Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and its complications have been the major cause of cirrhosis and its complications for several decades in the Western world. Until recently, treatment for HCV with interferon-based regimens was associated with moderate success but was difficult to tolerate. More recently, however, an arsenal of novel and highly effective direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs has transformed the landscape by curing HCV in a broad range of patients, including those with established advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, co-morbidities, and even with complications of cirrhosis. Fibrosis is a dynamic process comprising both extracellular matrix deposition, as well as its degradation. With almost universal sustained virologic response (SVR); i.e., elimination of HCV, it is timely to explore whether HCV eradication can reverse fibrosis and cirrhosis. Indeed, fibrosis in several types of liver disease is reversible, including HCV. However, we do not know in whom fibrosis regression can be expected after HCV elimination, how quickly it occurs, and whether antifibrotic therapies will be indicated in those with persistent cirrhosis. This review summarizes the evidence for reversibility of fibrosis and cirrhosis after HCV eradication, its impact on clinical outcomes, and therapeutic prospects for directly promoting fibrosis regression in patients whose fibrosis persists after SVR.

Introduction

In the liver, ongoing fibrogenesis often leads to cirrhosis. Cirrhosis affects hundreds of millions of patients worldwide. and in 2010 caused over 1 million deaths, more than a third greater than 20 years earlier1. Mortality from cirrhosis is high in the United States; in 2010, it was the 11th leading cause of death, responsible for approximately 50,000 deaths2.

Cirrhosis can be associated with complications including portal hypertension, impaired synthetic function, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In chronic diseases of the liver and other parenchymal organs3, fibrosis is a dynamic process with both extracellular matrix deposition, as well as degradation occurring concurrently. With ongoing injury, the production of fibrosis (‘fibrogenesis’) eventually outpaces the liver’s capacity to degrade scar, and accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) ensues. Nonetheless, mounting evidence indicates that fibrosis and even cirrhosis are reversible (see3, 4 for review). For the purposes of this review, the terms “reversible”, “reversion”, “reversal”, and “regression” are used interchangeably to indicate that fibrosis content has decreased; importantly, these terms are not meant imply that the liver has returned to a completely normal state.

Since fibrosis is reversible and HCV elimination with direct acting antiviral (DAA) therapy is now expected in almost all patients, several questions arise (Table 1): In whom and how quickly does fibrosis regression occur? When is fibrosis regression associated with improved clinical outcomes? What are underlying mechanisms of fibrosis regression and does regression of cirrhosis reduce the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma?

Table 1.

Critical issues after HCV SVR

| Which patients can expect clinically significant fibrosis regression? |

| How much fibrosis regression might be expected after SVR? |

| Is fibrosis regression linear over time or does it vary? What is the expected degree of variability in regression? |

| What clinical and/or biologic factors are important in fibrosis regression? |

| Assuming that fibrosis regression occurs, will this be linked to improved outcomes? |

| Is HCV eradication with an interferon based therapy the same as with a DAA based therapy? |

| If fibrosis does not regress entirely, should a primary anti-fibrotic treatment be considered? |

| How should fibrosis regression be measured? |

| Is fibrosis reversion associated with reduced risk for hepatocellular carcinoma? |

Fibrosis regression in context

Fibrosis can regress, both in experimental models5–7 and in human liver diseases3, 4. Although fibrosis progression is often depicted as linear along a continuum from stage 0 to 4 (in typical staging systems), this assertion is oversimplified, and in fact fibrosis progression tends to accelerate as the disease advances, especially towards more advanced stages8. The rate of HCV progression has been ascribed to a number of factors including BMI, concurrent alcoholic or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, co-infection with HIV, as well as genetic determinants9–14.

The dynamics of fibrosis regression after SVR have not been well defined, in large part because liver biopsy is rarely performed after SVR. Regression is probably not linear, and may be influenced by the amount of fibrosis and its physical distribution, other underlying disease(s), or by environmental or genetic factors, much like the variable factors that influence fibrosis progression. However, because so few patients have been biopsied after HCV SVR (given its own limitations 15), there have been no studies yet to identify genetic determinants (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms or other markers) of fibrosis regression, but as newer non-invasive markers of fibrosis become validated, they may enable such studies. At present, non-invasive markers do not reliably confirm regression of fibrosis, although the rapid advances in imaging and other non-invasive technologies, especially MR-based methods 16, 17 make this a realistic hope in the coming years. Reliance on non-invasive markers of fibrosis will likely be critical in the assessing fibrosis regression in the future; however, a detailed discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this review.

Remarkably, the definition of fibrosis regression has not been standardized, but is generally meant to indicate a reduction in fibrosis content. This working definition does not account, however, for other changes in liver architecture - especially in the cirrhotic liver - for example, change in nodule size, the extent of terminal venular collapse, elements of regeneration, or altered types or distributions of collagen and other ECM components. Moreover, those few studies that have characterized fibrosis regression (particularly after DAA therapy) have only followed patients for 2–3 years, making it impossible to track long-term histologic changes following SVR. It is likely, but not established, that fibrosis regression also varies among different types of injury. For example, biliary fibrosis is readily reversible in animal models and can lead to complete removal of excess collagen18, 19. Fibrosis in post-necrotic models or human diseases (such as hepatotoxin-injury in rodents, or due to viral hepatitis in humans) is only partially reversible, with significant architectural remodeling but long-term persistence of excess ECM6, 7.

A critical unknown in fibrosis regression is the “point of no return”. In other words, when is the liver so diseased that there will be no regression after SVR? While there are scant data, most experts believe that once there is severe architectural distortion, vascular collapse and portal hypertension, significant regression is less likely20, 21. Some improvement in portal hypertension has been documented by assessing hepatic venous pressure gradients pre- and post-SVR22, 23 (see below), but it is unknown whether there is a threshold beyond which improvement is unlikely. It is also not known whether the rates of progression and regression are linked, such that patients who progress more rapidly may also regress more rapidly.

More studies are needed to define the influence of these and other variables in regulating fibrosis regression, as well as those clinical and/or biologic factors that influence regression (Table 1).

Basic mechanisms underlying reversion of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis

Cell Biology of Fibrosis Regression

In all fibrotic liver diseases, mesenchymal cells produce extracellular matrix that is deposited in the parenchyma and eventually disrupts organ function3. In liver disease, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are the key source of fibrogenesis following their transdifferentiation into activated myofibroblasts4, 24, 25 (Figure 1). This cell responds to a variety of extracellular signals that drive the fibrogenic response (Figure 1) (see4, 25–27 for reviews). Recent single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) studies have described significant heterogeneity of HSCs and have established specific markers for various HSC subtypes28, 29.

Figure 1. HSC activation.

A key pathogenic feature underlying liver fibrosis and cirrhosis is activation of effector cells in the liver know as hepatic HSCs (note that activation of other effector cells is likely to parallel that of HSCs). The activation process is complex, both in terms of the events that induce activation and the effects of activation. Multiple and varied stimuli participate in the induction and maintenance of activation, including, but not limited to signals from other cells (including especially endothelial cells and Kupffer cells, but also hepatocytes, lymphocytes, and even others). cytokines, chemokines, peptides and proteases, and the extracellular matrix itself. Key phenotypic features of activation are highlighted (including the production of extracellular matrix proteins, loss of retinoids, cellular proliferation, upregulation of smooth muscle proteins with associated enhanced contractility, secretion of metalloproteases which disrupt the normal extracellular matrix, secretion of peptides and cytokines (which have autocrine effects on HSCs and paracrine effects on other cells such as leukocytes and malignant cells), and upregulation of various cytokine and peptide receptors).

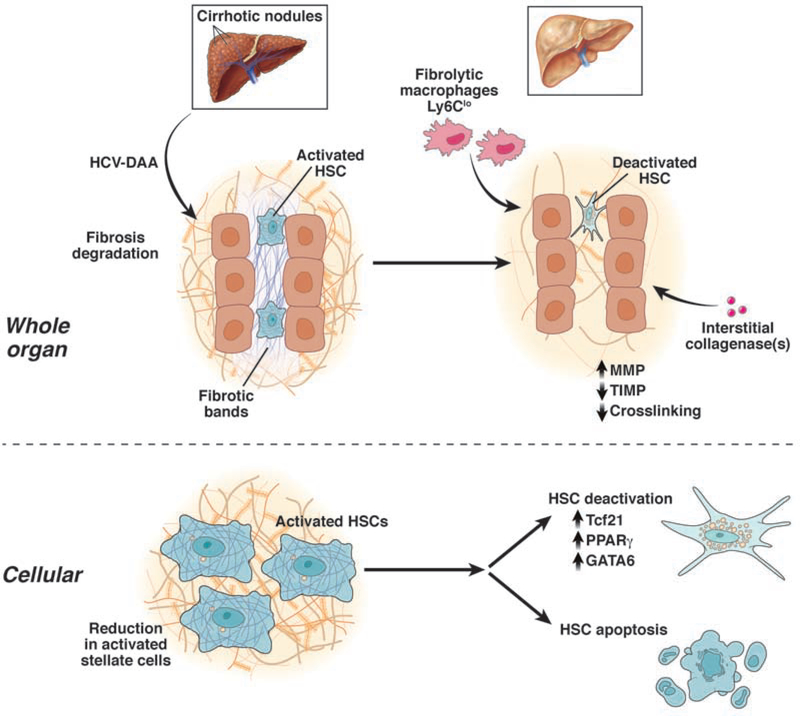

At the cellular level, multiple mechanisms may underlie fibrosis regression, although there are major gaps in our understanding (Figure 2). The fate of activated HSCs after resolution of injury has been better characterized than most pathways related to fibrosis regression, albeit primarily in animal models. At least 3 pathways of HSC responses during regression have been described in animal models: 1) reversion to an inactivated state30, 31, 2) apoptosis/autophagy32, and 3) cellular senescence33. Additionally, in cell culture models, HSCs may also revert from an activated to a quiescent state34–37.

Figure 2. Mechanism of fibrosis regression.

The figure emphasizes that HSCs, found in abundance in the injured/fibrotic liver (predominantly in fibrotic bands and areas of fibrosis, may revert to a quiescent phenotype, or may be eliminated through apoptosis – for example after DAA treatment of HCV. A variety of the molecular pathways, and contributing cellular elements are highlighted. These latter cell fates are likely to play a critical role in fibrosis regression.

The reversion, or ‘deactivation’ of HSCs indicates that when liver injury resolves the cells transition to a more quiescent, or inactivated state, yet they harbor the capacity to reactivate more quickly than truly quiescent cells30, 31. The molecular basis for inactivation has recently been clarified with the identification of the Tcf21 transcription factor in mice, which can revert activated HSCs to a more quiescent state38, 39,40. Other transcription factors contributing to HSC quiescence include GATA 4/6, LhX2, RARβ IRF 1 / 2, PPARγ, ETS 1 / 2, GR and NF1 (39 and references therein). These other molecules, which bind DNA to influence gene expression, represent potential therapeutic targets since their overexpression could induce HSC quiescence in injured liver, as shown experimentally for Tcf21.

Apoptosis of HSCs may lead to a decrease in the number of activated HSCs during fibrosis resolution in vivo32. However, apoptotic signaling in HSCs has been characterized largely in cultured cells41. Importantly, molecules regulating survival and apoptosis appear closely linked to mediators of ECM degradation. For example, matrix-metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2) activity correlates with apoptosis, and MMP2 may be stimulated by apoptosis42. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1), may be a critical regulator of MMP-2’s proteolytic activity, and since it is highly expressed by activated HSCs, could inhibit proteases capable of degrading accumulating matrix43, 44. It is also a survival factor for HSCs.

Programmed cell death is also associated with the appearance of autophagosomes that require autophagy effector proteins. Autophagy, a catabolic process involving degradation of cellular components through the lysosomal pathway, provides critical energy to fuel HSC activation45, 46. In mice with HSC-specific deletion of autophagy-related protein 7 (Atg7), HSC activation following liver injury is reduced, leading to diminished fibrosis in vivo46. Further, inhibition of autophagic function in cultured mouse HSCs and in mice following injury attenuates fibrogenesis and matrix accumulation47. Thus, available data suggest that autophagy stimulates HSC activation, and that its inhibition could eliminate activated HSCs in vivo.

Cellular senescence, the phenomenon by which normal diploid cells cease to divide and reduce the cell’s ability to proliferate, is a potential mechanism underlying fibrosis regression. Cellular senescence and reduced HSC proliferation may play a role in ECM degradation33, 48, 49. A new approach includes use of chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells, T cells that are engineered to kill cells expressing specific cell surface markers 50. A recent study used this technique to destroy HSCs expressing the senescence marker, urokinase plasminogen activated receptor, which reduced fibrosis in mouse models51. Thus, a subset of senescent HSCs may be critical in fibrosis progression, but their contribution to fibrosis regression is unclear.

Immune cells, in particular macrophages, are strongly implicated in regression of fibrosis52–55. During liver injury, activated resident Kupffer cells and “inflammatory” macrophages secrete proinflammatory, (i.e., IL-1β and TNFα), and profibrogenic (TGFβ) cytokines, which initiate/perpetuate hepatocellular injury, and stimulate fibrosis, respectively. Recent investigation indicates that murine macrophages express triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM-2) in experimental NASH, and have a pro-fibrogenic role56. In contrast, during fibrosis regression, “restorative” macrophages are recruited to promote degradation of ECM (‘Ly-6Clo’ macrophages in mice; CD14+ macrophages in humans). However, the identity and cellular source(s) of the key proteases responsible for matrix degradation in human liver disease are unknown and a major unanswered question in the field. In aggregate, the balance between the different types of hepatic macrophages appears to play a critical role in determining fibrosis progression and regression.

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Fibrosis Reversal

The ECM is dynamic and complex, not only in its localization within the liver, but also in its composition and quantity. As fibrosis progresses, the normal low density basement membrane-like matrix is overtaken by high-density interstitial matrix, comprised of interstitial collagens, glycoproteins and proteoglycans57, 58. The latter type of matrix is typically found in large bands in the liver, and helps generate fibrotic nodules. The ECM may further influence net fibrosis by altering the behavior and function of all resident liver cells59.

Although molecules responsible for ECM remodeling have been a focus of interest for years, we still do not know which cells and proteases account for the remarkable capacity of the liver post-SVR to resorb fibrosis. MMPs, their inhibitors (TIMPs), and several converting enzymes (MT1-MMP, and stromelysin, for example) are described in human liver, yet how these influence net proteolytic activity in vivo remains obscure. Overall, there is downregulation of MMP1 (interstitial collagenase, collagenase I) and upregulation of MMP2 (gelatinase A) and MMP9 (gelatinase B)60. These activated MMPs are regulated in part by their tissue inhibitors, or TIMPs, as noted above. TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 are up-regulated relative to MMP1 in progressive liver fibrosis, which may explain decreased degradation of interstitial type matrix in liver injury. HSCs may also promote their own activation through cleavage of collagen by MT1-MMP61. During resolution of experimental liver injury, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 expression are decreased, while collagenase expression is unchanged, resulting in a net increase in collagenase activity and increased resorption of scar matrix60.

Chemical cross-linking of collagen can also influence its susceptibility to degradation and turnover. For example, lysyl oxidase (LOX) enzymes promote collagen cross-linking and stabilization; thus, inhibition of LOX may promote collagen degradation. An animal study using a monoclonal antibody targeting LOXL2 inhibited both liver and lung fibrosis62. These data led to a clinical trial of a LOXL2 antibody (simtuzumab) in patients with NASH and bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis, which failed to reverse fibrosis or lower poral pressure63. The antibody may have been inactive because it did not adequately reach areas of matrix accumulation, raising the possibility that small molecule LOXL2 inhibitors (i.e., chemical compounds that are < 900 Daltons, so they can be orally administered and absorbed) may be better able to penetrate the ECM to inhibit cross-linking.

The Role of Hepatic Regeneration in Fibrosis Regression

The liver’s unique regenerative capacity may explain why most chronic liver diseases require decades to progress to end-stages, in contrast to less regenerative organs like kidney and lung in which injury may culminate in organ failure within 3 to 5 years from onset of disease. Highly fibrotic liver progressively loses the capacity for regeneration, which may be a critical determinant of incipient liver decompensation. This mutually antagonistic relationship between regeneration and fibrosis raises the possibility that the regeneration response could include innate antifibrotic or matrix degradative activity, and conversely, highly fibrotic liver has lost the capacity to regenerate. While signals underlying this bidirectional relationship are poorly characterized, modest experimental evidence64 supports the concept that regeneration inhibits fibrogenesis. Moreover, there are a number of signals that concurrently promote regeneration and suppress fibrosis, including HGF agonism and TGFβ1 antagonism65, HNF4α66, chemokine signaling by sinusoidal endothelial cells67, endosialin68, as well as recruitment of liver progenitor cells69. Although it is currently unknown whether these soluble or cellular factors can regress fibrosis while promoting regeneration, the development of regenerative molecules such as Wnt ligands70 may clarify the relationship between regeneration and fibrosis. Finally, it is possible that certain hepatic macrophages may promote regeneration in fibrotic liver by conferring protection against hepatocyte cell death71, 72.

Clinical aspects of fibrosis and cirrhosis reversion

Overview

Currently, hepatic fibrosis regression occurs through elimination of the underlying disease. Evidence exists in multiple diseases including HBV73–77, including delta hepatitis78, hemochromatosis79, 80, removal of alcohol in alcoholic liver disease81, decompression of biliary obstruction in chronic pancreatitis82, immunosuppressive treatment of autoimmune liver disease83, and treatment of schistosomiasis84, and others. Weight loss85 and bariatric surgery may also promote fibrosis regression in NASH86. Evidence is now rapidly emerging in HCV, including specifically in patients with established cirrhosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fibrosis reversal in cirrhosis after HCV SVR*

| Study | Therapy | n | Followup | Outcome assessed by | Key finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Poynard (2002) | IFN based | 153 | 12 months | Liver histology | 75 patients had a reduction in Metavir fibrosis stage (23 to stage 3; 26 to stage 2; fibrosis score declined from 4 to 1.9 overall |

| # Metwally (2003) | IFN based | 34 | 12 months | Liver histology | 11 patients had regression from Metavir stage 4 to stage 3 (7 patients) or stage 2 ( |

| Mallet (2008) | IFN based | 35 | Median 17 months | Liver histology | 17 patients had regression from Metavir stage 4 to stage 2, 1, or 0 |

| D’Ambrosio (2012) | IFN based | 38 | Median 61 months | Liver histology | 72% overall reduction in type I collagen assessed morphometically |

| Poynard (2013) | IFN based | 43 | Median 76 months | Blood markers | 24 of 43 patients had regression defined as 20% reduction in serum fibrosis marke |

| Carton (2013) | IFN based (HIV coninfected) | 12 | Median 38 months | TE | 8 of 12 patients had regression and the other 4 patients were unchanged |

| Knop (2016) | DAA | 50 | 6 months | TE, AFRI | 88% of patients had a reduction in stiffness; median values declined from 32.4 to 2 |

| Martini (2017) | DAA (post – transplant) | 51 | 48 weeks | TE | Median liver stiffness declined from 20.4 (baseline) to 17.5 to 14.0 kPa at 24 and 4 also declined) |

| $ Mauro (2018) | IFN based/DAA (posttransplant) | 37 | 12 months | Liver Histology | 16/37 patients had evidence of regression (of at least 1 Metavir stage) |

| ^ Rout (2019) | DAA | 95 | 12 months | TE | The percentage of patients with cirrhosis (25.5%) at baseline decline up |

| Kawagishi (2020) | DAA | 23 | 12 months | TE | 9 patients had regression, including 4 to stage 0–2 |

| Prakash | DAA | 90 | 24 months | FIB-4 | 39% had reduction in FIB-4 to below 2.67 (predefined cirrhosis thresh |

Patients included had viral eradication and in all studies except 2 had SVR. Studies that did not include specific details of viral eradication, very small numbers of patients, or specifics of fibrosis stage are not included in this table

Not all patients had an SVR (fibrosis was assessed at end of treatment)

51% of patients treated had a decompensating event prior to treatment

Excluded patients with decompensation

It is important to recognize that from a conceptual standpoint, fibrosis is likely to regress to different degrees in different patients (Figure 3). That is to say that some patients will be expected to have minimal regression, while others may have pronounced regression. We currently do not fully understand the variables that most strongly influence the degree of regression.

Figure 3. Conceptual framework of fibrosis regression.

Fibrosis progression typically progresses from F0 to F4 (in HCV, Metavir); It is likely that fibrosis regression varies widely in different individuals. For example, it is possible that fibrosis regression may be complete or nearly complete in some patients, yet may be minimal or absent in others. Further, it is likely that the less severe fibrosis is to begin with, the better the chance that the liver returns to normal or near normal (i.e. from F1 to F0 or F2 to F1/F0). In contrast, the more severe the fibrosis is to begin with, the less likely the liver is to revert to a normal architecture. It is however, possible that some patients may exhibit substantial fibrosis reversion (i.e. from F3/4 to F0/1). It should be emphasized that despite regression of fibrosis, some degree of architectural abnormality and elements of disturbed blood flow may persist.

Given the evidence that fibrosis regresses even in patients with cirrhosis (Table 2), it is important to appropriately define cirrhosis when assessing responses following SVR. A clinico-pathological definition is most practical, in which there is objective evidence of advanced fibrosis (demonstrated histologically, or by imaging) as well as clinical evidence of liver disease, either portal hypertension and splenomegaly, esophageal varices, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy. Nonetheless, not all forms of “cirrhosis” are necessarily the same. For example, some patients with histologically defined cirrhosis will remain entirely asymptomatic, while other patients who have evidence of portal hypertension are likely to develop complications. Several groups have tried to classify cirrhosis into subgroups87–90, raising the question as to which pathologic features portend clinical complications of cirrhosis. A biopsy-based study has identified smaller nodule size, septal thickness and loss of portal tracts and central veins as associated with clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH, i.e., portal hypertension sufficient to cause serious complications including ascites, variceal hemorrhage, and/or hepatic encephalopathy)91. Notwithstanding, there is progression of clinical disease within cirrhosis90, likely related to the degree of parenchymal fibrosis, fibrosis-mediated architectural abnormalities, and/or portal hypertension severity.

Clinical Considerations in Fibrosis Regression

Which patients with cirrhosis have clinically significant fibrosis regression?

While there is no standardized definition of “clinically significant fibrosis regression”, we propose that the term is best used to indicate fibrosis regression sufficient to improve clinical outcomes, either in reducing the likelihood of decompensation with complications of portal hypertension (development of ascites, varices) or encephalopathy, or by reducing the risk of HCC. Although HCV clearance is associated with fibrosis reversion/reversal in many patients, it is not established which histologic or clinical features predict who will regress after SVR. Two studies indicate that patients with low pre-treatment HCV RNA levels may be more likely to have regression of hepatic fibrosis after interferon-based therapy92, 93. Interestingly, following SVR, a small fraction of patients (12% in one study), may have progressive liver disease94. While in most cases this is likely due to other co-morbid causes of liver disease (e.g., alcoholic or NASH), progression may be unexplained in some patients95.

HCV eradication with interferon-based therapy compared to DAA based therapy

Both IFN based and DAA therapies lead to HCV elimination; however, the mechanism of viral clearance differs between the two. Regardless, interferon-based therapies have been abandoned in favor of DAA regimens. Indirect evidence for a difference between the effects of interferon- and DAA-based therapies comes from a study96 in which the waitlist mortality of HCV patients was examined in different time delimited cohorts of patients (including cohorts with SVR before or after January 1, 2014), with the assumption that those on the waitlist after January 1, 2014 received DAA therapy. Compared with patients treated in the pre-DAA era, the mean rate of increase in MELD score was less in those treated with DAAs. Although these data are retrospective and therefore must be interpreted with caution, they raise the possibility that DAA therapies may yield a more favorable impact on outcomes than interferon-based ones.

Expectations for fibrosis regression after SVR

In the absence of effective HCV treatment, fibrosis typically progresses inexorably over time. In one study of untreated Ishak stage 2–4 HCV patients, the median increase in collagen was 27% over 52 weeks, associated with a median increase in smooth muscle actin labeling (a marker of hepatic HSC activation) of 49% - indicating active fibrosis progression97. In the HALT-C trial, which evaluated the effect of maintenance peginterferon-ribavirin therapy, the main group of 346 nonresponders had a mean fibrosis increase of 61% over pretreatment baseline after 2 years and 80% after 4 years98. Of note, these studies included patients with a wide range of baseline fibrosis; whether patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis progress at the same rate as patients with less severe baseline fibrosis is not clear. However, even with histological cirrhosis, fibrosis continues to progress97.

How much fibrosis regression should be expected following SVR? In one detailed histological study following interferon-based HCV eradication using paired pre- and post-treatment liver biopsies obtained a median of 61 months after interferon-based therapy leading to SVR from 38 HCV patients with cirrhosis and an SVR (with interferon-based therapy), fibrosis was staged using the METAVIR scoring system, and the area of fibrosis was measured using morphometry99. The collagen content decreased in 34 of 38 patients (89%), with a 72% median individual reduction in collagen content. Importantly, although meaningful fibrosis regression may occur, the degree to which the architecture of the liver repairs and/or returns to normal is unknown.

Overall, 1/3rd-2/3rd of patients with HCV eradication will have some reduction in fibrosis, although patients with cirrhosis appear to regress less than those with less severe fibrosis92, 93, 99–109. There are caveats, however; first, many early studies of reversal studies were performed in patients treated with interferon-based therapy, and it is not known whether fibrosis reversion is similar between the two types of HCV treatment (see above). Second, data in the DAA era are limited by the short duration of follow-up after HCV elimination. Third, while early studies used histological assessment to measure fibrosis reversion, more recent studies have characterized the response to therapy using noninvasive assessments103, 106, 107, 110–112 (and Table 2). Although noninvasive assessments may not be as robust as histological assessment, trends toward fibrosis reversal are clear. Notwithstanding, it is critical to recognize that many currently used non-invasive approaches are confounded by the inflammatory response (for both blood markers and liver stiffness), and therefore, may lead to the conclusion that fibrosis reversal is more pronounced because the inflammatory response has been attenuated.

A long-term follow-up study of 415 HCV patients with advanced baseline fibrosis conducted repeated non-invasive assessments of fibrosis (FibroTest and transient elastography)101; 108 achieved SVR with interferon-based therapy, and 49% of these exhibited a > 20% reduction in FibroTest scores, which was greater than in 219 non-responders (23%; p < 0.001 vs. SVR)]. In patients with cirrhosis, regression occurred in 24/43 patients, but new cirrhosis developed in nearly 15% of other patients with SVR101. Another large study followed 4731 patients with HCV infection long-term, of whom 1657 were treated and 755 achieved SVR; over a 10-year period, there was an overall reduction of 22% in fibrosis in patients who had an SVR113. Moreover, SVR was associated with long-term maintenance of fibrosis regression.

Fibrosis reversion has also been studied in several special groups, including those with recurrent HCV after transplantation, and HIV/HCV coinfected patients. In a study of post transplantation HCV (largely patients with F0-F1 fibrosis), eradication of HCV with interferon-based therapy led to a dramatic reduction in fibrosis progression compared to nonresponders/relapsers114. Additionally, in the SVR group, 13% progressed to fibrosis stage ≥ 3 on post-treatment biopsies vs. 38% in the non-response/relapse group (p=0.001). Another study of 77 patients after liver transplantation found that SVR with DAA therapy led to significant fibrosis regression104. Finally, in 112 patients with HCV recurrence and treated after liver transplantation, there was significant regression of fibrosis in all fibrosis stages105 and 43% of patients had at reduction in at least 1 fibrosis stage. Additionally, in the 34 patients with who met the authors’ definition of cirrhosis, liver stiffness decreased from 25.3 (16.5–32.8) to 14.5 (9.9–22.1) kPa (P < 0.001).

In 133 HCV-HIV-coinfected patients with cirrhosis followed for a mean of 6.8 years (916.8 person-years), fibrosis as measured by liver stiffness appeared to regress in 23/42 (55%) of patients after interferon-based SVR, while 14/91(15%) of patients without an SVR had fibrosis regression115. Further, in Cox survival analysis, fibrosis regression was associated with a lower risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio, HR=0.36), and liver-related death (HR=0.15), emphasizing the importance of fibrosis regression in HCV-HIV patients.

Measurement of fibrosis regression

The clinical staging of fibrosis has been an obstacle to accurate assessment of fibrosis regression after SVR. A complete discussion of fibrosis assessment is beyond the scope of this review. In brief, liver histology is considered the gold standard to stage fibrosis, but liver biopsy is invasive and subject to sampling error15. A variety of methods ranging from the use of physical findings, to routine laboratory tests such as platelets alone, blood based test algorithms using routinely available blood tests, or even serum markers of fibrosis (i.e. TIMP-1, MMP2, collagen I, III, IV, hyaluronic acid, and others) have been studied extensively in patients with HCV. Serological markers of collagen turnover (i.e., cleavage fragments of collagen) are particularly attractive as potential biomarkers for fibrosis regression but need validation116. The APRI or FIB-4 are also appealing because of their simplicity of use. However, blood tests typically have a high sensitivity and specificity for detection of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, but are not highly sensitive or specific for less advanced stages of fibrosis117.

Imaging, in particular, vibration control transient elastography (also called transient elastography (TE)) and magnetic resonance elastography, are attractive to stage fibrosis because they are non-invasive. TE has been studied extensively in HCV118, and is highly specific when liver stiffness is at an extreme (low - rules out advanced fibrosis; high - consistent with advanced fibrosis). However, it is inaccurate at intermediate levels of stiffness118. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is more sensitive because it is noninvasive and images a large area of the liver, which may reduce sampling variability reflecting the heterogeneity of fibrosis distribution. Few studies have compared TE and MRE in patients with HCV cirrhosis and following SVR. MRE leads to more false positive diagnoses of cirrhosis than TE in patients with HCV119. TE may also be limited by high failure rates in patients with narrow intercostal spaces and ascites, or interference with extrahepatic cholestasis, hepatic inflammation, and steatosis. TE likely overestimates fibrosis regression after HCV clearance because of the rapid decrease in inflammation typical of DAA therapy, since inflammation also increases stiffness.

Effects of HCV elimination and fibrosis reversion on clinical outcomes

The evidence that HCV eradication in all patients as well as specifically in patients with baseline cirrhosis (Table 3) leads to improved clinical outcomes is steadily accumulating, not only following interferon-based therapy but also in the DAA era 100, 103–105, 120–131. The effects of HCV elimination are broad, and include an overall reduction in mortality in patients with advanced fibrosis, a reduction in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced fibrosis (see below), as well as a reduction in extrahepatic manifestations including HCV-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, other lymphoproliferative disorders, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis120, 121, 123, 124, 132–136. Since the degree of fibrosis appears to be a key driver of the complications of cirrhosis, a focus on the natural history of fibrosis progression and regression is important. However, the evidence that fibrosis reversion drives improved outcomes after HCV eradication is largely correlative.

Table 3.

Outcomes in cirrhosis after HCV SVR

| Study | Therapy | n | Followup | Outcome | Key finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veldt (2007) (Ishak 4-6) | IFN based | 142 | 11 and 19 months | Clinical liver events | At the end of followup, there were 4 events in 142 patients with SVR and 83 events in 337 nonresponders |

| Mallet (2008) | IFN based | 96 | Median 17 months | Clinical liver events | Liver related death and complications were reduced in patients with SVR vs. those without, and in patients with cirrhosis regression vs. those without |

| Di Marco (2016) | IFN based | 106 | Median 7.6 years | Decompensating events, death | No patient without esophageal varices and an SVR (n = 67) developed a subsequent liver decompensation event. For death, 0.4% per year vs. 2.1% per year for non-SVR patients and 1.8% per year for SVR patients and 4.6% per year for non-SVR patients for patients without and with esophageal varices, respectively |

| Knop (2016) | DAA | 54 | 6 months | MELD | MELD was reduced from 9 to 8 during the followup period, bilirubin increased, and albumin increased |

| Belli (2016) | DAA | 103 | 60 weeks | MELD/CP | MELD was reduced by 3.4 points, CP reduced by 2 points |

| * Foster (2016) | DAA | 409 | 5 months | MELD | MELD (baseline = 11) was reduced by 0.85 MELD points in treated patients, and new decompensation events were reduced nearly 3 fold in treated patients compared to untreated controls |

| Martini (2017) | DAA (post transplant) | 72 | 6 months | Clinical liver events | (post-OLTx) Ascites resolved in 15 of 72 patients. Child Pugh score decreased, but there was no change in MELD score |

| Hill (2018) | DAA | 196 | 18 months | Clinical liver events | 29.1 hospitalizations per 100 person years in the control (HCV untreated) group compared to 10.4 hospitalizations per 100 person years in the DAA group |

| Janjua (2018) | IFN and DAA based | 1021 | 9.5/2 years | Clinical liver events | Reduction in mortality was similar among those with cirrhosis in both interferon (aHR=0.29, 95%CI:0.210.39) and DAA (aHR=0.28, 95%CI: 0.2-0.4) groups, respectively |

| Mauro (2018) | IFN based/DAA (post-OLTx) | 37 | 12 months | Clinical liver events | MELD declined from 10 to 9, and Child-Pugh score 6 to 5, bilirubin increased. Two of 37 patients had a decompensating event during followup, while 51% had a decompensating event at baseline |

| # Moon (2019) | DAA | 9399 | 3.1 years | Variceal bleeding | Variceal bleeding was reduced in cirrhotics with SVR compared to those without SVR (1.55 vs. 2.96 episodes per 100 patient years) |

| Prakash (2020) | DAA | 90 | 24 months | MELD | In patients with fibrosis regression, MELD decreased from 10 at baseline to 7, while in patients without fibrosis regression, MELD increased from 10 at baseline to 11. |

Included only decompensated patients, SVR rate of 81% in 409 patients

SVR in 7927

DAA-mediated elimination of HCV in cirrhotic patients yields robust improvements in the rate of complications and clinical outcomes (see103, 104, 125, 126, 128–131, 137, 138,139,109 and Table 3). In a study of DAAs in cirrhotic patients from the UK126, those treated with DAAs had a mean reduction in MELD score of 0.85 (SD 2.54), while untreated patients had a mean increase in MELD score of 0.75 (SD 3.54) (p <0.0001). This is notable since patients included in this study had extremely advanced disease. In a study128 comparing two cohorts with HCV cirrhosis (a DAA cohort (n=196), and a control cohort that did not receive HCV therapy over a similar time frame (n=182)), the incidence of liver-related hospitalizations, HCC, liver transplant, and death were measured (the median followup was 18 and 20 months, respectively). The SVR for the treated group was 87%, including 89% (122/137) in Child Pugh-A and 81% (48/59) in Child Pugh-B/C. The hospitalization rate was 29.1 hospitalizations per 100 person-years in the control group compared to 10.4 in the DAA group (p < 0.0001). However, there was no difference in the incidence of hospitalizations in CTP-C patients and during the short follow-up time there were no differences in the incidence of HCC, liver transplant, or death between the cohorts.

Long-term mortality was examined in a large study using utilizing the British Columbia (BC) Hepatitis Testers Cohort dataset, which included 14,033 patients: 5,169 received DAAs while 8,864 received interferon-based treatments that were followed for a median of 2.0 and 9.5 years, respectively129. In a model of patients with cirrhosis (n=660 for DAAs; 1021 for interferon-based therapy), the reduction in mortality was similar among those with cirrhosis in both groups (aHR=0.28, and aHR=0.29, respectively). Finally, in an analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) database, the rates of waitlisting for liver transplantation for HCV decreased by over 30% since DDA therapy was introduced140.

In patients with baseline cirrhosis that is not severely decompensated, improvement in fibrosis will likely drive clinical improvement, including in those with portal hypertension (see also below). The more severe the underlying liver disease (especially in those with advanced fibrosis and portal hypertension), the less likely for the patient avoid subsequent complications. However, some patients with even advanced liver disease and complications may improve – raising the question as to whether there is a “point of no return”, as discussed above.

Effects of SVR on Portal Hypertension

SVR of HCV reduces portal hypertension, measured by HVPG. Improvement in portal hypertension has been reported following use of both interferon-based and DAA regimens. In one small study of patients with HCV-induced cirrhosis who had an SVR after 48 weeks of peginterferon/ribavirin treatment, there was a small, but significant decrease in HVPG patients with SVR compared to nonresponders (−2.1 +/− 4.8 vs 0.6 +/− 2.8 mm Hg; P=0.05)22. In a long-term study of cirrhotic patients, no patient with an SVR developed esophageal varices, compared to 32% of untreated patients141.

In a study of 226 patients with relatively advanced cirrhosis (75% had esophageal varices, 21% were Child-B, and 29% had at least 1 previous episode of liver decompensation), DAA-mediated SVR led to an overall decrease in HVPG (15 mmHg before treatment to 13 mmHg after SVR (p < 0.01))23, though CSPH (HVPG ≥ 10 mm Hg) persisted in 78% of patients. Another study in DAA treated patients found a median overall decrease in HVPG of 31%138; the greatest and most consistent changes were observed in patients with mild portal hypertension at baseline (baseline HVPG of 6–9 mmHg). In a followup study by the same group that included an additional 30 patients, 67 patients were found to have CSPH 142, with a mean baseline HVPG of 16.2 mmHg. At an average of 6.6 months after completion of DAA therapy, HVPG was reduced by 2.6 mm Hg, and in the subgroup of 40 patients with an HVPG decrease of > 10%, the reduction in HVPG was 5.1 mmHg on average (vs. a 0.9 increase in mmHg in the 27 patient without an HVPG decrease of > 10%, p < 0.001). Finally, in a study of 33,582 DAA-treated VA patients, SVR was associated with a significantly lower incidence of variceal bleeding among all patients, including in patients with pre-treatment cirrhosis130. Although effects of SVR on portal hypertension are apparent, more data are required to determine whether there is a threshold beyond which normalization of HVPG is unlikely after SVR.

Finally, evidence in patients with recurrent HCV post-transplant also reinforces the potent clinical impact of SVR. In HCV patients with F4 fibrosis who had a sustained virologic response to therapy (primarily interferon-based) and paired HVPG pre- and post- treatment, HVPG decreased from 12 to 8.5 1) mm Hg (P < 0.001); moreover, two-thirds of patients with cirrhosis had some reduction in HVPG105.

Although improvement in portal hypertension after HCV clearance may be possible, this improvement may not occur in all patients. A detailed histological analysis after SVR in patients with cirrhosis failed to demonstrate reduced sinusoidal capillarization99, raising the possibility that effects on portal hypertension may be limited by persistent fibrosis in the subendothelial space. Further, the data on fibrosis reversion and reduction in HVPG are largely correlative – and we don’t know whether matrix changes after HCV clearance lead to fundamental normalization of vascular physiology in the liver (particularly in patients with advanced cirrhosis at baseline). Finally, a preliminary study in decompensated patients found that HCV eradication did not improve ascites after one year of follow-up143.

Effects on SVR on Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Although some studies and a meta-analysis demonstrated a reduction in HCC risk after interferon-based therapy123, other reports suggested that HCC risk was increased after HCV elimination by DAAs144–147. However, more recent, methodologically sound studies document a reduced risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma after SVR with DAA therapy as well148–150. For example, in a large Veterans Affairs (VA) study of 62,051 patients, SVR was associated with a significantly decreased risk of HCC irrespective of whether the antiviral treatment was IFN-only, DAA±IFN, or DAA-only148.

It is unclear whether a reduction in inflammation or fibrosis, the direct elimination of HCV, or both, reduce the risk of HCC. On one hand, the relative risk reduction for development of HCC after DAA therapy appears to be similar in patients with and without cirrhosis148, suggesting that fibrosis may not be the driver. On the other hand, patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis at the time of DAA treatment represent the highest-risk group for HCC after HCV elimination151. Since DAAs lead to the elimination of HCV but not fibrosis reversion, long-term natural history studies examining the risk of developing HCC after DAA induced SVR will need to address this question.

Monitoring for HCC development after HCV elimination

Optimal management of patients following SVR is no yet clarified. This is particularly true in patients who had advanced fibrosis at the outset of antiviral treatment, including those with clinically compensated cirrhosis. Molecular analysis of liver tissue may identify high-risk gene signatures that predict a greater risk of HCC152. HVPG might be useful to identify those with CSPH. However, HVPG is invasive and not easily performed in most patients, although it might still be useful in cirrhosis. Regardless, the risk of HCC is increased in patients with fibrosis at the time of SVR, and therefore HCC screening should be continued indefinitely after SVR until more data are available.

The role of primary anti-fibrotic treatments after HCV eradication

It is currently unknown whether primary antifibrotic treatment will be indicated in patients with cirrhosis and SVR once such drugs are approved. On one hand, it is clear that some patients have enough fibrosis reversion to reduce portal hypertension and limit clinical complications. On the other hand, it is very clear many patients do not regress, making primary antifibrotic therapy attractive. Although attempts have been made to specifically treat the “fibrosis” component of liver disease in patients with HCV, they have been unsuccessful (97, 153 and see3, 4 for review). These studies must be interpreted in context for the following reasons: First, virtually all primary anti-fibrotic trials to date have been conducted in HCV non-responders. This situation will become rare since DAA therapy will remove HCV (with concurrent inflammation that drives fibrosis) in almost all patients. Second, the compounds used in anti-fibrotic trials to date may not have been sufficiently potent, and/or their cellular targets well validated. Nonetheless, although ongoing large phase 3 trials in patients with NASH fibrosis hold promise, there is still no anti-fibrotic drug to treat HCV-associated liver fibrosis.

Antifibrotic Treatment in Patients with Residual Fibrosis

Once the natural history of fibrosis regression after SVR of HCV is clarified over the coming years, anti-fibrotic therapies will be likely indicated for patients with residual cirrhosis (or advanced fibrosis) that has not resolved. At present, a challenge is that direct anti-fibrotic therapies in HCV patients post-SVR will be compared to the ‘moving target’ of natural regression. If variables indicating irreversibility after SVR can be clarified, selection of suitable candidates for antifibrotic therapies, without awaiting evidence of persistent advanced fibrosis, may be possible. Alternatively, patients with evidence of longstanding fibrosis long after SVR (e.g. > 3–5 years) may benefit from antifibrotic therapies without waiting further. While the optimal patient population who will benefit from antifibrotic therapy post SVR is not well defined, most would agree that those with persistent cirrhosis, especially with portal hypertension, would be the best candidates.

Based on the premise that antifibrotic therapy will be largely restricted to cirrhotic patients, treatments will need to directly or indirectly promote antifibrotic activity to resorb scar and not simply reduce ongoing injury. Ideally, they should also stimulate regeneration and reduce portal hypertension. Whether the latter is possible remains uncertain, as collapse of terminal hepatic venules in advanced cirrhosis contributes to portal hypertension that may not be reversible20. Nonetheless, the remarkable resilience of the liver and its unique capacity for regeneration suggest that improvement may some day be possible, even in those with cirrhosis and CSPH.

Current and potential antifibrotic therapies

Drugs either currently under evaluation or worth exploring that meet the requirements listed above are currently limited to agents that: 1)Directly reduce the number or fibrogenic activity of activated HSCs; 2)Promote macrophage-mediated matrix degradation; 3)Stimulate hepatic regeneration. Anti-fibrotic agents currently in clinical trials are being testing largely in patients with NASH or primary sclerosing cholangitis, and new trials would need to be launched for HCV post-SVR. Moreover, a growing list of potential antifibrotic agents have failed to show efficacy in NASH, and are not listed here; they are unlikely to be re-evaluated in HCV post SVR154 (see ClinicalTrials.gov). On the other hand, there are several agents that may be antifibrotic, yet their efficacy is not firmly established (See Supplemental Figure 1 and 4 for review). A clear example are the statins, for which preclinical data 155, 156 as well as clinical evidence of an antifibrotic effect is emerging 157, 158. However, large, carefully designed clinical trials will be required to establish the effectiveness of statins on fibrosis regression.

Agents that directly reduce the fibrogenic activity or number of activated HSCs

A liposomal formulation that delivers an shRNA targeting heat shock protein 47 (hsp47, required for proper collagen folding) directly to HSCs159 leads to accumulation of misfolded collagen, which promotes HSC apoptosis to reduce the number of fibrogenic cells61. A phase 2 trial using this formulation in patients post HCV SVR is underway, with improvement in histology as the primary endpoint (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03420). The renin-angiotensin system s up-regulated in HSCs and cirrhotic liver160, 161, and RAS inhibitors have potential antifibrotic activity by reducing activation of the fibrogenic cytokine TGFβ1162. A clinical trial is currently testing the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan in cirrhosis (NCT03770936). Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a contractile peptide that also promotes HSC activation163, and a clinical trial is currently testing the effect of an ET-1 receptor blocker in cirrhotics on reducing HVPG (NCT03827200).

As noted above, several drugs are being evaluated for NASH-related fibrosis (reviewed in164, 165), some of which may have antifibrotic activity in other fibrotic liver diseases such as HCV. These include a CCR2/CCR5 chemokine receptor antagonist166, 167, antagonists to interleukin-11168, and galectin antagonists169, 170.

Agents that promote macrophage-mediated matrix degradation

Because macrophages are likely to be key fibrolytic cells in liver, macrophage therapy is being explored in cirrhosis. A recent trial has established the safely of administering CD14+ autologous macrophages to cirrhotic patients171 since the analogous macrophage subtype in mice is an effective therapy in models of cirrhosis. However, a trial of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and autologous CD133-positive stem-cell therapy, which was intended to amplify restorative macrophages, was well tolerated but had no effect on outcomes172. These early findings establish the feasibility of targeting macrophages in cirrhosis, and build on other studies using cell-based therapies in cirrhosis, including several testing mesenchymal stem cell therapy173, yet none has been proven effective in a rigorous controlled trial. Efforts to stimulate macrophage reprogramming have been tested in clinical trials for lung fibrosis through the administration of pentraxins, which can attenuate inflammatory macrophage activity 174. Serum amyloid P, a naturally circulating pentraxin, is effective in experimental renal fibrosis175–177 and a trial in pulmonary fibrosis yielded promising results178, 179 but no trials are underway yet in liver.

Therapies to stimulate hepatic regeneration.

While there are no approved therapies to stimulate liver regeneration directly, there is strong reason to believe that doing so will have a fibrolytic effect on existing matrix in cirrhotic liver. As noted above, animal data link improved regeneration with degradation of fibrosis, and this may also be true in patients with SVR who exhibit fibrosis regression along with improved liver function. Among the prospects to promote regeneration therapeutically based on animal data are administration of HNF4α66, Wnt ligands70, as well as cell-based therapies (reviewed in173, 180). Further studies in animal models and humans will further clarify mechanistic links between regeneration and fibrosis that will advance prospects for effective therapy of fibrosis.

Summary and Future Prospects

Fibrosis regression is associated with broad clinical benefit and remains an important therapeutic goal in patients with HCV SVR who have advanced fibrosis that does not improve spontaneously after virologic elimination.

There remain substantial gaps in our knowledge about both the biology of fibrosis regression and its clinical features. From a mechanistic perspective, there needs to be far more clarity about the regulation of fibrosis regression, specifically, which proteases are required to degrade scar, what are their cellular sources, and how are they regulated both within cells that produce them and in the extracellular space where they can be antagonized by circulating inhibitors (e.g., tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, or TIMPs). Recent exciting data have begun to define specific subsets of macrophages in mice called ‘Ly6Clo’ cells which are linked to fibrosis regression 181, but how they promote extracellular matrix degradation, what are their human counterparts, and are other cells involved are all vexing questions that need to be addressed in order to exploit these pathways in the form of new treatments. Finally, as noted above, it is not known which cellular and molecular events allow a healthy liver to regenerate without fibrosis, or block regeneration when there is more advanced fibrosis.

From a clinical perspective, remaining gaps include determining which patients can expect significant fibrosis reversal after HCV elimination, what factors influence fibrosis regression (including, can fibrosis regression be predicted based on clinical parameters?), and whether there are genetic determinants of fibrosis regression, as there are for fibrosis progression. Moreover, how can we assess fibrosis regression without relying on liver biopsy, and what implications will non-invasive evidence of regression have on patient management and HCC screening? And most importantly of all, can we leverage this information to optimize diagnosis and treatment of fibrotic liver disease to induce regression of existing scar in order to improve outcomes and reduce risk of HCC. With these questions yet to be answered, the management of cirrhosis in patients post SVR will likely evolve, and continued study of these patients will yield progress that should significantly improve management of advanced fibrotic liver disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, R01 DK 098819, DK113159, P30 DK123704, and R01 DK56621.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: DCR has no financial arrangements (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interests, or patent-licensing arrangements) with a company whose product figures prominently in this manuscript or with a company making a competing product. His institution receives or has received research grant support within the last 12 months from the following: Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Galectin Therapeutics, Genfit, Gilead Sciences, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Sequana Medical. SLF has the following relationships: Consulting - 89 Bio, Axcella, Blade, Bristol Myers Squibb, Can-Fite Biopharma, ChemomAb, Escient, Forbion, Galmed, Genevant, Gordian Biotechnology, Glycotest, Glympse Bio, Morphic Therapeutics, North Sea Therapeutics, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Scholar Rock, Surrozen; Stock or Stock options - Blade Therapeutics, Escient, Galectin, Galmed, Genfit, Glympse, Intercept, Lifemax, Madrigal, Metacrine, Morphic Therapeutics, Nimbus, North Sea Therapeutics, Scholar Rock, Surrozen.

Abbreviations:

- DAA

direct acting anti-viral

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- HNF4α

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha

- hsp47

heat shock protein 47

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease

- TNF-α

transforming growth factor alpha

- TREM-2

triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2

Footnotes

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria:

Searches in English were performed using PubMed, for hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, reversion, reversal, regression, experimental models, HCV treatment, liver biopsy, outcomes. Reference lists of manuscripts on the subject of fibrosis reversion in patients with HCV were reviewed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:448–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockey DC, Bell PD, Hill JA. Fibrosis--a common pathway to organ injury and failure. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1138–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockey DC. Translating an understanding of the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis to novel therapies. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 2013;11:224–31 e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iredale JP, Benyon RC, Pickering J, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest 1998;102:538–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Issa R, Zhou X, Constandinou CM, et al. Spontaneous recovery from micronodular cirrhosis: Evidence for incomplete resolution associated with matrix cross-linking. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1795–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popov Y, Sverdlov DY, Sharma AK, et al. Tissue transglutaminase does not affect fibrotic matrix stability or regression of liver fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1642–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massard J, Ratziu V, Thabut D, et al. Natural history and predictors of disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2006;44:S19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang H, Shiffman ML, Friedman S, et al. A 7 gene signature identifies the risk of developing cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2007;46:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eslam M, McLeod D, Kelaeng KS, et al. IFN-lambda3, not IFN-lambda4, likely mediates IFNL3-IFNL4 haplotype-dependent hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Nat Genet 2017;49:795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rueger S, Bochud PY, Dufour JF, et al. Impact of common risk factors of fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2015;64:1605–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poynard T, Mathurin P, Lai CL, et al. A comparison of fibrosis progression in chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol 2003;38:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruden DJT, McMahon BJ, Townshend-Bulson L, et al. Risk of end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related death by fibrosis stage in the hepatitis C Alaska Cohort. Hepatology 2017;66:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagstrom H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, et al. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy-proven NAFLD. J Hepatol 2017;67:1265–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, et al. Liver biopsy. Hepatology 2009;49:1017–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim JK, Flamm SL, Singh S, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Role of Elastography in the Evaluation of Liver Fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1536–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agbim U, Asrani SK. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis and prognosis: an update on serum and elastography markers. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;13:361–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdel-Aziz G, Lebeau G, Rescan PY, et al. Reversibility of hepatic fibrosis in experimentally induced cholestasis in rat. Am.J.Pathol. 1990;137:1333–1342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popov Y, Sverdlov DY, Bhaskar KR, et al. Macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cholangiocytes contributes to reversal of experimental biliary fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 2010;298:G323–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanless IR, Wong F, Blendis LM, et al. Hepatic and portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: possible role in development of parenchymal extinction and portal hypertension. Hepatology 1995;21:1238–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanless IR, Nakashima E, Sherman M. Regression of human cirrhosis. Morphologic features and the genesis of incomplete septal cirrhosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:1599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts S, Gordon A, McLean C, et al. Effect of sustained viral response on hepatic venous pressure gradient in hepatitis C-related cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:932–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lens S, Alvarado-Tapias E, Marino Z, et al. Effects of All-Oral Anti-Viral Therapy on HVPG and Systemic Hemodynamics in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2017;153:1273–1283 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puche JE, Saiman Y, Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. Compr Physiol 2013;3:1473–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Z, Rockey DC. Upregulation of the actin cytoskeleton via myocardin leads to increased expression of type 1 collagen. Lab Invest 2017;97:1412–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jophlin LL, Koutalos Y, Chen C, et al. Hepatic stellate cells retain retinoid-laden lipid droplets after cellular transdifferentiation into activated myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2018;315:G713–G721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobie R, Wilson-Kanamori JR, Henderson BEP, et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Uncovers Zonation of Function in the Mesenchyme during Liver Fibrosis. Cell Rep 2019;29:1832–1847 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramachandran P, Dobie R, Wilson-Kanamori JR, et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature 2019;575:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Troeger JS, Mederacke I, Gwak GY, et al. Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1073–83 e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kisseleva T, Cong M, Paik Y, et al. Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during regression of liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:9448–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iredale JP. Stellate cell behavior during resolution of liver injury. Seminars in Liver Disease 2001;21:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 2008;134:657–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sohara N, Znoyko I, Levy MT, et al. Reversal of activation of human myofibroblast-like cells by culture on a basement membrane-like substrate. J Hepatol 2002;37:214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deleve LD, Wang X, Guo Y. Sinusoidal endothelial cells prevent rat stellate cell activation and promote reversion to quiescence. Hepatology 2008;48:920–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olsen AL, Bloomer SA, Chan EP, et al. Hepatic stellate cells require a stiff environment for myofibroblastic differentiation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011;301:G110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaca MDA, Georges P, Jammey P, et al. Matrix compliance determines hepatic stellate cell phenotype. Hepatology 2003;38:776A. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakano Y, Kamiya A, Sumiyoshi H, et al. A Deactivation Factor of Fibrogenic Hepatic Stellate Cells Induces Regression of Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Hepatology 2020;71:1437–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Friedman SL. Hepatic fibrosis: A convergent response to liver injury that is reversible. J Hepatol 2020;73:210–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Xu J, Rosenthal S, et al. Identification of Lineage-Specific Transcription Factors That Prevent Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Promote Fibrosis Resolution. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1728–1744 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novo E, Marra F, Zamara E, et al. Overexpression of Bcl-2 by activated human hepatic stellate cells: resistance to apoptosis as a mechanism of progressive hepatic fibrogenesis in humans. Gut 2006;55:1174–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preaux AM, D’Ortho M P, Bralet MP, et al. Apoptosis of human hepatic myofibroblasts promotes activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Hepatology 2002;36:615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy FR, Issa R, Zhou X, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis of activated hepatic stellate cells by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 is mediated via effects on matrix metalloproteinase inhibition: implications for reversibility of liver fibrosis. J Biol Chem 2002;277:11069–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iredale JP, Benyon RC, Arthur MJ, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 messenger RNA expression is enhanced relative to interstitial collagenase messenger RNA in experimental liver injury and fibrosis. Hepatology 1996;24:176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thoen LF, Guimaraes EL, Dolle L, et al. A role for autophagy during hepatic stellate cell activation. J Hepatol 2011;55:1353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernndez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Autophagy fuels tissue fibrogenesis. Autophagy 2012;8:849–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernandez-Gea V, Ghiassi-Nejad Z, Rozenfeld R, et al. Autophagy releases lipid that promotes fibrogenesis by activated hepatic stellate cells in mice and in human tissues. Gastroenterology 2012;142:938–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnabl B, Purbeck CA, Choi YH, et al. Replicative senescence of activated human hepatic stellate cells is accompanied by a pronounced inflammatory but less fibrogenic phenotype. Hepatology 2003;37:653–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong X, Feng D, Wang H, et al. Interleukin-22 induces hepatic stellate cell senescence and restricts liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 2012;56:1150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morello A, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Mesothelin-Targeted CARs: Driving T Cells to Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov 2016;6:133–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amor C, Feucht J, Leibold J, et al. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies. Nature 2020;583:127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karlmark KR, Weiskirchen R, Zimmermann HW, et al. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 2009;50:261–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Vernon MA, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E3186–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iredale JP, Bataller R. Identifying molecular factors that contribute to resolution of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ju C, Tacke F. Hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and liver diseases: from pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Immunol 2016;13:316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiong X, Kuang H, Ansari S, et al. Landscape of Intercellular Crosstalk in Healthy and NASH Liver Revealed by Single-Cell Secretome Gene Analysis. Mol Cell 2019;75:644–660 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rojkind M, Giambrone MA, Biempica L. Collagen types in normal and cirrhotic liver. Gastroenterology 1979;76:710–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villesen IF, Daniels SJ, Leeming DJ, et al. Review article: the signalling and functional role of the extracellular matrix in the development of liver fibrosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;52:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karsdal MA, Manon-Jensen T, Genovese F, et al. Novel insights into the function and dynamics of extracellular matrix in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;308:G807–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iredale JP, Thompson A, Henderson NC. Extracellular matrix degradation in liver fibrosis: Biochemistry and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1832:876–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Birukawa NK, Murase K, Sato Y, et al. Activated hepatic stellate cells are dependent on self-collagen, cleaved by membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase for their growth. J Biol Chem 2014;289:20209–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barry-Hamilton V, Spangler R, Marshall D, et al. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat Med 2010;16:1009–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrison SA, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, et al. Simtuzumab Is Ineffective for Patients With Bridging Fibrosis or Compensated Cirrhosis Caused by Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1140–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suarez-Cuenca JA, Chagoya de Sanchez V, Aranda-Fraustro A, et al. Partial hepatectomy-induced regeneration accelerates reversion of liver fibrosis involving participation of hepatic stellate cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:827–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mizuno S, Nakamura T. Suppressions of chronic glomerular injuries and TGF-beta 1 production by HGF in attenuation of murine diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2004;286:F134–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishikawa T, Bell A, Brooks JM, et al. Resetting the transcription factor network reverses terminal chronic hepatic failure. J Clin Invest 2015;125:1533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ding BS, Cao Z, Lis R, et al. Divergent angiocrine signals from vascular niche balance liver regeneration and fibrosis. Nature 2014;505:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mogler C, Wieland M, Konig C, et al. Hepatic stellate cell-expressed endosialin balances fibrogenesis and hepatocyte proliferation during liver damage. EMBO Mol Med 2015;7:332–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyajima A, Tanaka M, Itoh T. Stem/progenitor cells in liver development, homeostasis, regeneration, and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2014;14:561–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perugorria MJ, Olaizola P, Labiano I, et al. Wnt-beta-catenin signalling in liver development, health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bai L, Liu X, Zheng Q, et al. M2-like macrophages in the fibrotic liver protect mice against lethal insults through conferring apoptosis resistance to hepatocytes. Sci Rep 2017;7:10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van der Heide D, Weiskirchen R, Bansal R. Therapeutic Targeting of Hepatic Macrophages for the Treatment of Liver Diseases. Front Immunol 2019;10:2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kweon YO, Goodman ZD, Dienstag JL, et al. Decreasing fibrogenesis: an immunohistochemical study of paired liver biopsies following lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2001;35:749–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1521–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;52:886–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet 2013;381:468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liaw YF. Reversal of cirrhosis: an achievable goal of hepatitis B antiviral therapy. J Hepatol 2013;59:880–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farci P, Roskams T, Chessa L, et al. Long-term benefit of interferon alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis D: regression of advanced hepatic fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1740–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Powell LW, Kerr JF. Reversal of “cirrhosis” in idiopathic haemochromatosis following long-term intensive venesection therapy. Australas Ann Med 1970;19:54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blumberg RS, Chopra S, Ibrahim R, et al. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma in idiopathic hemochromatosis after reversal of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1988;95:1399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sorensen TI, Orholm M, Bentsen KD, et al. Prospective evaluation of alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver injury in men as predictors of development of cirrhosis. Lancet 1984;2:241–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hammel P, Couvelard A, O’Toole D, et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med 2001;344:418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dufour JF, DeLellis R, Kaplan MM. Reversibility of hepatic fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:981–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berhe N, Myrvang B, Gundersen SG. Reversibility of schistosomal periportal thickening/fibrosis after praziquantel therapy: a twenty-six month follow-up study in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;78:228–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight Loss Through Lifestyle Modification Significantly Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:367–78 e5; quiz e14–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee Y, Doumouras AG, Yu J, et al. Complete Resolution of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1040–1060 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. Journal of hepatology 2006;44:217–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arvaniti V, D’Amico G, Fede G, et al. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1246–56, 1256 e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fede G, D’Amico G, Arvaniti V, et al. Renal failure and cirrhosis: a systematic review of mortality and prognosis. J Hepatol 2012;56:810–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Haj M, Hart M, Rockey DC. Development of a novel clinical staging model for cirrhosis using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]