Abstract

Background

Hyperthermia is a type of cancer treatment in which body tissue is exposed to high temperatures to damage and kill cancer cells. It was introduced into clinical oncology practice several decades ago. Positive clinical results, mostly obtained in single institutions, resulted in clinical implementation albeit in a limited number of cancer centres worldwide. Because large scale randomised clinical trials (RCTs) are lacking, firm conclusions cannot be drawn regarding its definitive role as an adjunct to radiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced cervix carcinoma (LACC).

Objectives

To assess whether adding hyperthermia to standard radiotherapy for LACC has an impact on (1) local tumour control, (2) survival and (3) treatment related morbidity.

Search methods

The electronic databases of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), (Issue 1, 2009) and Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Groups Specialised Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, online databases for trial registration, handsearching of journals and conference abstracts, reviews, reference lists, and contacts with experts were used to identify potentially eligible trials, published and unpublished until January 2009.

Selection criteria

RCTs comparing radiotherapy alone (RT) versus combined hyperthermia and radiotherapy (RHT) in patients with LACC.

Data collection and analysis

Between 1987 and 2009 the results of six RCTs were published, these were used for the current analysis.

Main results

74% of patients had FIGO stage IIIB LACC. Treatment outcome was significantly better for patients receiving the combined treatment (Figures 4 to 6). The pooled data analysis yielded a significantly higher complete response rate (relative risk (RR) 0.56; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39 to 0.79; p < 0.001), a significantly reduced local recurrence rate (hazard ratio (HR) 0.48; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.63; p < 0.001) and a significantly better overall survival (OS) following the combined treatment with RHT(HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.99; p = 0.05). No significant difference was observed in treatment related acute (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.30 to 3.31; p = 0.99) or late grade 3 to 4 toxicity (RR 1.01; CI 95% 0.44 to 2.30; p = 0.96) between both treatments.

Authors' conclusions

The limited number of patients available for analysis, methodological flaws and a significant over‐representation of patients with FIGO stage IIIB prohibit drawing definite conclusions regarding the impact of adding hyperthermia to standard radiotherapy. However, available data do suggest that the addition of hyperthermia improves local tumour control and overall survival in patients with locally advanced cervix carcinoma without affecting treatment related grade 3 to 4 acute or late toxicity.

Plain language summary

Combined use of hyperthermia and radiation therapy for treating locally advanced cervix carcinoma

Cure of cervix carcinomas can be achieved by complete surgical removal of the tumour or destruction of the tumour or by means of radiation. If the tumour has grown beyond the boundaries of the cervix or has reached a size larger than 4 cm in diameter it is designated as locally advanced cervix carcinoma. For such tumours surgery alone is considered insufficient and radiotherapy will be chosen instead. However, the larger the tumour, the smaller the chance that radiotherapy alone will be able to cure the tumour. In several clinical studies it was found that the respons of these tumours to radiotherapy was improved by adding hyperthermia. Hyperthermia is a type of cancer treatment in which body tissue is exposed to high temperatures (i.e. around 42 to 43 degrees Celcius during one hour) to damage and kill cancer cells.. This temperature is in itself able to kill tumour cells under certain conditions and also increases the lethal effect of radiation on tumour cells. can However, the results observed with this treatment were not consistent in subsequent clinical studies. Therefore we analysed the results of all clinical studies published so far comparing the treatment results of radiotherapy alone with the results of combined radiotherapy and hyperthermia in patients with locally advanced cervix carcinoma. The results do suggest a better outcome for patients treated with the combination of radiotherapy with hyperthermia. Thus following treatment a complete disappearance of the tumour was observed more regularly, regrowth of the tumour at the site of origin during follow up was observed less frequently and more patients were still alive at last follow‐up. Treatment related side effects were not increased by the addition of hyperthermia to standard radiotherapy. However, the number of patients included in the clinical studies analysed is limited as the majority of patients had stage IIIB disease. The authors therefore conclude that hyperthermia may provide a clinically relevant improvement in treatment outcome for patients with locally advanced cervix carcinoma, in particular patients with stage IIIB disease. Additional clinical data are needed to warrant its use for all patients with locally advanced cervix carcinoma.

Background

Description of the condition

For many years radiotherapy alone has been the treatment of choice in patients with LACC. Spread to the para‐aortic lymph nodes has been recognised as the single most important prognostic factor (Fyles 1995; Stehman 1991). Nevertheless pelvic tumour control is a pre‐requisite for cure (Haie 1988; Rotman 1995). Perez et al reported overall pelvic recurrences in 14%, 41%, 41% and 72%, whereas distant recurrences only were found in 12%, 18%, 16% and 21% of 1499 patients with FIGO stage I, II, III and IVA disease treated with radiotherapy (Perez 1998). Similarly, Horiot et al reported pelvic recurrences in 6%,17%,43% and 56% of 1383 patients with stage I, II, III and IVA, respectively, treated with radiotherapy (Horiot 1988).

Description of the intervention

Since 1987 the results of six randomised clinical trials (RCTs) have been published concerning the combined treatment of radiotherapy with hyperthermia (RHT) in patients with cervix carcinoma (Chen 1997; Datta 1987; Harima 2001; Sharma 1991; van der Zee 2000; Vasanthan 2005). Local tumour control and overall survival appeared to be improved by the addition of hyperthermia, although clinical observations were not unanimous. Possible explanations for the discrepancy may be found in the patient selection (e.g. with respect to stage or tumour volume) and other confounding factors such as treatment parameters (e.g. overall treatment time and hyperthermia technique). Therefore, the magnitude of any beneficial effect as well as the proper selection of patients for any combined treatment remains to be demonstrated.

How the intervention might work

In LACC the pelvis is the most common site of failure after treatment with radiotherapy. Several tumour characteristics have been related to the risk of pelvic failure following radiotherapy (Eifel 1994; Fyles 1995; Haensgen 2001; Hockel 1993; Horiot 1988; Lanciano 1991; Mendenhall 1984; Perez 1998; Stehman 1991; Stehman 1994; Thomas 2001; Tsang 1995; Werner 1995; West 1995). Probably the single most important of these is tumour volume (Fyles 1995; Perez 1998; Tsang 1995). Although tumour hypoxia is suggested to be an independent prognostic factor by some (Hockel 1999; Vaupel 2001) both animal (De Jaeger 1998; Khalil 1995; Milross 1997) and human data (Fyles 1998) have demonstrated an association between tumour volume and tumour hypoxia. Thus with increasing tumour volume, tumour necrosis increases and as a result oxygenation status worsens (De Jaeger 1998; Khalil 1995; Milross 1997). Anaerobic glycolysis will thus increase and consequently tissue pH will decrease. At acid pH cells become more sensitive to hyperthermia whereas under these hypoxic conditions cells will be less sensitive to radiotherapy. It's under these circumstances that a therapeutic gain of hyperthermia is to be expected. In addition to a direct cytotoxic effect of hyperthermia radiation‐induced DNA damage repair is inhibited by hyperthermia. Indirectly radiosensitivity will improve as tumour blood flow will increase thus improving tumour oxygenation.

Why it is important to do this review

The potential benefit of combining hyperthermia with radiotherapy in cervix carcinomas was established several decades ago (Brady 1976), but RCTs are scarce. Furthermore, the number of patients included in the few available RCTs is small and are inconsistent regarding the beneficial effect of hyperthermia (Harima 2001; van der Zee 2000; Vasanthan 2005). Of importance also are the fundamental differences that exist in the heating techniques used, thus prohibiting any firm conclusion regarding the therapeutic benefit. The majority of published data deal with technical developments and do not provide treatment results. Despite these drawbacks, however, overall clinical data on the combined use of radiotherapy and hyperthermia suggest a therapeutic gain as compared to single modality treatment (Dinges 1998; Harima 2001; Hornback 1986;; van der Zee 2000; Vasanthan 2005). Therefore a systematic analysis on this treatment modality is required.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive and reliable summary of the effect of hyperthermia on LACC when applied concomitantly with radiotherapy. The specific aim is to review all prospective RCTs (phase II and phase III) which compare the effectiveness of combined hyperthermia and radiotherapy (RHT) with radiotherapy alone (RT) in patients treated for LACC.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs (phase II or III).

Types of participants

Patients of any age with histologically proven LACC and with a WHO performance status 0 to 2 (WHO 1979). Cervical cancers with a central diameter equal or larger than 4 cm and/or FIGO stage IIB to IVA are considered locally advanced. Studies with less than 20 patients were excluded.

Types of interventions

Any regimen of radiotherapy for uterine cervical carcinoma consisting of (generally considered) curative doses of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) with or without brachytherapy (BCT) given concurrently or not with hyperthermia. Only studies which used a minimum temperature of 40o celsius for hyperthermia were included. In case of concomitant use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy studies were included when hyperthermia was the only treatment variable. In that case no further distinction was made between different chemotherapy schedules.

Studies in which it was not possible to separate data on patients receiving combined hyperthermia plus radiotherapy (RHT) versus radiotherapy alone (RT), even after contacting the authors, were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The following clinically relevant outcomes were studied:

Complete tumour response (CR) at two months (that is no evidence of disease as assessed with clinical examination and/or any imaging technique).In cervical carcinoma a CR following radiotherapy is predictive for a durable pelvic tumour control.

Local tumour recurrence (LR)

Overall Survival (OS)

Grade 3 to 4 acute toxicity (Tox acute; i.e. treatment related toxicity occurring during and/or lasting up to six weeks following treatment) and grade 3 to 4 late toxicity (Tox late; i.e. treatment related toxicity lasting or occurring more than six months after treatment).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this review we identified the relevant trials in any language through electronic searches of the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2009)

Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Groups Specialised Register (beginning to present)

MEDLINE (1966 to present)

EMBASE (1974 to present)

CINAHL (1982 to present)

Furthermore, various trial databases were searched for the identification of recent completed and ongoing trials (metaRegister of Controlled Trials, Cancer Research UK, Cancer.gov, The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trials Database). All studies identified until January 2009 were included in the present study.

For search strategies used see Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3

Search strategies have been developed and executed by the author team.

Searching other resources

Handsearching was performed in the following journals; International Journal of Radiation, Oncology, Biology and Physics,Radiotherapy and Oncology; Journal of Clinical Oncology; Clinical Oncology and the International Journal of Hyperthermia. In addition, published abstracts of the ASTRO, ESTRO and ESHO conference proceedings of the last three years were screened. We scrutinised reference lists from identified studies and reviews for additional studies. Colleagues, collaborators and other experts in the field were asked to identify missing and unreported trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts of reports identified by electronic searches or handsearching were assessed to determine if they meet the eligibility criteria by three independent review authors (CVZ, DDH, LL). In a consensus meeting (DDH, GVM, JB, LL) discrepancies were discussed. Furthermore, if necessary the full journal papers were screened to identify study characteristics.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (DDH, LL) screened the included studies for methodological quality according to pre‐determined criteria (Assessment of risk of bias in included studies), the treatment characteristics (radiotherapy, hyperthermia, chemotherapy) and the results of outcome measures (Types of outcome measures). For time to event (OS or local tumour recurrence) data, we extracted the log of the hazard ratio [log(HR)] and its standard error from trial reports; if these were not reported, we estimated them from other reported statistics using the methods of Parmar 1998. We abstracted site of recurrence, where possible. For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. complete tumour response and adverse events), we extracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed per endpoint, in order to estimate a risk ratio. We abstracted adverse events by grade of toxicity. The time points at which outcomes were collected and reported were noted.

In addition, the following data were collected from the manuscript: identifiers (authors, title of publication, journal name and citation), tumour characteristics (recurrent, primary, inoperable, metastasis and maximum tumour diameter), baseline characteristics of study population (age, WHO performance status at the time of randomisation, initial disease stage), treatment allocated and number of patients randomised. The results and discrepancies of the data extraction were discussed in different meetings (DDH, GVM, JB, LL). The quality of the hyperthermia treatment of the different studies was determined in a consensus meeting (CVZ, DDH, GVM, JB, LL).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias was assessed using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions (Higgins 2008) addressing the following six domains:

Sequence generation (1), allocation concealment (2), blinding (3), incomplete outcome data (4), selective reporting of outcomes(5) and other potential threats to validity (6).

Measures of treatment effect

A weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across studies was computed for the study outcomes. The risk ratio (RR) was used as the effect measure. For time‐to‐event outcomes such as survival analysis, the HR was used as effect measure. For these analyses, p‐values and total events were used and the randomization ratio was 1:1 (Tierney 2007). Tierney 2004 was used to facilitate the estimation of HRs from published summary statistics or data extracted from Kaplan‐Meier curves.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data; if only imputed outcome data were reported, we planned to contact trial authors to request data on the outcomes only among participants who were assessed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Chi‐square heterogeneity tests were used to test for statistical heterogeneity among trials. Since we anticipated that the trial results were heterogeneous, all analysis were performed using a random‐effects model.

Results

Description of studies

See:Characteristics of Included studies;Characteristics of Excluded studies.

Results of the search

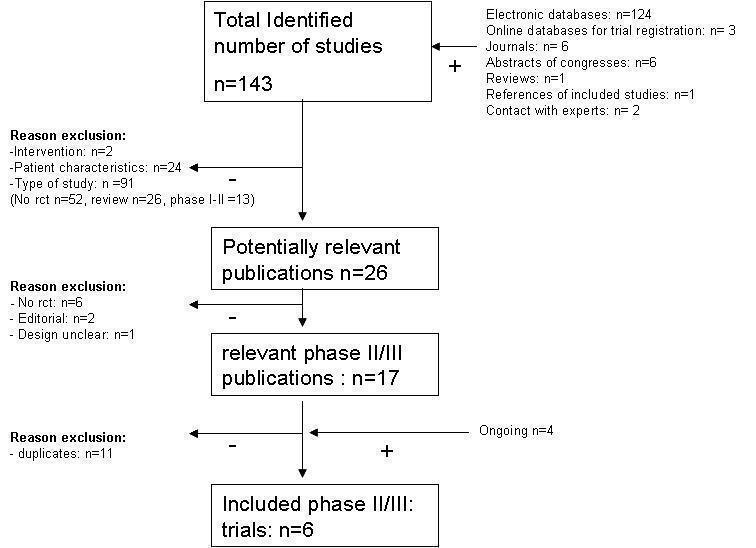

The process of selecting the included studies for this review is summarized in Figure 1 . Of the 143 published abstracts that were selected by the performed search, we excluded 117 abstracts. The studies described in these abstracts did not evaluate the interventions of interest (n = 2) or did not contain data of cervical patient characteristics (n = 24). In addition, a total of 91 abstracts were excluded due to the study characteristics presented, i.e. no RCT (n = 52), a review (n = 26) or a phase 1‐2 trial (n = 13). Of the remaining 26 abstracts the full journal papers were screened (if available). After screening, 6 studies appeared to be not randomised, 2 were editorial papers and 1 had an unclear design. The remaining 6 different trials (11 published papers: Franckena 2008; Chen 1997; Datta 1987; Harima 2000; Harima 2001; Sharma 1989; Sharma 1991; van der Zee 2000; van der Zee 2001; van der Zee 2002; Vasanthan 2005) were of RCTs (Phase 2 or 3) reporting radiotherapy together with a hyperthermia treatment (RHT) in one arm and radiotherapy only in the other arm. Of notice, the study of Chen et al included 120 patients with 4 treatment arms of which 2 treatment arms contained concomitant chemotherapy (Chen 1997). Since this analysis aimed to investigate the additional effect of hyperthermia on standard radiotherapy, we decided not to include the patients treated with concomitant chemotherapy in the pooled data analysis. Four ongoing studies that were identified from abstracts of congresses, online databases for trial registration and contact with experts (see table Characteristics of included studies) are not included in the present analysis.

1.

Search Flow

Included studies

In 1987 Datta et al reported their results obtained in 53 patients with squamous cell cervical carcinoma, FIGO stage IIIB (Datta 1987). 64 Patients were randomly assigned to standard treatment only or combined treatment with local hyperthermia. Eleven patients were either lost to follow‐up or received incomplete treatment leaving 53 assessable patients (RT n = 26; RHT n = 27) ). No information concerning actually delivered therapy was provided by the authors. RHT yielded superior treatment results, i.e. 58% (15 out of 26) versus 74% (20 out of 27) CR, 46% (12 out of 26) versus 67% (18 out of 27) pelvic failure free survival and 27% (7 out of 26) versus 59% (16 out of 27) DFS at 2 years. The authors reported no increase of treatment related morbidity although detailed information was not provided.

In 1991 Sharma et al reported their results obtained in 50 patients with cervical carcinoma FIGO stage II‐IIIB (Sharma 1991). Fifty patients were randomly assigned to RT or RHT. Two patients in each group were lost to follow‐up whereas another 4 patients were not assessable for local tumour control after a minimal follow‐up period of 18 months leaving 42 patients (i.e. 22 RT and 20 RHT group). No information concerning actually delivered therapy was provided by the authors. Strictly local tumour control was evaluated, i.e. any pelvic side wall or distant recurrence was ignored. No details are provided on the duration of follow‐up. RHT yielded superior treatment results, i.e. 50% (11 out of 22) versus 30% (6 out of 20) LR at 18 months for patients treated with RT and RHT, respectively. The authors reported no increase of treatment related morbidity although detailed information was not provided for late toxicity.

In 1997 Chen et al reported their results obtained in a study including 120 patients with cervical carcinoma, FIGO stage IIB ‐IIIB (Chen 1997). One hundred and twenty patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 treatment groups, no detailed information concerning the randomisation procedure was provided. Treatment consisted of RT, RHT, radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy (CRT) and radiotherapy combined with both hyperthermia and chemotherapy (TRIPLE). Vaginal applicators were used for the hyperthermia intervention but no further details were provided regarding the hyperthermia technique. No information concerning actually delivered therapy was provided by the authors. Treatment results were not significantly different, i.e. 46% (14 out of 30) versus 60% (18 out of 30) complete remission for the RT and RHT group. The authors reported no increase of acute treatment related rectal and bladder morbidity between the treatment groups although detailed information about the grade of toxicity was not provided. For the pooled data analysis we excluded those patients treated with concomitant chemotherapy (n=60).

In 2000 van der Zee et al reported their results obtained in a multicenter study including 114 patients with cervical carcinoma FIGO stage IIB‐IVA (van der Zee 2000). Twenty‐six patients did not complete radiotherapy treatment as planned because of insufficient tumour regression (n = 8 and n = 3), exceeding normal tissue dose constraints (n = 1 and n = 2), development of metastatic disease (n = 3 and n = 0), inability to access the cervical canal (n = 1 and n = 2), a cervical stump tumour (n = 0 and n = 2), intercurrent death (n = 1 and n = 1) and unknown (n = 3) in the control and experimental group, respectively. Median follow up was 43 months. RHT yielded superior treatment results i.e. 57% (32 out of 56) versus 83% (48 out of 58) CR, 41% versus 61% pelvic failure free survival and 27% versus 51% OS at 3 years for patients treated with RT and RHT, respectively. No difference in acute and late grade 3 to 4 treatment related rectal and/or bladder morbidity was observed.

In 2001 Harima et al reported their results obtained in a study including 40 patients with cervical carcinoma FIGO stage IIIB (Harima 2001). Mean follow‐up was 25 (3.5 to 60.1) and 36 (5.9 to 64.3) months for the RT and RHT group, respectively. RHT yielded superior treatment results, i.e. 50% (10 out of 20) versus 80% (16 out of 20) CR; 50% versus 20% pelvic failure rate; 45% versus 64% DFS and 48% versus 58% OS at 3 years for patients treated with RT and RHT, respectively. Toxicity was not significantly different between treatment groups. However, in contrast to the RT group where no acute or late toxicity of any grade was observed, in the RHT group 1 patient had grade 3 acute bowel toxicity (RTOG score, Rubin 1995) and 2 patients developed grade 3 late bowel toxicity (obstructive colonic ileus and sigmoid‐ileum fistula) after 1.5 and 2 years after treatment.

In 2005 Vasanthan et al reported their results obtained in a multicenter study in 110 patients with cervical carcinoma FIGO stage IIB ‐IVA (Vasanthan 2005). Median follow‐up was 15.7 months for all patients and 17.2 months for surviving patients. Treatment results did not differ between RT and RHT groups. A subgroup analysis in 56 patients with stage IIB cervical carcinoma yielded a significantly worse survival for the RHT group whereas local control was similar for the 2 treatment groups. No details are provided concerning the cause of death or the location of disease recurrence. No significant difference in acute or late toxicity was observed. Grade 3 acute toxicity was observed only in 1 patient treated with RHT (grade 3 blister). Grade 3 bowel toxicity was equally distributed between treatment groups (n = 2 per group). One grade 4 bowel toxicity was observed in a patient treated with RT.

Quality of treatment

Radiotherapy

In general, state of the art treatment of LACC requires adequate EBRT combined with brachytherapy. Thus, EBRT doses between 45 to 50 Gy and cumulative doses between 70 to 90 Gy to 'Point A' are considered standard. Reported radiation doses delivered do not provide any information concerning the adequacy of tumour dose delivery. Except for the Datta study (Datta 1987), all standard radiotherapy protocols included combined treatment with EBRT and brachytherapy. To study the beneficial effect of any additional intervention to standard treatment ideally requires strictly standardized treatment protocols. Not surprisingly, taken the life span and geographical distribution of the 6 studies published, standard treatment varies significantly. Moreover, except for one study (Harima 2001) EBRT was not standardized within each study. Strictly adhering to the predefined quality criteria would mean that only three studies using hyperthermia treatment would qualify as adequate for review analysis. However, standard radiotherapy in these studies varied as well and would result in cancellation of the review. Taking this into account we decided to accept the variation in radiation therapy and hyperthermia techniques as well as the lack of description of the quality criteria in the manuscripts leaving 'randomised clinical study, including at least 20 patients' as major selection criterion. In doing so, we do realize that any outcome based on this analysis can only be suggestive and not conclusive.

Hyperthermia

The quality of the hyperthermia treatments is difficult to assess from the published information. Dose‐effect relationships have been established for several hyperthermia dose parameters derived from the measured temperatures and the duration of heating, and taking into account the temperature distribution. In clinical practice, however, the number of thermometry sites is limited and in cervical cancer the thermometry probes are usually placed near the centre of the tumour. The temperature data are therefore not informative on what the hyperthermia dose has been in the entire tumour volume (van der Zee 2008). Other studies indicate that the applied energy distribution in the tumour volume can be used as a quality indicator (van der Zee 2008). The energy distribution can be estimated from the information provided in the publications. In five studies, electromagnetic (EM) radiation was used for heating. Chen et al used an intravaginal applicator with an unspecified source of energy, which may have been electromagnetic radiation as well. EM radiation was applied radiatively or capacitively (Chen 1997). Van der Zee et al used three different radiative EM systems with similar energy depositions in pelvis‐sized phantoms (van der Zee 2000).

With EM radiation at a frequency of 70 to 120 MHz, energy input from around the pelvis and the use of interference, the energy is deposited widely in the pelvic region (Gellermann 2005; Sreenivasa 2003). In the other studies, capacitive heating systems were used. With capacitive heating (8 to 27 MHz) between two large electrodes placed opposite on the patient's skin it is also possible to get energy deposition widely in the pelvic region, provided there is an appropriate patient selection and treatment procedure (van der Zee 2005). Subcutaneous fat tissue is preferentially heated by capacitive heating and must be cooled to allow for sufficient energy input into deeper seated tissues. Superficial skin cooling can limit the temperature increase in subcutaneous fat to an acceptable level to a depth of approximately 2 cm (Rhee 1991). With thicker subcutaneous fat layers, the high temperature in the deeper subcutaneous fat will limit the total power input. Further more, when a smaller (intravaginal) electrode is used in combination with one or two large external electrode(s) there will be a steep gradient of energy deposition with the maximum around the small electrode. The energy level normalized to maximum will fall below 25% within 1 to 2 cm from the intravaginal electrode (Hiraki 2000). With capacitive heating using an intravaginal electrode, only the central part of the tumour can be expected to be heated to therapeutic temperatures.

Datta 1987 Hyperthermia was given twice weekly before radiotherapy. The total number of treatments was not reported, it could have been 12 during 6 weeks of EBRT. The duration per treatment was 15 to 20 minutes after reaching a temperature of approximately 42.5°C, measured in the cervical canal. Hyperthermia was induced by a 27 MHz capacitive system with two external electrodes. The authors do not report subcutaneous fat thickness as an eligibility criterion, nor skin cooling, nor the applied power.

Sharma 1991 Hyperthermia was given 3 times per week for a total of 12 treatments of 45 minutes duration, before radiotherapy. A 27 MHz capacitive heating system was used with a large external and an intravaginal electrode. Temperatures were measured by a thermocouple attached to the intravaginal electrode. In most patients, the intravaginal temperature was 43°C for 30 minutes.

Chen 1997 Hyperthermia was given twice weekly after radiotherapy for a total of 6 treatments of 45 minutes at a temperature of 42° with an intravaginal technique. Further details of treatment are not reported.

van der Zee 2000 Hyperthermia was applied by three centres which all used a radiative hyperthermia system. Hyperthermia was given once a week after radiotherapy, for a total of 5 treatments of 60 minutes after reaching 42°C, or maximum 90 minutes. The mean power input and achieved intraluminal (rectal, bladder and vaginal) temperatures were reported by the centre recruiting the most patients and were reported separately: average 706 Watts and 40.6°C (Fatehi 2007).

Harima 2001 Hyperthermia was given once a week after RT, for a total 3 treatments of 60 minutes duration. Hyperthermia was induced with the Thermotron 8 MHz capacitive system with two external electrodes. Patients with subcutaneous fat layer of less than 4 cm were eligible.The authors do not report to have used pre‐cooling. The applied power was 800 to1500 W. Intratumour temperature measurements were done with 4‐point thermocouple probes; an average temperature of 40.6°C was achieved.

Vasanthan 2005 Five centres participated in this study. Hyperthermia was given once weekly before or after radiotherapy, for a total of 5 treatments of 60 minutes duration.

The description of applied heating techniques is incomplete. All centres used a 8 MHz capacitive heating system with, probably in the majority of patients, an intravaginal electrode (van der Zee 2005). A subcutaneous fat thickness of up to 3 cm was accepted; pre‐cooling of skin was reported by only one centre. The level of power input was reported by only one centre: a mean of 520 W, which is relatively low. Centrally measured average temperatures ranged between 38.1 and 42°C.

The hyperthermia techniques using radiative electromagnetic heating or capacitive heating with external electrodes only can be considered adequate (Datta 1987; Harima 2001; van der Zee 2000). In the study of Sharma et al the effect on the central tumour was the main endpoint, for which the used intravaginal heating can be considered adequate (Sharma 1991). In the studies by Chen et al and Vasanthan et al the applied intravaginal heating (in the majority of patients) must be considered inadequate for treatment of the advanced tumours included in their studies (Chen 1997; Vasanthan 2005).

Excluded studies

From the retrieved studies, eight studies were excluded for this review mainly because of the used study design (El Sharouni 1997; Fujiwara 1987; Gupta 1999; Hasegawa 1989; Hornback 1986; Kohno 1990). One study was not assessable due to limited data (Li 1993) and one study could not be included because the trial is still ongoing (Prosnitz 2002).

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies is shown in the table 'Characteristics of included studies' and is summarized in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

All six included studies reported on a randomisation process. In one study (Chen 1997) allocation concealment might be questionable. Although there was no blinding in any study, this is unlikely to affect outcome. All six studies were wihtout missing outcome data. No other problems were detected in any of the six studies that might have introduced a serious risk of bias. However, several other issues have to be considered. Of importance, uniformity in treatment was far from optimal, both for hyperthermia and radiotherapy. For example in hyperthermia the sequencing of radiotherapy and hyperthermia and the interval between radiotherapy and hyperthermia differed between and within (Vasanthan 2005) the studies. Similarly the radiation technique, the total radiation dose applied and overall treatment time differed between and within the studies (van der Zee 2000; Vasanthan 2005). For the different outcome measures only three or four out of six studies can be used for pooled data analysis due to the lack of reported p‐values. Finally, overall the number of patients included in these six studies is small whereas the majority (i.e. 74%) had FIGO stage IIIB LACC.

Effects of interventions

Complete response

Using complete tumour response at the end of treatment as endpoint in the pooled data analysis including 267 study patients (Datta 1987; Chen 1997; van der Zee 2000; Harima 2001) yields a significantly better treatment outcome following RHT (RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.79); p < 0.001; Figure 4; Analysis 1.1).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 RT + HT versus RT: all studies, outcome: 1.1 complete tumour response.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: RT + HT versus RT: all studies, Outcome 1: complete tumour response

Local recurrence

Using local recurrence as endpoint in the pooled data analysis including 264 study patients (van der Zee 2000; Harima 2001; Vasanthan 2005) yields a significantly reduced local recurrence rate (HR 0.48 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.63); p < 0.001; Figure 5; Analysis 1.2).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 RT + HT versus RT: all studies, outcome: 1.2 local tumour recurrence_HR.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: RT + HT versus RT: all studies, Outcome 2: local tumour recurrence_HR

Overall survival

Using overall survival as endpoint in the pooled data analysis including 264 study patients (van der Zee 2000; Harima 2001; Vasanthan 2005) yielded a significantly better survival for the combined treatment group (RHT) (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.99; p = 0.05; Figure 6; Analysis 1.3).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 RT + HT versus RT: all studies, outcome: 1.3 overall survival_HR.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: RT + HT versus RT: all studies, Outcome 3: overall survival_HR

Toxicity

Using acute toxicity as endpoint in the pooled data analysis including 310 study patients (Sharma 1991; van der Zee 2000; Harima 2001; Vasanthan 2005) yielded no difference in acute treatment related toxicity between both treatment groups (RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.30 to 3.31); p = 0.99; Figure 7; Analysis 1.4). Similarly, the pooled data analysis using late toxicity as endpoint including 264 study patients (van der Zee 2000; Harima 2001; Vasanthan 2005) yielded no difference in late toxicity between both treatment groups (RR 1.01 (CI 95% 0.44 to 2.30); p = 0.98.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 RT + HT versus RT: all studies, outcome: 1.7 toxicity (acute and late).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: RT + HT versus RT: all studies, Outcome 4: toxicity (acute and late)

Discussion

The results of the present analysis with respect to the endpoints studied, i.e. complete response rate following treatment, local recurrence, OS and treatment related toxicity grade 3 to 4 indicates a significant improvement of local (pelvic) tumour control and overall survival for the combined treatment modality (RHT) whereas acute and late toxicity was not significantly different between both treatment groups. In four of six studies (Datta 1987; Harima 2001; Sharma 1991; van der Zee 2000) a significantly improved treatment outcome was observed by adding hyperthermia to standard radiotherapy, whereas in two studies no significant difference between both treatments was observed (Chen 1997; Vasanthan 2005).

In contrast, in one study (Vasanthan 2005) an inferior survival was observed in a subgroup of patients with FIGO stage IIB treated with RHT, although no further information is provided on the cause of death, whereas local tumour control was similar for both treatment groups. Sharma et al report on an increased rate of distant metastases in the RHTgroup although the difference is not significant and no survival data are provided (Sharma 1991). Of interest, the patient population differed significantly between these studies as the percentage of patients with FIGO stage IIIB disease varied between 38 to 77 % (Chen 1997; Vasanthan 2005) and between 70 to 100% (Datta 1987; Harima 2001; Sharma 1991; van der Zee 2000) in the two studies showing no difference and the four studies showing a beneficial effect of hyperthermia.

Regarding treatment related toxicity, all studies reported treatment related toxicity. Three studies (Datta 1987; Sharma 1991; Chen 1997) found no effect on normal tissue toxicity, although no further details were provided. Two trials (van der Zee 2000;Vasanthan 2005) reported no increaseof acute or late toxicity. One trial (Harima 2001) observed an increased late bowel toxicity in 2 out of 20 patients treated with RHT as compared to 0 out of 20 patients treated with RT.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Taken the limited number of patients available for this analysis, the over‐representation of FIGO stage IIIB disease and the methodological flaws as discussed, it is not possible to draw definite conclusions regarding the beneficial effect of hyperthermia added to standard radiotherapy. Treatment related severe toxicity, i.e. grade 3 to 4 seems not to be affected by the addition of hyperthermia to standard radiotherapy treatment. However, the available data do suggest that superior local tumour control rates and overall survival can be achieved in patients with LACC by adding hyperthermia to standard radiotherapy. Although the available data mainly apply for patients presenting with FIGO stage IIIB disease, radiobiological considerations suggest a possible benefit for its use in other locally advanced stages as well. Based on the results of several recent RCTs investigating the role of adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy this treatment combination is currently considered standard in LACC. Considering the results of this analysis and the finding that the effect of adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy on survival seems to decrease with increasing tumour stage hyperthermia should be considered as an alternative in case chemotherapy is contra‐indicated, especially in higher tumour stages.

Implications for research.

Taken the therapeutic benefit obtained, that is almost doubling of a durable local control with an associated increase in overall survival, without affecting treatment associated toxicity and the relatively low costs per patient, a limited number of clinical restrictions for its application, further investigation of the role of hyperthermia in a large scaled randomised trial is warranted. In case of a substantiated therapeutic gain this treatment modality should become available to all patients with this life threatening but potentially curable disease.

Feedback

Sergey Roussakow, 18 November 2021

Summary

The review is heavily biased in result of (1) inadequate bias risk assessment, (2) misleading statements and (3) concealment of negative information.

1) The statement “EBRT doses between 45 to 50 Gy and cumulative doses between 70 to 90 Gy to ’Point A’ are considered standard” is incorrect and misleading.

At first, correctly it should be “EBRT doses between 45 to 50 Gy to ’Point A’ and cumulative doses between 70 to 90 Gy are considered standard”. This is not correct statement because with 45‐50 Gy dose to ‘Point A’, it’s impossible to reach cumulative dose 70‐90 Gy (dose to parametrium never exceeds 25 Gy, usually it is much less). All the radiotherapy (RT) guidelines recommend cumulative dose >80‐90 Gy [1] with >70 Gy to ‘Point A’ (usually 75‐85 Gy [2]). Perez et al. [3] showed that dose ≤70 Gy to tumor mass significantly reduces the efficacy and is considered inadequate. 40‐50 Gy to ‘Point A’ is undoubtedly inadequate dose.

2) This misleading statement is to conceal the critical defect of the main positive van der Zee[4] and Harima [5] trials. Both trials used inadequate comparator – low‐dose RT (≤60 Gy to ‘Point A’; though 82.2 Gy cumulative was used in Harima trial, dose to ‘Point A’ was only 60.6 Gy (30.6 Gy EBRT + 30 Gy of brachytherapy), while 21.6 Gy dose was applied to parametria with central shielding), though the best or standard treatment should be used as a control in clinical trials.

3) As a result, long‐term overall survival in van der Zee trial was twice worse than in RT‐trials with adequate RT dose (23% vs ≈45%) and the best OS in the termoradiotherapy (TRT) arm (43%) was also lower or equal to that of standard RT studies (everything is described in details here [6]).

Therefore, both trials have incorrect design and are clinically insignificant because the same or better result could be received with standard RT with lower costs and labor and lower toxicity.

4) In Harima trial, pre‐selection of older patients is obvious (selection bias): the median age was near 65 years and these were previously untreated patients, while the average age of the first diagnosis in Japan is 54.6 years [7]. It’s impossible to obtain 10‐year older sample of first time diagnosed patients randomly (the better local control after TRT in older patients is well known fact).

5) Van der Zee trial also has incorrect design. In fact, it combined two studies based on Amsterdam Medical Center (AMC) and University Hospital Rotterdam (UHR): whereas AMC trial was monocentral, UHR collected patients also from 9 other RT centers. As a result, two groups had different RT‐HT sequencing: if in AMC HT followed after RT in 1 hour, in UHR the usual delay was 3‐4 hours because of logistics. As interval of RT thermal modification doesn’t exceed 3 hrs, it was a concomitant instead of the combined treatment in UHR arm. Additionally, the groups used different HT‐equipment: BSD2000 system in UHR, 4‐waveguide applicator system in AMC and TEM applicator in Utrecht. The statement “Van der Zee et al used three different radiative EMsystems with similar energy depositions in pelvis‐sized phantoms” is misleading: according to Seegenschmiedt [8], their thermal efficiency differs 2‐3 times in clinical setting. These two studies with quite different protocols and equipment should be analyzed separately, but there are no separate data for AMC and UHR; even the number of patients in these two arms is unknown (incorrect analysis and incomplete data presentation).

6) Safety reporting in van der Zee trial seems to be incomplete and biased: synthesis of data on side effects and refusal of treatment gives much higher toxicity rate than it is reported [6] (concealment of negative information).

7) Therefore, the both trials should be excluded in view of incorrect design (inadequate comparator), selection bias (Harima), concealment of negative information, incorrect analysis and incomplete data presentation (van der Zee).

8) Vasanthan [9] and Chen [10] trials were negative.

9) Both remaining Indian trials (Datta [11], Sharma [12]) are old enough and of low quality.

10) Datta trial seems to be rather controlled than randomized.

11) The information provided concerning Sharma trial is incomplete: there were 4‐time more distant metastases in HT arm (4 vs. 1 in RT control) – this information is concealed.

12) After exclusion of Harima and van der Zee trials, two negative trials vs. two positive trials remain. Vasanthan negative trial of highest evidence level (multicenter international phase III RCT) shown no local effect of HT with negative effect to survival (statistically significant at IIB stage patients). Chen negative trial showed no local effect and no effect to survival. Both positive trials are of low reliability and show the higher rate of complete remission without effect to survival, but with progress of metastases (Sharma). Therefore, the negative impact of HT outweighs.

13) With respect to the above, the conclusion “However, available data do suggest that the addition of hyperthermia improves local tumour control and overall survival in patients with locally advanced cervix carcinoma without affecting treatment related grade 3 to 4 acute or late toxicity” seems to be inadequate.

=====

[1] Colombo N, Carinelli S, Colombo A, Marini C, Rollo D, Sessa C, and on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Ann Oncol (2012) 23 (suppl 7): vii27‐vii32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds268 [2] NCCN Cervical Cancer Guidelines. Ver. I.2015. https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf

[3] Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Chao KSC, Mutch DG, Lockett MA. Tumor size, irradiation dose, and long‐term outcome of carcinoma of uterine cervix. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41(2):307–17 [4] Van der Zee J, Gonzalez‐Gonzales D, Van RGC, Van DJDP, Van PWLJ, Hart AAM. Comparison of radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy plus hyperthermia in locally advanced pelvic tumours: A prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet 2000;355(9210):1119‐25.

[5] Harima Y, Nagata K, Harima K, Ostapenko VV, Tanaka Y, Sawada S. A randomized clinical trial of radiation therapy versus thermoradiotherapy in stage IIIB cervical carcinoma. International Journal of Hyperthermia the Official Journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group 2001;17(2):97‐105.

[6] Roussakow S. Critical Analysis of Electromagnetic Hyperthermia Randomized Trials: Dubious Effect and Multiple Biases. Conference Papers in Medicine, 2013, Article ID 412186, 31p.

[7] Ioka A, Tsukuma H, Ajiki W, Oshima A. Influence of age on cervical cancer survival in Japan. Jap J Clin Oncol. 2005; 35(8):464–9.

[8] Seegenschmiedt MH, Fessenden P, Vernon CC, eds. Thermoradiotherapy and Thermochemotherapy. Vol 2: Clinical Applications. Berlin, Sprinder, 1996. ‐ 420 p.

[9] Vasanthan A, Mitsumori M, Park JH, Zhi Fan Z, Yu Bin Z, Oliynychenko P, et al. Regional hyperthermia combined with radiotherapy for uterine cervical cancers: A multi‐institutional prospective randomized trial of the international atomic energy agency. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 2005;61(1):145‐53.

[10] Chen HW, Fan JJ, Luo W. A randomized trial of hyperthermo‐radiochemotherapy for uterine cervix cancer. Chinese Journal of Clinical Oncology 1997;24(4):249‐51.

[11] Datta NR, Bose AK, Kapoor HK. Thermoradiotherapy in the management of Carcinoma Cervix (Stage IIIB): A controlled Clinical Study. Indian Medical Gazette 1987;121:68‐71.

[12] Sharma S, Singhal S, Sandhu AP, Ghoshal S, Gupta BD, Yadav NS. Local thermo‐radiotherapy in carcinoma cervix: improved local control versus increased incidence of distant metastasis. Asia Oceania Journal of Obstetrics and

I agree with the conflict of interest statement below:

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback.

Reply

1) No single golden rule exists regarding the optimum radiation dose delivery in cervix carcinomas (Viswanathan A.N. in Perez and Brady’s Principles and practice of radiation oncology). However, several principles should be respected when treating these patients such as the awareness of an obvious dose‐effect relationship and critical role of brachytherapy (BCT) .

When discussing adequate radiation doses one should take into account the techniques applied (e.g. LDR versus HDR BCT; EBRT with our without central shielding and the type of central shielding used, reporting the dose delivered to point A, which may vary between 50 to 80% of the dose delivered. Last but not least the loading pattern used in BCT and the total activity applied are important issues when trying to compare treatments. In fact, none of these issues is addressed systematically in clinical trials. For sure, treatments with a similar dose to point A can actually deliver largely different dose (‐volumes) to both tumour and organs at risk. Taking these inevitable shortcomings we accepted the surrogate endpoint for reporting radiation doses to cervical carcinomas generally applied in literature, i.e. the dose to point A.

We do agree that the current statement about dose levels to be considered standard is not extensively covering the issue; however it is not incorrect and not misleading. The dose effects reported in literature do apply to the cumulative dose to point A, and more recently the D90 delivered to the high risk CTV. The latter is, however, not applicable to the current Cochrane Analysis taken its time perspective. The dose delivered with EBRT is typically covering the primary tumour (surrogate dose to point A), the parametrium and draining lymphatics. Additional doses to the (residual) macroscopic tumour are applied by means of BCT.

2) A dose to point A of 17 Gy HDR in 2 fractions (van der Zee et al.) or 30 Gy HDR in 4 fractions (Harima et al.) would correspond to an EQD2 dose of 26.2 and 42.9 Gy respectively (a/b =10). Taking the additional EBRT doses of 46‐50.4 Gy and 30.6 Gy, both treatment schedules can thus be considered adequate. In case of the Dutch trial (van der Zee et al) several patients in both treatment arms could not be treated with BCT for technical reasons which are well known in clinical practice.

3) The criticism of the van der Zee trial concerning the poor results in the standard treatment arm as compared to results reported in literature are discussed by the authors.

Of importance, the patient population had several poor prognostic characteristics such as a tumour diameter more than 6 cm in 77% of patients, and clinically suspect lymph nodes in 70% of patients who had an abdominal CT scan. Although they are not included in the FIGO‐stage (except tumour volume in stage IB) the detrimental effect on treatment outcome is well known for both tumour characteristics and may largely explain the poor outcome with radiation therapy only as compared to published results in comparable FIGO‐stages.

4) We don't agree that a difference in mean age at diagnosis of three years between both treatment arms can be considered to be a pre‐selection of older patients. Furthermore, patients diagnosed with cervix carcinoma with effective screening programs are likely to be different from those who present with stage IIIB disease. In addition, we are not aware of any data demonstrating a significant effect of age as predictive factor for treatment outcome following radiotherapy and hyperthermia.

5) The Dutch Deep Hyperthermia Trial was started as two separate studies, which were combined into one trial within two years after opening. Although there were differences between the two studies, the primary research question was the same: whether the addition of hyperthermia to radiotherapy improves clinical outcome, and the only difference between the two treatment arms was whether hyperthermia was included in the treatment plan or not.

There was a difference in treatment schedules: hyperthermia was given 1 hour after radiotherapy in the Amsterdam study and four hours after radiotherapy in the Rotterdam study. The four hour time interval for the Rotterdam study was not based on logistics, but chosen well‐considered. Experimental studies have shown that with a time interval of four hours, there is no risk of increased toxicity, and so no adjustments to radiotherapy were required. Hyperthermia in cancer treatment has multiple effects: direct cell kill, radio and chemosensitisation, changes in blood flow which may influence the sensitivity to radio‐ and chemotherapy, and anti‐cancer immune stimulation. The radiosensitising effect, to which Mr. Roussakow refers, is only part of the effect and still may be present even after a time interval of four hours.

Three different hyperthermia systems were used. The performance of these three systems has been compared in a pelvic size phantom, which comparison demonstrated similar energy distributions [1]. Since with all three systems power input during treatment was increased to maximum patient tolerance, there is no reason to assume that the applied hyperthermia treatments differed between the two studies.

The numbers of patients in the two separate studies have not been reported. What has been reported is that the overall survival between the two treatment groups differed significantly after adjustment in the regression analysis for age, tumour size, and study/institution. It was further reported that the benefit of hyperthermia was seen in the data analyzed separately from each institution [1,2]

6) In the Lancet publication [2], both acute toxicity of hyperthermia, and acute and late toxicity are reported, and the numbers of hyperthermia treatments that the patients received. In the Int J Hyperthermia publication [3], the reasons why patients received fewer than the five planned treatments that were scheduled are reported in more detail. Seven patients received no treatment at all: four refused after initial consent, and in three contraindications were found. Eleven patients had less than four treatments, mostly because refusal. Patients find hyperthermia treatment unpleasant, especially the introduction of the intraluminal thermometry probes and the long duration. The high percentage of patients refusing further treatments probably reflects how well they were informed about the experimental nature of hyperthermia treatment. Since the combination of radiotherapy and hyperthermia became standard treatment for cervical cancer, 93% of the patients received four or five treatments and the main reason for patients receiving fewer than five treatments was logistic difficulties [2].

7) As described above we apparently do not agree.

8) Correct.

9) The time passed since publication of a study was not limited and hence not an exclusion criterion for inclusion in the analysis. Regarding the quality of both studies the risk of bias analysis is comprehensive in this respect.

10) This is merely an interpretation, rather than an observation. As stated by Datta et al. “all cases were randomized and divided into 2 groups”.

11) Indeed the number of metastases observed in both groups differed (i.e. 1/23 versus 4/23 patients)although not significantly. Furthermore, outcome measures taken into consideration for the analysis were complete remission rate, local recurrence rate, overall survival and toxicity. We therefore do not agree that this particular information was concealed.

12) One can argue about the type of trials with the highest evidence level or with most impact on overall effects observed. However, the inherent errors typical for this kind of argument are exactly what the Cochrane review methodology is trying to prevent. Therefore, we prefer to stick to the methods provided by Cochrane. In addition it should be noted that Chen et al do not report survival data in their manuscript.

13) Taken the data published currently and based on the analysis applying the rules dictated by Cochrane, the authors are convinced that the conclusion as stated is still valid.

[1] Schneider CJ et al. Quality assurance in various radiative hyperthermia systems applying a phantom with LED matrix. Int J Hyperthermia 1994;10:733‐747.

[2] Van der Zee J et al. Comparison of radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy plus hyperthermia in locally advanced pelvic tumours: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Lancet 2000;355:1119‐1125.

[3] Van der Zee J and González González. The Dutch Deep Hyperthermia Trial: results in cervical cancer. Int J Hyperthermia 2002;18:1‐12.

Contributors

Dr Ludy Lutgens on behalf on the author team.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 November 2021 | Review declared as stable | A new protocol for this review will be developed in the future to include new Cochrane methodology. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2007 Review first published: Issue 1, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 November 2015 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback and author's response added to the review |

| 22 January 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Revisions incorporated. |

| 24 July 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ruud Houben for his contribution on statistics.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE

#1 RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL in PT #2 CONTROLLED‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL in PT #3 RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIALS #4 RANDOM‐ALLOCATION #5 DOUBLE‐BLIND‐METHOD #6 SINGLE‐BLIND‐METHOD #7 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 #8 (TG=ANIMALS) not (TG=HUMAN and TG=ANIMALS) #9 #7 not #8 #10 CLINICAL‐TRIAL in PT #11 explode CLINICAL‐TRIALS/ all subheadings #12 (clin* near trial*) in TI #13 (clin* near trial*) in AB #14 (singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) near (blind* or mask*) #15 (#14 in TI) or (#14 in AB) #16 PLACEBOS #17 placebo* in TI #18 placebo* in AB #19 random* in TI #20 random* in AB #21 RESEARCH‐DESIGN #22 #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 #23 (TG=ANIMALS) not (TG=HUMAN and TG=ANIMALS) #24 #22 not #23 #25 #24 not #9 #26 TG=COMPARATIVE‐STUDY #27 explode EVALUATION‐STUDIES/ all subheadings #28 FOLLOW‐UP‐STUDIES #29 PROSPECTIVE‐STUDIES #30 control* or prospectiv* or volunteer* #31 (#30 in TI) or (#30 in AB) #32 #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #31 #33 (TG=ANIMALS) not (TG=HUMAN and TG=ANIMALS) #34 #32 not #33 #35 #34 not (#9 or #25) #36 #9 or #25 or #35 #37explode Cervical‐Intraepithelial‐Neoplasia (MeSH all) #38 explode Uterine‐Cervical‐Neoplasms (MeSH all) #39 cervi* #40 cancer or tumor or tumour or malignan* or oncol* or carcinom* or neoplas* or growth or adenom* or cyst* #41 #39 and #40 #42 #37 or #38 or #41 #43 radiother* #44 radiat* #45 explode Radiotherapy (MeSH all) #46 explode Radiotherapy‐Computer‐Assisted (MeSH all) #47 #43 or #44 or #45 or #46 #48 Hyperther* #49 explode Hyperthermia‐Induced (MeSH all) #50 #48 or #49 #51 #42 and #47 and #50 #52 #51and #36

Appendix 2. EMBASE

#34 #33 and #17 #33 #32 and #28 and #23 #32 #31 or #30 or #29 #31 explode "hyperthermic‐therapy" / all SUBHEADINGS in DEM,DER,DRM,DRR #30 explode "hyperthermia‐" / all SUBHEADINGS in DEM,DER,DRM,DRR #29 Hyperther* #28 #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 #27 explode "computer‐assisted‐radiotherapy" / all SUBHEADINGS in DEM,DER,DRM,DRR #26 explode "radiotherapy‐" / all SUBHEADINGS in DEM,DER,DRM,DRR #25 radiat* #24 radiother* #23 # 18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 #22 (cervi*) and (cancer or tumor or tumour or malignan* or oncol* or carcinom* or neoplas* or growth or adenom* or cyst*) #21 cancer or tumor or tumour or malignan* or oncol* or carcinom* or neoplas* or growth or adenom* or cyst* #20 cervi* #19 explode "uterine‐cervix‐tumor" / all SUBHEADINGS in DEM,DER,DRM,DRR #18 explode "uterine‐cervix‐carcinoma‐in‐situ" / all SUBHEADINGS in DEM,DER,DRM,DRR #17 #12 not #16 #16 #14 not #15 #15 #13 and #14 #14 (ANIMAL or NONHUMAN) in DER #13 HUMAN in DER #12 #9 or #10 or #11 #11 (SINGL* or DOUBL* or TREBL* or TRIPL*) near ((BLIND* or MASK*) in TI,AB) #10 (RANDOM* or CROSS?OVER* or FACTORIAL* or PLACEBO* or VOLUNTEER*) in TI,AB #9 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 #8 "SINGLE‐BLIND‐PROCEDURE"/ all subheadings #7 "DOUBLE‐BLIND‐PROCEDURE"/ all subheadings #6 "PHASE‐4‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL"/ all subheadings #5 "PHASE‐3‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL"/ all subheadings #4 "MULTICENTER‐STUDY"/ all subheadings #3 "CONTROLLED‐STUDY"/ all subheadings #2 "RANDOMIZATION"/ all subheadings #1 "RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL"/ all subheadings

Appendix 3. CENTRAL

#1 Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia #2 MeSH descriptor Uterine Cervical Neoplasms explode all trees #3 cervi* #4 cancer or tumor or tumour or malignan* or oncol* or carcinom* or neoplas* or growth or adenom* or cyst* #5 (#3 AND #4) #6 (#1 OR #2 OR #5) #7 radiother* #8 radiat* #9 MeSH descriptor Radiotherapy explode all trees #10 MeSH descriptor Radiotherapy, Computer‐Assisted explode all trees #11 (#7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10) #12 Hyperther* #13 MeSH descriptor Hyperthermia, Induced explode all trees #14 (#12 OR #13) #15 (#6 AND #11 AND #14)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. RT + HT versus RT: all studies.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 complete tumour response | 4 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.39, 0.79] |

| 1.2 local tumour recurrence_HR | 3 | 264 | Hazard Ratio (Exp[(O‐E) / V], Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.37, 0.63] |

| 1.3 overall survival_HR | 3 | Hazard Ratio (Exp[(O‐E) / V], Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.3.1 overall survival (death within 3 years) | 3 | 264 | Hazard Ratio (Exp[(O‐E) / V], Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.45, 0.99] |

| 1.4 toxicity (acute and late) | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.4.1 acute toxicity (< 3 months) | 4 | 310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.30, 3.31] |

| 1.4.2 late toxicity | 3 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.44, 2.30] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Chen 1997.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Single centre RCT (arms = 4 ) randomisation procedure: adequate, ITT: unknown, baseline characteristics similar: unknown, eligibility criteria specified: yes, losses to follow up fully accounted for: unknown, bias due withdrawal/drop‐out rate: unknown, co‐interventions influenced results: no | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer patients: E: 30, C: 30. FIGO stage: IIB (E:7, C:7);IIIB (E:23, C: 23) Age: E: unknown (32‐70), C: unknown (32‐70) WHO performance:0‐1 | |

| Interventions | HT: Vaginal applicators. Timing: from the second week of EBRT. Duration: 45 minutes. Sequence: 1 hour after EBRT. Frequency:twice weekly with 48 to 72 hour interval. Total number: 6. RT: Standard EBRT: linear accelerator or telecobalt. Two parallel opposed fields. Primary tumour and pelvic draining lymphatics. A total dose of 20 Gy in 10 fractions in 2 weeks and an additional dose of 20 Gy in 10 fractions with a central block. Brachytherapy: Co‐60. Timing: From the second week of EBRT. Dose per fraction: 5 to 10 Gy to 'Point A'. Frequency: weekly. Total number: 5‐6. CT: yes (groups were not included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | CR (end of treatment) | |

| Notes | 2 arms (n = 60) with CT were not included in review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A randomised Trial". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The patients were orderly grouped according to clinical stages". Taken the fact that it is a randomised trial this probably refers to a stratification procedure although this is not clear from the text. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. However, the outcome measurements are not likely to be influenced. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There were no missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available. An expected outcome measure was reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The study is published in a Chinese Journal. The English language used for reporting the material & method and result section is rather poor. Consequently important details may be missing. |

Datta 1987.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Multi centre RCT (arms = 2, centre = 3 ) randomisation procedure: unknown, ITT:no, baseline characteristics similar: unknown, eligibility criteria specified: yes, losses to follow up fully accounted for: yes, bias due with‐drawal/drop‐out rate: no, co‐interventions influenced results: no Total quality score: 2 | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer patients: E: 33, C: 31. FIGO stage IIIB. Histology: squamous cell carcinoma: 64. Age: E: unknown (33‐67), C: unknown (28‐74) WHO performance:unknown | |

| Interventions | HT: Capacitative applicators consisting of 2 plates. Duration: 15‐20 minutes. Sequence: immediately preceding EBRT. Frequency: twice weekly with 72 hour interval. Total number: unknown. RT: Standard EBRT: telecobalt. Four field box‐technique. Primary tumour and pelvic draining lymphatics. Total dose of 50 to 55 Gy in 25 to 28 fractions in 5 to 5½ weeks. An additional dose to the local tumour using antero‐posterior opposed fields delivering a 10‐15 Gy in 5‐8 fractions in 1‐1½ week. Brachytherapy: no CT: no | |

| Outcomes | CR (4 weeks after treatment) LR (2Y) DFS (2Y) | |

| Notes | No details on statistical analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "All cases were randomised and divided into two groups". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficiently described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. However, the outcome measurements are not likely to be influenced. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The number of missing outcome data is equally distributed across the intervention groups with similar reasons for missing |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available. Expected outcome measurements are reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | 11 patients were not included in the analysis due to 1) lost to follow‐up or 2) incomplete treatment. It is not stated how many patients per treatment group are due to either reason. Consequently exclusions for reasons related to the interventions cannot be ruled out. |

Harima 2001.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | single centre RCT (arms = 2) randomisation procedure: adequate, ITT: unknown, baseline characteristics similar: yes, eligibility criteria specified: yes, losses to follow up fully accounted for: yes, bias due withdrawal/drop‐out rate: no, co‐interventions influenced results: no Total quality score:4 | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer patients: E: 20, C: 20

FIGO stage IIIB (n=40)

Histology: Squamous cell carcinoma (n=35); Adenocarcinoma (n=5). Tumour diameter (mean): E 5.9 (+/‐ 2.2), C; 6.1 (+/‐ 1.8) Age: E: 64.9 (unknown), C: 61.6 (unknown) WHO performance: unknown |

|

| Interventions | HT: Capacitative applicators with 2 plates. Timing: after 3rd of 4th fraction of EBRT. Duration: 60 minutes. Sequence: within 30 minutes after EBRT. Frequency: once weekly. Total number: 3. RT: Standard EBRT: 6 MV linear accelerator. No details provided concerning radiation technique. Primary tumour and pelvic draining lymphatics. Total dose of 30.6 Gy in 17 fractions of 1.8 Gy, 5 times a week, with an additional dose of 52.2 Gy to the parametria with central shielding. EBRT to primary tumour and lymphatics 30.6 Gy/ 17 f, additional dose central block 52.2 Gy Brachytherapy: Ir‐192 (High Dose Rate). Timing: unknown. Dose per fraction: 7.5 Gy to 'Point A'. Frequency: once weekly during EBRT. Total number: 4. CT: no | |

| Outcomes | CR (at least 1 month after treatment) LR (3Y) DFS (3Y) OS (3Y) TOX acute and late |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization to treatment groups". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed by a computer generated random number list before the start of treatment". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. However, the outcome measurements are not likely to be influenced. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There were no missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available. Expected outcome measures are reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Sharma 1991.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | single centre RCT (arms = 2 ) randomisation procedure: adequate, ITT: no, baseline characteristics similar: yes, eligibility criteria specified: yes, losses to follow up fully accounted for: yes, bias due withdrawal/drop‐out rate: no, co‐interventions influenced results: no Total quality score: 4 | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer patients: E: 25, C: 25

FIGO stage IIA (n=3); IIB (n=4) andIIIB (n=43) Histology: squamous cell carcinoma (n=50) Tumour diameter: 2‐4 cm (E: 7; C 6); >4 cm (E: 18; C 19) Age: E: 50 (unknown), C: 48 (unknown) Karnofsky > 60 |

|

| Interventions | HT: Specially designed capacitative intraluminal radiofrequency heating system, consisting of a small intravaginal applicator and a large extracorporeal electrode. Timing: from start of EBRT. Duration: 30 minutes. Sequence: within 30 minutes preceding EBRT. Frequency: on alternate days 3 times per week. Total number: 12. RT: Standard EBRT: linear accelerator or telecobalt. Two parallel opposed fields. Primary tumour and pelvic draining lymphatics. Total dose 45 Gy in 20 fractions in 4 weeks. If brachytherapy not feasible an additional EBRT dose of 20 Gy in 10 fractions using same fields. Brachytherapy: if feasible. Cs‐137 (Low Dose Rate). Timing: following EBRT. Dose per fraction: 35 Gy to 'Point A'. Total number: 1. CT: no | |

| Outcomes | LR (18 MO) DFS (18 MO) OS (18 MO) TOX acute and late |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The patients were randomised blindly into 2 groups of 25 each". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | For randomisation the sealed envelope technique was used. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. However, the outcome measurements are not likely to be influenced. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There were no missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available. Expected outcome measurements are reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

van der Zee 2000.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Multi centre RCT (arms = 2, centre = 9 ) randomisation procedure: adequate, ITT: yes, baseline characteristics similar: yes, eligibility criteria specified: yes, losses to follow up fully accounted for: yes, bias due withdrawal/drop‐out rate: no, co‐interventions influenced results: no Total quality score: 5 | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer patients: E: 58, C: 56

FIGO stage IIB (n=22); IIIA (n=1); IIIB (n=80) and IVA (n=11). Histology: squamous cell carcinoma (n=97); adenocarcinoma (n=11); other (n=6) Tumour diameter: < 6cm (E 13; C 12); 6‐8 cm (E 26; C 27); > 8 cm (E 19; C 13); unknown (E 0; C 4). Age: E: 51 (26‐75), C: 50 (30‐82) WHO performance:<2 |

|

| Interventions | HT: Regional (deep) hyperthermia was applied in 3 different centres using the BSD‐2000 system, the 4‐waveguide applicator system and the coaxial TEM applicator, respectively. Timing: from the first week of EBRT on. Frequency: once weekly. Duration: 60‐90 minutes. Sequence: 1‐4 hours after EBRT. Total number: 0 (n=7);1‐3 (n=11) and 4‐6 (n=40). RT: Standard EBRT: linear accelerator. No details concerning radiation technique. Primary tumour and pelvic draining lymphatics with or without the para‐aortic lymph nodes. Total dose 46‐50.4 Gy in 23‐28 fractions. An additional dose to the pelvic sidewall was delivered in case of residual parametric tumour. If brachytherapy was not feasible an additional dose with EBRT was delivered to the tumour region. EBRT to primary tumour and lymphatics 46‐50.4 Gy/ 23‐28 f Brachytherapy: if feasible.(1) Ir‐192 (High Dose Rate; n=38); Timing: following EBRT. Dose per fraction: 8.5 Gy to 'Point A'. Frequency: weekly. Total number: 2. (2) Cs‐137 (Low Dose Rate; n=53); Timing: following EBRT. Dose per fraction: 20‐30 Gy to 'Point A'. CT: no | |

| Outcomes | CR (at least 1 month after treatment) LR (3Y) OS (3Y) TOX acute and late |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly assigned treatment". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was done centrally by telephone and stratified by centre, tumour site and stage in variable block size". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. However, the outcome measurements are not likely to be influenced. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There were no missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is available. All of the study's pre‐specified outcome measures were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Vasanthan 2005.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Multi centre RCT (arms = 2, centre = 5 ) randomisation procedure: adequate, ITT: yes, baseline characteristics similar: yes, eligibility criteria specified: yes, losses to follow up fully accounted for: yes, bias due withdrawal/drop‐out rate: no co‐interventions influenced results: no Total quality score: 5 | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer patients: E: 55, C: 55

Figo stage IIB (n=56); IIIA (n=9); IIIB (n=42) and IVA (n=3). Histology: squamous cell carcinoma (n=103); adenocarcinoma (n=4); other (n=3). Tumour volume (median): E: 60 cm3 ; C 50 cm3. Age: E: 45 (27‐72), C: 50 (22‐71) WHO performance:<2 |

|

| Interventions | HT: Capacitative applicators with 2 plates were used for generating local hyperthermia. In at least half of the patients this was combined with an intravaginal electrode. Protocols varied per centre. Timing: not available. Frequency: once weekly. Duration: 60 minutes. Sequence: immediately after EBRT (three centres); immediately before EBRT (one centre) Not available (one centre). Total number: 3‐6. RT: Standard EBRT: 6‐18 MV linear accelerator or telecobalt. Primary tumour and pelvic lymphatics. (n = 54) A total EBRT dose of 50 Gy in 2 Gy fractions in 5 weeks. Four field box technique. Two patients received an additional EBRT dose of 20 Gy instead of brachytherapy. Brachytherapy: Low Dose Rate. Timing: following EBRT. Dose per fraction: 20‐22 Gy to 'Point A'. Total number: 1. (n = 28) A total EBRT dose of 14‐18 Gy in 2 Gy fractions followed by an additional dose of 24‐32 Gy using central shielding. Parallel opposed fields. Brachytherapy: High Dose Rate. Timing: unavailable. Dose per fraction: 5 Gy to 'Point A'. Frequency: unknown. Total number: 10. (n = 18) A total EBRT dose of 50.4 Gy in 1.8 to 2 Gy fractions, in 5 to 6 weeks. Four field box technique. An additional parametrial boost of 5.4 Gy in 3 fractions with central shielding. Brachytherapy: Co‐60 (High Dose Rate). Timing: following EBRT dose of 50.4 Gy. Dose per fraction: 3 Gy to 'Point A'. Frequency: 3 times weekly. Total number: 7‐13. (n = 9) A total EBRT dose of 30 Gy in 2 Gy fractions, 5 times a week followed by an additional dose of 20 Gy with central shielding. Four field box or parallel opposed fields. Brachytherapy: High Dose Rate. Timing: concomitantly with EBRT. Dose per fraction: 6 Gy to 'point A'. (n = 1) EBRT to primary tumour and lymphatics 30 Gy/wk, Brachytherapy: A total EBRT dose of 30 Gy in 2 Gy fractions. Brachytherapy: High Dose Rate. Timing: unavailable. Dose per fraction: 6 Gy to 'point A'. Frequency: twice weekly. Total number: 4. CT: no |

|

| Outcomes | LR (3Y)

OS (3Y) TOX acute and late |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were registered and randomized". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Probably central allocation since (quote) "patients were stratified by institution". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. However, the outcome measurements are not likely to be influenced. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There were no missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available. Not all expected outcome measures are reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The study was terminated after including 110 patients instead of 258 patients originally planned due to 1) the results of a preliminary analysis showing no difference between both treatment arms and 2) the slow accrual rate. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| El Sharouni 1997 | no RCT |

| Fujiwara 1987 | no RCT |

| Gupta 1999 | no RCT |

| Hasegawa 1989 | no RCT |

| Hornback 1986 | no RCT |

| Kohno 1990 | no RCT |

| Li 1993 | not able to contact author |

| Prosnitz 2002 | RCT, ongoing |

RCT = Randomized clinical trial

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Harima.

| Study name | Multicenter trial (6 centres) |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Cervical cancer |