Abstract

Neurocysticercosis (NC), i.e., the presence of the larval form of Taenia solium in tissues, is the most frequent and severe infection involving the central nervous system. Paired serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from patients with NC, CSF and serum samples from a control group, and serum samples from patients with other parasitoses were studied by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and by immunoblotting with Taenia crassiceps vesicular fluid antigen (Tcra) and Taenia solium total saline antigen (Tso) for the detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies. ELISAs carried out with the Tso and Tcra antigens showed 94.1 and 95.6% sensitivities, respectively, for the detection of antibodies in CSF and 70.6% and 91.2% sensitivities, respectively, for the detection of antibodies in serum, with 100% specificity for the detection of antibodies in CSF and 80% specificity for the detection of antibodies in serum for both antigens. On the basis of the reactivities of the peptides in the samples analyzed, the peptides of ≤23, 39, 85 to 77, and 97 kDa were found to be Tso specific by immunoblotting and the peptides of ≤62, 74, 109, 121, and 131 kDa were found to be Tcra specific. Tests with Tcra extract had higher sensitivities and more homogeneous results and permitted us to obtain the parasites easily. We suggest the use of Tcra ELISA for the study of serum and confirmation of the results for sera positive by an immunoblotting analysis in which specific peptides (e.g., peptides of 19 to 13 kDa) are detected.

Neurocysticercosis (NC), i.e., the presence of the larval form of Taenia solium in tissues, is the most frequent and severe infection involving the central nervous system (2, 17). Its distribution is universal, with a frequent occurrence in developing countries in Latin America, Africa, and India (1, 15, 17, 18). Cases have also been reported in the United States due to immigration of individuals from areas where NC is endemic (16).

Diagnosis of NC is based on clinical and epidemiological criteria and on laboratory methods (neuroimaging and immunological methods). Clinical diagnosis is impaired by the polymorphic and nonspecific symptoms of NC, and the detection of anticysticercus antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) represents an important diagnostic element. The detection of serum antibodies is impaired by cross-reactions with the agents of parasitoses, such as Echinococcus spp., and requires the use of purified antigens (20).

The preparation of adequate antigen extracts in sufficient amounts for the diagnosis of NC is still linked to the detection of swine naturally infected with T. solium larvae, which are usually reared under clandestine conditions and which are difficult to locate, preventing the large-scale production and use of the necessary procedures for specific antigen purification (2, 5, 6, 11, 21, 22).

It would be desirable to have an animal model that is easily maintained in the laboratory and that can be used as an alternative source of parasites, and the possibility of achieving such a model arises from the observation that the Taenia species share common antigens. The ORF strain of T. crassiceps reproduces in an asexual manner by intraperitoneal passage through female BALB/c mice, representing an important experimental model which, according to comparative studies with homologous antigens in CSF samples, can be used for the immunodiagnosis of NC (2, 5, 11, 21, 22).

The immunoblot test has been used for the study of NC, and different indices of sensitivity and specificity have been observed, depending on the antigen preparation, on the type and severity of the lesions, and on the inflammatory reaction surrounding the parasite (6–8, 13, 14, 20, 21). These discordant results should be better explored in terms of the antigenic epitopes recognized by the host at the local (CSF) and systemic (serum) levels in order to contribute to the elucidation of immunopathogenic mechanisms in the host-parasite relationship.

The objective of the present study was to identify the specific peptides in the T. crassiceps and T. solium antigen extracts by immunoblotting with serum and CSF samples from patients with NC and to evaluate the performances of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and immunoblotting with serum samples from patients in different evolutionary phases of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

A total of 68 paired serum and CSF samples from patients with NC were studied. The patients were selected according to the General NC Investigation Protocol of the Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo (approved by the Ethics Committee for the Analysis of Research Projects of the Clinical Director's Office of the Hospital [approval no. 072/97] according to Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council, Ministry of Health, Brasilia, Brazil).

On the basis of imaging examination (computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging) (12), 8.5% of the patients had normal results (type I), 11.9% presented with intact cysts (type II), 20.3% showed the presence of inflammatory signs and/or cysts in degeneration (type III), 23.7% presented with only calcified cysts (type IV), and 30.5% had cysts in more than one phase of evolution (mixed type). One (1.7%) patient showed ventricular localization, and for two (3.4%) patients we did not have imaging results.

The control group (group C) consisted of CSF samples from 10 individuals with other neurological disorders (viral or bacterial meningitis) and serum samples from 35 apparently healthy individuals. The group of samples from patients with other parasitoses (group OP) included 23 serum samples reactive by immunologic tests for toxocariasis (n = 7), toxoplasmosis (n = 6), Chagas' disease (n = 5), and schistosomiasis (n = 5).

Parasites and antigens.

Cysticerci of T. crassiceps (ORF strain) and T. solium, T. crassiceps vesicular fluid antigen (Tcra), and total saline T. solium antigen (Tso) were obtained by the method of Vaz et al. (21). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was added to the antigen extracts at a final concentration of 0.4 mM, and the preparations were stored at −70°C.

Immunoenzymatic test (ELISA).

Flat-bottom polystyrene plates were used (Costar Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.). Skim milk (5%) in saline solution containing 0.05% Tween 20 was used as a blockade for 2 h at 37°C and as the dilution buffer. Tso and Tcra (10 μg/ml each), CSF and serum (diluted 1:2 and 1:100, respectively), conjugate (peroxidase-labeled sheep anti-human immunoglobulin G [IgG; Biolab Diagnóstica SA, Jaquarepaguá, RJ, Brazil]), and chromogen substrate (ortho-phenylenediamine [1 g/liter] and H2O2 [1 ml/liter] in 0.2 M citrate buffer [pH 5.0]) at volumes of 100 μl/well were used. Incubation was carried out at 37°C for 1 h for all steps except for those with the substrate (15 min). The reaction was stopped with 0.5 N H2SO4 and was read with a plate spectrophotometer (Diagnostics Pasteur, Strasbourg-Schiltigheim, France) at 492 nm. The absorbance obtained for each test was subtracted from the blank (test with no sample). Determination of the cutoff was based on the analysis of the diagnostic efficiency according to the Youden index (24) calculated for the absorbance values of the control group (mean ± n standard deviation, with n ranging from −1.16 to +7.0).

Immunoblotting.

Tso and Tcra immunoblotting analyses were performed with 64 and 65 CSF samples and 48 and 62 serum samples, respectively, from patients with NC. All of the samples were reactive to the same antigen by ELISA. Serum and CSF samples from group C and serum samples from group OP were also assayed. For analysis of Tcra, six serum samples that were negative by ELISA were also assayed. Positive, negative, and background (with no sample) controls were included in each test.

Tso and Tcra extracts (7 μg/mm) were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 7 to 20% gel gradient (10) and were transferred electrophoretically to 0.22-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) (19), which were cut into 3 to 4-mm-wide strips. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M; pH 7.2; 0.0075 M Na2HPO4, 0.025 M NaH2PO4, and 0.14 M NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20 was used for the washes and for the preparation of skim milk. The strips were blocked for 2 h with 5% milk, and the CSF and serum samples were diluted 1:2 and 1:100, respectively, with 1% milk and were incubated for 18 h 4°C. The conjugate used was biotin-labeled goat anti-human IgG and peroxidase-labeled avidin (Cambridge Biotech Co., Mass.), with incubation for 1 h.

Antibodies that bound to Tcra were visualized with 0.017% diaminobenzidine and 5% H2O2 in PBS. The chromogen-substrate for Tso blots was 0.05% 4-chloronaphthol predissolved in methanol (1/5 of the volume) and in Tris-buffered saline (0.01 M; pH 7.4; Tris-hydroxymethylaminoethane and 0.15 M NaCl)–0.6% H2O2, which permitted a better identification of the peptides.

RESULTS

ELISA.

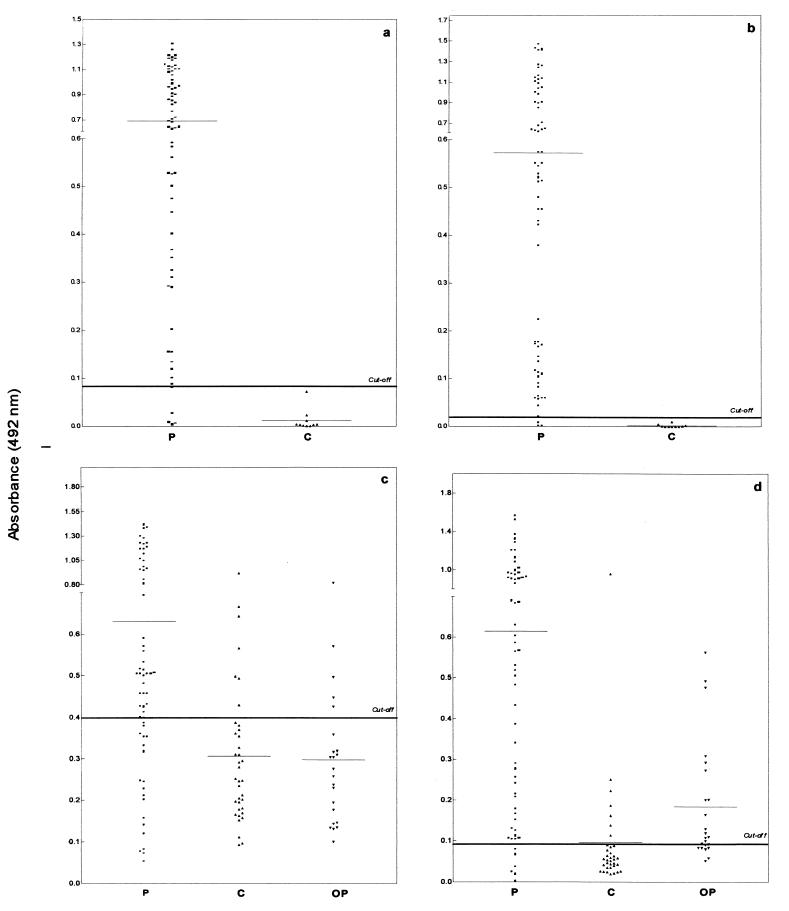

The ELISA results obtained for CSF and serum samples from patients with NC and in groups C and OP by using Tso and Tcra are presented in Fig. 1. All CSF samples in group C were nonreactive by the ELISAs with Tcra and Tso. Nine (26%) of the 35 group C serum samples were reactive by ELISA: 5 with both antigens, 2 with Tso, and 2 with Tcra. Five (22%) of the 23 group OP serum samples were reactive with both antigens, and 9 (39%) additional samples were reactive only with Tcra. The sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index are presented in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Results for CSF (a and b) and serum (c and d) samples from patients with NC (P) and for serum samples in group C and group OP obtained by ELISA with Tso (a and c) and Tcra (b and d) for the detection of IgG antibodies.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity, Specificity, 95% confidence intervals and Youden index for the ELISA for IgG antibodies in CSF and serum samples with Tso and Tcra

| Antigen | Sample (no. of samples) | Sensitivity (% [CIa]) | Sample (no. of samples) | Specificity (% [CI]) | Youden index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tso | CSF (68) | 94.1 (91.2–97.0) | CSF (10) | 100.0 (99.0–100.0) | 0.941 |

| Tso | Serum (68) | 70.6 (65.1–76.1) | Serum (35) | 80.0 (73.2–86.8) | 0.506 |

| Tcra | CSF (68) | 95.6 (93.1–98.1) | CSF (10) | 100.0 (99.0–100.0) | 0.956 |

| Tcra | Serum (68) | 91.2 (87.8–94.6) | Serum (35) | 80.0 (73.2–86.8) | 0.712 |

CI, 95% confidence interval.

For serum samples better results were obtained with Tcra than with Tso (P < 0.001), with higher sensitivity, although a low specificity (80%) was obtained with both antigens. The Tso ELISA was more efficient for the detection of antibodies in CSF than for the detection of antibodies in sera (P < 0.001). For the detection of antibodies in CSF samples, tests with Tso and Tcra had similar efficiencies (P > 0.30).

Immunoblotting.

In the Tcra immunoblotting assay, 64 (98.5%) CSF samples and 61 (98.0%) serum samples were reactive. In the Tso immunoblotting assay, 62 (96.9%) CSF samples and all serum samples from patients with NC were reactive.

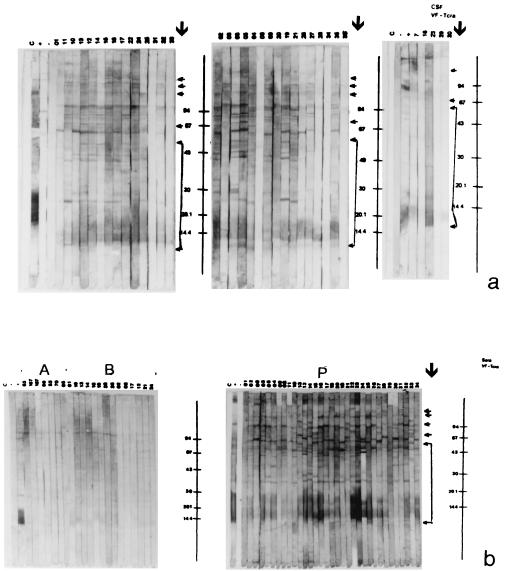

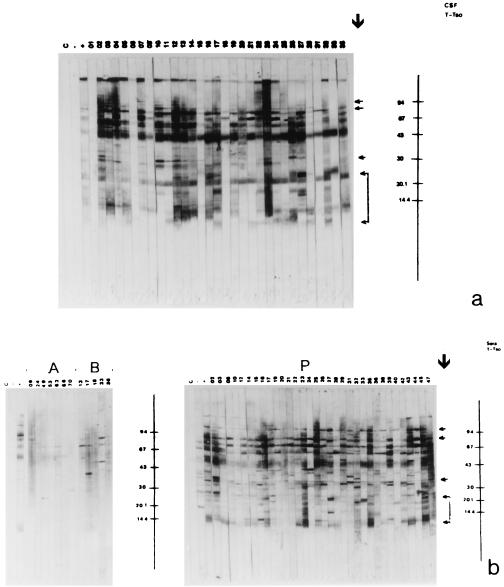

Figures 2 and 3 show the blots obtained with Tcra and Tso, respectively, and Table 2 presents the peptides that were reactive in the blot with the samples from patients with NC and in groups C and OP.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot of CSF (a) and serum (b, section P) samples from patients with NC , for serum samples in group C (b, section A), and for serum samples in group OP (b, section B) with Tcra. Lane C, control without a sample; lane −, negative control; lane +, positive control; section P, patient group; section A, group C; section B, group OP. Molecular mass standards are given on the right (in kilodaltons). Arrows indicate peptides that are specific for and confirmatory of NC.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of CSF (a) and serum (b, section P) samples from patients with NC, for serum samples in group C (b, section A), and for serum samples in group OP (b, section B) with Tso. Lane C, control without a sample; lane −, negative control; lane +, positive control; section P, patient group; section A, control group C; section B, group OP. Molecular mass standards as given on the right (in kilodaltons). Arrows indicate peptides that are specific for and confirmatory of NC.

TABLE 2.

Peptides in immunoblots of serum and CSF samples from patients with NC and sera in group C and group OP reacting with Tso and Tcra

| Antigen | Group | Peptide mass (kDa)a |

|---|---|---|

| Tso | NC | 11–9, 14–12, 16, 17, 19, 23–21, 24, 26, 30, 31, 34, 37, 39, 43, 50–46, 53, 57, 60, 64, 67, 75–68, 85–77, 86, 89, 97, 101, 112, 120, 131, 150 |

| C | 24, 31, 37, 43, 50–46, 64, 75–68, 86, 89, 101, 112 | |

| OP | 31, 37, 43, 64, 50–46, 75–68, 86, 89, 101 | |

| Tcra | NC | 12, 19–13, 22, 25, 28, 30, 35, 39, 41, 47, 55, 62, 65, 74, 82, 87, 96, 109, 121, 129, 131, 146 |

| C | 65, 82, 87, 96, 129 | |

| OP | 65, 82, 87, 96, 129, 146 |

Underscores indicate specific peptides confirmatory for NC.

The 10 CSF samples in group C were not reactive in the Tso or Tcra blot. Of the 35 serum samples in group C, only 7 (20%) were not reactive in the Tcra blot, while all samples were reactive with at least one nonspecific peptide in the Tso blot. The 23 serum samples in group OP were reactive with at least one nonspecific peptide in the Tso and Tcra blots. Peptides were considered to be specific when they reacted with CSF and/or serum in group NC and to be nonspecific when they reacted with serum samples in groups C and/or OP (Table 2).

In the Tcra blot, the immunodominant peptides that did not react with serum samples in groups C and OP were as follows: for CSF, peptides of 19 to 13 kDa (94%), 25 kDa (51%), 41 kDa (40%), 121 kDa (38%), 109 kDa (37%), and 74 kDa (37%), and for serum, peptides of 19 to 13 kDa (84%), 25 kDa (61%), 109 kDa (56%), 41 kDa (55%), 47 kDa (47%), and 55 kDa (37%).

The most frequent specific peptides in the Tso blot were those of 85 to 77 kDa (67%), 23 to 21 kDa (66%), 97 kDa (64%), 14 to 12 kDa (55%), 57 kDa (45%), 60 kDa (44%), and 30 kDa (41%) for CSF and 85 to 77 kDa (98%), 34 kDa (85%), 14 to 12 kDa (75%), 60 kDa (62%), 97 kDa (60%), 26 kDa (54%), and 23 to 21 kDa (44%) for serum.

DISCUSSION

The objective of the present investigation was to study serum samples, which can be obtained in a less invasive manner than that required for retrieval of CSF, for the diagnosis of NC and for seroepidemiological studies for the mapping of areas of Brazil where NC is endemic. Thus, for the validation of the serologic tests developed in the present study, we used as a reference the results obtained with paired CSF samples from patients with NC.

The host-parasite biological interactions involved in NC are complex in view of the different stages of parasite evolution and of the individual variations that interfere with the host response (16), justifying the importance of the study of immunodiagnostic tests with patients with different evolutionary stages of the disease. In addition, adequate antigen extracts are difficult to obtain in sufficient amounts for immunologic tests because of the need to obtain swine naturally infected with T. solium larvae. Furthermore, the removal of individual cysticerci from infected tissues is cumbersome and time-consuming.

The major advantages of the use of the heterologous antigen Tcra are the unlimited source of cysticerci, the minimal cost of the antigen due to its production in the laboratory, and the easier extraction of the antigen from the parasites. The tests with the Tcra have shown good reproducibilities with different lots of antigen, as evaluated by the peptide pattern by SDS-PAGE and by the results for the positive and negative controls used in each assay.

The search for IgG antibodies in CSF samples by ELISA has revealed sensitivities of 94.1 and 95.6% for Tso and Tcra, respectively, and 100.0% specificity for both antigens, with no significant difference (P > 0.30). Similar results were reported by other investigators who used Tcra (6, 11).

The ELISAs used to search for serum antibodies to Tso and Tcra showed sensitivities of 70.6 and 91.2% (P < 0.001), respectively, and specificities of 80.0% for both antigens (Table 1). These differences can be explained by the different evolutionary phases of NC and by the high incidence of organisms that cause other parasitoses and that cross-react with T. solium. In a study with serum, Espinoza et al. (3) obtained better results, i.e., 80% sensitivity and 96% specificity with antigen B and 85% sensitivity and 100% specificity with the crude antigen of T. solium. The loss of the antigenic components of vesicular fluid in the preparation of Tso may have led to these discordant results due to the lower sensitivity of our crude antigen. Using vesicular fluid of T. crassiceps and T. solium by ELISA, Kunz et al. (9) detected antibodies in the 14 serum samples analyzed and reported a higher-intensity reading with the T. solium antigen, as was also observed in the present study (Fig. 1). Gottstein et al. (7) observed a lower specificity (49%) in an ELISA with total T. solium antigen, with cross-reactivity with sera from patients with intestinal parasitoses, which have high rates of occurrence in Brazil. Although the specificities observed here with Tso and Tcra were higher, there was a 20% rate of false-positive results which may have been due to these other infections.

Of the 6 serum samples from patients with NC that were negative by the Tcra ELISA, 4 were from patients who presented with calcifications in the imaging examinations, whereas for Tso, 8 of the 20 negative samples had calcifications, and 5 were from patients with intact cysts or normal imaging examinations. These data show a higher sensitivity of Tcra for the detection of antibodies in the sera of patients who did not present with signs of an inflammatory process and even in those who were in the calcification phase. In contrast, some investigators have reported the lower sensitivities of immunologic tests with both CSF and serum during the calcification phase due to the lower antibody concentration, regardless of the antigen used (9, 13, 23).

The lower sensitivity of the ELISA with Tso for the detection of antibodies in serum compared to the sensitivity for the detection of antibodies in CSF may have been due to compartmentalization of the infection and to intrathecal synthesis of antibodies in response to the parasite (4), as well as to the presence of different serum components that might interfere with and/or block the reactivity with specific antigens and that are absent from CSF. The purification of specific peptides and their use at appropriate concentrations should improve the efficiency of the test but would require large volumes of antigen (20), a procedure that would be more feasible only with the Tcra model.

The presence of one or more peptides of ≤23, 39, 85 to 77, and 97 kDa in the blot was Tso specific and confirmed NC. We observed reactivity with one or more of these peptides with all 48 ELISA-reactive serum samples. Of the 64 ELISA-reactive CSF samples analyzed, 2 were not reactive by immunoblotting and, coincidentally, were those that had absorbances close to the cutoff for the ELISA, and these two patients had normal imaging examinations or intact cysts. Another CSF sample was reactive by immunoblotting only with the 50- to 46-kDa peptide, which was also reactive with CSF samples from patients with NC (94%), serum samples from patients with NC (69%), and samples in groups C (71%) and OP (70%). This patient was in the calcification phase, and his CSF was also reactive in the Tcra blot (reactive with the 19- to 13-kDa peptide). The detection of antibodies in CSF always seems to be specific unless immunoglobulins cross the blood-brain barrier. The peptide of 50 to 46 kDa may show cross-reactivity in serum, but it may also be present in the cysticercus.

For serum samples tested by immunoblotting with Tso, Grogl et al. (8) suggested that peptides of 64, 53, and 32 to 30 kDa are of those that should be chosen for use in the development of immunologic tests, while Gottstein et al. (7) showed that the 26-kDa and/or 8-kDa fractions of T. solium were specific. Tsang et al. (20), using purified antigen of T. solium cysticerci, reported that glycoprotein bands of 50, 42 to 39, 24, 21, 18, 14, and 13 kDa confirmed the diagnosis of NC.

Michault et al. (13) demonstrated that only serum samples from patients with NC in the active phase reacted with the 14-kDa band. Our results confirm the specificity of this peptide in Tso, but we observed no association with the evolutionary phase of NC, with the peptide being reactive with 50% of the sera from patients with degenerating cysts and 43% of the sera from patients with calcified cysts.

For Tcra, we may consider the presence of at least one of the peptides of ≤62, 74, 109, 121, and 131 kDa to be specific and confirmatory for NC. Of the 65 ELISA-reactive CSF samples from patients with NC, only 1 was negative by immunoblotting. This sample had an absorbance close to the cutoff for the ELISA, and the patient presented with intact cysts with no inflammatory response. Of the 62 ELISA-reactive serum samples tested, 1 was reactive only with peptides that reacted with samples in group C (146- and 96-kDa peptides) and group OP (96- and 65-kDa peptides). The 96-kDa peptide was reactive with 82% of the serum and CSF samples from patients with NC and the sera in groups C (46%) and OP (35%). The 65-kDa peptide, which was present in 87% of the sera from patients with NC, was recognized by the sera in groups C (37%) and OP (56%). It is possible that the 96- and 65-kDa peptides detected here are absolutely nonspecific in view of the similar frequencies at which they appeared in all groups. On the other hand, the 146-kDa peptide, which was present in 35% of the serum samples from patients with NC, was observed only in samples in group OP (22%) and seemed to be more cross-reactive than nonspecific.

There are few reports of the use of immunoblotting with Tcra only with CSF for the detection of NC. In 1995, Garcia et al. (6), by immunoblotting CSF samples from patients with NC using vesicular fluid antigen of T. crassiceps and considering the 110- to 45-kDa peptides to be specific, reported that the assay had 93% sensitivity and 98% specificity. Recently, Vaz et al. (21), in a study of CSF, observed the immunodominance of the 72- to 68-, 95- to 92-, and several >100-kDa peptides of vesicular fluid antigen of T. crassiceps without detecting peptides of <20 kDa, possibly due to methodologic differences, as pointed out by Tsang et al. (20).

The results obtained with Tso and Tcra in our tests support the idea that the parasites share important epitopes and are present at concentrations sufficient for use in the immunodiagnosis of NC, except with serum, for which Tcra had a significant advantage (P < 0.001).

We suggest that ELISA with Tcra can be applied to serum samples for the screening of NC (91.2% sensitivity), especially for patients with calcifications and reduced immunoinflammatory responses. We believe that Tcra, although heterologous, has these advantages because it is rich in vesicular fluid components, which include soluble secretion and excretion antigens. These antigens are also present in T. solium cysticerci but at lower concentrations compared to those in the membrane and scolex components due to the rupture of vesicles during the process of parasite removal from swine tissue. Thus, for cysticerci of T. solium, the use of antigen purification procedures should be necessary (20).

Although no significant difference (P > 0.10) was observed between ELISA and immunoblotting, it is necessary to use Tcra immunoblotting for the confirmation of the results for sera that are reactive by ELISA. The purification of immunodominant peptides in Tcra (e.g., 19- to 13-kDa peptides) and its use at adequate concentrations in ELISA may facilitate seroepidemiologic studies with humans and swine, at reduced cost, for the evaluation of the real situation of the taeniasis-cysticercosis situation in Brazil.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by FAPESP (grant 96-7679-1) and by a CAPES fellowship (to Ednéia Casagranda Bueno).

We are indebted to Aluízio B. B. Machado, Antônio Walter Ferreira, and Hermínia Y. Kanamura for providing some samples, to Biolab-Meuriex for providing the conjugate used in the ELISA, to Vitória Bartoly for help with CSF collection, and to Paulo M. Nakamura and Rute K. C. Chang for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agapejev S. Epidemiology of neurocysticercosis in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1996;38:207–216. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651996000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade A P, Vaz A J, Nakamura P M, Palou V S E B, Cunha R A F, Ferreira A W. Immunoperoxidase for the detection of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid in neurocysticercosis: use of Cysticercus cellulosae and Cysticercus longicollis particles fixed on microscopy slides. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1996;38:259–263. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651996000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espinoza B, Palacios G R, Tovar A, Sandoval M A, Plancarte A, Flisser A. Characterization by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of the humoral immune response in patients with neurocysticercosis and its application in immunodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:536–541. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.4.536-541.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estanol B, Guárez H, Irigoyen M C, González-Barranco D, Corona T. Humoral immune response in patients with cerebral parenchymal cysticercosis treated with praziquantel. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1989;52:254–257. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira A P, Vaz A J, Nakamura P M, Sasaki A T, Ferreira A W, Livramento J A. Hemagglutination test for the diagnosis of human neurocysticercosis: development of a stable reagent using homologous and heterologous antigens. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1997;39:29–33. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651997000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia E, Ordonez G, Sotelo J. Antigens from Taenia crassiceps used in complement fixation, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and Western blot (immunoblot) for diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3324–3325. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3324-3325.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottstein B, Zini D, Schantz P M. Species-specific immunodiagnosis of Taenia solium cystecercosis by ELISA and immunoblotting. Trop Med Parasitol. 1987;38:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grogl M, Estrada J J, MacDonald G, Kuhn R E. Antigen-antibody analysis in neurocysticercosis. J Parasitol. 1985;71:433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunz J, Kalinna B, Watschke V, Geyer E. Taenia crassiceps metacestode vesicular fluid antigens shared with the Taenia solium larval stage and reactive with serum antibodies from patients with neurocysticercosis. Zentbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektkrankh Hyg Abt 1 Orig. 1989;271:510–520. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(89)80113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larralde C, Sotelo J, Montoya R M, Palencia G, Padilla A, Govezensky T, Diaz M L, Sciutto E. Immunodiagnosis of human cysticercosis in cerebrospinal fluid. Antigens from murine Taenia crassiceps cysticerci effectively substitute those from porcine Taenia solium. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:926–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machado L R, Nobrega J P S, Barros N G, Livramento J A, Bacheschi L A, Spina-França A. Computed tomography in neurocysticercosis. A 10-year long evolution analysis of 100 patients with an appraisal of a new classification. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 1990;48:414–418. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1990000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michault A, Rivière B, Fressy P, Laporte J P, Bertil G, Mignard C. Apport de l'enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay au diagnostic de la neurocysticercose humaine. Pathol Biol. 1990;38:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michel P, Michault A, Gruel J C, Coulanges P. Le serodiagnostic de la cysticercose par ELISA et Western blot. Son intérêt et ses limites à Madagascar. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1990;57:115–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarti E, Flisser A, Schantz P M, Gleizer M, Loya M, Plancarte A, Avila G, Allan J, Craig P, Bronfaman M, Wijeyaratne P. Development and evaluation of a health education intervention against Taenia solium in a rural community in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:127–132. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schantz P M, Moore A C, Munöz J L, Hartman B J, Schaefer J A, Aron A M, Persuad D, Sarti E, Wilson M, Flisser A. Neurocysticercosis in an Orthodox Jewish community in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:692–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shasha W, Pammenter M D. Sero-epidemiological studies of cysticercosis in school children from two rural areas of Transkei, South Africa. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1991;85:349–355. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1991.11812573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh G. Neurocysticercosos in South-Central America and the Indian subcontinent. A comparative evaluation. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1997;55(Suppl. 3-A):349–356. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1997000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsang V C W, Brand J A, Boyer A E. An enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay and glycoprotein antigens for diagnosing human cysticercosis (Taenia solim) J Infect Dis. 1989;159:50–59. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaz A J, Nunes C M, Piazza R M F, Livramento J A, Silva M V, Nakamura P M, Ferreira A W. Immunoblot with cerebrospinal fluid from patients with neurocysticercosis using antigen from cysticerci of Taenia solium and Taenia crassiceps. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:354–357. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaz A J, Nakamura P M, Barreto C C, Ferreira A W, Livramento J A, Machado A B B. Immunodiagnosis of human neurocysticercosis: use of heterologous antigenic particles (Cysticercus longicollis) in indirect immunofluorescence test. Serodiagn Immunother Infect Dis. 1997;8:157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson M, Bryan R T, Fried J A, Ware D A, Schantz P M, Pilcher J B, Tsang V C W. Clinical evaluation of the cysticercosis enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot in patients with neurocysticercosis. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:1007–1009. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youden D. Index for rating diagnostic test. Cancer. 1950;3:32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]