Abstract

Mouse Staufen (mStau) is a double-stranded RNA-binding protein associated with polysomes and the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER). We describe a novel endogenous isoform of mStau (termed mStaui) which has an insertion of six amino acids within dsRBD3, the major double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding domain. With a structural change of the RNA-binding domain, this conserved and widely distributed isoform showed strongly impaired dsRNA-binding ability. In transfected cells, mStaui exhibited the same tubulovesicular distribution (RER) as mStau when weakly expressed; however, when overexpressed, mStaui was found in large cytoplasmic granules. Markers of the RER colocalized with mStaui-containing granules, showing that overexpressed mStaui could still be associated with the RER. Cotransfection of mStaui with mStau relocalized overexpressed mStaui to the reticular RER, suggesting that they can form a complex on the RER and that a balance between these isoforms is important to achieve proper localization. Coimmunoprecipitation demonstrated that the two mStau isoforms are components of the same complex in vivo. Analysis of the immunoprecipitates showed that mStau is a component of an RNA-protein complex and that the association with mStaui drastically reduces the RNA content of the complex. We propose that this new isoform, by forming a multiple-isoform complex, regulates the amount of RNA in mStau complexes in mammalian cells.

RNA transport and localization provide an efficient way to distribute genetic information and to allow different portions of the cell to establish their own biochemical fates (12, 20, 32, 44). Examples of this process have been described in many different organisms and cell types. RNA localization and/or localized translation are linked to different biological processes such as asymmetric cell division (7, 28, 39, 45), long-term potentiation (30), synaptic transmission (40), cell motility (23), and axis formation in oocytes (44). It is now apparent that many determinants of RNA localization are conserved among these systems. The process of mRNA localization is initiated by association of RNA with one or more RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) through a targeting signal most commonly located in the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of the transcripts. This association results in the formation of large ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) (1, 13, 24). These complexes then migrate along the cytoskeleton to their final destination, where they are anchored and translated. For the entire localization process, translation of localized mRNAs needs to be tightly regulated. Specific signals are important for repressing translation during mRNA transport and derepressing translation once RNPs are properly localized (15, 21, 22). The crucial role played by the cytoskeleton in many steps of transport, anchoring, and translation (2, 34, 41, 47) is another feature which appears to be conserved in numerous RNA localization systems. The multistep process of RNA localization is dependent on specific trans-acting proteins. Thus, it is essential to identify and characterize these proteins and to study their localization and regulation. Recent work has identified several classes of proteins as components of RNP involved in mRNA transport (20). These include members of the double-stranded RBP (dsRBP) family (25, 43), homologues of the zipcode-binding protein (10, 11, 16, 36), and members of the hnRNP family (3, 17, 33).

Mammalian Staufen, a member of the dsRBP family, contains four copies of the dsRBD consensus motif (29, 46), now designated dsRBD2 to dsRBD5 for consistency with the Staufen domains in Drosophila (43). In vitro, Staufen was shown to bind dsRNA without sequence specificity (29, 46). Molecular mapping of the functional domains related the RNA-binding activity mainly to dsRBD3, with a weaker activity mapped to dsRBD4 (46). Similarly, the spacer region between dsRBD4 and dsRBD5, which resembles the tubulin-binding domain of MAP1B, was shown to bind tubulin in vitro (46). In fibroblasts, Staufen is associated with polysomes and the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) (29, 46), whereas in neurons, it is associated with both the RER and microtubules (19). In expression studies in neurons, Staufen was demonstrated to be a component of RNA-containing granules migrating in both anterograde and retrograde manners along the dendrites (25). This was persuasive evidence that Staufen is involved in mRNA transport in mammals. However, challenging questions remain about the precise role of each Staufen isoform; the function of the multiple domains in Staufen protein; and the nature of its interaction with RNAs, protein cofactors, RER, and the cytoskeleton.

Recent studies in Drosophila have provided important clues about the function of Staufen. In Drosophila, Staufen is necessary for bicoid and oskar mRNA localization to the anterior and posterior poles of the oocyte, respectively (21, 42), and for prospero mRNA localization in neuroblasts (7, 27, 39). Out of the five copies of the dsRBD consensus sequences, dsRBD3 was shown to bind bicoid and prospero mRNAs in vitro (27, 43); dsRBD5 was shown to be involved in protein-protein interactions (39), demonstrating that Staufen is involved in both RNA-protein and protein-protein interactions. Although direct binding to bicoid RNA has not yet been shown in vivo, intermolecular bicoid RNA-RNA interactions are important for recruiting Staufen in the RNP complexes (14). In contrast, Staufen directly interacts with Oskar protein via its N-terminal domain in oocytes (5) and with Inscuteable and Miranda in neuroblasts through its C-terminal half and fifth dsRBD, respectively (27, 39). Staufen expression is also important for derepression of the localised oskar mRNA translation (5).

Recently we reported the molecular cloning and characterization of human (hStau) and mouse (mStau) Staufen (46). We now report that a novel endogenous Staufen isoform (mStaui) containing a six-amino-acid insertion within its major dsRBD (dsRBD3) shows a severe reduction in its RNA-binding capacity in vitro. Our results show that this isoform, along with mStau, are components of RNA-protein complexes and that the ratio of the two isoforms is important for the proper subcellular localization of mStaui. Finally, analyses of Staufen-containing complexes demonstrate that increasing the incorporation of mStaui drastically reduces the amount of RNA in these complexes. These results provide new insights into the mechanism of regulation of mStau function in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular cloning and sequencing of the cDNAs.

The cloning of the short isoform of a mouse staufen homologue from a fetal total mouse cDNA library was previously described (46). DNAs from the isolated λGT10 clones were subcloned into a Bluescript vector (Stratagene). Double-stranded DNAs were sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide method according to the Sequenase protocols (United States Biochemical Corp.).

RT-PCR.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was conducted according to the Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp RNA PCR protocol. This experiment was performed with 1 μg of total RNA isolated from different tissues and cell lines. Reverse transcription was carried out in the presence of oligo(dT)16 primer, and PCR amplification incorporated the use of the mouse-specific sense and antisense primers 5′-GACCACCCGTGAAACACGATGCCCC-3′ (positions 495 to 519; GenBank accession number AF061942) and 5′-TCCCTTCACCTTCCCCCACAAACTCCC-3′ (positions 755 to 729; GenBank accession number AF061942), respectively. For human and monkey cDNAs, we used the human-specific sense primer 5′-GACAGGCTGCGAAACACGATGCTGC-3′ (positions 478 to 502; GenBank accession number AF061940) and the mouse antisense primer. Aliquots of the amplified products were collected after 25, 28, 30, 32, and 35 PCR cycles and were run on agarose gels to test the linearity of the PCR reaction (not shown). Only PCR products obtained by 32 cycles of amplification are shown in Fig. 2.

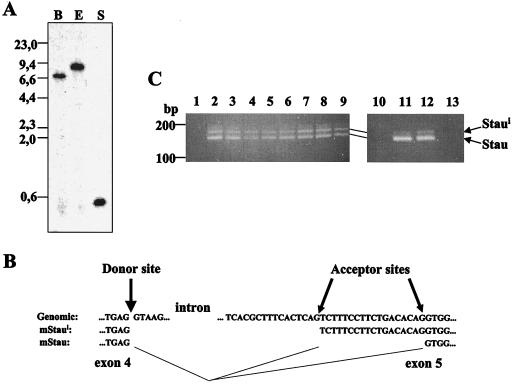

FIG. 2.

Characterization of the mStau gene and transcripts. (A) Southern blot analysis. Mouse genomic DNA was digested with BamHI (lane B), EcoRI (lane E), and SacI (lane S), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and hybridized with a 191-nucleotide cDNA fragment that covers a single exon (nucleotides 57 to 248). DNA molecular weight markers in kilobase pairs are indicated on the left. (B) Genomic characterization of the splicing sites. Genomic and cDNA sequences are aligned, and the positions of splicing consensus sequences are indicated. (C) Differential splicing of the mStau gene. RT-PCR amplification of mRNAs isolated from mouse tissues (lanes 2 to 9 and 13), human HeLa cells (lane 11), and monkey COS-1 cells (lane 12). Lane 2, brain; lane 3, heart; lane 4, liver; lane 5, lungs; lane 6, spleen; lane 7, kidney; lane 8, male genitals; lane 9, female genitals, lane 11, HeLa cells; lane 12, COS-1 cells; lane 13, mouse NIH/3T3; lanes 1 and 10, negative controls.

Construction of fusion proteins.

Maltose-binding protein (MBP)–dsRBD3 and MBP-dsRBD3i were constructed first by amplifying a fragment using the primer pair 5′-CAATGTATAAGCCCGTGGACCC-3′ and 5′-AAAAAGCTTGTGCAAGTCTACTAATAGGATTCATCC-3′ with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs). The resulting product was digested with HindIII and cloned into the EagI* and HindIII sites of a modified pMal-c vector (pMal-stop). To produce this vector, we introduced stop codons at the HindIII site of pMal-c by the ligation of the annealed complementary oligonucleotides 5′-AGCTTAATTAGCTGAC-3′ and 5′-AGCTGTCAGCTAATTA-3′. EagI* was created by filling in the cohesive ends of EagI-digested pMal-c vector using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. This vector was used to purify the 398-bp PstI and HindIII fragment, which then was subcloned in the pMAL-stop vector to generate the mStau-RBD3 construct. These MBP-dsRBD3 fusion plasmids were introduced into Escherichia coli strain BL-21. The fusion proteins were obtained after induction with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 2 to 3 h. Cells were lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer for immediate use or frozen at −80°C for storage.

His-Stau and His-Staui fusion proteins were amplified using primer pair 5′-TCTGGATCCGAAAGTATAGCTTCTACCATTG-3′ and 5′-TACAATCTAGATTATCAGCGGCCGCCCTCCCGCACGCTGAAAC-3′, and the resulting fragment was cloned blunt in Bluescript EcoRV site. The fragment resulting from digestion with NotI and BamHI was subcloned in the pET21a vector, resulting in the proper frame for fusion with the encoded His6 tag.

Antibody production and Western blotting.

Polyclonal anti-Staufen antibodies were obtained by injection of purified His-hStau fusion protein into rabbits as previously described (46). For Western blotting, cells were lysed in 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, and 1 μg of pepstatin A per ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Protein extracts were quantified by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of proteins were separated on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 30 min in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 5% dry milk and incubated with primary antibodies in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.05% Tween for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was performed by incubating the blots with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (Dimension Labs) and with the Supersignal substrate (Pierce).

RNA binding assay.

Bacterial extracts from IPTG-induced cultures or affinity-purified fusion proteins were separated on SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gels, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Increasing amounts of bacterial extracts and of affinity-purified fusion proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Amounts of mStau and mStaui were quantitated by Western blotting. Equal amounts were then loaded on the gel for the Northwestern assay. RNA interaction was detected by Northwestern assay using 32P-labeled 3′ UTR of bicoid RNA as previously described (46).

Immunofluorescence.

mStau tagged with hemagglutinin epitope (HA) and mStau tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) were constructed by PCR amplification of the full-length cDNA using the primer pair 5′-TCTGGATCCGAAAGTATAGCTTCTACCATTG-3′ and 5′-TACAATCTAGATTATCAGCGGCCGCACCTCCCGCACGCTGAAAC-3′. The 3′ primer was synthesized with a NotI site just upstream from the stop codon, allowing ligation of a NotI cassette containing either the GFP sequence or three copies of the HA tag. After digestion with BamHI and XbaI, the resulting fragment was cloned in Bluescript. The BamHI/XbaI fragment was then subcloned in the pCDNA3/RSV vector (18), and a NotI cassette was introduced at the NotI site. Mammalian cells were transfected transiently with the cDNAs by the calcium phosphate precipitation technique, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 25 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Nonspecific sites were then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS–0.3% Triton X-100 and incubated with mouse anti-HA for 1 h at room temperature as indicated. Cells were washed in permeabilization buffer and incubated with Texas red-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) in blocking buffer for 1 h. GFP and GFP fusion proteins were detected by autofluorescence.

For the analysis of cytoskeleton-associated proteins, transfected cells were first extracted in 0.3% Triton X-100–130 mM HEPES (pH 6.8)–10 mM EGTA–20 mM MgSO4 for 5 min at 4°C as previously described (46). They were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde–PBS and processed for immunofluorescence as described above. Cells were visualized by immunofluorescence using the 63× planApochromat objective of a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope. Confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss 410 confocal microscope using a 63× planapochromat objective (Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, McGill University). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and rhodamine channel images were obtained sequentially to prevent overlap of the two signals.

Immunoprecipitation.

COS-1 cells were transfected with 6 μg of DNA using the FUGENE-6 reagent (Roche Biochemicals), washed in PBS 36 h posttransfection, and then harvested in 1 ml of lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100–50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 15 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride per ml, standard protease inhibitor cocktail). The lysate was incubated at 4°C for 1 h and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. Proteins in the supernatant were quantified, and aliquots were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting to confirm expression of each protein. For immunoprecipitation, 1 mg of total extract was preincubated with anti-HA ascites fluid (1/250) for at least 6 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was incubated for 4 h at 4°C in the presence of 50 μl of a ∼60% protein A-Sepharose slurry equilibrated in lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 500 × g for 30 s at 4°C. The pellet was washed four times in lysis buffer, resuspended in reducing sample buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using polyclonal anti-GFP (1/100; Clontech) or anti-Stau (1/500) antibodies.

To study the RNA content of the immunoprecipitates, COS-1 cells were transfected with 25 μg of DNA (total) by the calcium phosphate method. Cells were lysed in the lysis buffer containing RNase inhibitors, and the proteins (10 mg) were immunoprecipitated as described above. One-tenth of the immunoprecipitate was directly analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, while the remaining immunoprecipitate was resuspended in 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4)–200 mM dithiothreitol–4% SDS at 95°C for 5 min, extracted with Trizol, and precipitated. RNA was dissolved in 10 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, separated on formaldehyde-agarose gel, and analyzed by hybridization using 32P-labeled 20-mer oligonucleotides of random sequences.

RESULTS

mStaui is a novel mStau isoform produced by alternative splicing.

We previously reported the cloning of the short isoform of mStau from a mouse total embryonic cDNA library (46). The encoded mStau protein is 91% identical to its human counterpart, and its genetic organization is identical. We showed that mStau binds dsRNA and tubulin in vitro and that the RNA-binding activity maps mainly to dsRBD3 but also weakly to dsRBD4 (46). Analysis of the mouse staufen cDNAs allowed us to identify a novel endogenous transcript containing an 18-bp insertion within the sequence coding for dsRBD3 (Fig. 1). We designated this isoform mStaui. Except for the sequence of the insertion, the cDNAs coding for each isoform are 100% identical. In addition, hybridization of mouse genomic DNA with a 191-bp fragment of staufen cDNA (nucleotides 57 to 248) revealed a single band on a Southern blot, independent of the restriction enzyme used (Fig. 2A). The staufen gene is therefore present in the mouse genome as a single copy. Characterization of the corresponding genomic sequence further revealed that the transcripts are generated by differential splicing, choosing either of two splicing acceptor sites (Fig. 2B). Similar genomic organization is observed in the human genome, suggesting that this phenomenon is conserved among mammals (6).

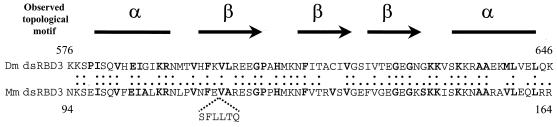

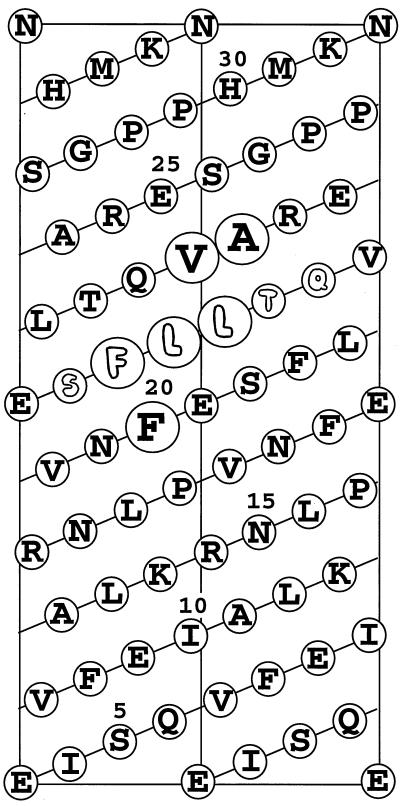

FIG. 1.

Sequence comparison of Drosophila (Dm; GenBank accession number M69111) and mouse (Mm) Staufen dsRBD3 domains. The position and sequence of the six-amino-acid insert in mStaui are indicated. Colons and dots represent identical and conserved amino acids. Amino acids included in the consensus described by Krovat and Jantsch (26) are identified in bold. Topological motifs adopted by the Drosophila domain (8) are presented schematically above the sequences.

To establish the in vivo relevance of this transcript, we first confirmed its presence in mouse tissues and determined its level of expression relative to that of mStau. RT-PCR experiments on eight mouse tissues using oligonucleotide primers located on each side of the insert showed that mStaui was expressed in every tested tissue (Fig. 2C). In a single tissue, the steady-state level of mStaui transcript was slightly lower than that of mStau (Fig. 2C). We then tested whether this phenomenon was conserved among different species. Using primers specific for the human sequence, we amplified fragments corresponding to transcripts both in humans (HeLa cells) and in monkeys (COS-1 cells) (Fig. 2C, lanes 11 and 12). The human-specific primers did not amplify mouse transcripts (lane 13), thus demonstrating the specificity of the amplification products. Interestingly, the ratio of mStaui to mStau was decreased in these cell lines, suggesting that it may be subject to regulation. Cloning and sequencing the amplified products confirmed that they encode staufen sequences (not shown). The alternatively spliced transcript is therefore present in many mammalian species, and its level of expression is just slightly lower than that of mStau.

mStaui shows impaired dsRNA-binding activity.

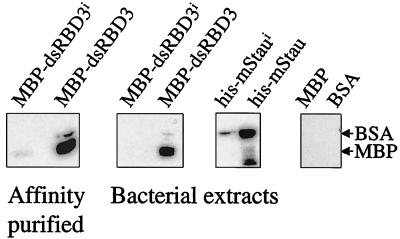

Comparison of the mStaui amino acid sequence with the known nuclear magnetic resonance structure of dsRBD3 of Drosophila Staufen and of other dsRBDs (8, 26) showed that the six-amino-acid insert is localized within the first beta strand of the consensus α-β-β-β-α motif (Fig. 1) (8). To test whether the six-amino-acid insertion modifies the dsRNA-binding capacity of mStaui, fusions of the full-length mStau and mStaui proteins (His-mStau and His-mStaui) and of their isolated dsRBD3s (MBP-dsRBD3 and MBP-dsRBD3i) were expressed in bacteria. Their RNA-binding capacity was analyzed by the Northwestern assay (46). While the MBP-dsRBD3 strongly bound the dsRNA probe, the binding of MBP-dsRBD3i was strongly impaired and detected only after an extended exposure time (Fig. 3). This difference in binding was observed both with the affinity-purified fusion proteins and the bacterial extracts. Impaired binding was also visible with the full-length protein, although the difference was less dramatic (Fig. 3). This can be explained by the presence of dsRBD4, a weak dsRBD that contributes to the dsRNA-binding activity of full-length proteins (46). Finally, under these conditions, the dsRNA probe did not bind other proteins in the bacterial extracts, overexpressed MBP, or BSA (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that the alternative splicing event produces a protein with impaired RNA-binding activity.

FIG. 3.

RNA binding assay. Bacterially expressed dsRBD3 and full-length fusion proteins after affinity purification or in the crude bacterial extracts (as indicated) were electrophoresed on a polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and incubated with 32P-labeled 3′ UTR bicoid RNA. After extensive washing, bound RNA was detected by autoradiography. Controls included bacterial crude extract overexpressing MBP and 5 μg of BSA.

Overexpressed mStaui localizes in discrete RER-containing granules.

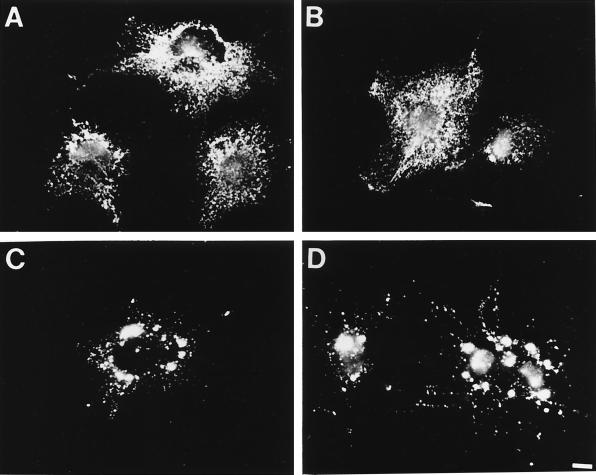

We and others have reported that hStau localizes to the RER (29, 46). To determine the subcellular localization of mStau and mStaui, we constructed fusion proteins with a GFP or HA tag fused to the C-terminal end and transfected these constructs into COS-1 cells. We first observed by Western blotting that the fusion proteins were not degraded and that they were expressed at about the same levels (not shown). Their subcellular distribution was then observed by fluorescence microscopy. As observed for hStau-GFP, mStau-GFP also exhibited a distribution typical of the RER with an abundant tubulovesicular distribution (Fig. 4A). A different distribution was observed when COS-1 cells were transfected with the cDNA coding for mStaui-GFP (Fig. 4C). The protein was found in large clusters throughout the cytoplasm. Treatment of the cells with Triton X-100 prior to fixation did not wash away either the mStau-GFP (Fig. 4B) or mStaui-GFP (Fig. 4D) signal, indicating that both proteins are associated with cytoskeletal elements resistant to the detergent extraction. As reported previously (46), GFP alone showed a diffuse cytoplasmic distribution and was completely extractable by prior treatment with Triton X-100 (not shown). Quantifying the percentage of transfected cells exhibiting a granular or reticular distribution revealed that the vast majority of mStaui-transfected cells showed a granular distribution, while only a minority of mStau-transfected cells exhibited a granular distribution (Table 1). This indicates that overexpressed mStau and mStaui are different in subcellular distribution but that both can exhibit a granular and a reticular ER distribution.

FIG. 4.

Subcellular localization of the mStau and mStaui proteins. COS-1 cells were transfected with cDNAs coding for either mStau-GFP (A and B) or mStaui-GFP (C and D). Untreated cells (A and C) or Triton X-100-treated cells (B and D) were fixed, and GFP autofluorescence was visualized. Bar = 10 μm.

TABLE 1.

Subcellular localization of mStau and mStaui in COS-transfected cells

| Determination | RER distribution (% of transfected cells) | Granular structure (% of transfected cells) |

|---|---|---|

| mStaui overexpression (48 h) | ||

| mStau-transfected cells | 86 | 14 |

| mStaui-transfected cells | 5 | 95 |

| mStaui in mStau/mStaui- transfected cells | 87 | 13 |

| mStaui expression with time (h posttransfection) | ||

| 10 | 68 | 32 |

| 16 | 45 | 55 |

| 24 | 31 | 69 |

| 36 | 17 | 83 |

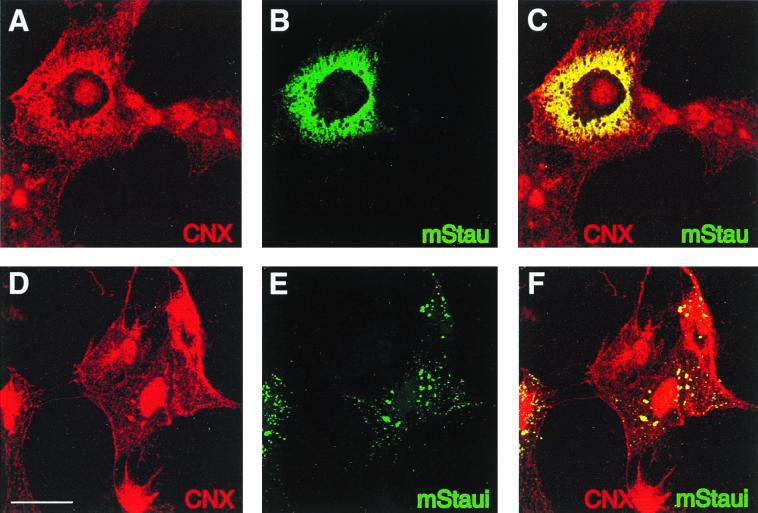

As described earlier for hStau (46), confocal microscopy showed that mStau-GFP colocalizes with calnexin, an RER marker (Fig. 5A to C). In contrast, the granular labeling by mStaui-GFP is distinct from the reticular and tubulovesicular labeling of the ER by calnexin. Interestingly, the mStaui-containing granules also colocalized with calnexin (Fig. 5D to F). We conclude that the six-amino-acid insertion in mStaui induces a distinct distribution of the overexpressed protein compared to mStau, although it apparently does not completely impair its ability to interact with the ER.

FIG. 5.

Colocalization of mStau and mStaui with markers of the RER by confocal microscopy. cDNAs coding for mStau-GFP (A to C) and for mStaui-GFP (D to F) fusion proteins were transfected into COS-1 cells. Triton X-100-treated cells were fixed and labeled with anticalnexin (A and D). GFP was detected by autofluorescence using the FITC channel (B and E), whereas anticalnexin was detected with Texas red-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies using the rhodamine channel. C and F are superpositions of A and B and D and E, respectively. mStau colocalizes with calnexin (CNX)-labeled ER, and calnexin is associated with mStaui-labeled granules. Cells expressing mStaui-GFP, but not labeled with anticalnexin antibodies, and untransfected cells labeled for calnexin did not present a signal in the rhodamine and in the fluorescein channel, respectively, showing that the observed signals are specific. Bar = 10 μm.

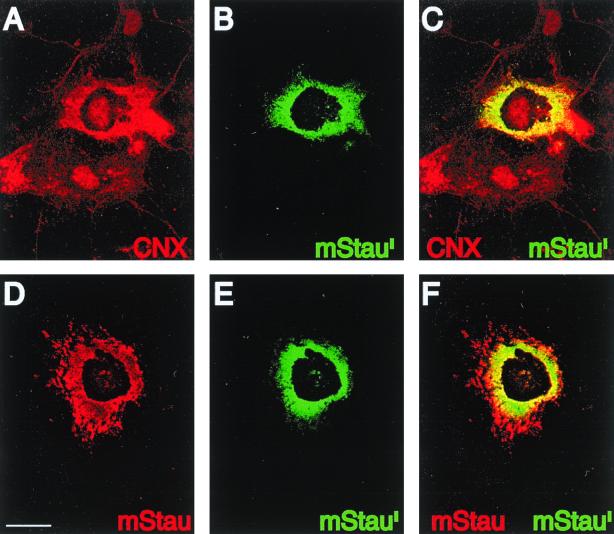

Since the mStaui and mStau isoforms are endogenously expressed in COS-1 cells, it is possible that the phenotype of cells overexpressing mStaui is due to an imbalance in the ratio of the two isoforms. To address this possibility, we first observed mStaui-transfected cells shortly after transfection in order to monitor mStaui distribution when minimal amounts of the protein are expressed. In these conditions, mStaui exhibited a tubulovesicular distribution typical of the RER in most of the cells; however, as mStaui accumulated in the cells with time, the percentage of cells exhibiting the granular distribution increased (Table 1). We also cotransfected COS-1 cells with mStau-HA and mStaui-GFP constructs and monitored the subcellular distribution of mStaui-GFP (Fig. 6). Determined by its colocalization with calnexin (Fig. 6A to C), coexpression of the two isoforms resulted in the absence of densely labeled granules and in the relocalization of mStaui-GFP to the reticular RER (Fig. 6A and Table 1). Interestingly, compared to the distribution of cotransfected mStau, mStaui seemed to be mostly distributed in the perinuclear RER and absent from the cell periphery (Fig. 6D to F). These results demonstrate that mStaui normally associates with the reticular RER, suggesting that this association requires interaction with mStau.

FIG. 6.

Rescue of mStaui phenotype by coexpression of mStau. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with cDNAs coding for mStaui-GFP and mStau-HA fusion proteins. Triton X-100-treated cells were fixed and labeled with anti-calnexin (A) or anti-HA (D) antibodies. mStaui-GFP was detected by autofluorescence using the FITC channel (B and E), whereas anticalnexin and anti-HA were detected with Texas red-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies using the rhodamine channel. C and F are superpositions of A and B and D and E, respectively. Controls (as described in the legend to Fig. 5) demonstrated that the observed signals are specific. Bar = 10 μm.

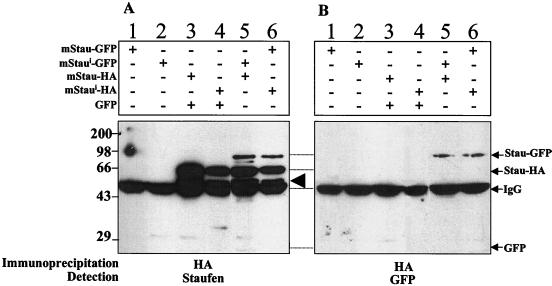

mStaui is part of a multiple-isoform complex.

To determine whether mStau and mStaui are present in the same complexes, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays from cells cotransfected with mStau and mStaui. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with mStau-HA and mStaui-GFP, and protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. The immunoprecipitated proteins were visualized by Western blotting using anti-hStau (Fig. 7A) and anti-GFP (Fig. 7B) antibodies. mStaui-GFP was present in the immunoprecipitated mStau-HA pellets, demonstrating that the two proteins are components of a common complex (lane 5). Symmetrical results were obtained when the tags on the proteins were interchanged: mStau-GFP was also detected in immunoprecipitates of mStaui-HA (lane 6). The controls that included the transfection of COS-1 cells with either mStau-GFP alone (lanes 1 and 2) or cotransfection of mStau-HA with GFP (lanes 3 and 4) were uniformly negative. The equal level of expression of each protein in the loading extracts was confirmed with anti-Staufen and anti-GFP antibodies on Western blots (not shown). Interestingly, a 55-kDa protein band corresponding to the size of the endogenous Staufen protein also coprecipitated with mStau-HA and mStaui-HA. That the mStau fusion proteins are localized with the endogenous protein is particularly significant. These results demonstrate that the two isoforms are components of the same complexes in vivo.

FIG. 7.

mStau isoforms are present in the same complexes. Coimmunoprecipitation assay. Different combinations of tagged-Staufen isoforms were expressed in COS-1 cells as indicated above the gels. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, and the proteins were revealed by Western blotting using anti-hStau (A) and anti-GFP (B) antibodies. The positions of mStau/mStaui-GFP (Stau-GFP), mStau/mStaui-HA (Stau-HA), IgG, and GFP are indicated on the right. Numbers on the left are protein molecular weight markers in kilodaltons. The large arrowhead represents the position of the endogenous 55-kDa Staufen isoform.

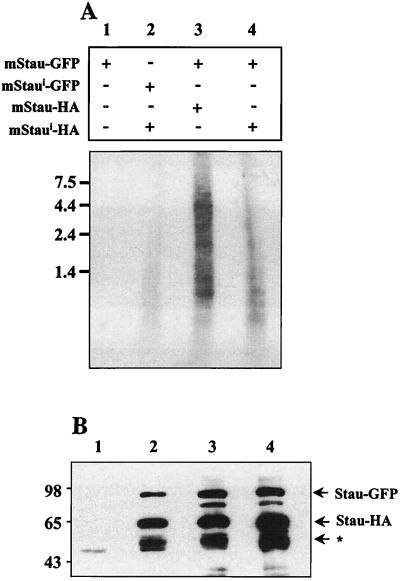

mStaui modulates the amount of RNA in mStau-containing complexes.

The reduced capacity of mStaui to bind RNAs and its ability to associate with mStau in vivo suggest that mStaui could modulate the RNA-binding activity of the complexes and thus regulate the amount of RNA associated with it. To test this hypothesis, we transfected COS-1 cells with different amounts of the two isoforms, immunoprecipitated HA-tagged complexes, and analyzed the RNA content of the resulting precipitates (Fig. 8A). Multiple RNA bands were easily visible when immunoprecipitation was done from mStau-HA/mStau-GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 8A, lane 3). In contrast, a significant reduction in the amount of RNAs was attained when immunoprecipitated RNAs from the mStaui-HA/mStau-GFP-transfected cells were analyzed (lane 4). This reduction was even more striking in the mStaui-HA/mStaui-GFP immunoprecipitates (lane 2). Western analysis of the amount of the immunoprecipitated proteins showed that the difference in the quantity of RNA cannot be due to less efficient immunoprecipitation of mStaui-containing complexes (Fig. 8B). This experiment was repeated three more times with the same results. We conclude that mStau is a component of complexes containing RNAs and that mStaui incorporation in these complexes modulates the amounts of associated RNA.

FIG. 8.

Expression of mStaui modulates the amount of RNAs in Staufen-containing particles. COS-1 cells were transfected with different combinations of the two Staufen isoforms as indicated above the gel, and the proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. RNAs were purified and separated on formaldehyde-agarose gels and analyzed by hybridization using 32P-labeled random oligonucleotides (A). (B) Proteins from the same immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting using anti-Staufen antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Despite an increasing number of reports describing mRNA transport, only recently have the first trans-acting proteins in mammals been identified. Their functions, molecular characteristics, interacting partners, and regulation remain largely unknown. Staufen is known to bind dsRNA, to associate with polysomes, the RER, and elements of the cytoskeleton, and to be expressed as multiple isoforms in mammalian cells. However, it was unclear how these molecular and cellular characteristics are integrated to fulfill and regulate all Staufen functions. In this paper, we report the following: (i) the characterization of a novel Staufen isoform with impaired RNA-binding properties; (ii) that dsRBD3 is involved not only in RNA binding but also in the proper localization on the RER; (iii) that Staufen isoforms are components of a common RNA-protein complex in vivo; and (iv) that the ratio of mStau and mStaui modulates the amount of RNA present in the complex.

mStaui modulates the RNA content of the Stau complexes.

This study provides the first biochemical evidence that Staufen is a component of RNA-protein complexes. The immunoprecipitation experiment demonstrates that mStau complexes contain a limited number of RNAs. This corroborates previous in vivo results that showed that Staufen-containing particles colocalized with RNA-containing granules (19, 25). This is also consistent with a putative role for mammalian Staufen in mRNA transport and localization and suggests that if Staufen plays additional roles in mammals, this role is likely to be related at least to some aspect of RNA processing. In Drosophila, genetic evidence suggests that Staufen may also be involved in the regulation of translation of localized RNAs (5).

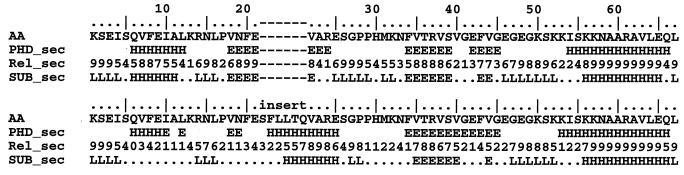

The biochemical properties of mStaui are different from those of the other mouse Staufen isoforms at least at the level of the RNA-binding activity. Analysis of the amino acid sequence of dsRBD3i with the PHD software (37) shows that the insertion of the fragment SFLLTQ in the first beta strand results in major conformational changes within the whole region (Fig. 9). First, the insertion disturbs the alternate order of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues, which is crucial for the proper accommodation of the beta strand in the rest of the domain. Moreover, the three inserted hydrophobic residues (FLL) become part of a long α-helical cluster, which will force the whole region to accept the helical conformation. Accordingly, the secondary structure of dsRBD3i is predicted to yield an α helix characterized by a very high index of reliability. Thus, the insertion of six amino acids will probably result in a switch to an essentially different folding of the domain. We show here that it weakens the capacity of dsRBD3 to bind RNA in vitro. Further careful tests should show whether the insertion also changes the RNA recognition of mStaui, leading to a different dsRNA-binding specificity. Identification of the isolated RNAs should resolve this issue.

FIG. 9.

Effect of the SFLLTQ insertion on the structure of mStaui. (Top) The α-helical surface of the mStaui region that includes the insertion. The six inserted residues are shown in fancy letters. Enclosed in large circles, the three inserted residues FLL plus residues F20, V22, and A23 form a wide hydrophobic cluster that can effect the secondary structure of the whole region. (Bottom) Prediction of the secondary structure for mStau (upper part) and mStaui (lower part) with use of the PHD software package. AA, amino acid sequence. PHD_sec (predicted secondary structure): H, helix; E, extended (sheet); blank, other (loop). Rel_sec, reliability index for the PHD_sec prediction (0 = low to 9 = high); Sub_sec, subset of the PHD_sec predictions, for all residues with an expected average accuracy >82%. The insertion of the six amino acids between residues 21 and 22 changes the secondary structure of the whole region from β structure to α helix.

At least two scenarios are possible to explain how overexpression of mStaui contributes to reducing the RNA content of Staufen RNA-protein complexes. It is conceivable that mStau and mStaui form heterodimers that are less functional than mStau homodimers for binding RNA. Members of the dsRBD family have been shown to form homo- and heterodimers (4, 9, 38). RNA-dependent kinase activity is indeed dependent on dimer formation. Its activity can be regulated by the formation of inactive heterodimers, due to mutation in one of the monomers (35). Rescue of the mStaui phenotype by mStau and coimmunoprecipitation experiments showing that the two isoforms are present in the same complex are consistent with the hypothesis that they form heterodimers. Furthermore, preliminary pull-down assays suggest that Staufen interacts with itself in vitro (our unpublished data). Another possibility is that mStaui competes with mStau for a limited number of binding sites within RNA-protein complexes. Since mStaui binds RNA less efficiently than mStau, its incorporation in mStau complexes would also reduce the amount of RNA associated with the complex.

mStaui and the RER.

The localization of mStaui to cytoplasmic granules is likely a consequence of the overexpression of mStaui: these structures are not observed endogenously and are visible in a low percentage of mStau-transfected cells. However, the rescue experiment shows that the formation of granules is due not to the overexpression of mStaui per se but rather to an imbalance in the ratio of the two isoforms and that under normal conditions, mStaui is associated with the reticular RER. One plausible explanation is that mStaui cannot be properly localized independent of mStau, with which it associates in vivo. Can its normal distribution to reticular RER occur only in this form? This would suggest that mStaui is likely a regulator of mStau function, as shown here for RNA incorporation in the mStau complexes. Interestingly, tendon cell differentiation in Drosophila was shown to be modulated by the balance between two isoforms of the RBP How (31). It is likely that the granular mStaui phenotype is due to the structural modification of dsRBD3 or to its reduced RNA-binding activity. The formation of similar granules following overexpression of a mutant with a point mutation that completely abolishes the dsRBD3 RNA-binding activity, but not the structure of the domain, is consistent with the second hypothesis (M. Luo and L. DesGroseillers, unpublished data).

The observation that in contrast to mStau, mStaui is restricted to the perinuclear region and absent from the cell periphery suggests that the differential capability of Staufen isoforms to interact with RNA ligands is somehow involved in recognizing or regulating RER compartmentalization. Alternatively, since transport of RNP complexes was shown to be RNA dependent in Drosophila, complexes containing mStaui may be unable to integrate the signal required for transport of the RNPs and association with RER tubulovesicles. One consequence of this hypothesis is that RER dynamics might be somehow coupled to RNA transport. The formation of static ER subdomains appearing as large clusters or granule-like structures when mStaui is overexpressed supports this view. Therefore, under normal conditions, one of the functions of mStaui could be to regulate the transport of Staufen-containing granules.

In summary, our results show that mStaui is present in complexes that also contain mStau and that the presence of mStaui drastically reduces the ability of the complex to associate with RNA, suggesting that it has a role as a regulator of mStau function. Demonstration of this putative regulatory role is not an easy task because mStau is poorly soluble in vitro and no specific RNA-binding activity or endogenous RNA ligands have so far been described. However, our report, which describes the identification of the isolated RNAs and the use of the RNA immunoprecipitation assay to detect RNA candidates, will facilitate further study of endogenous RNA targets. We believe that this is the key to understanding the function if mStau isoforms in vivo. Our results present an important step in the study of regulation of mRNA transport and localization in mammals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Kiebler and Gopal Subramaniam for critical reading of the manuscript, Judith Kashul for editing the manuscript, Frédéric Brizard for sharing unpublished data, Louise Cournoyer for help with tissue culture, and Danny Baranes for help with confocal microscopy. We also thank Michael Kiebler and Kavish Hemraj for help and support.

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant to L.D. and a Medical Research Council of Canada grant to I.R.N. S.V.S. is a fellow of le Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec. T.D. was supported by an NSERC studentship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainger K, Avossa D, Morgan F, Hill S J, Barry C, Barbarese E, Carson J H. Transport and localisation of exogenous myelin basic protein mRNA microinjected into oligodendrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:431–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassell G J, Singer R H. mRNA and cytoskeletal filaments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassell G J, Zhang H, Byrd A L, Femino A M, Singer R H, Taneja K L, Lifshitz L M, Herman I M, Kosik K S. Sorting of beta-actin mRNA and protein to neurites and growth cones in culture. J Neurosci. 1998;18:251–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benkirane M, Neuvent C, Chun R F, Smith S M, Samuel C E, Gatignol A, Jeang K-T. Oncogenic potential of TAR RNA binding protein TRBP and its regulatory interaction with RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. EMBO J. 1997;16:611–624. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitwieser W, Markussen F-H, Horstmann H, Ephrussi A. Oskar protein interaction with Vasa represents an essential step in polar granule assembly. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2179–2188. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brizard, F., M. Luo, and L. DesGroseillers. Genomic organization of the human and mouse stau genes. DNA Cell Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Broadus J, Fuerstenberg S, Doe C Q. Staufen-dependent localisation of prospero mRNA contributes to neuroblast daughter-cell fate. Nature. 1998;391:792–795. doi: 10.1038/35861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bycroft M, Grunert S, Murzin A G, Proctor M, St. Johnston D. NMR solution structure of a dsRNA binding domain from Drosophila staufen protein reveals homology to the N-terminal domain of ribosomal protein S5. EMBO J. 1995;14:3563–3571. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosentino G P, Venkatesan S, Serluca F C, Green S, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N. Double-stranded-RNA-dependent protein kinase and TAR RNA-binding protein form homo- and heterodimers in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9445–9449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshler J O, Highett M I, Schnapp B J. Localisation of Xenopus Vg1 mRNA by Vera protein and the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1997;276:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshler J O, Highett M I, Abramson T, Schnapp B J. A highly conserved RNA-binding protein for cytoplasmic localisation in vertebrates. Curr Biol. 1998;8:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etkin L D, Lipshitz H D. RNA localisation. FASEB J. 1999;13:419–20. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrandon D, Elphick L, Nüsslein-Volhard C, St. Johnston D. Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell. 1994;79:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrandon D, Koch I, Westhof E, Nüsslein-Volhard C. RNA-RNA interaction is required for the formation of specific bicoid mRNA 3′ UTR-staufen ribonucleoprotein particles. EMBO J. 1997;16:1751–1758. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunkel N, Yano T, Markussen F H, Olsen L C, Ephrussi A. Localisation-dependent translation requires a functional interaction between the 5′ and 3′ ends of oskar mRNA. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1652–1664. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Havin L, Git A, Elisha Z, Obeerman F, Yaniv K, Schwartz S P, Standart N, Yisraeli J K. RNA-binding protein conserved in both microtubule- and microfilament-based RNA localisation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1593–1598. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoek K S, Kidd G J, Carson J H, Smith R. hnRNP A2 selectively binds the cytoplasmic transport sequence of myelin basic protein mRNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7021–7029. doi: 10.1021/bi9800247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jockers R, Da Silva A, Strosberg A D, Bouvier M, Marullo S. New molecular and structural determinants involved in β2-adrenergic receptor desensitization and sequestration. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9355–9362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiebler M A, Hemraj I, Verkade P, Kohrmann M, Fortes P, Marion R M, Ortin J, Dotti C G. The mammalian staufen protein localizes to the somatodendritic domain of cultured hippocampal neurons: implications for its involvement in mRNA transport. J Neurosci. 1999;19:288–297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00288.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiebler M A, DesGroseillers L. Molecular insights into mRNA transport and local translation in the mammalian nervous system. Neuron. 2000;25:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim-Ha J, Smith J L, Macdonald P M. Oskar mRNA is localised to the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Cell. 1991;66:23–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90136-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim-Ha J, Kerr K, Macdonald P M. Translational regulation of oskar mRNA by Bruno, an ovarian RNA-binding protein, is essential. Cell. 1995;81:403–412. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kislauskis E H, Zhu X, Singer R H. β-actin messenger RNA localisation and protein synthesis augment cell motility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1263–1270. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles R B, Sabry J H, Martone M E, Deerinck T J, Ellisman M H, Bassell G J, Kosik K S. Translocation of RNA granules in living neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7812–7820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07812.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köhrmann M, Luo M, Kaether C, DesGroseillers L, Dotti C G, Kiebler M A. Microtubule-dependent recruitment of Staufen-green fluorescent protein into large RNA-containing granules and subsequent dendritic transport in living hippocampal neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2945–2953. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.9.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krovat B C, Jantsch M F. Comparative mutational analysis of the double-stranded RNA binding domains of Xenopus laevis RNA-binding protein A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28112–28119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Yang X, Wasser M, Cai Y, Chia W. Inscutable and staufen mediate asymmetric localisation and segregation of prospero RNA during Drosophila neuroblast cell divisions. Cell. 1997;90:437–447. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long R M, Singer R H, Meng X, Gonzalez I, Nasmyth K, Jansen R-P. Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localisation of ASH1 mRNA. Science. 1997;177:383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mariòn R M, Fortes P, Beloso A, Dotti C, Ortin J. A human sequence homologue of Staufen is an RNA-binding protein that is associated with polysomes and localizes to the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2212–2219. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin K C, Casadio A, Zhu H, Yaping E, Rose J C, Chen M, Bailey C H, Kandel E R. Synapse-specific, long-term facilitation of Aplysia sensory to motor synapses: a function for local protein synthesis in memory storage. Cell. 1997;91:927–938. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabel-Rosen H, Dorevitch N, Reuveny A, Volk T. The balance between two isoforms of the Drosophila RNA-binding protein how controls tendon cell differentiation. Mol Cell. 1999;4:573–584. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakielny S, Fischer U, Michael W M, Dreyfuss G. RNA transport. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:269–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norvell A, Kelley R L, Wehr K, Schupbach T. Specific isoforms of squid, a Drosophila hnRNP, perform distinct roles in Gurken localisation during oogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:864–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pokrywka N J, Stephenson E C. Microtubules are a general component of mRNA localisation systems in Drosophila oocytes. Dev Biol. 1995;167:363–370. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano P T, Green S R, Barber G N, Mathews M B, Hinnebusch A G. Structural requirements for the double-stranded RNA binding, dimerization, and activation of the human eiF-2α kinase DAI in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:365–378. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross A F, Oleynikov Y, Kisllauskis E H, Taneja K L, Singer R H. Characterization of a beta-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2158–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein structure at better than 70% accuracy. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmedt C, Green S R, Manche L, Taylor D R, Ma Y, Mathews M B. Functional characterization of the RNA-binding domain and motif of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase DAI (PKR) J Mol Biol. 1995;249:29–44. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuldt A J, Adams J H, Davidson C M, Micklem D R, Haseloff J, St. Johnston D, Brand A H. Miranda mediates asymmetric protein and RNA localisation in the developing nervous system. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1847–1857. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steward O. mRNA localisation in neurons: a multipurpose mechanism? Neuron. 1997;18:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.St. Johnston D, Driever W, Berleth T, Richstein S, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Multiple steps in the localisation of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Dev Suppl. 1989;107:13–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.Supplement.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.St. Johnston D, Beuchle D, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Staufen, a gene required to localize maternal RNAs in the Drosophila egg. Cell. 1991;66:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90138-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.St. Johnston D, Brown N H, Gall J G, Jantsch M. A conserved double-stranded RNA-binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10979–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.St. Johnston D. The intracellular localisation of messenger RNAs. Cell. 1995;81:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takizawa P A, Sil A, Swedlow J R, Herskowitz I, Vale R D. Actin-dependent localisation of an RNA encoding a cell-fate determinant in yeast. Nature. 1997;389:90–93. doi: 10.1038/38015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wickham L, Duchaine T, Luo M, Nabi I R, DesGroseillers L. Mammalian staufen is a double-stranded-RNA- and tubulin-binding protein which localizes to the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2220–2230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilhelm J E, Vale R D. RNA on the move: the mRNA localisation pathway. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:269–274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]