Abstract

This cohort study examines the ability of patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell treatments to mount T-cell immunity in response to messenger RNA vaccines for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 despite substantial B-cell depletion.

Two messenger RNA (mRNA)-based vaccines, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273, are currently available for SARS-CoV-2. Both vaccines have been shown to induce protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2 for most healthy individuals.1 Recent studies have demonstrated a substantially lower rate of antibody induction by both SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines among patients with immunosuppression, including individuals with cancer.2,3,4,5 However, the immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines among patients with selective B-cell deficiency is not well known.

Studies are ongoing to assess vaccine-induced antibody and T-cell responses among patients treated with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells that lead to substantial B-cell depletion in humans.

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies targeting B-cell lineage antigens, most notably CD19 and CD22, have demonstrated remarkable success in inducing the remission of advanced B-cell–derived cancers and have been administered to more than 10 000 patients globally. A successful response to these therapies is often accompanied by substantial B-cell depletion lasting for months to years.6 We previously showed that despite persistent B-cell depletion, some patients maintain preexisting protective humoral immunity.6 However, to our knowledge, their ability to mount new antibody responses and T-cell immunity has not yet been reported. Here, we determined whether patients with hematologic cancers treated with CAR T cells targeting the CD19 and/or CD22 B-cell lineage antigens can mount antibody and T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Methods

For this cohort study, written informed consent for participation was obtained from all patients or their guardians according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We enrolled 12 patients who achieved complete remission after receiving CAR T-cell treatments (CART) that targeted either the CD19 antigen (7 patients) or the CD19 and CD22 combination (5 patients; Table). Eight healthy adults were enrolled as controls. Race and ethnicity were self-reported. All participants received 2 doses of either the BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccine. We measured the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies and spike-specific T-cell responses in blood samples obtained at 5 or fewer time points up to 28 days after the second (booster) dose.

Table. Participant Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | Patients receiving CAR T-cell treatments (n = 12) | Healthy controls (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 53 (16-74) | 38 (27-80) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 9 (75) | 3 (38) |

| Female | 3 (25) | 5 (62) |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||

| Asian | 0 | 2 |

| Black | 1 | 0 |

| White | 11 | 6 |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccine type | ||

| BNT162b2 | 6 | 7 |

| mRNA-1273 | 6 | 1 |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| B-ALL | 6 | NA |

| DLBCL | 1 | |

| NHL | 1 | |

| MCL | 1 | |

| CLL | 3 | |

| CAR T-cell target | ||

| CD19 | 7 | NA |

| CD19 + CD22 | 5 | |

| Lymphodepletion regimen | ||

| None | 1 | NA |

| Bendamustine | 3 | |

| Cy/F combination | 7 | |

| Cy/P combination | 1 | |

| Time after CAR T-cell infusion, median (range), mo | 22 (3-126) | NA |

| Current chemotherapy and/or immunotherapyc | ||

| None | 11 | NA |

| Ponatinib | 1 | |

| Ig replacement therapy | ||

| Current | 8 | NA |

| None | 4 | |

| HSCT type | ||

| None | 5 | NA |

| Autologous | 2 | |

| Allogeneic | 5 | |

| Time after HSCT, median (range), mo | 32 (23-93) | NA |

| History of SARS-CoV-2 infectiond | ||

| No | 11 | 8 |

| Yes | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Cy, cyclophosphamide; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; F, fludarabine; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; Ig, immunoglobulin; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; mRNA, messenger RNA; NA, not applicable; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, unspecified; P, pentostatin.

Unless indicated otherwise, data are reported as number of participants.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported.

Treatments were administered within 3 months before vaccination or during the vaccine study period.

Although 1 patient reported a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, laboratory confirmation was unavailable. All participants were tested for the presence of antinucleocapsid IgG and had a negative test result (data not shown).

Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism (version 7.0e, Graphpad Software) and R software (R Core Team) and the nlme package. A Mann-Whitney test was performed as a nonparametric t test and a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunns test was performed for multiple group comparisons. Mixed-effects model analyses were used to compare longitudinal T-cell responses. A P value of .05 was used as a threshold for statistical significance.

Results

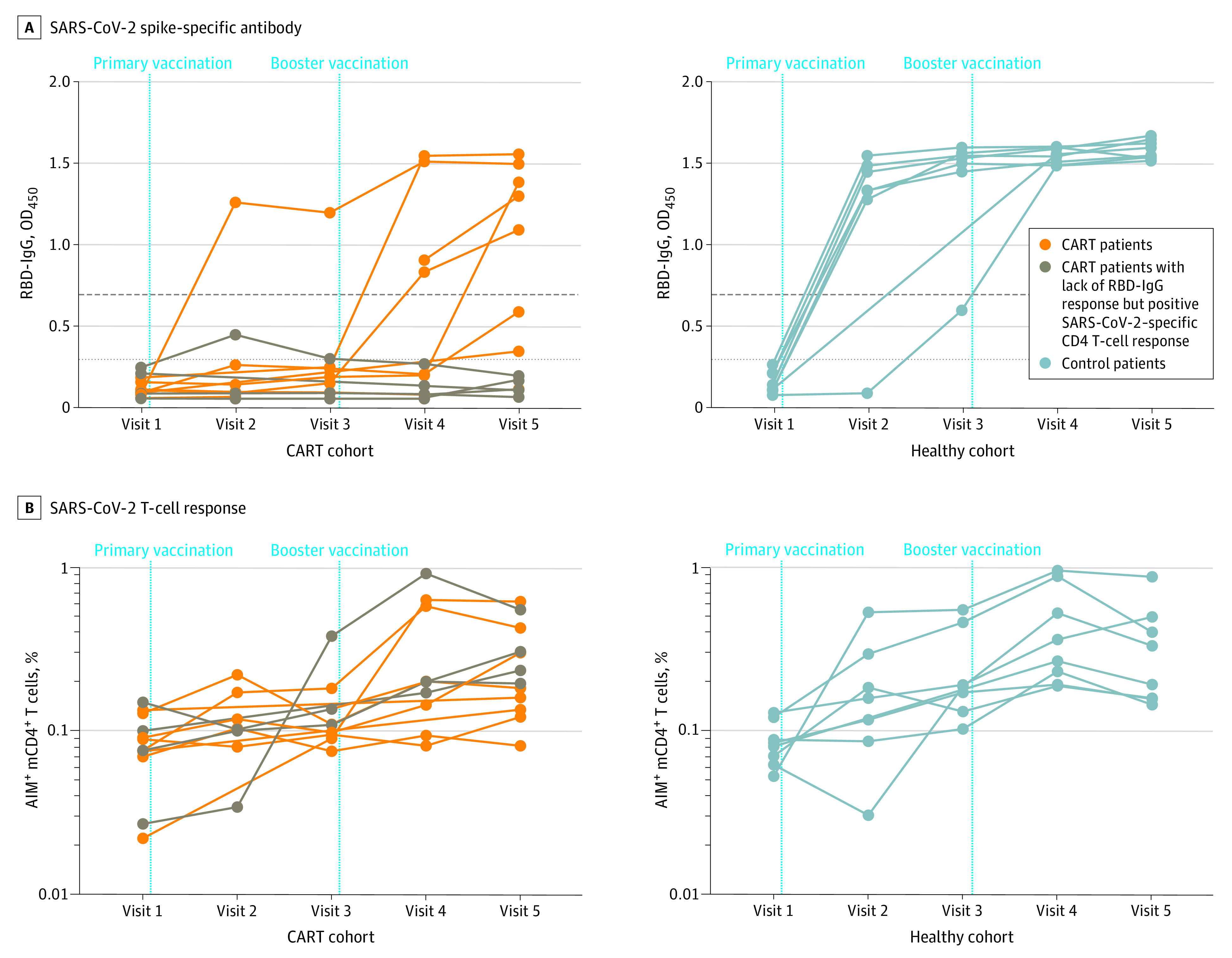

All 8 healthy controls produced RBD-immunoglobulin G (IgG) compared with 5 of 12 patients who received CAR T-cell treatments (Figure, A). One month after the booster vaccination when the antibody responses were at the highest levels in both groups (visit 5), the level of RBD-IgG was significantly lower among the CART cohort (median optical density at 450 nm [IQR], 0.47 [0.11-1.36] for CART patients and 1.57 [1.53-1.64] for healthy controls; P <.001). As expected, among the CART cohort, RBD-IgG positivity was associated with higher circulating B-cell levels (mean B-cell count/μL [SD] for RBD-IgG positive, 57.2 [20.2]; for RBD-IgG equivocal, 12.5 [17.7]; for RBD-IgG negative, 9 [10.1]; P < .05 for RBD-IgG positive vs negative). RBD-IgA was detected for 7 of 8 healthy controls compared with 2 of 12 patients in the CART cohort.

Figure. SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Specific Antibody and T-Cell Responses of Healthy Controls and Patients Treated With CAR T Cells After Spike mRNA Vaccination.

A, Spike RBD-IgG measured with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay before and after the primary and booster vaccinations for patients treated with CAR T cells and healthy controls. B, Spike-specific memory CD4+ (mCD4+) T-cell responses measured before and after the primary and booster vaccinations for patients treated with CAR T cells and healthy controls. Dashed horizontal lines indicate the thresholds of positive (top), equivocal (middle), and negative (bottom) reactivity based on clinical laboratory validation data using the same assay. For the CART cohort, brown points and lines represent 4 patients who had strong SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 T-cell responses despite robust B-cell depletion. AIM indicates activation-induced marker; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CART, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell treatment; IgG, immunoglobulin G; mRNA, messenger RNA; OD450, optical density at 450 nm; RBD, receptor binding domain.

Robust CD4 T-cell responses were detected for all 8 healthy controls, and a comparable T-cell induction was seen for 8 of 12 patients treated in the CART cohort (Figure, B). One month after the booster vaccination, we found no significant difference in the frequency of spike-specific CD4 T cells between the healthy control cohort and the CART cohort (Cohen d effect size, 0.30 [95% CI, 0.04 to 0.45 and 0.06 to 0.31, respectively]; P = .66). In addition, the kinetics of CD4 T-cell responses did not differ between the cohorts over the course of the study, in which predicted slopes of the CD4 T-cell response over time were estimated by the linear mixed-effects model for the healthy control cohort (6.3% per visit) and CART cohort (5.5% per visit) (likelihood ratio test for the difference in slopes, −1.12 [95% CI, −2.30 to 9.22; t value = 0.48, P = .63). Notably, we observed strong SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 T-cell responses for 4 patients who had robust B-cell depletion by CAR T cells; none had induced SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies after mRNA vaccination (Figure, B).

Discussion

Although this study is limited by its small sample size, we show that immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines are induced for the majority of patients who have been treated with CAR T-cell therapies targeting B-cell lineage antigens. An induction of a vaccine-specific antibody was associated with the level of circulating B cells. However, strong CD4 T-cell responses were observed even for some patients with severe humoral immune deficiency. Further refinement of vaccination strategies to promote cell-mediated immunity may enhance immune protection for individuals with B-cell deficiency. Currently, we support SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for all recipients of anti–B-cell CAR T-cell therapies, with close monitoring for immunologic responses to verify our findings in larger cohorts.

References

- 1.Goel RR, Apostolidis SA, Painter MM, et al. Distinct antibody and memory B cell responses in SARS-CoV-2 naïve and recovered individuals following mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(58):eabi6950. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abi6950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Oekelen O, Gleason CR, Agte S, et al. ; PVI/Seronet Team . Highly variable SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody responses to two doses of COVID-19 RNA vaccination in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1028-1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhakal B, Abedin SM, Fenske TS, et al. Response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients after hematopoietic cell transplantation and CAR-T cell therapy. Blood. 2021;blood.2021012769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massarweh A, Eliakim-Raz N, Stemmer A, et al. Evaluation of seropositivity following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(8):1133-1140. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cucchiari D, Egri N, Bodro M, et al. Cellular and humoral response after mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(8):2727-2739. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhoj VG, Arhontoulis D, Wertheim G, et al. Persistence of long-lived plasma cells and humoral immunity in individuals responding to CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy. Blood. 2016;128(3):360-370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-694356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]