 |

| Injury or Poisoning, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Circulatory, n (%) | 9 (12.2) | 20 (20.2) | 0.16 |

| Endocrine, n (%) | 4 (5.4) | 10 (10.1) | 0.27 |

| Mental Illness, n (%) | 10 (13.5) | 11 (11.1) | 0.63 |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 8 (10.8) | 9 (9.1) | 0.71 |

| Neoplasms, n (%) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (2) | 0.12 |

| Nervous system, n (%) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2) | 0.74 |

| Respiratory, n (%) | 24 (32.4) | 26 (26.3) | 0.38 |

| Blood, n (%) | 3 (4.1) | 7 (7.1) | 0.40 |

Conditions/Diagnoses were determined using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classification Software groupings

Our primary outcome was in-hospital mortality in ICU boarders. Without adjustment, eICU care was associated with a 73% relative reduction in mortality (mortality 5.4% vs 20%, Table 2). Using two statistical approaches to adjust for covariates, mortality was significantly reduced in boarded patients who received eICU care (adjusted OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07–0.79; Table 3).

Table 2:

Unadjusted outcome data in boarded patients receiving eICU care or ED care.

| Outcomes | eICU care (n=74) | ED care (n=99) |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality, n (%) | 4 (5.4%) | 20 (20%) |

| Hospital LOS, d, median (IQR) | 6.8 (3.8, 9.1) | 7.0 (3.0, 12.0) |

| ICU LOS, d, median (IQR) | 2.9 (1.6, 5.2) | 2.6 (1.2, 4.8) |

| Ventilator Use, n (%) | 32 (43%) | 42 (42%) |

| Ventilation Days, median (IQR) | 4 (2, 6.5) | 4.5 (2, 9) |

| Boarding Time, h, median (IQR) | 8.7 (4.5, 16.5) | 4.2 (2.7, 5.9) |

Table 3:

Covariate-adjusted analyses of the effect of eICU on boarded patient outcomes

| Outcomes | Generalized Linear Model | Propensity Score Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | Risk Difference | 95% CI | P | |

| Mortality | 0.08 | [0.01, 0.51] | <0.01 | −0.15 | [−0.21. −0.00] | <0.01 |

| Ventilator Use | 1.27 | [0.53, 3.04] | 0.59 | 0.074 | [−0.09, 0.24] | 0.37 |

| Coefficient | 95% CI | P | Average Treatment Effecta | 95% CI | P | |

| Boarding Time (h) | 5.51 | [3.30, 7.73] | <0.01 | 7.57 | [5.77, 9.37] | <0.01 |

| Ventilation Days (d) | −3.70 | [−8.31, 0.92] | 0.12 | −1.26 | [−3.86, 1.34] | 0.34 |

| Hospital LOS (d) | −0.46 | [−3.36, 2.45] | 0.76 | −0.67 | [−2.39, 1.04] | 0.44 |

| ICU LOS (d) | 0.05 | [−0.26, 0.35] | 0.76 | 0.16 | [−0.04, 0.36] | 0.11 |

Average treatment effect indicates the effect of eICU exposure on the outcome when comparing propensity-score matched patients, reported in units measured (i.e. eICU care boarders had a 7.6 hour increase in boarding time vs. matched ED care boarders).

Other outcomes of interest included boarding time, hospital and ICU LOS, and ventilator use. Boarding time was substantially longer in the eICU care cohort versus the ED care cohort, with a 107% relative increase in boarding time (Table 2). For ICU boarders eventually transferred to the ICU, eICU care was not associated with differences in hospital or ICU LOS (Table 3). However, hospital LOS was lower in the eICU care cohort when including the forty-one eICU patients who were transitioned to a less intensive level of care during monitoring (median hospital LOS, 5.2 d vs 7.0 d; P<0.01). Frequency and duration of ventilator use were not different between ICU boarders receiving eICU care versus ED care. Of note, although not systematically recorded, based on reported patient safety events, hospital records from two years of eICU monitoring (time frame beyond that of this study) indicate that there were zero reports of medication errors, such as incorrect dosing, in the eICU program.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of ED patients awaiting transfer to the MICU, eICU telemonitoring was associated with decreased mortality and decreased rates of transfer to the MICU from the ED. These data suggest that telemonitoring of boarded ED patients, with potential for teleintervention by an eICU intensivist, may improve patient outcomes and decrease the use of ICU resources. Our findings are in line with other studies that suggest eICU provides high quality care when employed efficiently (13, 17–19, 23).To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study implementing eICU telemonitoring in patients boarding in the ED while waiting for a MICU bed. More broadly, this study supports the feasibility of telemonitoring ICU patients outside the ICU.

The primary question of our investigation was if eICU monitoring in the ED impacted mortality rates in ICU boarders. We observed a significant decrease in mortality in eICU care patients compared to standard ED treatment care patients (adjusted OR for in-hospital mortality, 0.2; risk-reduction in matched patients, 15%), despite similar age, income, APACHE scores, pre-existing conditions, and admitting diagnoses. Our findings are consistent with previous literature suggesting that care by specialized intensivists is an independent positive prognostic factor in ICU patients (24, 25).

A long wait time in the ED before transfer to the ICU has previously been identified as an independent risk factor for mortality (6–8). Interestingly, we noticed that eICU care patients enrolled in our study spent approximately twice as much time in the ED compared to patients in the standard ED care boarders group. From observation, this may have happened because ED attending physicians seemed more likely to participate in the eICU protocol if they anticipated a long boarding time. However, despite the longer boarding times for eICU patients, they still had substantially lower mortality. In exploratory analyses, we did not observe any correlation between length of boarding time and mortality in the eICU cohort. This lack of correlation between boarding time and mortality in the eICU care group suggests that intensivist telemonitoring diminishes the mortality risk associated with long boarding times. Further study of approaches to minimize the negative effects of boarding will be useful.

Although there was a significant decrease in mortality with the eICU care group versus the ED care group, there was not a significant difference in morbidity. In the cohort of boarders eventually transferred to the ICU, eICU care was not associated with significant differences in frequency or duration of ventilatory use compared to standard ED care.

We found the lack of any reported medication errors after implementation of eICU telemonitoring, representing non-inferiority in terms of medication safety, to be interesting. Although further study is needed into this topic, we feel that this may reflect a crucial technical and cultural shift in ownership of patient management to direct management of critically ill patients by an intensivist. In addition, transitioning the patient to a virtual inpatient MICU bed allowed access to inpatient ICU order sets and protocols that could be easily initiated, rather than the typical ED workflow, which required ED physicians to periodically renew one-time orders. For example, the ED pharmacist could now discuss directly with the eICU intensivist and assist with initiating appropriate medication dosing.

We did not detect a difference in hospital or ICU LOS in the eICU care versus ED care patients. However, 36% of eICU care patients admitted to the MICU were able to be transitioned to a less intensive level of care during ED-based eICU monitoring, compared to zero patientsin the ED care boarders cohort. Although eICU patients transitioned to a less intensive level of care weren’t analyzed for the purposes of this study, they did have lower hospital lengths of stay (median, 2.2 d), and did not require an ICU bed despite similar patient characteristics. Thus, over a third of the ICU-admitted patients assigned to eICU had substantially less healthcare utilization. It is unclear if these transitioned patients became more stable due to eICU interventions or simply the passage of time. However, without eICU or similar systems to facilitate additional evaluation of boarded patients, one could view this transitioning to a less intensive level of care as uncommon, given zero incidences of transition in our ED care cohort. One could speculate that the ability to transition more patients from ICU care could result in cost savings. Although systematic investigation must still be performed, such findings would be consistent with existing data suggesting that ICU telemedicine approaches improve margins by increasing case volume without compromising care quality (21, 26, 27).

In recent decades, healthcare information technology has altered the practice of medicine (28). Telemedicine has become particularly popular, with established utility in gap service coverage such as night shifts, critical care, and underserved settings (29). The recent trend to adapt telemedicine to the ICU has demonstrated clinical benefit and cost-savings in a variety of settings (14, 20, 21, 26). In addition, existing data suggest that mobile eICU carts may be a clinically efficacious and cost-effective resource for rapid response teams (30). Our report of successful eICU implementation for patients boarded in the ED suggests an additional use of this innovative care modality.

Our study has several important limitations. This was a single site retrospective cohort study, with usual limitations associated with this design. Sample size limits the power of this study to robustly analyze subgroups and, as such, larger studies should be encouraged. We addressed this limitation to the extent possible by adjusting outcome comparisons for confounding variables (e.g. ED diagnoses and pre-existing medical problems) using multiple statistical approaches. It is also a limitation that the exact timing of APACHE score calculation varied by time of admission to the MICU. Enrollment in eICU care was not random and was at the discretion of ED physicians, which may have been another confounding variable. Implementation of eICU care was part of an institutional protocol. Although no other significant changes were made to patient care during this enrollment period, there was a cultural shift about who was primarily responsible for ICU boarders (i.e. intensivist versus ED physician), and this may have been a confounding factor. Although our data are promising and consistent with the literature to date, future studies will be needed to conclusively address the impact of telemonitoring on patients awaiting ICU transfer.

Conclusion

In this single-center retrospective study of ED patients awaiting transfer to the MICU, eICU telemonitoring was associated with decreased mortality (adjusted OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06–0.70). Additionally, over one third of telemonitored patients were able to be transitioned to a less intensive level of care before transfer to the ICU, liberating limited ICU resources. Telemonitoring is an innovative solution to improve ICU utilization and outcomes in ICU patients boarding in the ED.

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Elise Lovell for her invaluable assistance with manuscript preparation and editing.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

Authors Rachel Kadar, Katherine Iannitelli and Adam Bonder received the Be the Change Grant award from the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) to support this initiative. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Seymour CW, Barnato AE, Kahn JM: Critical care bed growth in the United States. A comparison of regional and national trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015, 191(4):410–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullins PM, Goyal M, Pines JM: National growth in intensive care unit admissions from emergency departments in the United States from 2002 to 2009. Acad Emerg Med 2013, 20(5):479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpern NA, Pastores SM: Critical care medicine in the United States 2000–2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med 2010, 38(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathews KS, Durst MS, Vargas-Torres C, Olson AD, Mazumdar M, Richardson LD: Effect of Emergency Department and ICU Occupancy on Admission Decisions and Outcomes for Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stretch R, Della Penna N, Celi LA, Landon BE: Effect of Boarding on Mortality in ICUs. Crit Care Med 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, Baumann BM, Dellinger RP, group D-Es: Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007, 35(6):1477–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lott JP, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, Asch DA, Kramer AA, Kahn JM: Critical illness outcomes in specialty versus general intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 179(8):676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Qahtani S, Alsultan A, Haddad S, Alsaawi A, Alshehri M, Alsolamy S, Felebaman A, Tamim HM, Aljerian N, Al-Dawood A et al. : The association of duration of boarding in the emergency room and the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit. BMC Emerg Med 2017, 17(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yarmohammadian MH, Rezaei F, Haghshenas A, Tavakoli N: Overcrowding in emergency departments: A review of strategies to decrease future challenges. J Res Med Sci 2017, 22:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trzeciak S, Rivers EP: Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J 2003, 20(5):402–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derlet RW, Richards JR: Overcrowding in the nation’s emergency departments: complex causes and disturbing effects. Ann Emerg Med 2000, 35(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herring AA, Ginde AA, Fahimi J, Alter HJ, Maselli JH, Espinola JA, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA Jr., : Increasing critical care admissions from U.S. emergency departments, 2001–2009. Crit Care Med 2013, 41(5):1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celi LA, Hassan E, Marquardt C, Breslow M, Rosenfeld B: The eICU: it’s not just telemedicine. Crit Care Med 2001, 29(8 Suppl):N183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young LB, Chan PS, Lu X, Nallamothu BK, Sasson C, Cram PM: Impact of telemedicine intensive care unit coverage on patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2011, 171(6):498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lilly CM, Cody S, Zhao H, Landry K, Baker SP, McIlwaine J, Chandler MW, Irwin RS, University of Massachusetts Memorial Critical Care Operations G: Hospital mortality, length of stay, and preventable complications among critically ill patients before and after tele-ICU reengineering of critical care processes. JAMA 2011, 305(21):2175–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lilly CM, Thomas EJ: Tele-ICU: experience to date. J Intensive Care Med 2010, 25(1):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta S, Dewan S, Kaushal A, Seth A, Narula J, Varma A: eICU reduces mortality in STEMI patients in resource-limited areas. Glob Heart 2014, 9(4):425–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zawada ET Jr., Kapaska D, Herr P, Aaronson M, Bennett J, Hurley B, Bishop D, Dagher H, Kovaleski D, Melanson T et al. : Prognostic outcomes after the initiation of an electronic telemedicine intensive care unit (eICU) in a rural health system. S D Med 2006, 59(9):391–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leong JR, Sirio CA, Rotondi AJ: eICU program favorably affects clinical and economic outcomes. Crit Care 2005, 9(5):E22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willmitch B, Golembeski S, Kim SS, Nelson LD, Gidel L: Clinical outcomes after telemedicine intensive care unit implementation. Crit Care Med 2012, 40(2):450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslow MJ, Rosenfeld BA, Doerfler M, Burke G, Yates G, Stone DJ, Tomaszewicz P, Hochman R, Plocher DW: Effect of a multiple-site intensive care unit telemedicine program on clinical and economic outcomes: an alternative paradigm for intensivist staffing. Crit Care Med 2004, 32(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today’s critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2006, 34(5):1297–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfeld BA, Dorman T, Breslow MJ, Pronovost P, Jenckes M, Zhang N, Anderson G, Rubin H: Intensive care unit telemedicine: alternate paradigm for providing continuous intensivist care. Crit Care Med 2000, 28(12):3925–3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL: Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA 2002, 288(17):2151–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brilli RJ, Spevetz A, Branson RD, Campbell GM, Cohen H, Dasta JF, Harvey MA, Kelley MA, Kelly KM, Rudis MI et al. : Critical care delivery in the intensive care unit: defining clinical roles and the best practice model. Crit Care Med 2001, 29(10):2007–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilly CM, Motzkus C, Rincon T, Cody SE, Landry K, Irwin RS, Group UMMCCO: ICU Telemedicine Program Financial Outcomes. Chest 2017, 151(2):286–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruklitis RJ, Tracy JA, McCambridge MM: Clinical and financial considerations for implementing an ICU telemedicine program. Chest 2014, 145(6):1392–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blumenthal D, Glaser JP: Information technology comes to medicine. N Engl J Med 2007, 356(24):2527–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinstein RS, Lopez AM, Joseph BA, Erps KA, Holcomb M, Barker GP, Krupinski EA: Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am J Med 2014, 127(3):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pappas PA, Tirelli L, Shaffer J, Gettings S: Projecting Critical Care Beyond the ICU: An Analysis of Tele-ICU Support for Rapid Response Teams. Telemed J E Health 2016, 22(6):529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]