Abstract

This study examined the efficacy of end-ischemic hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation (HOPE) using an originally developed machine perfusion system for split-liver transplantation. Porcine split-liver grafts were created via 75% liver resection after 10 min of warm ischemia. In Group 1, grafts were preserved by simple cold storage (CS) for 8 h (CS group; n = 4). In Group 2, grafts were preserved by simple CS for 6 h and end-ischemic HOPE for 2 h (HOPE group; n = 5). All grafts were evaluated using an isolated ex vivo reperfusion model with autologous blood for 2 h. Biochemical markers (aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase levels) were significantly better immediately after reperfusion in the HOPE group than in the CS group. Furthermore, the HOPE group had a better histological score. The levels of inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-10) were significantly lower after reperfusion in the HOPE group. Therefore, we concluded that end-ischemic HOPE for split-liver transplantation can aid in recovering the graft function and reducing ischemia–reperfusion injury. HOPE, using our originally developed machine perfusion system, is safe and can improve graft function while attenuating liver injury due to preservation.

Subject terms: Preclinical research, Liver diseases

Introduction

With the increasing number of patients waiting for liver transplantation, donor shortage has become a serious problem. Split-liver transplantation can help increase the available donor pool but can create two extended-criteria grafts and increase the risk of transplant failure1,2. Hence, split-liver grafts may be considered marginal because of their small size3 and the degree of incurred injury due to liver splitting4. Moreover, poor post-transplantation outcomes have been reported even with a warm ischemic time of 10 min5. We reported higher liver deviation enzyme levels and vascular resistance during reperfusion with split-liver grafts than those with whole-liver grafts6. Our experiments in pigs demonstrated that the split-liver graft is a marginal graft and cold storage (CS) is unsuitable for storing these grafts6. The use of marginal donor livers is associated with a high risk of primary graft dysfunction or severe ischemic injury and can lead to poor outcomes, thus requiring machine perfusion (MP)7. In MP, oxygen, electrolytes, and nutritional elements are continuously provided and harmful metabolites are washed out. Therefore, MP can help maintain, recover, and evaluate graft functions.

Over the past decade, end-ischemic perfusion after CS has become a more attractive option than simple CS8–11. End-ischemic perfusion can be performed after organ transport for pre-transplant evaluation, and we consider it to be the most clinically relevant method for improving graft function after preservation. It implies a lower risk of shear stress because of a shorter perfusion time12. The idea behind end-ischemic MP after initial CS is based on the assumption that metabolic and structural changes during the ischemic period may not be irreversible. In fact, in contrast to exposure of any ischemic tissue to oxygen under normothermic conditions, oxygen delivery under cold conditions has been reported to be very effective in increasing cellular energy with only minor oxidative stress13. The underlying mechanism predominantly involves mitochondrial repair14,15. End-ischemic hypothermic oxygenated perfusion considerably increases the levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in several tissues16,17 and decreases the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) subsequently released during implantation13,14,18.

In collaboration with an industrial machinery company, we developed the first proprietary hospital-based perfusion storage device for livers in Japan. This device is ideal for end-ischemic hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation (HOPE).

To our knowledge, this is the first study on HOPE for split-liver transplantation in pigs. Here, we evaluated the effectiveness and mechanism of end-ischemic HOPE using our MP system for split-liver transplantation.

Methods

Animals

For this study, 2–3-month-old female domestic pigs weighing approximately 20 kg (Large-Yorkshire, Landrace, and Duroc crossbred hogs; Taisetsu-Sanroku-Sya, Asahikawa, Japan) were used. The pigs were brought into a gauge equipped with an automatic water supply system 3–4 days before the experiment and fed with 1.2–1.5 kg of food daily. Additionally, they were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment (12-h light/12-h dark cycle).

This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals. All animals received humane care following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication 86-23, revised in 1985). The Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of the Clinical Research Center at Asahikawa Medical University, Japan (permit no. 14172) approved all experimental procedures.

Liver procurement

Fasting management was performed 12 h before the experiment for safe administration of general anesthesia.

Midazolam (0.25 mg/kg), medetomidine hydrochloride (0.05 mg/kg), and butorphanol tartrate (0.25 mg/kg) were injected for anesthetic induction.

A peripheral ear vein was cannulated with a 22G intravenous catheter, and Ringer’s lactate solution was infused at a rate of 200 mL/h.

Thiamylal sodium (15 mg/kg) was intravenously injected, and intubation was performed using a 5.5-mm endotracheal tube.

Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (2%) (Forane VR; Abbot Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and oxygen (2 L/min). The respiratory conditions were as follows: tidal volume, 10–15 mL/kg; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and inspiratory:expiratory ratio, 1:2. All experiments were performed under sufficient anesthesia.

A 6-Fr central venous catheter was inserted through the left internal jugular vein, and 500 mL of 6% hydroxyethyl starch (Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) was infused until the end of autologous blood procurement.

The domestic pigs underwent midline laparotomy.

The right common iliac artery was isolated, and a 14-Fr Nelaton catheter was inserted into the vein to procure approximately 1000 mL of autologous whole blood.

In preparation for liver exposure, the hepatic artery (HA), portal vein (PV), bile duct, and upper and lower parts of the hepatic inferior vena cava were dissected and taped.

The abdominal aorta was cross-clamped to start warm ischemia. Simultaneously, cardiac arrest was induced with intravenous potassium chloride (2 mEq/kg). No heparin was administered before cardiac arrest.

After 10 min (10 min of warm ischemic time simulated the donation after circulatory death (DCD) Liver), 1000 mL of Euro-Collins solution containing 3000 units of heparin at 4 °C was perfused from the right common iliac artery. While cooling the liver with crushed ice, the liver was rapidly removed.

Standard bench preparation was performed. The portal and arterial systems were cannulated using our original plastic perfusion cannulas of appropriate size. The isolated liver was washed with 1000 mL of UW-gluconate solution at 4 °C.

Porcine split-liver grafts were created via 75% liver resection.

Grafts were preserved by CS in UW-gluconate solution at 4 °C.

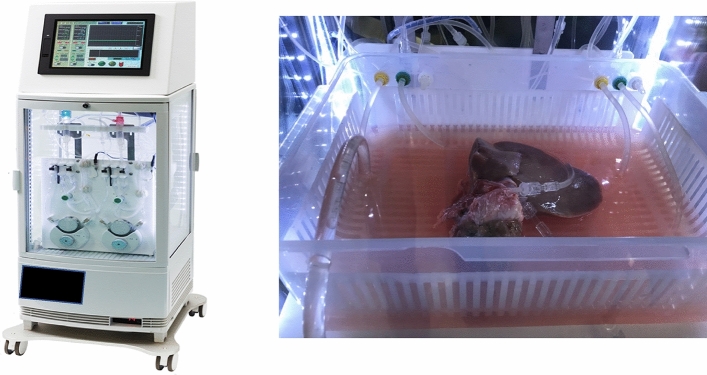

Perfusion preservation machine

The grafts were perfused using an originally developed MP system (CMP-X04W; Chuo Seiko Co., Ltd., Asahikawa, Japan) (Fig. 1). The perfusion pressure was controlled at 5–8 and 30–50 mmHg for the PV and HA, respectively, by adjusting the flow rate. The perfusion fluid was a UW solution, with the temperature set at 4 °C. The partial oxygen pressure in the perfusate was controlled at 250 mmHg (FiO2 of 0.4 at 2 L/min). The perfusion time was set at 2 h after 6 h of simple CS.

Figure 1.

Perfusion preservation machine. The grafts were perfused using an originally developed MP system (CMP-X04W; Chuo Seiko Co., Ltd., Asahikawa, Japan).

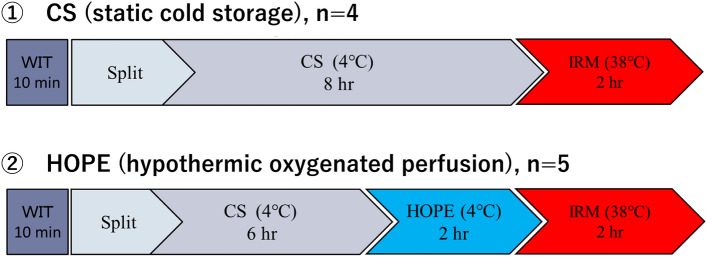

Experimental design

Figure 2 illustrates the experimental design. Porcine split-liver grafts were created via 75% liver resection after 10 min of warm ischemia. In Group 1, grafts were preserved by simple CS for 8 h (CS group; n = 4). In Group 2, grafts were preserved by simple CS for 6 h and end-ischemic HOPE for 2 h (HOPE group; n = 5). All grafts were evaluated using an isolated ex vivo reperfusion model (ERM) with autologous blood for 2 h.

Figure 2.

Experimental design. Porcine split-liver grafts were created via 75% liver resection after 10 min of warm ischemia. In Group 1, grafts were preserved by simple CS for 8 h (CS group; n = 4). In Group 2, grafts were preserved by simple CS for 6 h and end-ischemic HOPE for 2 h (HOPE group; n = 5). All grafts were evaluated using an isolated ERM with autologous blood for 2 h. CS cold storage, ERM ex vivo reperfusion model, HOPE hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation.

Isolated ERM

After preservation, the liver function was evaluated using an isolated liver reperfusion model6,19,20. This system consisted of HA and PV perfusion circuits, with each circuit comprising a roller-type pump (Masterflex 7520-40; Cole-Parmer, Bunker Court, IL, USA), electrical flow meter (VN05; Aichi Tokei, Aichi, Japan for the PV; FD-SS02; Keyence, Osaka, Japan for the HA), ceramic capacitive pressure sensor (KL76; Nagano Keiki, Nagano, Japan), and an air trap developed in-house. An oxygenator (HP0-06 H-C; Senko Medical Instrument, Tokyo, Japan) was installed in the circuit for the PV and HA.

After preservation, all the organs were rinsed with 500 mL of cold Euro-Collins solution and subsequently exposed at room temperature (20–25 °C) without perfusion to simulate the slow rewarming of grafts during surgical implantation in vivo. HA reperfusion was set at 80 mmHg and automatically maintained by a roller pump connected to a pressure sensor placed in the inflow line immediately before the arterial cannula. PV reperfusion was set at 5–8 mmHg. The reperfusion fluid was autologous whole blood containing 30 mL of calcium gluconate hydrate (8.5%) and heparin. Heparin levels were adjusted for the activated clotting time to be 300 s. The livers were subsequently reperfused with oxygenated diluted autologous blood at 38 °C. The hematocrit was maintained at approximately 10–12%. The oxygenator was regulated to achieve physiological blood gas values (pO2, approximately 150–200 mmHg; pCO2, approximately 30–50 mmHg).

Viability assessment during MP

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase, and hyaluronic acid levels in the perfusate were measured at 0 and 2 h for HOPE and every 60 min for the ERM to determine the viability of preserved liver grafts using standard biochemical methods (clinical grade). Additionally, lactate, potassium, and carboxyhemoglobin (CO-Hb) levels in the perfusate were measured every 60 min for the ERM using a blood gas analyzer (ABL800 FLEX; Radiometer, Tokyo, Japan).

Histopathological evaluation

Liver wedge biopsy was performed immediately after laparotomy and preservation (simple CS and HOPE) and 2 h after isolated ex vivo reperfusion. Tissue ATP levels were quantified using homogenized liver biopsy tissues. Liver tissues were fixed using 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and dehydrated using ethanol. Paraffin-embedded renal sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for morphological evaluation. The Suzuki classification21 was applied to evaluate ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI). Sinusoidal congestion, hepatocyte cytoplasmic vacuolization, and parenchymal necrosis were scored from 0 to 4. The histopathological findings of each hepatic section were scored blindly in ≥ 10 randomly selected non-overlapping fields under light microscopy.

CD42b and ERG immunohistochemistry was performed to assess sinusoidal endothelial cell injury and intrasinusoidal platelet aggregation. The primary antibodies were a rabbit anti-ERG monoclonal antibody (clone EP111; Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) and a rabbit anti-CD42b polyclonal antibody (GeneID 2811; Proteintech Group, IL, USA). The secondary antibody was an EnVision-labeled polymer reagent (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Anti-ERG staining-positive and anti-CD42b staining-positive areas were quantified using ImageJ (US National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The number of anti-ERG staining-positive sinusoid epithelial cells (SEC) nuclei and the positive area of anti-CD42b staining were automatically counted in ≥ 10 randomly selected non-overlapping fields.

Gene expression

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was used to determine gene expression of endothelial-specific, inflammatory, and apoptotic proteins. Liver parenchyma biopsy was performed after laparotomy and preservation and 2 h after isolated ex vivo reperfusion. The samples were stored at − 80 °C until analysis. Total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen liver biopsies using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The RNA concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000; NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Equal RNA amounts were converted to complementary DNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland); complementary DNA levels were measured using LightCycler 480 System II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The relative expression of the mRNA of interest was normalized to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The data are presented as relative quantification to GAPDH. Table 1 summarizes sense and antisense primer sequences.

Table 1.

PCR primer.

| Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | AGGAGTAAGAGCCCCTGGAC | GTGTGTTGGGGGATCGAGT |

| TNF-α | TTGTCGCTACATCGCTGAAC | CCAGTAGGGCGGTTACAGAC |

| IFNγ | TTCAGCTTTGCGTGACTTTG | TGCATTAAAATAGTCCTTTAGGATCG |

| IL-1β | GGAAAGCCATACCCAGAGGT | CAGTCCCCTTCTGTCAGCTT |

| Caspase-3 | GAATGGCATGTCGATCTGGT | TTGTGAAGGTCTCCCTGAGATT |

| NOS2 | CCATGGAACACCCCAAATAC | GCAGGGCGTACCACTTCA |

| IL-4 | GAGAACACGACGGAGAAGGA | TCTGTAGATGTGCCGAAGCA |

| IL-6 | TGAACTCCCTCTCCACAAGC | GGCAGTAGCCATCACCAGA |

| IL-10 | TCCAGTTTTACCTGGAAGACG | CCTTGATATCCTCCCCATCA |

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR version 1.41 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan)22, based on R and R commander. The results were obtained using the t-test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

HOPE results

The perfusion volumes of both portal and hepatic arteries were stabilized at 0.50 and 0.05 mL/min/100 g liver, respectively, within 15 min after starting perfusion preservation and maintained until the end of perfusion preservation. The storage vessel temperature during perfusion preservation was stable at 4 °C. The AST and LDH levels were not significantly different at the start and end of perfusion preservation. The AST levels at 0 and 120 min of perfusion preservation were 82.33 ± 14.13 and 115.48 ± 27.60 IU/L/100 g liver, respectively (0 vs. 120 min; P = 0.316), whereas LDH levels at 0 and 120 min of perfusion preservation were 88.22 ± 0.87 and 145.42 ± 11.37 IU/L/100 g liver, respectively (0 vs. 120 min; P = 0.056).

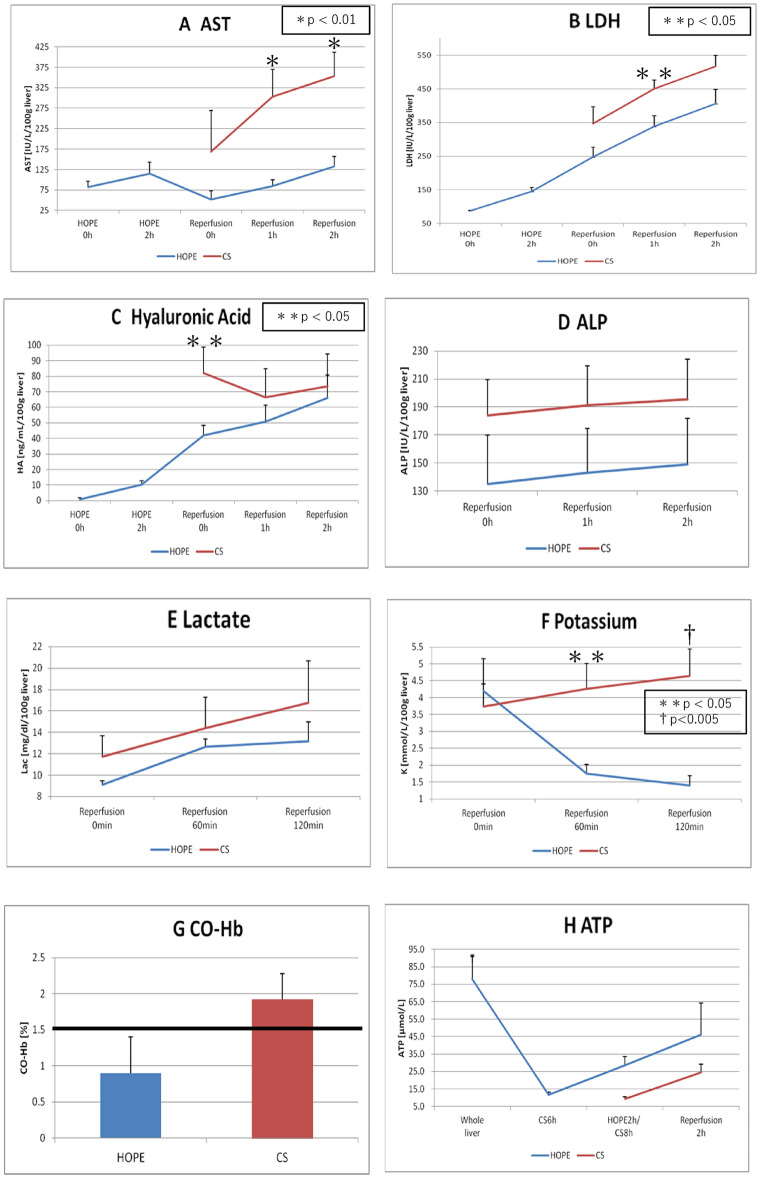

Liver enzyme levels after reperfusion and IRI

AST levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3A presents AST levels after reperfusion. At 60 min and the end of reperfusion, the AST levels were significantly lower in the HOPE group (84.25 ± 15.90 and 132.31 ± 24.80 IU/L/100 g liver) than in the CS group (303.40 ± 66.75 and 353.12 ± 58.94 IU/L/100 g liver) (HOPE vs. CS; P = 0.009, P = 0.007).

Figure 3.

Laboratorial results. (A) Aspartate aminotransferase concentration (IU/L/100 g liver), (B) lactate dehydrogenase concentration (IU/L/100 g liver), (C) hyaluronic acid concentration (ng/mL/100 g liver), (D) alkaline phosphatase concentration (IU/L/100 g liver), (E) lactate concentration (mg/dL/100gliver), and (F) potassium concentration (mmol/L/100 g liver) value (mean ± SD) in the perfusate over time (hours) during HOPE and ERM. (G) Carboxyhemoglobin concentration (%) values (mean ± SD) in the perfusate at 2 h after ERM. (H) Tissue adenosine triphosphate level (μmol/L) values (mean ± SD) after laparotomy, after preservation (simple cold storage [CS] and HOPE), and at 2 h after isolated ERM. ERM ex vivo reperfusion model, HOPE hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation, SD standard deviation.

LDH levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3B presents LDH levels after reperfusion. At 60 min of reperfusion, the LDH levels were significantly lower in the HOPE group than in the CS group (338.43 ± 31.75 vs. 450.86 ± 25.36 IU/L/100 g liver; P = 0.033). The LDH levels at the end of reperfusion were not different between the groups (406.36 ± 41.50 IU/L/100 g liver [HOPE] vs. 516.61 ± 32.84 IU/L/100 g liver [CS]; P = 0.086).

Hyaluronic acid levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3C presents hyaluronic acid levels after reperfusion. At 0 min of reperfusion, the hyaluronic acid levels were significantly lower in the HOPE group than in the CS group (41.88 ± 6.57 vs. 82.20 ± 16.52 ng/mL/100 g liver; P = 0.043). However, the hyaluronic acid levels at the end of reperfusion were not different between the groups (66.17 ± 14.64 vs. 73.64 ± 20.73 ng/mL/100 g liver; P = 0.771).

Alkaline phosphatase levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3D presents alkaline phosphatase levels after reperfusion; no differences were observed between the groups. At 120 min of reperfusion, alkaline phosphatase levels in the HOPE and CS groups were 149.18 ± 32.87 and 195.31 ± 28.69 IU/L/100 g liver, respectively (P = 0.339).

Lactate levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3E presents lactate levels after reperfusion; no differences were observed between the groups. At 120 min of reperfusion, the lactate levels in the HOPE and CS groups were 13.16 ± 1.79 and 16.75 ± 3.92 mg/dL/100 g liver, respectively (P = 0.399).

Potassium levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3F presents potassium levels after reperfusion. At 60 min and the end of reperfusion, the potassium levels were significantly lower in the HOPE group (1.74 ± 0.28 and 1.40 ± 0.27 mmol/L/100 g liver) than in the CS group (4.26 ± 0.74 and 4.64 ± 0.80 mmol/L/100 g liver) (HOPE vs. CS; P = 0.010, P = 0.004).

CO-Hb levels in the perfusion solution

Figure 3G presents CO-Hb levels at the end of reperfusion. The CO-Hb level, an IRI marker, was > 1.5% in the CS group. However, CO-Hb levels at the end of reperfusion were not different between the groups (0.90 ± 0.50% vs. 1.93 ± 0.36%; P = 0.159).

ATP levels in liver tissues

Figure 3H presents ATP levels in liver tissues. At the end of reperfusion, ATP levels were not different between the groups (46.20 ± 40.30 vs. 24.48 ± 9.72 µmol/L; P = 0.333).

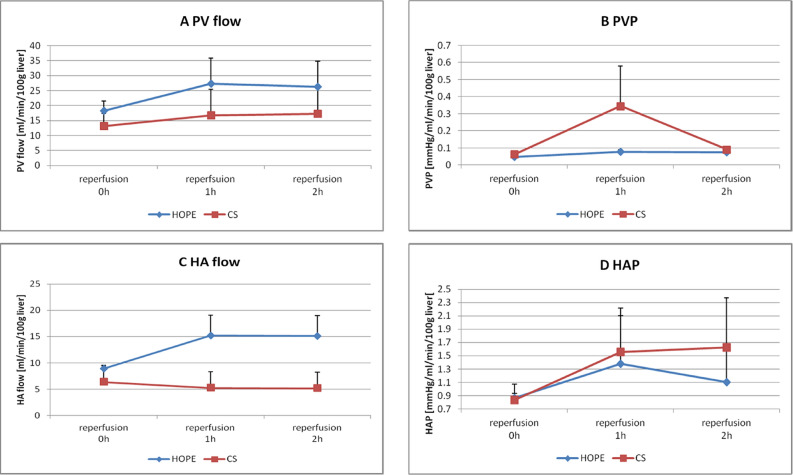

Vascular flow volume and pressure resistance

PV flow and pressure resistance after reperfusion

Figure 4A,B present the results for PV flow and pressure, respectively. After reperfusion, no differences in the PV flow and pressure were observed between the groups. At 120 min of reperfusion, the PV flow in the HOPE and CS groups was 26.28 ± 8.46 and 17.22 ± 8.91 mL/min/100 g liver, respectively (P = 0.489). At 120 min of reperfusion, the PV pressure in the HOPE and CS groups was 0.07 ± 0.013 and 0.09 ± 0.02 mmHg/mL/min/100 g liver, respectively (P = 0.454).

Figure 4.

Vascular flow volume and pressure resistance. (A) Portal vein flow (mL/min/100 g liver), (B) PV pressure (mmHg/mL/min/100 g liver), (C) hepatic artery flow (mL/min/100 g liver) and (D) HA pressure value (mean ± standard deviation) over time (hours) during the ex vivo reperfusion model.

HA flow and pressure resistance

Figure 4C,D present the results for HA flow and pressure, respectively. After reperfusion, HA flow and pressure were not different between the groups. At 120 min of reperfusion, HA flow in the HOPE and CS groups was 15.13 ± 3.85 and 5.18 ± 3.04 mL/min/100 g liver, respectively (P = 0.125). At 120 min of reperfusion, HA pressure in the HOPE and CS groups was 1.10 ± 0.56 and 1.62 ± 0.75 mmHg/mL/min/100 g liver, respectively (P = 0.617).

Histological findings after reperfusion

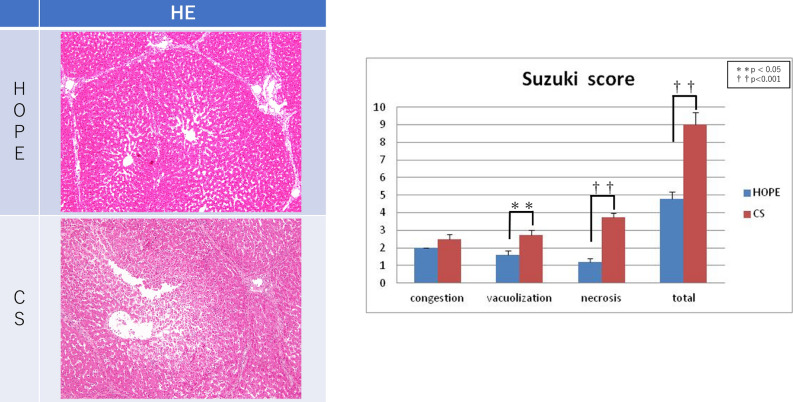

Hematoxylin–eosin staining

The histological findings indicated irregular liver cell structure in the CS group but not in the HOPE group (Fig. 5). Specifically, the sinusoidal structure was maintained in the HOPE group and more necrotic areas were observed in the CS group. Under high-power magnification, the liver cells exhibited more lipid drops in the CS group. Figure 5 presents the Suzuki scores for hepatic IRI at the end of reperfusion. The HOPE group scored significantly better regarding vacuolization and necrosis than the CS group. The total Suzuki scores indicated significant morphological changes in the HOPE group (4.80 ± 0.37) compared to the CS group (9.00 ± 0.71) (P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Pathological findings. Histological findings indicated that the liver cell structure was irregular in the CS group but remained regular in the HOPE group. In particular, the sinusoidal structure was maintained in the HOPE group, and more necrotic areas were observed in the CS group. Under high-power magnification, the liver cells exhibited more lipid drops in the CS group than in the HOPE group. The total Suzuki scores indicated significant morphological changes in the HOPE group (4.80 ± 0.37), as compared to the CS group (9.00 ± 0.71) (P < 0.001). CS cold storage, HOPE hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation.

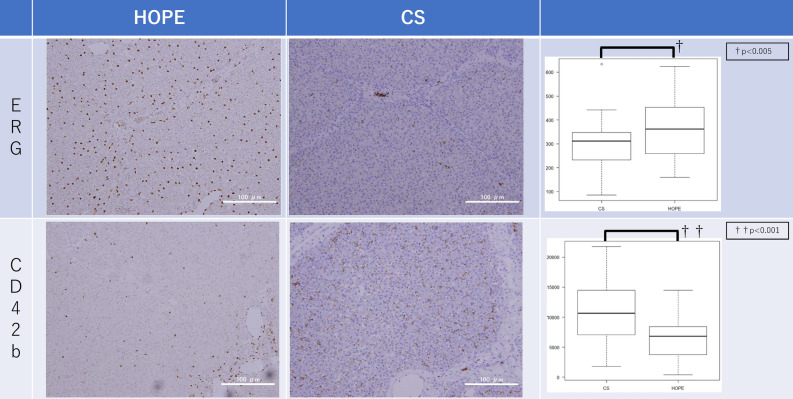

ERG and CD42b immunohistochemistry

Figure 6 shows the ERG and CD42b results. At the end of reperfusion, the HOPE group had significantly higher numbers of anti-ERG staining-positive SEC nuclei than the CS group (360.54 ± 118.87 vs. 285.13 ± 107.87 per field; P = 0.002) and a significantly smaller positive area of anti-CD42b staining than the CS group (6317.06 ± 3235.14 vs. 10,761.50 ± 5643.620 per field; P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry. At the end of reperfusion, the number of anti-ERG staining-positive SEC nuclei counted automatically by ImageJ in the HOPE group (360.54 ± 118.87 per field) was significantly higher than that in the CS group (285.13 ± 107.87 per field) (P = 0.002). At the end of reperfusion, the positive area of anti-CD42b staining counted automatically by ImageJ in the HOPE group (6317.06 ± 3235.14 per field) was significantly smaller than that in the CS group (10,761.50 ± 5643.620 per field) (P < 0.001). CS cold storage, HOPE hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation, SEC sinusoid epithelial cells.

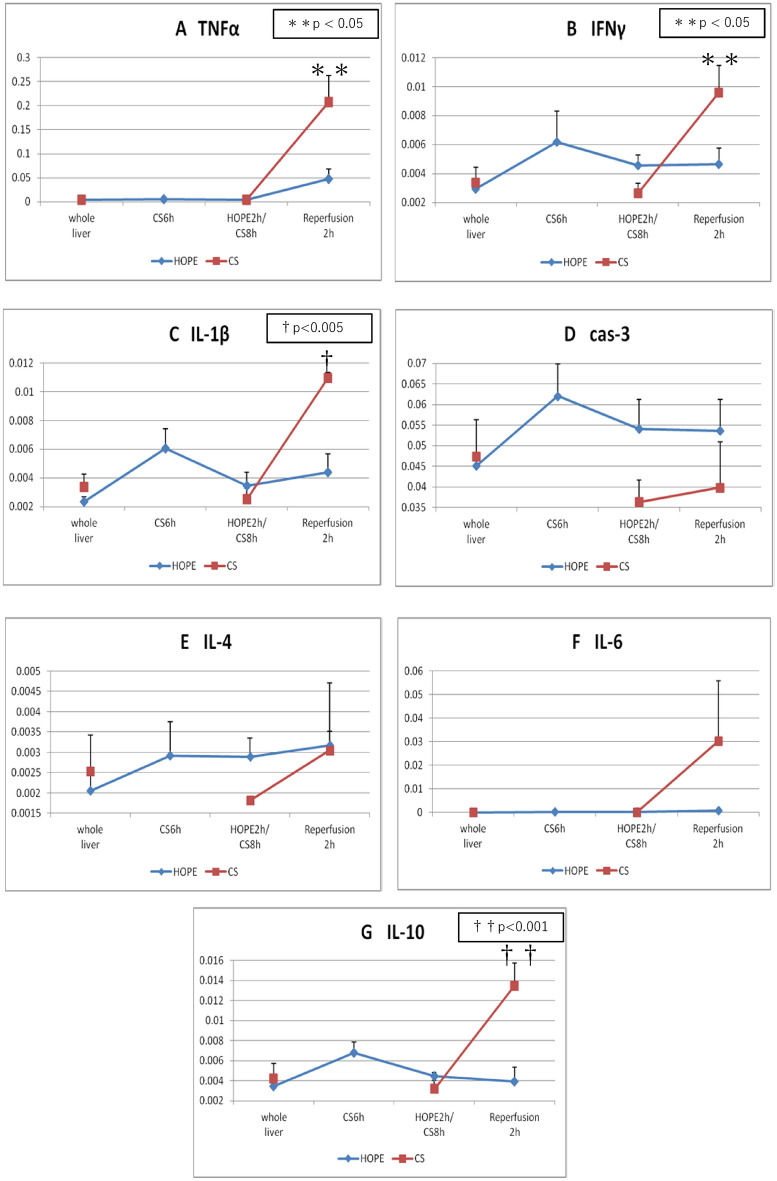

Gene expression

Figure 7 shows the gene expression results. At the end of reperfusion, the DAMP gene expression was significantly lower in the HOPE group than in the CS group: tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), 0.0476 ± 0.0446 vs. 0.2080 ± 0.1084, respectively, P = 0.019 (Fig. 7A); interferon-γ, 0.0047 ± 0.0025 vs. 0.0096 ± 0.0038, respectively, P = 0.049 (Fig. 7B); interleukin-1β, 0.0044 ± 0.0029 vs. 0.0110 ± 0.0008, respectively, P = 0.003 (Fig. 7C); and interleukin-10, 0.0039 ± 0.0032 vs. 0.0135 ± 0.0045, respectively, P = 0.008 (Fig. 7G). The HOPE and CS groups did not differ regarding caspase-3 (0.0537 ± 0.0170 vs. 0.0399 ± 0.0221; P = 0.323; Fig. 7D), interleukin-4 (0.0032 ± 0.00342 vs. 0.0030 ± 0.0009; P = 0.944; Fig. 7E), and interleukin-6 (0.0004 ± 0.0007 vs. 0.0030 ± 0.0512; P = 0.228; Fig. 7F) expression.

Figure 7.

Polymerase chain reaction. (A) Tumor necrosis factor α, (B) interferon γ, (C) IL-1β, (D) caspase-3, (E) Il-4, (F) IL-6 and (G) IL-10 value (mean ± SD) after laparotomy, after preservation (simple CS and HOPE), and at 2 h after isolated ERM. CS cold storage, ERM ex vivo reperfusion model, HOPE hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion preservation, IL interleukin, SD standard deviation.

Discussion

The optimal temperature and timing for perfusion preservation remain controversial. Recently, there have been several reports on HOPE13,23–26. We focused on this preservation method, as we believe it has real clinical relevance. Patrono et al.23 reported that the use of HOPE for grafts obtained from donation after brain death was associated with a significant reduction in stage 2–3 acute kidney injury and severe post-reperfusion syndrome, a lower incidence of early allograft dysfunction, and a reduced post-transplantation AST and ALT peak. Although normothermic MP (NMP) has been previously reported27, NMP has the following problems. Higher preservation temperatures require higher oxygen demand of the organs28. Therefore, dissolved oxygen alone is insufficient in NMP, and oxygen carriers are required. Additionally, metabolism is increased; hence, a dialysis system is also needed to remove waste products, making it more complicated and costly. In NMP, if the perfusion system fails, oxygenation and waste removal may not be possible and organ damage may occur. Conversely, with HOPE, if a failure occurs in the perfusion system, the system simply converts to simple CS, ensuring safety. Furthermore, NMP carries the risk of bacterial contamination, bacterial growth, and coagulation in the circuit29.

Endothelial cell effects

HOPE has at least four protective mechanisms against lethal impairment of hepatic flow in parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells29. Flow cessation results in a significant reduction in several endothelial vasoprotective pathways. The negative effects of CS conditions are partly attributable to the loss of Kruppel-like factor 2 expression, a vasoprotective transcription factor30. MP may trigger endothelial protection via the upregulation of shear stress-sensitive protective genes31. Our ERG immunohistochemistry experiments showed that the HOPE group had significantly more endothelial cells (Fig. 6), supporting the hypothesis that HOPE provides more protection for endothelial cells during reperfusion. Platelet aggregation after reperfusion leads to intrasinusoidal mechanical occlusion and exacerbates sinusoidal endothelial cell viability loss and microcirculatory blood flow disruption. Elevated liver enzyme levels after reperfusion illustrated the disturbance in sinusoidal microcirculation. Our experiments revealed that the HOPE group had significantly better liver enzyme (AST and LDH) levels after reperfusion (Fig. 3A,B).

Hepatocyte effects

Current research suggests a key role of hepatocyte-released DAMPs during early reperfusion, with a steep increase during the first 4–6 h17,32,33. Reperfusion injury shifts from pure metabolic distress to a potentially lethal innate immune response32. HOPE triggers a unique decrease in DAMPs levels during early reperfusion of liver grafts obtained from donors after cardiac death8,13,14,34. In our experiment, DAMPs levels (TNF-α, interferon-γ, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-10) were significantly lower in the HOPE group than in the CS group (Fig. 7). Our results were similar to our previous findings and those of prior reports.

Mitochondrial effects

Selective accumulation of the citric acid cycle has been recently shown as a universal signature of ischemia and is responsible for mitochondrial ROS production in all cell types during reperfusion35. Upon reperfusion, the accumulated succinate is rapidly reoxidized, driving extensive ROS generation by reverse electron transport at mitochondrial complex I35,36. HOPE prevents the initial mitochondrial ROS release and appears as a novel treatment that shifts anaerobic metabolism to aerobic metabolism under cold conditions, together with huge ATP reload. Our results were similar to our previous findings and those of prior reports (Fig. 3H).

HOPE-preserved liver grafts release potassium in the perfusate during MP and take up potassium upon reperfusion. This prevents acute hyperkalemia, which is frequently associated with severe post-reperfusion syndrome. HOPE is likely to impair optimal Na+/K+-ATPase function, facilitating passive potassium release. This underlines the potential role of ATP-dependent hepatic potassium uptake in HOPE-preserved livers37. In our experiment, at 60 min and the end of reperfusion, the HOPE group had significantly lower potassium levels than the CS group (Fig. 3F).

Cellular defense effects

Low ROS levels are protective and may trigger the activation of numerous pathways (PKCe, SIRT1, Nrf-2, and HIF-1). These pathways increase antioxidant enzyme activation (glutathione synthase, heme oxygenase, catalase, glutathione, and manganese superoxide dismutase) and expression of angiogenic (erythropoietin) and survival proteins (mitogen-activated protein kinase)33. Furthermore, hypothermic MP may upregulate defense pathways via minor ROS release during cold perfusion, particularly in livers exposed to warm ischemia before perfusion.

In our study, the levels of TNF-α, a representative factor of DAMP, were significantly lower in the HOPE group and a hepatocyte-protective effect was observed (Fig. 7A). The AST and LDH levels remained significantly lower in the HOPE group during reperfusion (Fig. 3A,B), suggesting a hepatocyte-protective effect. During reperfusion, when the blood flow is reestablished, the damage caused during the ischemic period is aggravated by reoxygenation. This is initiated by the mitochondrial release of ROS due to an inhibited electron transport chain causing Kupffer cell activation, which releases proinflammatory cytokines (including TNF-α/interleukin-1β), recruits neutrophils, and induces adhesion molecule expression in sinusoidal endothelial cells. Activated neutrophils produce more ROS, perpetuating the inflammatory response that ultimately results in tissue damage and initiation of cell death programs37–39. Additionally, endogenous carbon monoxide is produced by heme metabolism in humans40. Heme oxygenase-1 is a rate-limiting enzyme for heme degradation and a stress protein induced by oxidative stress41. CO-Hb levels were lower in the HOPE group (Fig. 3G), suggesting less oxidative stress after reperfusion.

In addition, as compared to extracorporeal splitting, intracorporeal splitting has the following advantages: (1) shorter cold ischemia time; (2) better identification of the bile duct and vascular tissues, exact management of the liver section, and reduced incidence of section bleeding and bile leakage; (3) reduced rewarming injury; (4) ability to observe the blood supply and reflux in each liver segment after splitting, facilitating more rational allocation of donor vessels; and (5) complete hemostasis of the section during splitting, thereby reducing sectional bleeding during reperfusion in the recipients42. Therefore, application of extracorporeal splitting with MP to simulate intracorporeal splitting tends to take full advantage of the latter43. Mabrut et al. described the first two cases of liver transplantation with concurrent liver splitting and HOPE44. We have reported good results of splitting during MP6.

Here, we simulated and evaluated post-transplant reperfusion using an ERM. The livers were evaluated by reperfusion with oxygenated diluted autologous blood at 38 °C rather than after transplantation. We reported that the ERM can be useful for evaluating MP utility19,20. This isolated ERM can reduce the need for animal transplantation experiments and the technical bias associated with the actual transplantation operation, and facilitate observation of hemodynamic changes (perfusion area and vascular pressure resistance) during reperfusion. The ERM can be used to investigate events occurring in the early phases of reperfusion. Indeed, parameters of interest and biomarkers released during isolated liver perfusion tend to mainly reflect hepatocellular and endothelial injury and, to some degree, cholangiocyte injury, showing a pattern that fairly resembles our current knowledge of the sequence of events occurring in the early stages of IRI in animal experiments and clinical transplantation45.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the present study involved 2 h assessment using an ERM. Hence, we need to conduct long-term assessment of the immune response, particularly in actual transplantation. However according to previous study, 2 h assessment after reperfusion was enough for evaluating the efficacy of HOPE in this model. Second, bile assessment was not performed in this study. Lastly, this study did not include larger split-liver grafts.

In conclusion, end-ischemic HOPE for split-liver transplantation can help recover graft function and reduce IRI. HOPE, using CMP-X04W, is safe and can improve graft function while attenuating liver injury due to preservation. This approach has shown significant advantages compared to the conventional CS and might expand this technology into recovery and amelioration of marginal grafts as split-liver grafts.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid of Ishidsu Shun Memorial Scholarship, Japan.

Author contributions

N.M., H.Y., and H.F. designed the study. D.I., M.G., I.T., and T.S. performed the experiment. H.O. collected the data. D.I. analyzed the data. Y.N. contributed to the discussion of the results. D.I. drafted the manuscript. N.M. supervised the drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for (B) (#15H03922 to H.O.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and a Grant-in-Aid for Innovative Research in Life Science from Asahikawa Medical University.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

Naoto Matsuno has received a research fund from Chuo Seiko Co., Ltd., which was used to fund this study. Daisuke Ishii, Mikako Gochi, Hiroyoshi Iwata, Tatsuya Shonaka, Yuji Nishikawa, Hiromichi Obara, Hideki Yokoo, and Hiroyuki Furukawa declare no potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pichlmayr R, Ringe B, Gubernatis G, Hauss J, Bunzendahl H. Transplantation of a donor liver to 2 recipients (splitting transplantation)—A new method in the further development of segmental liver transplantation. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1988;373:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalal AR. Split liver transplantation: What's unique? World J. Transpl. 2015;5:89–94. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v5.i3.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto K, et al. Split liver transplantation in adults. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;5:89–94. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i33.7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spada M, et al. The new horizon of split-liver transplantation: Ex situ liver splitting during hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:1363–1367. doi: 10.1002/lt.25843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He XS, et al. Safe time to warm ischemia and posttransplant survival of liver graft from non-heart-beating donors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3157–3160. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i21.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii D, et al. Applicability of hypothermic oxygenate machine perfusion preservation for split-liver transplantation in a porcine model: An experimental study. Ann. Transpl. 2020;14:e919920. doi: 10.12659/AOT.919920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vera ME, et al. Liver transplantation using donation after cardiac death donors: Long-term follow-up from a single center. Am. J. Transpl. 2009;9:773–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minor T, Paul A. Hypothermic reconditioning in organ transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transpl. 2013;18:161–167. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32835e29de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutkowski P, de Rougemont O, Clavien PA. Machine perfusion for ’marginal’ liver grafts. Am. J. Transpl. 2008;8:917–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuller BJ, Lee CY. Hypothermic perfusion preservation: The future of organ preservation revisited? Cryobiology. 2007;54:129–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koetting M, et al. Optimal time for hypothermic reconditioning of liver grafts by venous systemic oxygen persufflation in a large animal model. Transplantation. 2011;91:42–47. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181fed021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain S, et al. Ex-vivo study of flow dynamics and endothelial cell structure during extended hypothermic machine perfusion preservation of livers. Cryobiology. 2004;48:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlegel A, et al. Warm vs. cold perfusion techniques to rescue rodent liver grafts. J. Hepatol. 2014;61:1267–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlegel A, Rougemont O, Graf R, Dutkowski P, Clavien PA. Protective mechanisms of endischemic cold machine perfusion in DCD liver grafts. J. Hepatol. 2013;58:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olthof PB, Reiniers MJ, Dirkes MC, Gulik TM, Golen RF. Protective mechanisms of hypothermia in liver surgery and transplantation. Mol. Med. 2016;21:833–846. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minor T, et al. Energetic recovery in porcine grafts by minimally invasive liver oxygenation. J. Surg. Res. 2012;178:e59–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westerkamp AC, et al. End-ischemic machine perfusion reduces bile duct injury in donation after circulatory death rat donor livers independent of the machine perfusion temperature. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:1300–1311. doi: 10.1002/lt.24200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Golen RF, van Gulik TM, Heger M. Mechanistic overview of reactive species-induced degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx during hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:1382–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshikawa R, et al. Ex vivo reperfusion model to evaluate utility of machine preservation for porcine liver donated after cardiac death. Transpl. Proc. 2018;59:2826–2829. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshikawa R, et al. Evaluation using an isolated reperfusion model for porcine liver donated after cardiac death preserved with oxygenated hypothermic machine perfusion. Ann. Transpl. 2018;23:822–827. doi: 10.12659/AOT.910008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki S, et al. The beneficial effect of a prostaglandin I2 analog on ischemic rat liver. Transplantation. 1999;52:979–983. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrono D, et al. Hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion of liver grafts from brain-dead donors. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:9337. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45843-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quillin RC, Guarrera JV. Hypothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:276–281. doi: 10.1002/lt.25004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Ma Z, Wu S. Hypothermic machine perfusion reduces the incidences of early allograft dysfunction and biliary complications and improves 1-year graft survival after human liver transplantation: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16033. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlegel A, et al. Outcomes of DCD liver transplantation using organs treated by hypothermic oxygenated perfusion before implantation. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasralla D, et al. A randomized trial of normothermic preservation in liver transplantation. Nature. 2018;557:50–56. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujita S, et al. Isolated perfusion of rat livers: effect of temperature on O2 consumption, enzyme release, energy store, and morphology. Nihon Geka Hokan. 1993;62:58–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlegel A, Kron P, Dutkowski P. Hypothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transpl. 2016;21:308–314. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peralta C, Jimenez-Castro MB, Gracia-Sancho J. Hepatic ischemia and reperfusion injury: Effects on the liver sinusoidal milieu. J. Hepatol. 2013;59:1094–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo L, et al. Addition of simvastatin to cold storage solution prevents endothelial dysfunction in explanted rat livers. Hepatology. 2012;55:921–930. doi: 10.1002/hep.24755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golen RF, Gulik TM, Heger M. The sterile immune response during hepatic ischemia/reperfusion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012;23:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhai Y, Petrowsky H, Hong JC, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury in liver transplantation: From bench to bedside. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;10:79–89. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlegel A, Graf R, Clavien PA, Dutkowski P. Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) protects from biliary injury in a rodent model of DCD liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2013;59:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chouchani ET, et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2014;515:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drose S, Stepanova A, Galkin A. Ischemic A/D transition of mitochondrial complex I and its role in ROS generation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1857:946–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laura CB, et al. Opposite acute potassium and sodium shifts during transplantation of hypothermic machine perfused donor livers. Am. J. Transpl. 2019;19:1061–1071. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson JW, Narayanan SV, Perez-Pinzon MA. Redox signaling pathways involved in neuronal ischemic preconditioning. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2012;10:354–369. doi: 10.2174/157015912804143577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion—From mechanism to translation. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marilena G. New physiological importance of two classic residual products: Carbon monoxide and bilirubin. Biochem. Mol. Med. 1997;61:136–142. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1997.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibahara S. Regulation of heme oxygenase gene expression. Semin. Hematol. 1988;25:370–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vagefi PA, Parekh J, Ascher NL, Roberts JP, Freise CE. Ex vivo split-liver transplantation: The true right/left split. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:267–274. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang ZB, Gao W, Liu L, Shi Y, Ma N, Shen ZY. Development and assessment of normothermic machine perfusion preservation for extracorporeal splitting of pig liver. Ann. Transpl. 2017;22:507–517. doi: 10.12659/aot.904483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mabrut JY, et al. Ex vivo liver splitting and hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion: technical refinements of a promising preservation strategy in split liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2021;105(2021):89–90. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Francesca M, Nicholas G, Silvia L. Porcine isolated liver perfusion for the study of ischemia reperfusion injury: A systematic review. Transplantation. 2018;102:1039–1049. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.