Abstract

Individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) and sickle cell trait (SCT) have many risk factors that could make them more susceptible to COVID-19 critical illness and death compared to the general population. With a growing body of literature in this field, a comprehensive review is needed. We reviewed 71 COVID-19-related studies conducted in 15 countries and published between January 1, 2020, and October 15, 2021, including a combined total of over 2000 patients with SCD and nearly 2000 patients with SCT. Adults with SCD typically have a mild to moderate COVID-19 disease course, but also a 2- to 7-fold increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization and a 1.2-fold increased risk of COVID-19-related death as compared to adults without SCD, but not compared to controls with similar comorbidities and end-organ damage. There is some evidence that persons with SCT have increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization and death although more studies with risk-stratification and properly matched controls are needed to confirm these findings. While the literature suggests that most children with SCD and COVID-19 have mild disease and low risk of death, some children with SCD, especially those with SCD-related comorbidities, are more likely to be hospitalized and require escalated care than children without SCD. However, children with SCD are less likely to experience COVID-19-related severe illness and death compared to adults with or without SCD. SCD-directed therapies such as transfusion and hydroxyurea may be associated with better COVID-19 outcomes, but prospective studies are needed for confirmation. While some studies have reported favorable short-term outcomes for COVID-19 patients with SCD and SCT, the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection are unknown and may affect individuals with SCD and SCT differently from the general population. Important focus areas for future research should include multi-center studies with larger sample sizes, assessment of hemoglobin genotype and SCD-modifying therapies on COVID-19 outcomes, inclusion of case-matched controls that account for the unique sample characteristics of SCD and SCT populations, and longitudinal assessment of post-COVID-19 symptoms.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Sickle cell disease, Sickle cell trait, Hemoglobinopathies, Red blood cell disorder

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [[1], [2], [3]] is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which has impacted millions of people around the world and caused unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems. Severe COVID-19 clinical manifestations include acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), systemic inflammation, sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death, among others [[1], [2], [3]]. Survivors of SARS-CoV-2 infection may experience lingering symptoms and long-term health problems [4].

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited red blood cell disorder caused by a single amino acid genetic mutation in the beta-chain of the human hemoglobin protein [5,6]. Patients with SCD experience chronic hemolytic anemia, recurrent vascular occlusion, insidious vital organ deterioration, early mortality, and poor quality of life [5,6]. Repeated vaso-occlusive events may result in functional asplenia and immune deficiency in early childhood leading to life-long increased susceptibility to serious bacterial infections. Acute and chronic pain and other serious health conditions such as acute chest syndrome (ACS) and stroke [7] are also common in patients with SCD. SCD predominantly affects Black individuals. In the United States, there are about 100,000 people living with SCD, with 1 in 500 African Americans being affected by the disease [8].

Individuals with sickle cell trait (SCT) may also exhibit adverse health effects including exertional rhabdomyolysis, pulmonary embolism, splenic infarction, and renal damage [9,10]. Approximately 300 million people worldwide and 1 to 3 million in the United States (8% to 10% of African Americans) live with SCT [[10], [11], [12]].

There is conflicting evidence whether patients with SCD or SCT experience more severe COVID-19 disease, with higher morbidity and mortality rate than the general population. SCD pathophysiology results in chronic anemia, endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, immunocompromised status, and hypercoagulability, all of which have been identified as risk factors for worse COVID-19 outcomes [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Individuals with SCT do have a hypercoagulable state and sickling pathophysiology in hypoxic environments such as the renal medulla and could potentially be at higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes as well.

In this paper, we present a comprehensive review of the literature of COVID-19 patients with SCD and SCT and highlight both the conclusions and limitations drawn from the literature, which can serve as important considerations for future research. We also discuss clinical course, hospitalization trends, mortality, risk factors, and SCD-disease modifying therapies among children and adults (separately) with SCD and SCT (separately) who have COVID-19 disease.

2. Methods

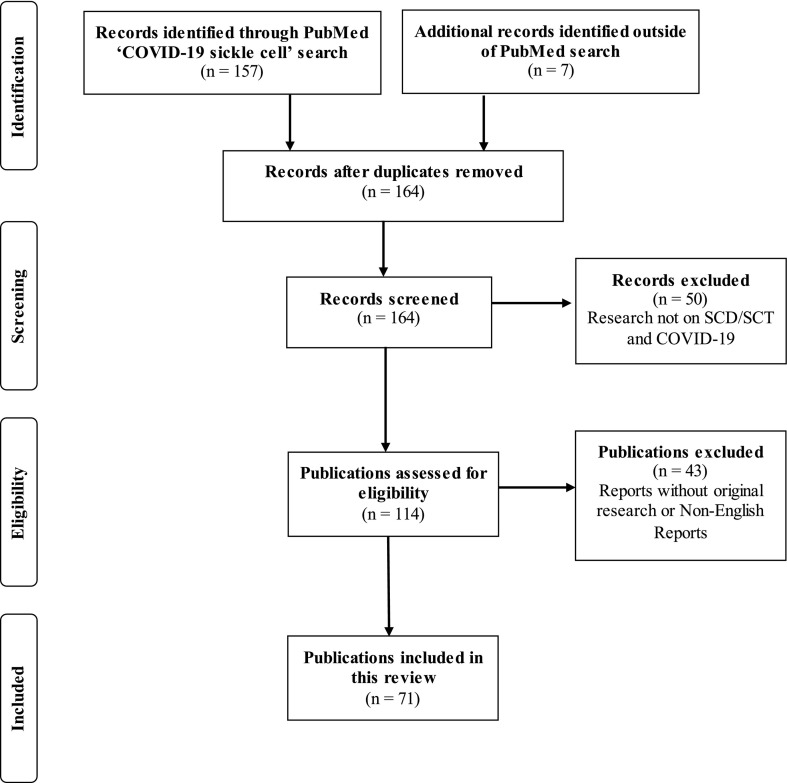

A structured literature search was conducted using PubMed to include all relevant articles that were dated between January 1, 2020, and October 15, 2021. The selection process is detailed in Fig. 1 . The review was conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist [17]. Titles and abstracts were searched to identify the literature related to COVID-19 and SCD/SCT. The primary search term used was ‘COVID-19 sickle cell’ which yielded 157 articles. Additional references were retrieved from the bibliographies of the articles identified by the primary search. Of the original 164 records screened, 50 were excluded because they were unrelated to SCD and COVID-19, and 43 were excluded because they were not available in English or did not include original clinical data on SCD or SCT patients with positive or suspected COVID-19. After this filter, a total of 71 publications were retained and systematically reviewed.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart used to identify original research articles on COVID-19 patients with sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait.

2.1. Statistical analysis

In this systematic review, we used descriptive statistics to summarize aggregated demographic and clinical data of SCD and SCT patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection based on the literature included in this review (Table 1 ), including median and interquartile range for age, vitals, and laboratory values. The categorical variables female sex, hemoglobin genotype, and comorbidities were described as n (% of the sample). The overall mortality rate for SCD/non-SCD was calculated as the total number of COVID-19-related deaths among SCD/non-SCD patients reported in observational cohort studies divided by the total number of SCD/non-SCD patients with COVID-19 reported by the same studies. Relative risk of death for SCD was estimated as the absolute risk in the SCD group divided by the absolute risk in the non-SCD group.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of all COVID-19 patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) or sickle cell trait (SCT) based on aggregated data from the literature included in this review.

| SCD n = 2290 |

n | SCT n = 1937 |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 25 (17–39) | 140 | 54 (40–61) | 24 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 1041 (56) | 1858 | 319 (54) | 591 |

| HbSS genotype, n (%) | 171 (62) | 278 | n/a | n/a |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 1025 | 563 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 28 (3) | 38 (7) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 107 (10) | 67 (12) | ||

| Asthma or COPD | 113 (11) | 170 (30) | ||

| Diabetes | 50 (5) | 137 (23) | ||

| Heart failure | 46 (5) | 46 (8) | ||

| Hypertension | 149 (15) | 237 (42) | ||

| Liver disease | 31 (3) | 34 (6) | ||

| Stroke | 100 (10) | 15 (3) | ||

| Vitals, median (IQR) | ||||

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 95 (88–97) | 70 | 96 (91–98) | 16 |

| Body temperature (F) | 101.6 (100.4–102.3) | 44 | 100.3 (98.7–101.6) | 15 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28 (25–34) | 30 | 32 (27–35) | 18 |

| Laboratory Values, median (IQR) | ||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 732 (495–917) | 47 | 392 (292–576) | 10 |

| Lymphocytes (x109/L) | 2.3 (1.2–4.4) | 70 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 13 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.7 (0.9–4.3) | 36 | 0.5 (0.4–1.1) | 11 |

| White blood cell count (x109/L) | 13 (8.3–18.2) | 75 | 8.8 (5–13.3) | 16 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.0 (6.7–9.6) | 100 | 11.4 (9.8–13) | 16 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 6.3 (0.9–18.7) | 72 | 9.9 (2.2–20.5) | 10 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 3.3 (0.8–7.7) | 50 | 1.3 (2.7–21.5) | 8 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range.

3. Patients with COVID-19 and sickle cell disease

Of the 71 reports identified in this review, 67 studies (25 observational cohort studies and 42 case studies) reported on SCD patients describing a combined total of 2290 patients with SCD and COVID-19. A detailed summary of study parameters and main study findings are presented in Table 2 (observational studies) and Table 3 (case studies).

Table 2.

Observational cohort studies of patients with SCD and COVID-19. Authors listed in alphabetical order.

| Authors | Country | Sample size n (M/F) |

Age (years) | Hb genotype (n) | SCD therapy (n) | Control group | Main findings | SCD |

Non-SCD |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hosp. rate n (%) |

Mort. rate n (%) |

Hosp. rate n (%) |

Mort. rate n (%) |

||||||||

| AbdulRahman et al. [25] | Bahrain | 38 (11/27) | 36 | n/a | n/a | COVID-19 w/o SCD | SCD is not a risk factor for worse COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized pts. compared to non-SCD pts. hospitalized with COVID-19. | n/a | 1 (2.6) | n/a | 58 (3.3) |

| Alhumaid et al. [34]1 | Saudi Arabia | 31 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | n/a | None | 14 of 31 SCD pts. with COVID-19 required admission to the ICU. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Alkindi et al. [26] | Oman | 50 (27/23) | 31 | HbSS (10), HbSβ0 (29), Unknown (11) |

BT (26) | SCD w/o COVID-19 | Although COVID-19 may trigger VOC onset, it does not increase mortality compared to non-COVID-19 pts. with VOC. | 34 (68) | 2 (4) | 47 (70)2 | 3 (6) |

| Al Yazidi et al. [64]1 | Oman | 7 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | BT (2) | None | SCD is the most common comorbidity associated with COVID-19 pediatric admission. Children with SCD and COVID-19 are more susceptible to complications. | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Arlet et al. [27] | France | 83 (38/45) | 30 | HbSS or HbSβ0 (71), HbSC (8), HbSβ+ (4) |

HU (38), BT (31) | COVID-19 w/o SCD | SCD pts. did not have increased risk of morbidity or mortality; VOC complicates infection; Older pts. are at higher risk and should be monitored carefully. | n/a | 2 (2) | n/a | 2891 (7) |

| Balanchivadze et al. [28] | USA | 6 (3/3) | 38 | HbSS (4), HbSC (1), HbSβ+ (1) |

BT (2) | None | SCD pts. generally had mild disease course with lower chances of intubation, ICU admission, and death. | 4 (67) | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Boğa et al. [37] | Turkey | 39 (17/22) | 35 | HbSS (23), HbSβ+ (15), HbSE (1) | HU (25), BT (8) | COVID-19 w/o SCD | SCD pts. had more severe disease course (pneumonia, hosp., intubation) than non-SCD healthcare professionals. | 10 (26) | 2 (5) | 9 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Brousse et al. [70] | France | 39 (n/a) | 12 | HbSS (35), HbSC (3), HbSβ+ (1) | HU (25) | SCD w/o COVID-19 | Among seropositive patients, none had displayed symptoms except one who was hospitalized for mild vaso-occlusive symptoms with a favorable outcome. | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Clift et al. [38] | UK | 287 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | n/a | COVID-19 w/o SCD | SCD pts. had 4-fold and 2.6-fold increased risk of hospitalization and death due to COVID-19, respectively. | 40 (14) | 10 (3.5) | 23,561 (4.4) | 19,008 (3.5) |

| De Sanctis et al. [35]1 | Oman | 3 (1/2) | 27 | n/a | HU (3), BT (1) | None | SCD and other comorbidities can aggravate COVID-19 severity despite favorable outcome; Two SCD pts. had worsening anemia; Respiratory complications rapidly improved after red blood cell exchange BT in one patient. | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Fisler et al. [90]1 | USA | 2 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | n/a | None | Two SCD pts. were admitted to ICU for ACS. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Gampel et al. [65]1 | USA | 1 (1/0) | 12 | HbSC | n/a | None | SCD pt. with h/o prior pulmonary and cardiac complications died of COVID-19 disease. | n/a | 1 (100) | n/a | n/a |

| Hippisley-Cox et al. [52]1 | UK | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | COVID-19 w/o SCD | SCD vaccinated pts. had 7.7-fold increased risk of COVID-19 mortality. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Hoogenboom et al. [39] | USA | 53 (28/25) | 30 | HbSS (39), HbSC (11), HbSβ (3) | n/a | Matched and unmatched COVID-19 pts. w/o SCD | SCD pts. were more likely to visit the ED and be hospitalized than the general population. Mortality, severe disease, and other outcomes in SCD pts. was not different from controls. | 39 (74) | 3 (8)3 | n/a | 5 (6)3 |

| Kamdar et al. [40] | USA | 30 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | HU (19), BT (3) | None | SCD pts. had more ED visits and hospitalization than other hematological pts. with COVID-19. | 14 (47) | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Konté et al. [100] | Netherlands | 5 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | n/a | None | Low incidence of COVID-19 in SCD pts. presenting with VOC, suggesting that COVID-19 is not a major provoking factor for VOC. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Minniti et al. [36] | USA | 66 (30/36) | 34 | HbSS or HbSβ0 (47), HbSC (14), HbSβ+ (5) |

HU (28), BT (30) | None | SCD pts. over 50yo with preexisting conditions with elevated creatinine, LDH, and D-dimer are at higher risk of death regardless of genotype or sex. All deaths occurred in pts. not on HU. | 50 (76) | 7 (11)3 | n/a | n/a |

| Mucalo et al. [29]4 | USA | 364 (187/176) | 11 | HbSS or HbSβ0 (263), HbSC or HbSβ+ (98) |

HU (203), BT (39) | None | SCD children with h/o pain, renal, and heart/lung comorbidities are at higher risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes. | 146 (40.1) | 1 (0.3) | n/a | n/a |

| Mucalo et al. [29]5 | USA | 386 (159/220) | 31 | HbSS or HbSβ0 (261), HbSC or HbSβ+ (113) |

HU (191), BT (53) | None | SCD Adults with h/o pain are at higher risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes. | 231 (59.8) | 18 (4.7) | n/a | n/a |

| Nathan et al. [66]1 | France | 3 (−/2) | 17 | n/a | BT (2) | None | Two SCD pts. developed ACS and required ICU and NIV. | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Oualha et al. [101]1 | France | 4 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | n/a | None | All SCD pts. received BT for respiratory deterioration in ICU. | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Panepinto et al. [30] | USA | 178 (75/101) | 29 | HbSS or HbSβ0 (135), HbSC or HbSβ+ (42), Unknown (1) |

BT (68) | None | SCD pts. have a high risk for severe disease course and high case-fatality rate in comparison to the US population, and non-SCD pts. of the same age showed lower mortality. | 122 (68.5) | 13 (7.3) | n/a | n/a |

| Ramachandran et al. [31] | USA | 9 (5/4) | 28 | HbSS (8), HbSC (1) | HU, (6) BT (6) | COVID-19 w/o SCD | SCD pts. had relatively mild disease course. | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | 3 (5.6) |

| Singh et al. [[33]] | USA | 312 (117/195) | 31 | n/a | n/a | Matched COVID-19 pts. w/o SCD | Black SCD pts. are more likely to be hospitalized and develop pneumonia and pain than Black pts. w/o SCD but do not differ in mortality. | 129 (41.3) |

10 (3.2) | 60 (19.2) |

10 (3.2) |

| Telfer et al. [32] | UK | 166 (71/95) | n/a | HbSS or HbSβ0 (129); HbSC, HbSβ+, or HbSE (37) |

BT (60) | None | Significant number of hemoglobinopathy pts. in the UK developed COVID-19; SCD pts. in the age groups 18–49 and 50–79 have an increased risk of COVID-19 related death. | 128 (77) | 11 (6.6) | n/a | n/a |

| Waghmere et al. [94] | India | 7 (0/7) | 28 | HbSS (6), HbSβ (1) | n/a | Pregnant COVID-19 w/o SCD | Pregnant women with SCD have increased risk of pregnancy complications in comparison to non-SCD pregnant women. | n/a | 0 (0)3 | n/a | 11 (0.7)3 |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute chest syndrome; AKI, acute kidney injury; ALI, acute liver injury; BT, blood transfusion; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ED, emergency department; h/o, history of; Hosp., hospitalization; HTN, hypertension; HU, hydroxyurea; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; LOS, length of stay; n/a, not available, not applicable, unknown, or not specified; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; pts., patients; SCD, sickle cell disease; SCT, sickle cell trait; VOC, vaso-occlusive crisis; w/o, without.

Focus of study was not SCD.

50 total patients with a total of 67 VOC episodes, hospitalization rate is based on total episodes.

In-hospital.

Pediatric arm of the study.

Adult arm of the study.

Table 3.

Case reports of patients with SCD and COVID-19. Authors listed in alphabetical order.

| Authors | Country | Sample size n (M/F) |

Age (years) | Hb genotype (n) | SCD therapy (n) |

Main findings | Hosp. rate n (%) |

Mortality rate n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AbdulRahman et al. [102] | Bahrain | 6 (4/2) | 31 | HbSS (6) | HU (6) | Infection rate, clinical course, and viral clearance of SCD pts. were no different from pts. w/o SCD. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Al-Hebshi et al. [75] | Saudi Arabia | 2 (1/1) | 13 | HbSS (2) | HU (2) BT (1) |

VOC and ACS complicated infection but were effectively treated according to national guideline and standard practice. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Allison et al. [67] | USA | 1 (1/0) | 27 | HbSC (1) | BT (1) | Early red blood cell exchange treatment may have helped mitigate COVID-19 pneumonia and ACS. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Al-Naami et al. [41] | Saudi Arabia | 3 (2/1) | 25 | HbSS (3) | HU (1) | Disease course was mild to moderate w/o complications or death. | 2 (67) | 0 (0) |

| Al-Naami et al. [103] | Saudi Arabia | 1 (1/0) | 29 | HbSS/Sβ0 | HU (1) | Pt presented asymptomatic with h/o sore throat and loose motions; Uneventful recovery. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Al Sabahi et al. [76] | Oman | 5 (4/1) | 5 | HbSS/HbSβ+ (4/1) | HU (2) BT (4) |

Variable disease courses. All cases recovered. | 4 (80) | 0 (0) |

| Al Yazidi et al. [104] | Oman | 7 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | BT (2) | Most pts. had SCD-related symptoms, including ACS, VOC, and splenic sequestration. Three required supplemental oxygen. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| André et al. [77] | France | 1 (0/1) | 5 | n/a | n/a | ICU admission for rapid respiratory degradation after initial phase with mild symptoms. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Anusim et al. [42] | USA | 11 (4/7) | 44 | HbSS (5), HbSC (4), HbSβ+ (1), HbSα (1) | BT (5) | Pt presentations varied from mild to severe; Older age/milder genotypes had worse outcomes; ACS and COVID-19 pneumonia present similarly and should be differentiated before treatment. | 10 (91) | 2 (18) |

| Appiah-Kubi et al. [78] | USA | 7 (2/5) | 14 | HbSS (6), HbSC (1) |

HU (4) BT (1) |

One ICU stay, no intubations. Favorable outcomes were due to early diagnosis, use of antivirals, anti-inflammatory agents, and anticoagulants. | 4 (57) | 0 (0) |

| Argüello-Marina et al. [105] | Spain | 7 (n/a) | n/a | n/a | n/a | Two ICU admissions, one patient required ventilation. Variable medications and treatments used. Overall, patients had short lengths of stay and no deaths. | 5 (71) | 0 (0) |

| Azerad et al. [106] | Belgium | 3 (1/2) | 30 | HbSS (3) | HU (3) BT (3) |

SCD pts. showed mild clinical presentation of COVID-19, which can be misleading; If BT is performed, always consider risk of DHTR. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Beerkens et al. [54] | USA | 1 (1/0) | 21 | HbSβ0 (1) | HU (1) BT (1) |

COVID-19 may have caused or exacerbated ACS. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Chakravorty et al. [43] |

UK | 10 (3/7) | 37 | HbSS (10/10) | HU (2) BT (6) |

All but one seemed to be experiencing a relatively mild course despite significant comorbidities. | 7 (70) | 1 (10) |

| Chen-Goodspeed et al. [44] |

USA | 5 (3/2) | 31 | HbSS (4), HbSC (1) | HU (3) BT (2) |

SCD pts. did not present typical COVID-19 symptoms but rather more typical SCD symptoms, including VOC; SCD pts. presenting with VOC should immediately be tested for COVID-19. | 3 (60) | 0 (0) |

| Dagalakis et al. [79] | USA | 1 (1/0) | 0.5 | HbSC | n/a | Pediatric pt. presented with mild symptoms and remained stable throughout hospitalization. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| De Luna et al. [107] | France | 1 (1/0) | 45 | HbSS | BT (1) | Severe pneumonia and severe ACS effectively treated with hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Elia et al. [[56]] | Brazil | 3 (1/2) | 11 | HbSS (2), HbSC (1) | HU (2) | SCD pts. showed better clinical evolution than predicted; Pulmonary viral infections can trigger SCD symptoms and need for hospitalization; COVID-19 symptoms are very similar to ACS symptoms, which affects clinical decision. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Ershler et al. [108] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 39 | HbSS | BT (1) | Acute crisis and COVID-19 pneumonia effectively treated with voxelotor in lieu of single BT. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Espanol et al. [80] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 8 | HbSS | HU (1) BT (1) |

Patient was successfully managed after developing severe ACS secondary to COVID-19, complicated by cortical vein thrombosis and multisystem inflammatory syndrome. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Fronza et al. [109] | Italy | 1 (0/1) | 44 | n/a | BT (1) | Patient recovered and was discharged after severe anemia and acute lung failure. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Hardy et al. [110] | Ghana | 3 (0/3) | 28 | HbSS (1), HbSC (2) |

BT (2) | One had severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Two had severe SCD crisis. All had favorable outcomes. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Heilbronner et al. [81] | France | 4 (1/3) | 15 | HbSS (4) | HU (2) BT (4) |

All pts. presented with ACS and admitted to PICU. Pts were effectively treated with erythrapheresis, NIV, and typical supportive treatment. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Hussain et al. [55] | USA | 4 (2/2) | 33 | HbSS (2), HbSC (1), HbSβ+ (1) |

BT (1) | All four pts. initially presented to the ED for typical VOC; the clinical course of their COVID-19 infection was rather mild. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Jacob et al. [82] | USA | 1 (1/0) | 2 | HbSS | HU (1) BT (1) |

Pediatric pt. with severe anemia, splenic sequestration crisis and COVID-19; Pt greatly improved following BT. Mild clinical course during hospitalization, with no apparent morbidity related to COVID-19. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Justino et al. [111] | Brazil | 1 (0/1) | 35 | HbSS | BT (1) | Despite previous h/o pulmonary disease and current pregnancy, clinical course was very favorable. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Kasinathan et al. [83] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 20 | HbSC | BT (1) | SCD diagnosis was unknown at time of presentation. Pulmonary embolism complicated condition. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Martone et al. [84] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 19 | HbSβ0 | BT (1) | PT developed ACS with fever, decreased hemoglobin, but no hypoxemia, which was managed with BT and antibiotics. Four weeks later, pt. was re-hospitalized with post-COVID-19 encephalopathy, hyperammonemia, hyperinflammation, and multi organ failure. Patient recovered to neurologic baseline and normal liver function. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| McCloskey et al. [53] |

UK | 10 (8/2) | 36 | HbSS or HbSβ0 (9), HbSC (1) |

BT (5) | Overall, the outcome of COVID-19 infection was favorable for this cohort of SCD pts., unless there were significant comorbidities. | n/a | 1 (10) |

| Morrone et al. [73] | USA | 8 (4/4) | 16 | HbSS (7), HbS HPFH (1) |

HU (3) BT (3) |

SCD pts. not admitted and did not develop ACS were on HU and had lower absolute monocyte counts compared to those admitted and developed ACS. | 5 (63) | 0 (0) |

| Nur et al. [112] | Netherlands | 2 (1/1) | 22 | HbSS (2) | n/a | COVID-19 might trigger VOC w/o typical flu-like symptoms; ACS developed w/o typical COVID-19 pulmonary complications; SCD pts. presenting with VOC should be tested for COVID-19. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Nguyen et al. [113] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 69 | HbS HPFH | BT (1) | SCD pt. requiring ICU admission w/ intubation and mechanical ventilation quickly improved following RBC exchange transfusion. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Odiévre et al. [85] | France | 1 (0/1) | 16 | HbSS | HU (1) BT (1) |

Tocilizumab proved to be an effective treatment for this SCD patient with severe COVID-19 and ACS. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Okar et al. [68] | Qatar | 1 (1/0) | 22 | n/a | HU (1) BT (1) |

Due to similarities between ACS and COVID-19 pneumonia, SCD pts. should be closely monitored and offered BT early in the clinical course to avoid clinical deterioration. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Okar et al. [69] | Qatar | 1 (1/0) | 48 | n/a | HU (1) BT (1) |

Close monitoring of SCD pts. is essential despite favorable outcomes due to acute complications; BT early in the disease course is beneficial against hemolysis and VOC. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Parodi et al. [86] | Italy | 2 (1/1) | 1.2 | HbSS (2) | BT (2) | Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection revealed a hidden condition of SCD. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Quaresima et al. [87] | Italy | 1 (0/1) | 18 | HbSS | HU (1) BT (1) |

Pt had ACS and abnormal chest CT but no resp. symptoms, remained COVID-19 pos for a long time, and rare blood type prohibited BT. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Roussel et al. [88] | France | 1 (0/1) | 6 | HbSS | n/a | Cranial polyneuropathy was the first manifestation of severe COVID-19 in a child and cranial nerve involvement may indicate poor disease course. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Sahu et al. [45] | USA | 5 (2/3) | 33 | HbSS (2), HbSC (2), HbSβ (1) |

HU (2) BT (1) |

None of the pts. required intensive care or mechanical ventilation with only one patient had a new oxygen requirement. SCD COVID-19 pts. need multidisciplinary treatment of pneumonia, VOC, ACS, with supportive care for favorable outcome. |

4 (80) | 0 (0) |

| Santos de Lima et al. [114] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 43 | n/a | BT (1) | Combination of COVID-19 and SCD may increase risk of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and contribute to higher mortality. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Teulier et al. [115] | France | 1 (1/0) | 33 | HbSS | HU (1) BT (1) |

SCD patient developed severe ARDS secondary to COVID-19 and was successfully treated with anticoagulation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; patient did not develop pulmonary arterial hypertension, suggesting different pathophysiology in SCD pts. | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Walker et al. [89] | USA | 1 (0/1) | 10 | HbSS | BT (1) | Patient developed COVID-19 and ACS requiring red blood cell exchange and remdesivir treatment. | n/a | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute chest syndrome; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BT, blood transfusion; CT, computed tomography; DHTR, delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction; h/o, history of; Hosp., hospitalization; HPFH, hereditary persistent fetal hemoglobin; HU, hydroxyurea; ICU, intensive care unit; n/a, not available, not applicable, unknown, or unspecified; pts., patients; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; SCD, sickle cell disease; VOC, vaso-occlusive crisis.

3.1. Sample characteristics

There were 2290 persons with SCD and SARS-CoV-2 infection analyzed by all studies combined and included in this review (Table 1). The SCD cohort had a median age of 25 years (interquartile range = 17–39 years), was 56% female, and 62% had Hb-SS hemoglobin genotype (Table 1). The relatively young age of patients with SCD and COVID-19 could be explained by the short life expectancy of SCD patients (43 years in 2017 [18]) relative to the general population (79 years in 2017 [19]). Despite young age, SCD patients had substantial comorbidities (i.e., hypertension, asthma/COPD, and chronic kidney disease), consistent with end-organ damage from SCD [20,21].

At hospital presentation, oxygen saturation was 95%, body temperature was 101.6F, and BMI was 28. Laboratory values were above normal range for lactate dehydrogenase, bilirubin, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and D-dimer; below normal range for hemoglobin; and within normal range for lymphocyte count. These altered laboratory values are consistent with SCD-related manifestations of red blood cell dysfunction [6,22]. Elevated lactate dehydrogenase and D-dimer could be suggestive of more severe COVID-19 disease [23] but could also result from intravascular hemolysis, ischemia-reperfusion damage and tissue necrosis associated with SCD and could be further elevated during acute vaso-occlusive crisis [24].

3.2. Clinical course

Adult SCD patients typically experience mild to moderate COVID-19-related symptoms [[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]], which is characterized by few respiratory symptoms and not requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Large US registry studies found that approximately 80% of adult SCD patients experience mild to moderate symptoms (or no symptoms at all) [29,30] and that the type of COVID-19-related symptoms, including cough/fever or more severe symptoms such as respiratory failure, were not different from patients without SCD [33]. However, SCD-related comorbidities, in particular acute pain has been found highly prevalent during COVID-19, and history of pain was associated with increased risk of hospitalization [29].

A few smaller cohort studies observed more severe COVID-19 disease course among adult SCD patients [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. Severe disease course is typically characterized by patients needing escalated care and prolonged hospitalization due to severe COVID-19 symptoms (e.g., hypoxia, pneumonia, prolonged fever, multisystem inflammation) or severe SCD-related complications (e.g., ACS, severe pain crisis), or both. One study observed increased hospitalization, mild to moderate pneumonia, and intubation among SCD patients as compared to age-matched healthcare professionals [37]. Another study identified older patients, pre-existing conditions, and end-organ damage as high risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease course and poor outcome [36].

3.3. Hospitalization trends

There is strong evidence that patients with SCD have an increased risk of COVID-19-related hospital admissions. Large cohort studies in the UK and US have reported a 2- to 7-fold increased risk of COVID-19-related hospital admission for patients with SCD relative to the general population [[33], [38], [39]]. Most observational studies reported hospitalization rates of greater than or equal to 40% among patients with SCD and SARS-CoV-2 infection [26,28,30,32,35,36,[33], [39], [40]], which remained increased after age, gender, and race adjustment when compared to the general population [[33], [38], [39]]. The hospitalization rate of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general population is markedly lower. For example, peak hospitalization for the US population was 20.5% (first week of January 2021; https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/) and 19.2% in Black patients without SCD in a large US registry study [33]. Case studies show even higher hospitalization trends, although this may be in part due to patient selection bias. Of the 9 case studies that reported both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, the COVID-19-related hospitalization rate for persons with SCD was 72% (44/61) [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45]].

There could be several explanations for the high hospitalization rate observed among patients with SCD. We hypothesize that the high baseline hospital admission and readmission rate for patients with SCD, independent of COVID-19, may have been contributing factors, in addition to perhaps COVID-19 triggering an acute vaso-occlusive crisis requiring hospitalization, as well as overlap in SCD and COVID-19 symptoms (i.e., the clinical picture for both ACS and COVID-19 pneumonia can be similar) [[46], [47], [48]]. From the aggregated data, 64% of SCD patients presented with abnormal chest x-ray/computed tomography, 62% with pain crisis, and 42% with physician described diagnosis of ACS. ACS is a leading cause of death in SCD patients [49,50] and it is likely that SCD patients with COVID-19 were admitted to the hospitals as a precaution.

3.4. Risk of death

Among all observational cohort studies with adult patients included in this review, there were 79 COVID-19-related fatalities among 1720 patients with SCD, which represents an overall mortality rate of 4.6%. In the same cohort studies, there were 21,986 COVID-19-related fatalities among 587,554 patients without SCD, which represents an overall mortality rate of 3.7%. Based on this data from 7 different countries (i.e., Bahrain, France, India, Oman, Turkey, UK, and USA) SCD, relative to non-SCD, is associated with an overall 1.2-fold increased risk of COVID-19-related death among adult patients. In line with this observation, one of the largest cohort studies with SCD patients to date [38], conducted in the UK with a non-SCD comparison group and covariate-adjusted analysis, showed that patients with SCD were 2.5-fold more likely to die from COVID-19 than patients without SCD at any time during the study (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.55, 95% CI = 1.36 to 4.75). Hazard ratio not only considers the total number of events, such as in relative risk and odds ratio estimates, but also the timing of each event [51]. Interestingly, Hippisley-Cox et al. [52] analyzed vaccinated cohorts and reported a substantially higher hazard ratio (HR = 7.73) for SCD patients than Clift et al. 2021 [38] (HR = 2.55) who analyzed mostly unvaccinated people in the same UK database. This may suggest that persons with SCD have a suboptimal response to COVID-19 vaccination, which warrants further investigation.

There are additional cohort studies that reported a higher risk of COVID-19 related death associated with SCD [30,32,36,37], although these studies lacked proper comparison groups. It is possible that negative outcomes reported in some of these studies are associated with other factors, such as access to care, pre-existing conditions, and other risk factors unique to these study samples, rather than SCD itself [36]. Among case studies, nearly all studies reported favorable outcomes, regardless of disease course. In 3 case studies, there were 4 deaths (all adults) out of 121 individuals with SCD [42,53,43], which represents 3.3% mortality rate.

Interestingly, SCD cohort studies utilizing controls matched for pre-existing conditions reported no significant differences in COVID-19-related mortality rate between patients with or without SCD [39,33], or between SCD patients with or without COVID-19 [26]. This implies that SCD patients do not have different COVID-19-related mortality rate as compared to non-SCD patients who have similar rates of comorbidities and end-organ damage. It further indicates that organ damage, caused by SCD or another condition, is a risk factor for COVID-19 related death.

Even though SCD is associated with increased risk of COVID-19 related death, it may not be as high as feared. While viral infections can trigger SCD symptoms [50,54], favorable COVID-19 outcomes for patients with SCD may in part be explained by the high hospitalization rate for this population, which could have contributed to timely intervention for symptomatic patients and improved survival probability. It is also possible that certain pathophysiological characteristics of SCD provide protective effects from fatal COVID-19 disease [55]. In line with this idea, some case studies reported that those with milder hemoglobin genotype had worse outcomes [42,56], although this could also be explained by a lack of hydroxyurea treatment associated with milder genotypes, which may have contributed to unfavorable outcomes. It has been recently demonstrated by proteomic analysis that neutrophils in patients with SCD present an unexpected activation of the interferon-α signaling pathway [57]. Interferons have been suggested as being a potential treatment for COVID-19 due to its antiviral activities [58,59]. The notion that SCD has some protective effect against COVID-19 should be further explored.

We conclude that based on the available empirical data in the literature, adults with SCD have an increased risk of death and a different temporal progression of death or survivorship curves following COVID-19 diagnosis as compared to adults without SCD, unless compared to controls with similar comorbidities and end-organ damage. The effects of demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic variables on risk estimates of critical illness and death are further discussed in section ‘3.5 Risk factors.’ Of important note, although some studies have reported favorable short-term outcomes among COVID-19 patients with SCD, the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection are unknown. Patients with COVID-19 and SCD may experience lingering symptoms and long-term health problems that differ from the general population. Therefore, long term follow-up studies of these individuals are warranted. Furthermore, there is limited data on less severe and other types of COVID-19-related outcomes among SCD patients. One cohort study reported that persons with SCD experience more COVID-19-related pneumonia and pain than individuals without SCD [33].

3.5. Risk factors

Observational cohort studies [27,29,32,36] and case reports [43,53] suggest that advanced age, preexisting conditions, and male sex are risk factors for unfavorable COVID-19 outcomes in patients with SCD, similar to the reported risk factors in the general population [60,61]. Furthermore, because of marked differences in disease severity between different sickle genotypes, COVID-19 outcomes may vary between sickle cell patients. Interestingly, various studies observed that genotypes associated with milder SCD (i.e., HbSC, HbSE, HbSβ+) had no different or worse outcomes than genotypes associated with more severe SCD (i.e., HbSS, HbSβ0) [27,30,32,42,56]. We speculate that sickle cell anemia-specific therapies or pathophysiology, such as activation of the interferon-α signaling pathway as discussed earlier in this work, may provide a protective effect against COVID-19, but the reasons for this observation are unknown and require further investigation. It is known, however, that SCD symptoms could complicate the COVID-19 disease course. For example, Mucalo et al. [29] reported that adults with a history of pain are at higher risk of worse disease severity. Another major concern unique to patients with SCD is pulmonary thrombosis, which is prevalent in both SCD [62] and COVID-19 [63]. Therefore, having both conditions could conceivably result in even higher risk of severe disease. Persons with SCD would benefit from individual risk assessment for poor COVID-19 outcomes although a history of SCD complications does not necessarily lead to unfavorable outcomes. For example, Anusim et al. [42] reported that prior sickle cell complications such as avascular necrosis of the joints, hypersplenism requiring splenectomy, and cerebrovascular accident did not associated to the outcome of patients with COVID-19.

3.6. SCD-modifying therapy

Several authors have speculated on the potential beneficial effects of SCD directed therapies against COVID-19 disease. Simple or exchange blood transfusion was the primary therapy reported by observational cohort studies [[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32],[35], [36], [37],40,[64], [65], [66]]. Among case studies, 47% of SCD patients (60 out of 129 individuals) received regularly scheduled chronic transfusion prior to COVID-19 diagnosis and/or received transfusion during COVID-19 disease course. Several reports suggest that early red blood cell exchange is successful in the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia [35,54,55,67], severe hemolysis and vaso-occlusive crisis [68], and might prevent patients with SCD from experiencing further clinical deterioration [69] and intubation [67].

Hydroxyurea treatment is another common therapy for SCD [27,29,31,[35], [36], [37],40,70] and was received by 32% of SCD patients (41 out of 129 individuals) in case studies. The beneficial effects of hydroxyurea treatment on SCD-related morbidity and mortality are well known [71,72]. Minniti et al. [36] reported that all deaths occurred in patients not on hydroxyurea or other SCD-modifying therapies. Morrone et al. [73] reported that patients on hydroxyurea did not develop ACS. Mucalo et al. [29] though found that hydroxyurea had no effect on hospitalization or COVID-19 disease severity. Interestingly, of the 4 reported case-study deaths, 3 did not receive transfusion or hydroxyurea treatment, and one patient did not have data on transfusion or hydroxyurea treatment. Prospective studies are needed to further examine the effects of SCD-modifying therapies on COVID-19 outcomes.

3.7. Pediatric patients with SCD

In the general population, children are less likely to experience severe COVID-19 outcomes as compared to adults [74], but only few studies [29,70] have examined children with SCD and SARS-CoV-2 infection in sufficiently large cohorts from which valid inferences can be drawn, as the vast majority of studies were case reports with less than 10 patients [56,65,66,73,[75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89]].

In one of the largest pediatric studies to date, Mucalo et al. [29] analyzed 364 US children with SCD and SARS-CoV-2 infection (median age 11 years, 72% Hb-SS/HbS-beta0 thalassemia, 56% on hydroxyurea treatment) and found most children to be asymptomatic (25.5%) or to experience mild to moderate symptoms (65.6%) although some had more severe or critical symptoms (8.2%). Furthermore, the sample was associated with 40% hospitalization rate, 5.8% ICU admission, 1.1% ventilator use, and 1 death (0.3%). Risk factors for worse COVID-19 outcomes were history of pain, and renal and heart/lung comorbidities. No effects of hydroxyurea on hospitalization or COVID-19 severity were observed. These findings were mostly in accordance with a smaller French cohort study by Brousse and colleagues [70] who analyzed 39 children with SCD and SARS-CoV-2 infection (median age 12 years, 90% Hb-SS, 64% on hydroxyurea treatment) and found that none had displayed symptoms except one who was hospitalized for mild vaso-occlusive symptoms with a favorable outcome. It was hypothesized that activation of the type I Interferon (IFN-I) pathway may have contributed to partial protection from SARS-CoV-2 severe illness and death seen in their pediatric sample. Among the smaller pediatric studies [56,65,66,73,[75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89]] that reported on a combined 42 children with SCD, there was 1 (2.4%) patient with a history of prior pulmonary and cardiac complications who died from COVID-19 disease.

While the literature suggests that most children with SCD who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 have mild disease and low risk of death, children with SCD, especially those with SCD-related comorbidities [29,65,66,90], are more likely to be hospitalized and require escalated care than children without SCD of the same age [91]. However, compared to adults with SCD [29] and adults without SCD [38], children with SCD are less likely to experience COVID-19-related severe illness and death. There was not sufficient data to review children with SCT and COVID-19. Multicenter studies with larger sample size are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

4. Patients with COVID-19 and sickle cell trait

Table 4 summarizes the study parameters and main findings of 7 observational cohort studies [28,[33], [38], [39],[92], [93], [94]] and 4 case studies [75,90,95,96] reporting on a total of 1937 individuals with SCT and COVID-19.

Table 4.

Study characteristics and main findings of reports on individuals with SCT and COVID-19. Authors listed in alphabetical order.

| Authors | Country | Study type | Sample size n (M/F) |

Age (years) | Control group | Main findings | SCT |

Non-SCT |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hosp. rate n (%) |

Mort. rate n (%) |

Hosp. rate n (%) |

Mort. rate n (%) |

|||||||

| Al-Hebshi et al. [75] | Saudi Arabia | Case report | 1 (0/1) | 50 | None | No significant symptoms, except for headache and fatigue prior to testing. Normal labs and chest X-ray. | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Balanchivadze et al. [28] | USA | Case report | 18 (3/15) | 58 | None | SCT pts. generally had mild disease course with lower chances of intubation, ICU admission, and death. | 11 (61) | 1 (6) | n/a | n/a |

| Clift et al. [38] | UK | Obs. | 1346 (n/a) | n/a | COVID-19 w/o SCT | SCT pts. had 1.4-fold and 1.5-fold increased risk of hospitalization and death due to COVID-19, respectively. | 98 (7.3) | 50 (3.7) | 23,561 (4.4) | 19,008 (3.5) |

| Hoogenboom et al. [39] | USA | Obs. | 62 (13/49) | 47 | Matched and unmatched COVID-19 w/o SCT | SCT pts. did not differ from (un)matched controls in laboratory values or outcomes. | 31 (50) | 7 (23)1 | n/a | 20 (18)1 |

| Merz et al. [93] | USA | Obs. | 20 (11/9) | 66 | COVID-19 w/o SCT | SCT did not impact respiratory, renal, or circulatory complications or mortality in COVID-19 pts. when compared to non-SCT pts. | n/a | 3 (15)1 | n/a | 19 (13)1 |

| Quaresima et al. [87] | Italy | Obs. | 2 (1/1) | 51 | None | Prolonged positivity for SARS-CoV-2, but mostly asymptomatic to mild disease course. | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Resurreccion et al. [92] | UK | Case report | 14 (6/8) | 64 | COVID-19 w/o SCT | Black SCT pts. had similar infection rates, but higher mortality compared to Black pts. w/o SCT. Diabetes was a risk factor for COVID-19 related death. | n/a | 4 (29) | n/a | 21 (13) |

| Sheha et al. [95] | Egypt | Obs. | 1 (0/1) | 22 | None | First case of SCD diagnosed due to concurrent COVID-19.2 | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Singh et al. [[33]] | USA | Case report | 449 (237/212) | 37.7 | Matched COVID-19 pts. w/o SCT | Black pts. with SCT did not differ in COVID-19 disease course or outcomes compared to Black pts. w/o SCT. | 79 (18) | 10 (2.2) | n/a | n/a |

| Tafti et al. [96] | USA | Obs. | 1 (1/0) | 33 | None | Pt developed rhabdomyolysis, myonecrosis, and an abscess, all of which were exacerbated by COVID-19 / SCT. | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a |

| Waghmere et al. [94] | India | Obs. | 24 (0/24) | n/a | Pregnant COVID-19 w/o SCT | Pregnant women with SCT have increased risk of pregnancy complications in comparison to pregnant women w/o SCT. | n/a | 1 (4.2)1 | n/a | 11 (0.7)1 |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute chest syndrome; AKI, acute kidney injury; ALI, acute liver injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department; Hosp., hospitalization; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; LOS, length of stay; n/a, not available, not applicable, unknown, or not specified; Mort., mortality; pts., patients; Obs., observational cohort study; SCD, sickle cell disease; SCT, sickle cell trait; w/o, without.

In-hospital.

Patient tested positive for SCT but was suspected SCD.

4.1. Sample characteristics

There were 1937 persons with SCT and SARS-CoV-2 infection analyzed by all studies combined and included in this review (Table 1). The SCT cohort had a median age of 54 years (interquartile range = 40 to 61 years) and was 54% female. A relatively large proportion of patients had hypertension (42%), followed by asthma/COPD (30%) and diabetes (23%), which may represent an age-related effect. Patients presented with 96% oxygen saturation, 100.3F temperature, and a BMI of 32. All laboratory values where within normal range, except for lactate dehydrogenase, c-reactive protein, and D-dimer which were above normal range possibly due to systemic inflammation and coagulation dysfunction associated with more severe COVID-19 [97,98]. Of note, aggregated data, including laboratory values, should be interpreted with caution due to small sample sizes.

4.2. Clinical course

Most studies [28,39,33,75,87,93] reported mild COVID-19 disease course for individuals with SCT similar to individuals without SCT, and only very few SCT patients required escalated care (i.e., intensive care, intubation, need for mechanical ventilation) or developed severe disease complications. However, pregnant women with SCT may experience increased risk of pregnancy complications (e.g., gestational hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction) and more COVID-19-related symptoms in comparison to pregnant women without SCT [94]. Among case studies, only 2 patients with SCT reportedly had more severe disease course. In one case, the patient was not known to have SCT prior to hospitalization for COVID-19 and may have had disease phenotype masked by the transfusions [95]. The second SCT case had rhabdomyolysis after significant exertion due to exercise [96]. Some studies did not collect or analyze any clinical course data from its cohort [38,92].

4.3. Hospitalization trends

Hospitalization rates for patients with SCT and COVID-19 varied greatly between studies from 17.6% [33] to 61.1% [28], while 1 study did not report it for their cohort [92]. In a large UK cohort, SCT was associated with a 1.4-fold increased risk of hospitalization compared to the general population adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity [38]. Variation in reported hospitalization rates is likely due to differences in cohort characteristics as studies with higher hospitalization rates included significantly older patients with SCT who had many comorbidities [28,39], which can be viewed as additional risk factors for hospitalization. In fact, studies with comorbidities-matched controls showed no differences in COVID-19-related hospitalization for those with SCT compared to those without SCT [39,33], which implies that comorbidities and not SCT perse are associated with an increased risk of admissions.

4.4. Mortality rate

Similar to hospitalization rates, the reported COVID-19-related mortality rates for persons with SCT vary greatly between studies from 2.2% [33] to 28.6% [92]. In one of the largest studies with SCT patients to date, persons with SCT were found to have a 1.5-fold increased risk of death due to COVID-19, similar to SCD albeit to a lesser extend [38]. Another study confirmed these findings [92], but only in a small sample without demographic-matched controls. There are also large cohort studies that have shown no difference in mortality rates between individuals with or without SCT and COVID-19 [39,33,93]. Differences in matching criteria, especially related to comorbidity-matching, may explain some of the discrepancies observed in reported mortality rates between studies. No studies analyzed risk factors for mortality except for one [92], which found preexisting diabetes to increase risk of death in SCT patients. Unique factors that lead to severe disease and death among SCT patients, such as comorbidity burden or genetic predisposition, are unknown and require further investigation.

5. Summary and conclusions

This comprehensive review summarizes the clinical characteristics and COVID-19-related outcomes of patients with SCD and SCT from the published literature to date. While most studies reported mild to moderate COVID-19-related disease course in this patient population, the literature suggests that SCD is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19, unless compared to controls with similar comorbidities and end-organ damage. Advanced age, preexisting conditions, and male sex are risk factors for unfavorable COVID-19 outcomes in patients with SCD, similar to the reported risk factors in the general population. There is some evidence that SCD-modifying therapies such as transfusion and hydroxyurea may be associated with better COVID-19 outcomes, but prospective studies are needed for confirmation. There is some evidence that persons with SCT have increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization and death although more studies with risk-stratification and properly matched controls are needed to confirm these findings.

6. Future perspectives

Based on this review of the current literature, there are various suggested future directions to move the field forward and improve our understanding of COVID-19 outcomes among patients with SCD and SCT. First, an important focus area for future studies should include multi-center collaboration to generate larger cohorts, which will generate more definite evidence related to COVID-19 outcomes among patients with SCD/SCT. Currently, two-thirds of published COVID-19 studies with SCD/SCT patients are case reports. While case reports provide important and detailed information at the patient level, often detecting novelties and generating hypotheses, the lack of generalizability, danger of over-interpretation, and publication bias are major limitations of the case report genre [99]. For this reason, population level inferences should be based on larger controlled experimental studies. Second, into what extend hemoglobin genotype or sickle cell therapy impact COVID-19 infection is largely unknown. Because of marked differences in disease severity between different hemoglobin genotypes, COVID-19 outcomes may vary between sickle cell patients, which requires further investigation. Third, future studies should include case-matched controls that account for the unique sample characteristics of SCD and SCT populations. Patients with SCD and SCT often have unique underlying conditions that could make them more vulnerable to poor COVID-19 outcomes. Fourth, while most studies have reported favorable short-term outcomes among COVID-19 patients with SCD and SCT, especially related to severe illness and death, the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection are unknown. It is possible that SCD patients with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection experience more lingering symptoms and long-term health problems compared to survivors of COVID-19 disease in the general population. Therefore, long term follow-up studies with longitudinal assessment of post-COVID-19 symptoms are warranted.

Practice points

-

•

Patients with SCD infected with SARS-CoV-2 should be followed very closely as they often have underlying conditions that could make them more vulnerable to poor COVID-19 outcomes.

-

•

A low threshold for admission of SCD patients is common as SARS-CoV-2 infection could trigger acute vaso-occlusive crisis requiring hospitalization and due to overlap of SCD and COVID-19 symptoms (e.g., the clinical picture for both ACS and COVID-19 pneumonia can be similar).

-

•

Transfusion and hydroxyurea treatment have demonstrated benefit in treating SCD-related morbidity and mortality. The role of SCD-directed therapies in COVID-19 appears to be associated with favorable outcomes and is under active investigation.

-

•

While most SCD patients only experience mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms, similar to the general population, SCD is associated with an increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization and death, which indicates that serious illness and death still occurs especially among vulnerable individuals in this patient group.

-

•

Most COVID-19 patients with SCT appear not different from the general population with COVID-19 in terms of admission laboratory values, clinical course, hospitalization trends, and mortality, but additional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Research agenda

-

•

Larger, multisite, randomized studies are needed to generate more definite evidence related to COVID-19 outcomes among patients with SCD/SCT.

-

•

Because of marked differences in disease severity between different hemoglobin genotypes, COVID-19 outcomes may vary between sickle cell patients, which requires further investigation.

-

•

Inclusion of properly matched controls is important to account for the unique sample characteristics of SCD and SCT populations.

-

•

Long term follow-up studies of patients with SCD/SCT are needed as the long-term effects of COVID-19 may affect these patients differently as compared to the general population.

Author contributions

All authors (WSH, TTA, DMM, NB, VD, WBM, KBM, DM, and TD) made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the data, and analysis and interpretation of the data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) review and approval of the final manuscript submitted.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wang D., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen T., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan R.E., Adab P., Cheng K.K. Covid-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Rio C., Collins L.F., Malani P. Long-term health consequences of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1723–1724. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pleasants S. Epidemiology: a moving target. Nature. 2014;515(7526):S2–S3. doi: 10.1038/515S2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees D.C., Williams T.N., Gladwin M.T. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376(9757):2018–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanabe P., et al. CE: understanding the complications of sickle cell disease. Am J Nurs. 2019;119(6):26–35. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000559779.40570.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassell K.L. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naik R.P., et al. Clinical outcomes associated with sickle cell trait: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(9):619–627. doi: 10.7326/M18-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsaras G., et al. Complications associated with sickle cell trait: a brief narrative review. Am J Med. 2009;122(6):507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson J.S., Rees D.C. How benign is sickle cell trait? EBioMedicine. 2016;11:21–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ojodu J., et al. Incidence of sickle cell trait--United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(49):1155–1158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parra-Bracamonte G.M., Lopez-Villalobos N., Parra-Bracamonte F.E. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality of patients with COVID-19 in a large data set from Mexico. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;52:93–98 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tao Z., et al. Anemia is associated with severe illness in COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(3):1478–1488. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans P.C., et al. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: a position paper of the ESC working group for atherosclerosis and vascular biology, and the ESC council of basic cardiovascular science. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(14):2177–2184. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kichloo A., et al. COVID-19 and hypercoagulability: a review. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620962853. p. 1076029620962853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page M.J., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne A.B., et al. Trends in sickle cell disease-related mortality in the United States, 1979 to 2017. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(3S):S28–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.09.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolf S.H., Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordeuk V.R., Castro O.L., Machado R.F. Pathophysiology and treatment of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2016;127(7):820–828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-618561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gladwin M.T., Vichinsky E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2254–2265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rees D.C., Gibson J.S. Biomarkers in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(4):433–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiersinga W.J., et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324(8):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato G.J., et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a biomarker of hemolysis-associated nitric oxide resistance, priapism, leg ulceration, pulmonary hypertension, and death in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2006;107(6):2279–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AbdulRahman A., et al. Is sickle cell disease a risk factor for severe COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients? A multicenter nationalretrospective cohort study. eJHaem. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jha2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alkindi S., et al. Impact of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) on vasooclusive crisis in patients with sickle cell anaemia. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;106:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arlet J.B., et al. Prognosis of patients with sickle cell disease and COVID-19: a French experience. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(9):e632–e634. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balanchivadze N., et al. Impact of COVID-19 infection on 24 patients with sickle cell disease. One center urban experience, Detroit, MI, USA. Hemoglobin. 2020;44(4):284–289. doi: 10.1080/03630269.2020.1797775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mucalo L., et al. Comorbidities are risk factors for hospitalization and serious COVID-19 illness in children and adults with sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2021;5(13):2717–2724. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panepinto J.A., et al. Coronavirus disease among persons with sickle cell disease, United States, march 20-may 21, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):2473–2476. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramachandran P., et al. Low morbidity and mortality with COVID-19 in sickle cell disease: a single center experience. eJHaem. 2020;1(2):608–614. doi: 10.1002/jha2.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telfer P., et al. Real-time national survey of COVID-19 in hemoglobinopathy and rare inherited anemia patients. Haematologica. 2020;105(11):2651–2654. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.259440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh A., Brandow A.M., Panepinto J.A. COVID-19 in individuals with sickle cell disease/trait compared with other black individuals. Blood Adv. 2021;5(7):1915–1921. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alhumaid S., et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of intensive and non-intensive 1014 COVID-19 patients: an experience cohort from Alahsa, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00517-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Sanctis V., et al. Preliminary data on COVID-19 in patients with hemoglobinopathies: a multicentre ICET-A study. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2020;12(1) doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2020.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minniti C.P., et al. Clinical predictors of poor outcomes in patients with sickle cell disease and COVID-19 infection. Blood Adv. 2021;5(1):207–215. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boga C., et al. Comparison of the clinical course of COVID-19 infection in sickle cell disease patients with healthcare professionals. Ann Hematol. 2021;100(9):2195–2202. doi: 10.1007/s00277-021-04549-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clift A.K., et al. Sickle cell disorders and severe COVID-19 outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(10):1483–1487. doi: 10.7326/M21-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoogenboom W.S., et al. Individuals with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait demonstrate no increase in mortality or critical illness from COVID-19 — A fifteen hospital observational study in the Bronx, New York. Haematologica. 2021;106(11):3014–3016. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279222. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamdar K.Y., et al. COVID-19 outcomes in a large pediatric hematology-oncology center in Houston, Texas. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2021.1924327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Naami A.Q., et al. Sickle cell disease (SCD) and COVID-19 – a case series. J Trop Dis. 2021;9(268) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anusim N., et al. Presentation, management, and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with sickle cell disease. EJHaem. 2021;2(1):124–127. doi: 10.1002/jha2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakravorty S., et al. COVID-19 in patients with sickle cell disease - a case series from a UK tertiary hospital. Haematologica. 2020;105(11):2691–2693. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.254250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen-Goodspeed A., Idowu M. COVID-19 presentation in patients with sickle cell disease: a case series. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.931758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahu K.K., et al. COVID-19 in patients with sickle cell disease: a single center experience from Ohio, United States. J Med Virol. 2021;93(5):2591–2594. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar V., Chaudhary N., Achebe M.M. Epidemiology and predictors of all-cause 30-day readmission in patients with sickle cell crisis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2082. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58934-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menapace L.A., Thein S.L. COVID-19 and sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2020;105(11):2501–2504. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.255398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ochocinski D., et al. Life-threatening infectious complications in sickle cell disease: a concise narrative review. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:38. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castro O., et al. The acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: incidence and risk factors. The cooperative study of sickle cell disease. Blood. 1994;84(2):643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vichinsky E.P., et al. Causes and outcomes of the acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. National acute chest syndrome study group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1855–1865. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.George A., Stead T.S., Ganti L. What’s the risk: differentiating risk ratios, odds ratios, and hazard ratios? Cureus. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hippisley-Cox J., et al. Risk prediction of covid-19 related death and hospital admission in adults after covid-19 vaccination: national prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCloskey K.A., et al. COVID-19 infection and sickle cell disease: a UK centre experience. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(2):e57–e58. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beerkens F., et al. COVID-19 pneumonia as a cause of acute chest syndrome in an adult sickle cell patient. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(7):E154–E156. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hussain F.A., et al. COVID-19 infection in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(5):851–852. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elia G.M., et al. Acute chest syndrome and COVID-19 in sickle cell disease pediatric patients. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2021;43(1):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hermand P., et al. The proteome of neutrophils in sickle cell disease reveals an unexpected activation of interferon alpha signaling pathway. Haematologica. 2020;105(12):2851–2854. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.238295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hung I.F., et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Q., et al. Interferon-α2b treatment for COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1061. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan W.J., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Graff K., et al. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(4):e137–e145. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aggeli C., et al. Stroke and presence of patent foramen ovale in sickle cell disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;52(3):889–897. doi: 10.1007/s11239-021-02398-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levi M., et al. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e438–e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al Yazidi L.S., et al. Epidemiology, characteristics and outcome of children hospitalized with COVID-19 in Oman: a multicenter cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gampel B., et al. COVID-19 disease in new York City pediatric hematology and oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(9) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nathan N., et al. The wide Spectrum of COVID-19 clinical presentation in children. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9) doi: 10.3390/jcm9092950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Allison D., et al. Red blood cell exchange to avoid intubating a COVID-19 positive patient with sickle cell disease? J Clin Apher. 2020;35(4):378–381. doi: 10.1002/jca.21809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okar L., Aldeeb M., Yassin M.A. The role of red blood cell exchange in sickle cell disease in patient with COVID-19 infection and pulmonary infiltrates. Clin Case Rep. 2020;9(1):337–344. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okar L., et al. Severe hemolysis and vaso-occlusive crisis due to COVID-19 infection in a sickle cell disease patient improved after red blood cell exchange. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(4):2117–2221. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brousse V., et al. Low incidence of COVID-19 severe complications in a large cohort of children with sickle cell disease: a protective role for basal interferon-1 activation? Haematologica. 2021;106(10):2746–2748. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.278573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Voskaridou E., et al. The effect of prolonged administration of hydroxyurea on morbidity and mortality in adult patients with sickle cell syndromes: results of a 17-year, single-center trial (LaSHS) Blood. 2010;115(12):2354–2363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ware R.E. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2010;115(26):5300–5311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-146852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morrone K.A., et al. Acute chest syndrome in the setting of SARS-COV-2 infections-a case series at an urban medical center in the Bronx. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(11) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Team C.C.-R. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children - United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Al-Hebshi A., et al. A Saudi family with sickle cell disease presented with acute crises and COVID-19 infection. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(9) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Al Sabahi A., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in children with sickle cell disease: case series from Oman. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;43(7):e975–e978. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andre N., et al. COVID-19 in pediatric oncology from French pediatric oncology and hematology centers: high risk of severe forms? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(7) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Appiah-Kubi A., et al. Varying presentations and favourable outcomes of COVID-19 infection in children and young adults with sickle cell disease: an additional case series with comparisons to published cases. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(4):e221–e224. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dagalakis U., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric patient with hemoglobin SC disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(11) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Espanol M.G., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a pediatric patient with sickle cell disease and COVID-19: a case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002191. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34001792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heilbronner C., et al. Patients with sickle cell disease and suspected COVID-19 in a paediatric intensive care unit. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(1):e21–e24. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jacob S., Dworkin A., Romanos-Sirakis E. A pediatric patient with sickle cell disease presenting with severe anemia and splenic sequestration in the setting of COVID-19. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(12) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kasinathan S., et al. COVID-19 infection and acute pulmonary embolism in an adolescent female with sickle cell disease. Cureus. 2020;12(12) doi: 10.7759/cureus.12348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martone G.M., et al. Acute hepatic encephalopathy and multiorgan failure in sickle cell disease and COVID-19. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(5) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Odievre M.H., et al. Dramatic improvement after tocilizumab of severe COVID-19 in a child with sickle cell disease and acute chest syndrome. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(8):E192–E194. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parodi E., et al. Simultaneous diagnosis of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and sickle cell disease in two infants. Blood Transfus. 2021;19(2):120–123. doi: 10.2450/2021.0430-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quaresima M., et al. Clinical management of a Nigerian patient affected by sickle cell disease with rare blood group and persistent SARS-CoV-2 positivity. EJHaem. 2020;1:384–387. doi: 10.1002/jha2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roussel A., et al. Cranial polyneuropathy as the first manifestation of a severe COVID-19 in a child. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(3) doi: 10.1002/pbc.28707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walker S.C., et al. COVID-19 pneumonia in a pediatric sickle cell patient requiring red blood cell exchange. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(3):1367–1370. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fisler G., et al. Characteristics and risk factors associated with critical illness in pediatric COVID-19. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00790-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Team, C.C.-R. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Resurreccion W.K., et al. Association of sickle cell trait with risk and mortality of COVID-19: results from the United Kingdom biobank. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(2):368–371. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Merz L.E., et al. Impact of sickle cell trait on morbidity and mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood Adv. 2021;5(18):3690–3693. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]