Abstract

Esthetic demands for correction of irregularities of dentition are becoming a prime concern even in patients above the age of 40 years. Severe periodontitis, being insidious, if present simultaneously, complicates the situation. Periodontally compromised adult patients requiring the treatment for malaligned teeth are encountered very frequently in daily practice, and the correction of these requires a combined perio-ortho interdisciplinary approach. The present case report deals with a 5-year follow-up of a case whose prime concern was rotated anterior teeth in the maxillary arch. However, along with this, severe periodontitis was also present. Open flap debridement along with osseous grafting was done wherever required, followed by fixed adjunctive orthodontic treatment. After the completion of orthodontic treatment, a fixed retainer in the form of splinting was given and the entire treatment met the esthetic along with functional demands of the patient. Early 6 months followed by yearly follow-ups reflected clinical and radiographic improvements in the dentition.

Keywords: Adjunctive orthodontics, esthetic, open flap debridement, periodontitis, perio-ortho

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis is considered to be the disease of adulthood, and is characterized by various problems among which one is the malalignment/pathological migration of the teeth. This, when occurs in the esthetic region or in areas interfering with the maintenance and occlusion, demands correction. Moreover, in the modern era when everyone is more concerned with prolonged retention of the natural dentition and esthetics both, patients demand for it. This increases the need for management of periodontal defects and malalignment, and ultimately adjunctive orthodontics in the elderly.[1] Hence, such type of cases needs multidisciplinary management and co-operation among the periodontist, orthodontist, and endodontist.

The present case report deals with the multidisciplinary management in a 50-year-old patient who was having severe periodontitis and rotation of the maxillary incisors. The prime concern of the patient was mobility of teeth and esthetics. Hence, proper co-ordination between the three specialties and regular periodontal monitoring helped in managing the periodontal and orthodontic problems for the last 5 years. The patient is kept under regular follow-up.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-oldpatient was initially attended by a general dentist who provided him primary treatment as scaling and root planing and then referred him to our clinic. He had a chief complaint of pain, mobility in teeth, occasional bleeding from gums, and crowding of anterior teeth. Detailed interrogation revealed that bleeding from gums was mostly while brushing for more than a year, sensitivity to hot and cold since the last 6–7 months, progressive mobility and overlapping of upper front teeth, and halitosis [Figure 1]. Clinical examination revealed the presence of probing depths ranging from 2 to 5 mm with multiple Grade 1 mobile teeth and rotation of anterior teeth with crowding. In relation to tooth #14, deep pocket ranged from 9 to 11 mm at its different aspects. This tooth was nonvital on electronic pulp testing with Grade II mobility. Radiographically, generalized bone loss could be appreciated and angular defect along with root resorption could be appreciated in tooth #14 [Figure 2]. Keeping the abovementioned clinical and radiographic features in mind, and an urge to improve the esthetics by the patient, an endo-perio-ortho multidisciplinary treatment approach was planned.

Figure 1.

Preoperative

Figure 2.

Preoperative radiograph

Treatment provided

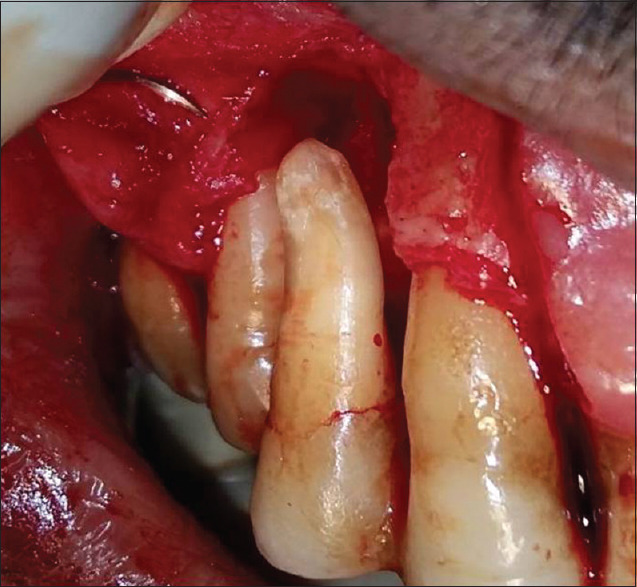

Treatment was started with Phase I therapy comprising oral hygiene instructions, scaling, root planing, occlusal corrections, and occlusal splinting of #14 with #15. After this, the patient was kept on periodontal evaluation, and simultaneously, a randomized control trial of #14 was also done. Once the patient started following the oral hygiene instructions properly, surgical management of tooth #14 was planned. Full-thickness flap was raised and complete degranulation was done [Figure 3] followed by placement of the bone graft in the visualized defect area [Figure 4]. The flap was then sutured using Mersilk 4-0 suture (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Pvt. Ltd.). He was then discharged with postoperative instructions, antibiotic therapy for 5 days (amoxicillin 500 mg thrice a day), analgesic (ibuprofen 400 mg thrice, if there was pain), and chlorhexidine mouthwash (twice a day). The patient was recalled after 10 days for suture removal and revaluation. He was kept on maintenance phase, every 15 days, for the next 3 months. The nonsurgical periodontal therapy in other areas resulted in clinical improvement and reduction in probing depth in the range of 2–3 mm.

Figure 3.

Post debridement of granulation tissue

Figure 4.

Bone graft placed in the defect site

Three months postoperatively, orthodontic treatment was started using metallic brackets (MBT.022” slot) and very mild force [Figure 5]. The orthodontic treatment was started escaping the bracket on tooth #14. The de-rotation of the right maxillary central incisor was brought about in approximately 5 months. However, in order to retain the tooth in its place, the brackets were kept on for another 6 months. Following the orthodontic treatment, permanent retention in the form of splinting was done. The patient was kept on regular 3-month follow-up [Figure 6].

Figure 5.

Post bracket placement

Figure 6.

Post treatment completion

The present case is a report of 5-year follow-up [Figures 7-9] in which relapse of any kind is not seen, clinically as well as radiographically. The patient is happy with healthy dentition, both esthetically and functionally, though at reduced periodontal support.

Figure 7.

Five years post treatment

Figure 9.

Five-year postoperative radiograph

Figure 8.

Post treatment radiograph

DISCUSSION

Adult orthodontics is usually considered as orthodontics beyond 35 years of age. This happens in a group of people who could not get orthodontic treatment due to ignorant parents or have now become financially independent to afford it. Older adults, usually above 50 years of age having multiple dental problems, may require adjunctive orthodontics as a part of complete treatment. Thus, with the increase in geriatric patients and their esthetic demands, adult orthodontics is becoming the need of hour. According to Proffit et al., “Adjunctive orthodontic treatment for adults is, by definition, tooth movement carried out to facilitate other dental procedures necessary to control disease, restore function, and/or enhance appearance.”[1] In the present case, it was needed for control of periodontal disease in the adult of 50 years of age who exhibited generalized loss of attachment, with 9–11 mm of pockets in tooth #14 at different sites, and rotation of anterior teeth. The patient's prime concern was esthetics in respect to maxillary anteriors and mobility in some teeth. Thus, it was an obvious multidisciplinary case requiring approaches from various dental disciplines. Hence, with the patient's consent, a combined perio-endo-ortho multidisciplinary approach was planned. Three months following the completion of periodontal treatment, orthodontic treatment was started with the lightest 0.014” nickel–titanium wire, skipping the bracket on #14 with the intention not to disturb the healing osseous lesion.

During orthodontic tooth movement, the tooth moves with its socket and the movement is possible without jeopardizing periodontal support in the presence of adequate plaque control.[2] It has been demonstrated that the compression in the periodontal ligament for about 4 h causes changes in the chemical environment producing different patterns of cellular activities.[3] Focal adhesion kinase appears to be the mechanoreceptor in periodontal ligament cells, and their compression leads to release of prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-1 beta.[4] Increased concentration of the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement suggests that periodontal ligament cells under stress may induce formation of osteoclast cells through upregulation of RANKL.[5] Studies of cellular kinetics indicate that osteoclasts arrive in two waves: in the first wave, they may be derived from a local cell population, while in the larger second wave, they are brought in from distant areas via blood flow and remove bone in the frontal resorption and tooth movement begins.[6]

Both the amount of force delivered to a tooth and the area of periodontal ligament over which that force is distributed are important in determining the biological effect. The periodontal response is determined not by force alone, but by force per unit area. In tipping movement, only a partial area of periodontal ligament is under pressure. Hence, forces must be kept quite low not exceeding approximately 50 g.

The aim of adjunctive orthodontics is to provide periodontal health by eliminating plaque retentive areas and improve the contour of the periodontium to a self-maintainable level, as far as possible. Through continuous periodontal monitoring and application of advanced periodontal treatment, orthodontic management is possible even in adult patients. This favorable physiologic and realistic occlusion has little to do with Angle's idealistic occlusion, as is observed in this 54-year-old patient during 5-year follow-up. The treatment is possible because of minutely, and carefully taking care of the periodontal status at every step.

To conclude, a better understanding of the tissue behavior and broader treatment modalities help in discovering cures for situations which were otherwise deemed to be impossible before. With the advancement in the interdisciplinary treatment approaches, esthetics can be improved through adult orthodontics even in patients with reduced periodontal support, under strict periodontal invigilation and monitoring.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM. Special Considerations in treatment for adults. In: Proffit WR, editor. Text Book of Contemporary Orthodontics. 5th ed. New Delhi: Reed Elsevier India Private Limited; 2013. pp. 624–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melsen B, Agerbaek N, Markenstam G. Intrusion of incisors in adult patients with marginal bone loss. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:232–41. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khouw FE, Goldhaber P. Changes in vasculature of the periodontium associated with tooth movement in the rhesus monkey and dog. Arch Oral Biol. 1970;15:1125–32. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(70)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang YG, Nam JN, Kim KH, Lee KS. FAK pathway regulates PGE2 production in compressed periodontal ligament cells. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1444–9. doi: 10.1177/0022034510378521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguchi M. RANK/RANKL/OPG during orthodontic tooth movement. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2009;12:113–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2009.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graber LW, Vanarsdall RL, Vig KW. Orthodontics: Current Principles and Techniques. 5th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]