Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review summarizes and presents the current state of research quantifying the relationship between mental disorder and overdose for people who use opioids.

Methods

The protocol was published in Open Science Framework. We used the PECOS framework to frame the review question. Studies published between January 1, 2000, and January 4, 2021, from North America, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand were systematically identified and screened through searching electronic databases, citations, and by contacting experts. Risk of bias assessments were performed. Data were synthesized using the lumping technique.

Results

Overall, 6512 records were screened and 38 were selected for inclusion. 37 of the 38 studies included in this review show a connection between at least one aspect of mental disorder and opioid overdose. The largest body of evidence exists for internalizing disorders generally and mood disorders specifically, followed by anxiety disorders, although there is also moderate evidence to support the relationship between thought disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) and opioid overdose. Moderate evidence also was found for the association between any disorder and overdose.

Conclusion

Nearly all reviewed studies found a connection between mental disorder and overdose, and the evidence suggests that having mental disorder is associated with experiencing fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose, but causal direction remains unclear.

Keywords: Opioids, Mental illness, Psychiatric disorder, Toxicity, Drug-related harm

Introduction

Opioid toxicity deaths, commonly referred to as opioid overdose has become a global crisis [1, 2] that has intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Some evidence exists to suggest that opioid overdose is commonly experienced by individuals with co-occurring mental disorder [4–7] but literature that examines these two phenomena together is sparse. This review summarizes the evidence on mental disorder and the risk of opioid overdose to advance understanding of this relationship.

Although past research indicates that individuals with mental disorders are at increased risk for overdose [8–12], there are multiple considerations that have precluded definitive conclusions from being made in this area. First, disentangling the symptoms of substance use disorders, other non-substance use psychiatric disorders, and medication side effects can be challenging, which complicates the identification of the relationship between mental disorder and opioid overdose. For example, individuals with mental disorders are often prescribed opioids or other psychotropic medications [13] that may interact or cumulate with non-prescription or illicit opioids to increase overdose risk. In addition, the historical expansion of diagnostic scope for mental disorders may contribute to over-pathologizing drug use, criminality, and social deviance [14]. Thus, there is difficulty in distinguishing between the presence of a mental disorder and behaviors attributable to the use of drugs, leading to imprecision in the evidence base on mental disorder and opioid use [15].

It is also unclear whether there is an identifiable causal relationship between mental disorder and opioid overdose. While stigma, stress and social exclusion commonly experienced alongside opioid use may produce poor psychological outcomes, opioids may also be used as a form of self-medication for coping with emotional pain or mental disorder symptoms [16]. Otherwise stated, the direction of causality and potential moderators in the relationship are not well understood. Another possibility in discussions about causality, and one consistent with a framework introduced by Dasgupta and colleagues [17], would reflect a process of social causation (also known as indirect selection) [18, 19], where a third factor or set of factors produces suboptimal outcomes in both areas. In this case, where opioid use and mental disorder are both hypothesized to be occurring within processes of social causation, both outcomes may be responses to social and economic precarity [16]. Importantly, scholars have also proposed a countervailing theory of social selection or social drift [20] to explain the connection between mental disorder and socioeconomic marginalization which argues for the reverse: that experiencing mental disorder causes a downward shift in social class. Given these complex pathways, a fulsome understanding of these relationships is unlikely to produce a unidirectional explanation, these pathways likely co-exist, each contributing to understandings of the complexity of the relationship between opioid overdose and mental disorder.

Despite the clear need for conclusive evidence about the intersections between mental disorder and opioid overdose, this relationship has not been clarified or summarized in a systematic way. Specifically, gaps exist in the literature in: 1) establishing the volume and strength of literature supporting the connection is between mental disorder and overdose risk; and 2) understanding the empirical evidence that exists to support the theoretical relationships hypothesized between these phenomena.

The systematic review of the extant literature on mental disorder and opioid overdose presented here began as part of a larger investigation of the literature related to socioeconomic marginalization and opioid overdose, in which we found a preponderance of scientific evidence pointing to the potential role of mental disorder [21]. This systematic review employed an integrated knowledge translation process [22] whereby we partnered with decision makers in establishing the focus of the review, refining review questions and methodology, data retrieval and retrieval tool development, interpretation of review findings, identification of gaps, crafting of recommendations, and dissemination and application of review findings. Given our initial findings, the need for an independent review on mental disorder and overdose specifically was informed by decision-makers in the local community, municipal, provincial, and federal government who required further clarity regarding the evidence on mental disorder and overdose risk. This review responds to that need and systematically summarizes the literature on whether or not broadly defined mental disorder (including both symptoms of disorder and diagnosed mental disorder) are associated with opioid overdose. The review was designed to address the above omissions, summarize existing published research, provide a knowledge base for effective prevention and response strategies, and identify future directions for policy in this area.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Using the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist, the search sought studies that included measures of mental disorder and opioid-related fatal and non-fatal overdose published in English peer-reviewed journals or by governmental sources between January 1, 2000 and January 4, 2021. Only studies conducted in North America, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand were eligible for inclusion, as study stakeholders expressed a desire for a review of studies with the highest contextual and policy comparability. The specific terms related to mental disorder included in the search strategy are summarized in Table 1, and a summary of the Medline search terms used in the review is provided in Appendix A. The PECOS framework (Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design) used to frame our specific mental disorder and opioid overdose research question [23] is listed in Table 1. Two research assistants first conducted title and abstract screening, and subsequently independently assessed full text articles to determine final inclusion eligibility. Differences in opinion about inclusion were resolved by a senior team member. More details about study selection are provided in the protocol, published on the Open Science Framework site [24].

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Review Question | Do mental health issues (including both symptoms of psychological distress and diagnosed psychiatric disorder) increase the risk for opioid overdose? |

| Search Concepts1 |

Mental Health: mental health, mental illness, psychiatric disorder, health care access, social service access; despair, anguish, disability, vulnerability, stigma, social isolation, social exclusion, marginalization Overdose (fatal and non-fatal): poisoning, drug-related poisoning, side-effects/adverse reactions, toxicity, death, morbidity, mortality, overdose Opioids: People who use opioids (medical/non-medical), prescription and non-prescription, oral and injection |

| Databases | MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Google Scholar, Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Cochrane Drug and Alcohol Group (CDAG) Specialized Registry |

| Other Search Strategies | In addition to searching electronic databases, additional searches on clinicaltrials.gov, a comprehensive grey literature search (e.g., www.opengrey.eu, https://deslibris.ca), conference proceedings (e.g., Harm Reduction International, American Public Health Association), and manual searches of the references of included studies other reviews in this area, and studies that have cited the included studies were performed. The search strategy also included contacting experts and community and policy stakeholders to identify unpublished, ongoing, governmental, and other studies not otherwise retrieved through searches for this review |

| PECOS Criteria |

Population: People who use opioids in North America, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. Articles were only included if they had opioids (any opioid, including opioid agonist therapy) identified as a cause of overdose. Poly drug-related overdose papers were included if they included opioid overdose in the cases Exposure: Any measure of mental health as an independent variable in the article (e.g., despair, hopelessness, psychological distress, psychiatric disorder). Articles were included if they had any measure of mental health, broadly defined, as an independent variable in the article. Articles that include mental health variables as controls in their multivariable regression models, for example, were included as long as there were empirical results that showed the effects of the mental health variables on opioid overdose Comparison: Quantitative studies with comparisons between groups with different levels of mental health Outcomes: Opioid-related fatal and non-fatal overdose. Articles were included only if they had overdose as a unique/isolated outcome. Articles examining drug-related harm or mortality might include overdose but also include death or harm from other factors (e.g., motor vehicle accidents) and as such, were excluded. Articles comparing the risk of overdose between different types of opioids were excluded, as they do not address the review question of whether mental health issues increase the risk of overdose Study design: Any study design including quantitative data. Articles that contained empirical data were included. Case-reports, letters, commentaries, reviews, and editorials were excluded |

1Terms related to these key concepts were entered into all computer databases, combined using appropriate Boolean operators. All terms were searched both as subject headings as well as keywords. See Appendix A for a summary of the Medline search terms included

Data collection and extraction

Two research assistants used a standardized form to extract data from the included studies, including year, journal, and type of publication, author’s name, study location, sample, study period, study design, recruitment and sampling, sample size, response rates, age range, operationalization of mental disorder, type of opioid overdose outcome, and statistical analysis. Inconsistencies in the extracted data were noted by the research assistants and resolved through discussion with a senior team member.

Study selection and data synthesis

This review approached the relationship between mental disorder (including both diagnosed disorder—medically diagnosed, assessed, or self-reported—and symptoms of disorder) and opioid overdose broadly and purposely allowed inclusion of different study types, as long as they provided evidence on the review question regarding whether mental disorder and associated symptoms are associated with increased occurrence of opioid overdose (including fatal and non-fatal overdose, overdose-related hospitalizations, and intentional vs. unintentional overdose). As a result, we employed the lumping synthesis technique where all evidence related to mental disorder and opioid overdose was included despite differences between study design and outcome measures [25]. This strategy allows for synthesis and identification of common findings in the relationships between mental disorder and opioid overdose that remain despite minor differences in study participants, context, and design, similar to the approach taken by others investigating determinants of overdose [26]. Substantial conceptual and methodological heterogeneity across the included studies precluded meta-analysis. Instead, findings are summarized by mental disorder variables. The data extraction process for this review included an assessment of bias, for which we used the study quality tools of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (presented in Table 3) [27]. Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias.

Table 2.

Study design and sample characteristics of included studies

| First Author | Study design/Locationa | Sample characteristics | Race/Ethnicity | Recruitment and data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohnert et al. [28] | Case-cohort/USA |

N: 155,434; Age:18–59: 56.1% 60 + : 43.9%; Sex: 93.3% male |

Black: 16.4%; White: 71.8%; Other/Missing: 11.8%; Hispanic: 4.1% |

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) National Patient Care Database (2004–2008) Linked to National Death Index |

| Burns et al. [39] | Cross-sectional/Australia | N: 163; Age: Median: 21; Sex: 54.0% male | NR | Survey with young people (15–30 years) who used heroin from three inner-metropolitan Melbourne general practices (June–December 2000)Linked to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme |

| Campbell et al. [51] | Cohort/USA | N: 396,452; Age: 51.83; Sex: 41.0% male | Asian: 9.7%; Black: 9.4%; Hispanic: 17.2%; Native American: 0.6%; Multi-racial: 4.5%; Other or unknown: 1.8%; White: 56.8% | KPNC’s Electronic Health Records database (2011–2014) |

| Carrà et al. [40] | Cross-sectional/Italy | N: 265; Age: Mean (SD): 35.4 (9.4); Sex: 79.0% male | NR |

Therapeutic community program participants Completed survey for the Psychiatric and Addictive Dual Disorders in Italy (PADDI- TC) project (2010) |

| Chahua et al. [41] | Cohort/Spain | N: 452; Age: Mean (SD): 26 (3.25); Sex: 27% male | NR | Subsample of the ‘ITINERE’ cohort of heroin users |

| Cheng et al. [29] | Cross-sectional/USA | N: 254; Age:18–44 years:57.5%, 45 years or older:42.5%; Sex: NR | White: 98.3%; Black: 0.4%; Other: 0.8% |

Prescription Pain Medication Dataset from the Utah Department of Health (2008–2009) Office of the Medical Examiner Linked to the Labour Commission database |

| Chua et al. [52] | Cohort/USA |

N: 2,752,612; Age: Mean (SD): 17.2 (2.5); Sex: 47.2% male |

NR | 2009–2017 IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database |

| Cochran et al. [53] | Cohort/USA | N: 297,634; Age:18–29:47.3%, 30–64: 52.7%; Sex: 28.7% male | White: 56.2%; Black: 28.2%; Hispanic: 12.1%; Other: 3.6% | Medicaid records from Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (2010–2012) |

| Connery et al. [42] | Cross-sectional/USA | N: 120; Age: Mean (SD): 34 (10.4); Sex: 59% male | White: 89%; Hispanic/Latinx: 7% | Inpatients for detoxification/stabilization unit at an academically affiliated psychiatric hospital |

| Darke et al. [15] | Cross-sectional/Australia | N: 615; Age: Mean (SD): 29.3 (7.8); Sex: 66.0% | NR | Survey with Australian Treatment Outcomes Study participants (2001–2002) |

| Dilokthornsakul et al. [61] | Nested case–control/USA |

N: 3264; Age: < 18–44 years: 55.0%, 45–65 years + : 45.0%; Sex: 30.0% |

NR | Colorado Medicaid claims database |

| Dunn et al. [54] | Cohort/USA | N: 9940; Age: Mean (SD): 54 (16.8); Sex: 40.4% male | NR |

Consortium to Study Opioid Risks and Trend (CONSORT) Study participants (1997–2005) Linked from automated health care data, electronic medical records, and medical-record reviews |

| Fendrich et al. [43] | Cohort/USA | N: 368; Age: mean: 35; Sex: 72.3% male | Non-hispanic white: 57.3%; Other: 42.7% | Addiction Health Evaluation and Disease (AHEAD) Management Study |

| Foley and Schwab-Reese [30] | Ecological/USA | N: NR; Age: NR; Sex: NR | NR |

Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Linked to Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) |

| Follman et al. [55] | Cohort/USA | N: 138,108; Age: Mean (SD): 43.4 (0.4); Sex: 52.4% male | NR | Truven Health MarketScan Research Database (Truven Health Analytics) |

| Gerhart et al. [31] | Ecological/USA | N: NR; Age: NR; Sex: NR | NR |

Personality data from adults who responded to the 44-item Big Five Inventory online Linked to Centers for Disease Control Wonder Database |

| Glanz et al. [56] | Case–control/USA |

N: 14,898; Age: Mean (SD): 56.3 (16.0); Sex: 39.7% male |

White: 72.4%; African American: 5.0%; Other: 7.4%; Missing: 15.2% | KPCO’s Electronic Health Records database (2006–2018) |

| Groenewald et al. [62] | Cross-sectional/USA | N: 1,146,412; Age: 11–14: 33.5%, 15–17: 66.5%; Sex: 52.4% male | NR | Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database (Truven Health Analytics) |

| Hartung et al. [57] | Case–control/USA | N: 3508; Age: < 30: 31.6%, ≥ 30: 68.4%; Sex: 50.3% male | White: 59.5%; Black: 3.3%; Asian: 0.5%; Native American: 2.5%; Other: 6.4%; Unknown: 27.8% |

Oregon Medicaid claims data Linked to vital statistics and prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data |

| Hasegawa et al. [44] | Cohort/USA | N: 19,709; Age: Median (IQR): 42 (27–55); Sex: 43.0% male | non-Hispanic White: 69%; non-Hispanic Black: 9%; Hispanic: 15%; Other: 4% | California and Florida State Emergency Department Databases and State Inpatient Databases (2010–2011) |

| Karmali et al. [58] | Cohort/USA | N: 3922; Age: 18–64: 75.8%, ≥ 65: 24.2%; Sex: 41.8% male | White: 63.6%; Hispanic: 14.8%; Other: 12.2%; Black: 9.4% | KPNC’s Electronic Health Records database (2009–2016) |

| Kline et al. [45] | Cross-sectional/USA | N: 432; Age: Mean (SD): 40.1 (11.6); Sex: 52.1% male | White: 52.2%; African American: 29.1%; Hispanic: 18.4% | Patients from New Jersey addiction treatment agencies |

| Kuo et al. [32] | Cohort/USA | N: 1,766,790; Age: Mean (SD): 52.2 (10.2); Sex: 50.9% male | White: 66.3%; Black: 19.9%; Hispanic: 9.8%; Other: 4.1% | Medicare and National Death Index linkage data |

| Lagisetty et al. [46] | Cohort/USA |

N: 485,513; Age: < 56: 23.3%, ≥ 56: 76.7%; Sex: 93.3% male |

White: 73.3%; Black: 19.1%; Other/Unknown: 7.6% Hispanic: 5.2%; Not Hispanic: 94.8% |

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) database |

| Leece et al. [33] | Case–control/Canada |

N: 1048; Age: Median (IQR): [Case: 42 (36–48)] [Control: 39 (31–45)]; Sex: 62.2% male |

NR |

Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario Linked to Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD) |

| Madadi et al. [37] | Cross sectional/Canada |

N: 1359; Age: Median (IQR): [Opioid Deaths: 44 (35–51)] [Non-opioid deaths: 46 (37–54)]; Sex: 61.8% male |

NR | Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario (2006–2008) |

| Maloney e al. [47] | Case–control/Australia | N: 1500; Age: Mean: 36.4; Sex: 60.0% male | NR | Used data from an ongoing, large retrospective case–control study of individuals previously enrolled in pharmacotherapy maintenance treatment for opioid dependence (2004–2008) |

| Mazereeuw et al. [38] | Case–control/Canada |

N: 1650; Age: Median (IQR): [Case: 49 (40–55)] [Control: 45 (38–52)]; Sex: 59.3% male |

NR | Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario (1992–2014) |

| Nadpara et al. [48] | Nested case–control/USA | N: 45,153; Age: 18–54: 60.0%, 55–65 + : 40.0%; Sex: 52.1% male |

Non-Hispanic White: 5101 (56.8%) Non-Hispanic Black: 1383 (15.4%) Hispanic: 463 (5.2%) Other: 2040 (22.7%) |

PharMetrics Plus data set from the IMS Health Real-World Data Adjudicated Claims–US Database |

| Peterson et al. [49] | Cross-sectional/USA |

N: 61,170; Age: Mean (SE): 46.8 (0.19); Sex: 49.9% male |

NR | 2016 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Readmissions Database (HCUP-NRD) |

| Pham et al. [34] | Case–control/USA |

N:1284; Age: Mean (SD): [Case: 44.5 (11.2)] [Control: 44.9 (11.6)]; Sex: 36.9% male |

White: 80.7%; Black or African American: 4.4%; American Indian or Alaskan Native: 9.4%; Other: 5.4% |

Oklahoma state Medicaid pharmacy and medical claims Linked to medical examiner reports from the Oklahoma State Department of Health’s (OSDH) Fatal Unintentional Poisoning Surveillance System |

| Ranapurwala et al. [35] | Cohort/USA |

N: 229,274 Age: Median: 34; Sex: 86.2% male |

White: 40.4% non-White: 59.6% |

Prison release data from the NC Department of Public Safety Linked to NC death records from the NC Division of Public Health |

| Roxburgh et al. [36] | Panel data/Australia |

N: 1437 Age: 14–39: 36.4%, 40–70 + : 63.6%; Sex: 50.1% male |

NR | National Coronial Information System (NCIS; 2001–2013) |

| Schiff et al. [59] | Cohort/USA | N:169,206; Age: < 35: 74.4%, ≥ 35: 25.6%; Sex: 0% male | White non-Hispanic: 63.5%; Other: 36.5% | Statewide linked database created in response to a mandate from the Massachusetts legislature and overseen by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health |

| Smolina et al. [60] | Case–control/Canada |

N: 59,784; Age: Mean (median): [Male: 39 (37)] [Female: 39 (36)]; Sex: 67.0% male |

NR | BC Provincial Overdose Cohort |

| Suffoletto and Zeigler [63] | Cohort/USA | N:4155; Age: Mean (SD): 34 (11); Sex: 35.21% male | White: 85.29%; Black: 11.82%; Asian: 0.26%; Other: 2.62% | Electronic health record (EHR) data from a single health system in western Pennsylvania |

| Yoon et al. [50] | Cross-sectional/USA | N: 6,686,905; Age: 12 + years; Sex: NR | NR | Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) all-payer inpatient-care database (2010) |

| Zedler et al. [64] | Case–control/USA |

N:8987; Age: Median (IQR): [Case: 62 (10)] [Control: 62 (16)]; Sex: 92.1% male |

Non-Hispanic white: 56.8%; Non-Hispanic black: 15.4%; Hispanic: 5.2%; Other: 22.6% | Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Medical SAS datasets |

aPanel data are multi-dimensional data involving measurements over time

Results

Overall findings

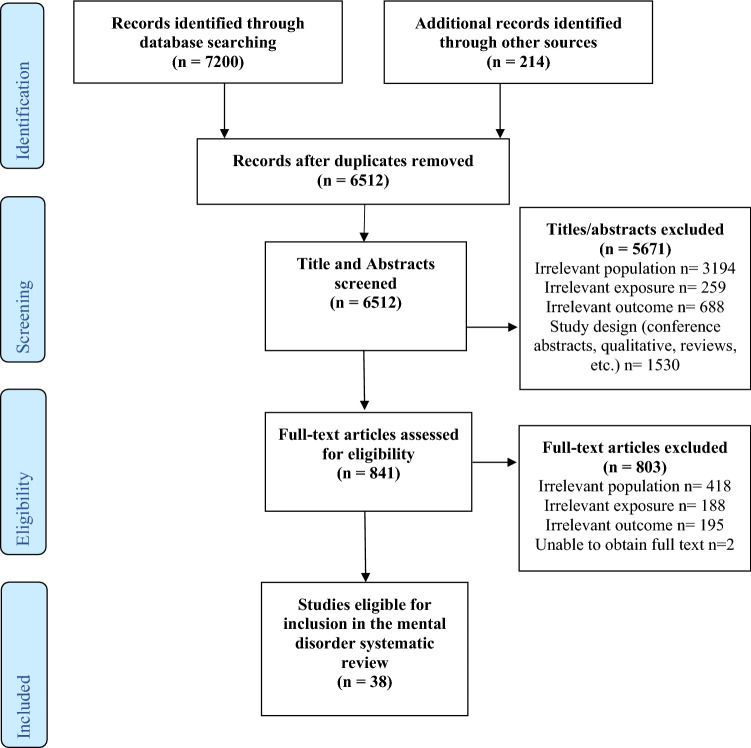

The number of studies retained in each step of the review process can be found in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1. The primary search strategy found 7200 original articles that met the initial screening criteria. The review and screening process led to a final dataset of 38 articles on mental disorder and overdose.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Eleven studies had fatal overdose as the outcome or drew their sample from a population who had experienced fatal overdose [28–38]. Thirteen included only non-fatal overdose as the sole overdose outcome in their studies [15, 39–50], and twelve articles included both fatal and non-fatal overdose [51–60, 63, 64]. Two studies included data from emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations for overdose but did not specify whether the overdoses were fatal or not [61, 62]. Most studies either did not report intention of overdose (n = 17) [15, 33, 35, 39–41, 46, 48, 51–53, 58, 59, 61–64] or examined both intentional and unintentional overdose (n = 17) [30–32, 36–38, 42–45, 47, 49, 54–57, 60] with four examining only unintentional overdose [28, 29, 34, 50]. Many studies (n = 20) included overdose that was attributable to prescription and non-prescription opioids [29, 32, 35–37, 41–47, 49, 50, 56–58, 60, 63, 64], while eleven investigated only prescription opioid overdoses [28, 33, 34, 38, 48, 51–54, 61, 62] and two investigated only non-prescription opioid overdoses [15, 39]. Five studies did not report what type of opioids were included in their data [30, 31, 40, 55, 59]. The included studies analyzed data from the United States (n = 28) [28–32, 34, 35, 42–46, 48–59, 61–64], Australia (n = 4) [15, 36, 39, 47], Canada (n = 4) [33, 37, 38, 60], Italy (n = 1) [40] and Spain (n = 1) [41]. Study designs included nine cross-sectional analyses [15, 29, 37, 39, 40, 42, 45, 49, 50], fourteen cohort studies [32, 35, 41, 43, 44, 46, 51–55, 58, 59, 63], eight case–control studies [33, 34, 38, 47, 56, 57, 60, 64] two studies that used nested case–control designs [48, 61] two ecological studies [30, 31] one study that used panel data [36] and one study that used a case-cohort design [28]. A summary of the study design, data sources, and sample characteristics for the 38 included studies can be found in Table 2.

The majority of the 38 included studies operationalized mental disorder through diagnosed mental disorder, with only six studies reporting on symptoms of disorder [29, 38–40, 42, 45]. Overall, 37/38 of these studies found a significant association with the mental disorder and opioid overdose variables used, with the direction of the association suggesting that people experiencing mental disorder and associated symptoms were more likely to overdose than those who were not. Only one study presented results in the opposite direction [32]. A summary of measures and findings for the 38 included studies can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of measures and findings for included studies

| Author (Year) | Measure of mental disorder | Opioids involved | Overdose characteristic (intent; type) | Measure of overdose | Main findingsa,b | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohnert et al. [28] | Any mental disorder | Prescription | Unintentional; fatal | ICD-10 codes for opioid poisoning deaths |

Mental disorders in individuals with chronic pain: AHR 1.87, 95%CI 1.48–2.38 Mental disorders in individuals with acute pain: AHR 1.77, 95% CI 1.19–2.65 Mental disorders in individuals with substance use disorder: AHR 1.73, 95% CI 1.10–2.72 No significant associations were found between mental disorders and overdose in individuals with cancer |

Fair |

| Burns et al. [39] | Hopelessness, any prior mental disorder, reported self-harm, depressive symptoms | Non-prescription | NR; non-fatal | Self-reported lifetime history of overdose |

Hopelessness: Wald’s statistic 6.12, p < 0.01 Antisocial behaviour: Wald’s statistic 8.21, p < 0.01 Prior mental illness: Wald’s statistic 4.15, p < 0.05 No significant associations were found between depression, reported self-harm and overdose |

Poor |

| Campbell et al. [51] | Mood/anxiety disorders | Prescription | NR; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9 codes for non-fatal opioid poisonings and State death certificates | Mood/anxiety disorders: AHR 2.30, 95% CI 1.98–2.68 | Fair |

| Carrà et al. [40] | Suicidality | NR | NR; non-fatal | Self-reported lifetime history of non-fatal opioid overdose | No significant associations were found between suicide attempts and likelihood of overdose | Poor |

| Chahua et al. [41] | Depression | Prescription and non-prescription | NR; non-fatal | Self-reported past year history of non-fatal opioid overdose | Depression: AOR 2.2, 95% CI 1.01–4.74 | Poor |

| Cheng et al. [29] | Any mental disorder | Prescription and non-prescription | Unintentional; fatal | Post-mortem toxicology and autopsy reports for deaths with at least one opioid |

Mental disorder in opioid overdose decedents vs. poor mental disorder estimates for state-level population: 50.0% vs. 15.0%, p < 0.001 ‘‘Poor mental disorder’’ in the population defined as stress, depression and problems with emotions for more than 7 days in the past 30 days |

Fair |

| Chua et al. [52] | Mental disorder | Prescription | NR; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9/10-CM code for opioid poisoning | Mental disorder: AOR 3.14, 95% CI 2.40–4.12 | Fair |

| Cochran et al. [53] |

Mood/anxiety disorders Adjustment disorders, Personality disorders, other mental disorders |

Prescription | NR; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9 codes for opioid poisoning deaths and hospitalization and ED visits |

Anxiety disorder: ARR 1.26, 95% CI 1.07–1.48 Mood disorders: ARR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.50 No significant associations were found between adjustment disorders, personality disorders, other mental disorder disorders and overdose |

Good |

| Connery et al. [42] | Any mental disorder, Anxiety, Suicidality | Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; non-fatal | Self-reported lifetime history of non-fatal opioid overdose |

Mental disorder in opioid overdose history vs. no opioid overdose history, 72.2% vs. 50.0% p-value = 0.013 History of suicide attempt, 50.0% vs. 17.2% p-value = 0.001 No significant associations were found between anxiety symptoms and overdose |

Poor |

| Darke et al. [15] |

Bipolar Disorder Anti-Social Personality Disorder |

Non-prescription | NR; non-fatal | Self-reported lifetime and past year history of non-fatal opioid overdose |

Bipolar Disorder: OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.44–7.88 Anti-Social Personality Disorder: OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.15–4.21 BPD and ASPD: OR 4.70, 95% CI 2.54–8.69 |

Poor |

| Dilokthornsakul et al. [61] | Any mental disorder | Prescription | NR; NR | ICD-9 codes for opioid hospitalizations and ED visits | History of mental illness: AOR 1.73, 95% CI 1.31–2.29 | Fair |

| Dunn et al. [54] | Depressive disorder | Prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal and non-fatal | ICD codes for opioid poisoning deaths and adverse events | Overdose rates (history of depression vs. no history of depression): 311/100,000 person-years, 95% CI 203–441 vs. 96/100,000 person-years, 95% CI 62–137 | Good |

| Fendrich et al. [43] |

Depression PTSD Psychosis Severe anxiety |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; non-fatal | Self-reported past 3 months history of non-fatal opioid overdose |

Severe depression: AOR 2.46, 95% CI 1.24–4.89 PTSD: AOR 2.77, 95% CI 1.37–5.60 Psychosis: AOR 2.39, 95% CI 1.10–5.15 No significant associations were found between severe anxiety and overdose |

Fair |

| Foley Schwab-Reese [30] | Depression | NR | Intentional and unintentional; fatal | ICD-10 codes for opioid poisoning deaths | Depression and fatal opioid overdose: AIRR 1.26, 95%CI 1.01–1.58; Depression and unintentional fatal opioid overdose: AIRR 1.31, 95%CI 1.03–1.68 | Fair |

| Follman et al. [55] |

Mood Anxiety PTSD |

NR | Intentional and unintentional; NR | ICD-10 codes for opioid poisoning and adverse events |

Anxiety: AOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.12–1.36, p < 0.001 No significant associations were found between mood, PTSD and overdose |

Fair |

| Gerhart et al. [21] | Depression | NR | Intentional and unintentional; fatal | Mortality data provided by from the Kaiser Family Foundation and CDC Wonder Databases | Depression prevalence was significantly associated with opioid overdose deaths: Adjusted Robust Mixed Model: b = 1.97, 95% CI 0.47, 3.47, p = 0.01 | Fair |

| Glanz et al. [56] | Mental disorder diagnosis | Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9/10 codes for opioid poisoning and opioid poisoning deaths | Individuals with mental disorder diagnosis were more likely to have experienced an overdose in two models. Without adjustment for opioid dose in the 3 months before the index date: AOR 2.72, 95% CI 1.43–5.18; With adjustment for opioid dose in the 3 months before the index date: AOR 2.97, 95% CI 1.57–5.64 | Good |

| Groenewald et al. [62] |

Anxiety Mood disorders |

Prescription | NR; NR | ICD-9 codes for opioid poisoning and adverse events |

Anxiety: AHR 1.65, 95% CI 1.33–2.06, p-value < 0.0001 Mood disorders: AHR 2.77, 95% CI 2.26–3.34, p-value < 0.0001 |

Good |

| Hartung et al. [57] |

Depression Psychoses |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9/10 codes for opioid poisoning and opioid poisoning deaths | Those with heroin-involved overdoses were more likely to have depression (28.0% vs. 10.9%, p < 0.001) and psychoses (31.4% vs. 6.3%, p < 0.001) compared to those who have never overdosed | Good |

| Hasegawa et al. [44] |

Psychoses Depressive disorder |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; non-fatal |

Opioid -related near-fatal events involving mechanical ventilation Opioid-related hospitalization |

Psychoses were significantly associated with opioid-related hospitalizations (for those who have an opioid-related ED visit): AOR 5.40, 95% CI 4.85–6.00, p < 0.001 and with frequency of ED visits: AOR 1.44, 95% CI 1.25–1.65, p < 0.001 Depression is significantly associated with opioid-related hospitalizations (for those with an opioid-related ED visit): AOR 2.71, 95% CI 2.46–2.97, p < 0.001 No significant associations were found between depression and frequent ED visits for overdose |

Poor |

| Karmali et al. [58] |

Anxiety Bipolar disorder Depression Panic disorder Schizophrenia Any mental disorder condition |

Prescription and non-prescription | NR; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9/10 codes for opioid poisoning and opioid poisoning deaths |

Anxiety: Among adults with non-fatal opioid overdose from 2009 to 2016, those with a second overdose were more likely to have anxiety compared to those without a second overdose (47.0% vs. 39.5%, p = 0.013) Bipolar disorder: Among adults with non-fatal opioid overdose from 2009 to 2016, those with a second overdose were more likely to have bipolar disorder compared to those without a second overdose (22.3% vs. 14.8%, p < 0.001) No significant associations were found between depression, panic disorder, schizophrenia, any mental disorder and opioid overdose |

Good |

| Kline et al. [45] |

PTSD Suicidal ideation |

Prescription & non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; non-fatal | Self-reported lifetime and past two years history of non-fatal opioid overdose |

Those with persistent overdoses were more likely to have a diagnosis of PTSD (AOR 3.84, 95% Cl l.41–10.46, p = 0.01) than those who have never overdosed No significant associations were found between suicidal ideation and opioid overdose |

Poor |

| Kuo et al. [32] |

Depression Anxiety Bipolar disorder PTSD Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders ADHD Personality disorder |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal | ICD-10 codes for opioid poisoning deaths |

Depression: AOR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09–1.53 Anxiety: AOR 1.65, 95% CI 1.37–1.97 Bipolar disorder: AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.28–1.79 PTSD: AOR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.92 Those who had fatal opioid overdose were more likely to have mental disorders (depression, 56.8% vs. 30.2%; anxiety, 63.4% vs. 30.9%; bipolar disorder, 35.6% vs. 14.0%; schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, 18.8% vs. 11.5%; ADHD, 12.0% vs. 4.6%; personality disorders, 9.8% vs. 4.1%) |

Poor |

| Lagisetty et al. [46] |

Depression Serious mental illness PTSD Anxiety |

Prescription and non-prescription | NR; non-fatal | ICD-9 codes for opioid poisoning |

Opioid-overdose hospitalizations vs. Non-Opioid-related hospitalizations: Depression (56.4% vs 36.7%) p < 0.0001* Serious mental illness (24.2% vs 9.7%) p < 0.0001* PTSD (30.4% vs 19.0%) p < 0.0001* Anxiety (22.3% vs 15.1%) p < 0.05* The p values given here are for all opioid-related hospitalizations (including abuse, dependence and overdose) vs. non-opioid-related hospitalizations |

Fair |

| Leece et al. [33] |

Mood disorder Schizophrenia |

Prescription | NR; fatal | Opioid overdose deaths identified through coroners |

Mood disorder: AOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.00–3.24 No significant associations were found between schizophrenia and opioid overdose deaths |

Fair |

| Madadi et al. [37] |

Depressive Disorder Bipolar Disorder Schizophrenia |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal | Opioid overdose deaths identified through coroners | Individuals who died of intentional overdose were significantly more likely to have mental disorders such as ADD, OCD, bipolar, schizophrenia [OR (95% CI) 2.1 (1.4–3.2)] and depression [OR (95% CI) 5.2 (3.8–7.1)] | Fair |

| Maloney et al. [47] |

Anxiety disorder Depressive episode Screening for Bipolar disorder |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; non-fatal | Self-reported lifetime history of non-fatal opioid overdose |

Those with history of both opioid overdose and suicide attempt were more likely to have anxiety disorder (AOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.04–2.12, p < 0.05), depressive episode (AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.17–2.51, p < 0.05), and screening for bipolar disorder (AOR 2.29, 95% CI 1.55–3.34, p < 0.001) compared to those with history of neither behavior There was no significant difference between those with no overdose or suicide attempt and those with history of opioid overdose only (without suicide attempt) for anxiety disorder, depressive episode, and screening for bipolar disorder |

Fair |

| Mazereeuw et al. [38] | Self-harm Affective disorder Anxiety disorder Psychotic disorder Psychiatrist visits | Prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal | Opioid overdose deaths identified through coroners |

Case subjects were more likely to have had anxiety disorders (63.2% vs. 54.9%, SD = 0.13), affective disorders (11.2% vs. 5.6%, SD = 0.19), received psychiatric care (34.7% vs. 27.5%, SD = 0.16), and have a history of self-harm (8.5% vs. 2.5%, SD = 0.26) in the year preceding opioid-related suicide No significant associations were found between psychotic disorder and opioid-related suicide |

Fair |

| Nadpara et al. [48] |

Depressive Disorder Bipolar disorder Schizophrenia Anxiety disorder ADHD PTSD OCD |

Prescription | NR; non-fatal | Post-overdose reports for ODs with prescription opioids |

Depression in Commercial insured population (CIP): AOR (95% CI) 3.12 (2.84–3.42) Bipolar disorder in CIP: AOR (95% CI) 2.18 (1.83–2.60). Bipolar disorder in Veterans Health Administration (VHA): AOR (95% CI) 1.68 (1.17–2.43). Schizophrenia in CIP: AOR (95% CI) 2.06 (1.17–3.69). Anxiety disorder in CIP; AOR (95%CI) 1.64 (1.50–1.80). ADHD in VHA: AOR (95% CI) 0.33 (0.11–0.99) No significant association between PTSD/OCD and overdose in Commercial insured or VHA populations |

Fair |

| Peterson et al. [49] |

Depression Psychoses |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; non-fatal | ICD-10 codes for opioid poisoning | Psychoses: AOR 1.25, 95% CI 1.01–1.53 AOR for opioid overdose readmissions ≤ 90 days among patients with non-fatal index stays for opioid overdose. No significant associations were found between depression and opioid overdose readmissions | Poor |

| Pham et al. [34] |

Anxiety Mild depression Major depressive disorder Bipolar disorder Schizophrenia |

Prescription | Unintentional; fatal | Toxicology reports from medical examiner |

Bipolar disorder: AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.20–2.65 Schizophrenia: AOR 1.15, 95% CI 1.04–1.27 Case subjects were also more likely to have anxiety (61.7% vs. 32.7%, p < 0.001), mild depression (38.0% vs. 23.7%, p < 0.001), and major depressive disorder (30.8% vs. 17.0%, p < 0.001). However, anxiety and depression were not significant in multivariable models |

Good |

| Ranapurwala et al. [35] | In-prison mental disorder treatment | Prescription and non-prescription | NR; fatal | ICD-10 codes for opioid poisoning deaths |

Those who received in-prison mental disorder treatment were more likely to experience opioid overdose death after release (AHR 1.9, 95% CI 1.7–2.2) and 1 year after release (AHR 2.2, 95% CI 1.7–2.9) No significant associations were found between in-prison mental disorder treatment and opioid overdose death 2 weeks after release |

Fair |

| Roxburgh et al. [36] | Mental health problems | Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal | Post-mortem toxicology and autopsy reports |

Mental health problems in deaths where codeine toxicity was a contributory factor: Intentional vs. accidental OD: OR (95% CI) 2.1 (1.6–2.7) Mental health problems defined as any history of mental health problems recorded in the National Coronial Information System |

Poor |

| Schiff et al. [59] |

Anxiety Depression |

NR | NR; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9 code for opioid poisoning, toxicology reports, ambulance incident report |

OUD diagnosis and overdose in the year before or after delivery vs. OUD diagnosis but no overdose in the year before or after delivery vs. no diagnosis of OUD in the year prior Anxiety: 82.1% vs. 60.2% vs. 18.29%, p < 0.001 Depression: 84.8% vs. 61.2% vs. 18.90%, p < 0.001 |

Fair |

| Smolina et al. [60] |

Major depressive disorder Anxiety disorder Adjustment disorder Bipolar disorder Schizophrenia Personality disorder ADHD |

Prescription and non-prescription | Intentional and unintentional; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9/10 codes for opioid poisoning and opioid poisoning deaths, record of naloxone administration in ambulance incident report, or cases identified by coroners, ED physicians or the Drug and Poison Information Centre |

Prevalence of diagnosed mental disorders in the past year and in the past 5 years was significantly different between overdoses cases and controls Past year prevalence: Major depressive: Men (14% vs. 2.6, p < 0.01) Women (21% vs. 4.4%, p < 0.01) Anxiety: Men (13% vs. 2.2, p < 0.01) Women (20% vs. 3.7%, p < 0.01) Adjustment disorder: Men (6.2% vs. 0.67%, p < 0.01) Women (9.5% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.01) Bipolar disorder: Men (6.3% vs. 0.82%, p < 0.01) Women (11% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.01) Schizophrenia: Men (7.0% vs. 0.93%, p < 0.01) Women (7.3% vs. 0.38%, p < 0.01) Personality disorder: Men (3.3% vs. 0.16%, p < 0.01) Women (5.2% vs. 0.16%, p < 0.01) ADHD: Men (1.9% vs. 0.35%, p < 0.01) Women (1.2% vs. 0.30%, p < 0.01) Past 5-year prevalence: Major depressive: Men (34% vs. 7.9, p < 0.01) Women (52% vs. 13%, p < 0.01) Anxiety: Men (30% vs. 6.8, p < 0.01) Women (45% vs. 11%, p < 0.01) Adjustment disorder: Men (16% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.01) Women (25% vs. 4.7%, p < 0.01) Bipolar disorder: Men (14% vs. 2.2%, p < 0.01) Women (23% vs. 2.9%, p < 0.01) Schizophrenia: Men (12% vs. 1.6%, p < 0.01) Women (12% vs. 0.88%, p < 0.01) Personality disorder: Men (7.6% vs. 0.54%, p < 0.01) Women (11% vs. 0.66%, p < 0.01) ADHD: Men (4.9% vs. 1.1%, p < 0.01) Women (3.3% vs. 0.83%, p < 0.01) |

Fair |

| Suffoletto and Zeigler [63] |

Anxiety disorder Bipolar disorder Depression disorder Schizophrenia Stress disorder Any mental disorder |

Prescription and non-prescription | NR; fatal and non-fatal | ICD-9/10 codes for opioid poisoning and opioid poisoning deaths |

Anxiety disorder: AHR 1.41, 95% CI 1.13–1.77 Depression disorder: AHR 1.38, 95% CI 1.02–1.73 Any mental disorder: AHR 1.32, 95% CI 1.08–1.61 AHR for repeated overdose No significant associations were found between bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, stress disorder and repeated opioid overdose |

Good |

| Yoon et al. [50] |

Depressive Disorder Bipolar disorder Anxiety disorder |

Prescription and non-prescription | Unintentional; non-fatal | ICD-9 codes for opioid- poisoning |

Bipolar disorder: Poisoning by prescription opioids; Female: ARR (95% CI) 1.05 (1.01–1.10) Depressive disorder: Poisoning by illicit opioids; Female: ARR (95% CI) 1.06 (1.00–1.12) Poisoning by prescription opioids; Male: ARR (95%CI) 1.10 (1.05–1.15); Female: ARR (95% CI) 1.12 (1.08–1.15) No significant association between anxiety disorder and poisoning by illicit/prescription opioids |

Fair |

| Zedler et al. [64] |

ADHD Anxiety disorder Bipolar disorder Depression PTSD Schizophrenia |

Prescription and non-prescription | NR; fatal and non-fatal |

ICD-9 codes for opioid poisoning and adverse events CPT codes for mechanical ventilation or critical care |

ADHD: AOR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–1.0, p = 0.048 Bipolar disorder: AOR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.4, p = 0.005 Case subjects were also more likely to have anxiety disorder (22.0% vs. 8.3%, p < 0.001), depression (43.7% vs. 19.1%, p < 0.001), PTSD (27.1% vs. 13.7%, p < 0.001), and schizophrenia (4.4% vs. 1.4%, p < 0.001) |

Fair |

aStatistically significant results denoted in bold

bLanguage (e.g., mental health problems, mental illness, mental disorder, etc.) used in the findings column in accordance with descriptions used in the original study

Risk of bias within included studies

The risk of bias assessments indicated a mix of bias-related concern with 10/38 of the original papers having ‘poor’ assessments, 20/38 having ‘fair’ assessments, and 8/38 studies having ‘good’ assessments. Many studies only measured exposure variables once during the study; failed to include multivariable controls for potential confounding variables; did not report information about power, effect estimates, or sample size justifications; or presented bivariable relationships only. The most serious concerns about risk of bias in the included studies arise from mental disorder variables only being assessed once or being assessed after the outcome [15], and inconsistent measurement of mental disorder across groups [29]. The dataset is largely observational, limiting causal conclusions. Results from included studies are organized in the below summary by mental disorder categories.

Internalizing disorders

The evidence on internalizing mental disorders and opioid overdose, including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive and related disorders, trauma and stressor-related disorders are summarized by specific disorder below.

Mood disorders

Twenty-four studies examined the connection between mood disorders and overdose, and 17/24 of these studies found mood disorders to be significantly and positively associated with opioid-related overdose. This association has been found in the general population: across US states (AIRR 1.26, 95% CI 1.01–1.58 [30]), in California and Florida (AOR 2.71, 95% CI 2.46–2.97, p < 0.001 [44]), in Ontario, Canada (AOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.00–3.24; [33]),and in British Columbia (men: 34.0% vs. 7.9%, p < 0.01; women: 52.0% vs. 13%, p < 0.01; [60]. Depression has been found to be associated with opioid overdose among Medicare/Medicaid enrollees: in Pennsylvania (adjusted OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.50) [53], in Oregon (28.0% vs. 10.9%, p < 0.001 [57]), and nationally in the US (56.8% vs. 30.2%; [32]. Associations between depression and overdose were also present in samples that studied those with substance use disorders specifically: in New South Wales (non-fatal overdose and suicide attempt AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.17–2.51, p < 0.051 [47]), in Boston (AOR 2.46, 95% CI 1.24–4.89; [43]),and in Madrid (AOR 2.20, 95% CI 1.01–4.74; [41].

This association has also been found among patients with opioid prescriptions in two national US studies (311/100,000 person-years, 95% CI 203–441 vs. 96/100,000 person-years, 95% CI 62–137) [54] and (AOR 3.12, 95% CI 2.84–3.42) [48] and in North Carolina (AHR 2.30, 95% CI 1.98–2.68) [51].2 Significant associations were additionally found using data from community hospitals across the US (prescription opioids, males: ARR 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.15, p < 0.001), females: ARR 1.12 (95% CI 1.08–1.15, p < 0.001)) [50], electronic health records data (repeat overdose, AHR 1.38, 95% CI 1.02–1.73 [63]). A connection between depression and overdose was also present in studies of commercially insured adolescents (AHR 2.77, 95% CI 2.26–3.34 [62]), pregnant/postpartum women (depression prevalence with overdose 84.8% vs. opioid use disorder 61.2% vs. neither 18.9%, p < 0.001 [59], and Veterans Health Administration claims (56.4% vs. 36.7%, p < 0.0001 [46]. Non-significant findings or findings that did not retain significance in multivariable analysis include those from a study with Veterans Health Administration patients [64], those eligible for Medicaid in Oklahoma [34],the general population of US adults [31], repeat overdose events [49, 58],commercially insured individuals [55], and young people who use heroin in Australia [39].

Anxiety disorders

Seventeen studies examined the connection between anxiety disorders and overdose, and 12 of these studies found a significant association. Those with anxiety disorders were more likely to experience opioid overdose in Ontario (cases 63.2% vs. controls 54.9%, standardized difference = 0.13; [38]), in British Columbia (men: 30.0% vs. 6.8%, p < 0.01; women: 45.0% vs. 11.0%, p < 0.01; [60]), and in people presenting to an emergency department in Pennsylvania (repeat overdose AHR 1.41, 95% CI 1.13–1.77; [63]). These association were also seen in two national samples of the Medicare enrollee population (adjusted OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.07–1.48) [53] (63.4% vs. 30.9%) [32], as well as the commercially insured population in four studies: three with adult populations (AOR (95% CI) 1.64 (1.50–1.80) [48]), AOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.12–1.36 [55], repeat overdose events for those with anxiety 39.5% vs. 47.0%, p = 0.013 [58]), and one with adolescents (prescription opioid overdose AHR 1.65, 95% CI 1.33–2.06; [62]). Other samples where this relationship was seen include those with substance use disorder in New South Wales (non-fatal overdose and suicide attempt AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.17–2.51, p < 0.053,association not present in subgroup analysis [47]),among Veterans Health Administration claims (anxiety in those with overdose 22.3% vs. non-opioid related hospitalizations 15.1%, p < 0.054; [46], and in a cohort of pregnant/postpartum women (prevalence of anxiety among those with overdose 82.1% vs. opioid use disorder 60.2%, vs. neither 18.3% p < 0.001 [59]. Non-significant findings were present in Veterans Health Administration patients [64], decedents eligible for Medicaid in Oklahoma [34], samples of inpatient populations [42, 50] and people with substance use disorders in Boston [43].

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive compulsive disorder and adjustment disorders

Ten studies examined other internalizing disorders including posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and adjustment disorders. Six of these studies found significant associations, five of which were in the hypothesized direction. Studies in this review found a significant positive association between PTSD and opioid overdose among people with substance use disorders in Boston (non-fatal overdose AOR 2.77, 95% CI 1.37–5.60; [43]), those recruited from methadone or residential detox programs in New Jersey (AOR 3.84, 95% Cl l.41–10.46, p = 0.01 [45]), and in Veterans Health Administration claims (claims for opioid overdose hospitalizations vs. non-opioid hospitalizations 30.4% vs. 19.0%, p < 0.00015) [46]. Similar trends were seen with past year affective disorder in Ontario (case 11.2% vs. controls 5.6%, Standardized Difference = 0.19 [38]6), and past 5-year adjustment disorder in British Columbia (men: cases 16.0% vs. controls 2.4%, p < 0.01, women: 25.0% vs. 4.7%, p < 0.01) [60]. Conversely, one study found a negative association with PTSD and fatal opioid overdose among Medicare enrollees in the US (AOR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.92 [32]). Four studies failed to find significant associations or found bivariable associations that did not retain significance in multivariable models in the commercially insured population [48, 55], veterans [48, 64], and Medicare enrollees in Pennsylvania [53].7

Externalizing disorders

The evidence on opioid overdose and externalizing disorders is summarized below by disorder type, in this case, for personality disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Personality disorders and antisocial behavior

Five studies examined personality disorders and associated antisocial behaviors and 4/5 of these studies found significant associations with higher rates of opioid overdose. Associations between antisocial personality disorder and non-fatal opioid overdose were seen in two studies conducted with people who use heroin in Australia (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.15–4.21 [15], Wald’s statistic: 8.21, p < 0.01 [39]). Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have had a prior personality disorder compared to those with no overdose when measured in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in the United States (9.8% vs 4.1%, p < 0.001) [32], and in British Columbia (for men past year personality disorder 3.3% vs. 0.16%, p < 0.01, and women 5.2% vs. 0.16%, p < 0.01) [60]. One study done in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in Pennsylvania found no significant associations [53].

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Four studies in this review investigated the association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and opioid overdose. Two of these studies found significant associations. Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have ADHD compared to those with no overdose when measured in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in the United States (12.0% vs 4.6%, p < 0.001) [32], and in British Columbia (for men past year prevalence 1.9% vs. 0.35%, p < 0.01, and women 1.2% vs. 0.30%, p < 0.01) [60]. Studies done with the commercially insured [48] and veteran population [48, 64] found no association with opioid overdose.

Thought and other disorders

Similar to other reviews in this area [65], we have additionally summarized the evidence for thought disorders and overdose, including bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia and psychoses (otherwise undefined).

Schizophrenia and psychoses

Schizophrenia and psychoses were examined in eight included studies, and five found significant associations with opioid overdose. A relationship between psychoses and overdose was seen among people prescribed opioids in the commercially insured population (schizophrenia AOR 2.06, 95% CI 1.17–3.69) [48], the general population in California and Florida (psychoses and hospitalization AOR 5.40, 95% CI 4.85–6.00, p < 0.001, psychoses and frequency of ED visits AOR 1.44, 95% CI 1.25–1.65, p < 0.001 for opioid overdose) [44], and patients with hospital stays for opioid overdose in a US-based national cohort (AOR: 1.25, 95% CI:1.01–1.53) [49]. Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have schizophrenia or psychoses compared to those with no overdose when measured in a cohort of Medicare enrollees in the United States (18.8% vs 11.5%, p < 0.001) [32], and in British Columbia (for men past year prevalence 7.0% vs. 0.93%, p < 0.01, and women 7.3% vs. 0.38%, p < 0.01) [60].

Non-significant findings between schizophrenia and opioid overdose came from studies done with veterans [64], patients receiving methadone [33], and ED patients in Pennsylvania [63].

Bipolar disorders

Ten studies examined bipolar disorder and opioid overdose, and nine found associations with overdose. Bipolar disorder was associated with overdose in an Australian study of people with substance use disorder (OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.44–7.88) [15], in commercially insured (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.83–2.60) [48] and veteran populations prescribed opioids in the US,(OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.17–2.43) [48], and for females (ARR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00–1.12, p < 0.05) but not males who were prescribed opioids [50]. Those who experienced overdose were more likely to have bipolar disorder than controls when measured: in a cohort of Medicare enrollees across the US (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.28–1.79) [32], among members of Oklahoma’s Medicaid program (AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.20–2.65) [34], in patients of the Veterans Health Administration (AOR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.4, p = 0.005) [64], among patients with repeat overdose in California (22.3% vs. 14.8%, p < 0.001) [58], in those with both opioid overdose and suicide attempt in New South Whales (AOR 2.29, 95% CI 1.55–3.34, p < 0.0018 [47]), and in both men (past year disorder 6.3% vs. 0.82%, p < 0.01) and women (11% vs. 1%, p < 0.01) in British Columbia [60]. A multivariable analysis on a retrospective cohort of persons with non-fatal opioid overdose in Pennsylvania did not find a significant association with bipolar disorder [63].

Any disorder and psychological distress

Some included papers looked at combined measures of any mental disorder and opioid overdose or investigated symptoms of mental disorder in the form of suicidality and hopelessness, or intent of opioid overdose. The results of those papers are summarized below.

Any disorder

Twelve studies included in the review examined any combined measures of mental disorder and 10/12 found significant associations with opioid overdose events. Mental disorder diagnosis was significantly associated with overdose: among those prescribed long-term opioid therapy in Colorado (adjusted matched OR 2.97, 95% CI 1.57–5.64) [56], for commercially insured patients in the US (AOR 3.14; 95% CI 2.40–4.12) [52], among three subpopulations of US veterans who were prescribed opioids (those with chronic pain AHR 1.87, 95% CI 1.48–2.38; acute pain AHR 1.77, 95% CI 1.19–2.65; and substance use disorder AHR 1.73, 95% CI 1.10–2.72) [28], and in ED patients in Pennsylvania (repeat overdose AHR 1.32, 95% CI 1.08–1.61) [63]. Similar trends were seen for former inmates who received prior in-prison mental disorder treatment (1-year post release AHR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.7–2.9) [35], and in patients on Medicaid with a history of mental disorder (hospitalization/ED visit for overdose AOR 1.73, 95% CI 1.31–2.29) [61]. When compared to controls, those with overdose were more likely to have a history of mental disorder or serious mental illness, a trend present among patients of mental hospitals in the US (72.2% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.013) [42], in a study of US veterans prescribed opioids (24.2% vs 9.7%, p < 0.0001 for opioid related hospitalizations) [46], in young people using heroin in Australia (Wald’s statistic: 4.15, p < 0.05) [39], and in fatal opioid overdose cases in Utah [50.0% vs. 15.0%, p < 0.0019) [29]. However, two bivariable analyses found no association between mental disorder and non-fatal opioid overdose in California [58], or in therapeutic communities in Italy [40].

Suicidality and self-harm

Three studies examined symptoms of mental disorder and opioid overdose and 2/3 found significant associations. Opioid overdose was associated with hopelessness in young people who use heroin in Australia (hopelessness, Wald’s statistic: 6.12, p < 0.01; self-harm, non-significant) [39] and with history of suicide among adults recruited from psychiatric hospitals in the US (50% vs. 17.2%, p = 0.001) [42]. In a cross-sectional study in New Jersey, no significant bivariable relationship was detected between suicidal ideation and non-fatal opioid overdose [45].

Intentionality

Three of the papers that grouped mental disorders together or examined symptoms of mental disorder specifically looked at associations with likelihood of an intentional (vs. unintentional) opioid overdose, and all found disorders/symptoms to be associated with intentional overdose. These bivariable associations were seen in Australia, for those with a history of mental health problems recorded in the National Coronial Information System (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.6–2.7) [36] and in Ontario, for those with a diagnosed disorder (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.4–3.2, p = 0.0005) [37]. In a different study of Ontario residents, people with fatal intentional opioid overdose were more likely to have a history of self-harm in the year preceding death than people with fatal accidental opioid overdose (standardized difference: 0.26) [38].

Discussion

Summary of findings

Overall, 37/38 studies included in this review show a connection between mental disorders and opioid overdose with only one association reported that was not in the hypothesized direction. The largest volume of evidence was found for internalizing disorders generally and mood disorders specifically, although there was also moderate evidence to support the relationship between anxiety disorders and opioid overdose. The presence of thought disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, BPD) appears to be associated with opioid overdose. When studies included multiple disorders together in their analyses, evidence was found for the association between any disorder and overdose. Fewer studies investigated externalizing disorders, but most studies that looked at personality and anti-social disorders found significant associations with opioid overdose. The relationship between mental disorder and opioid overdose appears to be present in the general population, among people who use prescription opioids, Medicare/Medicaid enrollees, youth, and veterans. Included studies did not examine variations in these relationships by race/ethnicity, and very few examined differences by gender. Mental disorders may be more common among those who have intentional opioid overdose than unintentional opioid overdose, but more evidence is required to confirm this. Given our findings, it is apparent that mental disorder plays a role in opioid overdose. However, there was substantial variation in measurement and type of independent and dependent variables examined, as well as in the populations and study settings, limiting more nuanced conclusions about this relationship.

Limitations

We reviewed the literature on a wide range of mental disorder issues and opioid overdose. To make the results of our review widely applicable for those making decisions in the overdose crisis, we chose to include studies with any type of opioid overdose measure in the review. By undertaking a broad review, we were able to explore whether the associations between mental disorder and opioid overdose were similar across different disorders, different settings, and different populations. A narrower review would have reduced the number of included studies and thus may have been more susceptible to erroneous conclusions [66]. However, including a variety of outcome measures also presents limitations, including the inability to identify unique risks from different outcomes (e.g., fatal and non-fatal overdose) and the inability to conduct statistical meta-analyses. There were no experimental study designs or mediation analyses among the included papers and this limits any ability to derive causal pathways or make more definitive conclusions about the way mental disorder is related to opioid overdose.

Future directions

The lack of conclusive findings on causal relationships connecting mental disorder to opioid overdose is a challenge that could be first met with qualitative research conducted to elucidate the pathways and mechanisms linking these two phenomena. In recognition of the structural factors intersecting with the opioid crisis including, for example, diminished economic opportunity, colonization, racialization, increasing isolation, and income inequality, more attention should be given to the way these shared root causes impact mental disorder and opioid use [17, 67] and the potential for variation in outcomes for people affected by these structural factors.

Additionally, more quantitative research is needed to determine causal direction in the relationships and whether the connection between mental disorder and opioid overdose is in part a result of a connection to socioeconomic marginalization either through social selection [20], social causation [68, 69], or both. Although none of the studies included in this review examined casual direction, given the severity of the overdose emergency, it remains imperative that we pursue such an understanding in efforts to mitigate the catastrophic crisis. Recent studies have examined “diseases of despair,” or the connected trends of increasing fatal drug overdose, suicide, and alcohol-related illness [18, 19, 70] and found common causes to each population health challenge. Analyzing these trends reveals complex and interrelated environmental, contextual and social issues associated with the increase in overdose [71] including deepening socioeconomic marginalization, [72–74] chronic physical pain, [75] disconnection, and hopelessness [70]. These same factors are also associated with mental disorder, leading scholars to suggest that the connection between these phenomena may have roots in social distress and economic hardship [17] that require further investigation.

The literature included in this review largely focused on diagnosed mental disorder. This is further complicated by the variety of different types of mental disorders, and the possibility exists that the relationships differ by type of disorder, an area worthy of further investigation. We included search terms designed to identify studies that measured exclusion, hopelessness, isolation, stigma, and symptoms of mental disorder more broadly, but found little empirical research published in this area. Thus, more research is needed on not just diagnosed mental disorder and opioid overdose, but also the associated phenomena that may be affecting overdose risk.

Individuals struggling concurrently with mental disorder and opioid use experience higher levels of complexity in symptoms, face more pronounced exclusion, require more integrated treatment, have poorer outcomes, and incur higher costs [76]. Therefore, integrated clinical, policy, and programmatic responses are critically needed, and future research should focus on developing evidence that can support such a response.

In conclusion, based on the included studies, those with mental disorders appear to be at increased risk of intentional and unintentional fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose, with both prescription and non-prescription opioids, and these associations have been found to exist in a wide variety of subpopulations. A complete understanding of the relationship requires more empirical evidence related to directionality, the social and structural root causes of mental disorder, and the implications for different subgroups of the population and for disorders with differing etiology [77].

Appendix A. Medline search strategy

| Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) < 1946 to January 4, 2021 > |

|

Search Strategy: 1 mental disorders/or anxiety disorders/or "bipolar and related disorders"/or "disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders"/or dissociative disorders/or elimination disorders/or mood disorders/or motor disorders/or neurocognitive disorders/or neurodevelopmental disorders/or personality disorders/or "schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders"/or "trauma and stressor related disorders"/(238,726) 2 affective disorders, psychotic/or capgras syndrome/or delusional parasitosis/or morgellons disease/or paranoid disorders/or psychotic disorders/or psychoses, substance-induced/or schizophrenia/(144,299) 3 Mental Health/(40,321) 4 depressive disorder/or depression, postpartum/or depressive disorder, major/or depressive disorder, treatment-resistant/or dysthymic disorder/or premenstrual dysphoric disorder/or seasonal affective disorder/(110,300) 5 Anxiety/(83,253) 6 anxiety disorders/or agoraphobia/or anxiety, separation/or neurocirculatory asthenia/or neurotic disorders/or obsessive–compulsive disorder/or panic disorder/or phobic disorders/(79,407) 7 phobic disorders/or phobia, social/(11,399) 8 Depression/(122,161) 9 stress disorders, traumatic/or psychological trauma/or stress disorders, post-traumatic/or stress disorders, traumatic, acute/(35,256) 10 "attention deficit and disruptive behavior disorders"/or attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity/or conduct disorder/(33,384) 11 (Psychiatric or Mental Disorder* or Depress* or MDD or Bipolar or Panic or Anxiety or Phobia or PTSD or ADHD or Schizophrenia or mental or stress or "attention deficit" or "major depress*" or "post trauma*").ti,ab. (1,788,015) 12 exp Opioid-Related Disorders/(27,403) 13 Opioid-Related Disorders.ti,ab. (22) 14 exp Analgesics, Opioid/(117,988) 15 opioid analgesics.ti,ab. (3549) 16 exp Narcotics/(126,090) 17 Narcotics.ti,ab. (5860) 18 exp Morphinans/(80,736) 19 Morphinans.ti,ab. (109) 20 exp Methadone/(12,542) 21 exp Fentanyl/(16,003) 22 Tramadol/(3179) 23 Prescription Drug Misuse/(1900) 24 Prescription Drug Overuse/(324) 25 (Heroin Dependence or Morphine Dependence or Opium Dependence or Prescription Drug Misuse or Prescription Drug Overuse).ti,ab. (1684) 26 (Abstral or Actiq or Avinza or Codeine or Demerol or Meperidine or Pethidine or Dilaudid or Dolophine or Duragesic or Doloral or Fentora or Fentanyl or Sufentanil or Sufenta or Carfentanil or Carfentanyl or Hydrocodone or Hysingla ER or Methadose or Methadon$ or Metadol or Morphabond or Nucynta ER Onsolis or Oramorph or Oxaydo or RoxanolT or Sublimaze or Xtampza ER or Zohydro ER or BuTrans or Suboxone or Statex or Talwin or Nucynta or Ultram or Tramacet or Tridural or Tramadol or Durela or Dihydromorphine or Ethylmorphine or Hydromorphone or Thebaine or Levorphanol or Morphin* or Morfin* or Hydroxycodeinon or Oxiconum or Oxycone or Oxycontin or Oxycodone or Oxymorphone or Pentazocine or Propoxyphene or Fiorional or Robitussin or Empirin or Roxanol or Duramorph or Tylox or Tramal or Dipipanone or Remifentanil or Papaveretum or Tapentadol or Opioid* or Opiate* or Heroin or Opium or Subutex or Buprenex or Buprex or Buprine).ti,ab. (186,427) 27 (Anexsia or Co-Gesic or Embeda or Exalgo or Hycet or Hycodan or Hydromet or Ibudone or Kadian or Liquicet or Lorcet or Lorcet Plus or Lortab or Maxidone or MS Contin or Norco or Opana ER or OxyContin or Oxycet or OxyNEO or Oxycocet or Palladone or Percocet or Percodan or Reprexain or Rezira or Roxicet or Roxicodone or Targiniq ER or TussiCaps or Tussionex or Tuzistra XR or Tylenol or Vicodin or Vicodin ES or Vicodin HP or Vicoprofen or Vituz or Xartemis XR or Xodol or Zolvit or Zutripro or Zydone).ti,ab. (713) 28 ("poly?substance use" or "poly?drug use").ti,ab. (1267) 29 Drug Overdose/(11,794) 30 "Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions"/(32,743) 31 mortality/or "cause of death"/or fatal outcome/or hospital mortality/(191,882) 32 (poisoning or overdose or toxic or toxicity or death* or mortality or mortalities or fatal*).ti,ab. (2,114,367) 33 (emergency or emergencies or hospitalization or hospitalisation).ti,ab. (409,654) 34 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 (230,234) 35 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 (2,515,891) 36 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 (1,992,812) 37 (North America or America or Canada or Canadian or American or United States or USA or Australia or UK or United Kingdom or England or Wales or Scotland or Mexico or Alberta or British Columbia or Manitoba or New Brunswick or Newfoundland or Northwest Territories or Nova Scotia or Nunavut or Ontario or Prince Edward Island or Quebec or Saskatchewan or Yukon or Alabama or Alaska or Arizona or Arkansas or California or Colorado or Connecticut or Delaware or Florida or Georgia or Hawaii or Idaho or Illinois or Indiana or Iowa or Kansas or Kentucky or Louisiana or Maine or Maryland or Massachusetts or Michigan or Minnesota or Mississippi or Missouri or Montana or Nebraska or Nevada or New Hampshire or New Jersey or New Mexico or New York or North Carolina or North Dakota or Ohio or Oklahoma or Oregon or Pennsylvania or Rhode Island or South Carolina or South Dakota or Tennessee or Texas or Utah or Vermont or Virginia or Washington or West Virginia or Wisconsin or Wyoming or American Samoa or Guam or Northern Mariana Islands or Puerto Rico or Virgin Islands).ti,ab. (1,438,245) 38 (Andorra or Austria or Balkan Peninsula or Belgium or Albania or Bosnia or Bulgaria or Croatia or Czech Republic or Hungary or Kosovo or Macedonia or Moldova or Montenegro or Poland or Belarus or Romania or Russia or Serbia or Slovakia or Slovenia or Ukraine or France or Germany or Gibraltar or Greece or Ireland or Italy or Liechtenstein or Luxembourg or Mediterranean Region or Monaco or Netherlands or Portugal or San Marino or Denmark or Finland or Iceland or Norway or Sweden or Spain or Switzerland or Armenia or Azerbaijan or Ireland or Armenia or Georgia or Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan or Moldova or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vatican City).ti,ab. (584,214) 39 37 or 38 (1,953,198) 40 (determinant* or predictor* or factor* or correlate*).ti,ab. (4,644,515) 41 36 or 40 (6,136,388) 42 34 and 35 and 39 and 41 (2191) 43 limit 42 to (English language and humans and yr = "2000 -Current") (1492) |

Author contributions

LR and JVD were responsible for conceptualization. LR was responsible for supervision, funding acquisition, and writing (review and editing). JVD was responsible for project administration, formal analysis, methodology, and writing (original draft preparation). CT, VP, and AM were responsible for formal analysis, investigation, and writing (review and editing). SM was responsible for formal analysis and investigation. MK was responsible for data curation and methodology.

Funding

This study was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Knowledge Synthesis Grant (OCK-156771) as well as a CIHR Foundation grant (CIHR; FDN-154320) that supports the research activities of LR. LR is additionally supported through the Canada Research Chairs program by a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Social Inclusion and Health Equity. JVD is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellow Award from CIHR and a Research Trainee award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. SM is supported by a Doctoral Research Award from CIHR. MK is supported by Vanier Canada Graduate and Pierre Elliott Trudeau Doctoral Scholarships. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable. (All studies included in the review are available publicly.)

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors of this report have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

Not applicable. (This study is a systematic review and did not require ethical approval as no human subject research was conducted.)

Footnotes

Association was not present in subgroup analysis.

This study did not differentiate results for those with depressive/mood disorders from those with anxiety disorders, and results have been included in the mood disorder category due to the higher prevalence of mood than anxiety disorders in the population.

Association was not present in subgroup analysis.

P value presented only for opioid vs. non-opioid related hospitalizations.

P value compares opioid-related hospitalizations with non-opioid-related hospitalizations.

The definition used for affective disorder was not provided, and thus, results are reported in this section given the potential inclusion of multiple mood disorders.

The definition of adjustment disorders and “miscellaneous other disorders” was not provided, results are reported in this section given the potential inclusion of multiple mood disorders.

Association was not present in subgroup analysis.

Notably, the bivariable, uncontrolled analyses used different measures of mental disorder in the two groups being compared, making comparisons difficult.

References

- 1.Degenhardt L, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1564–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Shiels MS, Thomas D, Freedman ND, Berrington de González A. Premature mortality from drug overdoses: a comparative analysis of 13 organisation for economic co-operation and development member countries with high-quality death certificate data, 2001 to 2015. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(5):352–354. doi: 10.7326/M18-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BC Coroners Service Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General, “Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC January 1, 2010–April 30, 2020,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2020

- 4.Bjornaas MA, Teige B, Hovda KE, Ekeberg O, Heyerdahl F, Jacobsen D. Fatal poisonings in Oslo: a one-year observational study. BMC Emerg Med. 2010;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–257. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant BF, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1205–1215. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC. Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):64–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]