Abstract

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a life-altering injury that leads to a complex constellation of changes in an individual’s sensory, motor, and autonomic function which is largely determined by the level and severity of cord impairment. Available SCI-specific clinical practice guidelines (CPG) address specific impairments, health conditions or a segment of the care continuum, however, fail to address all the important clinical questions arising throughout an individual’s care journey. To address this gap, an interprofessional panel of experts in SCI convened to develop the Canadian Spinal Cord Injury Best Practice (Can-SCIP) Guideline. This article provides an overview of the methods underpinning the Can-SCIP Guideline process.

Methods

The Can-SCIP Guideline was developed using the Guidelines Adaptation Cycle. A comprehensive search for existing SCI-specific CPGs was conducted. The quality of eligible CPGs was evaluated using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument. An expert panel (n = 52) convened, and groups of relevant experts met to review and recommend adoption or refinement of existing recommendations or develop new recommendations based on evidence from systematic reviews conducted by the Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE) team. The expert panel voted to approve selected recommendations using an online survey tool.

Results

The Can-SCIP Guideline includes 585 total recommendations from 41 guidelines, 96 recommendations that pertain to the Components of the Ideal SCI Care System section, and 489 recommendations that pertain to the Management of Secondary Health Conditions section. Most recommendations (n = 281, 48%) were adopted from existing guidelines without revision, 215 (36.8%) recommendations were revised for application in a Canadian context, and 89 recommendations (15.2%) were created de novo.

Conclusion

The Can-SCIP Guideline is the first living comprehensive guideline for adults with SCI in Canada across the care continuum.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Clinical practice guidelines, Evidence-based practice, Knowledge translation

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a life-altering injury that leads to complex changes in sensory, motor, and autonomic function, significantly affecting an individual’s emotional wellbeing, quality of life, community participation, functional abilities, health and life expectancy.1–5 Specialized acute, rehabilitation, and community-based healthcare that necessitates the provision of the best available interprofessional care from time of injury onset and throughout the balance of the individual’s lifetime is required. Further, challenges within the field of SCI internationally include: ongoing difficulties in funding and accruing an adequate sample size within clinical trials, hampering the ability to generate Level I evidence to meet regulatory requirements and inform practice.6,7 A concern within healthcare settings is the underutilization of research by healthcare professionals8 and the clinical equipoise regarding how best to diagnose or treat patients with complex biopsychosocial issues and medical morbidity such as individuals living with SCI.

Although there is a large and expanding body of clinical research directed toward improving patient care, thirty to forty percent of patients do not receive appropriate evidence-based care.9,10 As the volume of research evidence is rapidly increasing, it is challenging for healthcare professionals to remain informed on the latest research and related clinical recommendations across care domains.8 Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) play an important role in bridging this knowledge gap. CPGs are knowledge tools that assist evidence-based decision-making and are comprised of systematically developed statements that promote high-quality practice across the continuum of care. Evidence-informed practice recommendations within CPGs can reduce practice variation, improve the quality of care, and assist healthcare professionals in making clinical decisions based on evidence and advancing practice.11–13

Within the field of SCI research, existing CPGs focus on specific individual impairments (i.e. skin integrity, bowel management) or a single segment of the care continuum (i.e. prehospital care, MRI diagnosis, surgical intervention, community participation) and do not address all the important clinical questions which arise for individuals throughout an individual’s care journey. Furthermore, few guidelines provide recommendations for all members of the interprofessional care team that are tailored to the individual’s level of injury and severity of injury (i.e. American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale, AIS). A CPG that identifies best practices across the entire SCI care continuum is needed.

CPGs with the greatest potential to influence systems of care, in addition to quality care recommendations, should contain recommendations tailored for specific stakeholders including but not limited to healthcare administrators, policymakers and individuals with lived experience. Although well intended, CPGs can adversely affect public policy for patients. For example, recommendations against an intervention may lead service providers and or healthcare funders to reduce access to the intervention and/or withdraw funding for the product or service in a single payer health system. Also, recommendations for costly interventions that are hardly feasible may displace the resources needed for other services (across the care continuum) of greater value to patients in a single payer health system.

Recognizing these aforementioned challenges and limitations, we sought to develop a living guideline that is continuously updated. The Can-SCIP Guideline is the first comprehensive living guideline for adults with SCI in Canada. This article describes the methodology used for the development of the Can-SCIP Guideline intended to highlight its’ unique features and rigor throughout development.

Methods

Scope and purpose of the Can-SCIP guideline

The Can-SCIP Guideline process was initiated by formation of an interprofessional steering committee who through a collaborative process defined the scope and target audience for the Guideline. The Can-SCIP steering committee was comprised of clinicians, program leaders, knowledge translation experts, researchers, and administrators. The Can-SCIP Guideline is designed to provide evidence-based recommendations for adults 18 years and older with a SCI in all phases of care (from pre-hospital emergency care through acute and rehabilitation care and on to community care), across an individual’s lifetime. The majority of the identified recommendations were obtained from the traumatic SCI literature, acknowledging that some recommendations would only be applicable to the care of individuals with SCI of either traumatic or non-traumatic etiology, within the latter parts of the care continuum such as the rehabilitation and community care aspects of the guideline. The Can-SCIP steering committee agreed that the selected recommendations should be divided into two sections: (1) Components of the Ideal SCI Care System; and (2) Management of Secondary Health Conditions. The key secondary health conditions identified for recommendation development was derived from a 2017 national consensus process.14 The Spinal Cord Injury-High Performance Indicator (SCI-HIGH) Project team identified 11 domains of rehabilitation care where gaps between knowledge generation and clinical practice implementation that were important to clinicians and people with SCI for enhancing care and developing quality indicators existed.14 Neuropathic pain was an additional health condition among the top health conditions in SCI considered.15

Target users

The intended audience of the Can-SCIP Guideline are clinicians, allied healthcare providers, support workers, persons with SCI and their caregivers, administrators, and policy makers. The primary users of the Components of the Ideal SCI Care System section are policy makers and administrators, while the primary users of the Management of Secondary Health Conditions section are healthcare providers, individuals with lived experience and their caregivers. The recommendations are intended to specify feasible single or multimodal interventions that are evidence-informed for an individual based on their spinal cord impairment (neurologic level of injury, AIS, cord syndrome and type of bowel and bladder impairment) within the Canadian healthcare context.

Guideline development cycle

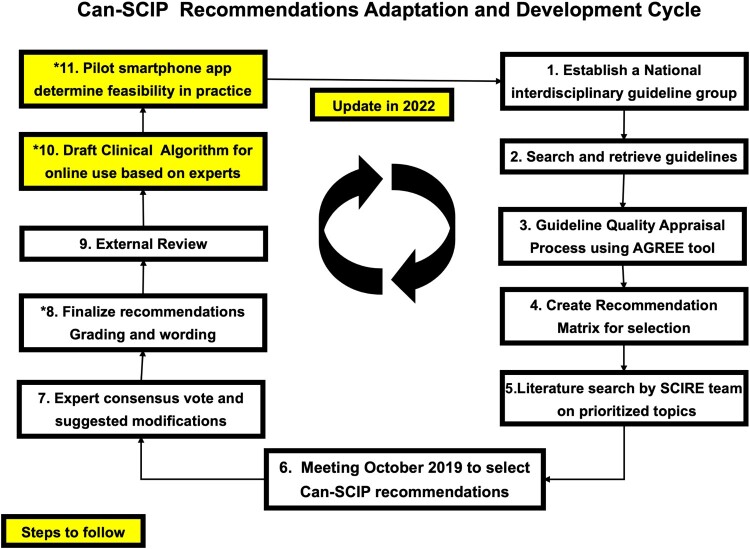

The Can-SCIP Guideline was developed using the Guidelines Adaptation Cycle (ADAPTE) (www.adapte.org) originally derived and modified from a process developed by Graham & Harrison (2005). The steps involved in the process are outlined in Figure 1 and were as follows:

Establish an expert panel: The Can-SCIP expert panel includes clinicians, individuals with lived experience, program directors, knowledge translation experts, researchers, and administrators and other relevant stakeholders (Appendix 1).

Search and retrieval of previously published guidelines: A systematic scoping review was undertaken for CPGs focused on treatment and evidence-based recommendations in the field of SCI. The Can-SCIP steering committee consulted with the Health Sciences Librarian at University of British Columbia to assist with construction of the search. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. In addition, indexes and databases that specifically archive clinical guidelines and medical evidence were also included in the search (NCCIH Clearinghouse,16 Clinical Key,17 Trip Medical Database,18 DynaMed Plus,19 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network,20 CADTH Grey Matters tool,21 Guidelines International Network,22 and Physiotherapy Evidence Database Ratings).23 The key search terms included ‘spinal cord injury’, ‘spinal cord dysfunction’, ‘tetraplegia’, ‘quadriplegia’, ‘paraplegia’, ‘spinal cord impaired’, ‘spinal cord lesion’ (including truncations of these SCI terms) and ‘clinical practice guidelines’. CPGs published between 2011 and 2018 in English or French, written by four or more authors, applicable to the Canadian health care setting, including evidence-based recommendations for adults over 18 years of age were considered for inclusion. Systematic reviews were excluded, and shorter evidence-based documents were excluded, but their reference lists were hand-searched to find any additional clinical practice guidelines for inclusion. The Can-SCIP steering committee reviewed the existing SCI guidelines to ensure the content of the guideline would be consistent with planned scope of the CPG and to ensure the extracted recommendations could be adapted to the Canadian healthcare context (i.e. health system structure, payor model, available expertise etc.). In addition, the Can-SCIP steering committee reached out to stakeholder organizations to identify CPGs that were currently in development.

Guideline quality appraisal process using AGREE instrument: Each eligible CPG was then evaluated individually by two to four appraisers from the expert panel and/or Can-SCIP steering committee, using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II instrument (AGREE II; https://www.agreecollaboration.org). The AGREE II instrument evaluates the guideline development process and quality of the guideline across six domains including: (1) scope and purpose, (2) stakeholder involvement, (3) rigor of development, (4) clarity of presentation, (5) applicability, and (6) editorial independence. Training sessions were held by one of the authors (MB) to ensure all experts were familiar with using the AGREE instrument. Each CPG was given a standardized score ranging from 1 to 100 (100 representing a strong score) by the reviewing appraiser from the expert panel. The AGREE ratings for the selected CPGs are shown elsewhere in this issue.24 As the AGREE User Manual does not specify a minimum score that is considered ‘low-quality,’ the Can-SCIP steering committee set a benchmark of 40% for inclusion; whereby scores higher than 40% represent higher quality, and scores below 40% represent poorer quality. CPGs with an AGREE score below 40% were excluded from the recommendation review process.

Create a recommendation matrix for selection of CPG recommendations: A recommendations matrix was created to facilitate a comparison of the similar or overlapping recommendations across all included CPGs. The CPG recommendations and evidence statements obtained from SCIRE were divided into twenty-four domains relevant to SCI care and treatment within the matrix (Table 1). As various evidence grading systems were used across the different selected CPGs, the Can-SCIP steering committee used a standardized grading system (Table 2) also used in previous CPG development projects.25

Literature search by SCIRE team on prioritized topics: The search processes were enhanced by systematic searches of the SCI literature conducted by the Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE) project team (https://scireproject.com/) to ensure the incorporated recommendations are based on the most current evidence. Evidence statements formulated by the SCIRE project team were added to the synthesized materials prior to convening the entire expert panel to facilitate the formulation of de novo recommendations when there were not existing recommendations, or where the existing guidelines were outdated, insufficient or not relevant to the Canadian context.

- Consensus Meeting to select and/or adapt Can-SCIP recommendations from published recommendations or develop new ones: The expert panel was convened in a two-day meeting prior to the Canadian Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Association (CSCI-RA) 8th National Conference in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, in October 2019. All expert panel members completed declarations of conflicts of interests. The expert panel members were invited to review domains in which they had established expertise or a unique perspective to contribute. Fifty expert panel members reviewed the recommendations matrix independently prior to the consensus meeting and in small working groups during the meeting. At least two individuals with lived experience with SCI were included within each working group to ensure their views were considered. The key activities undertaken by the expert panel members at the consensus conference were to:

- Review the quality assessment of previously published best practice guidelines in the SCI field.

- Consider the evidence tables derived from the SCIRE systematic review.

- Draft or refine recommendations: Each working group selected recommendations from existing CPGs for inclusion, modification or refinement of existing recommendations based on current evidence (i.e. rewording with Canadian terminology, separated some lengthy recommendations into two separate recommendations), or developed new recommendations based on the most current evidence provided by the SCIRE Project. New recommendations with consensus support were also articulated by the experts in each working group. The working groups reviewed recommendations within each domain. In summary, the recommendations were either adopted with the original wording or revised/reworded based on current evidence/settings.

- Assign a level of evidence: The experts reviewed the recommendations and supporting evidence and assigned one of 3 levels of evidence as outlined in Table 2.

- Individualize guidance: For each selected recommendation, the working group specified (i) the section of the care continuum the recommendations applies to (pre-hospital, acute & surgical, tertiary rehabilitation, community), (ii) the neurological level of injury and AIS to which the recommendation applies, (iii) whether the recommendation applies to an individual with a specific cord syndrome – central cord syndrome, anterior cord syndrome, posterior cord syndrome, Brown-Séquard syndrome or cauda equina syndrome; and, (iv) whether the recommendation applies to a person with an upper motor neuron neurogenic bowel or bladder, and (v) whether there were any groups for whom the recommendation does not apply (Appendix 2).

- Identify potential implementation toolkits/resources to assist with implementation. Experts were asked to provide lists of websites, publications, decision rules and other implementation tools that could be used to facilitate recommendation uptake.

Expert consensus vote and final modification suggestions: The expert panel voted on all the recommendations using an online survey tool (Survey Monkey®) (Appendix 2). For each recommendation, the expert panel selected whether the recommend should be included within the Can-SCIP Guideline, whether the recommendation should not be included in the Can-SCIP Guideline, or whether the recommendation should be included in the Can-SCIP Guideline but that further modifications were necessary. Recommendations with less than 80% agreement were excluded from the Can-SCIP Guideline.

Finalize recommendation grading and wording: The Can-SCIP steering committee adapted and refined each draft recommendation based on the feedback received from the expert panel and the established format for the recommendations based on the weight of the evidence underpinning the recommendation.

External review: As part of the validation process, the Can-SCIP Guideline was externally reviewed by recognized international experts in SCI who did not participate in the Can-SCIP Guideline development process (n = 8) (Appendix 3). The purpose of conducting the external review was to gather information on both the reviewer’s overall impression of the Guideline and specific comments addressing the following issues: validity, relevance, awareness of new information, evidence or concerns, scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of the methods and clarity of presentation according to some questions from the AGREE II instrument. The steering committee considered revisions to the Can-SCIP Guideline based on the suggestions and comments from the external reviewers, feedback from the expert panel and the CPG aims and structure.

Figure 1.

Can-SCIP recommendations adaptation and development cycle.

Table 1.

Section 1 & 2 domains.

| Recommendations for the Components of the Ideal SCI Care System | Recommendations for the Management of SCI Health Conditions |

|---|---|

| Pre-hospital and Emergency |

Activity-Based Therapy |

| Diagnostic Imaging |

Autonomic Dysreflexia |

| Early Acute Care |

Bladder |

| Education and Support of People with SCI and their Families Across the Continuum |

Bone Health |

| Cross Continuum Education of Clinicians and Staff Working with People with SCI |

Bowel Health |

| Specialized Inpatient Rehabilitation |

Cardiometabolic Health |

| Specialized Inpatient Rehabilitation |

Emotional Wellbeing |

| Community-Based Rehabilitation |

Mobility & Walking |

| Vocational Rehabilitation | Neuropathic Pain |

| Comprehensive Health and Wellness |

Respiratory Health |

|

|

Sexual Health, Relationships & Fertility |

|

|

Skin Integrity |

| Upper Limb | |

| VTE Prophylaxis |

Table 2.

Summary of criteria for levels of evidence reported in the Can-SCIP guideline.

| Grade of recommendation | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| A | Recommendation supported by at least 1 meta-analysis, systematic review, or randomized controlled trial of appropriate size with relevant control group. |

| B | Recommendation supported by cohort studies that at minimum have a comparison group, well-designed single-subject experimental designs, or small sample size randomized controlled trials. |

| C | Recommendations supported primarily by expert opinion based on their experience through uncontrolled case series without comparison groups that support the recommendations are also classified here. |

Notes: Adapted from Hebert et al.40

Upcoming steps and plans for implementation

Draft clinical algorithm for online use based on experts: To facilitate clinical implementation, multiple algorithms will be drafted to provide clinicians with relevant recommendations for the individual patient based on considerations such as neurological level of injury, AIS and nature of bladder impairment. These algorithms will be incorporated into a web-based application formatted for computers, tablets, and smartphones, displaying the recommendations.

Pilot website to determine feasibility in practice: The Can-SCIP 2 Implementation website will be the first of its kind within SCI and provide clinicians and learners with a valuable user-friendly and easy to follow tool to find best-practice treatments for the patient sitting in front of them. The application will link users to relevant implementation tools and resources (i.e. SCI-FX fracture risk assessment tool, SCI-U, Canadian C-Spine Rule tip card, International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) algorithm) and rehabilitation and community stakeholders to relevant structure, process and outcome health indicators developed by the SCI-HIGH project.26

Results

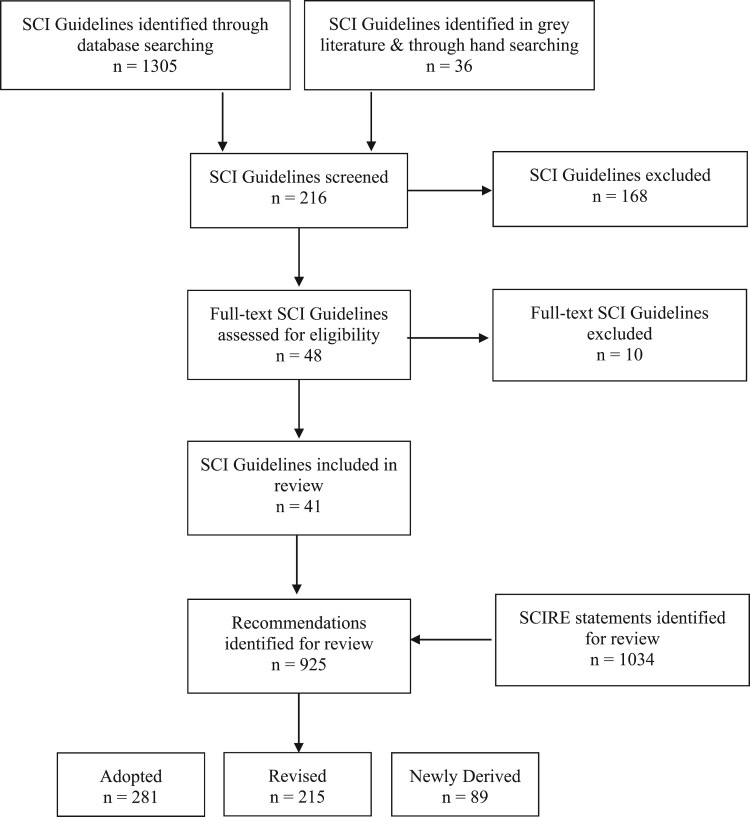

As shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 2), the systematic search identified 41 SCI-specific CPGs that met our inclusion criteria (see Table 3). Following expert review and vetting of recommendations, the Can-SCIP Guideline includes 585 total recommendations, 96 recommendations that pertain to the Components of the Ideal SCI Care System (Table 4) and 489 recommendations that pertain to the Management of Secondary Health Conditions section (Table 5). Tables 4 and 5 provide an overview of each domain and subheadings, the associated number of recommendations, and provides a summary of both the level of evidence and whether the recommendations were adopted, revised, or newly derived. The majority of recommendations 281 (48%) were adopted from other CPGs without revision, 215 (36.8%) recommendations were revised to ensure application in a Canadian context and 89 (15.2%) were created de novo during the expert panel discussions from the SCIRE statements and or reflections on current established best practices. The majority of the recommendations (n = 382, 65.3%) are based on level C evidence, 126 (21.5%) are based on level B evidence, and a minority 77 (13.2%) are based on level A evidence.

Figure 2.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Table 3.

SCI clinical practice guidelines selected for inclusion.

| Guideline name | Abbreviation | Year | Phase of care | Topic area(s) covered | Country of origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal Cord Injury (2009) Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline41 |

NUTR |

2009 |

Cross-Continuum |

Nutrition |

United States |

| Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Adults with SCI42 |

CSCM |

2010 |

Rehab/Community |

Sexuality |

United States |

| Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Canadian Thoracic Society CPG43 |

CTS |

2011 |

Community |

Respiratory |

Canada |

| Evidence-Based Guideline Update: Intraoperative Spinal Monitoring with Somatosensory and Transcranial Electrical Motor Evoked Potentials44 |

NUWER |

2011 |

Acute Care |

Surgical Monitoring |

United States |

| Urinary Incontinence in Neurological Disease: Management of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Neurological Disease45 |

NICE |

2012 |

Cross-Continuum |

Bladder |

United Kingdom |

| Canadian BPG for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in People with SCI: A Resource Handbook for Clinicians46 |

PU-ONF |

2013 |

Cross-Continuum |

Skin |

Canada |

| Clinical Guideline for Standing in Adults Following Spinal Cord Injury47 |

CGFS |

2013 |

Rehab/Community |

Standing Therapy |

United Kingdom & Ireland |

| Development of Clinical Guidelines for the Prescription of a Seated Wheelchair or Mobility Scooter for People with TBI or SCI48 |

OTA |

2013 |

Cross-Continuum |

Wheelchair/ Mobility Device |

Australia |

| Management of Acute Combination Fractures of the Atlas and Axis in Adults49 |

ATL-ATX |

2013 |

Acute |

Surgical Management |

United States |

| Initial Closed Reduction of Cervical Spinal Fracture-Dislocation Injuries50 |

CNS-FXDIS |

2013 |

Acute |

Fracture Treatment |

United States |

| Deep Venous Thrombosis and Thromboembolism in Patients with Cervical SCI51 |

CNS-DVT |

2013 |

Cross-Continuum |

Venous Thrombo-Embolism (VTE) |

United States |

| Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cervical Spine and Spinal Cord Injuries: 2013 Update52 |

CNS |

2013 |

Acute |

Medical/Surgical Management |

United States |

| Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following SCI, 2nd edition53 |

PU-PVA |

2014 |

Cross-Continuum |

Skin/Nutrition |

United States |

| The Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in Primary and Secondary Care54 |

NICE PU |

2014 |

Community |

Skin |

United Kingdom |

| Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury55 |

NPUAP |

2014 |

Cross-Continuum |

Skin |

United States |

| Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in Individuals with SCI56 |

CSCM |

2016 |

Cross-Continuum |

VTE |

United States |

| The CanPain SCI CPG for Rehab Management of Neuropathic Pain after SCI: Recommendations Treatment57 |

CANPAIN TREAT |

2016 |

Cross Continuum |

Pain |

Canada |

| The CanPain SCI CPG for Rehab Management of Neuropathic Pain after SCI: Screening and Diagnosis Recommendations58 |

CANPAIN DIAG |

2016 |

Cross-Continuum |

Pain |

Canada |

| The CanPain SCI CPG for Rehab Management of Neuropathic Pain after SCI: Recommendations for Model Systems of Care59 |

CANPAIN SYS CARE |

2016 |

Cross-Continuum |

Pain |

Canada |

| Provincial Guidelines for Spinal Cord Assessment60 |

CCO |

2016 |

Cross-Continuum |

Medical |

Canada |

| Spinal injury: Assessment and Initial Management61 |

NICE |

2016 |

Acute |

Medical/Surgical |

United Kingdom |

| A Review and Update on the Guidelines for the Acute Management of Cervical SCI – Part II62 | REVIEW PAR | 2016 | Acute | Medical/Surgical | United States |

| Evidence-based Scientific Exercise Guidelines for Adults with SCI: An Update and a New Guideline63 |

GINIS |

2017 |

Rehab/Community |

Exercise |

Canada & United Kingdom |

| CPG for the Management of Patients With Acute SCI and Central Cord Syndrome: Recommendations on the Timing (≤24 h Versus >24 h) of Decompressive Surgery64 |

DECOM |

2017 |

Acute |

Surgical |

International |

| CPG for the Management of Patients With Acute SCI: Recommendations on the Use of Methylprednisolone Sodium Succinate65 |

MSS |

2017 |

Acute |

Medical Management |

International |

| CPG for the Management of Patients With Acute SCI: Recommendations on the Type and Timing of Anticoagulant Thromboprophylaxis66 |

ANTICOAG |

2017 |

Acute |

VTE |

International |

| CPG for the Management of Patients With Acute SCI: Recommendations on the Role of Baseline Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Clinical Decision Making and Outcome Prediction67 |

MRI |

2017 |

Acute |

Diagnostic Imaging |

International |

| CPG for the Management of Patients With Acute SCI: Recommendations on the Type and Timing of Rehabilitation68 |

TIME |

2017 |

Cross-Continuum |

Rehabilitation |

International |

| Rehabilitation in Health Systems69 |

WHO |

2017 |

Cross-Continuum |

Rehabilitation |

International |

| International Perspectives on SCI70 |

WHO INT |

2013 |

Cross-Continuum |

Rehabilitation |

International |

| Urodynamics in Patients with SCI: A Clinical Review and Best Practice Paper71 |

URO |

2017 |

Cross-Continuum |

Urinary Tract |

International |

| Guidelines for the Rehabilitation of Patients with Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression72 |

MSCC |

2017 |

Acute |

Surgical/Medical Decompression |

United Kingdom |

| Norwegian Guidelines for the Prehospital Management of Adult Trauma Patients with Potential Spinal Injury73 |

NOR |

2017 |

Pre-Hospital |

Spinal Immobilization |

Norway |

| Wounds Canada Best Practice Recommendations74 |

WOUNDCAN |

2017 |

Cross-Continuum |

Skin Care |

Canada |

| Neuropathic Pain in Adults: Pharmacological Management in Non-Specialist Settings (CG173)75 |

PALRM |

2018 |

Community |

Pain |

United Kingdom |

| Identification and Management of Cardiometabolic Risk after Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Providers76 |

NASH |

2018 |

Cross-Continuum |

Cardiometabolic Diabetes |

United States |

| Diagnosis, Management and Surveillance Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction77 |

CUA |

2019 |

Cross-Continuum |

Urinary Tract |

Canada |

| Bone Mineral Density Testing in Spinal Cord Injury: The 2019 ISCD Official Positions33 |

BMD |

2019 |

Cross-Continuum |

Bone Health |

International |

| Evaluation and Management of Autonomic Dysreflexia and Other Autonomic Dysfunctions: Preventing the Highs and Lows78 |

PVA AD |

2020 |

Cross-Continuum |

Autonomic Dysreflexia |

United States |

| Management of Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction in Adults after Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Providers79 |

PVA BOWEL |

2020 |

Cross-Continuum |

Bowel |

United States |

| Management of Mental Health Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Suicide in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Practice Guideline for Healthcare Providers80 | PVA EWB | 2020 | Cross-Continuum | Mental Health & Substance Use Disorders | United States |

Table 4.

Can-SCIP domain summary – Section 1.

| Recommendations for the components of the Ideal SCI care system | Total recommendations | Recommendation derivation | Level of evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopted as is | Revised | Newly derived | Level A | Level B | Level C | ||

| PRE-HOSPITAL AND EMERGENCY | 39 | 15 | 24 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 18 |

| Extrication & Transportation of Patients with Acute Cervical SCI | 10 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

| Assessment and Management in Pre-Hospital Settings | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Assessment for Thoracic or Lumbosacral SCI | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| When to Carry Out Full In-Line Spinal Immobilization | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| How to Carry Out Full In-Line Spinal Immobilization | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Receiving Information in Hospital Settings | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Emergency Department Assessment and Management | 12 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Neurological Exam Following Acute Cervical SCI | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Recording Information in Hospital Settings | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Timing of Decompressive Surgery (≤24 h After Injury) in Patients with Acute Spinal Cord Injury | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Providing Information on Transfer from an Emergency Department | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Communication with Tertiary Services | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING | 18 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 10 |

| Introductory Recommendations | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Suspected Spinal Cord or Cervical Column Injury | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Suspected Thoracic or Lumbosacral Column Injury Only | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Diagnostic of Vertebral Artery Injuries Following Non-Penetrating Cervical Trauma | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Radiographic Assessment in Awake, Asymptomatic Patient | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Radiographic Assessment in Obtunded or Unevaluable Patient | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| EARLY ACUTE CARE | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Early Medical Management | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Role of the Registered Dietitian | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Nutrition Assessment: Energy Needs in the Acute Phase | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Preventing Pressure Injuries During the Acute Care Phase | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| EDUCATION AND SUPPORT OF PEOPLE WITH SCI AND THEIR FAMILIES ACROSS THE CONTINUUM | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| CROSS CONTINUUM EDUCATION OF CLINICIANS AND STAFF WORKING WITH PEOPLE WITH SCI | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| SPECIALIZED INPATIENT REHABILITATION | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| COMMUNITY-BASED REHABILITATION | 7 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Community-Based Rehabilitation | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Community Care | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| COMPREHENSIVE HEALTH & WELLNESS | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| TOTAL | 96 | 32 | 43 | 21 | 13 | 27 | 56 |

Table 5.

Can-SCIP domain summary – Section 2.

| Recommendations for the SCI health conditions | Total # of recommendations | Recommendation derivation | Level of evidence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopted as is | Revised | Newly derived | Level A | Level B | Level C | |||

| ACTIVITY BASED THERAPY | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| AUTONOMIC DYSREFLEXIA (AD) | 88 | 80 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 78 | |

| Blood Pressure Following SCI | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| AD | 42 | 34 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 32 | |

| AD & Sexuality | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |

| AD And Cystoscopic (Transurethral and Suprapubic) Urological Procedures and Sperm Retrieval Procedures Performed in the Clinic Setting | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| AD In Pregnancy, Labor and Delivery, and the Postpartum Period | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Induced AD (“Boosting”) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Orthostatic Hypotension | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Thermodysregulation | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| Hyperhidrosis | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| BLADDER | 45 | 17 | 24 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 23 | |

| Screening, History and Physical Assessment Voiding Diary | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Urodynamics | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| Bladder Management | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| - Genitourinary Sequelae of Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| - Conservative Therapy | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| - Medical Therapy | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| - Intravesicular Botox | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| - Surveillance | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| - Surgery | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| BONE HEALTH | 10 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Assessment of Fracture Risk | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| DXA Testing | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Prevention of Osteoporosis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Treatment of Osteoporosis | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | |

| BOWEL | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 16 | |

| Assessment of Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction (NBD) | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Basic Bowel Management (BBM) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Adaptive Equipment | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Diet, Supplements, Fiber, Fluids, and Probiotics | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Oral Medications | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Use of Suppositories, Enemas, and Irrigation | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| Impact of Posture and Activity on NBD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Use of Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Surgical Intervention to Manage NBD | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Managing Medical Complications of NBD | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| CARDIOMETABOLIC | 17 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 13 | |

| CMD risk management and Exercise | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| - Nutrition Screening for People Living in the Community | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Obesity – Nutrition Assessment, Treatment, Bariatric Surgery | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hypertension | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Diabetes Nutritional Support After SCI | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| EMOTIONAL WELLBEING | 54 | 44 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 49 | |

| Screening, Assessment and Treatment | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Diagnostic-Specific Disorders: Anxiety Disorders | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Diagnosis-Specific Disorders: Major Depressive Disorder | 9 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 4 | |

| Diagnosis-Specific Disorders: Substance Use Disorders | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Suicide | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| MOBILITY AND WALKING | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| NEUROPATHIC PAIN | 25 | 3 | 21 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 15 | |

| Introduction and Screening for Neuropathic Pain | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Diagnosis of Neuropathic Pain Clinical Assessment | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Treatment of Neuropathic Pain and Delivery of Care | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Recommendations for Neuropathic Pain Treatment | 10 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Non-Pharmacological Therapies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| RESPIRATORY | 10 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 9 | |

| Lung Volume Recruitment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Abdominal Binder and Abdominal Muscle Simulation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Pharmacological Agents for Respiratory Function | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Respiratory Muscle Training | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Home Mechanical Ventilation | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| SEXUAL HEALTH, RELATIONSHIPS AND FERTILITY | 53 | 3 | 42 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 38 | |

| Introductory Recommendations | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Education | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Relationships | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Sexual History & Assessment | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Optimizing Sexual Well-Being, Body Image and Sensuality | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Physical and Practical Considerations – Bladder | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Physical and Practical Considerations – Bowel | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Physical and Practical Considerations – Sensation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Physical and Practical Considerations – Mobility, Spasticity & Contractures | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Physical and Practical Considerations – Skin Integrity | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Physical and Practical Considerations – Autonomic Dysreflexia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Treatment of Sexual Dysfunction | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Fertility – Men | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fertility – Women | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Fertility – Men & Women | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Contraception | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pregnancy | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| SKIN INTEGRITY | 97 | 42 | 48 | 7 | 19 | 23 | 55 | |

| Prevention | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Human Factors Affecting Pressure Injury Prevention | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Prevention Strategies Across the Continuum of Care | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Wheelchair Pressure Redistribution and Support Surfaces - Other Pressure Redistribution and Support Surfaces | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Recumbent Positioning | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Support Surfaces – Mattress | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Sitting Support Surfaces & Other Seating | 16 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12 | |

| Self-Management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Education and the Person with SCIs Involvement in Care | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Risk & Risk Assessment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Body Weight & Nutrition | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Assessment of the Person with a Pressure Ulcer | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Assessment Using the 24-hour Approach | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Reassessment of Seating Systems | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Assessment of Mobility | 9 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7 | |

| Treatment Principles | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Non-Surgical Treatment | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| - Creating a Physiologic Wound Environment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| - Debridement | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| - Selection of Wound Care Dressing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| - Electrical Stimulation | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Surgical Treatment | 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| Hematologic and Biochemical Parameters of Healing | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Nutrition Intervention for Prevention of Pressure Ulcers | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| UPPER LIMB | 12 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |

| VTE PROPHYLAXIS | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | |

| Prophylaxis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Screening Patients for Asymptomatic Deep-Vein Thrombosis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Diagnosis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mechanical Methods of Thromboprophylaxis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Thromboprophylaxis | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Thromboprophylaxis in Hospitalized Chronic SCI Patients | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| WHEELED MOBILITY | 19 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 12 | |

| TOTAL | 489 | 249 | 172 | 68 | 64 | 99 | 326 | |

Within the Components of the Ideal SCI Care System, 39 recommendations (40.6%) pertain to prehospital care, 18 (18.8%) that pertain to diagnostic imaging, 9 (9.4%) pertain to early acute care, 20 (20.8%) that pertain to specialized rehabilitation and community transitions, and 10 (10.4%) that pertain to education for clinicians, patients and caregivers across the care continuum. In the health systems portion of the guideline, the majority of the 21 new recommendations pertain to community-based rehabilitation.

In the Secondary Health Conditions section, there were over 68 new recommendations. There was a total of 249 recommendations that were adopted without revision and 172 recommendations that were revised. Across the Secondary Health Conditions section, the aspects of care with the most recommendations, pertain to common and severe complications including skin integrity (97 recommendations), autonomic dysreflexia (88 recommendations), emotional well-being (54 recommendations) and sexual health, relationships, and fertility (53 recommendations).

A substantial proportion of the recommendations (86%) were felt to be generic for application to the entire SCI community regardless of impairment. The majority of the recommendations are applicable across the rehabilitation and community settings; whereas for prehospital care and surgical interventions there was greater specificity based on the mechanism of injury and associated impairments (data not shown). This data will be used to inform the design of the Can-SCIP Guideline website and will be presented in a future manuscript with the associated algorithms.

Discussion

SCI results in a complex constellation of impairments that require tertiary care across the health system and the individual’s lifespan27,28 to reduce morbidity and mortality and augment functional recovery, health and well-being. The Can-SCIP Guideline is the first comprehensive guideline for adults with SCI in Canada that has integrated recommendations from 41 guidelines and has validated the guideline content for implementation in Canada.

A total of 585 recommendations were explicitly adopted (n = 281), adapted (n = 215) or newly developed (n = 89) to align with the Canadian healthcare environment, providing a set of recommendations that cover the continuum from pre-hospital to community-based care that are customized for the individual based on their impairment. Due to the sheer number of recommendations, and the diverse audiences for sections of the Guideline content, the Can-SCIP steering committee a priori elected to divide the recommendations into two sections: the first section addressing recommendations for the components of the ideal SCI care system and the second section addressing the management of secondary health conditions. The target audience for this section is health system leaders who make decisions about human resources, capital equipment, staff training, physical space, and specialized equipment needed for optimal care. The second section provides recommendations to address secondary health conditions within prioritized domains for rehabilitation care deemed important by SCI stakeholders. The target audiences for this section are individuals with SCI and their regulated healthcare professionals.

There are gaps in the number and complexity of recommendations in the latter part of the healthcare continuum that in part reflect the design and resourcing of the health system and existence of available community sector administrative data sources.29 Areas in which new recommendations were developed to reflect burgeoning science. also reflect the presence of local champions in Canada who are leading the development of innovations in SCI care including: hemodynamic monitoring,30 early surgical spinal cord decompression,31 upper limb rehabilitation including the selection of patient appropriate for tenodesis or peripheral nerve transplant surgery,32 bone health,33 autonomic dysreflexia,34 respiratory care,35,36 and sexual health.37

Not surprisingly, the greatest number of recommendations pertain to skin integrity, autonomic dysreflexia and neurogenic bladder management that are the most frequent secondary health conditions which have a profound adverse impact on an individual’s health, resource requirements and mortality.

As discussed above, there are fewer recommendations supported by high-quality randomized controlled trials, reflecting the low proportion of level A recommendations. This reflects the nature of the SCI evidence, the relatively low incidence and prevalence and the challenge of studying complex interventions in this population with heterogeneous impairments. Further, challenges within the field of SCI internationally include: ongoing difficulties in funding and accruing an adequate sample size within clinical trials, restricting our ability to generate Level I evidence to inform practice.6,7

The Can-SCIP Guideline development process had multiple benefits:

Instead of duplicating the solid work of other guideline groups, it allowed for the Can-SCIP group to conduct a quality assessment of existing SCI CPGs that allowed the expert panel members to adopt the highest quality recommendations for inclusion. This process allowed for many important clinical questions which arise for individuals throughout an individual’s care journey to be addressed and may be used by all members of an interprofessional care team.

Each working group had access to the SCIRE systematic literature review evidence tables to ensure all evidence that had not been incorporated into previous guidelines were considered for each domain.

We adhered to the processes for engaging individuals with lived experience described by Gainforth and colleagues38 throughout the guideline development process.

The expert panel members specified which recommendations apply to specific impairments groups which will allow clinicians to quickly identify recommendations relevant to the patient in front of them.

The Can-SCIP Guideline has some limitations. Research in SCI is typically based on small sample sizes and tested in a pre–post design. There are comparatively few research studies with stronger research designs such as prospective randomized controlled trials, matched-control designs, and longitudinal designs. Treatments tested in studies with small sample sizes and emerging technologies have little chance of appearing in CPGs, until they have been more widely tested, a process that takes many years. The recommendations within the Can-SCIP Guideline are informed by the best evidence available at the time of publication. Future versions of the Can-SCIP Guideline will be highly influenced by new level A or high-quality level B evidence. Clinicians should consider patient preferences, their clinical judgment, and context-dependent factors (i.e. availability of resources) in their clinical decision-making process.

As the current model used to update CPGs involves revising the entire CPG within a specific time interval (e.g. every two years), some recommendations may be out of date by the time the CPG is updated, thereby affecting the validity of specific recommendations.39 Further, the evidence base for some recommendations may not vary significantly between CPG updates; thereby, slowing the efficiency of the update process. To overcome these challenges, living guidelines are an alternative to standard guideline development methods which will allow recommendations within a CPG to be updated as new and relevant evidence is published.39 The Can-SCIP Guideline Living Guideline Panel will adopt a living guideline process to provide target users with up-to-date and high-quality advice. This process will involve a living systematic review, living evidence profiles, living evidence-to-decision tables, ongoing participation from a living guideline panel, timely peer review processes, with routine publication and dissemination, with a sustainable source of funding. These processes and associated work plan will be discussed in a subsequent publication. In brief, Can-SCIP Guideline recommendations will be prioritized for revision and dissemination based on the following criteria39:

“The recommendation is a priority for decision-making”39 which may be affected by increased prevalence of morbidity and mortality or emergent interventions or therapies.

There is a moderate-to-high probability that emerging evidence may improve the level of a particular intervention (i.e. in instances when the level of evidence is a “B” or “C” within the Guideline).

There is active research within a particular topic area of interest to the field.

The Can-SCIP Guideline will be posted on an interactive website (https://canscip.com), and all recommendations will be updated in real-time. For expediency, a push notification will be sent to followers notifying them that specific recommendations have been revised.

Conclusion

The Can-SCIP Guideline recommendations were developed using a systematic and rigorous process of evaluating previously published rigorously developed CPGs. The recommendations are pertinent to the care of individuals with SCI over their lifespan from injury onset to healthy aging in the community. The 585 guideline recommendations are intended to assist clinicians, administrators, and policy makers within interdisciplinary teams to provide evidence-informed multidisciplinary care to individuals with SCI within the Canadian healthcare context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We extend our particular gratitude to the entire expert panel for their expertise, dedication and support of the Can-SCIP Guideline: Andrea Townson, Andréanne Richard-Denis, Andrei Krassioukov, Blayne Welk, Brian Kwon, Christine Short, Christopher West, Colleen O'Connell, Daryl Forney, Deena Lala, Denise Hill, Graham Jones, Heather Flett, Jamie Milligan, Jeff Wilson, Joanne Smith, John Chernesky, John Cobb, John Shepherd, Karen Ethans, Katharina Kovacs Burns, Kristin Musselman, Kristine Cowley, Laurent Bouyer, Leanna Ritchie, Lise Bélanger, Louise Russo, Marie-Thérèse Laramée, Michael Fehlings, Milos Popovic, Pamela Houghton, Peter Athanasopoulos, Richard Fox, Sean Christie, Sera Nicosia, Shane McCullum, Shea Hocaloski, Sonja McVeigh, Stacy Elliot, Steve Casha, Sukhvinder Kalsi-Ryan, Susan Jaglal, Teren Clarke.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding This work was supported by the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute (former Rick Hansen Institute) [grant number G2019-11].

Declaration of interest Dr. B. Catharine Craven acknowledges support from the Toronto Rehab Foundation as the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Chair in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, and receipt of consulting fees from the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. Vanessa Noonan and Christiana Cheng are employees of the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. Eleni Patsakos, Janice Eng, Matthew Querée, Chester Ho and Ailene Kua report no conflicts of interest. Dr. M. Bayley receives a stipend from UHN- Toronto Rehabilitation Institute for his role as Medical Director but has no other conflicts of interests.

Conflicts of interest Authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Hitzig SL, Escobar EMR, Noreau L, Craven BC.. Validation of the reintegration to normal living index for community-dwelling persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93(1):108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr JJ, Kendall MB, Amsters DI, Pershouse KJ, Kuipers P, Buettner P, et al. Community participation for individuals with spinal cord injury living in Queensland, Australia. Spinal Cord 2017;55(2):192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guilcher SJT, Catharine Craven B, Bassett-Gunter RL, Cimino SR, Hitzig SL.. An examination of objective social disconnectedness and perceived social isolation among persons with spinal cord injury/dysfunction: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Disabil Rehabil 2019;43(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craven BC, Balioussis C, Verrier M.. The tipping point: perspectives on SCI rehabilitation service gaps in Canada. Int J Phys Med Rehabil 2013;1(8):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVivo MJ, Savic G, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, Soni BM, Charlifue S, et al. Comparison of statistical methods for calculating life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2018;56(7):666–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blight AR, Hsieh J, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Guest JD, Kleitman N, et al. The challenge of recruitment for neurotherapeutic clinical trials in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2019;57(5):348–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulcahey MJ, Jones LAT, Rockhold F, Rupp R, Kramer JLK, Kirshblum S, et al. Adaptive trial designs for spinal cord injury clinical trials directed to the central nervous system. Spinal Cord 2020;58(12):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters S, Bussières A, Depreitere B, Vanholle S, Cristens J, Vermandere M, et al. Facilitating guideline implementation in primary health care practices. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:2150132720916263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ketelaar M, Russell DJ, Gorter JW.. The challenge of moving evidence-based measures into clinical practice: lessons in knowledge translation. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2008;28(2):191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grol R, Grimshaw J.. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 2003;362(9391):1225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciliska DK, Pinelli J, DiCenso A, Cullum N.. Resources to enhance evidence-based nursing practice. AACN Adv Crit Care 2001;12(4):520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies BL. Sources and models for moving research evidence into clinical practice. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2002;31(5):558–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care 2001;39(8):II46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alavinia SM, Hitzig SL, Farahani F, Flett H, Bayley M, Craven BC.. Prioritization of rehabilitation domains for establishing spinal cord injury high performance indicators using a modification of the Hanlon method: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marion TE, Rivers CS, Kurban D, Cheng CL, Fallah N, Batke J, et al. Previously identified common post-injury adverse events in traumatic spinal cord injury—validation of existing literature and relation to selected potentially modifiable comorbidities: a prospective Canadian cohort study. J Neurotrauma 2017;34(20):2883–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCCIH Clearinghouse [Internet]. Available from https://nccih.nih.gov/health/clearinghouse.

- 17.Clinical Key [Internet]. Available from https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/clinicalkey.

- 18.Trip Medical Database [Internet]. Available from https://www.tripdatabase.com.

- 19.DynaMed Plus [Internet]. Available from https://www.dynamed.com/home/.

- 20.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [Internet]. Available from https://www.sign.ac.uk/.

- 21.CADTH Grey Matters Tool [Internet]. Available from https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters.

- 22.Guidelines International Network [Internet]. Available from https://www.g-i-n.net/home.

- 23.Physiotherapy Evidence Database Ratings (PEDro) [Internet]. Available from https://www.pedro.org.au/.

- 24.Patsakos EM, Bayley MT, Kua A, Cheng C, Eng J, Ho C, et al. Quality of published SCI clinical practice guidelines: results from Can-SCIP panel appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation (AGREE) evaluation. J Spinal Cord Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsay P, Bayley M, Kelloway L.. P75–recommendations are not enough: creating a toolbox to support stroke guideline uptake. Otolaryngol Neck Surg 2010;143(1_suppl):117. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craven BC, Alavinia SM, Wiest MJ, Farahani F, Hitzig SL, Flett H, et al. Methods for development of structure, process and outcome indicators for prioritized spinal cord injury rehabilitation domains: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):51–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadel L, Everall AC, Packer TL, Hitzig SL, Patel T, Lofters AK, et al. Exploring the perspectives on medication self-management among persons with spinal cord injury/dysfunction and providers. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2020;16(12):1775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noonan V, Fallah N, Park S, Dumont F, Leblond J, Cobb J, et al. Health care utilization in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury: the importance of multimorbidity and the impact on patient outcomes. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2014;20(4):289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowan CP, Chan BCF, Jaglal SB, Catharine Craven B.. Describing the current state of post-rehabilitation health system surveillance in Ontario–an invited review. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong CY, Hosseini AM, Belanger LM, Ronco JJ, Paquette SJ, Boyd MC, et al. A prospective evaluation of hemodynamic management in acute spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 2013;51(6):466–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badhiwala JH, Ahuja CS, Fehlings MG.. Time is spine: a review of translational advances in spinal cord injury: JNSPG 75th anniversary invited review article. J Neurosurg Spine 2018;30(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon BK, Liu J, Messerer C, Kobayashi NR, McGraw J, Oschipok L, et al. Survival and regeneration of rubrospinal neurons 1 year after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2002;99(5):3246–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse LR, Biering-Soerensen F, Carbone LD, Cervinka T, Cirnigliaro CM, Johnston TE, et al. Bone mineral density testing in spinal cord injury: 2019 ISCD official position. J Clin Densitom 2019;22(4):554–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowan H, Lakra C, Desai M.. Autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injury. Br Med J 2020;371:m3596,1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKim DA, Avendano M, Abdool S, Côté F, Duguid N, Fraser J, et al. Home mechanical ventilation: a Canadian thoracic society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J 2011;18:197–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose L, McKim D, Leasa D, Nonoyama M, Tandon A, Kaminska M, et al. Monitoring cough effectiveness and use of airway clearance strategies: a Canadian and UK survey. Respir Care 2018;63(12):1506–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott SL. Problems of sexual function after spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res 2006;152:387–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gainforth HL, Hoekstra F, McKay R, McBride CB, Sweet SN, Ginis KAM, et al. Integrated knowledge translation guiding principles for conducting and disseminating spinal cord injury research in partnership. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;102(4):656–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J, Kahale LA, Schünemann HJ, Agoritsas T, et al. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;91:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hebert D, Lindsay MP, McIntyre A, Kirton A, Rumney PG, Bagg S, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: stroke rehabilitation practice guidelines, update 2015. Int J Stroke 2016;11(4):459–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Spinal Cord Injury Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline [Internet]. 2009. Available from https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?cat=3485.

- 42.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Sexuality and reproductive health in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med [Internet]. 2010;33(3):281–336. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20737805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Home mechanical ventilation: a Canadian thoracic society CPG, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Evidence-based guideline update: intraoperative spinal monitoring with somatosensory and transcranial electrical motor evoked potentials, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.UK National Clinical Guideline Centre. Urinary incontinence in neurological disease: management of lower urinary tract dysfunction in neurological disease, 2012; Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23638496/. [PubMed]

- 46.Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation. Canadian best practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury. Available from https://onf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Pressure_Ulcers_Best_Practice_Guideline_Final_web4.pdf.

- 47.Multidisciplinary Association of Spinal Cord Injury Professionals. Clinical guideline for standing in adults following spinal cord injury [Internet]. 2013. Available from https://www.mascip.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Standing-Adults-Following-Spinal-Cord-Injury.pdf.

- 48.Development of clinical guidelines for the prescription of a seated wheelchair or mobility scooter for people with TBI or SCI [Internet], 2013. Available from https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/167286/Guidelines-on-Wheelchair-Prescription.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Ryken T, Hadley M, Aarabi B, Sanjay S, Gelb D RJH, et al. Management of acute combination fractures of the atlas and axis in adults. Neurosurgery 2013;72(suppl_3):151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gelb DE, Hadley MN, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Hurlbert J, Rozzelle C, et al. Initial closed reduction of cervical spinal fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgery 2013;72(suppl_3):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhall SS, Hadley MN, Aarabi B, Gelb DE, Hurlbert RJ, Rozzelle CJ, et al. Deep venous thrombosis and thromboembolism in patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery 2013;72(suppl_3):244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries: 2013 update, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following SCI, 2nd ed., [Internet], 2014. Available from https://www.mascip.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/CPG_Pressure-Ulcer.pdf.

- 54.NCGC UK. The prevention and management of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care [Internet]. 2014. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25340232/. [PubMed]

- 55.Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: individuals with spinal cord injury [Internet], 2014. Available from https://www.internationalguideline.com/static/pdfs/08-NPUAP-EPUAP-PPPIAIndividualswithSCIExtractoftheCPG 2017.pdf

- 56.PCI Statements . Prevention of venous thromboembolism in individuals with spinal cord injury: clinical practice guidelines for health care providers. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2016;22(3):209–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guy SD, Mehta S, Casalino A, Côté I, Kras-Dupuis A, Moulin DE, et al. The CanPain SCI clinical practice guidelines for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: recommendations for treatment. Spinal Cord [Internet] 2016;54(1):S14–23. Available from 10.1038/sc.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehta S, Guy SD, Bryce TN, Craven BC, Finnerup NB, Hitzig SL, et al. The CanPain SCI clinical practice guidelines for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: screening and diagnosis recommendations. Spinal Cord [Internet] 2016;54(1):S7–13. Available from 10.1038/sc.2016.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guy SD, Mehta S, Harvey D, Lau B, Middleton JW, O’Connell C, et al. The CanPain SCI clinical practice guideline for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: recommendations for model systems of care. Spinal Cord [Internet] 2016;54(1):S24–7. Available from 10.1038/sc.2016.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Critical Care Services Ontario. Provincial guidelines for spinal cord assessment [Internet], 2016. Available from https://criticalcareontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Guidelines-for-Adult-Spinal-Cord-Assessment-May-2016.pdf.

- 61.NICE. Spinal injury: assessment and initial management. Retrieved from world wide web [Internet]. 2017;17(01). Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK344254/.

- 62.Yue JK, Chan AK, Winkler EA, Upadhyayula PS, Readdy WJ, Dhall SS.. A review and update on the guidelines for the acute management of cervical spinal cord injury-part II. J Neurosurg Sci 2015;60(3):367–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ginis KAM, Van Der Scheer JW, Latimer-Cheung AE, Barrow A, Bourne C, Carruthers P, et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord 2018;56(4):308–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Wilson JR, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury and central cord syndrome: recommendations on the timing (≤24 hours versus >24 hours) of decompressive surgery. Glob Spine J 2017;7(3_suppl):195S–202S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury: recommendations on the use of methylprednisolone sodium succinate. Glob Spine J 2017;7(3_suppl):203S–11S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury: recommendations on the type and timing of anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis. Glob Spine J 2017;7(3_suppl):212S–20S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fehlings MG, Martin AR, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, et al. CPG for the management of patients with acute SCI: recommendations on the role of baseline magnetic resonance imaging in clinical decision making and outcome prediction. Glob Spine J [Internet] 2017;7(3_suppl):221S–30S. Available from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/ 10.1177/2192568217703089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.CPG for the management of patients with acute SCI: recommendations on the type and timing of anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis, 2017.

- 69.Rehabilitation in health systems [Internet], 2017. Available from https://www.who.int/disabilities/rehabilitation_health_systems/en/.

- 70.WHO. International perspectives on SCI [Internet], 2013. Available from https://www.who.int/disabilities/policies/spinal_cord_injury/en/.

- 71.Schurch B, Iacovelli V, Averbeck MA, Carda S, Altaweel W, Finazzi Agrò E.. Urodynamics in patients with spinal cord injury: a clinical review and best practice paper by a working group of the international continence society urodynamics committee. Neurourol Urodyn 2018;37(2):581–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Occupational therapists and physiotherapists in the community setting (Northern Ireland). Guidelines for the rehabilitation of patients with metastatic spinal cord compression [Internet], 2017. p. 1–96. Available from https://www.rqia.org.uk/RQIA/files/cb/cba33182-deab-46ae-acd1-d27279d9847c.pdf

- 73.Kornhall DK, et al. Norwegian guidelines for the prehospital management of adult trauma patients with potential spinal injury. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wounds Canada. Wounds Canada Best Practice Recommendations [Internet]. 2017. Available from https://www.woundscanada.ca/health-care-professional/resources-health-care-pros/12-healthcare-professional/110-supplements

- 75.NICE. Neuropathic Pain in Adults: Pharmacological Management in Non-Specialist Settings (CG173) [Internet]. 2018. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg173

- 76.Nash MS, Groah SL, Gater Jr DR, Dyson-Hudson TA, Lieberman JA, Myers J, et al. Identification and management of cardiometabolic risk after spinal cord injury: clinical practice guideline for health care providers. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil [Internet] 2018;24(4):379–423. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30459501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kavanagh A, Baverstock R, Campeau L, Carlson K, Cox A, Hickling D, et al. Canadian urological association guideline: diagnosis, management, and surveillance of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction–full text. Can Urol Assoc J 2019;13(6):E157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Krassioukov A, Linsenmeyer TA, Beck LA, Elliott S, Gorman P, Kirshblum S, et al. Evaluation and management of autonomic dysreflexia and other autonomic dysfunctions: preventing the highs and lows: management of blood pressure, sweating, and temperature dysfunction. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2021;27(2):225–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johns J, Krogh K, Rodriguez GM, Eng J, Haller E, Heinen M, et al. Management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in adults after spinal cord injury: clinical practice guideline for health care providers. J Spinal Cord Med 2021;44(3):442–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bombardier CH, Azuero CB, Fann JR, Kautz DD, Richards JS, Sabharwal S.. Management of mental health disorders, substance use disorders, and suicide in adults with spinal cord injury: clinical practice guideline for healthcare providers. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2021;27(2):152–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.