Abstract

Combination therapies with agents targeting the DNA damage response (DDR) offer an opportunity to selectively enhance the therapeutic index of chemoradiation or eliminate chemotherapy altogether. The successful translation of DDR inhibitors to clinical use requires investigating both their direct actions as (chemo)radiosensitizers, and their potential to stimulate tumor immunogenicity. Beginning with high-throughput screening using both viability and DNA damage-reporter assays, followed by validation in ‘gold standard’ radiation colony forming assays and in vitro assessment of mechanistic effects on the DDR we describe proven strategies and methods leading to the clinical development of DDR inhibitors both with radiation alone and in combination with chemoradiation. Beyond these in vitro studies, we discuss the impact of key features of human xenograft and syngeneic mouse models on the relevance of in vivo tumor efficacy studies, particularly with regard to the immunogenic effects of combined therapy with radiation and DDR inhibitors. Finally, we describe recent technological advances in radiation delivery (using the Small Animal Radiation Research Platform (SARRP)) that allow for conformal, clinically relevant radiation therapy in mouse models. Taken together, this overall approach is critical to the successful clinical development and ultimate FDA approval of DDR inhibitors as (chemo)radiation sensitizers.

INTRODUCTION

Radiation with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard of care for the treatment of most locally advanced cancers. Since unrepaired DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) are responsible for the majority of cell death following (chemo)radiation (1), targeting the cellular DNA damage response (DDR), which can include activation of innate immune signaling in addition to activation of both DNA repair pathways and cell cycle checkpoints, is a promising strategy for sensitizing tumor cells to chemoradiation (2-4)(Fig. 1). Preclinical studies from our and other groups over the past 15 years have demonstrated that inhibition of the DDR can be a highly effective for sensitizing solid tumors to chemoradiation therapy (5-8). Beyond establishing efficacy, however, it is imperative for the successful translation to early stage clinical trials to address normal tissue toxicities, optimize treatment schedules and identify the mechanisms critical for tumor response, as well as their related biomarkers. In recent years there have been several reviews addressing the barriers between promising preclinical therapeutic strategies and translation to successful clinical trials covering such general topics as the impact of inadequate experimental design and reporting (9), as well as the importance of predictive and pharmacodynamic biomarkers (10,11), more relevant tumor model systems (12-16), the tumor microenvironment (17-19) and the ability to deliver clinically-relevant radiation in preclinical models (20). In the following review, we will discuss our progress in optimizing the steps for taking DDR inhibitors identified in high throughput screening through the in vitro validation process, preclinical therapeutic studies that assess both direct tumor response and systemic immune responses and finally translation to clinical trial with an emphasis on the methodologies and best practices that maximize the likelihood of success.

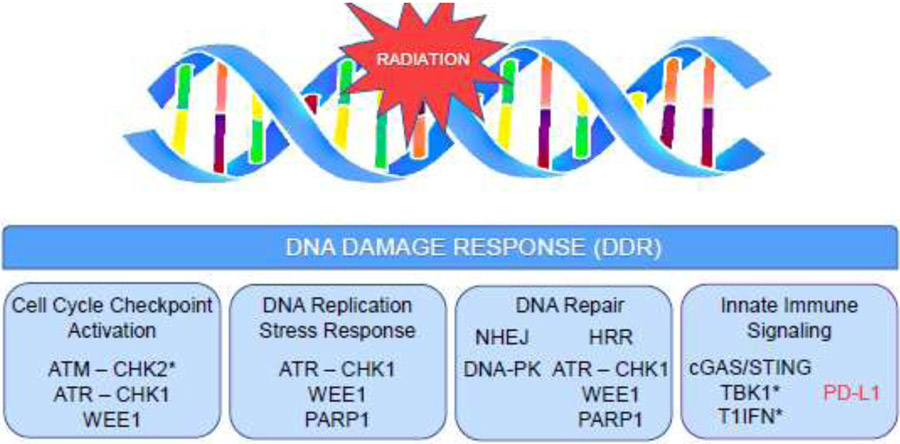

Figure 1: Pharmacological targets in the radiation-induced DNA damage response (DDR).

Inhibition of DDR effector proteins potentiates persistent (chemo)radiation-induced DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) by multiple interconnected mechanisms that can be broadly categorized as targeting cell cycle regulation, targeting DNA replication, or targeting DNA repair. Mitotic progression in the presence of unrepaired DSBs leads to accumulation of micronuclei and cytosolic dsDNA which signal activation of both pro-inflammatory, anti-tumor (shown in black) and immunosuppressive (shown in red) immune signaling pathways. Key signaling molecules that are not currently pharmacological targets for anti-cancer therapy are included (*).

Prioritization of DDR inhibitors as chemoradiation sensitizers using high-throughput screens (HTS)

In an effort to identify novel molecular targets for sensitization to chemoradiation, the current standard of care in many locally advanced cancers, we first conducted an unbiased high-throughput siRNA library screen of 8,800 potentially druggable targets in pancreatic cancer cells (21). Three of the top five hits were proteins involved in the DDR: CHK1, ATR and PP2A. A significant body of preclinical work confirms that agents targeting these proteins sensitize to chemoradiation (21-25), and ATR inhibitors are the focus of several active clinical trials (26). The results of these studies led us to assess the chemoradiosensitizing activity of agents within the CTEP (Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program) portfolio that target these and other proteins in the DDR.

Since a reliable large-scale automated high-throughput colony forming assay is still under development, cell viability post-treatment was determined with the ATP-dependent CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega). In this singlestep assay, ATP-dependent firefly luciferase activity is used as a surrogate for cellular metabolic activity and viability. While this HTS format allows for the screening of multiple drug concentrations and treatment schedules in addition to multiple tumor models and DDR inhibitors, it does not capture the long-term effects of radiation on clonogenic survival (see below).

One of the inefficiencies inherent in viability-based HTS is the frequency of false positives or non-specific hits that result from loss of signal due to either compound interference with the reporter substrate or non-mechanism based toxicity. To address these issues, we have adopted orthogonal screens for use in parallel with the HTS viability assay described above to assess either DNA damage and modulation of the DDR, or apoptotic cell death. To assess modulation of the DDR, we have developed a bioluminescent, live cell DNA damage response reporter (DDRR) assay for ATM kinase activity wherein phosphorylation of a CHK2 peptide fragment can be monitored quantitatively in real time (Fig. 2A-B)(27). The ability of the DDRR to report ATM/ATR kinase activity dynamically over multiple timepoints permits monitoring of both ATM/ATR kinase inhibition, which results in a rapid increase in DDRR activity, as well as the later increases in ATM/ATR activity that accompany persistent DNA damage (e.g. due to inhibition of DNA repair downstream of ATM/ATR) (Fig. 2C-F). A strength of this approach is that a positive hit is defined by an increase in bioluminescence activity so the DDRR screen is less likely to result in false positives.

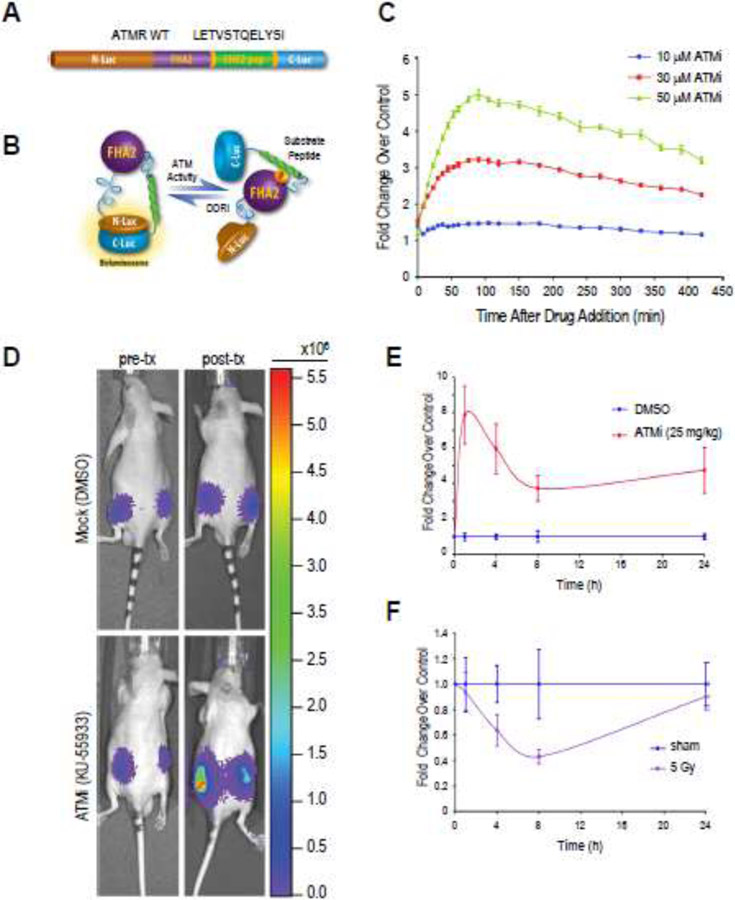

Figure 2: A live cell, quantitative and real-time DNA Damage Response Reporter (DDRR).

(A, B) Illustration of the DDRR, which consists of a phospho-Ser/Thr-binding domain (FHA2), an ATM substrate domain (from CHK2), and split firefly luciferase domains. When ATM or ATR is active, the CHK2 target peptide is phosphorylated, interacting with the FHA2 domain and producing steric constraints that inhibit functional reconstitution of luciferase activity. When ATM or ATR is inhibited, the CHK2 target peptide is hypo-phosphorylated, allowing for split luciferase complementation and increased bioluminescence activity. (C) Quantitative and real-time imaging of ATM kinase activity. D54 cells stably expressing the DDRR (D54-ATMR WT) were treated with the ATM kinase inhibitor KU-55933 (ATMi; 10, 30 or 50 μM) and live-cell bioluminescence activity was read 10 min after the addition of D-luciferin. Treatment with KU-55933 resulted in a time and concentration-dependent increase in bioluminescence activity. (D-F) In vivo measurement of ATM kinase activity in mouse tumor xenograft model. CD-1 nude mice harboring D54-ATMR WT tumor xenografts were injected with luciferin to establish baseline bioluminescence. Three hours later, animals were injected with either KU-55933 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle control (DMSO) and bioluminescence was acquired 1, 4, 8, and 24 h posttreatment. Inhibition of ATM by KU-55933 is indicated by increased bioluminescence (E; fold change over pre-treatment control). Alternatively, mice bearing D54-ATMR WT tumor xenografts were whole body irradiated with 5 Gy and bioluminescence was measured for up to 24 h (F). The transient decrease in reporter activity relative to pre-radiation control is suggestive of radiation induced DNA damage, activation of ATM and subsequent repair.

In an effort to screen for cell death at a more mechanistic level, we also developed and adopted the use of a second orthogonal screen for live cell imaging of caspase-3 dependent apoptosis in real time (28,29). The use of this screen is based on the hypothesis that inhibition of the DDR may potentiate chemoradiation-mediated activation of the apoptotic signaling cascade, and furthermore that apoptosis may better correlate with therapeutic efficacy than acute effects on growth or metabolic activity. The reporter molecule in the assay consists of luciferase peptide fragments split by a caspase 3 DEVD cleavage site; caspase 3 activity results in an increase in bioluminescence. Agents which have a chemoradiation enhancement ratio of >1.3 in the original screen and induce bioluminescence fold changes >2 in both orthogonal assays will be considered positive hits. Importantly, these screens are adaptable to any system that can be engineered to stably express the reporter constructs, including the 3D cell culture formats currently in development for HTS (Willers, this issue) as well as cells for in vivo xenograft or allograft studies.

In vitro validation with the clonogenic radiosensitization survival assay

Since its introduction by Puck and Marcus in the 1950s, the clonogenic survival assay has been the ‘gold standard’ assay for determining radiosensitivity in vitro (30) and represents the beginning of the bench-to-bedside pipeline for candidate radiosensitizing agents (Fig. 3). Unlike the viability assays used in high-throughput screening that measure the acute effects of chemoradiation on proliferation, apoptosis and/or metabolic activity, viability in the clonogenic assay is defined by long term proliferative capacity – a single cell that establishes a colony of 50 or more cells is scored ‘viable.’ Briefly, exponentially growing cells are treated with a minimally-toxic combination of clinically achievable chemotherapy and/or DDR inhibitor, followed by radiation (typically 0-8 Gy in 2Gy increments). Samples are trypsinized to establish a single-cell suspension and replated at clonogenic density; an empirically-determined number of cells per dish that allows for establishment of distinct colonies. Alternatively, cells can be plated at clonogenic density the day before treatment with the caveat that the threshold for colony counts is corrected for cells that doubled prior to RT. Cells are then incubated for a finite length of time, typically 8-14 days, to allow for colony formation (for a detailed general protocol and technical considerations, see (31)).

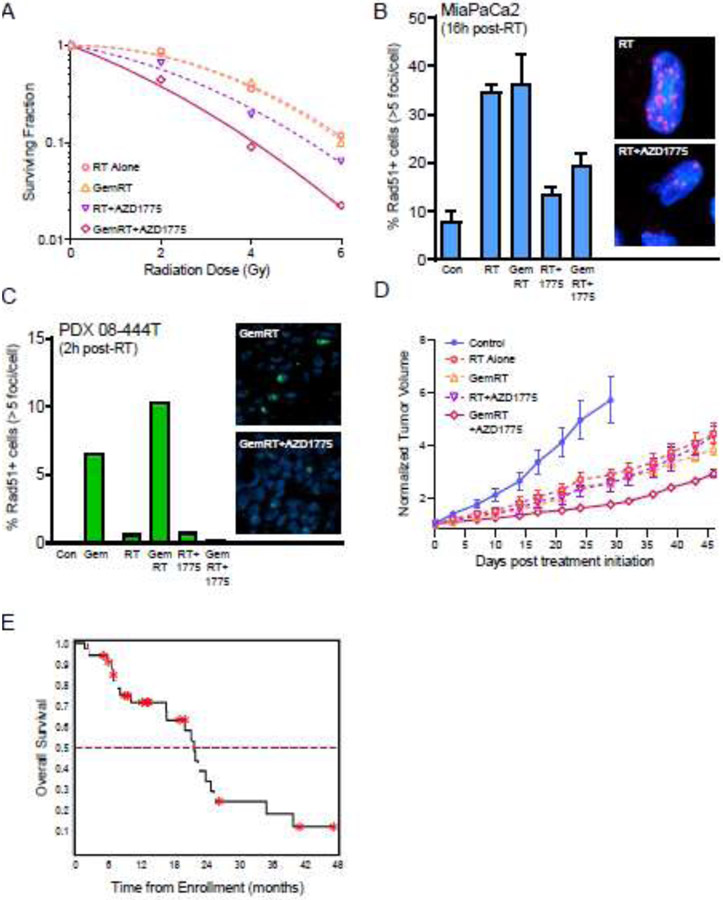

Figure 3: Development of chemoradiation-DDR inhibitor combination therapy from mechanistic studies to clinical trials.

(A) Representative chemoradiation survival curves of MiaPaCa2 cells treated with non-toxic concentrations of gemcitabine (50 nM) and the WEE1 inhibitor AZD1775 (200 nM) prior to radiation (0, 2, 4 or 6 Gy) (Parsels LA, unpublished data). Radiation survival was assessed by clonogenic assay 24 hours post-radiation. (B, C) Radiation-induced Rad51 focus formation. AZD1775-mediated radiosensitization correlated with inhibition of Rad51 focus formation, both in MiaPaCa2 cells treated in vitro (B), and patient-derived pancreatic tumor xenografts treated in vivo (C; adapted from (46). (D) Tumor growth delay in PDX 08-444T tumors treated with radiation, gemcitabine and/or AZD1775 (adapted from (46)). (E) Kaplan-Meier curve for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with AZD1775 in combination with standard gemcitabine-radiation therapy (GemRT) (adapted from (48)).

To assess radiosensitization, the fraction of cells that form colonies (plating efficiency) is first calculated for each sample. The surviving fraction for a given dose of radiation is then determined by normalizing the plating efficiency of the irradiated sample to the plating efficiency for the corresponding unirradiated, drug-treated sample. Radiation survival curves (Fig. 3A) are fitted from the resultant data using the linear-quadratic equation, and the mean inactivation dose (MID) for each curve calculated according to the method of Fertil et al (31,32). The ratio of the MIDs for radiation-treated cells to chemoradiation-treated cells is termed the radiation enhancement ratio (RER). A RER significantly greater than 1 indicates radiosensitization. Since the MID calculation is weighted on the low-dose, linear portion of the curve, the radiosensitizing activity of drugs that only sensitize to high dose radiation may be missed when calculating RERs based on MID (32). Alternatively, RERs can be calculated based on a designated percent survival (e.g., 1% survival dose) or the surviving fraction at a designated radiation dose (e.g., surviving fraction at 2 Gy; SF2). In addition to careful design and analysis of radiation survival, radiation dose rates need to be certified through the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST)-traceable dosimetry to ensure standardization of radiation dose delivery across laboratories.

One key feature of the clonogenic assay is the extended post-treatment incubation period which captures the effects of both transient growth delays and the replication-dependent toxicities such as mitotic catastrophe caused by (chemo)radiation (33). Furthermore, cell proliferation or metabolic activity assays do not have the dynamic range of the clonogenic survival assay, which can be powered to quantitate several logs of cell kill. There are, however, several key considerations that can contribute to a lack of inter-group reproducibility or misinterpretation of results. One of the reasons the clonogenic survival assay is so time, resource and labor-intensive is that many of the key steps, such as replating the treated cells at clonogenic density, must be determined empirically for each treatment condition. While it is often assumed that plating efficiency is linear with regard to the number of cells plated and the number of colonies scored, cell density-dependent factors such as autocrine and paracrine signaling can significantly impact the clonogenic potential of individual cells (34). For this reason, multiple seeding densities are required for each condition to ensure an appropriate number of cells have been plated, and the appropriate number of cells to plate for a control sample is not the same as for conditions that result in several logs of cell kill; cells should be plated to ensure similar numbers of colonies are established for all treatment conditions (9,34).

A second consideration has to do with data analysis. In order to assess radiosensitization, rather than overall cytotoxicity of potential chemoradiation-DDR inhibitor combination therapies, it is important to normalize radiation survival data to the appropriate drug-alone condition rather than the untreated control. This step corrects for any toxicity associated with drug treatment alone. Since the ultimate therapeutic goal is to sensitize tumor cells to radiation while sparing normal tissue of drug-induced toxicity, combinations of DDR inhibitor and chemotherapy that have minimal effects of survival should be used. While many DDR inhibitors are non-toxic as single agents, they often chemosensitize as well as radiosensitize, and it is important to pre-determine chemotherapy-DDR inhibitor conditions that are biologically active but relatively non-toxic (35,36) Furthermore, the combined effects of DDR inhibitors with chemo(radiation) may be synergistic, additive or even antagonistic (37). A thorough understanding of the interactions between drug and radiation-induced cytotoxicity is critical for the rational design of subsequent preclinical tumor studies, but beyond the scope of this review.

The main limitation of the clonogenic assay is that, for the most part, it is restricted to 2D culture models of established cell lines which lack not only genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity but also the influence of other cell types present in the tumor microenvironment (TME) such as cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, tumor-associated macrophages and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. To address this issue while maintaining some of the advantages of in vitro cell culture, more physiologically relevant, 3D cell culture models have been developed (38-42). These 3D tumor models vary in complexity from simple cell-line derived spheroids to complex tumor organoids, often established from tissue biopsy cultures, which include multiple cell types from the TME (reviewed in (43)). Tumor organoids offer the opportunity to evaluate novel agents in genetically and histopathologically heterogeneous models where crosstalk between tumor cells and the TME is preserved.

In vitro mechanistic studies to optimize chemoradiation combination therapies

In concert with clonogenic survival assays, in vitro mechanistic studies assess the potential for schedule-dependent efficacy, distinguish associative from causal biological effects, suggest patient populations who will most benefit from therapy, establish clinically-relevant pharmacodynamic biomarkers to verify target engagement in vivo and determine how to maximize and leverage DNA damage to engage innate immunity for a therapeutic response. Inhibition of the DNA damage response potentiates persistent (chemo)radiation-induced DSBs by a variety of interconnected mechanisms which may make it challenging to distinguish between mechanisms associated with target inhibition and those causative for therapeutic efficacy. For the purposes of strategizing with standard chemoradiation therapies, these mechanisms can be broadly categorized as targeting cell cycle regulation, DNA replication or DNA repair.

Cell cycle checkpoints

Early mechanistic studies on the therapeutic potential of targeting the DNA damage response were based on the hypothesis that abrogation of DDR cell cycle checkpoints, in particular the intra S-phase and G2/M checkpoints, potentiates the cytotoxic effects of radiation-induced DSBs due to aberrant cell cycle progression in the presence of unrepaired lesions (44). These models presume that normal cells with an intact P53-mediated G1 checkpoint are resistant to agents that target the S- and G2/M-checkpoints (such as WEE1 inhibitors), while TP53-mutant tumor cells lacking the G1 checkpoint are not (45). Molecular markers associated with aberrant cell cycle progression, such as attenuated Y15-CDK phosphorylation, have been used successfully as biomarkers for DDR inhibitor activity in both preclinical models (46,47) and clinical trials (48), despite the observation that TP53 status does not always correlate with clinical benefit (49,50). The most widely-used methods for assessing cell cycle checkpoint abrogation by DDR inhibitors involve multi-parameter flow cytometry for markers of S phase (e.g. BrdU), mitosis (pHistoneH3 (Ser10) or MPM2) and/or DNA content (propidium iodide) (reviewed in (51)).

DNA damage and repair- γH2AX and the DNA damage response

The most commonly accepted marker for radiation-induced DSBs is phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX) (reviewed in (52)). As such, γH2AX staining is widely used to investigate the effects of DDR inhibitors on (chemo)radiation-induced DNA damage and repair, and γH2AX staining has been used as a pharmacodynamic biomarker in the clinical trials of several agents that target the DDR (49,53,54). While there is a substantial body of evidence documenting the strong correlation between DSBs induced by ionizing radiation and γH2AX foci (55,56) interpretation of results in combination with chemotherapy and/or inhibitors of the DNA damage response is complicated as H2AX is phosphorylated by different DDR kinases in response to different types of DNA damage including stalled or slowed DNA replication forks (57) and pre-apoptotic signaling (58,59). Different patterns of γH2AX staining, including distinct nuclear foci, high-intensity pan-nuclear staining, and a nuclear ring have been associated with DSBs, replication stress (60) and apoptotic DNA fragmentation, respectively, and in some cases may better correlate with therapeutic efficacy than focal γH2AX staining (Fig. 4A, B) (61-63).

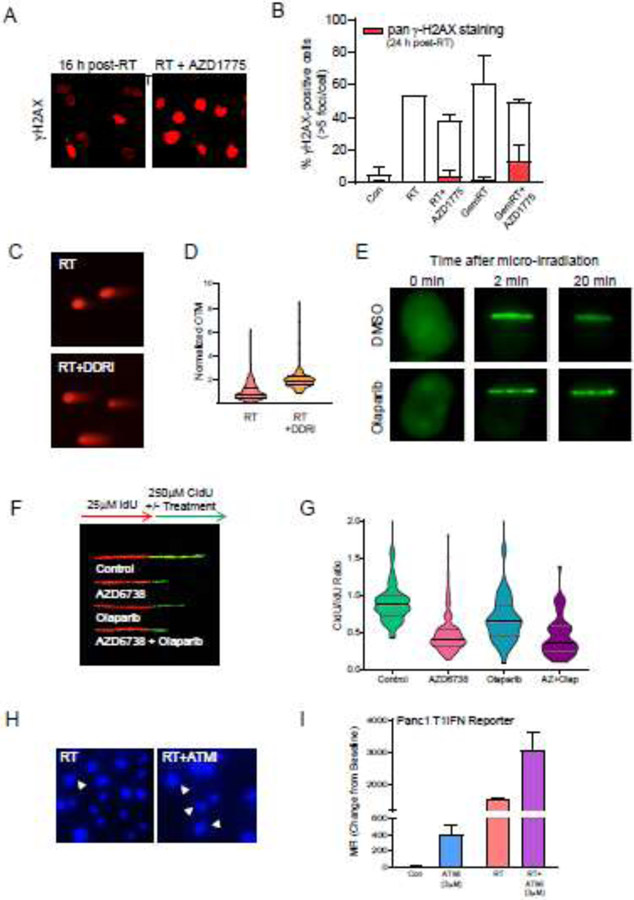

Figure 4: Survey of methods for investigating the effects of DDR inhibitors on (chemo)radiation-induced DNA damage responses in vitro.

(A, B) Pan-nuclear and focal γH2AX staining. Representative images (A) and quantitation (B) of γH2AX staining patterns in cells treated with radiation, gemcitabine and/or the WEE1 inhibitor AZD1775 (Parsels LA, Parsels JD, unpublished data). AZD1775-mediated (chemo)radiosensitization correlated with increased pan-nuclear, rather than focal, γH2AX staining, supporting the hypothesis that replication stress is a key mechanism for these effects (61,79). (C, D) Assessing radiation-induced DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) with the neutral comet assay. Representative images (C) and quantitation (D) of residual DSBs 24 h after treatment with radiation alone or with combined ATR and PARP inhibitors (AZD6738 and olaparib, respectively; DDRi) (adapted from (128)). Individual Olive Tail Moment (OTM) measurements were first normalized to the mean OTM value from an internal control (cells collected immediately following irradiation with 8 Gy on ice) and then to the mean normalized OTM for the radiation alone sample. The frequency distributions for data from each sample are presented in a violin plot with lines indicating median and interquartile range. (E) Monitoring assembly of DDR proteins at sites of micro-irradiation-induced DNA damage. Representative images demonstrating the effects of olaparib on GFP-PARP1 localization at micro-irradiated DNA damage are shown. Olaparib delayed dissociation of PARP1 from sites of DNA damage (Zhang, Q., unpublished data). (F, G) Assessing the replication-directed effects of DDR inhibitors with DNA fiber combing. Representative fibers (F) and quantitation (G) of replication fork progression during treatment with DDR inhibitors. Fibers best-illustrating the acute effects of AZD6738 and olaparib on DNA replication at on-going forks were assembled and aligned to facilitate comparisons (F). Double-labelled replication forks from 3-8 fields per slide were analyzed manually using ImageJ software (NIH), consistent with previously described methodology (G) (Parsels LA, Parsels JD, unpublished data)(88). Stalled and/or slowed replication forks are indicated by a CldU/IdU ratio significantly less than 1. (H) Representative images of DAPI-stained micronuclei formed 72 h after treatment with 8 Gy radiation alone or in combination with the ATM inhibitor AZD0156 (ATMi) (Wang, W., unpublished data). (I) IFNB1-GFP reporter assay to assess the effects of ATM inhibition on innate immune signaling (adapted from (92)). Panc1 cells stably transduced with the IFNB1 promoter reporter (96) were treated with 3 μM KU60019 (ATMi) for 3 days. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was then determined by flow cytometry. Both ATMi and radiation, alone and in combination, induced IFNB1 promotor activity, supporting the hypothesis that radiation-induced DNA damage stimulates an inflammatory response.

DNA damage vs DNA damage response

An important consideration is that the methods described above assess DDR signaling rather than DNA damage and as such these methods are not always reliable surrogates for DNA damage and/or repair. For example, AZD6738, which inhibits ATR-mediated phosphorylation of H2AX in response to ionizing radiation, actually exacerbates radiation-induced DNA damage (64). The most common method to directly measure radiation-induced DNA damage in individual cells is the comet assay (reviewed in (65))(Fig. 4C). The assay can be run under neutral or alkaline conditions to assess DSBs specifically or single-strand breaks and DSBs and is based on the assumption that the more strand breaks and/or alkali-labile sites, the more potential for relaxed DNA and the greater the fraction of DNA in the tail. Results are often expressed as the Olive Tail Moment (OTM) which captures both the fraction of DNA in the tail, and the distance between the head mean and tail mean (Fig. 4D) (66). One of the limitations in interpreting comet assay data with respect to translational studies, however, has been the high level of interlaboratory variability in both experimental protocols and data analysis (67). For this reason, considerable effort has gone into establishing minimal standards for conducting the comet assay, including the use of reference standards (68), and for presenting and analyzing the results (69).

DNA repair mechanisms that determine chemoradiosensitization by DNA damage response inhibitors

Radiation-induced DSBs are primarily repaired by two processes: nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination repair (HRR) (1,70). Since different DDR inhibitors differentially affect these DNA repair pathways (Fig. 1), it is of particular importance, in both choosing agents for combination therapies and identifying patient tumors that will best respond to a given combination therapy, to understand the role of DNA repair in determining tumor response to chemoradiation in a context-dependent manner. While defects in both NHEJ (71) and HRR (72) are associated with radiosensitivity, it is the HRR-defective phenotype that is most prevalent in cancer, and studies confirm that HRR deficiency confers hypersensitivity to certain chemotherapeutic agents as well the DDR inhibitors that target either ATR (73) or PARP1 (74). Furthermore, we and others have found that inhibition of HRR is a key mechanism of (chemo)radiosensitization by ATR, CHK1 or WEE1 inhibitors which can pharmacologically impose an HRR deficient phenotype in the absence of any intrinsic HRR mutations (23-25,46).

There are two primary methods used to assess general HRR function in vitro: immunofluorescence (IF) staining for damage-induced Rad51 focus formation (Fig. 3B), and a DR-GFP reporter assay where HRR-mediated repair of a restriction-enzyme mediated DSB results in expression of GFP (75). While Rad51 IF staining visualizes a step in the HRR process, the accumulation of Rad51 protein on ssDNA, it does not inform functional repair of the initial lesion. However, this method has a logistical flexibility that the reporter assay, which requires thoughtful scheduling to coordinate expression of the restriction enzyme with drug treatment and sample collection, does not. Furthermore, Rad51 staining can be used in preclinical studies as a pharmacodynamic biomarker for HRR inhibition (Fig. 3C)(46) or as a predictive marker for PARP1 response in clinical specimens (76).

The acute effects of radiation on the kinetics and/or dynamics of the DNA damage response in the presence or absence on drug can be interrogated at the individual protein level with laser micro-irradiation studies (77). Briefly, damage is generated by UV laser micro-irradiation in living cells transfected to express a fluorescently tagged protein of interest, such as PARP1, which can be monitored visually in real time (Fig. 4E). Data are typically expressed as changes in mean fluorescence (arbitrary units) at the site of micro-irradiation over time.

Replication Stress

While DSBs are the key indicator of cytotoxicity following ionizing radiation, more recent studies indicate that replication stress can be critical to the efficacy of DDR inhibitor-chemoradiation combination therapies (4). For example, we found that WEE1 inhibitor-mediated replication stress resulting from nucleotide pool depletion, hyperactivation of CDK1 and aberrant DNA replication origin firing, is a key component of AZD1775-mediated radiosensitization (78,79). DDR proteins such as ATR, CHK1 and PARP1 directly regulate not only origin firing (60,80), but also replication fork speed (81,82), direct stabilization of stalled replication forks (83,84) and replication fork restart (83). The potential role(s) of these activities in (chemo)radiosensitization by DDR inhibitors may determine optimal scheduling of combination therapies. Many of the common markers for replication stress, such as pRPA (Ser33) or pan-γH2AX staining, more specifically reflect activation of the ATR signaling pathway, thus limiting their utility for assessing the role of replication stress in ATR inhibitor-mediated radiosensitization. Alternatively, the effects of chemoradiation on replication can be directly quantified with a DNA fiber combing assay.

Stalled Replication Forks – DNA fiber assay

DNA fiber combing was first used to investigate the effects of ionizing radiation on DNA replication by Merrick, Jackson and Diffley in 2004 (85). In this assay, replicating DNA is pulse-labeled by incubating cells sequentially with the thymidine analogs iododeoxyuridine (IdU) and chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU). The labeled DNA is extracted and spread onto slides, and the IdU and CldU tracks are visualized with fluorescent antibodies selective for each analog (Fig. 4F)(86). Assay conditions such as timing and sequence of labeling with radiation and/or drugs can be adapted to assess the effects of a targeted agent on replication rates, origin firing, stalled or slowed forks (Fig. 4G) and/or replication fork restart (reviewed in (87,88)). The technique has the advantage of capturing the heterogeneity of the effects of treatment on individual replication forks, but the analysis is labor intensive. Automation of fiber scoring and analysis will greatly expand the utility of this technique (CASA software, Paul Chastain; http://dnafiberanalysis.com/).

The influence of DNA damage and repair, cell cycle checkpoints, and replication stress on innate immune signaling

The presence of viral DNA in the cytoplasm of host cells triggers an innate immune response that begins with activation of pattern recognition receptor (PRR) proteins such as cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) which specifically detects cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). cGAMP in turn recruits TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) which phosphorylates the adaptor protein STING (Stimulator of Interferon Gene) (89). In addition to viral DNA, it has recently emerged that PRRs also recognizes self cytosolic DNA in the form of either micronuclei (Fig. 4H) or small fragments of dsDNA that arise as a consequence of radiation-induced nuclear DNA damage (90,91). Collectively, activation of PRR pathways converge to induce Type I interferon (T1IFN) expression (Fig. 4I) which has broad immune consequences including antigen presentation, chemokine production and promotion of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity (89,92-94). Given that radiation-induced DNA damage activates innate immune signaling (95), the roles of the DNA damage response in the generation of cytosolic DNA and subsequent activation of innate immune signaling have become an area of intense investigation. As the generation of micronuclei occurs during mitosis, radiation-mediated T1IFN expression is restrained by either G1 or G2 cell cycle arrest (96,97). It is therefore intuitive that DDR inhibitors that abrogate the G1 or G2 checkpoints might be logical strategies for enhancing the radiation-induced innate immune response. Furthermore, as cytosolic DNA is a consequence of nuclear DNA damage and/or replication stress, DDR therapeutics that inhibit DNA repair and/or exacerbate replication stress should also increase cytosolic DNA levels and enhance the activity of this pathway. Our prior studies have shown that inhibition of the DNA damage response does enhance radiation-induced T1IFN responses and confers sensitivity to immunotherapy (92). Taken together, these observations suggest that DDR inhibitors given in combination with radiation are a promising therapeutic strategy for overcoming the immunotherapy resistance common in many cancers (recently reviewed in (98)).

In vivo validation of DDR inhibitor-chemoradiation combination therapy: Immune deficient models

Several types of in vivo tumor models are used to evaluate candidate radiosensitizing agents including heterotopic and orthotopic human cell line and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), and syngeneic or autochthonous murine tumor models (99). Human cell lines are the most adaptable of these models. Heterotopic xenografts, usually implanted bilaterally in the flanks of nude mice, are useful in providing proof-of-principle evidence of both radiosensitizing activity and optimal sequence of administration for the agent under investigation, with both standard of care chemotherapy and a clinically relevant fractionated radiation dosing schedule (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, a retrospective analysis of preclinical and Phase II clinical trial data found that when panels of human xenografts were used, these models could predict Phase II trial results for specific tumor types (non-small cell lung and ovarian cancer) (100).

A limitation of human cell line xenograft models is that they lack genetic diversity, both in terms of tumor cell heterogeneity and inter-patient variability (101). For this reason, PDX models, which better capture human tumor heterogeneity than standard cell line xenografts (12-15), are considered a more clinically relevant system and have been used to assess the chemo- and radiosensitizing activities of a variety of DDR inhibitors (46,102,103). Furthermore, since PDX models maintain many of the genetic and molecular characteristics of the original tumor sample, they can be particularly useful for identifying biomarkers that predict response to therapy (15,104). The lack of institutional standards for characterizing and reporting on PDX models, however, combined with their inherent genetic variability, can make it difficult to replicate published results. To address this issue, the NCI has developed minimum information reporting standards to facilitate more rigorous characterization of PDXs and sharing of this information within the scientific community (105).

In vivo validation of DDR inhibitor-chemoradiation combination therapy: Immune competent models

One of the major limitations of PDX models is that they are by necessity established in immunocompromised mice. However, data from early studies in syngeneic mouse models demonstrated that the immune system can enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy; higher doses of radiotherapy are needed to control tumor growth in immunosuppressed mice compared to immunocompetent mice (106). Subsequent studies found that radiotherapy can modulate both the immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of tumors by triggering release of inflammatory mediators such as T1IFNs, enhancing expression of neoantigens on tumor cells, and increasing immune cell infiltration in the TME (107-109). In the last decade, the clinical success of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), in particular antibodies targeting immunosuppressive factors such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) or cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4), has created ‘indications’ for radiation as an immunostimulatory therapy (109).

Preclinical studies designed to assess the contribution of the immune system to the efficacy of radiation-DDR inhibitor combination therapies, with or without ICIs, on tumor response require immunocompetent mouse models that recapitulate the complexity of immune contexture in the TME. The syngeneic mouse model is the most widely used due to its low cost and short reproductive cycle, as well as the easy ex vivo genetic modification of the tumor cells. Spontaneous, carcinogen-induced, or transgenic mouse cancer cell lines derived from inbred strains (such as C57BL/6, BALB/c, and FVB) are implanted either subcutaneously or orthotopically into wild-type hosts of the same genetic background to establish tumors in mice with an intact immune system. Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) are another valuable platform to investigate the contribution of the immune system to radiotherapy efficacy. These models recapitulate a relatively native tumor microenvironment, as well as a tumorigenic process in which the tumor and the host immune system co-evolve. In addition, GEMM models have been used to establish the importance of direct tumor cell radiosensitization, in contrast to sensitization of the TME, for tumor growth delay in response to radiation and DDR inhibition by comparing tumor cell-specific versus endothelial cell-specific ATM deletion (110).

The ability of radiation to stimulate systemic anti-tumor effects on tumors outside of the radiation field (i.e., abscopal response) is most commonly modeled in the syngeneic bilateral, sub-cutaneous tumor models described above (91). In these experiments, one tumor is irradiated while the tumor outside of the radiation field is monitored for a response. In order to avoid the unirradiated tumor reaching endpoint prior to induction of a systemic immune response by radiation therapy of the primary tumor site (often coupled with immunotherapy), the secondary tumors are often implanted one week later, or from a lower cell number, than the primary tumor (111). Another consideration in these experiments is the scatter dose that the unirradiatied secondary tumor receives, despite shielding. This scatter can be monitored through the use of phantom mouse models with optically stimulated luminescent dosimeters. Results from tumor immunology studies in these models have led to the general consensus that, when used in combination with immunotherapy, higher doses of radiation in fewer fractions (e.g., 7-10 Gy in 3-5 fractions) induce both innate and adaptive immune responses more effectively than conventional fractionated radiation (91,96). The results from our initial studies on the effects of combined radiation and ATM inhibition on tumor immunogenicity support the concept that this is an exciting area of investigation (92). There are many preclinical issues that need to be addressed prior to clinical translation including the optimal radiation dose/fractionation when given in combination with a radiation sensitizer as well as their scheduling with immunotherapy.

Murine models offer tremendous insight into tumor immunology, but there is complexity and diversity in human cancer that is poorly captured in murine models. Additionally, while many similarities are shared, there are areas of divergence between the human and murine immune responses to infection and tumors. There is significant interest in developing humanized mice in which human immune responses against human tumors can be evaluated in a tractable host organism. At present, NOD-SCID- IL-2rγnull or equivalently immunosuppressed murine models are used as hosts (112); a limitation here is that innate immune responses are compromised in many of these models. Further, in all models, human cytokines are frequently required as there is a lack of homology across species in this important class of immune regulatory molecules. Models of engraftment include transplantation of PBMC and human tumor allows the study of activated human CD8 T cells, but these models are limited by graft versus host disease (113). While co-transplantation of hematopoietic precursors in conjunction with human tumors enables a wider of diversity of mature human immune cells to be formed (114), incompatibility with the murine major histocompatibility complex within the thymus limits the generation of robust T cell responses. To overcome this, models have been constructed with human thymus, human hematopoietic stem cells, and human liver (115). It is challenging to acquire enough of each of these tissue types that are matched at major and minor histocompatibility loci to the tumor. Furthermore, it remains challenging to completely model all of the interactions between innate and adaptive immune cells. While PDX humanized mouse models are proving to be a valuable tool for evaluating human anti-tumor immune responses (116), their utility for modeling interactions between radiotherapy and immunotherapy, as well as radiosensitizers, is not yet established.

State of the art treatment planning and radiation delivery

One of the technical limitations of the conventional irradiators used for preclinical research is that they lack the capability for image-guided radiation treatment planning and stereotactic delivery. This is especially important in orthotopic animal tumor models such as those with deep gastrointestinal tumors or gliomas. Furthermore, these fixed-angle irradiators lack the precision required for safe delivery of high dose radiation like that required for stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in tumor immunology models. Relatively recent technological advancements in pre-clinical radiation delivery systems may offer a solution to these problems. These small animal radiation research platforms (SARRP) use cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) to guide delivery of precise multi-angle or ARC treatment plans that recapitulate treatment in the clinical setting (117). These platforms thus allow for the safe delivery of high dose radiation in both orthotopic and immune model systems and minimize normal tissue toxicity (118).

While CBCT imaging is well suited for the visualization of superficial or flank tumors, it is unable to delineate between normal and malignant tissue, especially in the abdominal cavity, and boundaries between internal structures are often unresolvable (119). Iodine-based contrast agents, with or without fiducial marker placement at the time of tumor implantation, can add visual cues for CBCT imaging that help to localize internal structures and approximate tumor placement (120,121). Although contrast agents help to visualize anatomical structures, they do not specifically ‘illuminate’ tumor tissue. To address this issue, bioluminescent imaging (BLI) has been integrated with the SARRP for use with tumor models constructed to express luciferase. Using software that combines 2-dimensional BLI images with mathematical modeling of light transmission through tissue, bioluminescence tomography (BLT) provides a 3D representation of the tumor in situ that allows for the precise targeting of radiation with minimal dose to normal tissues (Fig. 5)(122).

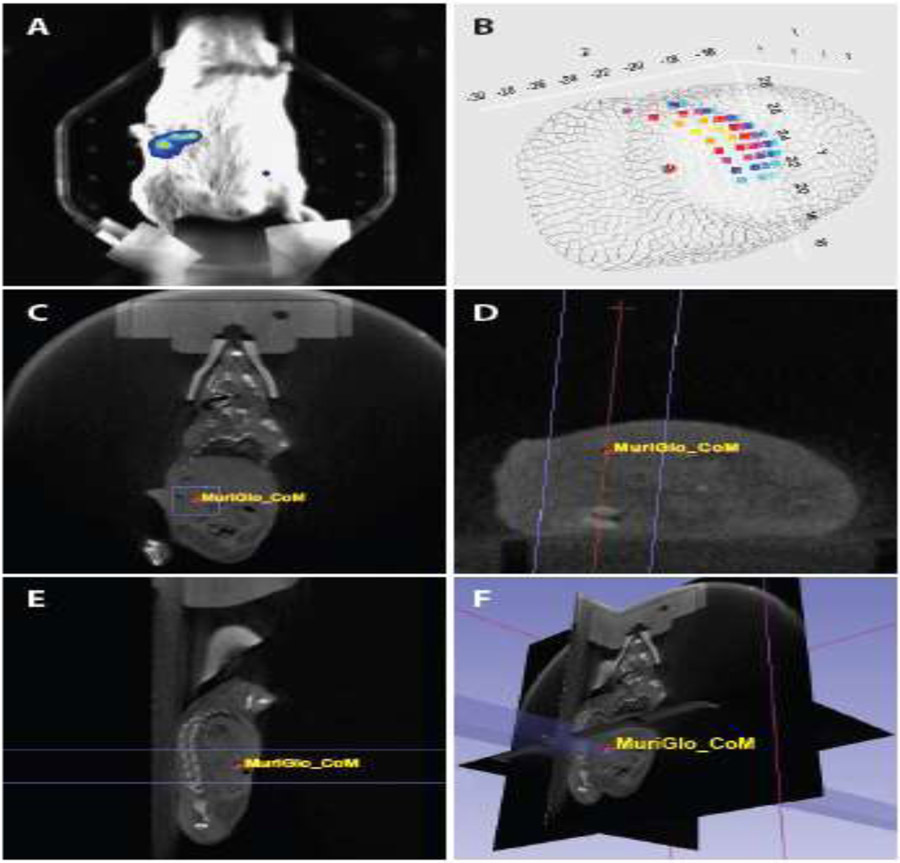

Figure 5. Visualization and treatment of orthotopic pancreatic tumors on the SARRP.

Orthotopic pancreatic tumors were established in FVB/N mice by direct injection of mouse KPC2 pancreatic cancer cells stably expressing pGreenFire luciferase (System Biosciences) into the pancreas. Six days post implant, tumors were visualized with the BLT imaging module (Xstrahl) 10 minutes after IP injection with 4 mg D-Luciferin (A). A BLI signal intensity map was acquired with the MuriGlo software and the center of mass (CoM) calculated and saved as a coordinate to be imported into MuriPlan for directed irradiation on the integrated SARRP platform (B). Representative images of the parallel opposed radiation beams (APPA; shown in purple) and CoM superimposed onto the coronal (C), axial (D), and sagittal (E) CBCT images are shown. A 3D composite of the treatment beam superimposed onto the CBCT images is also shown (F).

In proof-of-concept experiments, we used a SARRP with integrated CBCT/BLT imaging (Xstrahl Medical and Life Sciences) to deliver 8 Gy to orthotopic pancreatic tumors. The software for this BLT imaging system (MuriGlo) has the unique capability to calculate center of mass (CoM), which is a better reference for tumor location than BLI signal intensity (123). The CoM coordinate was imported into treatment planning software (MuriPlan) and used as the tumor isocenter for parallel opposed beam radiation delivery. By integrating CBCT/BLT imaging with the SARRP, this technology permitted the safe and accurate stereotactic delivery of high dose radiation to deep gastrointestinal tumors; a result that would not have been possible on conventional radiation platforms.

While the CBCT/BLT imaging platform is a powerful tool to localize tumor lesions, the MuriGlo software does not provide quantitative emission data such as photons/sec or photons/sec/mm2 that are required for continuous/longitudinal tumor monitoring following therapy. It does, however, include a mouse phantom with a tritium (half-life 12.32. years) luminescent light source for testing purposes. In order to define metrics that can be used as surrogates for longitudinal tumor volume measurements on the SARRP BLT system, a 3D printed black negative mold of the dorsal surface of the bioluminescence phantom with a 1 cm x 1 cm window over the bioluminescence signal region was used. Photon output of the SARRP BLT system was calibrated against standard tumor monitoring bioluminescence systems (e.g., IVIS) for the defined region. The field-of-view (or magnification of the optical system) and aperture settings of the IVIS system were adjusted to obtain average radiance results at different solid angle parameters. The radiant flux and average radiance measurements at the collection solid angle of the MuriGlo system can be interpolated from these measurements and used to transfer the calibration to the MuriGlo system.

Translation of sensitizers to the clinic

Despite the strong logic and preclinical evidence supporting the combination of targeted agents, including DDR inhibitors, with chemoradiation, little progress has been made in obtaining industry support or FDA approval for these combinations. When the FDA granted approval to the combination of a molecularly targeted agent (cetuximab) with radiation in 2006, many predicted that this would be the first of many such approvals. However, since that time, there have been no approved agents. One of the major roadblocks is the lack of support from pharmaceutical companies for radiation-related indications. This is likely due to the current processes for approving new agents (Walker, this issue)(124). The most direct path to FDA approval is to demonstrate in a phase III trial that the new agent is effective as monotherapy in patients with refractory cancer compared with either a “last line” approved agent or best supportive care. This process can take a decade or more between the initial testing of a new agent to the conduct of the pivotal phase III trial that proves efficacy. It is only when the agent has achieved approval that pharma is willing to release the agent for use in combination with (chemo)radiation. At this late stage, and with only a few years left of patent protection, pharma has little incentive to sponsor trials to obtain a radiation-related indication. Moving these combination therapy studies to an earlier phase of drug development, rather than waiting for the pivotal phase III trial to be completed and FDA approval obtained, could impact standard-of-care and outcomes of treatment faster.

One of few ways of advancing radiation-new agent trials earlier in the life cycle of the drug is through NIH SPORE, P01, and R01 support as well as support provided by CTEP and the NCI consortium highlighted in this issue. This is exemplified by our translation of the WEE1 kinase inhibitor adavosertib (AZD1775) from the lab to a phase I/II clinical trial (48). According to the translational pipeline outlined in Figure 3, our preclinical studies showed that adavosertib sensitized to gemcitabine, radiation, and the combination of gemcitabine and radiation (46,98). We translated these findings into a clinical trial using gemcitabine with adavosertib, followed by the adavosertib with gemcitabine and radiation, followed by adavosertib with gemcitabine (48). Compared to historical controls, we saw an increase in overall progression free survival and a median survival of almost 22 months, 50% longer than standard treatment, as well as evidence of target engagement (48). Some of this improvement likely resulted from the adavosertib/gemcitabine treatment underscoring the importance of both local and systemic therapy. Although few other DDR inhibitors have advanced to clinical trials with chemoradiation, early phase trials of PARP inhibitors (veliparib and olaparib) given in combination with temozolomide, gemcitabine, or capecitabine-based chemoradiation in glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, and rectal cancer, respectively, have been completed (125-127).

In addition to the direct anticancer benefits of targeting the DDR, our preclinical studies have revealed the potential anti-tumor immune effects of combined therapy with DDR inhibitors and radiation. Our current work is focused on leveraging the immune response to these treatments to extend local tumor radiosensitization to systemic responses that may be maximized by combination with immunotherapy. These studies are both a natural progression of our prior work and consistent with our longstanding concept of concurrently maximizing systemic treatment while increasing the radiation sensitivity of the primary tumor. It is our goal that the practices outlined in this article and issue will maximize the likelihood of successful translation of chemoradiation sensitizers in the CTEP portfolio from the laboratory to the clinic and ultimately to FDA approval.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the National Cancer Institute staff, especially Drs. Jeff Buchsbaum and Eric Bernhard, for their vision in the initiation and organization of the Radiation U01 Consortium. We thank Steven Kronenberg for his assistance with illustrations in this article.

Disclosures:

MM reports research grants and honoraria from Astra Zeneca.

Grant support:

U01CA216449 (T.S. Lawrence); R01CA240515 (M.A. Morgan); R01CA241764 (A. Rehemtulla); R50CA251960 (L.A. Parsels), and Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA46592; U01CA220714 (H. Willers)

Research data are stored in an institutionary repository and will be shared by request to the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mladenov E, Magin S, Soni A, et al. DNA double-strand break repair as determinant of cellular radiosensitivity to killing and target in radiation therapy. Frontiers in oncology 2013;3:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan MA, Lawrence TS. Molecular pathways: Overcoming radiation resistance by targeting DNA damage response pathways. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2015;21:2898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouw KW, Goldberg MS, Konstantinopoulos PA, et al. DNA damage and repair biomarkers of immunotherapy response. Cancer Discov 2017;7:675–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu H, Swami U, Preet R, et al. Harnessing DNA replication stress for novel cancer therapy. Genes (Basel) 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fokas E, Prevo R, Pollard JR, et al. Targeting atr in vivo using the novel inhibitor ve-822 results in selective sensitization of pancreatic tumors to radiation. Cell Death Dis 2012;3:e441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemasson B, Wang H, Galban S, et al. Evaluation of concurrent radiation, temozolomide and abt-888 treatment followed by maintenance therapy with temozolomide and abt-888 in a genetically engineered glioblastoma mouse model. Neoplasia 2016;18:82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Maybaum J, et al. Improving the efficacy of chemoradiation with targeted agents. Cancer Discov 2014;4:280–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichert ZR, Wahl DR, Morgan MA. Translation of targeted radiation sensitizers into clinical trials. Semin Radiat Oncol 2016;26:261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone HB, Bernhard EJ, Coleman CN, et al. Preclinical data on efficacy of 10 drugradiation combinations: Evaluations, concerns, and recommendations. Transl Oncol 2016;9:46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willers H, Gheorghiu L, Liu Q, et al. DNA damage response assessments in human tumor samples provide functional biomarkers of radiosensitivity. Semin Radiat Oncol 2015;25:237–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleary JM, Aguirre AJ, Shapiro GI, et al. Biomarker-guided development of DNA repair inhibitors. Mol Cell 2020;78:1070–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tentler JJ, Tan AC, Weekes CD, et al. Patient-derived tumour xenografts as models for oncology drug development. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2012;9:338–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidalgo M, Amant F, Biankin AV, et al. Patient-derived xenograft models: An emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discov 2014;4:998–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willey CD, Gilbert AN, Anderson JC, et al. Patient-derived xenografts as a model system for radiation research. Semin Radiat Oncol 2015;25:273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia PL, Miller AL, Yoon KJ. Patient-derived xenograft models of pancreatic cancer: Overview and comparison with other types of models. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman CN, Higgins GS, Brown JM, et al. Improving the predictive value of preclinical studies in support of radiotherapy clinical trials. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016;22:3138–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lama-Sherpa TD, Shevde LA. An emerging regulatory role for the tumor microenvironment in the DNA damage response to double-strand breaks. Mol Cancer Res 2020;18:185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansems M, Span PN. The tumor microenvironment and radiotherapy response; a central role for cancer-associated fibroblasts. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2020;22:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colton M, Cheadle EJ, Honeychurch J, et al. Reprogramming the tumour microenvironment by radiotherapy: Implications for radiotherapy and immunotherapy combinations. Radiat Oncol 2020;15:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tillner F, Thute P, Butof R, et al. Pre-clinical research in small animals using radiotherapy technology--a bidirectional translational approach. Z Med Phys 2014;24:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei D, Parsels LA, Karnak D, et al. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2a radiosensitizes pancreatic cancers by modulating cdc25c/cdk1 and homologous recombination repair. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2013;19:4422–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorecki L, Andrs M, Korabecny J. Clinical candidates targeting the atr-chk1-wee1 axis in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Zhao L, et al. Mechanism of radiosensitization by the chk1/2 inhibitor azd7762 involves abrogation of the g2 checkpoint and inhibition of homologous recombinational DNA repair. Cancer Res 2010;70:4972–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prevo R, Fokas E, Reaper PM, et al. The novel atr inhibitor ve-821 increases sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to radiation and chemotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther 2012;13:1072–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelke CG, Parsels LA, Qian Y, et al. Sensitization of pancreatic cancer to chemoradiation by the chk1 inhibitor mk8776. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2013;19:4412–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnieh FM, Loadman PM, Falconer RA. Progress towards a clinically-successful atr inhibitor for cancer therapy. Current Research in Pharmacology and Drug Discovery 2021;2:100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyati S, Young G, Ross BD, et al. Quantitative and dynamic imaging of atm kinase activity by bioluminescence imaging. Methods Mol Biol 2017;1599:97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galban S, Jeon YH, Bowman BM, et al. Imaging proteolytic activity in live cells and animal models. PLoS One 2013;8:e66248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Awadia S, Delaney A, et al. Uae1 inhibition mediates the unfolded protein response, DNA damage and caspase-dependent cell death in pancreatic cancer. Transl Oncol 2020;13:100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puck TT, Marcus PI, Cieciura SJ. Clonal growth of mammalian cells in vitro; growth characteristics of colonies from single hela cells with and without a feeder layer. J Exp Med 1956;103:273–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, et al. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc 2006;1:2315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fertil B, Dertinger H, Courdi A, et al. Mean inactivation dose: A useful concept for intercomparison of human cell survival curves. Radiation research 1984;99:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahn J, Tofilon PJ, Camphausen K. Preclinical models in radiation oncology. Radiat Oncol 2012;7:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brix N, Samaga D, Hennel R, et al. The clonogenic assay: Robustness of plating efficiency-based analysis is strongly compromised by cellular cooperation. Radiat Oncol 2020;15:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steel GG, Peckham MJ. Exploitable mechanisms in combined radiotherapy-chemotherapy: The concept of additivity. Int J Radiat Onc Biol Phys 1979;5:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seiwert TY, Salama JK, Vokes EE. The concurrent chemoradiation paradigm--general principles. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2007;4:86–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steel GG, Peckham MJ. Exploitable mechanisms in combined radiotherapy-chemotherapy: The concept of additivity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1979;5:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasch CA, Favreau PF, Yueh AE, et al. Patient-derived cancer organoid cultures to predict sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiation. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2019;25:5376–5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dreyer SB, Upstill-Goddard R, Paulus-Hock V, et al. Targeting DNA damage response and replication stress in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2021;160:362–377 e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nunez FJ, Mendez FM, Kadiyala P, et al. Idh1-r132h acts as a tumor suppressor in glioma via epigenetic up-regulation of the DNA damage response. Sci Transl Med 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou W, Yao Y, Scott AJ, et al. Purine metabolism regulates DNA repair and therapy resistance in glioblastoma. Nat Commun 2020;11:3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eke I, Cordes N. Radiobiology goes 3d: How ecm and cell morphology impact on cell survival after irradiation. Radiother Oncol 2011;99:271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boucherit N, Gorvel L, Olive D. 3d tumor models and their use for the testing of immunotherapies. Frontiers in Immunology 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iliakis G, Wang Y, Guan J, et al. DNA damage checkpoint control in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Oncogene 2003;22:5834–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Fan S, Eastman A, et al. Ucn-01: A potent abrogator of g2 checkpoint function in cancer cells with disrupted p53. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996;88:956–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kausar T, Schreiber JS, Karnak D, et al. Sensitization of pancreatic cancers to gemcitabine chemoradiation by wee1 kinase inhibition depends on homologous recombination repair. Neoplasia 2015;17:757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang L, Shen C, Pettit CJ, et al. Wee1 kinase inhibitor azd1775 effectively sensitizes esophageal cancer to radiotherapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2020;26:3740–3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cuneo KC, Morgan MA, Sahai V, et al. Dose escalation trial of the wee1 inhibitor adavosertib (azd1775) in combination with gemcitabine and radiation for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2643–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Do K, Wilsker D, Ji J, et al. Phase i study of single-agent azd1775 (mk-1775), a wee1 kinase inhibitor, in patients with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3409–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leijen S, van Geel RM, Pavlick AC, et al. Phase i study evaluating wee1 inhibitor azd1775 as monotherapy and in combination with gemcitabine, cisplatin, or carboplatin in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:4371–4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eastman AE, Guo S. The palette of techniques for cell cycle analysis. FEBS Lett 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ivashkevich A, Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, et al. Use of the gamma-h2ax assay to monitor DNA damage and repair in translational cancer research. Cancer Lett 2012;327:123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LoRusso PM, Li J, Burger A, et al. Phase i safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of the poly(adp-ribose) polymerase (parp) inhibitor veliparib (abt-888) in combination with irinotecan in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016;22:3227–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas A, Redon CE, Sciuto L, et al. Phase i study of atr inhibitor m6620 in combination with topotecan in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1594–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goodarzi AA, Jeggo PA. Irradiation induced foci (irif) as a biomarker for radiosensitivity. Mutat Res 2012;736:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sak A, Stuschke M. Use of gammah2ax and other biomarkers of double-strand breaks during radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2010;20:223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ward IM, Chen J. Histone h2ax is phosphorylated in an atr-dependent manner in response to replicational stress. J Biol Chem 2001;276:47759–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogakou EP, Nieves-Neira W, Boon C, et al. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of h2ax histone at serine 139. J Biol Chem 2000;275:9390–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Feraudy S, Revet I, Bezrookove V, et al. A minority of foci or pan-nuclear apoptotic staining of gammah2ax in the s phase after uv damage contain DNA double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:6870–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Syljuasen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, et al. Inhibition of human chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of atr targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:3553–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parsels LA, Parsels JD, Tanska DM, et al. The contribution of DNA replication stress marked by high-intensity, pan-nuclear gammah2ax staining to chemosensitization by chk1 and wee1 inhibitors. Cell Cycle 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solier S, Pommier Y. The nuclear gamma-h2ax apoptotic ring: Implications for cancers and autoimmune diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014;71:2289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Josse R, Martin SE, Guha R, et al. Atr inhibitors ve-821 and vx-970 sensitize cancer cells to topoisomerase i inhibitors by disabling DNA replication initiation and fork elongation responses. Cancer Res 2014;74:6968–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parsels LA, Engelke CG, Parsels J, et al. Combinatorial efficacy of olaparib with radiation and atr inhibitor requires parp1 protein in homologous recombination proficient pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fairbairn DW, Olive PL, O'Neill KL. The comet assay: A comprehensive review. Mutat Res 1995;339:37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olive PL, Banath JP, Durand RE. Heterogeneity in radiation-induced DNA damage and repair in tumor and normal cells measured using the "comet" assay. Radiation research 1990;122:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moller P, Azqueta A, Boutet-Robinet E, et al. Minimum information for reporting on the comet assay (mirca): Recommendations for describing comet assay procedures and results. Nat Protoc 2020;15:3817–3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collins AR, El Yamani N, Lorenzo Y, et al. Controlling variation in the comet assay. Front Genet 2014;5:359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moller P, Loft S. Statistical analysis of comet assay results. Front Genet 2014;5:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McMillan MT, Lawrence TS, Morgan MA. Targeting the DNA damage response for radiosensitization. In: Willers H, Eke I, editors. Molecular targeted radiosensitizers. Cancer drug discovery and development.: Humana, Cham;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woodbine L, Gennery AR, Jeggo PA. The clinical impact of deficiency in DNA nonhomologous end-joining. DNA repair 2014;16:84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Groth P, Orta ML, Elvers I, et al. Homologous recombination repairs secondary replication induced DNA double-strand breaks after ionizing radiation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:6585–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krajewska M, Fehrmann RS, Schoonen PM, et al. Atr inhibition preferentially targets homologous recombination-deficient tumor cells. Oncogene 2015;34:3474–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of brca2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(adp-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005;434:913–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pierce AJ, Johnson RD, Thompson LH, et al. Xrcc3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev 1999;13:2633–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Castroviejo-Bermejo M, Cruz C, Llop-Guevara A, et al. A rad51 assay feasible in routine tumor samples calls parp inhibitor response beyond brca mutation. EMBO Mol Med 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kong X, Wakida NM, Yokomori K. Application of laser microirradiation in the investigations of cellular responses to DNA damage. Frontiers in Physics 2021;8. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beck H, Nahse-Kumpf V, Larsen MS, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase suppression by wee1 kinase protects the genome through control of replication initiation and nucleotide consumption. Mol Cell Biol 2012;32:4226–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parsels LA, Karnak D, Parsels JD, et al. Parp1 trapping and DNA replication stress enhance radiosensitization with combined wee1 and parp inhibitors. Mol Cancer Res 2018;16:222–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moiseeva TN, Yin Y, Calderon MJ, et al. An atr and chk1 kinase signaling mechanism that limits origin firing during unperturbed DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:13374–13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Petermann E, Woodcock M, Helleday T. Chk1 promotes replication fork progression by controlling replication initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:16090–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maya-Mendoza A, Moudry P, Merchut-Maya JM, et al. High speed of fork progression induces DNA replication stress and genomic instability. Nature 2018;559:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bryant HE, Petermann E, Schultz N, et al. Parp is activated at stalled forks to mediate mre11-dependent replication restart and recombination. EMBO J 2009;28:2601–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Couch FB, Bansbach CE, Driscoll R, et al. Atr phosphorylates smarcal1 to prevent replication fork collapse. Genes Dev 2013;27:1610–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Merrick CJ, Jackson D, Diffley JF. Visualization of altered replication dynamics after DNA damage in human cells. J Biol Chem 2004;279:20067–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwab RA, Niedzwiedz W. Visualization of DNA replication in the vertebrate model system dt40 using the DNA fiber technique. J Vis Exp 2011. :e3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quinet A, Carvajal-Maldonado D, Lemacon D, et al. DNA fiber analysis: Mind the gap! Methods Enzymol 2017;591:55–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Techer H, Koundrioukoff S, Azar D, et al. Replication dynamics: Biases and robustness of DNA fiber analysis. J Mol Biol 2013;425:4845–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen Q, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Regulation and function of the cgas-sting pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol 2016;17:1142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Durante M, Formenti SC. Radiation-induced chromosomal aberrations and immunotherapy: Micronuclei, cytosolic DNA, and interferon-production pathway. Frontiers in oncology 2018;8:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vanpouille-Box C, Alard A, Aryankalayil MJ, et al. DNA exonuclease trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat Commun 2017;8:15618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Q, Green MD, Lang X, et al. Inhibition of atm increases interferon signaling and sensitizes pancreatic cancer to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Res 2019;79:3940–3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, et al. Sting-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type i interferon-dependent antitumor immunity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity 2014;41:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, et al. Type i interferons in anticancer immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mackenzie KJ, Carroll P, Martin CA, et al. Cgas surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature 2017;548:461–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Harding SM, Benci JL, Irianto J, et al. Mitotic progression following DNA damage enables pattern recognition within micronuclei. Nature 2017;548:466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen J, Harding SM, Natesan R, et al. Cell cycle checkpoints cooperate to suppress DNA- and rna-associated molecular pattern recognition and anti-tumor immune responses. Cell Rep 2020;32:108080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Parsels LA, Parsels JD, Tanska DM, et al. The contribution of DNA replication stress marked by high-intensity, pan-nuclear gammah2ax staining to chemosensitization by chk1 and wee1 inhibitors. Cell Cycle 2018;17:1076–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Talmadge JE, Singh RK, Fidler IJ, et al. Murine models to evaluate novel and conventional therapeutic strategies for cancer. Am J Pathol 2007;170:793–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Voskoglou-Nomikos T, Pater JL, Seymour L. Clinical predictive value of the in vitro cell line, human xenograft, and mouse allograft preclinical cancer models. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2003;9:4227–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Feldmann G, Rauenzahn S, Maitra A. In vitro models of pancreatic cancer for translational oncology research. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2009;4:429–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pokorny JL, Calligaris D, Gupta SK, et al. The efficacy of the wee1 inhibitor mk-1775 combined with temozolomide is limited by heterogeneous distribution across the blood-brain barrier in glioblastoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Venkatesha VA, Parsels LA, Parsels JD, et al. Sensitization of pancreatic cancer stem cells to gemcitabine by chk1 inhibition. Neoplasia 2012;14:519–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vaubel RA, Tian S, Remonde D, et al. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of a broad panel of patient-derived xenografts reflects the diversity of glioblastoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2020;26:1094–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meehan TF, Conte N, Goldstein T, et al. Pdx-mi: Minimal information for patient-derived tumor xenograft models. Cancer Res 2017;77:e62–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stone HB, Peters LJ, Milas L. Effect of host immune capability on radiocurability and subsequent transplantability of a murine fibrosarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1979;63:1229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Patel SA, Minn AJ. Combination cancer therapy with immune checkpoint blockade: Mechanisms and strategies. Immunity 2018;48:417–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD, et al. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18:313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Weichselbaum RR, Liang H, Deng L, et al. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: A beneficial liaison? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Torok JA, Oh P, Castle KD, et al. Deletion of atm in tumor but not endothelial cells improves radiation response in a primary mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2019;79:773–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Rodriguez I, Garasa S, et al. Abscopal effects of radiotherapy are enhanced by combined immunostimulatory mabs and are dependent on cd8 t cells and crosspriming. Cancer Res 2016;76:5994–6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, et al. Nod/scid/gamma(c)(null) mouse: An excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood 2002;100:3175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.King MA, Covassin L, Brehm MA, et al. Human peripheral blood leucocyte non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain gene mouse model of xenogeneic graft-versus-host-like disease and the role of host major histocompatibility complex. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;157:104–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Strowig T, et al. Human hemato-lymphoid system mice: Current use and future potential for medicine. Annu Rev Immunol 2013;31:635–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Melkus MW, Estes JD, Padgett-Thomas A, et al. Humanized mice mount specific adaptive and innate immune responses to ebv and tsst-1. Nat Med 2006;12:1316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Choi Y, Lee S, Kim K, et al. Studying cancer immunotherapy using patient-derived xenografts (pdxs) in humanized mice. Exp Mol Med 2018;50:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ghita M, Brown KH, Kelada OJ, et al. Integrating small animal irradiators withfunctional imaging for advanced preclinical radiotherapy research. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lang X, Green MD, Wang W, et al. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy promote tumoral lipid oxidation and ferroptosis via synergistic repression of slc7a11. Cancer Discov 2019;9:1673–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kersemans V, Beech JS, Gilchrist S, et al. An efficient and robust mri-guided radiotherapy planning approach for targeting abdominal organs and tumours in the mouse. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Yaffe H, et al. Non-invasive targeted hepatic irradiation and spect/ct functional imaging to study radiation-induced liver damage in small animal models. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ford EC, Achanta P, Purger D, et al. Localized ct-guided irradiation inhibits neurogenesis in specific regions of the adult mouse brain. Radiation research 2011;175:774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhang B, Wang KK, Yu J, et al. Bioluminescence tomography-guided radiation therapy for preclinical research. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;94:1144–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tuli R, Armour M, Surmak A, et al. Accuracy of off-line bioluminescence imaging to localize targets in preclinical radiation research. Radiation research 2013;179:416–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ahmad SS, Crittenden MR, Tran PT, et al. Clinical development of novel drug-radiotherapy combinations. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2019;25:1455–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]