Abstract

The structural changes in the tissues of the osteochondral junction are a topic of interest, especially considering how bone changes are involved in the initiation and progression of osteoarthritis (OA). Our research group has previously demonstrated that at the cement line boundary between the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC) and the subchondral bone, in mature bovine patellae with early OA, there are numerous bone spicules that have emerged from the underlying bone. These spicules contain a central vascular canal and a bone cuff. In this study, we use high‐resolution differential interference contrast optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy to compare the cartilage–bone junction of three groups of mature bovine patellae showing healthy to mild to moderately degenerate cartilage. The ZCC and bone junction was carefully examined to estimate the frequency of marrow spaces, bone spicules and fully formed bone bulges. The results reveal that bone spicules are associated with all grades of cartilage tissue studied, with the most occurring in the intermediate stages of tissue health. The micro and ultrastructure of the bone spicule are consistent with that of an osteon, especially those found in compression zones in long bones. Also considering the coexistence of marrow spaces and fully formed bone, this study suggests that these bone spicules arise similar to the formation of osteons in the bone remodelling process. The significance of this conclusion is in the way researchers approach the bone formation issue in the early degenerative joint. Instead of endochondral ossification, we propose that bone formation in OA is more akin to a combination of primary bone remodelling and de novo bone formation.

Keywords: articular cartilage, bovine patella model, calcified cartilage, early osteoarthritis, primary bone healing

How bone develops in an aging joint. The micro anatomy of a bone spicule in the zone of calcified cartilage in the cartilage‐bone junction.

1. INTRODUCTION

Articular cartilage is an aneural and avascular tissue designed to protect the underlying bone, facilitate high weight‐bearing and provide an ultra low‐friction contact for non‐deleterious joint articulation. The physical connection of cartilage to bone is via a transition, where the very deep layers of cartilage are mineralised as it attaches to the hard bone proper. In mature animals, the immediate bone at this junction consists of a corticalised subchondral bone plate (SBP) with varying but small‐sized porosity relative to the underlying trabecular bone with its consistent and larger marrow spaces. The bulk of the articular cartilage is unmineralised but as mentioned above, the cartilage transition to bone is mineralised and this region is called the ‘zone of calcified cartilage’ (ZCC). The ZCC thickness is approximately 5% of the total cartilage thickness (Oegema et al., 1997) and is measured from its boundary to the unmineralised cartilage (tidemark) to that with the bone boundary (cement line). The line profile of the tidemark is relatively congruent to the articular cartilage surface, while the cement line is irregular. This irregularity increases with osteoarthritic histopathological grade (Finnilä et al., 2017). That the underlying bone in osteoarthritic joints undergo structural changes is known (Buckwalter & Mankin, 1998) and contributes to the intriguing ‘bone‐first’ hypothesis for osteoarthritis (OA). It was proposed that changes in bone precede that of the overlying cartilage in the joint degenerative process (Burr & Gallant, 2012), or that OA would only develop if the bone was also involved in an initiating event (Buckwalter & Brown, 2004; Lories & Luyten, 2011). An initiating event studied extensively was mechanical overload. Radin and colleagues described subchondral bone thickening, a result of bone remodelling following damage to the trabeculae, as the cause of stress risers in the joint tissues that then caused the mechanical destruction of the overlying articular cartilage (Burr & Radin, 2003; Radin & Rose, 1986; Radin et al., 1970, 1973, 1991).

However, this interpretation that subchondral bone changes lead to OA was limited. It presented a largely macro‐mechanical viewpoint of how OA eventuated. The mechanism did not distinguish essential differences between the ZCC, subchondral plate and the underlying subchondral trabecular bone. Animal experiments have shown that excessive loading and trabecular bone changes did not lead to OA even after 34 weeks (Wu et al., 1990). The conclusion is that the stiffening in this region was too far away and hence non‐consequential to the overlying cartilage (Burr & Radin, 2003). The ‘bone‐first’ hypothesis for OA initiation was thus reconsidered and modified. Instead, it was suggested that the role of subchondral microcracks in the SBP was a more promising lead to pursue (Burr & Radin, 2003). Importantly, the revised hypothesis included a biological emphasis, where it was proposed that load‐induced microcracks in the subchondral bone (Burr & Schaffler, 1997) or calcified cartilage (Mori et al., 1993; Sokoloff, 1993) triggered the reactivation of the secondary ossification centre. This reactivation was then believed to initiate an endochondral ossification, which structurally transformed the joint and began the mechanically driven OA process (Burr & Radin, 2003). Indeed, studies have found how microdamage in bone can trigger a bone remodelling response (Verborgt et al., 2000). In OA joints, the presence of accumulated microcracks in the SBP has been shown to be associated with bone remodelling phenotypes such as bone marrow lesions (Muratovic et al., 2018). Of interest is the corresponding subchondral bone response, where SBP thickening has been associated with BMLs (Muratovic et al., 2018). The thickening of the SBP indicates bone formation.

In OA joints, studies have shown that there is a ‘massive’ increase of bone volume in the SBP, that is thickening, along with an increased number of pores or holes in the SBP (Aho et al., 2017). Such holes in the SBP were reported earlier (Clark & Huber, 1990) and shown to range in size from 100 µm to 300 µm. Associated with porosity in the SBP were an increased cement line irregularity and bone protrusions, wherein these protrusions were vascular tissue (Aho et al., 2017). Such bone protrusions emerging from the SBP boundary or cement line and entering the ZCC have been called ‘bone spicules’ in studies investigating the osteochondral junction of bovine patellae with early cartilage degeneration (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013; Thambyah & Broom, 2009). These bone spicules, described as bone protrusions with a vascular channel (Thambyah & Broom, 2009), are arguably the same thing as vascular channels with a bone cuff (Clark, 1990; Suri & Walsh, 2012). However, the difference is in the proposed consequence. The bone spicules have been suggested to be indicators of bone development such that the cement line advances and the SBP thickens (Thambyah & Broom, 2009). The vascular channels have been suggested to be indicators of an invasion of articular cartilage by blood vessels, increasing molecular cartilage‐bone crosstalk and advancing endochondral ossification (Suri & Walsh, 2012). The theory on the reactivation of endochondral ossification is also largely based on the assumption that the advancement of the tidemark in OA joints reflects progressive calcification of the cartilage (Mahjoub et al., 2012). However, on the other hand, there are also strong indicators that the bone changes in OA are in response to damage and mechanical loading (Baker‐LePain & Lane, 2012; Madry et al., 2010), and that the response is similar to new bone formation (Madry et al., 2010), with osteoclast‐mediated remodelling (Coughlin & Kennedy, 2016). Thus, the microstructural changes in the subchondral bone in OA are not fully understood. Concerning the existence of bone spicules or vascular channels, suggestions on their origins include ‘microdamage repair, angiogenic factors and enhanced bone‐cartilage crosstalk via increased subchondral plate pores’ (Li et al., 2013).

The present study aims to provide more understanding into the cement line changes in early joint degeneration by investigating the microanatomy of the bone spicules. With the use of the validated bovine model of early OA (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013), the present study is provided with a virtually limitless supply of tissue containing a consistent number of bone spicules for the investigation. The anatomy of bone spicules or vascularity, called ‘defects’ (Woods et al., 1970), has been studied in many ways. Still, we believe that this is the first study to provide micro and ultrastructural detail that we hope will contribute to insight into how these subchondral changes take shape and develop in early OA.

2. METHODS

From a local abattoir, 49 patellae from mature cows, aged between 6 and 9 years, were obtained and stored at −20°C. Over the last 15 years, the senior author has published data obtained from testing bovine patellae cartilage, obtained from the same abattoir (e.g. Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013; Thambyah & Broom, 2009). These patellae display a range of cartilage states from healthy to moderate degeneration, where there were either none, some or more severe surface disruption as determined by India ink staining (Figure 1). Osteochondral blocks were dissected from the distal‐lateral region of each patella, where if there were to be cartilage surface disruption, it has been found previously to occur in this region (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013; Thambyah & Broom, 2009). The blocks were prepared for differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, for which they were fixed in 10% formalin for a minimum of 2 days and decalcified in 10% formic acid for 2 days. Blocks were then snap‐frozen with liquid nitrogen and cryosectioned to create 30‐µm‐thick sagittal plane sections. Sections were wet mounted in saline, thus fully hydrated, and cover slipped onto slides for examination with DIC microscopy. The osteochondral junction was imaged at 10× magnification along ~12 mm of section. Using Photoshop CS5, the images were merged to create a high‐resolution image of the osteochondral junction that was used for spicule analysis (Figure 1). An additional six patellae obtained from the same abattoir, showing very mild Indian ink staining, were also used to obtain blocks for transverse plane sectioning into the ZCC.

FIGURE 1.

Macroscopic scoring of cartilage degeneration. En‐face view of cartilage stained with India ink to show fibrillation. (a) Normal (G0), (b) cartilage softening and swelling (G1), (c) cartilage fissuring in a small lesion (G2). Dotted lines indicate the axis of the microtomed sagittal sections into the plane of the picture. On the right are representative images of full thickness differential interference contrast fully hydrated cartilage‐on‐bone microsections sampled from a to c type patellae. Scale bar for micro‐images, 1 mm

Along the length of the osteochondral image, the cement line and its irregularity were inspected. The irregularities were classified as defects in the subchondral bone‐front (terminology used by Woods et al., 1970), where three types were defined (Figure 2). These were either (A) a vascular or marrow space without a bone cuff, (B) a well‐defined bone spicule where there is a bone cuff with a central canal and (C) bone ‘bulges’ from the subchondral bone cement line that does not show a central canal. Each bone spicule was measured for its length (from the surrounding cement line to its apex), angle from the right‐hand cement line, maximum width along its length and maximum canal diameter (Figure 3). After high‐resolution osteochondral images were created with DIC microscopy, a selected number of the same sections were prepared for scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Sections were defatted in hexane and dehydrated through a series of ethanol concentrations from 50% to 100%. The sections were then critical point dried and mounted onto SEM stubs with adhesive discs. Stubs were double coated with platinum for viewing with a Philips XL30S Scanning electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 5.0 kV.

FIGURE 2.

Three types of defects along the irregularity of the bone cement line were characterised for this study. The black arrow indicates the upper‐most tidemark defining the boundary between the uncalcified cartilage and the calcified cartilage. The scale bars are about 200 µm

FIGURE 3.

For those defects identified as bone spicules, measurements were made of the length of the spicule from the tip to the cement line (green), the width of the central canal (red), the widest diameter of the bone cuff (blue) and the angle or orientation of the spicule relative an assumed horizontal of the cement line (yellow)

A second tissue block from each patella was processed for histology by fixing in 10% formalin, decalcifying in 10% formic acid for at least 4 weeks, dehydrating in graded concentrations of ethanol, embedding in paraffin wax and microtoming to 5 µm sections. These sections were stained with Safranin‐O and fast green and graded using the key feature grading from the OARSI system (Waldstein et al., 2016).

Data were analysed using one‐way ANOVA tests between degenerative groups. Pearson's chi‐square test was used to compare proportions between groups. Significance was set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

3. RESULTS

From the microsections and staining assessment, samples were divided into three groups based on their DIC microscopy images and OARSI grading (Figure 4). The OARSI grades correlated strongly with the original India ink staining of the patella, confirming the findings of our earlier study that established the bovine patellae as a suitable model for early OA cartilage degeneration (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013). In total, there were 22 patellae in the G0 (intact) group showing an intact cartilage surface, 4 patellae in the G1 (mild degeneration) group with mild disruption of the cartilage surface and 23 patellae in the G2 (moderate degeneration) group with fragmentation and fissuring (see Figure 1). Microscopic DIC investigation of the osteochondral junction of the 49 patellae yielded a total of 2128 defects for analysis, for which the morphometry data are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. The vast majority of defects were Type B, in which the mean orientation (refer to Figure 3) was 90°. The orientations, when plotted in a frequency graph, showed a normal distribution (Pearson's chi‐square test p‐value = 0.0000) with the mean centralised around 90°.

FIGURE 4.

OARSI (histology) grades versus India ink grades, for the samples used in this study. Grade 0 (n = 22) was classified as healthy and intact, G1 (n = 4) was classified as mildly degenerate and G2 (n = 23) was defined as moderately degenerate

TABLE 1.

Contingency table of the frequencies of each type of defect with degenerative grade

| A | B | C | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 |

137 13.6% |

756 75.3% |

111 11.1% |

1004 100% |

| G1 |

8 4.0% |

170 84.2% |

24 11.9% |

202 100% |

| G2 |

45 4.9% |

708 76.8% |

169 18.3% |

922 100% |

| Total |

190 8.9% |

1634 76.8% |

304 14.3% |

2128 |

TABLE 2.

The mean and standard deviation dimensions for the 1634 Type B—bone spicule defects (mean ± standard error of the mean)

| Bone spicules | Proportion | Length (µm) | Outer diameter (µm) | Canal diameter (µm) | Orientation (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1634) | 76.8% | 152 ± 1.4 | 95.9 ± 0.8 | 24.1 ± 0.4 | 90.4 ± 0.6 |

The three types of defects A, B and C, each showed different prevalence. Type B was the most common defect with 77% of all defects displaying the typical bone spicule morphology with the bone cuff and central canal (Figure 5). Type A defects were the least prevalent with only 9%. Type A defects had much larger vascular spaces than Type B. Type C defects, which contain no visible central canal, were significantly shorter in length than both A and B types. Defect frequency (including all three types) averaged 3.7 ± 0.1 per mm length of section with no difference between degenerative groups. The proportion of the types of defects was significantly different between groups; the proportion of type A defects significantly decreased from G0 to G1 and G2 groups (p = 0.006) but the proportions of types B and C did not change between groups (p = 0.368 and p = 0.098, respectively).

FIGURE 5.

Example of bone spicules as imaged using differential interference contrast from two different samples: (a) intact sample and (b) mildly degenerate. Note the bone cuff around a spicule (white arrow) and the multiple mineralisation fronts (black arrows). Circled are examples of osteocyte lacunae. Scale bar 100 µm

The focus of this study was on the bone spicules and hence the Type B defect was analysed further (Table 2). The average length of bone spicules was 152 µm and with the outer diameter being 96 µm and canal diameter being 24 µm, implied that the bone cuff size was about 35 µm thick on either side of the canal (see Figures 5 and 6). The extent to which these spicules were oriented towards the articular surface was such that they were mostly around 90° in their long axis.

FIGURE 6.

A transverse section cut across the plane of the ZCC. The schematic shows how such a cut, because of the uneven bone cement line, results in revealing a gradually deeper view from the ZCC to the underlying bone. The section here thus shows the ZCC region on the left and the underlying bone on the right. Thus, the white arrows show relatively the tips of the spicules, whereas the black arrows point to some of the spicules that have been sectioned closer to the base and thus blends with the surrounding subchondral bone. The dotted arrow points to a canal that traverses across the plane, and such ‘transverse connectivity’ in terms of the canal network was found to be fairly widespread. Scale bar 100 µm. ZCC, zone of calcified cartilage

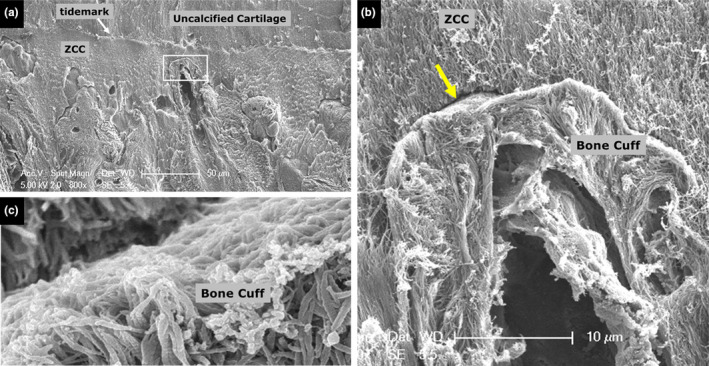

The consistency in the cross‐sectional shape of the canal diameter, being almost circular, was noted (Figure 7). SEM imaging of the bone spicules provides a high‐resolution view of the bone cuff with respect to the ZCC (Figure 8), showing several distinct structural discontinuities, from the canal, the layers of bone in terms of fibre direction. The boundary between the bone cuff and the ZCC reveals that there is a relatively minimal amount of ‘fibrillar connection’ (Figures 9, 10, 11). The samples had been decalcified and defatted and hence, where ‘there was’ an inorganic (cement) phase, following decalcification is now left with an empty space or ‘gap’ (see arrow in Figures 10a and 11b,c).

FIGURE 7.

(a) High‐resolution image, from a transverse section, of two spicules. While canal 1 is orthogonal to the plane of the section, canal 2 is slightly off the orthogonal axis. The arrows point to some of the cement line boundaries in the bone cuff. ZCC, zone of calcified cartilage. (b) Transverse section of the ZCC, a solitary spicule in the centre of the image

FIGURE 8.

A scanning electron microscopic image of the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC) containing a bone spicule. (a) The bone cuff is shown surrounding a central canal. The boxed region is shown in (b) at higher magnification. (b) The arrows, progressing from left to right, show the spicule canal, a first layer of longitudinal fibres, and a second layer of relatively transverse fibres

FIGURE 9.

An scanning electron microscopy image showing a clear central canal in a bony spicule. The boxed regions (X and Y) were imaged in high magnification and are shown in Figure 12a,b, respectively. The boxed region shows a distinct gap between the margin of the bone cuff and the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC)

FIGURE 10.

High magnification and resolution images a and b of boxed regions X and Y in Figure 9, respectively. (a) A distinct gap, as indicated by the arrow, between the margin of the bone cuff and the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC) is visible. (b) In the canal, is shown an amorphous mass of relatively non‐fibrous tissue, likely to be vascular

FIGURE 11.

(a) Cartilage‐ZCC‐bone region. The box highlights the tip or apex of a bone spicule which is shown in higher magnification in (b, c). The gap highlighted by the arrow in b is shown in high resolution in c. ZCC, zone of calcified cartilage

The clarity of the collagen fibril in the bone cuff (e.g. Figures 9b and 11c), where the periodic banding has been revealed, also indicates that the amount of inorganic matrix originally present may have been much less than in the surrounding ZCC and even the underlying bone. Finally, away from the tip of the spicule, and at the junction between spicules and the surrounding relatively mature lamellar bone, there too were found the presence of the ‘gaps’ presumably left by the inorganics matrix removal (Figure 12a,b).

FIGURE 12.

Juxtaposition of subchondral bone and spicule. The spicule indicated by the black arrow (in a) and the boxed region is shown in higher magnification (in b). Also, the gap regions are highlighted (in b) by the arrows

4. DISCUSSION

This study showed that bone spicules are significant irregularities in terms of the structure and morphology of the joint cement line. The results from comparing G0, G1 and G2 groups suggest that vascular and marrow spaces may have preceded the bone spicules and that the latter eventually become bone bulges as the cement line advances upwards towards the articular cartilage. This concept of bone development is discussed further in this section. However, it would be prudent to state the limitations of this study. Firstly, little is known of the exact age and breed of the cows from which the patellae were obtained other than that they were adults and between the ages of 6 and 9 years. What is known, however, is that the India ink staining used allows for a consistent classification of the gross appearance of the tissue, and this has been found to be useful in determining the health of the tissue. For example, the grade from the India ink correlates well with clinical histological grading as shown in the present study (Figure 4) and as has been shown previously (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013). Another limitation of the present study is the lack of biochemical testing and evaluation of the bone spicules and the surrounding tissues. The confirmation of the tissue types and more compositional and elemental analysis would be able to provide not only validation to some of the claims in this study but also further insight. The present study instead limits itself to the expertise of the investigators, in the structure and mechanics of musculoskeletal tissues, and hence provides a rather superficial treatment of the wider range of equally exciting aspects of bone biology, chemistry and physiology. Hence this study by no means offers a comprehensive all‐encompassing concept of new bone formation in OA. Instead, the focus of the discussion hereon remains on the bone spicules of the cement line and from a purely structural perspective.

It was found that the bone spicules have a significant and consistent orientation and contain canals that could provide insight into the bone remodelling process in ageing and degeneration of the joint. The morphology of these spicules strongly suggests that they are new osteons formed in the calcified cartilage region, where they possess a cylindrical structure enclosing an osteonal cavity with blood vessels in the centre. Thus, the bone spicule morphology does indicate that a process of new bone formation has taken place with new osteon formation. Osteons form around longitudinal vascular vessels and the collagen fibres in the cuff are parallel to one another (Smith, 1960). After the collagen is laid down by the osteoblasts, the process of calcification starts and leads to the formation of a solid, stable, crystalline inorganic phase within the organic phase (Ascenzi & Roe, 2012). From the present study, the finding of a relative lack of significant fibrillar connection between the ZCC and the bone cuff of the bone spicules, and the relatively easy removal of the inorganic phase via the chemical treatment, would imply that this new bone formation may be the ‘vanguard bone’ that is laid down prior to the maturing process that involves subsequent mineralisation and ossification. A cement line boundary that contains a non‐collagenous mineralised matrix tends to form between new bone material and the surrounding substrate of old bone (Davies, 2007). In bone‐bonded interfaces, the cement line matrix is first secreted by differentiating osteoblasts, and the mineralised matrix invaginates, interdigitates and interlocks with the collagenous matrix of the substrate material (Davies, 2007). Could the formation of bone spicules in the cartilage–bone junction be similar to how ‘de novo bone’ would form in bone‐bonded interfaces, such as the bone–bone interface or boundary lines between osteons and interstitial bone matrix (Davies, 2007)?

The formation of de novo bone involves four stages (Davies, 1998, 2007). Firstly, there is an adsorption of non‐collagenous proteins on the surface of spaces where new bone is to form. These spaces, (marrow cavities) being filled with nutrient fluid, provide the transport means for the accumulation of proteins, from which a dense enough layer forms and becomes suitable for the initiation and laying down of mineralised material. With mineralisation and crystal growth, a substrate forms and collagen is then secreted onto this new substrate, followed by continued mineralisation and its growth and more collagen deposition. The gradual build‐up of material fills the space, and the new material becomes compressed. It is acknowledged that the above‐mentioned theoretical process by Davies (1998) refers to new bone formation at a solid surface. However, it does provide a theoretical framework to describe what could be the likely process for new bone formation in the cartilage–bone junction (see schematics shown in Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

Schematics are used here to show how there could be a possible transition from Type A to Type B defect along with the irregularity of the bone cement line (refer to Figure 2). The proposed transition process is similar to that suggested for de novo bone formation in resorption spaces during bone remodelling (Davies, 2007). In the present context of new bone formation in the cartilage–bone junction, the proposed transition process begins with (a) Type A defect where proteins are first laid down against the inner wall of the marrow space. (b) With the accretion of proteins, there is an induction of mineralization and crystal growth followed by the laying down of collagen. (c) Type B defect where the local mechanical environment alters with the build‐up of material and formation of de novo bone. Complex stresses develop including those that compress the cement line to compact the mineral phase, and those that shear to facilitate morphing and growth of the spicule

The idea of an initial laying down of an inorganic matrix and subsequent compression of this region with ongoing bone formation further allows for comparison with how cement lines are formed in secondary osteons during bone remodelling. We thus suggest that the marrow space (described as ‘Type A’ in Figure 2, and shown schematically in Figure 13a) are similar to, but not necessarily the same as, the resorption space created in the initial phases of bone remodelling (Frost, 1990a, 1990b; Hadjidakis & Androulakis, 2006). The cement lines that form in the remodelling process, begin as ‘globular accretions’ deposited on the resorption surface that eventually fuse to form a continuous cement layer (Zhou et al., 1994). The resorption surface provides a solid surface for osteogenic cells to attach and secrete the matrix associated with the cement line (Hosseini et al., 1999). Cement lines are thus the result of the remodelling process where there is a resorption space being filled with new bone, and the cement line separates the resulting secondary osteon, or Haversian system, from the surrounding bone matrix (Schaffler et al., 1987). Cement lines in secondary osteons are approximately 0.5–1 μm thick (Hosseini et al., 1999; Skedros et al., 2005). In the present study, the thickness of the gap between a bone spicule and the surrounding ZCC following decalcification was not measured, but from the images (refer to Figures 10a and 11c), it appears that the distance is comparable to the thickness of the cement line in secondary osteons. That there should be a gap in the spicule–ZCC interface, a result of the removal of the mineral phase from decalcification, requires further discussion in the context of the cement line of secondary osteons. In the latter, studies have shown that the cement line is a hypermineralised zone and collagen deficient (Okada et al., 2013; Hosseini et al., 1999; Skedros et al., 2005), with significantly higher Ca/P molar ratios than bone (Schaffler et al., 1987). Thus with the removal of this mineral phase, a void would result, and this is consistent with previous SEM studies of bone tissue where the cement line and lamellae boundaries were enhanced following citric acid exposure (Congiu & Pazzaglia, 2011) or the collagen fibrils exposed following complete demineralisation with HCL acid (Traini et al., 2005). We have also used our method of decalcification to study other soft–hard tissue interfaces such as in the ligament–bone (Zhao et al., 2014) and disc–vertebra junctions (Sapiee et al., 2019). In these cases, there is a collagen fibrillar interweave between the ligament of disc and its attachment to bone, such that decalcification and SEM imaging reveals this physical connection, instead of showing a gap as in the present study's images of bone‐spicules and the ZCC (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14.

Following decalcification, the complex soft–hard tissue junction integration is revealed. (a) Zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC)–bone junction. The gap shown here between the cartilage and bone would have been filled with a mineral phase (the specimen prep technique deliberately removes this phase). Compare with (b) the anterior cruciate ligament–bone junction, where the collagen of bone is shown to be intertwined with the collagen of the ligament. Removal of the mineral phase reveals this organic matrix structure (Zhao et al., 2014)

Of interest is the fact that the collagen fibrils in the ZCC are Type II (Hoemann et al., 2012), while in the ligament and tendon it is Type I (Benjamin & Ralphs, 1998). The collagen in bone is Type I. Coincidentally, these collagen types correlate with the exclusive cement interface between the ZCC and bone, and the intertwinement between ligament and bone, is worth exploring further in future work. For example, evidence is emerging showing the transformation of collagen type from II to I in OA, where in the later stages of the disease,the deep zone tissue is affected (Miosge et al., 2004). The structural difference between collagen type I and type II is that the former is a heterotrimer consisting of two α‐1 chains and one α‐2 chain, whereas the latter is a homotrimer consisting only of three α‐1 chains (Bielajew et al., 2020). Type II collagen fibrils contain 50%–100% more water than type I fibrils (Grynpas et al., 1980), and hence how different collagen types coexists and structurally integrate, is a topic of increasing significance in understanding the larger scale tissue mechanics (Chang et al., 2012).

On the question of why these bone spicules arise, this could be addressed at least partly by considering the biomechanics of the joint and joint tissues. In an earlier study, we report that the bone spicules are remarkably like the ‘crossing cones’ and osteons that form in bone healing following rigid compression fracture fixation (Rahn et al., 1971; Thambyah & Broom, 2009). From that viewpoint, it is known that with absolute stability of fixation, Haversian osteons cross the plane of contact of the fracture without obvious change in shape or direction (Perren, 2002). Mechanical signals and their influence on osteon morphology can also be used to explain the strong anisotropy or directionality of the bone spicules. In‐vivo studies on sheep show that bone structural units align to principal strain directions (Lanyon, 1974; Lanyon & Baggott, 1976), and other studies in deer show that compression, compared to tension, leads to a higher density of osteons (Skedros et al., 1994). The spicule morphology (refer to Figure 7) seen in the present study is similar to osteons in compression cortices of the long bone, where these osteons have nearly perfectly round forms (Skedros et al., 1997) and Haversian canal diameters between 20 and 30 μm in diameter (Nguyen & Barak, 2020). Since it is known that the thickening of the ZCC in the joint tissues is one of the progressive developments with age or early degeneration (Daubs et al., 2006; Oegema et al., 1997), it is hypothesised that an increased stiffness in the ZCC could in effect provide the mechanical environment for spicule advance. Indeed, we have found that in early degeneration of the bovine patellae, the ZCC stiffness does increase to approach Young's Modulus that is only five times less than that of the underlying bone, compared to 10 times less in healthy tissue (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2015; Mente & Lewis, 1994). The biomechanical effect of spicules being present, on the larger scale joint tissue mechanics, has not been studied, however, the senior author has recently led computer model simulation studies to gain insight on the local mechanical environment when spicules are present (Arjmandi et al., 2021). Bone spicule numbers and their shape were shown to affect the strain energy density (SED) distribution in the flatter areas of the ZCC–bone junction adjacent to spicules. Stresses, strains and SED analyses provided evidence that the mechanical environment with the addition of spicules was in the magnitude that was previously found to promote bone formation in fracture healing and remodelling (Huiskes et al., 2000; Scheuren et al., 2020). Thus, the biomechanical modelling points to a situation where the regions of bone adjacent to the spicule would be conducive for bone growth, and advance the ZCC–bone interface, or cement line, upwards towards the overlying articular cartilage. However, experimental and modelling research shows in healthy cartilage the osteochondral junction is relatively shielded by the articular cartilage when the joint tissues are loaded (Neu et al., 2005). It is important then to acknowledge the assumption that the increased mechanical stimulation at the bone–ZCC interface is a result from a depreciation in the mechanical function of the overlying articular cartilage. Such an assumption is supported by the following. In the above‐mentioned study (Neu et al., 2005), the authors reported that by increasing the applied stress approximately two times, the resulting strains in the articular cartilage does not change, but instead the strains in the osteochondral junction increases about three times. This sensitivity in the cartilage–bone junction to changes in loading is significant, especially when considering that in structurally compromised cartilage, such as that in OA, the Young's modulus is reduced by two times (Setton et al., 1994), and there is bound to be an increased loading at the soft–hard tissue interface. Indeed, our own experimental studies on the effects of subtle collagen fibrillar network destructuring in the articular cartilage reveal that the distribution of load laterally in healthy cartilage is impaired in early osteoarthritic tissue and results in a dramatic increase of stress transfer directly to the cartilage–bone junction (Thambyah & Broom, 2007). From studies on the same types of bovine tissue used in the present study, we showed that the structural changes associated with articular cartilage degeneration began with a thickening of the ZCC, followed by an advancing of the bone cement line, initiated by bone spicules (Hargrave‐Thomas et al., 2013; Thambyah & Broom, 2009).

Finally, to conclude, a particular significance of this study is proposed. It has been suggested that the bone formation in the osteoarthritic joint is a result of endochondral ossification (Burr & Radin, 2003; Lories & Luyten, 2011). If that was the case, we believe that there would be more morphological and structural evidence, however, there is not. Studies on OA joints that state endochondral ossification as the mechanism for bone formation have been based on genetic, proteomic, and other molecular evidence (Kawaguchi, 2008) or cartilage cell responses (Dreier, 2010). Further in that review paper (Dreier, 2010), it was stated that the cell and molecular signalling factors during endochondral ossification were ‘analysed in spontaneous, transgenic or surgically induced mouse models of OA but not in large animals’. The present authors have not been able to find in the literature the anatomical structural evidence of endochondral ossification processes, such as chondrocyte hypertrophy and extensive blood vessel invasion into the cartilage from the subchondral bone, for OA joints. Importantly, the only evidence of blood vessel invasion into cartilage in the OA process (Suri et al., 2007; Walsh et al., 2007) are described as vascular channels surrounded by a bone cuff, a feature that is not related to endochondral ossification, but primary bone formation in fracture healing instead (Marsell & Einhorn, 2011).

5. DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Additional data, not explicitly shown in the figures presented, that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Hargrave‐Thomas, E.J. & Thambyah, A. (2021) The micro and ultrastructural anatomy of bone spicules found in the osteochondral junction of bovine patellae with early joint degeneration. Journal of Anatomy, 239, 1452–1464. 10.1111/joa.13518

REFERENCES

- Aho, O.M. , Finnilä, M. , Thevenot, J. , Saarakkala, S. & Lehenkari, P. (2017) Subchondral bone histology and grading in osteoarthritis. PLoS One, 12(3), e0173726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjmandi, R. , Kelly, P. & Thambyah, A. (2021) The mechanical influence of bone spicules in the osteochondral junction: a finite element modelling study. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology (under review). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi, M.G. & Roe, A.K. (2012) The osteon: the micromechanical unit of compact bone. Frontiers in Bioscience, 17, 1551–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker‐LePain, J.C. & Lane, N.E. (2012) Role of bone architecture and anatomy in osteoarthritis. Bone, 51(2), 197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, M. & Ralphs, J.R. (1998) Fibrocartilage in tendons and ligaments–an adaptation to compressive load. Journal of Anatomy, 193(Part 4), 481–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielajew, B.J. , Hu, J.C. & Athanasiou, K.A. (2020) Collagen: quantification, biomechanics, and role of minor subtypes in cartilage. Nature Reviews Materials, 5(10), 730–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter, J.A. & Brown, T.D. (2004) Joint injury, repair, and remodeling: roles in post‐traumatic osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 423, 7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter, J.A. & Mankin, H.J. (1998). Articular cartilage: degeneration and osteoarthritis, repair, regeneration, and transplantation. Instructional Course Lectures, 47, 487–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr, D.B. & Gallant, M.A. (2012). Bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 8(11), 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr, D.B. & Radin, E.L. (2003) Microfractures and microcracks in subchondral bone: are they relevant to osteoarthrosis? Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America, 29(4), 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr, D.B. & Schaffler, M.B. (1997) The involvement of subchondral mineralized tissues in osteoarthrosis: quantitative microscopic evidence. Microscopy Research and Technique, 37(4), 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.W. , Shefelbine, S.J. & Buehler, M.J. (2012) Structural and mechanical differences between collagen homo‐ and heterotrimers: relevance for the molecular origin of brittle bone disease. Biophysical Journal, 102(3), 640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.M. (1990) The structure of vascular channels in the subchondral plate. Journal of Anatomy, 171, 105–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.M. & Huber, J.D. (1990) The structure of the human subchondral plate. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 72(5), 866–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congiu, T. & Pazzaglia, U.E. (2011). The sealed osteons of cortical diaphyseal bone. Early observations revisited with scanning electron microscopy. The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology, 294(2), 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin, T.R. & Kennedy, O.D. (2016) The role of subchondral bone damage in post‐traumatic osteoarthritis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1383(1), 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubs, B.M. , Markel, M.D. & Manley, P.A. (2006) Histomorphometric analysis of articular cartilage, zone of calcified cartilage, and subchondral bone plate in femoral heads from clinically normal dogs and dogs with moderate or severe osteoarthritis. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 67(10), 1719–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.E. (1998) Mechanisms of endosseous integration. The International Journal of Prosthodontics, 11(5), 391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.E. (2007) Bone bonding at natural and biomaterial surfaces. Biomaterials, 28(34), 5058–5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier, R. (2010) Hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes in osteoarthritis: the developmental aspect of degenerative joint disorders. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 12(5), 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnilä, M. , Thevenot, J. , Aho, O.M. , Tiitu, V. , Rautiainen, J. , Kauppinen, S. et al. (2017) Association between subchondral bone structure and osteoarthritis histopathological grade. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 35(4), 785–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost, H.M. (1990a) Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 1. Redefining Wolff's law: the bone modeling problem. The Anatomical Record, 226(4), 403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost, H.M. (1990b) Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 2. Redefining Wolff's law: the remodeling problem. The Anatomical Record, 226(4), 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynpas, M.D. , Eyre, D.R. & Kirschner, D.A. (1980) Collagen type II differs from type I in native molecular packing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 626(2), 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjidakis, D.J. & Androulakis, I.I. (2006) Bone remodeling. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1092, 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave‐Thomas, E. , van Sloun, F. , Dickinson, M. , Broom, N. & Thambyah, A. (2015) Multi‐scalar mechanical testing of the calcified cartilage and subchondral bone comparing healthy vs early degenerative states. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 23(10), 1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave‐Thomas, E.J. , Thambyah, A. , McGlashan, S.R. & Broom, N.D. (2013) The bovine patella as a model of early osteoarthritis. Journal of Anatomy, 223(6), 651–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoemann, C.D. , Lafantaisie‐Favreau, C.H. , Lascau‐Coman, V. , Chen, G. & Guzmán‐Morales, J. (2012) The cartilage‐bone interface. Journal of Knee Surgery, 25(2), 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.M. , Shiga, A. & Davies, J.E. (1999) Formation of cement lines, but not laminae limitantes, requires contact of differentiating osteogenic cells to solid surfaces. Cells and Materials, 9(2), Article 1. [Google Scholar]

- Huiskes, R. , Ruimerman, R. , van Lenthe, G.H. & Janssen, J.D. (2000) Effects of mechanical forces on maintenance and adaptation of form in trabecular bone. Nature, 405(6787), 704–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, H. (2008) Endochondral ossification signals in cartilage degradation during osteoarthritis progression in experimental mouse models. Molecules and Cells, 25(1), 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon, L.E. (1974) Experimental support for the trajectorial theory of bone structure. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 56(1), 160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon, L.E. & Baggott, D.G. (1976) Mechanical function as an influence on the structure and form of bone. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 58‐B(4), 436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Yin, J. , Gao, J. , Cheng, T.S. , Pavlos, N.J. , Zhang, C. et al. (2013) Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 15(6), 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lories, R.J. & Luyten, F.P. (2011) The bone‐cartilage unit in osteoarthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 7(1), 43–49. 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madry, H. , van Dijk, C.N. & Mueller‐Gerbl, M. (2010) The basic science of the subchondral bone. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 18(4), 419–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahjoub, M. , Berenbaum, F. & Houard, X. (2012) Why subchondral bone in osteoarthritis? The importance of the cartilage bone interface in osteoarthritis. Osteoporosis International, 23(Supplement 8), S841–S846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsell, R. & Einhorn, T.A. (2011) The biology of fracture healing. Injury, 42(6), 551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mente, P.L. & Lewis, J.L. (1994) Elastic modulus of calcified cartilage is an order of magnitude less than that of subchondral bone. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 12(5), 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miosge, N. , Hartmann, M. , Maelicke, C. & Herken, R. (2004) Expression of collagen type I and type II in consecutive stages of human osteoarthritis. Histochemistry and Cell Biology, 122(3), 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, S. , Harruff, R. & Burr, D.B. (1993) Microcracks in articular calcified cartilage of human femoral heads. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 117(2), 196–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratovic, D. , Findlay, D.M. , Cicuttini, F.M. , Wluka, A.E. , Lee, Y.R. & Kuliwaba, J.S. (2018) Bone matrix microdamage and vascular changes characterize bone marrow lesions in the subchondral bone of knee osteoarthritis. Bone, 108, 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu, C.P. , Hull, M.L. & Walton, J.H. (2005) Heterogeneous three‐dimensional strain fields during unconfined cyclic compression in bovine articular cartilage explants. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 23(6), 1390–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, J.T. & Barak, M.M. (2020) Secondary osteon structural heterogeneity between the cranial and caudal cortices of the proximal humerus in white‐tailed deer. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 223(Part 11), jeb225482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oegema, T.R. Jr , Carpenter, R.J. , Hofmeister, F. & Thompson, R.C. Jr (1997) The interaction of the zone of calcified cartilage and subchondral bone in osteoarthritis. Microscopy Research and Technique, 37(4), 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada, H. , Tamamura, R. , Kanno, T. , Nakada, H. , Yasuoka, S. , Arikawa, K. et al. (2013) Ultrastructure of cement lines. Journal of Hard Tissue Biology, 22(4), 445–450. 10.2485/jhtb.22.445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perren, S.M. (2002) Evolution of the internal fixation of long bone fractures. The scientific basis of biological internal fixation: choosing a new balance between stability and biology. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British Volume, 84(8), 1093–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin, E.L. , Burr, D.B. , Caterson, B. , Fyhrie, D. , Brown, T.D. & Boyd, R.D. (1991) Mechanical determinants of osteoarthrosis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 21(3 Supplement 2), 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin, E. L. , Parker, H. G. , Pugh, J. W. , Steinberg, R. S. , Paul, I. L. & Rose, R. M. (1973) Response of joints to impact loading. 3. Relationship between trabecular microfractures and cartilage degeneration. Journal of Biomechanics, 6(1), 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin, E.L. , Paul, I.L. & Tolkoff, M.J. (1970) Subchondral bone changes in patients with early degenerative joint disease. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 13(4), 400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin, E.L. & Rose, R.M. (1986) Role of subchondral bone in the initiation and progression of cartilage damage. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 213, 34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn, B.A. , Gallinaro, P. , Baltensperger, A. & Perren, S.M. (1971) Primary bone healing. An experimental study in the rabbit. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 53(4), 783–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiee, N.H. , Thambyah, A. , Robertson, P.A. & Broom, N.D. (2019) New evidence for structural integration across the cartilage‐vertebral endplate junction and its relation to herniation. The Spine Journal, 19(3), 532–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffler, M.B. , Burr, D.B. & Frederickson, R.G. (1987) Morphology of the osteonal cement line in human bone. The Anatomical Record, 217(3), 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuren, A.C. , Vallaster, P. , Kuhn, G.A. , Paul, G.R. , Malhotra, A. , Kameo, Y. et al. (2020) Mechano‐regulation of trabecular bone adaptation is controlled by the local in vivo environment and logarithmically dependent on loading frequency. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8, 566346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setton, L.A. , Mow, V.C. , Müller, F.J. , Pita, J.C. & Howell, D.S. (1994) Mechanical properties of canine articular cartilage are significantly altered following transection of the anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 12(4), 451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skedros, J.G. , Holmes, J.L. , Vajda, E.G. & Bloebaum, R.D. (2005) Cement lines of secondary osteons in human bone are not mineral‐deficient: new data in a historical perspective. The Anatomical Record. Part A, Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology, 286(1), 781–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skedros, J.G. , Mason, M.W. & Bloebaum, R.D. (1994) Differences in osteonal micromorphology between tensile and compressive cortices of a bending skeletal system: indications of potential strain‐specific differences in bone microstructure. The Anatomical Record, 239(4), 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skedros, J.G. , Su, S.C. & Bloebaum, R.D. (1997) Biomechanical implications of mineral content and microstructural variations in cortical bone of horse, elk, and sheep calcanei. The Anatomical Record, 249(3), 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.W. (1960) The arrangement of collagen fibres in human secondary osteones. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 42‐B, 588–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, L. (1993) Microcracks in the calcified layer of articular cartilage. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 117(2), 191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri, S. , Gill, S.E. , Massena de Camin, S. , Wilson, D. , McWilliams, D.F. & Walsh, D.A. (2007) Neurovascular invasion at the osteochondral junction and in osteophytes in osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 66(11), 1423–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri, S. & Walsh, D.A. (2012) Osteochondral alterations in osteoarthritis. Bone, 51(2), 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thambyah, A. & Broom, N. (2007) On how degeneration influences load bearing in the cartilage‐bone system: a microstructural and micromechanical study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 15(12), 1410–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thambyah, A. & Broom, N. (2009) On new bone formation in the pre‐osteoarthritic joint. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 17(4), 456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traini, T. , Degidi, M. , Strocchi, R. , Caputi, S. & Piattelli, A. (2005) Collagen fiber orientation near dental implants in human bone: do their organization reflect differences in loading? Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part B, Applied Biomaterials, 74(1), 538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verborgt, O. , Gibson, G.J. & Schaffler, M.B. (2000) Loss of osteocyte integrity in association with microdamage and bone remodeling after fatigue in vivo. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 15(1), 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein, W. , Perino, G. , Gilbert, S.L. , Maher, S.A. , Windhager, R. & Boettner, F. (2016) OARSI osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology assessment system: A biomechanical evaluation in the human knee. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 34(1), 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D.A. , Bonnet, C.S. , Turner, E.L. , Wilson, D. , Situ, M. & McWilliams, D.F. (2007) Angiogenesis in the synovium and at the osteochondral junction in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 15(7), 743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.G. , Greenwald, A.S. & Haynes, D.W. (1970) Subchondral vascularity in the human femoral head. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 29(2), 138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.D. , Burr, D.B. , Boyd, R.D. & Radin, E.L. (1990) Bone and cartilage changes following experimental varus or valgus tibial angulation. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 8(4), 572–585. 10.1002/jor.1100080414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. , Thambyah, A. & Broom, N.D. (2014) A multi‐scale structural study of the porcine anterior cruciate ligament tibial enthesis. Journal of Anatomy, 224(6), 624–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Chernecky, R. & Davies, J.E. (1994) Deposition of cement at reversal lines in rat femoral bone. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 9(3), 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data, not explicitly shown in the figures presented, that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.