Abstract

Redox reactions are ubiquitous in organic synthesis and intrinsic to organic electrosynthesis. The language and concepts used to describe reactions in these domains are sufficiently different to create barriers that hinder broader adoption and understanding of electrochemical methods. To bridge these gaps, this Synopsis compares chemical and electrochemical redox reactions, including concepts of free energy, voltage, kinetic barriers, and overpotential. This discussion is intended to increase the accessibility of electrochemistry for organic chemists lacking formal training in this area.

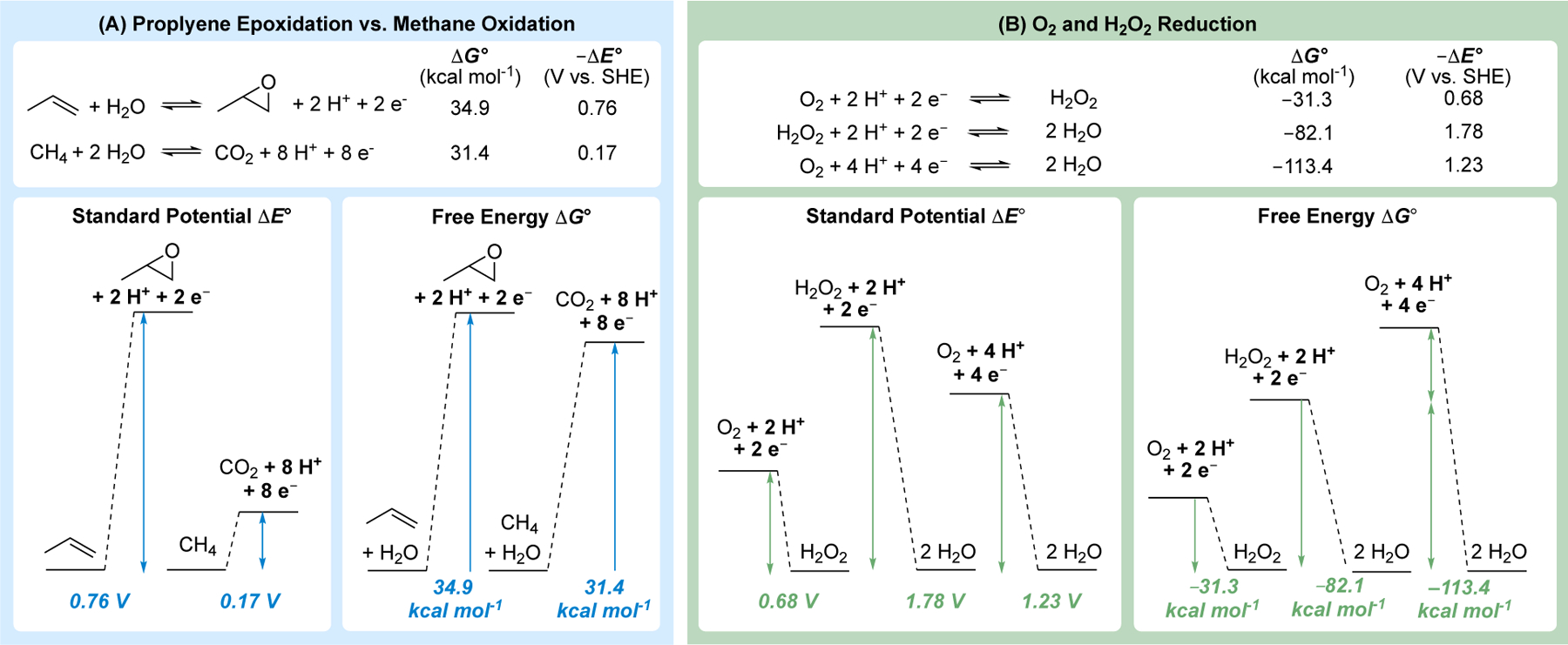

Graphical Abstract

Electrochemical synthesis has a long history within the field of organic chemistry,1–3 but it has seldom enjoyed mainstream attention. This situation appears to be changing in response to advances that facilitate broader adoption of electrosynthesis, including development of new synthetically useful electrosynthetic reactions, introduction of user-friendly instrumentation and apparatus, and publication of review articles4–8 and tutorials9–14 targeting an organic chemistry audience. Nevertheless, students and researchers with conventional training in organic chemistry still encounter unfamiliar language and terminology in the field of electrochemistry that can hinder assimilation of fundamental concepts. The present Synopsis seeks to lower this barrier by describing electrochemistry concepts using the language and terminology of organic chemistry.

“How should I think about voltage?”, “What is overpotential?”, and related questions are commonly encountered when organic chemists begin to engage with electrochemistry. Most organic chemists develop broad intuition for quantitative scales for organic molecules, such as pKa values, IR frequencies, and NMR chemical shifts, but several issues complicate development of an intuition for redox potentials:

Redox potentials are often very sensitive to the identity of the solvent, electrolyte, and/or reaction conditions (e.g., the presence of acid or base for proton-coupled redox reactions). This feature is similar is other properties of organic molecules (e.g., pKa), but it is often overlooked when comparing redox potentials from different literature sources.

Redox potentials in the literature commonly use different reference potentials, leading to variations in reported values, even when using the same solvent and conditions.

Electrochemical potentials measured experimentally (e.g., by cyclic voltammetry) typically correspond to potentials needed to initiate single-electron transfer (SET), but these values are very different from the thermodynamic potentials for net two-electron redox reactions of interest to organic chemists.

Organic chemists tend to be more familiar with the use of free energy and kcal mol−1 (or kJ mol−1) than with the use of redox potentials and voltage to assess reaction driving force and energetic trends. Free energies (ΔG°) and redox potentials (ΔE°) are readily interconverted via the expression in eq 1, (n = number of electrons; , 96,485 C·mol−1), but the simplicity of this

| (1) |

relationship belies a common source of confusion. The overall free energy of multistep redox reactions may be obtained from the sum of free energies of individual redox steps, while a similar relationship does not exist for redox potentials. These and related issues will be the focus of discussion below, with the goal of providing a framework for organic chemists to develop better intuition for the language and principles associated with electrochemical reactions.

1. Redox Potentials in Organic Chemistry: Electrochemistry and Single-Electron Transfer

Introductory chemistry courses present different perspectives on redox reactions. General and inorganic chemistry courses define oxidation and reduction reaction as the transfer of electrons between two atoms, ions, or molecules. This fundamental definition contrasts the presentation of redox reactions in organic chemistry courses where “reduction” is often defined in the context of hydrogenation reactions, which correspond to the net transfer of H2 (i.e., 2 e− and 2 H+). Similarly, many “oxidation” reactions correspond to dehydrogenation or dehydrogenative coupling reactions (Figure 1A). Prototypical organic reductions include conversion of esters to alcohols using hydride reagents, dissolving metal reductions of arenes to dienes, and catalytic hydrogenations of alkenes. These reactions illustrate the different means to deliver an equivalent of “H2” to an organic molecule: as a combination of hydrides and protons (H−/H+), as electrons and protons (2e−/2H+), or as H2 itself (via hydrogen atoms on a catalyst surface). Representative organic oxidations include dehydrogenation of saturated C–O bonds (alcohol oxidation) and C–C bonds or dehydrogenative coupling reactions, such as C–H oxidative coupling methods. Even atom-transfer oxidations, such as alkene epoxidation or sulfide oxidation (not shown), may be represented as dehydrogenative coupling of the alkene or sulfide with water. The unfavorable thermodynamics of such dehydrogenative couplings (elaborated below), however, accounts for the use of reactive atom-transfer reagents to achieve such reactions.

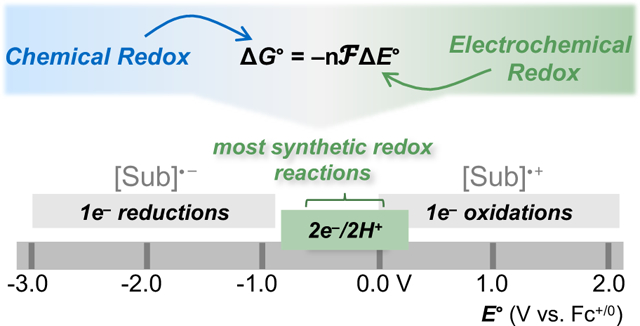

Figure 1.

Redox potentials measured for organic compounds at an electrode reflect electron-transfer thermodynamics and kinetics, not (de)hydrogenative reactions. (A) A large fraction of organic redox reactions involve transfer of hydrogen (2 e−/2 H+) to or from an organic molecule. (B) Redox potentials for most organic redox couples are irreversible and represent the potential required to generate a radical ion via single electron transfer. (C) Redox potentials for single electron transfer redox reactions of organic molecules measured at an electrode span over 5 V. Potential scale adapted from ref. 20 using Fc+/0 as the reference potential. (D) Conversion potentials for non-aqueous reference electrodes.15

The different presentation of redox reactions in general/inorganic and organic chemistry courses has a parallel in organic redox reactions, where the reactions commonly encountered when performing electrochemistry correspond to SET reactions, while the net redox reactions used in organic synthesis correspond to two-(or other even-)electron processes. SET in organic chemistry typically occurs as a fundamental step within a multi-step reaction sequence. These reactions have come to the forefront of contemporary organic chemistry as a result of research efforts on photochemistry and photoredox reactions16–18 and non-precious metal catalysis,19 in addition to electrochemistry. These activities have contributed to growing use of cyclic voltammetry (CV) and related techniques to measure redox potentials of organic molecules.20

Determination of redox potentials of organic molecules by CV is not always straightforward. Organic molecules seldom exhibit the canonical “duck-shaped” voltammograms associated with “reversible” electrochemical reactions.21,22 A rare exception is the one-electron TEMPO/TEMPO+ redox couple (TEMPO = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl) (Figure 1B-i), which exhibits good electrochemical behavior because of the unusual stability of the open-shell TEMPO radical.23 For a reversible couple of this type, the potential is designated as the midpoint between the forward and reverse peaks observed by CV. Most organic molecules lead to “irreversible” cyclic voltammograms (CVs; both cyclic voltammetry and cyclic voltammogram are abbreviated “CV”, with the meaning evident from the context). Such CVs exhibit an oxidation (or reduction) peak when the electrode is scanned to positive (or negative) potentials, but no peak is evident when the potential is cycled in the reverse direction. This behavior is evident for the piperidine carbamate in Figure 1B-ii. The current (or peak height) observed for the oxidation of the piperidine carbamate is approximately two-fold higher than that observed with TEMPO at the same concentration. This difference is rationalized by net transfer of two electrons from the piperidine carbamate at the redox potential needed to initiate SET.24 Specifically, the initial SET step is followed by rapid loss of a proton and a second electron, resulting in formation of an iminium ion. This product can react with a nucleophile, resulting in C–H functionalization adjacent to the nitrogen atom. This reactivity is the basis for the Shono oxidation, which is one of the most well-established methods in organic electrosynthesis.25 This behavior also rationalizes the irreversible CV behavior: when the potential is scanned in the reverse direction, the radical cation has already reacted via loss of a proton and second electron, and it is no longer available to undergo electrochemical reduction at the identical potential.

In spite of the added complexity, irreversible CVs may be used to approximate the one-electron redox potential of organic molecules. A collection of electrochemical potentials of common organic molecules, adapted from a recent compilation by Nicewicz and coworkers, is depicted in Figure 1C. Several caveats should be considered when evaluating the quantitative values of redox potentials for organic molecules determined by CV. Different researchers report values differently, with several variations. The potential reported for a particular CV peak may be associated with the value at peak current, at half of the peak current20 or at 85% of the peak current.26 These differences can lead to modest variations in the reported potentials (ca. 50–100 mV). Even larger differences in reported potentials (>100 mV) can arise from electrochemical kinetic effects resulting the use of different electrode materials, solvents, or electrolytes; or from the coupling of SET to chemical step(s).27–30 Finally, all redox potentials must be reported relative to a reference potential, akin to reference NMR chemical shifts. The literature has not converged on a unified reference in spite of IUPAC recommendations to use ferrocenium/ferrocene (Fc+/0) in non-aqueous solvent,31 and many researchers report redox potentials relative to an experimental reference electrode, such as Ag/Ag+ or an aqueous reference electrode, such as the saturated calomel electrode (SCE). These variations can lead to reported redox potential values that differ by nearly 400 mV. A table comparing the relative potentials of different reference electrodes is available in the literature, with common values summarized in Figure 1D.15 The potential values shown in Figure 1C, presented versus Fc+/0, are adapted from the original presentation, presented versus SCE. As a note of caution, any values of non-aqueous redox potentials reported versus the aqueous standard or normal hydrogen electrode as a reference (SHE and NHE, respectively) should be viewed with strong skepticism and avoided. To elaborate, the hydrogen electrode is based on the reversible redox reaction between H2 and 1 M [H+] (NHE) or at aH+ = 1 (SHE) at a Pt electrode in aqueous solution and is not straightforward to translate into a potential versus Fc+/0 potential in non-aqueous solvent. The H+/H2 electrode potential is very sensitive to reaction conditions due to the proton-coupled nature of the redox reaction, and redox potentials for organic molecules are typically measured in non-aqueous solvent. The lack of aqueous conditions, much less the lack of 1 M strong acid, means that potentials reported in organic solvents “versus NHE” (or “SHE”) are essentially uninterpretable.

In light of the indicated complexities, it would be helpful if future publications that report potentials for organic molecules, catalysts (chemical, electrochemical, photoredox, and others), and reagents in non-aqueous solvent would adhere to the IUPAC-recommended use of Fc+/0 as a reference potential and, ideally, would record a value in acetonitrile, since this is among the most common solvents for organic electrochemistry.32 Carbon-based electrodes, such as glassy carbon (GC), tend to minimize kinetic contributions to redox potentials.33 Thus, recommended conditions for CV measurements include the following: GC working electrode, Pt wire counter electrode, MeCN, 0.1 M TBAPF6 electrolyte, and a scan rate of 100 mV/s. A separate measurement of the Fc+/0 potential under the same conditions relative to the reference electrode (e.g., Ag/Ag+, SCE) will allow reporting of potentials “vs. Fc+/0”.

2. Redox Potentials in Organic Chemistry: Synthetic Two-Electron Redox Reactions.

Redox potentials associated with synthetic redox reactions, such as the hydrogenation/dehydrogenation reactions in Figure 1A, are rarely accessible by CV and are seldom considered in organic chemistry.35 The importance of such potentials is well recognized in the field of energy conversion,36–39 where energy efficiency and overpotentials of electrochemical reactions are crucial figures of merit, and we have discussed elsewhere why such values are also important for organic electrosynthesis.40 Thermodynamic potentials may be obtained from standard enthalpy and entropy data, such as those compiled by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST),41 followed by conversion of the corresponding free energies (ΔG°) and then standard potentials (ΔE°) using eq 1 (Figure 2A).42–45 The source data typically corresponds to pure compounds and, therefore, doesn’t account for energy of solvation, but the resulting analysis still provides useful approximations for chemical reactions of interest.

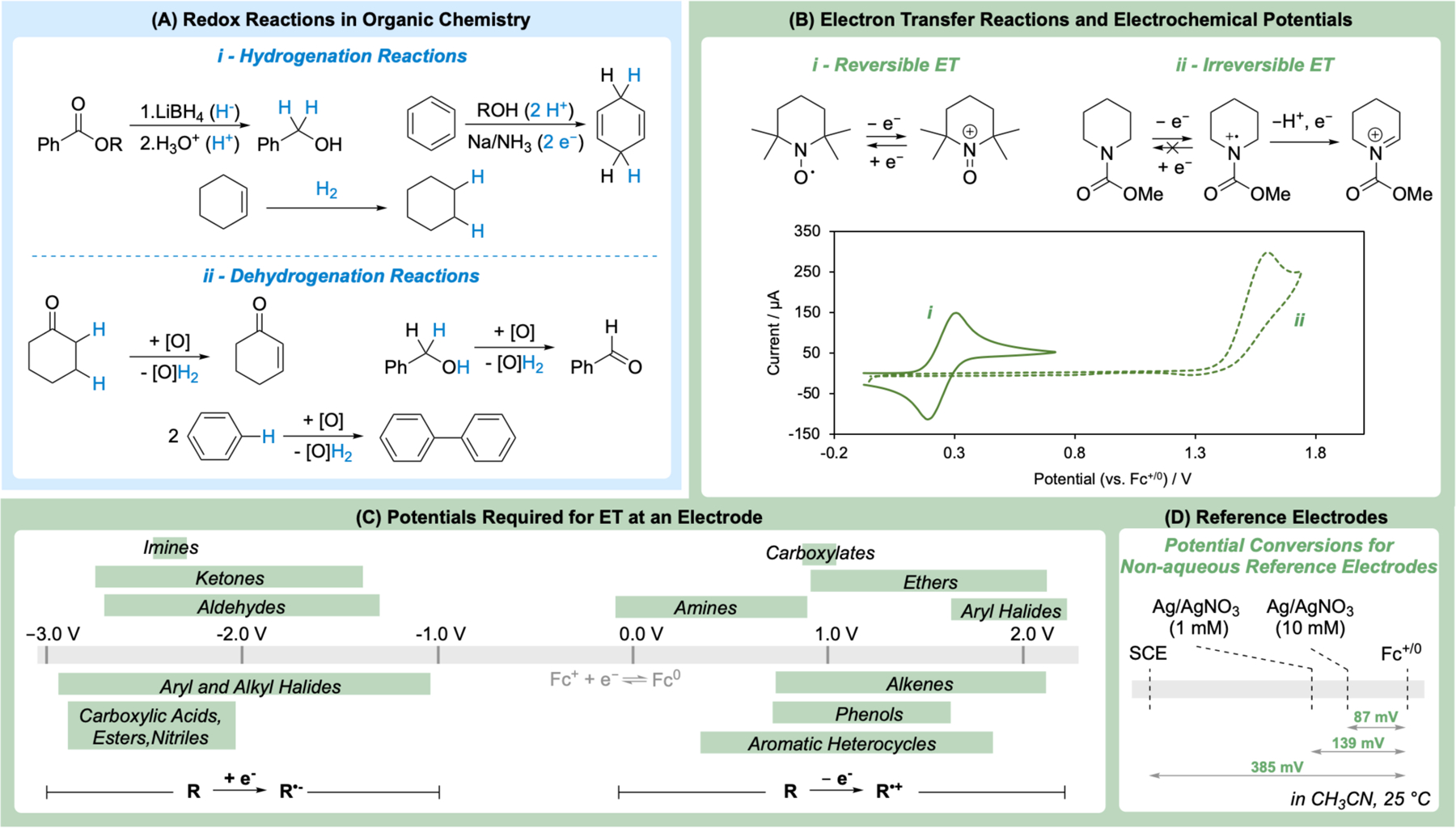

Figure 2.

Standard potentials for organic redox reactions can be derived from the free energy of the reaction. (A) Representative standard potential calculation for the benzyl alcohol/benzaldehyde redox couple (+0.14 V vs SHE). (B) Tabulated standard potentials for selected oxidation reactions of interest to organic chemists and potentials for synthetically relevant oxidants. See the Supporting Information for derivation of these values. (C) Standard potentials for oxidants of interest to organic chemists. (D) Potential scale comparing the potentials for select organic oxidation reactions and oxidants. aPotential vs NHE. TBHP = tert-Butyl hydroperoxide; TEMPO+ = 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-oxopiperidinium; TEMPOH2+ = 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-hydroxyl piperidinium; DDQ = 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone; DDH2Q = 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-hydroquinone; BQ = 1,4-benzoquionone; H2Q = 1,4-hydroquinone.

ΔE° values for a collection of oxidation reactions of interest to organic chemists are compiled in Figure 2B, with the NIST thermodynamic data and calculations used to obtain the ΔE° values provided in the Supporting Information. Use of SHE as the reference potential reflects the standard-state conditions used for the calculations and the proton-coupled nature of these reactions (including SHE), which contrasts the SET redox reactions discussed in the previous section.

The oxidation reactions in Figure 2B correspond to dehydrogenations that feature loss of 2 e− and 2 H+ (= H2). The potential values in nearly all cases reflect reactions that are unfavorable with respect to loss of H2. It is worth noting that voltage corresponds to “electromotive force”, highlighting that it is perhaps more appropriate to refer to potentials, rather than free energies, when defining a “driving force” of a reaction (vide infra). This outcome is not surprising because most oxidation/dehydrogenation reactions in organic chemistry, such as those shown in Figure 2B, use an oxidant to promote the removal of H2.46 Redox potentials derived for synthetically useful chemical oxidants, compiled in Figure 2C and plotted in Figure 2D with the organic reaction potentials, show that oxidants often provide a large driving force (i.e., “overpotential”, vide infra) to promote the reactions. The standard potentials for organic oxidation reactions are clustered within a relatively small region between approximately 0 – 0.4 V vs SHE. This narrow distribution contrasts the > 2 V range of redox potentials for one-electron oxidation of organic molecules, shown in Figure 1C. To the extent that the same potentials apply to synthetic reduction reactions (e.g., carbonyl reduction to alcohols, alkene hydrogenation), the values in Figure 2B and 2D may be contrasted to the entire > 5 V range of one-electron redox reactions depicted in Figure 1C.

The dramatic difference between the potential ranges for reactions in Figures 1C and 2B/D arises from the different nature of the reactions involved. SET oxidations of an organic molecule generate high-energy radical cation species that will be very sensitive the stabilizing/destabilizing effect of substituents and/or electronic effects. In contrast, the dehydrogenation reactions are charge balanced and form neutral, closed-shell products that will be much less sensitive to substituents and/or electronic effects. The absolute values of the 1 e− and 2 e−/2 H+ redox potentials are difficult to compare directly as discussed in the previous section, but most 2 e−/2 H+ organic redox reactions have thermodynamic potentials that fall within a narrow window between the 1 e− reduction and 1 e− oxidation potentials for organic molecules.47,48

A Note on Sign Convention.

A common source of confusion arises from redox potential sign conventions in electrochemistry, as there are two historical approaches.49,50 The first maintains the relationship between ΔG° and ΔE° according to eq 1, and the sign of the potential changes when a reduction reaction is written as an oxidation (as for the oxidation reactions in Figure 2B). Doing so ensures that the sign of ΔG° is correct for an oxidation reaction balanced by proton reduction to afford H2 (i.e., with SHE = 0.0 V as the reference potential). The other approach recognizes that both oxidation and reduction take place at the same electrode potential, irrespective of the direction of the redox reaction, and therefore the potential sign does not change when the reaction direction is changed. Both approaches have merit, but the latter is often more appropriate and less confusing in practical applications of organic electrochemistry. Accordingly, the sign of the potential is identical, whether the reaction is assigned a “reduction potential”, “oxidation potential”, or “redox potential.”

3. Comparison of Redox Potentials and Free Energies

The reactions compiled in Figure 2B are only representative examples, but they show that virtually any redox reaction in organic chemistry may be represented as an electrochemical half-reaction that may be assigned a standard potential (ΔE°). Atom-transfer oxidation reactions, such as epoxidation, typically use strong oxygen-atom donors in synthetic applications, but the thermodynamics for these reactions may be analyzed by considering the “dehydrogenative” coupling reactions with water (see reactions f–j, l–o, and q in Figure 2B). The high standard potential for “dehydrogenative” coupling of propene and water to afford the propylene oxide (ΔE° = 0.76 V, Figure 2B–j), rationalizes the need for a reactive oxidant, such as tBuOOH (ΔE° = 1.7 V, Figure 2C–3). Propene epoxidation may be compared to the oxidation of methane to carbon dioxide (Fig. 3A). The latter reaction is typically considered a facile reaction, owing to the combustion of natural gas for energy production; however, combustion uses O2 as an oxidant to make the reaction favorable. As an electrochemical half-reaction, “dehydrogenative” coupling of methane and two water molecules is unfavorable (i.e., when forming H2 as the product, rather than H2O from combustion), albeit with a substantially lower standard potential than alkene epoxidation (ΔE° = 0.17 V, Figure 2B-n).

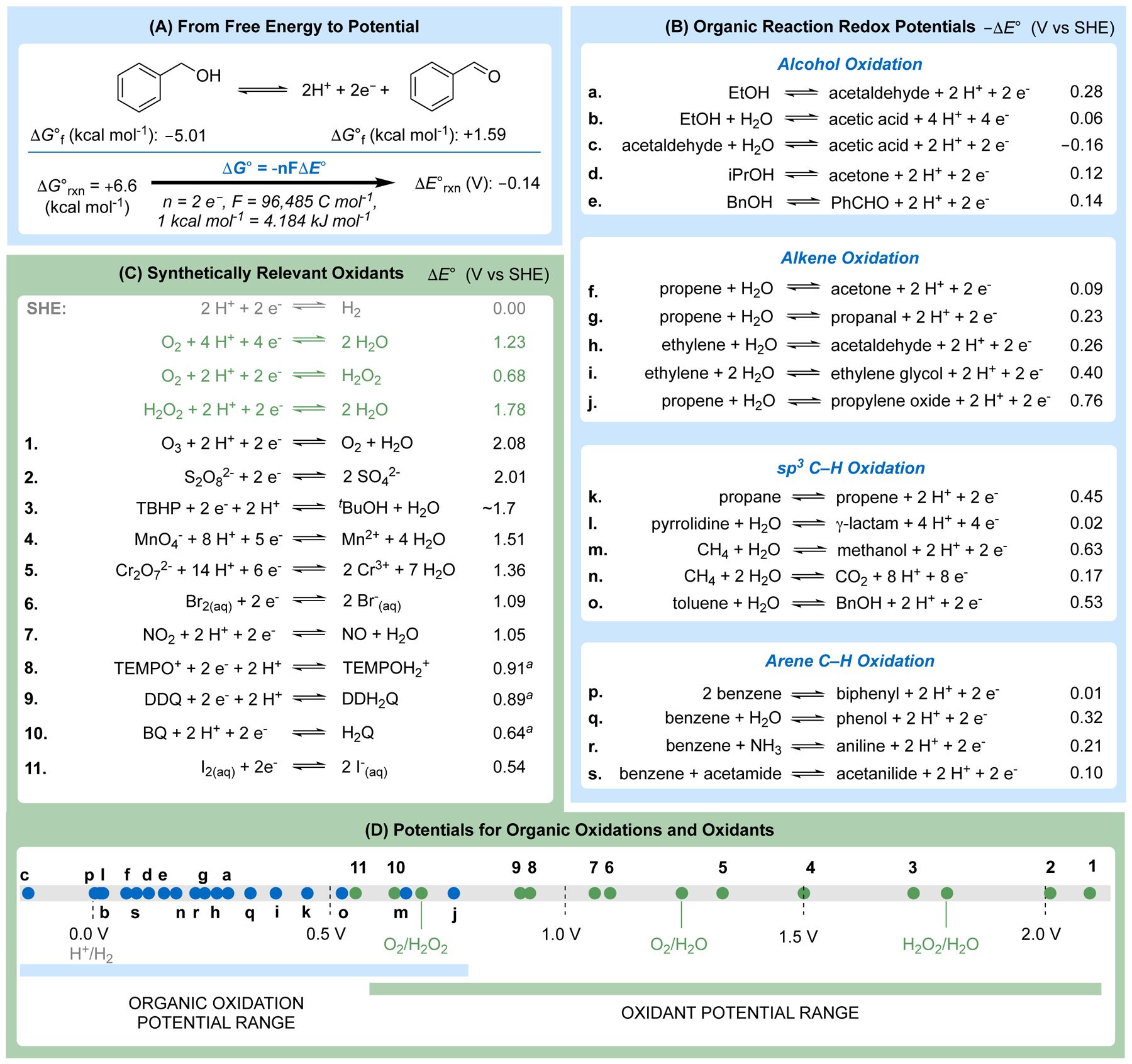

Figure 3.

Potential and free energy diagrams for redox reactions involving different numbers of electrons, including 2e−/2H+ alkene epoxidation vs 8e−/8H+ methane oxidation (A) and stepwise 2e−/2H+ vs net 4e−/4H+ reduction of O2 (B). The diagrams in (B) show that free energy values are additive while potentials are not.

The nearly 600 mV difference in standard potentials for propene and methane oxidation is obscured when the free energies for these reactions are evaluated, as the ΔG°rxn values are very similar: 34.9 kcal mol−1 and 31.4 kcal mol−1, respectively, for oxidation of propene to propylene oxide and methane to carbon dioxide. This apparent discrepancy arises from the different number of electrons involved in the two reactions (2 e− versus 8 e−), as is evident from the relationship between ΔE° and ΔG° in eq 1. The four-fold increase in the number of electrons involved in methane oxidation makes this “easy” reaction nearly as unfavorable as propene oxidation from the perspective of free energy. Organic chemists commonly assess reaction driving force from the perspective of free energy. Therefore, the transition to considering redox potentials can lead to confusion if the electron stoichiometry is ignored.

The relationship between redox potentials and free energies is further illustrated by redox reactions involving O2. Hydrogen peroxide is obtained from the 2e−/2H+ reduction of O2, and yet H2O2 is a stronger oxidant than O2: ΔE°(H2O2/H2O) = 1.78 V, ΔE°(O2/H2O2) = 0.68 V and ΔE°(O2/H2O) = 1.23 V (Figure 3B). These values can represent a source of confusion, for example, expressed as “How can a four-electron oxidant be a weaker oxidant than a two-electron oxidant?” Once again the confusion is (partly) resolved by recognizing the importance of redox stoichiometry. From a free energy perspective, 4e−/4H+ reduction of O2 to water exhibits a ΔG°rxn of −113.4 kcal/mol, while the 2e−/2H+ reduction of H2O2 to water exhibits a ΔG°rxn of −82.1 kcal/mol. The potential and energy diagrams in Figure 3B show that ΔG° values are additive in sequential redox processes, while the potential values do not follow systematic trends. Rather, the potential for 4e−/4H+ reduction of O2 to water (1.23 V) is the average potential for the four electrons [(0.68 V*2) + (1.78*2))/4 = 1.23 V].

Notes on Units.

Volt is an SI unit that corresponds to the energy per unit of charge, or joules per coulomb (J/C). Meanwhile, an “electron volt” is an energy term that is defined as the energy in joules gained by an electron when the potential of the electron increases by one volt (1 eV = 1.602 × 10−19 J). An electron has a charge of 1.602 × 10−19 C. Conversion of this charge to a molar quantity yields a value of 96485 C mol−1, which is the Faraday constant noted in eq 1. Further manipulation of units provides that basis for common benchmarks for the energy involved in a 1 e− transfer reaction: SET reactions with a ΔE of 1 V corresponds to 96.5 kJ/mol or 23.06 kcal/mol of driving force.

4. Reaction Equilibria, Driving Force, and Overpotential

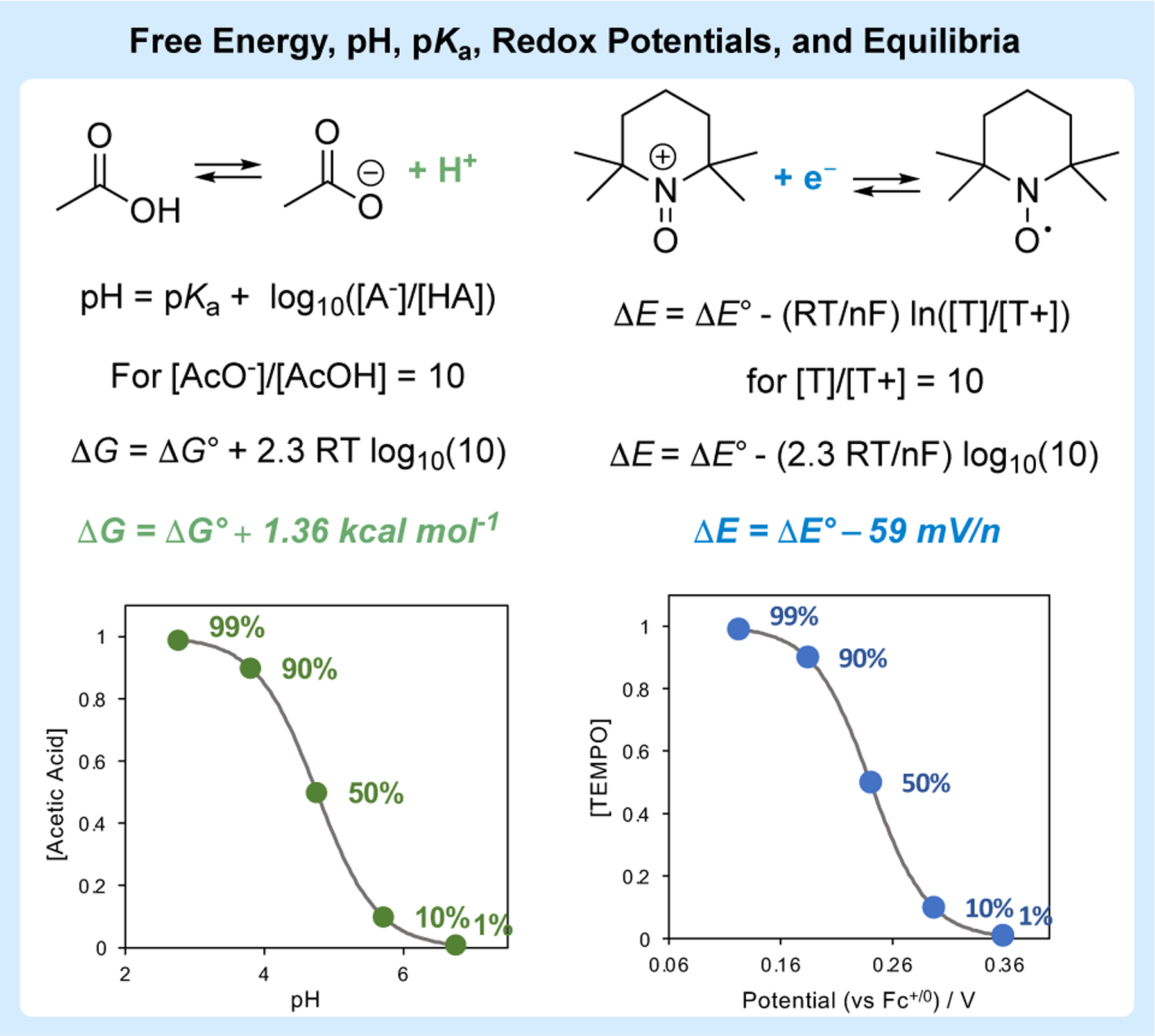

The relationships among free energy, redox potentials, and equilibrium constants are taught in introductory chemistry courses and are summarized in eqs 1–5. Many organic chemists memorize the benchmark value in eq 3 that correlates a 10-fold difference in the reaction quotient, Q (i.e., ratio of product and starting material) with a 1.36 kcal/mol difference in the reaction free energy. (The same value of 1.36 kcal/mol correlates ΔG‡ and a 10-fold difference in rate constants.) The Nernst equation in eq 5 shows that a similar relationship exists for redox potentials, whereby a 10-fold difference in Q correlates with a 59 mV/n difference in redox potential. The relationships among free energy, redox potentials, and equilibrium constants are clearly evident in the pH titration curve for a Brønsted acid, governed by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (eq 6), and in the potential dependence of a redox equilibrium, such as TEMPO/TEMPO+ (Figure 4).51

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Figure 4.

Similarities between the dependence of free energy and redox potential on chemical equilibria, highlighting the benchmark values of 1.36 kcal mol−1 and 59 mV/n associated with the change in free energy and redox potential for a ten-fold change in the reaction quotient, with plots highlighting similarities between pH titrations of a weak acid and potential-dependent speciation of a redox couple.

Nernst Equation:

| (5) |

Henderson–Hasselbalch Equation

| (6) |

These thermodynamic relationships may be considered further to probe the relationship between chemical and electrochemical redox reactions. The equilibrium potential for a redox reaction defines the potential at which an ergoneutral equilibrium exists between the oxidized and reduced states of a redox couple (ΔG = 0; under standard state conditions, this potential corresponds to the standard potential, E°). To drive an electrochemical reaction to completion (i.e., >99% conversion), one simply needs to apply an “overpotential” at the electrode suitable to adjust the equilibrium state. For a 2e− reaction, a potential of 59 mV would be required to achieve a [product]:[starting material] ratio of 100:1 (cf. Figure 4 and eq 5, with n = 2 and Q = 100).

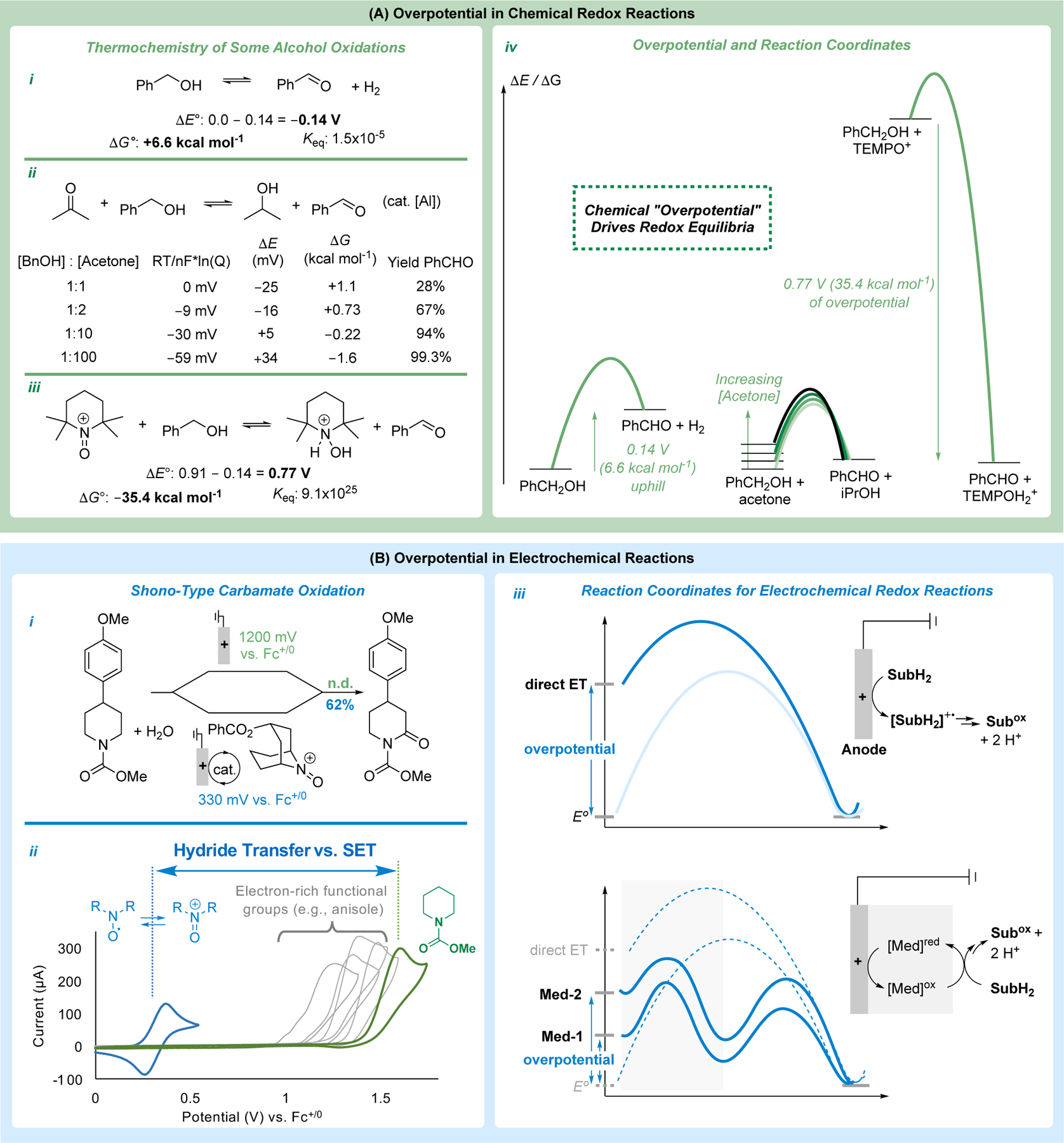

Similar concepts are applied in chemical redox reactions. In order to promote oxidation of an organic molecule, an oxidant is used that has a reduction potential suitable to promote the desired substrate oxidation. This concept is explored in Figure 5A, using alcohol oxidation as an example. The oxidation of benzyl alcohol has a standard potential of 0.14 V vs SHE, which corresponds to a ΔG° of +6.6 kcal mol−1 for release of H2. Oppenauer alcohol oxidation methods employ a catalytic Lewis acid with a ketone, such as acetone, to promote equilibrium hydrogen transfer.52 The standard potential for acetone/iPrOH is actually lower than for benzyl alcohol (ΔE° = 0.12 V). Therefore, if only 1 equiv of acetone is used, the reaction will be unfavorable by 1.1 kcal mol−1, and the yield of benzaldehyde will maximize at 28%. By using ≥ 100 equiv of acetone, however, one can achieve >99% conversion of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde (Figure 5A-ii and iv). The near-ergoneutrality of Oppenauer oxidations often complicates these reactions. Many alcohols are more difficult to oxidize than benzyl alcohol, and it is preferable to uses a stronger oxidant. Oxoammonium species, such as TEMPO+ (TEMPO = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl), are commonly used oxidants for these reactions53 owing to their high 2e−/2H+ reduction potential (0.91 V), which supplies a 0.77 V driving force or “overpotential” for the oxidation of benzyl alcohol (Figure 5A-iii and vi). This analysis shows how electrochemical terminology and principles may be used to analyze chemical redox reactions.

Figure 5.

Analysis of overpotential in organic (electro)synthesis. (A) Overpotential for alcohol oxidation reactions. (B) Overpotential in an electrochemical Shono-type oxidation reaction and the role of mediators in lowering the overpotential.

In electrochemical synthesis, the “overpotential” corresponds to the difference between the applied potential at the working electrode and equilibrium potential of the net redox reaction.40 Because one-electron oxidation (or reduction) of organic molecules to generate radical cations (or anions) inevitably requires an applied potential much higher (or lower) than the thermodynamic potential of the net reaction (see sections 1 and 2 above), direct electrolysis reactions inevitably exhibit large overpotentials. This high applied potential often limits the functional-group compatibility and the utility of electrochemical synthesis.

Mediated electrochemistry offers a strategy to bypass these high overpotentials because the mediators often promote mechanisms that bypass high-energy radical-ion intermediates.40,54 This topic was elaborated more extensively in a recent Account on this topic,40 but the principles are illustrated in Figure 5B. Shono oxidation of a piperidine carbamate bearing an electron-rich aromatic ring affords no desired product because the arene undergoes SET oxidation at potentials lower than that of the carbamate functional group (Figure 5B-i and ii). On the other hand, an oxoammonium-based mediator promotes hydride transfer from the substrate, rather than SET. This mechanism accesses the same iminium ion generated via stepwise ET-PT-ET, while allowing the reaction to proceed at an electrode potential over 1.7 V lower than the potential needed to initiate SET in the conventional Shono oxidation.55 The lower overpotential associated with the mediated process greatly enhances the functional group compatibility and scope of the electrosynthetic reaction. The development of new mediators and homogeneous electrocatalysts that lower the overpotential for electrosynthetic reactions is among the most promising opportunities for the field of organic electrochemistry.

A note on sources of overpotential.

Additional sources of overpotential merit brief discussion. Slow electron-transfer kinetics between an analyte and electrode can lead to increased separation between the anodic and catalytic peak potentials recorded by CV.56 The electrode material can influence the (over)potential required to drive redox events57–59 because the chemical surface of an electrode can alter the mechanism by which electron transfer proceeds. Intimate, stabilizing interactions between an analyte and the electrode surface can reduce the overpotential required to achieve electron transfer, whereas the potential required to achieve the same electron transfer step through an outer-sphere pathway is invariably greater. These effects are especially evident in the field of heterogeneous electrocatalysis. For example, the electrochemical reduction of H+ to H2 proceeds at a low overpotential on a catalytic Pt electrode. This feature is ideal for electrochemical oxidations coupled to H+ reduction to H2. On the other hand, electrode materials that exhibit a high overpotential for H+ reduction to H2, such as Cd and Pb,59 are used for electrochemical reductions of organic molecules in order to avoid H+ reduction to H2.

Conclusion

This Synopsis has surveyed a number of topics and concepts that bridge the fields of organic synthesis and electrochemistry. Redox reactions are ubiquitous in both domains. Developing an ability to navigate the different, but complementary, terminology used to describe redox thermodynamics and processes in these fields should enhance the accessibility of electrochemistry to organic chemists. The growing adoption of electrochemical methodology, together with intuitive assimilation of electrochemical concepts and terminology, by organic chemists will greatly expand the accessibility and practice of electrochemical methods for organic synthesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Profs. Samuel H. Gellman and Clark R. Landis for their stimulating discussions of electrochemical potentials, sign conventions, and other topics that inspired and influenced content herein. We also thank Prof. Mohammad Rafiee, Prof. Fei Wang, Dr. Asmual Hoque, and Shannon L. Goes for fruitful discussions about the practice and theory of organic electrochemistry. The content of this article was influenced by several different research projects in our group, sponsored by different funding agencies and programs: the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award #DE-FG02-05ER15690 (J.E.N.; e.g., ref. 39) has sponsored research involving the use of non-precious-metal catalysts for aerobic oxidation, including those that operate with different overpotentials associated coupled redox-half reactions; the National Science Foundation, under award CHE-1953926 (D.L.B. and A.G.S.; e.g., ref. 45), has sponsored research probing the overpotential of homogeneous Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions; the Center for Molecular Electrocatalysis, an Energy Frontier Research Center, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, has sponsored research contributing to our understanding of overpotential in the context of energy-conversion reactions, including mediated electrochemistry (J.B.G.; e.g., refs. 28, 35); and the NIH NIGMS, under award R35 GM134929, which has funded our work on electrochemical organic synthesis (S.S.S; e.g., ref. 40).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.1c01520.

Derivation of ΔG° and ΔE° for the values in Figure 2 and worked examples (PDF)

Tabulated thermochemical values for Figure 2 (XLSX)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Weinberg NL; Weinberg HR Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Compounds. Chem. Rev 1968, 68, 449–523. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammerich O; Speiser B, Eds. Organic Electrochemistry Revised and Expanded. CRC Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan M; Kawamata Y; Baran PS Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 13230–13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horn EJ; Rosen BR; Baran PS Synthetic Organic Electrochemistry: An Enabling and Innately Sustainable Method. ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 302–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebe A; Gieshoff T; Möhle S; Rodrigo E; Zirbes M; Waldvogel SR Electrifying Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 5594–5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costenin C; Savéant J-M Concepts and Tools for Mechanism and Selectivity Analysis in Synthetic Organic Electrochemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2019, 116, 11147–11152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noël T; Cao Y; Laudadio G The Fundamentals Behind the Use of Flow Reactors in Electrochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 2858–2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novaes LFT; Liu J; Shen Y; Lu L; Meinhardt JM; Lin S Electrocatalysis as an Enabling Technology for Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2021, 50, 7941–8002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schotten C; Nicholls TP; Bourne RA; Kapur N; Nguyen BN; Willans CE Making Electrochemistry Easily Accessible to the Synthetic Chemist. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 3358–3375. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingston C; Palkowitz MD; Takahira Y; Vantourout JC; Peters BK; Kawamata Y; Baran PS A Survival Guide for the “Electro-curious”. Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53, 72–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organic Electrochemistry Virtual Short Course, https://stahl.chem.wisc.edu/organic-electrochemistry-virtual-course/ (accessed Apr. 8, 2021).

- 12.Little RD A Perspective on Organic Electrochemistry. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 13375–13390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beil SB; Pollok D; Waldvogel SR Reproducibility in Electroorganic Synthesis – Myths and Misunderstandings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 27, 14750–14759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilt G Basic Strategies and Types of Applications in Organic Electrochemistry. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pvalishchuk VV; Addison AW Conversion Constants for Redox Potentials Measured versus Different Reference Electrodes in Acetonitrile Solutions at 25 °C. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2000, 298, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narayanam JMR; Stephenson CRJ Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis: Application in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011. 40, 102–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prier CK; Rankic DA; MacMillan DWC Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skubi KL; Blum TR; Yoon TP Dual Catalysis Strategies in Photochemical Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10035–10074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bullock RM, Ed. Catalysis without Precious Metals. Wiley: Weinheim, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth HG; Romero NA; Nicewicz DA Experimental and Calculated Electrochemical Potentials of Common Organic Molecules for Applications to Single-Electron Redox Chemistry. Synlett 2016, 27, 714–723. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elgrishi N; Rountree KJ; McCarthy BD; Rountree ES; Eisenhart TT; Dempsey JL A Practical Beginner’s Guide to Cyclic Voltammetry. J. Chem. Educ 2018, 2, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 22. See Ref. 21 for more information on conventions used to present CV data. In this article, we use the IUPAC convention for axis orientation (i.e., positive potentials and currents are displayed toward the right and top of the plots, respectively).

- 23.Nutting JE; Rafiee M; Stahl SS Tetramethylpiperidine-N-Oxyl (TEMPO), Phthalimide N-Oxyl (PINO), and Related N-Oxyl Species: Electrochemical Properties and Their Use in Electrocatalytic Reactions. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 4834–4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.A detailed description of the kinetic factors that contribute to the amplitude and shape of CV features are beyond the scope of this text. However, CV peak amplitude depends on several factors, including the rate of electron transfer and the diffusion coefficient of the analyte. For example, the peak current amplitude of a diffusive, redox active species that undergoes fast electron transfer at an electrode is described by the Randles–Ševčik equation: where D is the diffusion coefficient and C is the concentration of the analyte; υ is the scan rate; n, , R, and T defined previously.

- 25.Shono T; Hamaguchi H; Matsumura Y Electroorganic Chemistry. XX. Anodic Oxidation of Carbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1975, 97, 4264–4268. [Google Scholar]

- 26.A more formal treatment would use the potential measured at 85% of the peak current:; Nicholson RS; Shain I Theory of Stationary Electrode Polarography. Anal. Chem 1964, 36, 706–723. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merkel PB; Luo P; Dinnocenzo JP; Farid S Accurate Oxidation Potentials of Benzene and Biphenyl Derivatives via Electron-Transfer Equilibria and Transient Kinetics. J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 5163–5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.For example, consider the cyclic voltammogram of TEMPO and TEMPOH at a glassy carbon and an oxidized glassy carbon electrode:; Gerken JB; Pang YQ; Lauber MB; Stahl SS Structural Effects on the pH-Dependent Redox Properties of Organic Nitroxyls: Pourbaix Diagrams for TEMPO, ABNO, and Three TEMPO Analogs. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 7323–7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wayner DDM; Parker VD Bond Energies in Solution from Electrode Potentials and Thermochemical Cycles. A Simplified and General Approach. Acc. Chem. Res 1993, 26, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren JJ; Tronic TA; Mayer JM Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and Its Implications. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 6967–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gritzner G; Küta J Recommendations on Reporting Electrode Potentials in Nonaqueous Solvents. Pure & Appl. Chem 1984, 56, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connelly NG; Geiger WE Chemical Redox Reagents for Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 877–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zittel E; Miller FJ A Glassy Carbon Electrode for Voltammetry. Anal. Chem 1965, 37, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Linden WE; Dieker JW Glassy Carbon as Electrode Material in Electroanalytical Chemistry. Anal. Chim. Acta 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 35.The quinone/hydroquinone redox coupling is a rare example of a coupled 2 e−/2 H+ redox reactions that can show (quasi)reversible redox behavior. See, for example:; Huynh MT; Anson CW; Cavell AC; Stahl SS; Hammes-Schiffer S Quinone 1 e− and 2 e−/2 H+ Reduction Potentials: Identification and Analysis of Deviations from Systematic Scaling Relationships. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 15903–15910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts JAS; Bullock RM Direct Determination of Equilibrium Potentials for Hydrogen Oxidation/Production by Open Circuit Potential Measurements in Acetonitrile. Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 3823–3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pegis ML; Roberts JAS; Wasylenko DJ; Mader EA; Appel AM; Mayer JM Standard Reduction Potentials for Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Couples in Acetonitrile and N,N-Dimethylformamide. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 11883–11888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindley BM; Appel AM; Krogh-Jespersen K; Mayer JM; Miller AJM Evaluating the Thermodynamics of Electrocatalytic N2 Reduction in Acetonitrile. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 698–704. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang F; Gerken JB; Bates DM; Kim YJ; Stahl SS Electrochemical Strategy for Hydrazine Synthesis: Development and Overpotential Analysis of Methods for Oxidative N–N Coupling of an Ammonia Surrogate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 12349–12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang F; Stahl SS Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Molecules at Lower Overpotential: Accessing Broader Functional Group Compatibility with Electron-Proton Transfer Mediators. Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53, 561–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, Linstrom PJ and Mallard WG, Eds.; National Institutes of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg MD, 20899, https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ (accessed June 22, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 42. For other approaches to estimating thermodynamic potentials using equilibrium constants, open-circuit potential measurements, and/or thermodynamic cycles, see refs. 43–45.

- 43.Adkins H; Elofson RM; Rossow AG; Robinson CC The Oxidation Potential of Aldehydes and Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1949, 71, 3622–3629. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wise CF; Agarwal RG; Mayer JM Determining Proton-Coupled Standard Potentials and X–H Bond Dissociation Free Energies in Nonaqueous Solvents Using Open-Circuit Potential Measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 10681–10691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruns DL; Musaev DG; Stahl SS Can Donor Ligands Make Pd(OAc)2 a Stronger Oxidant? Access to Elusive Palladium(II) Reduction Potentials and Effects of Ancillary Ligands via Palladium(II)/Hydroquinone Redox Equilibria. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 19678–19688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Acceptorless dehydrogenation reactions are an exception. However, these reactions are performed far from standard state conditions. See:; Gunanathan C; Milstein D Applications of Acceptorless Dehydrogenation and Related Transformations in Chemical Synthesis. Science 2013, 341, 1229712–1–1229712–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Comparison is complicated by several factors, not least of which is the ill-defined potential for Fc+/0 in aqueous solution, which ranges from ~ 34 to 400 mV vs NHE in the literature. See refs. 36 and 42.

- 48.Noviandri I; Brown KN; Fleming DS; Gulyas PT; Lay PA; Masters AF; Philips L Decamethylferrocenium/Decamethylferrocene Redox Couple: A Superior Redox Standard to the Ferrocenium/Ferrocene Redox Couple for Studying Solvent Effects on the Thermodynamics of Electron Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 6713–6722. [Google Scholar]

- 49.https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrode_potential#Sign_conventions (accessed June 22, 2021)

- 50.Anson FC Common sources of confusion; Electrode Sign Conventions. J. Chem. Educ 1959, 36, 394–395. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pourbaix’s potential/pH diagrams of chemical equilibria are a particularly elegant demonstration of the thermodynamic relationship between potential and equilibria. Pourbaix, M. Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions; National Association of Corrosion Engineers: Houston, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Djerassi C The Oppenauer oxidation. Org. React 2011, 6, 207–272. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bobbitt JM; Brückner C; Merbouh N Oxoammonium- and Nitroxide-Catalyzed Oxidations of Alcohols. In Organic Reactions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2009; pp 103–424. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Francke R; Little RD Redox Catalysis in Organic Electrosynthesis: Basic Principles and Recent Developments. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 2492–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang F; Rafiee M; Stahl SS Electrochemical Functional-Group-Tolerant Shono-Type Oxidation of Cyclic Carbamates Enabled by Aminoxyl Mediators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6686–6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bard AJ; Faulkner LR Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Couper AM; Pletcher D; Walsh FC Electrode Materials for Electrode Synthesis. Chem. Rev 1990, 90, 837–885. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jörissen J Practical Aspects of Preparative Scale Electrolysis. In Encyclopedia of Electrochemistry; Bard AJ, Stratmann M, Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2007; Vol. 8, pp 25–72. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heard DM; Lennox AJJ Electrode Materials in Modern Organic Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 18866–18884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.