Abstract

Background/objectives

Heightened stress tends to undermine both teachers' efficacy and students' outcomes. Managing job stress in teachers of children with special education needs is continually recommended due to the increased demands for the teachers to adapt curriculum content, learning materials and learning environments for learning. This study investigated the efficacy of blended Rational Emotive Occupational Health Coaching in reducing occupational stress among teachers of children with special needs in Abia State, Nigeria.

Method

The current study adopted a group-randomized waitlist control trial design with pretest, post-test and follow-up assessments. Participants (N = 83) included teachers of children with special education needs in inclusive and specialized schools. The bREOHC group was exposed to intersession face-to-face and online REOC program weekly for twelve (12) weeks. Data were collected using Single Item Stress Questionnaire (SISQ), Teachers' Stress Inventory and Participants' Satisfaction questionnaire (PSQ). Data collected at baseline; post-test as well as follow-up 1 and 2 evaluations were analyzed using mean, standard deviation, t-test statistics, repeated measures ANOVA and bar charts.

Results

Results revealed that the mean perceived stress, stress symptoms and the total teachers' stress score of the bREOHC group at post-test and follow up assessments reduced significantly, compared to the waitlisted group. Participants also reported high level of satisfaction with the therapy and procedures.

Conclusion

From the findings of this study, we conclude that blended REOHC is efficacious in occupational stress management among teachers of children with special education needs.

Keywords: Rational emotive occupational health coaching, Job-stress, Children with special needs, Teachers, Education

Highlights

-

•

Teachers of children with special needs undergo unequal stress.

-

•

A group-randomized waitlist control trial design gave the opportunity to offer intervention to all participants.

-

•

bREOHC is effective in reducing perceived stress, stress symptoms and the total teachers’ stress score

-

•

Reduced stress following bREOHC was sustained at follow-up.

-

•

Participants reported high level of satisfaction with the therapy when exposed to bREOHC.

1. Introduction

Job-related stress is widespread across employees (Asamoah-Appiah and Aggrey-Fynn, 2017; Ojwang, n.d.; Ogba et al., 2019), affecting about 70–89% of educators worldwide (Reddy and Anuradha, 2013; Sukumar and Kanagarathinam, 2016; Okwaraji and Aguwa, 2015; Manabete et al., 2016). Stress occurs when there is an activation in the body due to mismatch between the environmental demands and the ability to cope with such demands (Reddy and Anuradha, 2013), causing significant, cognitive, physical and/or emotional impacts on health and well-being (Sukumar and Kanagarathinam, 2016; Okwaraji and Aguwa, 2015; Manabete et al., 2016; AbuMadini and Sakthivel, 2018). Job-stress is a negative subjective feeling experienced in occupational situation (Ogba et al., 2020). Job-related stress hampers employees' productivity, and is common among teachers. (Reddy and Anuradha, 2013; Sukumar and Kanagarathinam, 2016; Okwaraji and Aguwa, 2015; Manabete et al., 2016; AbuMadini and Sakthivel, 2018; Ogba et al., 2020; Chadha et al., 2012; Peltzer et al., 2009; Sumathy and Sudha, 2013) It manifests in teachers as distasteful emotions such as worry, irritation, anger, frustration and depression resulting from work experiences. (Reddy and Anuradha, 2013; Sukumar and Kanagarathinam, 2016; Okwaraji and Aguwa, 2015; Manabete et al., 2016; AbuMadini and Sakthivel, 2018; Ogba et al., 2020; Chadha et al., 2012; Peltzer et al., 2009; Sumathy and Sudha, 2013; Pereira-Morales et al., 2017) Teachers' stress is also results in emotional consequences as depression, anxiety, burnout and decreased job satisfaction; (Ogba et al., 2019; Manabete et al., 2016; AbuMadini and Sakthivel, 2018; Ogba et al., 2020; Chadha et al., 2012; Peltzer et al., 2009; Sumathy and Sudha, 2013; Pereira-Morales et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2015a; Major, 2012; Cappe et al., 2017) professional consequences including absenteeism, inefficiency, attrition, and suicidal and attempt (Reddy and Anuradha, 2013; Zarafshan et al., 2013; Kebbi, 2018; Atiyat, 2017; Gersten et al., 2001; Kuvaeva, 2018; Bush, 2010; Davis, n.d.; Arun et al., 2017; Hamlett, 2016). It also results in physiological symptoms such as headache, impaired immune function, musculoskeletal pains, and cardiovascular diseases (Ogba et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2015b).

Thus, extant literature shows that teachers' job-stress tend to undermine teachers' job performance (Ogba et al., 2019; Sukumar and Kanagarathinam, 2016; Okwaraji and Aguwa, 2015; AbuMadini and Sakthivel, 2018) and alter the overall development of the child, especially when the child is living with disabilities, needing special education (Asamoah-Appiah and Aggrey-Fynn, 2017; Zarafshan et al., 2013; Kebbi, 2018; Atiyat, 2017; Gersten et al., 2001; Kuvaeva, 2018; Bush, 2010; Ojwang, n.d.; Arun et al., 2017). Compared to general teachers' population, those who teach learners with special needs tend to experience a heightened level of job-stress (Peltzer et al., 2009; Sumathy and Sudha, 2013; Zarafshan et al., 2013; Kebbi, 2018; Atiyat, 2017; Gersten et al., 2001). In Nigeria, high level of work stress has been recorded across teachers at all level of Education (Gersten et al., 2001; Ugwoke et al., 2018; Malik and Björkqvist, 2018; Dankade et al., 2016; Hashim and Kayode, 2010) and especially those who teach children with special education needs (Ogba et al., 2020). Such teachers' high levels of stress reactions could be due to negative and dysfunctional perception of their experiences in teaching children who present the need for special education. This is because, such teachers are required to implement curriculum adaptations, and individualized education programs (IEPs) and compulsory differentiation (Ukonu and Edeoga, 2019; Yusuf et al., 1937–1942; Onyishi and Sefotho, 2020), that may trigger irrational beliefs/orientations leading to aversive stress reactions (Ellis, 1994). Such negative reactions to work-place stressors can be changed using a rational emotive occupational health Coaching (REOHC) to bring about positive health and occupational outcomes (Ogba et al., 2020).

REOHC intends to help employees develop practical skills for coping with job-related stress reactions. REOHC uses ABCDE modality to assist employees in coping with work stress (Ojwang, n.d.; Ogba et al., 2020; Mahfar and Senin, 2013) through disputing dysfunctional thoughts and the associated emotional symptoms (Ellis, 1994; Ellis, 2014). In this regard, “A” represents the objective stressor which could be the events associated with working conditions (Activating events). “B” includes beliefs, cognition, perception and world-view about the activating event which are either functional or dysfunctional. “C” is the psychological reactions otherwise called consequence. “D” is disputing challenging irrational, while “E” is effective emotion (Mahfar and Senin, 2013).

REOHC uses strategies, including disputation, homework tasks, discussion, and role-play together with cognitive, behavioral and emotional techniques to help participants to change negative perceptions, navigate unhelpful emotions and reduce stress (Ogba et al., 2019; Ellis, 1994; Mahfar and Senin, 2013; Ellis, 2014). The intervention could be administered either as group face-to-face therapy or using Smartphones, WhatsApp chat application, and e-mail (Ellis, 1994). However, Mackie et al. (2017) suggested that rather than replacement, internet-based therapies can be used to supplement or augment face-to-face therapies.

Hence, although REOHC intervention for work-place stress have recorded a great success among special education teachers (Ojwang, n.d.; Ellis, 1994; Ellis, 1995; Ellis and MacLaren, 1998), the intricate nature of stress related health challenges in teachers of autistic children may recommend a more innovative intervention approach that could offer additional support that is cost-effective and handy. This is of great essence given that some beneficiaries of REOHC-based treatments tend to report significant symptoms after face-to-face intervention (Ogba et al., 2020; Mahfar and Senin, 2013; Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a). When face-to face interventions are blended with online sessions(Onyishi et al., 2020; Mathiasen et al., 2016) better results may be achieved. Blended therapy has been recommended for better outcomes in cognitive and behavioral interventions. (Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a; Onuigbo et al., 2018) Blended therapy refers to the conjunction of both therapists' face-to-face sessions and internet-based material in psychotherapeutic interventions (Onuigbo et al., 2018). It can be in the form of different permutations of face-to-face intervention and online supports in different therapeutic interventions (Mackie et al., 2017; Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a; Onuigbo et al., 2018). Blended therapies can take the form of integrating online modules with in-person therapy at either in-between the face-to-face sessions (inter-session), prior to face-to-face sessions in terms of preparing the client for therapy, or after face-to-face interventions as a form of supplementary therapy (Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a; Vernmark et al., 2019; van de Wal et al., 2017).

Compared to traditional face-to-face REOHC, bREOHC could provide the employers with increased access to the complementary support program across time and place (Kooistra et al., 2016). It reduces cost of clinical visits and increases support seeking skills in an unspecified environment (Kooistra et al., 2019). In this study, bREOHC was in the form of face-to-face therapy with inter-session internet-based therapy. bREOHC modality could help therapists and clients to overcome time constraints and lesson the expenditure and physical demand (Onuigbo et al., 2018; Rasing et al., 2019). Blended therapy has the benefit of accessibility, lower costs, lower time commitment for both clinicians and clients; helping client to take more of an active role in treatment; maintaining clients' motivation and momentum; enabling the transmission of photographs from the participant to therapist to track the client's progress and enhance accountability (Kooistra et al., 2019; Rasing et al., 2019; Romijn et al., 2015).

Qualitative data results show that participants reported greater compliance, greater exposure to treatment and motivated participation in both blended therapy as a result of the internet-augmented contacts between face-to-face therapy sessions (Romijn et al., 2015). Overall, results from experimental studies attest to the efficacy of blended therapies (Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a; van de Wal et al., 2017; Kooistra et al., 2019; Rasing et al., 2019; Romijn et al., 2015). Nevertheless, it is not established whether blending a traditional REOHC program with inter-session online modules would be of added advantage in reducing occupational stress in teachers of children with special needs. The current study sought to fill the knowledge gap by using a bREOHC for stress management in a sample of teachers of children with ASDs. It is therefore hypothesized that by the end of the interventions, the job stress of the bREOHC group will decrease significantly over those in the waitlist group, and the reduced job-stress would be sustained at 3 and six months follow-up assessments.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical consideration

Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Faculty of Educational research committee, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria (REC/ED/18/00037). The study also complied to the research ethical standard as specified by the American Psychological Association and World Medical Association (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, 2020) Informed written consent was also obtained from the study participants.

3. Measures

3.1. The Single Item Stress Questionnaire (SISQ)

This single-item measure of stress symptoms was used as one of the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study. The instrument has consistently been found valid and reliable in stress researches (Moldovan, 2017; Suleman et al., 2018), showing Chrombach reliability indices ranging from 0.80–0.86. The instrument reads: “stress means a situation when a person feels tense, restless, nervous, anxious or unable to sleep at night because his or her mind is troubled all the time. Do you feel that kind of stress these days?” The SISQ is measured in a 5-point scale ranging from 1-“not at all” to 5-“very much”. In this study, scores ranging from 1 to 2 indicate low stress; 3 indicate moderate stress; while 4–5 indicate a high-stress level. The researcher found a Chronbach Alpha reliability index of 0.79 among 20 adult workers in Nigeria for SISQ.

3.1.1. The Teachers' stress inventory (TSI)

TSI (von der Embse et al., 2015) used in this study is a 49-item questionnaire rated in five-point Likert scale. Items in the instrument cover ten subscales, covering two major dimensions of stress (Stress Sources and Stress Manifestations). Stress Sources dimension include five subscales including Time management, Work-related stressors, Professional distress, Discipline and motivation, and Professional investment (von der Embse et al., 2015). Stress Manifestations dimension also include five subscales of emotional manifestations (such as anxiety, depression, etc.), Fatigue manifestations (e.g., changes in sleep, exhaustion, etc.), Cardiovascular manifestations (blood pressure, heart rate, etc.), Gastronomical manifestations (stomach pains, cramps, etc.) and Behavioral manifestations (use of prescription drugs/alcohol, sick leave, etc.). The TSI has been found with a good psychometric property in Greek version. (Kourmousi et al., 2015) Data collected from 47 teachers in Nigeria yielded a good reliability coefficient (α = 0.81).

3.1.2. The Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale—Revised (STTS–R)

The STTS–R for group psychotherapy developed by Oei and Green (2008) was used to ascertain the participants' satisfaction with the REOHC intervention. The STTS–R is a Likert-type scale measured in a 5-point scale of Strongly Disagree (1), Disagree (2), Neutral (3), Agree (4) and Strongly Agree (5). The measure is made up of 13 items, covering the clients' satisfaction with the therapy, satisfaction with the therapist and the measure of global improvement on clients' condition. The STTS–R has been found to be of good psychometric property (Oei and Green, 2008). To validate the usability of the instrument in Nigerian context, the STTS–R was trial tested on 47 teachers in Nigeria. Crombach Alpha statistics gave an Alpha coefficient, α = 0.67, suggesting that the instrument was reliable in Nigerian teachers' population.

3.2. Participants and procedure

A total of 87 teachers who teach children with special education needs: male (n = 29) and female (n = 58) in all the public and private schools for special needs in Abia State, Nigeria participated in the study. For more demographic information of the participants see Fig. 2. Participants were included based on inclusion criteria: i) the participant must score up to 3–5 in the Single-Item Measure of Stress Symptoms, showing moderate to high-stress level; ii) the teacher must have been employed in a special Education school for not less than 1 years; iii) participant must possess personal Smart phones with a functional email address and connected to Whatsapp; iv) participant is willing to submit personal contacts and phone numbers; v) teacher signed a written consent that he/she will be available for a period of 2 h a day in a week for the intensive intervention face-to-face and online modules.

Fig. 2.

Participants demographic information.

A total of 102 teachers who volunteered to participate in the program were screened for eligibility based on the eligibility criteria stated earlier. Consequently, 15 volunteers were excluded based on not meeting the inclusion criteria or other reasons. The 87 teachers who met all the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to bREOHC group (44 participants) and wait-list control group (43 participants) (see Fig. 1) using a sequence allocation software (participants were asked to pick 1 envelope containing pressure-sensitive paper labeled with either REOHC or WLG-Waitlist Group) from a container.

Fig. 1.

Design/participants' flow chart.

Thereafter, the researcher with the help of two research assistants administered pre-test, TSI to both the REOHC group and the waitlist group (WLG) to ascertain the baseline (Time 1) data. Then, participants in the bREOHC received inter-session bREOHC intervention for a period of 12 weeks (3 months), that is, February to April 2019. During the 12 weeks, face-to-face intervention held for six periods of 2 h in alternated weeks with inter-session 2 h online interventions which held in six alternate weeks, giving a total of 12 sessions. To ensure participants' compliance, the researcher gave financial reinforcement to the participants, covering their transport and data bundle every month to enable them participate in face-to-face and online sessions. Each session was followed by a practice exercise by the participants.

Furthermore, post-test (time 2) data were collected from both bREOHC and WLG using TSI. This took place 2 weeks after the last intervention session. Aitionally, follow-up online interactions and the collection of follow-up data (Time 3 and 4) took place at 3 and 6 months after the post-test evaluation, using TSI (July and October 2019 respectively for time 3 and Time 4 data collection exercises) (see Fig. 1). All the data collection sessions held via the online the platform.

Finally, the intervention program commenced for the wait-listed group (October–December 2019). The blended rational-emotive occupational health coaching intervention was delivered and moderated by one of the researchers, together with four research assistants (2 experts in REOHC and 2 occupational therapists who were conversant with online interventions).

Fig. 2 shows the demographic information of the participants in the bREOHC group and WLG. On the whole, 29 (33.33%) of the participants were males, while 58 (66.66) were females. 15 (17.24) male and 29 (33.33) female participants were in the REOHC while 13 (14.94) male and 30 (30.00) females were in the control group. 11 (12.64%) and 13 (14.94) of the participants in REOHC and WLC groups respectively had 1–2 years of experience; 19 (21.83) and 17 (19.54) in REOHC and WLG had 3–5 years of experience, while 14 (16.09) and 13 (14.94) also had above 5 years of experience in teaching children with special needs. The mean age of the participants was 31.02 and 33.31 respectively for REOHC and WLG. A total of 49 (56.32%) participants are in primary schools while 38 (43.67%) participants were teaching in secondary schools. 25 (28.73) primary school teachers and 19 (21.83) secondary school teachers were in REOHC group, while 24 (27.58%) primary school teachers and 19 (21.83%) secondary school teachers were in the WLG. Considering qualifications, 25 (28.73%) and 26 (29.88%) had NCE in REOHC and WLG respectively; 18 (20.68%) and 17 (19.54%) participants had Bachelors' degree respectively in REOHC and WLG; 1 (1.15%) and 0 (0%) had Masters; degree and above in REOHC and WLG.

3.3. Intervention

A rational-emotive occupational health coaching program manual (Ojwang, n.d.) used in Mahfar and Senin (2013) was adapted and blended with online module and used in the study. The adapted modules utilized the “ABCDE” model (Activating event, Beliefs, Consequences, Disputing, and Effective new philosophy) to change dysfunctional and irrational beliefs associated with work experiences. The major aim of bREOHC was to use ABCDE face-to-face group therapeutic model combined with online module in “disputing” – challenging and questioning employees' work-related irrational and dysfunctional beliefs and replacing them with rather helpful and functional beliefs (Ojwang, n.d.; Ellis, 1994).

The researcher adopted the ABCDE model in explaining the relationships existing between activating (A) events associated with teaching children with ASD, dysfunctional thoughts, beliefs or cognitions arising from those events (B); the emotional and behavioral consequences of the beliefs (C) (David and Cobeanu, 2015; Ugwuanyi et al., 2020b; Onuigbo et al., 2020; Ugwuanyi et al., 2020c). Disputation involves challenging and comparing the maladaptive thoughts with more adaptive ones. This ABCDE model as used in earlier study by the first author formed the basis of activities throughout the intervention (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the blended rational emotive occupational health Coaching intervention program.

| Duration | Phase/session | Activities | Psychological mechanisms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week1–2 | Phase Face-to-face modules1–2 |

Introduction and Baseline testing | Familiarising with the participants. Setting confidentiality rules. Collection of baseline data on the job-stress of the participants. Establish a working atmosphere with the participants. Collaborating with the participants to set coaching goals. Discussing the expectations of the intervention; discussion of the coach and coaches' responsibilities during coaching and basic rules of the rational emotive occupational health coaching. |

Assessments; problem formulation/identification; goal setting |

| Week 3–4 | Phase 2 Internet modules 1 and 2 |

A-events associated with teaching autistic children | The module guides the participants to create a problem list with regards to occupational health challenges associated with teaching children with special needs. The module is designed to help participants to approach each the problems by explaining them using REBT framework. The focuses were to identify and refute unhelpful beliefs and orientations about their job which constitute stress. This was done by listing and encouraging rational beliefs and thoughts following negative experiences. Coaching was also geared towards reducing stress. Techniques described in the intervention program were strictly adhered to. Participants were given a homework assignment after each session. |

Disputation; homework tasks, discussion, Problem-solving. Rational coping statements; Unconditional self-acceptance |

| 5–6 | Face-to-face modules 3–4 | Treatment phase 2 | Coaching continued. Checking and discussing the completed homework assignment. The coach and the participants shared weekly experiences at the onset of each session. Further disputation of irrational belief associated with police occupation experience and replacing them with rational ones using the coaching modalities and techniques. Emphases were laid in developing rational self-beliefs, rational occupational health thoughts, and practices in the police, linking occupational health challenges with associated irrational beliefs. Leading the participant to find out how the belief system affect their emotions and then weakening negative affect associated occupation health of the participating officers. Homework assignments were given to the participants after each session. | Consequence analysis; Disputation; homework tasks, discussion, cognitive- restructuring |

| 7–8 | Online module 3 and 4 | Treatment Phase 3 | Further application of rational emotive occupational health coaching modalities and techniques that would develop in the participants the skills to become their own self-coach in occupational health challenges threatening their life satisfaction, happiness and positive affect as regards their occupation. Discussing healthy practices and risk management approaches in and outside the work place. Coaching on other extra-curricular activities that could keep the participants' healthy and effective in the workplace. Towards developing the habit of functional health practices and positive psychology in the work place. Assignments were given at the end of each session |

Guided imagery; rationalizing techniques; reframing; relaxation- technique; hypnosis |

| 9–10 | Face-to-face module 5–6 | Treatment phase 5 | Further helping the participant develop the skills for self-coaching and coaching others in stress management and healthy thoughts Towards developing problem-solving, rational thinking and occupational risk-management skills necessary for maintaining a healthy relationship with job |

Homework assignments; Unconditional others and self-acceptance; relaxation; decision making |

| 11–12 | Face-to-face | Treatment phase 6 | Encouraging the participant to highlight what they have gained from the coaching program and how they are going to apply them in the future. Discussing other related personal issues and experiences associated with keeping healthy in the workplace and the gain associated. Evaluation of individual commitments during the program based on contribution to group discussions and completion of assignments. | Meditation; humour and irony; decision-making; conflict resolution |

| 14th week | Post-test evaluation | Conduction post-test measurement. | Testing | |

| 3 months | Follow-up assessment | Conducting the follow-up after three months of post-test | Testing |

Hence, in bREOHC we designed a face-to-face combined with inter-session internet-based therapy in 12 modules (six face-to face modules were delivered in alternate sessions with six internet-based modules). Each of the modules includes information, exercises, worksheets, images, examples, homework exercises and template for progress feedback. Additional audio and video files are also in the internet-based sessions.

3.4. Recruitment, response rates, dropouts, and adherence

The entire 87 participant who were randomized for the study completed the sessions and evaluations. However, during the last phase of the research which was intervention for the waitlisted group, two participants did not respond to the invitation to participate. So there was high adherence rate in this study. Generally, the participants responded to both face-to-face and online contacts with few delay cases which were subsequently covered.

3.5. Design and data analyses

The current study adopted a group-randomized waitlist control trial design with pretest, post-test and follow-up assessments (Desveaux et al., 2016). Baseline data were analyzed using t-test statistics. A 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was used to compare baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up 1 and 2 data. Partial Eta square was used to report the effect-size of the intervention on the dependent measure (TSI).

Paired sample t-test was used to determine the difference in participants' ratings across Time 1and 2; Time 2 and 3; as well as Time 3 and 4. Further, 2 × 3 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) statistics was conducted to find out the interaction effects of group x Time on the study SS, SM and TSI. Percentage was used to analyze the participants' satisfaction with therapy. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 and Microsoft excel was used for analyses. Results are presents in tables and charts.

4. Results

Table 2 showed non-significant difference in the mean stress sources (SS) scores of the bREOHC group and wait-list group (WLG) at Time 1, t = 1.80, p = .993. This suggests that participant in both REOHC group and WLG had equally high sources of job-demands perception (bREOHC group = 3.54 ± 0.42; WLC = 3.38 ± 0.42). Both bREOHC group (3.50 ± 0.52) and WLG (3.49 ± 0.66) did not vary significantly in their Stress Manifestation scores at baseline, t (85) = 2.28, p = .120. On the whole, participants in both bREOHC and WLC groups did not vary significantly in their total TSI rating. A non significant difference was also recorded (t (85) = 2.16, p = .492) for bREOHC group (3.52 ± 0.45) and WLG (3.41 ± 51) in their TSI scores at baseline data. Mean scores of the two groups indicated the participants in both groups not only perceived their jobs as stressful but also experience symptoms associated with stress.

Table 2.

t-Test analysis of the baseline data on participants' TSI dimensions.

| Group | Subscale | N | SD | Df | T | P | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bREOHC group | 44 | 3.54 | 0.42 | |||||

| SS | 85, 84.99 | 1.80 | 0.993 | −0.01, 0.34 | ||||

| Wait list control | 43 | 3.38 | 0.42 | |||||

| bREOHC group | 44 | 3.50 | 0.51 | |||||

| SM | 85,78.53 | 2.28 | 0.120 | 0.03, 0.54 | ||||

| Wait list control | 43 | 3.49 | 0.66 | |||||

| bREOHC group | 44 | 3.52 | 0.45 | |||||

| TSI | 85,83,33 | 2.16 | 0.492 | 0.01, 0.43 | ||||

| Wait list control | 43 | 3.41 | 0.51 |

SS – Stress Sources; SM - Stress Manifestation; TTSIS - Total Teachers' Stress Inventory Score; - Mean, SD - Standard Deviation, df = Degree of Freedom, t = t-test statistic, p = probability value, CI – Confidence Interval.

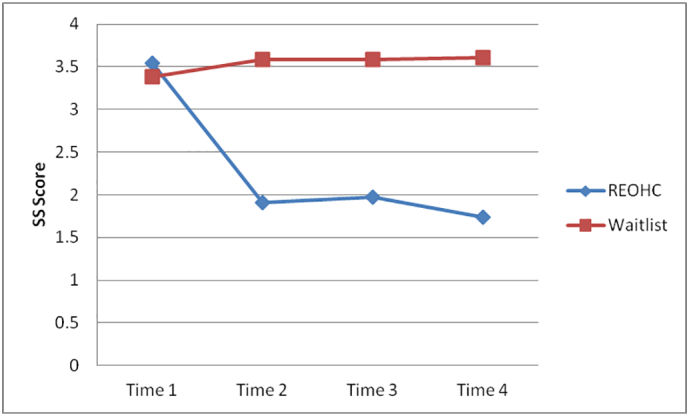

Data in Table 3 shows the repeated measures analysis of variance of the effect of the bREOHC on participant post-test, follow-up 1 and follow-up 2 ratings in SS, SM and TTSI. The results revealed significant main effects of bREOHC on stress sources, at Time 2, 3, and 4 (post-treatment) evaluations. Participants in bREOHC group (1.91 ± 0.96) had significantly (F (1, 84) = 106.69, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.56) lower mean score than WLG (3.59 ± 0.43) at Time 2 as measured by SS. There is a significant difference, F (1, 84) = 77.22, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.47 in the mean rating of participants in bREOHC (1.97 ± 1.11) and WLG (3.58 ± 0.43) as measured by SS at Time 3 evaluation. At follow-up 2 (Time 4), a significant difference, F (1, 84) = 291.74, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.77 was also shown in the mean rating of participants in bREOHC group (1.74 ± 0.58) and WLG (3.61 ± 0.38) as measured by SS. These indicated that reduced perception of stress sources among beneficiaries of bREOHC was sustained across the times of 2 follow-up evaluations at 3 and 6 months respectively.

Table 3.

Repeated measure analysis of variance of the effectiveness of the REOHC intervention on post-test, follow-up 1 and follow-up 2 scores of participants' on TSI.

| Time | Measures | bREOHC Group (n = 33) , SD |

Wait list control Group (n = 32) , SD |

Df | F | P | 95%CI | ŋ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttest (time 2) |

SS |

1.91 ± 0.96 | 3.59 ± 0.43 | 1, 84 | 106.69 | 0.000 | 1.68, 3.83 | 0.56 |

| Follow-up1 (time 3) | 1.97 ± 1.11 | 3.58 ± 0.43 | 1, 84 | 77.22 | 0.000 | 1.70, 3.86 | 0.47 | |

| Follow-up2 (time 4) | 1.74 ± 0.58 | 3.61 ± 0.38 | 1, 84 | 291.74 | 0.000 | 1.59, 3.76 | 0.77 | |

| Posttest (time 2) |

SM |

1.30 ± 0.28 | 3.56 ± 0.46 | 1, 84 | 633.03 | 0.000 | 1.28, 3.67 | 0.88 |

| Follow-up1 (time 3) | 1.59 ± 0.34 | 3.56 ± 0.46 | 1, 84 | 478.89 | 0.000 | 1.47, 3.68 | 0.85 | |

| Follow-up2 (time 4) | 1.98 ± 0.55 | 3.94 ± 0.49 | 1, 84 | 180.94 | 0.000 | 1.82, 3.70 | 0.68 | |

| Posttest (time 2) |

TTSI |

1.65 ± 0.52 | 3.58 ± 0.44 | 1, 84 | 327.02 | 0.000 | 1.51, 3.72 | 0.79 |

| Follow-up1 (time 3) | 1.78 ± 0.63 | 3.57 ± 0.44 | 1, 84 | 224.60 | 0.000 | 1.61, 3.75 | 0.72 | |

| Follow-up2 (time 4) | 1.86 ± 0.56 | 3.57 ± 0.43 | 1, 84 | 240.00 | 0.000 | 1.71, 3.73 | 0.71 |

SS – Stress Sources; SM - Stress Manifestation; TTSIS - Total Teachers' Stress Inventory Score; - Mean, SD - Standard Deviation, df = Degree of Freedom, F = Analysis of variance test statistic, p = probability value, CI – Confidence Interval and ŋ2 = Partial Eta square (effect size).

The mean rating of bREOHC group on stress manifestation (1.30 ± 0.28) reduced significantly (F (1, 84) = 633.03, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.88), compared to WLG (3.56 ± 0.46) during Time 2 measurement. This reduction in SM was sustained as there was still significant differences in the SM scores of the two groups at follow-up 1 (F (1, 84) = 478.89, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.85) and follow-up2 (F (1, 84) = 180.94, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.69). This implies that bREOHC could reduce the negative perception of occupational stress as well as stress symptoms of the participants.

Considering total score of data from the TSI at posttest (Time 1), bREOHC group lower mean rating (1.65 ± 0.52) than the waitlist (3.58 ± 0.44), which was significant (F (1, 84) = 327.02, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.79). At follow-up 1 (Time 3) TSI mean rating of the REOHC group (1.78 ± 0.63) was lower compared to the WLG (3.57 ± 0.44). This difference was significant (F (1, 84) = 224.60, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.72). Also, a significant difference (F (1, 84) = 240.00, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.71) in PSI ratings of the bREOHC group (19.61 ± 6.87) and WLG (43.13 ± 10.87) was recorded at follow-up 2 (Time 3). Also, a significant difference (F (1,21) = 31.26, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.81) was recorded in the mean SSS ratings of the bREOHC group (1.86 ± 0.56) and WLG (3.57 ± 0.43).

Independent sample t-test was conducted to explore changes in the measures across pre, post and follow-up 1 and 2 scores in bREOHC and WLC groups. The main effects of Time (baseline data, posttest, follow-up 1 and follow-up 2) were significant with respect to the SS, F (82) = 278.88, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.78 (see Fig. 2), SM, F (2, 82) = 244.15, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.90 (Fig. 3) and TSI scores F (2, 82) = 256.00, p = .000, ŋ2 = 0.82 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Interaction effect of time and intervention on participants' SS scores.

Fig. 4.

Interaction effect of time and intervention on participants' SM scores.

bREOHC group recorded a significant decreases in SS scores between Time 1 and 2 (t (86) = 5.501, p = .000, CI = 0.45, 0.98) and non-significant differences in Time 2 and 3 (t (86) = −0.270, p = .78, CI = −0.23, −0.18) and Time 3 and 4 (t (86) = 1.126, p = .263, CI = 0.097, −0.084) scores. On the other hand, WLC group did not have significant change across Time 1–2 (t (86) = −0.311, p = .631, CI = −0.35, −0.09); 2–3 (t (86) = −0.167, p = .319, CI = 0.085, −0.073); and 3–4 (t (86) = 1.300, p = .311, CI = 0.071, −0.067). This indicates that the reduction in REOHC group's SS score from pre-test to posttest was sustained through 3 and 6 months follow-up (see Fig. 3).

In respect of SM, there was also significant reduction in SM scores across Time 1 and 2 (t (86) = 5.81, p = .000, CI = 0.58, 1.20) but non-significant differences in Time 2 and 3 (t (86) = −3.09, p = .312, CI = −0.16, −0.03); and Time 3 and Time 4 (t (66) = −4.27, p = .567, CI = −0.27, −0.09) in the REOHC group. On the contrary, participant in the WLC group did not vary significantly in their SM scores across Time 1–2 (t (86) = −4.01, p = .301, CI = −0.17, −0.04); 2–3 (t (86) = −1.99, p = .193, CI = −0.17, −0.27); and 3–4 (t (86) = −6.27, p = .873, CI = −0.39, −0.07). This suggest that the reduced stress manifestation at posttest was a product of interaction effect of the coaching intervention and was sustained across 3 and 6 months follow-up (see Fig. 4).

Participants also had significant reduction in overall TSI scores across Time 1 and 2 (t (86) = 5.95, p = .000, CI = 0.53, 1.07); but not significant across Time 2–3 (t (86) = −1.08, p = .280, CI = −0.18, −0.05) and Time 3–Time 4 (t (86) = −0.624, p = .534, CI = −0.15, 0.08). On the other hand, participants in the WLC group did not record significant changes in their TSI scores across Time 1–2 (t (86) = −2.17, p = .313, CI = −0.17, −0.02); Time 2–3 (t (86) = −2.09, p = .550, CI = −0.18, −0.02); and Time 3–4 (t (86) = −4.12, p = .614, CI = −0.19, −0.07) (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Interaction effect of time and intervention on participants' TSI scores.

To further validate the efficacy of the bREOHC on participants' emotions, we collected data on the participants' satisfaction with the therapy. Data collected in this respect are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 5. Data in Table 3 show the participants satisfaction with the REOHC intervention program. Majority of the participants [81 (93.1%)] reported a high degree of satisfaction with the quality of the therapy received. [76 (87%)] reported high degree of their satisfaction with the therapists and [68 (78.2%)] scored high in their global improvement with the bREOHC intervention (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency and percentage of participants' satisfaction with therapy.

| S/N | Item | Low |

Moderate |

High |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | % | F | % | F | % | ||

| 1 | Satisfaction with the therapy | 2 | 2.3 | 4 | 4.6 | 81 | 93.1 |

| 2 | Satisfaction with the therapists | 0 | 0 | 11 | 12.6 | 76 | 87.4 |

| 3 | Global improvement on clients' condition | 1 | 1.1 | 18 | 20.7 | 68 | 78.2 |

| 4 | Overall STTS–R score | 1 | 1.1 | 11 | 12.6 | 75 | 86.2 |

Majority of the participants [75 (86.2%)] were highly satisfied with the bREOHC program as measured by Overall STTS–R score. These attest to the efficacy of bREOHC on teachers' stress management. The Fig. 6 further illustrates data pertaining to this result.

Fig. 6.

Bar chart showing participants' satisfaction with therapy.

5. Discussion

The current study sought to validate the effectiveness of bREOHC in reducing job- stress among teachers of children with special needs. Results showed that bREOHC and wait-list groups (WLG) did not vary significantly in their Stress Sources (SS), stress manifestation (SM) and the Total Teachers' Stress Inventory (TTSI) scores at baseline evaluation. The bREOHC intervention led to a significant reduction in all dimensions of teachers' stress (SS, SM and TTSI) of bREOHC group at Time 2 (post-test) which were sustained through Time 3 (follow-up 1) and Time 4 (follow-up 1) compared to the WCG. Result further showed that a significant interaction effect of Time and intervention on the measures of participants' stress, indicating that the reduction in the bREOHC group's stress scores across time was strictly due to bREOHC intervention and not due to change in time. While stress scores of the WLG did not vary significantly across baseline, post-intervention and follow-up evaluations, the bREOHC group reported a significant reduction in their stress between baseline and post treatment evaluations. This indicates that. Further results show high participants satisfaction with the bREOHC intervention. About 93% of the bREOHC participants reported their high satisfaction with therapy, 87.4% reported high satisfaction with the therapists and 78.2% reported high global improvement on their condition. This indicates that bREOHC alters the coaches' self-defeating cognitions associated with the work experiences.

The significant reduction in the teachers stress through bREOHC shows that even when the objective working conditions remain constant, a teacher through bREOHC can change his/her perceptions about stressful experiences associated with teaching children with such kinds of disabilities, leading to reduced stress symptoms. The ability of internet-based programs to sustain treatment benefits post-discharge from face-to-face treatment is also established (Kenter et al., 2015). Furthermore, going by the three models of stress- stimulus-based, response-based and transaction-based models (Papathanasiou et al., 2015; Corina et al., 2014; Tatar et al., 2018a), it is expected that the three models could be explained using the ABCDE therapeutic modalities, thereby bringing about relieve on the part of the teachers. The stimulus based model of stress proposes that stress occurs when there is objective activating events (A), called stressors; while response-based model suggest that stress emotional, physiological and behavioral reactions (C) towards the stressor (A). Finally, transaction-based suggest that stress is a consequence (C) of the negative subjective interpretation/cognitions perspective (B) of activating situation/stress (A) (Ogba et al., 2019; Reddy and Anuradha, 2013; Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a; Onyishi et al., 2020; Mathiasen et al., 2016; Onuigbo et al., 2018). Thus bREOHC works by disputing (D) the negative and dysfunctional perception ‘B’ about the stressful situation ‘A’ and replacing them with the healthier ones (E). This could cause significant reduction in the cognitive physical and/or emotional impacts on health and well-being (C) (Kebbi, 2018; Atiyat, 2017; Gersten et al., 2001; Kuvaeva, 2018; Bush, 2010). bREOHC helps the clients to develop self-evaluation strategies that equip them to understand their own thoughts in order to deal positively with them (Ogba et al., 2019; Ogba et al., 2020) Thus, supporting works on REOHC (Ogba et al., 2019; Ogba et al., 2020; Kenter et al., 2015), blended modality (bREOHC) is successful in improving occupational stress management among school administrators and other psychological disorders.

Earlier study (Tatar et al., 2018b) showed that a positive change in perception of stress can lead to a reduction in physiological and psychological symptoms associated with job-stress. Other Nigerian studies showed that REOHC was effective in stress management (Ogba et al., 2020; Ellis, 1995) and subjective well-being (Mahfar and Senin, 2013) of employees. However, to the best of our knowledge, the finding of the current study is a new finding that has not been observed previously, given that all previous studies on REOHC are face-to-face. None of the stated works on REOHC was blended with online treatment sessions. Hence, the present findings serve as base for further studies and researchers are encouraged to replicate and confirm in other studies using blended treatment format. Results of the present study also strengthen other studies on blended approaches using other psychotherapeutic modalities such as CBT/REBT (Mackie et al., 2017; Ugwuanyi et al., 2020a; van de Wal et al., 2017; Kooistra et al., 2016; Romijn et al., 2015; Rasing et al., 2019; Kenter et al., 2015; Berto, 2014; Zwerenz et al., 2017; Titzler et al., 2018) which have yielded positive results.

A high participant's satisfaction with the bREOHC intervention was recorded in the study. Few studies have assessed satisfaction with blended treatments for psychological disorders, in respect of treatment preferences, expectations, usability, and satisfaction (Mathiasen et al., 2016; Wentzel et al., 2016; Kemmeren et al., 2016). Simon et al. (2019) (Etzelmueller et al., 2018) based on review of empirical studies found internet-based CBT to be acceptable to participants. Other studies (Mackie et al., 2017; Desveaux et al., 2016) found a high degree of satisfaction with the therapy and study procedures. In blended therapy, online sessions offer participants unrestricted access to treatment materials and exercises at the comfort of their own home thereby reducing the cost and frequency of meetings (Kenter et al., 2015; Kemmeren et al., 2016). Additionally, blended therapy reduces therapist time compared to only face-to-face sessions, yet offers the benefit of face-to-face therapeutic relationship, which is very necessary in psychotherapy (Kenter et al., 2015).

Reducing work-place stress reduces psychopathological symptoms such as headache, anxiety and musculoskeletal problems (Ojwang, n.d.; Ogba et al., 2019; Ogba et al., 2020) that could undermine employees' effectiveness. As such reduction of stress in teachers could reducing negative health conditions and increases their classroom effectiveness (Sukumar and Kanagarathinam, 2016; Okwaraji and Aguwa, 2015; Kuvaeva, 2018). The improvement in teachers' effectiveness translates to positive outcomes in children with special needs kept under their care. Furthermore, negative thoughts and emotional stress reactions tend to reduced productivity and increase health challenges (Gersten et al., 2001; David and Matu, 2013; McCraty et al., 2003; Gharib et al., 2016; Gitonga and Ndagi, 2016). Additionally, bREOHC is a cost-effective scheme improving teachers' wellbeing and positive outcomes in students with special education needs (Ojwang, n.d.).

5.1. Limitations of the study

Due to the relatively small sample used in this study, the outcome cannot be generalized outside the context. Further study could apply larger sample to confirm the effectiveness of the bREOHC. The package (bREOHC) may also be tried in different populations of employees with chronic stress. The present study did not compare blended with face-to-face REOHC. Information about the relative efficacy is needed for future decision making about the best approach. Future studies may be designed to compare bended and traditional face-to-face REOHC as the current study did not consider the area.

5.2. Practical implications

Coaching practitioners working with teachers of can consider bREOHC in managing stress for intervention needful for teachers of children with special education needs. Experts in school occupational health and behavioral coaching should adopt bREOHC in handling teachers of special needs learners who have moderate and/or severe stress associated with their work.

6. Conclusion

From the findings of this study, we conclude that blended REOHC is efficacious in stress management among teachers of children with special education needs. We further conclude that the clients who receive bREOHC are satisfied about the intervention. The BREOHC is cost and time effective and could be utilized across contexts.

Funding

No funding was received for the study.

Data accessibility statement

Study data were not deposited in any repository, but can be accessed from the corresponding author on demand.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the research assistants and therapists who aided the research processes, and the parents who participated in the study.

Contributor Information

Francisca Chinwendu Okeke, Email: francisca.okeke@unn.edu.ng.

Charity N. Onyishi, Email: charity.onyishi@unn.edu.ng.

Paulinus P. Nwankwor, Email: paulinus.nwankwo@unn.edu.ng.

Stella Chinweudo Ekwueme, Email: stella.ekwueme@unn.edu.ng.

References

- AbuMadini M.S., Sakthivel M.A. Comparative study to determine the occupational stress level and professional burnout in special school teachers working in private and government schools. 2018;10:3. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v10n3p42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arun P., Garg R., Chavan B.S. Stress and suicidal ideation among adolescents having academic difficulty. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2017;26(1):64. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_5_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah-Appiah W., Aggrey-Fynn I. The impact of occupational stress on employee's performance: a study at Twifo oil palm plantation limited. Afr. J. Appl. Res. 2017;3(1):14–25. Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- Atiyat O.K. The level of psychological burnout at the teachers of students with autism disorders in light of a number of variables in Al-Riyadh area. 2017;6(4):159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Berto R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restrictiveness. 2014;4(4):394–409. doi: 10.3390/bs4040394. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush L.D. Washington State University; 2010. Special Education Teachers and Work Stress: Exploring the Competing Interests Model. May. [Google Scholar]

- Cappe E., Bolduc M., Poirier N., Popa-Roch M.A., Boujut E. Teaching students with autism Spectrum disorder across various educational settings: the factors involved in burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017;1(67):498–508. Oct. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha M., Sood K., Malhotra S. Effect of organizational stress on quality of life of primary and secondary school teachers. 2012;15:342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Corina D.C., Patacchioli F.R., Ghiciuc C.M., Szalontay A., Florin M.I., Azoicai D. Current perspectives in stress research and cardiometabolic risk. 2014;1(45):175. Jun. [Google Scholar]

- Dankade U., Bello H., Deba A.A. Analysis of job stress affecting the performance of secondary schools' vocational technical teachers in north east, Nigeria. J. Tech. Educ. Train. 2016;8(1) Jun 28. [Google Scholar]

- David O.A., Cobeanu O. Evidence-based training in cognitive-behavioral coaching: does personal development bring less distress and better performance? Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2015 doi: 10.1080/03069885.2014.1002384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David O.A., Matu S.A. How to tell if managers are good coaches and how to help them improve during adversity? The managerial coaching assessment system and the rational managerial coaching program. J. Cogn. Behav. Psychother. 2013;13:259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Davis F. Stellenbosch University; Stellenbosch: 2021. Stress and Coping Skills of Educators with a Learner with a Physical Disability in Inclusive Classrooms in the Western Cape. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Desveaux L., Agarwal P., Shaw J., et al. A randomized wait-list control trial to evaluate the impact of a mobile application to improve self-management of individuals with type 2 diabetes: a study protocol. 2016;16(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. Birch Lane Press; New York: 1994. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy Revised and Updated. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. Changing rational-emotive therapy (RET) to rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 1995;13(2):85–89. Jun 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. Albert Ellis Institute New York; 2014. The empirical status of Rational Emotif Behavior Therapy (Rebt) theory & practice.http://albertellis.orgpdf_filesThe-Empirical-Status-of-Rational-Emotive-Behavior-Theory-and-Therapy.pdf Retrieved on 31 January 2016 at. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A., MacLaren C. Impact Publishers; 1998. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy: A Therapist's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Etzelmueller A., Radkovsky A., Hannig W., Berking M., Ebert D.D. Patient's experience with blended video-and internet based cognitive behavioural therapy service in routine care. Internet Interv. 2018;1(12):165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.01.003. Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Assembly of the World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J. Am. Coll. Dent. 2020;81(3):14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersten R., Keating T., Yovanoff P., Harniss M.K. Working in special education: factors that enhance special educators' intent to stay. Except. Child. 2001;67(4):549–567. Apr. [Google Scholar]

- Gharib M., Jamil S.A., Ahmad M., Ghouse S.M. The impact of job stress on job performance: a case study on academic staff at Dhofar University. 2016;13:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gitonga M.K., Ndagi J.M. Influence of occupational stress on teachers' performance in public secondary schools in Nyeri County, Nyeri South Sub County Kenya. 2016;5:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlett C. How stress affects your work performance. 2016. smallbuisnes.chron.com/stress-affects-your-work-performance-18040.html Retrieved from. on 14/11/2016.

- Hashim C.N., Kayode B.K. Stress management among administrators and senior teachers of private Islamic school. J. Glob. Bus. Manag. 2010;6(2):1. Dec 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kebbi M. Stress and coping strategies used by special education and general classroom teachers. 2018;33(1):34–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmeren L.L., Van Schaik D.J., Riper H., Kleiboer A.M., Bosmans J.E., Smit J.H. Effectiveness of blended depression treatment for adults in specialised mental healthcare: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. 2016;16(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0818-5. Dec 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenter R.M., van de Ven P.M., Cuijpers P., Koole G., Niamat S., Gerrits R.S., Willems M., van Straten A. Costs and effects of internet cognitive behavioral treatment blended with face-to-face treatment: results from a naturalistic study. Internet Interv. 2015;2(1):77–83. Mar 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra L.C., Ruwaard J., Wiersma J.E., van Oppen P., van der Vaart R., van Gemert-Pijnen J.E., Riper H. Development and initial evaluation of blended cognitive behavioural treatment for major depression in routine specialized mental health care. Internet Interv. 2016;1(4):61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.01.003. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra L.C., Wiersma J.E., Ruwaard J., Neijenhuijs K., Lokkerbol J., van Oppen P., Smit F., Riper H. Cost and effectiveness of blended versus standard cognitive behavioral therapy for outpatients with depression in routine specialized mental health care: pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(10) doi: 10.2196/14261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourmousi N., Darviri C., Varvogli L., Alexopoulos E.C. Teacher Stress Inventory: validation of the Greek version and perceived stress levels among 3,447 educators. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015;8:81. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S74752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuvaeva I. Teachers of special schools: stressors and manifestations of occupational stress. 2018;1:515–521. Nov. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie C., Dunn N., MacLean S., Testa V., Heisel M., Hatcher S. A qualitative study of a blended therapy using problem solving therapy with a customised smartphone app in men who present to hospital with intentional self-harm. 2017;20(4):118–122. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102764. Nov 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfar M., Senin A.A. 2013. Managing stress at workplace using the rational-emotive behavioral therapy (REBT) [Google Scholar]

- Major A.E. Job design for special education teachers. 2012;15:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Malik N.A., Björkqvist K. Occupational stress and mental and musculoskeletal health among university teachers. 2018;2(3):139–147. doi: 10.14744/ejmi.2018.41636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manabete S.S., John C.A., Makinde A.A., Duwa S.T. Job stress among school administrators and teachers in Nigerian secondary schools and technical colleges. 2016;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiasen K., Andersen T.E., Riper H., Kleiboer A.A., Roessler K.K. Blended CBT versus face-to-face CBT: a randomised non-inferiority trial. 2016;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1140-y. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCraty R., Atkinson M., Tomasino D. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2003;9(3):355–369. doi: 10.1089/107555303765551589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan C.P. 2017. AM Happy Scale: Reliability and Validity of a Aingle-item Measure of Happiness.http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/438 Available at. [accessed on December 2017] [Google Scholar]

- Oei T.P., Green A.L. The Satisfaction With Therapy and Therapist Scale-Revised (STTS-R) for group psychotherapy: psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2008;39(4):435. Aug. [Google Scholar]

- Ogba F.N., Onyishi C.N., Ede M.O., Ugwuanyi C., Nwokeoma B.N., Victor-Aigbodion V., Eze U.N., Omeke F., Okorie C.O., Ossai O.V. Effectiveness of SPACE model of cognitive behavioral coaching in management of occupational stress in a sample of school administrators in South-East Nigeria. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019;27:1–24. Nov. [Google Scholar]

- Ogba F.N., Onyishi C.N., Victor-Aigbodion V., Abada I.M., Eze U.N., Obiweluozo P.E., Ugodulunwa C.N., Igu N.C., Okorie C.O., Onu J.C., Eze A. Managing job stress in teachers of children with autism: a rational emotive occupational health coaching control trial. Medicine. 2020;99(36) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojwang H.A. University of Nairobi; Kenya: 2021. Prevalence of Occupational Stress Among Employees in the Civil Service in Nairobi and Their Perceived Coping Styles. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Okwaraji F.E., Aguwa E.N. Burnout, psychological distress and job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Enugu,South East Nigeria. 2015;18(1):237–245. doi: 10.4172/2378-5756.1000198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onuigbo L.N., Eseadi C., Ugwoke S.C., Nwobi A.U., Anyanwu J.I., Okeke F.C., Agu P.U., Oboegbulem A.I., Chinweuba N.H., Agundu U.V., Ololo K.O. Effect of rational emotive behavior therapy on stress management and irrational beliefs of special education teachers in Nigerian elementary schools. Medicine. 2018;97(37) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012191. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuigbo L.N., Onyishi C.N., Eseadi C. Clinical benefits of rational-emotive stress management therapy for job burnout and dysfunctional distress of special education teachers. 2020;8(12):2438. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2438. Jun 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyishi C.N., Ede M.O., Ossai O.V., Ugwuanyi C.S. Rational emotive occupational health coaching in the management of police subjective well-being and work ability: a case of repeated measures. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2020:1–16. Jan. [Google Scholar]

- Onyishi C.N., Sefotho M.M. Teachers' perspectives on the use of differentiated instruction in inclusive classrooms: implication for teacher education. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020;9(6):136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanasiou I.V., Tsaras K., Neroliatsiou A., Roupa A. Stress: concepts, theoretical models and nursing interventions. 2015;4(2–1):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K., Shisana O., Zuma K., Van Wyk B., Zungu-Dirwayi N. Job stress, job satisfaction and stress-related illnesses among South African educators. Stress Health. 2009;25(3):247–257. doi: 10.1002/smi.1244. Aug. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Morales A.J., Adan A., Forero D.A. Perceived stress as a mediator of the relationship between neuroticism and depression and anxiety symptoms. Curr. Psychol. 2017;1–9 [Google Scholar]

- Rasing S.P., Stikkelbroek Y.A., Riper H., Dekovic M., Nauta M.H., Dirksen C.D., Creemers D.H., Bodden D.H. 2019;8(10) doi: 10.2196/13434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G.L., Anuradha R.V. Occupational stress of higher secondary teachers working in Vellore district. 2013;3(1):9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Romijn G., Riper H., Kok R., Donker T., Goorden M., van Roijen L.H., Kooistra L., van Balkom A., Koning J. Cost-effectiveness of blended vs. face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for severe anxiety disorders: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. 2015;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0697-1. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon N., McGillivray L., Roberts N.P., Barawi K., Lewis C.E., Bisson J.I. Acceptability of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (i-CBT) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1646092. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1646092. Dec 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumar M.A., Kanagarathinam M. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2016;2(5):90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Suleman Q., Hussain I., Shehzad S., Syed M.A., Raja S.A. Relationship between perceived occupational stress and psychological well-being among secondary school heads in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. 2018;13(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208143. Dec 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Sumathy V., Sudha G. Teachers' stress and type of school: is there link? 2013;11(4):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tatar A., Saltukoğlu G., Özmen E. Development of a self report stress scale using item response theory-I: item selection, formation of factor structure and examination of its psychometric properties. 2018 Jun;55(2):161. doi: 10.5152/npa.2017.18065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar A., Saltukoğlu G., Özmen E. 2018 Jun;55(2):161. doi: 10.5152/npa.2017.18065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titzler I., Saruhanjan K., Berking M., Riper H., Ebert D.D. Barriers and facilitators for the implementation of blended psychotherapy for depression: a qualitative pilot study of therapists' perspective. Internet Interv. 2018;12:150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.01.002. Jun 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugwoke S.C., Eseadi C., Onuigbo L.N., et al. A rational-emotive stress management intervention for reducing job burnout and dysfunctional distress among special education teachers: an effect study. Medicine. 2018;97(17) doi: 10.1007/s10942-014-0200-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugwuanyi C.S., Ede M.O., Onyishi C.N., Ossai O.V., Nwokenna E.N., Obikwelu L.C., Ikechukwu-Ilomuanya A., Amoke C.V., Okeke A.O., Ene C.U., Offordile E.E. Effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy with music therapy in reducing physics test anxiety among students as measured by generalized test anxiety scale. Medicine. 2020 Apr 1;99(17) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugwuanyi C.S., Gana C.S., Ugwuanyi C.C., Ezenwa D.N., Eya N.M., Ene C.U., Nwoye N.M., Ncheke D.C., Adene F.M., Ede M.O., Onyishi C.N. Efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy on academic procrastination behaviours among students enrolled in Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics Education (PCME) J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020:1–8. Apr 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwuanyi C.S., Gana C.S., Ugwuanyi C.C., Ezenwa D.N., Eya N.M., Ene C.U., Nwoye N.M., Ncheke D.C., Adene F.M., Ede M.O., Onyishi C.N. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020 Apr;22:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ukonu I.O., Edeoga G. Job-related stress among public junior secondary school teachers in Abuja, Nigeria. 2019;9(1):2162–3058. doi: 10.5296/ijhrs.v9i1.13589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wal M., Thewes B., Gielissen M., Speckens A., Prins J. Efficacy of blended cognitive behavior therapy for high fear of recurrence in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: the SWORD study, a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35(19):2173–2183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5301. Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernmark K., Hesser H., Topooco N., Berger T., Riper H., Luuk L., Backlund L., Carlbring P., Andersson G. Working alliance as a predictor of change in depression during blended cognitive behaviour therapy. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019;48(4):285–299. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1533577. Jul 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Embse N.P., Kilgus S.P., Solomon H.J., Bowler M., Curtiss C. Initial development and factor structure of the Educator Test Stress Inventory. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2015;33(3):223–237. Jun. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel J., van der Vaart R., Bohlmeijer E.T., van Gemert-Pijnen J.E. Mixing online and face-to-face therapy: how to benefit from blended care in mental health care. 2016;3(1) doi: 10.2196/mental.4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Liu L., Zhang X., Li B., Cui R. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015 Jul 1;13(4):494–504. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1304150831150507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Liu L., Zhang X., Li B., Cui R. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015 Jul 1;13(4):494–504. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1304150831150507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf F.A., Olufunke Y.R., Valentine M.D. Causes and impact of stress on teachers' productivity as expressed by primary school teachers in Nigeria. Creat. Educ. 1937–1942;6:2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zarafshan H., Mohammadi M.R., Ahmadi F., Arsalani A. Job burnout among Iranian elementary school teachers of students with autism: a comparative study. Iran. J. Psychiatry. 2013;8(1):20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwerenz R., Becker J., Knickenberg R.J., Siepmann M., Hagen K., Beutel M.E. Online self-help as an add-on to inpatient psychotherapy: efficacy of a new blended treatment approach. Psychother. Psychosom. 2017;86(6):341–350. doi: 10.1159/000481177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Study data were not deposited in any repository, but can be accessed from the corresponding author on demand.