Abstract

Background

Tobacco use is highly prevalent amongst people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and has a substantial impact on morbidity and mortality.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions to motivate and assist tobacco use cessation for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), and to evaluate the risks of any harms associated with those interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO in June 2015. We also searched EThOS, ProQuest, four clinical trial registries, reference lists of articles, and searched for conference abstracts using Web of Science and handsearched speciality conference databases.

Selection criteria

Controlled trials of behavioural or pharmacological interventions for tobacco cessation for PLWHA.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted all data using a standardised electronic data collection form. They extracted data on the nature of the intervention, participants, and proportion achieving abstinence and they contacted study authors to obtain missing information. We collected data on long‐term (greater than or equal to six months) and short‐term (less than six months) outcomes. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis and estimated the pooled effects using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method. Two authors independently assessed and reported the risk of bias according to prespecified criteria.

Main results

We identified 14 studies relevant to this review, of which we included 12 in a meta‐analysis (n = 2087). All studies provided an intervention combining behavioural support and pharmacotherapy, and in most studies this was compared to a less intensive control, typically comprising a brief behavioural intervention plus pharmacotherapy.

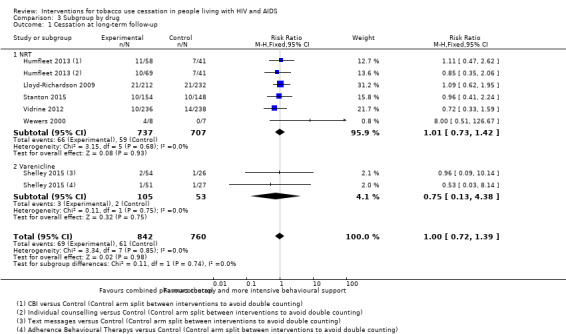

There was moderate quality evidence from six studies for the long‐term abstinence outcome, which showed no evidence of effect for more intense cessation interventions: (risk ratio (RR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.39) with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The pooled long‐term abstinence was 8% in both intervention and control conditions. There was very low quality evidence from 11 studies that more intense tobacco cessation interventions were effective in achieving short‐term abstinence (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.00); there was moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 42%). Abstinence in the control group at short‐term follow‐up was 8% (n = 67/848) and in the intervention group was 13% (n = 118/937). The effect of tailoring the intervention for PLWHA was unclear. We further investigated the effect of intensity of behavioural intervention via number of sessions and total duration of contact. We failed to detect evidence of a difference in effect according to either measure of intensity, although there were few studies in each subgroup. It was not possible to perform the planned analysis of adverse events or HIV outcomes since these were not reported in more than one study.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate quality evidence that combined tobacco cessation interventions provide similar outcomes to controls in PLWHA in the long‐term. There is very low quality evidence that combined tobacco cessation interventions were effective in helping PLWHA achieve short‐term abstinence. Despite this, tobacco cessation interventions should be offered to PLWHA, since even non‐sustained periods of abstinence have proven benefits. Further large, well designed studies of cessation interventions for PLWHA are needed.

Plain language summary

Interventions to help people living with HIV and AIDS to stop using tobacco

Background: Tobacco use is common amongst people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA); it causes a range of health problems and accounts for many deaths. There is good evidence about interventions to help people quit tobacco use in the general population, however the effectiveness in PLWHA was not known.

Methods: We reviewed the available evidence from trials to help PLWHA stop using tobacco. This evidence is correct up to June 2015. We conducted analyses of whether people were able to successfully quit tobacco use in the long‐term (six months and over) and short‐term (measured at less than six months).

Results: We found 14 relevant studies including over 2000 participants. All studies, except one, were conducted in the United States (US). All studies compared a behavioural intervention with medication, to a control group. The behavioural intervention was delivered via a range of methods including face‐to‐face, telephones, computers, and text messages. Nicotine replacement therapy or varenicline (medications that help tobacco users quit) was also given. Control participants typically received a less intensive, brief behavioural intervention, and the same medication as the intervention group. Six studies of moderate quality evidence investigated long‐term abstinence; they did not show clear evidence of benefit of the more intense intervention. Eleven studies of very low quality evidence investigated short‐term abstinence. The evidence suggested that a more intense intervention combining behavioural support and medication might help people to quit in the short‐term.

Quality of the evidence: The quality of the evidence was judged to be moderate for the long‐term abstinence outcome and very low for the short‐term abstinence outcome, and so further research is needed to increase our confidence in our findings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Tobacco use cessation in people living with HIV and AIDS.

| Tobacco use cessation in people living with HIV and AIDS | ||||||

| Patient or population: consumers of tobacco living with HIV and AIDS Setting: All included studies conducted in USA Intervention: combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural support for smoking cessation Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with combined cessation intervention | |||||

| Proportion of participants abstinent ‐ long‐term (> 6 months) assessed via self report +/‐ biochemical verification | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.72 to 1.39) | 1602 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 80 per 1000 | 80 per 1000 (58 to 112) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 63 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 (46 to 88) | |||||

| Proportion of participants abstinent ‐ short‐term (> 4 weeks to < 6 months) assessed via self report +/‐ biochemical verification | Study population | RR 1.51 (1.15 to 2.00) | 1785 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 3 | ||

| 79 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (91 to 158) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 65 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (75 to 130) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded due to risk of bias. One study had high risk of reporting bias (although impact on results mitigated by obtaining unpublished data from study authors). Allocation concealment and blinding poorly described. 2 Downgraded due to suspected publication bias indicated by asymmetrical funnel plot. 3 Downgraded due to inconsistency. The direction of effect was not always consistent and moderate heterogeneity was present (I2 = 42%).

Background

The introduction of combination anti‐retroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV into a chronic disease (Deeks 2013), comparable to other long‐term conditions such as diabetes (Nakagawa 2012). Once diagnosed, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) can have a near normal life expectancy (Nakagawa 2012). Causes of morbidity and mortality have changed; between 50% and 84% of deaths in PLWHA are now not AIDS‐related (Ehren 2014; May 2013; Weber 2013), and rates of opportunistic infections have declined substantially over the past two decades (Buchacz 2010). Non‐communicable diseases, particularly ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer, now represent a growing burden of disease in this population (May 2013).

The prevalence of tobacco consumption in PLWHA is substantial, and greater than that of the general population: between 47% and 65% of PLWHA smoke cigarettes (Friis‐Møller 2003; Helleberg 2013; Miguez‐Burbano 2005). Prevalence of tobacco use varies between countries, but there is evidence that PLWHA consume more tobacco than the general population in a range of contexts, from Zimbabwe to the United States (US) (Gritz 2004; Munyati 2006). Where ART is accessible, smoking results in greater loss of life years than the HIV infection itself in PLWHA who smoke (Helleberg 2013). In light of the high prevalence of smoking in combination with the changing trends in morbidity and mortality, smoking cessation has become highly relevant for this population.

Description of the condition

Tobacco may affect the immune system of PLWHA, resulting in increased viral replication in macrophages, microglial, and T cells (Abbud 1995, Valiathan 2014). Valiathan and colleagues demonstrated that PLWHA who smoked had higher levels of immune exhaustion and impaired T cell functioning compared to both PLWHA non‐smokers and HIV‐negative smokers (Valiathan 2014).

Untreated HIV destroys CD4 cells (T4 lymphocytes expressing CD4 proteins), which play a central role in the immune system (Naif 2013; Simon 2006). In untreated HIV infection the 'CD4 count' (number of CD4 cells) gradually falls, increasing the risk of opportunistic infections and other complications (Naif 2013; Simon 2006). Treatment with ART aims to increase the CD4 count and to achieve viral suppression ‐ to reduce the amount of HIV virus in the blood (the ‘viral load’) to an undetectable level.

Smoking tobacco may affect the immune response to ART. Some evidence indicates that tobacco use might be associated with poorer ART outcomes including a lower likelihood of achieving viral suppression, and a higher likelihood of immunological failure (when CD4 count falls below the lowest point it had been prior to ART initiation) (Feldman 2006). However, cohort study data showed no difference in CD4 and viral load between smokers and non‐smokers (Helleberg 2015).

Tobacco use causes substantial morbidity and mortality in PLWHA. The tobacco‐related harm is substantially higher in PLWHA than smokers in the general population. Smoking was found to be attributable for 24.3% of all‐cause mortality, 25.3% of major cardiovascular disease, 30.6% of non‐AIDS‐related cancer, and 25.4% of bacterial pneumonia amongst people living with HIV (Lifson 2010). This is partly due to a higher prevalence of tobacco use in PLWHA than the general population and partly due to their increased susceptibility to the impact of tobacco compared to other smokers. Lung cancer is the commonest non‐AIDS‐related cancer amongst PLWHA (May 2013), and compared to the general population, lung cancer occurs at a younger age and after shorter exposure to cigarettes (Winstone 2013). HIV has been identified as an independent factor for greater lung cancer risk (Sigel 2012). In addition, smoking is associated with increased incidence of a number of other cancers in PLWHA, including cancer of the anus and mouth (Bertisch 2013; Clifford 2005). Cardiovascular disease risk may be elevated in PLWHA, due to a combination of HIV viraemia, a pro‐inflammatory state, and the association of some ART regimens with high cholesterol and impaired glucose tolerance (Friis‐Møller 2003; Palella 2011). Tobacco use further increases cardiovascular risk, and cessation was found to be effective in significantly reducing this risk (Petoumenos 2011). Case‐control studies show that the impact of smoking on acute coronary syndrome is nearly doubled for PLWHA who smoked compared to HIV‐negative controls (Calvo‐Sánchez 2013).

Amongst PLWHA who consume tobacco, incidence of oral lesions such as oral candidiasis and oral hairy leukoplakia are increased compared to non‐users (Sroussi 2007). Current smokers are at significantly higher risk of bacterial pneumonia than non‐smokers (Gordin 2008). The outcome of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be worse in PLWHA compared to HIV‐negative people (Morris 2011). Smoking tobacco during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes for PLWHA, including small for gestational age, low birth weight and preterm birth (Aliyu 2013).

PLWHA who use tobacco are different from other tobacco users in several respects, which justifies a focused evidence review for smoking cessation in this population. PLWHA have been shown to have higher nicotine dependency levels than the general population and there is an increased prevalence of other co‐dependencies, such as alcohol and illicit drugs (Benard 2007). This makes them more vulnerable to withdrawal symptoms on stopping tobacco use, and means sustained abstinence could be difficult to achieve. The prevalence of mental illness, particularly depression, in PLWHA is higher than that in the general population (Nurutdinova 2012; Schadé 2013), and is associated with a lower likelihood of quitting smoking and an increased likelihood of relapse after quitting (Weinberger 2012). Tobacco use was reported as a coping mechanism for general HIV‐related symptoms and specifically for HIV‐related neuropathy, depression, anxiety, and ART‐associated lipodystrophy (Grover 2013; Reynolds 2004; Shuter 2012a). Despite the good prognosis of HIV, some PLWHA report fatalistic ideas and a pessimistic perception of their life expectancy, affecting their perceived susceptibility‐associated risks of tobacco; one participant said: “If I live long enough to get cancer that's great!” (Reynolds 2004).

Socioeconomic factors also have a substantial impact on tobacco use. Many PLWHA who use tobacco are members of one or more marginalised groups, including ethnic minorities, migrants, and men who have sex with men. Tobacco use was found to be consistently higher in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults, compared to heterosexual adults in a range of countries (Marshal 2008), and they are also at higher risk of HIV. Additionally, in one study of PLWHA who use tobacco, two‐thirds were found to be unemployed, almost half had an income under USD 10,000 per annum and more than one‐third were in inadequate housing (Humfleet 2009). These factors may contribute to their continued tobacco use and reduce the likelihood of success in quitting. Social support networks are lacking for many PLWHA. In addition, some PLWHA who smoke, report that more than 40% of people in their social network are smokers, reinforcing their continued smoking (Humfleet 2009).

Description of the intervention

In the general population, combined pharmacotherapy and counselling interventions are effective in achieving tobacco cessation (Stead 2016). PLWHA who are engaged in care, come into frequent contact with health professionals for regular tests and clinic appointments. This presents an opportunity to discuss and support cessation, but currently this opportunity is underutilised. HIV clinicians report a lack of confidence in initiating cessation therapies and insufficient time, despite recognising the importance (Horvath 2012; Shuter 2012b). Despite previous unsuccessful attempts to quit by over 80% of PLWHA who smoke (Shuter 2012a), a high proportion remain motivated to quit (Benard 2007; Shuter 2012a). The high prevalence of smoking, despite a substantial proportion expressing a desire to quit, reflects an unmet need for effective tobacco cessation interventions in PLWHA. There is need for clarity in how best to support PLWHA in tobacco cessation.

Tobacco cessation interventions may be brief advice, behavioural, pharmacological, or a combination. Behavioural support interventions may include group or individual counselling, consisting of appointments following the quit attempt where the smokers receive information, advice, and encouragement. Pharmacological interventions may include use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) via a range of modalities, as well as bupropion or varenicline. The literature on tobacco cessation suggests that individual pharmacotherapies are effective for tobacco cessation; however, these in combination with behavioural support are found to be more effective in the general population (Stead 2016). There is evidence of effectiveness of these tobacco cessation interventions in the general population (Stead 2012; Stead 2016), but to our knowledge, there has not been an in‐depth systematic review into their effectiveness in PLWHA.

Why it is important to do this review

Tobacco use is highly prevalent and responsible for substantial morbidity and mortality amongst PLWHA (Helleberg 2013). It is therefore, important that health workers have the best available evidence to support PLWHA in their attempts to quit tobacco. A dedicated review of cessation interventions in PLWHA is justified as a number of relevant attributes of tobacco users with HIV/AIDS differ from those of other tobacco users. Furthermore, despite motivation to quit, PLWHA often find it difficult to achieve sustained abstinence.

Objectives

Primary objective:

To assess the effectiveness of interventions to motivate and assist tobacco use cessation for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), and to evaluate the risks of any harms associated with those interventions.

Secondary objectives:

To assess whether interventions combining pharmacotherapy and behavioural support are more effective than either type of support alone in PLWHA.

To assess whether in PLWHA, tobacco cessation or cessation induction interventions tailored to PLWHA are more effective than ‘usual care’ non‐tailored cessation interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials (cluster‐RCTs).

Quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Other non‐randomised controlled trials.

We did not exclude studies on the basis of language or publication status.

Types of participants

We included trials of adults over 18 years who were HIV‐positive. We included studies of all stages of HIV infection, and studies of men only, women only, and all genders.

Trial participants were consumers of tobacco. Had we located studies which differentiated between different types of tobacco users, we would have considered subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

We included interventions that targeted individuals. The interventions included behavioural and pharmacological elements. We did not locate any studies of cessation induction trials (typically brief advice by health professionals) that aimed to encourage future quit attempts by those tobacco users who were unwilling to give up at the time of recruitment.

We included interventions delivered via any format including telephone call, the Internet, and face‐to‐face. There was no restriction on the identity of the provider which included nurses, counsellors, and peers.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure is tobacco abstinence at a minimum of six months after the start of the intervention, referred to as long‐term cessation. We did include trials with a shorter follow‐up, but these did not contribute to the primary analysis. We recognise that measurement of cessation at six months or longer is optimal (West 2005); however we included a shorter‐term outcome measure due to the relative paucity of research in the area of tobacco cessation for PLWHA. We assessed short‐term abstinence as a secondary outcome measure and completed separate analyses for the short‐ and long‐term follow‐up periods.

We used the strictest definition of abstinence reported in the study, using sustained abstinence rates in preference to point prevalence, or floating prolonged abstinence. Definitions of sustained abstinence may allow for a small number of cigarettes during the period (West 2005). We preferred, but did not require, that abstinence was biochemically verified (for example, by exhaled carbon monoxide or serum, salivary, or urinary cotinine). We treated those participants lost to follow‐up as continuing users of tobacco. These outcome measures are guided by the Russell Standards for smoking cessation trials (West 2005).

Secondary outcomes

We assessed short‐term abstinence as a secondary outcome measure. We required that the assessment point was at least four weeks, but less than six months, from the target quit date, or start of the intervention for studies of cessation induction.

In addition to short‐term abstinence, we planned to look for data on the following secondary outcome measures: HIV viral load, CD4 count, and the incidence of opportunistic infections. We planned to extract data on and report any adverse effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Tobacco Addiction Group's Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register using terms related to the topic of HIV/AIDS, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) combining topic‐related and smoking cessation terms. We also searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO, combining HIV topic terms with the smoking‐related terms and study design limits, as used for the Specialised Register. The MEDLINE search terms are included in Appendix 1. All searches were carried out on the 17th June 2015. Not other time period limitations were used.

Searching other resources

We searched the grey literature as follows: theses and dissertations via EThOS and ProQuest. We looked for conference abstracts by searching the Conference Proceedings database in Web of Science and by handsearching the databases of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, International AIDS Conference, and British HIV Association. We reviewed reference lists of literature reviews and consulted experts via email.

We searched for clinical trials via the US National Institutes of Health registry at www.clinicaltrials.gov, the World Health Organization (WHO) trials registry platform at apps.who.int/trialsearch/, the European Union (EU) clinical trials register at www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu, and the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry at www.pactr.org. For unpublished trials identified via the registries, we attempted to contact authors and requested data for analysis.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (EP reviewed all studies, RL and KS each reviewed a proportion) independently checked the title and abstracts of all retrieved records for relevance. Two authors (from EP, KS, and RL) then each reviewed the full‐text reports of all studies not excluded based on title or abstract, and which were potentially eligible for inclusion. We resolved any disagreements regarding study inclusion through discussion with a third party (OD). We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009), and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (from EP, OD, and RL) extracted data using a standardised electronic data collection form. We then entered data into Review Manager 5 computer software for preparing Cochrane systematic reviews (RevMan 2014).

We extracted the following information, where available, for each study, in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Methods: Study name (if applicable), study recruitment period, country, number of study centres, study setting, study recruitment procedure, study design.

Participants: N (intervention/control), definition of smoker used, specific demographic characteristics (e.g. mean age, age range, gender, ethnicity, sexuality), mean cigarettes per day, mean Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score, relevant inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: Description of intervention(s) (treatment, dosage, regimen, behavioural support), description of control (treatment, dosage, regimen, behavioural support); what comparisons will be constructed between which groups, concomitant medications, and excluded medications.

Outcomes: Abstinence time points for long‐ and short‐term analyses, definition of abstinence (e.g. sustained or point prevalence) at each point, biochemical validation, proportion of participants with follow‐up data at each point. Other outcome reported (HIV viral load, CD4 count, incidence of opportunistic infections, adverse effects).

Notes: Source of funding for trial, and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

As recommended in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we utilised the 'Risk of bias' tool within Review Manager 5 to assess the risk of bias for each included study (Higgins 2011; RevMan 2014). Two review authors (from EP, OD, and RL) independently assessed and reported the following information in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Method of random sequence generation.

Method of allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants, providers, or outcome assessors.

Numbers lost to follow‐up or with unknown outcome, for each outcome used in the review, by intervention/control group.

Selective outcome reporting.

Any other threats to study quality.

We graded each trial as being at 'high', 'low', or 'unclear' risk of bias for each domain, and provided justification for our judgement in the table. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed, and displayed the summary results in two 'Risk of bias' figures.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated a risk ratio (RR) for each cessation outcome for each trial included in the meta‐analysis as follows: (number of participants abstinent from tobacco in the intervention group/number of participants in the intervention group) / (number of participants abstinent from tobacco in the control group/number of participants in the control group).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis is the individual level.

Dealing with missing data

Where we identified missing data, we contacted the study authors to request missing data. We also contacted study authors if aspects of trial design or conduct were unclear.

We treated participants who have dropped out, or who were lost to follow‐up, as continuing to use tobacco. We completed reanalysis, where possible, if study authors had not considered these participants as continuing to use tobacco. We noted the proportion of participants for whom data were missing in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated levels of heterogeneity (study characteristics, methods, outcomes) between included studies to decide whether or not it is appropriate to pool the data, in two ways; firstly by checking if the confidence intervals (CIs) overlap. We used the I² statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity, given by the formula [(Q ‐ df)/Q] x 100%, where Q is the Chi² statistic and df is its degrees of freedom (Higgins 2003). This describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error (chance). A value greater than 50% may be considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity. The test has low power when used on a small number of studies (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Searching multiple sources (as detailed in the search strategies above) should reduce reporting biases. We avoided language bias by not limiting the search terms by language and used translation services where required. We did not exclude on the basis of publication status and aimed to minimise publication bias by inclusion of grey literature, conference abstracts, and the inclusion of data from unpublished trials identified from trial registries (Higgins 2011). However, this is dependent on the data being obtained.

We created a funnel plot with pseudo‐95% confidence limits to identify possible publication bias for the secondary outcome of short‐term cessation. We did not create a funnel plot for the primary outcome (long‐term cessation) because we identified less than ten studies.

Data synthesis

We extracted data from individual studies, reported them in table form, and completed a meta‐analysis. We calculated quit rates based on numbers randomised to an intervention or control group. Where possible, we conducted intention‐to‐treat analyses, i.e. including all participants initially assigned to intervention or control in their original groups. We excluded from the denominators any deaths. We treated any other losses to follow‐up as continuing tobacco users, as described above. We noted adverse events, serious adverse events, and deaths in the Results section.

Incidence of adverse events were poorly reported. It was therefore not possible to conduct a meta‐analysis of the incidence of serious adverse events, taking those randomised as the denominator and including events up to thirty days after the end of treatment. It was also not possible to conduct a sensitivity analyses restricting the denominator to those known to have taken at least one dose of treatment/intervention as this figure was not reported.

For the meta‐analysis, we pooled RRs using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model ((number of events in intervention condition/intervention denominator) / (number of events in control condition/control denominator)) with a 95% CI. Where the event is defined as tobacco cessation, a RR greater than one indicates that more people successfully quit in the treatment group than in the control group.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table for long‐term abstinence outcomes (six months or longer) and short‐term outcomes (greater than or equal to four weeks, but less than six months). We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence as it relates to the studies which contribute data to the prespecified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using GRADEpro software (GRADEproGDT 2015). We justified all decisions to down‐ or upgrade the quality of the evidence using footnotes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses, to explore the impact of different variables on the findings of the review. This allowed us to identify and investigate unexplained sources of heterogeneity.

We also completed subgroup analyses to compare the relative efficacy of the different interventions. We were unable to complete subgroup analysis to establish the effect of combined behavioural and pharmacological interventions versus single‐focus interventions in PLWHA since all identified studies used combination interventions. We therefore added a post hoc objective to investigate the effect of intensity of the intervention.

We conducted additional subgroup analyses for each intervention‐population‐outcome association and study characteristics to explore sources of any heterogeneity, using the I² statistic.

Only one study reported on the outcomes of HIV viral load and CD4 count. therefore. we did not calculate the RR or mean difference (MD).

We conducted subgroup analyses based on the provider of the behavioural intervention, mode of contact, participant selection, tailoring, number of sessions, and total duration of contact. The subgroups are as follows.

Provider of behavioural intervention

Healthcare professional

Researcher

Co‐facilitation by a PLWHA peer and a health professional

Mode of contact

Face‐to‐face

Telephone

Text message

Website/computer‐based

Where the intervention was undertaken via more than one mode, the most frequently used mode was coded.

Participant selection

Selected for willingness or motivation to quit

Not selected for willingness or motivation to quit

Tailoring

Intervention tailored for PLWHA

Intervention not tailored for PLWHA

Where no tailoring was described, it was assumed that the intervention was non‐tailored.

Intensity

A post hoc objective involved analysis according to intensity of behavioural intervention. This analysis was undertaken using the same categories defined in a previous Cochrane review (Stead 2016), adapted from the US Guidelines AHRQ 2008. This involved analysis according to number of sessions and total duration of contact time. We used planned contact time and number of sessions where possible, if this was not reported or not clear, we used the reported average.

We categorised total contact time as follows.

0 (where support was provided by text message or website use alone)

1 to 30 minutes

31 to 90 minutes

91 to 300 minutes

More than 300 minutes

We categorised number of person‐to‐person sessions as follows.

0 (where support was provided by text message or website use alone)

1 ‐ 3 sessions

4 ‐ 8 sessions

More than 8 sessions

Intensity subgroup analyses were not completed for short‐term outcomes because the planned contact may not have been completed at the time of short‐term outcome assessment.

Sensitivity analysis

We tested for small‐study effects on the results of the meta‐analysis performed.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Figure 1 contains a flow diagram detailing the search results. We identified 881 potentially relevant records; we identified some studies from more than one record. After screening and duplicate removal, we assessed 48 studiesfor eligibility and included 14 in the qualitative synthesis, 12 of which we included in a meta‐analysis. The 22 studies that we excluded are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies, and we judged 12 studies to be ongoing, which are summarised in Characteristics of ongoing studies. We assigned the studies a study identifier (ID) based on the first author and year of the first major publication.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Fourteen studies met the inclusion criteria and contributed to the review. We included all 14 studies in the qualitative synthesis, while 12 studies contributed to the quantitative synthesis. Six studies contributed to the analysis of long‐term tobacco abstinence (the primary outcome) and 11 studies to short‐term abstinence (the secondary outcome). Four studies reported both long‐ and short‐term abstinence and we included them in both analyses.

The studies are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies table. All studies were conducted after 2000, 13 of the 14 studies were conducted in the US, while one study, Elzi 2006, was conducted in Switzerland. All studies combined a behavioural intervention with pharmacotherapy, therefore, we could not investigate the objective of single versus combined intervention in this review. As an alternative, we investigated the effect of level of intensity of counselling.

We included two three‐arm studies (Humfleet 2013; Shelley 2015). In both cases, the two intervention groups were not similar enough to warrant combining them to create a single group. For these two studies, we divided the control groupsinto two equal groups and made independent comparisons as follows: intervention one versus half of the control and intervention two versus half of the control. For Humfleet 2013: computer‐based intervention versus control and individual counselling versus control. For Shelley 2015: text message versus control and text message + adherence‐based therapy versus control. In the meta‐analyes, the intervention groups are identified in the footnotes.

We did not include two studies in the meta‐analysis (Elzi 2006; Ferketich 2013). Elzi 2006 was nested in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS), the intervention group was not randomised, and it comprised participants who expressed an interest in quitting. Whereas, the control group was formed of all other smokers participating in the SHCS at the study site; they were therefore systematically different from the intervention group. Inclusion of this study in the meta‐analysis resulted in substantial heterogeneity with an I2 > 80%. We did not include Ferketich 2013 in the meta‐analysis as this study compared two pharmacotherapies and was not in‐keeping with the comparison of behavioural intervention versus less intense behavioural intervention, and did not have a control arm. The study compared 12 weeks counselling and varenicline, with 12 weeks counselling and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). It was also non‐randomised.

Sample size was variable with a high proportion of small studies; seven studies had a sample size of less than 150 participants (Cropsey 2013; Ingersoll 2009; Manuel 2013; Moadel 2012; Shuter 2014; Vidrine 2006; Wewers 2000).

Participant characteristics

More than 1600 participants contributed to the meta‐analysis for the primary outcome of long‐term abstinence (six months or greater). An additional 485 participants contributed to the meta‐analysis for the secondary outcome of short‐term abstinence (greater than or equal to four weeks, but less than six months).

Sexual orientation and ethnicity were recorded inconsistently in different studies. Only six out of 14 studies reporting any measure of sexual orientation, despite the relevance of sexual orientation in studies of PLWHA. Where sexual orientation was described, approximately 35% to 50% of participants were homosexual. The overall proportion of homosexual participants ranged from 3% in Manuel 2013 to 68% in Humfleet 2013. Notably, the participants in Manuel 2013 were all women.

Black or African American ethnicity was the modal category in eight studies. There were variations: from 95% of participants being Black in Ingersoll 2009 to 53% White in Humfleet 2013. The population of the only European study was 87% White (Elzi 2006). One study was specifically designed for the Latino community, and having a Latino/Hispanic ethnicity was an inclusion criterion of that study (Stanton 2015). The reported average age of study participants was approximately 35 to 50 years.

Description of the intervention: behavioural

Provider

Some degree of behavioural intervention was provided to the intervention group in all studies. We categorised the provider of the behavioural interventions as follows; healthcare professionals, researchers or co‐facilitated by a peer and a professional. The intervention was provided by healthcare professionals in nine studies (Elzi 2006; Ferketich 2013; Humfleet 2013; Ingersoll 2009; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Manuel 2013; Shelley 2015; Stanton 2015; Vidrine 2012), by a researcher or a graduate student in two studies (Cropsey 2013; Vidrine 2006), and co‐facilitated by a PLWHA ex‐smoker peer alongside a professional in two studies (Moadel 2012; Wewers 2000).

There was variation in the degree of detail to which the qualifications or experience of the individuals delivering the behavioural interventions was described. We therefore adopted a broad categorisation of 'healthcare professional’, which included nurses, motivational interviewing clinicians, counsellors, psychologists, and health educators, irrespective of the detail provided on their counselling skills, experience, or qualifications. Likewise, while some studies described the academic qualifications of the researchers providing interventions, little detail was provided on their training or counselling experience.

In addition to the website intervention, the participants in the computer‐based intervention group of Humfleet 2013 also received a 45‐60 minute face‐to‐face meeting, including discussion of a quit date. However, it is unclear if the provider was a clinician or a researcher, so this group was not included in the provider subgroup analysis. We attempted to contact the authors but were unable to clarify the intervention provider.

Mode of contact

In most studies the behavioural intervention was delivered face‐to‐face or via telephone, often in combination. Two studies investigated computer‐ or web‐based delivery, in which participants completed online modules (Humfleet 2013; Shuter 2014). One study delivered the intervention entirely via text message (Shelley 2015). Additional resources were provided in most studies, such as written materials.

Nearly half of the intervention groups (n = 7/16, 44%) offered between four and eight face‐to‐face or telephone sessions, and a quarter (n = 4/16, 25%) offered more than eight (Elzi 2006; Ferketich 2013; Vidrine 2012; Wewers 2000). Most of the studies with long‐term follow‐up planned to provide 91‐300 minutes of total contact time. Categorisations were made according to planned duration of contact; actual contact time per participant may have been lower. These categories also do not account for time spent using web‐based interventions or reviewing text messages.

Tailoring

Eleven of the interventions were specifically tailored to PLWHA. This was achieved through a range of methods, including emphasising impact of tobacco on the immune system and facilitation by a HIV‐positive ex‐smoker peer. Some authors did not describe how the intervention was tailored in detail. In the text message group of Shelley 2015, the text messages did not contain the words HIV or AIDS in order to ensure confidentiality, although the messages were designed to emphasise particular barriers faced by PLWHA, such as stress. We did consider this intervention tailored, but recognise that the degree of tailoring varies between studies. In the computer‐based intervention in Humfleet 2013, the authors did not explicitly state that the computer‐based intervention was tailored, although it was described as modelled on the individual counselling intervention. The counselling intervention was targeted to the needs of HIV‐positive smokers through focussing on the impact of smoking on HIV. We considered the computer‐based intervention group likely to be tailored, and therefore included it in the tailored versus generic control subgroup.

Description of interventions: pharmacotherapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) via patches and/or lozenges was offered or provided to the intervention groups in most studies. In Shelley 2015 and Ferketich 2013, varenicline was used instead. No studies included bupropion in their protocol, possibly due to the potential drug‐drug interactions with a number of anti‐retroviral therapy (ART) drugs. In Shuter 2014 only NRT administration was planned in the protocol, but some participants also received bupropion and varenicline off protocol, however, they were retained within their original groups for the ITT analysis.

Description of controls

In most studies the control group received ‘usual care’, which typically comprised NRT or varenicline, brief advice, and written materials. In two studies, the participants in the control group received no behavioural input or pharmacotherapy (Cropsey 2013; Elzi 2006).

In two studies, participants in the control group received enhanced standard care, with NRT alongside a counselling schedule involving multiple contacts (Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Stanton 2015). Although in these studies the intervention was still more intense than the control.

Other study characteristics

The vast majority of included studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The Ferketich 2013 study was not randomised; participants selected their own group (varenicline or NRT) but were encouraged by study staff to select varenicline, unless medically contraindicated. The Elzi 2006 study was also not randomised; all cohort study participants who expressed an interest in quitting were allocated to the intervention group; the control group included the remaining cohort study smokers.

Study inclusion criteria differed on one key point: whether willingness or motivation to quit was explicitly required for inclusion in the study. Five studies did not refer to motivation or willingness to quit in their inclusion criteria (Cropsey 2013; Humfleet 2013; Ingersoll 2009; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Stanton 2015). In Elzi 2006, interest in quitting was required for the intervention group, but not for the control.

The outcome of cessation was self reported in all studies, which was biochemically verified in all except one study (Elzi 2006). Biochemical verification was achieved mostly through expired carbon monoxide. Most studies used a cut‐off point of < 7 parts per million (ppm) or < 10 ppm, although the lowest cut‐off point used was < 3 ppm (Cropsey 2013). In this study no participants in the intervention or control groups achieved abstinence verified by this low cut‐off point, although 22% of the intervention group did achieve abstinence at the < 10 ppm cut‐off point (Cropsey 2013). In keeping with our protocol, we used the most conservative estimate of abstinence (Pool 2014). Two studies used a combination of methods for biochemical verification; expired carbon monoxide and urine cotinine, or urine cotinine and nicotine levels.

Only three studies used the outcome measure of sustained abstinence. The most commonly used measure was 7‐day point prevalence smoking abstinence (PPA). One study planned to measure both 7‐day PPA and sustained abstinence, but the data collected were insufficient to report sustained abstinence (Shuter 2014).

Excluded studies

We list 22 studies as excluded. Reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Two studies reported non‐randomised allocation and were therefore at high risk of bias for allocation concealment (Elzi 2006; Ferketich 2013). All studies included in the meta‐analysis were randomised. The method of allocation concealment was generally not described; only one study explicitly reported method of allocation concealment, but this was not in sufficient detail to permit judgement of bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants or personnel was not described in 12 out of 14 studies, and therefore the risk of these biases was unclear. In Ferketich 2013, participants chose their group; we therefore judged this study to be at high risk of performance bias. In Manuel 2013, a single provider delivered the counselling to both the intervention and control groups, therefore we judged that it was not feasible to blind the provider. Due to the nature of the behavioural interventions, it would have been difficult to blind providers to participant allocation in most studies.

Blinding of outcome assessment was only reported in detail in two studies (Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Manuel 2013). In both studies, researchers blinded to the allocation status of the participant completed the outcome assessment and we therefore judged these studies to be at low risk of detection bias. In all other studies, risk of detection bias was unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged one study to be at high risk of attrition bias (Manuel 2013). In this study, one participant was lost to follow‐up and no data were imputed for them (i.e. not considered missing = smoking). In addition, of the three participants who reported abstinence, biochemical testing for confirmation of abstinence was only performed on two specimens of urine, the reason for which was not explained. We considered the remaining studies to have low or unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

No study authors posted full study results on the clinical trial registries. We judged five studies to be at high risk of reporting bias. The outcome measures were not reported as described in the protocol in three studies (Humfleet 2013; Moadel 2012; Shuter 2014). In each study, the authors stated in the protocol that sustained abstinence and PPA outcomes would be assessed, however only reported PPA outcomes without explanation. Sustained abstinence data were obtained via communication with the authors for Humfleet 2013, however PPA outcomes were used in the meta‐analysis since the authors definition of sustained abstinence (defining relapse as seven consecutive days of smoking) means that PPA is the strictest definition of abstinence.

In Ingersoll 2009, the design of the trial included two groups: intervention versus control. However, the study authors stated that there was no difference between the two groups and published only aggregated data, including baseline characteristics and outcome. We obtained per group data from the study author for inclusion in the analysis.

In Cropsey 2013, the authors report measuring expired carbon monoxide and urine cotinine, but did not report these results.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not judge any studies to be at risk of 'other’ bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Long‐term cessation

For long‐term abstinence, a pooled estimate combining the six included studies showed no evidence of effect for the intervention (risk ratio (RR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.39; moderate quality evidence) with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4; Table 1). Abstinence in the control group at long‐term follow‐up was 8% (n = 69/842) and in the intervention group was also 8% (n = 61/760).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Tobacco cessation intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Long‐term abstinence (≥ 6 months).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Tobacco cessation intervention versus control, outcome: 1.1 Proportion of participants abstinent.

We did not create a funnel plot for the long‐term outcome because fewer than 10 studies were included.

Short‐term cessation

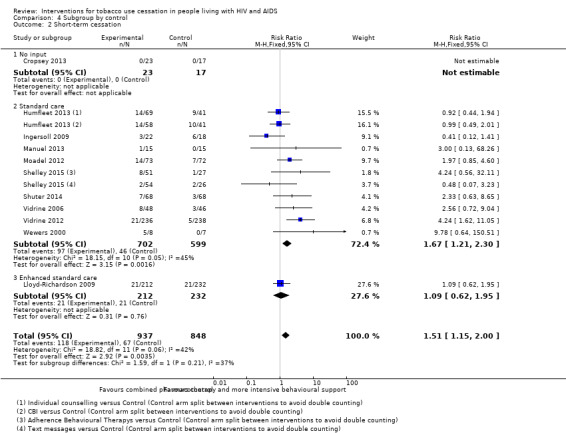

For short‐term abstinence, a pooled estimate of the 11 included studies showed benefit of intervention (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.00; very low quality evidence) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 42%) (Analysis 2.1; Figure 5; Table 1). Abstinence in the control group at short‐term follow‐up was 8% (n = 67/848) and in the intervention group was 13% (n = 118/937).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Tobacco cessation intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Short‐term abstinence (4 weeks to < 6 months).

5.

For the short‐term outcome, a funnel plot showed some evidence of asymmetry, suggesting the possibility of publication bias (Figure 6).

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Tobacco cessation intervention versus control, outcome: 2.1 Short‐term abstinence (4 weeks to < 6 months).

We undertook a sensitivity analysis, removing smaller studies, and this did not significantly change the pooled estimate. We undertook a sensitivity analysis according to whether NRT or varenicline was given; it did not significantly change the pooled estimates for long‐term or short‐term abstinence (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2). Only one study included in the meta‐analysis used varenicline (Shelley 2015). We undertook a further sensitivity analysis according to the degree of intervention provided to the control: no input, standard care, or enhanced standard care. Two studies provided enhanced standard care (Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Stanton 2015); as may be expected the quit rate observed amongst controls was higher in these studies compared to controls receiving standard care or no input. For short‐term outcomes, in the sensitivity analysis excluding these studies, the pooled estimate for the effect of the intervention increased slightly (Analysis 4.2). For long‐term outcomes, the pooled estimate did not markedly change (Analysis 4.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup by drug, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup by drug, Outcome 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup by control, Outcome 2 Short‐term cessation.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup by control, Outcome 1 Long‐term cessation.

Subgroup analyses

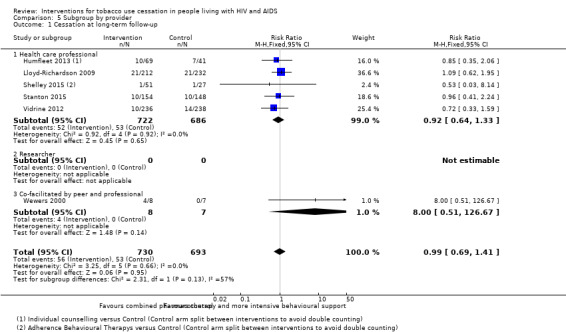

Effect of provider

We categorised the provider of the behavioural intervention as follows: healthcare professional, researcher, or co‐facilitation by a peer and professional (Analysis 5.1). We failed to detect evidence of a difference in the effect according to provider in the analysis for long‐term abstinence. For short‐term outcomes, the pooled estimate for interventions that were co‐facilitated by a peer and professional (RR 2.52, 95% CI 1.14 to 5.56) were slightly larger than for other providers (healthcare professional alone: RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.03; and researcher: RR 2.56, 95% CI 0.72 to 9.04). However, the CIs overlapped.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup by provider, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

Effect of mode of contact

We failed to detect evidence of an effect of subgroup categorisation by mode of contact for long‐term abstinence (Analysis 6.1). For short‐term outcomes, the pooled estimate was highest for interventions delivered via telephone (RR 3.69, 95% CI 1.80 to 7.53; Analysis 6.2). This was predominantly driven by the effect of one, large study (Vidrine 2012). There were few studies in some subgroups, which limits the conclusions possible from this subgroup analysis; only one intervention was delivered via text message (Shelley 2015), and two were delivered via computers (Humfleet 2013; Shuter 2014).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup by mode of contact, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup by mode of contact, Outcome 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up.

Participant selection

We failed to detect evidence of an effect of participant selection for long‐term abstinence (Analysis 7.1). For short‐term outcomes there is evidence of a difference in effect according to whether willingness or motivation to quit was required for participant inclusion (Analysis 7.2). The subgroup of participants who were selected for their willingness or motivation to quit had a higher pooled estimate of effect (RR 2.74, 95% CI 1.73 to 4.34, I² = 0%) compared to the subgroup for whom this was not required (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.35, I² = 0%).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup by selection, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup by selection, Outcome 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up.

Tailoring

All studies which reported long‐term outcomes provided a tailored intervention, and one of these studies even tailored the control (Shelley 2015); therefore it was not possible to compare tailored to generic interventions for long‐term abstinence (Analysis 8.1). For short‐term outcomes, there was no strong evidence of a difference in effect for interventions tailored for PLWHA compared to generic interventions (Analysis 8.2). The comparison was limited due to the small number of studies providing a generic intervention. Only two studies provided a generic intervention, and in one of these, no participants in the intervention or control arm achieved abstinence at the level of biochemical verification set by the authors (Cropsey 2013).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup by tailoring, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup by tailoring, Outcome 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up.

Intensity

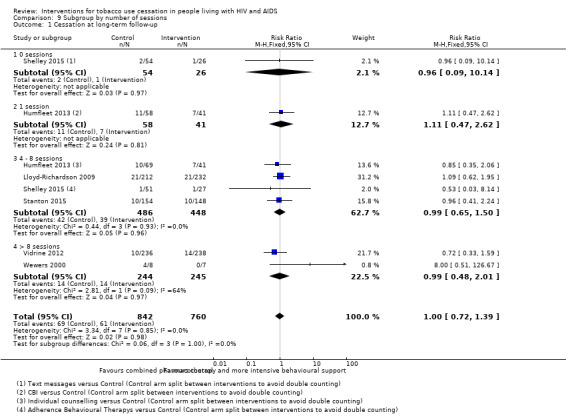

The investigation of intensity of behavioural intervention, via number of sessions and total duration of contact for long‐term abstinence, was a post hoc objective; we failed to detect evidence of a difference in effect according to either number of sessions or duration of total intervention (Analysis 9.1; Analysis 10.1). There were few studies in each subgroup. Intensity subgroup analyses were not completed for short‐term outcomes because the intervention may not have been completed at the time of short‐term outcome assessment.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Subgroup by number of sessions, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Subgroup by total contact time, Outcome 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up.

Adverse events

It was not possible to perform a quantitative synthesis of adverse events, since only one study reported them in detail (Ferketich 2013).

HIV outcomes

It was not possible to perform the planned quantitative synthesis of HIV outcomes ‐ CD4 count, viral load, and incidence of opportunistic infections ‐ since only one study reported them (Elzi 2006).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review provides evidence from 14 studies. More than 1600 participants from 12 studies contributed to the meta‐analysis for the primary outcome of long‐term abstinence.

In this review we found that more intense combined interventions of pharmacotherapy and behavioural support were effective in increasing the chance of achieving abstinence in the short‐term (four weeks to less than six months) compared to a control group that typically included a single brief intervention and pharmacotherapy. The pooled estimate for short‐term outcomes (risk ratio (RR) 1.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15 to 2.00) indicates that a combined intervention might typically increase cessation success by 15% to 100%. However, this effect was not observed for long‐term abstinence (greater than six months).

There are differences between studies ‐ in particular whether participants were selected for their willingness or motivation to quit. Those studies including only motivated or willing participants showed a larger pooled estimate of the effect of the intervention for short‐term outcomes, although this was not observed at long‐term follow‐up.

As noted, we were unable to assess one of the original objectives ‐ whether interventions combining pharmacotherapy and behavioural support were more effective than either type of support alone. This was because all included studies assessed a combined intervention compared to control. We added a post hoc objective assessing the effect of intensity of behavioural intervention. This analysis did not find any evidence of a difference in the effect of intensity. Although this subgroup analysis was limited by the small number of studies and does not definitively indicate that increasing the intensity would not result in an increased effect. In the general population, Stead 2016 also found no evidence that more intensive support increased the effect of treatment. Our analysis according to intensity only included personal contact time via telephone or in person. This may have underestimated the impact of interventions delivered via computers or text messages.

Subgroup analysis was undertaken according to whether the intervention was tailored for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). We failed to detect evidence of a difference in effect for tailored interventions for short‐term abstinence, although this analysis was limited by a small number of studies providing a generic intervention. Subgroup analysis by tailoring was not possible for long‐term outcomes because all studies provided a tailored intervention.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All studies included in the meta‐analysis were undertaken in the US, although they do encompass a range of demographic profiles. There are health system and socioeconomic differences between the US and Europe, as well as between the US and sub‐Saharan Africa, where the majority of PLWHA live (UNAIDS 2015). This limits the generalisability of these results. Among ongoing studies, most are based in North America, although NCT01484340 is based in South Africa.

There remains a lack of studies which have large sample sizes and that assess long‐term abstinence (greater than six months).

Quality of the evidence

We evaluated the overall quality of the evidence according to GRADE criteria. For the primary outcome of long‐term cessation, we judged the quality of evidence to be moderate. The quality of the evidence was downgraded due to risk of bias; one study was judged to be at high risk of reporting bias, and allocation concealment and blinding were poorly described.

For the secondary outcome of short‐term cessation, we judgedthe quality of evidence to be very low due to inconsistency, in addition to reporting and detection biases.

We judged five studies to be at high risk of reporting biases where outcomes described in the protocol were not accounted for in the published reports. Although, in most cases communication with the study authors resulted in additional data being made available, or the study authors provided an explanation as to why they were unable to report the proposed outcomes. Allocation concealment and blinding were poorly described and therefore we assessed most studies to have 'unclear' judgements in these areas. There was also a high proportion of small studies, which reflects that this is a relatively new area of research. The rationale for upgrading or downgrading the quality of the body of evidence is presented in Table 1.

Potential biases in the review process

There is evidence of possible publication bias in the funnel plot for short‐term outcomes, despite substantial effort being made to locate studies within the grey literature. Although we did identify some attrition bias and reporting bias, the impact of these were reduced through correspondence with authors to clarify points or request additional data. Additional data were kindly provided in most of these cases.

We added one objective post hoc ‐ assessing the impact of intensity of the behavioural intervention on abstinence, and therefore potentially introducing some bias. However, we felt it was logical and consistent with the ethos of the original objective ‐ to assess whether combined interventions are more effective than pharmacotherapy and behavioural support alone.

As is standard for Cochrane Reviews, all reports were reviewed and all data were extracted in duplicate in order to reduce bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We believe that this is the first systematic review of tobacco cessation interventions for PLWHA to include meta‐analysis. A previous systematic review provided a narrative overview and included some studies excluded by our stricter inclusion criteria (Moscou‐Jackson 2014).

In the general population, interventions that combine behavioural and pharmacotherapy components have been shown to be effective for long‐term abstinence when compared to a brief intervention without pharmacotherapy (Stead 2016), the reason for this effect not being observed in PLWHA is not clear. In the general population, tailoring cessation interventions has been shown to increase their effect (Hartmann‐Boyce 2014). This was not shown in this review, but our comparison was limited by a small number of studies with a non‐tailored generic intervention. It is important to consider that the evidence presented here is limited and has been judged to be of very low to moderate quality. There is much more and higher quality evidence assessing smoking cessation interventions and finding them effective in the general public. Therefore, it would be too premature to say that interventions aimed at the general population will not benefit PLWHA.

However, the following could explain a less pronounced effect. People living with mental illnesses have some similarities to PLWHA; they use more tobacco than the general population, often consume tobacco alongside drugs or alcohol, and may use tobacco to cope with their illness or treatment side effects (Tsoi 2013). In Tsoi and colleagues’ review of smoking cessation interventions for people with schizophrenia they found that at short‐term follow‐up there was evidence in favour of a combined intervention (counselling and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)) (Tsoi 2013), but long‐term follow‐up failed to detect evidence of a difference between the intervention and control. Their results echo the results of this meta‐analysis and could reflect a higher potential for relapse in people with complex chronic diseases and multiple challenges. However, the comparison is limited, as the two populations have distinct differences, both medically and psychosocially.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review must be considered in the context of the small number of studies included and the low to moderate quality of the evidence, and it therefore should not be ruled out that smoking cessation interventions that have been found to work in the general population will not have an effect in PLWHA. More intense combined interventions of pharmacotherapy and behavioural support were shown to be effective in assisting PLWHA to achieve short‐term abstinence, when compared to controls in this review; however this effect was not observed at long‐term follow‐up. This could be a function of study biases. Therefore, evidence suggests that clinicians should offer a combined intervention to PLWHA who use tobacco, at least comprising a brief behavioural intervention with pharmacotherapy, since even non‐sustained periods of abstinence have proven health benefits. The effects of tailoring, number of contacts and total duration of contact of behavioural support remain unclear.

Implications for research.

Further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of tobacco cessation interventions in PLWHA are needed; they should include a large sample size and ensure that follow‐up continues for at least six months, and preferably 12 months.

In this review, there was evidence of effectiveness of the intervention at short‐term follow‐up; however, we rated the quality of this evidenceas 'very low' according to GRADE, and we did not observe any effect at long‐term follow‐up. Further research is needed to address the potential biases in the existing literature, including investigating relapse prevention in PLWHA who achieve short‐term abstinence. This would maximise the probability of short‐term success being translated into long‐term abstinence.

Trials assessing the impact of tailoring and intensity of interventions are also needed. Data on sexual orientation should be routinely collected and reported in studies of PLWHA. Tobacco consumption may effect treatment response, as such, future studies measuring HIV outcomes ‐ CD4 count, viral load, and incidence of opportunistic infections ‐ would be highly informative. The fact that almost all studies are based in the US limits generalisability due to population and health system differences. Further studies should be based in a range of contexts, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries with a high burden of HIV and tobacco consumption.

Future studies should ensure that reporting is in line with CONSORT criteria (Schulz 2010), particularly with regard to blinding and allocation concealment. None of the included studies reported their study in line with these criteria and as such, we judged many to be of 'unclear' risk of bias.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of all at the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction group, particularly Lindsay Stead, Nicola Lindson‐Hawley and Monaz Mehta. We would like to thank Lindsay Stead and Claire Duddy for assistance with the search strategy, and Gonçalo Figueiredo Augusto at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) who translated an article from Spanish to English for the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Search terms for MEDLINE search:

1. RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL.pt.

2. CONTROLLED‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL.pt.

3. CLINICAL‐TRIAL.pt.

4. Meta analysis.pt.

5. exp Clinical Trial/

6. Random‐Allocation/

7. randomized‐controlled trials/

8. double‐blind‐method/

9. single‐blind‐method/

10. placebos/

11. Research‐Design/

12. ((clin$ adj5 trial$) or placebo$ or random$).ti,ab.

13. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj5 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab.

14. (volunteer$ or prospectiv$).ti,ab.

15. exp Follow‐Up‐Studies/

16. exp Retrospective‐Studies/

17. exp Prospective‐Studies/

18. exp Evaluation‐Studies/ or Program‐Evaluation.mp.

19. exp Cross‐Sectional‐Studies/

20. exp Behavior‐therapy/

21. exp Health‐Promotion/

22. exp Community‐Health‐Services/

23. exp Health‐Education/

24. exp Health‐Behavior/

25. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24

26. smoking cessation.mp. or exp Smoking Cessation/

27. "Tobacco‐Use‐Cessation"/

28. "Tobacco‐Use‐Disorder"/

29. Tobacco‐Smokeless/

30. exp Tobacco‐Smoke‐Pollution/

31. exp Tobacco‐/

32. exp Nicotine‐/

33. ((quit$ or stop$ or ceas$ or giv$) adj5 smoking).ti,ab.

34. exp Smoking/pc, th [Prevention & Control, Therapy]

35. 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 [A category smoking terms]

36. exp Smoking/ not 35 [B category smoking terms]

37. 1 or 2 or 3 [Likely CT design terms; RCTs, CCTs, Clinical trials]

38. 35 and 25 [A category smoking+all design terms]

39. 35 and 37 [A category smoking terms+likely CT design terms]

40. (animals not humans).sh. [used with 'not' to exclude animal studies for each subset]

41. ((26 or 27 or 28 or 29) and REVIEW.pt.) not 38 [Set 4: Core smoking related reviews only]

42. 36 and 25 [B category smoking+all design terms]

43. (42 and 37) not 40 [Set 3: B smoking terms, likely CT design terms, human only]

44. 38 not 39 not 40 [Set 2: A smoking terms, not core CT terms, human only]

45. (35 and 37) not 40 [Set 1: A smoking terms, likely CT design terms, human only]

46. exp Smoking Cessation/ not (44 or 45) [Smoking cessation only, no design terms]

47. exp hiv infections/ or exp acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/

48. hiv/ or hiv‐1/ or hiv‐2/

49. ("acquired immunodeficiency syndrome" or "acquired immunedeficiency syndrome" or "acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome" or "acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome").mp.

50. "HIV/AIDS".mp.

51. HIV.mp.

52. PLWHA.mp

53. 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 [Any topic term]

54. 45 and 53 [Set 1 plus topic]

55. 44 and 53 [Set 2 plus topic]

56. 43 and 53 [Set 3 plus topic]

57. 54 or 55 or 56 [All sets]

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Tobacco cessation intervention versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Long‐term abstinence (≥ 6 months) | 6 | 1602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.72, 1.39] |

Comparison 2. Tobacco cessation intervention versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short‐term abstinence (4 weeks to < 6 months) | 11 | 1785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.15, 2.00] |

Comparison 3. Subgroup by drug.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up | 6 | 1602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.72, 1.39] |

| 1.1 NRT | 5 | 1444 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.73, 1.42] |

| 1.2 Varenicline | 1 | 158 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.13, 4.38] |

| 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up | 11 | 1785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.15, 2.00] |

| 2.1 NRT | 10 | 1627 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [1.13, 1.99] |

| 2.2 Varenicline | 1 | 158 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [0.49, 5.92] |

Comparison 4. Subgroup by control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Long‐term cessation | 6 | 1602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.72, 1.39] |

| 1.1 Standard care | 4 | 856 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.61, 1.51] |

| 1.2 Enhanced standard care | 2 | 746 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.65, 1.69] |

| 2 Short‐term cessation | 11 | 1785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.15, 2.00] |

| 2.1 No input | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Standard care | 9 | 1301 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [1.21, 2.30] |

| 2.3 Enhanced standard care | 1 | 444 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.62, 1.95] |

Comparison 5. Subgroup by provider.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up | 6 | 1423 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.69, 1.41] |

| 1.1 Health care professional | 5 | 1408 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.64, 1.33] |

| 1.2 Researcher | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 Co‐facilitated by peer and professional | 1 | 15 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.0 [0.51, 126.67] |

| 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up | 10 | 1470 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [1.19, 2.23] |

| 2.1 Healthcare professional | 6 | 1176 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.98, 2.03] |

| 2.2 Researcher | 2 | 134 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.56 [0.72, 9.04] |

| 2.3 Co‐facilitated by peer and professional | 2 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.52 [1.14, 5.56] |

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup by provider, Outcome 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up.

Comparison 6. Subgroup by mode of contact.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up | 6 | 1602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.72, 1.39] |

| 1.1 Face‐to‐face | 2 | 554 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.63, 1.65] |

| 1.2 Telephone | 2 | 552 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.33, 1.50] |

| 1.3 Computer | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.47, 2.62] |

| 1.4 Text message | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.09, 10.14] |

| 1.5 Equal face‐to‐face and telephone | 2 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.61, 2.82] |

| 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up | 11 | 1785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.15, 2.00] |

| 2.1 Face‐to‐face | 6 | 809 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.77, 1.61] |

| 2.2 Telephone | 3 | 646 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.69 [1.80, 7.53] |

| 2.3 Computer | 2 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.68, 2.34] |

| 2.4 Text message | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.07, 3.23] |

| 2.5 Equal face‐to‐face and telephone | 1 | 15 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.78 [0.64, 150.51] |

Comparison 7. Subgroup by selection.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up | 6 | 1602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.72, 1.39] |

| 1.1 Selected for motivation/willingness to quit | 3 | 647 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.49, 1.84] |

| 1.2 Motivation/willingness to quit not required for inclusion | 3 | 955 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.70, 1.49] |

| 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up | 11 | 1785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.15, 2.00] |

| 2.1 Selected for motivation/willingness to quit | 7 | 1052 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.74 [1.73, 4.34] |

| 2.2 Motivation/willingness to quit not required for inclusion | 4 | 733 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.65, 1.35] |

Comparison 8. Subgroup by tailoring.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at long‐term follow‐up | 6 | 1602 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.68, 1.31] |

| 1.1 Tailored intervention versus generic control | 5 | 1444 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.68, 1.33] |

| 1.2 Tailored intervention versus tailored control | 1 | 158 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.13, 4.38] |

| 1.3 Generic intervention versus generic control | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Cessation at short‐term follow‐up | 11 | 1785 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.44 [1.10, 1.91] |

| 2.1 Tailored intervention versus generic control | 7 | 1463 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [1.02, 1.83] |

| 2.2 Tailored intervention versus tailored control | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.07 [0.86, 5.01] |

| 2.3 Generic intervention versus generic control | 2 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 68.26] |

Comparison 9. Subgroup by number of sessions.