Lay Summary

Making changes to one’s physical activity and diet can reduce future risk of developing type 2 diabetes. That being said, making life-long changes to complex behaviors such as diet or physical activity is easier said than done. Text messages can be used to improve long-term diet and physical activity changes; however, it can be difficult to identify what should be said in a text message to nudge those behaviors. To improve utility and reduce cost of sending unnecessary messages, theory should be used in developing text messaging content. The current study used the Behavior Change Wheel to develop a library of text messages that can be used to improve diet and physical activity in individuals who have taken part in an effective community-based diabetes prevention program. The Behavior Change Wheel guides researchers to develop real-world interventions based on evidence and theory. Overall, we created a library of 124 theory-based messages which can be further tested following a diabetes prevention program.

Keywords: Prediabetic state, Text messaging, Health behavior, Healthy lifestyle, Health promotion, Diet, Exercise

Abstract

Improving diet and physical activity (PA) can reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D); however, long-term diet and PA adherence is poor. To impact population-level T2D risk, scalable interventions facilitating behavior change adherence are needed. Text messaging interventions supplementing behavior change interventions can positively influence health behaviors including diet and PA. The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) provides structure to intervention design and has been used extensively in health behavior change interventions. Describe the development process of a bank of text messages targeting dietary and PA adherence following a diabetes prevention program using the BCW. The BCW was used to select the target behavior, barriers and facilitators to engaging in the behavior, and associated behavior change techniques (BCTs). Messages were written to map onto BCTs and were subsequently coded for BCT fidelity. The target behaviors were adherence to diet and PA recommendations. A total of 16 barriers/facilitators and 28 BCTs were selected for inclusion in the messages. One hundred and twenty-four messages were written based on selected BCTs. Following the fidelity check a total of 43 unique BCTs were present in the final bank of messages. This study demonstrates the application of the BCW to guide the development of a bank of text messages for individuals with prediabetes. Results underscore the potential utility of having independent coders for an unbiased expert evaluation of what active components are in use. Future research is needed to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of resulting bank of messages.

Graphical Abstract

Implications Statements.

Practice: Intervention developers can use the steps identified in the current paper when developing theory-based messages.

Policy: Identifying theoretical mechanisms for SMS interventions will allow for the synthesis of intervention findings and more effective and efficient public health initiatives.

Research: The bank of theory-based messages developed in this paper should be tested in future research.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a common and, in some cases, preventable condition which can negatively impact the individual diagnosed and society as a whole through reduced employment rates and increased cost on the healthcare system [1, 2]. Diabetes prevention programs have found that through behavior modifications to diet and physical activity, more than half of T2D cases can be prevented [3–5]. While the benefits of diet and physical activity behavior change interventions are well documented, adherence to daily food and physical activity guidelines are poor [6, 7]. For example, in the year following a structured diabetes prevention program participants’ physical activity has been shown to decrease by 50%, and within five years return back to baseline levels of inactivity [8]. With the rising rate of diabetes, its associated costs, and the issues relating to long-term behavior change adherence, there is a need for low-cost, easily deployable interventions to help decrease the prevalence of T2D.

With the widespread dispersion of mobile phone technologies, text messaging has become an accepted mode of communication. The low overhead costs and minimal time commitment associated with text messaging [9–13] may prove useful in supplementing behavior change interventions and improving adherence following an intervention. In fact, mobile phone text messaging has been shown to improve health behaviors such as weight loss, diet, and physical activity [11, 14–17]. In order to develop scalable, effective, and efficient text messaging interventions, researchers must provide a conceptual model which clearly identifies what components are included and how these components will theoretically influence the target behavior [18]. Once these components are specified, further research is needed to determine what combination and dose of messaging can optimally influence behaviors. Despite the rise in text messaging used within research and the call for theory-driven interventions, current text messaging interventions often fail to report on the theoretical underpinning for their message development [19, 20]. With the sparsity of theory use in published literature, coupled with the lack of guidance on how to appraise and select the most appropriate theory, and the sheer number of behavior change theories, many interventionists are not well equipped in theory selection and implementation [21, 22].

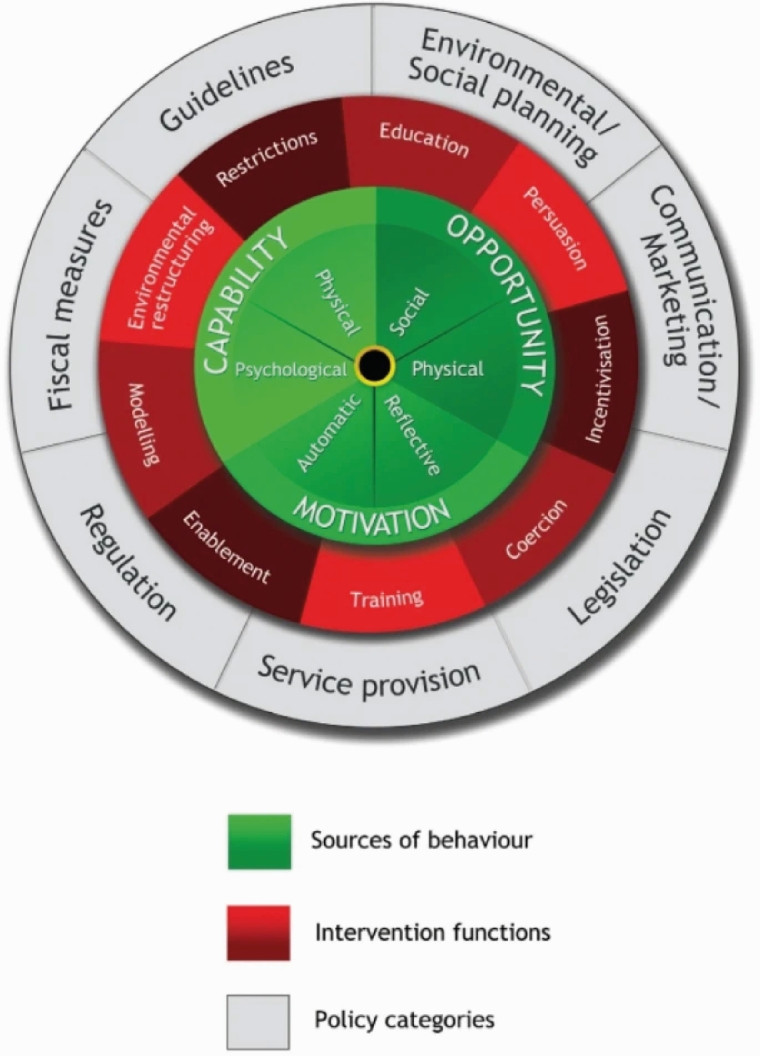

One approach to addressing the plethora of theories and lack of guidance in how to choose the right theory to target mechanisms of action is to use the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW). The BCW is a synthesis of 19 behavior change frameworks [23] which has been used to design a wealth of behavior change interventions [24–28]. Developed using expert consensus and validation, the BCW prompts researchers to fully understand the behavior they want to change prior to designing an intervention. Specifically, researchers can use the BCW to systematically consider the full range of intervention options and select behavior change techniques (BCTs) which are likely to be effective. The wheel is comprised of three layers: the COM-B model at the hub, surrounded by intervention functions, then policy options (Figure 1).

Fig 1 |.

The Behavior Change Wheel. Reproduced with permission from Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014) The Behavior Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. www.behaviorchangewheel.com.

At the core of the BCW is the COM-B model, which is used to begin the process of analyzing the behavioral antecedents that can be targeted in an intervention. The COM-B model describes three different categories which interact to influence behavior, namely capability, opportunity and motivation. Researchers can use the COM-B model to decide whether greater capability (physical and psychological), more opportunity (social and physical), stronger motivation (automatic and reflective), or a combination is needed to change the target behavior. This behavioral analysis can be expanded through use of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) which describes 14 domains from 33 behavior change theories which can expand on the COM-B components of capability, opportunity, and motivation [29]. Using the COM-B model in combination with the TDF can allow for a more thorough, theory-informed analysis of the antecedents potentially influencing behaviors.

The second layer of the BCW consists of nine intervention functions that can be used to influence a behavior. These intervention functions have been linked to a taxonomy of 93 BCTs (BCCTTv1) [30]. Selection of appropriate BCTs can be used to target the constructs identified as influencing the target behavior. BCTs are considered the smallest, replicable, and observable components, or “active components”, within an intervention designed to change a behavior. Lastly, the third layer of the BCW is the outer layer of seven policy categories. Policy categories are the ways in which the selected intervention functions can be delivered within an intervention. Using the BCW allows for systematic and structured development of complex behavioral interventions and improves subsequent implementation and evaluation.

The current paper aims to outline the development process of a bank of text messages, guided by the BCW, for individuals at risk for developing T2D who have completed the supervised portion of a diabetes prevention program; [Small Steps for Big Changes]([SSBC]). [SSBC] was designed to help empower individuals to make positive diet and physical activity changes to reduce their risk of developing T2D. [SSBC] was systematically developed and went through a rigorous and iterative process from pilot testing [31] to a randomized trial [32] and is now being implemented as an effectiveness trial in two [locations blinded] [33]. Individuals in the [SSBC] program meet with a trained coach for six one-on-one sessions over three weeks to discuss specific topics and to be shown aerobic exercise routines. Following the completion of the three-week program, [SSBC] participants are asked to continue to implement the strategies and changes that they have learned without any formal continued support or engagement from their coach. Participant feedback was sought to evaluate and improve the program and they expressed the desire for more support after the three-week program [34,35]. The bank of messages developed in the current paper will be further tested following the three-week program period to assess their impact on diet and physical activity adherence and this evaluation will be reported elsewhere.

Methods

Through application of the BCW, the current paper describes the systematic development of a bank of theory-informed text messages to support adherence to changes made throughout the [SSBC] program in individuals at risk for developing T2D. The application of the BCW was completed by one author (MM) and reviewed and discussed by three other authors (KC, SL, MJ). The BCW is broadly split into three stages: (i) understanding the behavior; (ii) identification of intervention options; and (iii) identification of content and implementation options. Due to the high mobile phone ownership and the ubiquity of text messaging as a means of communication, coupled with the available literature identifying text messaging as an effective, scalable, and low-cost tool to promote behavior change adherence [11], text messaging was selected by the authors as the implementation option or mode of delivery at the onset of intervention design. See Table 1 for an overview of the methods implemented in the current paper.

Table 1 |.

Overview of methods used in the current paper.

| Step | Tasks |

|---|---|

| 1. Behavioral diagnosis | • Identify what behavior needs to change |

| • Define the target behavior | |

| • Identify barriers and facilitators to engage in the behavior | |

| • Map barriers and facilitators onto COM-Ba and TDFb | |

| 2. Identification of intervention options and policy categories | • Select relevant intervention functions and policy categories |

| • Narrow down intervention functions and policy categories using APEASEc criteria | |

| 3. Identification of content | • Through BCWd matrices and the literature, identify all relevant BCTse to target intervention functions |

| • Narrow down BCTs using APEASE criteria | |

| 4. Message development | • Write text messages based on identified BCTs |

| • Edit messages to improve clarity | |

| • Back code messages to ensure fidelity of BCTs used in messages |

aCOM-B = Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behavior; bTDF = Theoretical Domains Framework; cAPEASE = Affordability, Practicability, Effectiveness/cost, Acceptability, Side-effects/Safety, and Equity; dBCW = Behavior Change Wheel; eBCTs = Behavior Change Techniques

Understand the Behavior: Behavioral Diagnosis

Prior to writing text messages, the problem was identified and defined in behavioral terms (i.e., a behavioral diagnosis describing what is the problem behavior, where does it occur and who performs it). Once a target behavior was defined, all other possible behaviors that could be targeted within a text messaging intervention for individuals at risk for developing T2D were considered and detailed (including who needs to perform the behavior, what they must do differently, when, where, how, and with whom). Following this, barriers and facilitators to individual’s capability, opportunity, and motivation for engaging in these behaviors were explored through previous qualitative studies with [SSBC] participants and trainers [34, 35]. Barriers and facilitators were mapped onto the COM-B and TDF to identify which specific components can be targeted as potential levers of behavior change within a text messaging intervention.

Identify Intervention Options

Upon completion of the behavioral diagnosis, the intervention functions and policy categories likely to elicit change within these COM-B and TDF domains were determined. This stage started with the selection of appropriate intervention functions (i.e., education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modeling, and enablement). Decision making at this stage was informed by the matrices within the BCW framework which links COM-B and TDF domains to intervention functions [23]. These intervention functions were narrowed down through use of the APEASE (Affordability, Practicability, Effectiveness/cost, Acceptability, Side-effects/Safety, and Equity) criteria. The APEASE criteria was developed to assist individuals in designing and evaluating interventions to determine what intervention functions, policy categories, and BCTs might be most appropriate for inclusion within the intervention [23]. Once intervention functions were selected, the matrix linking these functions to policy categories within the BCW was used to determine what policy categories (communication/marketing, guidelines, fiscal measures, regulation, legislation, environmental/social planning, and service provision) were most appropriate. The APEASE criteria was again used to narrow down this selection.

Identify Content

After identifying the relevant intervention functions, we determined which BCTs best serve the intervention functions through a text messaging intervention. Matrices within the BCW framework were used to guide decisions on which BCTs link to the selected intervention functions [23]. Additionally, to ensure that a comprehensive list of possible BCTs was identified, previous reviews of the literature as well as the BCTs used in the [SSBC] intervention framework [36] were referenced.

Once a list of all possibly relevant BCTs was compiled, it was assessed using APEASE criteria and the resulting BCTs were used to guide the message content development. The following questions were used to guide the selection process of BCTs in consideration of the APEASE criteria: can it be delivered within an acceptable budget; can it be delivered as designed and to scale (i.e., can we write a message reflective of the [SSBC] counseling style and content); will this be effective and is it worth the cost (i.e., will it be effective in promoting diet and physical activity adherence in individuals at risk for developing T2D); is it judged as relevant and engaging to participants (note acceptability will be further tested after the bank of messages is written in a follow-up study); and will it reduce or increase disparities in health/wellbeing/standard of living? This stage ultimately resulted in a final set of BCTs suitable for use in a text messaging intervention.

Message Development

A bank of text messages designed to promote diet and physical activity adherence following the [SSBC] diabetes prevention program was developed. The messages were designed as one-way interactions to decrease the cost and complexity of the intervention. Message development was guided by the previously identified BCTs in addition to the motivational interviewing counseling style and language used within the [Small Steps for Big Changes]([SSBC]) diabetes prevention program [36]. Messages were drafted by KC and MM (who were trained in BCT identification) and reviewed by MJ and SL, behavior change researchers who have expertise in the delivery of a diabetes prevention program. Messages were limited to 160 characters (maximum number of characters allowable for the majority of mobile phones). This decision was made to increase the reach of these messages to any individual with a cell phone, as requiring smartphone ownership has been shown to increase health disparities [37]. Language within the messages was designed to be as simple and clear as possible, avoiding use of jargon and acronyms, as an attempt to minimize any possible ambiguity.

Once written, messages were evaluated for literary demands using the Flesch-Kincaid grade level test and any message above an eighth-grade reading level were edited. This level of readability was chosen as it is a recommended maximum reading level for adults [38]. Following this step, messages were professionally edited to ensure readability and then coded by JB, an independent reviewer trained in BCT identification who was not involved in message creation and who had not seen any messages prior to coding to ensure the fidelity of BCTs used in the messages. Once coded, two authors, JB and MM met to discuss any discrepancies between the original BCTs in which the messages were based and determined consensus on which BCTs are present in the final bank.

Results

Understanding the behavior

Within the [SSBC] diabetes prevention program, qualitative research aimed at understanding participant and trainers’ perceptions regarding successes and challenges of program delivery highlighted a main concern in regard to program length [35]. Mainly, participants want continued accountability from program coaches beyond the three-week program. Through this work [35] and the existing literature [6, 7, 39], we identified that adherence to dietary and physical activity recommendations are key behavioral targets for the messages. More specifically, the physical activity target behavior included: (i) participation in self-directed home- (or gym- for those participants which continued with a gym membership) based physical activity to meet recommended Canadian guidelines of at least 150 minutes per week; and the dietary target behaviors included: (ii) decrease added sugar consumption to below 24 grams for women and 36 grams per day for men as per The American Heart Association recommendations [40]; and (iii) increase vegetable intake as per the MyPlate model [41]. While physical activity guidelines also discuss the importance of muscle strengthening activities and the MyPlate model provides several recommendations relating to a healthy diet [41], we chose to focus on 150 minutes of activity and vegetable intake as these specific recommendations align with diabetes prevention strategies present in [SSBC].

Next, 16 barriers and facilitators to the behaviors were selected from previous research profiling past [SSBC] participants perceived physical activity journey in the 1-year following the structured program [34] as well as their overall insights into the program as a whole [35]. Barriers to continual engagement in diet and physical activity included low self-efficacy, lack of motivation, and lack of time. Facilitators included strong self-efficacy, support from social networks, use of external tools (such as self-monitoring devices), reframing of outcome goals (health instead of physical appearance), high motivation, and sufficient knowledge. While these barriers/facilitators are specific to the [SSBC] diabetes prevention program, they are also commonly cited within the broad literature regarding physical activity engagement for those at risk for developing or recently diagnosed with T2D [42–46].

To further analyze the target behavior and inform the intervention design, barriers and facilitators were categorized into domains within the COM-B and TDF by one author (MM) and reviewed by three remaining authors (KC, SL, MJ) (see Supplementary file 1). This step resulted in the COM-B categories of psychological capability (31% of barriers/facilitators), reflective motivation (19%) and automatic motivation (19%) identified as key domains requiring change to support behavior change in the current context.

Identifying Intervention Options

All nine intervention functions and seven policy categories were identified as possibly relevant for the given barriers and facilitators relevant to this diabetes prevention program. Each of these candidate intervention options were considered using the APEASE criteria. A total of six intervention functions (education, persuasion, training, incentivization, environmental restructuring, and enablement) were identified as appropriate for inclusion in a text messaging intervention for individuals at risk for developing T2D. The remaining intervention functions were excluded because they were either inconsistent with the overall content and counseling style used within the [SSBC] program (restriction and coercion) or they are unable to be incorporated in a message of less than 160 characters (modeling). The selected intervention functions were added to the BCT intervention mapping tables (supplementary file 1). One policy category (communication/marketing) was identified as appropriate for inclusion. The remaining policy categories (guidelines, environmental/social planning, legislation, service provision, regulation, and fiscal measures) were excluded because they are not practicable in the given context (i.e., these categories could not be targeting through the intended delivery means to the target population).

Identifying Content

BCTs appropriate for each intervention function can be found in the BCW [23]. The selected intervention functions are associated with ~90% of the BCTs within the BCTTv1. In order to systematically decide which of these BCTs are most likely to result in changes for the target behaviors, current reviews of the literature were considered. Specifically, systematic reviews addressing BCTs within diet and/or physical activity interventions for populations with or at risk for developing T2D were examined [47–54]. Where applicable, BCTs reported in the CALO-RE taxonomy [55] were mapped onto the BCTTv1 by two authors (MM & KC). Additionally, any BCTs which are currently used within the [SSBC] intervention [36] which were not noted in these previous reviews were also assessed. This resulted in a total of 60 BCTs which were then assessed using APEASE criteria. Thirty-two BCTs were removed after being evaluated with APEASE (see Figure 2). This process resulted in a total of 28 BCTs to address the identified barriers and facilitators within the message content. These selected BCTs were added to the BCW mapping tables (see supplementary file 1).

Fig 2 |.

Diagram of BCTs identified in the literature and screened for inclusion.

Message Development

KC and MM wrote the messages based on the 28 BCTs identified in the previous stage. An initial bank of 124 messages were written (evenly split into physical activity, diet, and messages which pertain to both physical activity and diet). All messages were written to correspond to a single BCT. Sixty messages were edited to maintain a reading level no higher than the eighth grade resulting in an average reading level of 5.6 (ranging from 0.5 – 7.9). All 124 messages were professionally edited by a communication specialist. These changes were comprised mostly of slight wording changes and punctuation in an attempt to simplify message content and enhance the spirit of engagement and support.

BCT Fidelity Coding

Following BCT coding by JB, a consensus meeting took place between JB and MM to determine the final BCT composition of the messages. A total of 26 messages (21%) did not retain their originally intended BCT. Of the 98 messages (79%) which retained their originally intended BCT, 34 were also coded as having additional BCTs present. Of the 26 which did not retain their original code, 17 were re-coded with at least 1 BCT within the same category (see Table 2).

Table 2 |.

Overview of behavior change technique alterations resulting from the fidelity check.

| Message | Original BCT | Final BCTs |

|---|---|---|

| Think about what goal you can set to get some exercise today. | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Goal setting – outcome (1.3) |

| Make a goal to get some physical activity this week. | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Goal setting – outcome (1.3) |

| Some people like to make small goals; think about what a good exercise plan for you would be this week. | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Goal setting – outcome (1.3) |

| Exercising while on vacation is hard! Think about ways you can be physically active while on vacation. | Problem solving (1.2) | Action planning (1.4) |

| Sometimes we need the support of others to help us stick to our goals. Think about who in your life can help you stick to your exercise plan. | Social support – emotional (3.3) | Social support – unspecified (3.1) |

| Exercising with a buddy can give you motivation and support - and can be a nice distraction! | Social support – emotional (3.3) | Social support – practical (3.2); 12.4 |

| Scheduling your exercise sessions like an appointment can help you stay on track and get your workouts in! | Information about antecedents (4.2) | Action planning (1.4); Prompts/cues (7.1) |

| Pay attention to how you’re feeling during exercise so that you know how hard you’re working. | Information about antecedents (4.2) | Monitoring of emotional consequences (5.4) |

| For some people, regular exercise can decrease stress and improve their mood. | Reduce negative emotions (11.2) | Information about emotional consequences (5.6) |

| Need a distraction to get through your exercise session? Try exercising while listening to music or with a buddy. | Reduce negative emotions (11.2) | Restructuring the physical environment (12.1); Restructuring the social environment (12.2); Distraction (12.4) |

| Try putting your running shoes and workout clothes on the kitchen counter. This can serve as a reminder to get your exercise in! | Restructuring the physical environment (12.1) | Prompts/cues (7.1) |

| Each day, reward another step towards your goals. Today, reward yourself for exercising. Tomorrow, reward yourself for reaching your target heart rate! | Reward completion (14.5) | Non-specific reward (10.3); Self-reward (10.9); Reward approximation (14.4) |

| You’ve shown yourself that you can integrate exercise into your daily routine. Keep up the great work! | Verbal persuasion about capability (15.1) | Social support – unspecified (3.1); Focus on past success (15.3) |

| Think about all the positive benefits you will get during your next workout! | Self-talk (15.4) | Vicarious consequences (16.2) |

| Think about ways you can cut out some added sugar from your diet. | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Goal setting – outcome (1.3) |

| Think about what small changes you can make to your diet this week. | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Goal setting – outcome (1.3) |

| Think about what you will do when you’re craving refined carbs or sugar. | Action planning (1.4) | Problem solving (1.2) |

| Having people who support us is important! Think about who in your life can help you stick to your food goals. | Social support – emotional (3.3) | Social support – unspecified (3.1) |

| Continue tracking your food! Tracking your food can help you stay mindful of what you are putting in your body. | Information about antecedents (4.2) | Self-monitoring of behavior (2.3) |

| Each day, reward another step towards your goals. Today, reward yourself for eating healthy. Tomorrow, reward yourself for cooking that healthy meal! | Reward completion (14.5) | Non-specific reward (10.3); Self-reward (10.9); Reward approximation (14.4) |

| Your first plan will not work 100% of the time. Continue to change your goals until you find what works best for you! | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Review outcome goals (1.7) |

| Some people prefer to make small changes to either diet or exercise. Think about a plan that would work for you this week. | Goal setting – behavior (1.1) | Action planning (1.4) |

| Maintaining healthy behavior can be challenging. Many people find it helpful to share this journey with a close friend. | Social support – emotional (3.3) | Social support – unspecified (3.1) |

| Reminders can be super helpful when we are trying to form new habits. Put a reminder in your phone, a note on your fridge, or get creative! | Habit formation (8.3) | Prompts/cues (7.1) |

| Don’t forget to reward yourself for the progress you’ve made in achieving your goals! | Self-incentive (10.7) | Non-specific reward (10.3); Self-reward (10.9); Reward approximation (14.4) |

| Take a moment to think about all the hard work you’ve put in. You are becoming a healthier you! | Self-reward (10.9) | Social support – unspecified (3.1); Focus on past success (15.3) |

As a result of this fidelity check, a total of 43 unique BCTs were found in the bank of 124 messages, including the addition of 17 BCTs. Of the 17 additional BCTs found within the bank of messages (see Figure 3), five BCTs (4.4, 5.2, 5.6, 11.3, 16.2) were not initially assessed using the APEASE criteria as they were not identified as commonly used BCTs within the literature or within the [SSBC] program [36], five BCTs (5.3, 10.3, 10.6, 12.2, 12.3) were originally conceptualized by MM and KC as not within the scope or in keeping with the language used in [SSBC], and seven BCTs (1.3, 1.7, 3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 5.4, 8.1) were initially believed to be unsuitable for delivery within a text messaging intervention without tailoring to a specific participant or having 2-way communications. For example, BCT 4.1 (instruction on how to perform the behavior) was originally excluded as MM and KC believed that this would be challenging to provide instructions which regarding behaviors that were acceptable or generalizable to all participants. However, the message “Canadian guidelines encourage us to get at least 150 minutes of exercise per week. You can do it!” which was written to fit within BCT 9.1 (credible source) was coded by an unbiased reviewer to also include BCT 4.1. See supplementary file 2 for final bank of messages and corresponding BCTs. Overall, this stage resulted in 124 theoretically based text messages suitable for individuals at risk of developing T2D.

Fig 3 |.

Final bank of messages coded by a blind reviewer for BCTs and discrepancies from original codes.

Discussion

Use of text messages as an intervention supplement following a diabetes prevention program may be a cost-effective way to promote adherence to lifestyle modifications made during the program. Anja and colleagues [1] speculate that a population-level intervention (small impact and large reach such as text message interventions) resulting in a 5% decrease in body weight would lessen the incidence of T2D in their 10-year prediction (between 2012 and 2022) resulting in savings of approximately $2 billion. However, the majority of mobile phone text message interventions report outcomes and provide little to no detail regarding the processes utilized to develop their message content. In many interventions, it is unclear whether content was developed ad hoc, whether it was informed by behavior change theory or, whether theoretical frameworks were used. The current paper outlined the systematic process used to develop a bank of text messages targeting diet and physical activity behaviors among individuals at risk for developing T2D. While other papers have cited the use of the BCW in the development of text messaging interventions [56], none have added in the final step included in this paper of having an independent coder assess BCTs within the final intervention components as a fidelity check. Traditionally, resources are focused on evaluating the effectiveness of interventions and there has been a call for increased investment in intervention development, fidelity, and understanding how interventions work [57, 58]. The Medical Research Council specifies that assessment of fidelity is important at all stages of an intervention from development to evaluation and implementation [59]. The consideration of intervention fidelity within the current work, done at the initial stage of development is an important step for future researchers to take to specify the core components of an intervention and link those components to theoretical mechanisms. This study resulted in the identification of 43 potential BCTs and 124 messages that can now be tested to determine their effect on diet and physical activity adherence in individual at risk for developing T2D.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of the BCW guided the development of this bank of messages systematically considered the full range of intervention options and guided the selection of the most promising approaches for achieving the desired changes. Application of the BCW allowed for the transparent and rigorous reporting of the current bank of text messages; this is essential for future evidence synthesis to determine which BCTs implemented via text messaging may be most influential in changing behaviors.

Additionally, the current paper took an additional step of having an independent coder identify the BCTs in the final bank of messages to demonstrate fidelity. This additional step resulted in the identification of an additional 17 BCTs that were either not identified within the literature or originally thought to be infeasible within one-way messaging. Further, 27 messages within the bank did not retain the originally intended BCT. While researchers may develop an intervention with the intention of using a certain set of active components, this work highlights that an unbiased coder not involved in the intervention development can independently code the intervention content to provide an impartial expert evaluation of what active components are in use. This is a key step because of the nuances within the BCT codes. In the current bank of messages, 27 did not retain their original BCT; however, majority of these messages were still written in a manner which was consistent with the original intent as they were coded within the same BCT category. For example, seven messages were originally written with the intent to prompt behavioral goal setting; however, in order to remain broad enough to be applicable to many participants within a one-way message, these messages did not specify behaviors and thus were coded as BCT 1.4 (goal setting outcome) instead of BCT 1.1 (goal setting behavior). Having an impartial reviewer allowed for content to be assessed not on what those developing intended but on what is actually present.

While the current paper highlights the application of the BCW even when the mode of delivery is decided on at the outset, a limitation remains in that the population of interest may have chosen a differing mode of communication if given the option (e.g., face-to-face follow-up visits). Despite this limitation, the current paper provides an example of how the BCW can be applied specifically to the development of messages and future researchers can follow this example in applying the BCW to different stages of intervention development.

Another limitation was that the identified barriers/facilitators were pulled from qualitative research from [SSBC] participants and coaches [34, 35] and, as with all qualitative inquiry, was not designed to result in generalizable findings. This may introduce bias and the identified barriers/facilitators might not be representative of other’s perspectives. That being said, the barriers identified within the current study are mirrored in the broader research, so while we cannot be certain these views are representative of all participants in the current diabetes prevention program, these views are likely representative of diet and physical activity programs as a whole for individuals with or at risk for developing T2D [42–46]. Given this broad representativeness of barriers and facilitators and the non-program specific nature of the text messaging content, the current bank of messages could be utilized not only in the [SSBC] diabetes prevention program, but other programs as well.

Future Research

We intend to evaluate the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of this bank of text messages to support diet and physical activity adherence following the [SSBC] diabetes prevention program. The next phase of this research will be to test the acceptability and feasibility of implementing these messages in the [SSBC] context. This further evaluation of message acceptability will be necessary to tailor this bank of messages to the [SSBC] population.

In addition to content components (BCTs), the delivery components (timing and frequency) of text messages should also be tested and tailored to the population. Future research could use an optimization design to address which combination of BCTs may be most effective in behavior change, but also what dose of messaging can optimally influence behaviors. Following future optimization and effectiveness testing, the current bank of messages may provide an easily scalable, cost-effective solution to support long-term diet and physical activity adherence following the structured [SSBC] program.

Additionally, this bank of messages was written to broadly support diet and physical activity adherence and may be broadly applicable for individuals at risk for developing T2D, or for individuals with overweight and obesity. Future research could tailor this bank of theoretically developed text messages to be appropriate and suitable for specific programs.

Conclusions

While it is unclear as to the extent that the application of the BCW will result in dietary and physical activity behavior changes, the coding of the BCTs and additional fidelity check used in the current paper will improve replicability and aid in the future evaluation of this bank of text messages. This study provides an example of how the BCW was used to develop a bank of theory-based text messages intended to improve diet and physical activity adherence. Specifically, this application of the BCW resulted in the development of 124 theory-based messages using 43 BCTs specifically selected to address known barriers and facilitators to diet and physical activity adherence. The bank of messages provided in this paper can be further tested by not only the [SSBC] diabetes prevention program, but other diet and physical activity programs as well. By reporting on the theoretical underpinnings and mechanisms of action within text messages, future research can understand not only if text messages are effective in enacting behavior change, but also why certain messages may be more or less effective, and what combination and dose of messages can optimally influence behavior change.

Supplementary Material

Funding: This research is supported with funds from the WorkSafeBC research program (RS2018-TG04), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#333266; #143267; #133581), and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (#5917).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency Statement: This study was not formally registered. The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered.

Data Availability: De-identified data from this study are not available in an a public archive. De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author. There is not analytic code associated with this study. Materials used to conduct the study are not publically available.

References

- 1. Anja B, Laura R. The cost of diabetes in Canada over 10 years: applying attributable health care costs to a diabetes incidence prediction model. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can Res Policy Pract. 2017;37:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tunceli K, Bradley CJ, Nerenz D, Williams LK, Pladevall M, Elston Lafata J. The impact of diabetes on employment and work productivity. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2662–2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371(9626):1783–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindström J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, et al. ; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group . The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3230–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colley RC, Garriguet D, Janssen I, Craig CL, Clarke J, Tremblay MS. Physical activity of Canadian adults: accelerometer results from the 2007 to 2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep. 2011;22(1):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haack SA, Byker CJ. Recent population adherence to and knowledge of United States federal nutrition guides, 1992-2013: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2014;72(10):613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diabetes Prevention Program. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009;374:1677–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Car J, Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at scheduled healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; (4). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hall AK, Cole-Lewis H, Bernhardt JM. Mobile text messaging for health: a systematic review of reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:393–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Junod Perron N, Dao MD, Righini NC, et al. Text-messaging versus telephone reminders to reduce missed appointments in an academic primary care clinic: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shaw R, Bosworth H. Short message service (SMS) text messaging as an intervention medium for weight loss: a literature review. Health Inform J. 2012;18(4):235–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Armanasco AA, Miller YD, Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL. Preventive health behavior change text message interventions: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Leon E, Fuentes LW, Cohen JE. Characterizing periodic messaging interventions across health behaviors and media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith DM, Duque L, Huffman JC, Healy BC, Celano CM. Text message interventions for physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(1):142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Collins LM. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). Springer: Springer International Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arambepola C, Ricci-Cabello I, Manikavasagam P, Roberts N, French DP, Farmer A. The impact of automated brief messages promoting lifestyle changes delivered via mobile devices to people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(4):e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sahin C, Courtney KL, Naylor PJ, E Rhodes R. Tailored mobile text messaging interventions targeting type 2 diabetes self-management: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Digit Health. 2019;5:2055207619845279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A; “Psychological Theory” Group . Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michie S. Designing and implementing behaviour change interventions to improve population health. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13 Suppl 3:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michie S, Atkins L, West R.. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fahim C, Acai A, McConnell MM, Wright FC, Sonnadara RR, Simunovic M. Use of the theoretical domains framework and behaviour change wheel to develop a novel intervention to improve the quality of multidisciplinary cancer conference decision-making. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fulton EA, Brown KE, Kwah KL, Wild S. StopApp: using the behaviour change wheel to develop an app to increase uptake and attendance at NHS Stop Smoking Services. in: Healthcare. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 2016;4(2):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gould GS, Bar-Zeev Y, Bovill M, et al. Designing an implementation intervention with the Behaviour Change Wheel for health provider smoking cessation care for Australian Indigenous pregnant women. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Munir F, Biddle SJH, Davies MJ, et al. Stand More AT Work (SMArT Work): using the behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to reduce sitting time in the workplace. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robinson H, Hill E, Direito A, et al. Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to develop an intervention to promote physical activity following pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. Paper presented at: Behav. Sci. Public Health Conf. Ed. 2019, vol. 3, Behavioural Science and Public Health Network; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Locke SR, Bourne JE, Beauchamp MR, et al. High-intensity interval or continuous moderate exercise: a 24-week pilot trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(10):2067–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jung ME, Locke SR, Bourne JE, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and accelerometer-determined physical activity following one year of free-living high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training: a randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bean C, Dineen T, Locke SR, Bouvier B, Jung ME. An evaluation of reach and effectiveness of a diabetes prevention behaviour change program situated in a community site. Can J Diabetes 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bean C, Dineen T, Jung ME. “It’sa life thing, not a few months thing”: profiling patterns of the physical activity change process and associated strategies of women with prediabetes over 1-year. Can J Diabetes 2020; 44(8): 701– 710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dineen T, Bean C, Jung M. Successes and challenges from multiple perspectives on a diabetes prevention program situated in the community. TSO Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. MacPherson MM, Dineen TE, Cranston KD, Jung ME. Identifying behaviour change techniques and motivational interviewing techniques in small steps for big changes: A community-based program for adults at risk for type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes 2020; 44(8): 719– 726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bommakanti KK, Smith LL, Liu L, et al. Requiring smartphone ownership for mHealth interventions: who could be left out? BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schilling L, Bennett G, Bull S, Kempe A, Wretling M, Staton E. Text Messaging in Healthcare Research Toolkit. Center for Research in Implementation Science and Prevention (CRISP), University of Colorado School of Medicine, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Long-term effects of the Diabetes Prevention Program interventions on cardiovascular risk factors: a report from the DPP Outcomes Study. Diabet Med 2013;30:46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Added Sugars. Available at https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/added-sugars#:~:text=The%20American%20Heart%20Association%20(AHA,day%2C%20or%20about%209%20teaspoons. Accessibility verified December 14, 2020.

- 41. Canada H. Welcome to Canada’s food guide 2018. Available at https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/, https://food-guide.canada.ca/. Accessibility verified September 3, 2020.

- 42. Alharbi M, Gallagher R, Neubeck L, et al. Exercise barriers and the relationship to self-efficacy for exercise over 12 months of a lifestyle-change program for people with heart disease and/or diabetes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16(4):309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Booth AO, Lowis C, Dean M, Hunter SJ, McKinley MC. Diet and physical activity in the self-management of type 2 diabetes: barriers and facilitators identified by patients and health professionals. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013;14(3):293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kullgren JT, Knaus M, Jenkins KR, Heisler M. Mixed methods study of engagement in behaviors to prevent type 2 diabetes among employees with pre-diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4(1):e000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nor NM, Shukri NAM, Yassin NQAM, Sidek S, Azahari N. Barriers and enablers to make lifestyle changes among type 2 diabetes patients: a review. Sains Malays. 2019;48:1491–502. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thomas N, Alder E, Leese GP. Barriers to physical activity in patients with diabetes. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(943):287–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cradock KA, ÓLaighin G, Finucane FM, et al. Diet behavior change techniques in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(12):1800–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. ; IMAGE Study Group . Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Job JR, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG, Reeves MM. Effectiveness of extended contact interventions for weight management delivered via text messaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2018;19(4):538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28(6):690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, Atkinson L, Turner A, French DP. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals’ physical activity self-efficacy and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Samdal GB, Eide GE, Barth T, Williams G, Meland E. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Van Rhoon L, Byrne M, Morrissey E, Murphy J, McSharry J. A systematic review of the behaviour change techniques and digital features in technology-driven type 2 diabetes prevention interventions. Digit Health. 2020;6:2055207620914427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Williams SL, French DP. What are the most effective intervention techniques for changing physical activity self-efficacy and physical activity behaviour–and are they the same? Health Educ Res. 2011;26(2):308–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26(11):1479–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nelligan RK, Hinman RS, Atkins L, Bennell KL. A short message service intervention to support adherence to home-based strengthening exercise for people with knee osteoarthritis: intervention design applying the Behavior Change Wheel. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(10):e14619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toomey E, Hardeman W, Hankonen N, et al. Focusing on fidelity: narrative review and recommendations for improving intervention fidelity within trials of health behaviour change interventions. Health Psychol Behav Med 2020;8:132–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M; Medical Research Council Guidance . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.