Abstract

Background

Although participation of patients is essential for completing the training of medical residents, little is known about the relationships among patients’ level of knowledge about the role and responsibilities of medical residents, their confidence in residents’ abilities, and their acceptance toward receiving care from residents. The study sought to clarify if and how these three patient-resident relationship components are interrelated.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study using a self-administered questionnaire distributed in 2016 to a convenience sample of adult patients (≥ 18 years old) visiting a family medicine teaching clinic. Proportions and chi-square statistics were used to describe and compare groups, respectively.

Results

Of the 471 patients who answered the questionnaire, only 28% were found to be knowledgeable about the role of family medicine residents. Between 54% and 83% of patients reported being highly confident in the ability of residents to perform five routine tasks. Of the patients surveyed, 69% agreed to see a resident during their next appointments. Patients with a high level of confidence in residents’ abilities were more likely to agree to see a resident during future appointments (p <0.0001). There was no significant association between level of knowledge and either confidence or acceptance.

Conclusions

Although the majority of patients had poor knowledge about the role of residents, this was not related to their acceptance of being cared for by residents. A higher level of confidence in residents’ ability to perform certain tasks was associated with greater acceptance toward seeing a resident during future appointments.

Abstract

Contexte

Tandis que la participation des patients est essentielle pour la formation de résidents en médecine, on en sait peu sur le rapport entre le niveau de connaissance qu'ont les patients du rôle et des responsabilités des résidents, leur confiance dans les compétences des résidents et leur acceptation de recevoir des soins de leur part. La présente étude visait à clarifier si et de quelle manière ces trois composantes du rapport patient-résident sont interreliées.

Méthodes

Il s'agit d'une étude transversale réalisée au moyen d'un questionnaire auto-administré distribué en 2016 à un échantillon de convenance de patients adultes (≥ 18 ans) ayant fréquenté une clinique universitaire de médecine familiale. La proportion et le test du khi carré ont été utilisés respectivement pour décrire et pour comparer les groupes.

Résultats

Parmi les 471 patients qui ont répondu au questionnaire, à peine 28 % connaissaient bien le rôle des résidents en médecine familiale. Entre 54 % et 83 % des patients ont déclaré avoir une grande confiance dans la capacité des résidents à effectuer cinq tâches de routine. Parmi les patients interrogés, 69 % ont accepté de voir un résident lors de leurs prochains rendez-vous. Les patients ayant un niveau de confiance élevé dans les capacités des résidents étaient plus susceptibles d'accepter de voir un résident lors de leurs prochains rendez-vous (p <0,0001). Il n'y avait pas d'association significative entre le niveau de connaissance des patients et leur confiance dans les résidents ou leur acceptation d'être traités par ces derniers.

Conclusions

Bien que la majorité des patients aient une mauvaise connaissance du rôle des résidents, celle-ci n'a pas d'incidence sur leur acceptation d'être soignés par de résidents. Un niveau de confiance plus élevé dans la capacité des résidents à effectuer certaines tâches était associé à une plus grande acceptation de voir un résident à l'avenir.

Introduction

Graduation from medical school is but one step on the path to becoming a family physician. Before establishing their own independent practice, medical graduates are required to undertake a residency in family medicine. Residents train and practice for at least two years in a hands-on environment while under the supervision of experienced physicians. The goal of this mentor-trainee relationship is to allow residents to gain experiential knowledge and enable them to develop the clinical, technical and interpersonal skills needed to become proficient and empathetic primary care physicians.1 Patients are an integral and essential component of residency programs. The more patients are willing to participate in the training of family physicians, the more likely residents will learn about the myriad of health contexts, conditions and challenges that one encounters in a primary care setting.2 In this way, high levels of patient engagement provide residents with a faithful representation of day-to-day life in a family medicine practice and prepares them to attend to their future patients’ needs in an effective and professional manner.3 Patient attitudes, perceptions and experiences, therefore, have vital implications for the success of residency programs in family medicine. As a result, a great deal of care must be taken to create an atmosphere of transparency and trust between patients, residents and the physicians who supervise residents.

With the shift towards adoption of patient-centered care models, recent years have seen a rise in research on the relationships between patients and physicians-in-training. This ever-expanding literature has focused on several key themes. Studies have shown that patients view participation in medical education as a worthwhile and rewarding experience. Patients rapidly trust residents involved in their care,4 have a positive attitude toward residents,2,5 agree to contribute to the training of medical students and residents,6 see themselves as playing an important role in the training of the next generation of medical practitioners,7,8 identify advantages in receiving care from physicians-in-training in lieu of their regular physician,2,5,9 and report positive experiences and overall satisfaction with residents’ involvement as caregivers.2,4,5,10

However, when it comes to understanding who physicians-in-training are and what they have been trained to do, the level of knowledge of patients is said to be low.6,11,12,13 For example, patients sometimes confuse residents with interns13 and many patients are unaware that residents have already completed a medical degree.14 This lack of understanding about the nature and status of physicians-in-training can affect trust, negatively impact patient satisfaction with the level of care received, and raise questions as to a patient’s ability to provide informed consent to receive medical care or treatments.6,11 Involvement of trainees in patient care can also lead to confusion among patients as to who is their principal caregiver,15 and patients can become frustrated when multiple physicians, at different levels of training, are involved in their care.6,13 On the whole, the various misconceptions and misunderstandings that patients have about the nature of the medical education system can pose significant barriers to patient involvement in medical education. At the same time, patients consider the level of training of their physician as important information that should be shared openly with them from the very outset;6,11,12,16 in some studies, the percentage of patients surveyed who shared this view reached as high as 90 and 95 per cent.14,17

In an effort to promote greater patient involvement in medical education, studies have sought to identify variables or factors that can influence a patient’s acceptance toward receiving care from a medical trainee. These include, among others, a patient’s own level of education,14 whether a patient has had previous clinical encounters with a resident,4 the overall quality of these previous encounters,18 as well as the gender of the physician-in-training.2 However, few studies have explored whether a link exists between a patient’s level of knowledge about the educational level of residents and the patient’s acceptance towards being treated by residents in family medicine. One early study was carried out in an emergency department and suggested that patient knowledge of the medical system did not lead to greater acceptance towards receiving care from physicians-in-training.6 Since then, other studies have examined the issue in other practice settings. In a study carried out in ophthalmology teaching clinics, patients who were less accepting of receiving care from medical learners were those who received lower scores on questions assessing their knowledge of medical education.17 Similarly, a study exploring patient perceptions of surgical residents showed that 30 per cent of patients surveyed failed to accurately define the resident’s status as full-fledged physicians, a percentage almost equal to those patients who reported not wanting any participation from surgical residents in their operation (32 per cent).19

Measuring patient confidence in medical learners’ skills and abilities has also been one of the foci of recent surveys on patient attitudes, experiences and perceptions regarding participation in medical training. Yet, the issue of patient confidence in residents’ skills and expertise has rarely been assessed in relation to patient knowledge about medical education. A patient survey distributed in an outpatient academic orthopedic surgery clinic showed that patients displaying lower levels of confidence in medical learners’ training and expertise were those who obtained fewer correct answers on questions about the distinctions between medical interns and residents.14 However, to our knowledge, no study has simultaneously assessed potential associations among patient’s knowledge about the role of residents, their level of confidence in a resident’s ability to perform these roles, and their acceptance toward being cared for by a resident.

Moreover, family medicine teaching clinics are underrepresented in previous studies exploring issues surrounding patient knowledge, confidence and acceptance in relation to medical residents. Of the few studies including such settings, one study comparing urban and rural family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology clinics reported that patients’ knowledge about the various levels of medical education was positively associated with their level of satisfaction in being cared for by medical trainees.20 In another study, patients who were seen by a residents when attending the outpatient offices of university-affiliated family physicians demonstrated a better understanding of who residents were than patients who had not been seen by a resident.5

The current study therefore aims to fill a knowledge gap by investigating the potential interrelationship between patients’ knowledge about the role of residents, their confidence in residents’ ability to perform these roles, and their acceptance toward being cared for by residents within a family medicine teaching clinic.

Methods

Setting, design, and selection of participants

This study is a cross-sectional survey with a convenience sample of adult patients (≥ 18 years old) who attend the Dieppe Family Medicine Teaching Unit (DFMTU) in the Greater Moncton area, in New Brunswick, Canada. The DFMTU is part of a network of 11 family medicine units affiliated with the Université de Sherbrooke (Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada). The DFMTU serves 16,000 patients and is staffed by 16 family physicians, two nurses, 35 family medicine residents and 24 medical students. The selection of a family medicine teaching clinic as the practice setting for this study was all the more important since patients visiting a clinic affiliated to a university are said to have more interactions with physicians-in-training and are more likely to know the difference between medical students and residents when compared to patients attending a non-academic clinic.20

The study was conducted during a one-month period, from 15 January 2016 to 15 February 2016 and included both first-time and returning patients. No record was kept as to the number of excluded questionnaires, nor as to the reasons for their exclusion. Consent to participate in the study was implied by the patient’s submission of a completed questionnaire. The Research Ethics Board of the Vitalité Health Network approved this study.

Study questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire, adapted from previous studies5,5 and comprising of 15 questions, was distributed by the clinic’s receptionists to eligible patients when the latter registered to see their family medicine physician. The receptionists were trained to only distribute the questionnaire to patients 18 years or older and to inform them that they were free to answer or not. Receptionists also verified that patients had not already participated as they could only participate once. The first page of the questionnaire explained the study objectives, reiterated eligibility criteria, and confirmed informed consent. The patients typically took 5-10 minutes to fill out the survey in the clinic’s waiting room and returned the completed copy to the receptionist before their appointment began. The patients could receive the questionnaire in their preferred language of communication (French or English). The questionnaire was originally developed in English and then translated into French by a bilingual team member before being translated back in English by another bilingual team member. The original and back-translated versions of the questionnaire were essentially identical providing evidence of invariability across the English and French questionnaires. Before launching data collection, the questionnaire was pilot-tested among six patients to ensure that they were able to clearly understand each question as written.

One question focused on the confidence component of the patient-resident relationship. The question listed five tasks (identifying a health problem, conducting a physical exam, writing a prescription, performing a procedure and providing advice) and asked respondents to indicate their level of confidence in the ability of medical residents to successfully perform each task (“excellent,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” or “I don’t know”), with answers “good” and “excellent” interpreted as signifying a high level of confidence on the part of the patient.

The patient’s level of acceptance toward receiving care from a resident was captured by the respondent’s answer to the question: “Would you accept to see a resident during your next appointments?” Options to choose from were “yes,” “no,” or “I am not sure.”

Two survey questions sought to determine whether a patient was knowledgeable about the residents’ level of training and level of responsibility (Table 1). Respondents who selected the correct answers for both questions were deemed to be knowledgeable about the role and responsibilities of residents training at the DFMTU.

Table 1.

Survey questions assessing patients’ knowledge about the role and responsibilities of residents at the Dieppe Family Medicine Teaching Unit

| At the best of your knowledge, residents at the Dieppe Family Medicine Teaching Unit are… (please select one answer from the options listed below) | |

| a) Medical doctors | |

| b) Family doctors | |

| c) Doctors doing their training in family medicine | |

| d) Doctors in general training before specializing | |

| e) I don’t know | |

| At the best of your knowledge, residents at the Dieppe Family Medicine Teaching Unit... (please select one answer from the options listed below) | |

| a) Observe my doctor during my appointment | |

| b) Do the same work as my doctor, but have to review with him or her afterwards | |

| c) Do the same work as my doctor | |

| d) I don’t know | |

Bold font = correct answer

The survey also collected sociodemographic data from each respondent with questions pertaining to gender, age, highest level of education attained and overall quality of health as assessed by the patients themselves. In addition, the questionnaire addressed various aspects of the patient-physician relationship; for example, patients were asked to rate the overall quality of this relationship and to specify how long they had been under their physician’s care.

Data analysis

Since less than 2.5% of participants provided questionnaires with missing data, we proceeded with the maximum number of participants available for each analysis without replacing any missing values. Descriptive data drawn from the patient surveys are presented as frequencies and percentages. Associations between knowledge and confidence, knowledge and acceptance, and confidence and acceptance were assessed with chi-square statistics. A predefined sample size of 375 was calculated to be representative of the 16,000 patients who have one of the DFMTU’s family physicians as their primary care provider, with a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. This sample size would provide over 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.5 or greater when the proportion for one group ≥ 25% and alpha is set at 0.05. Data were managed and analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We were unable to determine the response rate as the number of questionnaires distributed to patients was not recorded.

Results

While 7% (n = 31) of respondents could not state with certainty whether they had seen a resident during past appointments, the vast majority of the participating patients (395/471) reported having previously seen a resident at the DFMTU (Table 2). Despite this contact, only 28% (n = 132) of respondents were deemed to be knowledgeable about the role and responsibilities of residents. A minority of respondents (13%, n = 59) reported not being open to seeing a resident in the future, and a slightly higher number (18%, n = 84) remained uncertain as to whether they would agree to see a resident during future appointments. Neither knowledge about the role and responsibilities of residents, nor acceptance towards receiving care from residents were related to patients’ gender, age, education, self-perceived health, number of years with physician, or quality of relationship with physician (all p > 0.1).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and patient-physician relationship characteristics of participants in the DFMTU study

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n = 466) | |

| Male | 163 (35.0) |

| Female | 301 (64.6) |

| Transgender | 2 (0.40) |

| Age (y) (n = 466) | |

| 18-29 | 48 (10.3) |

| 30-39 | 79 (17.0) |

| 40-49 | 74 (15.9) |

| 50-59 | 108 (23.2) |

| 60-69 | 84 (18.0) |

| 70-79 | 53 (11.4) |

| 80+ | 20 (4.30) |

| Education levels (n = 466) | |

| No education | 3 (0.64) |

| Primary School | 24 (5.15) |

| High School | 134 (29.0) |

| College | 141 (30.3) |

| University | 164 (35.2) |

| Current health rating (n = 470) | |

| Excellent | 86 (18.3) |

| Good | 279 (59.4) |

| Fair | 88 (18.7) |

| Poor | 17 (3.62) |

| Has already seen a resident (n=466) | |

| Yes | 395 (84.8) |

| No | 40 (8.6) |

| Uncertain | 31 (6.7) |

| Number of years followed by the physician (n = 462) | |

| 0-2 | 35 (7.6) |

| 3-5 | 43 (9.3) |

| 6-10 | 82 (17.8) |

| 11-15 | 53 (11.5) |

| 16-20 | 54 (11.7) |

| 20 + | 195 (42.2) |

| Patient-physician relationship rating (n = 468) | |

| Excellent | 316 (67.5) |

| Good | 126 (26.9) |

| Fair | 23 (4.91) |

| Poor | 3 (0.6) |

| Frequency of visits with the physician (n = 460) | |

| Weekly | 3 (0.65) |

| Monthly | 38 (8.26) |

| Every 3 months | 106 (23.0) |

| Every 6 months | 155 (33.7) |

| Every year | 122 (26.5) |

| Less than every year | 36 (7.83) |

Knowledge and confidence

To examine the potential association between knowledge and confidence, respondents were divided into two groups based on whether they were categorized as knowledgeable about the role of residents or not. When comparing these two groups, no significant differences were found in the proportion of patients reporting a high level of confidence in residents’ abilities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Proportion of patients at the DFMTU reporting a high level of confidence in the ability of residents to perform specific tasks

| Proportion reporting a high level of confidence (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients knowledgeable about the roles of residents | Patients not knowledgeable about the roles of residents | p-value (chi-square) | |

| Identifying the health problem | 74 | 69 | 0.4 |

| Conducting a physical examination | 85 | 82 | 0.5 |

| Writing a prescription | 81 | 79 | 0.3 |

| Performing certain procedures | 60 | 51 | 0.3 |

| Offering advice | 75 | 72 | 0.5 |

Knowledge and acceptance

Similarly, on the issue of acceptance toward seeing a resident during future appointments, there was no difference between the two groups of patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Proportion of patients at the DFMTU accepting to see a resident during future appointments

| Proportion accepting to see a resident during future appointments (%) | |

|---|---|

| Patients knowledgeable about the role of residents | 88 |

| Patients not knowledgeable about the roles of residents | 83 |

| p-Value (chi-square) | 0.4 |

Confidence and acceptance

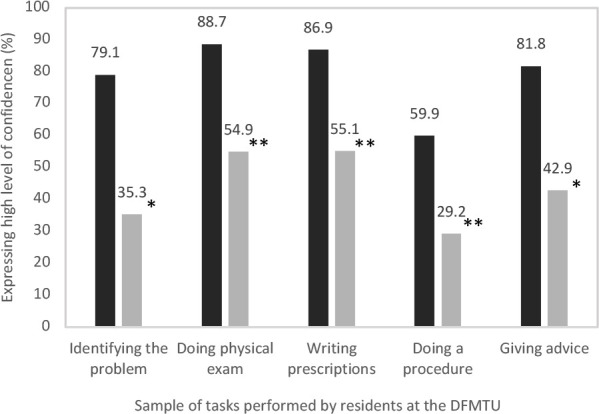

A high level of confidence in residents’ ability to perform different tasks was more common among patients who would accept to see a resident in the future than among patients who would not (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients at the DMFTU who are confident in the ability of residents to perform certain tasks, according to whether or not they accept to see a resident during future appointments. Legend: Columns in black represent patients who accept to see a resident during future appointments, while columns in grey represent patients who refuse to see a resident during their next appointments. **P< 0.0001 * P<0.001

Discussion

This study assessed potential interrelationships between patients’ knowledge about the role of residents, their confidence in residents’ ability to perform these roles, and their acceptance toward being cared for by residents within a family medicine teaching clinic. Since patients attending the DFMTU regularly interact with residents, we initially expected that a large proportion of survey respondents would be knowledgeable about the role and responsibilities of family medicine residents. However, less than a third of patients surveyed were knowledgeable as to who residents are and what level of responsibilities they have. These findings are similar to those of previous studies carried out in other practice settings that have demonstrated a low level of patient knowledge about the role and responsibilities of physicians-in-training.6,11,21,22 One study has shown that residents introduce themselves as doctors over 80% of the time and as residents only 7% of the time [16], which points to communication issues potentially being responsible for this situation. In the case of the DFMTU, however, it does not appear that the lack of knowledge about the role and responsibilities of residents is due to inadequate introductions on the part of residents since a large majority of respondents reported having previously seen a resident. Moreover, only 7% of patients surveyed were unsure whether they had already seen a resident during previous appointments.

Nonetheless, clear communication of the medical practitioner’s title, in and of itself, may not provide the patient with enough information to enable them to fully understand their health care provider’s status within the medical education hierarchy or their specific level of responsibility, training and ability.14 In one study, physicians-in-training at a university based-teaching hospital wore a colored badge alongside their name tag indicating their level of medical education and training; patients noticed the badge and considered the initiative useful, but were still unfamiliar with the significant differences that exist between such titles as “medical student” and “resident”.12 Such findings underscore the need to adopt initiatives that provide patients with a clear, succinct and accessible overview of the roles and responsibilities of the different levels of medical learners. Kravetz et al. have shown that patients do not always understand how the different components of the medical education hierarchy fit and work together, so it is important that patients view residents, in their role as physicians-in-training, as part of a “progressive continuum of knowledge, responsibility, and authority”.13 Care should also be taken to include the perspectives and insights of patients when developing such educational initiatives, thus guaranteeing their effectiveness and usefulness for the target audience.23

Patients visiting university clinics are said to be more comfortable having residents involved in their care than patients attending non-academic clinics.20 Moreover, patients who have not encountered or worked with medical students much are said to be more likely to refuse the participation of residents in their care.2,21 In our study, patients accepted seeing a resident in proportions similar to those of other studies carried out in academic settings [5,16]. Another indicator of patient acceptance toward these physicians-in-training is the large majority of patients surveyed who had already seen a resident. Yet, patients surveyed for this study also reported a lack of confidence in the ability of residents to perform certain procedures. These findings echo those of previous studies that have shown patients to be less comfortable having residents involved in their care when invasive procedures are required,4,10 when suffering from moderate to major injuries or complaints,24 or in emergency scenarios.2 Nevertheless, patient-oriented educational initiatives promoting a greater understanding of residents’ education, roles and responsibilities can improve acceptance of and confidence in the skills and abilities of residents, as in the case of surgical procedures.25

Consistent with findings from another study,6 our results suggest that patients’ level of knowledge regarding the roles and responsibilities of family medicine residents may not directly be associated with their likelihood to accept to be seen by a resident. Our study also found that no clear link exists between a patient’s level of knowledge regarding the roles and responsibilities of family medicine residents and their confidence in the ability of residents to be their caregiver. A previous study had shown that the higher a patient’s level of knowledge about the roles and responsibilities of residents, the higher the confidence that a patient will display in a resident’s ability to be their health care provider.14

However, our study supports the hypothesis that patients who are confident in the abilities of residents will be more likely to accept them as members of their healthcare team. University departments and teaching clinics could therefore implement and test strategies to promote patient confidence in residents’ skills and abilities. Future research could explore whether information displayed on screens in waiting rooms or the provision of brief explanations from residents contribute to improving knowledge, confidence and acceptance by patients. Physicians supervising residents could also play a role in helping to promote greater patient confidence in residents’ abilities and skillsets. Similar to another study, patients surveyed at the DMFTU reported having long-standing relationships with their regular physician and 94% rated the relationship that they had with their regular physician as either “good” or “excellent”.5 These data suggest that supervising physicians may be well positioned to help patients gain confidence in the skills and abilities of residents.

When interpreting results from this study, it should be noted that they may not be generalizable to other settings because the research was conducted in a family medicine teaching clinic and relies on a convenience sample of patients who agreed to participate. As mentioned previously, the research team did not record the total number of survey copies handed out to patients during the study period, thus the inability to calculate the survey response rate represents another limitation. Further, although self-perceived health status was not associated with the patients’ knowledge, acceptance and confidence, we could not assess if their specific medical conditions (i.e., mental health, sexual health, etc.) were related to the study outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, patients’ level of knowledge about the role and responsibilities of residents was low, even if the sample was from a medical teaching clinic. However, level of this knowledge was not related to patients’ confidence in residents, nor to patients’ acceptance toward being cared for by residents. Acceptance of receiving care from residents, in contrast, was greater among patients with higher confidence in residents’ abilities. University departments, teaching clinics and supervising physicians could therefore develop and test whether strategies to promote patient confidence in residents’ skills and abilities contribute to increasing acceptance of residents as health care providers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have conflicts of interest

Funding

No financial or material support was used for this project

References

- 1.Noordman, J., Post, B., van Dartel A.A.M. et al. Training residents in patient-centred communication and empathy: evaluation from patients, observers and residents. BMC Med Educ 19, 128 (2019). 10.1186/s12909-019-1555-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakar S, Levi D, Rosenberg R, Vinker S. Patient attitudes to being treated by junior residents in the community. Patient Educ Couns. 2010. Jan;78(1):111–6. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiggins MN, Coker K, Hicks EK. Patient perceptions of professionalism: implications for residency education. Med Educ. 2009. Jan;43(1):28-33. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AlGhamdi KM, Almohanna HM, Alkeraye SS, Alsaif FM, Alrasheed SK. Perceptions, attitudes, and satisfaction concerning resident participation in health care among dermatology outpatients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18(1):20–7. 10.2310/7750.2013.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malcolm CE, Wong KK, Elwood-Martin R. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of family medicine residents in the office. Can Fam Physician. 2008. Apr;54(4):570–1, 571.e1-6. PMCID: . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemphill RR, Santen SA, Rountree CB, Szmit AR. Patients’ understanding of the roles of interns, residents, and attending physicians in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999. Apr;6(4):339–44. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goerl K, Ofei-Dodoo S. Patient perception of medical learners and medical education during clinical consultation at a family medicine residency. Kansas Journal of Medicine. 2018. Nov; 11(4): 102–105. PMid: . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law M, Hamilton M, Bridge E, Brown A, Greenway M, Stobbe K. The effect of clinical teaching on patient satisfaction in rural and community settings. Can J Rural Med. 2014. Spring;19(2):57-62. PMid: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Malley PG, Omori DM, Landry FJ, Jackson J, Kroenke K. A prospective study to assess the effect of ambulatory teaching on patient satisfaction. Acad Med. 1997. Nov;72(11):1015-7. 10.1097/00001888-199711000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford GH, Gutman A, Kantor J, James WD. Patients’ attitudes toward resident participation in dermatology outpatient clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005. Oct;53(4):710–2. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santen SA, Hemphill RR, Prough EE, Perlowski AA. Do patients understand their physician’s level of training? a survey of emergency department patients. Acad Med. 2004. Feb;79(2):139–43. 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wray A, Feldman M, Toohey S, et al. Patient perception of providers: do patients understand who their doctor is? Journal of Patient Experience. Oct 2020:788-795. 10.1177/2374373519892780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kravetz AJ, Anderson CI, Shaw D, Basson MD, Gauvin JM. Patient misunderstanding of the academic hierarchy is prevalent and predictable. J Surg Res. 2011. Dec;171(2):467-72. 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unruh KP, Dhulipala SC, Holt GE. Patient understanding of the role of the orthopedic resident. J Surg Educ. 2013. May-Jun;70(3):345-9. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalia S, Schiffman FJ. who’s my doctor? First-year residents and patient care: hospitalized patients’ perception of their “main physician.” J Grad Med Educ. 2010. Jun; 2(2): 201–205. 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00082.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santen SA, Rotter TS, Hemphill RR. patients do not know the level of training of their doctors because doctors do not tell them. J Gen Intern Med. 2008. May; 23(5): 607–610. Published online 2007 Dec 21. 10.1007/s11606-007-0472-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guffey R, Juzych N, Juzych M. Patient knowledge of physician responsibilities and their preferences for care in ophthalmology teaching clinics. Ophthal. 2009. Sep;116(9):1610-4. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichgott MJ, Schwartz JS. Acceptance by private patients of resident involvement in their outpatient care. J Med Educ. 1983. Sep;58(9):703-9. 10.1097/00001888-198309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowles RA, Moyer CA, Sonnad SS, et al. Doctor-patient communication in surgery: attitudes and expectations of general surgery patients about the involvement and education of surgical residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2001. Jul;193(1):73-80. 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilmore W, Avery D, Tucker M, Higginbotham J. Patients’ knowledge and attitudes of medical students and residents. J Fam Med Community Heal. 2016;3(1):1075. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartz MB, Beal JR. Patients’ attitudes and comfort levels regarding medical students’ involvement in obstetrics-gynecology outpatient clinics. Acad Med. 2000. Oct;75(10):1010–4. 10.1097/00001888-200010000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahey M, Burnett M. What do patients attending an antenatal clinic know about the role of resident physicians? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010. Feb;32(2):160–4. 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grace AJ, Fields SA. The power of patient engagement: Implications for clinical practice and medical education. Intern J Psych Med. 2018;53(5-6):345-349. 10.1177/0091217418797540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin GL, Hooker RS. Patient willingness to be seen by physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and residents in the emergency department: does the presumption of assent have an empirical basis? Am J Bioeth. 2010. Aug;10(8):1-10. 10.1080/15265161.2010.494216. PMid: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempenich JW, Willis RE, Blue RJ, et al. The effect of patient education on the perceptions of resident participation in surgical care. J Surg Educ. Nov-Dec 2016;73(6):e111-e117. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]