Abstract

This manuscript examines how personally knowing a deportee and/or undocumented immigrant affects the mental health of Latina/o adults. Utilizing a new survey sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico (n=1,493), we estimate a series of logistic regressions to understand how personal connections to immigrants are affecting the mental health of Latinos using stress process theory. Our modeling approach takes into consideration the socio-political, familial, cultural, and personal contexts that make up the Latina/o experience, which is widely overlooked in data-sets that treat Latinos as a homogeneous ethnic group. Our findings suggest that knowing a deportee increases the odds of having to seek help for mental health problems. The significance of this work has tremendous implications for policy makers, health service providers, and researchers interested in reducing health disparities among minority populations especially under a new administration, which has adopted more punitive immigration policies and enforcement.

Keywords: health disparities, mental health, deportations, Latino populations, survey research

Introduction

A new era in immigration enforcement appears to be gaining momentum, especially under the Trump Administration. Federal rules for deportations have been eased and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents have aggressively been perusing undocumented immigrants. Under high scrutiny, many immigrants have chosen to go into hiding or to avoid going to church, the store, doctor’s appointments, school, and more (Fischer and Taub 2017; Yee 2017). As immigration enforcement ramps up under the Trump Administration, it is important to reflect on the foundation the Obama Administration created to facilitate some of these more aggressive policies.

The Obama Administration has been criticized by many immigration advocates for the dramatic increase in deportations of Latin American immigrants seen in recent years. Adding to the fire, the unprecedented wave of Central American migrants during the summer of 2014 led to a stronger focus on immigrant detention policies and practices. These dynamics spurred ideologically charged debates about the Obama Administration’s immigration policy enforcement (Chishti, Hipsman, and Bui 2014; The Economist 2014). While some argued for leniency and the release of certain detained immigrants (such as unaccompanied minors), others argued for their swift deportation (Foley 2014). Although calls for comprehensive immigration reform have been made for over a decade, the humanitarian crisis at the border coupled with the record number of deportations highlights the urgency of the issue.

The dramatic increase in immigration policy enforcement, including deportations and detentions, has important repercussions for immigrants and their families. These range from social, economic, and political challenges (Becerra et al. 2013; Catanzarite and Aguilera 2002; Gentsch and Massey 2011; Koper et al. 2013; McConnell 2015; Orrenius and Zavodny 2014), to psychosocial and health consequences (Amuedo-Dorantes and Pozo 2014; Brabeck and Xu 2010; Capps et al. 2007; De Genova 2010; Dreby 2012, 2015; Gubernskaya, Bean and Van Hook 2013b; Hurtado, Gurin, and Peng 1994; Köhler and Sola-Visner 2014; Rhodes et al. 2015). Although social scientists have identified that there are social consequences associated with the shift in deportation policy during the Obama Administration, this work has to date not utilized quantitative approaches to explore the indirect influence of this policy climate on the Latino population.

In an attempt to add a new perspective to this growing literature, we focus on analyzing the effects of personally knowing an immigrant who has been detained or deported on an individual’s mental health outcomes. Our analysis is guided by stress process theory as qualitative studies have signaled deportations and detentions as sources of chronic stress. We utilize data from the 2015 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico Latino National Health and Immigration Survey to examine how Latinos’ personal connections to immigrants impact their health and well-being. We find that knowing a person who has been deported or detained increases the likelihood of an individual having experienced mental health issues. Moreover, this effect is intensified as the number of persons known to have been deported or detained increases.

We close our discussion by highlighting the many implications our findings have for policymakers, scholars, and advocates who are concerned with the unintended consequences associated with the current immigration policy agenda of the United States. Although we use the term ‘Latino’ and ‘Hispanic’ interchangeably in this study for the sake of simplicity, we do acknowledge the vast diversity and heterogeneity that exists among people of Latin American origin in the United States. We argue that our findings point to the deep and extensive connections among this diverse group of Latinos and Latino immigrants. These connections help to solidify immigration as an extremely salient issue for thousands of Latino families across the nation.

Stress Process Theory

Stress process theory posits that an individual’s social location (e.g. race, gender, class, age, etc.) and structural contexts expose them to varying levels of stressors (Pearlin 1989). Stressors have the power to disrupt myriad facets of an individual’s life including social statuses, roles, relationships, and activities (Pearlin, Aneshensel, and Leblanc 1997). Additionally, because social locations and contexts reflect the unequal distribution of resources, racial and gender supremacy, and socioeconomic norms, finding oneself in the lower echelons of these systems is itself a source of stress (Meyer, Shwartz, and Frost 2008). Researchers have found that mobility between social locations can affect health outcomes. Alcántara, Chen, and Alegría (2014) for example, find an association between perceived downward social mobility and increased odds in reporting fair and poor physical health and major depressive episodes among Latino immigrants.

Latino immigrants experience a variety of stressors that span both temporal and sociopolitical landscapes and that are rooted in structural processes beyond individual-level preventative behaviors. Ornelas and Perreira (2011) classify these stressors into three different categories: pre-migration experiences (e.g. political or socioeconomic turmoil in country of origin), migration experiences (e.g. physical journey to destination country), and post-migration experiences (e.g. racial/ethnic discrimination in country of settlement). They find that stressors from each category strongly contribute to negative mental health outcomes for Latino immigrants. In our analysis, we examine if respondents have personally experienced discrimination and its association with mental health problems.

A key component of stress process theory, and a critical concept for this paper, addresses the issue of stress proliferation. Stress proliferation refers to the, “expansion or emergence of stressors within and beyond a situation whose stressfulness was initially more circumscribed,” (Pearlin, Aneshense, and Leblanc 1997 p. 223). Stress proliferation explains the emergence of secondary stressors produced by traumatic events, unwanted or rapid changes in roles or social status, or chronic strain. Merton (1968) argues that role disruption affects not only the individual experiencing the sudden change in status, but also those within their familial and social networks. As Pearlin et al. (2005) plainly put it, “lives are linked across the life course, and one person’s transition may become another’s hardship,” (p. 213).

The context of this paper engulfs both structural and individual level processes and sources of stress. At the structural level we find federal immigration policies of detention and deportation as well as the socioeconomic position of Latinos and Latino immigrants within U.S. society. At the individual level, we find traumatic events, social dislocation, and the psychosocial responses they produce. It is not deportation itself that negatively impact individuals but the threat of deportation (De Genova 2010; Dreby 2012, 2015; Harrigan, Koh, and Amirrudin 2016). The following section focuses on how knowing a deportee can impact mental health outcomes through stress proliferation.

Confluence of Life Events and Chronic Strains: How Knowing a Detainee/Deportee Impacts Health

The Obama Administration faced steady criticism for what some perceive to be extremely aggressive enforcement of federal immigration policy (Ahmed 2014). Deportations under Obama have doubled compared to the Bush Administration, going from 189,026 in 2001 to over 430,000 by 2013 (Department of Homeland Security 2013). This record number of deportations was achieved through tougher enforcement of immigration policies, including expansion of federal programs such as Secure Communities, 287 (g), E-verify, continuation of immigration raids from the Bush Era, and through further militarization of the border (Department of Homeland Security 2014a; Lozano and Lopez 2013; McLeigh 2010). These numbers led to many immigrant rights organizations dubbing President Obama the “Deporter-in-Chief” (Epstein 2014). Furthermore, the increase in militarization and criminalization of immigrants has not only contributed to record deportation numbers but also to the profiling, mistreatment, and victimization of immigrants (Sabo et al. 2014).

The conditions under which immigrants are detained and deported have garnered much attention by human and immigrant rights organizations (ACLU 2014; Anderson 2010; Hernandez 2008; Shahshahani 2012), but the problems are best known among immigrants and Latinos themselves. Spanish news media often report on the conditions and protests, and information is easily communicated among the immigrant and Latino community.

Kremer, Moccio, and Hammell (2009) find that news of detentions and raids caused some immigrant families to go into hiding for days at a time, contributing to the further isolation and marginalization of undocumented immigrants. Moreover, families of those detained often have little to no information on the whereabouts of their detained family members, causing confusion, anxiety, and stress (Kremer, Moccio and Hammell 2009). Additionally, Familiar et al. (2011) find that migrant relatives in Mexico suffer from elevated levels of depression and anxiety, a finding that further validates the interconnectedness of Latinos and points to the transnational, macro-level externalities of U.S. immigration policies.

Given these dynamics, the effects of personally knowing someone who has been detained and deported can cause health issues due to increased stress, anxiety, and fear of oneself or a family member being placed under those conditions. McGuire (2014) argues that the enforcement of “draconian rigid policies” of detention and deportation can have especially significant effects on the mental health of immigrant families, especially for the children and spouses of those left behind. In what Enriquez (2015), describes as “multi-generational” punishment, U.S. citizen children and their undocumented parents often share in the risks and punishment associated with undocumented immigration status. In other words, immigration enforcement is not just impacting undocumented immigrants it is also spilling over to their US citizen family members.

In addition to the direct impact on family members, the detention and deportation of immigrant parents has spillover effects and has negative effects on extended family and community members (Androff et al. 2011; Potochnick, Chen, and Perreira 2016). Raids and detentions have led to interruptions in schooling, affecting children of detained immigrants as well as other community organizations and family members (Capps et al. 2007; Chaudry et al. 2010).

The stress of deportation is also affecting immigrant’s health-seeking behaviors (Cavazos-Rehg, Zayas, and Spitznagel 2007; Hacker et al. 2011). Writing about California’s Proposition 187, Berk and Schur (2001) found that the law did not have a direct impact on these behaviors but that fear of deportation in general did. They found that those who reported being fearful of being denied care were often unable to receive the services they needed. Hacker et al. (2011) also note that these effects go beyond the individual level. Fear and distrust of law enforcement can lead to immigrants not reporting crimes and withdrawing from community engagement. In recent work, Vargas (2015) finds that among mixed-status families the risk of being deported decreases the odds of using social services like Medicaid and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (Vargas 2015; Vargas and Pirog 2015). This has implications for the health of Latinos as a whole, citizen and non-citizens alike. Moreover, under-utilization of social services like WIC, prenatal care, and Medicaid will exacerbate health disparities putting American children at greater risk of experiencing negative health outcomes.

Finally, and important to our theory regarding the potential for this rise in detentions and deportations to have an in-direct effect on Latino adults more broadly than the previous literature has suggested, recent data has suggested that the Latino population is highly conscious of this shift in policy. Recent survey data from Latino Decisions has provided direct evidence that the Latino population, not just immigrants, is conscious of the rise of deportations and anti-immigrant climate. In fact, the data we use here conducted by that firm found that 36 percent of Latino immigrants know someone personally who has been detained or deported, with an astonishing 78 percent of respondents believing that there is an anti-Hispanic/immigrant climate in the United States.

Our theory that deportations and detentions could influence the well-being of Latinos who are not themselves immigrants is grounded in the work of those who have explored the formation of identity among Latinos during the current immigration climate (Chavez, 2008; Massey and Sanchez, 2010; Wiley, Figueroa, and Lauricella, 2014). For example, Douglas Massey and Magaly Sánchez (2010) illustrate through in-depth interviews that immigrants from Latin America formulate a Latino identity soon after arriving to the US largely due to a hostile environment that includes punitive policies. This is supported by the work of Wiley, Figueroa, and Lauricella (2014) who argue that Latinos have become aware of their perceived unrecognized place in society by the large number of deportations and restrictionist laws. We believe that this work has laid the groundwork for our analysis that more directly assesses the relationship between detention policy and Latino health. We have also attempted to treat Latina/os as a heterogeneous group by modeling citizenship status, national origin (Mexican versus non Mexican category), and language of interview to better understand the nuisances of the Latina/o experience in the US.

In sum, the aggressive enforcement of federal immigration policies, through increased detentions and deportations, contributes to a process of stress proliferation where a stress-inducing issue in one area of one’s life contributes to stress in other areas, contributing to negative health outcomes (Thoits 2010). Based on this evidence and extant research, we propose the personal connection to deportee(s) hypothesis: Latinos who personally know someone who has been detained/deported will have a higher likelihood of reporting poor mental health. We anticipate that the substantive impact of knowing someone who has been detained/deported will be greater compared to knowing someone who is undocumented, or not knowing either.

Data and Methods

We take advantage of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico’s 2015 Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (LNHIS), which is a unique survey designed for the specific purpose of examining Latinos’ personal relationships with immigrants and health. The survey is ideal for our analysis given that it contains measures of Latinos’ personal connections with immigrants and health outcomes. These items include questions that ask individuals if they personally know someone who is an undocumented immigrant or if they personally know someone who has been detained or deported. Latino Decisions implemented the survey and worked in conjunction with the scholars at the RWJF Center for Health Policy at UNM to design the survey instrument. This is therefore an ideal dataset for our research question. The Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (Total N=1,493) relies on a sample provided by a mix of cell phone and landline households along with web surveys. This mixed-mode approach improves our ability to capture a wide segment of the Hispanic population in the sample by providing a mechanism to poll the growing segment of the Hispanic population that lacks a land-line telephone as well as those who prefer to engage surveys on-line. This approach is sensitive to some of the major shifts in survey methodology driven by changes in the communication behavior of the population. More specifically, the increasing number of Americans who have decided to use a cell-phone for telephone communication while doing away with their land-line telephone motivates our expansion of sample beyond land-line households. A total of 989 Latinos were interviewed over the phone and an additional 504 Latinos were sampled through the Internet to create a dataset of 1,493 respondents. The web focused respondents were randomly drawn from the Latino Decision’s national panel of Latino adults. Respondents for the web are from a double-opt-in national Internet panel, and then randomly selected to participate in the study, and weighted to be representative of the Latino population. The web mode allows respondents to complete the survey in either English or Spanish, and contained the exact same questions as the phone mode.

All phone calls were administered by Pacific Market Research in Renton, Washington. The survey has an overall margin of error of +/− 2.5 percent with an AAPOR response rate of 18 percent for the telephone sample. Latino Decisions selected the 44 states and Puerto Rico with the highest number of Latino residents for the sampling design, states that collectively account for 91 percent of the overall Latino adult population. Respondents across all modes of data collection could choose to be interviewed in either English or Spanish. All interviewers were fully bilingual. A mix of cell phone (35 percent) only and landline (65 percent) households were included in the sample, and the full dataset including both phone and web interviews are weighted to match the 2013 Current Population Survey universe estimate of Latino adults with respect to age, place of birth, gender, and state. The survey was approximately 28 minutes long and was fielded from January 29, 2015 to March 12, 2015.

The primary mental health outcome variable of interest deals with problems with mental health within the Latino National Health and Immigration Survey dataset. The mental health variable was created using the survey question “In the past 12 months did you think you needed help for emotional or mental health problems, such as feeling sad, anxious, or nervous--yes or no?”, which is identical to the California Health Interview Survey, the Princeton and Columbia University Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Survey, and other national surveys (Cranford et al. 2009; Eisenberg et al. 2009; Gollust et al. 2008; Sentell et al. 2008; Sorkin et al. 2009; Wells et al. 2001). Given the binary nature of this variable (0=no, 1=yes), we use logistic regression to estimate the probability of needing to seek help with emotional or mental health problems, such as feeling sad, anxious, or nervous, our mental health outcome.

Our main explanatory variables are three ‘personal connections to immigrants’ dichotomous categories as well as a rank variable that sums the total number of deportees respondents personally know. The two survey items we draw from to create our first measure of personal connections to immigrants are: a) Do you personally know someone who has faced detention or deportation for immigration reasons? b) Now take a moment to think about all the people in your family, your friends, coworkers, and other people you know. Do you happen to know somebody who may be an undocumented immigrant? We use these separate survey items and create three mutually exclusive categories if respondents know someone who has been detained/deported (1=yes, 0=no), if they know someone who is undocumented only (1=yes, 0=no), and a category if they do not know either an undocumented or detained/deported immigrant (1=yes, 0=no), which we specify as our reference category. In coding this variable, we assigned respondents who know someone who has been deported and someone that is undocumented as knowing a deportee. Likewise, if a respondent knows a deportee but does not know an undocumented immigrant we code this respondent as knowing a deportee. Lastly, if they do not know a deportee but know an undocumented immigrant, they are coded as knowing someone who is undocumented only. We also contextualized the relationships of respondents to deportees. In the survey, if respondents indicated they knew a deportee, they were asked to report their relationship to the detained or deported person(s) by selecting from a list of different relationship categories (e.g., parents, spouse, other family members, friend). Respondents could only select each relationship category once, regardless of whether they knew one or multiple deportees within that relationship category (e.g., a respondent who knew multiple individuals who were deported that were all friends would only select the “friend” category).

From these responses, we coded: if any known deportees were a family member or a friend/acquaintance (1=deportee was a family member, 0=friend or acquaintance), or if any known deportees were a main breadwinner, either in the deportee’s family or the respondent’s family (1=deportee was the breadwinner, 0=deportee was not the breadwinner).

Lastly, we model the magnitude of Latinos’ personal connections to deportees by creating an indicator that counts the number of different types of relationships to deportees. This variable was created using the responses to the relationship category question. We counted each unique relationship category selected as a different deportee known (ranging from 0–6). We then summed up the number of responses on that list to create our ranked variable. Given that the mean of this variable is 0.58 and not normally distributed, we collapse this rank ordered variable into three categories of knowing a deportee (0=none, 1=1–2 deportees, 3=3 deportees and above). We know of only one published paper that uses these measures. While not health related this study finds that Latino voters who personally know deportees and undocumented immigrants are more likely to report that they think the President and Congress should act on immigration policy versus all other policies (Sanchez et al. 2015)

Summary statistics for all variables used in this analysis are listed in Table 1. Our analytic approach is focused on the exploration of various logistic regressions intended to determine if our measures of personal connections to immigrants is correlated with mental health among the Latino population.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics 2015 RWJF/Latino Decisions Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (n=1,493).

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Problems1 | 0.25 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Personally Know a Detained/Deported Immigrant | 0.39 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Personally Know an Undocumented Immigrant | 0.27 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Do not Personally Know Deportee or Undocumented Immigrant | 0.34 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Deportee is a Relative | 0.35 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Deportee is Main Breadwinner | 0.49 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Number of Deportees Known | 0.58 | 0.96 | 0 | 6 |

| Do not know deportee | 0.61 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Know 1–2 deportees | 0.34 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Know 3–6 deportees | 0.04 | --- | 0 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Citizenship Status: U.S. Citizen | 0.77 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 0.62 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Education2 | 5.52 | 2.36 | 1 | 10 |

| Age | 45.87 | 17.00 | 18 | 98 |

| Married3 | 0.53 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income Missing | 0.21 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: Less than 20K | 0.25 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: 20K–39K | 0.21 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: 40k–60k | 0.13 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: 60k –80k | 0.09 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: 80k–100k | 0.06 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: 100k–150k | 0.07 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Income: 150k+ | 0.04 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Currently Uninsured4 | 0.15 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Spanish5 | 0.58 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Mexican | 0.55 | --- | 0 | 1 |

| Discrimination | 0.37 | --- | 0 | 1 |

Mental Health Problems [sought help for mental health problems in the last 12 months]: (0=No, 1=Yes)

Highest education levels completed, (1= No formal schooling, 2= Grade 1–8, 3=Some HS, 4=GED, 5=HS Graduate, 6=Some College, 7=Associates, 8=Bachelors, 9=MA, 10=Ph.D./MD)

Married: (0=Unmarried, 1=Married)

Insurance Coverage: (0=Currently Insured, 1= Currently Uninsured)

Language of Interview: (0=English, 1=Spanish)

Finally, we control for a handful of measures that have been found to be correlated with Latino health status in previous research. Among the demographic variables we include standard measures of income, educational attainment, age, marital status, gender, and insurance coverage. To assess income we have included several dummy variables representing different income categories: $20,000-$39,999, $40,000-$59,999, $60,000-$79,999, $80,000-$99,999, $100,000-$149,999, and $150,000 and above with less than $19,999 serving as the reference category. We also include an income variable of “unknown” income in the model, which includes respondents who did not report their income. We included this unknown income variable as a method to save cases and include these respondents in our models. To control for culture- and Latino-specific variables we include citizenship status, language of interview, Mexican origin, and experiences with discrimination. The inclusion of Mexican origin also allows us to control for the differences in mental health care access among Latino populations. To code citizenship status, we explicitly asked respondents: “Are you currently a U.S. citizen, a Legal Permanent Resident, or a non-citizen?” We then coded citizenship status as 1=U.S. citizen, 0=non U.S. citizen. In our discrimination measure, we asked respondents: “Have you ever been treated unfairly because of your race, ethnicity, or national origin here in the United States?” This measure is specific to racial/ethnic discrimination, making it ideal for our analysis, and has been utilized in numerous studies (Harris et al. 2013; Gee et al. 2006). All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 12 software, complex survey weights, and state fixed effects (StataCorp. 2011). Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). We include state fixed effects to control for the variation of state and local law enforcement cooperation with ICE by state. Our analytical approach is intended to determine the relationship between personally knowing a deportee or an undocumented immigrant on the probability of needing help for emotional or mental health problems within a nationally representative sample of Latino adults. Our primary focus is to test our personal connection to deportee(s) hypothesis to determine the effect of knowing a deportee on predicting poor mental health. We also estimated our models using both probit and linear probability regresssion models as a robustness check. We did not find any important differences in our results and use logistic regression as our preferred analytic technique largely due to the simplicity in interpretation.

Results

We begin with a discussion of the distributions from our sample (which are provided in table 1). After dropping missing data, we have a total sample of 1,318 respondents. On average about 25 percent of the sample stated that in the past 12 months they needed to seek help with mental health problems. For our measures of personal connections with immigrants, 39 percent of our sample knows an immigrant who has been deported, 27 percent know an undocumented immigrant, and 34 percent of respondents did not know either a deportee or undocumented immigrant. Of those respondents who know a deportee, over 35 percent indicated that they knew a deportee that was a close family member, and 49 percent reported that they knew a deportee who was the main breadwinner. Furthermore, with respect to the number of deportees a respondent knows, we found that 61 percent of respondents know 0 deportees, 34 percent know 1–2 deportees, and 4 percent know 3 or more. The mean age in our sample is 46, and the majority of our sample has a high school education. Just over half of our sample completed the survey in Spanish, and over half of the sample was female. In regards to citizenship, 77 percent of our sample consists of U.S. citizens and 14 percent of the respondents are permanent residents. Over half are of Mexican origin and 37 percent reported experiencing discrimination because of their race or ethnicity.

Our first set of logistic regression models test the difference between Latinos’ personal connections to immigrants on the probability of needing help with mental health problems in the past 12 months, controlling for a vector of variables. Our results in table 2 estimate a logistic regression model that includes respondents who personally know someone who has been deported and respondents who know an undocumented immigrant compared to respondents who do not know either (reference category), controlling for age, education, gender, income, insurance coverage, citizenship, marital status, experiences with discrimination, Mexican origin, language of interview, and state fixed effects. There is strong support for our primary hypothesis, as we find that there are differences between knowing a deportee on the probability of reporting poor mental health. In fact, Latinos who personally know someone who has been detained or deported are 1.9 times more likely (p<0.01) to report having problems with mental health in the past 12 months compared to Latinos who do not personally know someone that has been deported, holding all else constant. In other words, the odds of a Latino personally knowing someone who has been detained or deported increases their odds of reporting problems with mental health is 87 percent, holding all else constant. We find marginal differences for respondents who personally know someone who is undocumented compared to not knowing an undocumented immigrant. We therefore see that a more general connection to the undocumented population is not detrimental to one’s mental health, while having a very direct and personal connection to immigration policy has a very pronounced influence on one’s mental health.

Table 2.

Logistic Coefficients for Regression of Knowing Someone That Is Undocumented or Deported on Mental Health Problems a 2015 RWJF/Latino Decisions Latino National Health and Immigration Survey

| VARIABLES | β | Standard Error | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Category: Not Knowing Someone Detained/Deported or Undocumented | |||

| Deported or Detained | 0.625*** | 0.17 | 1.868*** |

| Undocumented | 0.299* | 0.181 | 1.349* |

| Citizenship Status: U.S. Citizen1 | 0.310* | 0.185 | 1.363* |

| Female | 0.126 | 0.139 | 1.134 |

| Education2 | −0.104*** | 0.04 | 0.902*** |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.005 | 1.001 |

| Married | −0.309** | 0.149 | 0.734** |

| Income Reference Category: Less than $20,000 | |||

| Income Missing | −0.452** | 0.211 | 0.636** |

| Income: 20K–39K | −0.844*** | 0.21 | 0.430*** |

| Income: 40k–60k | −0.530** | 0.235 | 0.589** |

| Income: 60k –80k | −0.398 | 0.286 | 0.672 |

| Income: 80k–100k | −0.716** | 0.32 | 0.489** |

| Income: 100k–150k | −0.696** | 0.321 | 0.499** |

| Income: 150k+ | −0.420 | 0.426 | 0.657 |

| Currently Uninsured | 0.173 | 0.177 | 1.189 |

| Spanish | 0.267 | 0.179 | 1.306 |

| Mexican | −0.774*** | 0.169 | 0.461*** |

| Discrimination | 0.977*** | 0.145 | 2.656*** |

| Constant | 0.182 | 3.011 | 1.200 |

| Observations | 1,294 | ||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.107 | ||

Notes:

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1,

β is a logit coefficient, using complex survey weights and state fixed effects.

Citizenship: (0= Permanent Residents and Undocumented, 1=U.S. Citizen)

Highest education levels completed: (1= No formal schooling, 2= Grade 1–8, 3=Some HS, 4=GED, 5=HS Graduate, 6=Some College, 7=Associates, 8=Bachelors, 9=MA, 10=Ph.D./MD)

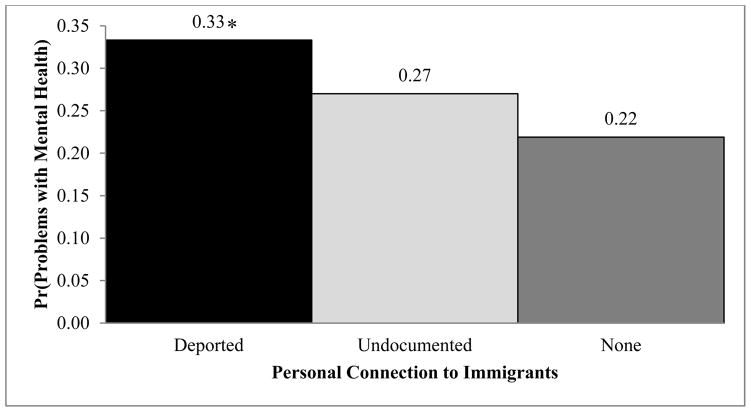

The substantive impacts of these relationships are shown in figure 1, which displays the post-estimation results of our logistic regression. Figure 1 graphs the adjusted predicted probabilities of Latinos’ personal connections to immigrants on mental health problems. As shown, respondents who personally know an immigrant who has been detained or deported are statistically more likely to report poor mental health relative to Latinos who do not personally know someone who has been deported. In fact, if a respondent personally knows someone who has been, deported the probability of them reporting problems with mental health are 33 percent, holding all else constant.

Figure 1. Adjusted Predicted Probabilities of Logistic Regression Model of Latinos Personal Connections to Immigrants on Intent to Seek Help for Mental Health Problems: 2015 RWJF/Latino Decisions Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (n=1,294).

Note. Controlling for Education, Age, Income, Gender, Citizenship, Mexican Origin, Language of Interview, Discrimination, Marital Status, insurance coverage,, state fixed effects, and complex survey weights (all of which were set to their mean or mode values). *P < 0.01 for the difference between not knowing a deportee versus knowing a deportee and knowing an undocumented immigrant.

Our next model estimates a logistic regression to examine the probability of needing to seek help for mental health problems as the number of deported immigrants respondents personally know increases. In this model, we use our categorical measures of the number of deportees and set not knowing a deportee as our reference category. There is strong support for these results as shown in table 3, as we find that as the number of deportees a Latino knows personally increases the probability of reporting poor mental health increases. In fact, if respondents personally know 1–2 deportees as opposed to not knowing any deportees the likelihood of needing help for emotional or mental health problems such as feeling anxious, sad, or nervous increases by a factor of 1.5 (p<0.05), holding all else constant. In other words, knowing 1–2 deportees increases the odds of needing help for emotional or mental health problems by 45 percent, holding all else constant. This disparity increases for respondents who personally know 3 or more deportees. The results suggests that respondents who personally know 3 or more deportees as opposed to knowing zero deportees increases the likelihood of needing help for emotional or mental health problems such as feeling anxious, sad, or nervous by a factor of 4 (p<0.01), holding all else constant.

Table 3.

Logistic Coefficients for Regression of Number of Deportees Known on Mental Health Problems a 2015 RWJF/Latino Decisions Latino National Health and Immigration Survey.

| VARIABLES | β | Standard Error | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Category: Do Not Know Any Deportees | |||

| Personally Know 1–2 Deportees | 0.374** | (0.146) | 1.454** |

| Personally Know 3+ Deportees | 1.413*** | (0.322) | 4.109*** |

| Citizenship Status: U.S. Citizen1 | 0.321* | (0.185) | 1.378* |

| Female | 0.101 | (0.140) | 1.106 |

| Education2 | −0.104*** | (0.040) | 0.901*** |

| Age | 0.002 | (0.005) | 1.002 |

| Married | −0.341** | (0.149) | 0.711** |

| Income Reference Category: Less than $20,000 | |||

| Income Missing | −0.446** | (0.211) | 0.640** |

| Income: 20K–39K | −0.850*** | (0.212) | 0.427*** |

| Income: 40k–60k | −0.500** | (0.235) | 0.606** |

| Income: 60k –80k | −0.402 | (0.287) | 0.669 |

| Income: 80k–100k | −0.711** | (0.324) | 0.491** |

| Income: 100k–150k | −0.714** | (0.323) | 0.490** |

| Income: 150k+ | −0.396 | (0.432) | 0.673 |

| Currently Uninsured | 0.165 | (0.178) | 1.179 |

| Spanish | 0.320* | (0.180) | 1.377* |

| Mexican | −0.756*** | (0.169) | 0.469*** |

| Discrimination | 0.962*** | (0.145) | 2.617*** |

| Constant | 0.447 | (3.013) | 1.564 |

| Observations | 1,295 | ||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.113 | ||

Notes:

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1,

β is a logit coefficient, using complex survey weights and state fixed effects.

Citizenship: (0= Permanent Residents and Undocumented, 1=U.S. Citizen)

Highest education levels completed, (1= No formal schooling, 2= Grade 1–8, 3=Some HS, 4=GED, 5=HS Graduate, 6=Some College, 7=Associates, 8=Bachelors, 9=MA, 10=Ph.D./MD)

Income Reference Category: Less than $20,000

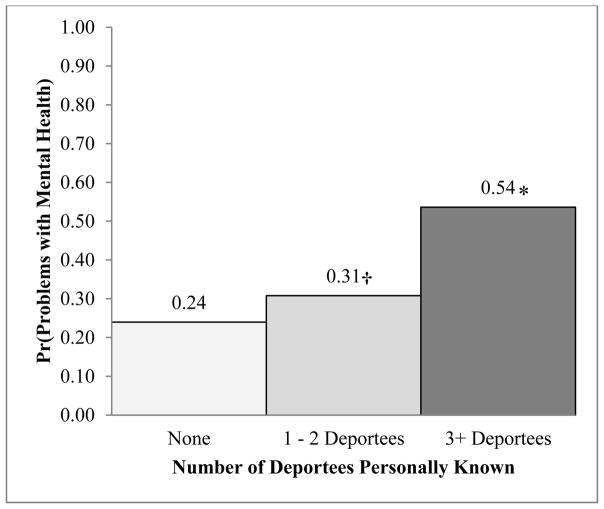

The substantive impacts of these relationships are shown in figure 2, which displays the post-estimation results of our logistic regression. Figure 2 graphs the predicted probabilities for each category of knowing a deportee on mental health problems. As shown, personally knowing 1–2 and 3 or more deportees increases the odds of reporting mental health problems. This provides strong evidence that there is a cumulative effect, where stronger connections with the deported population, reflected in multiple relationships, yield more harmful effects.

Figure 2. Adjusted Predicted Probabilities of Logistic Regression Model of the Number of Deportees Known on Intent to Seek Help for Mental Health Problems, 2015 RWJF/Latino Decisions Latino National Health and Immigration Survey (n=1,295).

Note. Controlling for Education, Age, Income, Gender, Citizenship, Mexican Origin, Language of Interview, Discrimination, Marital Status,, insurance coverage, state fixed effects, and complex survey weights (all of which were set to their mean or mode values). *P < 0.01 for the difference between not knowing a deportee versus knowing 3 or more deportees. †P < 0.05 for the difference between not knowing a deportee versus knowing 1–2 deportees.

Regarding demographic control variables we find that, across the models, U.S. citizens are more likely to report problems with mental health. When we further decompose citizenship status, we find that non-citizen permanent residents are less likely to report problems with mental health relative to U.S. citizens. We find no difference for non-citizen undocumented respondents in our analysis. We also find an inverse relationship between education and mental health problems in those respondents with higher levels of education. These individuals with more education are less likely to report problems with mental health. This finding is also consistent with income, as higher incomes Latinos are less likely to report problems with mental health relative to those making under $20,000. Both education and income have traditionally been thought of as protective factors and we find similar results in our research. Regarding our other control variables, we find that respondents of Mexican origin are less likely to report problems with mental health than their Latino co-ethnic counterparts. This finding is in line with prior research that shows the Mexican origin Latinos are less likely to report mental illness such as anxiety, depression, and substance use relative to other Latino groups such as Puerto Ricans (Alegría et al. 2008).

Lastly, consistent with the literature on discrimination and health, we find that respondents who have experienced discrimination because of their race or ethnicity are more likely to report problems with mental health (Gee et al. 2006). In our sensitivity analysis, we also ran models to better understand the type of relationship respondents have with deportees. For example, if the deportee was a relative versus a co-worker. In the full sample, we do find statistical differences if the deportee is a family member relative to not knowing a deportee. In our stratified models, we find that among respondents that know a deportee, there are no statistical differences if the deportee is a close relative of family versus a friend. We also do not find differences if the deportee was the main breadwinner or if the breadwinner was a male. Lastly, given that deportation and detainment are very different experiences, we also attempt to understand this experience and find no differences in mental health if the deportee has been deported or currently in detainment or have been recently released.

Discussion

The findings of our analysis show that simply knowing a person who has been detained and deported affects one’s mental health. This association between knowing a deportee and negative mental health outcomes is not a direct one. Instead, this relationship is nuanced and dynamic and involves psychosocial processes. We utilize stress process theory to shed light on these processes, to help us understand the mechanisms behind the relationship between knowing a deportee and mental health.

With a large majority of Latinos knowing an undocumented immigrant and large percent personally knowing someone who has been detained and deported, immigration continues to be a particularly salient issue for the Latino community. Immigration policy and its enforcement creates important and multifaceted externalities that affect Latinos, their families, and their communities. These externalities are both direct and indirect.

Latino immigrants who have been deported or who are currently detained awaiting deportation face conditions that pose risks to their personal safety. These conditions may also create situations of stress, anxiety, and fear that affect their mental health. We expect that the trauma experienced through abuse, neglect, and family disruptions are negative indicators that may affect these individuals tremendously. What is less known however is how these experiences impact the wellbeing of their families as well as the overall community. We find strong support for our theory that the record number of deportations is having an indirect effect on the mental health of those who are connected to the deportee population. These negative indicators also impact healthcare and mental health social service providers who aim to help families in distress.

The families of those detained or deported also face many challenges as they confront the economic and social hardships the sudden removal and detainment of a family member can cause. Social networks and extended families can therefore become strained and vulnerable themselves. The children of detained individuals, who are sometimes U.S. citizens, are put in extremely precarious situations. They must endure the sudden loss of a parent or parents, experience sudden uprooting and environment changes, and cope with stress and trauma, many times without adequate professional help.

As we have found in this analysis, the manner in which federal immigration policies are being enforced has far reaching effects. It is not necessary for an individual themselves to be detained or deported or have a family member detained or deported for these effects to be felt. The mere fact of knowing someone who has been detained or deported can have detrimental impacts on Latino mental health. These findings point to the strong connection among Latinos and Latino immigrants and elucidate the severity of the marginalization of undocumented immigrants, as even merely knowing someone with a precarious legal status contributes to your own sense of danger and vulnerability.

These findings contribute to the growing literature on the effects of immigration and public policy on the health of Latinos which is especially important as the Latino population grows and is faced with more punitive immigration policies and enforcement (Stewart et al. 2015). These findings serve to better inform the policymaking process to create policies that can address critical issues of social services, safety, and population health while still protecting the social, economic, and health conditions of individuals and their families.

We also must acknowledge the limitations of this study. Given that our study is cross-sectional and a study of Latino populations, we are limited in our ability to make causal claims and generalizations across racial and ethnic populations over time. This limitation is not particular to this study, as currently there are no datasets which query respondents on their personal relationships with deportees and physical and mental health status. We also realize that detention and deportation are two very different experiences. We have attempted to test this difference and find no differences, which suggest just knowing a deportee is bad for mental health and their current status in the deportation process is not associated with poor mental health.

Conclusion

Immigration is an ideologically charged issue, producing political gridlock that has hampered the passage of meaningful immigration reform. This inaction has allowed the federal government to enforce and strengthen already existing immigration policies. As mentioned in this paper, this focus on enforcement of federal immigration policies has meant a dramatic increase in the detention and deportation of unauthorized immigrants. And as we have shown through this study, this rise in deportations has indirectly contributed to negative mental health outcomes for Latinos.

These findings, along with extant literature cited in this article, highlight the urgency of policy action on immigration reform. Although a bipartisan legislative solution may appear implausible, a more feasible policy consideration for decision makers is placing a moratorium on immigrant deportations. Removing the specter of deportation would have an immediate impact on the stress levels of individuals, and consequently affect positive mental health outcomes. Moreover, a moratorium would allow the Department of Homeland Security and its enforcement agencies to address issues of efficiency, safety, and human rights violations claims made by detainees and their families.

Although the fates of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) extension and the Deferred Action for Parental Accountability (DAPA) are currently being debated in the Supreme Court, they serve as a model of how reprieve from deportation can affect not only the health of unauthorized immigrants, but their socioeconomic status as well. They also serve as models for alternative policy solutions to comprehensive immigration reform that includes mechanisms for assuaging the negative effects of detention and deportation.

These policy recommendations, however, are ultimately only temporary solutions to a progressively inadequate and inefficient immigration legislative framework. Comprehensive immigration reform is needed, and policymakers must take into account the real effects of their policy choices on immigrants, their families, and communities as they debate and draft this reform.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The project described is supported, in part, by a NICHD training grant to the University of Wisconsin–Madison ((T32HD049302) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Biographies

Dr. Edward D. Vargas holds a Ph.D. in Public Affairs from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the School of Transborder Studies at Arizona State University. His research interests include the effects of poverty and inequality on the quality of life, focusing specifically on health, education, and social policy, and how these factors contribute to the well-being of vulnerable families. Dr. Vargas serves as a Co-PI on the 2015 Latino National Health and Immigration Survey, and Co-PI on the Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey (CMPS) 2016.

Melina D. Juárez is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at the University of New Mexico. She is also a Robert Wood Johnson Center for Health Policy Doctoral Fellow and a Transformar Fellow at El Centro de la Raza at the University of New Mexico. She holds an MA in Transatlantic Politics from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Her work focuses on Latinx, minority, and LGBTQI politics; immigration policy; and health equity. Utilizing intersectionality, queer, decolonization, and class-based theories she explores how identity and socioeconomic status interact with public policy and politics to affect a variety of political and health outcomes.

Dr. Gabriel Sanchez is a Professor of Political Science at the University of New Mexico and also serves as the Executive Director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy and Co-Director of the Institute of Policy, Evaluation and Applied Research (IPEAR) at the University of New Mexico. Sanchez was formerly the Director of Research, and now Principal at Latino Decisions, the nation’s leading survey firm focused on the Latino electorate. His research agenda focuses on understanding the impact of racial and ethnic diversity on the U.S. political system.

Maria Livadais is a doctoral fellow at the UNM Center for Health Policy and a doctoral student in political science. She obtained her bachelor’s degree from Southern Oregon University in International Studies with minors in Economics and Biology. During her undergraduate career Maria completed the Ronald E. McNair scholar program and interned for Quantros, a health informatics company in Silicon Valley focused on patient safety.

Currently, Maria is working on several projects with multidisciplinary teams on Hispanics and the health insurance exchange and on electronic health records effects on physicians’ workflow. Her research interests include health disparities, health insurance exchanges, and health informatics policy.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- ACLU. Warehoused and Forgotten: Immigrants Trapped in Our Shadow Private Prison System. American Civil Liberties Union; New York, NY: 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( https://www.aclu.org/warehoused-and-forgotten-immigrants-trapped-our-shadow-private-prison-system) [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A. Protesters rally across US for immigration reform. Al Jazeera America; New York, NY: 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/4/5/protesters-rallyacrossusforimmigrationreform.html) [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara C, Chen C, Alegría M. Do post-migration perceptions of social mobility matter for Latino immigrant health? Social Science & Medicine. 2014;101:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, Meng XL. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant US Latino groups. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. Jailed Without Justice: Immigrant Detention in the US. Amnesty International. New York, NY: 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.amnestyusa.org/pdfs/JailedWithoutJustice.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Amuedo-Dorantes C, Pozo S. On the intended and unintended consequences of enhanced US border and interior immigration enforcement: Evidence from Mexican deportees. Demography. 2014;51(6):2255–2279. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L. Punishing the Innocent: How the Classification of Male-to-Female Transgender Individuals in Immigration Detention Constitutes Illegal Punishment under the Fifth Amendment. Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law & Justice. 2013;25(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Androff DK, Ayón C, Becerra D, Gurrola M. US immigration policy and immigrant children’s well-being: The impact of policy shifts. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 2011;38(1):77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo BA, Bullock JL. The Psychological Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prisoners in Supermax Units Reviewing What We Know and Recommending What Should Change. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2008;52(6):622–640. doi: 10.1177/0306624X07309720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra D, Androff D, Cimino A, Wagaman MA, Blanchard KN. The impact of perceived discrimination and immigration policies upon perceptions of quality of life among Latinos in the United States. Race and Social Problems. 2013;5:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3(3):151–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton-Jarrett R, Hair E, Zuckerman B. Turbulent Times: Effects of Turbulence and Violence Exposure in Adolescence on High School Completion, Health Risk Behavior, and mental health in young adulthood. Social Science and Medicine. 2013;95:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck K, Xu Q. The Impact of Detention and Deportation on Latino Immigrant Children and Families: A Quantitative Exploration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010;32(3):341–361. [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Castaneda RM, Chaudry A, Santos R. Paying the Price: The Impact of Immigration Raids on America’s Children. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/411566-Paying-the-Price-The-Impact-of-Immigration-Raids-on-America-s-Children.PDF) [Google Scholar]

- Catanzarite L, Bernabe Aguilera M. Working with co-ethnics: Earnings penalties for Latino immigrants at Latino jobsites. Social Problems. 2002;49:101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zayas LH, Spitznage EL. Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(10):1126–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudry A, Capps R, Pedroza JM, Castaneda RM, Santos R, Scott MM. Children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth. 2011;4(1):137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez L. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chishti M, Hipsman F, Bui B. The Stalemate over Unaccompanied Minors Holds Far-Reaching Implications for Broader U.S. Immigration Debates. Policy Beat, Migration Policy Institute; 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/stalemate-over-unaccompanied-minors-holds-far-reaching-implications-broader-us-immigration) [Google Scholar]

- Coffey GJ, Kaplan I, Sampson RC, Montagna Tucci M. The meaning and mental health consequences of long-term immigration detention for people seeking asylum. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(12):2070–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Eisenberg D, Serras AM. Substance use behaviors, mental health problems, and use of mental health services in a probability sample of college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(2):134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criminal Justice Fact Sheet. NAACP. 2015 Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.naacp.org/pages/criminal-justice-fact-sheet)

- Crosnoe R. Health and education of children from racial/ethnic minority or immigrant families. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(1):77–93. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genova N. The deportation regime: Sovereignty, space and the freedom of movement. In: De Genova Nicholas Nicholas, Peutz Nathalie., editors. In The Deportation Regime. Durham: Duke University Press; 2010. pp. 33–65. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Homeland Security. 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. 2013 Table 39. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_yb_2013_0.pdf)

- Department of Homeland Security. United States Border Patrol: Enacted Border Patrol Program Budget by Fiscal Year. States and Summaries. 2014a Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/BP%20Budget%20History%201990-2013.pdf)

- Department of Homeland Security. ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations: FY 2014. 2014b Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/images/ICE%20FY14%20Report_20141218_0.pdf)

- Dreby J. The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(4):829–845. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont DM, Wildeman C, Lee H, Gjelsvik A, Valera P, Clarke JG. Incarceration, maternal hardship, and perinatal health behaviors. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014;18(9):2179–2187. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1466-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnest J. Press Briefing by Press Secretary Josh Earnest 7/7/2014. The White House Press Office; Washington, DC: 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/07/07/press-briefing-press-secretary-josh-earnest-772014) [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and Help Seeking for Mental Health Among College Students. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66(5):522–541. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RJ. Politico. New York, NY: 2014. National Council of La Raza leader calls Barack Obama “deporter-in-chief. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.politico.com/story/2014/03/national-council-of-la-raza-janet-murguia-barack-obama-deporter-in-chief-immigration-104217.html) [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SL. White House to Spend Millions to Curb Undocumented Children Cross Border. CNN Politics. 2014 Jun 21; Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.cnn.com/2014/06/20/politics/us-central-american-immigration/)

- Familiar I, Borges G, Orozco R, Medina-Mora M. Mexican migration experiences to the US and risk for anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130(2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Prisons. Inmate Statistics. 2015 Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp)

- Fisher M, Taub A. The New York Times. New York, NY: 2017. Trump Deportation Order Risk: Immigrants Driven Underground. Retrieved March 3, 2017 ( https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/23/world/trump-migrants-deportation.html?emc=edit_nn_20170226&nl=morning-briefing&nlid=74420988&te=1&_r=0) [Google Scholar]

- Foley E. The Huffington Post. New York, NY: 2014. Hillary Clinton: Unaccompanied Minors ‘Should be Sent Back’. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/06/18/hillary-clinton-immigration_n_5507630.html) [Google Scholar]

- Gavett G. Map: The U.S. Immigration Detention Boom – Immigration. Frontline. 2011 Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/race-multicultural/lost-in-detention/map-the-u-s-immigration-detention-boom/)

- Geller A, Garfinkel I, Cooper CE, Mincy RB. Parental Incarceration and Child Well-Being: Implications for Urban Families. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90(5):1186–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, Holt J. Self-Reported Discrimination and Mental Health Status among African Descendants, Mexican Americans, and Other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: The Added Dimension of Immigration. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentsch K, Massey DS. Labor Market Outcomes for Legal Mexican Immigrants Under the New Regime of Immigration Enforcement. Social Science Quarterly. 2011;92(3):875–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Eisenberg D, Golberstein E. Prevalence and correlates of self-injury among university students. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH. 2008;56(5):491–498. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.491-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gonzales M, Malcoe LH, Espinosa J. The Hispanic Women’s Social Stressor Scale Understanding the Multiple Social Stressors of U.S.- and Mexico-born Hispanic Women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30(2):200–229. [Google Scholar]

- Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450–1454. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.11.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Ensminger ME, Robertson JA, Juon H. Impact of Adult Sons’ Incarceration on African American Mothers’ Psychological Distress. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(2):430–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubernskaya Z, Bean FF, Van Hook J. Why does naturalization matter for the health of older immigrants in the United States? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013a;54(4):426. doi: 10.1177/0022146513504760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubernskaya Z, Bean FF, Van Hook J. (Un)Healthy Immigrant Citizens: Naturalization and Activity Limitations in Older Age. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013b;54(4):427–443. doi: 10.1177/0022146513504760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Chu J, Leung C, Marra R, Pirie A, Brahimi M, English M, Beckmann J, Acevedo-Garcia D, Marlin RP. The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(4):586–594. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney C. Mental Health Issues in Long-Term Solitary and “Supermax” Confinement. Crime & Delinquency. 2003;49(1):124–156. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AG, Henderson GR, Williams JD. Courting Customers: Assessing Consumer Racial Profiling and Other Marketplace Discrimination. Journal of Public Policy. 2005;24(1):163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks T. The San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, CA: 2007. The Human Face Of Immigration Raids In Bay Area/Arrests Of Parents Can Deeply Traumatize Children Caught In The Fray, Experts Argue. Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/The-human-face-of-immigration-raids-in-Bay-Area-2598853.php#photo-2088080) [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy-Fiske M, Carcamo C. Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, CA: 2014. Overcrowded, Unsanitary Conditions Seen at Immigrant Detention Centers. Retrieved June 27, 2016. ( http://www.latimes.com/nation/nationnow/la-na-nn-texas-immigrant-children-20140618-story.html#page=1) [Google Scholar]

- Hernández DM. Pursuant to Deportation: Latinos and Immigrant Detention. Latino Studies. 2008;6(1):35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Detained and Dismissed: Women’s Struggles to Obtain Healthcare in United States Immigration Detention. 2009 Retrieved June 27, 2016. ( http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/wrd0309web_0.pdf)

- Hurtado A, Gurin P, Peng T. Social identities—A framework for studying the adaptations of immigrants and ethnics: The adaptations of Mexicans in the United States. Social Problems. 1994;41:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison B. New York Daily News. New York, NY: 2015. Bronx Man Who Was Beaten and Kept in Solitary Confinement As a Teen at Rikers Island Commits Suicide. Retrieved June 27, 2016. ( http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-crime/ex-rikers-inmate-beaten-jail-commits-suicide-article-1.2250130) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston V. Australian asylum policies: have they violated the right to health of asylum seekers? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2009;33(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler JR, Sola-Visner M. The silent crisis: children hurt by current immigration enforcement policies. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(2):103–104. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koper CS, Guterbock TM, Woods DJ, Taylor B, Carter TJ. Overview of: “The Effects of Local Immigration Enforcement on Crime and Disorder: A Case Study of Prince William County, Virginia. Criminology & Public Policy. 2013;12(2):237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Wildeman C, Wang EA, Matusko N, Jackson JS. A heavy burden: the cardiovascular health consequences of having a family member incarcerated. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(3):421–427. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. Al Jazeera America. New York, NY: 2015. Inmates Riot at For-Profit Texas Immigrant Facility. Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/2/23/Texas-prison-riot.html) [Google Scholar]

- Lopez WD, Kruger DJ, Delva J, Llanes M, Ledón C, Waller A, Harner M, et al. Health Implications of an immigration raid: findings from a Latino community in the Midwestern United States. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2016;19(3):702–708. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano FA, Lopez MJ. Border Enforcement and Selection of Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Feminist Economics. 2013;19(1):76–110. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Sanchez MR. Brokered Boundaries: Creating Immigrant Identity in Anti-Immigrant Times. Russell Sage Foundation Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell ED. Restricted movement: Nativity, citizenship, legal status, and the residential crowding of Latinos in Los Angeles. Social Problems. 2015:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S. Borders, centers, and margins: critical landscapes for migrant health. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science. 2014;37(3):197–212. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S, Georges J. Undocumentedness and liminality as health variables. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science. 2003;26(3):185–195. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeigh JD. How do Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) practices affect the mental health of children? The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(1):96–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado AC. New York Times. Op-Ed; New York, NY: 2015. Immigrant Detention Centers Are Inflicting Harm on the Families Inside- And Out. Retrieved June 27, 2016. ( http://nytlive.nytimes.com/womenintheworld/2015/07/06/immigration-detention-centers-are-inflicting-harm-on-the-families-locked-inside/) [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York, NY: Free Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz Sharon, Frost David M. Social Patterning of Stress and Coping: Does Disadvantaged Social Status Confer more Stress and Fewer Coping Resources? Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67(3):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAACP. Criminal Justice Fact Sheet. 2015 Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( http://www.naacp.org/pages/criminal-justice-fact-sheet)

- Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM. The role of migration in the development of depressive symptoms among Latino immigrant parents in the USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS, Landale NS, Hilemeier MM. Family Legal Status and Health: Measurement Dilemmas in Studies of Mexican-Origin Children. Social Science and Medicine. 2015;138:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius P, Zavodny M. How Do E-Verify Mandates Affect Unauthorized Immigrant Workers? Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Research Department. 2014 Working Paper 1403. Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( https://www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/research/papers/2014/wp1403.pdf)

- Pearlin LI. The Sociological Study of Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30(3):241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Aneshensel CS, Leblanc AJ. The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: The case of AIDS caregivers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(3):223–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas R. Huffington Post. New York, NY: 2015. Mothers Launch A Second Hunger Strike at Karnes City Family Detention Center. Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/14/detention-center-hunger-strike_n_7064532.html) [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick S, Chen J, Perreira K. Local-Level Immigration Enforcement and Food Insecurity Risk among Hispanic Immigrant Families with Children: National-Level Evidence. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, Song E, Alonzo J, Downs M, Lawlor E, Martinex O, Sun CJ, O’Brien MC, Reboussin BA, Hall MA. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(2):329–337. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez GR, Vargas ED, Walker HL, Ybarra VD. Stuck between a rock and a hard place: The relationship between Latino/a’s personal connections to immigrants and issue salience and presidential approval. Politics, groups & identities. 2015;3(3):454–468. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2015.1050415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo S, Shaw S, Ingram M, Teufel-Shone N, Carvajal S, Guernsey de Zapien J, Rosales C, Redondo F, Garcia G, Rubio-Goldsmith R. Everyday violence, structural racism and mistreatment at the US-Mexico border. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;109:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Meyer IH. Mental Health Disparities Research: The Impact of Within and Between Group Analyses on Tests of Social Stress Hypotheses. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70(8):1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentell R, Shumway M, Snowden L. Access to Mental Health Treatment by English Language Proficiency and Race/Ethnicity. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(2):289–293. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahshahani AN. ACLU. New York, NY: 2012. Prisoners of Profit: Immigrants and Detention in Georgia. Retrieved June 20, 2016 ( https://www.aclu.org/blog/prisoners-profit-immigrants-and-detention-georgia) [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin DH, Pham Elizabeth, Ngo-Metzger Quyen. Racial and ethnic differences in the mental health needs and access to care of older adults in California. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(12):2311–2317. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Momartin S, Silove D, Coello M, Aroche J, Wei Tay K. Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(7):1149–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Martinez R, Baumer EP, Gertz M. The social context of Latino threat and punitive Latino sentiment. Social Problems. 2015;(2):68–92. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and Health: Major Findings and Policy Implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(S):S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) ICE. Washington, DC: 2014. ICE Deportations: Gender, Age, and Country of Citizenship. Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/350/) [Google Scholar]

- Treadwell N. Fugitive operations and the fourth amendment: representing immigrants arrested in warrantless home raids. North Carolina Law Review. 2010;89(2):507–566. [Google Scholar]

- Turanovic JJ, Rodriguez Nancy, Pratt Travis C. The Collateral Consequences of Incarceration Revisited: A Qualitative Analysis of the Effects on Caregivers of Children of Incarcerated Parents. Criminology. 2012;50(4):913–959. [Google Scholar]

- Turney K. Stress proliferation across generations? Examining the relationship between parental incarceration and childhood health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2014;55(3):302–319. doi: 10.1177/0022146514544173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. Under-age and On the Move. New York, NY: 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2016 ( http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21605886-wave-unaccompanied-children-swamps-debate-over-immigration-under-age-and-move) [Google Scholar]

- Vargas E. Immigration Enforcement and Mixed-Status Families: The Effects of Risk of Deportation on Medicaid Use. Children Youth Services Review. 2015;57:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas E, Pirog M. Mixed Status Families and WIC Uptake. Social Science Quarterly. 2015 doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12286. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;75:2099–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Muller C. Mass Imprisonment and Inequality in Health and Family Life. Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 2012;8(1):11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Schnittker J, Turney K. Despair by Association? The Mental Health of Mothers with Children by Recently Incarcerated Fathers. American Sociological Review. 2012;77(2):216–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley S, Figueroa J, Lauricella T. When does dual identity predict protest? The moderating roles of anti-immigrant policies and opinion-based group identity. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2014;44:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yee V. The New York Times. New York: 2017. Immigrants Hide, Fearing Capture on ‘Any Corner’. Retrieved March 3, 2017 ( https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/us/immigrants-deportation-fears.html?emc=edit_nn_20170226&nl=morning-briefing&nlid=74420988&te=1) [Google Scholar]