Abstract

Objective:

To synthesize available evidence about factors associated with patients’ satisfaction after orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery.

Materials and Methods:

Studies that evaluated any factor associated with patients’ satisfaction after the conclusion of an orthodontic treatment combined with an orthognathic surgery were identified. Orthognathic surgical procedures should have been undertaken after completion of craniofacial growth. Any satisfaction psychometric tool was considered. No language limitation was set. A detailed individual search strategy for each of the following bibliographic databases was crafted: MEDLINE, PubMed, EBM Reviews, Web of Science, EMBASE, LILACS, and Scopus. The references cited in the identified articles were also cross-checked, and a partial gray-literature search was undertaken using Google Scholar.

Results:

Eight articles satisfied the inclusion criteria of this systematic review and accounted for 998 patients. The included studies showed large variation in sample size (range = 44 to 505 patients), age (range = 15 to 72 years old), distinct psychological evaluation tools, and time elapsed between the assessment and the completion of surgery and postorthodontic treatment. Most of the studies (five of eight) were classified as having high risk of bias.

Conclusion:

Factors associated with satisfaction were final esthetic outcome, perceived social benefits from the outcome, type of orthognathic surgery, sex, and changes in patient self-concept during treatment. Factors associated with dissatisfaction were treatment length; sensation of functional impairment and/or dysfunction after surgery, and perceived omitted information about surgical risks.

Keywords: Patient satisfaction, Satisfaction, Orthodontic, Orthognathic, Combined orthodontics

INTRODUCTION

In recent years interest in patient satisfaction during health care provision has grown significantly. Therefore, patients’ perceptions and expectations have become increasingly important in justifying health services delivery and ensuring overall health care quality.1

High rates of patient satisfaction after orthognathic surgery have been reported. Patients who completed orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery reported a large variety of psychological benefits, such as improved self-confidence, self-esteem, and/or facial-attractiveness image.2–4 Facial and dentoalveolar changes after orthognathic surgery are believed to contribute to better personal relationships5 and/or employment prognosis.6 In contrast, dissatisfaction can also occur as result of patients’ unachieved expectations. In addition, temporary impairment of oral function, paresthesia, and/or unanticipated short-term facial changes have also been linked to patients’ dissatisfaction after orthognathic surgery.7 Thus, despite the fact that, in many cases, originally stated surgical goals were achieved and therefore success was presumed, clinicians sometimes failed to receive positive feedback from their patients.8 In some cases the reasons behind this apparent lack of perceived success by these patients remains unclear.

Health providers sometimes underestimate patient-reported outcomes.9 This is a potentially significant problem. Full understanding of patients’ views and expectations are paramount to achieve overall success in the provision of health services. Recently, a systematic review addressed the impact of malocclusion on laypersons’ quality of life. The correlation between esthetically compromised malocclusions and their impact on emotional and social dimensions was significant and accompanied by a resulting decrease in quality of life.10 Another systematic review concluded that patients’ quality of life improved after orthognathic surgery.11 No previous attempt at synthesizing the specific factors that affected such outcomes was identified.

Therefore, the aim of the present systematic review was to synthesize available studies that have evaluated factors associated with patients' satisfaction after orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reporting of this systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis - PRISMA checklist.12 This systematic review protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews – PROSPERO (CRD42014014542). Details of the protocol can be accessed at www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014014542.

Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used:

-

—

The study evaluated factors associated with patient satisfaction after the conclusion of an orthodontic treatment combined with an orthognathic surgery.

-

—

Orthognathic surgical procedures were undertaken after completion of craniofacial growth.

-

—

Any satisfaction psychometric tool was considered.

-

—

Neither language nor publication year set as limitations.

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

—

Reviews, letters, case reports, conference papers, and personal opinion publications

-

—

Evaluation of individuals with severe craniofacial syndromes

-

—

Orthognathic surgery related to obstructive sleep apnea therapy

-

—

Treatment involving other major dental specialty work

-

—

Cases that simultaneously underwent minor esthetic/cosmetic surgery (ie, genioplasty, septoplasty)

-

—

Studies that did not assess participants’ expectations after completion of the entire treatment.

Information Sources

A computerized systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE, PubMed, EBM Reviews, Web of Science, EMBASE, LILACS, and Scopus. The references cited in the selected articles were also hand searched for additional relevant studies that could have been missed in the electronic searches. A limited gray-literature search was explored in Google Scholar by restricting the search by the first 100 most relevant hits.

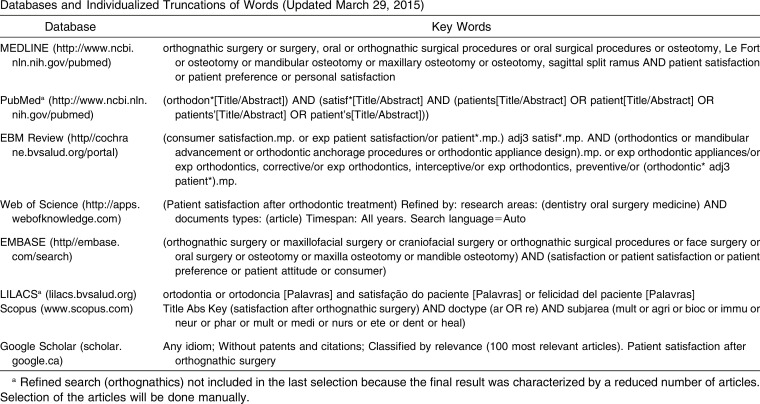

Search Strategy

Details of the key words and word truncation for each database are presented in Appendix 1. All electronic searches were conducted from their earliest records up to September 30, 2014 and updated until March 28, 2015.

Study Selection

Eligibility of the selected articles was determined in two phases. In phase one, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of studies identified in all electronic databases. In phase two, the two reviewers assessed the selected full-text articles applying the same inclusion and exclusion criteria to confirm their final eligibility. The reviewers were not blinded to the authors and the full text of the study. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion until consensus; a third reviewer was involved when this attempt failed to make a final decision.

Data Collection Process and Data Items

Three reviewers were involved in a standardized data extraction process based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review13 template. One reviewer collected the required information from the selected articles. Two reviewers cross-checked all the retrieved information. Again, disagreements were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement between the reviewers. An additional reviewer was involved, when required, to make a final decision.

The data extracted included sample size of selected studies, timing of assessment, methodology, psychological tool elected to assess patients’ satisfaction, orthognathic surgery type, response rate of studies, statistical test, and findings of the included articles. If the reviewers deemed any article to be unclear after full evaluation, they contacted the authors of the study for clarification.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale,14,15 modified for cross-sectional studies,16,17 was applied. This scale addresses three domains (selection, comparability, and outcome), and the selected studies could be awarded one check for each factor in the two first categories (sum of five checks) and two checks for each factor in the comparability domain. The sum of the checks, a maximum of seven, reflects the overall quality rating of the study.

Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias of the selected studies. Disagreements were resolved by attempting to achieve consensus between reviewers. A third reviewer was involved when needed to make a final decision.

Summary Measures and Synthesis of Results

Any quantified/qualified factor that was identified as affecting a patient’s satisfaction after the completion of orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery was accepted.

Risk of Bias Across Studies and Additional Analyses

It was decided a priori that if the data from different studies were sufficiently homogeneous and that the combination of the collected data was justifiable a meta-analysis would be carried out. Additional analysis, such as risk of bias across studies or publication bias, would be calculated only if a meta-analysis was completed.

RESULTS

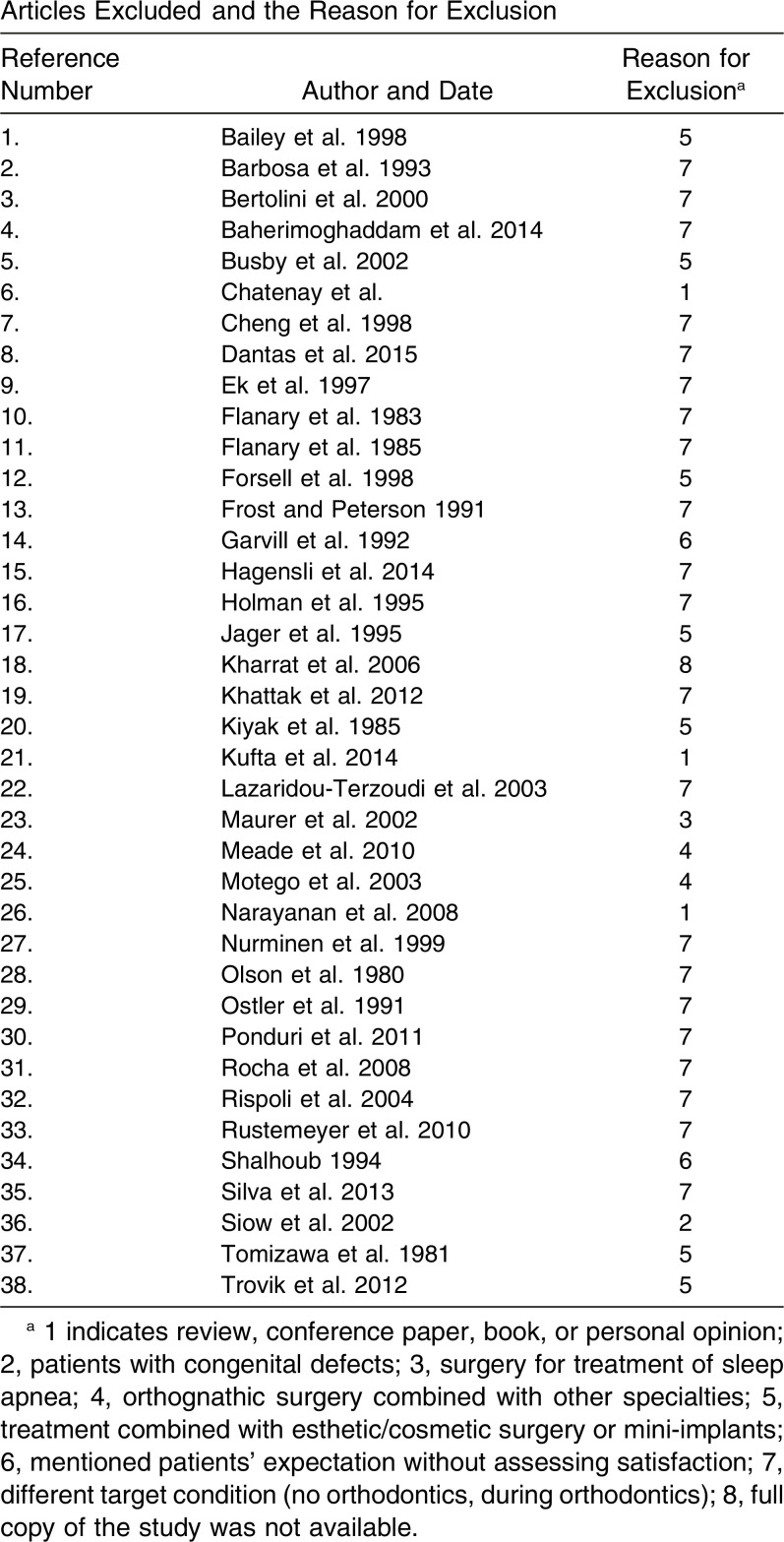

Study Selection

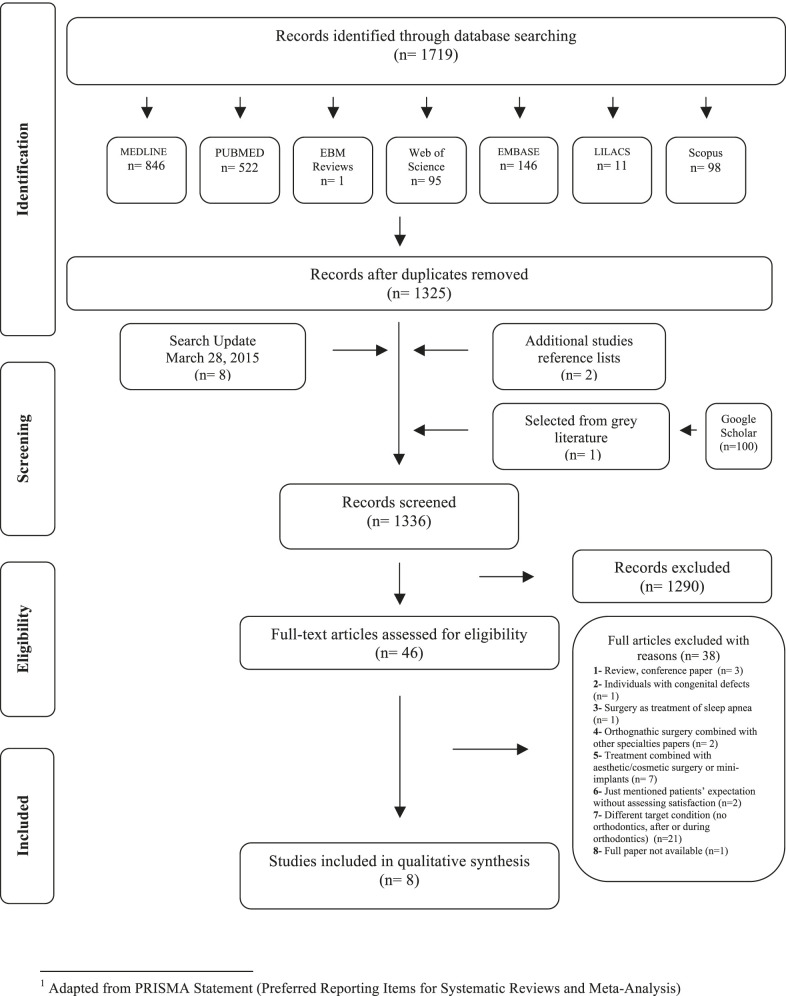

Eight articles satisfied the inclusion criteria of this systematic review. A flow chart of the selection process is outlined in Figure 1. A list of articles excluded during the second selection phase and the reasons for their exclusion is presented in Appendix 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the literature search and selection criteria.

Study Characteristics

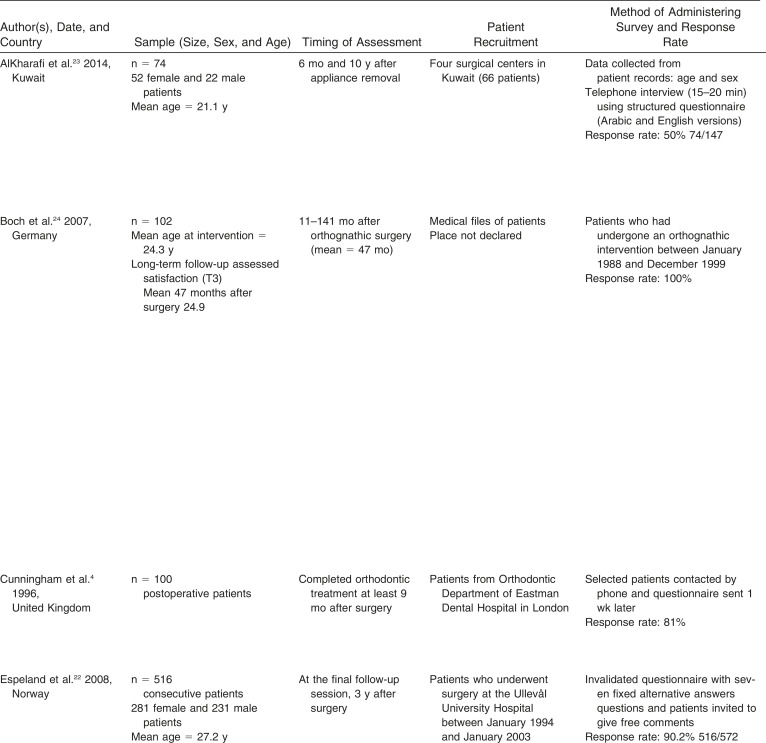

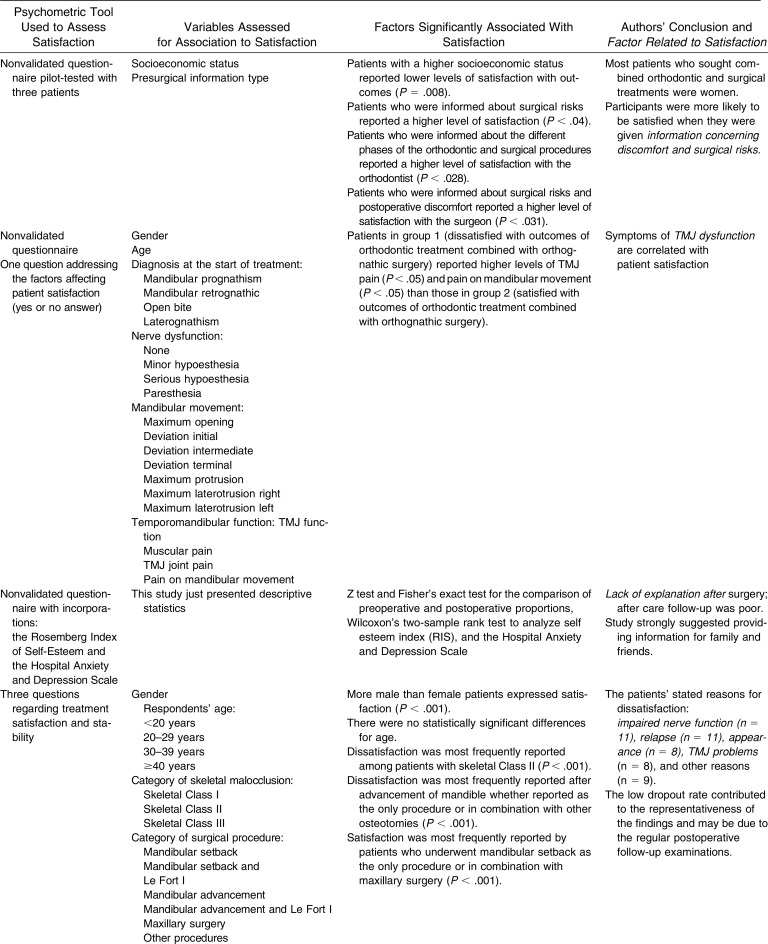

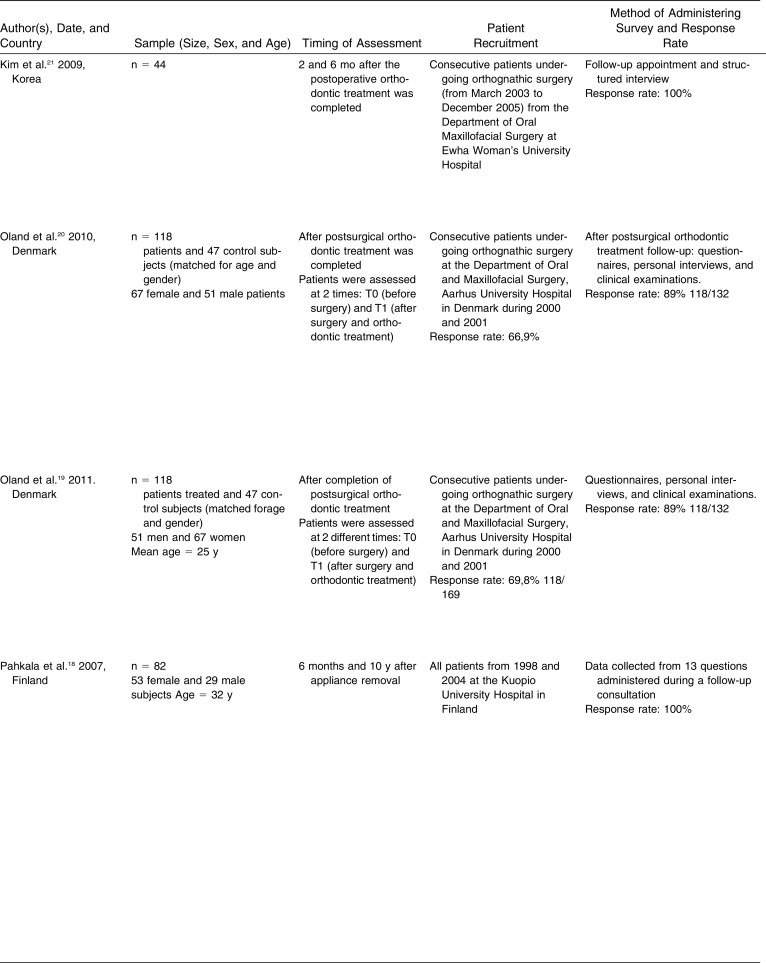

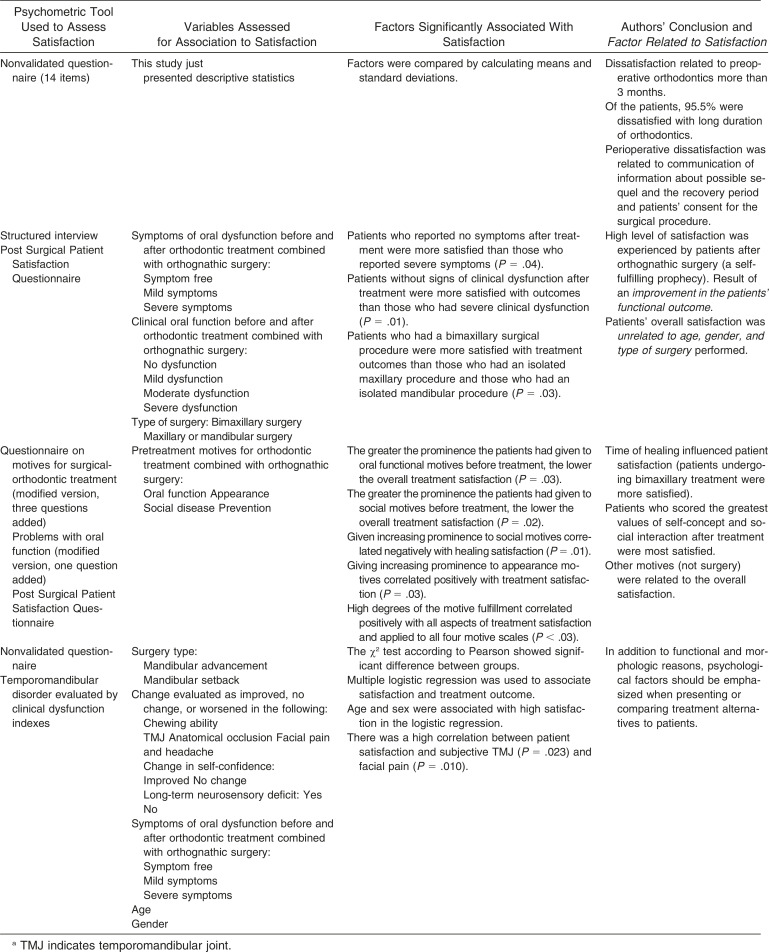

The included studies showed large variation in sample size, age, distinct psychological evaluation tools, and time elapsed between the satisfaction assessment and treatment. Most samples included patients from university hospitals.4,18–22 A summary of the studies’ characteristics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Descriptive Characteristics of the Included Articlesa

Table 1.

Extended

Table 1.

Continued

Table 1.

Extended

Studies applied different tools to assess satisfaction: questionnaires filled out during a follow-up consultation,22–24 questionnaires mailed after treatment,4 structured interview after the follow-up consultation,21 or both questionnaires (interview and questionnaires)19,20 and structured interview by phone.18 Two studies reported that patients were first interviewed by telephone and the satisfaction evaluation was conducted later.4,23

The author of one initially selected study was contacted to clarify missing information by e-mail.25 Because of the provided information, the study was later excluded from the review.

Risk of Bias Within Studies

Most of the studies (five of eight) had high risk of bias. The main risk of bias limitations were related to sample-size calculation and sample power calculation, which were not presented in any of the selected studies. However, some retrospective studies22–24 defined timing and selected consecutive patients, thereby improving the selection methodology. None of the studies indicated use of blinded interviewers or questionnaire/interview evaluators. Finally, half of the studies did not apply previously validated questionnaires or interviews to assess satisfaction after treatment. Specific description and items of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale quality assessment is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Adapted for Cross-Sectional Studiesa

Summary Description of the Individual Studies

Sociodemographic factors

Age was not related directly to satisfaction in four of the papers.18–20,22 Sex22 and socioeconomic status,23 the latter measured as income, were associated with satisfaction. Male patients and patients with a lower socioeconomic status reported higher levels of satisfaction. Schooling was found to be related to the acceptance of undergoing treatment combined with surgery23 but studies did not report whether it influenced satisfaction outcomes.

Treatment outcome

When pretreatment motives to undergo the surgery were addressed, satisfaction levels were better.19 Treatment length was highly negatively correlated with outcome satisfaction.21 Final dentofacial esthetics was strongly positively associated with satisfaction.20,24 Patients dissatisfied with outcomes reported higher levels of temporomandibular joint pain and pain on mandibular movement compared to those who were satisfied with treatment outcomes.24 Patients without a long-term neurosensory deficit after treatment were more satisfied.18 Improvements in temporomandibular joint, facial pain, and anatomical occlusion were significantly associated with patient satisfaction.18 Numbness of lips and jaw and chewing ability after treatment also had a negative effect in overall satisfaction.18,20

Surgery type

Patients who underwent bimaxillary surgery were more satisfied than those who underwent a maxillary or a mandibular procedure only.19,20 Patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion reported dissatisfaction after treatment more frequently than those with skeletal Class I and skeletal Class III malocclusion.22 Patients who underwent mandibular setback as the only procedure18,22 or in combination with maxillary surgery22 had a higher level of satisfaction than those who underwent mandibular advancement as the only procedure18,22 or in combination with maxillary surgery.19,22

Psychological factors

Pretreatment motivation was correlated with posttreatment psychological status and satisfaction. Social interaction increased more after treatment as it was correlated to satisfaction (work and family environments).19,22 In addition, patients indicated that the benefits of combined orthodontic-surgical treatment would have a major influence in their psychological well-being and self-concept.18–20

Quality of care

Patients who were more informed about surgical risks reported a higher level of satisfaction.23 Overall satisfaction was linked to the quantity of information that was given to patients and to their family and direct friends.23 Satisfaction was also linked to quality of care and attention immediately after surgery.4 Lack of information after surgery was suggestive of dissatisfaction.4

Synthesis of Results

Because of the limitations of the identified available evidence, only a list of the factors associated with or without patient’s satisfaction can be presented.

The following factors were associated with satisfaction.

- —

-

—

Perceived social benefits from the outcome22

- —

-

—

Sex (female patients were more likely to link dental appearance and satisfaction with treatment outcome)18,22

- —

The following factors were associated with dissatisfaction:

Risk of Bias Across Studies and Additional Analysis

Included data were not homogeneous enough to justify a meta-analysis.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review investigated factors associated with satisfaction after orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery. In general terms, it is clear that the vast majority of the patients who underwent this combined treatment were satisfied (more than 85%). Patient satisfaction is a multifaceted dimension; however, people may have a complex set of important and relevant beliefs.26 Interest in patient satisfaction with various aspects of their health care has grown significantly for surgeons and orthodontists. The benefits provided by a combined orthodontic-surgical treatment,27 as well as the potential risks and negative side effects regarding this therapy modality,28 can contribute to patients’ satisfaction with the final outcome.

Orthodontists and oral maxillofacial surgeons should improve the informed consent process and properly temper patients’ expectations by limiting false impressions of a “new face” after such complex treatment.8 It has been observed that patients tend to expect their new profile to fit more closely to socially accepted patterns than what should really be expected.29

Another major factor to be considered is that the perceived care and attention the orthodontist, surgeon, and staff provided to the patient increased the patient’s confidence in the orthodontic/surgical treatment outcomes. However, perception of care is a broad category that was sometimes only assessed as quality of care in the studies examined. These distinct concepts need to be properly differentiated.26 Results suggest that health care shortly after surgery promotes satisfaction not just for the patients but also for family and friends.

Although common sense dictates that genioplasties and related minor surgical procedures further improve esthetic outcomes, this systematic review did not consider these factors so that it was clear that the results were based only on the major surgical procedures and not on these minor auxiliary esthetic procedures. By doing so the effects of the most significant part of the surgical procedure are clearly differentiated.30–32

It has to be noted that more than 85% of the assessed patients were satisfied with the results. This high satisfaction level has been previously shown in a review related to orthognathic interventions and improvement in quality of life11 as well as in other related studies.2,32 Still, 15% of patients were not fully satisfied. This is where the suggestions from the systematic review can be used to prevent these dissatisfaction levels. It has to be noted that patients who undergo some types of orthognathic surgical procedures (ie, mandibular setbacks) are more likely to be satisfied with the final outcome. These types of surgical procedures are usually closely linked to specific malocclusions (in this example Class III malocclusion with mandibular excess).

Patients’ motivation to seek combined orthodontic-surgical treatment depends on subjective factors. The perceived social benefits of the treatment outcomes were correlated with satisfaction33 and reported to be one of the significant motivations to accept the orthodontic-surgical treatment plan.34 Patients who reported improvements in self-confidence and higher levels of self-concept and social interaction after treatment showed higher levels of satisfaction with outcomes.18 Accordingly, a recent study presented strong evidence of the impact of a malocclusion and its negative influence on emotional and social dimensions.10

Limitations

A clear limitation of this study is related to the different timing of the satisfaction assessment as the time frame could influence perception of satisfaction. Memory bias should be considered when assessing patients within a 9-year interval after treatment completion.24 Also, the interpretation of results could differ when the results derive from face-to-face interview, mailed questionnaire or structured interview by phone. Two studies4,21 only presented descriptive statistics, which hampers comparison with statistically significant results.

There is need to develop surgical outcomes questionnaires with confirmed standard psychometric properties, such as validity and reliability.35

CONCLUSION

Although a number of factors were identified that were associated with patients’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery; the available evidence was limited. Listed factors should therefore be considered cautiously.

APPENDIX 1

Databases and Individualized Truncations of Words (Updated March 29, 2015)

APPENDIX 2

Articles Excluded and the Reason for Exclusion

APPENDIX 2

REFERENCES

Bailey LJ, Duong HL, Proffit WR. Surgical Class III treatment: long-term stability and patient perceptions of treatment outcome. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:35–44.

Barbosa AL, Marcantonio E, Barbosa CE, Gabrielli MF, Gabrielli MA. Psychological evaluation of patients scheduled for orthognathic surgery. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1993;35:1–9.

Bertolini F, Russo V, Sansebastiano G. Pre- and postsurgical psycho-emotional aspects of the orthognathic surgery patient. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2000;15:16–23.

Baherimoghaddam T, Oshagh M, Naseri N, Nasrbadi NI, Torkan S. Changes in cephalometric variables after orthognathic surgery and their relationship to patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2014;5(4):e6.

Busby BR, Bailey LJ, Proffit WR, Phillips C, White RP Jr. Long-term stability of surgical Class III treatment: A study of 5-year postsurgical results. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002;17:159–170.

Chatenay C, Leblanc M, Thomas H. The therapeutic smile: orthodontics, surgery and mental attitude. Orthod Fr. 1991;62:573–582.

Cheng LH, Roles D, Telfer MR. Orthognathic surgery: the patients’ perspective. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:261–263.

Dantas JFC, Neto JNN, de Carvalho SHG, de B Martins LMCL, de Souza RF, Sarmento VA. Satisfaction of skeletal class III patients treated with different types of orthognathic surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:195–202.

Ek E, Persson J, Lundgren S. Surgical correction of dentofacial anomalies: an evaluation of two patient groups with the aid of a questionnaire. Swed Dent J. 1997;21:101–110.

Flanary CM, Alexander JM. Patient responses to the orthognathic surgical experience: factors leading to dissatisfaction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:770–774.

Flanary CM, Barnwell GM Jr, Alexander JM. 1985, Patient perceptions of orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod. 1985;88:137–145.

Forssell H, Finne K, Forssell K, Panula K, Blinnikka LM. Expectations and perceptions regarding treatment: a prospective study of patients undergoing orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:107–113.

Frost V, Peterson G. Psychological aspects of orthognathic surgery: how people respond to facial change. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:538–542.

Garvill J, Garvill H, Kahnberg KE, Lundgren S. Psychological factors in orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1992;20:28–33.

Hagensli N, Stenvik A, Espeland L. 2014. Asymmetric mandibular prognathism: outcome, stability and patient satisfaction after BSSO surgery. A retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:1735–1741.

Holman AR, Brumer S, Ware WH, Pasta DJ. The impact of interpersonal support on patient satisfaction with orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:1289–1297.

Jager A, Flechsig G, Luhr HG. The motivation and experiences of patients in connection with orthodontic-oral surgery combined therapy. A patient survey with consideration of the clinical and psychosocial factors. Fortschr Kieferorthop. 1995;56:265–273.

Kharrat K, Assante M, Chossegros C, et al. Patient perception of functional and cosmetic outcome of orthognathic surgery. Retrospective analysis of 45 patients. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 2006;107:9–14; discussion 15–16.

Khattak ZG, Benington PC, Khambay BS, Green L, Walker F, Ayoub AF. An assessment of the quality of care provided to orthognathic surgery patients through a multidisciplinary clinic. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:243–247.

Kiyak HA, McNeill RW, West RA. The emotional impact of orthognathic surgery and conventional orthodontics, Am J Orthod. 1985;88:224–234.

Kufta K, Peacock ZS, Chuang SK, Levin LM. Retrospective assessment of patient satisfaction after orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(suppl):e130–e131.

Lazaridou-Terzoudi T, Kiyak HA, Moore R, Athanasiou AE, Melsen B. Long-term assessment of psychologic outcomes of orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61: 545–552.

Maurer P, Otto C, Bock JJ, Eckert AW, Schubert J. Patient satisfaction with the outcome of surgical orthodontic intervention and effect of esthetic and functional criteria. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2002; 6:15–18.

Meade EA, Inglehart MR. Young patients’ treatment motivation and satisfaction with orthognathic surgery outcomes: the role of “possible selves.” Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:26–34.

Motegi E, Hatch JP, Rugh JD, Yamaguchi H. 2003, Health-related quality of life and psychosocial function 5 years after orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:138–143.

Narayanan V, Guhan S, Sreekumar K, Ramadorai A. Self-assessment of facial form oral function and psychosocial function before and after orthognathic surgery: a retrospective study. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:12–16.

Nurminen L, Pietila T, Vinkka-Puhakka H. 1999, Motivation for and satisfaction with orthodontic-surgical treatment: a retrospective study of 28 patients. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:79–87.

Olson RE, Laskin DM. Expectations of patients from orthognathic surgery. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:283–285.

Ostler S, Kiyak HA. Treatment expectations versus outcomes among orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1991;6:247–255.

Pondur S, Pringle A, Illing H, Brennan PA. 2011, Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) index outcomes for orthodontic and orthognathic surgery patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49:217–220.

Roch NS, Cavalcante JR, de Oliveira e Silva ED, Caubi AF, Laureano Filho JR, Gondim DG. Patient’s perception of improvement after surgical assisted maxillary expansion (SAME): pilot study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E783–E787.

Rispoli A, Acocella A, Pavone I, et al. Psychoemotional assessment changes in patients treated with orthognathic surgery: pre- and postsurgery report. World J Orthod. 2004;5:48–53.

Rustemeyer J, Eke Z, Bremerich A. Perception of improvement after orthognathic surgery: the important variables affecting patient satisfaction. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;14:155–162.

Shalhoub SY. Scope of oral and maxillofacial surgery: the psychosocial dimensions of orthognathic surgery. Aust Dent J. 1994;39:181–183.

Silva ACA, Carvalho RAS, Santos TS, Rocha NS, Gomes ACA, Silva EDO. Evaluation of life quality of patients submitted to orthognathic surgery. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013;18(5):107–114.

Siow KK, Ong ST, Lian CB, Ngeow WC. Satisfaction of orthognathic surgical patients in a Malaysian population. J Oral Sci. 2002;44:165–171.

Tomizawa M, Nakajima T, Ueda K, Azumi T, Hanad K. Evaluation by patients of surgical orthodontic correction of skeletal Class III malocclusion: survey of 41 patients. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:590–596.

Trovik TA, Wisth PJ, Tornes K, Boe OE, Moen K. Patients’ perceptions of improvements after bilateral sagittal split osteotomy advancement surgery: 10 to 14 years of follow-up. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:204–212.

REFERENCES

- 1.Njio BJ, ter Heege GJ, Prahl-Andersen B. Quality development in a dental practice environment. A web-based system for measuring patient satisfaction. J Orofac Orthop. 2008;69:448–462. doi: 10.1007/s00056-008-0654-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazaridou-Terzoudi T, Kiyak HA, Moore R, Athanasiou AE, Melsen B. Long-term assessment of psychologic outcomes of orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:545–552. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham SJ, Crean SJ, Hunt NP, Harris M. Preparation, perceptions, and problems: a long-term follow-up study of orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1996;11:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP, Feinmann C. Perceptions of outcome following orthognathic surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34:210–213. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(96)90271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt OT, Johnston CD, Hepper PG, Burden DJ. The psychosocial impact of orthognathic surgery: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:490–497. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.118402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pithon MM, Nascimento CC, Barbosa GC, Coqueiro Rda S. Do dental esthetics have any influence on finding a job? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey LJ, Duong HL, Proffit WR. Surgical Class III treatment: long-term stability and patient perceptions of treatment outcome. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertolini F, Russo V, Sansebastiano G. Pre- and postsurgical psycho-emotional aspects of the orthognathic surgery patient. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2000;15:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waljee J, McGlinn EP, Sears ED, Chung KC. Patient expectations and patient-reported outcomes in surgery: a systematic review. Surgery. 2014;155:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimberg L, Arnrup K, Bondemark L. The impact of malocclusion on the quality of life among children and adolescents: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Eur J Orthod. 2015;37:238–247. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soh CL, Narayanan V. Quality of life assessment in patients with dentofacial deformity undergoing orthognathic surgery—a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42:974–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cochrane, Communication CCa, Group R. Data Extraction Template. 2013 Available at: https://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources Accessed May 13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benedek P, Lazar Z, Bikov A, Kunos L, Katona G, Horvath I. Exhaled biomarker pattern is altered in children with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:1244–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2013. The Newcastle-Ottawa score for non-randomized studies. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed December 05. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breton MC, Guenette L, Amiche MA, Kayibanda JF, Gregoire JP, Moisan J. Burden of diabetes on the ability to work: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:740–749. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pachêco-Pereira CPJ, Perez A, Dick BD, Flores-Mir C. Factors associated with patient’s and parent’s satisfaction after orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. In press doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pahkala RH, Kellokoski JK. Surgical-orthodontic treatment and patients’ functional and psychosocial well-being. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oland J, Jensen J, Elklit A, Melsen B. Motives for surgical-orthodontic treatment and effect of treatment on psychosocial well-being and satisfaction: a prospective study of 118 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.06.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oland J, Jensen J, Melsen B. Factors of importance for the functional outcome in orthognathic surgery patients: a prospective study of 118 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(9):2221–2231. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Shin SW, Han I, Joe SH, Kim MR, Kwon JJ. Clinical review of factors leading to perioperative dissatisfaction related to orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2217–2221. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espeland L, Hogevold HE, Stenvik A. A 3-year patient-centred follow-up of 516 consecutively treated orthognathic surgery patients. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:24–30. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AlKharafi L, AlHajery D, Andersson L. Orthognathic surgery: pretreatment information and patient satisfaction. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:218–224. doi: 10.1159/000360735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bock JJ, Maurer P, Fuhrmann RA. The importance of temporomandibular function for patient satisfaction following orthognathic surgery. J Orofac Orthop. 2007;68:299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00056-007-0424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocha NS, Cavalcante JR, de Oliveira e Silva ED, Caubi AF, Laureano Filho JR, Gondim DG. Patient’s perception of improvement after surgical assisted maxillary expansion (SAME): pilot study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E783–E787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng LH, Roles D, Telfer MR. Orthognathic surgery: the patients’ perspective. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:261–263. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90709-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flanary CM, Alexander JM. Patient responses to the orthognathic surgical experience: factors leading to dissatisfaction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:770–774. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(83)80042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoppenreijs TJ, Hakman EC, van’t Hof MA, Stoelinga PJ, Tuinzing DB, Freihofer HP. Psychologic implications of surgical-orthodontic treatment in patients with anterior open bite. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1999;14:101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rustemeyer J, Gregersen J. Quality of life in orthognathic surgery patients: post-surgical improvements in aesthetics and self-confidence. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meade EA, Inglehart MR. Young patients’ treatment motivation and satisfaction with orthognathic surgery outcomes: the role of “possible selves.”. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finlay PM, Atkinson JM, Moos KF. Orthognathic surgery: patient expectations; psychological profile and satisfaction with outcome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(95)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiyak HA, Hohl T, West RA, McNeill RW. Psychologic changes in orthognathic surgery patients: a 24-month follow up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:506–512. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forssell H, Finne K, Forssell K, Panula K, Blinnikka LM. Expectations and perceptions regarding treatment: a prospective study of patients undergoing orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Travess HC, Newton JT, Sandy JR, Williams AC. The development of a patient-centered measure of the process and outcome of combined orthodontic and orthognathic treatment. J Orthod. 2004;31:220–234. doi: 10.1179/146531204225022434. discussion 201–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]