Abstract

Background:

Patient-centered care requires understanding patient preferences and needs, but research on the clinical care preferences of individuals living with dementia and caregivers is sparse, particularly in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

Methods:

Investigators conducted telephone interviews with individuals living with DLB and caregivers from a Lewy body dementia specialty center. Interviews employed a semi-structured questionnaire querying helpful aspects of care and unmet needs. Investigators used a qualitative descriptive approach to analyze transcripts and identify themes.

Results:

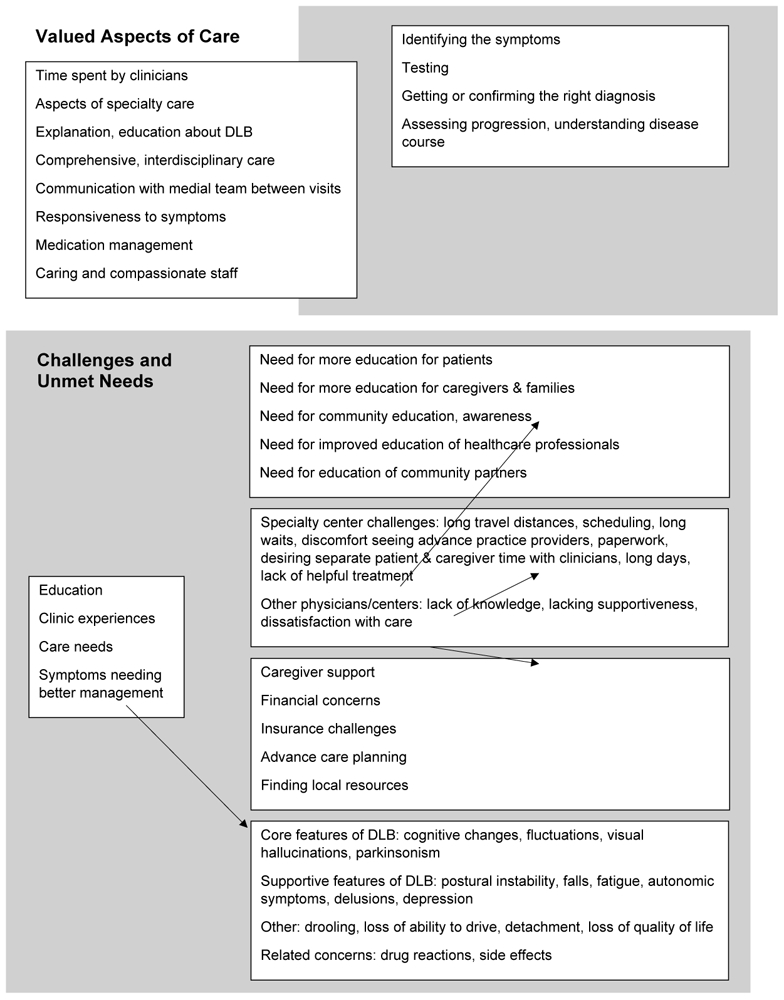

Twenty individuals with DLB and 25 caregivers participated. Twenty-three of the caregivers were spouses, two were daughters. Aspects of clinical care valued by individuals with DLB and caregivers included clinician time, diagnosis, education, symptom management, communication, and caring staff. Unmet needs or challenges included patient/caregiver education, education of non-specialist clinicians and community care providers, scheduling difficulties, caregiver support, financial concerns, assistance with advance care planning and finding local resources, and effective treatments for DLB symptoms.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Improving care for individuals with DLB and their families will require a multi-pronged strategy including education for non-specialist care providers, increasing specialty care access, improved clinical care services, research to support disease prognosis and treatment decisions, and local and national strategies for enhanced caregiver support.

Keywords: Lewy body dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, Lewy body disease [MeSH], participatory research, patient-centered research

Introduction

Twenty years ago, the Institute of Medicine outlined six aims for health care delivery, including patient-centered care.1 Patient-centered care is care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values.1 Despite an increased emphasis on patient-centered care, relatively little research focuses on clinical care preferences of individuals living with dementia.

Prior research identified that individuals with dementia and caregivers have unmet needs relating to dementia diagnosis, education, resource referrals, safety, medical care, meaningful activities, legal issues/advance care planning, and caregiver mental health.2 Gaps in dementia care relate to fragmented and difficult-to-navigate healthcare systems, limited clinician knowledge and skill relating to dementia care, poor communication and information sharing, and ineffective healthcare policies for improving dementia care.3 Individuals living with dementia and caregivers prioritize caregiver support, long-term care needs, research, education and training for caregivers, communities, clinicians, and staff, and dementia advocacy and awareness.4

Examining clinical care values of individuals with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) separately from other dementias is important because DLB has key differences from Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias. Individuals with DLB have symptoms such as cognitive fluctuations, hallucinations, and dream enactment, distinct from AD.5 Life expectancy is shorter in individuals with DLB (median of 3–4 years after diagnosis)6-8 compared to Parkinson disease9, 10 or AD dementia.7, 11 Caregiver burden is higher in DLB compared to AD dementia.12-14 Only one identified study reports unmet needs in DLB.15 In that study, caregivers desired more information and education about DLB diagnosis and management and more information about DLB research, specialists, and facilities skilled in DLB care.15 We thus aimed to investigate (1) aspects of care that are helpful and (2) unmet needs, particularly to guide care at our center.

Methods

Study design

The study used telephone interviews with individuals living with DLB and caregivers to investigate clinical care experiences and needs. A separate analysis assessed research priorities.16 Investigators used a qualitative descriptive approach to analyze interview transcripts.17 This approach involves reporting and summarizing straightforward accounts of participants’ views without intending to generate or test theory. Qualitative research reporting criteria guided study reporting (Supplemental File 1).18

Population and recruitment

Individuals with DLB and caregivers of individuals with DLB were recruited from the University of Florida, a Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA) Research Center of Excellence. The clinic is a tertiary referral center with patients primarily from Florida and Georgia. Patients receiving care at this center can self-refer or are referred by primary care physicians or specialists. During the study period, the clinic included on-site therapy (physical, occupational, speech) and social work. Neuropsychological testing, psychiatry, and swallow evaluations were available separately. Patients typically received therapy evaluations at consultation and follow-up visits every 6-12 months on the same day as physician appointments.

Study inclusion criteria were: (1) patient or caregiver of a patient followed at the center, (2) patient diagnosis of DLB,5 (3) if an individual with DLB, clinician-judged mild-moderate dementia severity (to allow study participation), and (4) willingness to do a telephone interview. Individuals with mild cognitive impairment (suspected prodromal DLB) were excluded. Patients and caregivers were not required to participate as a dyad. Participants were recruited consecutively at routine clinical visits or through a consent-to-contact research database. The University of Florida institutional review board provided approval (IRB201500996). The study used a waiver of documentation of informed consent.

Data collection and analysis

The PI (MJA), a DLB specialist, drafted the semi-structured interview guide. A neuropsychologist (GS), PhD specializing in qualitative research (TM), former caregiver of an individual with DLB (AT), and dementia specialist (not further involved) provided revisions. Questions queried the most helpful aspects of care, unmet needs, unaddressed symptoms, and suggestions for clinic changes (Supplemental File 2).

A research assistant with qualitative research experience conducted interviews (SA). The research assistant received DLB education from the clinical team but had no formal healthcare training. The research assistant had no pre-existing relationship with participants. If an individual with DLB and their caregiver both participated, the preferred approach was to conduct separate interviews. However, the interviewer accommodated requests for caregivers to be present during patient interviews. Caregiver opinions offered during patient interviews were coded as belonging to the caregiver. A professional service transcribed the audio recordings verbatim. Member checking was not performed.

Investigators used Microsoft Word® and Excel 2016® tables to organize data and a qualitative descriptive approach to identify and organize themes.17 The PI and two research assistants independently analyzed interview transcripts to create a codebook and then reached consensus regarding emerging themes (open coding). Broad categories were defined by the four interview questions, but themes were identified from transcripts. The research assistants analyzed remaining transcripts using a constant comparative technique, revising themes and subthemes with the PI (axial coding). Coders assessed saturation during analysis by identifying emergence of new themes/sub-themes. Co-investigators gave feedback after the initial coding. Participants were numbered so that participants who enrolled as a dyad shared a number (“P” indicating patients, “CG” indicating caregivers).

Results

Demographic and interview characteristics

Interviews occurred 1/22/2018-5/6/2019. Twenty individuals with DLB and 25 caregivers participated (Table 1). Six individuals with DLB and ten caregivers expressed interest in the study during a clinical visit but subsequently either declined to or could not be reached for scheduling. Participants reflected 17 dyads, 3 individuals with DLB without a participating caregiver, and 8 caregivers. Caregivers included 20 wives, 3 husbands, and 2 daughters. Caregivers were present for two patient interviews. Saturation of themes was reached with the target sample of 25 caregivers. Because the degree to which patients could participate varied and some patients had difficulty answering the questions, saturation of themes was not reached for the patient sample. The study closed after enrolling 20 individuals with DLB because of recruitment challenges, particularly after caregiver recruitment was complete.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Individuals with dementia with Lewy bodies (n=20) |

Caregivers of individuals with dementia with Lewy bodies (n=25) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Female gender (number, %) | 2 (10%) | 22 (88%) |

| Age range (number, %) | ||

| 50-59 | 1 (5%) | 8 (32%) |

| 60-69 | 10 (50%) | 9 (36%) |

| 70-79 | 7 (35%) | 6 (24%) |

| >80 | 2 (10%) | 2 (8%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 17 (85%) | 23 (92%) |

| White Hispanic | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Black | 2 (10%) | 2 (8%) |

| Highest education | ||

| Did not finish high school | 1 (5%) | 1 (4%) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 1 (5%) | 1 (4%) |

| Associate degree or vocational training | 2 (10%) | 5 (20%) |

| Some college, no degree | 3 (15%) | 4 (16%) |

| Bachelor degree | 5 (25%) | 12 (48%) |

| Advanced degree (e.g. MS, MD, PhD) | 8 (40%) | 2 (8%) |

| Interview duration* (mean, minutes) | 28:11 | 37:10 |

This is the total interview duration, including reflections on both clinical care and research priorities.

Exemplar quotes supporting themes (Figure 1) relating to valued aspects of care and challenges/unmet needs are provided.

Figure 1.

Identified themes relating to valued aspects of care and challenges/unmet meeds

Valued Aspects of Care

Patients and caregivers appreciated the time dedicated to clinic visits, sometimes spending multiple hours with the clinician team (Table e-1, Supplemental File 3). They valued having clinicians identify relevant symptoms, obtaining testing or knowing that more testing was not needed, receiving a diagnosis and/or confirmation of a diagnosis, and obtaining a better understanding of expected DLB progression. Caregivers were particularly appreciative of explanations and education about DLB:

He was very good for explaining it… He really sat down and explained everything to us and showed us on the CAT scans and MRIs and stuff exactly what it was that he was looking at and explained it to us because we did have a different diagnosis, at one time. (CP12, wife)

[Doctor] is so direct and has such a great ability to distill very complex things into very simple and straightforward, but thorough, answers (CP5, husband).

She gave me… a little thing on LBDA, a little pamphlet kind of thing. And then she gave me some support group information that I'm gonna try to do when I can. (CP14, wife)

Multiple participants mentioned that specialty center care was an improvement over care received previously. A couple caregivers appreciated receiving care at a center performing DLB research and training physicians about DLB. Patients and caregivers valued the center’s holistic approach to management including physical, occupational, and speech therapy, psychiatry, and social work, and being able to have assessments on the same day (Table e-1).

Caregivers appreciated being able to communicate with the medical team between visits and responsiveness of the care team:

They are very attentive to every need that we have. And I’m always provided with contact information for… whomever I need to contact regarding a specific issue. (CP8, wife)

I have gotten really good answers. The doctor really helped when I was having my husband take a particular medication for constipation… (CP13, wife)

One caregiver particularly appreciated that the clinician asked her husband what he was feeling and what was driving his quality of life. Both patients and caregivers commented on the value of symptom management with medications (Table e-1).

Participants commented on the caring and compassionate clinic staff (Table e-1). Small numbers of participants mentioned appreciating the clinic environment (e.g. clean but not sterile), reasonable waiting times, well-spaced appointments, having a care team involving a local neurologist in addition to specialists, and physicians taking the lead on difficult conversations (e.g. driving). Caregivers also mentioned relying on home care including therapy, aides/paid caregivers, caregiver training, skilled nursing facilities, hospice, personal support networks (e.g. through church), and services (e.g. financial) to support planning for the future.

Challenges and Unmet Needs

Education

Additional education across groups – patients, caregivers/families, communities/the public, health care professionals, and community partners – was a commonly reported unmet need (Table 2). Patient and caregiver participants desired more information about DLB. Caregivers also reported needing more education about what to do between visits, expected progression, and coping strategies. They emphasized that education should be provided in “layman’s language.” Confusing vocabulary (e.g. relating to parkinsonism, Lewy body dementia) was mentioned as problematic by multiple caregivers. Some caregivers desired team meetings or ways for family members to get information regarding DLB and how to support the patient and primary caregiver. Several patients and caregivers desired education regarding research opportunities. Multiple caregivers (and to a lesser extent, patients) described a need for more DLB awareness and education for non-specialist health care professionals and community health partners (Table 2). Lack of DLB knowledge in these scenarios resulted in delayed diagnoses and use of antipsychotics typically avoided in DLB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unmet Needs Relating to Education about Dementia with Lewy Bodies

| Theme | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Need for more education for patients | I think it’s great sitting down with the doctors and all that, but… it doesn’t really tell me too much, you know, because I’m not too sure what I’m doing, you know?… I’m an information person. I just wanna know more, you know? - just more comprehensive information. (P3) Don’t be shy to hurt my feelings, but just you know, let me know so I know what I’m coming into. I don’t like going into the dark. I like to—you know, if it’s gonna happen, it’s gonna happen, you know? (P4) More education. I feel like the more you know about it, the better off you’ll be. Well, it would mostly be education only about dementia. (P11) |

| Need for more education for caregivers & families | When he was first diagnosed, there was a lack of information, I mean, pretty much everything… I think that there ought to be, like, information pamphlets about the emergency room stuff—with Lewy bodies, how pretty much none of his doctors are gonna know what it is. (CP9, wife) I think it would be helpful for the spouse to be scheduled for maybe, like, a workshop or just an hour long process of what’s gonna, you know, teaching you what’s gonna—the symptoms that come up and what’s, you know, the decisions you’re gonna have to make and the help you’re gonna have to show him and – and different things. Just an education about the both of them together. For the spouse, not the person that - that is diagnosed with the disease. And it wouldn’t hurt for the person that has the disease also. (CP16, wife) Maybe follow up [the initial consultation] with a family appointment and say, “All family members are invited. Those who the caregiver and the patient feel they would like to invite—-to an appointment to discuss their fears, their needs, what they can do.” Let them understand how important they are in being there for both the patient and the caregiver. (CP8, wife) |

| Need for community education, awareness | I think that better education about what Lewy body disease is. None of my friends have ever heard of it before. They’ve all heard of Alzheimer’s, but they’ve never heard of Lewy body. I think there needs to be more information, public information. (CP10, wife) |

| Need for improved education of healthcare professionals | Well, if medical professionals, even the, you know, like the geriatric specialists and people—if they could more know the symptoms, they would be a lot better. (P25) And a lot of doctors, I feel, don’t know about Lewy body. They’re not educated that well in that. And I’m even talking about the neurologist that we went to before we ever got to [facility name]. That was like oh, my God. And then, when he got diagnosed at [facility name], I was like, “What? That was never in the picture.” (CP4, wife) I think because there’s so much lack of information about this disease that I don’t always trust. Cuz, like, he he had one stay in the hospital where they didn’t have a clue. And they wouldn’t listen to me. I had to call our doctor up there. I said, “Can you talk to them?” (CP9, wife) When we go to the emergency room, when she has falls, I'm like, do not give her anything in this class of drugs, because a lot of doctors don't know that. So that's a broad-based thing with clinical care. But many, many, many don't know or understand. They have no concept of the fact that people with Lewy body dementia can't have certain medications. (CP21, daughter) I was kind of just out there on my own, thinking, “Golly. He’s just shuffling around. He’s falling.” You know, and he had been doing that. He’d done that in his general practitioner’s office and his psychiatrist’s office. He’s been shuffling in there. And, you know, that was the doctor that gave him—and I’m not blaming any doctors. I just think, they need to be better educated. I’m not bitter, but then they gave us Latuda on top of it. Well, talk about crashing. (CP25, wife) |

| Need for education of community partners | I use respite care for a few hours a week, but these people are ill prepared and unmotivated to participate in this disease state. It’s not business as usual. This is a little bit different, but I think we have an obligation to help educate the people that are coming in to assist with the care of these people and not just assume that the type of care that they provide is going be adequate. (CP13, wife) I did the Savvy [Caregiver] Class. You know, an eight-week program…Even the leader didn’t know too much about Lewy body. (CP25, wife) The doctors and all the medical into, our law enforcement probably needs to know and understand it too. That they’re not - that they’re not street crazy, but it might appear that way if - if they were in a dangerous situation. (CP25, wife) |

Clinic Experiences

Specialty center. Numerous participants expressed challenges relating to travelling long distances for specialty care, and wishing they lived closer. Several caregivers described difficulty scheduling their consultation, a long wait to get appointments, or trouble scheduling all visits (e.g., physician, therapy) conveniently within a single day, particularly if allowing for travel times. Single caregivers mentioned long waiting room experiences, discomfort with seeing an advanced practice provider, time to complete visit paperwork, or feeling that questionnaires were irrelevant. One patient requested telemedicine. A couple caregivers wished that patients and caregivers could have separate allotted physician time. A couple caregivers also mentioned that neuropsychological testing and clinic days with interdisciplinary assessments are exhausting and overwhelming for people with DLB. Several caregivers wished that follow up visits could be scheduled more frequently than every 6 months, though one expressed uncertainty of the value of routine check-ups. Several patients and caregivers expressed frustration that they hadn’t received DLB treatment or that medication hadn’t helped:

I'm confused, because I don't feel that there's enough guidance in how to treat the Lewy body. (CP6, wife)

Even though they did diagnose him more with Lewy body than Parkinson’s, he still didn’t get any medicine. And we couldn’t figure out why. (CP16, wife)

One dyad wished that it was easier to access psychiatric care at the specialty center. A couple caregivers mentioned the importance of care team communication.

Other physicians/centers. A couple caregivers expressed frustration with their primary care physicians relating to lack of DLB knowledge and lack of supportiveness generally. A couple caregivers also described negative experiences with local neurologists relating to lack of DLB knowledge and dissatisfaction with medication approaches. One caregiver reported negative experiences with multiple rehabilitation facilities. Some gaps relating to primary care, general neurology, and rehabilitation services overlapped with the education theme noted above.

Care Needs

A couple caregivers described needing help to get things done or better understand caregiver roles/responsibilities (Table e-2, Supplemental File 3). Multiple caregivers reported financial concerns relating to caregiving, medications, hotel stays for clinic visits, and general care. Patients and caregivers described challenges with insurance coverage. One caregiver expressed regret that she didn’t know about long-term care insurance sooner. Multiple caregivers desired more assistance in advance care planning, including financial decisions, power of attorney paperwork, guardianship, and percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement. Patients and caregivers described difficulty finding local resources to support DLB care and lacking support (e.g. therapy, psychiatric care) close to home. A couple caregivers reported challenges relating to transportation assistance.

Symptoms Needing Better Management

When queried regarding unaddressed symptoms, participants mentioned most of the core features of DLB and many supportive features (Table 3). Single participants mentioned concerns such as drooling, loss of the ability to drive, “detachment” (reported by an individual with DLB), pain, and loss of quality of life. Multiple participants mentioned concerns regarding drug reactions and side effects:

Table 3.

Symptoms Needing Better Management in Dementia with Lewy Bodies

| Symptom | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Cognitive changes | My memory. I have both problems both with my short term memory, for example, in finishing sentences sometimes. Or forgetting- formulating a sentence in conversation and forgetting it. As in the longer term, I have just memory losses that can encompass two or three days, say, three or four months ago. And I just have no memory of the outing that we––or whatever we’ve been on, none at all. (P28) Following instructions. For example, my wife may say something, and I—it takes me longer to process what she’s asking me or telling me. And so I need some—I need a little more. I’m slower on the uptake. (P16) His memory isn’t really our biggest problem. It’s decision making and - and being able to sort out what you’re telling him sometimes. (CP25, wife) |

| Fluctuations | And I have good days and bad days. I don’t different— I can’t tell really when I’m having—sometimes I wake up and I know I’m foggy and whatever and I do realize it, and then other times I think I just don’t but. And my wife says, “No you are.” And I’m like, “I’m not.” (P8) I go up there. I mean, they're very nice. And he always puts on a good show. He can stand up when somebody asks him to. And, you know, if I ask him the name of a restaurant we went to five years ago in [city name], he knows the name of it. So he knows all my children. He knows people. And other times, he's just totally out of it. (CP6, wife) |

| Psychosis | Well, you know, he’s hallucinating a lot more now—- and, um, the—he’s really—the medication that has been recommended, the side-effects are – are, you know, frightening. So, he doesn’t wanna take them. (CP23, wife) The only bad thing that he’s got is he’s seeing bugs coming out of his skin, mostly his arms. He just insists that they’re there. He sees them. He sits there in the chair, and he looks at—he just keeps picking, and his arms are in terrible shape… He says, "I just seen that—I just seen him come up out of there." He said, "I grabbed him by his head and pulled him out and his head came off." He said, "I was trying to save it so I could show it to you, so you would know what I’m talking about." He said, "I dropped it and his head went right back down into another hole." This goes on all the time… I’m afraid he’s gonna get staph or MRSA (CP11, wife) |

| Parkinsonism, falls | One thing I have is muscles straighten up, and loosen up, and stop doing the shaking and all that. A lot of shaking sometimes. And the legs kick at night. (P7) There’s so many things wrong with me; with the gait, I often fall down. (P23) He’s fallen a little more now. He just balance is, not very good, as it was. But then the medicine that they prescribed to help with the balance worsens the hallucinations. (CP23, wife) He physically can’t do a lot anymore—- and, of course that’s disturbing to him—deeply disturbing—- because he can’t do what he used to do. (CP24, wife) |

| Fatigue | He is always tired. So it’s hard for him. You know, say he’ll wanna go walk or do this. And – and it’s a real effort. (CP19, wife) |

| Autonomic symptoms | I think most affected his quality of life was the physical aspect of it, sort of orthostatic hypertension, not being able—you just basically—we couldn’t keep his blood pressure in a place that he wasn’t gonna get those… we called them episodes, when he would start to shake. And then his knees would buckle. And if you weren’t there, he would go down. It looked just like, you know, if you stand up too fast from the table and you’re—the room spins and you pass out. It looked like that. So, we never knew when that was gonna happen. (CP5, husband) I guess that leads us to another symptom, that she's got some real temperature change symptoms. (CP21, daughter) She thinks she has to go to the bathroom all the time.. Whenever I'm with her, she's, like, "I have to go to the bathroom. I've got to go to the bathroom. Go to the bathroom." I get that all the time. (CP21, daughter) |

| Depression | Well, they haven’t necessarily addressed depression. We’ve gone out on our own to find a psychologist. (CP17, wife) |

Really, the drug interaction thing is the only thing. (P22)

I know the more you probably, I would say sedate them or give them the like hallucination medicines, the more you have to keep increasing that. It can’t be good for them. It helps calm them down where they’re not frightened and they’re tolerable, but what’s it doing to them physically? You know, is it taking away from their life? (CP7, wife)

There’s such a big risk with taking some type of sleeping aids with medications that they take —it’s just like you’re afraid to take a Tylenol because… those can be permanent things that happen to them when they have those reactions. That’s pretty scary. (CP12, wife)

Discussion

In this interview study, individuals with mild-moderate DLB and caregivers valued when clinicians spent time with them, made or confirmed the DLB diagnosis, provided clear education on DLB and expected progression, identified and addressed symptoms, and communicated well between visits. Multiple participants described appreciating caring and compassionate staff and holistic interdisciplinary management. Caregivers mentioned relying on additional services including home care, paid caregivers, caregiver training, skilled nursing facilities, hospice, and services (e.g. financial) to support future planning.

While multiple participants mentioned receiving DLB education and described this as helpful, education was also a commonly reported unmet need. This included education targeting patients, caregivers/families, the public, health care professionals, and community partners. Several participants expressed frustration that local care teams were unfamiliar with DLB. While specialty care was frequently praised, challenges included the long travel distances, scheduling difficulties, and the person with DLB finding the long days to be overwhelming. A couple caregivers wished that patients and caregivers could have separate allotted physician time. Caregivers voiced unmet needs including needing help with caregiver support, financial concerns, insurance challenges, advance care planning, and finding local resources. Participants mentioned multiple symptoms needing improved management strategies.

The fact that individuals with DLB and caregivers valued diagnosis, disease education, symptom management, good communication, caring and compassionate staff, and time spent with clinicians is unsurprising, as these are care elements prioritized by patients across diseases. The 2020 Healthgrades patient sentiment report identified that skill/care quality (defined as patients’ trust in the clinician’s ability to provide effective treatment), bedside manner, communication, staff, and visit time were the top five themes in clinician reviews.19 Surveyed individuals with early-stage AD report that quality care includes early diagnosis, education, clinicians getting to know the person with dementia, and personalized care.20

The unmet needs are also not unique to DLB, but many have particular weight in DLB. Multiple participants described challenges getting a DLB diagnosis prior to the specialty evaluation. Diagnosis is an unmet need in dementia2 and particularly in DLB, where it can take years to get the correct diagnosis21 and 1 in 3 cases may be missed.22 Patient and caregiver education regarding dementia and what to expect are also unmet needs in dementia generally2, 23-26 and in DLB.15 While some participants described education as an unmet need, many participants reported education about DLB and what to expect as specialty clinic benefits. This dichotomy has multiple explanations. The specialty center where this research was conducted has over 10 attending physicians who care for individuals with DLB and at least 6 fellows training at any one time. Educational approaches may differ between clinicians, though all clinicians have access to LBDA materials. Additionally, individual patients and caregivers may have different educational expectations. Finally, unmet educational needs likely relate in part to lacking knowledge in the field. Formal recommendations for DLB care were only published in 2020,27 and they rely on expert consensus to supplement limited DLB-specific evidence. Evidence regarding cause of death in DLB was published only in 2019,8 and research regarding natural history and expected progression are needed.16, 28

Similar to current themes, individuals with dementia and their caregivers previously described unmet needs relating to resource referrals, meaningful activities, and legal issues/advance care planning.2 While specialty centers can partly address these needs, numerous participants described challenges relating to travel distances and appointment frequency. This underscores the importance of local clinical care (e.g. primary care, general neurology, therapy, home care, and hospice), but caregivers reported difficulty finding local resources and health care/community providers with DLB knowledge. Similar challenges were described in the 2010 study of caregivers in DLB,15 suggesting that little has changed in ten years. Telemedicine access facilitated by the COVID pandemic may increase specialty center access. However, research needs to investigate whether DLB can be accurately diagnosed via telemedicine (e.g. without a full physical examination), how to address videoconferencing challenges (e.g. relating to access to technology, comfort with technology, and DLB-specific features such as delusions which may incorporate screens), and how to deliver interdisciplinary care remotely.

Caregivers expressed needing help with caregiver support, guidance, and financial challenges. While clinic social workers can provide guidance on mechanisms for caregiver support (e.g. paid aides) and financial assistance, the ability to pay for home care and medical needs is often limited by individual circumstances. In 2015, a U.S.-based survey of individuals with dementia and their care partners prioritized caregiver support – including financial compensation, case management, counseling, and respite – as their top overall priority for the federal government. Financial assistance/respite funding was the top caregiver support priority.4 Skill training for informal caregivers and health care workers were the top two priorities relating to education.4 Issues relating to caregiver roles, financial burden/out-of-pocket costs, and ensuring a trained workforce were also three of the priorities from the 2017 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and their Caregivers.29

Finally, individuals with DLB and caregivers reported numerous symptoms needing improved management strategies. Currently there are no treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in DLB. Initiating clinical trials for symptoms affecting patient function and caregiver burden is a National Institutes of Health priority,28 but evidence-based treatments are currently lacking and existing treatments are often insufficient or risk worsening other symptoms.27

This study is the first to evaluate valued aspects of care and challenges/unmet needs of both individuals living with DLB and their caregivers. The qualitative descriptive approach used involves reporting and summarizing participants’ views without an intent to generate or test theory.17 Interviews from a single U.S.-based DLB center of excellence affects generalizability, but identified themes were consistent with prior publications. Interviewing individuals without subspecialty care would likely identify additional themes; other specialty centers could have different strengths or gaps. While interview questions were drafted and revised based on input from multiple individuals, only one former caregiver was represented. There was no pilot testing with individuals with DLB or active caregivers. Additional interview prompting could have resulted in different responses. The study sought the opinions of individuals with DLB to give them an active voice – important for patient-centered care, including in dementia20, 30 – but several individuals struggled with participation. Still, quotes from 15 individuals with DLB were included in this report, quotes from two more supported overall themes, and the remaining three participants had only praise for their clinical care. Most caregiver participants were wives. Other caregiver types could have different experiences. Most participants were of white non-Hispanic backgrounds with high educational attainment, but prior research found that unmet needs may be higher in minorities and caregivers with lower education.2 Experiences with diagnosis and unmet needs could vary with other patient and caregiver groups.

Conclusions

This study identified aspects of clinical care valued by individuals with DLB and caregivers (clinician time, diagnosis, education, symptom management, communication, and caring staff), suggesting that clinics should focus on these elements of care. The study also identified areas for improvement: patient/caregiver education, education of non-specialist clinicians and community care providers, scheduling difficulties, caregiver support, financial concerns, assistance with advance care planning and finding local resources, and improved symptomatic approaches. Some of these gaps can be addressed through changes at the clinic level, such as through partnership with the LBDA to provide education, providing social work support, and ensuring that clinicians are knowledgeable about treatment options. Other gaps require further research (e.g. research on prognosis/natural history to inform counseling, development of improved symptomatic approaches, and identification of optimal caregiver support strategies) or potentially governmental strategies (e.g. caregiver financial assistance). The current study was conducted before the COVID pandemic and increased telemedicine use; further research is also needed to investigate whether telemedicine can help address some identified barriers to care (e.g. distance to specialty centers). Improving care for individuals with DLB and their families will require a multi-pronged strategy including education for local non-specialist care providers, increasing access to specialty care, improved clinical care services, research to support disease counseling and treatment decisions, and local and national strategies for enhanced caregiver support.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist

Supplemental Digital Content 2: Interview guide

Supplemental Digital Content 3: Tables e-1, e-2

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ K08HS24159). Research support also occurred through the University of Florida Dorothy Mangurian Headquarters for Lewy Dementia and the Raymond E. Kassar Research Fund for Lewy Body Dementia. These funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

M. J. Armstrong: M.J. Armstrong is supported by grants from AHRQ (K08HS24159), NIA (R01AG068128, P30AG047266), and the Florida Department of Health (grant 20A08). She receives compensation from the AAN for work as an evidence-based medicine methodology consultant and is on the level of evidence editorial board for Neurology® and related publications (uncompensated) and receives publishing royalties for Parkinson’s Disease: Improving Patient Care (Oxford University Press, 2014). She serves as an investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

N. Gamez: Nothing to disclose.

S. Alliance: Nothing to disclose.

T. Majid: Nothing to disclose.

A. S. Taylor: Ms. Taylor is employed by the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

A. M. Kurasz: A. M. Kurasz is supported by T32AG020499.

B. Patel: B. Patel received research support from an American Academy of Neurology Clinical Research Training Scholarship in Lewy Body Dementia and compensation for consultation with Medtronic.

G. Smith: G. Smith receives research support from the 1Florida ADRC (P30AG047266) and the Florida Department of Health Ed & Ethel Moore research program.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ K08HS24159). Research support also occurred through the University of Florida Dorothy Mangurian Headquarters for Lewy Dementia and the Raymond E. Kassar Research Fund for Lewy Body Dementia. These funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D. C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black BS, Johnston D, Rabins PV, et al. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: findings from the maximizing independence at home study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2087–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin A, O'Connor S, Jackson C. A scoping review of gaps and priorities in dementia care in Europe. Dementia (London) 2020;19:2135–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porock D, Bakk L, Sullivan SS, et al. National priorities for dementia care: perspectives of individuals living with dementia and their care partners. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker Z, Allen RL, Shergill S, et al. Three years survival in patients with a clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price A, Farooq R, Yuan JM, et al. Mortality in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer's dementia: a retrospective naturalistic cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong MJ, Alliance S, Corsentino P, et al. Cause of death and end-of-life experiences in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lau LML, Schipper CMA, Hofman A, et al. Prognosis of Parkinson disease - Risk of dementia and mortality: The Rotterdam Study. Arch of Neurol. 2005;62:1265–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hely MA, Reid WGJ, Adena MA, et al. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson's disease: The inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23:837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams MM, Xiong CJ, Morris JC, et al. Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1935–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svendsboe E, Terum T, Testad I, et al. Caregiver burden in family carers of people with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:1075–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci M, Guidoni SV, Sepe-Monti M, et al. Clinical findings, functional abilities and caregiver distress in the early stage of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer's disease (AD). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:e101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DR, McKeith I, Mosimann U, Ghosh-Nodyal A, Thomas AJ. Examining carer stress in dementia: the role of subtype diagnosis and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, et al. Lewy body dementia: caregiver burden and unmet needs. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong MJ, Gamez N, Alliance S, et al. Research priorities of caregivers and individuals with dementia with Lewy bodies: An interview study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0239279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colorafi KJ, Evans B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. HERD. 2016;9:16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healthgrades, Medical Group Management Association: 2020 Patient Sentiment Report. 2020. Available at: https://www.healthgrades.com/content/patient-sentiment-report. Accessed November 12, 2020.

- 20.Alzheimer's Association: A Guide to Quality Care from the Perspectives of People Living with Dementia. January 2018. Available at: https://www.alz.org/getmedia/a6b80947-18cb-4daf-91e4-7f4c52d598fd/quality-care-person-living-with-dementia. Accessed on November 12, 2020.

- 21.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, et al. Lewy body dementia: the caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas AJ, Taylor JP, McKeith I, et al. Development of assessment toolkits for improving the diagnosis of the Lewy body dementias: feasibility study within the DIAMOND Lewy study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:1280–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Evertson LC, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of individuals referred to a dementia care program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennings J, Froggatt K, Keady J. Approaching the end of life and dying with dementia in care homes: the accounts of family carers. Rev in Clin Gerontol. 2010;20:114–127. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millenaar JK, Bakker C, Koopmans RT, et al. The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:1261–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore KJ, Davis S, Gola A, et al. Experiences of end of life amongst family carers of people with advanced dementia: longitudinal cohort study with mixed methods. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor JP, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, et al. New evidence on the management of Lewy body dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:157–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corriveau RA, Koroshetz WJ, Gladman JT, et al. Alzheimer's Disease-Related Dementias Summit 2016: National research priorities. Neurology. 2017;89:2381–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gitlin LN, Maslow K. National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and their Caregiveres: Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer's Research, Care, and Services. May 16, 2019. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/259156/FinalReport.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank L, Shubeck E, Schicker M, et al. Contributions of Persons Living With Dementia to Scientific Research Meetings. Results From the National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons With Dementia and Their Caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist

Supplemental Digital Content 2: Interview guide

Supplemental Digital Content 3: Tables e-1, e-2