Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to increase suicidal behavior. However, data available to date are inconsistent. This study examines suicidal thoughts and behaviors and suicide trends in 2020 relative to 2019 as an approximation to the impact of the pandemic on suicidal behavior and death in the general population of Catalonia, Spain. Data on suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (STBs) and suicidal mortality were obtained from the Catalonia Suicide Risk Code (CSRC) register and the regional police, respectively. We compared the monthly crude incidence of STBs and suicide mortality rates of 2020 with those of 2019. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to assess changes in trends over time during the studied period. In 2020, 4,263 consultations for STBs and 555 suicide deaths were registered in Catalonia (approx. 7.5 million inhabitants). Compared to 2019, in 2020 STBs rates decreased an average of 6.3% (incidence rate ratio, IRR=0.94, 95% CI 0,90–0,98) and overall suicide death rates increased 1.2% (IRR=1.01, 95% CI 0.90–1.13). Joinpoint regression results showed a substantial decrease in STBs rates with a monthly percent change (MPC) of -22.1 (95% CI: -41.1, 2.9) from January-April 2020, followed by a similar increase from April-July 2020 (MPC=24.7, 95% CI: -5.9, 65.2). The most restrictive measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic reduced consultations for STBs, suggesting that the “stay at home” message may have discouraged people from contacting mental health services. STBs and mortality should continue to be monitored in 2021 and beyond to understand better the mid-to-long term impact of COVID-19 on suicide trends.

Keywords: COVID-19 outbreak, Suicide, Suicidal behavior, Suicide death

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on mental health in the general population, leading to increased anxiety, depression, and stress around the world (Xiong et al., 2020). The mental health consequences of the pandemic appear to be greater among vulnerable populations, including minorities, individuals with previously existing mental health disorders (Hao et al., 2020; Solé et al., 2021), and people with financial stress and unemployment (Gunnell et al., 2020). McIntyre and Lee (2020) also raised concerns about the impact of the COVID-19 on established risk factors for suicide, including uncertainty of the job market, lack of psychological and psychiatric first aid interventions, and social isolation. During the pandemic, high levels of suicidal ideation have been reported in Spain, both amongst healthcare workers (Mortier et al., 2021a) and in the general adult population (Mortier et al., 2021b).

In addition to its impact on mental health, the pandemic also changed how health care is provided. In many countries, people were advised to seek professional help online rather than in person, thus causing a shift towards virtual care (Webster, 2020). However, the impact of this shift on people seeking help is yet not well-understood. On the one hand, telemedicine has the potential to increase access to health care cost-effectively. On the other hand, there are numerous barriers to online health care, including limited access to computers and the internet or a lack of familiarity and comfort with this approach. As a result, many people—particularly older individuals and those with limited resources— might not utilize this route to seek help. In Spain and Italy, guidelines for managing mental health issues during the pandemic called for the greater utilization of online mental health services and, whenever possible, home care of patients with mental disorders rather than hospitalization (D'Agostino et al., 2020; Vieta et al., 2020).

Studies published before the current pandemic suggest that suicide rates might be sensitive to disease outbreaks and macroeconomic indicators, particularly unemployment levels (Chang et al., 2009; McIntyre and Lee, 2020; Reeves et al., 2014; Stuckler et al., 2009). For example, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak and the 2008 recession were associated with an increased risk of completed suicide, especially in older adults (Chan et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2013). On the contrary, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis examining suicide, self-harm, and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious diseases epidemics from 1910 to date concluded that the evidence regarding the association between epidemics and increased suicidal thoughts or death is weak (Rogers et al., 2021). One possible explanation for these mixed findings is that these outbreaks may have a delayed effect on suicide and STBs after an initial period of reduced risk (Leaune et al., 2020; Rück et al., 2020).

Regarding suicide risk, the current pandemic seems to be a “perfect storm” scenario in which risk factors for suicide are enhanced while protective factors such as access to mental health care are diminished. Although an increase in suicidal behavior would be expected, the data reported to date suggest that suicide rates have remained stable during the pandemic and may have even fallen. Preliminary data from Norway indicate that suicide rates did not rise during the first three months of the pandemic (Qin and Mehlum, 2021). Similar findings were reported by Rück et al. (2020) in Sweden, by Appleby (2021) in England, and by Leske and colleagues (Leske et al., 2021) in Australia. Pirkis et al. (2021) analyzed preliminary data from 21 countries, including high and upper-middle-income countries. Overall, their findings suggest that suicide numbers remained primarily unchanged or even declined in the early months of 2020. However, some specific regions or countries showed the opposite effect (i.e., an increase in suicide rates was suggested in Japan; (Sakamoto et al., 2021)). Similar to the other studies mentioned above, the data analyzed in the study by Pirkis et al. (2021) came from the early months of the pandemic. As a result, their findings likely underestimate the true impact of COVID-19 in those countries on suicide rates, especially the influence of restrictive measures and lockdowns.

In Catalonia, an autonomous region of Spain with approximately 7.5 million inhabitants, the first case of COVID-19 was detected on February 25, 2020. The most severe restrictions were put in place from March 14 to June 21 of that year, with measures that included a nearly complete lockdown, prohibition of social and religious gatherings, closure of schools/universities, bars, restaurants, sports facilities, and non-essential shops. Some of these restrictions were removed or at least softened in stages starting in May 2020. Pre-pandemic data in Catalonia show that suicide is the second cause of preventable death in the Catalan general population and the leading cause of death in people from 25 to 44 years of age (Salut, 2014). In 2014, the Catalan government developed the Catalonia Suicide Risk Code (CSRC), a secondary prevention program for suicide with two major components: a local registry of suicidal behavior and a care pathway for individuals at high risk (Pérez et al., 2020).

The present study aimed to examine suicide trends in Catalonia during the COVID-19 pandemic and present data on a longer time frame interval than provided in the earlier studies to better understand the overall impact of the pandemic on suicide. As a result, we present data on suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (STBs; (Silverman et al., 2007) and suicide mortality between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020, which are compared with the year 2019, an entire pre-pandemic period.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

We used data obtained from the CSRC register, which contains all episodes of STBs identified by healthcare resources in Catalonia. The CSRC is a comprehensive program developed by a board of mental health experts linked to the Catalan Ministry of Health meant to reduce suicide rates. Every individual identified by any health professional (e.g., GP, nurse, mental health professional) with a suspected high risk of suicide is referred to the closest emergency ward for a comprehensive suicide risk evaluation. The level of risk is determined by the six-item suicidality module of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) and the clinical judgment of the psychiatrist. Inclusion criteria consists of female/male of any age, residence in Catalonia, and scores > 10 on the suicidality module of the MINI and/or high risk according to the clinical judgment of the psychiatrist. Patients at high risk are registered and enrolled in the program, which provides early access to specialized mental health care. A detailed description of the SCRS procedures can be found elsewhere (Pérez et al., 2020). The present study reports only the total number of cases included in the CSRC register between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2020. Suicide mortality data from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020, were obtained from the regional police department. These data reflect the total number of suicide deaths with police involvement in 2019 and 2020. For this study, we report data of individuals above 18 years of age.

2.2. Analysis

Monthly crude incidence rates (per 100.000 person-months) and corresponding 95% CI were calculated for the studied period, for STBs and deaths separately. We estimated crude incidence rate ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals comparing the monthly incidence rate of 2019 with the corresponding month in 2020. For STBs, calculations were also stratified by sex. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to assess trends over time, where the months (i.e., joinpoints) when changes occurred in the linear slope of the temporal trend were identified. The analysis starts with the minimum number of joinpoints (i.e., 0 joinpoints, corresponding to a straight line) and tests for model fit with a maximum of 6 joinpoints. Tests of significance use a Monte Carlo permutation method (Kim et al., 2000). The magnitude of increase/decrease observed in each interval is estimated as the Monthly Percent Change (MPC). We used The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results statistical software (Joinpoint Regression Program, version 4.9.0) to assess the joinpoints, the trends, and monthly percent changes.

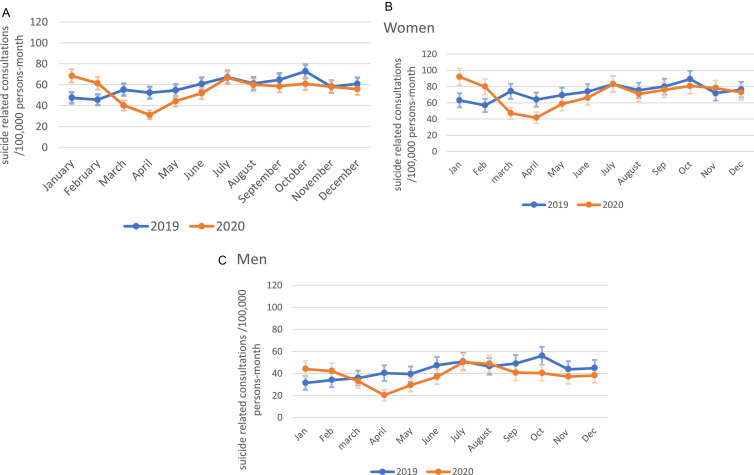

3. Results

In 2020, the number of suicide-related events registered in the CSRC was 4263, 5% less than those in 2019 (Supplementary Table 1). Fig. 1. A presents the monthly crude incidence rates (and 95% CI) of STBs registered in 2020 and 2019. A decrease is observed for March, April, and May 2020 compared with the same months of 2019, with monthly IRR in March through June ranging from 0,59 to 0,85. This pattern was also observed in results for men and women, separately. Additionally, among males, there was a decrease in incidence rates of STB during fall 2020 when the second wave took place, with monthly incidence rate ratios from august below 0.85, and the lowest IRR observed in October (IRR=0.72, 95% CI: 0,57–0.91) (Fig. 1.B and 1.C, and Supplementary Table 2). No other significant differences were found. Results were similar for women and men (Fig. 1. B and 1. C, and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

(A) Suicide thoughts and behaviors incidence (100000 persons-month) in Catalonia 2019–2020. Crude rates with 95% CI. (both genders) (B). Suicide related consultations in Catalonia 2019–2020 by gender. Crude rates with 95% CI (women). (C). Suicide related consultations in Catalonia 2019–2020 by gender. Crude rates with 95% CI (men).

In total, 2788 women and 1475 men engaged in STBs during 2020. Relatively to 2019, the total number of consultations due to STBs by men in 2020 decreased 9.7%, while consultations by women decreased 2.2% (see Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 1. B and 1. C).

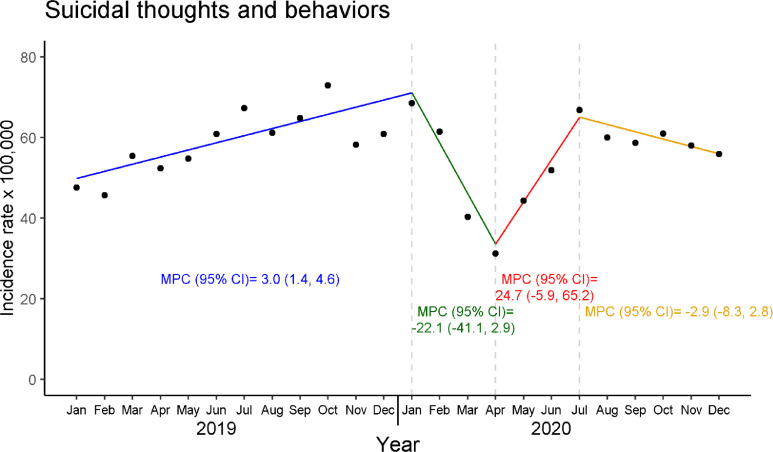

Fig. 2 shows the whole series of STBs with results from the joinpoint regression. The model that best summarizes the behavior of the data trend is the one with three joinpoints, estimated at January 2020, April 2020, and July 2020. From January 19 to January 20, the estimated MPC=3.0 (95% CI: 1.4, 4.6), from January 20 to April 20 MPC=.−22.1 (95% CI: −41.1, 2.9), from April 20 to July 20 MPC=24.7 (95% CI: −5.9, 65.2), and from Jul 20 to Dec 20 MPC=−2.9 (95% CI: −8.3, 2.8).

Fig. 2.

Suicide-related thoughts and behaviors incidence (100000 persons-month) in Catalonia, 2019–2020, crude rates and estimated monthly percent changes from Joinpoint regression analysis.

MPC: Monthly percent rate; CI: Confidence intervalDotted gray lines indicate the location of the three joinpoints from the final selected model; coloured segments represent MPC for each section of the plot determined by the joinpoints.

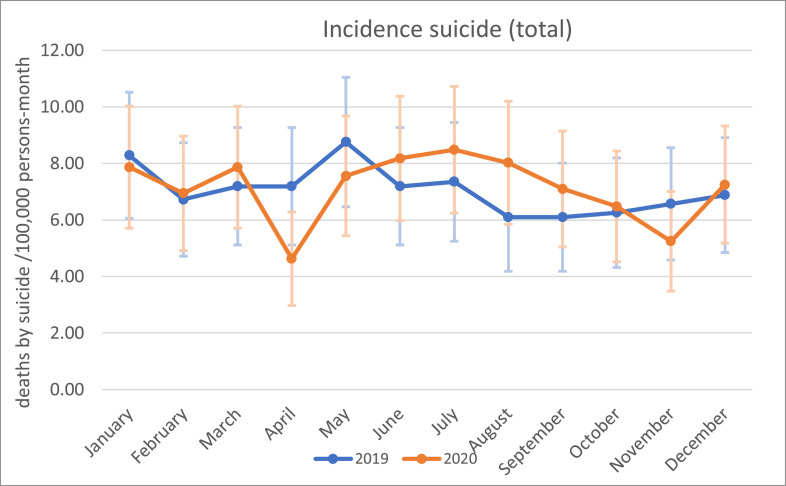

Fig. 3 shows monthly incidence rates of deaths by suicide in Catalonia for 2019 and 2020 and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (see also Supplementary Table 3). Five hundred forty-one suicide deaths were registered in 2019, while 555 deaths by suicide were registered in 2020. Compared with the same month in 2019, a decrease was observed in April 2020 (IRR=0.64; 95% CI: 0.41, 1.02), and May (IRR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.59, 1.27). Between June and September, subsequent increases in 2020 monthly rates were also observed (IRR range from 1.14 to 1.31).

Fig. 3.

Suicide death trends in Catalonia 2019–2020. Crude rates with 95% CI.

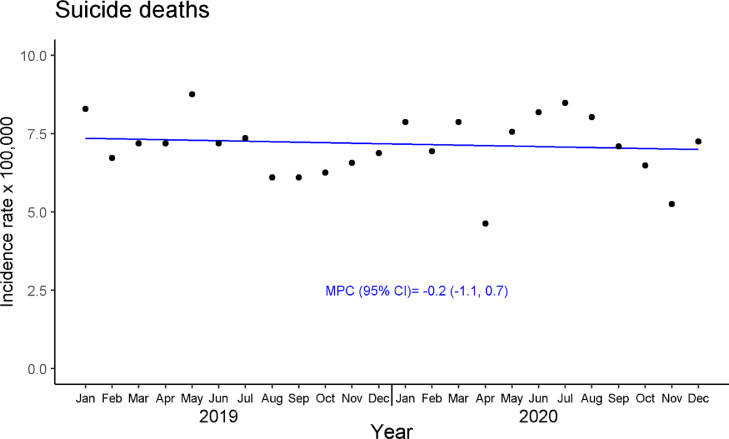

For completed suicides ( Fig. 4 ), the joinpoint model that best summarizes the behavior of the data trend is the one with 0 joinpoints (i.e., corresponding to a straight line), with an MPC= −0.2 (95% CI: −1.1, 0.7).

Fig. 4.

Crude incidence rates and estimated monthly percent change from Joinpoint regression analysis of suicide deaths in Catalonia, 2019–2020

MPC: Monthly percent change; CI: Confidence Interval

coloured segments represent MPC for each section of the plot determined by the Joinpoint analysis where no Joinpoint are selected.

4. Discussion

Based on the data obtained from the CSRC register and the regional police department, we found that whereas STBs significantly decreased during severe lockdown restrictions (March, April, and May 2020) in comparison to 2019, trends of suicide death remained unchanged. Our findings align with those reported by Pirkis et al. (2021), who evaluated suicidal behavior in the first months of the pandemic in 21 countries, concluding that suicide rates appear to have fallen slightly or were unchanged.

In comparison to 2019 rates, we found that fewer patients sought emergency psychiatric care for STBs, especially in the period of severe restrictions, including complete lockdown. Data reported by Cobo et al. (Cobo et al., 2021) supports this finding. In that study, a smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment was used to track the wish to die in patients with a history of STBs during the lockdown and find an unexpected decrease in the wish to die. However, other studies as for example the one conducted by Sakamoto and colleagues in Japan, who found an increase in suicide rates during the first month of the pandemic, especially in young women (Sakamoto et al., 2021). A substantial rise in STBs was found between May and July 2020. Whether these variations respond to random variation or not is uncertain, as we discuss below. Interestingly, the most significant variation compared to 2019 was observed in April 2020, coinciding with the onset of the pandemic and lasting during the phase of highly restrictive measures. This finding is consistent with the trends observed in other parts of the world (Holland et al., 2021; Thornton, 2020), indicating fewer emergency department consultations overall (not only for mental health issues).

The observed decrease in STB-related consultations in our study might be due to the restrictive measures. Our data trend showed three joinpoints that coincide with the different periods of restrictions. Two previous studies also reported a significant reduction in psychiatric emergency consultations during lockdown (Dvorak et al., 2021; Pignon et al., 2020). Pignon and colleagues (2020) observed a 42.6% reduction in suicide attempts in the first four weeks of the lockdown in France compared to the same period in 2019. In that same country, hospitalizations for suicidal behavior decreased, but the proportion of severe cases remained the same or even increased in some of the post-COVID periods analyzed (Olié et al., 2021). Although visits to emergency departments decreased in the USA, the ratio of visits regarding suicide attempts increased (Holland et al., 2021). A study conducted in Madrid, Spain (Hernández-Calle et al., 2020) found a continuous decline in emergency consultations for STBs every week after the COVID-19 outbreak. However, it is essential to emphasize that those data are based on an early analysis of the pandemic data. The decline in consultations for STBs could be attributed to numerous factors, including the implementation of telemedicine (Kavoor et al., 2020), the increase in coping strategies that sometimes follows significant stressors (Bonanno et al., 2007; Pfefferbaum and North, 2020), the reduction in daily life stressors related to staying at home, fear of infection in emergency wards, and compliance with lockdown orders (Hernández-Calle et al., 2020). In the latter case, it is unclear whether lockdowns decreased STBs or dissuaded people from consulting for STBs due to the perceived need to comply with the lockdown measures or fearing to go to the hospital due to the risk of infection.

In both 2019 and 2020, most STBs were made by women, which is consistent with previous data from the CSRC (Pérez et al., 2020) and might reflect gender differences in suicide intend, being more frequent among women (Freeman et al., 2017). Unfortunately, our data do not break down suicide deaths by sex, and therefore we do not know whether suicide deaths among women increased during the pandemic, as other authors have found (Nomura et al., 2021).

Overall, our findings are consistent with other reports, suggesting that the pandemic did not significantly impact STBs, at least during the nine months after the outbreak and implementation of governmental restrictions (Pirkis et al., 2021; Qin and Mehlum, 2021). For some people, the pandemic outbreak could have resulted in more time spent with their loved ones, an increased feeling of peer support, less work pressure, and more time to rest (Pompili, 2021). While some actions may have strengthened social cohesion and support, lockdowns and quarantines may have had the opposite effect, increasing risk factors for suicide such as isolation and social distancing (Courtet and Olié, 2021; Zalsman, 2020). Despite this, STBs and suicide rates should be contextualized on the long-term socioeconomic impact of the pandemic, and efforts on suicide prevention need to continue. A critical aspect of our study is that we report data on suicidal behaviors and suicide deaths in contrast to previous studies. We believe that this provides a more detailed picture of the post-pandemic months. Suicide mortality is known to be influenced by economic crises, isolation, and unemployment; however, perhaps more time is needed to observe the impact of COVID-19 on those variables, which may later increase suicide mortality rates.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not stratify patient data by their sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity, or income levels), nor we examined potential differences in STBs between individuals with and without pre-existing psychiatric conditions. In addition, COVID-19 survivors have been identified as a high-risk group for developing psychiatric disorders (Oronsky et al., 2021). These factors could influence STBs and should be addressed in future work to determine their actual impact on suicide trends. Second, the present results combine suicide-related thoughts and behaviors. Future studies could address suicidal thoughts and behaviors separately to determine if the pandemic had a differential impact on each of those. Third, the suicide death rates presented here were only those with police department involvement. Some previous studies have shown that suicide statistics are not always reliable, as some suicides might be classified into unspecific categories, such as “accidents” or “unknown cause of mortality” (Tøllefsen et al., 2015). In recent work, Snowdon compared the number of suicide deaths in Spain between 2014 and 2018, England and Wales, concluding that Spain's crude suicide rate was low compared to other nations, suggesting that they might reflect “hidden suicide” (Snowdon, 2021). In this context, and although the register of the regional police department is reliable and similar to the suicide rates provided by the National Institute of Statistics (Fernández-Prieto et al., 2021), data from other sources, including the forensic autopsies, would be needed to have more accurate estimates of suicide death.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on individuals and specific communities at risk and society. Although high-vulnerable groups (e.g., people with pre-existing mental disorders, PTSD, complicated grief, covid-19 survivors) deserve special attention, the pandemic has also negatively affected public health care in general. While some of the negative consequences of the pandemic are already tangible, however, the long-term effects remain uncertain. The amount of reports showing lasting symptoms after COVID-19 remission keeps growing, revealing a worrisome and long-lasting impact of the disease on mental health (Llach and Vieta, 2021). As the mid-to-long-term consequences of the pandemic start to unfold, it will be crucial to monitor real-time data on suicidal behavior to ensure access to evidence-based mental health care. A comprehensive approach to suicide prevention should include universal prevention strategies oriented to increase public awareness and decrease mental health stigma and secondary prevention initiatives. Telemedicine and the use of web-based resources are essential to reach large populations of different ages and backgrounds. On the other hand, secondary prevention strategies should include specific psychotherapeutic approaches for suicide as dialectical behavioral therapy (Linehan et al., 2015), brief interventions, and active follow-up of those at high risk (Inagaki et al., 2019). Initiatives like the CSRC that provide a systematic approach to the care of individuals at risk, shortening the time elapsed between the initial contact with the health care system and specialized care, are especially needed in the post-pandemic context. Lastly, effective prevention strategies should involve different stakeholders (Hegerl et al., 2009) and provide health care workers training in evidence-based-suicide prevention strategies that can be implemented in routine clinical activities (Courtet and Olié, 2021). Challenging times lie ahead, and suicide prevention should be of high priority for policymakers and mental health providers.

Contributors

Initial draft of the manuscript: VP and ME. Data analysis: GV and JA. Critical review of the manuscript: VP, ME, GV, EV, JB, ELS, BP, FC, DP and JA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

EV reports personal fees from Abbott, personal fees from Allergan, personal fees from Angelini, grants from Novartis, grants from Ferrer, grants and personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from Sage, personal fees from Sanofi, outside the sub-mitted work. VPS has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from AB-Biotics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, CIBERSAM, FIS- ISCIII, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier and Pfizer. DP has received grants and also served as consultant or advisor for Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck and Servier. FC has served as a speaker or in the advisory board of the following companies: Abott, Sanofi and Sandoz. He has received unrestricted research support from Telefónica Alpha. All other authors reported no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Bradley Londres for professional English language editing.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/FEDER (grants ISCIII/FEDER PI19/00236 and ISCIII/FEDER PI17/01205). ME has a Juan de la Cierva research contract awarded by the ISCIII (FJCI-2017–31738). VP, ME, and FC wish to thank the “Secretaria d′Universitats i Recerca del Departament d′Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 134 to “Mental Health Research Group”), Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia), for unrestricted research funding. EV thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PI15/00283) integrated into the National R&D&I Plan and co-funded by ISCIII- General Sub directorate for Evaluation and the European Regional Development Fund l (FEDER); CIBERSAM; and the Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca del DIUE de la Generalitat de Catalunya to the Bipolar Disorders Group (2017 SGR 1365) and the project SLT006/17/00357, from PERIS 2016–2020 (Department of Health). DP thanks the support of Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation / ISCIII/FEDER (PI17/01205); the Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca del Departament d'Economia i Coneixement of the Generalitat de Catalunya (2017 SGR 1412); and the CERCA program; the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.11.006.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Appleby L. What has been the effect of covid-19 on suicide rates? BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G.A., Galea S., Bucciarelli A., Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(5):671. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.M.S., Chiu F.K.H., Lam C.W.L., Leung P.Y.V., Conwell Y. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2006;21:113–118. doi: 10.1002/gps.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S.Sen, Gunnell D., Sterne J.A.C., Lu T.H., Cheng A.T.A. Was the economic crisis 1997-1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time-trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;68:1322–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S.Sen, Stuckler D., Yip P., Gunnell D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtet P., Olié E. Suicide in the COVID-19 pandemic: what we learnt and great expectations. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;50:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino A., Demartini B., Cavallotti S., Gambini O. Mental health services in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:385–387. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak L., Sar-el R., Mordel C., Schreiber S., Tene O. The effects of the 1st national COVID 19 lockdown on emergency psychiatric visit trends in a tertiary general hospital in Israel. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Prieto B., Martin-Fumadó C., Robinat A.P., Alonso J., Gómez-Durán E., Jordà X., Palao D. Acceso directo a fuentes forenses y exhaustividad de los registros oficiales de mortalidad por suicidio. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A., Mergl R., Kohls E., Székely A., Gusmao R., Arensman E., Koburger N., Hegerl U., Rummel-kluge C. A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D., Appleby L., Arensman E., Hawton K., John A., Kapur N., Khan M., O R.C., Pirkis J., Caine E.D., Chan Fong, L Chang, S.-S Chen, Y.-Y Christensen, H Dandona, R Eddleston, M Erlangsen, A Harkavy-Friedman, J Kirtley, O.J Knipe, D Konradsen, F Liu, S McManus, S Mehlum, L Miller, M, Moran, P, Morrissey, J, Moutier, C, Niederkrotenthaler, T, Nordentoft, M, Page, A, Phillips, M.R, Platt, S, Pompili, M, Qin, P, Rezaeian, M, Silverman, M, Sinyor, M, Stack, S, Townsend, E, Turecki, G, Vijayakumar, L, Yip, P.S, Prevention Research Collaboration, S, 2020;7:468–471. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Jiang X., Mcintyre R.S., Tran B., Sun J., Zhang Z., Ho R., Ho C., Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry-Singapore (Chongqing) Demonstration Initiative on Strategic Connectivity T. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020;87:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegerl U., Wittenburg L., Arensman E., Van Audenhove C., Coyne J.C., McDaid D., van der Feltz-Cornelis C.M., Gusmao R., Kopp M., Maxwell M., Meise U., Roskar S., Sarchiapone M., Schmidtke A., Värnik A., Bramesfeld A. Optimizing suicide prevention programs and their implementation in Europe (OSPI Europe): an evidence-based multi-level approach. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:428. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Calle D., Martínez-Alés Gonzalo, Mediavilla R., Aguirre P., Rodríguez-Vega B., Fe Bravo-Ortiz M. Trends in psychiatric emergency department visits due to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts during the COVID-19 pandemic in Madrid, Spain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020:81. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20l13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland K.M., Jones C., Vivolo-Kantor A.M., Idaikkadar N., Zwald M., Hoots B., Yard E., D’Inverno A., Swedo E., Chen M.S., Petrosky E., Board A., Martinez P., Stone D.M., Law R., Coletta M.A., Adjemian J., Thomas C., Puddy R.W., Peacock G., Dowling N.F., Houry D. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:372–379. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M., Kawashima Y., Yonemoto N., Yamada M. Active contact and follow-up interventions to prevent repeat suicide attempts during high-risk periods among patients admitted to emergency departments for suicidal behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2017-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavoor A.R., Chakravarthy K., John T. Remote consultations in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: preliminary experience in a regional Australian public acute mental health care setting. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Fay M., Feuer E., Mindthune D.N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 2000;19:335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaune E., Samuel M., Oh H., Poulet E., Brunelin J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic rapid review. Prev. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leske S., Kõlves K., Crompton D., Arensman E., de Leo, D. Real-time suicide mortality data from police reports in Queensland, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:58–63. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M.M., Korslund K.E., Harned M.S., Gallop R.J., Lungu A., Neacsiu A.D., Mcdavid J., Comtois K.A., Murray-gregory A.M. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA. 2015;98195:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llach C.D., Vieta E. Mind long COVID: psychiatric sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;49:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R.S., Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier P., Vilagut G., Ferrer M., Alayo I., Bruffaerts R., Cristóbal-Narváez P., del Cura-González I., Domènech-Abella J., Felez-Nobrega M., Olaya B., Pijoan J., Vieta E., Pérez-Solà V., Kessler R., Haro J.M., Alonso J. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the Spanish adult general population during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021;30:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier Philippe, Vilagut G., Ferrer M., Serra C., de Dios Molina J., López-Fresneña N., Puig T., Pelayo-Terán J.M., Pijoan J.I., Emparanza J.I., Espuga M., Plana N., González-Pinto A., Ortí-Lucas R.M., de Salázar A.M., Rius C., Aragonès E., Cura-González del, I Aragón-Peña, A Campos, M Parellada, M Pérez-Zapata, A Forjaz, M.J Sanz, F Haro, J.M Vieta, E Pérez-Solà, V Kessler, R.C Bruffaerts, R Alonso, J Alayo, I Alonso, J Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depress. Anxiety. 2021;38:528–544. doi: 10.1002/da.23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olié E., Nogue E., Picot M., Courtet P. Hospitalizations for suicide attempt during the first COVID-19 lockdown in France. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2021;143:535. doi: 10.1111/acps.13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oronsky B., Larson Christopher, Hammond T.C., Oronsky Arnold, Kesari Santosh, Lybeck M., Reid T.R. A review of Persistent Post-COVID Syndrome (PPCS) Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021;1(3) doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez V., Elices M., Prat B., Vieta E., Blanch J., Alonso J., Pifarré J., Mortier P., Cebrià A.I., Campillo M.T., Vila-Abad M., Colom F., Dolz M., Molina C., Palao D.J. The Catalonia Suicide Risk Code: a secondary prevention program for individuals at risk of suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;268:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignon B., Gourevitch R., Tebeka S., Dubertret C., Cardot H., Dauriac-Le Masson V., Trebalag A.-.K., Barruel D., Yon L., Hemery F., Loric M., Rabu C., Pelissolo A., Leboyer M., Schürhoff F., Pham-Scottez A., Pignon Hôpital Albert Chenevier B., hospitaliers Henri-Mondor G. Dramatic reduction of psychiatric emergency consultations during lockdown linked to COVID-19 in Paris and suburbs. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1111/pcn.13104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J., John A., Shin S., Delpozo-Banos M., Arya V., Analuisa-Aguilar P., Appleby L., Arensman E., Bantjes J., Baran A., Bertolote J.M., Borges G., Brečić P., Caine E., Castelpietra G., Chang S.-.S., Colchester D., Crompton D., Curkovic M., Deisenhammer E.A., Du C., Dwyer J., Erlangsen A., Faust J.S., Fortune S., Garrett A., George D., Gerstner R., Gilissen R., Gould M., Hawton K., Kanter J., Kapur N., Khan M., Kirtley O.J., Knipe D., Kolves K., Leske S., Marahatta K., Mittendorfer-Rutz E., Neznanov N., Niederkrotenthaler T., Nielsen E., Nordentoft M., Oberlerchner H., O'connor R.C., Pearson M., Phillips M.R., Platt S., Plener P.L., Psota G., Qin P., Radeloff D., Rados C., Reif A., Reif-Leonhard C., Rozanov V., Schlang C., Schneider B., Semenova N., Sinyor M., Townsend E., Ueda M., Vijayakumar L., Webb R.T., Weerasinghe M., Zalsman G., Gunnell D., Spittal M.J. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:579–588. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M. Can we expect a rise in suicide rates after the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;52:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P., Mehlum L. National observation of death by suicide in the first 3 months under COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2021;143:92–93. doi: 10.1111/acps.13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A., McKee M., Stuckler D. Economic suicides in the Great Recession in Europe and North America. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2014;205:246–247. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J., Chesney E., Oliver D., Begum N., Saini A., Wang S., McGuire P., Fusar-Poli P., Lewis G., David A.S. Suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious disease epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021;30:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rück C., Mataix-Cols D., Malki K., Adler M., Flygare O., Runeson B., Sidorchuk A. Will the COVID-19 pandemic lead to a tsunami of suicides? A Swedish nationwide analysis of historical and 2020 data. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H., Ishikane M., Ghaznavi C., Ueda P. Assessment of suicide in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic vs previous years. JAMA Netw. open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salut D. 2014. Anàlisis De La Mortalitat a Catalunya. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., Dunbar G... The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and valiation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman M.M., Berman A.L., Sanddal N.D., O’Carroll P.W., Joiner T.E. Part 2: suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life. Threat. Behav. 2007;37:264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon J. Spain's suicide statistics: do we believe them? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021;56:721–729. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solé B., Verdolini N., Amoretti S., Montejo L., Rosa A., Hogg B., Rizo Garcia, C Mezquida, G Bernardo, M Martinez Aran, A Vieta, E Torrent, C Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Spain: comparison between community controls and patients with a psychiatric disorder. Preliminary results from the BRIS-MHC STUDY. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;281:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D., Basu S., Suhrcke M., Coutts A., Mckee M. The public health eff ect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. The Lancet. 2009;374:315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton J. Covid-19: how coronavirus will change the face of general practice forever. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tøllefsen I.M., Helweg-Larsen K., Thiblin I., Hem E., Kastrup M.C., Nyberg U., Rogde S., Zahl P.-.H., Østevold G., Ekeberg Ø. Are suicide deaths under-reported? Nationwide re-evaluations of 1800 deaths in Scandinavia. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E., Pérez V., Arango C. Psychiatry in the aftermath of COVID-19. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2020;13:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395:1180–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., Mcintyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G. Neurobiology of suicide in times of social isolation and loneliness. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;40:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.