Abstract

We examine the impact of COVID-19 on market structure in the U.S. Specifically, we analyze the impact of both the COVID-19-induced market uncertainty period as well as the suspension of the NYSE floor on trading dynamics such as market fragmentation, algorithmic trading, and hidden liquidity in the market. During both the heightened market uncertainty and NYSE floor suspension periods, we find a significant increase in hidden liquidity yet significant decreases in both algorithmic trading and market fragmentation. However, despite withdrawing from the market during this period, remaining algorithmic traders appear to improve market quality. Our results indicate that COVID-19 had a significant impact on order routing, pre-trade transparency, and automated trading.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, NYSE floor close, Algorithmic trading, Hidden liquidity

1. Introduction

This paper explores the impact of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on market structure in the U.S. Specifically, we analyze whether the resulting uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak led to changes in overall market fragmentation. We also determine whether market participants used other trading dynamics such as hidden liquidity and algorithmic trading (AT) to handle the rising volatility and adverse selection risk in the market.5 Finally, we address whether these trading dynamics helped to reduce or exacerbate market liquidity in the U.S. market during the COVID-19 outbreak. These various market structure trading dynamics are of importance insofar they represent a contemporary market design complete with various markets, algorithmic and other low-latency trading programs, and pre-trade anonymity, all of which likely appeal to traders trying to navigate the market uncertainty and resulting NYSE floor closing that trailed the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020.

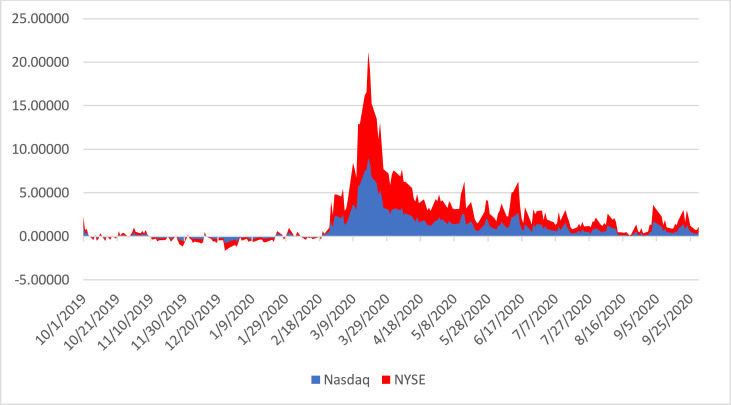

As financial markets, domestic and abroad, came to realize that the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 would likely have a damaging impact not only on public health but also on economic stability, market participants began to withdraw from the market. The resulting illiquidity and increasing price volatility were experienced in the U.S as the Dow Jones broke several records in March 2020, including the fastest bear market, the largest single-day point loss, and the overall worst quarter in U.S history. Fig. 1 depicts the overall uncertainty in the U.S stock market, where visuals of the daily price volatility for NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks are shown throughout late 2019 and most of 2020.6 Specifically, we find that standardized measures of price volatility for all stocks peak around the second week of March and remain elevated throughout the rest of the month. Moreover, we find that price volatility spikes more for NYSE-listed stocks than NASDAQ-listed stocks. This rise in volatility coincides with the market's uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak.

Fig. 1.

Price volatility by primary exchange. This figure shows the time-series standardized price volatility for our sample of securities separated by primary listing exchange. The stacked-area plot is shaded red (blue) for NYSE- (NASDAQ-) listed securities. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

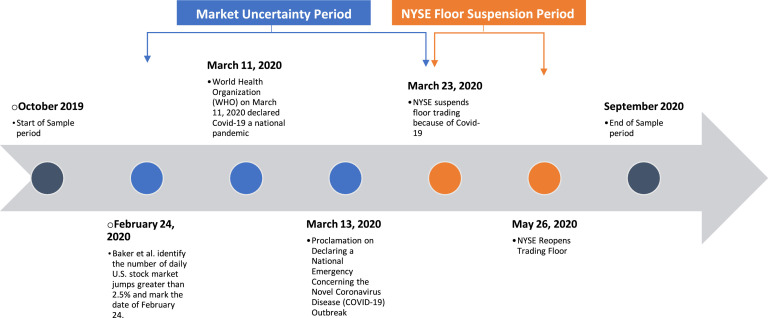

Aside from the market response to the economic uncertainty surrounding the spread of COVID-19, on March 23rd, the New York Stock Exchange, NYSE, decided to suspend all floor operations in response to fears of direct spread of the virus to NYSE employees. Fig. 2 depicts the timeline of events surrounding the market's response to the COVID-19 outbreak.7 As noted in Baker et al. (2020), large daily U.S. stock market jumps occur on February 24th – the beginning date of what we define as the market uncertainty period. Following February 24th, and through the end of March 2020, the U.S. stock market experienced an absolute daily change of 2.5% for nearly half of the trading days.8 On March 1st, 2020, President Trump declared a state of emergency and on March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that COVID-19 to be a global pandemic. On March 23rd, 2020, the NYSE announced that it would suspend floor trading. The floor suspension would be lifted on May 26th, 2020. We refer to the period between March 23rd, 2020 and May 26th, 2020 as the NYSE close period. While there is certainty overlap in the market uncertainty and NYSE close period, volatility appears to subside by early April, indicating that most of the NYSE floor closing period is not associated with the unusually high market instability. This allows us to examine which time period, market uncertainty and/or NYSE floor closing, had a larger impact on the market as well as the use of various of trading dynamics.

Fig. 2.

Event timeline COVID-19 events. February 24, 2020 - Baker et al. identify the number of daily U.S. stock market jumps greater than 2.5% and mark the date of February 24. • Baker et al. (2020) and Ibikunle and Rzayev (2020). March 1, 2020 – President Trump and the White House declared a state of emergency beginning March 1, 2020.1 ° March 11, 2020 – World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 declared COVID-19 a global pandemic.2. March 13, 2020 – Proclamation on Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak3. March 23, 2020 – NYSE suspends floor trading because of COVID-19° May 26, 2020 – NYSE Reopens Trading Floor.4

The market chaos surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 provides us a unique opportunity to explore several, separate time periods that altered aspects of market structure including market fragmentation, algorithmic trading (AT), and hidden liquidity. In exploring the various stages of the market surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak, we disentangle the effects driven by the NYSE floor closing and reopening against the preceding market uncertainty period, the latter period we expect to have a more direct effect on trading dynamics. For instance, the resulting volatility surrounding the market uncertainty period led many financial commenters to opine that the volatility was exacerbated by the presence of algorithmic trading programs.9 Further, some commented that algorithmic trading accelerated the fastest bear market in U.S. history.10 These comments are not unwarranted as research suggests that high frequency traders (HFTs), a subset of AT, tend to withdraw from the market when conditions turn unfavorable (e.g., Anand and Venkataraman, 2016). Anand and Venkataraman document that the withdrawal of HFTs from the market is undoubtedly a cause of market instability that increases both volatility and comovement in liquidity. Similar evidence provided by Malceniece et al. (2019) shows that increases in comovement among HFTs leads to increases in volatility. Thus, we analyze whether proxies for AT decline in the U.S. stock market as uncertainty rises due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

We also examine if proxies for AT exacerbate price volatility in the market uncertainty period. Theoretical and empirical evidence provide mixed evidence that AT contributes to market illiquidity, price instability, and market inefficiency. Many studies (Hendershott et al., 2011; Hasbrouck and Saar, 2013; Chaboud et al., 2014; Brogaard et al., 2014; Conrad et al., 2015; Boehmer et al., 2018b; Brogaard et al., 2019) support the notion that AT improves market quality, price discovery, and price efficiency. However, some of these studies find that these improvements in liquidity come with adverse selection costs to slow traders. Evidence provided by (Weller, 2018; Van Kervel and Menkveld, 2019) indicates that the presence of AT may erode the informational content of prices since they may deter informed investors from producing valuable research and thus mitigate their informational rents. Finally, Korajczyk and Murphy (2019) demonstrate that HFTs increase the costs of market making for institutional investors. Given the tension in the literature, we use the uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic as means to re-examine the role of AT proxies on market liquidity during periods of heightened uncertainty.

As for the role of ATs during market uncertainty, Malceniece et al. (2019) argue that since ATs have no affirmative liquidity obligations, ATs may withdraw from the market and suspend liquidity provision during unfavorable market conditions as described by Anand and Venkataraman (2016). Malceniece et al. conclude that the lack of obligated liquidity provision among ATs is consistent with the widespread belief that fast traders suspend liquidity provision during times when it is most needed such as market stress.

Malceniece et al. (2019) also document that market-making HFTs, as opposed opportunistic HFTs, are the main drivers of liquidity comovement in the market. However, such comovement may also increase market volatility to the extent fast traders scale back in unison during periods of market uncertainty.11 Yet, Menkveld (2013) shows that algorithmic trading tends to be more passive, implying that low-latency trades are supplying liquidity. Finally, both Hendershott and Riordan (2013) and Carrion (2013) demonstrate that HFTs consume (supply) liquidity when it is plentiful (scarce).12 Therefore, despite the concern that AT contributed to the widespread panic in financial markets only to profit during the COVID-19 induced market uncertainty, it is possible that AT may have actively supplied liquidity and mitigated declines in market quality.

Simultaneously, the increase in market uncertainty should coincide with an increase (decrease) in hidden liquidity (market fragmentation). Menkveld et al. (2017) show that market uncertainty leads to market consolidation as traders seek or prefer venues that offer trading immediacy over venues that offer low execution costs. Thus, in periods of heightened uncertainty, traders become more urgent and constrained by search and routing frictions and choose to consolidate more of their orders on a few select markets. Therefore, we expect markets to fragment less during the peak of the COVID-19-induced market uncertainty period. As for hidden liquidity, Bessembinder et al. show that during market turbulence, orders are less aggressively priced, resulting in wider spreads since limit orders traders experience greater risk of being “picked-off” by informed counterparties during periods of market instability and therefore price orders less aggressively. Bessembinder et al. demonstrate that when spreads widen, traders tend to make use of more hidden orders. Thus, although periods of market uncertainty inherently make the costs of consuming liquidity more expensive via a wider bid-ask spread, the economic costs of providing liquidity during market uncertainty is likely mitigated by the presence of hidden limit orders. Further, as Bessembinder demonstrates, traders that tend to hide their orders also place more aggressively priced orders, which should help narrow spreads and reduce illiquidity. Thus, traders may find hidden limit orders appealing to mitigate adverse selection risk during periods of heighted uncertainty. Overall, we expect the market uncertainty period to be associated with significant changes in market structure trading dynamics, including hidden liquidity.

Our empirical design allows us to also analyze how trading dynamics, such as hidden liquidity, were affected by the suspension or close of the NYSE floor. Goldstein and Kavajecz (2000) show that floor members via specialist's quotes help improve prices, attracting more liquidity takers. Therefore, in the absence of floor members actively providing liquidity to the market and improving prices, hidden limit order traders may take on a bigger role in supply liquidity. As for whether the closing of the NYSE floor uniquely impacts NYSE-listed stocks, relative to NASDAQ-listed stocks, we use previous literature as motivation. Older studies such as Harris (1996) and Irvine et al. (2000) suggest that floor traders are a viable source of hidden liquidity and pre-trade anonymity. Consequently, Boehmer et al. (2005) show that when the NYSE OpenBook service was introduced, which allowed more traders to self-manage their orders, hidden volume executed by floor brokers declined. These studies suggest that floor traders, at least historically, handle a considerable portion of hidden liquidity. These studies also imply that the closing of the NYSE floor, potentially mitigating the role of the floor trader, may lead to a reduction in hidden liquidity, specifically in NYSE-listed stocks.

Although floor brokers may appear to play a less significant role in providing liquidity than decades ago, NYSE's hybrid auction format, still allows floor brokers to manually submit nearly 35% all of orders (NYSE, 2019). Hu and Murphy (2020) show that hidden floor broker volume tends to peak toward the end of the closing auction period. However, Hu and Murphy also cite NYSE's own analysis that found accumulated hidden discretionary ‘D-Orders’, which have essentially replicated the manual role of floor brokers in handling contra-side orders, dropped from 30% to 0% during the closing auction period during the NYSE floor close.13 In contrast to NYSE's hybrid auction format, the NASDAQ operates under a fully electronic auction market. Therefore, we expect that during the NYSE close period as both the presence of floor brokers and hidden “D-Orders” declined during the closing auction period, hidden liquidity declined more in NYSE-listed stocks than for NASDAQ-listed stocks. However, if the NYSE close period is symbolic, the suspension of the NYSE floor is likely to have negligible impact on changes in hidden liquidity.

The closing of the NYSE floor appears to be more symbolic than consequential for U.S. markets since many electronic trading platforms and trading algorithms have replaced the role of human traders, specifically floor traders and specialists. However, despite the notion that floor traders have become increasing irrelevant, Brogaard et al. (2021) show that following the NYSE floor suspension, both price efficiency and market quality worsens. Their results indicate that the suspension of the NYSE floor suspension was more than symbolic in nature.14 However, while Brogaard et al. demonstrate that liquidity is impacted by the close of the NYSE floor, they do not empirically address changes in algorithmic trading (AT) during the NYSE floor suspension. In this paper, we employ several proxies for AT to examine whether the NYSE floor closing, and reopening had a consequential impact on AT patterns.

In addition, we also examine changes in order execution volume share across U.S. markets during NYSE floor closing period. AT and market fragmentation are integrally linked since the adoption of Regulation National Market System (NMS) facilitated the adoption of high-speed interconnected markets (Upson and Van Ness, 2017). Traders with algorithmic trading technologies have the capability to tap into multiple markets.15 Thus, as previously discussed, we expect during the market uncertainty period, both proxies for AT and market fragmentation to decline as AT reduced their market making presence. However, as a result of the NYSE floor suspension, it is possible that ATs increases their market presence to fill the role of the market maker in the absence of traditional floor traders. Simultaneously, we expect the increased presence of AT as well as the lack of market makers within the NYSE to facilitate more fragmented order executions.

Throughout the analysis, we examine the effects of the market uncertainty and NYSE close period on NYSE and NASDAQ-listed stocks, separately. To the extent that the NYSE floor suspension was more than symbolic, we expect that during the floor suspension, NYSE-listed stocks were more impacted than NASDAQ-listed stocks given that NYSE functions as a hybrid auction market with considerable human interaction whereas the NASDAQ is a fully electronic auction market.

Using two separate time periods and a matched sample of NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks, we employ a difference-in-difference analysis to examine how COVID-19 market changes influenced trading dynamics. As expected, our results indicate that during the market uncertainty period, both proxies for AT and fragmentation decrease, indicating that ATs withdrew from the market during market turbulence. Simultaneously, we discover that hidden liquidity peaks during the market uncertainty period. Following the suspension of the NYSE floor, we find proxies for AT and market fragmentation remain lower relative to the NYSE floor reopening period. Simultaneously, we find that hidden liquidity levels remain elevated during the NYSE close period relative to the NYSE floor reopening period.

Finally, our proxies for AT suggest that despite withdrawing the market during the heighted uncertainty, the remaining ATs appear to improve market quality during the market uncertainty period. This last result is consistent with the premise that during periods of market stress and extreme price volatility, certain HFTs, particularly those that provide liquidity actively aid markets by stabilizing prices and minimizing spreads. Our results are mostly consistent with the findings of Brogaard et al. (2018), who demonstrate that HFTs can act as endogenous liquidity providers (ELPs) during periods of market stress. However, our results are unique in that COVID-19 likely caused extreme price movements across many stocks, which according to the findings of Brogaard et al., should lead to HFTs switching from liquidity supply to liquidity demand, exacerbating illiquidity.

2. Data, methods, and sample

2.1. Data and sample

Our data comes from NYSE's Daily Trade and Quote (TAQ) database, CRSP, SEC's Market Information Data Analytics System (MIDAS), and EODDATA, for all common stocks from October of 2019 through September of 2020.16 For stocks to be included in our sample, we use CRSP to initially identify common stocks (share code 10 and 11) that trade at or above a price of $5.00 every day during the sample period. Using the EODDATA data to identify NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks, we conduct a matched sample analysis following the methods of Davies and Kim (2009) and Shkilko and Sokolov (2020) to compute the minimum match error for each NYSE-NASDAQ pair i – j as

| (1) |

where is firm characteristic k for firm i in the NYSE-listed sample and is firm characteristic k for firm j in the NASDAQ-listed sample. Firm characteristic k is one of two stock characteristics: price and market capitalization. We select pairs with the smallest matching errors (without replacement) by matching NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks on market capitalization and price. Our final sample includes 730 NYSE-listed and 730 NASDAQ-listed firms for a total sample size of 1460 firms. Panel A of Table 1 reports the univariate differences between the two samples by each of the matching variables and the average minimum match error. The matching procedure is successful, as price and market capitalizations do not differ economically or statistically.

Table 1.

Univariate statistics by COVID-19 events – table reports univariate statistics for NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks for Q4 of 2019 through Q3 of 2020, which are matched on market capitalization and price (Davies and Kim, 2009). Sample includes stocks that must execute at least one trade every day (253 trading days). Panel B reports statistics during the NYSE floor close (March 23, 2020- May 25, 2020) and NYSE floor reopen (May 26, 2020) and during the market uncertainty period (February 24, 2020 to March 20, 2020).

| Panel A. Pre-sample period matching variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||

| Event | NYSE | NASDAQ | Diff. | t-stat | p-value | |

| Market Capitalization ($ billion) | 11.2659 | 10.1927 | 1.0732 | −0.68 | 0.4960 | |

| Price | 63.86 | 68.93 | −5.07 | 1.17 | 0.2429 | |

| Min error mean | 3.8151 | |||||

| Panel B. Univariate Results | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables (winsorized at 1%) | Pre-Market Uncertainty Period | Market Uncertainty Period | Diff. (2–1) | NYSE Floor Close | NYSE Floor Reopen | Diff. (5–4) |

| 1 – HHI (Trade Volume) | 0.7918 | 0.7733 | −0.0186*** | 0.7803 | 0.7798 | −0.0005 |

| 1 – HHI (Order Volume) | 0.7477 | 0.7337 | −0.0140*** | 0.7358 | 0.7477 | 0.0119 *** |

| Daily Midas Venues | 12.3448 | 12.7110 | 0.3662*** | 12.6006 | 12.5048 | .09582*** |

| NYSE Mrk. Share,% | 0.1000 | 0.1167 | 0.0167** | 0.0957 | 0.0891 | −0.0067 |

| NASDAQ Mrk Share,% | 0.1859 | 0.2146 | 0.0287*** | 0.2085 | 0.2370 | 0.0285*** |

| Other Exchange Mrk Share,% | 0.0417 | 0.0472 | 0.0055*** | 0.0386 | 0.0370 | −0.0016* |

| NYSE Group Share,% | 0.1700 | 0.1935 | 0.0235** | 0.1709 | 0.1608 | −0.0101* |

| NASDAQ Group Share,% | 0.2046 | 0.2299 | 0.0253*** | 0.2213 | 0.2481 | −0.0268*** |

| CBOE Group Share,% | 0.1585 | 0.1533 | −0.0052 | 0.1667 | 0.1305 | −0.0362*** |

| Midas (Lit) Share% | 0.5748 | 0.6238 | 0.0491* | 0.5978 | 0.5782 | −0.0196 |

| Trade-to-Order | 0.0400 | 0.0451 | 0.0051*** | 0.0423 | 0.0356 | −0.0067*** |

| Odd-to-Volume | 0.3026 | 0.2782 | −0.0244*** | 0.2775 | 0.3095 | 0.0320*** |

| Trade Size | 60.6678 | 66.1752 | 5.5074*** | 63.1182 | 57.8248 | −5.2934*** |

| Cancel-to-Trade | 15.6488 | 14.9828 | −0.6660*** | 14.6627 | 16.0959 | 1.4332*** |

| Hidden-to-Volume | 0.1840 | 0.2426 | 0.0586*** | 0.2392 | 0.1897 | −0.0495*** |

| Hidden Size Volatility | 69.5656 0.0265 | 73.6384 0.0837 | 4.0728*** 0.0572*** | 71.4091 0.0607 | 64.2326 0.0387 | −7.1765*** −0.0220*** |

| Spread | 0.0007 | 0.0016 | 0.0009*** | 0.0015 | 0.0009 | −0.0006*** |

| Amihud Illiquidity | 0.0020 | 0.0062 | 0.0042*** | 0.0057 | 0.0034 | −0.0023*** |

2.2. Variables

We use multiple methods to measure the level of fragmentation and exchange venue competition experienced by each stock during the sample period. MIDAS captures the number of trades and total trade volume for each of the active 13 market venues for each stock-day. For a market venue to be included in the daily count of venues, we require that at least one share execute at that exchange. The first metric we construct is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index using trade volume and order volume from the MIDAS data set to compute the following equation:

| (2) |

where equals the market share of volume (trade or order) for each of the active 13 lit exchanges identified by the MIDAS data set. We then calculate one minus the traditional HHI to allow for an easier interpretation, this being that larger values of 1-HHI now correspond to a greater degree of market fragmentation (from here on, we refer to this measure as simply the HHI).

Our second market fragmentation metric is the number of daily MIDAS venues that a security trades on each day. For a market venue to be included in the daily count of venues, we require that at least one share execute on that exchange. As the number of daily venues that a stock records trading volume at increases, we consider this to be an increase in fragmentation. Likewise, stocks that record trading at a smaller number of daily venues, we interpret to be an example of a consolidated market.

To measure the level of competition among active stock exchanges, we compute the market share relative to all volume from both lit exchange and off-exchange venues (dark venues) across all individual stocks exchanges and across all stock exchange groups. The emphasis of this paper is to examine trading differences during the COVID-19 pandemic for NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks. Therefore, we partition individual exchange market share variables into two identifications: (1) NYSE market share, (2) NASDAQ market share. We next identify 4 exchange groups through our sample period. These include the NYSE group, NASDAQ group, CBOE, and IEX group (Spatt, 2020). The NYSE group includes the stock exchanges of NYSE, NYSE ARCA, AMEX, NSX, and the Chicago Stock Exchange (now NYSE Chicago). The NASDAQ group includes the NASDAQ, Boston Stock Exchange, and Philadelphia stock exchange (PHLX). The CBOE group includes the Bats-Y, Bats-Z, Edge-X, and Edge-A. The final group, “Other” exchange group, refers to the IEX and includes no other member exchanges except for itself.

MIDAS additionally allows us to observe trading statistics such as order volume and trades, trading volume and number of trades, odd lot trades and volume, and hidden volume and trades. To construct our algorithmic trading (AT) activity proxies, we follow the method of Weller (2018) to compute four proxies for AT activity: odd-to-volume, trade-to-order volume, cancel-to-trade ratio, and average trade size. Odd-to-volume ratio is the total volume executed in quantities smaller than 100 shares divided by the total volume traded. Trade-to-order volume ratio is the total volume traded divided by the total volume from all orders placed. Cancel-to-trade ratio is the number of full or partial order cancellations divided by the total number of trades. Trade size is the trade volume in shares divided by the number of trades.

Weller finds that odd-to-volume and cancel-to-trade ratios are positively related to AT, while a higher trade-to-order ratio and average trade size are negatively related to AT. Considering the negative relation between trade-to-order ratio, average trade size, and AT, we use the inverse of trade-to-order ratio and average trade size to allow for the same interpretation as odd-to-volume and cancel-to-trade ratios. That is as the inverse of the trade-to-order ratio and average trade size increases so does the amount of AT activity. As per the proxies used by Weller and prescribed by MIDAS, odd-to-volume, trade-to-order, and cancel-to-trade ratios are adjusted to exclude those orders reported by the NYSE and NYSE MKT.17 We make further use of the MIDAS data set to compute hidden-to-volume and average hidden trade size. Hidden-to-volume is the ratio of hidden volume to total trade volume, and average hidden trade size is the hidden volume in shares divided by the number of hidden trades.

Lastly, we use CRSP spread and (Amihud, 2002) illiquidity measure to examine the association between market liquidity and a shift in market dynamics among the various stocks exchanges and a change in trading behavior by algorithmic traders during the COVID-19 pandemic. We calculate the CRSP spread for stock i on day t as:

| (3) |

where is the ask price of stock i on day t from the CRSP daily data, is the bid price of stock i on day t from the CRSP daily data, and is the mean of and . Chung and Zhang (2014) find that in the absence of high frequency measures obtained from the NYSE Daily Trade and Quote file (DTAQ), low frequency measures such as the CRSP spread can be used in lieu of TAQ-based spreads. We follow Coen and de La Bruslerie (2019) when computing the (Amihud, 2002) illiquidity measure where and are the absolute daily return and daily trade volume for stock i on day t; and the daily measure is multiplied by .

| (4) |

3. Empirical analysis

Once again, the objective of this paper is to identify the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has on market dynamics and intermarket competition among not only exchange venues competing for order flow but among algorithmic traders. To do so, we partition the COVID-19 pandemic into two separate periods of analysis: market uncertainty period and NYSE close period. To examine the impact of COVID-19 on market dynamics and investor behavior we use a difference-in-difference fixed effects panel regression to determine the relation between the event periods outlined previously and certain market dynamic variables:

| (5) |

where , includes the standardized measure of all proxies measuring fragmentation, lit exchange competition, algorithmic trading, and market liquidity for stock i on day t. To avoid endogeneity concerns, all measures are standardized by pre-COVID mean and standard deviations. NYSE is equal to 1 if stock i is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. Event is a dummy variable identifying the market uncertainty period (MU) or the NYSE close period (NYSE Close). The market uncertainty period, MU, is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all dates from February 24, 2020, to the close of the NYSE Floor Close on March 23, 2020, and 0 for all dates prior to this period. The NYSE floor close period, NYSE Close, is a dummy variable equal to one for all dates starting on March 23, 2020, and ending before May 26, 2020, and 0 for all dates in floor reopening period (May 26, 2020 – September 30, 2020). In the subsequent analysis, we examine the effects of the market uncertainty and NYSE floor closure periods, separately.

The interactions, and give the difference-in-difference (DiD) estimates between the effect that either the market uncertainty or the NYSE floor closing period had on NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed securities. We include common control variables such as the natural log of the firm's daily market capitalization, price, and volume. The regression model includes both day and stock fixed effects and all regression standard errors are clustered by stock and date.

3.1. Univariate

Table 1 provides both the summary statistics of our matched sample as well as the univariate results across our multiple trading periods. Panel B of Table 1 reports univariate statistics for the two separate periods of analysis in this study. Column 3 of Table 1 reports the differences between the market uncertainty period and the pre-market uncertainty period, while column 6 reports the differences between the NYSE floor reopening period to the closure period. The results regarding volatility differences are consistent with Fig. 1, in that volatility spikes significantly during the market uncertainty period when compared to the pre-market uncertainty period. Furthermore, this significant increase in volatility persists into the NYSE floor closure period before returning to pre-COVID-19 levels in the reopening period.

We next use the exogenous shock that is the COVID-19 pandemic and the elevated levels in volatility to determine the effects this period has on liquidity, fragmentation, market dynamics, etc. First, the impact on market liquidity is inconsistent with the findings of Ibikunle and Rzayev (2020). We see a deterioration in liquidity measured by the percentage spread and Amihud Illiquidity. During the market uncertainty period (MU), spreads increase by 9 basis points, while Amihud illiquidity is 42 basis points or 210% higher. These reductions in market quality persist into the NYSE floor closure period, where spreads are 6 basis points wider, and Amihud Illiquidity is 23 basis points or 40.35% higher than the reopening period. Additionally, we see that the effects of COVID-19 appear to be greatly diminished during the reopening period as liquidity and volatility are near pre-COVID levels.

The effects of COVID-19 on fragmentation are consistent with the premise that during periods of heightened uncertainty, trading becomes more consolidated. In fact, stocks are significantly more consolidated during the MU period as shown by a decrease in two of the three-fragmentation metrics. HHI measured using trade and order volume decreased by 186 and 140 basis points, respectively. However, the number of daily venues that a stock executes a trade at increases during the MU period. Consistent with the trend identified in spreads and volatility, the NYSE floor closure period shows significant consolidation before returning to pre-COVID fragmentation levels in the reopening period.

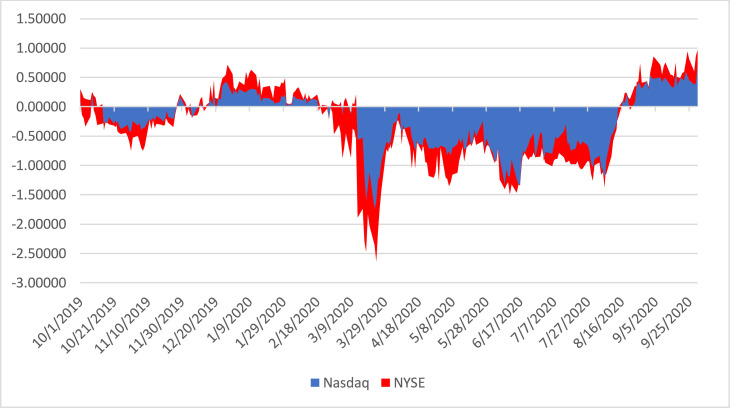

Fig. 3 provides the time-series visuals of how fragmentation changes throughout the sample period. In the stacked-area chart, the NYSE (NASDAQ) -listed stocks are shaded in red (blue). The standardized levels of market fragmentation appear to show the deepest decline around the third week of March – the height of the MU period. Further, it appears that fragmentation decreases more for NYSE-listed stocks.

Fig. 3.

Market fragmentation by primary listing exchange. This figure shows the time-series standardized market fragmentation for our sample of securities separated by primary listing exchange. The stacked-area plot is shaded red (blue) for NYSE- (NASDAQ-) listed securities. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

The effect of COVID-19 on market dynamics among the various lit and dark exchanges provides evidence similar to Ibikunle and Rzayev (2020), who find that excessive volatility surrounding COVID-19 affects order routing preferences in which orders are re-routed from off-exchanges to lit exchanges. The venue competition measures (NYSE, NASDAQ, Other Exchange market shares, NYSE group, NASDAQ group, and CBOE group) are computed using total volume from lit venues provided in MIDAS. The MU period is characterized by significantly larger market shares for the NYSE and NASDAQ exchanges and group, while CBOE group share is not significantly different. The findings in Table 1 imply that volume that is executing at the NYSE and NASDAQ exchanges is largely being pulled from off-exchange venues rather than other lit exchanges.

Given the numerous exogenous events during the MU period which include several market wide trading suspensions and numerous proclamations and announcements by the White House and WHO, this period may be regarded as a period of constant heightened immediacy. Therefore, the findings provide evidence consistent to the “pecking order” hypothesis of Menkveld et al. (2017), whereby traders who seek immediacy will route orders out of dark venues and to lit exchanges despite the higher transaction costs. Similar to the MU period, the NYSE Close period is characterized by fragmented trading across multiple lit exchanges. However, once the floor reopening period begins, we see a return to pre-COVID-19 volatility levels and a significant reduction in NYSE, NASDAQ, and CBOE group shares. This implies that there is no longer a need for immediacy because of the reduced volatility and orders are executing back in off-exchange venues.

Lastly, we analyze the impact that COVID-19 has on algorithmic trading (AT) activity during both periods of analysis. We see a significant loss in algorithmic trading activity during the MU period and the NYSE Floor closure period. The signs of all algorithmic trading proxies, following Weller (2018), imply a decrease in algorithmic trading activity during the MU period that persists into the NYSE Floor closure period before there is a reversal in the AT proxies to pre-COVID levels in the floor reopening period. Additionally, we also see that during the MU period there is substantial increase in hidden to volume and average hidden trade size by 31.85% and 5.85%, respectively.

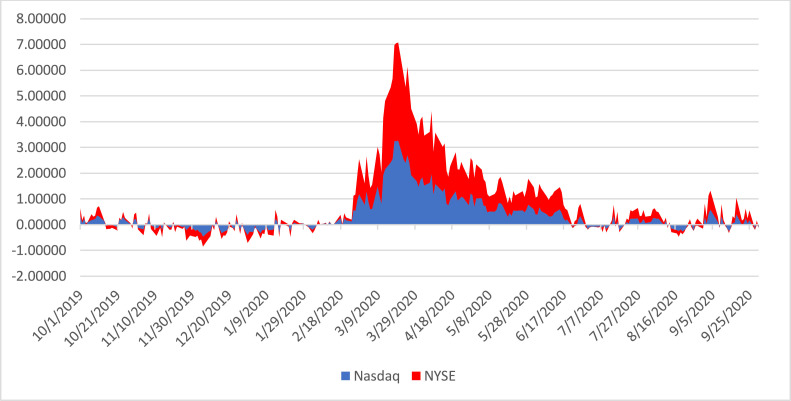

Fig. 4 shows the time-series visuals of hidden liquidity for our sample of NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks. In the stacked-area chart, the NYSE (NASDAQ) -listed stocks are shaded in red (blue). The standardized measures of hidden liquidity spike in the third week of March. Consistent with the results provided in early graphs, the results appear to be stronger in our sample of NYSE-listed stocks. The early results appear to indicate that market participants appear to use hidden liquidity during the height of the COVID-19 induced market uncertainty.

Fig. 4.

Hidden liquidity by primary listing exchange. This figure shows the time-series standardized hidden liquidity for our sample of securities separated by primary listing exchange. The stacked-area plot is shaded red (blue) for NYSE- (NASDAQ-) listed securities. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

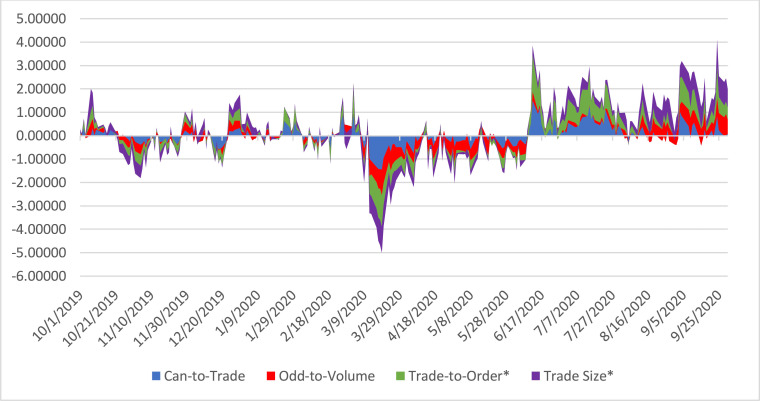

Fig. 5 shows the time-series visuals of algorithmic trading (AT) measures for our sample of NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks. In the stacked-area chart, the average daily inverted trade-to-order is shaded green, daily inverted trade size is shaded purple, daily cancel-to-trader ratio is shaded blue, and the daily odd-to-volume ratio is shaded red. All reported measures reported in Fig. 5 are standardized. The visuals in Fig. 5 confirm that AT declines considerably in late March. Moreover, it appears that AT remains low even through the entire NYSE floor closure period.

Fig. 5.

Algorithmic Trading (AT). This figure shows the time-series of standardized measures of algorithmic trading (AT) for our sample of securities. The stacked-area plot is shaded blue for the standardized cancel-to-trade ratio. The stacked-area plot is shaded red for the standardized odd-to-volume ratio. The stacked-area plot is shaded green for the standardized inverted trade-to-order ratio. The stacked-area plot is shaded purple for the standardized inverted trade size. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

The results provided in Fig. 5 contrast with those provided in a contemporary study by Chakrabarty and Pascual (2021), who document that AT activity, using quote intensity levels, increases during the market uncertainty. While quote intensity as well as our measures have proven to be viable proxies of AT, we suggest that our results may differ from those provided by Chakrabarty and Pascual due to the following reasons: first, our study examines a sample (1460 firms) which is three times the size of their sample (463 firms); second, their study is restricted to large-cap firms that are part of the S&P 500 whereas our study includes small-, medium, and large-cap stocks which is noteworthy since Boehmer et al. (2018a) note that implementing market-making strategies or disguising informed trading intentions associated with AT is likely easier in large-cap stocks than in small-cap stocks; third, as Lee and Watts (2021) point out, MIDAS incorporates both quote and cancelation information from the entire order book whereas market data reported in TAQ is limited to information on the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO); fourth, Erhard and Sloan (2020) note that MIDAS measures used to proxy for AT differ conceptually from more granular measures such as strategic runs or quote intensity (i.e., quote updates) given that these latter two measures are unscaled whereas the MIDAS measures have built-in controls for concurrent trading activity.

3.2. Market uncertainty

We next examine the market uncertainty period (MU) in depth by analyzing the DiD fixed effects model in Eq. (5) for the effects the MU period has on fragmentation, market dynamics, and algorithmic trading. Table 2 presents the results for Eq. (5), where the Event variable is MU, which is equals 1 for all dates from February 24, 2020, to the close of the NYSE Floor on March 23, 2020, and 0 for all dates prior to this period. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the market uncertainty period had on NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed securities.

Table 2.

DiD regression: fragmentation around market uncertainty dates: Table 2 reports the regression analysis to examine market dynamics around a period high market uncertainty (Baker et al., 2020) brought about by the events concerning the spread of COVID-19, using a difference-in-difference fixed effect model. The dependent variables are winsorized at the 1% level and standardized. These variables include: Trade and Order Volume Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (1-HHI), Daily Midas Venues, NYSE Market Share, NASDAQ Market Share, Cumulative market share of all other venues, NYSE Group Market Share, NASDAQ Group Market Share, and CBOE Group Market Share. MU is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all dates from February 24, 2020 to the close of the NYSE Floor on March 23, 2020, and 0 for all dates prior to this period. NYSE is equal to 1 if the stock is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the market uncertainty period had on NYSE and NASDAQ-listed securities. Control variables include the natural log of the firm's market capitalization, price, and volume. All regression standard errors are clustered by stock and include both stock and day fixed effects (unless otherwise specified). T-statistics are recorded in the parentheses and asterisks ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | HHI Trade Volume | HHI Order Volume | Daily Midas Venues | NYSE Mrk. Share | NASDAQ Mrk. Share | Other Exchange Mrk. Share | NYSE Group Mrk. Share | NASDAQ Group Mrk. Share | CBOE Group Mrk. Share |

| NYSE | 0.0206 | 0.0110 | 0.0036 | −0.0249 | −0.1411*** | −0.0209** | −0.0219 | 0.0155 | −0.0161* |

| (1.48) | (0.48) | (0.45) | (1.08) | (7.92) | (2.46) | (1.57) | (0.99) | (1.78) | |

| MU | −0.5685*** | −0.2348** | 0.5261*** | 0.3434*** | 0.7559*** | 0.1200 | 0.4520*** | 0.8069*** | −0.0823 |

| (8.50) | (1.97) | (17.17) | (8.19) | (10.65) | (1.54) | (8.55) | (10.11) | (1.01) | |

| MU *NYSE | −0.0686 | −0.3028** | 0.0917*** | 0.4211*** | −0.3689*** | 0.1303*** | 0.4520*** | −0.3119*** | 0.1515*** |

| (0.74) | (2.51) | (4.28) | (5.25) | (9.53) | (4.40) | (8.55) | (6.81) | (4.71) | |

| Log Market Cap. | −0.0468*** | 0.0746*** | −0.1308*** | 0.1103*** | 0.1194*** | 0.1416*** | 0.1521*** | 0.1991*** | 0.2196*** |

| (4.18) | (6.58) | (−12.47) | (6.42) | (4.95) | (4.27) | (6.15) | (6.92) | (7.52) | |

| Log Price | 0.0372*** | −0.0558*** | 0.1280*** | −0.0996*** | −0.0960*** | −0.1492*** | −0.1466*** | −0.2266*** | −0.2197*** |

| (3.35) | (3.66) | (8.24) | (5.31) | (3.51) | (4.28) | (5.51) | (7.13) | (7.29) | |

| Log Volume | 0.0037*** | −0.0976*** | 0.1422*** | −0.1059*** | −0.1467*** | −0.1370*** | −0.1355*** | −0.1676*** | −0.1760*** |

| (4.15) | (9.02) | (12.42) | (6.34) | (6.26) | (4.10) | (5.38) | (5.78) | (6.43) | |

| Constant | 0.4151*** | −0.1507 | 0.5993*** | −0.6624*** | −0.7136*** | −0.7513*** | −1.0186*** | −1.3348*** | 1.6510*** |

| (3.23) | (0.98) | (5.82) | (5.09) | (3.54) | (2.85) | (5.96) | (5.97) | (5.67) | |

| Observations | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 |

| R-squared | 0.0420 | 0.0396 | 0.0754 | 0.0434 | 0.0798 | 0.0134 | 0.0530 | 0.0609 | 0.0231 |

| Number of Stocks | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 |

| Day Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Day Clustered Errors | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Clustered Errors | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

There are several notable findings in Table 2. First, consistent with the univariate results, the MU period is associated with significant consolidation when measured using both trade and order volume HHI. Furthermore, NYSE-listed stocks are significantly more consolidated in order volume than NASDAQ-listed stocks during this period.18 In columns (1) and (2), the parameter estimates for MU for both trade and order volume HHI are −0.5685 and −0.2348, respectively, while the HHI order volume parameter estimate of the interaction term, MU*NYSE, is −0.3028 and implies that NYSE-listed stocks are significantly more consolidated than NASDAQ-listed stocks. Although markets appear to be more consolidated when measured by HHI, fragmentation measured by daily venues appears to increase during the MU period. In column (3), the parameter estimate 0.5261 for MU suggests an overall increase in daily venues. This may be explained by the loss of off-exchange venue volume, in which orders that were once executing off-exchange venues are now executing at lit exchanges. Even though the market becomes more consolidated overall in terms of volume, there are more trades executing at lit venues. This change in venue selection is in line with the pecking order hypothesis (Menkveld et al., 2017).

We next look to analyze the effect the MU period has on market dynamics among the various lit exchanges and determine which market venues attract orders during periods of high volatility and increased immediacy. Most notably, the NYSE and NASDAQ market share increase significantly during the MU period, but other exchange market share has no significant movement. In columns (4) and (5), the coefficients for MU, 0.3434 and 0.7559, show that NYSE and NASDAQ market shares increase during the MU period, respectively, and implies that orders are largely executing at these two venues rather than off-exchange venues. Furthermore, NYSE-listed stocks appear to execute more at the NYSE and NASDAQ-listed stocks execute more at NASDAQ. The interaction term, MU*NYSE, shows a significant increase in NYSE market share over NASDAQ stocks, but the NASDAQ market share is significantly lower for NYSE stocks compared to NASDAQ stocks as shown by the parameter estimate of −0.3689 (see column 5). The regression of the interaction term on Other Exchange market share produces a coefficient of 0.1303 (see column 6), which can be explained by the group market share regressions in columns (7) through (9) of Table 2. The regressions of the group market shares are similar to the individual market share regressions, but the interaction term coefficients further show that NYSE stocks are executing more trades at the NYSE group and CBOE group but not at the NASDAQ group.

The findings in Table 2 imply that during periods of high volatility, trade execution decisions appear to favor the NYSE and NASDAQ exchanges over all other available lit venues. There is also a significant difference between NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks as to which venues are executing orders. NASDAQ-listed stocks appear to execute more orders at the NASDAQ exchange than all other venues, whereas NYSE-listed stocks largely favor NYSE group venues but also execute orders at the CBOE group. The findings in columns 4–9 are, once again, consistent with the findings of Menkveld et al. (2017) and Ibikunle and Rzayev (2020) that during periods of high volatility and immediacy orders largely execute at lit exchanges rather than off-exchange venues.

We next determine the impact that COVID-19 has on the proxies for algorithmic trading (AT) activity by analyzing Eq. (5), where the dependent variables include the standardized odd-to-volume, inverse trade-to-order, cancel-to-trade, inverse trade size, hidden-to-volume, and average hidden trade size. We use the inverse of trade-to-order and trade size to allow for an easier interpretation of the coefficients. Using the inverse of these two measures changes this relation to a positive association and thus can be interpreted the same as odd-to-volume and cancel-to-trade. Table 3 presents the results for Eq. (5) and the coefficients for MU and the interaction term are consistent with the univariate results. The coefficients in columns (2) and (4) of Table 3, −0.2836 and −0.1760, respectively, show that the MU period is associated with a significant decrease in odd-to-volume and the inverse of trade size. The interaction coefficients further show that NYSE-listed stocks have a larger decrease in algorithmic trading activity than for NASDAQ-listed stocks. The findings in Table 3 are consistent with the findings of Malceniece et al. (2019) who argue that ATs withdraw from the market and suspend liquidity provision during unfavorable market conditions.

Table 3.

DiD regression: MIDAS measures around market uncertainty dates: Table 3 reports the regression analysis to examine market dynamics around a period high market uncertainty (Baker et al., 2020) brought about by the events concerning the spread of COVID-19, using a difference-in-difference fixed effect model. The dependent variables are winsorized at the 1% level and standardized. These variables include: inverse Trade-to-Order, Odd-to-Volume, Cancel-to-Trade, inverse Trade Size, Hidden-to-Volume, and Hidden Size. To allow for the similar interpretations we use the inverse of Trade-to-Order and Trade Size. MU is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all dates from February 24, 2020 to the close of the NYSE floor on March 23, 2020, and 0 for all date prior to this period. NYSE is equal to 1 if the stock is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the market uncertainty period had on NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed securities. Control variables include the natural log of the firm's market capitalization, price, and volume. All regression standard errors are clustered by stock and include both stock and day fixed effects (unless otherwise specified). T-statistics are recorded in the parentheses and asterisks ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Trade-to-Order* | Odd-to-Volume | Cancel-to-Trade | Trade Size* | Hidden-to-Volume | Hidden Size |

| NYSE | −0.0030 | 0.0059 | −0.0035 | 0.0041 | −0.0128 | −0.0002 |

| (0.17) | (0.37) | (0.22) | (0.27) | (1.14) | (0.02) | |

| MU | 0.1871 | −0.2836*** | 0.1322 | −0.1760*** | 1.4241*** | −0.0458 |

| (1.28) | (4.14) | (0.79) | (3.00) | (6.62) | (1.03) | |

| MU*NYSE | −0.0101 | −0.2742*** | −0.0093 | −0.2205*** | 0.2627*** | 0.1177*** |

| (0.25) | (6.62) | (0.20) | (6.96) | (3.42) | (3.69) | |

| Log Market Cap. | 0.4747*** | 0.4292*** | 0.4079*** | 0.4284*** | −0.1197*** | −0.3692*** |

| (20.56) | (19.32) | (17.26) | (20.52) | (6.40) | (20.95) | |

| Log Price | −0.4548*** | −0.3931*** | −0.3915*** | −0.3997*** | 0.1682*** | 0.3218*** |

| (17.74) | (14.29) | (14.90) | (15.43) | (6.13) | (14.46) | |

| Log Volume | −0.4696*** | −0.4192*** | −0.4111*** | −0.4080*** | 0.1631*** | 0.3428*** |

| (23.41) | (22.23) | (18.85) | (23.54) | (7.46) | (23.29) | |

| Constant | −2.5548*** | −2.4147*** | −2.1060*** | −2.5231*** | −0.1769 | 2.3826*** |

| (11.16) | (10.94) | (9.67) | (11.54) | (0.63) | (11.96) | |

| Observations | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 | 173,397 |

| R-squared | 0.1254 | 0.1639 | 0.0944 | 0.1451 | 0.2249 | 0.0824 |

| Number of Stocks | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 |

| Day Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Day Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

In columns (5) and (6) of Table 3, we find that the MU period is associated with a significant increase in hidden-to-volume but a decrease in average hidden trade size, as shown by the MU regression estimates of 1.4241 and −0.0458, respectively. The interaction coefficients in Table 3 show that NYSE-listed stocks are not significantly different from NASDAQ-listed stocks in regard to the amount of hidden trading activity, but NYSE-listed stocks do have significantly larger hidden trade sizes. The findings in columns (5) and (6) of Table 3, may partially be explained by the findings of Friederich and Payne (2015) who find that anonymity has a large and positive impact on liquidity in terms of spreads, depths, price impact, and dynamic price drift. Friederich and Payne also find that small stocks, stocks with naturally shallow order books, and stocks where trading is highly concentrated benefit the most from anonymity. Seeing as the results in Table 2 show an overall consolidation in order executions among venues, it stands to reason that this period is associated with an increase in hidden trading activity to alleviate the deterioration in liquidity as a result of the excessive volatility.

3.3. NYSE floor close

The second period of analysis in this study is to determine what effect the NYSE Floor closure has on market dynamics considering that there exists excessive volatility, albeit less than the MU period, and the loss of one major advantage that the NYSE exchange has over other market venues. Table 4 presents the results for Eq. (5), where Event is NYSE Close, which is equal to one for all dates starting on March 23, 2020, and ending before May 26, 2020, and 0 for all dates in Floor Reopening period (May 26, 2020 – September 30, 2020). The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the NYSE floor closing has on NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed securities.

Table 4.

DiD regression: fragmentation around NYSE floor closing and reopening: reports the regression analysis to examine fragmentation around the NYSE floor closing and reopening during COVID-19 using a difference-in-difference fixed effect model. The dependent variables are winsorized at the 1% level and standardized. These variables include: Trade and Order Volume Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (1-HHI), Daily Midas Venues, NYSE Market Share, NASDAQ Market Share, Cumulative market share of all other venues, NYSE Group Market Share, NASDAQ Group Market Share, CBOE Group Market Share. NYSE Close is a dummy variable equal to one for all dates starting on March 23, 2020 and ending before May 26, 2020, and 0 for all date in Floor Reopening period (May 26, 2020 – September 30, 2020). NYSE is equal to 1 if the stock is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the NYSE floor closing and reopening had on NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed securities. Control Variables include the natural log of the firm's market capitalization, price, and volume. All regression standard errors are clustered by stock and date and include both stock and day fixed effects (unless otherwise specified). T-statistics are recorded in the parentheses and asterisks ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | HHI Trade Volume | HHI Order Volume | Daily Midas Venues | NYSE Mrk. Share | NASDAQ Mrk. Share | Other Exchange Mrk. Share | NYSE Group Mrk. Share | NASDAQ Group Mrk. Share | CBOE Group Mrk. Share |

| NYSE | 0.4735*** | 0.6826*** | 0.0038 | −0.3803*** | 0.2810*** | −0.0082 | −0.7094*** | 0.7777*** | 0.4057*** |

| (8.10) | (7.55) | (0.17) | (10.47) | (12.21) | (0.72) | (19.64) | (17.79) | (13.84) | |

| NYSE Close | −0.2849*** | −0.1418 | 0.1313*** | 0.0666** | −0.3884*** | 0.6877*** | −0.0270 | −0.4172*** | 1.1019*** |

| (6.37) | (1.63) | (5.08) | (2.34) | (6.55) | (11.28) | (0.57) | (6.11) | (17.44) | |

| NYSE Close*NYSE | 0.5062*** | −0.2052** | 0.0169 | 0.1324*** | −0.2922*** | 0.0423* | 0.3114*** | −0.4914*** | −0.1734*** |

| (7.16) | (2.17) | (0.96) | (2.90) | (8.16) | (1.93) | (6.20) | (10.82) | (4.58) | |

| Log Market Cap. | −0.0346 | 0.0005 | −0.1473*** | 0.0642** | 0.2819*** | 0.1250*** | 0.0232 | 0.4728*** | 0.3060*** |

| (1.09) | (0.015) | (8.25) | (2.41) | (9.50) | (3.74) | (0.63) | (10.33) | (9.56) | |

| Log Price | 0.1788*** | 0.3777*** | 0.1073*** | −0.0467 | −0.3008*** | −0.1306*** | 0.0017 | −0.5780*** | −0.3638*** |

| (4.39) | (7.88) | (4.42) | (1.44) | (9.51) | (3.87) | (0.04) | (11.39) | (10.29) | |

| Log Volume | 0.0255 | −0.0519** | 0.1627*** | −0.1170*** | −0.2412*** | −0.1205*** | −0.0233 | −0.2962*** | −0.2662*** |

| (0.96) | (2.00) | (10.43) | (5.19) | (8.80) | (3.77) | (0.73) | (7.22) | (9.43) | |

| Constant | −0.9267** | −1.2358*** | 1.0391*** | 0.3295 | −1.4608*** | −0.8696*** | 0.1443 | −3.5031*** | −2.6846*** |

| (2.45) | (2.85) | (4.55) | (1.12) | (6.22) | (3.57) | (0.42) | (8.01) | (8.09) | |

| Observations | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 |

| R-squared | 0.0599 | 0.0943 | 0.0251 | 0.0377 | 0.1272 | 0.1130 | 0.0663 | 0.1530 | 0.2034 |

| Number of Stocks | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 |

| Day Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Day Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

First, the results in columns 1–3 of Table 4 present similar findings to the MU period, whereby there is an overall consolidation in trade volume and order volume but the number of daily venues executing a trade increases during the floor closure period. One notable difference between the MU period and the NYSE Close period is that NYSE-listed stocks during the closure period are significantly more fragmented than NASDAQ-listed securities. The interaction term coefficient 0.5062 in column (1) of Table 3 implies an increase in trade volume HHI during the NYSE floor closure period but a decrease in order volume HHI as shown by the estimate −0.2052 in column (2). NYSE-listed stocks appear to be consolidated in terms of order volume, but the execution of orders appears to be more fragmented and may be explained by the upcoming results in Table 5 , where there is an increase in average trade size during this period. These larger trade sizes may potentially increase order queues thereby increasing the time to execution and forcing orders to be routed to alternative venues (Hendershott and Mendelson, 2000).19

Table 5.

DiD regression: midas measures around NYSE floor closing and reopening: reports the regression analysis to examine specific MIDAS measures around the NYSE floor closing and reopening during COVID-19 using a difference-in-difference fixed effect model. The dependent variables are winsorized at the 1% level and standardized. These variables include: inverse Trade-to-Order, Odd-to-Volume, Cancel-to-Trade, inverse Trade Size, Hidden-to-Volume, and Hidden Size. To allow for the similar interpretations we use the inverse of Trade-to-Order and Avg. Trade Size. NYSE Close is a dummy variable equal to one for all dates starting on March 23, 2020 and ending before May 26, 2020, and 0 for all date in Floor Reopening period (May 26, 2020 – September 30, 2020). NYSE is equal to 1 if the stock is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the NYSE floor closing and reopening had on NYSE and NASDAQ-listed securities. Control variables include the natural log of the firm's market capitalization, price, and volume. All regression standard errors are clustered by stock and date and include both stock and day fixed effects (unless otherwise specified). T-statistics are recorded in the parentheses and asterisks ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Trade-to-Order* | Odd-to-Volume | Cancel-to-Trade | Trade Size* | Hidden-to-Volume | Hidden Size |

| NYSE | −0.0695 | −0.3254*** | −0.0010 | −0.3423*** | 0.1824*** | 0.1427*** |

| (1.50) | (6.99) | (0.02) | (6.78) | (4.65) | (4.36) | |

| NYSE Close | −0.4728*** | −0.6744*** | −0.3086*** | −0.5828*** | 1.0532*** | 0.4474*** |

| (7.73) | (13.77) | (4.91) | (12.09) | (10.61) | (13.17) | |

| NYSE Close * NYSE | 0.0366 | 0.0107 | −0.0244 | 0.1230*** | 0.1482*** | −0.0675*** |

| (0.89) | (0.30) | (0.57) | (3.40) | (2.97) | (2.78) | |

| Log Market Cap. | 0.5744*** | 0.5154*** | 0.5287*** | 0.5532*** | −0.2161*** | −0.3735*** |

| (15.25) | (11.85) | (15.16) | (11.87) | (6.47) | (12.39) | |

| Log Price | −0.4882*** | −0.3682*** | −0.4984*** | −0.3136*** | 0.4812*** | 0.2160*** |

| (10.21) | (6.92) | (10.67) | (5.06) | (11.62) | (5.29) | |

| Log Volume | −0.4515*** | −0.4582*** | −0.4223*** | −0.4729*** | 0.2054*** | 0.3229*** |

| (14.38) | (12.09) | (15.13) | (11.09) | (7.48) | (12.09) | |

| Constant | −4.2693*** | −3.3475*** | −3.8686*** | −4.0828*** | 0.3069 | 2.6746*** |

| (9.88) | (7.69) | (9.28) | (9.00) | (0.66) | (8.58) | |

| Observations | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 | 196,323 |

| R-squared | 0.0734 | 0.1863 | 0.0830 | 0.1629 | 0.1647 | 0.1010 |

| Number of Stocks | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 | 1460 |

| Day Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Day Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Despite NYSE-listed stocks being more fragmented on average during the NYSE Floor closure period, we interpret the significant coefficient –0.2849 for NYSE Close in column (1) to imply that the overall consolidation of trade volume is consistent with orders executing at lit venues rather than off-exchange venues during this period of excessive volatility. Columns (4) through (9) report results analyzing the dynamics of exchange competition, given the removal of floor traders at the NYSE and the benefits these traders provide to modern financial markets such as better market quality and price efficiency (Brogaard et al., 2021). During the floor closure period, there is a dynamic shift in order executions during the NYSE Floor closure. NYSE stocks trade more at the NYSE during the floor suspension period than NASDAQ stocks, as shown by the interaction variable in column (4). During the removal of floor traders at the NYSE, volume in NYSE-listed stocks appears to move to other NYSE group exchanges. In columns (6) through (9), we find that the coefficients for the interaction term are associated with a significant increase in other exchange market share and NYSE group market share (0.0423 and 0.3114, respectively), but are associated with a significant decrease in NASDAQ and CBOE group markets shares (−0.4914 and −0.1734, respectively).

Next, we examine the impact that the NYSE floor closure period has on proxies for AT given the drift in abnormal volatility we see during the MU period. We also determine if the findings in Table 3, where algorithmic traders appear to retract from the market, continues into this floor closure period. The univariate results suggest that exogenous liquidity providers are still absent during this period and the findings in Table 5 are consistent with this conjecture. There is significantly less AT activity during NYSE floor close than NYSE reopening period. All AT proxies and inverses are in the expected direction and there is a significantly negative association whereby the parameter estimates range from –0.3086 (cancel-to-trade) to −0.6744 (odd-to-volume). Moreover, the decline in proxies for AT is consistent among all stocks as there is little difference between NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed stocks. The effects we report in Table 3 appear to persist during the NYSE Floor closure period, and again are consistent with Kirilenko et al. (2017) that intraday intermediation become less active during stressful trading conditions.

In columns (5) and (6) of Table 5, there is elevated hidden trading activity that persists into the floor closure period, whereby the coefficient for NYSE Close on hidden-to-volume is 1.0532 and the average trade size coefficient is 0.4474. Furthermore, the interaction coefficients in columns (5) and (6) of Table 5 imply that despite larger overall average hidden trade size, NYSE stocks have significantly smaller average hidden size than NASDAQ stocks.

3.4. Market liquidity

Thus far, the MU period and the NYSE floor closure period present similar trends in market dynamics and algorithmic trading activity. Stocks are on average more consolidated in terms of both order and trade volume for both NYSE and NASDAQ stocks and consistent with Menkveld et al. (2017) and Ibikunle and Rzayev (2020), that during periods of high volatility and immediacy, orders that typically execute at off-exchange venues are now executing at lit exchanges. To determine what impact these changes in market dynamics and AT activity have on market quality, we report the results for Eq. (5) where the dependent variables are the standardized CRSP spread and Amihud illiquidity measures.

Panels A and B of Table 6 report the results for Eq. (5), where the dependent variable in Panel A is CRSP spread and in Panel B the dependent variable is Amihud illiquidity. There are several findings regarding the relation between liquidity and market dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, columns (1) and (2) in both Panels A and B report the DiD estimates for each period of analysis and consistent with Brogaard et al. (2021), there is substantial deterioration in liquidity measured by both spreads and Amihud illiquidity. The coefficients for MU (2.5620, see column 1) and NYSE Close (1.8892, see column 2) report a significant increase in spreads, as well as a significant increase in Amihud illiquidity (2.3286 and 1.2668, respectively). However, despite the overall deterioration in liquidity, the effects are not symmetric for NYSE and NASDAQ stocks. The interaction terms in both columns show that NYSE stocks, while there is a deterioration in liquidity, have tighter spreads and less illiquidity than NASDAQ stocks.

Table 6.

DiD regression: low frequency spread and liquidity around the COVID-19 Period: reports the regression analysis to examine liquidity around the COVID-19 pandemic period. Liquidity is measured via low frequency metrics, which include the CRSP Spread in Panel A and the Amihud (2002) illiquidity measure in Panel B. NYSE Close is a dummy variable equal to one for all dates starting on March 23, 2020 and ending before May 26, 2020, and 0 for all date in Floor Reopening period (May 26, 2020 – September 30, 2020). NYSE is equal to 1 if the stock is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the NYSE floor closing and reopening had on NYSE and NASDAQ-listed securities. MU is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all dates from February 24, 2020 to the close of the NYSE Floor on March 23, 2020, and 0 for all date prior to this period. NYSE is equal to 1 if the stock is a NYSE-listed stock and 0 if it is a NASDAQ-listed stock. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that the Market Uncertainty period had on NYSE and NASDAQ-listed securities. Other variables of interest include Trade and Order Volume Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (1-HHI), Odd lot volume-to-Trade, Trade-to-Order, Cancels-to-Trades, Avg. Trade Size, Hidden volume-to-Trade, and Avg. Hidden Trade Size. All dependent variables and variables of interest are winsorized at 1% level and standardized. Control variables include the natural log of the firm's market capitalization, price, and volume. All regression standard errors are clustered by stock and date and include both stock and day fixed effects (unless otherwise specified). T-statistics are recorded in the parentheses and asterisks ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

| Panel A: spread | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

| NYSE | 0.0145 | −0.1944** | ||||||||

| (1.11) | (2.11) | |||||||||

| MU | 2.5620*** | |||||||||

| (4.96) | ||||||||||

| MU *NYSE | −1.1647*** | |||||||||

| (3.40) | ||||||||||

| NYSE Close | 1.8892*** | |||||||||

| (7.89) | ||||||||||

| NYSE Close * NYSE | −1.6100*** | |||||||||

| (10.01) | ||||||||||

| Trade-to-Order* | 0.0029 | |||||||||

| (0.14) | ||||||||||

| Odd-to-Volume | −0.0660* | |||||||||

| (1.80) | ||||||||||

| Cancel-to-Trade | −0.0316 | |||||||||

| (1.05) | ||||||||||

| Trade Size* | −0.0393 | |||||||||

| (1.26) | ||||||||||

| Hidden-to-Volume | 0.3274*** | |||||||||

| (7.57) | ||||||||||

| Hidden Size | 0.0207 | |||||||||

| (1.16) | ||||||||||

| HHI Trade Volume | −0.1749*** | |||||||||

| (6.75) | ||||||||||

| HHI Order Volume | −0.1125*** | |||||||||

| (3.73) | ||||||||||

| Log Market Cap. | −0.0271 | 0.1858*** | −0.1378** | −0.1023 | −0.1216** | −0.1161* | −0.0272 | −0.1285** | −0.1318** | −0.1265** |

| (0.62) | (3.15) | (2.33) | (1.64) | (2.11) | (1.85) | (0.53) | (2.07) | (2.09) | (2.05) | |

| Log Price | −0.1002*** | −0.4684*** | −0.1454** | −0.1726*** | −0.1607*** | −0.1605*** | −0.2906*** | −0.1521** | −0.1355** | −0.1303** |

| (3.03) | (5.43) | (2.38) | (2.81) | (2.68) | (2.61) | (4.94) | (2.45) | (2.20) | (2.05) | |

| Log Volume | 0.0537 | 0.1008** | 0.2790*** | 0.2457*** | 0.2647*** | 0.2594*** | 0.1635*** | 0.2707*** | 0.2738*** | 0.2651*** |

| (1.06) | (2.02) | (4.69) | (3.85) | (4.55) | (4.03) | (3.30) | (4.33) | (4.34) | (4.31) | |

| Constant | 0.2400 | −2.8161*** | 0.5938 | 0.3597 | 0.4867 | 0.4390 | 0.1148 | 0.5276 | 0.4463 | 0.4569 |

| (0.86) | (4.12) | (1.14) | (0.68) | (0.95) | (0.83) | (0.23) | (0.99) | (0.82) | (0.86) | |

| Observations | 173,397 | 196,323 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 |

| R-squared | 0.0196 | 0.0386 | 0.0055 | 0.0058 | 0.0056 | 0.0056 | 0.0140 | 0.0056 | 0.0076 | 0.0065 |

| Day & Stock FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Day & Stock Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Panel B: Amihud Illiquidity | ||||||||||

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

| NYSE | −0.0028 | 0.2876*** | ||||||||

| (0.22) | (5.07) | |||||||||

| MU | 2.3286*** | |||||||||

| (5.38) | ||||||||||

| MU *NYSE | 0.6885*** | |||||||||

| (4.27) | ||||||||||

| NYSE Close | 1.2668*** | |||||||||

| (6.43) | ||||||||||

| NYSE Close * NYSE | 0.4485*** | |||||||||

| (4.78) | ||||||||||

| Trade-to-Order* | 0.0075 | |||||||||

| (0.27) | ||||||||||

| Odd-to-Volume | −0.1817*** | |||||||||

| (5.25) | ||||||||||

| Cancel-to-Trade | −0.0230 | |||||||||

| (0.55) | ||||||||||

| Trade Size* | −0.1273*** | |||||||||

| (4.21) | ||||||||||

| Hidden-to-Volume | 0.3817*** | |||||||||

| (7.89) | ||||||||||

| Hidden Size | 0.0182 | |||||||||

| (0.83) | ||||||||||

| HHI Trade Volume | −0.1077*** | |||||||||

| (6.68) | ||||||||||

| HHI Order Volume | −0.1194*** | |||||||||

| (5.08) | ||||||||||

| Log Market Cap. | 0.1119*** | 0.3567*** | −0.0538 | 0.0443 | −0.0391 | 0.0159 | 0.0784* | −0.0430 | −0.0472 | −0.0394 |

| (3.04) | (6.41) | (0.97) | (0.83) | (0.75) | (0.29) | (1.66) | (0.71) | (0.74) | (0.63) | |

| Log Price | −0.2649*** | −0.8401*** | −0.4059*** | −0.4809*** | −0.4196*** | −0.4542*** | −0.5789*** | −0.4142*** | −0.4024*** | −0.3917*** |

| (5.85) | (11.17) | (7.42) | (8.84) | (7.78) | (8.31) | (10.42) | (7.34) | (7.04) | (6.83) | |

| Log Volume | −0.1178*** | −0.4214*** | 0.0192 | −0.0730 | 0.0063 | −0.0439 | −0.1189*** | 0.0096 | 0.0134 | 0.0023 |

| (3.99) | (8.07) | (0.37) | (1.46) | (0.13) | (0.85) | (2.92) | (0.17) | (0.22) | (0.04) | |

| Constant | 0.0670 | 1.5778*** | 3.3131*** | 2.6675*** | 3.2157*** | 2.8149*** | 2.7444*** | 3.2373*** | 3.2021*** | 3.1493*** |

| (0.13) | (2.92) | (5.95) | (4.99) | (5.98) | (5.22) | (4.96) | (5.56) | (5.20) | (5.21) | |

| Observations | 173,397 | 196,323 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 | 369,720 |

| R-squared | 0.1159 | 0.2155 | 0.0273 | 0.0338 | 0.0274 | 0.0308 | 0.0730 | 0.0274 | 0.0305 | 0.0314 |

| Day & Stock FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Day & Stock Clustered SE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

In Tables 3 and 5, algorithmic traders retract from the market when compared to all periods surrounding COVID-19 and this effect is consistent across all stocks. In columns (3) through (6) of Table 6, we provide the results from individual regressions for all AT proxies, where we determine what relation exists between AT and market liquidity. AT literature remains divided regarding the effect that these traders have on market quality. However, both Panels A and B show results partially consistent with the strand of literature indicating that these types of traders tend to reduce trading costs, lower short-horizon volatility, absorb trade imbalances, increase depth, correct transitory price movements, and provide net positive effects on liquidity provision (Hendershott et al., 2011; Menkveld, 2013; Brogaard et al., 2014; Conrad et al., 2015; Boehmer et al., 2018b; Brogaard et al., 2018). The proxies for AT and their inverses in Panel A and B show that when algorithmic traders are more active throughout the sample, they provide beneficial liquidity as shown by the significant negative coefficients for odd-to-volume and the inverse of trade size measures.

Lastly, in Columns (9) and (10) of Panels A and B for Table 6, we regress trade and order volume HHI on the liquidity metrics. As fragmentation increases, stocks experience better liquidity by tightening spreads and less illiquidity measured by Amihud Illiquidity. Both trade and order HHI report a significant negative coefficient of –0.1749 and –0.1125, respectively, and a negative association with Amihud Illiquidity of –0.1077 and –0.1194, respectively. These findings are consistent with O'Hara and Ye (2011) and Gresse (2017) that fragmentation leads to better liquidity through lower transaction costs and faster execution speed.

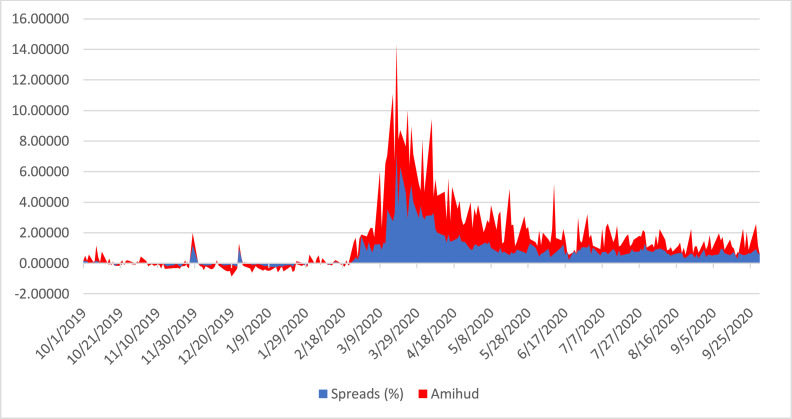

Fig. 6 shows the time-series variation in spreads and illiquidity. In the stacked-area chart, the Amihud illiquidity (spreads) are shaded in red (blue). The standardized measures of each liquidity measure spike somewhere near the end of March. However, it does appear that illiquidity peaks sometime before spreads, indicating that although both measures are highly correlated, there is some degree of a lead-lag relation.

Fig. 6.

Spreads and illiquidity. This figure shows the time-series of standardized measures of spreads and illiquidity for our sample of securities. The stacked-area plot is shaded red (blue) for Amihud illiquidity (percentage spreads). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

Our last series of tests examine the impact of AT proxies on liquidity during the market uncertainty period given the concerns that algorithmic traders withdrew from the market, exacerbating illiquidity in the market. Thus, we estimate the following regression:

| (6) |

where refers to one of our four previously defined proxies of AT. refers to the market uncertainty period as defined earlier. The interaction term, , captures the difference-in-difference (DiD) estimates between the effect that either the market uncertainty period and AT had on spreads and illiquidity.

The results in Table 7 indicate that controlling for the market uncertainty period, the impact of the individual AT proxies on liquidity is negligible. Regardless of the dependent variable, spread or Amihud illiquidity, none of the coefficient estimates for the AT proxies are significant. Simultaneously, the estimate for MU is positive and significant in all regressions – indicating that spreads and illiquidity increased significantly during the market uncertainty period. However, we find that the interaction term is negative and significant in six of the eight regressions, which confirms that despite withdrawing from the market during the market uncertainty period, the remaining algorithmic traders reduce spreads and mitigate illiquidity. This last result contrasts with market commenters that posited AT intensified illiquidity during the COVID-19-induced market instability period.20

Table 7.

DiD Regression: algorithmic trading effects on liquidity during market uncertainty reports the regression analysis to examine liquidity around the COVID-19 pandemic period. Liquidity is measured via low frequency metrics, which include the CRSP Spread as a% and the (Amihud, 2002) illiquidity measure. MU is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all dates from February 24, 2020 to the close of the NYSE Floor on March 23, 2020, and 0 for all date prior to this period. The interaction, gives the difference-in-difference estimates between the effect that algorithmic trading during the Market Uncertainty period had on liquidity for all securities. Algorithmic Trading (AT) measures include Cancel-to-Trade, Odd-to-Volume, Trade-to-Order, and Trade Size. Both the Trade-to-Order* and Trade Size* variables are inverted so that the coefficient estimates can be interpreted similarly to that of Cancel-to-Trade and Odd-to-Volume. All dependent variables and variables of interest are winsorized at 1% level and standardized. Control variables include the natural log of the firm's market capitalization, price, and volume. All regression standard errors are clustered by stock and date and include both stock and day fixed effects (unless otherwise specified). T-statistics are recorded in the parentheses and asterisks ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

| Spread% | Spread% | Spread% | Spread% | Amihud | Amihud | Amihud | Amihud | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancel-to-Trade | 0.0001 (0.52) | 0.0000 (0.09) | ||||||

| Odd-to-Volume | 1.3523* (1.82) | 2.5115*** (3.14) | −0.0005 (1.48) | |||||

| Trade-to-Order* | 0.0004 (1.00) | −0.2060 (0.09) | ||||||

| Trade Size* | 13.42 67** (2.08) | |||||||

| MU | 3.0710*** (4.22) | 3.1662*** (3.72) | 2.8285*** (4.21) | 3.0718*** (3.73) | 3.7237*** (4.89) | 2.5406*** (4.61) | 1.4355*** (4.89) | 1.1112*** (4.17) |

| Cancel-to-Trade x MU | −0.0698*** (2.80) | −0.0676*** (2.78) | ||||||

| Odd-to-Volume x MU | −4.2539** (2.29) | 0.2110 (0.31) | ||||||

| Trade-to-Order* x MU | −0.0259*** (2.63) | −0.0089** (2.35) | ||||||

| Trade Size* x MU | −63.0832** (2.29) | 1.7347 (0.33) | ||||||