Abstract

The incidence of urolithiasis (UL) is increasing, and it has become more common in children and adolescents over the past few decades. Hypercalciuria is the leading metabolic risk factor of pediatric UL, and it has high morbidity, with or without lithiasis as hematuria and impairment of bone mass. The reduction in bone mineral density has already been described in pediatric idiopathic hypercalciuria (IH), and the precise mechanisms of bone loss or failure to achieve adequate bone mass gain remain unknown. A current understanding is that hypercalciuria throughout life can be considered a risk of change in bone structure and low bone mass throughout life. However, it is still not entirely known whether hypercalciuria throughout life can compromise the quality of the mass. The peak bone mass is achieved by late adolescence, peaking at the end of the second decade of life. This accumulation should occur without interference in order to achieve the peak of optimal bone mass. The bone mass acquired during childhood and adolescence is a major determinant of adult bone health, and its accumulation should occur without interference. This raises the critical question of whether adult osteoporosis and the risk of fractures are initiated during childhood. Pediatricians should be aware of this pediatric problem and investigate their patients. They should have the knowledge and ability to diagnose and initially manage patients with IH, with or without UL.

Keywords: Children, Adolescents, Hypercalciuria, Bone mineral density, Kidney stone

Core Tip: The incidence of pediatric urolithiasis is increasing, and hypercalciuria is its leading metabolic risk factor. The reduction in bone mass has already been described in hypercalciuric children, and the precise mechanisms of bone loss or failure to achieve adequate bone mass remain unknown. The peak bone mass is achieved by late adolescence, peaking at the end of the second decade of life. This accumulation should occur without interference. The bone mass acquired during childhood and adolescence is the major determinant of adult bone health. Pediatricians should have the knowledge and ability to diagnose and manage pediatric patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria.

INTRODUCTION

Urolithiasis: A public health concern

Renal, ureteral and bladder stones are present in pediatric clinics and are the end product of a multifactorial process. No age or ethnic group is protected from this clinical problem that commonly afflicts humanity[1].Urolithiasis (UL) is an uncommon cause of death or end-stage renal disease; however, it represents a significant public health problem because its recurrence is a marked characteristic and confers high morbidity. No stone removal technique can decrease this recurrence or change its morbidity, which in pediatric patients is directly related to surgical interventions, to morphofunctional alterations resulting from possible obstructions of the urinary tract, and also to its clinical manifestations. In addition, they have a high potential for complications, as the symptoms are often nonspecific[2].

Incidence and prevalence

The risk of forming a new stone increases with age in patients who have already had it. Thus, the estimated risk of forming a new stone in one year is 15%, 35-40 % in five years and 80 % in ten years[3]. Its prevalence varies according to varied factors such as ethnicity, geographical location, water consumption of that population and age group. Despite being more common in whites and men, new studies have shown that UL is becoming more common in female and black patients[4].

Data on the prevalence and incidence of urinary tract stones in childhood are still scarce in the literature. The true incidence of this disease remains unknown due to the multiplicity of etiopathogenic factors and the non-specificity of the clinical onset. Variations in this incidence are found from 1:1714 to 1:9500 cases in different regions of the United States. However, it is believed that the prevalence is 5% in white North American children[5].

Urinary stones can occur anywhere in the renal collecting system. In industrialized countries, 97% of urinary stones are found in the parenchyma, pelvis, papillae and calyxes, while only 3% in the bladder and urethra. Bladder stones are more frequent in developing countries. The formation of stones in the kidneys and urinary tract is dependent on crystals and matrix, and its constituents are, in most cases, different organic and inorganic substances with a crystalline or amorphous structure. Only one-third of urinary stones have only one mineral in its composition, with calcium oxalate being the most common and found in at least 65% of all stones[2,6].

Risk factors

Several factors are involved in urinary stones formation, such as: infectious, anatomical, epidemiological, climatic, socioeconomic, dietary, genetic and metabolic. These factors, combined with physicochemical and physiological changes in the urine, alter the elements that promote and inhibit the aggregation and growth of crystals, culminating in the formation of stones[6]. However, the etiopathogenesis of UL remains unclear, and multiple aspects still have no explanation.

Crystallization begins when the urine is supersaturated for a particular solute. If the solution is unsaturated, crystals do not form. Supersaturation depends on ionic strength, abnormalities in urinary pH, reduced urinary volume, deficiency of crystallization inhibitors (citrate, magnesium, pyrophosphate, nephrocalcin, glycosaminoglycans) and the hyperexcretion of calcium, uric acid, phosphorus and more rarely of oxalate and cystine. However, it is not clear how the crystals formed in the tubules become calculi since they are continuously washed away by the urine flow. It is believed that these aggregated crystals reach a certain dimension that allows an anchoring process, usually at the end of the collecting ducts and, slowly, they increase in size over time. This anchoring process is likely to be induced by the crystals themselves and occurs in damaged sites of the tubular epithelial cell. Currently, new studies on the etiopathogenesis of UL and molecular biology have contributed to these new discoveries. The identification of other molecules in the urine with inhibitory capacity for crystallization, as well as the new principles of adhesion of the crystals in the renal tubular epithelium and the endocytosis suffered by the calcium oxalate crystals in the renal tubular cells, are the main examples[7,8].

Some factors are considered main risks for UL, such as excessive salt and animal protein intake, low water intake, use of lithogenic drugs, genetic inheritance and dietary calcium restriction[6]. Unlike what happens in adult patients, overweight and obesity still do not show consistent scientific evidence for pediatric patients with UL[6]. The high sodium intake in healthy people induces an increase in urinary calcium excretion. Experimental studies show that the increase in fractional excretion of sodium in the proximal tubule produces an increase in fractional excretion of calcium in this same tubule, with consequent hypercalciuria, determining a positive correlation between natriuria and calciuria. A high amount of salt in the diet also determines a reduction in citrate excretion by mechanisms not yet known[9,10].

Penido et al[11] demonstrated that healthy children and adolescents ingested a higher amount of sodium and proteins and lower amounts of calcium than recommended by the RDA, in all age groups, in a Brazilian pediatric cohort. The authors also found a positive correlation between urinary sodium and calcium excretion (r = 0.74; P < 0.01)[11]. The high animal protein intake increases the production of fixed acids, causing transient metabolic acidosis. Consequently, there is an increase in urinary calcium excretion, accompanied by urinary pH reduction, hyperexcretion of uric acid, oxalate, and hypoexcretion of citrate, predisposing to UL[6,11].

Oliguria is also a significant risk factor for stone formation. Maintaining adequate urine volume is essential to ensure the solubility of substances excreted in the urine. The reduced urine output is a consequence of decreased water intake, which increases the saturation of solutes and predisposes to the formation of urinary calculi. Studies have shown that calcium oxalate supersaturation increased significantly once urine output decreased to less than 1.0 mL/kg per hour[6,12].

Drugs that promote crystalluria such as sulfadiazine, triamterene, indinavir and ceftriaxone favor the formation of calculi. Inappropriate use of antibiotics is also related to the formation of urinary stones[13]. Oxalate is degraded by Oxalobacter formigenes, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Escherichia coli, and others that reduce its intestinal absorption and protect against the formation of stones. Antibiotics alter the intestinal microbiome and consequently the oxalate metabolism. Exposure to any of the five main classes of antibiotics in the 3-12 mo prior to calculi formation was associated with an increased risk of stones (sulfas, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, nitrofurantoin and penicillin). The magnitude of this association was higher for exposure at younger ages and 3-6 mo before the diagnosis of UL[13].

Mode of Inheritance

Individuals with a positive family history of UL have a relative risk of developing urinary stones 2.57 times greater after an eight-year period when compared to those without. Cystinuria and primary hyperoxaluria are monogenic diseases whose mutations were already described. However, it is in IH that this genetic involvement has been widely studied, and 40% of patients with this disease have a family history of UL. Experimental models have suggested a possible dominant inheritance for IH. Polymorphism of vitamin D receptor genes has also been linked to urinary calcium excretion. It seems to represent one of the genetic factors that affect bone mineral density, although it only partially contributes to the genetic effect on bone mass, and this is not observed in all evaluated populations[14,15].

Metabolic disturbances

Important calcium restriction in the diet determines an increase in urinary oxalate excretion and, consequently, an increased risk for the aggregation of calcium oxalate crystals. In addition, they can facilitate the occurrence of reduced bone mineral density (BMD)[22]. Metabolic alterations are responsible for 80% to 90% of stone formation in adults as well as in childhood. The most common alterations in pediatric patients are hypercalciuria, hypocitraturia, and low urine output[2,6,16]. As aforementioned, the IH is the leading metabolic risk factor for UL, and it has become more common in children over the past few decades. It has high morbidity with or without UL, and reduced BMD was already described in pediatric patients[16].

HYPERCALCIURIA

In 1953 Albright et al[17] used the term “idiopathic hypercalciuria” for the first time. In 1962, Valverde published his firsts Spanish pediatric cases[18]. In the same year, two pediatric groups reported six cases of children with hypercalciuria, osteopenia or rickets, nanism and renal impairment. The authors proposed that those cases would be IH; however, the patients were probably carriers of other tubulopathies[19]. After this publication, others emerged discussing the definition of criteria regarding “primary/idiopathic hypercalciuria” (see below).

IH is a metabolic disorder that affects all ages, genders and race groups[2,20,21]. It has a high prevalence and is the major risk factor to UL in children[2,20] and adults[22]. The “true” IH is a clinical condition characterized by increased urinary calcium excretion in the absence of hypercalcemia or other clinical conditions that can cause hypercalciuria and when dietetic disturbances have been excluded[23-25]. Its incidence in the pediatric group range between 2.2%-6.2%[25] and the prevalence between 0.6% and 12.5%. In Spain, prevalence rates vary between 3.8% and 7.8%[23].

Hypercalciuria is defined as urinary calcium excretion higher than or equal to 4 mg/kg/d for any gender or age[11,26]. Another clinical definition is the random or spot urinary calcium/creatinine ratio. It could be especially useful for children who do not have urinary sphincter control (Table 1)[11,26]. It is important to highlight that young children and infants have higher urinary calcium excretion and lower urinary creatinine levels. Then, the calcium/creatinine ratios differ by age (Table 1)[11,26]. Normal values for the lithogenic substances are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Normal values for random urine and 24 h urine factors for children and adolescents

|

|

24 h urine

|

Random urine corrected by creatinine

|

Random urine factored for GFR

|

|||

| Volume | ≥ 1.0 mL/kg per h | |||||

| Creatinina | 2 to 3 yr: 6 to 22 mg/kg; > 3 yr: 12 to 30 mg/kg | |||||

| Calcium | < 4.0 mg/kg (0.10 mmol/kg) | Age | mg/mg; mmol/mmol | < 0.10 | ||

| 0-6 mo | < 0.80; < 2.24 | |||||

| 6-10 mo | < 0.60; < 1.68 | |||||

| 1-2 yr | < 0.40; < 1.12 | |||||

| 2-18 yr | < 0.21; < 0.56 | |||||

| Citrate | ≥ 400 mg/g creatinine | ≥ 0.28 (mmol/L/mmol/L) | > 0.18 (mg/L/mg/L) | |||

| Calcium/Citrate | < 0.33 | < 0.33 | ||||

| Na/K | < 3.5 | < 3.5 | ||||

| Uric acid | < 815 mg/1.73m2 BS | < 0.65 | < 0.56 mg; < 0.03 mmol | |||

| Cystine | < 60 mg/1.73 m2 BS | < 0.02 (mg/mg); < 0.01 (mmol/mmol) | ||||

| Magnesium | > 88 mg/1.73 m2 BS | |||||

| Phosphate | TP/GFR1: > 2.8 and < 4.4 mg/dL | |||||

| Oxalate | < 50 mg/1.73m2 BS; < 0.49 mmol/1.73m2 BS | Age | (mg/mg) | |||

| 0-6 mo | < 0.30 | |||||

| 7 mo - 4 yr | < 0.15 | |||||

| > 4 yr | < 0.10 | |||||

TP/GFR = Pp – (Pu × Crp)/Cru.

GFR: Glomerular filtration rate; TP: Tubular phosphate reabsorption; Pp: Plasma phosphate; Pu: Urinary phosphate; Crp: Plasma creatinine; Cru: Urinary creatinine. Adapted from: Penido MGMG, Tavares MS. Pediatric primary urolithiasis: Symptoms, medical management and prevention strategies. World J Nephrol 2015; 4: 444-454. Copyright ©The Author(s) 2015. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc[2].

IH can be related to two conditions: UL and bone resorption. Studies have demonstrated that hypercalciuric calcium stone formers have decreased BMD when compared to matched controls which are neither stone formers nor hypercalciuric[27,28]. Among adults patients with UL, those with hypercalciuria will have BMD measurements 5% to 15% lower than their normocalciuric matched controls[27]. Several studies have also demonstrated reductions in BMD in hypercalciuric pediatric patients with or without hematuria or UL[16,29-34]. This review discusses the association between UL, IH and reduced BMD in pediatric patients and the importance of this association for the clinical practice of pediatricians.

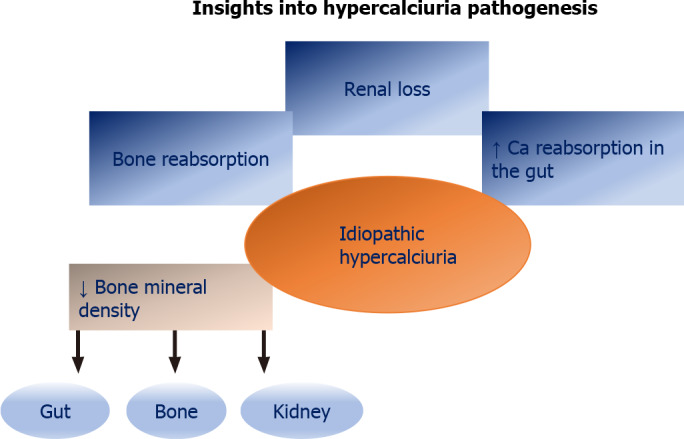

PATHOGENESIS OF HYPERCALCIURIA

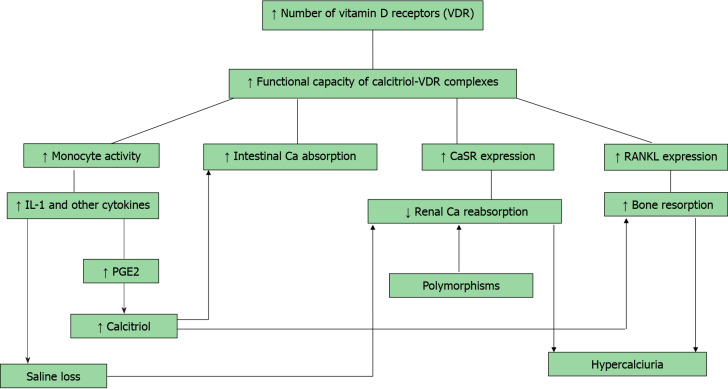

The pathogenesis of IH is complex and not yet completely understood. We would say that the excretion of calcium in urine is the end result of an interplay between three organs: the kidneys, bones and gastrointestinal tract. These organs are orchestrated by hormones, such as parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitonin, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2D3), fibroblast growth factor (FGF23), and probably others unknown, acting together as a unique system. It seems that IH is a systemic abnormality with alterations in calcium cellular transport in kidneys, bones and intestines (Figure 1)[22,35,36].

Figure 1.

Insights into hypercalciuria pathogenesis (Source: Nephrology Center of Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte - Pediatric Nephrology Unit - by Penido MGMG).

In 1965, Edwards & Hodgkinson started the first studies on the pathogenesis of IH and concluded that its origin should be exclusively renal[37]. Chronic loss of calcium by the kidneys would lead to a reduction in serum calcium, and consequently, an increase in serum PTH. Considering this, Pak et al[38] in 1974 observed normal levels of PTH in their hypercalciuric patients and ruled out the possibility that IH was exclusively of renal origin. The same authors proposed a test (acute oral calcium overload test) to distinguish two types of IH, according to the underlying pathophysiological mechanism: absorptive or renal. They classified IH into three distinct pathogenetic pathways: (1) Absorptive hypercalciuria type I (primary intestinal hyperabsorption of calcium); (2) Absorptive hypercalciuria type III (primary renal leak of phosphate); and (3) Renal hypercalciuria (primary renal leak of calcium)[39]. These authors also identified the so-called resorptive hypercalciuria when hypercalciuria is induced by an excessive calcium output from bones. However, the clinical value of the classification was limited, and it is often impossible to classify the patient into a specific type, as described by Aladjem et al[40] (1996) in children. Thus, this test and this classification fell out of use.

Alhava et al[41] demonstrated that their patients with UL had significantly lower BMD values when compared to controls. In the 1980s, with the assessment of 1,25OH vit. D, it was proven that some of these patients with urinary stones had high levels of this vitamin[42]. The hypothesis of intestinal IH was again highlighted. Buck et al[43] treated 43 patients with HI and hyperproduction of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) with indomethacin. The authors confirmed the normalization of the calciuria and suggested that PGE2 could be implicated in the origin of IH[43]. Henriquez-La Roche et al[44] have also shown an increase in PGE2 in patients with IH.

Urinary phosphate loss was related to IH, and when hyperphosphaturia is important, it favors hypophosphatemia. The reduction in serum phosphate levels favors calcitriol synthesis, increasing intestinal calcium absorption and, consequently, hypercalciuria. A study by Prié and co-workers showed that 20% of hypercalciuric stone-formers with normal PTH have a decreased TmP/GFR (tubular phosphate reabsorption / glomerular filtration rate) value and phosphaturia[45].

Pacifici et al[46] demonstrated that blood monocytes from patients with IH produced an increased amount of cytokines: interleukin-1 (IL-1), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha). The increased activity of these cytokines had the ability to reduce BMD in patients with IH, and other studies confirmed these findings[47,48].

Weisinger[49] proposed a new theory on the pathophysiology of HI that combined the findings already published: IL-1 and the other cytokines would stimulate bone resorption[46-48] and the production of PGE2 [44]that induced the synthesis of calcitriol[50]. It is known that an excessive amount of calcitriol stimulates bone resorption[50]. Thus, hypercalciuria would be caused by an increase in bone resorption and an increase in intestinal calcium absorption due to the effect of calcitriol.

Inflammatory mediators such as IL-1 and TNF reduce the epithelial sodium transport due to increased PGE2 synthesis[51] and reduced expression of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and/or Na + -K + -ATPase in the basolateral membrane[52]. A slight distal saline loss has been described in some adult patients, and this loss of sodium would increase urinary calcium[53]. These patients could have a triple origin for IH: bones, intestines and kidneys.

Rats with spontaneous hypercalciuria (genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming - GHS) were identified, and an increase in calciuria was observed in each successive generation of them[54]. Bushinsky and Favus observed that these rats had excessive calciuria due to an increase in the intestinal absorption of this ion, although calcitriol levels were normal[54]. When the rats were submitted to a calcium-restricted diet, the calciuria decreased, suggesting that the mechanism of hypercalciuria observed in these animals was the increase in intestinal calcium absorption[55]. A higher number of vitamin D receptors (VDR) in the intestine of these rats was demonstrated, favoring the functional capacity of calcitriol-VDR complexes[55]. Yao et al[56] found that these animals had an increased response to VDR with minimal calcitriol levels, thus causing hypercalciuria. However, this loss of calcium was greater than dietary intake, suggesting another pathogenic mechanism. In sequence, Krieger et al[57] demonstrated that this increase in sensitivity to calcitriol was expressed in the bones of these animals, inducing bone resorption, leading to a possible role of bones. Later, Tsuruoka et al[58] demonstrated that hypercalciuric rats have a tubular calcium reabsorption defect. This is due to an activation of the sensitive calcium receptor (CaR) that would suppress the activity of the calcium-sensitive potassium channel (ROMK) in ascending portion of the loop of Henle[59]. There is a reduction in the electrical gradient in the tubular lumen with a consequent reduction in the absorption of calcium by the paracellular pathway. Consequently, more calcium is delivered to the distal tubule. In humans, Worcester et al[60] showed that hypercalciuric stone-forming patients, eating fixed and identical high-calcium and regular diets, reduce distal and proximal tubule reabsorption more than controls. Favus et al[61] demonstrated that peripheral monocytes of humans with IH have an increased VDR number, as previously described in hypercalciuric rats[55]. Based on suggestions by Worcester and Coe[22] that variations in the klotho-FGF23 axis could mediate alterations in calcium and phosphate handling by the kidney and play a role in IH, Penido et al[62] decided to explore a potential role for FGF23 in pediatric IH. They concluded there was no difference in plasma FGF23 Levels between hypercalciuric and control children[62]. Pharmacologically treated patients had significantly lower urine calcium excretion rate and plasma FGF23 Levels; elevated TP/GFR and serum phosphate without changes in serum PTH values. It thus seems that the reversal of hypercalciuria may directly or indirectly affect phosphate metabolism[62]. Finally, what has been demonstrated in hypercalciuric rats has also been found in humans with IH: increased intestinal calcium absorption, defect in tubular calcium reabsorption, increased bone resorption, and normal serum calcium and calcitriol levels[61].

The excess sodium intake is accompanied by increased urinary calcium excretion and increased dietary protein intake[63,64]. Breslau et al[65] suggested that hypercalciuria induced by excess dietary sodium was accompanied by an increase in calcitriol synthesis. Excessive protein intake produces acid overload that inhibits renal tubular calcium reabsorption. The increase in net acid production is buffered by bones and other body buffers[63,65]. It could explain the reduction in BMD in IH. Bataille et al[66] observed a direct correlation between calciuria and urinary hydroxyproline in their patients, a marker of bone resorption.

The genetic background is also involved in the pathogenesis of IH. It has been described that patients with UL due to hypercalciuria can be carriers of genetic polymorphisms that encode certain proteins involved in the tubular reabsorption of calcium and phosphate (VDR, SLC34A1, SLC34A4, CLDN14, CaSR, TRPV6), or in the prevention of it precipitation of calcium salts (CaSR, MGP, OPN, PLAU, UMOD)[67-69]. Garcia Nieto et al[23] published a summary with all the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in IH described to date (Figure 1). According to the authors, it remains to be determined whether the cytokine-producing monocyte hyperreactivity described in IH is related to the increase in VDR in these cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cytokine-producing monocyte hyperreactivity described in IH is related to the increase in VDR in these cells. Adapted from: García-Nieto VM, Luis-Yanes MI, Tejera-Carreño P, Pérez-Suarez G, Moraleda-Mesa T. The idiopathic hypercalciuria reviewed: Metabolic abnormality or disease? Nefrologia 2019; 39: 592-602. Copyright ©The Author(s) 2019. Published by Elsevier España, S.L.U[23].

Another point to discuss is the role of vitamin D supplementation. This supplementation has been related to hypercalciuria. Milart et al[69] analyzed the impact of vitamin D supplementation on 36 children with IH and UL prospectively. Blood and urine samples were collected every three months up to 24 mo of vitamin D intake at a dose of 400 or 800 IU/d. Bone densitometry was performed at time 0, at 12, and 24 mo of vitamin D supplementation. The authors concluded that supplementation with vitamin D caused an increase in 25(OH) vit. D in serum[69]. However, no changes in serum calcium, urine calcium and bone density were observed. There was no significant increase in the risk of development of kidney stones[69].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF HYPERCALCIURIA IN PEDIATRICS

Pediatricians are professionals who assist children and adolescents with UL and IH. It is imperative that these professionals have knowledge about these clinical entities and how they present in pediatric patients. IH in children can present as gross or microscopic hematuria, voiding symptoms (urinary urgency, pollakiuria, dysuria, incontinence, enuresis and suprapubic pain), recurrent abdominal pain and flank pain in the absence of calculi, lumbar colic, urinary tract infections or enuresis and other voiding disorders[21,70,71]. Macro or microscopic hematuria and/or abdominal pain are the most common clinical presentations among hypercalciuric pediatric patients[21,25]. Unlike adults, lumbar colic is not common in children, and Penido et al[21] found only 14% of lumbar colic as first presentation. These different signs and symptoms can be confusing at the time of clinical presentation. Pediatricians should be aware of this diagnosis in children and adolescents who present clinically with urinary urgency and incontinence, suprapubic pain, nocturnal enuresis, pain in the urethra and recurrent chronic abdominal pain. In this sense, IH must be identified and monitored because it can have consequences other than hematuria, abdominal pain and kidney stones.

BONE CHANGES IN HYPERCALCIURIA

Reduced BMD has been described in adult patients with IH since the 1970s[41,47,48,66], and since then, it has been recognized that hypercalciuric patients with UL could exhibit a decrease in BMD. Different factors may be involved in bone loss in IH, such as negative calcium balance due to reduced tubular reabsorption, increased production of prostaglandin E2[44], increased cytokine reabsorption activity[46] and/or calcitriol[72]. An increased resorptive action of calcitriol would be related to an increased number of VDR[57].

Bone biopsies performed in a patient with IH showed an increase in osteoclastic activity[73], and in some series, a reduction in osteoblastic activity was observed[74]. Gomes et al[74] demonstrated a high expression of the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) in patients with IH, suggesting an increase in bone resorption mediated by this peptide. The authors found that expression of IL-1 and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) was similar to that of controls and consider that the high expression of cytokines, already described in hypercalciuric patients, could have no causal relationship with the reduction in bone mass. Therefore, Gomes et al[74] considered that the primary event would be the increase in VDRs, which favors the increase of the functional capacity of calcitriol-VDR complexes, increasing intestinal calcium absorption, and stimulating the bone expression of RANKL.

In 2020, Taguchi et al[75] performed a single-center retrospective cohort study to analyze patients with UL who underwent both BMD examination and 24 h urine collection. A total of 370 patients were included, and there was a positive correlation between BMD T-scores and urinary phosphate and citrate excretion. A lower BMD T-score was associated with increased odds ratios for stone symptoms during follow-up. The authors suggested that examining BMD could be a useful tool for effective follow-up of UL and may prevent future risks factors to urinary stones[75].

BONE CHANGES IN PEDIATRIC HYPERCALCIURIA

It is known that life-long hypercalciuria could be an important contributor to diminished bone mass or failure of adequate bone mass gain. In pediatric patients, the studies on IH began with Stapleton et al[20,76,77]. The authors used the acute oral calcium overload and found similar linear skeleton growth in both groups (renal and absorptive hypercalciuria)[77]. The same authors studied the BMD of their patients with IH and compared it with a control group. They found no significant differences in BMD between patients and controls or between patients with renal and absorptive hypercalciuria. Also, there was no correlation between BMD, PTH and osteocalcin[77]. Later, studies showed bone changes in pediatric patients with IH. Perrone et al[78] showed an improvement in lumbar spine BMD (compared to those untreated) in a prospective study with pediatric IH patients with absorptive type treated with dietary calcium restriction and/or rice bran. The BMD of the lumbar spine (L2-L4) and bone markers of bone formation and resorption were assessed in children with IH[78]. The patients had elevated osteocalcin and calcitriol blood levels, as well as magnesium and prostaglandin E2 urinary levels. On the other hand, they had decreased urinary ammonium excretion, tubular reabsorption of phosphate and BMD when compared to controls[78]. BMD reduction was present in 30% of the patients and was negatively correlated with age. The authors hypothesized the increased cytokine activity could explain the reduced BMD in these patients[79]. Freundlich et al[31] studied the BMD (lumbar spine and femur) and bone resorption markers (pyridinoline, deoxypyridinoline and telopeptide) of children with IH and of their premenopausal mothers. The authors found BMD reduction in 38% of children and 33% of their mothers. The bone resorption markers were increased in 57% of the mothers with BMD reduction[31]. Garcia Nieto et al[29] described the BMD Z score as < -1 in 30.1% of their pediatric patients with evaluated IH. Bone markers were analyzed to confirm the resorptive mechanism in pediatric patients with HI. In children with normal BMD, a direct correlation was observed with the levels of osteocalcin (bone formation marker) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, a bone resorption marker; however, this relationship disappeared in those with reduced BMD[29]. Subsequently, the authors verified a value of < -1 for BMD Z score in the lumbar spine in 42.5% of a group of girls and in 47.5% of their mothers (lumbar spine and/or femoral neck). Mothers and daughters had hypercalciuria[32]. More sensitive resorption markers such as deoxypyridinoline (DPir) and the C-terminal telopeptide collagen fraction in the urine (CTx) were evaluated. Hypercalciuric children with or without BMD reduction showed significantly higher values of DPir/Creatinine and CTx/Creatinine ratios than controls. In contrast, osteocalcin levels were significantly higher only in patients with normal BMD[32]. These data would confirm that there is an increase in osteoclastic activity in children with IH, and those with normal BMD would have an adequate compensatory osteoblastic response[23].

Penido et al[16] evaluated a group of 88 children with IH at the time of diagnosis and 29 controls. BMD Z-score was significantly reduced at the lumbar spine in 31 (35%) patients. The biochemical markers of bone turnover were also evaluated. There was an increased urinary N-telopeptide excretion in the hypercalciuric subjects, as well as increased serum osteocalcin. The authors suggested that the low bone mass in children with IH might have been due to increased bone turnover[16].

Skalova et al[33] evaluated 15 pediatric hypercalciuric patients, and 40% of them had BMD Z-scores between -1 and -2 standard deviations (SD), and 20% had BMD Z scores below -2 SDs. The values for 24 h urinary calcium and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG - marker of renal tubule impairment) were significantly higher, and lumbar BMD was significantly lower than reference values from a healthy European pediatric population. The authors also demonstrated an inverse correlation between BMD and 24h calciuria[33].

Later, Penido et al[80] evaluating 88 pediatric patients with IH, and half of them had associated hypocitraturia (HC). Those with HC had a higher reduction in BMD in the absence of metabolic acidosis. A significant reduction in blood pH and bicarbonate in the group with HC was observed, although venous blood gases were normal in all patients. The authors suggested that lower blood pH and bicarbonate in hypercalciuric patients with associated HC could indicate that there is an intracellular acidification defect more severe in those patients with HC. This acidic environment would stimulate bone buffering, hypercalciuria and reduced BMD. Although age did not differ between patients with and without HC, those with HC had significantly lower height, weight, bone age and body mass index (BMI), suggesting an effect of HC on growth[80].

In 2009, Garcia Nieto et al[23] evaluated the BMD of 104 children with IH on two occasions. The first bone densitometry was performed at 10.7 ± 2.6 years and the second at 14.4 ± 2.7 years[34]. There were no differences in the calciuria or citraturia values or age at the time of the two bone densitometries. The authors concluded that there is a tendency to improve BMD in children with IH spontaneously, which is associated with increased body mass[34].

Penido et al[30] studied the BMD at the lumbar spine of 80 pediatric patients with IH. BMD Z-scores were evaluated before and after treatment. The patients were followed for a median time of 6.0 years, and they were treated with potassium citrate or potassium citrate and thiazides. BMD Z-score changed significantly from -0.763 ± 0.954 to -0.537 ± 0.898 (P < 0.0001). The authors suggested a beneficial effect of treatment in these patients, with significant improvement in bone mass[30].

Pavlou et al[81] in 2018 investigated 50 children with IH and matched 50 controls in a prospective study. They evaluated biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption and the osteoprotegerin (OPG) and soluble receptor activator of the nuclear factor-kB ligand (sRANKL) system. Following the diagnosis, the patients were requested to follow a 3 mo dietary recommendation. At diagnosis and at 3 mo of follow-up, patients and in controls were studied for bone-related hormones and serum/urine biochemical parameters. The authors concluded that children with IH had biochemical markers compatible with normal bone formation but increased bone resorption. After a 3 mo dietary intervention, the decrease in the serum β-Crosslaps may have reflected a beneficial response[81].

Kusumi et al[82] in 2020 conducted a prospective paired case-control study to assess BMD in adolescents with UL and to evaluate a possible correlation between BMD and urine concentration of lithogenic minerals and/or inflammation markers. It was observed that the BMD Z-score of lumbar spine and total body were not different between groups; however, when patients were separated by gender, there was a significant difference between males vs controls for the BMD Z-score of total body. There was no correlation of the lumbar spine and total body BMD Z-score regarding urinary calcium, oxalate, citrate or magnesium. Higher urine IL-13 significantly correlated with higher total body BMD Z-score (r = 0.677; P = 0.018). The authors concluded that despite the small number of patients, it is a hypothesis-generating study. They demonstrated novel evidence of male-specific low BMD in adolescent stone formers[82].

Recently, Perez-Suarez et al[83] (2021) evaluated 34 hypercalciuric pediatric patients in a longitudinal study conducted over 20 years through three bone densitometry studies. Patients underwent a third densitometry study in adulthood (10.5 ± 2.7 [BMD1], 14.5 ± 2.7 [BMD2] and [BMD3] 28.3 ± 2.9 years of age). The authors observed a gradual decrease in calcium/creatinine and citrate/creatinine ratios and suggested that it would be related to improvement in osteoblastic activity and especially reduction in osteoclastic activity. They concluded that in patients with IH, BMD improves with time. This improvement may be related especially to the female gender, increment of body mass, and reduction in bone resorption. Urine calcium and citrate excretion tend to decrease upon the patients reaching adulthood[83].

At this point, it is known that IH and reduced BMD are closed entities. However, the precise mechanisms of reduction in bone mass loss or failure of normal bone mass gain remain not entirely known.

IMPORTANCE OF HYPERCALCIURIA FOR PEDIATRICIANS

The peak bone mass and its accumulation are achieved by late adolescence, peaking at the end of the second decade of life[84]. This accumulation should occur without interference in order to achieve the peak of optimal bone mass. The bone mass acquired during childhood and adolescence is a major determinant of adult bone health, and its accumulation should occur without interference[85]. This raises the important question of whether adult osteoporosis is initiated during childhood in IH patients[84]. However, interferences in childhood bone mass acquisition would not affect bone mass in late adulthood because there is a homeostatic system that seeks to return to the normal situation after any transient change[85].

Studies have emphasized that a persistent disturbing factor would, therefore, compromise the final bone mass in adulthood[85]. According to these studies, “any continuous and persistent interference may be a determining factor for low BMD with increased risk of osteopenia, osteoporosis and fractures in adulthood”[85].

An important point is how to assess and interpret BMD in children. According to the ISCD official position, DXA is the preferred method. Bone mineral content (BMC) and areal BMD results should be adjusted for absolute height or height age or to pediatric reference data that provide specific Z scores. The terms osteopenia and osteoporosis should not be used in pediatric patients. The correct term for them is “low bone mineral content” or “low bone mineral density” for age, when the Z scores are less or equal minus two[86].

There are few studies showing the association between decreased BMD and fractures in children. Data suggest that children with abnormal BMD are at risk for fractures. However, none of those included a biochemical analysis to assess other potential causes of low BMD[87,88]. In a case-control study, Olney et al[88] showed that BMD values were lower for the case subjects with fractures compared with the control subjects. The authors decided to evaluate these patients because both pediatricians and orthopedists are often unsure whether to consider further evaluation in children with repeat fractures[88].

CONCLUSION

Considering all the aforementioned, it is imperative that pediatricians have the knowledge and ability to diagnose and manage pediatric patients with IH with or without UL. They should advise parents and/or caregivers that children and adolescents must always have a healthy diet with a regular intake of calcium, proteins, calories and sodium, according to RDA; practice daily physical exercises; adequate fluid intake, especially water as well as regular sun exposure. If regular sun exposure is not possible, the serum levels of 25OH Vit. D should be assessed. The control of risk factors and adequate treatment (pharmacological or not) are essential for great bone structure and bone mass throughout life, decreasing the risk of osteopenia, osteoporosis and fractures later in life.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 26, 2021

First decision: July 27, 2021

Article in press: October 31, 2021

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Poddighe D S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Maria Goretti Moreira Guimarães Penido, Pediatric Nephrology Unit, Nephrology Center, Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Hospital, CEP 30150320, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Pediatric Nephrology Unit, Pediatric Department, Clinics Hospital, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, CEP 30130100, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. mariagorettipenido@yahoo.com.br.

Marcelo de Sousa Tavares, Pediatric Nephrology Unit, Nephrology Center, Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Hospital, CEP 30150320, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

References

- 1.Jayaraman UC, Gurusamy A. Review on Uro-Lithiasis Pathophysiology and Aesculapian Discussion. IOSR J Pharma. 2018;8:30–42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penido MG, Tavares Mde S. Pediatric primary urolithiasis: Symptoms, medical management and prevention strategies. World J Nephrol. 2015;4:444–454. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v4.i4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson CM, Wilson DM, O'Fallon WM, Malek RS, Kurland LT. Renal stone epidemiology: a 25-year study in Rochester, Minnesota. Kidney Int. 1979;16:624–631. doi: 10.1038/ki.1979.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasian GE, Ross ME, Song L, Sas DJ, Keren R, Denburg MR, Chu DI, Copelovitch L, Saigal CS, Furth SL. Annual Incidence of Nephrolithiasis among Children and Adults in South Carolina from 1997 to 2012. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:488–496. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07610715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walther PC, Lamm D, Kaplan GW. Pediatric urolithiases: a ten-year review. Pediatrics. 1980;65:1068–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penido MG, Srivastava T, Alon US. Pediatric primary urolithiasis: 12-year experience at a Midwestern Children's Hospital. J Urol. 2013;189:1493–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asselman M, Verhulst A, De Broe ME, Verkoelen CF. Calcium oxalate crystal adherence to hyaluronan-, osteopontin-, and CD44-expressing injured/regenerating tubular epithelial cells in rat kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:3155–3166. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000099380.18995.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieske JC, Toback FG. Regulation of renal epithelial cell endocytosis of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F800–F807. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.5.F800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan AY, Poon P, Chan EL, Fung SL, Swaminathan R. The effect of high sodium intake on bone mineral content in rats fed a normal calcium or a low calcium diet. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3:341–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01637321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ticinesi A, Nouvenne A, Maalouf NM, Borghi L, Meschi T. Salt and nephrolithiasis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:39–45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penido MGMG, Diniz JSS, Guimarães MMM, Cardoso RB, Souto MFO, Penido MG. Urinary excretion of calcium, uric acid and citrate in healthy children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2002;78:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lande MB, Varade W, Erkan E, Niederbracht Y, Schwartz GJ. Role of urinary supersaturation in the evaluation of children with urolithiasis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:491–494. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nazzal L, Blaser MJ. Does the Receipt of Antibiotics for Common Infectious Diseases Predispose to Kidney Stones? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:1590–1592. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bushinsky DA. Genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:479–488. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199907000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bover J, Bosch RJ. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms as a determinant of bone mass and PTH secretion: from facts to controversies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1066–1068. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.5.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penido MG, Lima EM, Marino VS, Tupinambá AL, França A, Souto MF. Bone alterations in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria at the time of diagnosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-1036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albright F, Henneman P, Benedict PH, Forbes AP. Idiopathic hypercalciuria: a preliminary report. Proc R Soc Med. 1953;46:1077–1081. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valverde A. Apropos of infantile urinary lithiasis. Acta Urol Belg. 1962;30:568–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royer P, Mathieu H, Gerbeaux S, Frederich A, Rodriguez-soriano J, Dartois AM, Cuisinier P. Idiopathic hypercalciuria with nanism and renal involvement in children. Ann Pediatr (Paris) 1962;9:147–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stapleton FB. Idiopathic hypercalciuria: association with isolated hematuria and risk for urolithiasis in children. The Southwest Pediatric Nephrology Study Group. Kidney Int. 1990;37:807–811. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penido MG, Diniz JS, Moreira ML, Tupinambá AL, França A, Andrade BH, Souto MF. [Idiopathic hypercalciuria: presentation of 471 cases] J Pediatr (Rio J) 2001;77:101–104. doi: 10.2223/jped.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Worcester EM, Coe FL. New insights into the pathogenesis of idiopathic hypercalciuria. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García Nieto VM, Luis Yanes MI, Tejera Carreño P, Perez Suarez G, Moraleda Mesa T. The idiopathic hypercalciuria reviewed. Metabolic abnormality or disease? Nefrologia (Engl Ed) 2019;39:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan LE, Ing SW. Idiopathic hypercalciuria: Can we prevent stones and protect bones? Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85:47–54. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.85a.16090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köker A, Bayram MT, Soylu A, Özmen D, Kavukcu S, Türkmen MA. Clinical Features of Cases Followed with Idiopathic Hypercalciuria in Childhood, Long-term Follow-up Results and Retrospective Evaluation of Complications. Meandros Med Dent J. 2019;21:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YH, Lee AJ, Chen CH, Chesney RW, Stapleton FB, Roy S 3rd. Urinary mineral excretion among normal Taiwanese children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1994;8:36–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00868256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pak CY, Sakhaee K, Moe OW, Poindexter J, Adams huet B, Pearle MS, Zerwekh JE, Preminger GM, Wills MR, Breslau NA, Bartter FC, Brater DC, Heller HJ, Odvina CV, Wabner CL, Fordtran JS, Oh M, Garg A, Harvey JA, Alpern RJ, Snyder WH, Peters PC. Defining hypercalciuria in nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2011;80:777–782. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quiñones-Vázquez S, Liriano-Ricabal MDR, Santana-Porbén S, Salabarría-González JR. Calcium-creatinine ratio in a morning urine sample for the estimation of hypercalciuria associated with non-glomerular hematuria observed in children and adolescents. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2018;75:41–48. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.M18000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Nieto V, Ferrández C, Monge M, de Sequera M, Rodrigo MD. Bone mineral density in pediatric patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11:578–583. doi: 10.1007/s004670050341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreira Guimarães Penido MG, de Sousa Tavares M, Campos Linhares M, Silva Barbosa AC, Cunha M. Longitudinal study of bone mineral density in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1952-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freundlich M, Alonzo E, Bellorin-Font E, Weisinger JR. Reduced bone mass in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria and in their asymptomatic mothers. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1396–1401. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.8.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García-Nieto V, Navarro JF, Monge M, García-Rodríguez VE. Bone mineral density in girls and their mothers with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;94:c89–c93. doi: 10.1159/000072491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skalova S, Palicka V, Kutilek S. Bone mineral density and urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase activity in paediatric patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:99–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García-Nieto V, Sánchez Almeida E, Monge M, Luis Yanes MI, Hernández González MJ, Ibáñez A. Longitudinal study, bone mineral density in children diagnosed with idiopathic hipercalciuria (IH) Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:2083. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfadda TI, Saleh AM, Houillier P, Geibel JP. Calcium-sensing receptor 20 years later. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:C221–C231. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerstetter JE, O'Brien KO, Insogna KL. Dietary protein, calcium metabolism, and skeletal homeostasis revisited. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:584S–592S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.584S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards NA, Hodgkinson A. Metabolic studies in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Clin Sci. 1965;29:143–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pak CY, Oata M, Lawrence EC, Snyder W. The hypercalciurias. Causes, parathyroid functions, and diagnostic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:387–400. doi: 10.1172/JCI107774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pak CY, Britton F, Peterson R, Ward D, Northcutt C, Breslau NA, McGuire J, Sakhaee K, Bush S, Nicar M, Norman DA, Peters P. Ambulatory evaluation of nephrolithiasis. Classification, clinical presentation and diagnostic criteria. Am J Med. 1980;69:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aladjem M, Barr J, Lahat E, Bistritzer T. Renal and absorptive hypercalciuria: a metabolic disturbance with varying and interchanging modes of expression. Pediatrics. 1996;97:216–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alhava EM, Juuti M, Karjalainen P. Bone mineral density in patients with urolithiasis. A preliminary report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1976;10:154–156. doi: 10.3109/00365597609179678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Insogna KL, Broadus AE, Dreyer BE, Ellison AF, Gertner JM. Elevated production rate of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in patients with absorptive hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:490–495. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-3-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buck AC, Sampson WF, Lote CJ, Blacklock NJ. The influence of renal prostaglandins on glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and calcium excretion in urolithiasis. Br J Urol. 1981;53:485–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1981.tb03244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henríquez-La Roche C, Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Herrera J, Parra G. Increased urinary excretion of prostaglandin E in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Clin Sci (Lond) 1988;75:581–587. doi: 10.1042/cs0750581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prié D, Ravery V, Boccon-Gibod L, Friedlander G. Frequency of renal phosphate leak among patients with calcium nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2001;60:272–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pacifici R, Rothstein M, Rifas L, Lau KH, Baylink DJ, Avioli LV, Hruska K. Increased monocyte interleukin-1 activity and decreased vertebral bone density in patients with fasting idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:138–145. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-1-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghazali A, Fuentès V, Desaint C, Bataille P, Westeel A, Brazier M, Prin L, Fournier A. Low bone mineral density and peripheral blood monocyte activation profile in calcium stone formers with idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:32–38. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.1.3649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misael da Silva AM, dos Reis LM, Pereira RC, Futata E, Branco-Martins CT, Noronha IL, Wajchemberg BL, Jorgetti V. Bone involvement in idiopathic hypercalciuria. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57:183–191. doi: 10.5414/cnp57183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weisinger JR. New insights into the pathogenesis of idiopathic hypercalciuria: the role of bone. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1507–1518. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wark JD, Taft JL, Michelangeli VP, Veroni MC, Larkins RG. Biphasic action of prostaglandin E2 on conversion of 25 hydroxyvitamin D3 to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in chick renal tubules. Prostaglandins. 1984;27:453–463. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(84)90203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beasley D, Dinarello CA, Cannon JG. Interleukin-1 induces natriuresis in conscious rats: role of renal prostaglandins. Kidney Int. 1988;33:1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kreydiyyeh SI, Al-Sadi R. Interleukin-1beta increases urine flow rate and inhibits protein expression of Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase in the rat jejunum and kidney. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:1041–1048. doi: 10.1089/107999002760624279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suáreza GP, Serranob A, Magallanes MV, Sanchoc PA, Yanesc MIL, García Nieto VMG. Estudio longitudinal del manejo renal del agua en pacientes diagnosticados de hipercalciuria idiopática en la infância. Nefrología. 2020;40:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ. Mechanism of hypercalciuria in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Inherited defect in intestinal calcium transport. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1585–1591. doi: 10.1172/JCI113770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li XQ, Tembe V, Horwitz GM, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ. Increased intestinal vitamin D receptor in genetic hypercalciuric rats. A cause of intestinal calcium hyperabsorption. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:661–667. doi: 10.1172/JCI116246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yao J, Kathpalia P, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ. Hyperresponsiveness of vitamin D receptor gene expression to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. A new characteristic of genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2223–2232. doi: 10.1172/JCI1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krieger NS, Stathopoulos VM, Bushinsky DA. Increased sensitivity to 1,25(OH)2D3 in bone from genetic hypercalciuric rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C130–C135. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsuruoka S, Bushinsky DA, Schwartz GJ. Defective renal calcium reabsorption in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1540–1547. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao JJ, Bai S, Karnauskas AJ, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ. Regulation of renal calcium receptor gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1300–1308. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004110991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Worcester EM, Coe FL, Evan AP, Bergsland KJ, Parks JH, Willis LR, Clark DL, Gillen DL. Evidence for increased postprandial distal nephron calcium delivery in hypercalciuric stone-forming patients. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1286–F1294. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90404.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Favus MJ, Karnauskas AJ, Parks JH, Coe FL. Peripheral blood monocyte vitamin D receptor levels are elevated in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4937–4943. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moreira Guimarães Penido MG, de Sousa Tavares M, Saggie Alon U. Role of FGF23 in Pediatric Hypercalciuria. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:3781525. doi: 10.1155/2017/3781525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borghi L, Meschi T, Maggiore U, Prati B. Dietary therapy in idiopathic nephrolithiasis. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:301–312. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.jul.301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arcidiacono T, Mingione A, Macrina L, Pivari F, Soldati L, Vezzoli G. Idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: a review of pathogenic mechanisms in the light of genetic studies. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40:499–506. doi: 10.1159/000369833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maierhofer WJ, Gray RW, Cheung HS, Lemann J Jr. Bone resorption stimulated by elevated serum 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D concentrations in healthy men. Kidney Int. 1983;24:555–560. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bataille P, Achard JM, Fournier A, Boudailliez B, Westeel PF, el Esper N, Bergot C, Jans I, Lalau JD, Petit J. Diet, vitamin D and vertebral mineral density in hypercalciuric calcium stone formers. Kidney Int. 1991;39:1193–1205. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thorleifsson G, Holm H, Edvardsson V, Walters GB, Styrkarsdottir U, Gudbjartsson DF, Sulem P, Halldorsson BV, de Vegt F, d'Ancona FC, den Heijer M, Franzson L, Christiansen C, Alexandersen P, Rafnar T, Kristjansson K, Sigurdsson G, Kiemeney LA, Bodvarsson M, Indridason OS, Palsson R, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Sequence variants in the CLDN14 gene associate with kidney stones and bone mineral density. Nat Genet. 2009;41:926–930. doi: 10.1038/ng.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolf MT, Zalewski I, Martin FC, Ruf R, Müller D, Hennies HC, Schwarz S, Panther F, Attanasio M, Acosta HG, Imm A, Lucke B, Utsch B, Otto E, Nurnberg P, Nieto VG, Hildebrandt F. Mapping a new suggestive gene locus for autosomal dominant nephrolithiasis to chromosome 9q33.2-q34.2 by total genome search for linkage. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:909–914. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Milart J, Lewicka A, Jobs K, Wawrzyniak A, Majder-Łopatka M, Kalicki B. E_ect of Vitamin D Treatment on Dynamics of Stones Formation in the Urinary Tract and Bone Density in Children with Idiopathic Hypercalciuria. Nutrients. 2020;12:2521–2533. doi: 10.3390/nu12092521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alon US, Berenbom A. Idiopathic hypercalciuria of childhood: 4- to 11-year outcome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:1011–1015. doi: 10.1007/s004670050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Srivastava T, Schwaderer A. Diagnosis and management of hypercalciuria in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:214–219. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283223db7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roodman GD, Ibbotson KJ, MacDonald BR, Kuehl TJ, Mundy GR. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 causes formation of multinucleated cells with several osteoclast characteristics in cultures of primate marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:8213–8217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Malluche HH, Tschoepe W, Ritz E, Meyer-Sabellek W, Massry SG. Abnormal bone histology in idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50:654–658. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-4-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gomes SA, dos Reis LM, Noronha IL, Jorgetti V, Heilberg IP. RANKL is a mediator of bone resorption in idiopathic hypercalciuria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1446–1452. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00240108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taguchi K, Hamamoto S, Okada A, Tanaka Y, Sugino T, Unno R, Kato T, Ando R, Tozawa K, Yasui T. Low bone mineral density is a potential risk factor for symptom onset and related with hypocitraturia in urolithiasis patients: a single-center retrospective cohort study. BMC Urol. 2020;20:174–84. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00749-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stapleton FB, McKay CP, Noe HN. Urolithiasis in children: the role of hypercalciuria. Pediatr Ann. 1987;16:980–981, 984. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19871201-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stapleton FB, Jones DP, Miller LA. Evaluation of bone metabolism in children with hypercalciuria. Semin Nephrol. 1989;9:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perrone HC, Lewin S, Langman CB, Toporovski J, Marone M, Schor N. Bone effects of the treatment of children with absorptive hypercalciuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 1992;6:C115. [Google Scholar]

- 79.García-Nieto V, Navarro JF, Ferrández C. Bone loss in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria. Nephron. 1998;78:341–342. doi: 10.1159/000044950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Penido MG, Lima EM, Souto MF, Marino VS, Tupinambá AL, França A. Hypocitraturia: a risk factor for reduced bone mineral density in idiopathic hypercalciuria? Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:74–78. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pavlou M, Giapros V, Challa A, Chaliasos N, Siomo E. Does idiopathic hypercalciuria affect bone metabolism during childhood? Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33:2321–2328. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4027-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kusumi K, Schwaderer AL, Clark C, Budge K, Hussein N, Raina R, Denburg M, Safadi F. Bone mineral density in adolescent urinary stone formers: is sex important? Urolithiasis. 2020;48:329–335. doi: 10.1007/s00240-020-01183-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perez-Suarez G, Yanes MIL, de Basoa MCMF, Almeida ES, García Nieto VM. Evolution of bone mineral density in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria: a 20-year longitudinal study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36:661–667. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baroncelli GI, Bertelloni S, Sodini F, Saggese G. Osteoporosis in children and adolescents: etiology and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2005;7:295–323. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gafni RI, Baron J. Childhood bone mass acquisition and peak bone mass may not be important determinants of bone mass in late adulthood. Pediatrics. 2007;119 Suppl 2:S131–S136. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2023D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gordon CM, Leonard MB, Zemel BS International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2013 Pediatric Position Development Conference: executive summary and reflections. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clark EM, Tobias JH, Ness AR. Association between bone density and fractures in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e291–e297. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olney RC, Mazur JM, Pike LM, Froyen MK, Ramirez-Garnica G, Loveless EA, Mandel DM, Hahn GA, Neal KM, Cummings RJ. Healthy children with frequent fractures: how much evaluation is needed? Pediatrics. 2008;121:890–897. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]