Abstract

Many methods for rare variant association studies require permutations to assess the significance of tests. Standard permutations assume that all individuals are exchangeable and do not take population stratification (PS), a known confounding factor in genetic studies, into account. We propose a novel strategy, LocPerm, in which individual phenotypes are permuted only with their closest ancestry-based neighbors. We performed a simulation study, focusing on small samples, to evaluate and compare LocPerm with standard permutations and classical adjustment on first principal components. Under the null hypothesis, LocPerm was the only method providing an acceptable type I error, regardless of sample size and level of stratification. The power of LocPerm was similar to that of standard permutation in the absence of PS, and remained stable in different PS scenarios. We conclude that LocPerm is a method of choice for taking PS and/or small sample size into account in rare variant association studies.

Keywords: Rare variant association study, Permutation, principal components, small samples, population stratification

Introduction

Population stratification (PS) is a classic confounding factor in genetic association studies of common variants (Price et al., 2010). Principal component analysis (PCA) (Patterson, Price, & Reich, 2006; Price et al., 2006) and Linear Mixed Models (LMM) (Kang et al., 2010; W. Zhou et al., 2018; X. Zhou & Stephens, 2012) are the most widely used approach to correct for stratification in this context. PS also affects association studies involving rare variants in the context of next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses (Mathieson & McVean, 2012; O’Connor et al., 2013; Tintle et al., 2011). When dealing with rare variants, one common strategy to preserve power consists in aggregating genotypes from several variants belonging to the same genetic unit (e.g. protein-coding gene) in a specific test statistic (Lee, Abecasis, Boehnke, & Lin, 2014). In this context, the use of principal components (PCs) computed from common variants as covariates in a regression framework to test for association has been widely investigated (Price et al., 2006; Zhang, Guan, & Pan, 2013) and were shown to yield satisfactory correction in a number of settings, while being subject to several limitations, particularly in cases of complex population structure(Liu, Nicolae, & Chen, 2013; Mathieson & McVean, 2012). It has been suggested that more fine substructure could be detected using rare variants (Baye et al., 2011). However, several studies comparing the performance of the PC-based approach using either common or rare variants showed greater performance of common variants (Ma & Shi, 2020; Zhang, Guan, et al., 2013; Zhang, Shen, & Pan, 2013). In addition, the regression framework implicitly assumes an asymptotic distribution of the test statistics, which is rarely achieved when sample size is small (Bigdeli, Neale, & Neale, 2014), and few studies of PC-based correction in this context have been published (Jiang, Epstein, & Conneely, 2013). More recently, mixed models approaches have been proposed to account for population stratification in rare variant association studies (Chen et al., 2019; W. Zhou et al., 2020). However, none of them were investigated in the context of the analysis of small samples (e.g. less than 300).

Permutation methods (particularly the derivation of an empirical distribution by the random permutation of phenotype labels) are classically used in strategies for deriving p-values from a test statistic with a probability distribution that is unknown or from which it is difficult to sample (Good, 1994). However, this approach assumes that all individuals are equally interchangeable under the null hypothesis, an assumption that is not valid in the presence of PS (Good, 2002). When ancestry is known, it is reasonable to ensure that permutations result exclusively in the exchange of phenotypes between individuals of the same ancestry, but this information is rarely available in practice. We investigated the impact of PS on association studies based on rare variants and aggregated test statistics in the context of limited sample sizes, a situation frequently observed in rare disorders. We propose a new method, LocPerm, based on population-adapted permutation and taking into account the genetic distance between individuals. We describe a detailed analysis of its properties with respect to PC adjustment and standard permutation.

Materials and methods

a. The LocPerm procedure

When dealing with permutation, P-values are usually defined as the proportion of permuted test statistics at least as extreme as the observed one. However, it makes the hypothesis that all individuals are exchangeable which is not the case in the presence of population structure. Under the null hypothesis, individuals with the same ancestry are more likely to share the same phenotype than individual from different ancestries. Here we propose a new approach, LocPerm, in which permutation is restricted such that the phenotype of each individual can be exchanged only with one of its nearest neighbors in terms of a PC-based genetic distance. The neighborhood of each sample is the set of relatively close samples with whom it is reasonable to exchange phenotypes, based on the genetic distance derived from the sample coordinates along principal component axes calculated on common variants. The genetic distance between two individuals i and j was computed as , where PC is the matrix of principal components (PCs) calculated on common variants and λk the eigenvalue corresponding to the k-th principal component PCk. We ended the summation at the 10th component since the proportion of explained variance was very high and the resulting distance would be only slightly modified with additional components.

We set a number N and only allow permutation that ensure that each phenotype is drawn from the N nearest neighbors, in the sense of the genetic distance. A permutation satisfying this constraint is called a restricted (or local) permutation. To generate a list of such restricted permutation, we consider a random walk in the set of restricted permutations. We start with the identity permutation (i.e. every phenotype is leaved unchanged), that clearly satisfies the constraint. At each step, the following modification is performed: the phenotype of individual i is randomly exchanged with another one (possibly himself), in such a way that the resulting permutation still satisfies the original constraint. This elementary step is repeated for every individual i and the resulting permutation is the next step of the Markov chain, whose stationary and limit distribution is the uniform distribution on restricted permutations. We used a burn-in of 100 iterations (i.e. the first 100 permutations are dropped) and a step of 10 to ensure relative independence between to permutation in the list (i.e. only 1 iteration out of 10 outputs of the Markov chain are considered). As shown in the results section, the procedure was rather stable within a large range of N values and we used N=30 in the simulation study.

b. Full- and semi-empirical p-value derivation

In the context of permutation tests, p-values are usually defined as the proportion of permuted test statistics at least as extreme as the observed one. To account for a possible discrete distribution of test statistics in the context of small samples, we adapted this procedure and draw the p-value from a uniform distribution U([a,b]), where a (respectively b) stands for the observed proportion of test statistics more (respectively at least as) extreme as the observed one. This strategy is further referred to as full-empirical and requires a large number of permutations to achieve a good precision in the estimation of small p-values. Here, we used 5000 permutations.

As an alternative, we propose a semi-empirical approach in which a limited number of resampled statistics are used to estimate parameters of the test statistic distribution. In the semi-empirical approach, a limited (N = 500) number of resampled statistics are used to estimate the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of the test statistic under H0. Assuming that the test statistic follows a normal distribution, we can then compute the p-value corresponding to an observed statistic by using the distribution. This approach allows a better precision in the p-value estimation, or permutation sparing, provided that the underlying hypothesis on the distribution is true.

c. Rare variant association test

A number of methods have been proposed to test for the association between rare variants and a phenotype which are based on the aggregation of rare variants within a genetic unit, e.g. protein coding genes, and we focused on two classical methods: i) the “cohort allelic sum test” (CAST) (Morgenthaler & Thilly, 2007), in which rare variants within a genetic unit are collapsed into a binary score taking the value of 0 in the absence of rare variant and 1 in the presence of at least one rare variant, and ii) the variance-component “sequence kernel association test” (SKAT) approach (Wu et al., 2011). We implemented the CAST approach in the logistic regression framework in R and used the Likelihood Ratio test (LRT) statistic. For SKAT, we used the SKAT_Null_Model and SKAT functions implemented in the SKAT R package with the default parameters including the small sample adjustment. As a reference method to account for population stratification we included the first ten PCs of the PCA on common variants in the association model (denoted as CAST-10PC and SKAT-10PC). P-values from CAST and SKAT were derived either from their theoretical statistic distribution or from permutations. We used either standard permutations (denoted as CAST-perm and SKAT-perm), where the phenotype of each individual can be permuted with the one of any other sample, or the LocPerm approaches (denoted as CAST-LocPerm and SKAT-LocPerm). For LocPerm with semi empirical (LocPerm-SE) p-value derivation, the CAST-LRT statistic, which asymptotically follows a chi-square distribution under the null, was transformed into a Z-score by taking the square root and signing according to the direction of effect. Given the more complex theoretical distribution of the SKAT statistic we did not implement the LocPerm-SE approach for SKAT.

d. Simulation study

For the simulation study, we used two real NGS datasets (public and in-house), in order to have realistic site frequency spectrum and LD structure. The in-house dataset, referred as HGID (Human Genetic of Infectious Diseases Database), is composed of 3,104 WES data generated with the exome capture kit SureSelect Human All Exon V4+UTRs (https://agilent.com). All study participants provided written informed consent for the use of their DNA in studies aiming to identify genetic risk variants for disease. IRB approval was obtained from The Rockefeller University and Necker Hospital for Sick Children, along with a number of collaborating institutions. The public dataset is composed of 2,504 whole-genomes from the 1000 genome phase 3 (http://www.internationalgenome.org/). We first merged the two datasets and extracted only the exonic regions captured by the Agilent V4+UTRs capture kit. We performed genotype and variant level quality control to focus only on high quality coding variants defined as having a depth of coverage (DP) > 8, a genotype quality (GQ) > 20, a minor read ratio (MRR) > 0.2 and a call-rate > 95% (Belkadi et al., 2015). We then excluded all related individuals up to the second degree based on the kinship coefficient (King’s kinship K > 0.09375 (Anderson et al., 2010; Manichaikul et al., 2010)) leading to a total of 4,887 unrelated samples. From the whole dataset, we selected samples of European ancestry including all individuals with a reported European ancestry from 1000 genomes (i.e. CEU, TSI, FIN, GBR and IBS) and HGID cohorts. In addition, we included samples with unknown recorded ancestry from HGID but with a genetic distance to the randomly selected sample HG00146 form the 1000 genomes GBR population lower than the maximum genetic distance observed between HG00146 and other samples with known European ancestry. This led to final sample of 1523 European individuals.

We empirically separated this European sample in three parts according to their ancestry based on the PCA (efigure 1): 127 individuals of Northern ancestry (mainly including the 1000 genomes FIN samples), 651 of Middle-Europe ancestry (including the 1000 genomes CEU and GBR samples) and 745 of Southern ancestry (including the 1000 genomes TSI and IBS samples). Cases and controls samples were simulated under three stratification scenario: 1) no stratification scenario where cases were equally distributed across the three sub-populations (i.e. 1/3 of cases were randomly selected from each sub-population); 2) intermediate stratification scenario where 5/6 of cases came from Southern Europe, 1/6 from Middle Europe and Northern Europe; and 3) extreme stratification where all cases came from Southern Europe. In all scenarios, controls were equally distributed across the three sub-populations (i.e. 1/3 of controls were randomly selected from each sub-population).

Under the null hypothesis of no genetic association, samples of 30, 60 or 120 cases and 60, 120 or 180 controls were randomly drawn from the source population according to the three stratification scenario. We also generated random samples of 381 cases and 1142 controls representing the whole source population. For each configuration, we generated 15 replicates and performed the analysis of all protein coding genes using CAST- or SKAT-based approaches on rare variants defined as having a MAF ≤ 0.05 in the source population. Only genes with at least 10 carriers of a rare variant in the analyzed sample were considered. The type I error rate at nominal level α was computed as the number of p-values equal or lower than α divided by the total number of genes tested over the 15 replicates.

For the power analysis, we selected three genes, RORC, RABGAP1L and SAMD11 with a proportion of the source population carrying at least one rare variant (MAF≤0.05) of 11%, 17% and 28%, respectively. Within each gene, we selected disease causing variants so that 5% of the source population carry at least one risk allele. We simulated a binary phenotype in the source population assuming a relative risk of 4 for carriers of at least one risk allele without cumulative effect. We generated 500 replicates of samples of 30 cases/120 controls, 30 cases/180 controls and 60 cases/180 controls under the three stratification scenarios. Replicates were analyzed using the CAST-based approaches providing a non-inflated type I error rate in the simulation study under the null hypothesis, i.e. CAST with standard permutation (CAST-perm) in the absence of stratification and CAST-LocPerm-FE and CAST-LocPerm-SE with and without stratification. The power at a nominal level α of 0.01 was computed as the number of p-values equal or lower than 0.01 divided by the total number of replicates.

Results

The results of the simulation study under the null hypothesis (H0) for the three stratification scenarios and various sample sizes are shown in Table 1 (for α=0.01) and eTable 1 (for α=0.005). In the absence of PS, the asymptotic CAST approach had inflated type I errors for small samples while the small sample adjustment of the SKAT statistic provided correct type I error for most scenarios. However, adjusting CAST and SKAT on 10 PCs worsened the situation (e.g. CAST type I error=0.0116 vs. CAST-10PC type I error = 0.0146 and SKAT type I error = 0.00089 vs SKAT-10PC type I error = 0.0117, at α=0.01 for samples of 30 cases and 180 controls). Only SKAT-10PC in the largest sample size had a non-inflated type I error. By contrast, permutation-based p-value derivation (standard permutation, LocPerm-FE and locPerm-SE) provided type I errors close to the expected α threshold for both CAST and SKAT.

Table 1. Type I error rates of the different approaches and stratification scenarios at a nominal alpha level of 1%.

Values in bold are above the upper bound of the adjusted 95% adjusted prediction interval (PI), accounting for the number of scenarios (9 different sample sizes) investigated. The upper bounds of this interval is where Z0.025/9 replaces the usual 1.96, as previously suggested (Luo et al., 2018).

| Stratification | N cases | N controls | N genes* | Upper bound of the 95% PI | CAST-based approaches | SKAT-based approaches** | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAST | CAST-10PC | CAST-perm | LocPerm FE | LocPerm SE | SKAT | SKAT-10PC | SKAT-perm | LocPerm FE | |||||||

| Absence | 30 | 60 | 137058 | 1.07 | 1.14 | 1.86 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.97 | 1.06 | 1.11 | ||

| 30 | 120 | 186929 | 1.06 | 1.18 | 1.64 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.38 | 1.03 | 1.04 | |||

| 30 | 180 | 210398 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.46 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.00 | |||

| 60 | 60 | 167315 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.53 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.07 | 1.22 | 1.85 | 1.01 | 1.05 | |||

| 60 | 120 | 200367 | 1.06 | 1.10 | 1.39 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.29 | 0.95 | 0.99 | |||

| 60 | 180 | 217495 | 1.06 | 1.18 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.00 | |||

| 120 | 120 | 217712 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.44 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |||

| 120 | 180 | 227735 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 0.98 | |||

| 381 | 1142 | 265365 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | |||

| Intermediate | 30 | 60 | 136284 | 1.07 | 1.43 | 2.00 | 1.24 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 1.40 | 1.97 | 1.35 | 1.01 | ||

| 30 | 120 | 186950 | 1.06 | 1.60 | 1.76 | 1.34 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.34 | 1.37 | 1.43 | 0.99 | |||

| 30 | 180 | 210135 | 1.06 | 1.55 | 1.59 | 1.33 | 0.97 | 0.84 | 1.30 | 1.25 | 1.47 | 0.99 | |||

| 60 | 60 | 166480 | 1.07 | 1.45 | 1.54 | 1.35 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 2.12 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 1.02 | |||

| 60 | 120 | 200457 | 1.06 | 1.70 | 1.43 | 1.57 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.66 | 1.30 | 1.72 | 1.02 | |||

| 60 | 180 | 217626 | 1.06 | 1.90 | 1.38 | 1.62 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.66 | 1.17 | 1.79 | 1.05 | |||

| 120 | 120 | 217904 | 1.06 | 2.02 | 1.25 | 1.92 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 3.12 | 1.24 | 2.80 | 1.05 | |||

| 120 | 180 | 228258 | 1.06 | 2.22 | 1.23 | 2.11 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 2.98 | 1.21 | 2.93 | 1.09 | |||

| 381 | 1142 | 265365 | 1.05 | 2.07 | 1.09 | 2.03 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 2.77 | 1.02 | 2.96 | 1.06 | |||

| Extreme | 30 | 60 | 136075 | 1.07 | 1.62 | 2.47 | 1.40 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 1.63 | 2.56 | 1.57 | 1.00 | ||

| 30 | 120 | 186856 | 1.06 | 1.84 | 2.12 | 1.47 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.59 | 1.71 | 1.69 | 1.05 | |||

| 30 | 180 | 210260 | 1.06 | 1.74 | 1.91 | 1.49 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.55 | 1.45 | 1.74 | 1.02 | |||

| 60 | 60 | 166854 | 1.07 | 1.72 | 1.80 | 1.57 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 2.62 | 1.95 | 2.14 | 0.96 | |||

| 60 | 120 | 200466 | 1.06 | 2.00 | 1.58 | 1.84 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 2.14 | 1.65 | 2.19 | 1.00 | |||

| 60 | 180 | 217877 | 1.06 | 2.19 | 1.60 | 1.88 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 2.07 | 1.51 | 2.27 | 0.96 | |||

| 120 | 120 | 218206 | 1.06 | 2.38 | 1.33 | 2.27 | 0.81 | 0.61 | 4.18 | 1.42 | 3.77 | 0.91 | |||

| 120 | 180 | 228468 | 1.06 | 2.65 | 1.31 | 2.53 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 4.01 | 1.48 | 3.97 | 0.95 | |||

| 381 | 1142 | 265365 | 1.05 | 3.72 | 1.31 | 3.64 | 0.92 | 0.71 | 6.78 | 1.45 | 7.17 | 1.12 | |||

Number of protein coding genes tested, i.e. with at least 10 carriers of rare variants, over the 15 replicates

LocPerm-SE procedure was not implemented for the SKAT statistic because of its complex theoretical distribution

In the presence of PS, the strongest type I error inflation was observed for the approaches not accounting for PS, i.e. CAST, CAST-perm, SKAT and SKAT-perm. The level of inflation increased with the sample size and the degree of PS with a stronger effect on SKAT-based approaches than on CAST-based approaches. For samples composed of at least 120 cases and 120 controls, the level of inflation was stronger with SKAT-based than with CAST-based approaches not accounting for PS consistently with previous reports showing a more sensitive behavior of SKAT to population structure (Zawistowski et al., 2014). As an example, for the largest sample size of 381 cases and 1142 controls under the extreme PS scenario, the type I error at α=0.01 was 0.0372 for CAST, 0.0364 for CAST-perm, 0.0678 for SKAT and 0.0717 for SKAT-perm. Adjustment of CAST and SKAT on 10 PCs accounted partially for PS in the largest samples while it increased the type I error inflation in small samples. The main source of inflation for CAST-10PC and SKAT-10PC appeared to be the small sample size. The LocPerm-FE procedure provided type I errors close to the expected α threshold across all sample sizes and PS scenarios for both CAST and SKAT methods. CAST-LocPerm-SE performed well, despite being slightly conservative in the presence of extreme stratification.

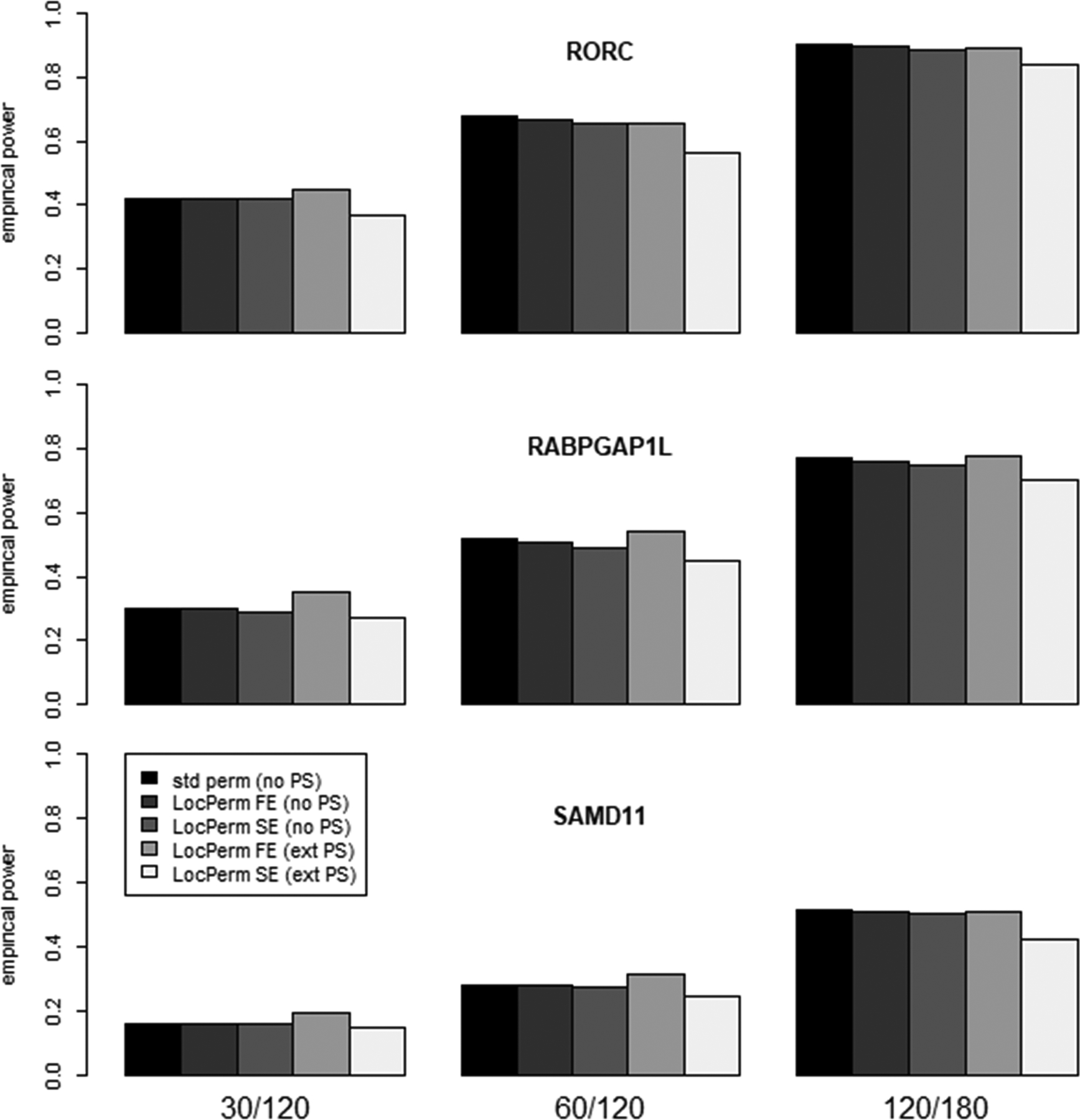

In the simulation study under the alternative hypothesis we focused on the CAST approaches. The results are shown in Figure 1 for methods providing a non-inflated type I error rate (i.e. CAST-perm in the absence of stratification and CAST-LocPerm-FE and CAST-LocPerm-SE with and without stratification). As expected, the power of the three approaches increased with the sample size and with the proportion of causal variants in the considered gene. Indeed, we observed powers for RORC > RABGAP1L > SAMD11 for which 5%/11%=45%, 5%/17%=29% and 5%/28%=18% of the individuals carrying a rare variant carried a causal variant, respectively. In the absence of stratification, standard permutation, LocPerm-FE and LocPerm-SE provided similar power within each gene (e.g. 42% for the three methods at α=0.01 for RORC in sample of size 30/120). In the presence of extreme stratification, the power of LocPerm-FE was well conserved, whereas that of LocPerm-SE decreased slightly, consistent with its conservative type I error rate in this scenario.

Figure 1:

Power at 1% significance level for two population stratification (PS) scenarios (no stratification [no PS] and extreme PS [ext PS]), three permutation procedures (standard permutation [std perm], LocPerm-FE and LocPerm-SE), three sample sizes (30/120, 60/120 and 120/180 cases/controls) and three different genes (RORC, RABPGAP1L and SAMD11).

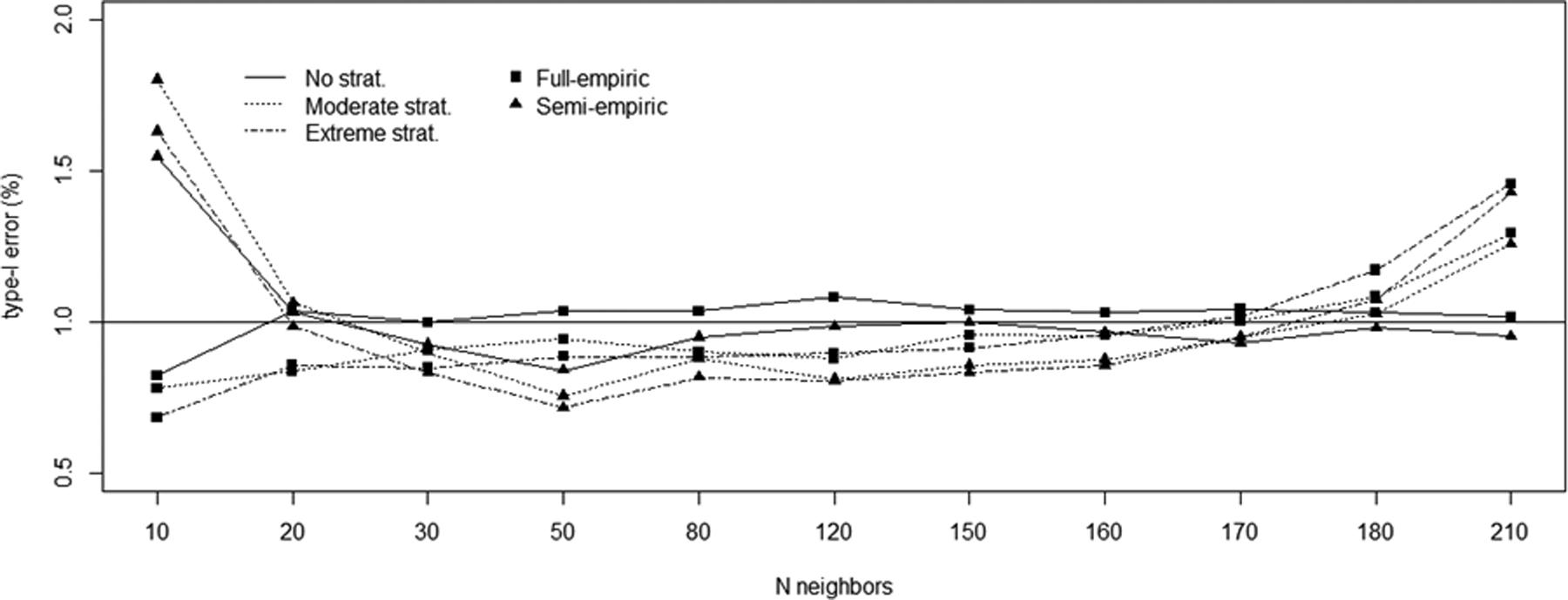

We further investigated the sensitivity of the LocPerm procedure to the number of neighbors under H0 (Figure 2). With an α threshold of 0.01, the type I error of the LocPerm procedure remained stable over a wide range of numbers of neighbors (from 20 to 170 for a total sample of 210 individuals), and the use of 30 neighbors appeared to be a reasonable choice. Finally, we evaluated the computation time of the LocPerm procedure on a unix-based virtual machine with a 64-bit CPU of 2.2Ghz and 32Go of RAM. For a given sample size, computation time was measured and averaged over 10 replicates. With the full empirical approach, computation time ranged from 10 minutes for the small sample composed of 30 cases and 60 controls to 1.5 hours for the largest sample including 381 cases and 1142 controls for an exome-wide analysis (eFigure2). It includes the generation of 5000 adapted permutations and the association testing for each gene and each permuted replicate. Using the semi-empirical approach requires to generate and test only 500 permuted replicates for each gene which yielded a 90% reduction in running time.

Figure 2:

Influence of the number of neighbors for the generation of local permutation (x axis) on type I error (y axis) for the scenario with 30 cases and 180 controls.

The situation with 210 neighbors corresponds to standard permutation.

Discussion

The inclusion of the first few PCs in the association model is a popular strategy for taking population structure into account. However, it is suitable only for methods implemented in a regression framework and requires large sample sizes. We found that, in small samples, inclusion of the first ten PCs in CAST or SKAT models failed to control the type I error in the presence of PS. The LocPerm procedure proposed here took PS into account effectively, both for CAST and SKAT approaches, with no significant power loss relative to other methods in the absence of PS. The SE approximation performed well in all scenarios, being only slightly conservative in the context of extreme PS, but with the advantage of reducing the computational cost by a factor 10 relative to the FE approach. We did not include adaptive permutations (Che, Jack, Motsinger-Reif, & Brown, 2014), in which the number of permutation samples decreases as the observed p-value increases, in our comparison. Because of the computational cost of the full empirical procedure for very low type I error levels, we limited our simulation study to type I error rate of 0.005 and caution is warranted in the generalization of our results to lower type I error rates. However, we would expect the SE approximation, which has lower computational cost, to reliably achieve lower levels of p-value, and to be faster than adaptive permutations because it requires only 500 permutation samples, whatever the observed p-value.

A permutation approach handling PS was proposed in a previous study (Epstein et al., 2012). The odds of disease conditional on covariates were estimated under a null model of no genetic association, and individual phenotypes were resampled, using these disease probabilities as individual weights, to obtain permuted data with a similar PS. However, subsequent studies showed that this procedure was less efficient than regular PC correction for dealing with fine-scale population structure (Persyn, Redon, Bellanger, & Dina, 2018). We show here that LocPerm, which uses the first 10 PCs weighted by their eigenvalues to compute a genetic distance matrix, handles complex and extreme PS more effectively than the standard PC-based correction approach, particularly in the context of small sample size. We did not investigate the situation of small number of cases with very large number of controls in which other specific methods, such as SAIGE-GENE (W. Zhou et al., 2020), could be more appropriate. We focused here on binary traits and the CAST and SKAT approaches, but it should be straightforward to extend the LocPerm procedure to quantitative traits and other rare variant association tests, particularly for adaptive burden tests requiring permutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank both branches of the Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases for helpful discussions and support.

Funding

The Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases was supported in part by grants from the French National Agency for Research (ANR) under the “Investissement d’avenir” program (grant number ANR-10-IAHU-01), the TBPATHGEN project (ANR-14-CE14-0007-01), the MYCOPARADOX project (ANR-16-CE12-0023-01), the Landscardio project (ANR-19-CE15-0010), the Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Excellence (grant number ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID), the St. Giles Foundation, the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; UL1TR001866), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (R01AI088364, R37AI095983, R01AI127564, P01AI061093), the Rockefeller University, and the University of Paris.

Footnotes

Data availability

A R script for the LocPerm procedure with a test example are available at https://github.com/jmullaert/LocPerm

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Clarke GM, Cardon LR, Morris AP, & Zondervan KT (2010). Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat Protoc, 5(9), 1564–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baye TM, He H, Ding L, Kurowski BG, Zhang X, & Martin LJ (2011). Population structure analysis using rare and common functional variants. BMC Proc, 5 Suppl 9, S8. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S9-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkadi A, Bolze A, Itan Y, Cobat A, Vincent QB, Antipenko A, … Abel L (2015). Whole-genome sequencing is more powerful than whole-exome sequencing for detecting exome variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(17), 5473–5478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418631112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigdeli TB, Neale BM, & Neale MC (2014). Statistical properties of single-marker tests for rare variants. Twin Res Hum Genet, 17(3), 143–150. doi: 10.1017/thg.2014.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che R, Jack JR, Motsinger-Reif AA, & Brown CC (2014). An adaptive permutation approach for genome-wide association study: evaluation and recommendations for use. BioData Min, 7, 9. doi: 10.1186/1756-0381-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Huffman JE, Brody JA, Wang C, Lee S, Li Z, … Lin X (2019). Efficient Variant Set Mixed Model Association Tests for Continuous and Binary Traits in Large-Scale Whole-Genome Sequencing Studies. Am J Hum Genet, 104(2), 260–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MP, Duncan R, Jiang Y, Conneely KN, Allen AS, & Satten GA (2012). A permutation procedure to correct for confounders in case-control studies, including tests of rare variation. Am J Hum Genet, 91(2), 215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good P (1994). Permutation Tests. In Springer Series in Statistics, A Practical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses (pp. X, 228). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-2346-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Good P (2002). Extensions Of The Concept Of Exchangeability And Their Applications. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 1(2), 243–247. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1036110240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Epstein MP, & Conneely KN (2013). Assessing the impact of population stratification on association studies of rare variation. Hum Hered, 76(1), 28–35. doi: 10.1159/000353270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HM, Sul JH, Service SK, Zaitlen NA, Kong SY, Freimer NB, … Eskin E (2010). Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet, 42(4), 348–354. doi: 10.1038/ng.548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, & Lin X (2014). Rare-variant association analysis: study designs and statistical tests. Am J Hum Genet, 95(1), 5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Nicolae DL, & Chen LS (2013). Marbled inflation from population structure in gene-based association studies with rare variants. Genet Epidemiol, 37(3), 286–292. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Maity A, Wu MC, Smith C, Duan Q, Li Y, & Tzeng JY (2018). On the substructure controls in rare variant analysis: Principal components or variance components? Genet Epidemiol, 42(3), 276–287. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, & Shi G (2020). On rare variants in principal component analysis of population stratification. BMC Genet, 21(1), 34. doi: 10.1186/s12863-020-0833-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manichaikul A, Mychaleckyj JC, Rich SS, Daly K, Sale M, & Chen WM (2010). Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics, 26(22), 2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson I, & McVean G (2012). Differential confounding of rare and common variants in spatially structured populations. Nat Genet, 44(3), 243–246. doi: 10.1038/ng.1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler S, & Thilly WG (2007). A strategy to discover genes that carry multi-allelic or mono-allelic risk for common diseases: a cohort allelic sums test (CAST). Mutat Res, 615(1–2), 28–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TD, Kiezun A, Bamshad M, Rich SS, Smith JD, Turner E, … Akey JM (2013). Fine-scale patterns of population stratification confound rare variant association tests. PLoS One, 8(7), e65834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, Price AL, & Reich D (2006). Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet, 2(12), e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persyn E, Redon R, Bellanger L, & Dina C (2018). The impact of a fine-scale population stratification on rare variant association test results. PLoS One, 13(12), e0207677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, & Reich D (2006). Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet, 38(8), 904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tintle N, Aschard H, Hu I, Nock N, Wang H, & Pugh E (2011). Inflated type I error rates when using aggregation methods to analyze rare variants in the 1000 Genomes Project exon sequencing data in unrelated individuals: summary results from Group 7 at Genetic Analysis Workshop 17. Genet Epidemiol, 35 Suppl 1, S56–60. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, & Lin X (2011). Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet, 89(1), 82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawistowski M, Reppell M, Wegmann D, St Jean PL, Ehm MG, Nelson MR, … Zollner S (2014). Analysis of rare variant population structure in Europeans explains differential stratification of gene-based tests. Eur J Hum Genet, 22(9), 1137–1144. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Guan W, & Pan W (2013). Adjustment for population stratification via principal components in association analysis of rare variants. Genet Epidemiol, 37(1), 99–109. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shen X, & Pan W (2013). Adjusting for population stratification in a fine scale with principal components and sequencing data. Genet Epidemiol, 37(8), 787–801. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Nielsen JB, Fritsche LG, Dey R, Gabrielsen ME, Wolford BN, … Lee S (2018). Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat Genet, 50(9), 1335–1341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Zhao Z, Nielsen JB, Fritsche LG, LeFaive J, Gagliano Taliun SA, … Lee S (2020). Scalable generalized linear mixed model for region-based association tests in large biobanks and cohorts. Nat Genet, 52(6), 634–639. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0621-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, & Stephens M (2012). Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet, 44(7), 821–824. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.