Abstract

QseC, a histidine sensor kinase of the QseBC two-component system, acts as a global regulator of bacterial stress resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence. The function of QseC in some bacteria is well understood, but not in Pasteurella multocida. We found that deleting qseC in P. multocida serotype A:L3 significantly down-regulated bacterial virulence. The mutant had significantly reduced capsule production but increased resistance to oxidative stress and osmotic pressure. Deleting qseC led to a significant increase in qseB expression. Transcriptome sequencing analysis showed that 1245 genes were regulated by qseC, primarily those genes involved in capsule and LPS biosynthesis and export, biofilm formation, and iron uptake/utilization, as well as several immuno-protection related genes including ompA, ptfA, plpB, vacJ, and sodA. In addition to presenting strong immune protection against P. multocida serotypes A:L1 and A:L3 infection, live ΔqseC also exhibited protection against P. multocida serotype B:L2 and serotype F:L3 infection in a mouse model. The results indicate that QseC regulates capsular production and virulence in P. multocida. Furthermore, the qseC mutant can be used as an attenuated vaccine against P. multocida strains of multiple serotypes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13567-021-01009-6.

Keywords: Quorum sensing gene, Deletion, Virulence, Vaccine, Cross-protection

Introduction

Pasteurella multocida is a pathogenic bacterium that causes a variety of diseases in livestock, poultry, and humans [1]. It can be classified into five capsular serotypes (A, B, D, E, F) based on capsular polysaccharides [2], and eight genotypes (L1-L8) based on the lipopolysaccharide outer core biosynthesis locus [3, 4]. Various environmental stresses in animals lead to an increase of pasteurellosis caused by P. multocida, which results in significant economic losses. At present, most commercial vaccines for P. multocida are focused on controlling a specific serotype and a universal vaccine against multiple serotypes is lacking.

Quorum sensing (QS) is a bacterial communication system that controls a variety of physiological functions of bacteria including nutrient uptake, biofilm formation, and virulence factor expression [5]. Bacterial quorum sensing systems are divided into four categories: quorum sensing system mediated by acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL), signal peptide, Autoinducers 2 (AI-2), and Autoinducers 3 (AI-3) [6, 7]. Autoinducers (AIs) are secreted and recognized by bacterial quorum sensing system receptors to initiate signal transduction processes after AI concentrations reach a critical threshold [8, 9]. QS inhibitors can be used to downregulate virulence, disrupt bacterial communication, and attenuate infection symptoms [10, 11].

QseC belongs to the QseBC quorum sensing system mediated by AI-3. AI-3 is first recognized by QseC and induces QseC auto-phosphorylation. QseC then dephosphorylates QseB, and then the dephosphorylated QseB activates the expression of specific genes [12, 13]. In addition to activating QseB, QseC can also activate QseF and KdpE, which regulate the expression of virulence- and flagella-related genes [14–16]. Loss of QseC function leads to reduced resistance to environmental stress and to reduced virulence [17–19].

The QseBC quorum sensing system is present in all P. multocida serotypes, but its function in this organism is still unclear. Cross-protection can be promoted by an aroA gene deletion in some P. multocida strains [20]. A Shigella hfq gene mutant provided cross-protection against Shigella strains of broad serotype [21]. In this study, we investigated the role of QseC in P. multocida virulence. Our data support the role of QseC as a regulator of capsule production, virulence, biofilm formation, stress resistance, and show that QseC can negatively regulate the expression of cross-protective antigens in P. multocida. A qseC deletion strains provides robust cross-protection against multiple P. multocida serotypes.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and cultural conditions

Bovine P. multocida capsular serotype A strain CQ2 (A:L3, PmCQ2) was isolated from the lung of a dead calf that suffered from pneumonia in Chongqing, China. Bovine P. multocida capsular serotype A strain CQ1 (A:L3, PmCQ1), CQ4 (A:L3, PmCQ4), and CQ5 (A:L3, PmCQ5) were isolated from the nasal swabs of calves in Chongqing, China. Bovine P. multocida capsular serotype F strain F (F:L3, PmF) was isolated from the lung of a dead calf that suffered from pneumonia in Mianyang city, Sichuan province, China. Bovine P. multocida capsular serotype B strain B (B:L2, PmB) and porcine P. multocida capsular serotype A strain CVCC1662 (A:L1, PmP) were purchased from the China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control. Rabbit P. multocida capsular serotype A strain R (A:L3, PmR) was isolated from the liver of a dead rabbit in Chongqing, China. Avian P. multocida capsular serotype A strain Q (A:L1, PmQ) was isolated from a dead duck in Chongqing, China. Strains were streaked on Martin medium agar plates (Qingdao Hope Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China), and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. One colony of each strain was inoculated into 5 mL Martin broth and cultured for 12 h at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. E. coli DH5α competent cells were purchased from Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology CO.LTD. Plasmid pUC19oriKanR for mutant construction in P. multocida was constructed in our previous study [22]. E. coli DH5α recombinant strains were screened on plates of Luria–Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL kanamycin. The pMc-Express plasmid was obtained from Dr Sanjie Cao, Sichuan Agricultural University.

Mice

All mouse use was approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Southwest University (Permit number: IACUC-20200803-01). Kunming mice (Female, 6–8-week-old) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China, and mice were fed in IVC system (Individual Ventilated Cages; Suzhou Xinqu Fengqiao Experimental Animal Cage) with free access to water and food under controlled temperature (26 °C).

Phylogenetic analysis of QseC in P. multocida

QseC sequences from P. multocida, E. coli, Pasteurella canis, Pasteurella dagmatis, Pasteurella oralis, and Salmonella enterica et al. in the NCBI Database were downloaded. Four QseC sequences from P. multocida capsular serotype A, B, D, and F (CQ2, B, HN06, F) were aligned pairwise by using NCBI BLAST, and the neighbor-joining phylogenetic analysis of QseC was performed by using MAGA-X software and the circular tree of QseC was made on the website.

Construction of marker-free mutant and complementary strain

Primers used in mutant and complementary strain construction are listed in Table 1. PmCQ2 genomic DNA was extracted by using a bacterial genomic DNA extraction kit (DP302, Tiangen). A 350 bp upstream homologous recombination arm (Up-arm) and a 350 bp downstream homologous recombination arm (Down-arm) of the qseC gene were amplified by PCR, and the PCR fragments were purified using a DNA gel extraction kit (D0056, Beyotime). Up- and Down-arm fragments were linked by using overlap PCR, and then inserted into the Hind III and BamH I sites of pUC19oriKanR using In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (PT5162-1, Clontech) to generate the recombinant plasmid pUC19oriKanR-qseCup+down. Subsequently, the plasmid pUC19oriKanR-qseCup+down was transferred into PmCQ2 competent cell by electroporation and the ΔqseC mutant was selected on Martin agar plate and verified by using PCR. The mutant was serially passaged for 30 generations for genetic stability analysis prior to use. A qseC complementation strain was constructed by using a recombinant gene expression plasmid. Briefly, the egfp gene expression cassette fragment was amplified from plasmid pMc-Express, and inserted into the Hind III and BamH I sites of pUC19oriKanR to generate recombinant plasmid pUC19oriKanR-egfp. The egfp gene was replaced with the qseC gene at the Sal I and Xba I sites of pUC19oriKanR-egfp to generate complementation plasmid pUC19oriKanR-comqseC and then introduced into P. multocida by using electroporation to generate qseC gene complementary strain C-qseC.

Table 1.

PCR primers.

| Primer | Sequence(5’-3’) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| qseC 5’Arm-F | GACCATGATTACGCCAAGCTTTGATTGCACGTTTGCAGGCA | 350 |

| qseC 5’Arm-R | TTTTATATAATTAAGCCATTTCATCATTTT | |

| qseC 3’Arm-F | AATGGCTTAATTATATAAAAGGATTTAGAT | 350 |

| qseC 3’Arm-R | TTTATCGGTACCCGGGGATCCAGCGAGATTATTCTACACCG | |

| dqseC-F | GCAAACAAGTTTACGAGTTC | 1300 |

| dqseC-R | CACATTTTCTAACCGGAATTG | |

| pUC19-F | GAGCGGATAACAATTTCACAC | 151 |

| pUC19-R | ATTTAAGAATACCTTGCCGC | |

| KMT1-F | ATCCGCTATTTACCCAGTGG | 460 |

| KMT1-R | GCTGTAAACGAACTCGCCAC | |

| egfp-F | GACCATGATTACGCCAAGCTTCCGCGCCAACCGATAAAACC | 1111 |

| egfp-R | TTTATCGGTACCCGGGGATCCCAATTCGCCCTATAGTGAGT | |

| comqseC-F | CTAGTGAATTCTGCAGTCGACATGAAATGGCTTAAGCAAAC | 1374 |

| comqseC-R | TGGCCGTCGTTTTACTCTAGATTAAATTTTATTTAATAAAA |

Quantification of capsular polysaccharide

The capsular polysaccharides were measured by using a method as previously described [23]. Briefly, three to four colonies were randomly selected from each strain (PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC), and then inoculated in fresh Martin broth medium and incubated at 37 °C for 8 h with shaking at 200 rpm. The bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 13 200 rpm for 15 min and bacterial pellets were washed twice with PBS and re-suspended in 1 mL PBS. Suspensions were incubated at 42 °C for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 13 200 rpm for 10 min, after which the supernatants were collected. The supernatant (10 μL) of each sample was added to 90 μL capsule staining solution (0.2 mg/mL Stains all, 0.06% glacial acetic acid in 50% formamide), mixed together, and then assayed by measuring absorbance at 640 nm. The standard curve was made by using a hyaluronic acid standard.

Growth curve analysis

Three to four colonies randomly selected from each strain (PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC) were inoculated in 5 ml of Martin broth medium and incubated at 37 °C for 10 h with shaking at 200 rpm. The bacterial cultures were sub-cultured at a dilution of 1:100 into fresh Martin broth medium, respectively, and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cultures were sampled at every 1.5 h after incubation, and the bacterial concentrations (OD600) at each time-point were measured.

Biofilm quantification

Biofilm formation ability was measured by using a crystal violet staining method as previously described [24]. Briefly, overnight bacterial cultures of PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC were diluted with BHI broth medium (1 × 108 CFU/mL), added to 48-well cell culture plates with 400 μL/well, centrifuged at 3800 rpm for 10 min, the negative control was BHI broth with 400 μL/well, incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, respectively. The bacterial culture in each well was drawn off with a syringe. Methanol (200 μL/well) was added into each well for 30 min, then washed 3 times with PBS and dried at room temperature for 1 h. Crystal violet (1%, 200 μL/well) was added into each well for 30 min at 37 °C, then washed 3 times with PBS, and dried at room temperature. Glacial acetic acid (33%, 200 μL/well) was added into each well to dissolve the Crystal violet from the stained biofilm for 30 min at 37 °C. The dissolved crystal violet sample in each well was assayed by measuring absorbance at 630 nm.

Stress resistance assay

The stress-resistances of PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC were investigated using methods as previously described [19]. For oxidative stress assays, bacterial cells were treated with 5 mM, 10 mM or 20 mM H2O2 for 1 h at 37 °C. For hyperosmotic tolerance assays, bacterial cells were treated with 100, 200 or 300 mM NaCl at 37 °C for 1 h. The stress resistances were calculated as the formula (stress-treated bacteria CFU mL−1/ control bacteria CFU mL−1) × 100. In each test, there were three biological repeats and all experiments were conducted independently three times.

Pathogenicity of wild type, mutant and complementary strain

Kunming mice (Female, 6–8-week-old) were divided into three groups and intraperitoneally infected with PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC (3.48 × 105 CFU), respectively. Ten infected-mice in each group were monitored for 7 days for the survival rate calculation. After infection, mice with serious clinical signs (low energy, slow reaction, no eating and drinking, eyes closed and faint breathing) were considered moribund and were euthanized by cervical dislocation. At 8, 16, and 24 h after infection, six mice at each time point were euthanized by cervical dislocation and the lungs were collected for the measurements of bacterial loads. Lungs were also collected at 24 hpi for histopathological examination.

Median lethal dose (LD50) measurement

Female Kunming mice (6–8-week-old) were randomly divided into 8 groups (n = 10/group). Four groups of mice were intraperitoneally infected with 100 µL ΔqseC (dose ranging from 4.46 × 105 to 3.72 × 108 CFU), and other 4 groups of mice were intraperitoneally infected with 100 µL C-qseC (3.8 × 102, 3.8 × 103, 3.8 × 104, 3.8 × 106 CFU). The mice were monitored for 7 days after infection with mice with serious clinical signs (low energy, slow reaction, no eating and drinking, eyes closed, and faint breathing) were considered moribund and were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The number of dead mice was recorded daily, and the LD50 determinations were done by using the Bliss method.

Immune protection assay

Kunming mice (Female, 6–8-week-old) were randomly divided into 45 groups (n = 10 mice/group). The immunization and challenge schedule are listed in Table 2. At day-21 after inoculation, the bloods were collected via the tail vein route, kept at 37 °C for 20 min and then 4 °C overnight for serum separation. Mice were intramuscularly injected with 3.8 × 107 CFU PmCQ1(intramuscular route: LD50 = 3.8 × 102 CFU), 4.8 × 107 CFU PmCQ2 (intramuscular route: LD50 = 3.4 × 103 CFU) [22], 3.6 × 107 CFU PmCQ4 (intramuscular route: LD50 = 2.1 × 103 CFU), 4.5 × 107 CFU PmCQ5 (intramuscular route: LD50 = 4.5 × 103 CFU), 1.0 × 107 CFU PmB (intramuscular route: LD50 = 5.0 × 103 CFU), 2.0 × 108 CFU PmF (intramuscular route: LD50 = 1.0 × 108 CFU), 10 CFU PmP (intramuscular route: LD50 ≈ 1 CFU), 10 CFU PmQ (intramuscular route: LD50 ≈ 1 CFU), and 1.0 × 106 CFU PmR (intramuscular route: LD50 = 1.0 × 104 CFU), respectively. The mice were monitored for 7 days after infection. Mice with serious clinical signs (low energy, slow reaction, no eating and drinking, eyes closed and faint breathing) were considered moribund and were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The number of dead mice was recorded daily, and the protection rates were calculated based on final survival numbers of mice in each group.

Table 2.

Immunization schedule and challenge.

| Groups | Bacterin (CFU/mL) | Primary immune dose (mL) | Booster dose (mL) | Booster day (dpi) | Challenge strain | Challenge day (dpi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live ΔqseC | 4.5 × 107 | 0.1 | PmCQ1, PmCQ2, PmCQ4, PmCQ5, PmB, PmF, PmP, PmQ, and PmR, respectively | 21 | ||

| PBS | 0.1 | PmCQ1, PmCQ2, PmCQ4, PmCQ5, PmB, PmF, PmP, PmQ, and PmR, respectively | 21 | |||

| Inactivated PmCQ2 | 5.0 × 109 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 7 | PmCQ1, PmCQ2, PmCQ4, PmCQ5, PmB, PmF, PmP, PmQ, and PmR, respectively | 21 |

| Inactivated ΔqseC | 5.0 × 109 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 7 | PmCQ1, PmCQ2, PmCQ4, PmCQ5, PmB, PmF, PmP, PmQ, and PmR, respectively | 21 |

| PBS emulsifier | 0.2 | 0.1 | 7 | PmCQ1, PmCQ2, PmCQ4, PmCQ5, PmB, PmF, PmP, PmQ, and PmR, respectively | 21 |

dpi day after primary immunization.

Antibody titer determination

Total bacterial cell proteins of each strain were prepared by using ultrasound pyrolysis and the proteins concentration was measured by using the Bradford method. Each well of 96-well ELISA plates was coated with 1 μg protein in 100 μL carbonate buffer (0.05 M, pH9.0) at 4 °C overnight. The next day, the plates were washed 5 times with PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20), and then treated with blocking buffer (5% skim milk in PBST) at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, the plates were washed 5 times with PBST. The sera were serially diluted in twofold increments in 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The sera from non-immunized mice served as negative controls. After washing, 100 μL of HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (Sigma; diluted at 1: 10 000) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by washing. Then, 100 μL of TMB were added for 10 min (Beyotime biotechnology, China) and stopped by the addition of 2 M H2SO4, before the absorbance quantification at OD450 was done [25]. When the ratio of the positive value (P) of the maximum dilution multiple sera of immunized mice to the negative value (N) of sera of non-immunized mice is greater than 2.1 (P/N > 2.1), the maximum dilution ratio is the serum antibody titer.

Transcriptome analysis

One milliliter of mid-logarithmic phase of PmCQ2 and ΔqseC were seeded in 100 mL Martin broth, respectively, incubated at 37 °C for 6 h with shaking at 200 rpm. The bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Pellets were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and sent to Shanghai Personalbio Technology Co., Ltd. for transcriptome sequencing and analysis (HiSeq, Illumina).

qRT-PCR

Total bacterial RNA was extracted using an RNAprep pure Animal/Cell/Bacteria Kit (TIANGEN, China). RNA concentration was normalized among samples and cDNA synthesis was performed in 20 μL by using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, USA). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed according to a previous study [26] using a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad, USA). Primers used in qRT-PCR are listed in Additional file 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Mouse survival rates were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, while other data analyses were performed using unpaired t-tests. Data were expressed as means ± SD, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis of QseC in Pasteurella multocida

We observed that qseC is present in 264 of the 288 genome-sequenced P. multocida strains (no capsular serotype E strain has been sequenced). To determine the similarity of QseC sequences in P. multocida strains, four QseC sequences from P. multocida capsular serotype A, B, D, and F (CQ2, B, HN06, F) were aligned pairwise by using NCBI BLAST, revealing high identities among QseC sequences in P. multocida serotypes (≥ 98.91% conservation). The phylogenetic analysis of QseC performed by using MEGA-X revealed that QseC from 264 P. multocida belonged to a similar evolutionary branch as compared with that from other bacterial species (Additional file 2).

Construction and characterization of marker-free qseC mutant

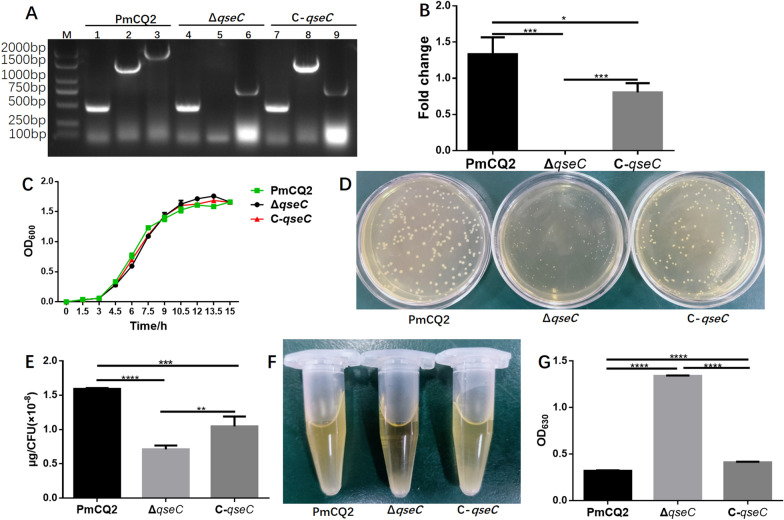

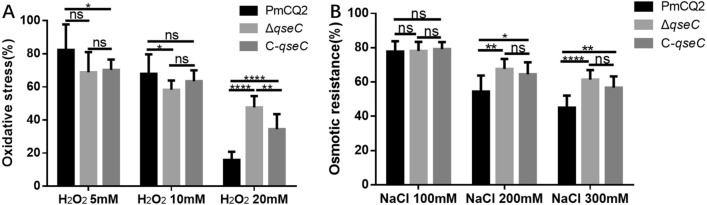

To investigate the role of QseC in P. multocida, we constructed a marker-free qseC mutant (ΔqseC) in the bovine P. multocida capsular serotype A strain CQ2, and a qseC gene complementary strain C-qseC derived from qseC mutant. PCR amplification showed that the qseC gene was not in the chromosome of ΔqseC and C-qseC, but exists in a plasmid in C-qseC (Figure 1A). To further confirm the mutant and complementary strain, RT-PCR was conducted and the results showed that the qseC gene transcripts only exist in the wild type and complementary strain but not in the mutant (Figure 1B). ΔqseC was stable for more than 30 passages (data not shown), and the growth curve was similar to the WT strain (Figure 1C). The colony morphology of ΔqseC was far smaller than that of PmCQ2 and C-qseC (Figure 1D). Considering the similar growth rates among the three strains and the abundant capsular polysaccharide in PmCQ2, the colony size of mutant maybe related to the decrease of the capsular polysaccharide content in cells. The capsular polysaccharides extracted from PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC were detected. Capsular polysaccharide production was significantly reduction in ΔqseC compared with wild type, and followed by C-qseC (Figure 1E). As capsular polysaccharide content also affects the centrifugation status of bacteria, ΔqseC cells were more easy centrifuged to the bottom of tube with clear transparent supernatant (Figure 1F). Capsular polysaccharide production trends in P. multocida capsular serotype A are in opposition to the propensity of strains to produce biofilms [27]. Biofilm quantification detection showed that the biofilm formation in ΔqseC was significantly increased as compared with PmCQ2 and C-qseC (Figure 1G). QseC positively regulates oxidative stress, osmotic pressure, and heat shock resistance in Glaesserella parasuis [19]. However, QseC in P. multocida was involved in the negative regulation of oxidative stress (Figure 2A) and osmotic pressure resistance (Figure 2B), opposite to G. parasuis.

Figure 1.

Construction and characterization of the qseC mutant and complementary strain C-qseC. A PCR confirmation of mutant and complementation strains. M: DNA marker; Lanes1-3: PmCQ2; Lanes 4–6: ΔqseC; Lanes 7–9: C-qseC. Lanes 1, 4, and 7: P. multocida detection by using species-specific primers KMT1-F/KMT1-R (positive control); Lanes 2, 5, and 8: qseC gene detection by using primers comqseC-F /comqseC-R; Lanes 3, 6, and 9: qseC gene detection by using primers qseC5'Arm-F/qseC3'Arm-R. B qseC gene transcripts measured by using qRT-PCR. C Growth curves of strains cultured in Martin broth media at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. D Colony morphology of PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC cultured on Martin agar plates. E Capsular polysaccharide production. F The centrifugally packed state of bacterial cells centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 5 min. G Quantification of biofilm production. Panels B, C: values are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3. Panels E, G: values are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 5. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001; ns means not significant.

Figure 2.

Stress tolerance analyses. A The bacterial cells were treated with 5 mM, 10 mM, or 20 mM H2O2 for 1 h at 37 °C. B The bacterial cells were exposed to 100 mM, 200 mM and 300 mM NaCl for 1 h at 37 °C. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 9. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001; ns means not significant.

Role of QseC in P. multocida virulence

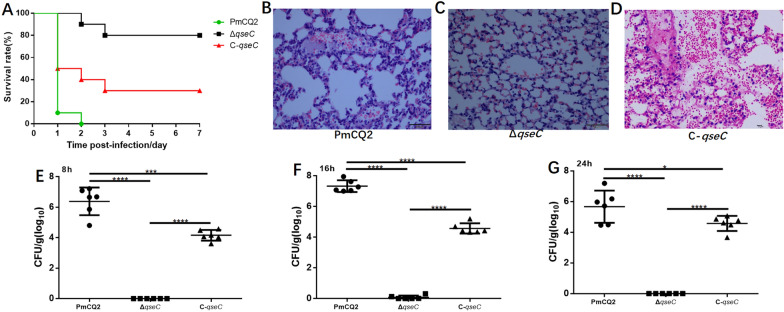

QseC can regulate virulence in many bacterial pathogens. To investigated its effect on the virulence in P. multocida, mice were injected with PmCQ2, ΔqseC, and C-qseC (3.48 × 105 CFU), respectively. The survival rate of mice infected with ΔqseC was significantly higher than that of mice infected with PmCQ2 or C-qseC (Figure 3A). Compared with WT and C-qseC, the qseC mutant induced a weak inflammatory response in lung of mice (Figures 3B and C), and the bacterial loads in the lungs of mice infected with qseC mutant were significantly lower than that in PmCQ2 and C-qseC infection (Figures 3D–F). To further quantify the decrease of virulence in qseC mutant, 50% lethal dose assays were conducted. The LD50 of ΔqseC via intraperitoneal route was 5.28 × 107 CFU, which was 5.28 × 107 fold higher than that of PmCQ2 (intraperitoneal route: LD50 ≈ 1 CFU) [28], and 2.1 × 103 fold higher than that of C-qseC (intraperitoneal route: LD50 = 2.48 × 104 CFU) (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Pathogenicity analyses. A Survival rates of mice infected with wild strain PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC, respectively, n = 10 mice/group. B–D Histopathology in lung of mice 24 h after infection with PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC, respectively. B Serious dilation and congestion in veins and alveolar wall capillaries, with inflammatory cell infiltration; C Slight dilation and congestion in alveolar wall capillaries, with a small number of red blood cells in some alveolar cavities; D Hyperemia and bleeding, with large number of red blood cells and cellulose exudation in the alveolar cavity. E–G Bacterial loads in the mice lungs at 8, 16, and 24 h after infection with PmCQ2, ΔqseC and C-qseC, respectively. Panels B–G: values are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6. * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001.

Table 3.

LD50 calculations.

| ΔqseC | Infection dose (CFU) | 3.72 × 108 | 4.46 × 107 | 4.46 × 106 | 4.46 × 104 |

| Death/Total mice | 9/10 | 3/10 | 1/10 | 2/10 | |

| LD50 = 5.28 × 107 CFU | |||||

| C-qseC | Infection dose (CFU) | 3.80 × 106 | 3.80 × 104 | 3.80 × 103 | 3.80 × 102 |

| Death/Total mice | 9/10 | 6/10 | 4/10 | 0/10 | |

| LD50 = 2.48 × 104 CFU | |||||

QseC regulates P. multocida gene expression

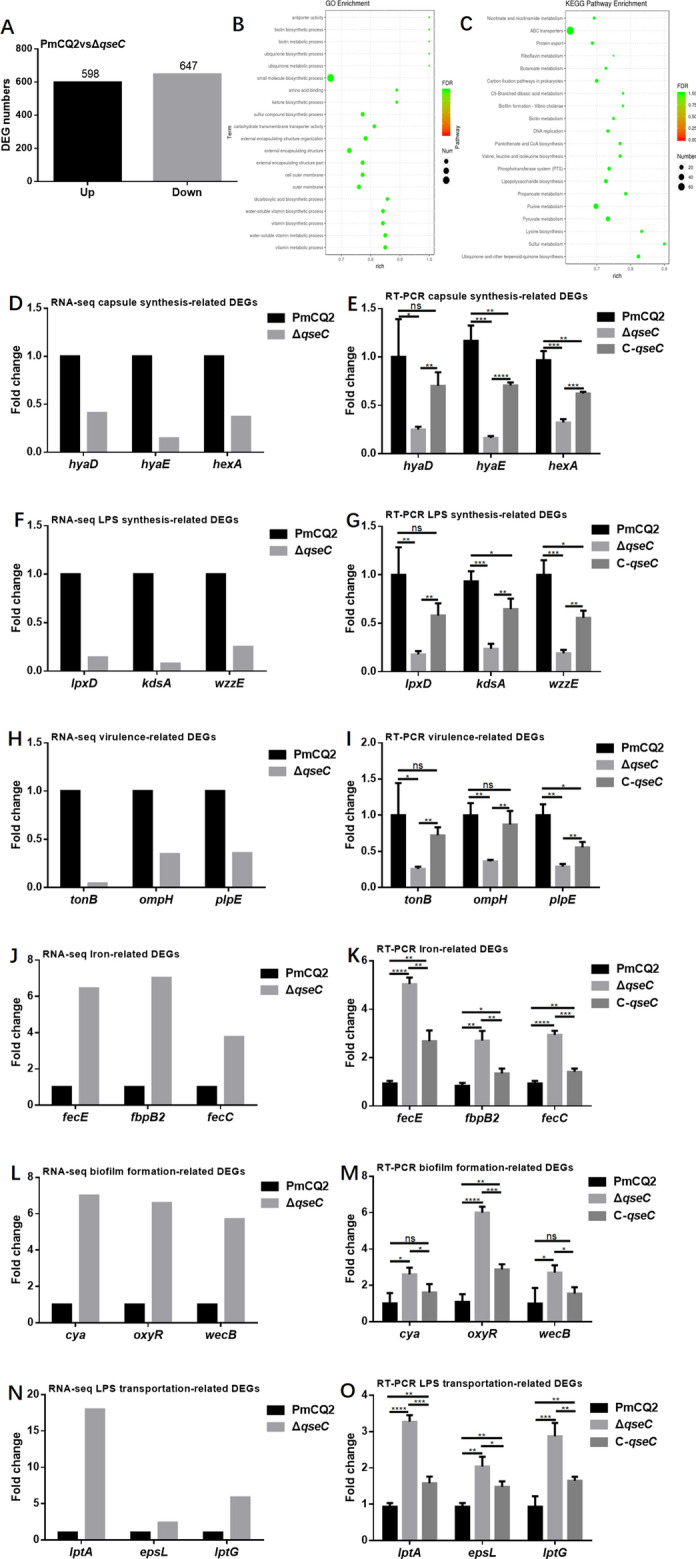

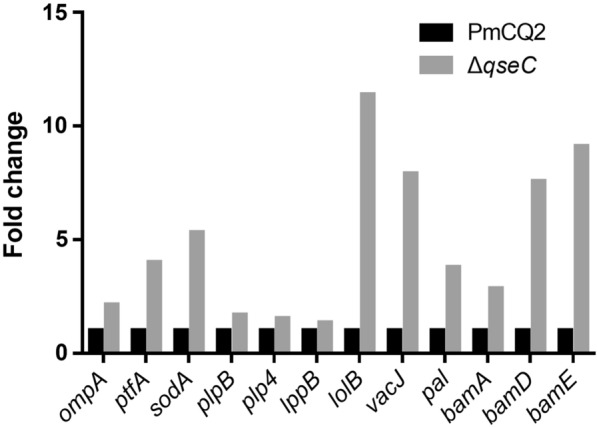

We next conducted transcriptome sequencing of wild-type strain and ΔqseC strain (NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database accession numbers are PRJNA629381 and PRJNA687922). A total of 1245 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PmCQ2 and ΔqseC (Fold change ≥ 1.5) were annotated (Figure 4A). GO and KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that the top DEGs are involved in outer membrane, ABC transporters, biofilm formation, lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, and amino acid biosynthesis (Figures 4B and C). Consistent with changes in biological characteristics, genes for capsule synthesis (Figures 4D and E), LPS synthesis (Figures 4F and G) and virulence (Figures 4H and I) were significantly down-regulated in ΔqseC. However, most genes involved in iron utilization/transport (Figures 4J and K), biofilm formation (Figures 4L and M), LPS transport (Figures 4N and O) and immune protection (Figure 5) were significantly up-regulated.

Figure 4.

Transcriptome analysis of wild-type PmCQ2 and ΔqseC in vitro. A The up/down-regulated DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) of PmCQ2 and ΔqseC in vitro. B, C GO and KEGG pathway analysis of PmCQ2 and ΔqseC. D, E Capsular synthesis-related DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) in RNA-seq and in RT-PCR (n = 3). F, G LPS synthesis related DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) in RNA-seq and in RT-PCR (n = 3). H, I Virulence-related DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) in RNA-seq and in RT-PCR (n = 3). J, K Iron-related DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) in RNA-seq and in RT-PCR (n = 3). L, M Biofilm formation-related DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) in RNA-seq and in RT-PCR (n = 3). N, O LPS transportation-related DEGs (FC ≥ 1.5) in RNA-seq and in RT-PCR (n = 3). Panels (E, G, I, K, M, O) were pooled from three independent experiments with 3 replicates per group and analyzed with multiple comparative analysis. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001; ns means not significant.

Figure 5.

Significantly up-regulated genes encoding for immuno-protection in ΔqseC based on transcriptome sequencing.

ΔqseC stimulates a stronger antibody response

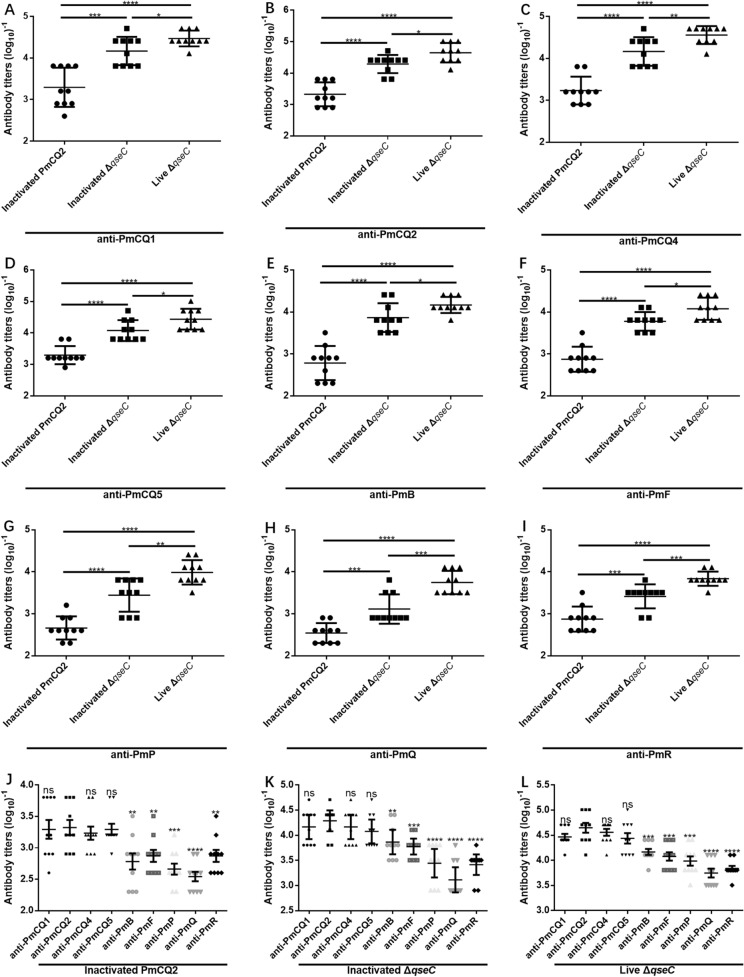

To explore the effect of qseC deletion on antibody production, the serum IgG titers of the mice immunized with inactivated PmCQ2, inactivated ΔqseC and live ΔqseC were measured by using ELISA. The antibody titers of ΔqseC were significantly higher than that of PmCQ2 (Figures 6A–I), and compared with inactivated PmCQ2 and inactivated ΔqseC, the live ΔqseC immunization generated much higher antibody levels against P. multocida strains of broad serotype (Figures 6A–I). The titers of serum antibody in immunized mice that against bovine capsular serotype A strains were significantly higher than that against bovine capsular serotype B and F and other animal P. multocida capsular serotype A strains (Figures 6J–L). The results indicate that live ΔqseC can induce much higher cross-reactive antibodies than inactivated PmCQ2 and inactivated ΔqseC.

Figure 6.

Serum IgG antibody titers. Mice were immunized with inactivated PmCQ2, inactivated ΔqseC and live ΔqseC, respectively. Blood was collected via the tail vein route at 21-day after immunization for serum isolation. The serum antibodies against A PmCQ1, B PmCQ2, C PmCQ4, D PmCQ5, E PmB, F PmF, G PmP, H PmQ, I PmR were detected. The IgG antibody titers of mice immunized with J inactivated PmCQ2, K inactivated ΔqseC, L live ΔqseC that against different P. multocida strains were analyzed. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 10 mice/group. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001; ns means no significant.

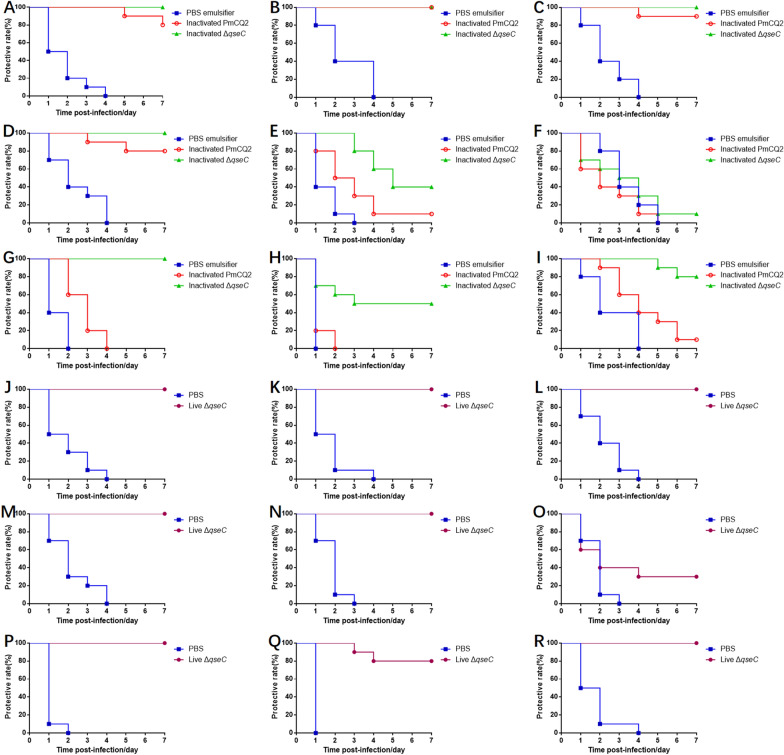

ΔqseC cross-protects against other serotypes

The cross-protection of ΔqseC against other P. multocida serotypes were investigated. Kunming mice were intramuscularly inoculated with live ΔqseC, inactivated ΔqseC and inactivated PmCQ2, respectively. At day-21 after primary immunization, mice were challenged with 9 strains of P. multocida, respectively (Table 2). Live and inactivated ΔqseC both presented strong cross-protection to mice against multiple P. multocida strains (Figures 7A–R). However, inactivated PmCQ2 presented no cross-protection to mice against bovine P. multocida serotypes B and F, and rabbit, avian and porcine P. multocida serotype A (Figures 7G–I). Immunization with live ΔqseC presented 100% protection to mice against infection by bovine P. multocida capsular serotype A (Figures 7J–M) and serotype B (Figure 7N), porcine P. multocida capsular serotype A (Figure 7P) and rabbit P. multocida capsular serotype A (Figure 7R). However, live ΔqseC only presented 30% protection to bovine P. multocida capsular serotype F infection (Figure 7O), and 80% protection to avian P. multocida capsular serotype A infection (Figure 7Q). Even though inactivated ΔqseC also presented a good cross-protection, the live ΔqseC showed better (Figures 7A–R). The results indicate that live ΔqseC has potential to develop as an attenuated vaccine against infection by P. multocida strains of homologous and heterologous serotypes.

Figure 7.

Immune protection against P. multocida serotypes induced by live ΔqseC, inactivated PmCQ2 and inactivated ΔqseC, respectively. The survival rates of mice subcutaneously immunized with inactivated PmCQ2, inactivated ΔqseC, and PBS emulsifier and intramuscularly challenged with A PmCQ1, B PmCQ2, C PmCQ4, D PmCQ5, E PmB, F PmF, G PmP, H PmQ, and I PmR, respectively. The survival rates of mice intramuscularly immunized with live ΔqseC and PBS for 21 days and intramuscularly challenged with J PmCQ1, K PmCQ2, L PmCQ4, M PmCQ5, N PmB, O PmF, P PmP, Q PmQ, and R PmR, respectively.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that QseC regulates capsular production, biofilm formation, stress resistance, and virulence in P. multocida, consistent with previous reports for other bacterial pathogens. We also showed that deleting qseC might provide a means by which to develop a cross-protective P. multocida vaccine.

At present, a few commercial P. multocida vaccines provide limited immune protection to domestic animals against infection by P. multocida of homologous serotypes [29]. The lack of a universal vaccine has brought challenges to prevent P. multocida infections. Although antibiotics can be used to control P. multocida, however, with the extensive use of antibiotics, many strains are now drug-resistant [30]. The previous studies in the discovery of cross protective antigens such as PlpB [31], PlpE [32] and PmCQ2_2g0128 [33] in P. multocida provides a basis for the research of cross-protective vaccine against P. multocida.

Deletion of the aroA gene in P. multocide P-1059 strain (serotype A:3) promoted strain cross-protection against infection by P. multocide serotype A:1 or A:4 [20], which in part motivated this study. We speculated that the absence of QseC in P. multocida could also lead to the down-regulation of virulence and promote the cross-immune protection characteristics of strains.

QseC belongs to the QseBC quorum sensing system, which regulates virulence gene expression in many pathogenic bacteria [34, 35]. As one of two-component regulators, QseC can activate the downstream receptor QscB to facilitate the expression of associated genes. We observed that the expression of qseB was promoted by deleting qseC (Additional file 3). There are two potential transcriptional start sites in the qseBC promoter [12]; deleting qseC abolishes only the first transcription initiation site. The absence of QseC in E. coli leads to activation of QseB by a sensor kinase PmrB [36]. In P. multocida, there may also exist a sensor like PmrB to activate QseB in the absence of QseC.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that qseC deletion in bacteria can regulate strain cross immune protection. Recombinant QseC can induce host innate immunity, which may reduce the virulence gene expression of avian pathogenic E. coli [37], suggesting QseC has potential as a vaccine candidate against bacterial pathogen infections. The development of vaccine combined with rQseC and qseC mutant infection may be a next research orientation.

In the present study, deleting qseC resulted in a significant decrease in the production of capsular polysaccharides; however, transcriptome analysis showed that the expression levels of only a few genes related to capsular polysaccharide synthesis were down-regulated, while the expression of most genes were significantly up-regulated. Although some reports suggest that the presence of the capsule can mask the relevant immune antigens, thus affecting antigen presentation, it does not mean the absence of capsule will certainly enhance the induction of immune protection by the strain. Deleting cexA or bcbH can lead to capsule loss of P. multocida, but the immune protection characteristics of the deletion strains were significantly different [38]. We observed a similar phenotype in studies of a Pm0442 deletion [22]. Therefore, the capsule deficiency in P. multocida is likely not the key to increased immune protection in strains.

The serum antibody titers of mice immunized with ΔqseC were significantly higher than after immunization with the wild type strain. We speculate that there may be some cross-protective antigens up-regulated in ΔqseC. Transcriptome sequence showed that many genes encoding outer membrane proteins (plpB, plp4, lppB, lolB, vacJ, pal, bamA, bamD, and bamE) were up-regulated (Figure 4); some of these genes are associated with immune protection or cross-protection in pathogens [31, 39–41]. Even though the general virulence was decreased in ΔqseC, we also found that the expression of some virulence-related genes such as ompA, ptfA, and sodA were up-regulated.

In summary, our study demonstrates that QseC mediates capsule production, biofilm formation, resistance to environmental stress, and virulence in P. multocida. Deleting qseC promotes P. multocida cross- immune protection against infection by P. multocida strains of homologous and heterologous serotypes.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Phylogenetic tree constructed based on the complete QseC amino acid sequences. The phylogenetic tree of QseC was constructed by employing the Neighbor-Joining method in MEGA X. The complete QseC amino acid sequences from 264 strains of Pasteurella multocida, 2 strains of Salmonella enterica, 2 strains of Escherichia coli, and 1 strain of following bacteria including Pasteurella canis, Pasteurella dagmatis, Pasteurella oralis, Pasteurella aerogenes, Moraxella sp., Frederiksenia canicola, Necropsobacter massiliensis, Caviibacterium falvescens, Haemophilus felis, were obtained from GenBank.

Additional file 3: Relative expression of qseB in PmCQ2 and ΔqseC. Overnight cultured PmCQ2 (1 × 108 CFU) and ΔqseC (1 × 10 8 CFU) were inoculated into 5 mL Martin broth medium, respectively, incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Bacterial cells were collected at 3, 6, and 9 h for RNA extraction, A-C qseB gene expression in PmCQ2 and ΔqseC. Panels (A-C): all values are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 5. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Paul R. Langford and Dr Sanjie Cao for kindly providing the plasmid pMc-Express.

Abbreviations

- Qse

Quorum sensing

- Omp

Outer membrane protein

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- AHL

Acyl-homoserine lactone

- AI-2

Autoinducers 2

- AI-3

Autoinducers 3

Authors’ contributions

NZL and YYP conceived and designed research. YY, PH, LXG, TL, and XY conducted experiments. NZL, YY, PL, and FH analyzed data. NZL, PRH, and YYP wrote or helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing [cstc2017jcyjAX0288] and China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA [CARS-37].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. The use of animals in the present study was approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Southwest University (permit number: IACUC-20200803-01). All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuanyi Peng, Email: pyy2002@sina.com.

Nengzhang Li, Email: lich2001020@163.com.

References

- 1.Cid D, Garcia-Alvarez A, Dominguez L, Fernandez-Garayzabal JF, Vela AI. Pasteurella multocida isolates associated with ovine pneumonia are toxigenic. Vet Microbiol. 2019;232:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter GR. Studies on Pasteurella multocida. I. A hemagglutination test for the identification of serological types. Am J Vet Res. 1955;16:481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper M, John M, Turni C, Edmunds M, St Michael F, Adler B, Blackall PJ, Cox AD, Boyce JD. Development of a rapid multiplex PCR assay to genotype Pasteurella multocida strains by use of the lipopolysaccharide outer core biosynthesis locus. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:477–485. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02824-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai YC, Shien JH, Wu JR, Shieh HK, Chang PC. Polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the genes involved in the biosynthesis of the lipopolysaccharide of Pasteurella multocida. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23:543–546. doi: 10.1177/1040638711404145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang B, Ku X, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Chen G, Chen F, Zeng W, Li J, Zhu L, He Q. The AI-2/luxS quorum sensing system affects the growth characteristics, biofilm formation, and virulence of Haemophilus parasuis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:62. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lixa C, Mujo A, Anobom CD, Pinheiro AS. A structural perspective on the mechanisms of quorum sensing activation in bacteria. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2015;87:2189–2203. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201520140482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a012427. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonioli L, Blandizzi C, Pacher P, Guilliams M, Hasko G. Rethinking Communication in the immune system: the quorum sensing concept. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis MM, Russell R, Moreira CG, Adebesin AM, Wang C, Williams NS, Taussig R, Stewart D, Zimmern P, Lu B, Prasad RN, Zhu C, Rasko DA, Huntley JF, Falck JR, Sperandio V. QseC inhibitors as an antivirulence approach for Gram-negative pathogens. MBio. 2014;5:e02165. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02165-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaur G, Balamurugan P, Princy SA. Inhibition of the quorum sensing system (ComDE pathway) by aromatic 1,3-di-m-tolylurea (DMTU): cariostatic effect with fluoride in wistar rats. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:313. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Q, Zou PZ, Cao Z, Wang QY, Fu SZ, Xie GS, Huang J. QseC Inhibition as a novel antivirulence strategy for the prevention of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND)-causing Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front Cell Infect Mi. 2021;10:594652. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.594652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke MB, Hughes DT, Zhu C, Boedeker EC, Sperandio V. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10420–10425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604343103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reading NC, Rasko DA, Torres AG, Sperandio V. The two-component system QseEF and the membrane protein QseG link adrenergic and stress sensing to bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5889–5894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811409106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes DT, Clarke MB, Yamamoto K, Rasko DA, Sperandio V. The QseC adrenergic signaling cascade in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000553. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Njoroge JW, Nguyen Y, Curtis MM, Moreira CG, Sperandio V. Virulence meets metabolism: Cra and KdpE gene regulation in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. MBio. 2012;3:e00280–e312. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00280-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyte M, Vulchanova L, Brown DR. Stress at the intestinal surface: catecholamines and mucosa-bacteria interactions. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kostakioti M, Hadjifrangiskou M, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ. QseC-mediated dephosphorylation of QseB is required for expression of genes associated with virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:1020–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadjifrangiskou M, Kostakioti M, Chen SL, Henderson JP, Greene SE, Hultgren SJ. A central metabolic circuit controlled by QseC in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:1516–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He L, Dai K, Wen X, Ding L, Cao S, Huang X, Wu R, Zhao Q, Huang Y, Yan Q, Ma X, Han X, Wen Y. QseC mediates osmotic stress resistance and biofilm formation in Haemophilus parasuis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:212. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Homchampa P, Strugnell RA, Adler B. Cross protective immunity conferred by a marker-free aroA mutant of Pasteurella multocida. Vaccine. 1997;15:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitobe J, Sinha R, Mitra S, Nag D, Saito N, Shimuta K, Koizumi N, Koley H. An attenuated Shigella mutant lacking the RNA-binding protein Hfq provides cross-protection against Shigella strains of broad serotype. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He F, Qin X, Xu N, Li P, Wu X, Duan L, Du Y, Fang R, Hardwidge PR, Li N, Peng Y. Pasteurella multocida Pm0442 affects virulence gene expression and targets TLR2 to induce inflammatory responses. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1972. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung JY, Wilkie I, Boyce JD, Townsend KM, Frost AJ, Ghoddusi M, Adler B. Role of capsule in the pathogenesis of fowl cholera caused by Pasteurella multocida serogroup A. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2487–2492. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2487-2492.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang JC, Wang XR, Cao Q, Feng FF, Xu XJ, Cai XW. ClpP participates in stress tolerance and negatively regulates biofilm formation in Haemophilus parasuis. Vet Microbiol. 2016;182:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afshari H, Maleki M, Hakimian M, Tanha RA, Salouti M. Immunogenicity evaluating of the SLNs-alginate conjugate against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Immunol Methods. 2021;488:112938. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2020.112938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li N, Long Q, Du H, Zhang J, Pan T, Wu C, Lei G, Peng Y, Hardwidge PR. High and low-virulent bovine Pasteurella multocida capsular type A isolates exhibit different virulence gene expression patterns in vitro and in vivo. Vet Microbiol. 2016;196:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petruzzi B, Briggs RE, Swords WE, De Castro C, Molinaro A, Inzana TJ. Capsular polysaccharide interferes with biofilm formation by Pasteurella multocida serogroup A. MBio. 2017;8:e01843–e1917. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01843-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li N, Feng T, Wang Y, Li P, Yin Y, Zhao Z, Hardwidge PR, Peng Y, He F. A single point mutation in the hyaC gene affects Pasteurella multocida serovar A capsule production and virulence. Microb Pathog. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Hasani K, Boyce J, McCarl VP, Bottomley S, Wilkie I, Adler B. Identification of novel immunogens in Pasteurella multocida. Microb Cell Fact. 2007;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vu-Khac H, Trinh TTH, Nguyen TTG, Nguyen XT, Nguyen TT. Prevalence of virulence factor, antibiotic resistance, and serotype genes of Pasteurella multocida strains isolated from pigs in Vietnam. Vet World. 2020;13:896–904. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.896-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabatabai LB, Zehr ES. Identification of five outer membrane-associated proteins among cross-protective factor proteins of Pasteurella multocida. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1195–1198. doi: 10.1128/Iai.72.2.1195-1198.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu JR, Shien JH, Shieh HK, Chen CF, Chang PC. Protective immunity conferred by recombinant Pasteurella multocida lipoprotein E (PlpE) Vaccine. 2007;25:4140–4148. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du H, Wu C, Li C, Fang R, Ma J, Ji J, Li Z, Li N, Peng Y, Zhou Z. Two novel crossprotective antigens for bovine Pasteurella multocida. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:4627–4633. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma VK, Casey TA. Escherichia coli O157:H7 lacking the qseBC-encoded quorum-sensing system outcompetes the parental strain in colonization of cattle intestines. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1882–1892. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03198-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Hu L, Xu Z, Tan C, Yuan F, Fu S, Cheng H, Chen H, Bei W. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae two-component system QseB/QseC regulates the transcription of PilM, an important determinant of bacterial adherence and virulence. Vet Microbiol. 2015;177:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guckes KR, Kostakioti M, Breland EJ, Gu AP, Shaffer CL, Martinez CR, 3rd, Hultgren SJ, Hadjifrangiskou M. Strong cross-system interactions drive the activation of the QseB response regulator in the absence of its cognate sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16592–16597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315320110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhari AA, Kariyawasam S. Innate immunity to recombinant QseC, a bacterial adrenergic receptor, may regulate expression of virulence genes of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Vet Microbiol. 2014;171:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyce JD, Adler B. Acapsular Pasteurella multocida B:2 can stimulate protective immunity against pasteurellosis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1943–1946. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1943-1946.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohanty NN, Yogisharadhya R, Shivachandra SB. Immunogenicity of recombinant outer membrane protein (OmpW) of Pasteurella multocida serogroup B:2 in mouse model. Indian J Anim Sci. 2019;89:1073–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei X, Wang Y, Luo R, Qian W, Sizhu S, Zhou H. Identification and characterization of a protective antigen, PlpB of bovine Pasteurella multocida strain LZ-PM. Dev Comp Immunol. 2017;71:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shivachandra SB, Kumar A, Yogisharadhya R, Viswas KN. Immunogenicity of highly conserved recombinant VacJ outer membrane lipoprotein of Pasteurella multocida. Vaccine. 2014;32:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2: Phylogenetic tree constructed based on the complete QseC amino acid sequences. The phylogenetic tree of QseC was constructed by employing the Neighbor-Joining method in MEGA X. The complete QseC amino acid sequences from 264 strains of Pasteurella multocida, 2 strains of Salmonella enterica, 2 strains of Escherichia coli, and 1 strain of following bacteria including Pasteurella canis, Pasteurella dagmatis, Pasteurella oralis, Pasteurella aerogenes, Moraxella sp., Frederiksenia canicola, Necropsobacter massiliensis, Caviibacterium falvescens, Haemophilus felis, were obtained from GenBank.

Additional file 3: Relative expression of qseB in PmCQ2 and ΔqseC. Overnight cultured PmCQ2 (1 × 108 CFU) and ΔqseC (1 × 10 8 CFU) were inoculated into 5 mL Martin broth medium, respectively, incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Bacterial cells were collected at 3, 6, and 9 h for RNA extraction, A-C qseB gene expression in PmCQ2 and ΔqseC. Panels (A-C): all values are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 5. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.