Summary

Eubacterium limosum KIST612 is one of the few acetogenic bacteria that has the genes encoding for butyrate synthesis from acetyl‐CoA, and indeed, E. limosum KIST612 is known to produce butyrate from CO but not from H2 + CO2. Butyrate production from CO was only seen in bioreactors with cell recycling or in batch cultures with addition of acetate. Here, we present detailed study on growth of E. limosum KIST612 on different carbon and energy sources with the goal, to find other substrates that lead to butyrate formation. Batch fermentations in serum bottles revealed that acetate was the major product under all conditions investigated. Butyrate formation from the C1 compounds carbon dioxide and hydrogen, carbon monoxide or formate was not observed. However, growth on glucose led to butyrate formation, but only in the stationary growth phase. A maximum of 4.3 mM butyrate was observed, corresponding to a butyrate:glucose ratio of 0.21:1 and a butyrate:acetate ratio of 0.14:1. Interestingly, growth on the C1 substrate methanol also led to butyrate formation in the stationary growth phase with a butyrate:methanol ratio of 0.17:1 and a butyrate:acetate ratio of 0.33:1. Since methanol can be produced chemically from carbon dioxide, this offers the possibility for a combined chemical‐biochemical production of butyrate from H2 + CO2 using this acetogenic biocatalyst. With the advent of genetic methods in acetogens, butanol production from methanol maybe possible as well.

In this study, we have investigated the growth of and product formation by the acetogen Eubacterium limosum KIST612 on different carbon and energy sources with the goal to find substrates that lead to formation of butyrate. Butyrate is an important product that can be further reduced to the highly valuable biofuel butanol in a two‐step enzymatic process.

Introduction

Acetogens are a physiological group of strictly anaerobic bacteria that are characterized by a special pathway for CO2 fixation, the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (WLP) (Müller, 2003; Drake et al., 2008; Ragsdale, 2008). The WLP is a branched linear pathway in which two mol of CO2 are reduced to one mol of acetyl‐CoA which is further converted to acetate in all species under most conditions (Müller and Frerichs, 2013). Moreover, some species can convert acetyl‐CoA (or acetate) to ethanol or even to C4 compounds such as butyrate (Daniell et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2015; Bengelsdorf et al., 2016). Therefore, acetogens have come into focus as biocatalysts for a CO2‐based bioeconomy and ethanol is already produced on an industrial scale using Clostridium autoethanogenum (Bengelsdorf et al., 2018; Heffernan et al., 2020). The addition of one carbon to the chain length of the product increases the value of the product by a factor of 1.5–3, depending on the product (Kim et al., 2019). Butyrate is not a prime product to be produced but it can be reduced to butanol in a two‐step enzymatic process and butanol is a highly desired biofuel (Dürre, 2016). Butyrate is produced naturally by only a few acetogens such as Clostridium carboxidivorans (Liou et al., 2005), Clostridium drakei (Küsel et al., 2000; Liou et al., 2005), Oxobacter pfennigii (Krumholz and Bryant, 1985) and E. limosum strains such as KIST612 (Pacaud et al., 1985; Loubiere and Lindley, 1991; Chang et al., 1997). The latter has gained much interest for it produces butyrate form synthesis gas (syngas), a mixture of H2, CO2 and CO in different concentrations, depending on the source (Chang et al., 2001; Park et al., 2017). Syngas is an industrial waste stream that is already been used as feedstock for acetogenic conversion to ethanol (Dürre and Eikmanns, 2015; Humphreys and Minton, 2018). However, butyrate formation in E. limosum KIST612 was only observed in bioreactors with cell recycling (Chang et al., 2001), but not in batch cultures or only to minor amounts when acetate was added to the culture (Park et al., 2017). Methanol and formate are two promising, alternative feedstocks for the industrial production of biofuels using acetogens as they can be produced from many sustainable feedstocks including biomass, municipial solid waste, biogas as well as CO2. One major advantage using these two feedstocks is that they are fully soluble and therefore can overcome the challenges gaseous C1 feedstocks are facing due to their low mass transfer. In addition, formate and methanol can also be easily transported and stored.

The methyl group of methanol is channelled into the WLP by a methyltransferase system (Kremp et al., 2018; Kremp and Müller, 2020) whereas formate is an intermediate of the pathway (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, it is not known whether these C1 substrates maybe converted to butyrate as well. Here, we have investigated the physiology of growth of E. limosum KIST612 on different substrates with a focus on the production of butyrate.

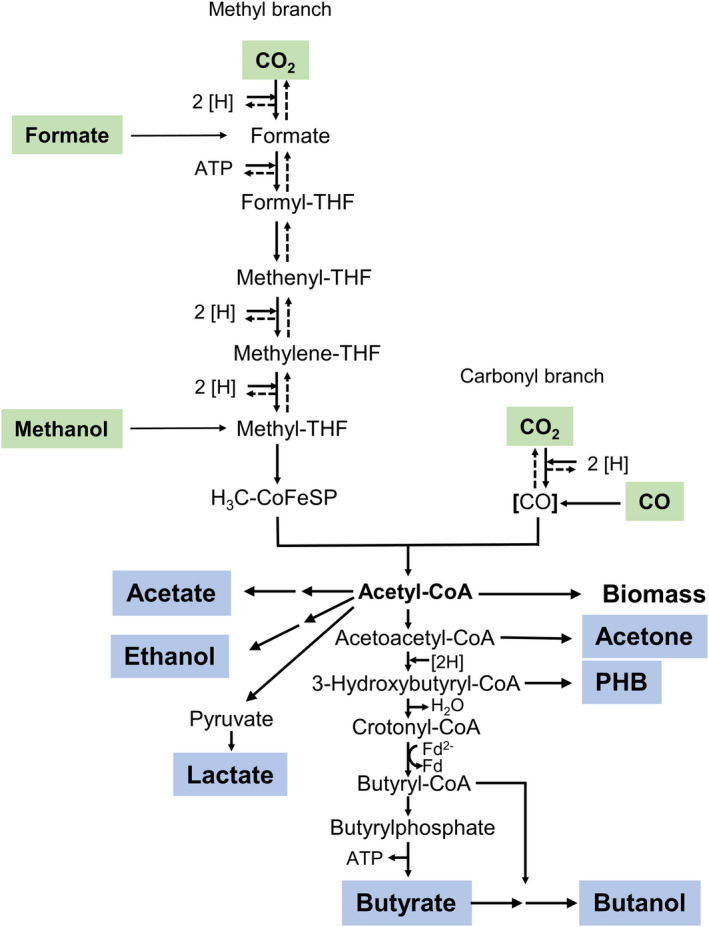

Fig. 1.

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 reduction. In the WLP, two molecules of CO2 are reduced to the central intermediate acetyl‐CoA. Entry points for other C1 substrates are indicated. Acetyl‐CoA is the precursor of biomass and a wide range of natural products (blue). The pathways leading from acetyl‐CoA to products are not complete and miss intermediates, reducing equivalents and ATP input/output. Only the pathway leading to butyrate is complete. CoFeSP, corrinoid/iron sulfur protein; THF, tetrahydrofolate; CoA, coenzyme A; [H], reducing equivalent.

Results and discussion

Growth with and product formation from glucose

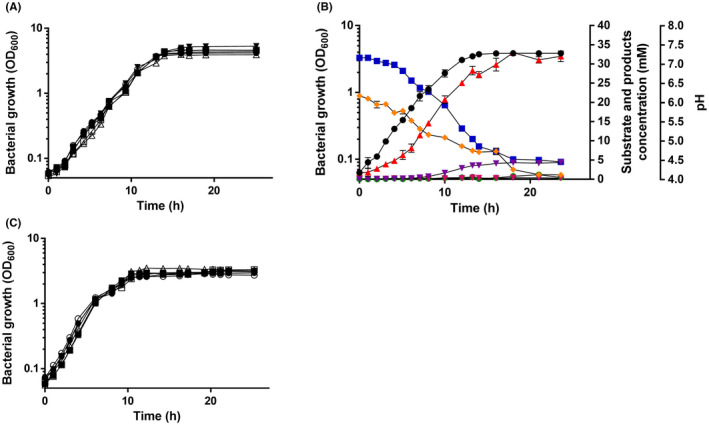

When E. limosum KIST612 was transferred to carbonate buffered basal medium (CBBM) (Chang et al., 1999) containing different amounts of glucose ranging from 20 to 200 mM, growth rates were identical (µ = 0.34 h−1) as were the final yields (OD600 = 4.5). To describe the growth physiology in more detail, cells were cultured on 20 mM glucose. On transfer of a glucose‐adapted preculture to fresh medium, growth started immediately with a rate of 0.34 h−1 and proceeded for about 13 h, before the stationary phase started (Fig. 2). Parallel to growth, the glucose concentration dropped continuously with a rate of 1.4 mmol l−1∙h−1 to a residual concentration of 1.2 mM. In parallel, the pH dropped from 7.2 to 4.5. Glucose consumption was paralleled by a production of acetate that reached a final concentration of 32.1 mM, corresponding to an acetate:glucose ratio of 1.7:1. Interestingly, at the end of the exponential growth phase butyrate was produced and butyrate production reached a steady state at around 17 h. The final butyrate concentration was 4.3 mM, corresponding to a butyrate:glucose ratio of 0.23:1. Even later, at around 13 h, ethanol formation started, but ethanol formation was very small with values in the 0.4–0.7 mM range. In total, the recovery of glucose in all end products was 75 ± 3.9 %, not accounting for CO2. Growth on fructose led to similar growth characteristics (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Growth of E. limosum on glucose and fructose. E. limosum KIST612 was grown at 37°C in 500 ml of carbonate‐buffered basal medium (CBBM) (Chang et al., 1999) with glucose under a N2/CO2 (80/20% [v/v]) atmosphere. Growth was followed by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm.

A. Growth of E. limosum on 20 (●), 40 (○), 80 (▼), 120 (▵), 160 (■) or 200 (□) mM glucose.

B. Growth and product portfolio of E. limosum on 20 mM glucose. OD600 (●) was determined photometrically, pH ( ) was determined with an Orion Basic electrode (Thermo Electron Corp. Witchford, UK). The concentration of glucose (

) was determined with an Orion Basic electrode (Thermo Electron Corp. Witchford, UK). The concentration of glucose ( ) was determined by a d‐glucose/d‐fructose assay kit (R‐Biopharm, Pfungstadt, Germany). Acetate (

) was determined by a d‐glucose/d‐fructose assay kit (R‐Biopharm, Pfungstadt, Germany). Acetate ( ), butyrate (

), butyrate ( ) and ethanol (

) and ethanol ( ) were measured by gas chromatography as described previously (Jeong et al., 2015).

) were measured by gas chromatography as described previously (Jeong et al., 2015).

C. Growth of E. limosum on 20 (●), 40 (○), 80 (▼), 120 (▵), 160 (■) or 200 (□) mM fructose. All data points are mean ± SEM; N = 3 independent experiments.

Growth with and product formation from H2 + CO2, CO or formate

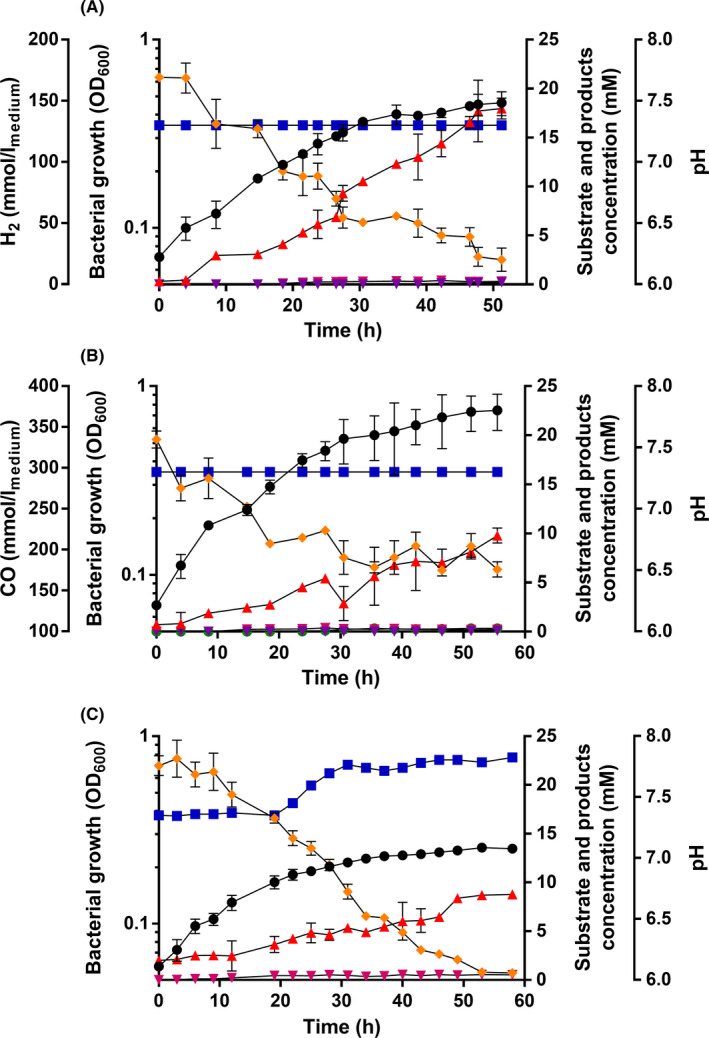

The WLP accepts different C1 substrates with different oxidation/reduction states. Growth of E. limosum KIST612 on H2 + CO2 and CO have been described (Chang et al., 2001); the entry points are shown in Fig. 1. Formate is an intermediate of the WLP but has not been described as substrate for E. limosum KIST612. Growth on H2 + CO2 or CO proceeded with growth rates of 0.04 and 0.05 h−1; acetate was the major product, butyrate was only observed in trace amounts (Fig. 3). Cells also grew on formate with a growth rate similar to H2 + CO2 or CO (0.03 h−1) but the final yield was much lower (OD600 = 0.25). Growth was accompanied by acetate production, but due to the consumption of formate, in sum, the pH increased slightly. Butyrate was not produced.

Fig. 3.

Growth of E. limosum on H2 + CO2, CO or formate.

A. E. limosum was grown at 37°C in 500 ml of CBBM with overpressure of 1 bar H2 + CO2 (80/20% [v/v]). H2 + CO2 ( ) was determined by gas chromatography as described previously (Bertsch and Müller, 2015). OD600 (●), pH (

) was determined by gas chromatography as described previously (Bertsch and Müller, 2015). OD600 (●), pH ( ) as well as acetate (

) as well as acetate ( ), butyrate (

), butyrate ( ) and isobutyrate (

) and isobutyrate ( ) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

B. E. limosum was grown at 37°C in 500 ml of phosphate buffered basal medium (Chang et al., 1999) with overpressure of 1 bar CO (100%) ( ). CO was determined by gas chromatography as described previously (Bertsch and Müller, 2015). OD600 (●), pH (

). CO was determined by gas chromatography as described previously (Bertsch and Müller, 2015). OD600 (●), pH ( ) as well as acetate (

) as well as acetate ( ), butyrate (

), butyrate ( ), isobutyrate (

), isobutyrate ( ) and ethanol (

) and ethanol ( ) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2 (Bertsch and Müller, 2015).

) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2 (Bertsch and Müller, 2015).

C. E. limosum KIST612 was grown at 37°C in 500 ml of CBBM with 20 mM Na+‐Formate ( ) under a N2/CO2 (80/20% [v/v]) atmosphere. The concentration of formate was determined by a formate assay kit (R‐Biopharm, Pfungstadt, Germany). OD600 (●), pH (

) under a N2/CO2 (80/20% [v/v]) atmosphere. The concentration of formate was determined by a formate assay kit (R‐Biopharm, Pfungstadt, Germany). OD600 (●), pH ( ) as well as acetate (

) as well as acetate ( ), butyrate (

), butyrate ( ) and isobutyrate (

) and isobutyrate ( ) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. All data points are mean ± SEM; N = 3 independent experiments.

) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. All data points are mean ± SEM; N = 3 independent experiments.

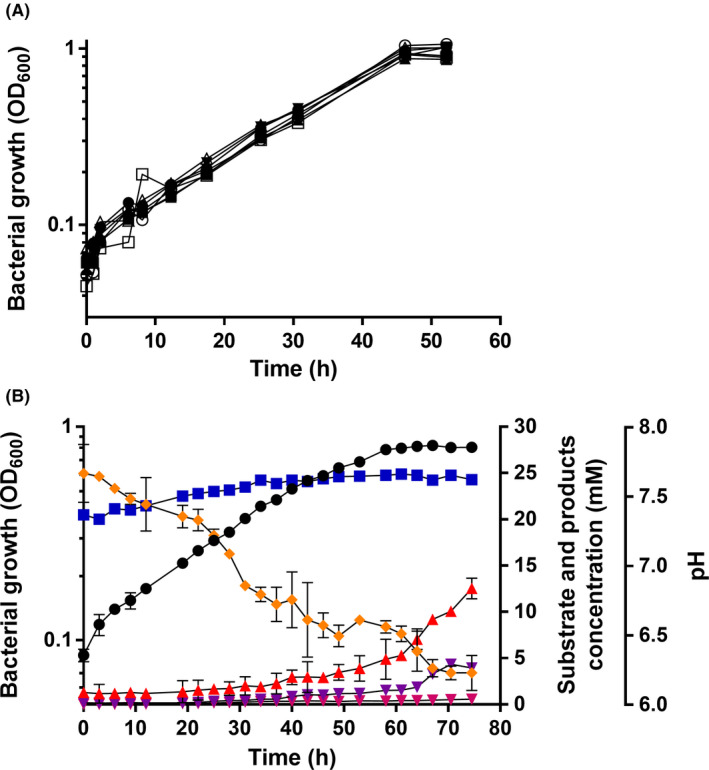

Growth with and product formation from methanol

E. limosum did grow on methanol as sole carbon and energy source, as predicted from its genome sequence (Roh et al., 2011). Whereas A. woodii reached the maximum growth rate at 60 mM methanol (Kremp et al., 2018), growth of E. limosum was already maximal at 20 mM methanol. When a methanol‐adapted culture (two transfers) of E. limosum KIST612 was transferred to CBBM with 20 mM methanol, growth started immediately with a doubling time of 17.61 h and proceed for about 60 h, before the stationary phase started (Fig. 4). Parallel to growth, the methanol concentration dropped continuously with a rate of 0.29 mmol l−1∙h−1 to a residual concentration of 3.4 mM. Methanol consumption was accompanied by a production of acetate that reached a final concentration of 12 mM, corresponding to an acetate:methanol ratio of 0.53:1. Since acetogenesis from methanol according to Equation (1):

| (1) |

removes the CO2 from the solution leading to alkalinization parallel to acidification by acid production, the pH did not drop but increased slightly. Most important, again at the end of the exponential growth phase butyrate was produced and butyrate production reached a steady state at around 67 h. The final butyrate concentration was 3.7 mM, corresponding to a butyrate:methanol ratio of 0.17:1. Ethanol was not observed but traces of isobutyrate (0.5 mM). In sum, almost all substrate carbon (methanol + CO2) was recovered in the major end products acetate and butyrate (99 ± 10.3%).

Fig. 4.

Growth of E. limosum on methanol. E. limosum KIST612 was grown at 37°C in 500 ml of CBBM with methanol under a N2/CO2 (80/20% [v/v]) atmosphere.

A. Growth of E. limosum on 20 (●), 40 (○), 80(▼), 100 (▵), 120 (▲), 160 (■) or 200 (□) mM methanol.

B. E. limosum KIST612 was grown at 37°C in 500 ml of CBBM with 20 mM methanol under a N2/CO2 (80/20% [v/v]) atmosphere. OD600 (●), pH ( ) as well as acetate (

) as well as acetate ( ), butyrate (

), butyrate ( ), isobutyrate (

), isobutyrate ( ), ethanol (

), ethanol ( ) and methanol (

) and methanol ( ) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. All data points are mean ± SEM; N = 3 independent experiments

) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. All data points are mean ± SEM; N = 3 independent experiments

Conclusion

Here we describe for the first time that the acetogen E. limosum KIST612 produces butyrate from methanol. Growth on methanol requires the action of a methyltransferase system that transfers the methyl group from methanol to tetrahydrofolate and E. limosum KIST612 has a gene cluster similar to a previously suggested methanol‐specific methyltransferase system of A. woodii (Kremp and Müller, 2020). Buytrate production from acetyl‐CoA follows the pathways described for example for Clostridium acetobutylicum (Dürre et al., 2002) involving thiolase, hydroxybutyryl‐CoA dehydrogenase, crotonase and butyryl‐CoA dehydrogenase with the exception, that the latter is electron‐bifurcating and reduces ferredoxin alongside with crotonyl‐CoA (Jeong et al., 2015). As in clostridia, butanol could be produced from butyryl‐CoA by two subsequent reduction steps (Dürre, 2016). With the establishment of first genetic methods from E. limosum KIST612 (Jeong et al., 2020) it should be possible in the future to express butyryl‐CoA dehydrogenases in E. limosum KIST612. This would make methanol a promising feedstock for acetogenic production of butyrate.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the European Research Area Cofund on BioTechnologies (ERA CoBioTech; project BIOMETCHEM) is gratefully acknowledged.

Microbial Biotechnology (2021) 14(6), 2686–2692

Funding Information

Financial support by the BMBF‐Project ‘Biometchem’ is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Bengelsdorf, F.R. , Beck, M.H. , Erz, C. , Hoffmeister, S. , Karl, M.M. , Riegler, P. , et al. (2018) Bacterial anaerobic synthesis gas (syngas) and CO2+H2 Fermentation. Adv Appl Microbiol 103: 143–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengelsdorf, F.R. , Poehlein, A. , Linder, S. , Erz, C. , Hummel, T. , Hoffmeister, S. , et al. (2016) Industrial acetogenic biocatalysts: a comparative metabolic and genomic analysis. Front Microbiol 7: 1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch, J. , and Müller, V. (2015) CO metabolism in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii . Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 5949–5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, I.S. , Kim, B.H. , Kim, D.H. , Lovitt, R.W. , and Sung, H.C. (1999) Formulation of defined media for carbon monoxide fermentation by Eubacterium limosum KIST612 and the growth characteristics of the bacterium. J Biosci Bioeng 88: 682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, I.S. , Kim, B.H. , Lovitt, R.W. , and Bang, J.S. (2001) Effect of CO partial pressure on cell‐recycled continuous CO fermentation by Eubacterium limosum KIST612. Process Biochem 37: 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, I.S. , Kim, D.H. , Kim, B.H. , Shin, P.K. , Yoon, J.H. , Lee, J.S. , and Park, Y.H. (1997) Isolation and identification of carbon monoxide utilizing anaerobe, Eubacterium limosum KIST612. Kor J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 25: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Daniell, J. , Köpke, M. , and Simpson, S.D. (2012) Commercial biomass syngas fermentation. Energies 5: 5372–5417. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, H.L. , Gößner, A.S. , and Daniel, S.L. (2008) Old acetogens, new light. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125: 100–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürre, P. (2016) Butanol formation from gaseous substrates. FEMS Microbiol Lett 363: fnw040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürre, P. , Böhringer, M. , Nakotte, S. , Schaffer, S. , Thormann, K. , and Zickner, B. (2002) Transcriptional regulation of solventogenesis in Clostridium acetobutylicum . J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 4: 295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürre, P. , and Eikmanns, B.J. (2015) C1‐carbon sources for chemical and fuel production by microbial gas fermentation. Curr Opin Biotechnol 35: 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, J.K. , Valgepea, K. , de Souza Pinto Lemgruber, R. , Casini, I. , Plan, M. , Tappel, R. , et al. (2020) Enhancing CO2‐valorization using Clostridium autoethanogenum for sustainable fuel and chemicals production. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8: 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, C.M. , and Minton, N.P. (2018) Advances in metabolic engineering in the microbial production of fuels and chemicals from C1 gas. Curr Opin Biotechnol 50: 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J. , Bertsch, J. , Hess, V. , Choi, S. , Choi, I.G. , Chang, I.S. , and Müller, V. (2015) Energy conservation model based on genomic and experimental analyses of a carbon monoxide‐utilizing, butyrate‐forming acetogen, Eubacterium limosum KIST612. Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 4782–4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J. , Kim, J.‐Y. , Park, B. , Choi, I.‐G. , and Chang, I.S. (2020) Genetic engineering system for syngas‐utilizing acetogen, Eubacterium limosum KIST612. Bioresour Technol Rep 11: 100452. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Jeon, B.S. , and Sang, B.‐I. (2019) An efficient new process for the selective production of odd‐chain carboxylic acids by simple carbon elongation using Megasphaera hexanoica . Sci Rep 9: 11999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremp, F. , and Müller, V. (2020) Methanol and methyl group conversion in acetogenic bacteria: Biochemistry, physiology and application. FEMS Microbiol Rev, in press. 10.1093/femsre/fuaa040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremp, F. , Poehlein, A. , Daniel, R. , and Müller, V. (2018) Methanol metabolism in the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii . Environ Microbiol 20: 4369–4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz, L.R. , and Bryant, M.P. (1985) Clostridium pfennigii sp. nov. uses methoxyl groups of monobenzenoids and produces butyrate. Int J Syst Bacteriol 35: 454–456. [Google Scholar]

- Küsel, K. , Dorsch, T. , Acker, G. , Stackebrandt, E. , and Drake, H.L. (2000) Clostridium scatologenes strain SL1 isolated as an acetogenic bacterium from acidic sediments. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 50: 537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou, J.S. , Balkwill, D.L. , Drake, G.R. , and Tanner, R.S. (2005) Clostridium carboxidivorans sp. nov., a solvent‐producing Clostridium isolated from an agricultural settling lagoon, and reclassification of the acetogen Clostridium scatologenes strain SL1 as Clostridium drakei sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55: 2085–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loubiere, P. , and Lindley, N.D. (1991) The use of acetate as an additional co‐substrate improves methylotrophic growth of the acetogenic anaerobe Eubacterium limosum when CO2 fixation is rate‐limiting. J Gen Microbiol 137: 2247–2251. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, V. (2003) Energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 6345–6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, V. , and Frerichs, J. (2013) Acetogenic bacteria. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470015902.a0020086.pub2. [Google Scholar]

- Pacaud, S. , Loubiere, P. , and Goma, G. (1985) Methanol metabolism by Eubacterium limosum B2: Effects of pH and carbon dioxide on growth and organic acid production. Curr Microbiol 12: 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. , Yasin, M. , Jeong, J. , Cha, M. , Kang, H. , Jang, N. , et al. (2017) Acetate‐assisted increase of butyrate production by Eubacterium limosum KIST612 during carbon monoxide fermentation. Bioresour Technol 245: 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale, S.W. (2008) Enzymology of the Wood‐Ljungdahl pathway of acetogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125: 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh, H. , Ko, H.J. , Kim, D. , Choi, D.G. , Park, S. , Kim, S. , et al. (2011) Complete genome sequence of a carbon monoxide‐utilizing acetogen, Eubacterium limosum KIST612. J Bacteriol 193: 307–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]