Key Points

Question

How are localized prostate cancer treatments associated with the development of treatment-related regret?

Findings

In this prospective, population-based cohort of 2072 patients with prostate cancer, 183 (16%) of those undergoing surgery, 76 (11%) undergoing radiotherapy, and 20 (7%) of those undergoing active surveillance expressed treatment-related regret at 5 years. Compared with active surveillance, patients who underwent surgery were significantly more likely to experience regret, whereas those who underwent radiotherapy were not associated with an increased likelihood; posttreatment functional outcomes were associated with mediations in this finding.

Meaning

These findings suggest that treatment-related regret is common among patients with localized prostate cancer, and rates appear to differ among treatment approaches in a manner that is associated with functional outcomes and patient expectations.

This cohort study assesses whether an independent association between treatment modality and posttreatment regret mediates functional outcomes among men with localized prostate cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment-related regret is an integrative, patient-centered measure that accounts for morbidity, oncologic outcomes, and anxiety associated with prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Objective

To assess the association between treatment approach, functional outcomes, and patient expectations and treatment-related regret among patients with localized prostate cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based, prospective cohort study used 5 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–based registries in the Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation cohort. Participants included men with clinically localized prostate cancer from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2012. Data were analyzed from August 2, 2020, to March 1, 2021.

Exposures

Prostate cancer treatments included surgery, radiotherapy, and active surveillance.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient-reported treatment-related regret using validated metrics. Regression models were adjusted for demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics, treatment approach, and patient-reported functional outcomes.

Results

Among the 2072 men included in the analysis (median age, 64 [IQR, 59-69] years), treatment-related regret at 5 years after diagnosis was reported in 183 patients (16%) undergoing surgery, 76 (11%) undergoing radiotherapy, and 20 (7%) undergoing active surveillance. Compared with active surveillance and adjusting for baseline differences, active treatment was associated with an increased likelihood of regret for those undergoing surgery (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.40 [95% CI, 1.44-4.01]) but not radiotherapy (aOR, 1.53 [95% CI, 0.88-2.66]). When mediation by patient-reported functional outcomes was considered, treatment modality was not independently associated with regret. Sexual dysfunction, but not other patient-reported functional outcomes, was significantly associated with regret (aOR for change in sexual function from baseline, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.52-0.81]). Subjective patient-perceived treatment efficacy (aOR, 5.40 [95% CI, 2.15-13.56]) and adverse effects (aOR, 5.83 [95% CI, 3.97-8.58]), compared with patient expectations before treatment, were associated with treatment-related regret. Other patient characteristics at the time of treatment decision-making, including participatory decision-making tool scores (aOR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.69-0.92]), social support (aOR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.67-0.90]), and age (aOR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.62-0.97]), were significantly associated with regret. Results were comparable when assessing regret at 3 years rather than 5 years.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest that more than 1 in 10 patients with localized prostate cancer experience treatment-related regret. The rates of regret appear to differ between treatment approaches in a manner that is mediated by functional outcomes and patient expectations. Treatment preparedness that focuses on expectations and treatment toxicity and is delivered in the context of shared decision-making should be the subject of future research to examine whether it can reduce regret.

Introduction

For patients with localized prostate cancer, guideline-recommended treatments include active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy.1 Shared decision-making is key2,3: although absolute differences in cancer-specific and overall mortality are small,4,5 treatment-related morbidity differs according to treatment modality,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and the importance of these outcomes differs among individuals. Published studies of patient-reported outcomes6,7,8,9 have focused on disease-specific functional outcomes, including urinary symptoms, erectile dysfunction, and bowel symptoms. However, applying these data for patient counseling is complicated given that previous studies have suggested that functional impairments have little impact on bother14: nearly half of previously potent men who developed impotence after surgery reported that this was “not a problem.”15(p165)

Regret is a negative, cognitive-based emotion that uses a counterfactual framework to compare a decision with its alternatives.16 In this counterfactual structure, the experience of regret depends on expectations and whether they are met.17,18 Treatment-related regret captures the effect of treatment-related functional impairments, oncologic anxiety and outcomes, and behavioral, emotional, and interpersonal changes associated with diagnosis and treatment within the context of patient values and expectations. In prostate cancer, although previous analyses19,20 have examined treatment-related regret, these are limited by a lack of validated measures, cross-sectional design, convenience sampling, single-center cohorts with small sample sizes, and inclusion of outdated treatments.

Using the prospective population-based Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) cohort, we examined 3 hypotheses relating to treatment-related regret among patients with prostate cancer. We hypothesized an independent association between treatment modality and posttreatment regret that is mediated by functional outcomes. In addition, because counseling before treatment may affect patient expectations and perceived outcomes, we hypothesized that decision-making style at the time of initial treatment, as well as how treatment outcomes and adverse effects compared with patients’ expectations, would be associated with regret.

Methods

Cohort and Study Population

The prospective population-based CEASAR study recruited men from 5 population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries (Atlanta, Georgia; Los Angeles, California; Louisiana; New Jersey; and Utah) and the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) registry from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2012, although patients from the CaPSURE registry were omitted from this analysis owing to incomplete outcome data. Included men were 80 years or younger at diagnosis with clinically localized prostate cancer (cT1-cT2, cN0, cM0), a prostate-specific antigen level of less than 50 ng/mL, and enrollment within 6 months of diagnosis. Although the CEASAR cohort included men who received ablation (n = 60) and primary hormonal therapy (n = 72), this analysis is restricted to those who primarily received radiotherapy, surgery, or active surveillance, because these are the predominant and guideline-recommended treatments.

Patients completed mail surveys at baseline and 6 and 12 months and 3 and 5 years after diagnosis. If there was no response after 2 mailings, a trained abstractor completed the survey with the patient via telephone. Patient-reported information was supplemented with medical record abstraction, including clinical and treatment-related information, at 12 months after enrollment. These data were linked to SEER registry data.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center (coordinating center) and each participating site. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Outcome

The main outcome was treatment-related regret, operationalized using the validated prostate cancer–oriented scale of Clark et al.21 We scored regret according to the methods used by Clark et al and categorized patients as having significant regret where scores were at least 40. Regret was assessed at 5 years (primary analysis) and 3 years (sensitivity analysis) after treatment.

Exposures

Given the tripartite research goal, we considered potential exposures associated with regret. First, to address the association between treatment modality and treatment-related regret, we examined initial treatment, categorized as radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy (external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or both), or active surveillance. Patients were categorized as undergoing active surveillance if this was documented in the medical record or if no treatment was administered within 1 year of diagnosis; this second criterion is unable to distinguish between active surveillance (an observational strategy with curative intent) and watchful waiting (a palliative strategy), thus introducing potential heterogeneity.

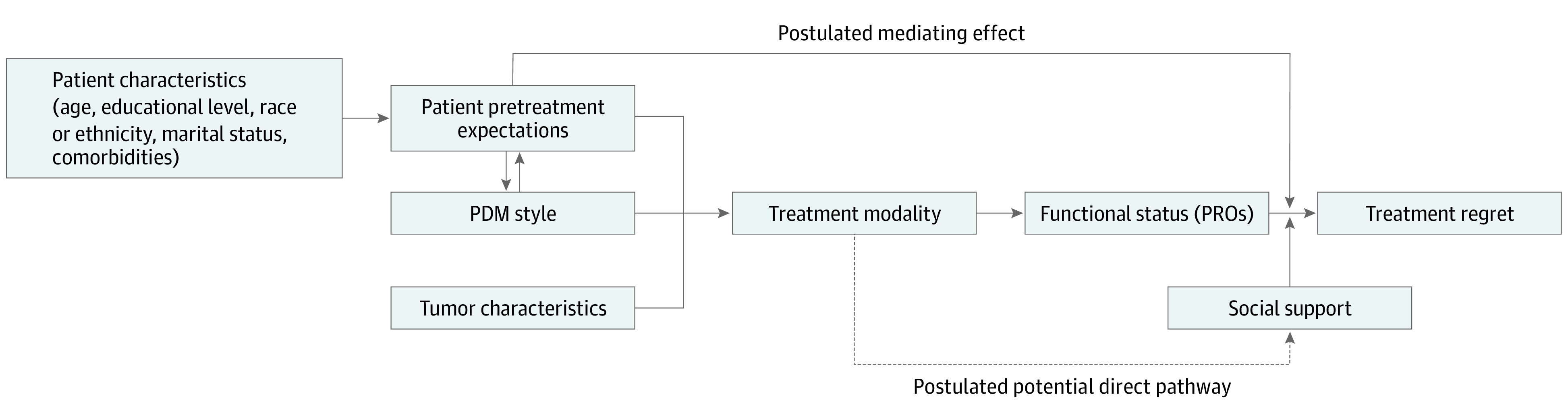

Second, we considered the mediating effect of patient-reported functional outcomes on the association between treatment modality and regret by including longitudinal changes in patient-reported disease-specific function (26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite [EPIC-26]22) and general health-related function (36-Item Short Form Health Survey [SF-36]23) from baseline to 5 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of Patient Characteristics, Pretreatment Expectations, Participatory Decision-Making (PDM) Style, Treatment Modality, Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs), and Treatment Regret.

This conceptual framework highlights that patients’ baseline characteristics influence pretreatment expectations of prostate cancer treatment. These expectations, along with PDM style (measured using the participatory decision-making tool) and tumor characteristics, drive the selection of treatment modality. Treatment modality, along with baseline functional status, is associated with posttreatment functional outcomes. The combination of treatment modality, mediated by functional status, pretreatment expectations, and social support, is hypothesized to account for treatment-related regret among patients with prostate cancer.

Third, we sought to identify characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of developing treatment-related regret. We identified these based on a literature review and consultation with both physician content experts and patients on the study team (C.J.D.W., D.F.P., R.C., K.E.H., and D.A.B.). Given the postulated association between initial decision-making as well as patient expectations, we considered these as key exposures. Medical decision-making style was assessed using the participatory decision-making tool (PDM-7).24 The difference between experienced outcomes and expectations was assessed for both treatment efficacy and toxicity using a 5-point Likert scale and operationalized in binary (a lot worse vs a lot better, a little better, the same, and a little worse). We further examined social support (as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study social support survey25), age, race and ethnicity, educational level, and marital status based on our literature search. Race and ethnicity was defined by patient report at the time of baseline questionnaire. The questionnaire included options defined according to Census designations at the time: White/Caucasian (not Latino/Hispanic); Black/African American (not Latino/Hispanic); Latino/Hispanic/Mexican American; Asian/Oriental/Pacific Islander; American Indian/Alaska Native; and other. For those who responded “other,” an option was allowed to write in a response. A small number of patients did not respond to this question on the questionnaire, and race was derived from registry data for these individuals.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from August 7, 2020, to March 1, 2021. Baseline characteristics were summarized using medians (IQRs) and frequencies (percentages) and were compared across treatments using Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 tests, respectively. Treatment regret at 5 years was modeled using 3 logistic regression models. The first model included treatment modality, D’Amico risk category, patient age, educational level, comorbidity (measured using the Total Illness Burden Index for prostate cancer26), race and ethnicity (defined according to patient response), hormone therapy, pelvic radiotherapy, study site, and PDM-7 score, captured from patient-reported surveys and medical record abstraction as appropriate. The second model further added the development of treatment-related health problems, perceptions of treatment efficacy and adverse effects compared with expectations, social support, and change in EPIC-26 domain scores (sexual function, urinary incontinence and irritative, bowel function, and hormonal) and SF-36 domain scores (physical functioning, emotional well-being, energy and fatigue) from baseline to 5 years. The third model extended the first model by including marital status, baseline social support, 5 EPIC-26 domain scores, and 3 SF-36 domain scores. Using these models, we estimated adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs reflecting the independent association of each factor with treatment regret. Because disease characteristics may influence treatment decisions, we performed an exploratory subgroup analysis stratified according to D’Amico risk category. Restricted cubic splines with 3 knots were used for age to relax the assumption of its linear association with the outcome. Missing covariates were multiply imputed using multiple imputation by chained equation as described previously.27 Statistical significance was assessed at a 2-sided 5% level. All statistical analyses were performed with R, version 4.0 (R Institute for Statistical Computing).

Results

Among 3277 patients in the CEASAR cohort, 2072 were included in the analysis. Among these men, 1136 (55%) underwent surgery, 667 (32%) underwent radiotherapy, and 269 (13%) underwent active surveillance (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The median age at diagnosis was 64 (IQR, 59-69) years. A total of 64 men (3%) were Asian, 253 (12%) were Black, 150 (7%) were Hispanic, 1573 (76%) were White, and 31 (1%) were other race or ethnicity (including American Indian/Alaska Native as well as those who responded "other" to indicate that their race or ethnicity was not included on the list of options defined by Census criteria). Among those with data available, most men had at least a college education (1449 [70%]) and were married (1614 [79%]) (Table 1). Patients undergoing radiotherapy were older, had greater comorbidity, and had slightly higher-risk disease than those undergoing surgery. Patients undergoing active surveillance, although older than those undergoing surgery, were younger than those undergoing radiotherapy and were more likely to have low-risk disease (211 [78%] vs 246 [37%] and 494 [43%]) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer Included in Analysis Examining Patient-Reported Regret at 5 Years After Diagnosis, Stratified by Initial Treatment Approach.

| Characteristic | Treatment groupa | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery (n = 1136) | Radiotherapy (n = 667) | Active surveillance (n = 269) | All (N = 2072) | ||

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 62 (57-67) | 68 (63-73) | 66 (60-71) | 64 (59-69) | <.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 38 (3) | 17 (3) | 9 (3) | 64 (3) | .03 |

| Black | 116 (10) | 103 (15) | 34 (13) | 253 (12) | |

| Hispanic | 96 (8) | 39 (6) | 15 (6) | 150 (7) | |

| White | 870 (77) | 498 (75) | 205 (76) | 1573 (76) | |

| Otherb | 15 (1) | 10 (1) | 6 (2) | 31 (1) | |

| Educational level | |||||

| Less than high school | 92 (8) | 67 (11) | 17 (7) | 176 (9) | .20 |

| High school graduate | 209 (19) | 122 (19) | 40 (16) | 371 (19) | |

| Some college | 241 (22) | 147 (23) | 52 (20) | 440 (22) | |

| College graduate | 267 (24) | 149 (23) | 65 (25) | 481 (24) | |

| Graduate/professional school | 292 (27) | 153 (24) | 83 (32) | 528 (26) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Not married | 178 (16) | 149 (23) | 53 (21) | 380 (19) | .001 |

| Married | 921 (81) | 490 (77) | 203 (79) | 1614 (79) | |

| TIBIc | |||||

| 0-2 | 397 (36) | 143 (22) | 74 (29) | 614 (31) | <.001 |

| 3-4 | 470 (43) | 266 (41) | 107 (42) | 843 (42) | |

| ≥5 | 237 (21) | 233 (36) | 76 (30) | 546 (27) | |

| D’Amico risk category | |||||

| Low | 494 (44) | 246 (37) | 211 (78) | 951 (46) | <.001 |

| Intermediate | 460 (41) | 284 (43) | 50 (19) | 794 (38) | |

| High | 180 (16) | 134 (20) | 7 (3) | 321 (16) | |

| PSA level at diagnosis, corrected, median (IQR), ng/mL | 5 (4-7) | 6 (4-8) | 5 (4-7) | 5 (4-7) | <.001 |

| PSA level at diagnosis, corrected, ng/mL | |||||

| <4 | 234 (21) | 98 (15) | 70 (26) | 402 (19) | <.001 |

| ≥4-10 | 787 (69) | 478 (72) | 166 (62) | 1431 (69) | |

| ≥10-20 | 86 (8) | 68 (10) | 29 (11) | 183 (9) | |

| ≥20-50 | 29 (3) | 23 (3) | 4 (1) | 56 (3) | |

| Clinical tumor stage | |||||

| T1 | 850 (75) | 496 (74) | 224 (85) | 1570 (76) | .002 |

| T2 | 285 (25) | 170 (25) | 40 (15) | 495 (24) | |

| Biopsy Gleason scored | |||||

| ≤6 | 570 (50) | 275 (41) | 236 (88) | 1081 (52) | <.001 |

| 3 + 4 | 336 (30) | 221 (33) | 27 (10) | 584 (28) | |

| 4 + 3 | 121 (11) | 76 (11) | 3 (1) | 200 (10) | |

| 8, 9, 10 | 105 (9) | 92 (14) | 2 (1) | 199 (10) | |

| Risk status | |||||

| Favorable | 848 (75) | 466 (70) | 258 (96) | 1572 (76) | <.001 |

| Unfavorable | 285 (25) | 198 (30) | 10 (4) | 493 (24) | |

| Any ADT in year 1 | |||||

| No | 1082 (96) | 451 (68) | 249 (93) | 1782 (87) | <.001 |

| Yes | 48 (4) | 211 (32) | 1 (0.4) | 260 (13) | |

| Received pelvic radiotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 14 (25) | 80 (13) | 0 | 94 (14) | .05 |

| No | 42 (75) | 515 (87) | 2 (100) | 559 (86) | |

| Site | |||||

| Utah | 112 (10) | 58 (9) | 42 (16) | 212 (10) | <.001 |

| Atlanta, Georgia | 143 (13) | 144 (21) | 31 (11) | 318 (15) | |

| Los Angeles, California | 367 (32) | 150 (22) | 104 (39) | 621 (30) | |

| Louisiana | 310 (27) | 186 (28) | 67 (25) | 563 (27) | |

| New Jersey | 204 (18) | 129 (19) | 25 (9) | 358 (17) | |

Abbreviations: ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; TIBI, Total Illness Burden Index.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (%) of patients. Percentages have been rounded and may not sum to 100. Owing to missing data, numbers may not sum to the totals in the column headings.

Includes American Indian/Alaska Native as well as those who responded “other” to indicate that their race or ethnicity was not included on the list of options defined by Census criteria.

Scores range from 0 to 23, with higher scores indicating greater severity and number of comorbid illnesses.

Scores range from 2 to 10 theoretically, but practically from 6 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher-grade disease.

Two hundred seventy-nine patients (13% [95% CI, 12%-15%]) reported treatment-related regret at 5 years. This was more common among patients who subjectively judged that treatment effectiveness (31 [71% (95% CI, 55%-87%)] vs 1797 [13% (95% CI, 11%-14%)]) and treatment adverse effects (190 [48% (95% CI, 41%-55%)] vs 1621 [10% (95% CI, 8%-11%)]) were much worse than expected.

Regret was more common among patients who underwent surgery (183 [16% (95% CI, 14%-18%)]) and radiotherapy (76 [11% (95% CI, 9%-14%)]) than active surveillance (20 [7% (95% CI, 4%-11%)]). Assessing the 5 questions comprising the treatment-related regret measure resulted in significant differences between treatment approaches with respect to the questions “I would be better off with a different treatment,” “I feel the treatment was the wrong one,” “I would choose another treatment if I could,” and “I wish I could change my mind about the treatment I chose” (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Patients who underwent surgery were most likely to express some degree of regret, whereas those receiving active surveillance were least likely.

Accounting for baseline demographic and tumor characteristics, initial treatment modality was significantly associated with the likelihood of treatment-related regret (P < .001) (Table 2): patients who underwent surgery were significantly more likely to experience regret than those receiving active surveillance (aOR, 2.40 [95% CI, 1.44-4.01]) or radiotherapy (aOR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.11-2.22]), whereas those who underwent radiotherapy were not more likely to experience regret compared with patients undergoing surveillance (aOR, 1.53 [95% CI, 0.88-2.66]). After stratifying by D’Amico risk category, local treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of regret compared with active surveillance among patients with low-risk disease undergoing surgery (aOR, 2.73 [95% CI, 1.45-5.14]) but not radiotherapy (aOR, 1.82 [95% CI, 0.90-3.68]) or for either approach for those with intermediate-risk disease (surgery: aOR, 2.26 [95% CI, 0.85-6.05]; radiotherapy: aOR, 1.56 [95% CI, 0.56-4.32]) but a nonsignificantly lower likelihood of regret among those with high-risk disease (aOR for surgery, 0.51 [95% CI, 0.09-2.99]; aOR for radiotherapy, 0.19 [95% CI, 0.03-1.27]), although this effect was only statistically significant for patients undergoing surgery for low-risk disease (P = .002) (Table 2). Comparisons between surgery and radiotherapy consistently indicated higher regret with surgery, though this was only significant for patients with high-risk disease (low-risk disease: aOR, 1.50 [95% CI, 0.90-2.47]; intermediate-risk disease: aOR, 1.45 [95% CI, 0.91-2.32]; high-risk disease: aOR, 2.64 [95% CI, 1.12-6.25]).

Table 2. Pairwise Association Between Treatment Modality and Patient-Reported Regret at 5 Years After Diagnosis Among Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer.

| D’Amico risk category | Treatment comparison | OR (95% CI)a | P value | OR (95% CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allc | Surgery vs active surveillance | 2.40 (1.44-4.01) | <.001 | 1.73 (0.99-3.02) | .05 |

| Radiotherapy vs active surveillance | 1.53 (0.88-2.66) | .13 | 1.42 (0.77-2.59) | .26 | |

| Surgery vs radiotherapy | 1.57 (1.11-2.22) | .01 | 1.22 (0.82-1.83) | .33 | |

| Low risk | Surgery vs active surveillance | 2.73 (1.45-5.14) | .002 | 2.08 (1.05-4.13) | .04 |

| Radiotherapy vs active surveillance | 1.82 (0.90-3.68) | .10 | 1.69 (0.79-3.62) | .18 | |

| Surgery vs radiotherapy | 1.50 (0.90-2.47) | .11 | 1.24 (0.70-2.17) | .46 | |

| Intermediate risk | Surgery vs active surveillance | 2.26 (0.85-6.05) | .10 | 1.51 (0.51-4.43) | .46 |

| Radiotherapy vs active surveillance | 1.56 (0.56-4.32) | .39 | 1.42 (0.47-4.35) | .54 | |

| Surgery vs radiotherapy | 1.45 (0.91-2.32) | .12 | 1.06 (0.62-1.80) | .83 | |

| High risk | Surgery vs active surveillance | 0.51 (0.09-2.99) | .45 | 0.27 (0.04-1.81) | .18 |

| Radiotherapy vs active surveillance | 0.19 (0.03-1.27) | .09 | 0.12 (0.02-0.92) | .04 | |

| Surgery vs radiotherapy | 2.64 (1.12-6.25) | .03 | 2.22 (0.86-5.77) | .10 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Multivariable models accounted for baseline characteristics, including age at diagnosis, participatory decision-making tool score, educational level, comorbidity (Total Illness Burden Index), race and ethnicity, receipt of androgen deprivation therapy within 1 year, receipt of pelvic radiotherapy, and registry site.

Adjusted for baseline characteristics and longitudinal functional outcomes, including patient-reported domains of the 26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey consisting of urinary incontinence, urinary irritation/obstruction, sexual dysfunction, bowel dysfunction, hormonal symptoms, physical function, mental function, and energy and fatigue.

Model further adjusted for D’Amico risk category.

Because treatment-related regret may be influenced by functional outcomes, we repeated the analysis while including the longitudinal change of patient-reported functional outcomes (per EPIC-26 and SF-36 scores), treatment-related health problems, and patients’ perceptions of treatment efficacy and adverse effects (compared with their expectations). Herein, treatment modality was no longer significantly associated with treatment-related regret, although overall trends remained consistent (Table 2). Pairwise testing stratified by disease risk showed an attenuated treatment effect compared with the first model, although compared with active surveillance, active treatment remained associated with a higher likelihood of regret among patients with low-risk disease undergoing surgery (aOR, 2.08 [95% CI, 1.05-4.13]) but not radiotherapy (aOR, 1.69 [95% CI, 0.79-3.62]) or for either approach for those with intermediate-risk disease (surgery: aOR, 1.51 [95% CI, 0.51-4.43]; radiotherapy: 1.42 [95% CI, 0.47-4.35]) and a lower likelihood among patients with high-risk disease that was significant for those undergoing radiotherapy (aOR, 0.12 [95% CI, 0.02-0.92]) but not those undergoing surgery (aOR, 0.27 [95% CI, 0.04-1.81]) (Table 2).

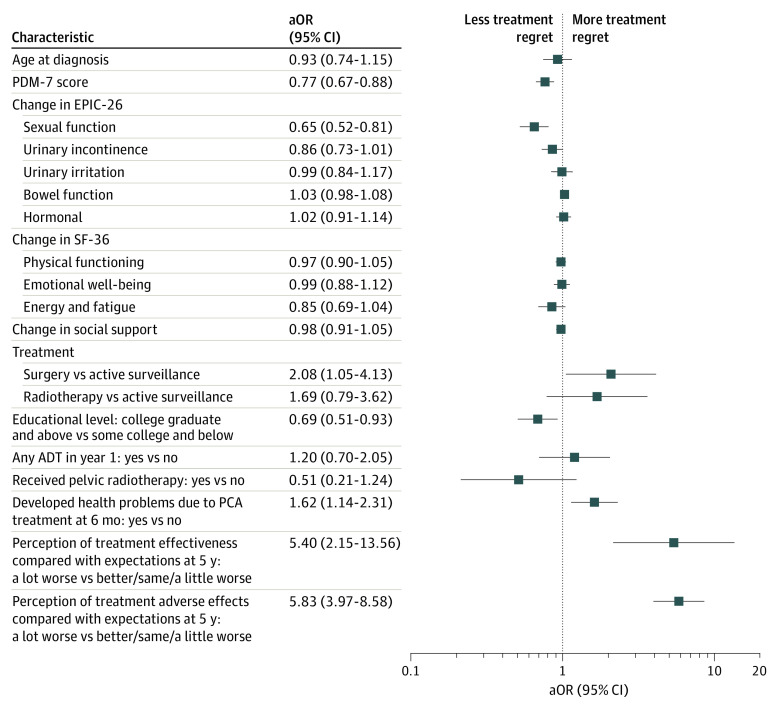

When examining exposures associated with regret, accounting for patient-reported functional outcomes, treatment modality, and baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, the effect estimates for the association of the patient’s perception of both treatment effectiveness (aOR, 5.40 [95% CI, 2.51-13.56]) and treatment adverse effects (aOR, 5.83 [95% CI, 3.97-8.58]) compared with expectations were larger than for any other variable examined (Figure 2). Although change in sexual function was significantly associated with regret (aOR, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.52-0.81]), no other functional outcome had a significant or clinically meaningful association. Scores on the PDM-7 were inversely correlated with regret (aOR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.67-0.88]), indicating that those who had greater levels of participation were less likely to experience regret.

Figure 2. Adjusted Odds Ratios (aORs) for Treatment-Related Regret at 5 Years After Diagnosis.

Comparisons are between the lower and upper quartiles unless otherwise noted. The graph presents the associations between important baseline demographic and decision-making characteristics as well as treatment-related functional outcomes and perceived treatment efficacy and toxicity, as highlighted on the y-axis, and treatment-related regret. ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; EPIC-26, 26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite; PCA, prostate cancer; PDM-7, participatory decision-making tool; and SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

Examining only characteristics available at baseline, PDM-7 scores (aOR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.69-0.92]), social support (aOR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.67-0.90], where higher scores are indicative of more support), and age (aOR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.62-0.97) were independently inversely correlated with the likelihood of regret in multivariable models. However, race and educational attainment were not significantly associated with the development of regret (Table 3). While further accounting for treatment modality, posttreatment functional outcomes, D’Amico risk category, use of hormone therapy, use of pelvic radiotherapy, and study site, many of these characteristics were no longer significantly associated with developing treatment-related regret. Notably, scores on the PDM-7 remained inversely correlated with the likelihood of regret (aOR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.67-0.88]). However, social support and age at diagnosis were no longer significantly associated with developing regret, whereas higher education appeared to be protective (aOR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.51-0.93]).

Table 3. Baseline Characteristics Associated With Patient-Reported Regret at 5 Years After Diagnosis and Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline demographic characteristics | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.78 (0.62-0.97) | .03 |

| PDM-7 score | 0.80 (0.69-0.92) | .001 |

| Social support | 0.78 (0.67-0.90) | <.001 |

| Educational level | ||

| Some college or less | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| College graduate and above | 1.33 (0.98-1.79) | .06 |

| Married (vs not married) | 0.91 (0.63-1.31) | .60 |

| Black race (vs non-Black) | 0.87 (0.56-1.36) | .54 |

| Comorbidity, TIBI score | ||

| 0-2 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 3-4 | 1.33 (0.92-1.91) | .13 |

| ≥5 | 1.23 (0.80-1.90) | .34 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||

| D’Amico risk category | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Intermediate | 1.34 (0.97-1.85) | .08 |

| High | 1.5 (1.01-2.47) | .05 |

| Baseline patient-reported functional status | ||

| EPIC-26 | ||

| Sexual function | 1.12 (0.84-1.50) | .43 |

| Urinary incontinence | 0.99 (0.88-1.12) | .92 |

| Urinary irritative | 0.83 (0.66-1.05) | .12 |

| Bowel function | 0.96 (0.89-1.04) | .29 |

| Hormonal | 0.93 (0.76-1.15) | .51 |

| SF-36 | ||

| Physical functioning | 1.09 (0.96-1.20) | .19 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.80 (0.64-1.01) | .06 |

| Energy and fatigue | 0.90 (0.69-1.19) | .47 |

Abbreviations: EPIC-26, 26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite; PDM-7, participatory decision-making tool; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; TIBI, Total Illness Burden Index.

Sensitivity Analysis

As a sensitivity analysis, we examined treatment-related regret as measured at 3 years rather than 5 years. Although there were some baseline differences in these 2 cohorts (eTable 2 in the Supplement), scores were relatively consistent over time (eFigure 2 in the Supplement), and a similar proportion of patients expressed regret both overall (285 [13%]) and when stratified by treatment approach (surgery, 192 [16%]; radiotherapy, 71 [9%]; and active surveillance, 22 [8%]). Conclusions based on regret at 3 years were similar to those identified at 5 years (overall, 13%; surgery, 16%; radiotherapy, 11%; and active surveillance, 7%) (eTables 3-5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Treatment-associated regret has been associated with poorer mental health and health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer.28,29 In this population-based, prospective cohort study of men with localized prostate cancer who received contemporary treatments, we found higher rates of regret among those who were actively treated (with surgery or radiotherapy) compared with those who received active surveillance after adjusting for baseline differences between the groups. This, however, was modified by D’Amico risk category: among patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease, active treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of regret compared with active surveillance, whereas this effect was reversed among those with high-risk disease, though this association was not always statistically significant on pairwise testing. Comparisons between surgery and radiotherapy consistently showed higher regret with surgery, although they differed significantly only among those with high-risk disease.

Our data further suggest that a disconnect between patient expectations and treatment outcomes, in relation to both treatment efficacy and toxicity, contributes more substantially to treatment-related regret than patient-reported functional outcomes themselves (including erectile dysfunction, urinary continence and other urinary symptoms, or bowel dysfunction), treatment modality, or clinicopathologic characteristics. Thus, treatment-related regret may be more modifiable than other contributors, such as functional outcomes, to the survivorship experience of patients with prostate cancer, given its link to pretreatment expectations. More thorough, evidence-based counseling before treatment may reduce regret and ameliorate the associated mental health outcomes.28,29 Treatment preparedness that focuses on expectations and treatment toxicity and is delivered in the context of shared decision-making requires further study to examine whether it can reduce regret.

Holmes et al30 showed that discussion of all treatment options was associated with a lower likelihood of treatment-related regret (12.1% vs 18.1%; aOR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.37-0.95]). We further found that higher scores on the PDM-7 and higher levels of social support at baseline were independently and inversely associated with the likelihood of regret, further supporting the importance of the initial counseling and decision-making process on the future development of regret. The use of decision aids may decrease the likelihood of treatment regret,20 although these are not routinely used. Prior work has also suggested that counseling regarding treatment choices and approaches may mitigate fear of recurrence,31 which may itself contribute to treatment regret.19

Previous studies have shown an association between functional status, particularly sexual, erectile,19,20,32,33,34,35 and bowel function,19,36 and treatment-related regret. We therefore considered that patient-reported function outcomes may mediate the association between treatment modality and treatment-related regret, given the known association between treatment modality and these outcomes.8,9 Declines in sexual function were significantly associated with regret. When we accounted for the effect of patient-reported functional outcomes, treatment modality was not significantly associated with regret, suggesting that patient-reported functional outcomes mediate the association between treatment modality and regret.37

Overall, rates of regret in this cohort at 3 and 5 years, respectively (13% and 13%, respectively, overall; 16% and 16%, respectively, among those undergoing surgery; 9% and 11%, respectively, among those undergoing radiotherapy; and 8% and 7%, respectively, among those undergoing surveillance) are very comparable to prior publications, whether among patients treated nearly 30 years ago or more contemporary analyses.19,32,33,34,35 This suggests that either there have not been objective improvements in outcomes of prostate cancer treatments during the past 25 years or that changes in patient expectations have mirrored objective improvements in the delivery of care. This is supported by our observation that patients’ perceptions of treatment effectiveness and toxicity (relative to expectations) are associated with treatment-related regret.

Although others have demonstrated an increased risk of treatment-related regret among Black men,29,34 we failed to demonstrate this association, acknowledging a relatively small sample of Black men (n = 253). Morris et al38 demonstrated that the effect of race on regret may be moderated by patient age, with no effect among younger men and lower rates in older (≥65 years) Black men compared with White men (multivariable aOR, 0.2 [95% CI, 0.1-0.7]). Consistent with previous studies,19,34 we found that regret was less common among older men. Interestingly, although other studies have shown that a longer duration of follow-up is associated with an increased likelihood of treatment decision regret in cross-sectional analyses,20,32 we found no meaningful difference in regret between 3 and 5 years in this longitudinal assessment, paralleling a prior longitudinal analysis among patients diagnosed and treated in the early 1990s.19

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The CEASAR study was not primarily designed to assess oncologic outcomes over this period. However, other studies have demonstrated that a fear of cancer recurrence or “prostate-specific antigen anxiety” may also contribute to treatment regret.19 In post hoc analyses in this cohort, transition from surveillance to active treatment was associated with increased rates of regret compared with continuing surveillance (14.7% vs 3%; P = .001), although those who reported that their physician told them that their cancer had recurred or progressed were not significantly more likely to report regret (13.5% vs 7%; P = .17). Other limitations relate to the study design, including nonrandomized treatment allocation and resultant confounding by indication. In addition, many patients with low-risk disease in the CEASAR study received an active intervention that, although common at the time, does not reflect current practice patterns favoring surveillance. Last, there may be response bias, although response rates were robust at the 5-year follow-up (71%), without differences between treatment groups. These limitations notwithstanding, this analysis is bolstered by the use of validated measures of treatment-related regret, patient-reported functional outcomes, and decision-making style as well as the large, population-based cohort of patients receiving contemporary treatment that, in contrast with prior analyses, provides generalizable results that are informative for patients treated today.

Conclusions

In our view, treatment-related regret provides an integrative, patient-centered outcome measure that accounts for both the treatment-related morbidity and oncologic outcomes and anxiety that are associated with prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. Further, these outcomes are contextualized through a patient’s own lens, weighing their relative importance and using a comparative, counterfactual framework.

The findings of this cohort study suggest that more than 1 in every 10 patients with localized prostate cancer experience treatment-related regret. A disconnect between patient expectations and outcomes, both as it relates to treatment efficacy and adverse effects, appears to drive treatment-related regret to a greater extent than factors including disease characteristics, treatment modality, and patient-reported functional outcomes such as urinary incontinence and other urinary symptoms, erectile dysfunction, or bowel dysfunction. Thus, improved counseling at the time of diagnosis and before treatment, including identification of patient values and priorities, may decrease regret among these patients.

eFigure 1. Diagram of the Assembly of the Comparative Effectiveness Analyses of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) Study Cohort and Final Analytic Cohort

eFigure 2. Bland-Altman Plot Comparing Regret Scores at 3 and 5 Years After Diagnosis Among Patients Who Completed Surveys at Both Time Points

eTable 1. Responses to Individual Components of the Treatment-Related Regret Measure, Stratified by Treatment Modality

eTable 2. Comparison of Patients Included in Analysis of Patient-Reported Regret at 5 and 3 Years After Treatment

eTable 3. Pairwise Association Between Treatment Modality and Patient-Reported Regret at 3 Years After Diagnosis Among Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics Associated With Patient-Reported Regret at 3 Years After Diagnosis and Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer

eTable 5. Baseline and Treatment Characteristics Associated With Patient-Reported Regret at 3 Years After Diagnosis and Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer

References

- 1.Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(5):479-505. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Say RE, Thomson R. The importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions—challenges for doctors. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):542-545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100-103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. ; ProtecT Study Group . 10-Year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallis CJ, Saskin R, Choo R, et al. Surgery versus radiotherapy for clinically-localized prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016;70(1):21-30. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallis CJD, Glaser A, Hu JC, et al. Survival and complications following surgery and radiation for localized prostate cancer: an international collaborative review. Eur Urol. 2018;73(1):11-20. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(5):436-445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Resnick MJ, et al. Association between radiation therapy, surgery, or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA. 2017;317(11):1126-1140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman KE, Penson DF, Zhao Z, et al. Patient-reported outcomes through 5 years for active surveillance, surgery, brachytherapy, or external beam radiation with or without androgen deprivation therapy for localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2020;323(2):149-163. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallis CJ, Herschorn S, Saskin R, et al. Complications after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: results of a population-based, propensity score-matched analysis. Urology. 2015;85(3):621-627. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallis CJ, Cheung P, Herschorn S, et al. Complications following surgery with or without radiotherapy or radiotherapy alone for prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(6):977-982. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallis CJ, Mahar A, Cheung P, et al. New rates of interventions to manage complications of modern prostate cancer treatment in older men. Eur Urol . 2016;69(5):933-941. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallis CJD, Mahar AL, Cheung P, et al. Hospitalizations to manage complications of modern prostate cancer treatment in older men. Urology. 2016;96:142-147. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penson DF. The effect of erectile dysfunction on quality of life following treatment for localized prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2001;3(3):113-119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates TS, Wright MP, Gillatt DA. Prevalence and impact of incontinence and impotence following total prostatectomy assessed anonymously by the ICS-male questionnaire. Eur Urol. 1998;33(2):165-169. doi: 10.1159/000019549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourgeois-Gironde S. Regret and the rationality of choices. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1538):249-257. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang WH, Zeelenberg M. Investor regret: the role of expectation in comparing what is to what might have been. Judgment Decis Mak. 2012;7(4):441-451. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeelenberg M, van Dijk WW, Manstead ASR, van der Pligt J. On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: the psychology of regret and disappointment. Cognition Emotion . 2000;14(4):521-541. doi: 10.1080/026999300402781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman RM, Lo M, Clark JA, et al. Treatment decision regret among long-term survivors of localized prostate cancer: results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(20):2306-2314. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.6317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie DR, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V. Why do patients regret their prostate cancer treatment? a systematic review of regret after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1002-1011. doi: 10.1002/pon.3776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark JA, Bokhour BG, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Measuring patients’ perceptions of the outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Med Care. 2003;41(8):923-936. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010;76(5):1245-1250. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), II: psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247-263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Ware JE Jr. Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision-making styles. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(5):497-504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705-714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Litwin MS, Greenfield S, Elkin EP, Lubeck DP, Broering JM, Kaplan SH. Assessment of prognosis with the Total Illness Burden Index for prostate cancer: aiding clinicians in treatment choice. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1777-1783. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu JC, Kwan L, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. Regret in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169(6):2279-2283. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000065662.52170.6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurwitz LM, Cullen J, Kim DJ, et al. Longitudinal regret after treatment for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(21):4252-4258. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes JA, Bensen JT, Mohler JL, Song L, Mishel MH, Chen RC. Quality of care received and patient-reported regret in prostate cancer: analysis of a population-based prospective cohort. Cancer. 2017;123(1):138-143. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maguire R, Hanly P, Drummond FJ, Gavin A, Sharp L. Regret and fear in prostate cancer: the relationship between treatment appraisals and fear of recurrence in prostate cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1825-1831. doi: 10.1002/pon.4384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsay J, Uribe S, Moschonas D, et al. Patient satisfaction and regret after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a decision regret analysis. Urology. 2021;149:122-128. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Stam MA, Aaronson NK, Bosch JLHR, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of localised prostate cancer and their association with regret about treatment choices. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3(1):21-31. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collingwood SA, McBride RB, Leapman M, et al. Decisional regret after robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy is higher in African American men. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(4):419-425. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diefenbach MA, Mohamed NE. Regret of treatment decision and its association with disease-specific quality of life following prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Invest. 2007;25(6):449-457. doi: 10.1080/07357900701359460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen PL, Chen MH, Hoffman KE, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidity and treatment regret in men with recurrent prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;110(2):201-205. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173-1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris BB, Farnan L, Song L, et al. Treatment decisional regret among men with prostate cancer: racial differences and influential factors in the North Carolina Health Access and Prostate Cancer Treatment Project (HCaP-NC). Cancer. 2015;121(12):2029-2035. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Diagram of the Assembly of the Comparative Effectiveness Analyses of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) Study Cohort and Final Analytic Cohort

eFigure 2. Bland-Altman Plot Comparing Regret Scores at 3 and 5 Years After Diagnosis Among Patients Who Completed Surveys at Both Time Points

eTable 1. Responses to Individual Components of the Treatment-Related Regret Measure, Stratified by Treatment Modality

eTable 2. Comparison of Patients Included in Analysis of Patient-Reported Regret at 5 and 3 Years After Treatment

eTable 3. Pairwise Association Between Treatment Modality and Patient-Reported Regret at 3 Years After Diagnosis Among Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics Associated With Patient-Reported Regret at 3 Years After Diagnosis and Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer

eTable 5. Baseline and Treatment Characteristics Associated With Patient-Reported Regret at 3 Years After Diagnosis and Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer