Abstract

Uganda piloted HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for priority populations (sex workers, fishermen, truck drivers, discordant couples) in 2017. To assess facilitators and barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence, we explored perceptions of PrEP before and experiences after rollout among community members and providers in south-central Uganda. We conducted 75 in-depth interviews and 12 focus group discussions. We analyzed transcripts using a team-based thematic framework approach. Partners, family, peers, and experienced PrEP users provided adherence support. Occupational factors hindered adherence for sex workers and fishermen, particularly related to mobility. Pre-rollout concerns about unskilled/untrained volunteers distributing PrEP and price-gouging were mitigated. After rollout, awareness of high community HIV risk and trust in PrEP effectiveness facilitated uptake. PrEP stigma and unexpected migration persisted as barriers. Community-initiated, tailored communication with successful PrEP users may optimize future engagement by addressing fears and rumors, while flexible delivery and refill models may facilitate PrEP continuation and adherence.

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis, implementation science, Uganda, sex workers, fishing communities

RESUMEN

En 2017, Uganda introdujo profilaxis pre-exposición (PrEP), dirigida a las populaciones con alto riesgo de contraer al VIH (trabajadoras sexuales, pescadores, camioneros, parejas sero-discordantes). Para investigar facilitadores y barreras para la adopción y la adherencia a la PrEP, exploramos percepciones de PrEP antes y después de su introducción en Uganda. Realizamos 75 entrevistas y 12 grupos focales con miembros de la comunidad y trabajadores de salud. Analizamos las transcripciones temáticamente usando un marco de referencia. Parejas, familias, compañeros, y clientes usando PrEP apoyaron a los demás mantener adherencia. Movilidad fue una barrera para la adherencia a la PrEP para trabajadoras sexuales y pescadores. Preocupaciones sobre el entrenamiento de los distribuidores de PrEP y la especulación de precios no fueron realizadas. Percepciones del riesgo del VIH y confianza en la eficacia de PrEP facilitaron su adopción. Estigma y migración inesperada persistieron como barreras para la adopción de PrEP. Comunicaciones manejadas por clientes usando PrEP pueden motivar interés en PrEP y abordar rumores. Sistemas flexibles del entrego y la recarga de medicinas pueden permitir continuación de, y adherencia a, la PrEP.

INTRODUCTION

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a promising component of combination prevention for individuals at risk of HIV acquisition (1–3). In sub-Saharan Africa, studies among priority populations such as HIV-serodiscordant couples, female sex workers, adolescent girls and young women, and fishermen have reported high willingness (60–90%) to use PrEP (4–8). By mid-2018, PrEP pilot programs among priority populations were introduced widely in several sub-Saharan African countries, with mixed results. In the Partners PrEP trial in Kenya, men who have sex with men (MSM) and HIV-serodiscordant couples showed high uptake (97%), retention (>90% at three months), and adherence (>80%) to PrEP (9–11); high rates of PrEP uptake (82.4%) and retention (73.4% at 12 months) were also seen in a demonstration project among sex workers in Benin (12). However, low uptake (18%) was observed when PrEP was offered with door-to-door HIV testing in the SEARCH study in rural Kenya and Uganda (13); and PrEP adherence among female sex workers in the TAPS Demonstration Project in South Africa fluctuated widely over 12-month follow-up (14). In Uganda, sex workers described challenges with PrEP uptake and adherence including alcohol use, irregular working hours, and fear that the pills will be confused with HIV treatment (15); another study asking Ugandan priority populations (MSM, sex workers, fishermen, and serodiscordant couples) about potential barriers to PrEP found that accessibility of health facilities, stigma, busy schedules, forgetting, and alcohol use were commonly anticipated concerns (16).

Previous systematic reviews have underscored the need to evaluate how PrEP programs can be optimized among high-risk populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Important knowledge gaps include how to increase PrEP awareness, uptake, adherence, and retention and how to address fear of PrEP disclosure, stigma, mobility, transportation costs, and mismatches between consistent PrEP dosing and unpredictable lifestyles (17, 18).

Fishing villages and nearby communities have been identified as hyperendemic geographic “hotspots” for HIV: complex gendered patterns of migration, transactional sex, substance abuse, infrequent condom use, and health service disengagement cultivate a risk environment for heightened HIV acquisition and transmission (19–21). Despite this high HIV burden, coverage and use of HIV services along the prevention, care, and treatment continuum have historically been inadequate. For example, from 2011–13, among HIV-seropositive residents of fishing communities in south-central Uganda, only 18% of women and 13% of men reported antiretroviral therapy (ART) use (19), and uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention and HIV testing and counseling were similarly suboptimal (21). While many of these indicators have improved dramatically after focused programmatic attention to fishing communities in recent years (20), these communities remain a high priority for HIV service delivery.

Identifying strategies to engage people who are not using HIV services with new prevention tools like PrEP is necessary to curb HIV transmission. A more in-depth understanding of the facilitators and barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence may improve future PrEP scale-up in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among priority populations. Our goal in this qualitative study was to explore and compare clients’ and health service providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences surrounding PrEP before and after it was rolled out in late 2017 by the Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) in HIV-hyperendemic Lake Victoria fishing communities (HIV prevalence around 41% (22)) and trading centers (HIV prevalence around 13% (22)) in Rakai, Kyotera, and Masaka Districts of south-central Uganda. Using a longitudinal design, we identify which concerns had been addressed during program rollout and characterize differences between expectations and realities of user experiences.

METHODS

The RHSP PrEP program

In November 2017, with support from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-Uganda, RHSP initiated a pilot PrEP program (23). It was one of a few PrEP demonstration sites in Uganda, selected for its extremely high HIV burden. Providers were trained on PrEP basics (e.g. what is PrEP, why is PrEP needed, benefits of PrEP, identification of individuals at substantial risk for HIV infection, relationship between PrEP effectiveness and adherence, PrEP regimens recommended in Uganda, PrEP implementation concerns), screening for PrEP eligibility, counselling and care provision at initial and follow-up visits, monitoring and managing PrEP side effects, stigma, and PrEP monitoring and evaluation tools. After intensive community mobilization and sensitization, including megaphone announcements in fishing communities and peer/venue-based outreach, the program screened and enrolled HIV-negative individuals aged >= 15 years who self-reported being at substantial risk of HIV acquisition, including fishermen, female sex workers, truckers, and HIV-serodiscordant couples, at health facilities and outreach centers. Eligible clients were counselled on the need for daily dosing, potential side effects, and when PrEP could be discontinued. They were also given contact information in case of further questions or problems. Enrolled clients were requested and received follow-up phone reminders to return to program clinics for PrEP refills, additional risk assessment, adherence counselling, and HIV retesting 30 days after initiation and every three months thereafter. Refill schedules were flexible to fit client preferences.

A quantitative evaluation of the RHSP PrEP program (April 2018-March 2019) showed that it was initially highly successful at enrolling eligible individuals (23). Out of 2,985 individuals screened for PrEP eligibility, 2,751 were offered PrEP, and 2,536 (92.2%) accepted and enrolled on PrEP. However, early PrEP discontinuation was high, with a median retention of only 45.4 days. Discontinuation was higher among female sex workers, fishermen, and truck drivers compared to HIV-serodiscordant couples. Retention did not differ by age or marital status.

Data collection

Qualitative data were gathered before and after PrEP rollout. In May-August 2016 and August-September 2017, we conducted a formative study using semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDIs) to explore knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about the proposed PrEP program among fishing community members and service providers in three high-HIV-burden fishing villages on Lake Victoria (Kasensero, Ddimo, and Malembo). The interview guides covered knowledge and perceptions of PrEP, perceived barriers to and facilitators of PrEP uptake and adherence, possible avenues of misuse among end-users, and acceptability of potential program components. Service providers responded to the same questions and were also asked about logistics and operational feasibility of the proposed PrEP program.

In March-June 2019 (approximately one year after PrEP roll-out), we conducted a follow-up study in fishing villages and trading communities to understand people’s experiences with PrEP, ascertain reasons for low adherence, and identify preferred PrEP delivery models that would increase uptake, adherence, and retention. IDIs were used to elicit open-ended responses, encourage discussion, and enable probing at an individual narrative level; focus group discussions (FGDs) captured broader community norms among groups of community members of the same gender and in the same age range. Both IDI and FGD field guides included questions on the following domains: perspectives on the PrEP initiation process, PrEP user experiences and adherence challenges, drivers of PrEP discontinuation, and recommendations to strengthen PrEP delivery.

For both rounds of data collection, and for both IDIs and FGDs, with help from RHSP community health workers, participants were purposively recruited from existing Rakai Community Cohort Study (RCCS) computer-generated lists of community members who had agreed to be contacted to participate in future studies. We purposively sampled higher-risk subgroups in fishing villages: female sex workers, fishermen, and other sexually active women 18 years and older, as well as healthcare providers. After rollout, we purposively sampled service providers (e.g. HIV clinicians, PrEP program coordinators) as well as client subgroups from the fishing village and trading center communities, including non-acceptors of PrEP, new PrEP initiates, PrEP users with durable adherence (determined by pill-counting (>80% use), self-report (did not miss taking PrEP in the last 3 days), and appointment-keeping (kept appointment dates for PrEP refills)), non-adherent PrEP users, and people who discontinued PrEP. For one specific subgroup, snowball sampling among peer leaders was also employed to consecutively identify and recruit more female sex workers for the study.

Potential participants were approached through peer leaders and community health mobilizers. All participants were given study information and provided written consent to participate. IDIs and FGDs lasting approximately 90 minutes were conducted by trained, experienced interviewers in the local language (Luganda) in a private location of the interviewee’s choice or at community venues (e.g. church, school) suggested by FGD participants. Interviews were audio-recorded with consent from participants, and the audio recordings were destroyed after data were transcribed and translated into English.

The studies were reviewed and approved by Ugandan IRBs (the Research and Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology), and by the Western IRB and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine eIRB in the U.S.

Analysis

Textual data were analyzed using a thematic framework approach (24, 25) to understand awareness of PrEP, uptake, adherence, and retention. Transcripts were repeatedly and independently read and coded by multiple co-authors. A coding framework was developed, reflecting a set of textual codes developed from recurring categories and themes (26). An iterative process of data analysis was employed: codes and categories were identified and examined by co-authors, and variations, richness, and links between them were explored to develop, refine, and categorize themes (27). Regular team debriefs and memos aided synthesis. Themes were derived both deductively and inductively until data saturation was reached across the participant sub-groups and topic guides (28). Emerging themes and categories were entered in a data synthesis template. Co-authors then organized findings according to three dimensions: before versus after PrEP roll-out, steps along Nunn et al.’s PrEP continuum of care (29), and a multi-level socio-ecological model (interpersonal or household, occupation, program, and community levels). As other studies have thoroughly explored individual-level factors for PrEP usage (30–34), we focused on these other levels.

RESULTS

Tables 1 (IDIs) and 2 (FGDs) present participant demographics. Prior to PrEP rollout, we conducted 32 IDIs in three fishing communities: 6 providers, 10 fishermen, 12 female sex workers, and 4 sexually active women. A year after PrEP rollout, we conducted 43 IDIs and 12 FGDs in fishing villages and trading communities. The IDIs conducted after program rollout among actual and potential end-users included 6 who had declined PrEP, 3 newly started on PrEP, 15 on PrEP and adherent, 7 on PrEP with poor adherence, and 8 who discontinued PrEP, as well as 4 service providers. The FGDs included 94 community members representing men and women across age bands. Altogether, we included 169 participants: 62 men (age range: 15–47 years) and 107 women (age range: 15–42 years).

Table 1.

Characteristics of in-depth interview participants, before and after PrEP rollout in Rakai

| Number of participants, by steps along the PrEP cascade a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of participant | Before (2017) | After (2019) | |||||

| Hypothetical PrEP usage | Declined PrEP | Newly started PrEP | On PrEP (Adherent) | On PrEP (Non-adherent) | Discontinued PrEP | ||

| Community members | 6 | 3 | 15 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Sexually active women (fishing villages) | 4 | 0 | |||||

| Individual in a HIV sero-discordant relationship (mainland and fishing villages) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Fishermen (fishing villages) | 10 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 15 |

| Sex workers (mainland and fishing villages) | 12 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 17 |

| Service providers | 6 | 4 | |||||

| TOTAL IN-DEPTH INTERVIEW PARTICIPANTS, BEFORE AND AFTER ROLLOUT | 75 | ||||||

On PrEP (Adherent) refers to PrEP users with durable adherence, determined by any one of three measures taken at the local PrEP clinic: pill-counting (>80% use), self-report (did not miss taking PrEP in the last 3 days), and appointment-keeping (kept appointment dates for PrEP refills). On PrEP (Non-adherent) refers to PrEP users who did not meet any of these three criteria.

Table 2.

Characteristics of focus group discussion participants, after PrEP rollout in Rakai

| Type of participant | Number of participants, by age band (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community members | 15–19 | 20–34 | 35+ | |

| Men | 6 | 10 | 16 | 32 |

| Women | 32 | 15 | 15 | 62 |

| TOTAL FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (n=12) PARTICIPANTS | 94 | |||

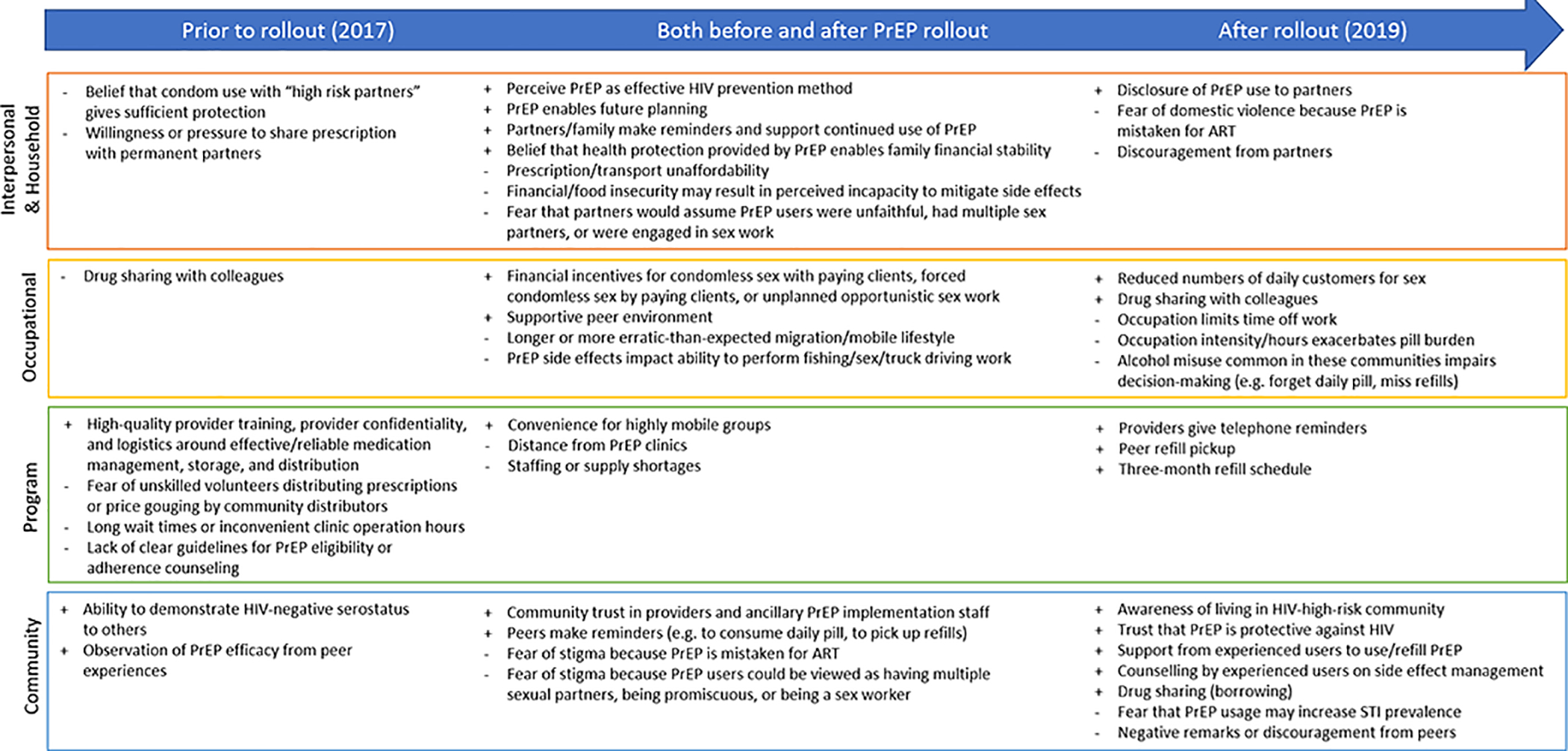

Emergent themes with illustrative quotes are organized according to interpersonal/household (Table 3), occupation (Table 4), program (Table 5), and community (Table 6) levels to characterize and illustrate multi-level aspects of PrEP uptake and adherence. Below and summarized in Figure 1, we present facilitators and barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence, as described by participants before and after PrEP rollout.

Table 3.

Facilitators and barriers of PrEP uptake and adherence at the interpersonal and household level.

| Theme | Timing | Illustrative quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Perceive PrEP as effective HIV prevention method which they can control if living with untrusted partner, mistrust partner's HIV status, or unable to negotiate safe sex (e.g. condom use with permanent partners) | Both | This is what forced me to go on PrEP. Our wives here at the fishing site cannot be trusted. You cannot stand and say she is my wife and mine alone, not at all. So, I found myself at risk of getting HIV, and I decided to take PrEP. (IDI, male, 42 years old, fisherman, remaining on PrEP and adherent) |

| PrEP enables future-planning: desire to remain in a sero-discordant relationship or have a child with a sero-discordant partner (safer conception) | Both | I am ready to take PrEP because I have a partner whom I have been with for over a year. When we first stayed together, I did not know that she had HIV. When she became pregnant—she’s now five months pregnant—she was tested when she was three months pregnant, and she had HIV. I don’t have HIV, but she has it, so if PrEP is introduced, it can help me remain negative. And if she adheres to her medicine well, we can stay together and bring up our children. (IDI, male, 30 years old, fisherman, fishing village) | |

| Partners/family make reminders and provide support for continued use of PrEP | Both | Sometimes I did not take my medicine, or I went back home late… you know, sometimes I ride a boda boda [motorcycle] and spend the entire day away. When I go back at night, she [my wife] tells me to swallow my medicine. (IDI, male, 23 years old, fisherman, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Belief that health protection provided by PrEP enables family financial stability | Both | Most of them [fishermen] have spent a long time on the waters fishing and make a lot of money, but the moment they step off the boat, it is crates and crates of beer that are going to line up there. Then he will eat up all his money until he has nothing left without even buying a shirt for himself because he knows that he is dying any time. (IDI, female, 33 years old, sex worker, fishing village) | |

| Disclosure of PrEP use to partners (transparency in communication) | After | If you are open to your partner and you told him about your taking PrEP, it is easy to take it freely. It can be easier if the people you stay with know that you are taking PrEP. It is not good to hide the medicine. (FGD, females, 15–19 years old, community members, mainland) | |

| Barriers | Belief that condom use with "high-risk partners" gives sufficient protection | Before | I do think that people’s sexual restraint is going to plummet because that pill is going to boost people’s confidence, and they will discard things like condoms... Even If they are going to someone who is HIV positive, they will go confidently, regardless of whether they are taking the pill well or not. (IDI, female, 22 years old, sexually active community member, fishing village) |

| Willingness or pressure to share prescription with permanent partners | Before | It is possible for people to share with their sexual partners as long as there are no other processes like testing for CD4 count or something else. (IDI, male, 26 years old, service provider) | |

| Unaffordability of prescription and high transport costs for refill | Both | A client can tell you that I come from [location], it requires 20,000 shillings [approximately 7 USD] for transport to Rakai hospital. They can stop PrEP and tell you, "Musawo [doctor], I cannot even manage it." (IDI, male, 27 years old, service provider) | |

| Financial/food insecurity may result in perceived incapacity to mitigate side effects | Both | If I have money saved, I can begin PrEP right away but if I don’t have money, I can postpone starting PrEP and take it after saving some money so that any time PrEP makes me feel dizzy or vomit severely, I have money to buy food. (IDI, male, 44 years old, fisherman, fishing village) | |

| Fear that partners would assume PrEP users were unfaithful, had multiple sex partners, or were engaged in sex work | Both | She might be suspicious that they can tell her partner that she takes that medicine. Someone can approach your partner and tell him that "I saw your wife taking PrEP yet they said that it is for sex workers. Why does she take it? It means she has another man." She can add, "Go and make some investigations. She might be having another man." Such things can cause domestic violence due to those suspicions. You know PrEP has some resemblances with ARV. He might have seen those tablets and suspect them to be taken by HIV patients. So, he might think that the wife is just hiding her HIV positive status from him. (FGD, females, 20–34 years old, community members, fishing village) | |

| Fear of domestic violence because PrEP is mistaken for ART | After | Some of our members who were married faced domestic violence; they were beaten by their husbands because they thought it is a pill for HIV treatment. Although PrEP pill and ARVs almost look the same, but if you are so keen/observant, there is some difference. [...] The tin used that was used for packaging is not the same, (informant smiles). Then in terms of size; ARV is bigger as opposed to PrEP pill. In terms of length; PrEP pill is not so long as compared to ARVs. However, for someone who has never seen PrEP pill before, or when he or she is not so keen, the same person may confuse it with ART (ARVs). In fact, for people who are using PrEP, we are being taken as persons who are HIV positive. For people who don’t know anything about PrEP, they cannot tell the difference; for example, I met one of my friends and asked, “Hey, are you also enrolled on ART?” In other words, most people mix up PrEP with ART for HIV treatment. (IDI, female, 26 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Discouragement from partners | After | Supposing your husband finds your medicine [PrEP], won’t he think you already have HIV? Exactly. The moment he finds my medicine, he will say, “This woman already got the HIV and did not tell me? She is HIV-positive and already on treatment?” That is how he may perceive it. (IDI, female, 43 years old, discordant couple, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) |

Table 4.

Facilitators and barriers of PrEP uptake and adherence at the occupational level (for priority populations).

| Theme | Timing | Illustrative quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Financial incentives for condomless sex with paying clients, forced condomless sex by paying clients, or unplanned opportunistic sex work | Both | As sex workers, we had a lot of problems before. Sometimes you could agree with a man to use a condom, but when you enter in the lodge, he refuses to use it. You may not have the power to fight him. So, if that situation happens and he uses you without a condom you may not acquire HIV in case you take that medicine. (IDI, female, 28 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) |

| Supportive peer environment | Both | They advise you that you can do everything you want but you should not forget taking your medicine. So, my colleagues advise me to take my medicine especially when I am travelling to work somewhere far from here. (IDI, female, 28 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Reduced numbers of daily customers for sex | After | I reduced on the number of men. I no longer rush to have sex with a man because I take PrEP. (IDI, female, 28 years old, sex worker, fishing village, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Drug sharing with colleagues | After | If I am stuck, I can borrow some tablets from a colleague and [take them]. That is how my colleagues support me. There is a time we move far, when some of them forgot the drugs or it got finished on the way, but you use the medicine of a colleague who still has some tablets. (IDI, female, 28 years old, sex worker, fishing village, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Barriers | Drug sharing with colleagues | Before | I think everyone should get their own medicine to effectively prevent HIV. When we share it and it get finished and we continue having sex with different sexual partners, shall we not become infected with HIV and then think that the medicine was not effective? Yet we used it wrongly by sharing it. I think everyone should get his or her medicine. (IDI, female, 26 years old, sex worker, fishing village) |

| Longer or more erratic-than-expected migration / mobile lifestyle (limiting access to PrEP or other HIV services) | Both | Another thing, the challenge we [PrEP service providers/nurses] have encountered in this is that our clients are mobile. For example, the commercial sex workers: you can provide services to her today and then she migrates to another area without even telling you. (IDI, male, 27 years old, service provider) | |

| PrEP side effects impact ability to perform fishing/sex/truck driving work | Both | I had strong cough coupled with serious chest pain. In this case, I thought about going for HIV testing with assumption that I may have been infected with HIV. I also lost the energy and I was too weak to use the fishing nets during our fishing activities as fishermen. This explains why I stopped taking my PrEP medicine. (IDI, male, 38 years old, fisherman, fishing village, remaining on PrEP but non-adherent) | |

| Occupation limits time off work | After | For some people who are employees, they may not be allowed to come for their PrEP medicine. The time for going to get their medicine, this might be the same time when customers are coming in. We work as employees as bar workers, or waitresses in restaurants or hotels. For the case of hotels, during mid-day, we are already serving customers. During morning hours, we are always preparing food. During evening time, we are busy washing utensils and thereafter return home. Therefore, it is very difficult for your boss to give you permission [to go for appointments or to pick up refills] and he or she sees that you are still healthy. Most PrEP users are employees somewhere, and it is hard to fix your own time. I must first talk to my employer/boss to seek permission. Sometimes my boss may refuse. (IDI, female, 26 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Occupation intensity/hours exacerbates pill burden (once a day at the same time each day) | After | As fishermen, we start work from 12:00 pm midnight until 11:00 Am. If you are not careful, you may find yourself missing a dose. (IDI, male, 29 years old, fisherman, fishing village, non-acceptor/decliner of PrEP) | |

| Alcohol misuse common in sex work venues and fishing communities impairs decision-making (e.g. forget daily pill, miss picking up refills) | After | I take it at 9am in the morning, when not yet in the bar. I am still resting at home. If I start taking alcohol, I can forget taking the medicine. (IDI, female, 26 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) |

Table 5.

Facilitators and barriers of PrEP uptake and adherence at the program level.

| Theme | Timing | Illustrative quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | High-quality provider training, provider confidentiality, and logistics around effective/high quality/reliable medication management, storage, and distribution | Before | Health workers from the clinic are more trained compared to community health workers. If I have not understood well on how to use that medicine [PrEP], he can explain to me more how to use, keep it in order to know more about it. (IDI, female, 22 years old, sex worker, fishing village) |

| Convenience for highly mobile groups | Both | The health worker brings the medicine here to us. We gather at the church and get PrEP. He comes on a motorcycle and parks at the church. He then gets one of us to go and look for all PrEP users to come for their refills. (IDI, male, 30 years old, discordant couple, fishing village, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Providers give telephone reminders | After | They used to write dates for us and included the day when we shall go back and get PrEP. When the date is due, they take the initiative to call you on phone and remind you. When you reach at the center, you go and get the medicine... There is no more challenge I find because we go and get the medicine. (IDI, female, 26 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP but non-adherent) | |

| Peers can pick up refills for others | After | We help each other because even when the refill dates are due, she might have forgotten but then you remind her, or I might have forgotten, and she reminds me that lets go and get our medicine. That is how we support each other. (IDI, female, 39 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Three-month refill schedule (instead of one-month) | After | The period of one month is really very hard and most people fail to adhere to it. However, clients of three months are okay because they prepare for it in advance, so that after three months they can go back for the refill. (IDI, male, 27 years old, service provider) | |

| Barriers | Fear of unskilled community health workers distributing inauthentic or expired prescriptions or price gouging by community distributers (lack of fixed, transparent pricing) | Before | If PrEP cost three hundred shillings, a community health worker will tell you that it costs four hundred shillings. (IDI, male, 26 years old, fisherman) |

| Long wait times or clinic operation hours incompatible with PrEP client availability, and lack of clear guidelines for PrEP eligibility or adherence counselling | Before | [During PrEP training] it was mentioned that sex workers would not prefer to wait for long hours or lining up at the health center. Instead, a sex worker needs instant attention the moment she arrives at the health center. [But so far] we have not organized for a private room specifically for PrEP and no specific health provider deployed to work on PrEP. (IDI, female, 34 years old, service provider) | |

| Distance from PrEP clinics | Both | The other challenge would be distance. There are people that we started on PrEP in Kyabasimba, we don’t have facilitation to go back to Kyabasimba. If we had transport back to Kyabasimba, I would know that I have to go there every month or after two months and give them medicine. There are some places along the lake shores that aren’t easily accessible because you can’t go there with motorcycles, you have to walk there. (IDI, male, 25 years old, service provider) | |

| Staffing or supply shortages | Both | Today if I leave here and I go to Kyazanga [a nearby town], where will I get it [PrEP] from? I have come here to get it. It is out of stock on that side of ours, so even though I need transport to come back this side to pick it up, then I say, "Aha let me go to the clinic [here] to get PrEP." (FGD, males, 20–34 years old, community members, fishing village) |

Table 6.

Facilitators and barriers of PrEP uptake and adherence at the community level.

| Theme | Timing | Illustrative quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Ability to demonstrate HIV-negative serostatus to others | Before | Every time someone scorns you over ARVs, you die a little inside. So most people hide [ART use] for that reason, while for PrEP, it is not scary because you swallow it while you are healthy. You can even come from the health center and show off your receipt to people. (IDI, female, 33 years old, sex worker) |

| Observation of PrEP efficacy from peer experiences | Before | He [fisherman] is already prepared since he took his medicine [PrEP] and it functions properly, thus he is not worried of anything because he is protected. (IDI, female, 22 years old, sex worker) | |

| Community trust in providers and ancillary PrEP implementation staff | Both | First, the service providers working on PrEP are good people. They explain to you and finally make your own decision.You first go for HIV testing. If you are diagnosed as HIV negative, then you are eligible to receive PrEP medicine. (IDI, female, 26 years old, discordant couple, mainland, remaining on PrEP but non-adherent) | |

| Peers make reminders (e.g. to consume daily pill, to pick up refills) | Both | PrEP medicine is the first item I put in my wallet before I leave home. Sometimes I leave my workplace very late and yet I am supposed to take my medicine. My PrEP companion can also remind me about taking my medicine through phone call. This is how I can take my medicine on time. (IDI, female, 26 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Awareness of living in HIV high-risk community | After | By mere fact that most people in this community are HIV positive, it makes it easier for PrEP users take their medicine every day. An example is announcing vaccination among people to prevent against getting infected with Cholera disease. I cannot fail to get vaccinated if some people in my community are already suffering from cholera disease. I cannot hesitate to go for this vaccination. After all, I will fear getting the same disease. (IDI, male, 31 years old, fisherman, fishing village, remaining on PrEP but non-adherent) | |

| Trust that PrEP is protective against HIV | After | I realized that I had many chances of getting infected, yet there was medicine that could reduce at the risk. Hence, I decided to participate in the PrEP program. The way we live here, you know there are many women here. There are many places of having fun and you can have sex with different women. For me, I said that I cannot allow a woman to destroy my life because no woman can stay here with only one man. The reason why I stuck on this medicine, I could see many of my colleagues I grew up with taking HIV medicine. I said that we have the same behavior; if I am not yet infected, why do I not try and protect myself. (IDI, male, 28 years old, fisherman, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Support/counselling from experienced users to use/refill PrEP or to manage side effects | After | They advise you that you can do everything you want but you should not forget taking your medicine. So, my colleagues advise me to take my medicine especially when I am travelling to work somewhere far from here. (IDI, female, 28 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Drug sharing (borrowing) | After | If I am stuck, I can borrow some tablets from a colleague and I take. That is how my colleagues support me. There is a time we move far, when some of them forgot the drugs or it got finished on the way, but you use the medicine of a colleague who still has some tablets. (IDI, female, 28 years old, sex worker, fishing village, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Barriers | Fear of stigma because PrEP is mistaken for ART | Both | The difference between PrEP and ARVs is very small. They are both taken on daily basis, the providers are the same, the facilities where we pick them from are the same. It is very easy for one to say, "That person is lying that he is on PrEP. He is on ARVs." There is no way you can explain the difference. (IDI, male, 44 years old, fisherman) |

| Fear of stigma because PrEP users could be viewed as having multiple sexual partners, being promiscuous, or being a sex worker | Both | He can say that you are a sex worker. He might ask you the reason why you take that medicine if you are not infected. So, your partner might think that you are a sex worker. (FGD, females, 15–19 years old, community members, mainland) | |

| Fear that PrEP usage may increase STI prevalence | After | The problem with PrEP is that the moment you take it you are protected, but the problem you can get afterward is getting sexually transmitted diseases. (IDI, female, 39 years old, sex worker, mainland, remaining on PrEP and adherent) | |

| Negative remarks or discouragement from peers | After | Someone could take it and stop it because of people’s words. They lost interest because of statements such as: Why do you take it when you are not sick? What will you take in case you get infected? So, some people threw it away, whereas others stopped it completely. (IDI, male, 28 years old, fisherman, remaining on PrEP and adherent) |

Figure 1.

Key facilitators and barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence before and after PrEP rollout, by socio-ecological model level. Key: + facilitators; − barriers.

Interpersonal (dyadic) and household level

Facilitators for PrEP uptake and adherence at the interpersonal level mentioned consistently before and after PrEP rollout included having relationships that were perceived to entail HIV risk. Some participants perceived PrEP as an effective HIV prevention method that can be controlled by individuals who may be living with a partner they do not trust (e.g. may have other sexual partners outside their relationship, suspect dishonesty about HIV-negative status) or with whom they felt unable to negotiate safer sex (e.g., condom use with permanent/long-term partners). In addition, wishing to remain in an HIV-serodiscordant relationship and/or wanting to have a child with a HIV-positive partner – wanting to “plan for the future” – strongly motivated some to initiate and adhere to PrEP. Across priority populations, support from partners and family members was deemed important to facilitate adherence. Some believed that the health protection provided by PrEP – combating HIV fatalism and its related risky behaviors – could bolster family financial stability.

After PrEP rollout, participants identified an additional facet of relationship-support: disclosing PrEP use to a partner facilitated adherence by enabling the partner to help with reminders to take and refill PrEP. For example, one fisherman noted that after being away all day for work, “When I go back at night, [my wife] tells me to swallow my medicine.”

One barrier to PrEP use identified before rollout was the perceived adequacy of other prevention methods (i.e., condom use with high-risk partners) to avert HIV acquisition. Others were concerned that their adherence to PrEP might be hindered by sharing the prescription with their long-term partners, whether willingly or under pressure. After rollout, some reported gender-based violence due to partners’ confusion between PrEP and ART: “they [married women] were beaten by their husbands because they thought it is a pill for HIV treatment.”

Before PrEP rollout, participants were concerned about the cost of PrEP, especially when weighed against other competing financial obligations. After rollout, cost was not mentioned as a barrier to either uptake or adherence, as PrEP was offered for free. However, participants worried about high transport costs associated with picking up PrEP refills. Another barrier to PrEP uptake and adherence mentioned both before and after PrEP rollout was food insecurity, which rendered medication side effects less tolerable. Importantly, participants expressed concerns that a partner could perceive PrEP use as a sign of infidelity, having multiple sex partners, or being engaged in sex work. After PrEP rollout, partners’ objections to PrEP discouraged uptake and adherence.

Occupational level (for priority populations)

For sex workers, perceived risky situations prompting PrEP uptake and adherence were mentioned both before and after PrEP rollout, including paying partners giving financial incentives for condomless sex or forcing condomless sex, and unplanned sex work leaving no time to find and use a condom as protection.

Before PrEP rollout, sharing PrEP medications with peers was seen as a possible barrier to adherence, though after rollout, drug sharing and a supportive peer environment among sex workers and fishermen were seen as facilitators of adherence. One sex worker said, “If I am stuck, I can borrow some tablets from a colleague and [take them]. That is how my colleagues support me.”

After PrEP rollout, sex workers mentioned that PrEP use made it possible to reduce the number of daily paying partners while still making the same income, as clients paid more for condomless sex. This gave sex workers more free time, which they felt facilitated adherence to PrEP.

Some barriers to adherence were mentioned consistently before and after PrEP rollout. Fishermen, sex workers, and truck drivers are highly mobile due to their work, which could lead to missed PrEP appointments and refill pick-ups. Sex workers worried that they would lose paying customers due to stigma around PrEP use: customers could mistake PrEP for ART and believe the sex worker was HIV-positive, or they could perceive that PrEP was taken only by people at high risk of HIV and, therefore, would be a marker of high-risk behavior. Other participants worried that PrEP side effects would affect daily functions, energy, and work performance, especially important in high-intensity occupations which require vigorous physical activity and attention such as fishing, sex work, and truck driving.

After PrEP rollout, some bar girls, waitresses, and fishermen mentioned difficulties travelling to PrEP appointments due to work restrictions, which limited time off work. In addition, participants described how alcohol misuse common in sex work venues and fishing communities impaired decision-making, leading to missed appointments and refills as well as poor adherence to drug regimens.

Program level

Prior to PrEP rollout, programmatic facilitators to uptake and adherence included making PrEP easily accessible and convenient to highly mobile groups, stressing the importance of provider confidentiality, having skilled/trained PrEP health care providers, and maintaining reliable PrEP supply and storage. After PrEP rollout, several program logistics facilitated adherence: telephone reminders by health care providers, the ability to get a three-month supply of PrEP, and peers helping with PrEP refills.

Several programmatic barriers were mentioned only before PrEP rollout, such as fear of unskilled community health workers distributing PrEP, price-gouging by community distributors, inconvenient clinic hours, and long wait times. Before rollout, there was also a concern about unclear guidelines for PrEP eligibility and adherence counseling. These concerns were not mentioned after rollout. However, more structural programmatic barriers mentioned prior to rollout, such as distance from PrEP clinics and staffing or supply shortages, persisted after rollout.

Community level

Before rollout, participants described PrEP use as a potential tool for exhibiting their HIV-negative status and demonstrating its HIV prevention efficacy to their peers. However, after rollout, these facilitating factors of PrEP uptake were not mentioned.

Important facilitators for uptake and adherence mentioned consistently before and after program rollout included community trust in PrEP providers and peers who provide reminders to take and to refill PrEP.

After PrEP program rollout, knowledge of living in a high-HIV-risk community and trusting PrEP’s protective effects were deemed important to facilitate uptake. Counseling from experienced PrEP users was considered an important facilitator of adherence, particularly as they could give advice on how to manage the PrEP side effects as well as provide reminders and share/borrow drugs when needed.

However, both before and after PrEP rollout, stigmatizing associations of PrEP use with promiscuity and sex work were common obstacles to PrEP uptake and adherence. Participants worried that being seen at a PrEP clinic would implicate them in sex work, acting as a barrier to both uptake and adherence.

After rollout, other barriers to PrEP emerged. Participants worried that community members could mistake PrEP for ART and assume that PrEP clients were HIV-positive; for example, one fisherman stated, “The difference between PrEP and ART is very small. They are both taken on daily basis, the providers are the same, the facilities where we pick them from are the same.” Others raised concerns around risk compensation, including fear of an increase in other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) due to decreased condom use and increased risky sexual behaviors. Negative remarks and discouragement from peers regarding PrEP use after program rollout also hindered uptake and adherence.

DISCUSSION

Supporting earlier quantitative assessments of the RHSP PrEP pilot program, this qualitative study conducted in high-HIV-burden fishing communities and trading centers in south-central Uganda before and after PrEP rollout found that HIV-serodiscordant couples were strongly motivated to initiate and adhere to PrEP, while persons in occupations with high mobility and erratic schedules like sex workers and fishermen reported challenges to adherence. We found no indication that people discontinued PrEP because they perceived decreased risk and less need for PrEP. Rather, side effects, access-related issues (e.g. work-related travel), and stigma were the primary drivers of discontinuation.

We identified several facilitators for PrEP use. Support from partners, family members, peers, and colleagues were mentioned as important for adherence: these relationships helped with reminders, picking up refills, and sharing/borrowing/lending pills. Disclosure of PrEP use in these relationships may facilitate adherence. Similar findings have been reported among female sex workers in Kenya (33). The RHSP PrEP program provided support and counselling from experienced PrEP users, which participants particularly appreciated and perceived as the most reliable source of counselling. Similarly, adolescent girls and young women in Zimbabwe and South Africa who felt empowered to proactively discuss PrEP in their communities found that becoming a “community PrEP ambassador” improved their own ability to take PrEP and encourage others to use PrEP (34). PrEP pill sharing has been previously reported among men who have sex with men in the United States (35). In Rakai, we have previously identified ART sharing among people living with HIV, which was similarly facilitated by disclosure and often seen in professional networks (such as among sex workers) (36). As we saw with ART sharing, PrEP sharing post-rollout was perceived to improve adherence, in contrast to pre-rollout concerns that pill sharing would be a barrier to adherence. We are currently studying ART diversion in more depth in this setting (R21AI145682) and recommend future monitoring of PrEP diversion as PrEP becomes more widely available in Uganda and similar settings.

Several logistical concerns mentioned prior to PrEP rollout, by both community members and providers, were successfully addressed after program initiation, such as unclear guidelines for PrEP eligibility and counseling, unskilled volunteers distributing PrEP, price-gouging, long wait times, and limited clinic hours. Other more structural programmatic barriers remained, including distance to PrEP clinics and supply shortages. More flexible PrEP refill schedules and community-based distribution sites may resolve some of these issues. Despite accelerated rollout timelines, the RHSP PrEP program’s health education successfully established trust in PrEP’s effectiveness and heightened participants’ awareness of HIV transmission in their communities. Programs should strengthen health education efforts to build trust while conveying accurate information to potential PrEP beneficiaries.

Stigma and social harms were a salient barrier to PrEP uptake and adherence: PrEP use could signal stigmatized behaviors like infidelity, promiscuity, or sex work. Additionally, intentional or inadvertent disclosure of PrEP use was linked to adverse consequences, including gender-based violence. Such stigma was a primary driver of PrEP discontinuation. Program implementers will need to address these issues and provide support as needed. It is critical to communicate that PrEP is not only for those engaging in risky sexual behavior, but rather an effective prevention tool in communities with high HIV burdens. Community-level de-stigmatization and normalization of PrEP use could facilitate uptake and adherence.

An additional source of stigma was that the locations for PrEP refills were the same as where people living with HIV received ART, so observers could mistakenly identify PrEP users as HIV-positive, as occurred in the VOICE-C study in South Africa.(37) Moreover, PrEP pills are similar in appearance to ART. Dispensing PrEP in separate locations could mitigate these stigmatizing perceptions. Online and mobile modalities for PrEP prescriptions may also be useful (38). As suggested from other qualitative studies, rebranding with clear messaging and packaging to distinguish PrEP from ART could also cognitively clarify distinctions between PrEP and ART as a tool of destigmatization (17, 39).

Female sex workers viewed PrEP as beneficial: it prevented HIV and enabled them to have fewer clients while earning the same income since they could charge a higher price for condomless sex, although less frequent condom use could increase the risk of HIV and other STIs as well as unwanted pregnancies. Some expressed concerns that behavioral disinhibition (e.g. decreased condom use) could increase STI prevalence, as reported in other studies of PrEP users (40). Monitoring STI incidence, unwanted pregnancies, impact on women’s empowerment, risk of violence and implementing behavioral interventions as needed to manage risk compensation will be crucial in PrEP programs.

This qualitative study had several strengths. This is among the first studies to examine dynamics of PrEP usage in fishing and nearby communities. We gathered data from a large and diverse sample of participants, including persons at high risk of HIV (pre-rollout), clients at various stages of the PrEP care continuum, and service providers. We triangulated our findings by using IDIs and FGDs before and after program rollout, allowing us to assess whether potential challenges were addressed by the RHSP PrEP program or did not occur as initially hypothesized. However, a key limitation is that this qualitative work was initially designed as two separate qualitative studies with IDIs and FGDs conducted among different participants at different locations at different times, so these observations may be not be directly comparable.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we found that the RHSP PrEP program addressed many pre-rollout concerns. However, barriers remain, especially related to stigma. Centering successful PrEP users as opinion leaders in communication efforts and provision of PrEP services outside ART clinics may promote uptake and adherence by tackling fears, rumors, and stigma. The RSHP PrEP program could be strengthened by providing several delivery and refill modes to facilitate continuation among highly mobile populations such as truck drivers, sex workers, and fishermen.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our RHSP Social and Behavioral Science team who collected this qualitative data: Charles Ssekyawa, Dauda Isabirye, Aminah Nambuusi, Rosette Nakubulwa, and Ann Linda Namuddu. We appreciate Grace Mongo Bua who contributed to qualitative coding of several transcripts during data analysis. We also thank all study participants who graciously shared their time, thoughts, and experiences. We acknowledge research grant funding support from the US National Institute of Mental Health, the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the US National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center, the JHU Center for AIDS Research, The Swedish Physicians Against AIDS Research Foundation, and the Division of Intramural Research at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. We also acknowledge the United States President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) which supports the provision of pre-exposure prophylaxis to Ugandans in the study region.

Funding:

This research was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH090173, R01MH107275), the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI143333), the US National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (D43TW010557), the JHU Center for AIDS Research (P30AI094189), the Swedish Physicians Against AIDS Research Foundation, and in part by the Division of Intramural Research at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The funders played no role in data collection, interpretation, or reporting.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute, the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology), the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine eIRB, and the Western IRB.

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data and material: Available upon request to the corresponding author.

Code availability: Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heffron R, Ngure K, Mugo N, Celum C, Kurth A, Curran K, et al. Willingness of Kenyan HIV-1 serodiscordant couples to use antiretroviral-based HIV-1 prevention strategies. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2012;61(1):116–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack N, Evens EM, Tolley EE, Brelsford K, Mackenzie C, Milford C, et al. The importance of choice in the rollout of ARV-based prevention to user groups in Kenya and South Africa: a qualitative study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(3 Suppl 2):19157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Restar AJ, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, Lafort Y, Gichangi P, Masvawure TB, et al. Perspectives on HIV Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxes (PrEP and PEP) Among Female and Male Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya: Implications for Integrating Biomedical Prevention into Sexual Health Services. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(2):141–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karuga RN, Njenga SN, Mulwa R, Kilonzo N, Bahati P, O’Reilley K, et al. “How I Wish This Thing Was Initiated 100 Years Ago!” Willingness to Take Daily Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Kenya. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, Garnett GP, Dybul MR, Piot PK. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: a multinational study. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, Mugo NR, Katabira E, Bukusi EA, et al. Integrated Delivery of Antiretroviral Treatment and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to HIV-1-Serodiscordant Couples: A Prospective Implementation Study in Kenya and Uganda. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heffron R, Ngure K, Odoyo J, Bulya N, Tindimwebwa E, Hong T, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-negative persons with partners living with HIV: uptake, use, and effectiveness in an open-label demonstration project in East Africa. Gates Open Res. 2017;1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugo PM, Sanders EJ, Mutua G, van der Elst E, Anzala O, Barin B, et al. Understanding Adherence to Daily and Intermittent Regimens of Oral HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Kenya. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(5):794–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarr M, Gueye D, Mboup A, Diouf O, Bao MDB, Ndiaye AJ, et al. Uptake, retention, and outcomes in a demonstration project of pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in public health centers in Senegal. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(11):1063–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koss CA, Ayieko J, Mwangwa F, Owaraganise A, Kwarisiima D, Balzer LB, et al. Early Adopters of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Population-based Combination Prevention Study in Rural Kenya and Uganda. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018;67(12):1853–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eakle R, Gomez GB, Naicker N, Bothma R, Mbogua J, Escobar MAC, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and early antiretroviral treatment among female sex workers in South Africa: Results from a prospective observational demonstration project. PLoS Medicine. 2017;14(11):e1002444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawuma R, Ssemata AS, Bernays S, Seeley J. Women at high risk of HIV-infection in Kampala, Uganda, and their candidacy for PrEP. SSM - population health. 2021;13:100746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muwonge TR, Nsubuga R, Brown C, Nakyanzi A, Bagaya M, Bambia F, et al. Knowledge and barriers of PrEP delivery among diverse groups of potential PrEP users in Central Uganda. PloS one. 2020;15(10):e0241399–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koechlin FM, Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, O’Reilly KR, Baggaley R, Grant RM, et al. Values and Preferences on the Use of Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention Among Multiple Populations: A Systematic Review of the Literature. AIDS and behavior. 2017;21(5):1325–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi S, Tuot S, Mwai GW, Ngin C, Chhim K, Pal K, et al. Awareness and willingness to use HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in low‐and middle‐income countries: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang LW, Grabowski MK, Ssekubugu R, Nalugoda F, Kigozi G, Nantume B, et al. Heterogeneity of the HIV epidemic in agrarian, trading, and fishing communities in Rakai, Uganda: an observational epidemiological study. The lancet HIV. 2016;3(8):e388–e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubega M, Nakyaanjo N, Nansubuga S, Hiire E, Kigozi G, Nakigozi G, et al. Understanding the socio-structural context of high HIV transmission in kasensero fishing community, South Western Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mafigiri R, Matovu JKB, Makumbi FE, Ndyanabo A, Nabukalu D, Sakor M, et al. HIV prevalence and uptake of HIV/AIDS services among youths (15–24 Years) in fishing and neighboring communities of Kasensero, Rakai District, South Western Uganda. BMC public health. 2017;17(1):251-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagaayi J, Chang LW, Ssempijja V, Grabowski MK, Ssekubugu R, Nakigozi G, et al. Impact of combination HIV interventions on HIV incidence in hyperendemic fishing communities in Uganda: a prospective cohort study. The lancet HIV. 2019;6(10):e680–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagaayi J, Batte J, Nakawooya H, Kigozi B, Nakigozi G, Strömdahl S, et al. Uptake and retention on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among key and priority populations in South-Central Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2020;23(8):e25588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryman A, Burgess RG. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London, England: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skovdal M, Cornish F. Qualitative research for development: a guide for practitioners: Practical Action Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM. Qualitative methods in Public health: a field guide for applied research. Jossey-Bass, editor. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass and Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, Mayer KH, Mimiaga M, Patel R, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS (London, England). 2017;31(5):731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amico KR, Wallace M, Bekker L-G, Roux S, Atujuna M, Sebastian E, et al. Experiences with HPTN 067/ADAPT Study-Provided Open-Label PrEP Among Women in Cape Town: Facilitators and Barriers Within a Mutuality Framework. AIDS and behavior. 2017;21(5):1361–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshioka E, Giovenco D, Kuo C, Underhill K, Hoare J, Operario D. “I’m doing this test so I can benefit from PrEP”: exploring HIV testing barriers/facilitators and implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis among South African adolescents. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camlin CS, Koss CA, Getahun M, Owino L, Itiakorit H, Akatukwasa C, et al. Understanding Demand for PrEP and Early Experiences of PrEP Use Among Young Adults in Rural Kenya and Uganda: A Qualitative Study. AIDS and behavior. 2020;24(7):2149–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van der Elst EM, Mbogua J, Operario D, Mutua G, Kuo C, Mugo P, et al. High acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis but challenges in adherence and use: Qualitative insights from a phase I trial of intermittent and daily PrEP in at-risk populations in Kenya. AIDS and behavior. 2013;17(6):2162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velloza J, Khoza N, Scorgie F, Chitukuta M, Mutero P, Mutiti K, et al. The influence of HIV-related stigma on PrEP disclosure and adherence among adolescent girls and young women in HPTN 082: a qualitative study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2020;23(3):e25463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mansergh G, Mayer K, Hirshfield S, Stephenson R, Sullivan P. HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Medication Sharing Among HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex With Men. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):e2016256–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen JG, Nakyanjo N, Isabirye D, Wawer MJ, Nalugoda F, Reynolds SJ, et al. Antiretroviral treatment sharing among highly mobile Ugandan fisherfolk living with HIV: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2020;32(7):912–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Luecke E, Laborde N, Hartmann M, Montgomery ET, et al. Perspectives on use of oral and vaginal antiretrovirals for HIV prevention: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(3S2):19146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Touger R, Wood BR. A Review of Telehealth Innovations for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2019;16(1):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed N, Pike C, Bekker L-G. Scaling up pre-exposure prophylaxis in sub-Saharan Africa. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2019;32(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, Price B, Roth NJ, Willcox J, et al. Association of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis With Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Individuals at High Risk of HIV Infection. JAMA. 2019;321(14):1380–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]