Abstract

Objective:

Syndemic conditions have been linked to engagement in receptive condomless anal sex (CAS) and HIV seroconversion. However, little is known about the biological pathways whereby syndemics could amplify vulnerability to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Design:

HIV-negative sexual minority men (i.e., gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men) were recruited from four STI clinics in South Florida for a cross-sectional study.

Methods:

Participants completed assessments for four syndemic conditions: depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, hazardous alcohol use, and any stimulant use (i.e., any self-reported use or reactive urine toxicology results). Cytokine and chemokine levels were measured using LEGENDplex from the rectal swabs of 92 participants reporting receptive CAS and no antibiotic use in the past three months.

Results:

After controlling for age, race/ethnicity, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use, and number of receptive CAS partners, a greater number of syndemic conditions was associated with higher levels of rectal cytokines/chemokines relevant to immune activation, inflammation, and the expansion and maintenance of T-helper 17 target cells, including rectal interferon-gamma (β = 0.22; p = 0.047), CXCL-8 (β = 0.24; p = 0.025), and interleukin-23 (β = 0.22; p = 0.049). Elevations in rectal cytokine or chemokine levels were most pronounced among participants experiencing two or more syndemic conditions compared to those experiencing no syndemic conditions. PrEP use was independently associated with elevations in multiple rectal cytokines/chemokines.

Conclusions:

Syndemic conditions could increase biological vulnerability to HIV and other STIs in sexual minority men by potentiating rectal immune dysregulation.

Keywords: cytokines, inflammation, men who have sex with men, rectal mucosa, syndemics

Introduction

Syndemics is a theoretical framework proposing that various epidemics synergistically interact to amplify a disease state in the context of social inequities.[1] Syndemic models acknowledge that multiple psychosocial health comorbidities can combine dynamically to exponentiate risk for negative health outcomes, such as HIV seroconversion.[2–4] Among HIV-negative sexual minority men (i.e., gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men), composite measures of syndemic conditions such as depression, polysubstance use, hazardous alcohol use, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) predict greater risk for HIV seroconversion in a dose-response manner.[3, 5] Because syndemics research has largely focused on interactions between psychosocial conditions and disease, further evidence is needed to characterize biological pathways whereby syndemics could augment vulnerability to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Although an estimated 70% of HIV infections in sexual minority men occur during receptive condomless anal sex (CAS),[6–8] little is known about the correlates of rectal immune dysregulation relevant to HIV or STI risk.[9] The rectal mucosa has the highest per-act probability of HIV transmission,[10] because the columnar rectal epithelium contains many primary target cells for HIV, such as T-helper 17 (Th17) cells.[9] Receptive CAS also may induce epithelial damage and inflammation in the rectum. Kelly and colleagues[6] observed an increase in rectal pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and differences in microbial community structure among sexual minority men after receptive CAS. These inflammatory consequences of receptive CAS may be enhanced by co-occurring syndemic conditions. For example, the use of stimulants such as methamphetamine is associated with elevated rectal interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in sexual minority men regardless of HIV status.[11] Whether multiple, co-occurring syndemic conditions are associated with rectal immune dysregulation, particularly among HIV-negative sexual minority men engaging in receptive CAS, remains unknown.

When taken as prescribed, oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is more than 95% effective in preventing HIV seroconversion in sexual minority men,[12] but questions remain about the bio-behavioral determinants of greater STI vulnerability in men taking PrEP.[13] Two studies with sexual minority men demonstrated differences in several bacterial families in the rectal microbiome after PrEP initiation[14] and when compared to matched controls.[15] Although increases in STI incidence among men initiating PrEP may be due to behavioral disinhibition,[16] PrEP users could experience rectal immune dysregulation that amplifies biological vulnerability to STIs. Further research is needed to characterize the association of PrEP use with markers of rectal immune dysregulation to inform bio-behavioral STI prevention.

This cross-sectional study examined the independent associations of the number of syndemic conditions (i.e., depression, PTSD, hazardous alcohol use, and stimulant use) with rectal cytokine and chemokine levels among HIV-negative sexual minority men engaging in receptive CAS. We hypothesized that a greater number of syndemic conditions would be independently associated with elevations in rectal cytokine/chemokine levels even after adjusting for the number of receptive CAS partners and PrEP use.

Methods

Participants were recruited at AIDS Healthcare Foundation community STI clinics throughout South Florida. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) HIV-negative; 2) identifying as a sexual minority, cisgender man; and 3) age ≥ 18 years. Eligible participants provided written informed consent and completed a tablet-based survey. In total, 279 participants were enrolled, and rectal swabs were collected only from PrEP users, stimulant users, and those reporting receptive CAS. Rectal swabs were selected from 92 participants reporting any receptive CAS and no antibiotic use in the past three months. Data regarding STI diagnoses within a month of the study visit were extracted from medical records. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards for the University of Miami and Florida Department of Health.

Measures

Demographics and PrEP Use.

Age, race/ethnicity, education, income, sexual orientation, and relationship status were assessed via questionnaire. Participants also reported whether they were currently taking PrEP.

Receptive CAS Partners.

Participants reported the number of men with whom they had receptive CAS in the past three months.

Number of Syndemic Conditions.

An additive syndemic count variable was created by summing the number of conditions for which participants screened positive (range 0–4). Depressive symptoms were measured using the validated 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (study Cronbach’s α =.85).[17] Scores ≥ 10 were coded positive for depression. PTSD symptoms were measured using the Primary Care PTSD screener.[18] Individuals endorsing three or more symptoms were coded as screening positive for PTSD. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption screened for hazardous alcohol use.[19] Individuals scoring four or more were coded as screening positive for hazardous alcohol use. Participants who provided a urine sample that was reactive for stimulant metabolites (i.e., cocaine or methamphetamines) or self-reported any stimulant use in the past three months were classified as stimulant users.

Rectal Cytokines.

The LEGENDplex Human Inflammation Panel (BioLegend, San Diego, CA; Cat. No. 740118) was used to detect 13 human cytokines/chemokines from rectal swabs preserved in Puritan DNA/RNA Shield tubes (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). The rectal swab eluent was utilized for this assay, which was performed in duplicate.

Statistical Analyses

Due to a non-normal distribution, rectal cytokine/chemokine measures underwent a log10 transformation that allowed outcomes to meet assumptions for linear regression. Only rectal cytokines/chemokines with a normal distribution following log10 transformation were examined, namely interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin 12 p70 protein (IL-12p70), interferon alpha (IFN-α), IL-6, interleukin-17A (IL-17A), interleukin-23 (IL-23), interleukin-33 (IL-33), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL-8). Interleukin 1 Beta (IL-1β), TNF-α, interleukin 10 (IL-10), and interleukin 18 (IL-18) were measured but not examined as outcomes due to non-normal distributions following log10 transformation. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to determine if rectal cytokine/chemokine outcomes differed as a function of PrEP use and any STI diagnosis (specifically rectal STI) to examine if these variables should be used as covariates. The multivariate linear regression models examining whether the number of syndemic conditions was associated with each cytokine/chemokine included PrEP use, number of receptive CAS partners, race/ethnicity, and age as covariates. Because there was no significant association of any STI diagnosis with rectal cytokines/chemokines, this was not included in the models.

Results

Participants had a mean age of 37.7 (SD = 13.7) years. Most were non-Hispanic/Latinx White (46%) or Hispanic/Latinx (36%), had some college education (64%), and were not in a primary romantic relationship (58%). Participants experienced an average of 1.04 (SD = 0.97) syndemic conditions (24% depression, 9% PTSD, 46% hazardous alcohol use, and 27% stimulant use). One in five (n = 18) had gonorrhea or chlamydia infection regardless of site (i.e., oral, penile, or rectal). Of these, 89% (n = 16) had a rectal STI.

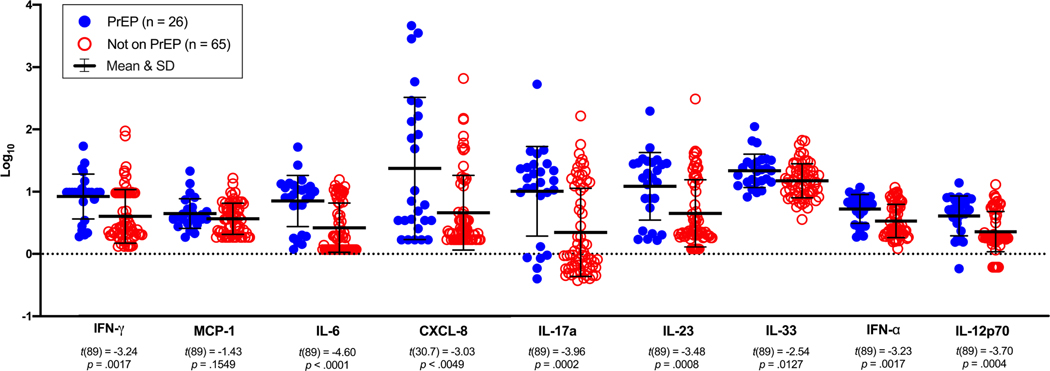

In the multivariate models, a greater number of syndemic conditions was independently associated with higher levels of three rectal cytokines/chemokines, IFN-γ, CXCL-8, and IL-23, after adjusting for PrEP use, receptive CAS partners, race/ethnicity, and age (see Table 1). In addition, PrEP use was independently associated with higher levels of rectal IFN-γ, IL-6, CXCL-8, IL-17A, IL-23, IFN- α, and IL-12p70 relative to those not taking PrEP. Figure 1 displays the mean differences in rectal cytokine/chemokine levels between men currently using PrEP relative to those not taking PrEP. Although PrEP use and number of syndemic conditions were positively correlated (Rho = 0.21, p =.055), this was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Multiple linear regression models predicting rectal cytokine or chemokine levels in HIV-negative sexual minority men (N = 88)

| Predictors: | → | # of syndemic conditions | Current PrEP use | Receptive CAS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model # | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Outcomes (Log10) | R 2 | β | SE | 95% CI | p | β | SE | 95% CI | p | β | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 1 | IFN-γ * | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.003, 0.44 | .047 | 0.24 | 0.12 | −0.01, 0.47 | .045 | 0.06 | 0.11 | −0.17, 0.28 | .623 |

| 2 | MCP-1 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.12 | −0.13, 0.34 | .394 | 0.14 | 0.12 | −0.11, 0.39 | .258 | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.25, 0.23 | .946 |

| 3 | IL-6 * | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.11 | −0.05, 0.37 | .134 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.12, 0.56 | .003 | 0.14 | 0.11 | −0.07, 0.35 | .197 |

| 4 | CXCL-8 * | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.03, 0.46 | .025 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.07, 0.52 | .011 | 0.06 | 0.11 | −0.16, 0.28 | .584 |

| 5 | IL-17a * | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.11 | −0.06, 0.37 | .164 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.08, 0.53 | .009 | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.14, 0.30 | .457 |

| 6 | IL-23 * | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.001, 0.44 | .049 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.05, 0.51 | .017 | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.20, 0.24 | .885 |

| 7 | IL-33 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.12 | −0.15, 0.31 | .512 | 0.24 | 0.12 | −0.005, 0.48 | .055 | 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.21, 0.26 | .846 |

| 8 | IFN-α | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.11 | −0.10, 0.35 | .267 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.01, 0.49 | .042 | 0.09 | 0.12 | −0.14, 0.32 | .453 |

| 9 | IL-12p70 * | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.11 | −0.02, 0.42 | .071 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.06, 0.52 | .016 | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.14, 0.30 | .486 |

| Post-hoc predictors: | → | 1 syndemic condition (REF=0) | 2–4 syndemic conditions (REF=0) | 2–4 syndemic conditions (REF=1) | ||||||||||

| Model # | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Outcomes (Log10) | R 2 | β | SE | 95% CI | p | β | SE | 95% CI | p | β | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 1 | IFN-γ * | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.12 | −0.04, 0.43 | .103 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.08, 0.59 | .012 | 0.15 | 0.13 | −0.11, 0.41 | .267 |

| 2 | MCP-1 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.25, 0.25 | .994 | 0.22 | 0.14 | −0.05, 0.50 | .111 | 0.22 | 0.14 | −0.06, 0.51 | .119 |

| 3 | IL-6 * | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.10, 0.34 | .279 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.06, 0.55 | .014 | 0.19 | 0.12 | −0.06, 0.44 | .129 |

| 4 | CXCL-8 * | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.12 | −0.07, 0.39 | .174 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.04, 0.55 | .024 | 0.14 | 0.13 | −0.12, 0.40 | .280 |

| 5 | IL-17a * | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.11, 0.35 | .314 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.03, 0.54 | .028 | 0.17 | 0.13 | −0.09, 0.43 | .187 |

| 6 | IL-23 * | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.12 | −0.09, 0.37 | .241 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.12, 0.63 | .005 | 0.24 | 0.13 | −0.02, 0.50 | .066 |

| 7 | IL-33 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.12 | −0.33, 0.16 | .488 | 0.21 | 0.13 | −0.05, 0.48 | .117 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.02, 0.59 | .035 |

| 8 | IFN-α | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.18, 0.30 | .644 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.02, 0.55 | .035 | 0.23 | 0.14 | −0.04, 0.50 | .091 |

| 9 | IL-12p70 * | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.12 | −0.14, 0.32 | .449 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.07, 0.58 | .014 | 0.24 | 0.13 | −0.02, 0.50 | .073 |

Notes. Predictors are listed horizontally and outcomes vertically on the left side representing each model run (i.e., each row = one multivariate linear regression model)

The overall model was significant; all the rectal cytokine biomarkers were Log10 transformed; The sample size for all models was 88 participants due to 4 observations missing data on the syndemic count variable; CAS = condomless anal sex; All models controlled for current PrEP use, receptive CAS, race or ethnicity, and age (race or ethnicity and age were not significant in any model); REF = referent group.

Figure 1.

Levels of rectal cytokines or chemokines by PrEP use in sexual minority men (N = 91)

Note. Independent samples t-tests were run to examine the bivariate associations of PrEP use with levels of each of the log10 transformed cytokines/chemokines. All the tests used the pooled method aside from CXCL-8, which used Satterthwaite due to inequality of variances (Folded F (25, 64) = 3.60, p < 0.0001).

Post-hoc sensitivity analyses repeated the series of regressions but collapsed the syndemic count variable into three categories: a) zero conditions (n = 30; 33%); b) one condition (n = 34; 37.0%); and c) 2–4 conditions (n = 28; 30%). Compared to those with no syndemic conditions, participants experiencing 2–4 syndemic conditions displayed significantly higher levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, CXCL-8, IL-17A, and IL-23 after adjusting for PrEP use, receptive CAS partners, race/ethnicity, and age. Compared to those experiencing one syndemic condition, participants experiencing 2–4 syndemic conditions displayed significantly higher levels of IL-33. Experiencing one syndemic condition was not significantly different from experiencing zero conditions. See Table 1 for parameter estimates.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study demonstrated that greater syndemic burden is independently associated with elevations in rectal cytokine/chemokine levels that could amplify biological vulnerability to HIV or STIs in sexual minority men engaging in receptive CAS. We observed that greater syndemic burden was associated with elevations in rectal cytokines/chemokines linked to immune activation (IFN-γ), neutrophil chemoattraction and infiltration (CXCL-8), and the expansion and maintenance of Th17 cells (IL-6, IL-17A, and IL-23), a primary target for HIV infection.[20–23] Findings contribute to an emerging area of inquiry by highlighting that syndemic conditions are associated with dysregulated rectal immune responses relevant to HIV/STI acquisition.

Syndemic burden is linked to increased risk of HIV seroconversion,[3, 24, 25] and results build upon prior studies examining the implications of specific syndemic conditions such as methamphetamine use[11, 26] and receptive CAS[6] for rectal immune dysregulation. Among HIV-negative sexual minority men, increased rectal IL-17 production has been demonstrated following engagement in receptive CAS.[6] Furthermore, a recent study found that increased rectal CD4+IL-17A+IFN-γ+TNF-α+ Th17 cell subsets correlated with a higher frequency of HIV target cell availability,[23] which is associated with more efficient mucosal transmission.[27] We also found some evidence that those with the greatest number of syndemic conditions displayed elevated IL-33 compared to those with one syndemic condition. IL-33 has been implicated in HIV-associated gut barrier dysfunction,[28] and future research should examine the relevance of elevations in IL-33 for HIV seroconversion risk.

PrEP users also displayed elevations in multiple rectal cytokines/chemokines (IFN-γ, IL-6, CXCL-8, IL-17A, IL-23, IFN-α, and IL-12p70), providing evidence of dysregulated rectal immune responses. Greater rectal immune dysregulation could partially explain the higher incidence of STIs among PrEP users.[16] Future studies should examine whether rectal immune dysregulation partially mediates the higher incidence of rectal STIs among sexual minority men taking PrEP. Further mechanistic research should also determine whether alterations in rectal immune responses are attributable to the effects of specific PrEP medications on microbiome composition or more frequent engagement in receptive CAS among men taking PrEP.[29]

Findings from this study have important limitations. PrEP use was self-reported, and adherence levels were not objectively measured. Participants recruited from community STI clinics are not representative of the broader population of sexual minority men, but they do represent a sub-group with elevated HIV/STI risk. Although participants were instructed on rectal self-swabbing, variations in individual swabbing practices are possible.[30] Future longitudinal studies should concurrently measure cytokine levels in plasma[11, 31] and examine the distribution and function of immune cells from the rectum to better elucidate the underlying bio-behavioral mechanism(s) whereby syndemic burden could potentiate rectal immune dysregulation. Finally, the modest sample size limited our ability to explore more nuanced interactions between specific syndemic conditions.[32] This should be examined in subsequent research with adequate statistical power for testing interactions.

Nevertheless, this study is among the first to provide evidence that the number of syndemic conditions and PrEP use are independently associated with elevations in cytokines/chemokines relevant to rectal immune dysregulation among HIV-negative sexual minority men engaging in receptive CAS. This provides novel insights regarding the biological pathways whereby syndemic burden could amplify HIV/STI risk and informs mechanistic research examining determinants of rectal immune responses in this high priority population.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (Carrico, PI). Additional support was provided by the Miami Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI073961; Pahwa, PI) and the Center for HIV Research and Mental Health (P30-MH116867; Safren, PI).

References

- 1.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet 2017; 389(10072):941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walkup J, Blank MB, Gonzalez JS, Safren S, Schwartz R, Brown L, et al. The impact of mental health and substance abuse factors on HIV prevention and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47 Suppl 1:S15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Safren SA, Coates TJ, et al. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68(3):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons JT, Millar BM, Moody RL, Starks TJ, Rendina HJ, Grov C. Syndemic conditions and HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in a U.S. national sample. Health Psychol 2017; 36(7):695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2003; 93(6):939–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley CF, Kraft CS, de Man TJ, Duphare C, Lee HW, Yang J, et al. The rectal mucosa and condomless receptive anal intercourse in HIV-negative MSM: implications for HIV transmission and prevention. Mucosal Immunol 2017; 10(4):996–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hladik F, McElrath MJ. Setting the stage: host invasion by HIV. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8(6):447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS 2009; 23(9):1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez SM, Aguilar-Jimenez W, Su RC, Rugeles MT. Mucosa: Key Interactions Determining Sexual Transmission of the HIV Infection. Front Immunol 2019; 10:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel P, Borkowf CB, Brooks JT, Lasry A, Lansky A, Mermin J. Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review. AIDS 2014; 28(10):1509–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fulcher JA, Shoptaw S, Makgoeng SB, Elliott J, Ibarrondo FJ, Ragsdale A, et al. Brief Report: Recent Methamphetamine Use Is Associated With Increased Rectal Mucosal Inflammatory Cytokines, Regardless of HIV-1 Serostatus. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 78(1):119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jt Riddell, Amico KR, Mayer KH. HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis: A Review. JAMA 2018; 319(12):1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto-Cardoso S, Klatt NR, Reyes-Teran G. Impact of antiretroviral drugs on the microbiome: unknown answers to important questions. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2018; 13(1):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dube MP, Park SY, Ross H, Love TMT, Morris SR, Lee HY. Daily HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine reduced Streptococcus and increased Erysipelotrichaceae in rectal microbiota. Sci Rep 2018; 8(1):15212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulcher JA, Li F, Cook RR, Zabih S, Louie A, Okochi H, et al. Rectal Microbiome Alterations Associated With Oral Human Immunodeficiency Virus Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2019; 6(11) ofz463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, Price B, Roth NJ, Willcox J, et al. Association of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis With Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Individuals at High Risk of HIV Infection. JAMA 2019; 321(14):1380–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 1994; 10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and Evaluation Within a Veteran Primary Care Sample. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(10):1206–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158(16):1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klatt NR, Brenchley JM. Th17 cell dynamics in HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5(2):135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I. Interleukin-8, a chemotactic and inflammatory cytokine. FEBS Lett 1992; 307(1):97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billiau A. Interferon-gamma: biology and role in pathogenesis. Adv Immunol 1996; 62:61–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amancha PK, Ackerley CG, Duphare C, Lee M, Hu YJ, Amara RR, et al. Distribution of Functional CD4 and CD8 T cell Subsets in Blood and Rectal Mucosal Tissues. Sci Rep 2019; 9(1):6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mimiaga MJ, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Oldenburg CE, Rosenberger JG, O’Cleirigh C, et al. High prevalence of multiple syndemic conditions associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV infection among a large sample of Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking men who have sex with men in Latin America. Arch Sex Behav 2015; 44(7):1869–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos GM, Do T, Beck J, Makofane K, Arreola S, Pyun T, et al. Syndemic conditions associated with increased HIV risk in a global sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2014; 90(3):250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook RR, Fulcher JA, Tobin NH, Li F, Lee DJ, Woodward C, et al. Alterations to the Gastrointestinal Microbiome Associated with Methamphetamine Use among Young Men who have Sex with Men. Sci Rep 2019; 9(1):14840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolodkin-Gal D, Hulot SL, Korioth-Schmitz B, Gombos RB, Zheng Y, Owuor J, et al. Efficiency of cell-free and cell-associated virus in mucosal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 2013; 87(24):13589–13597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehraj V, Ponte R, Routy JP. The Dynamic Role of the IL-33/ST2 Axis in Chronic Viral-infections: Alarming and Adjuvanting the Immune Response. EBioMedicine 2016; 9:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen K, Steffen G, Potthoff A, Schuppe AK, Beer D, Jessen H, et al. STI in times of PrEP: high prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and mycoplasma at different anatomic sites in men who have sex with men in Germany. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20(1):110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pescatore NA, Pollak R, Kraft CS, Mulle JG, Kelley CF. Short Communication: Anatomic Site of Sampling and the Rectal Mucosal Microbiota in HIV Negative Men Who Have Sex with Men Engaging in Condomless Receptive Anal Intercourse. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2018; 34(3):277–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Meditz A, Wilson C, Zheng JH, Palmer BE, Lee EJ, et al. Reduced immune activation during tenofovir-emtricitabine therapy in HIV-negative individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68(5):495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai AC, Venkataramani AS. Syndemics and Health Disparities: A Methodological Note. AIDS Behav 2016; 20(2):423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]