Abstract

Background

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) from antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces treatment benefits and leads to treatment failure. Hence, this study was aimed at determining the incidence of loss to follow-up and predictors among HIV-infected adults who began first-line antiretroviral therapy at Arba Minch General Hospital.

Methods

We carried out an institutional-based retrospective cohort study, and data were collected from the charts of 508 patients who were selected using a simple random sampling technique. All the data management and statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14. Cumulative survival probability was estimated and presented in the life table, and the Kaplan-Meir survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify the independent predictors.

Results

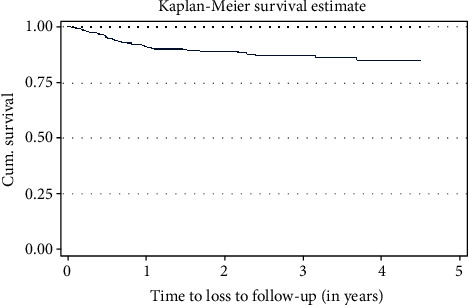

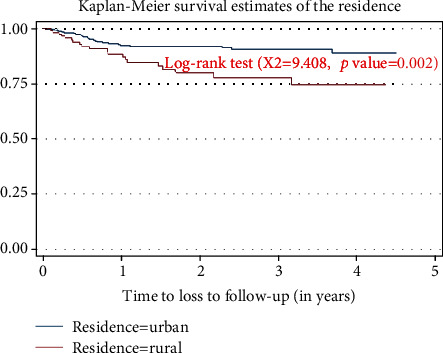

We followed 508 patients for 871.9 person-years. A total of 46 (9.1%) experienced loss to follow-up, yielding an overall incidence rate of 5.3 (95% CI: 3.9-7.1) per 100 person-years. The cumulative survival probability was 90%, 88%, 86%, and 86% at the end of one, two, three, and four years, respectively. The predictors identified were age less than 35 years (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR = 1.96; 95% CI: 1.92-4.00)), rural residence (aHR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.02-3.83), baseline body weight greater than 60 kilograms (aHR = 2.19; 95% CI: 1.11-4.37), a fair level of adherence (aHR = 11.5; 95% CI: 2.10-61.10), and a poor level of adherence (aHR = 12.03; 95% CI: 5.4-26.7).

Conclusions

In this study, the incidence rate of loss to follow-up was low. Younger adults below the age of 35 years, living in rural areas, with a baseline weight greater than 60 kilograms, which had a fair and poor adherence level were more likely to be lost from treatment. Therefore, health professionals working in ART clinics and potential stakeholders in HIV/AIDS care and treatment should consider adult patients with these characteristics to prevent LTFU.

1. Background

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the major global public health problem that affected an estimated 36.9 million people with a global adult prevalence of 0.8% in 2018 [1]. An estimated 66% of the global burden was in sub-Saharan Africa, and of these, 19.6 million were living in East Africa [1].

In Ethiopia, the gradual decline in new HIV infections in adults was reported by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) HIV-related estimates and projections from 13,394 for the year 2016 to 11,613 in 2019 [2]. A total of 21.7 million people living with HIV (PLWHIV) were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), globally [1]. According to EPHI, in urban Ethiopia, 98.6% of adults are using ART from 2017 to 2018 [3].

Effective ART utilization controls and prevents the transmission of HIV and increases the life expectancy of HIV-infected individuals by reducing the mortality rate secondary to HIV [4]. ART had a significant contribution to the fall in new HIV infections by 37% and deaths related with AIDS by 45%, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2018 and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2019 global HIV/AIDS epidemic report [5, 6]. And also, people on ART achieving 90% sustained viral suppression were targeted according to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) [7]. But, loss to follow-up (LTFU) is a great challenge in achieving this target [8], and also, it was highly associated with early death [9].

In ART service utilization, loss to follow-up (LTFU) refers to a patient who had no contact for three consecutive months or longer after the last appointment for antiretroviral (ARV) refills [10]. Despite the efforts to reduce the rate of LTFU among HIV patients who are put on ART follow-up, it continued to be a challenge in HIV/AIDS care with an incidence rate ranging from 6.48 per 1000 person-months to 26.7 per person-years [11, 12].

According to the reports of different studies, the magnitude of LTF among patients living with HIV was estimated to be high. The report of the systematic review in sub-Saharan Africa showed an estimated LTFU from 20% to 40% [13], 4.1% in Asia, 21.8% in western Africa [14], 26.7 per 100 person-years in Uganda [12], and 23.9% in Nigeria [15]. In Ethiopia, a country in Eastern Africa, the incidence of LTFU varies from 0.05 per 100 person-years to 10.9 per 100 person-years across different settings [11, 16–23].

Loss of follow-up from ART service has a great negative impact on HIV patients. It can negatively affect the immunological benefits of ART and increase AIDS-related morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization, and it also results in serious consequences such as drug toxicity, treatment failure due to poor adherence, and drug resistance. It also poses a serious challenge to program implementers and constitutes an inefficient use of scarce resources like treatment [24–28]. Besides, loss to follow-up affects the performance of the 90–90–90 target that aims at achieving 90% of virally suppressed patients on ART and this is since an interference to ART follow-up lowers the success of the treatment of ART and thus leads to a decrease in the number of CD4 cell counts and increases the number of viral counts [29].

Different studies revealed that LTFU from the ART service is associated with baseline sociodemographic factors and clinical and treatment-related factors. From the sociodemographic variables: young age [16, 21, 30], male sex [18, 19, 31–33], high educational status [30, 34], single marital status [10, 35, 36], self-employed-occupational status [28, 33], rural residence [22, 33], not disclosing their status to any one [19, 34], distance from health facility over 5 kilometers [10, 11], not having a primary caregiver [11, 37], were reported predictors. Furthermore, clinical-, treatment-, and behavioral-related factors like baseline CD4 count < 200 cells/μL [18, 20, 33], WHO clinical stages III and IV [21, 22, 33], taking AZT-3TC-NVP ART regimen at the start [16, 38], having an opportunistic infection at enrolment [18, 20, 39], bed-ridden and ambulatory baseline functional status [18, 20, 40], not receiving cotrimoxazole and isoniazid preventive therapy at the start [16, 20], low body mass index (BMI) (<18.5 kg/m2) [20], high viral loads [17], suboptimal (fair/poor) adherence level [20, 33], substance use [20], next appointment not recorded [19], and having a cell phone [22] were reported predictors. However, these factors vary from place to place in HIV patients [20].

Though few studies were done in Ethiopia, the incidence rate of loss to follow-up and predictors has not been investigated in this study setting. Therefore, this study assessed the level of incidence of loss to follow-up and its predictors among adult HIV patients on ART in Arba Minch General Hospital. The results of this study will provide necessary inputs for policymakers and program planners who are working at different levels of HIV/AIDS control programs. Besides, early identification of the problem is important to know the vital intervention areas and improve the lives of people living with HIV (PLHIV) through improved viral suppression. In resource-limited settings like Ethiopia, evidence-based interventions that prevent the loss to follow-up will improve treatment outcomes and adherence in a cost-effective approach.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted an institutional-based retrospective cohort study in Arba Minch General Hospital. Arba Minch town, the capital of the Gamo zone, is located in Southern Ethiopia about 444 kilometers away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Arba Minch General Hospital provides free diagnosis, treatment and monitoring, and follow-up for HIV patients, and nowadays, 1,699 adult HIV patients are actively following AR. This study included those enrolled from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018. Treatment and follow-up were based on the national FMOH ART treatment guidelines for HIV infections in adults and adolescents [41].

2.2. Population

All HIV-infected adults, aged 15 years and above, who were registered for HIV/AIDS care and put on ART from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018, in the Arba Minch General Hospital ART clinic, were the study population. Patients who initiated ART, but without at least one ART follow-up visit, with an incomplete patient record and those who transferred in from another facility were excluded from the study.

2.3. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

The sample size was calculated by using STATA version 14 based on the following assumptions: 5% alpha, 80% power, allocation ratio 1, and adjusted hazard ratio 1.3 for CD4 count < 200 cells/μL from the previous study conducted in Gondar, Northern Ethiopia, [18], and by adding 10%, the final sample size was five hundred eight. These samples were reached by a simple random sampling technique specifically by a computer-generated random number method. The medical registration number of patients obtained from the hospital electronic database was used as a sampling frame after excluding 106 patients who fulfill exclusion criteria.

2.4. Study Variables

In this study, the dependent variable was the LTFU from ART service utilization, whereas sociodemographic factors such as sex, age, education level, marital status, occupation status, residence, disclosure status (disclosed HIV status to their partner, family, or other relatives/not), substance use; treatment-related factors such as eligibility criterion (test–start/not), initial ART regimen type, comedication, treatment duration, drug side effects, number of pills per day, cotrimoxazole prophylactic treatment (CPT) at the start of ART, and the level of adherence; and clinical and immunological-related factors like baseline body weight, WHO clinical stage, CD4 count, opportunistic infections (OIs) at the start of an initial regimen, comorbidity other than OIs, baseline ALS, HGB, creatinine, and functional status were considered as the independent variable.

2.5. Operational Definitions

This study considered LTFU when a patient is not seen at the ART clinic for at least 90 days or 3 months after the last missed appointment, but not transferred out from the facility to another facility or dead [19, 20, 42–44]. The time to LTFU was the time interval between the dates of ART initiation and the last missed appointment, and censored are patients who died while on treatment, changed the first-line regimen, or completed the follow-up period without developing the event (LTFU) [19, 20, 42]. The following ratings to patient adherence to ART were made by the attending physician or nurse: good (95% of pills were taken: missed only 1 dose out of 30 or 2 doses out of 60), fair (85–94% of pills were taken: missed 2–4 doses out of 30 or 4–9 doses per 60), and poor (less than 85%: missed more than 5 doses out of 30 or greater than 10 doses out of 60) [20, 42]. The functional status of participants was assessed and labelled as working when an individual was able to the perform usual work inside or outside the home, ambulatory when able to perform only the activities of daily living (ADL), and not able to work or bedridden when not able to perform ADL [20]. In this study, also substance abuse was measured as any history of harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances, including alcohol and illicit drugs [20]. A card was considered incomplete when the indicator of the dependent variable and/or 20% of the independent variables were not registered in the chart [45].

2.6. Data Collection Tool and Procedures

The data collection tool was prepared by reviewing various kinds of literature in the English version that included sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, treatment-related characteristics, and the information related to the time of ART initiation and end date of LTFU and censored. The data were collected by three BSC nurses who had previous exposure to data collection and training on comprehensive HIV care and supervised by two master's holders in public health who had experience in data management.

2.7. Data Quality Assurance

To assure the quality of data, the data extraction format was designed carefully and we appropriately recruited data collectors who had experience in data collection. And also, training was given for data collectors and supervisors. A pretest was performed on 5% of the populations before data collection in the same setting in Arba Minch General Hospital because the source of data was secondary. Intensive supervision was done on a daily basis by the principal investigator and supervisors during the whole period of data collection.

The principal investigator reviewed a random sample of registration forms to confirm the reliability of data before the data collection period, and the investigator and supervisors made random crosschecking for the completeness, accuracy, and consistency of data at the end of each day, and accordingly, corrective discussion was made with all data collectors. To minimize errors and take corrective actions, remarks were given during morning times. Then, the data were checked for completeness and consistency and coded and entered into the computer using EpiData version 4.6.

2.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data were cleaned, edited, coded, and entered into EpiData version 4.6 and exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. Exploratory data analysis was carried out to check the missing values. Results are presented using numerical summary measures, frequency, and percentages and also using survival curves and tables. The incidence rate of loss to follow-up was calculated by dividing the numbers who experienced the loss to follow-up in the overall follow-up period by person-time at risk contributed throughout the observation period. A life table was used to estimate the cumulative survival time in each time interval. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve together with the log-rank test was used to estimate the median time and to compare the overall survival experience of two or more categories of variables.

A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to identify the factors that predicted LTFU. Bivariable Cox regression analysis was used to identify candidate variables in the multivariable Cox regression. Those variables with p ≤ 0.25 levels in the bivariable analysis which had improved model adequacy compared with the null model were entered into the multivariable Cox regression analysis. Model adequacy was checked via the maximum likelihood with the assumption of the higher is the better. The backward variable selection method was applied to get significantly associated predictors, and the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) and the p value were used to assess the strength of association and statistical significance, respectively. The statistical significance was considered at a p value < 0.05. The reasonability of proportional hazard assumptions was tested graphically and by using the Schoenfeld residuals test (phtest) by using a post estimation command “estat phtest” and “estat phtest, detail” for the final model and each variable, respectively. In the final model, the global test of the Schoenfeld residuals test gave χ2(df) = 13.15 with a p value = 0.4361; this supports the null hypothesis which states that hazards are proportional and the iteration of log-likelihood was −266.084 in the first step and −228.4955 in the last iteration of log-likelihood with LR x2 = 75.18 and a p value < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 508 charts of HIV patients were reviewed and analyzed, giving a 100% response rate. The mean age at initiation of ART ± SD (standard deviation) was 35.1 ± 8.2 years. A majority, 219 (43.1%), were in the age groups between 25 and 34 years. A total of 289 (56.9%) were females. Regarding the educational status of the patients, a majority, 195 (38.4%), completed the primary education level and about 63 (12.4%) had tertiary and above educational statuses. A total of 375 (73.8%) were urban dwellers but the rest were rural dwellers. A total of 485 (95.5%) disclosed their HIV status to either their family or other relatives, but the rest did not disclose their HIV status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of HIV-positive adults at the initiation of ART at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15–24 | 31 | 6.1 |

| 25–34 | 219 | 43.1 | |

| 35–44 | 183 | 36.0 | |

| ≥45 | 75 | 14.8 | |

| Sex | Female | 289 | 56.9 |

| Male | 219 | 43.1 | |

| Marital status | Married | 298 | 58.7 |

| Divorced | 90 | 17.7 | |

| Single | 67 | 13.2 | |

| Widowed | 53 | 10.4 | |

| Educational status | Primary | 195 | 38.4 |

| Secondary | 138 | 27.2 | |

| Not educated | 112 | 22.1 | |

| Tertiary and above | 63 | 12.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 308 | 60.6 |

| Protestant | 173 | 34.1 | |

| Muslim | 20 | 3.9 | |

| Others∗ | 7 | 1.4 | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 378 | 74.4 |

| Employed | 130 | 25.6 | |

| Residence | Urban | 375 | 73.8 |

| Rural | 133 | 26.2 | |

| Substance use | Yes | 76 | 14.9 |

| No | 32 | 85.1 | |

| Disclosure status | Disclosed | 485 | 95.5 |

| Not disclosed | 23 | 4.5 |

∗ = Catholic religion followers, Traditional believers.

3.2. Baseline Clinical-, Immunological-, and Treatment-Related Characteristics

A total of 238 (46.9%) patients started ART by test and start eligibility criteria, but 270 (53.1%) were not by test and start. Initially, a majority, 498 (98.1%), of HIV patients have prescribed a combination of tenofovir (TDF) + lamivudine(3TC) + efavirenz (EFV), followed by tenofovir (TDF) + lamivudine(3TC) + nevirapine (NVP), zidovudine (AZT) + lamivudine(3TC) + efavirenz (EFV), and zidovudine (AZT) + lamivudine(3TC) + nevirapine (NVP). A majority of patients, 491 (96.7%), started by taking one ART pill per day whereas the rest started by taking more than one ART pill and 284 (55.9%) of the patients took CPT prophylaxis at the start of ART (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline clinical-, immunological-, and treatment-related characteristics of HIV-positive adults on ART in Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial regimen | TDF + 3TC + EFV | 498 | 98.0 |

| AZT + 3TC + EFV | 3 | 0.6 | |

| AZT + 3TC + NVP | 4 | 0.8 | |

| TDF + 3TC + NVP | 3 | 0.6 | |

| ART pills per a day | One | 491 | 96.7 |

| Two | 17 | 3.4 | |

| CPT at start of ART | Yes | 284 | 55.9 |

| No | 224 | 44.1 | |

| Comedication other than CPT | Yes | 111 | 21.9 |

| No | 397 | 78.2 | |

| TB at start | Yes | 84 | 16.5 |

| No | 424 | 83.5 | |

| OIs other than TB at the start | Yes | 85 | 16.7 |

| No | 423 | 83.3 | |

| Comorbidity other than OIs | Yes | 11 | 2.2 |

| No | 497 | 97.8 | |

| Functional status | Working | 395 | 77.8 |

| Ambulatory and bedridden | 113 | 22.2 | |

| WHO clinical stage | Stage I | 271 | 53.4 |

| Stage II | 97 | 19.1 | |

| Stage III | 124 | 24.4 | |

| Stage IV | 16 | 3.2 | |

| Baseline weight (in kg) | ≤60 kg | 384 | 75.6 |

| >60 kg | 124 | 24.4 | |

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/mm3) | <100 cells/mm3 | 88 | 17.3 |

| 100–199 cells/mm3 | 89 | 17.5 | |

| 200–349 cells/mm3 | 155 | 30.5 | |

| ≥350 cells/mm3 | 176 | 34.7 | |

| Baseline HGB (g/dL) | <7 g/dL | 10 | 2.4 |

| 7–9.9 g/dL | 60 | 11.8 | |

| 10–12.9 g/dL | 306 | 60.2 | |

| ≥13 g/dL | 132 | 25.9 | |

| Baseline creatinine | 0.00–0.59 mg/dL | 93 | 18.3 |

| 0.6–1.2 mg/dL | 379 | 74.6 | |

| >1.2 mg/dL | 36 | 7.1 | |

| Baseline alanine transaminase (IU/L) | <7 IU/L | 9 | 1.8 |

| 7–56 IU/L | 472 | 92.9 | |

| >56 IU/L | 27 | 5.31 | |

| Drug side effect | Yes | 157 | 30.9 |

| No | 351 | 69.1 | |

| Treatment duration | <1 year | 198 | 38.9 |

| 1–2 years | 109 | 21.5 | |

| >2 years | 201 | 39.6 |

ART: antiretroviral therapy; AZT: zidovudine; CD4: clusters of differentiation; CPT: cotrimoxazole prophylaxis therapy; EFV: efavirenz; HGB: hemoglobin; IU/L: international unit per liters; kg: kilogram; TDF: tenofovir; +3TC: lamivudine; NVP: nevirapine; TB: tuberculosis; OIs: opportunistic infections; WHO: World Health Organization.

Of all study participants, a majority, 271 (53.4%), were in WHO clinical stage I at the initiation of ART and 395 (77.8%) of the participants were on a working functional status at baseline. The median weights of the study participants at the initiation of ART and at the end of the follow-up period were 55.0 kg (interquartile range (IQR): 48–60) and 57.6 kg (IQR: 52–60), respectively. The median CD4 count at initiation of ART was 281.5 cell/mm3 (IQR: 144.5–407.0) and it was 457.3 cell/mm3 (IQR: 400–485.8) at the end of the follow-up period, and above half, 306 (60.2%), of study subjects started ART at a HGB level of between 10 and 12.9 g/dL. A total of 84 (16.5%) of the study participants have been diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) at the initiation of ART, and about 85 (16.73%) had an opportunistic infection (OIs) other than TB. From the total study subjects, about 157 (30.9%) experienced at least one ART drug side effect (Table 2).

3.3. The Incidence Rate of LTFU

A total of 508 patients on ART were followed for a minimum of 0.5 and a maximum of 54.1 months of the follow-up period. The total follow-up period was 10,462.5 person-months (871.9 person-years) of observation, and the median follow-up period was 16.1 months (IQR; 5.9–33.6). At the end of the follow-up period, a total of 46 (9.1%) patients experienced loss to follow-up, 16 (3.2%) died and were defaulters, 55 (10.8%) transferred out, 292 (57.48%) were kept on an initial regimen, and 99 (19.5%) of patients changed their initial regimen. Hence, the overall incidence of loss to follow-up was estimated to be 5.3 (95% CI: 3.9-7.1) per 100 person-years of observation (PYs). From the total incidence rate of loss to follow-up, 4.0/100 PY, 40.5/PY, and 54.1 attributed to good, fair, and poor levels of adherence, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence rate of loss to follow-up among HIV-positive adults on ART in Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Characteristics | Categories | Person-time (PY) | Failures (LTFU) | Rate (IR) | 95% CI (IR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of adherence | Good | 844.8 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.03-0.05 |

| Fair | 4.9 | 2 | 0.41 | 0.10-1.62 | |

| Poor | 22.2 | 12 | 0.54 | 0.31-0.95 | |

| Residence | Urban | 672.9 | 26 | 0.04 | 0.03-0.06 |

| Rural | 199.0 | 20 | 0.10 | 0.06-0.16 | |

| Baseline age | <35 years | 400.4 | 32 | 0.08 | 0.06-0.11 |

| ≥ 35 years | 471.5 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.02-0.05 | |

| Baseline weight | ≤60 kg | 653.6 | 31 | 0.05 | 0.03-0.07 |

| >60 kg | 218.3 | 15 | 0.07 | 0.04-0.11 | |

| Total (overall incidence rate) | 871.9 | 46 | 5.3 | 0.039-0.071 | |

CI: confidence interval; IR: incidence rate; LTFU: loss to follow-up; PYs: person-years; kg: kilogram.

3.4. Time until the LTFU

In this study, the probability of cumulative survival was 90%, 88%, and 86% at the end of one-two, three, and four years, respectively. The overall Kaplan–Meir survival function estimate showed that most of the loss to follow-up from the initial ART regimen occurred in the earlier year of ART initiation, which declined in the later years of follow-up (Table 4, Figure 1). Regarding the survival estimate difference by residence, patients in the urban areas had better mean survival time than those in the rural areas and the difference was significant (p value = 0.002) (Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 4.

Life table on the incidence rate of LTFU among adult HIV patients at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Interval | Beg. total | LTFU | Withdraw | At risk | Proportion of surviving | Cum. proportion of surviving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 508 | 34 | 166 | 425 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| 1–2 | 308 | 7 | 100 | 258 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| 2–3 | 201 | 3 | 79 | 161 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| 3–4 | 119 | 2 | 83 | 77 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| 4–5 | 34 | 0 | 34 | 17 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

LTFU: loss to follow-up; Beg.: beginning; Cum.: cumulative.

Figure 1.

The Kaplan–Meier estimate of the loss to follow-up among adult patients attending the ART clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019.

Table 5.

Estimated survival time of ART patients over specific categories among adult patients attending the ART clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Variables | Categories | Mean survival time (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Residence | Urban | 4.15 (4.02-4.28) |

| Rural | 3.58 (3.27-3.89) | |

| Age (in years) | Less than 35 years | 3.83 (3.61-4.05) |

| Greater than or equal to 35 years | 4.23 (4.08-4.37) | |

| Weight (in kg) | Less than 60 kg | 4.07 (3.93-4.22) |

| Greater than or equal to 60 kg | 3.89 (3.62-4.18) | |

| Level of adherence | Good | 4.16 (4.04-4.27) |

| Fair | 1.08 (0.55-1.62) | |

| Poor | 1.76 (0.91-2.61) |

CI: confidence interval; kg: kilogram.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan–Meier estimate of the loss to follow-up in resident categories among adult patients attending the ART clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019.

3.5. Log-Rank Estimate of the Variables

The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) estimate of the loss to follow-up among variables was estimated for sociodemographic-, clinical-, immunological-, and treatment-related variables. Among all variables, the age, residence, level of adherence, disclosure status, regimen change, side effect, and treatment duration had a p value less than 0.05. There was a marginal significant difference within categories of occupational status and baseline WHO clinical staging (Table 6).

Table 6.

The log-rank estimate of variables among adult patients attending the ART clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Variables | Log rank estimate | Variables | Log rank estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ 2 | p values | χ 2 | p values | ||

| Age (in years) | 9.001 | 0.003 | HGB | 0.045 | 0.835 |

| Sex | 0.034 | 0.854 | Creatinine | 0.578 | 0.447 |

| Marital status | 0.293 | 0.961 | ALT | 0.792 | 0.374 |

| Educational status | 1.457 | 0.692 | Level of adherence | 76.508 | <0.001 |

| Religion | 6.116 | 0.106 | Disclosure status | 6.401 | 0.011 |

| Occupation status | 3.676 | 0.055 | CPT at start | 0.001 | 0.981 |

| Residence | 9.408 | 0.002 | Comedication | 0.032 | 0.851 |

| Substance use | 1.751 | 0.186 | No. of pills per day | 0.041 | 0.840 |

| Baseline weight (in kg) | 1.596 | 0.206 | Initial regimen | 2.659 | 0.447 |

| Baseline WHO stage | 3.561 | 0.059 | Regimen change | 9.816 | 0.002 |

| Baseline functional status | 2.352 | 0.308 | Side effect | 6.424 | 0.011 |

| TB at start | 1.203 | 0.273 | Treatment duration | 154.68 | <0.001 |

| OIs other than TB | 1.221 | 0.269 | Treatment failure | 1.620 | 0.203 |

| Baseline CD4 count | 0.740 | 0.390 | EFV vs NVP based | 2.329 | 0.128 |

ALT: alanine transferase; CD: clusters of differentiation; CPT: cotrimoxazole prophylaxis therapy; EFV: efavirenz; HGB: hemoglobin; kg: kilogram; NVP: nevirapine; TB: tuberculosis; OIs: opportunistic infections; WHO: World Health Organization; χ2: chi square.

3.6. Predictors of Loss to Follow-Up

To assess the predictors of loss to follow-up, both bivariable and multivariable cox regression analyses were applied. From bivariable cox regression analysis, predictors with p values less than or equal to 0.25 were considered as the candidate variables for multivariable cox regression analysis. These were age, residence, occupational status, disclosure status, substance use, baseline weight, baseline functional status, level of adherence, baseline WHO stage, and the eligibility criteria at the start of ART (test start). In multivariable Cox regression analysis, the age, residence, level of adherence, and baseline weight were significantly associated predictors of LTFU. However, variables like a history of TB, OIs, history of cotrimoxazole prophylactic therapy, baseline CD4 count, WHO stage, and disclosure status were not significantly associated with loss to follow-up in ART (Table 7).

Table 7.

Predictors of loss to follow-up among adult patients attending the ART clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 508).

| Variables | Categories | LTFU | Censored | cHR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | <35 | 32 | 218 | 2.53 (1.35-4.75) | 1.96 (1.92-4.00)∗ |

| ≥35 | 14 | 244 | 1 | ||

| Sex | Male | 19 | 200 | 0.95 (0.53-1.71) | |

| Female | 27 | 262 | 1 | ||

| Residence | Urban | 26 | 349 | 1 | 1.98 (1.02-3.83)∗ |

| Rural | 20 | 113 | 2.42 (1.35-4.34) | ||

| Educational status | No formal education | 10 | 102 | 1.92 (0.53-6.99) | |

| Primary | 19 | 176 | 1.97 (0.58-6.66) | ||

| Secondary | 14 | 124 | 2.10 (0.60-7.32) | ||

| Tertiary and above | 3 | 60 | 1 | ||

| Occupation status | Employed | 6 | 124 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-employed | 40 | 338 | 2.26 (0.96-5.34) | 1.96 (0.73-5.27) | |

| Marital status | Single | 5 | 62 | 1 | |

| Married | 29 | 269 | 1.22 (0.47-3.16) | ||

| Divorced | 8 | 82 | 1.21 (0.39-3.69) | ||

| Widowed | 4 | 49 | 0.99 (0.27-3.71) | ||

| Disclosure status | Disclosed | 43 | 442 | 1 | 1 |

| Not-disclosed | 3 | 20 | 4.07 (1.25-13.3) | 0.93 (0.22-3.87) | |

| Substance use | Yes | 4 | 72 | 0.51 (0.18-1.41) | 0.58 (0.19-1.71) |

| No | 42 | 390 | 1 | 1 | |

| Baseline weight | ≤60 kg | 31 | 353 | 1 | 1 |

| >60 kg | 15 | 109 | 1.48 (0.80-2.75) | 2.19 (1.11-4.37)∗ | |

| Baseline functional status | Working | 41 | 354 | 1 | 1 |

| Ambulatory and bedridden | 5 | 108 | 0.54 (0.21-1.37) | 1.11 (0.32-3.92) | |

| Level of adherence | Good | 32 | 408 | 1 | 1 |

| Fair | 2 | 20 | 9.38 (2.2-39.99) | 11.5 (2.1-61.1)∗ | |

| Poor | 12 | 34 | 12.49 (6.3-24.8) | 12.03 (5.426.7)∗ | |

| Baseline WHO stage | Stage 1 | 32 | 239 90 118 15 | 1 | 1 |

| Stage 2 | 7 | 0.65 (0.29-1.50) | 0.69 (0.26-1.81) | ||

| Stage 3 | 6 | 0.42 (0.18-1.01) | 0.65 (0.23-1.89) | ||

| Stage 4 | 1 | 0.45 (0.06-3.31) | 2.14 (0.21-22.3) | ||

| Baseline CD4 count | < 200 | 16 | 161 | 1.31 (0.71-2.39) | |

| ≥ 200 | 30 | 301 | 1 | ||

| TB at start | Yes | 4 | 80 | 0.57 (0.20-1.58) | |

| No | 42 | 382 | 1 | ||

| OIs other than TB | Yes | 4 | 81 | 0.57 (0.20-1.58) | |

| No | 42 | 381 | 1 | ||

| CPT at start | Yes | 27 | 257 | 1 | |

| No | 19 | 205 | 1.01 (0.56-1.81) | ||

| Comedication other than CPT | Yes | 1 | 10 | 1.19 (0.16-8.69) | |

| No | 45 | 452 | 1 | ||

| Test-start | Yes | 25 | 213 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 21 | 249 | 0.45 (0.25-0.81) | 0.84 (0.43-1.6) | |

| Numbers of pills/day. | One | 44 | 447 | ||

| Two and above | 2 | 15 | 0 .86 (0.2-3.57) |

∗Indicates a p value < 0.05; 1: reference category; cHR: crude hazard ratio; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; kg: kilogram; TB: tuberculosis; OIs: opportunistic infections; CD4: cluster of differentiation; CPT: cotrimoxazole prophylaxis therapy; LTFU: loss to follow-up.

In this study, patients attending ART clinics who had the age less than 35 years had approximately two times higher risk of loss to follow-up when compared with those patients whose age were greater than 35 years (aHR = 1.96; 95% CI: 1.92-4.00). Regarding the residence of ART patients, those patients who were from rural areas had approximately two times higher risk of loss to follow-up as compared with counterparts (aHR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.02-3.83). Keeping other variables constant, baseline body weight had also a significant association with the incidence of loss to follow-up. Those ART patients with baseline body weight greater than 60 kilograms had a 2.19 times higher risk of LTFU as compared with counterparts with a baseline body weight less than 60 kilograms (aHR = 2.19; 95% CI: 1.11-4.37). The hazard of LTFU was also higher among adult ART patients who had fair and poor levels of adherence. Those patients who had a fair level of adherence were 11.5 times at higher risk of loss to follow-up as compared to those with a good level of adherence (aHR = 11.5; 95% CI: 2.10-61.10), and also, patients with a poor adherence level were 12.03 times at higher risk of loss to follow-up when compared with those patients with a good level of adherence (aHR = 12.03; 95% CI: 5.4-26.7) (Table 7).

4. Discussion

Loss to follow-up is the major difficulty to treatment success and it complicates the evaluation of HIV care and treatment programs [12]. This study assessed the incidence rate of loss to follow-up and its predictors among adult HIV patients who started ART. In this study, 46 (9.1%) adult HIV patients experienced loss to follow-up and the overall incidence rate of loss to follow-up was 5.3 (95% CI: 3.9-7.1) per 100 person-years of observation (PYs). This finding is consistent with the study conducted in Debre Markos, Ethiopia, which reported 3.7 per 100 person-years [22].

But, this finding is lower than the study conducted in different parts of Ethiopia, in Gondar, Ethiopia, 12.26 per 100 person-years [20], in Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia, 26.6 per 100 person-months [19], in Gondar Hospital, Ethiopia, 31.4% [18], in Pawi Hospital, Ethiopia, 11.6 per 100 person-years [21], in Gondar Hospital, Ethiopia, 10.90 per 100 person-years [16], and in Woldia, Ethiopia, 8.36 per 100 person-years [17], and higher than the study conducted in Mizan-Tepi University, Ethiopia, 8.8 per 1000 person-months [23] and in Southern Ethiopia 6.48 per 1000 person-months [11]. Besides, the finding of this study is also lower than the report of loss to follow-up of adult HIV patients from the treatment program from various settings out of Ethiopia, in Mbarara, Uganda, 22.85% with 16%, 30%, and 39% at 1, 2, and 3 years of initiation of treatment, respectively, and Southwestern Uganda, 26.7 per 100 person-years, similar setting in 24.6%, Masaka, Uganda, 7.5 per 100 person-years [12, 39, 46, 47], and in Southeastern Nigeria Hospital 23.9% [15].

This variation in the incidence rate might be due to the differences in setting, time variation, the difference in the follow-up period, health-seeking behaviors, and difference in the sociodemographic characters of the study participants, and the commencing of test and start ART criteria may be the other possible reason; in this study, 46.9% patients initiated their treatment by test and start eligibility criteria as compared to those of other studies. The lower incidence rate of this study from many reports that are listed above also might be due to an improvement in ART adherence, tracing back of HIV patients who lose their follow-up, and early initiation of treatment has been adapted recently to get the expected good clinical outcomes and improve the quality of life of HIV patients ultimately [48].

Regarding the characteristics of cohorts, in present study, a majority (77.8%) of study participants were in working functional status at baseline, and also, about (53.4%) were in WHO clinical stage one, (60.2%) having a hemoglobin level between 10 and 12.9 g/dL, and the median CD4 count at baseline was 281.5 cell/mm3. And also, only 16.5% of the study participants had been diagnosed with tuberculosis at the start of ART and about 16.73% had another opportunistic infection when compared with the previous studies. This all might make the lowest level of LTFU in present study. This recent study can reflect the implementation of different stakeholders' strategies.

In this study, from the total patients who experienced loss to follow-up, a majority, 34 (93.9%), lost from ART service within the first year of treatment initiation. The probability of cumulative survival was 90%, 88%, and 86% at the end of one, two, three, and four years, respectively. In this study setting, we found that a progressive decrease in the incidence rate of LTFU of HIV patients within each year after initiation of ART. This finding is in agreement with the study finding from Jigjiga town, Ethiopia [19]. This progressive decrease might be because the Ethiopian health care delivery approach decentralizes the care from referral centers to primary health care facilities; this makes the clinics closer to patients' homes requiring them to travel less and minimizes transport costs. This proximity can also make tracing more easy and feasible from decentralized clinics. Another possible reason might be the enhancement of community outreach services, such as involving community health workers, recording detailed information of each patient following ART clinics, and probably expanding the peer outreach program [49, 50].

In this study, patients whose age less than 35 years had a 1.96 times higher risk of loss to follow-up when compared with those patients whose age is above 35 years. In agreement with this study, younger age groups were more likely to lose to follow-up from ART service as compared to older age categories in the report of studies in Gondar, Ethiopia [16], Pawi General Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia [51], in South Africa [52], Nigeria [36], Oromia region, Ethiopia [33], and India [35]. The possible reason might be that the younger age group could be more mobile than the older one and may face the fear of discrimination and stigma. The other possible reasons might be immaturity in analytical thinking and particular challenges associated with young age.

Regarding the residence of HIV patients following the ART clinic, those patients who had rural residence were 1.98 times at higher risk of loss to follow-up as compared with their counterparts. This result is congruent with different studies done in the Oromia region, Ethiopia [33]. This might be because patients from the rural area may face a problem of accessibility or distance from treatment centers, transport-related costs, low level of awareness on the benefit and risk related to the adherence of treatment, and social stigma related to a disease HIV/AIDS. In contrary to this finding, a study done in Debre Markos, Ethiopia, reported that the risk of LTFU among rural residents was reduced by 40% when compared with urban residents [22]. The possible reason given is that study were patients coming from rural areas preferred to have ART follow-up in the nearby hospitals; this is because rural residents are stable or permanent residents compared to urban residents and due to the scarcity of money; they may not use the self-referral system to other healthcare institutions when compared to urban residents [22].

Furthermore, baseline body weight had also a significant association with loss to follow-up in this study. Those ART patients with baseline weight greater than 60 kilograms were 2.19 times at higher risk of LTF as compared with those with baseline weight less than 60 kilograms. The possible reason could be, even though BMI was not computed in this study, those patients with higher body weight might face noncommunicable diseases which have been associated with overweight and obesity and this could affect their retention in care, and due to these chronic noncommunicable diseases, they might have a suboptimal (fair/poor) adherence level which is a predictor of LTFU in the present study. Another reason might be that patients with normal body weight would like to maintain their good wellbeing (i.e., they do not want to lose) by taking ART so that they stay longer in the program when compared to those whose body weight is not normal [38].

The adherence status had a statistically significant association with the incidence rate of LTFU. The risk of LTFU was higher among adult ART patients with fair and poor levels of adherence. Those patients who had a fair level of adherence were 11.5 times at higher risk of loss to follow-up as compared to those with a good level of adherence, and patients with a poor adherence level were 12.03 times at higher risk of loss to follow-up when compared with those patients with a good level of adherence. This finding is in agreement with a study done in Gondar, Ethiopia [20], Oromia region, Ethiopia [33]. These two studies merged fair and poor adherence statuses and defined it as suboptimal adherence. In both studies, patients with the suboptimal level of adherence were at a higher risk of loss to follow-up when compared to the good or optimal level of adherence. The possible explanation might be that those patients with fair and poor/suboptimal adherence levels may have different sociodemographic, economic, and clinical problems that affect their adherence initially which further affect their retention in HIV/AIDS care.

Variables like alcohol/drug use and prescription of many pills/day were not statistically significant in this study. The possible reasons might be that the number of substance users in present study was only 1.5% and those patients who were receiving two and more pills per day were only 0.3%.

As limitations, due to the nature of the secondary source of data, some missed variables like the BMI, status of mental illness, stigma and discrimination, viral load, distance from the health facility, cell phone possession, and having a caregiver might be predictors. In addition to these, charts with an incomplete record of 20% and transferred outpatients were excluded; this might lead to underestimating or overestimating the incidence rate of loss to follow-up.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the incidence rate of loss to follow-up was estimated to be low when compared with a majority of previous studies. A majority of loss to follow-up occurred within the first year of ART initiation. Younger adults below the age of 35 years, living in rural areas, had a baseline body weight greater than 60 kilograms, had a fair and poor adherence level, and were more likely to be lost from treatment. Therefore, health professionals working in ART clinics and potential stakeholders in HIV/AIDS care and treatment should give emphasis for above characteristics. They should give health education about the effects of LTFU and the benefits of retention in the ART program for adult patients below the age of 35 years, visits to ART clinic from the rural (distant) areas, having baseline body weight above 60 kilograms, and having a suboptimal (fair and poor) adherence level. Furthermore, a prospective cohort study needs to be conducted and a qualitative study should be applied to obtain information from LTFU patients themselves by tracing them and the health service quality and satisfaction level of patients need to be addressed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the administrator of Arba Minch General Hospital for the permission to conduct the study and for providing access to the data. We also would like to acknowledge data collectors and supervisors for accomplishing their tasks. Funding for this study was obtained from Arba Minch University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Abbreviations

- aHR:

Adjusted hazard ratio

- AIDS:

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- ART:

Antiretroviral therapy

- CD4:

Cluster of differentiation

- CPT:

Cotrimoxazole prophylactic therapy

- EPHIA:

Ethiopia population-based HIV impact assessment

- HIV:

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IRB:

Institution review board

- IQR:

Interquartile range

- LTF:

Loss to follow-up

- OIs:

Opportunistic infections

- PLWHIV:

People living with HIV

- PYs:

Person-years

- PMs:

Person-months

- TB:

Tuberculosis

- UNAIDS:

Joint United Nation Program on HIV/AIDS

- WHO:

World Health Organization.

Data Availability

All generated and analyzed datasets are available with a reasonable request through the corresponding author.

Ethical Approval

Institution Review Board (IRB) of Medicine and Health Sciences College, Arba Minch University, gave the ethical clearance with approval number of CMHS/12,033,792/11. Through a support letter from the Department of Public Health, the administration of Arba Minch General Hospital was informed about the objective of the study and permission was obtained before the data collection. This study used the routine existing data from the patients' charts. The confidentiality of the information was assured by using an anonymous tool and keeping the data in a secured place. Besides, this study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Authors' Contributions

MAG conceived and designed the study, performed analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the first manuscript. MKG, HNW, MMM, and DAB participated in data collection, data entry, and critical review of the subsequent draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.UNAIDS Global. HIV/AIDS statistics—2018 fact sheet Geneva 2019. May 2021, http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- 2.EPHI. The Ethiopian public health institute. HIV-related estimates and projections in Ethiopia for the year 2019 . 2020.

- 3.EPHIA. Ethiopia population-based HIV impact assessment EPHIA 2017–2018, summary sheet: preliminary findings Ethiopia. December 2018, https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2018/12/3511%E2%80%A2EPHIA-SummarySheet.

- 4.May M. T., Gompels M., Delpech V., et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS . 2014;28(8):1193–1202. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. HIV/AIDS Fact Sheets. May 2021, https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- 6.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics — 2019 Fact Sheet 2019. 2021, https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- 7.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Fast-track: ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 . Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. 2021 https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report. [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. Ending AIDS Progress towards the 90–90–90 Targets: Global AIDS Update . Geneva: UNAIDS.org; 2017. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/20170720_Global_AIDS_update_2017 . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkhof M. W., Pujades-Rodriguez M., Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment Programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One . 2009;4(6, article e5790) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekolo C. E., Webster J., Batenganya M., Sume G. E., Kollo B. Trends in mortality and loss to follow-up in HIV care at the Nkongsamba Regional Hospital, Cameroon. BMC Research Notes . 2013;6(1) doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dessu S., Mesele M., Habte A., Dawit Z. Time until loss to follow-up, incidence, and predictors among adults taking ART at public hospitals in Southern Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) . 2021;13:205–215. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S296226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuwagira E., Lumori B. A., Muhindo R., et al. Incidence and predictors of early loss to follow up among patients initiated on protease inhibitor-based second-line antiretroviral therapy in southwestern Uganda. AIDS Research and Therapy . 2021;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12981-021-00331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen S., Fox M. P., Gill C. J. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine . 2007;4(10, article e298) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leroy V., Malateste K., Rabie H., et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral therapy in children in Asia and Africa: a comparative analysis of the IeDEA pediatric multiregional collaboration. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) . 2013;62(2):208–219. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827b70bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eguzo K., Lawal A. K., Umezurike C. C., Eseigbe C. E. Predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV-infected patients in a rural South-Eastern Nigeria hospital: a 5-year retrospective cohort study. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research . 2015;5(6):373–378. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.177988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teshale A. B., Tsegaye A. T., Wolde H. F. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow up among adult HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy in University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital: a competing risk regression modeling. PLoS One . 2020;15(1, article e0227473) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dejen D., Jara D., Yeshanew F., et al. Attrition and its predictors among adults receiving first-line antiretroviral therapy in Woldia town public health facilities, Northeast Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) . 2021;13:445–454. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S304657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wubshet M., Berhane Y., Worku A., Kebede Y., Diro E. High Loss to Followup and Early Mortality Create Substantial Reduction in Patient Retention at Antiretroviral Treatment Program in North-West Ethiopia. International Scholarly Research Notices . 2012;2012:9. doi: 10.5402/2012/721720.721720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seifu W., Ali W., Meresa B. Predictors of loss to follow up among adult clients attending antiretroviral treatment at Karamara general hospital, Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mekonnen N., Abdulkadir M., Shumetie E., Baraki A. G., Yenit M. K. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV infected adults after initiation of first line anti-retroviral therapy at University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital Northwest Ethiopia, 2018: retrospective follow up study. BMC Research Notes . 2019;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assemie M. A., Muchie K. F., Ayele T. A. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow up among HIV-infected adults at Pawi General Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: competing risk regression model. BMC Research Notes . 2018;11(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3407-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birhanu M. Y., Leshargie C. T., Alebel A., et al. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV-positive adults in Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Tropical Medicine and Health . 2020;48(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berheto T. M., Haile D. B., Mohammed S. Predictors of loss to follow-up in patients living with HIV/AIDS after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. North American Journal of Medical Sciences . 2014;6(9):453–459. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.141636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyugi J. H., Byakika-Tusiime J., Ragland K., et al. Treatment interruptions predict resistance in HIV-positive individuals purchasing fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda. Aids . 2007;21(8):965–971. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802e6bfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbas U. L., Anderson R. M., Mellors J. W. Potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1 transmission and AIDS mortality in resource-limited settings. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2006;41(5):632–641. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194234.31078.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaecher K. L. The importance of treatment adherence in HIV. The American Journal of Managed Care . 2013;19(12 Supplement):s231–s237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H., Zhou J., He G., et al. Consistent ART adherence is associated with improved quality of life, CD4 counts, and reduced hospital costs in Central China. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses . 2009;25(8):757–763. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mberi M. N., Kuonza L. R., Dube N. M., Nattey C., Manda S., Summers R. Determinants of loss to follow-up in patients on antiretroviral treatment, South Africa, 2004–2012: a cohort study. BMC Health Services Research . 2015;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0912-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X., Margolick J. B., Conover C. S., et al. Interruption and discontinuation of highly active antiretroviral therapy in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2005;38(3):320–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hønge B. L., Jespersen S., Nordentoft P. B., et al. Loss to follow-up occurs at all stages in the diagnostic and follow-up period among HIV-infected patients in Guinea-Bissau: a 7-year retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open . 2013;3(10):p. e003499. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb S., Hartland J. A retrospective notes-based review of patients lost to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy at Mulanje mission hospital, Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal . 2018;30(2):73–78. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v30i2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onoka C., Uzochukwu B., Onwujekwe O., et al. Retention and loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in Southeast Nigeria. Pathogens and Global Health . 2012;106(1):46–54. doi: 10.1179/2047773211Y.0000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Megerso A., Garoma S., Eticha T., et al. Predictors of loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment for adult patients in the Oromia region, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) . 2016;8:p. 83. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S98137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akilimali P. Z., Musumari P. M., Kashala-Abotnes E., et al. Disclosure of HIV status and its impact on the loss in the follow-up of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programs in a (post-) conflict setting: a retrospective cohort study from Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS One . 2017;12(2, article e0171407) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez-Uria G., Naik P. K., Pakam R., Midde M. Factors associated with attrition, mortality, and loss to follow up after antiretroviral therapy initiation: data from an HIV cohort study in India. Global Health Action . 2013;6(1):p. 21682. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meloni S. T., Chang C., Chaplin B., et al. Time-dependent predictors of loss to follow-up in a large HIV treatment cohort in Nigeria. Open Forum Infectious Diseases . 2014;1(2) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eshun-Wilson I., Rohwer A., Hendricks L., Oliver S., Garner P. Being HIV positive and staying on antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a qualitative systematic review and theoretical model. PLoS One . 2019;14(1, article e0210408) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tadesse K., Fisiha H. Predictors of loss to follow up of patients enrolled on antiretroviral therapy: a retrospective cohort study. J AIDS Clin Res . 2014;5(12):p. 2. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asiimwe S. B., Kanyesigye M., Bwana B., Okello S., Muyindike W. Predictors of dropout from care among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy at a public sector HIV treatment clinic in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2015;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1392-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odafe S., Idoko O., Badru T., et al. Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics and level of care associated with lost to follow-up and mortality in adult patients on first-line ART in Nigerian hospitals. Journal of the International AIDS Society . 2012;15(2):p. 17424. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.FMOH. National guidelines for comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment 2017. 2017. July 2020, https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/resources/ethiopia_art_guidelines_2017.pdf.

- 42.Cohen M. S., Chen Y. Q., McCauley M., et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. The New England Journal of Medicine . 2016;375 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization. Edition 1 for field testing and country adaptation . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. Monitoring services, patients and programmes operations manual for delivery of HIV prevention, care and treatment at primary health centres in high-prevalence, resource-constrained settings. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisiha Kassa S., Zemene Worku W., Atalell K. A., Agegnehu C. D. Incidence of loss to follow-up and its predictors among children with HIV on antiretroviral therapy at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital: a retrospective data Analysis. HIV/AIDS . 2020;12:525–533. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S269580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alemu M., Gurara M. K., Nigussie H. Incidence and predictors of initial antiretroviral therapy regimen change among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care . 2020;Volume 12:315–329. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S254386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geng E. H., Bangsberg D. R., Musinguzi N., et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) . 2010;53(3):405–411. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiwanuka J., Mukulu Waila J., Muhindo Kahungu M., Kitonsa J., Kiwanuka N. Determinants of loss to follow-up among HIV positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a test and treat setting: a retrospective cohort study in Masaka, Uganda. PLoS One . 2020;15(4, article e0217606) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO (World Health Organization) Guidelines for managing advanced HIV disease and rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/redirect/9789241550062 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Connor C., Osih R., Jaffer A. Loss to follow-up of stable antiretroviral therapy patients in a decentralized down-referral model of care in Johannesburg, South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes . 2011;58(4):429–432. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230d507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukora R., Charalambous S., Dahab M., Hamilton R., Karstaedt A. A study of patient attitudes towards decentralisation of HIV care in an urban clinic in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research . 2011;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Assemie M. A., Leshargie C. T., Petrucka P. Outcomes and factors affecting mortality and successful tracing among patients lost to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy in Pawi Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine and Health . 2019;47(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s41182-019-0181-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnesen R., Moll A. P., Shenoi S. V. Predictors of loss to follow-up among patients on ART at a rural hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One . 2017;12(5, article e0177168) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All generated and analyzed datasets are available with a reasonable request through the corresponding author.