Highlights

-

•

Maternal VDBP concentrations may predict negative pregnancy outcomes.

-

•

A method using LC-IDMS was developed to quantify VDBP tryptic peptides in serum.

-

•

Reference values for VDBP were assigned to SRM® 1949 Frozen Human Prenatal Serum.

Abbreviations: VDBP, vitamin D binding protein; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; TFE, trifluoroethanol; TCEP, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; MRM, multiple reaction monitoring; LC-IDMS, liquid chromatography-isotope dilution mass spectrometry; LC-MS/MS, liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry; PARs, peak area ratios; CV, coefficient of variation; NIST, National Institute of Standards and Technology; SRM, Standard Reference Material®; AAA, amino acid analysis

Keywords: Vitamin D binding protein, GC-globulin, LC-MS/MS, Isotope-dilution, Quantification, Pregnancy, MRM

Abstract

Vitamin D plays a vital role in successful pregnancy outcomes for both the mother and fetus. Vitamin D is bound to vitamin D binding protein (VDBP) in blood and is carried to the liver, kidneys and other target tissues. Accurate measurements of the clinically measured metabolite of vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], depend on complete removal from the binding protein. It has been found that VDBP concentrations increase in maternal serum during pregnancy, obfuscating the accuracy of 25(OH)D concentration measurements in pregnant women. Additionally, measurements of VDBP concentrations during pregnancy have been performed using immunoassays, which suffer from variations due to differences in antibody epitopes, making clinical comparisons difficult. Quantification of VDBP is also of interest because changes in VDBP expression levels may indicate negative outcomes during pregnancy, such as preterm delivery and restricted fetal growth. To address the need for accurate measurement of VDBP during pregnancy, a method using liquid chromatography-isotope dilution mass spectrometry (LC-IDMS) was developed to quantify VDBP using isotopically labeled peptides as internal standards. This method was used to quantify VDBP in Standard Reference Material® (SRM) 1949 Frozen Human Prenatal Serum, which was prepared from separate serum pools of women who were not pregnant and women during each trimester of pregnancy. VDBP concentrations were found to be lowest in the serum pool from non-pregnant women and increased in each trimester. These data had good repeatability and were found to be suitable for reference value assignment of VDBP in SRM 1949.

1. Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency, defined by a 25(OH)D concentration <25 nmol/L to <75 nmol/L [1], [2], has been shown to be widespread among different populations around the world [3], [4], [5], [6]. Pregnant women have been found to be at a higher risk compared to the general population for vitamin D deficiency [4], [7], [8], which may result in poor outcomes for both the mother and fetus including recurrent pregnancy loss [9], preeclampsia [10], [11], [12], [13], gestational diabetes [14], [15], [16], and reduced fetal growth [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. Low vitamin D status during pregnancy and infancy may also influence early childhood health resulting in issues with bones [22], [23], [24], brain development [25], [26], [27], dental caries [28], [29], enamel defects [30], asthma [31], [32], [33], type 1 diabetes [34], [35], autism [36], [37], [38] and elevated blood pressure [39]. However, there is also contradictory data showing that vitamin D deficiency is not correlated with negative maternal or neonatal outcomes for several conditions [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45]. Therefore, the role of vitamin D in pregnancy is not well understood in many cases.

Between 90% and 95% of 25(OH)D, the clinically measured metabolite for vitamin D status, is bound to VDBP. Because release of 25(OH)D from VDBP is a key step in most measurements for vitamin D status, changes in VDBP concentration could affect recovery of 25(OH)D. Data has been published showing an increase in VDBP concentrations during pregnancy [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], leading to concerns about the accuracy of 25(OH)D measurements in pregnant women. Additionally, quantification of VDBP has generally been performed with different types of immunoassays, which suffer from variations due to differences in antibody epitopes [56], [57]. Consequently, it has been difficult to understand the relationship between VDBP and 25(OH)D concentrations in pregnancy. Similarly, studies attempting to correlate unbound 25(OH)D [free or bioavailable 25(OH)D] concentrations with particular health outcomes may be biased if the calculations of the concentrations are derived from inaccurate VDBP measurements. Finally, maternal VDBP concentrations may be an independent predictor of negative outcomes such as impending preterm delivery [58], [59], gestational diabetes [60], fetal growth restriction [61], and type 1 diabetes developing during childhood [62], [63], and unreliable measurements would undermine the predictive value of these relationships.

All of these factors point to the need for accurate VDBP measurements during pregnancy. As part of the goals of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements’ Vitamin D Standardization Program to develop vitamin D reference methods and materials [1], [64], [65], [66], [67], VDBP was investigated as a target analyte in human serum. While previous efforts were focused on developing a reliable quantification method for VDBP in human plasma [68], this work focuses on the development of a quantification method for a multi-level reference material using human serum. Standard Reference Material® (SRM) 1949 Frozen Human Prenatal Serum is a four-level material that was pooled from non-pregnant women and women during each trimester of pregnancy. This reference material was used to develop and evaluate a method using LC-IDMS for absolute quantification of VDBP during pregnancy. Although the SRM is comprised of pools and not individual samples, it is expected to provide some insight into historical observations about increases in VDBP during pregnancy.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

All human derived samples were approved for this work by the NIST Human Subjects Protection Office.

The following chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO): Trizma pre-set crystals at pH 8.3 (Tris), trifluoroethanol (TFE), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), iodoacetamide, hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was purchased from Millipore (Temecula, California). LC-MS grade solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) or B&J (Morristown, NJ). HPLC grade water from J.T. Baker (Allentown, PA) was used for preparing solutions used during tryptic digestion. Sequencing grade trypsin was from Promega (Madison, WI). Unlabeled and labeled peptides were purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ), EZBiolab (Carmel, IN) or Biomatik (Wilmington, DE). SRM 1949 Frozen Human Prenatal Serum was from NIST (Gaithersburg, MD).

2.2. Peptide calibrant preparation

TSALSAK and VLEPTLK were used for total VDBP quantification and their locations in the amino acid sequence are shown in the supplemental information (Figure S1). Peptides were chosen and handled according to published guidelines [69]. Labeled TSALSAK and VLEPTLK contained one Leu residue with 13C6 and 15N. The peptides were purchased with a purity >98% determined by the vendor using liquid chromatography separation and UV detection. Purity of the unlabeled and labeled peptides was verified by LC-MRM and found to be >99.9% from the peak areas measured. Amino acid sequences of the peptides were also verified using LC-MS/MS. All calibrants were prepared gravimetrically in low binding protein tubes (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). Peptides were prepared individually at 100 nmol/g in 50 mmol/L Tris buffer (pH 8.3). The absolute concentrations of the unlabeled peptide stock solutions were determined using acid hydrolysis and amino acid analysis (AAA) performed in triplicate as previously described [68]. A mixture of the peptides was then prepared in with 50 mmol/L Tris buffer for a final concentration of 1 nmol/g. Calibrants were prepared with a final concentration of 0.20 nmol/g of each labeled peptide and either (0.12, 0.16, 0.20, 0.24 or 0.28) nmol/g of each unlabeled peptide.

2.3. Tryptic digestion of SRM 1949

Three vials of SRM 1949 per level were selected randomly for analysis. Samples were prepared gravimetrically. The digestion procedure was adapted from the protocol provided with the Promega trypsin and is described below. The protein-denaturing mixture was prepared by adding 100 μL TFE, 44 μL of 50 mmol/L TCEP (adjusted to pH 8.0 using 5 mol/L NaOH), and 80 μL of 50 mmol/L Tris buffer. Samples were prepared with 11 μL of SRM 1949 in low binding tubes (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) and 11 μL of the denaturing solution. Two μL of 300 mmol/L iodoacetamide was added to each sample (25 mmol/L final concentration). Samples were vortexed and incubated in the dark for 45 min. Samples were diluted with the addition of Tris buffer so that the concentration of TFE was <5% by volume. Trypsin was prepared in 10 mmol/L acetic acid and (300, 350, 400, or 450) units was then added to each sample vial. Samples were digested at 37 °C for 19 h where the peptides used for LC-IDMS were found to have stable concentrations [68]. Digestions were stopped by adding 1.25 μL of a volumetric ratio of 50% trifluoroacetic acid (final concentration was 0.5% by volume). A 30 μL aliquot was removed from each digested sample and either (9.1, 12.9, 15.0, or 17.5) μL of the labeled peptide mixture was added to the non-pregnant, 1st trimester, 2nd trimester, or 3rd trimester samples, respectively. After removing the first aliquot of serum from each vial for digestion, two 300 μL aliquots were removed from each vial and placed into low binding tubes, which were then stored at −80 °C. These aliquots were used for subsequent digestions. For the third set of samples, a different lot of trypsin was used for the digestion. Samples were prepared and analyzed by LC-IDMS in triplicate, over the course of about one month. A previously characterized pooled human plasma sample was used as a control for the digestions [68].

2.4. LC-IDMS analysis of tryptic digests

Transitions for multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) and collision energies were calculated for each of the peptides using Skyline 1.4 (https://skyline.ms/project/home/software/Skyline/begin.view) and were further optimized in a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. The two transitions with the greatest intensity for each peptide were selected for the final method. LC-IDMS analyses of SRM 1949 digests were performed using a Discover BIO Wide C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3 μm, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and guard column of same packing material (2.1 mm × 2 cm, 3 μm). The column was heated to 40 ⁰C and coupled to an Agilent 6490 triple quadrupole (Santa Clara, CA). Instrument settings were as follows: gas temperature 150 °C, gas flow 15 L/min, nebulizer 25 psi, sheath gas temperature 200 °C, sheath gas flow 11 L/min, capillary 3500 V, and nozzle 300 V. Five μL of the calibrants and 3 μL of digested samples (~1 pmol of each) were injected in triplicate in random order. Peptides were eluted at 250 μL/min with the following gradient: 2% to 30% B over 40 min., 30% to 90% B over 5 min., 90% B to 2% B over 1 min, and 2% B for the last 20 min. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile.

2.5. Data analysis

Peak areas for the peptide MRM transitions were automatically integrated using the QQQ MassHunter Qualitative Analysis B.07.00 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and were further processed in Microsoft Excel. Calibration curves were plotted using the ratio of the unlabeled and labeled peptide masses versus the ratio of the instrument responses for the unlabeled and or labeled peptide calibrants. A linear fit was used in Excel to determine the slope, y-intercept and R2 values for the calibrants. Peptide concentrations were calculated from the instrument response of each transition and the linear equation derived from the calibration curves. For the peptides, an average concentration was calculated from the two transitions. The total VDBP concentration was then determined from the mean concentration of the peptides. Accuracy and precision of the data was considered to be acceptable for CVs < 15% [70], [71]. VDBP concentrations measured in μmol/kg were converted to mg/L using the equation C2 = C1 * M * 10−3 * d where C2 is the concentration in mg/L, C1 is the concentration in μmol/kg, M is the molecular mass, and d is the density (shown in Table S2). Density measurements were made at room temperature in duplicate on three vials from each level using an oscillation frequency density meter (DMA 35, Anton Parr). Peak area ratios (PARs) were also calculated for the two transitions of both the unlabeled and labeled peptides in the same LC-IDMS analysis [72]. The percent coefficient (% CV) was then calculated between the labeled and unlabeled PARs for each peptide.

2.6. Results

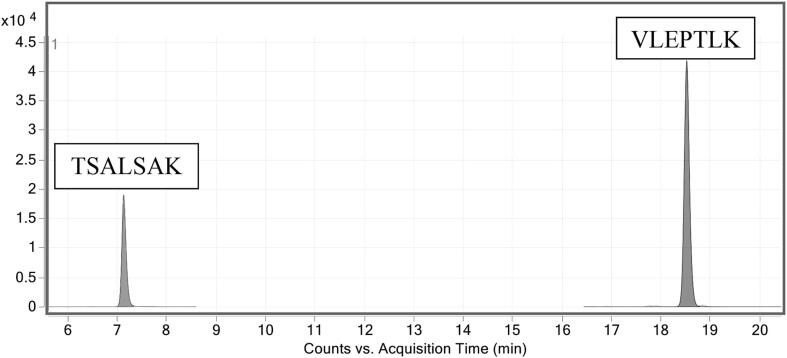

In this work, a method using LC-IDMS to quantify VDBP was developed and tested in serum pools from women during pregnancy. VDBP concentrations were determined in the four levels of SRM 1949 by digesting samples with trypsin and quantifying VDBP peptides TSALSAK and VLEPTLK (Figure S1). Two transitions for each peptide and the corresponding isotopically labeled peptide were measured (Table 1). A total ion chromatogram for the peptides in the non-pregnant sample is shown in Fig. 1 (see Supplemental Figure S3 for the other serum pools). These peptides have been previously shown to be specific for VDBP, give repeatable results and accurately reflect protein concentrations in pooled plasma [68]. However, further testing was performed to ensure equivalent results in serum.

Table 1.

Transitions used for LC-IDMS of VDBP peptides. Peptides are shared between the common isoforms. Labeled leucine (13C6, 15N) is designated as L* in the amino acid sequence.

| Peptide | Ion | Precursor m/z | Product m/z | Collision Energy (V) | Retention Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSALSAK | y5 | 339.2 | 489.3 | 1.7 | 7.3 |

| TSAL*SAK | y5 | 342.7 | 496.3 | 1.7 | 7.3 |

| TSALSAK | y6 | 339.2 | 576.4 | 3.7 | 7.3 |

| TSAL*SAK | y6 | 342.7 | 583.4 | 3.7 | 7.3 |

| VLEPTLK | y5 | 400.2 | 587.3 | 2.8 | 18.7 |

| VL*EPTLK | y5 | 403.8 | 587.3 | 2.8 | 18.7 |

| VLEPTLK | y6 | 400.2 | 700.4 | 4.8 | 18.7 |

| VL*EPTLK | y6 | 403.8 | 707.4 | 4.8 | 18.7 |

Fig. 1.

Total ion chromatograms of the two MRM transitions for TSALSAK and VLEPTLK collected during analyses of digested samples of SRM 1949. The non-pregnant serum pool is shown.

Because the accuracy of VDBP quantification is dependent upon the concentration of the peptides measured during LC-IDMS, the purity and concentration of the peptide calibrants was determined using several methods. The peptides were purchased with >98% purity (monitored by UV detection). Purity of the unlabeled and labeled peptides was also tested by LC-MRM and found to be >99.9%. Because not all impurities, such as water or salt adducts, are detected with these methods, amino acid analysis was used to determine the absolute concentration of the peptides in solution. Amino acid analysis (AAA) was performed on the individual peptide stock solutions just prior to mixing. Dilutions of the stock solutions were minimized following AAA and performed using low protein binding tubes to prevent peptide loss. The peptides used in this study to quantify VDBP are relatively hydrophilic and were not found to be lost with storage at −80 °C (CVs < 3% over 8 months) or during incubation in the autosampler at 7 °C over 4 days. Several peptides, which were more hydrophobic were found to be lost under these conditions and were excluded. Additionally, the instrument response and calibrant masses used in the calibration curves were calculated as ratios of the unlabeled and labeled peptides. This is expected to minimize any effects of peptide loss that might occur in the calibrants and samples due to handling or storage in the autosampler. Control digests were also performed using a previously characterized reference material (pooled human serum) to ensure stability of the samples and method accuracy.

The MRM transitions selected for the labeled and unlabeled peptides were further analyzed to determine if matrix interferences were present in the serum. The PARs between the two transitions (i.e., y5/y6) for either the labeled or unlabeled peptides were calculated for data measured in the same LC-IDMS analysis [72]. The mean % CVs between the 27 analyses for each peptide in different samples are shown in Table 2. For each peptide, the range of CVs shown in Table 2 are well below the 20% threshold suggested in previous work [68], [70], [72], indicating that interferences in the transitions are absent or at very low levels. The higher mean % CV for TSALSAK when compared to VLEPTLK may be due to the differences in retention time and/or peak areas (TSALSAK peak areas were approximately 1/3 of those measured for VLEPTLK). The lower standard deviation for TSALSAK shows that the % CV values were consistently higher.

Table 2.

Mean % CVs between the unlabeled and labeled peak area ratios for the VDBP peptides. Three vials of the SRM 1949 levels were prepared in triplicate and measured in triplicate by LC-IDMS. The standard deviation between the 27 LC-IDMS analyses for each sample are shown in parentheses.

| TSALSAK | VLEPTLK | |

|---|---|---|

| Calibrants | 4.12 (1.18) | 2.39 (1.45) |

| Non-pregnant | 4.11 (0.82) | 2.79 (1.90) |

| Trimester 1 | 4.41 (0.72) | 2.84 (2.17) |

| Trimester 2 | 4.20 (0.71) | 2.69 (2.10) |

| Trimester 3 | 4.14 (0.78) | 2.67 (1.76) |

During the progression of a normal pregnancy, the total protein concentration has been reported to decrease due to an increase in plasma volume [73], [74]. Variations in concentration have been measured for many individual proteins including albumin, the most abundant serum protein [47], [75], [76]. Some proteins, including VDBP, have been found to increase in concentration during pregnancy [46], [47], [77]. Therefore, to ensure that the tryptic digestion of VDBP in SRM 1949 was complete for all four levels measured, the amount of trypsin added to samples was varied from (300, 350, 400, and 450) units per sample. One unit of trypsin is defined by Promega as the amount of sequencing grade modified trypsin required to produce a Δ A253 of 0.001 per minute at 30 °C with the substrate Nα-benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester (BAEE) when digestions were performed in 50 mmol/L Tris buffer/1 mmol/L CaCl2 (pH 7.6). Only the non-pregnant and third trimester samples were analyzed because they are at the lowest and highest VDBP concentrations, respectively. Table 3 shows the concentrations measured for VDBP in the non-pregnant and third trimester samples and the units of trypsin added to each sample. The mean VDBP concentrations are 4.02 μmol/kg and 7.39 μmol/kg for the non-pregnant and trimester samples, respectively, with good repeatability between the samples with different amounts of trypsin (CVs ≤ 2.73%). Additionally, there was little variation in either peptide concentration (data not shown) used to calculate the total protein concentration across the range of trypsin activity tested (CVs ≤ 3.35%). Control digests of pooled human plasma showed similar results upon changing the amount of trypsin added (CV ≤ 2.31%) and were within the assigned NIST reference value (3.33 ± 0.33 μmol/kg) [78]. Therefore, using between 300 units and 450 units for tryptic digestion of SRM 1949 resulted in total VDBP concentrations with acceptable agreement. While the concentrations measured at different trypsin concentrations do not directly prove that a complete digestion has occurred in plasma or serum, the stable concentrations are a good indication that this is the case. This is also part of ongoing work to determine the accuracy of the VDBP concentration and assign a certified reference value for VDBP in this material.

Table 3.

Effect of trypsin amount on the concentration of VDBP in SRM 1949. The concentrations (μmol/kg) measured, following digestion with either (300, 350, 400 or 450) units of trypsin, are shown for the non-pregnant and third trimester samples. The VDBP concentrations were calculated from the mean of peptides TSALSAK and VLEPTLK.

| Trypsin Units | Non-pregnant | Third Trimester |

|---|---|---|

| 300 | 4.01 | 7.24 |

| 350 | 4.11 | 7.63 |

| 400 | 4.09 | 7.37 |

| 450 | 3.87 | 7.31 |

| AVG | 4.02 | 7.39 |

| % CV | 2.73 | 2.30 |

The total VDBP concentration was measured in the four levels of SRM 1949. Three vials per level were randomly selected and the proteins were denatured and digested with 350 units trypsin. Because of the limited availability of SRM 1949, two 300 μL aliquots were removed from each vial after preparing set 1 and stored at −80 °C until use for sets 2 and 3. Each sample was digested and analyzed in triplicate by LC-IDMS. Table 4 shows the mean VDBP concentrations calculated for the triplicate LC-IDMS runs for each sample. Because precision and accuracy were expected to be <15% CV [70], [71], the VDBP concentrations were found to have acceptable repeatability with ≤1.46% CV between the nine samples. The low % CV also indicates homogeneity of VDBP concentrations among the vials selected. Control digests of pooled human plasma were also prepared and analyzed with each set of SRM 1949 to ensure method accuracy. Concentrations of the VDBP in the control digest were within the assigned NIST reference value (3.33 ± 0.33 μmol/kg) [78].

Table 4.

Concentrations of VDBP in SRM 1949 (μmol/kg). The concentration shown for each vial is the mean of the triplicate LC-IDMS analyses. The mean value and % CV for each sample were determined from the 9 concentrations.

| Set 1 |

Set 2 |

Set 3 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vial | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Mean | %CV |

| Non-pregnant | 4.05 | 4.07 | 4.10 | 3.99 | 4.01 | 3.92 | 4.00 | 3.97 | 3.97 | 4.01 | 1.40 |

| Trimester 1 | 5.50 | 5.56 | 5.46 | 5.45 | 5.33 | 5.47 | 5.41 | 5.44 | 5.31 | 5.43 | 1.44 |

| Trimester 2 | 6.66 | 6.62 | 6.80 | 6.58 | 6.67 | 6.53 | 6.69 | 6.62 | 6.56 | 6.64 | 1.24 |

| Trimester 3 | 7.33 | 7.44 | 7.36 | 7.24 | 7.20 | 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.26 | 7.07 | 7.28 | 1.46 |

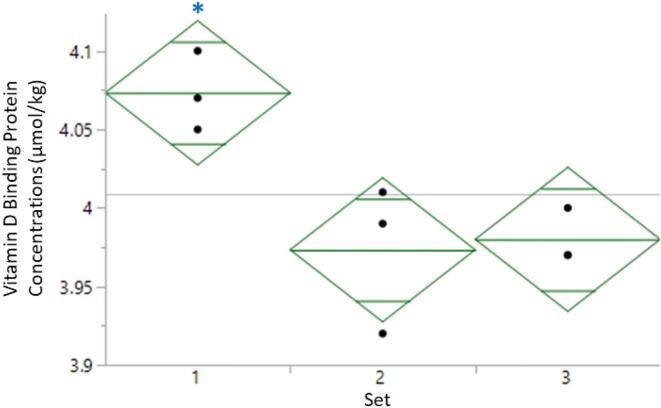

Because data sets 2 and 3 were collected following one freeze-thaw cycle and set 3 was prepared using a different lot of trypsin, a one-way ANOVA analysis was also performed to compare the sets (Fig. 2). While the sample size is small, the samples prepared in set 1 from the non-pregnant pool show a small, but statistically significant difference in concentration compared to sets 2 to 3 (median values of 4.07 μmol/kg, 3.97 μmol/kg and 3.98 μmol/kg, respectively; p = 0.0161). The decrease in concentration for sets 2 and 3, which was assessed by a post hoc Tukey test, is likely due to the freeze-thaw cycle. The other levels of SRM 1949 show a similar trend, but do not have statistically significant differences in concentrations among the data sets (Figure S4). However, more work is needed to determine if one or more freeze-thaw cycles is acceptable when quantifying VDBP in SRM 1949. The use of a different lot of trypsin did not result in a statistically significant change in concentration for any of the samples.

Fig. 2.

One-way ANOVA analysis of the serum pooled from non-pregnant women prepared in triplicate on three different days. Aliquots of the three vials were removed on day 1 and prepared after one freeze-thaw cycle for days 2 and 3. Diamonds indicate the 95% confidence interval. Mid green line is the mean of each set and the remaining lines define the quartiles. Grey line is the grand mean. The star indicates a significant difference according to a post hoc Tukey test.

Because clinical laboratories typically use volumetric measurements in reporting data, the data were converted from μmol to mg and kg to mL to allow interlaboratory comparisons and commutability testing of the material. The density of each sample was measured and used in the conversion (Table S2). Converting between moles and grams is also dependent upon the molecular masses of the protein isoforms present; therefore, LC-MRM and LC-MS/MS were used to search for the common isoform-specific peptides (Table 5). Peaks were observed in the extracted ion chromatograms for the three main isoforms of VDBP in all levels of SRM 1949 by LC-MRM (see Figure S5). Additionally, LC-MS/MS analysis on an Orbitrap Lumos Fusion was able to confirm the presence of the two most abundant isoforms, GC-1s and GC-1f (Figure S6), in all levels. The GC-2 peptide may not have been identified during LC-MS/MS due to low representation of this isoform in the pool abundance, poor fragmentation, or the formation of chimeric MS/MS spectra with a plasticizer having the same m/z as the double charged peptide ion (m/z 371.1), which elutes throughout the run. None of the glycosylated peptides were identified by LC-MS/MS, likely due to low concentration and poor fragmentation. Because all forms of protein appear to be present at some level in the samples and there is only a 1.3% relative difference between the highest and lowest molecular masses shown in Table 5, the mean molecular mass was used to calculate the concentrations. The range of molecular masses was also considered when calculating the uncertainty of the concentrations.

Table 5.

Molecular masses of the intact VDBP isoforms without or with glycosylation. Calculations were performed using the NIST Mass and Fragment Calculator v 1.3 [79], [80]. Masses are shown as average values corrected for amino acids originating from organic sources. Fourteen disulfide bonds are included in the calculations. Partial amino acid sequences are shown. The sequence of the O-linked glycosylation is -GalNAc-Gal-NANA and may be located on one T residue.

| Isoform | Partial Amino Acid Sequence | Molecular mass (g/mol) | Glycosylated (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-1f | LPDATPTELAK | 51187.9005 | 51844.4910 |

| GC-1s | LPEATPTELAK | 51201.9272 | 51858.5177 |

| GC-2 | LPDATPK | 51214.9692 | 51871.5597 |

The final values for the SRM 1949 samples are shown in Table 6 the mean concentrations calculated from values shown in Table 4 with units of either μmol/kg or mg/L (converted as described in Section 2.5). The error provided with each concentration is an expanded uncertainty calculated as U = kuc, where uc is the combined standard uncertainty and k is a coverage factor corresponding to approximately 95% confidence [81]. The uncertainty incorporates the standard error of the values measured with an additional component of uncertainty due to calibrant purity, consistent with the ISO Guide [82]. The uncertainties shown for the concentrations in mg/L also incorporate components related to estimation of the serum density and the molecular mass which was conservatively modeled as a uniform distribution with width equal to the difference between the highest and lowest molecular masses (shown in Table 5).

Table 6.

Reference values for VDBP in SRM 1949. The concentrations are the mean values measured for each vial (shown in Table 4) with units of μmol/kg or mg/L. The error in concentrations was calculated from the expanded uncertainty (U). The coverage factor (k), used in calculating the expanded uncertainty, corresponds with approximately 95% confidence.

| Concentration (mg/L) | Coverage Factor, k | Concentration (μmol/kg) | Coverage Factor, k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-pregnant | 211 ± 3 | 2.05 | 4.01 ± 0.05 | 2.23 |

| First Trimester | 287 ± 4 | 2.06 | 5.43 ± 0.06 | 2.23 |

| Second Trimester | 350 ± 4 | 2.03 | 6.64 ± 0.07 | 2.20 |

| Third Trimester | 384 ± 5 | 2.06 | 7.28 ± 0.08 | 2.23 |

3. Conclusions

A VDBP quantification method using LC-IDMS was developed and MRM transitions were found to have little interference from the serum matrix. The concentrations of VDBP in SRM 1949 were found to increase with gestational age in the pooled samples. Concentrations measured were (4.01, 5.43, 6.64, and 7.28) μmol/kg for the non-pregnant, first trimester, second trimester and third trimester samples, respectively. Converting the data results in concentrations of (211, 287, 350, and 384) mg/L for the non-pregnant, first trimester, second trimester and third trimester samples, respectively. This is an increase of 1.82-fold between the non-pregnant and third trimester samples. Previous studies also show an increase in VDBP during pregnancy with concentrations measured in the third trimester from 746.9 ± 161.1 mg/L [46] to 1254 ± 89 mg/L [53]. Only one study measured VDBP in all three trimesters [46]. However, data from the previous studies are difficult to compare to this work due to differences in donors and a lack of standardization between the different methods.

In the quantification of VDBP in SRM 1949, there was a small but statistically significant difference in concentration for the non-pregnant pool after one freeze-thaw cycle. This amount of measurement uncertainty was determined to be permissible due to the homogeneity among vials and repeatability of the measurements (CVs ≤ 1.46% for all 4 levels). However, more experiments need to be performed with a greater number of samples in order to determine the number of freeze-thaw cycles that are acceptable for this material. The VDBP concentrations measured in this work were found to be suitable for reference value assignment of VDBP in SRM 1949. Along with NIST SRM 1950 Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma, which also has a reference value for VDBP, these reference materials may be thus used to establish reference ranges in laboratories and to determine the suitability of assays for VDBP quantification during pregnancy. Future work will focus on determining the commutability of these VDBP reference materials. Overall, this LC-IDMS method development and application to serum samples provide further evidence of increasing VDBP concentrations throughout pregnancy and emphasize the importance of appropriately accounting for VDBP when clinically determining vitamin D status.

4. Disclaimer

Official contribution of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Not subject to copyright in the United States. Certain commercial equipment, instruments, software or materials are identified in this document. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that the products identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, United States, through an interagency agreement.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinms.2020.01.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sempos C.T., Vesper H.W., Phinney K.W., Thienpont L.M., Coates P.M. Vitamin D status as an international issue: national surveys and the problem of standardization. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 2012;243:32–40. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2012.681935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sempos C.T., Heijboer A.C., Bikle D.D., Bollerslev J., Bouillon R., Brannon P.M., DeLuca H.F., Jones G., Munns C.F., Bilezikian J.P., Giustina A., Binkley N. Vitamin D assays and the definition of hypovitaminosis D: results from the First International Conference on Controversies in Vitamin D. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018;84:2194–2207. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilger J., Friedel A., Herr R., Rausch T., Roos F., Wahl D.A., Pierroz D.D., Weber P., Hoffmann K. A systematic review of vitamin D status in populations worldwide. Br. J. Nutr. 2014;111:23–45. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017;18:153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cashman K.D., Dowling K.G., Skrabakova Z., Gonzalez-Gross M., Valtuena J., De Henauw S., Moreno L., Damsgaard C.T., Michaelsen K.F., Molgaard C., Jorde R., Grimnes G., Moschonis G., Mavrogianni C., Manios Y., Thamm M., Mensink G.B., Rabenberg M., Busch M.A., Cox L., Meadows S., Goldberg G., Prentice A., Dekker J.M., Nijpels G., Pilz S., Swart K.M., van Schoor N.M., Lips P., Eiriksdottir G., Gudnason V., Cotch M.F., Koskinen S., Lamberg-Allardt C., Durazo-Arvizu R.A., Sempos C.T., Kiely M. Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: pandemic? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016;103:1033–1044. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakhtoura M., Rahme M., Chamoun N., El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Vitamin D in the Middle East and North Africa. Bone Rep. 2018;8:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenmakers I., Pettifor J.M., Pena-Rosas J.P., Lamberg-Allardt C., Shaw N., Jones K.S., Lips P., Glorieux F.H., Bouillon R. Prevention and consequences of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant and lactating women and children: a symposium to prioritise vitamin D on the global agenda. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;164:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Websky K., Hasan A.A., Reichetzeder C., Tsuprykov O., Hocher B. Impact of vitamin D on pregnancy-related disorders and on offspring outcome. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018;180:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharif K., Sharif Y., Watad A., Yavne Y., Lichtbroun B., Bragazzi N.L., Amital H., Shoenfeld Y. Vitamin D, autoimmunity and recurrent pregnancy loss: more than an association. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018;80 doi: 10.1111/aji.12991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirzakhani H., Litonjua A.A., McElrath T.F., O'Connor G., Lee-Parritz A., Iverson R., Macones G., Strunk R.C., Bacharier L.B., Zeiger R., Hollis B.W., Handy D.E., Sharma A., Laranjo N., Carey V., Qiu W., Santolini M., Liu S., Chhabra D., Enquobahrie D.A., Williams M.A., Loscalzo J., Weiss S.T. Early pregnancy vitamin D status and risk of preeclampsia. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:4702–4715. doi: 10.1172/JCI89031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Y., Tai W., Xu P., Fu Z., Wang X., Long W., Guo X., Ji C., Zhang L., Zhang Y., Wen J. Association of maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with risk of preeclampsia: a nested case-control study and meta-analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;1–10 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1640675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pashapour S., Golmohammadlou S., Behroozi-Lak T., Ghasemnejad-Berenji H., Sadeghpour S., Ghasemnejad-Berenji M. Relationship between low maternal vitamin D status and the risk of severe preeclampsia: a case control study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;15:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benachi A., Baptiste A., Taieb J., Tsatsaris V., Guibourdenche J., Senat M.V., Haidar H., Jani J., Guizani M., Jouannic J.M., Haguet M.C., Winer N., Masson D., Courbebaisse M., Elie C., Souberbielle J.C. Relationship between vitamin D status in pregnancy and the risk for preeclampsia: a nested case-control study. Clin. Nutr. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold D.L., Enquobahrie D.A., Qiu C., Huang J., Grote N., VanderStoep A., Williams M.A. Early pregnancy maternal vitamin D concentrations and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2015;29:200–210. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y., Gong Y., Xue H., Xiong J., Cheng G. Vitamin D and gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review based on data free of Hawthorne effect. BJOG. 2018;125:784–793. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajput R., Vohra S., Nanda S., Rajput M. Severe 25(OH)vitamin-D deficiency: a risk factor for development of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019;13:985–987. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motamed S., Nikooyeh B., Kashanian M., Hollis B.W., Neyestani T.R. Efficacy of two different doses of oral vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers, and maternal and neonatal outcomes. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019 doi: 10.1111/mcn.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodnar L.M., Catov J.M., Zmuda J.M., Cooper M.E., Parrott M.S., Roberts J.M., Marazita M.L., Simhan H.N. Maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with small-for-gestational age births in white women. J. Nutr. 2010;140:999–1006. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.119636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y.H., Fu L., Hao J.H., Yu Z., Zhu P., Wang H., Xu Y.Y., Zhang C., Tao F.B., Xu D.X. Maternal vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy elevates the risks of small for gestational age and low birth weight infants in Chinese population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:1912–1919. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckhardt C.L., Gernand A.D., Roth D.E., Bodnar L.M. Maternal vitamin D status and infant anthropometry in a US multi-centre cohort study. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2015;42:215–222. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2014.954616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang K., He Y., Mu M., Liu K. Maternal vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy and low birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;1–7 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1623780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creo A.L., Thacher T.D., Pettifor J.M., Strand M.A., Fischer P.R. Nutritional rickets around the world: an update. Paediatr. Int. Child Health. 2017;37:84–98. doi: 10.1080/20469047.2016.1248170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zerofsky M., Ryder M., Bhatia S., Stephensen C.B., King J., Fung E.B. Effects of early vitamin D deficiency rickets on bone and dental health, growth and immunity. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016;12:898–907. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albertini F., Marquant E., Reynaud R., Lacroze V. Two cases of fractures in neonates associated with maternofetal vitamin D deficiency. Arch. Pediatr. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pet M.A., Brouwer-Brolsma E.M. the impact of maternal vitamin D status on offspring brain development and function: a systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2016;7:665–678. doi: 10.3945/an.115.010330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhamayanti M., Noviandhari A., Supriadi S., Judistiani R.T., Setiabudiawan B. Association of maternal vitamin D deficiency and infants' neurodevelopmental status: a cohort study on vitamin D and its impact during pregnancy and childhood in Indonesia. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jpc.14481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Specht I.O., Janbek J., Thorsteinsdottir F., Frederiksen P., Heitmann B.L. Neonatal vitamin D levels and cognitive ability in young adulthood. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almoudi M.M., Hussein A.S., Abu Hassan M.I., Schroth R.J. Dental caries and vitamin D status in children in Asia. Pediatr. Int. 2019;61:327–338. doi: 10.1111/ped.13801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singleton R., Day G., Thomas T., Schroth R., Klejka J., Lenaker D., Berner J. Association of maternal vitamin D deficiency with early childhood caries. J. Dent. Res. 2019;98:549–555. doi: 10.1177/0022034519834518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norrisgaard P.E., Haubek D., Kuhnisch J., Chawes B.L., Stokholm J., Bonnelykke K., Bisgaard H. Association of high-dose vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy with the risk of enamel defects in offspring: a 6-year follow-up of a randomized. Clinical Trial, JAMA Pediatr. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi D., Wang D., Meng Y., Chen J., Mu G., Chen W. Maternal vitamin D intake during pregnancy and risk of asthma and wheeze in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;1–7 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1611771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Litonjua A.A. Vitamin D and childhood asthma: causation and contribution to disease activity. Curr. Opin Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019;19:126–131. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W., Qin Z., Gao J., Jiang Z., Chai Y., Guan L., Ge Y., Chen Y. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and the risk of wheezing in offspring: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. J. Asthma. 2018;1–8 doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1536142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathieu C., Gysemans C., Giulietti A., Bouillon R. Vitamin D and diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1247–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miettinen M.E., Smart M.C., Kinnunen L., Harjutsalo V., Reinert-Hartwall L., Ylivinkka I., Surcel H.M., Lamberg-Allardt C., Hitman G.A., Tuomilehto J. Genetic determinants of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration during pregnancy and type 1 diabetes in the child. PLoS ONE. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alzghoul L., Al-Eitan L.N., Aladawi M., Odeh M., Abu Hantash O. The association between serum vitamin d3 levels and autism among jordanian boys. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04017-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arastoo A.A., Khojastehkia H., Rahimi Z., Khafaie M.A., Hosseini S.A., Mansouri M.T., Yosefyshad S., Abshirini M., Karimimalekabadi N., Cheraghi M. Evaluation of serum 25-Hydroxy vitamin D levels in children with autism Spectrum disorder. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018;44:150. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0587-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Ansary A., Cannell J.J., Bjorklund G., Bhat R.S., Al Dbass A.M., Alfawaz H.A., Chirumbolo S., Al-Ayadhi L. In the search for reliable biomarkers for the early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: the role of vitamin D. Metab. Brain Dis. 2018;33:917–931. doi: 10.1007/s11011-018-0199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.G. Wang, X. Liu, T.R. Bartell, C. Pearson, T.L. Cheng, X. Wang, Vitamin D Trajectories From Birth to Early Childhood and Elevated Systolic Blood Pressure During Childhood and Adolescence, Hypertension, Hypertensionaha (2019) 11913120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Roth D.E., Morris S.K., Zlotkin S., Gernand A.D., Ahmed T., Shanta S.S., Papp E., Korsiak J., Shi J., Islam M.M., Jahan I., Keya F.K., Willan A.R., Weksberg R., Mohsin M., Rahman Q.S., Shah P.S., Murphy K.E., Stimec J., Pell L.G., Qamar H., Al Mahmud A. Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy and lactation and infant growth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:535–546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez A., Garcia-Esteban R., Basterretxea M., Lertxundi A., Rodriguez-Bernal C., Iniguez C., Rodriguez-Dehli C., Tardon A., Espada M., Sunyer J., Morales E. Associations of maternal circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentration with pregnancy and birth outcomes. BJOG. 2015;122:1695–1704. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneuer F.J., Roberts C.L., Guilbert C., Simpson J.M., Algert C.S., Khambalia A.Z., Tasevski V., Ashton A.W., Morris J.M., Nassar N. Effects of maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in the first trimester on subsequent pregnancy outcomes in an Australian population. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;99:287–295. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.065672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Dominguez S.J., Tajada M., Chedraui P., Perez-Lopez F.R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Spanish studies regarding the association between maternal 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and perinatal outcomes. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2018;34:987–994. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1472761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flood-Nichols S.K., Tinnemore D., Huang R.R., Napolitano P.G., Ippolito D.L. Vitamin D deficiency in early pregnancy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sebastian A., Vijayaselvi R., Nandeibam Y., Natarajan M., Paul T.V., Antonisamy B., Mathews J.E. A case control study to evaluate the association between primary cesarean section for dystocia and vitamin D deficiency. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14029.6502. Qc05-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuprykov O., Buse C., Skoblo R., Haq A., Hocher B. Reference intervals for measured and calculated free 25-hydroxyvitamin D in normal pregnancy. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018;181:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J.Y., Lucey A.J., Horgan R., Kenny L.C., Kiely M. Impact of pregnancy on vitamin D status: a longitudinal study. Br. J. Nutr. 2014;112:1081–1087. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514001883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heijboer A.C., Blankenstein M.A., Kema I.P., Buijs M.M. Accuracy of 6 routine 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays: influence of vitamin D binding protein concentration. Clin. Chem. 2012;58:543–548. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.176545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barragry J.M., Corless D., Auton J., Carter N.D., Long R.G., Maxwell J.D., Switala S. Plasma vitamin D-binding globulin in vitamin D deficiency, pregnancy and chronic liver disease. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1978;87:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(78)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bikle D.D., Zolock D.T., Munson S. Differential response of duodenal epithelial cells to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 according to position on the villus: a comparison of calcium uptake, calcium-binding protein, and alkaline phosphatase activity. Endocrinology. 1984;115:2077–2084. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-6-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouillon R., Van Assche F.A., Van Baelen H., Heyns W., De Moor P. Influence of the vitamin D-binding protein on the serum concentration of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Significance of the free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 concentration. J. Clin. Invest. 1981;67:589–596. doi: 10.1172/JCI110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brannon P.M., Picciano M.F. Vitamin D in pregnancy and lactation in humans. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011;31:89–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haddad J.G., Jr., Walgate J. Radioimmunoassay of the binding protein for vitamin D and its metabolites in human serum: concentrations in normal subjects and patients with disorders of mineral homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 1976;58:1217–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI108575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ritchie L.D., Fung E.B., Halloran B.P., Turnlund J.R., Van Loan M.D., Cann C.E., King J.C. A longitudinal study of calcium homeostasis during human pregnancy and lactation and after resumption of menses. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998;67:693–701. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson S.G., Retallack R.W., Kent J.C., Worth G.K., Gutteridge D.H. Serum free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and the free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D index during a longitudinal study of human pregnancy and lactation. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 1990;32:613–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henderson C.M., Lutsey P.L., Misialek J.R., Laha T.J., Selvin E., Eckfeldt J.H., Hoofnagle A.N. Measurement by a novel LC-MS/MS methodology reveals similar serum concentrations of vitamin D-binding protein in blacks and whites. Clin. Chem. 2016;62:179–187. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.244541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoofnagle A.N., Eckfeldt J.H., Lutsey P.L. Vitamin D-binding protein concentrations quantified by mass spectrometry. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1480–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1502602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kook S.Y., Park K.H., Jang J.A., Kim Y.M., Park H., Jeon S.J. Vitamin D-binding protein in cervicovaginal fluid as a non-invasive predictor of intra-amniotic infection and impending preterm delivery in women with preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liong S., Di Quinzio M.K., Fleming G., Permezel M., Georgiou H.M. Is vitamin D binding protein a novel predictor of labour? PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y., Wang O., Li W., Ma L., Ping F., Chen L., Nie M. Variants in vitamin D binding protein gene are associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wookey A.F., Chollangi T., Yong H.E., Kalionis B., Brennecke S.P., Murthi P., Georgiou H.M. Placental vitamin D-binding protein expression in human idiopathic fetal growth restriction. J. Pregnancy. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/5120267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sorensen I.M., Joner G., Jenum P.A., Eskild A., Brunborg C., Torjesen P.A., Stene L.C. Vitamin D-binding protein and 25-hydroxyvitamin D during pregnancy in mothers whose children later developed type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2016;32:883–890. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tapia G., Marild K., Dahl S.R., Lund-Blix N.A., Viken M.K., Lie B.A., Njolstad P.R., Joner G., Skrivarhaug T., Cohen A.S., Stordal K., Stene L.C. Maternal and newborn vitamin D-binding protein, vitamin D levels, vitamin D receptor genotype, and childhood type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:553–559. doi: 10.2337/dc18-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wise S.A., Tai S.S., Burdette C.Q., Camara J.E., Bedner M., Lippa K.A., Nelson M.A., Nalin F., Phinney K.W., Sander L.C., Betz J.M., Sempos C.T., Coates P.M. Role of the national institute of standards and technology (NIST) in support of the vitamin D initiative of the national institutes of health office of dietary supplements. J. AOAC Int. 2017;100:1260–1276. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Binkley N., Sempos C.T. Standardizing vitamin D assays: the way forward. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29:1709–1714. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Binkley N., Dawson-Hughes B., Durazo-Arvizu R., Thamm M., Tian L., Merkel J.M., Jones J.C., Carter G.D., Sempos C.T. Vitamin D measurement standardization: the way out of the chaos. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sempos C.T., Durazo-Arvizu R.A., Binkley N., Jones J., Merkel J.M., Carter G.D. Developing vitamin D dietary guidelines and the lack of 25-hydroxyvitamin D assay standardization: the ever-present past. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;164:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kilpatrick L.E., Phinney K.W. Quantification of total vitamin-D-binding protein and the glycosylated isoforms by liquid chromatography-isotope dilution mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:4185–4195. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoofnagle A.N., Whiteaker J.R., Carr S.A., Kuhn E., Liu T., Massoni S.A., Thomas S.N., Townsend R.R., Zimmerman L.J., Boja E., Chen J., Crimmins D.L., Davies S.R., Gao Y., Hiltke T.R., Ketchum K.A., Kinsinger C.R., Mesri M., Meyer M.R., Qian W.J., Schoenherr R.M., Scott M.G., Shi T., Whiteley G.R., Wrobel J.A., Wu C., Ackermann B.L., Aebersold R., Barnidge D.R., Bunk D.M., Clarke N., Fishman J.B., Grant R.P., Kusebauch U., Kushnir M.M., Lowenthal M.S., Moritz R.L., Neubert H., Patterson S.D., Rockwood A.L., Rogers J., Singh R.J., Van Eyk J.E., Wong S.H., Zhang S., Chan D.W., Chen X., Ellis M.J., Liebler D.C., Rodland K.D., Rodriguez H., Smith R.D., Zhang Z., Zhang H., Paulovich A.G. Recommendations for the generation, quantification, storage, and handling of peptides used for mass spectrometry-based assays. Clin. Chem. 2016;62:48–69. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.250563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.CLSI . CLSI document C62-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2014. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Methods; Approved Guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration, 2018, pp. 1–41.

- 72.Abbatiello S.E., Mani D.R., Keshishian H., Carr S.A. Automated detection of inaccurate and imprecise transitions in peptide quantification by multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2010;56:291–305. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.138420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Joseph J.C., Baker C., Sprang M.L., Bermes E.W. Changes in plasma proteins during pregnancy. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1978;8:130–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noor N., Jahan N., Sultana N. Serum copper and plasma protein status in normal pregnancy. J. Bangladesh Soc. Physiol. 2012;7:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haram K., Augensen K., Elsayed S. Serum protein pattern in normal pregnancy with special reference to acute-phase reactants. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1983;90:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1983.tb08898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uchikova E.H. Ledjev, II, Changes in haemostasis during normal pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005;119:185–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Elsenberg E., Ten Boekel E., Huijgen H., Heijboer A.C. Standardization of automated 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays: how successful is it? Clin. Biochem. 2017;50:1126–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.J. Camara, C.A. Gonzalez, S.J. Choquette, National Institute of Standards & Technology Certificate of Analysis Standard Reference Material 1950 Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma, NIST Office of Reference Materials, Gaithersburg, MD, 2019, pp 1–15.

- 79.Kilpatrick E.L., Liao W.L., Camara J.E., Turko I.V., Bunk D.M. Expression and characterization of 15N-labeled human C-reactive protein in Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris for use in isotope-dilution mass spectrometry. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012;85:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.E.L. Kilpatrick, NIST Mass and Fragment Calculator, https://www.nist.gov/services-resources/software/nist-mass-and-fragment-calculator-software.

- 81.B.N. Taylor, C.E. Kuyatt, NIST Guidelines for Evaluating and Expressing the Uncertainty of NIST Measurement Results, https://www.nist.gov/pml/nist-technical-note-1297 (August).

- 82.JCGM 100:2008, Evaluation of Measurement Data — Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (ISO GUM 1995 with Minor Corrections). In: http://www.bipm.org/utils/common/documents/jcgm/JCGM_100_2008_E.pdf, 2008, pp 1–116.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.